User login

Blindness from PRP injections a rare but potentially devastating side effect

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

AT ASDS 2022

Reverse-Grip Technique of Scissors in Dermatologic Surgery: Tips to Improve Undermining Efficiency

Practice Gap

One of the most important elements of successful reconstruction is effective undermining prior to placement of buried sutures. The main benefit of an evenly undermined plane is that tension is reduced, thus permitting seamless tissue mobilization and wound edge approximation.1

However, achieving a consistent and appropriate plane can present challenges in certain blind spots within one’s field of work. A right hand–dominant surgeon might find it difficult to undermine tissue between the 3-o’clock and 6-o’clock positions (Figure 1) and often must resort to unnatural positioning to obtain adequate reach.

We propose a technique of reversing the grip on undermining scissors that improves efficiency without sacrificing technique.

Technique

The surgeon simply grasps the ring handles with the ring finger and thumb with the tip pointing to the wrist (Figure 2). Most of the control comes from rotating the wrist while spreading with the thumb (Figure 3).

The main advantage of the reverse-grip technique is that it prevents abduction of the arm at the shoulder joint, which reduces shoulder fatigue and keeps the elbow close to the trunk and away from the sterile surgical field. Achieving optimal ergonomics during surgery has been shown to reduce pain and likely prolong the surgeon’s career.2

A limitation of the reverse-grip technique is that direct visualization of the undermining plane is not achieved; however, direct visualization also is not obtained when undermining in the standard fashion unless the instruments are passed to the surgical assistant or the surgeon moves to the other side of the table.

Undermining can be performed safely without direct visualization as long as several rules are followed:

• The undermining plane is first established under direct visualization on the far side of the wound—at the 6-o’clock to 12-o’clock positions—and then followed to the area where direct visualization is not obtained.

• A blunt-tipped scissor is used to prevent penetrating trauma to neurovascular bundles. Blunt-tipped instruments allow more “feel” through tactile feedback to the surgeon and prevent accidental injury to these critical structures.

• A curved scissor is used with “tips up,” such that the surgeon does not unintentionally make the undermining plane deeper than anticipated.

Practice Implications

With practice, one can perform circumferential undermining independently with few alterations in stance and while maintaining a natural position throughout. Use of skin hooks to elevate the skin can further aid in visualizing the correct depth of undermining. If executed correctly, the reverse-grip technique can expand the surgeon’s work field, thus providing ease of dissection in difficult-to-reach areas.

- Chen DL, Carlson EO, Fathi R, et al. Undermining and hemostasis. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S201-S215. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000489

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002295

Practice Gap

One of the most important elements of successful reconstruction is effective undermining prior to placement of buried sutures. The main benefit of an evenly undermined plane is that tension is reduced, thus permitting seamless tissue mobilization and wound edge approximation.1

However, achieving a consistent and appropriate plane can present challenges in certain blind spots within one’s field of work. A right hand–dominant surgeon might find it difficult to undermine tissue between the 3-o’clock and 6-o’clock positions (Figure 1) and often must resort to unnatural positioning to obtain adequate reach.

We propose a technique of reversing the grip on undermining scissors that improves efficiency without sacrificing technique.

Technique

The surgeon simply grasps the ring handles with the ring finger and thumb with the tip pointing to the wrist (Figure 2). Most of the control comes from rotating the wrist while spreading with the thumb (Figure 3).

The main advantage of the reverse-grip technique is that it prevents abduction of the arm at the shoulder joint, which reduces shoulder fatigue and keeps the elbow close to the trunk and away from the sterile surgical field. Achieving optimal ergonomics during surgery has been shown to reduce pain and likely prolong the surgeon’s career.2

A limitation of the reverse-grip technique is that direct visualization of the undermining plane is not achieved; however, direct visualization also is not obtained when undermining in the standard fashion unless the instruments are passed to the surgical assistant or the surgeon moves to the other side of the table.

Undermining can be performed safely without direct visualization as long as several rules are followed:

• The undermining plane is first established under direct visualization on the far side of the wound—at the 6-o’clock to 12-o’clock positions—and then followed to the area where direct visualization is not obtained.

• A blunt-tipped scissor is used to prevent penetrating trauma to neurovascular bundles. Blunt-tipped instruments allow more “feel” through tactile feedback to the surgeon and prevent accidental injury to these critical structures.

