User login

Ophthalmologist who developed medical botox dies at 89

his family confirmed to National Public Radio.

Four decades ago, Alan Brown Scott, MD, a native of Berkeley, Calif., turned the drug, once a deadly poison, into a revolutionary treatment for obscure eye diseases. It later became a well-known blockbuster treatment for reducing the appearance of wrinkles and treating hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating). Other approved medical uses include treatment of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, its popularity for cosmetic use was boosted further during the pandemic and it was the No. 1 minimally invasive cosmetic procedure performed in 2020. Among the 13.3 million procedures, 4.4 million involved Botox.

According to Bloomberg Businessweek, Ed Schantz, who was working in the military’s biological weapons program, was the one to first send the toxin to Dr. Scott, who wanted to explore its properties for medical use.

The same Bloomberg article also noted that the original botulinum toxin itself “is so powerful that a tiny amount can suffocate a person by paralyzing the muscles used for breathing.”

Dr. Scott was looking for a way to help his patients avoid extensive surgeries.

“Specifically, he was aiming to treat people with strabismus, or cross-eyes, and blepharospasm, which is an uncontrollable closure of eyes. Today, it’s also used as a treatment to help with migraines, hair loss, and drooling,” NPR reported.

The New York Times once described Botox as “medicine’s answer to duct tape.”

Dr. Scott was the executive director of the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in San Francisco when he did his pioneering research with botulinum toxin in the 1970s and 1980s, according to a 2002 article in SFGate.

In 1991, Dr. Scott sold the drug to Allergan, when it was called Oculinum. The next year, the name was officially changed to Botox.

In 2002, Dr. Scott told SFGate, when asked about the more popular use for the drug, “I think that’s a charming, slightly frivolous use,” adding, “but it’s not along the lines of what I was into, applications for serious disorders.”

According to Scientific American in 2016, Dr. Scott, then age 83, kept working on the noncosmetic benefits of botulism-toxin injections for eye-related disorders at the Strabismus Research Foundation,

He told Scientific American he was proud that his efforts “are directly helpful to people.”

“There are interesting and difficult problems still to be solved, and I’m a practicing physician and I see them every day,” he said.

Dr. Scott’s daughter, Ann Scott, told NPR: “He definitely loved his work and he was also a really great father.” She said her dad involved his children in his research and work.

She added, “He was a really calm, more of a quiet reserved person,” and said he was committed to teaching his students, many of them international students.

“That was what he really loved,” she said.

Dr. Scott, who died Dec. 16, was in intensive care for the last 10 days from an unspecified illness, his daughter told NPR.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

his family confirmed to National Public Radio.

Four decades ago, Alan Brown Scott, MD, a native of Berkeley, Calif., turned the drug, once a deadly poison, into a revolutionary treatment for obscure eye diseases. It later became a well-known blockbuster treatment for reducing the appearance of wrinkles and treating hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating). Other approved medical uses include treatment of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, its popularity for cosmetic use was boosted further during the pandemic and it was the No. 1 minimally invasive cosmetic procedure performed in 2020. Among the 13.3 million procedures, 4.4 million involved Botox.

According to Bloomberg Businessweek, Ed Schantz, who was working in the military’s biological weapons program, was the one to first send the toxin to Dr. Scott, who wanted to explore its properties for medical use.

The same Bloomberg article also noted that the original botulinum toxin itself “is so powerful that a tiny amount can suffocate a person by paralyzing the muscles used for breathing.”

Dr. Scott was looking for a way to help his patients avoid extensive surgeries.

“Specifically, he was aiming to treat people with strabismus, or cross-eyes, and blepharospasm, which is an uncontrollable closure of eyes. Today, it’s also used as a treatment to help with migraines, hair loss, and drooling,” NPR reported.

The New York Times once described Botox as “medicine’s answer to duct tape.”

Dr. Scott was the executive director of the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in San Francisco when he did his pioneering research with botulinum toxin in the 1970s and 1980s, according to a 2002 article in SFGate.

In 1991, Dr. Scott sold the drug to Allergan, when it was called Oculinum. The next year, the name was officially changed to Botox.

In 2002, Dr. Scott told SFGate, when asked about the more popular use for the drug, “I think that’s a charming, slightly frivolous use,” adding, “but it’s not along the lines of what I was into, applications for serious disorders.”

According to Scientific American in 2016, Dr. Scott, then age 83, kept working on the noncosmetic benefits of botulism-toxin injections for eye-related disorders at the Strabismus Research Foundation,

He told Scientific American he was proud that his efforts “are directly helpful to people.”

“There are interesting and difficult problems still to be solved, and I’m a practicing physician and I see them every day,” he said.

Dr. Scott’s daughter, Ann Scott, told NPR: “He definitely loved his work and he was also a really great father.” She said her dad involved his children in his research and work.

She added, “He was a really calm, more of a quiet reserved person,” and said he was committed to teaching his students, many of them international students.

“That was what he really loved,” she said.

Dr. Scott, who died Dec. 16, was in intensive care for the last 10 days from an unspecified illness, his daughter told NPR.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

his family confirmed to National Public Radio.

Four decades ago, Alan Brown Scott, MD, a native of Berkeley, Calif., turned the drug, once a deadly poison, into a revolutionary treatment for obscure eye diseases. It later became a well-known blockbuster treatment for reducing the appearance of wrinkles and treating hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating). Other approved medical uses include treatment of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence.

According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, its popularity for cosmetic use was boosted further during the pandemic and it was the No. 1 minimally invasive cosmetic procedure performed in 2020. Among the 13.3 million procedures, 4.4 million involved Botox.

According to Bloomberg Businessweek, Ed Schantz, who was working in the military’s biological weapons program, was the one to first send the toxin to Dr. Scott, who wanted to explore its properties for medical use.

The same Bloomberg article also noted that the original botulinum toxin itself “is so powerful that a tiny amount can suffocate a person by paralyzing the muscles used for breathing.”

Dr. Scott was looking for a way to help his patients avoid extensive surgeries.

“Specifically, he was aiming to treat people with strabismus, or cross-eyes, and blepharospasm, which is an uncontrollable closure of eyes. Today, it’s also used as a treatment to help with migraines, hair loss, and drooling,” NPR reported.

The New York Times once described Botox as “medicine’s answer to duct tape.”

Dr. Scott was the executive director of the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute in San Francisco when he did his pioneering research with botulinum toxin in the 1970s and 1980s, according to a 2002 article in SFGate.

In 1991, Dr. Scott sold the drug to Allergan, when it was called Oculinum. The next year, the name was officially changed to Botox.

In 2002, Dr. Scott told SFGate, when asked about the more popular use for the drug, “I think that’s a charming, slightly frivolous use,” adding, “but it’s not along the lines of what I was into, applications for serious disorders.”

According to Scientific American in 2016, Dr. Scott, then age 83, kept working on the noncosmetic benefits of botulism-toxin injections for eye-related disorders at the Strabismus Research Foundation,

He told Scientific American he was proud that his efforts “are directly helpful to people.”

“There are interesting and difficult problems still to be solved, and I’m a practicing physician and I see them every day,” he said.

Dr. Scott’s daughter, Ann Scott, told NPR: “He definitely loved his work and he was also a really great father.” She said her dad involved his children in his research and work.

She added, “He was a really calm, more of a quiet reserved person,” and said he was committed to teaching his students, many of them international students.

“That was what he really loved,” she said.

Dr. Scott, who died Dec. 16, was in intensive care for the last 10 days from an unspecified illness, his daughter told NPR.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dermatologists driving use of vascular lasers in the Medicare population

In addition, as a proportion of Medicare charges submitted that were reimbursed, the highest reimbursements were for dermatologists and those in the Western geographic region.

Those are among the key findings from an analysis that aimed to characterize trends in use and reimbursement patterns of vascular lasers in the Medicare-insured population.

“There are several modalities for vascular laser treatment, including the pulse dye laser, the frequency doubled KTP laser, and others,” presenting author Partik Singh, MD, MBA, said during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “Laser treatment of vascular lesions may sometimes be covered by insurance, depending on the indication, but little is known about how and which clinicians are taking advantage of this covered treatment.”

Dr. Singh, a 2nd-year dermatology resident at the University of Rochester Medical Center, and coauthor Mara Weinstein Velez, MD, extracted data from the 2012-2018 Medicare Public Use File, which includes 100% fee-for-service, non–Medicare Advantage claims based on CPT codes, yet no information on patient data, clinical context, or indications. Outcomes of interest were total vascular laser claims per year, annual vascular laser claims per clinician, annual clinicians using vascular lasers, accepted reimbursements defined by the allowed charge or the submitted charge to Medicare, and clinical specialties and geographic location.