• A curved scissor is used with “tips up,” such that the surgeon does not unintentionally make the undermining plane deeper than anticipated.

Practice Implications

With practice, one can perform circumferential undermining independently with few alterations in stance and while maintaining a natural position throughout. Use of skin hooks to elevate the skin can further aid in visualizing the correct depth of undermining. If executed correctly, the reverse-grip technique can expand the surgeon’s work field, thus providing ease of dissection in difficult-to-reach areas.

Practice Gap

One of the most important elements of successful reconstruction is effective undermining prior to placement of buried sutures. The main benefit of an evenly undermined plane is that tension is reduced, thus permitting seamless tissue mobilization and wound edge approximation.1

However, achieving a consistent and appropriate plane can present challenges in certain blind spots within one’s field of work. A right hand–dominant surgeon might find it difficult to undermine tissue between the 3-o’clock and 6-o’clock positions (Figure 1) and often must resort to unnatural positioning to obtain adequate reach.

We propose a technique of reversing the grip on undermining scissors that improves efficiency without sacrificing technique.

Technique

The surgeon simply grasps the ring handles with the ring finger and thumb with the tip pointing to the wrist (Figure 2). Most of the control comes from rotating the wrist while spreading with the thumb (Figure 3).

The main advantage of the reverse-grip technique is that it prevents abduction of the arm at the shoulder joint, which reduces shoulder fatigue and keeps the elbow close to the trunk and away from the sterile surgical field. Achieving optimal ergonomics during surgery has been shown to reduce pain and likely prolong the surgeon’s career.2

A limitation of the reverse-grip technique is that direct visualization of the undermining plane is not achieved; however, direct visualization also is not obtained when undermining in the standard fashion unless the instruments are passed to the surgical assistant or the surgeon moves to the other side of the table.

Undermining can be performed safely without direct visualization as long as several rules are followed:

• The undermining plane is first established under direct visualization on the far side of the wound—at the 6-o’clock to 12-o’clock positions—and then followed to the area where direct visualization is not obtained.

• A blunt-tipped scissor is used to prevent penetrating trauma to neurovascular bundles. Blunt-tipped instruments allow more “feel” through tactile feedback to the surgeon and prevent accidental injury to these critical structures.

• A curved scissor is used with “tips up,” such that the surgeon does not unintentionally make the undermining plane deeper than anticipated.

Practice Implications

With practice, one can perform circumferential undermining independently with few alterations in stance and while maintaining a natural position throughout. Use of skin hooks to elevate the skin can further aid in visualizing the correct depth of undermining. If executed correctly, the reverse-grip technique can expand the surgeon’s work field, thus providing ease of dissection in difficult-to-reach areas.

- Chen DL, Carlson EO, Fathi R, et al. Undermining and hemostasis. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S201-S215. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000489

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002295

- Chen DL, Carlson EO, Fathi R, et al. Undermining and hemostasis. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41(suppl 10):S201-S215. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000489