The researchers found that more than half of clinicians who used vascular lasers during the study period were dermatologists (55%), followed by general surgeons (6%), family practice/internal medicine physicians (5% each) and various others. Use of vascular lasers among all clinicians increased 10.5% annually during the study period, from 3,786 to 6,883, and was most pronounced among dermatologists, whose use increased 18.4% annually, from 1,878 to 5,182. “Nondermatologists did not have a big change in their overall utilization rate, but they did have a steady utilization of vascular lasers, roughly at almost 2,000 claims per year,” Dr. Singh said.

The researchers also observed that the use of vascular lasers on a per-clinician basis increased 7.4% annually among all clinicians during the study period, from 77.3 to 118.7. This was mostly driven by dermatologists, whose per-clinician use increased 10.4% annually, from 81.7 to 148.7. Use by nondermatologists remained about stable, with just a 0.1% increase annually, from 73.4 to 74. In addition, the number of clinicians who billed for vascular laser procedures increased 2.9% annually between 2012 and 2018, from 49 to 58. This growth was driven mostly by dermatologists, who increased their billing for vascular laser procedures by 7.2% annually, from 23 to 35 clinicians.

In other findings, dermatologists were reimbursed at 68.3% of submitted charges, compared with 59.3% of charges submitted by other clinicians (P = .0001), and reimbursement rates were greatest in the Western geographic region of the United States vs. the Northeast, Midwest, and Southern regions (73.1% vs. 50.2%, 65.4%, and 55.3%, respectively; P < .0001).

“Use of vascular lasers is increasing primarily among dermatologists, though there is steady use of these procedures by nondermatologists,” Dr. Singh concluded. “Medicare charges were more often fully reimbursed when billed by dermatologists and those in the Western U.S., perhaps suggesting a better familiarity with appropriate indications and better administrative resources for coverage of vascular laser procedures.”

After the meeting, Dr. Singh acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it “was limited only to Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims, not including Medicare Advantage,” he told this news organization. “Our conclusions do not necessarily hold true for Medicaid or commercial insurers, for instance. Moreover, this dataset doesn’t provide patient-specific information, such as the indication for the procedure. Further studies are needed to characterize utilization of various lasers in not only Medicare beneficiaries, but also those with Medicaid, private insurance, and patients paying out-of-pocket. Additionally, study is also needed to explain why these differences in reimbursement hold true.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

In addition, as a proportion of Medicare charges submitted that were reimbursed, the highest reimbursements were for dermatologists and those in the Western geographic region.

Those are among the key findings from an analysis that aimed to characterize trends in use and reimbursement patterns of vascular lasers in the Medicare-insured population.

“There are several modalities for vascular laser treatment, including the pulse dye laser, the frequency doubled KTP laser, and others,” presenting author Partik Singh, MD, MBA, said during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “Laser treatment of vascular lesions may sometimes be covered by insurance, depending on the indication, but little is known about how and which clinicians are taking advantage of this covered treatment.”

Dr. Singh, a 2nd-year dermatology resident at the University of Rochester Medical Center, and coauthor Mara Weinstein Velez, MD, extracted data from the 2012-2018 Medicare Public Use File, which includes 100% fee-for-service, non–Medicare Advantage claims based on CPT codes, yet no information on patient data, clinical context, or indications. Outcomes of interest were total vascular laser claims per year, annual vascular laser claims per clinician, annual clinicians using vascular lasers, accepted reimbursements defined by the allowed charge or the submitted charge to Medicare, and clinical specialties and geographic location.

The researchers found that more than half of clinicians who used vascular lasers during the study period were dermatologists (55%), followed by general surgeons (6%), family practice/internal medicine physicians (5% each) and various others. Use of vascular lasers among all clinicians increased 10.5% annually during the study period, from 3,786 to 6,883, and was most pronounced among dermatologists, whose use increased 18.4% annually, from 1,878 to 5,182. “Nondermatologists did not have a big change in their overall utilization rate, but they did have a steady utilization of vascular lasers, roughly at almost 2,000 claims per year,” Dr. Singh said.

The researchers also observed that the use of vascular lasers on a per-clinician basis increased 7.4% annually among all clinicians during the study period, from 77.3 to 118.7. This was mostly driven by dermatologists, whose per-clinician use increased 10.4% annually, from 81.7 to 148.7. Use by nondermatologists remained about stable, with just a 0.1% increase annually, from 73.4 to 74. In addition, the number of clinicians who billed for vascular laser procedures increased 2.9% annually between 2012 and 2018, from 49 to 58. This growth was driven mostly by dermatologists, who increased their billing for vascular laser procedures by 7.2% annually, from 23 to 35 clinicians.

In other findings, dermatologists were reimbursed at 68.3% of submitted charges, compared with 59.3% of charges submitted by other clinicians (P = .0001), and reimbursement rates were greatest in the Western geographic region of the United States vs. the Northeast, Midwest, and Southern regions (73.1% vs. 50.2%, 65.4%, and 55.3%, respectively; P < .0001).

“Use of vascular lasers is increasing primarily among dermatologists, though there is steady use of these procedures by nondermatologists,” Dr. Singh concluded. “Medicare charges were more often fully reimbursed when billed by dermatologists and those in the Western U.S., perhaps suggesting a better familiarity with appropriate indications and better administrative resources for coverage of vascular laser procedures.”

After the meeting, Dr. Singh acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it “was limited only to Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims, not including Medicare Advantage,” he told this news organization. “Our conclusions do not necessarily hold true for Medicaid or commercial insurers, for instance. Moreover, this dataset doesn’t provide patient-specific information, such as the indication for the procedure. Further studies are needed to characterize utilization of various lasers in not only Medicare beneficiaries, but also those with Medicaid, private insurance, and patients paying out-of-pocket. Additionally, study is also needed to explain why these differences in reimbursement hold true.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

In addition, as a proportion of Medicare charges submitted that were reimbursed, the highest reimbursements were for dermatologists and those in the Western geographic region.

Those are among the key findings from an analysis that aimed to characterize trends in use and reimbursement patterns of vascular lasers in the Medicare-insured population.

“There are several modalities for vascular laser treatment, including the pulse dye laser, the frequency doubled KTP laser, and others,” presenting author Partik Singh, MD, MBA, said during a virtual abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. “Laser treatment of vascular lesions may sometimes be covered by insurance, depending on the indication, but little is known about how and which clinicians are taking advantage of this covered treatment.”

Dr. Singh, a 2nd-year dermatology resident at the University of Rochester Medical Center, and coauthor Mara Weinstein Velez, MD, extracted data from the 2012-2018 Medicare Public Use File, which includes 100% fee-for-service, non–Medicare Advantage claims based on CPT codes, yet no information on patient data, clinical context, or indications. Outcomes of interest were total vascular laser claims per year, annual vascular laser claims per clinician, annual clinicians using vascular lasers, accepted reimbursements defined by the allowed charge or the submitted charge to Medicare, and clinical specialties and geographic location.

The researchers found that more than half of clinicians who used vascular lasers during the study period were dermatologists (55%), followed by general surgeons (6%), family practice/internal medicine physicians (5% each) and various others. Use of vascular lasers among all clinicians increased 10.5% annually during the study period, from 3,786 to 6,883, and was most pronounced among dermatologists, whose use increased 18.4% annually, from 1,878 to 5,182. “Nondermatologists did not have a big change in their overall utilization rate, but they did have a steady utilization of vascular lasers, roughly at almost 2,000 claims per year,” Dr. Singh said.

The researchers also observed that the use of vascular lasers on a per-clinician basis increased 7.4% annually among all clinicians during the study period, from 77.3 to 118.7. This was mostly driven by dermatologists, whose per-clinician use increased 10.4% annually, from 81.7 to 148.7. Use by nondermatologists remained about stable, with just a 0.1% increase annually, from 73.4 to 74. In addition, the number of clinicians who billed for vascular laser procedures increased 2.9% annually between 2012 and 2018, from 49 to 58. This growth was driven mostly by dermatologists, who increased their billing for vascular laser procedures by 7.2% annually, from 23 to 35 clinicians.

In other findings, dermatologists were reimbursed at 68.3% of submitted charges, compared with 59.3% of charges submitted by other clinicians (P = .0001), and reimbursement rates were greatest in the Western geographic region of the United States vs. the Northeast, Midwest, and Southern regions (73.1% vs. 50.2%, 65.4%, and 55.3%, respectively; P < .0001).

“Use of vascular lasers is increasing primarily among dermatologists, though there is steady use of these procedures by nondermatologists,” Dr. Singh concluded. “Medicare charges were more often fully reimbursed when billed by dermatologists and those in the Western U.S., perhaps suggesting a better familiarity with appropriate indications and better administrative resources for coverage of vascular laser procedures.”

After the meeting, Dr. Singh acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including the fact that it “was limited only to Medicare Part B fee-for-service claims, not including Medicare Advantage,” he told this news organization. “Our conclusions do not necessarily hold true for Medicaid or commercial insurers, for instance. Moreover, this dataset doesn’t provide patient-specific information, such as the indication for the procedure. Further studies are needed to characterize utilization of various lasers in not only Medicare beneficiaries, but also those with Medicaid, private insurance, and patients paying out-of-pocket. Additionally, study is also needed to explain why these differences in reimbursement hold true.”