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002295

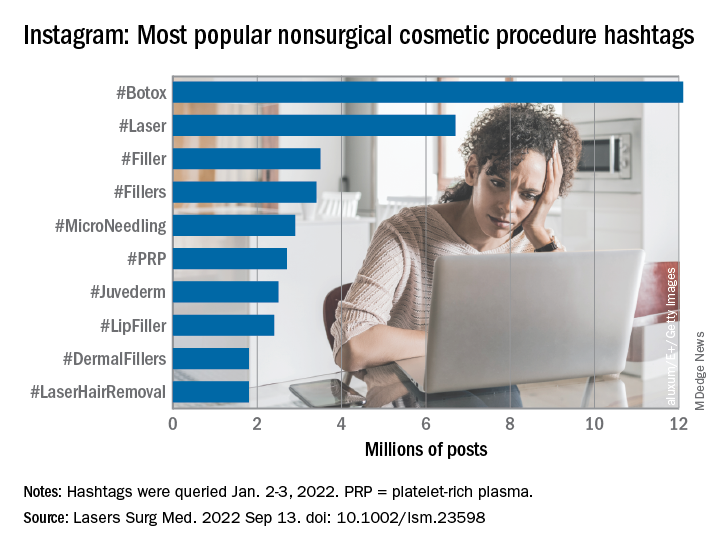

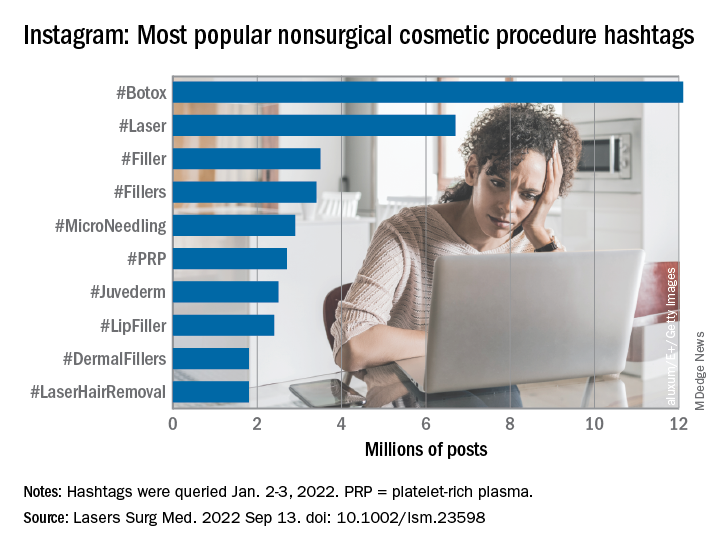

Instagram: Cosmetic procedures discussed without cosmetic experts

according to an analysis of related posts on the photo-sharing service.

“Given that there is little to no oversight on social networking sites, unqualified sources can widely disseminate misinformation resulting in misguided management or unnecessary procedures,” Taryn N. Murray, MD, and associates said in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

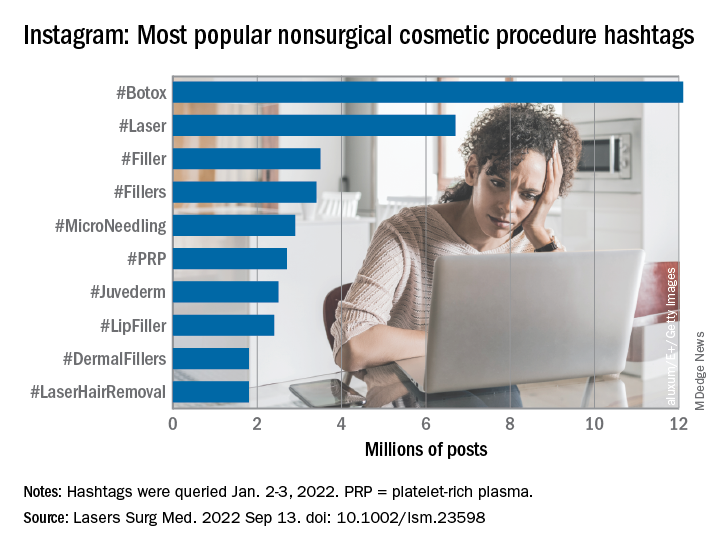

They generated a list of 25 hashtags related to nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, which were queried on Instagram on Jan. 2-3, 2022. The most popular was #Botox, with 12.1 million posts, followed by #Laser with 6.7 million, and #Filler with 3.5 million. Each of the 25 hashtags had at least 250,000 posts, they reported.

“Studies have shown that cosmetic patients and younger patients value social media when selecting a provider and patients often make treatment decisions based on social media,” they noted.

The bulk of the study involved “the first 10 posts displayed under the ‘Top’ section for each hashtag, as sorted by Instagram’s proprietary algorithm,” explained Dr. Murray and associates at the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston. The 250 posts eventually selected for inclusion each received scrutiny in terms of content type and creator credentials.

Physicians in core cosmetic specialties – dermatology, plastic surgery, facial plastic surgery, and oculoplastic surgery – created just 12% of those 250 posts, compared with 68% for nonphysician providers, 13% for consumers/others, and 8% for other physicians, they said.

Educational content made up the largest share (38%) of posts by core cosmetic physicians, with before-and-after next at 31%, self-promotional at 21%, and personal at 10%. Nonphysician providers were the most likely to create before-and-after (49% of their total) and self-promotional (28%) content, while consumers had the largest share of promotional posts (31%) and other physicians posted the most entertainment content (25%), the researchers said.

An overall look at the content shows that the largest proportion of all 250 posts included in the analysis involved before-and-after photos (45%), with self-promotion next at 23%. Education represented just 17% of the posting total for nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, with personal, entertainment, and promotional each at 5%, Dr. Murray and associates reported.