The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ASDS 2021

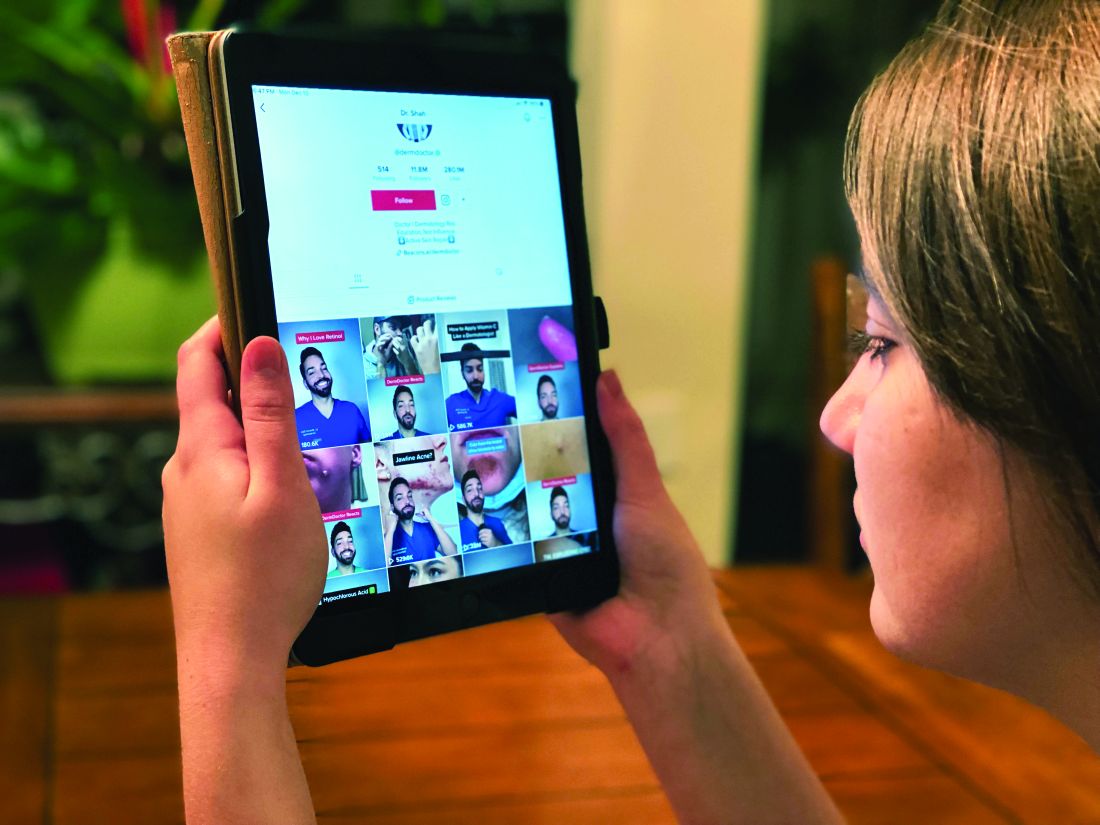

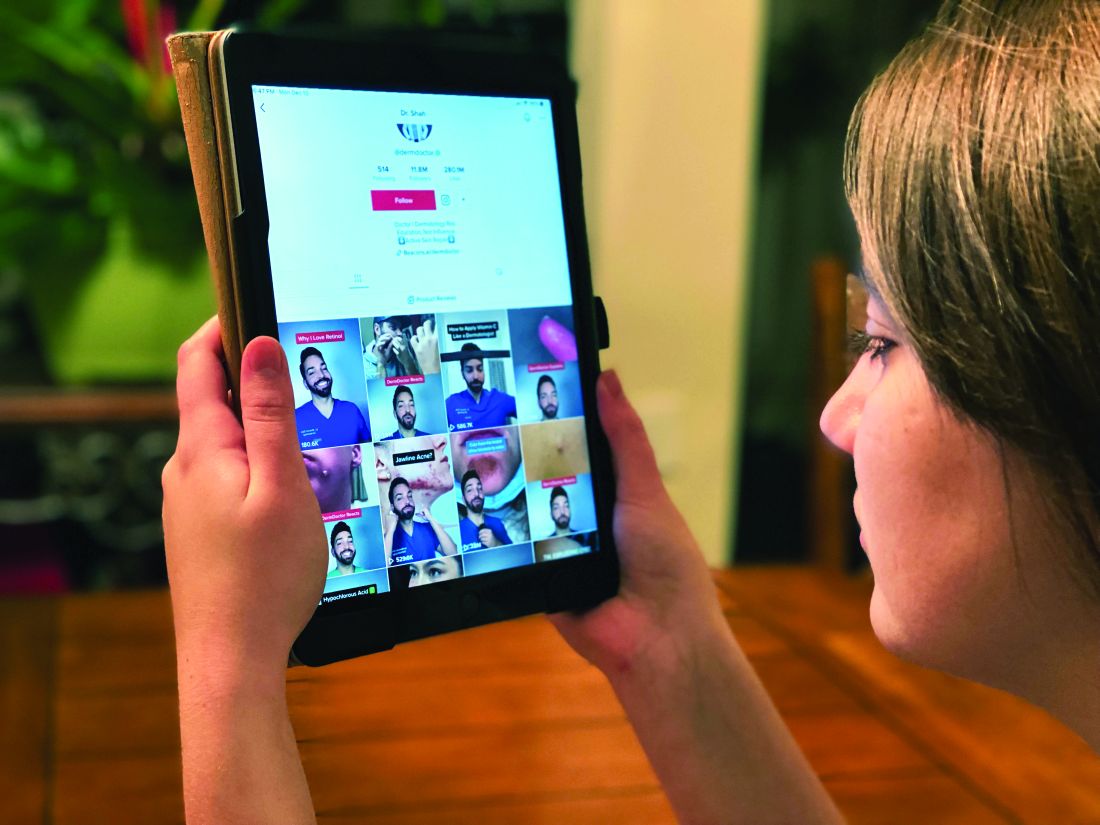

Dermatologists take to TikTok to share their own ‘hacks’

A young woman is having her lip swabbed with an unknown substance, smiling, on the TikTok video. Seconds later, another young woman, wearing gloves, pushes a hyaluron pen against the first woman’s lips, who, in the next cut, is smiling, happy. “My first syringe down and already 1,000x more confident,” the caption reads.

That video is one of thousands showing hyaluron pen use on TikTok. The pens are sold online and are unapproved – which led to a Food and Drug Administration warning in October 2021 that use could cause bleeding, infection, blood vessel occlusion that could result in blindness or stroke, allergic reactions, and other injuries.

The warning has not stopped many TikTokkers, who also use the medium to promote all sorts of skin and aesthetic products and procedures, a large number unproven, unapproved, or ill advised. which, more often than not, comes from “skinfluencers,” aestheticians, and other laypeople, not board-certified dermatologists.

The suggested “hacks” can be harmless or ineffective, but they also can be misleading, fraudulent, or even dangerous.

Skinfluencers take the lead

TikTok has a reported 1 billion monthly users. Two-thirds are aged 10-29 years, according to data reported in February 2021 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology by David X. Zheng, BA, and colleagues at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and the department of dermatology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Visitors consume information in video bits that run from 15 seconds to up to 3 minutes and can follow their favorite TikTokkers, browse for people or hashtags with a search function, or click on content recommended by the platform, which uses algorithms based on the user’s viewing habits to determine what might be of interest.

Some of the biggest “skinfluencers” have millions of followers: Hyram Yarbro, (@skincarebyhyram) for instance, has 6.6 million followers and his own line of skin care products at Sephora. Mr. Yarbro is seen as a no-nonsense debunker of skin care myths, as is British influencer James Welsh, who has 124,000 followers.

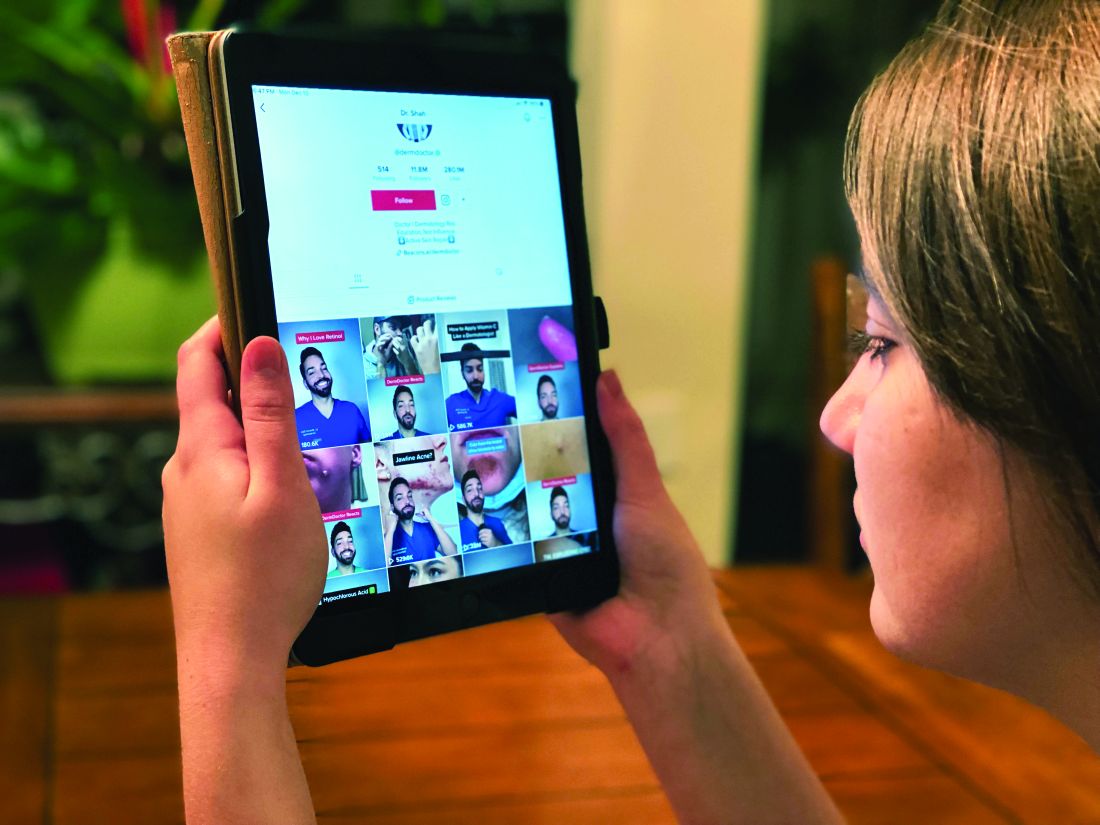

“The reason why people trust your average influencer person who’s not a doctor is because they’re relatable,” said Muneeb Shah, MD, a dermatology resident at Atlantic Dermatology in Wilmington, N.C. – known to his 11.4 million TikTok followers as @dermdoctor.

To Sandra Lee, MD, the popularity of nonprofessionals is easy to explain. “You have to think about the fact that a lot of people can’t see dermatologists – they don’t have the money, they don’t have the time to travel there, they don’t have health insurance, or they’re scared of doctors, so they’re willing to try to find an answer, and one of the easiest ways, one of the more entertaining ways to get information, is on social media.”

Dr. Lee is in private practice in Upland, Calif., but is better known as “Dr. Pimple Popper,” through her television show of the same name and her social media accounts, including on TikTok, where she has 14.4 million followers after having started in 2020.

“We’re all looking for that no-down-time, no-expense, no-lines, no-wrinkles, stay-young-forever magic bullet,” said Dr. Lee.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, agreed that people are looking for a quick fix. They don’t want to wait 12 weeks for an acne medication or 16 weeks for a biologic to work. “They want something simple, easy, do-it-yourself,” and “natural,” he said.

Laypeople are still the dominant producers – and have the most views – of dermatology content.

Morgan Nguyen, BA, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues looked at hashtags for the top 10 dermatologic diagnoses and procedures and analyzed the content of the first 40 TikTok videos in each category. About half the videos were produced by an individual, and 39% by a health care provider, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. About 40% of the videos were educational, focusing on skin care, procedures, and disease treatment.

Viewership was highest for videos by laypeople, followed by those produced by business or industry accounts. Those produced by health care providers received only 18% of the views.

The most popular videos were about dermatologic diagnoses, with 2.5 billion views, followed by dermatologic procedures, with 708 million views.

Ms. Nguyen noted in the study that the most liked and most viewed posts were related to #skincare but that board-certified dermatologists produced only 2.5% of the #skincare videos.

Dermatologists take to TikTok

Some dermatologists have started their own TikTok accounts, seeking both to counteract misinformation and provide education.

Dr. Shah has become one of the top influencers on the platform. In a year-end wrap, TikTok put Dr. Shah at No. 7 on its top creators list for 2021.

The dermatology resident said that TikTok is a good tool for reaching patients who might not otherwise interact with dermatologists. He recounted the story of an individual who came into his office with the idea that they had hidradenitis suppurativa.

The person had self-diagnosed after seeing one of Dr. Shah’s TikTok videos on the condition. It was a pleasant surprise, said Dr. Shah. People with hidradenitis suppurativa often avoid treatment, and it’s underdiagnosed and improperly treated, despite an American Academy of Dermatology awareness campaign.

“Dermatologists on social media are almost like the communications department for dermatology,” Dr. Shah commented.

A key to making TikTok work to advance dermatologists’ goals is knowing what makes it unique.

Dr. Lee said she prefers it to Instagram, because TikTok’s algorithms and its younger-skewing audience help her reach a more specific audience.

The algorithm “creates a positive feedback loop in which popular content creators or viral trends are prioritized on the users’ homepages, in turn providing the creators of these videos with an even larger audience,” Mr. Zheng, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and coauthors noted in their letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

TikTok also celebrates the everyday – someone doesn’t have to be a celebrity to make something go viral, said Dr. Lee. She believes that TikTok users are more accepting of average people with real problems – which helps when someone is TikTokking about a skin condition.

Doris Day, MD, who goes by @drdorisday on TikTok, agreed with Dr. Lee. “There are so many creative ways you can convey information with it that’s different than what you have on Instagram,” said Dr. Day, who is in private practice in New York. And, she added, “it does really lend itself to getting points out super-fast.”

Dermatologists on TikTok also said they like the “duets” and the “stitch” features, which allow users to add on to an existing video, essentially chiming in or responding to what might have already been posted, in a side-by-side format.

Dr. Shah said he often duets videos that have questionable content. “It allows me to directly respond to people. A lot of times, if something is going really viral and it’s not accurate, you’ll have a response from me or one of the other doctors” within hours or days.

Dr. Shah’s duets are labeled with “DermDoctor Reacts” or “DermDoctor Explains.” In one duet, with more than 2.8 million views, the upper half of the video is someone squeezing a blackhead, while Dr. Shah, in the bottom half, in green scrubs, opines over some hip-hop music: “This is just a blackhead. But once it gets to this point, they do need to be extracted because topical treatments won’t help.”

Dr. Lee – whose TikTok and other accounts capitalize on teens’ obsession with popping pimples – has a duet in which she advised that although popping will leave scars, there are more ideal times to pop, if they must. The duet has at least 21 million views.

Sometimes a TikTok video effectively takes on a trend without being a duet. Nurse practitioner Uy Dam (@uy.np) has a video that demonstrates the dangers of hyaluron pens. He uses both a pen and a needle to inject fluid into a block of jello. The pen delivers a scattershot load of differing depths, while the needle is exact. It’s visual and easy to understand and has at least 1.3 million views.

Still, TikTok, like other forms of social media, is full of misinformation and false accounts, including people who claim to be doctors. “It’s hard for the regular person, myself included, sometimes to be able to root through that and find out whether something is real or not,” said Dr. Lee.

Dr. Friedman said he’s concerned about the lack of accountability. A doctor could lose his or her license for promoting unproven cures, especially if they are harmful. But for influencers, “there’s no accountability for posting information that can actually hurt people.”

TikTok trends gone bad

And some people are being hurt by emulating what they see on TikTok.

Dr. Friedman had a patient with extreme irritant contact dermatitis, “almost like chemical burns to her underarms,” he said. He determined that she saw a video “hack” that recommended using baking soda to stop hyperhidrosis. The patient used so much that it burned her skin.

In 2020, do-it-yourself freckles – with henna or sewing needles impregnated with ink – went viral. Tilly Whitfeld, a 21-year-old reality TV star on Australia’s Big Brother show, told the New York Times that she tried it at home after seeing a TikTok video. She ordered brown tattoo ink online and later found out that it was contaminated with lead, according to the Times. Ms. Whitfeld developed an infection and temporary vision loss and has permanent scarring.

She has since put out a cautionary TikTok video that’s been viewed some 300,000 times.

TikTokkers have also flocked to the idea of using sunscreen to “contour” the face. Selected areas are left without sunscreen to burn or tan. In a duet, a plastic surgeon shakes his head as a young woman explains that “it works.”

Scalp-popping – in which the hair is yanked so hard that it pulls the galea off the skull – has been mostly shut down by TikTok. A search of “scalp popping” brings up the message: “Learn how to recognize harmful challenges and hoaxes.” At-home mole and skin tag removal, pimple-popping, and supposed acne cures such as drinking chlorophyll are all avidly documented and shared on TikTok.

Dr. Shah had a back-and-forth video dialog with someone who had stubbed a toe and then drilled a hole into the nail to drain the hematoma. In a reaction video, Dr. Shah said it was likely to turn into an infection. When it did, the man revealed the infection in a video where he tagged Dr. Shah and later posted a video at the podiatrist’s office having his nail removed, again tagging Dr. Shah.