By recognizing “the role social media plays in patients’ understanding of and desire to undergo nonsurgical cosmetic procedures” and “increasing their presence on Instagram, core cosmetic physicians can provide patient education, counteract misinformation, and raise awareness on training and qualifications,” they wrote.

The study authors did not provide any disclosures regarding funding or financial conflicts.

according to an analysis of related posts on the photo-sharing service.

“Given that there is little to no oversight on social networking sites, unqualified sources can widely disseminate misinformation resulting in misguided management or unnecessary procedures,” Taryn N. Murray, MD, and associates said in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

They generated a list of 25 hashtags related to nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, which were queried on Instagram on Jan. 2-3, 2022. The most popular was #Botox, with 12.1 million posts, followed by #Laser with 6.7 million, and #Filler with 3.5 million. Each of the 25 hashtags had at least 250,000 posts, they reported.

“Studies have shown that cosmetic patients and younger patients value social media when selecting a provider and patients often make treatment decisions based on social media,” they noted.

The bulk of the study involved “the first 10 posts displayed under the ‘Top’ section for each hashtag, as sorted by Instagram’s proprietary algorithm,” explained Dr. Murray and associates at the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston. The 250 posts eventually selected for inclusion each received scrutiny in terms of content type and creator credentials.

Physicians in core cosmetic specialties – dermatology, plastic surgery, facial plastic surgery, and oculoplastic surgery – created just 12% of those 250 posts, compared with 68% for nonphysician providers, 13% for consumers/others, and 8% for other physicians, they said.

Educational content made up the largest share (38%) of posts by core cosmetic physicians, with before-and-after next at 31%, self-promotional at 21%, and personal at 10%. Nonphysician providers were the most likely to create before-and-after (49% of their total) and self-promotional (28%) content, while consumers had the largest share of promotional posts (31%) and other physicians posted the most entertainment content (25%), the researchers said.

An overall look at the content shows that the largest proportion of all 250 posts included in the analysis involved before-and-after photos (45%), with self-promotion next at 23%. Education represented just 17% of the posting total for nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, with personal, entertainment, and promotional each at 5%, Dr. Murray and associates reported.

By recognizing “the role social media plays in patients’ understanding of and desire to undergo nonsurgical cosmetic procedures” and “increasing their presence on Instagram, core cosmetic physicians can provide patient education, counteract misinformation, and raise awareness on training and qualifications,” they wrote.

The study authors did not provide any disclosures regarding funding or financial conflicts.

according to an analysis of related posts on the photo-sharing service.

“Given that there is little to no oversight on social networking sites, unqualified sources can widely disseminate misinformation resulting in misguided management or unnecessary procedures,” Taryn N. Murray, MD, and associates said in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine.

They generated a list of 25 hashtags related to nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, which were queried on Instagram on Jan. 2-3, 2022. The most popular was #Botox, with 12.1 million posts, followed by #Laser with 6.7 million, and #Filler with 3.5 million. Each of the 25 hashtags had at least 250,000 posts, they reported.

“Studies have shown that cosmetic patients and younger patients value social media when selecting a provider and patients often make treatment decisions based on social media,” they noted.

The bulk of the study involved “the first 10 posts displayed under the ‘Top’ section for each hashtag, as sorted by Instagram’s proprietary algorithm,” explained Dr. Murray and associates at the Dermatology and Laser Surgery Center in Houston. The 250 posts eventually selected for inclusion each received scrutiny in terms of content type and creator credentials.

Physicians in core cosmetic specialties – dermatology, plastic surgery, facial plastic surgery, and oculoplastic surgery – created just 12% of those 250 posts, compared with 68% for nonphysician providers, 13% for consumers/others, and 8% for other physicians, they said.

Educational content made up the largest share (38%) of posts by core cosmetic physicians, with before-and-after next at 31%, self-promotional at 21%, and personal at 10%. Nonphysician providers were the most likely to create before-and-after (49% of their total) and self-promotional (28%) content, while consumers had the largest share of promotional posts (31%) and other physicians posted the most entertainment content (25%), the researchers said.

An overall look at the content shows that the largest proportion of all 250 posts included in the analysis involved before-and-after photos (45%), with self-promotion next at 23%. Education represented just 17% of the posting total for nonsurgical cosmetic procedures, with personal, entertainment, and promotional each at 5%, Dr. Murray and associates reported.