“I think that pretty much no procedure for skin is good to do at home,” said Dr. Shah, who repeatedly admonishes against mole removal by a nonphysician. He tells followers that “it’s extremely dangerous – not only is it going to cause scarring, but you are potentially discarding a cancerous lesion.”

Unfortunately, most will not follow the advice, said Dr. Shah. That’s especially true of pimple-popping. Aiming for the least harm, he suggests in some TikTok videos that poppers keep the area clean, wear gloves, and consult a physician to get an antibiotic prescription. “You might as well at least guide them in the right direction,” he added.

Dr. Lee believes that lack of access to physicians, insurance, or money may play into how TikTok trends evolve. “Probably those people who injected their lips with this air gun thing, maybe they didn’t have the money necessarily to get filler,” she said.

Also, she noted, while TikTok may try to police its content, creators are incentivized to be outrageous. “The more inflammatory your post is, the more engagement you get.”

Dr. Shah thinks TikTok is self-correcting. “If you’re not being ethical or contradicting yourself, putting out information that’s not accurate, people are going to catch on very quickly,” he said. “The only value, the only currency you have on social media is the trust that you build with people that follow you.”

What it takes to be a TikTokker

For dermatologists, conveying their credentials and experience is one way to build that currency. Dr. Lee advised fellow doctors on TikTok to “showcase your training and how many years it took to become a dermatologist.”

Plunging into TikTok is not for everyone, though. It’s time consuming, said Dr. Lee, who now devotes most of her nonclinical time to TikTok. She creates her own content, leaving others to manage her Instagram account.

Many of those in the medical field who have dived into TikTok are residents, like Dr. Shah. “They are attuned to it and understand it more,” said Dr. Lee. “It’s harder for a lot of us who are older, who really weren’t involved that much in social media at all. It’s very hard to jump in.” There’s a learning curve, and it takes hours to create a single video. “You have to enjoy it and it has to be a part of your life,” she said.

Dr. Shah started experimenting with TikTok at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 and has never turned back. Fast-talking, curious, and with an infectious sense of fun, he shares tidbits about his personal life – putting his wife in some of his videos – and always seems upbeat.

He said that, as his following grew, users began to see him as an authority figure and started “tagging” him more often, seeking his opinion on other videos. Although still a resident, he believes he has specialized knowledge to share. “Even if you’re not the world’s leading expert in a particular topic, you’re still adding value for the person who doesn’t know much.”

Dr. Shah also occasionally does promotional TikToks, identified as sponsored content. He said he only works with companies that he believes have legitimate products. “You do have to monetize at some point,” he said, noting that many dermatologists, himself included, are trading clinic time for TikTok. “There’s no universe where they can do this for free.”

Product endorsements are likely more rewarding for influencers and other users like Dr. Shah than the remuneration from TikTok, the company. The platform pays user accounts $20 per 1 million views, Dr. Shah said. “Financially, it’s not a big winner for a practicing dermatologist, but the educational outreach is worthwhile.”

To be successful also means understanding what drives viewership.

Using “trending” sounds has “been shown to increase the likelihood of a video amassing millions of views” and may increase engagement with dermatologists’ TikTok videos, wrote Bina Kassamali, BA, and colleagues at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and the Ponce Health Science University School of Medicine in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in a letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in July 2021.

Certain content is more likely to engage viewers. In their analysis of top trending dermatologic hashtags, acne-related content was viewed 6.7 billion times, followed by alopecia, with 1.1 billion views. Psoriasis content had 84 million views, putting it eighth on the list of topics.

Dermatologists are still cracking TikTok. They are accumulating more followers on TikTok than on Instagram but have greater engagement on Instagram reels, wrote Mindy D. Szeto, MS, and colleagues at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Rocky Vista University in Parker, Colo., in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in April 2021.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Shah had the highest engagement rate on TikTok, according to Ms. Szeto. The engagement rate is calculated as (likes + comments per post)/(total followers) x 100.

“TikTok may currently be the leading avenue for audience education by dermatologist influencers,” they wrote, urging dermatologists to use the platform to answer the call as more of the public “continues to turn to social media for medical advice.”

Dr. Day said she will keep trying to build her TikTok audience. She has just 239 followers, compared with her 44,500 on Instagram. “The more I do TikTok, the more I do any of these mediums, the better I get at it,” she said. “We just have to put a little time and effort into it and try to get more followers and just keep sharing the information.”

Dr. Friedman sees it as a positive that some dermatologists have taken to TikTok to dispel myths and put “good information out there in small bites.” But to be more effective, they need more followers.

“The truth is that 14-year-old is probably going to listen more to a Hyram than a dermatologist,” he said. “Maybe we need to work with these other individuals who know how to take these messages and convert them to a language that can be digested by a 14-year-old, by a 12-year-old, by a 23-year-old. We need to come to the table together and not fight.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A young woman is having her lip swabbed with an unknown substance, smiling, on the TikTok video. Seconds later, another young woman, wearing gloves, pushes a hyaluron pen against the first woman’s lips, who, in the next cut, is smiling, happy. “My first syringe down and already 1,000x more confident,” the caption reads.

That video is one of thousands showing hyaluron pen use on TikTok. The pens are sold online and are unapproved – which led to a Food and Drug Administration warning in October 2021 that use could cause bleeding, infection, blood vessel occlusion that could result in blindness or stroke, allergic reactions, and other injuries.

The warning has not stopped many TikTokkers, who also use the medium to promote all sorts of skin and aesthetic products and procedures, a large number unproven, unapproved, or ill advised. which, more often than not, comes from “skinfluencers,” aestheticians, and other laypeople, not board-certified dermatologists.

The suggested “hacks” can be harmless or ineffective, but they also can be misleading, fraudulent, or even dangerous.

Skinfluencers take the lead

TikTok has a reported 1 billion monthly users. Two-thirds are aged 10-29 years, according to data reported in February 2021 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology by David X. Zheng, BA, and colleagues at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and the department of dermatology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Visitors consume information in video bits that run from 15 seconds to up to 3 minutes and can follow their favorite TikTokkers, browse for people or hashtags with a search function, or click on content recommended by the platform, which uses algorithms based on the user’s viewing habits to determine what might be of interest.

Some of the biggest “skinfluencers” have millions of followers: Hyram Yarbro, (@skincarebyhyram) for instance, has 6.6 million followers and his own line of skin care products at Sephora. Mr. Yarbro is seen as a no-nonsense debunker of skin care myths, as is British influencer James Welsh, who has 124,000 followers.

“The reason why people trust your average influencer person who’s not a doctor is because they’re relatable,” said Muneeb Shah, MD, a dermatology resident at Atlantic Dermatology in Wilmington, N.C. – known to his 11.4 million TikTok followers as @dermdoctor.

To Sandra Lee, MD, the popularity of nonprofessionals is easy to explain. “You have to think about the fact that a lot of people can’t see dermatologists – they don’t have the money, they don’t have the time to travel there, they don’t have health insurance, or they’re scared of doctors, so they’re willing to try to find an answer, and one of the easiest ways, one of the more entertaining ways to get information, is on social media.”

Dr. Lee is in private practice in Upland, Calif., but is better known as “Dr. Pimple Popper,” through her television show of the same name and her social media accounts, including on TikTok, where she has 14.4 million followers after having started in 2020.

“We’re all looking for that no-down-time, no-expense, no-lines, no-wrinkles, stay-young-forever magic bullet,” said Dr. Lee.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, agreed that people are looking for a quick fix. They don’t want to wait 12 weeks for an acne medication or 16 weeks for a biologic to work. “They want something simple, easy, do-it-yourself,” and “natural,” he said.

Laypeople are still the dominant producers – and have the most views – of dermatology content.

Morgan Nguyen, BA, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues looked at hashtags for the top 10 dermatologic diagnoses and procedures and analyzed the content of the first 40 TikTok videos in each category. About half the videos were produced by an individual, and 39% by a health care provider, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. About 40% of the videos were educational, focusing on skin care, procedures, and disease treatment.

Viewership was highest for videos by laypeople, followed by those produced by business or industry accounts. Those produced by health care providers received only 18% of the views.

The most popular videos were about dermatologic diagnoses, with 2.5 billion views, followed by dermatologic procedures, with 708 million views.

Ms. Nguyen noted in the study that the most liked and most viewed posts were related to #skincare but that board-certified dermatologists produced only 2.5% of the #skincare videos.

Dermatologists take to TikTok

Some dermatologists have started their own TikTok accounts, seeking both to counteract misinformation and provide education.

Dr. Shah has become one of the top influencers on the platform. In a year-end wrap, TikTok put Dr. Shah at No. 7 on its top creators list for 2021.

The dermatology resident said that TikTok is a good tool for reaching patients who might not otherwise interact with dermatologists. He recounted the story of an individual who came into his office with the idea that they had hidradenitis suppurativa.

The person had self-diagnosed after seeing one of Dr. Shah’s TikTok videos on the condition. It was a pleasant surprise, said Dr. Shah. People with hidradenitis suppurativa often avoid treatment, and it’s underdiagnosed and improperly treated, despite an American Academy of Dermatology awareness campaign.

“Dermatologists on social media are almost like the communications department for dermatology,” Dr. Shah commented.

A key to making TikTok work to advance dermatologists’ goals is knowing what makes it unique.

Dr. Lee said she prefers it to Instagram, because TikTok’s algorithms and its younger-skewing audience help her reach a more specific audience.

The algorithm “creates a positive feedback loop in which popular content creators or viral trends are prioritized on the users’ homepages, in turn providing the creators of these videos with an even larger audience,” Mr. Zheng, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and coauthors noted in their letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

TikTok also celebrates the everyday – someone doesn’t have to be a celebrity to make something go viral, said Dr. Lee. She believes that TikTok users are more accepting of average people with real problems – which helps when someone is TikTokking about a skin condition.

Doris Day, MD, who goes by @drdorisday on TikTok, agreed with Dr. Lee. “There are so many creative ways you can convey information with it that’s different than what you have on Instagram,” said Dr. Day, who is in private practice in New York. And, she added, “it does really lend itself to getting points out super-fast.”

Dermatologists on TikTok also said they like the “duets” and the “stitch” features, which allow users to add on to an existing video, essentially chiming in or responding to what might have already been posted, in a side-by-side format.

Dr. Shah said he often duets videos that have questionable content. “It allows me to directly respond to people. A lot of times, if something is going really viral and it’s not accurate, you’ll have a response from me or one of the other doctors” within hours or days.

Dr. Shah’s duets are labeled with “DermDoctor Reacts” or “DermDoctor Explains.” In one duet, with more than 2.8 million views, the upper half of the video is someone squeezing a blackhead, while Dr. Shah, in the bottom half, in green scrubs, opines over some hip-hop music: “This is just a blackhead. But once it gets to this point, they do need to be extracted because topical treatments won’t help.”

Dr. Lee – whose TikTok and other accounts capitalize on teens’ obsession with popping pimples – has a duet in which she advised that although popping will leave scars, there are more ideal times to pop, if they must. The duet has at least 21 million views.

Sometimes a TikTok video effectively takes on a trend without being a duet. Nurse practitioner Uy Dam (@uy.np) has a video that demonstrates the dangers of hyaluron pens. He uses both a pen and a needle to inject fluid into a block of jello. The pen delivers a scattershot load of differing depths, while the needle is exact. It’s visual and easy to understand and has at least 1.3 million views.

Still, TikTok, like other forms of social media, is full of misinformation and false accounts, including people who claim to be doctors. “It’s hard for the regular person, myself included, sometimes to be able to root through that and find out whether something is real or not,” said Dr. Lee.

Dr. Friedman said he’s concerned about the lack of accountability. A doctor could lose his or her license for promoting unproven cures, especially if they are harmful. But for influencers, “there’s no accountability for posting information that can actually hurt people.”

TikTok trends gone bad

And some people are being hurt by emulating what they see on TikTok.

Dr. Friedman had a patient with extreme irritant contact dermatitis, “almost like chemical burns to her underarms,” he said. He determined that she saw a video “hack” that recommended using baking soda to stop hyperhidrosis. The patient used so much that it burned her skin.

In 2020, do-it-yourself freckles – with henna or sewing needles impregnated with ink – went viral. Tilly Whitfeld, a 21-year-old reality TV star on Australia’s Big Brother show, told the New York Times that she tried it at home after seeing a TikTok video. She ordered brown tattoo ink online and later found out that it was contaminated with lead, according to the Times. Ms. Whitfeld developed an infection and temporary vision loss and has permanent scarring.

She has since put out a cautionary TikTok video that’s been viewed some 300,000 times.

TikTokkers have also flocked to the idea of using sunscreen to “contour” the face. Selected areas are left without sunscreen to burn or tan. In a duet, a plastic surgeon shakes his head as a young woman explains that “it works.”

Scalp-popping – in which the hair is yanked so hard that it pulls the galea off the skull – has been mostly shut down by TikTok. A search of “scalp popping” brings up the message: “Learn how to recognize harmful challenges and hoaxes.” At-home mole and skin tag removal, pimple-popping, and supposed acne cures such as drinking chlorophyll are all avidly documented and shared on TikTok.

Dr. Shah had a back-and-forth video dialog with someone who had stubbed a toe and then drilled a hole into the nail to drain the hematoma. In a reaction video, Dr. Shah said it was likely to turn into an infection. When it did, the man revealed the infection in a video where he tagged Dr. Shah and later posted a video at the podiatrist’s office having his nail removed, again tagging Dr. Shah.

“I think that pretty much no procedure for skin is good to do at home,” said Dr. Shah, who repeatedly admonishes against mole removal by a nonphysician. He tells followers that “it’s extremely dangerous – not only is it going to cause scarring, but you are potentially discarding a cancerous lesion.”

Unfortunately, most will not follow the advice, said Dr. Shah. That’s especially true of pimple-popping. Aiming for the least harm, he suggests in some TikTok videos that poppers keep the area clean, wear gloves, and consult a physician to get an antibiotic prescription. “You might as well at least guide them in the right direction,” he added.

Dr. Lee believes that lack of access to physicians, insurance, or money may play into how TikTok trends evolve. “Probably those people who injected their lips with this air gun thing, maybe they didn’t have the money necessarily to get filler,” she said.

Also, she noted, while TikTok may try to police its content, creators are incentivized to be outrageous. “The more inflammatory your post is, the more engagement you get.”

Dr. Shah thinks TikTok is self-correcting. “If you’re not being ethical or contradicting yourself, putting out information that’s not accurate, people are going to catch on very quickly,” he said. “The only value, the only currency you have on social media is the trust that you build with people that follow you.”

What it takes to be a TikTokker

For dermatologists, conveying their credentials and experience is one way to build that currency. Dr. Lee advised fellow doctors on TikTok to “showcase your training and how many years it took to become a dermatologist.”

Plunging into TikTok is not for everyone, though. It’s time consuming, said Dr. Lee, who now devotes most of her nonclinical time to TikTok. She creates her own content, leaving others to manage her Instagram account.

Many of those in the medical field who have dived into TikTok are residents, like Dr. Shah. “They are attuned to it and understand it more,” said Dr. Lee. “It’s harder for a lot of us who are older, who really weren’t involved that much in social media at all. It’s very hard to jump in.” There’s a learning curve, and it takes hours to create a single video. “You have to enjoy it and it has to be a part of your life,” she said.

Dr. Shah started experimenting with TikTok at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 and has never turned back. Fast-talking, curious, and with an infectious sense of fun, he shares tidbits about his personal life – putting his wife in some of his videos – and always seems upbeat.

He said that, as his following grew, users began to see him as an authority figure and started “tagging” him more often, seeking his opinion on other videos. Although still a resident, he believes he has specialized knowledge to share. “Even if you’re not the world’s leading expert in a particular topic, you’re still adding value for the person who doesn’t know much.”

Dr. Shah also occasionally does promotional TikToks, identified as sponsored content. He said he only works with companies that he believes have legitimate products. “You do have to monetize at some point,” he said, noting that many dermatologists, himself included, are trading clinic time for TikTok. “There’s no universe where they can do this for free.”

Product endorsements are likely more rewarding for influencers and other users like Dr. Shah than the remuneration from TikTok, the company. The platform pays user accounts $20 per 1 million views, Dr. Shah said. “Financially, it’s not a big winner for a practicing dermatologist, but the educational outreach is worthwhile.”

To be successful also means understanding what drives viewership.

Using “trending” sounds has “been shown to increase the likelihood of a video amassing millions of views” and may increase engagement with dermatologists’ TikTok videos, wrote Bina Kassamali, BA, and colleagues at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and the Ponce Health Science University School of Medicine in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in a letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in July 2021.

Certain content is more likely to engage viewers. In their analysis of top trending dermatologic hashtags, acne-related content was viewed 6.7 billion times, followed by alopecia, with 1.1 billion views. Psoriasis content had 84 million views, putting it eighth on the list of topics.

Dermatologists are still cracking TikTok. They are accumulating more followers on TikTok than on Instagram but have greater engagement on Instagram reels, wrote Mindy D. Szeto, MS, and colleagues at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Rocky Vista University in Parker, Colo., in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in April 2021.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Shah had the highest engagement rate on TikTok, according to Ms. Szeto. The engagement rate is calculated as (likes + comments per post)/(total followers) x 100.

“TikTok may currently be the leading avenue for audience education by dermatologist influencers,” they wrote, urging dermatologists to use the platform to answer the call as more of the public “continues to turn to social media for medical advice.”

Dr. Day said she will keep trying to build her TikTok audience. She has just 239 followers, compared with her 44,500 on Instagram. “The more I do TikTok, the more I do any of these mediums, the better I get at it,” she said. “We just have to put a little time and effort into it and try to get more followers and just keep sharing the information.”

Dr. Friedman sees it as a positive that some dermatologists have taken to TikTok to dispel myths and put “good information out there in small bites.” But to be more effective, they need more followers.

“The truth is that 14-year-old is probably going to listen more to a Hyram than a dermatologist,” he said. “Maybe we need to work with these other individuals who know how to take these messages and convert them to a language that can be digested by a 14-year-old, by a 12-year-old, by a 23-year-old. We need to come to the table together and not fight.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A young woman is having her lip swabbed with an unknown substance, smiling, on the TikTok video. Seconds later, another young woman, wearing gloves, pushes a hyaluron pen against the first woman’s lips, who, in the next cut, is smiling, happy. “My first syringe down and already 1,000x more confident,” the caption reads.

That video is one of thousands showing hyaluron pen use on TikTok. The pens are sold online and are unapproved – which led to a Food and Drug Administration warning in October 2021 that use could cause bleeding, infection, blood vessel occlusion that could result in blindness or stroke, allergic reactions, and other injuries.

The warning has not stopped many TikTokkers, who also use the medium to promote all sorts of skin and aesthetic products and procedures, a large number unproven, unapproved, or ill advised. which, more often than not, comes from “skinfluencers,” aestheticians, and other laypeople, not board-certified dermatologists.

The suggested “hacks” can be harmless or ineffective, but they also can be misleading, fraudulent, or even dangerous.

Skinfluencers take the lead

TikTok has a reported 1 billion monthly users. Two-thirds are aged 10-29 years, according to data reported in February 2021 in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology by David X. Zheng, BA, and colleagues at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and the department of dermatology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Visitors consume information in video bits that run from 15 seconds to up to 3 minutes and can follow their favorite TikTokkers, browse for people or hashtags with a search function, or click on content recommended by the platform, which uses algorithms based on the user’s viewing habits to determine what might be of interest.

Some of the biggest “skinfluencers” have millions of followers: Hyram Yarbro, (@skincarebyhyram) for instance, has 6.6 million followers and his own line of skin care products at Sephora. Mr. Yarbro is seen as a no-nonsense debunker of skin care myths, as is British influencer James Welsh, who has 124,000 followers.

“The reason why people trust your average influencer person who’s not a doctor is because they’re relatable,” said Muneeb Shah, MD, a dermatology resident at Atlantic Dermatology in Wilmington, N.C. – known to his 11.4 million TikTok followers as @dermdoctor.

To Sandra Lee, MD, the popularity of nonprofessionals is easy to explain. “You have to think about the fact that a lot of people can’t see dermatologists – they don’t have the money, they don’t have the time to travel there, they don’t have health insurance, or they’re scared of doctors, so they’re willing to try to find an answer, and one of the easiest ways, one of the more entertaining ways to get information, is on social media.”

Dr. Lee is in private practice in Upland, Calif., but is better known as “Dr. Pimple Popper,” through her television show of the same name and her social media accounts, including on TikTok, where she has 14.4 million followers after having started in 2020.

“We’re all looking for that no-down-time, no-expense, no-lines, no-wrinkles, stay-young-forever magic bullet,” said Dr. Lee.

Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, agreed that people are looking for a quick fix. They don’t want to wait 12 weeks for an acne medication or 16 weeks for a biologic to work. “They want something simple, easy, do-it-yourself,” and “natural,” he said.

Laypeople are still the dominant producers – and have the most views – of dermatology content.

Morgan Nguyen, BA, at Northwestern University, Chicago, and colleagues looked at hashtags for the top 10 dermatologic diagnoses and procedures and analyzed the content of the first 40 TikTok videos in each category. About half the videos were produced by an individual, and 39% by a health care provider, according to the study, published in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology. About 40% of the videos were educational, focusing on skin care, procedures, and disease treatment.

Viewership was highest for videos by laypeople, followed by those produced by business or industry accounts. Those produced by health care providers received only 18% of the views.

The most popular videos were about dermatologic diagnoses, with 2.5 billion views, followed by dermatologic procedures, with 708 million views.

Ms. Nguyen noted in the study that the most liked and most viewed posts were related to #skincare but that board-certified dermatologists produced only 2.5% of the #skincare videos.

Dermatologists take to TikTok

Some dermatologists have started their own TikTok accounts, seeking both to counteract misinformation and provide education.

Dr. Shah has become one of the top influencers on the platform. In a year-end wrap, TikTok put Dr. Shah at No. 7 on its top creators list for 2021.

The dermatology resident said that TikTok is a good tool for reaching patients who might not otherwise interact with dermatologists. He recounted the story of an individual who came into his office with the idea that they had hidradenitis suppurativa.

The person had self-diagnosed after seeing one of Dr. Shah’s TikTok videos on the condition. It was a pleasant surprise, said Dr. Shah. People with hidradenitis suppurativa often avoid treatment, and it’s underdiagnosed and improperly treated, despite an American Academy of Dermatology awareness campaign.

“Dermatologists on social media are almost like the communications department for dermatology,” Dr. Shah commented.

A key to making TikTok work to advance dermatologists’ goals is knowing what makes it unique.

Dr. Lee said she prefers it to Instagram, because TikTok’s algorithms and its younger-skewing audience help her reach a more specific audience.

The algorithm “creates a positive feedback loop in which popular content creators or viral trends are prioritized on the users’ homepages, in turn providing the creators of these videos with an even larger audience,” Mr. Zheng, of University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, and coauthors noted in their letter in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

TikTok also celebrates the everyday – someone doesn’t have to be a celebrity to make something go viral, said Dr. Lee. She believes that TikTok users are more accepting of average people with real problems – which helps when someone is TikTokking about a skin condition.

Doris Day, MD, who goes by @drdorisday on TikTok, agreed with Dr. Lee. “There are so many creative ways you can convey information with it that’s different than what you have on Instagram,” said Dr. Day, who is in private practice in New York. And, she added, “it does really lend itself to getting points out super-fast.”

Dermatologists on TikTok also said they like the “duets” and the “stitch” features, which allow users to add on to an existing video, essentially chiming in or responding to what might have already been posted, in a side-by-side format.

Dr. Shah said he often duets videos that have questionable content. “It allows me to directly respond to people. A lot of times, if something is going really viral and it’s not accurate, you’ll have a response from me or one of the other doctors” within hours or days.

Dr. Shah’s duets are labeled with “DermDoctor Reacts” or “DermDoctor Explains.” In one duet, with more than 2.8 million views, the upper half of the video is someone squeezing a blackhead, while Dr. Shah, in the bottom half, in green scrubs, opines over some hip-hop music: “This is just a blackhead. But once it gets to this point, they do need to be extracted because topical treatments won’t help.”

Dr. Lee – whose TikTok and other accounts capitalize on teens’ obsession with popping pimples – has a duet in which she advised that although popping will leave scars, there are more ideal times to pop, if they must. The duet has at least 21 million views.

Sometimes a TikTok video effectively takes on a trend without being a duet. Nurse practitioner Uy Dam (@uy.np) has a video that demonstrates the dangers of hyaluron pens. He uses both a pen and a needle to inject fluid into a block of jello. The pen delivers a scattershot load of differing depths, while the needle is exact. It’s visual and easy to understand and has at least 1.3 million views.

Still, TikTok, like other forms of social media, is full of misinformation and false accounts, including people who claim to be doctors. “It’s hard for the regular person, myself included, sometimes to be able to root through that and find out whether something is real or not,” said Dr. Lee.

Dr. Friedman said he’s concerned about the lack of accountability. A doctor could lose his or her license for promoting unproven cures, especially if they are harmful. But for influencers, “there’s no accountability for posting information that can actually hurt people.”

TikTok trends gone bad

And some people are being hurt by emulating what they see on TikTok.

Dr. Friedman had a patient with extreme irritant contact dermatitis, “almost like chemical burns to her underarms,” he said. He determined that she saw a video “hack” that recommended using baking soda to stop hyperhidrosis. The patient used so much that it burned her skin.

In 2020, do-it-yourself freckles – with henna or sewing needles impregnated with ink – went viral. Tilly Whitfeld, a 21-year-old reality TV star on Australia’s Big Brother show, told the New York Times that she tried it at home after seeing a TikTok video. She ordered brown tattoo ink online and later found out that it was contaminated with lead, according to the Times. Ms. Whitfeld developed an infection and temporary vision loss and has permanent scarring.

She has since put out a cautionary TikTok video that’s been viewed some 300,000 times.

TikTokkers have also flocked to the idea of using sunscreen to “contour” the face. Selected areas are left without sunscreen to burn or tan. In a duet, a plastic surgeon shakes his head as a young woman explains that “it works.”

Scalp-popping – in which the hair is yanked so hard that it pulls the galea off the skull – has been mostly shut down by TikTok. A search of “scalp popping” brings up the message: “Learn how to recognize harmful challenges and hoaxes.” At-home mole and skin tag removal, pimple-popping, and supposed acne cures such as drinking chlorophyll are all avidly documented and shared on TikTok.

Dr. Shah had a back-and-forth video dialog with someone who had stubbed a toe and then drilled a hole into the nail to drain the hematoma. In a reaction video, Dr. Shah said it was likely to turn into an infection. When it did, the man revealed the infection in a video where he tagged Dr. Shah and later posted a video at the podiatrist’s office having his nail removed, again tagging Dr. Shah.

“I think that pretty much no procedure for skin is good to do at home,” said Dr. Shah, who repeatedly admonishes against mole removal by a nonphysician. He tells followers that “it’s extremely dangerous – not only is it going to cause scarring, but you are potentially discarding a cancerous lesion.”

Unfortunately, most will not follow the advice, said Dr. Shah. That’s especially true of pimple-popping. Aiming for the least harm, he suggests in some TikTok videos that poppers keep the area clean, wear gloves, and consult a physician to get an antibiotic prescription. “You might as well at least guide them in the right direction,” he added.

Dr. Lee believes that lack of access to physicians, insurance, or money may play into how TikTok trends evolve. “Probably those people who injected their lips with this air gun thing, maybe they didn’t have the money necessarily to get filler,” she said.

Also, she noted, while TikTok may try to police its content, creators are incentivized to be outrageous. “The more inflammatory your post is, the more engagement you get.”

Dr. Shah thinks TikTok is self-correcting. “If you’re not being ethical or contradicting yourself, putting out information that’s not accurate, people are going to catch on very quickly,” he said. “The only value, the only currency you have on social media is the trust that you build with people that follow you.”

What it takes to be a TikTokker

For dermatologists, conveying their credentials and experience is one way to build that currency. Dr. Lee advised fellow doctors on TikTok to “showcase your training and how many years it took to become a dermatologist.”

Plunging into TikTok is not for everyone, though. It’s time consuming, said Dr. Lee, who now devotes most of her nonclinical time to TikTok. She creates her own content, leaving others to manage her Instagram account.

Many of those in the medical field who have dived into TikTok are residents, like Dr. Shah. “They are attuned to it and understand it more,” said Dr. Lee. “It’s harder for a lot of us who are older, who really weren’t involved that much in social media at all. It’s very hard to jump in.” There’s a learning curve, and it takes hours to create a single video. “You have to enjoy it and it has to be a part of your life,” she said.

Dr. Shah started experimenting with TikTok at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 and has never turned back. Fast-talking, curious, and with an infectious sense of fun, he shares tidbits about his personal life – putting his wife in some of his videos – and always seems upbeat.

He said that, as his following grew, users began to see him as an authority figure and started “tagging” him more often, seeking his opinion on other videos. Although still a resident, he believes he has specialized knowledge to share. “Even if you’re not the world’s leading expert in a particular topic, you’re still adding value for the person who doesn’t know much.”

Dr. Shah also occasionally does promotional TikToks, identified as sponsored content. He said he only works with companies that he believes have legitimate products. “You do have to monetize at some point,” he said, noting that many dermatologists, himself included, are trading clinic time for TikTok. “There’s no universe where they can do this for free.”

Product endorsements are likely more rewarding for influencers and other users like Dr. Shah than the remuneration from TikTok, the company. The platform pays user accounts $20 per 1 million views, Dr. Shah said. “Financially, it’s not a big winner for a practicing dermatologist, but the educational outreach is worthwhile.”

To be successful also means understanding what drives viewership.

Using “trending” sounds has “been shown to increase the likelihood of a video amassing millions of views” and may increase engagement with dermatologists’ TikTok videos, wrote Bina Kassamali, BA, and colleagues at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and the Ponce Health Science University School of Medicine in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in a letter published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in July 2021.

Certain content is more likely to engage viewers. In their analysis of top trending dermatologic hashtags, acne-related content was viewed 6.7 billion times, followed by alopecia, with 1.1 billion views. Psoriasis content had 84 million views, putting it eighth on the list of topics.

Dermatologists are still cracking TikTok. They are accumulating more followers on TikTok than on Instagram but have greater engagement on Instagram reels, wrote Mindy D. Szeto, MS, and colleagues at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and Rocky Vista University in Parker, Colo., in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in April 2021.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Shah had the highest engagement rate on TikTok, according to Ms. Szeto. The engagement rate is calculated as (likes + comments per post)/(total followers) x 100.

“TikTok may currently be the leading avenue for audience education by dermatologist influencers,” they wrote, urging dermatologists to use the platform to answer the call as more of the public “continues to turn to social media for medical advice.”

Dr. Day said she will keep trying to build her TikTok audience. She has just 239 followers, compared with her 44,500 on Instagram. “The more I do TikTok, the more I do any of these mediums, the better I get at it,” she said. “We just have to put a little time and effort into it and try to get more followers and just keep sharing the information.”

Dr. Friedman sees it as a positive that some dermatologists have taken to TikTok to dispel myths and put “good information out there in small bites.” But to be more effective, they need more followers.

“The truth is that 14-year-old is probably going to listen more to a Hyram than a dermatologist,” he said. “Maybe we need to work with these other individuals who know how to take these messages and convert them to a language that can be digested by a 14-year-old, by a 12-year-old, by a 23-year-old. We need to come to the table together and not fight.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acid series: Azelaic acid

However, it has many positive qualities, including being gentle enough to use daily and is safe to use in pregnancy. It is antibacterial, comedolytic, keratolytic, and has antioxidant activity. Unfortunately, in the last decade the formulations of azelaic acid have not been changed considerably. The 20% cream, 15% gel, and 15% foam vehicles are often too irritating and drying to be used in the population it is intended for: those with rosacea, or with inflamed or sensitive skin.

Azelaic acid is a dicarboxylic acid produced by Pityrosporum ovale. It inhibits the synthesis of cellular proteins and is bactericidal against Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Azelaic acid is both keratolytic and comedolytic by decreasing keratohyalin granules and reducing filaggrin in the epidermis. It not only scavenges free oxygen radicals, thereby reducing inflammation, but is also a tyrosinase inhibitor – making it a safe, non–hydroquinone-based alternative to skin lightening.

Azelaic acid has little toxicity, it is ingested regularly as it is found in wheat, barley, and rye. Topical side effects are usually mild and can subside with increased use. The most common side effects include erythema, local stinging, pruritus, scaling, and a burning sensation. It is considered safe in pregnancy and a great alternative to medications for acne in pregnant or nursing patients.

The largest constraint with azelaic acid preparations on the market – and most likely the reason it has not been more widely used for acne, rosacea, antiaging, and hyperpigmentation – is the formulation. The foam and gel preparations are irritating and difficult to use on dry or sensitive skin. The 20% cream preparations are slightly better tolerated; however, in vitro skin-penetration studies have shown that cutaneous penetration of azelaic acid is greater after application of a 15% gel (aqueous-based vehicle) and 15% foam (hydrophilic oil-in-water emulsion) as compared with the 20% cream formulations.

In my clinical experience, azelaic acid can only be used in rosacea patients with oily or nonsensitive skin. The majority of my rosacea patients cannot tolerate the burning sensation, albeit transient and mild. Acne patients who do not have dry skin and pregnant patients with mild acne are a great population for integrating azelaic acid into an acne regimen. I also use azelaic acid as an alternative for mild melasma and lentigines in patients who are tapering off hydroquinone or cannot use hydroquinone. In the future, we need better, creamier, nonirritating formulations to be developed and more studies of higher concentrations of this acid for both prescription/patient at-home use, as well as more elegant in-office localized peel systems using azelaic acid.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Fitton A and Goa KL. Drugs. 1991 May;41(5):780-98.

Del Rosso JQ. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017 Mar;10(3):37-40.

Breathnach AC et al. Clin Dermatol. Apr-Jun 1989;7(2):106-19.

However, it has many positive qualities, including being gentle enough to use daily and is safe to use in pregnancy. It is antibacterial, comedolytic, keratolytic, and has antioxidant activity. Unfortunately, in the last decade the formulations of azelaic acid have not been changed considerably. The 20% cream, 15% gel, and 15% foam vehicles are often too irritating and drying to be used in the population it is intended for: those with rosacea, or with inflamed or sensitive skin.

Azelaic acid is a dicarboxylic acid produced by Pityrosporum ovale. It inhibits the synthesis of cellular proteins and is bactericidal against Propionibacterium acnes and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Azelaic acid is both keratolytic and comedolytic by decreasing keratohyalin granules and reducing filaggrin in the epidermis. It not only scavenges free oxygen radicals, thereby reducing inflammation, but is also a tyrosinase inhibitor – making it a safe, non–hydroquinone-based alternative to skin lightening.

Azelaic acid has little toxicity, it is ingested regularly as it is found in wheat, barley, and rye. Topical side effects are usually mild and can subside with increased use. The most common side effects include erythema, local stinging, pruritus, scaling, and a burning sensation. It is considered safe in pregnancy and a great alternative to medications for acne in pregnant or nursing patients.