By recognizing “the role social media plays in patients’ understanding of and desire to undergo nonsurgical cosmetic procedures” and “increasing their presence on Instagram, core cosmetic physicians can provide patient education, counteract misinformation, and raise awareness on training and qualifications,” they wrote.

The study authors did not provide any disclosures regarding funding or financial conflicts.

FROM LASERS IN SURGERY AND MEDICINE

Artemisia capillaris extract

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary

Many botanical ingredients from Asia are making their way into skin care products in the USA. A. capillaris extract is an example and may have utility in treating hyperpigmentation-associated skin issues such as melasma. Its inhibitory effects on both inflammation and melanin production in addition to possible antioxidant activity make it an interesting compound worthy of more scrutiny.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Bora KS and Sharma A. Pharm Biol. 2011 Jan;49(1):101-9.

2. Kwon OS et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Sep;34(9):1561-9.

3. Hsueh TP et al. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 8;9(10):1412.

4. Dolinska MB et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 3;21(1):331.

5. Yeo D et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Mar;99:681-7.

6. Kim YS et al. J Food Sci. 2008 Jan;73(1):T16-20.

7. Kim MJ et al. Mol Med Rep. 2022 Apr;25(4):113.

8. Tabassum N et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7823541.

9. Lee SY et al. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):923-2.

10. Lee SY et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 Aug 19;2018:3610494.

11. Ha H et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Mar 14;14:100.

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary

Many botanical ingredients from Asia are making their way into skin care products in the USA. A. capillaris extract is an example and may have utility in treating hyperpigmentation-associated skin issues such as melasma. Its inhibitory effects on both inflammation and melanin production in addition to possible antioxidant activity make it an interesting compound worthy of more scrutiny.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Bora KS and Sharma A. Pharm Biol. 2011 Jan;49(1):101-9.

2. Kwon OS et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Sep;34(9):1561-9.

3. Hsueh TP et al. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 8;9(10):1412.

4. Dolinska MB et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 3;21(1):331.

5. Yeo D et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Mar;99:681-7.

6. Kim YS et al. J Food Sci. 2008 Jan;73(1):T16-20.

7. Kim MJ et al. Mol Med Rep. 2022 Apr;25(4):113.

8. Tabassum N et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7823541.

9. Lee SY et al. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):923-2.

10. Lee SY et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 Aug 19;2018:3610494.

11. Ha H et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Mar 14;14:100.

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary

Many botanical ingredients from Asia are making their way into skin care products in the USA. A. capillaris extract is an example and may have utility in treating hyperpigmentation-associated skin issues such as melasma. Its inhibitory effects on both inflammation and melanin production in addition to possible antioxidant activity make it an interesting compound worthy of more scrutiny.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Bora KS and Sharma A. Pharm Biol. 2011 Jan;49(1):101-9.

2. Kwon OS et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Sep;34(9):1561-9.

3. Hsueh TP et al. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 8;9(10):1412.

4. Dolinska MB et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 3;21(1):331.

5. Yeo D et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Mar;99:681-7.

6. Kim YS et al. J Food Sci. 2008 Jan;73(1):T16-20.

7. Kim MJ et al. Mol Med Rep. 2022 Apr;25(4):113.

8. Tabassum N et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7823541.

9. Lee SY et al. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):923-2.

10. Lee SY et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 Aug 19;2018:3610494.

11. Ha H et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Mar 14;14:100.

Low-dose oral minoxidil for the treatment of alopecia

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

Other than oral finasteride, vitamins, and topicals, there has been little advancement in the treatment of AGA leaving many (including me) desperate for anything remotely new.

Oral minoxidil is a peripheral vasodilator approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with hypertensive disease taken at doses ranging between 10 mg to 40 mg daily. Animal studies have shown that minoxidil affects the hair growth cycle by shortening the telogen phase and prolonging the anagen phase.

Recent case studies have also shown growing evidence for the off-label use of low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) for treating different types of alopecia. Topical minoxidil is metabolized into its active metabolite minoxidil sulfate, by sulfotransferase enzymes located in the outer root sheath of hair follicles. The expression of sulfotransferase varies greatly in the scalp of different individuals, and this difference is directly correlated to the wide range of responses to minoxidil treatment. LDOM is, however, more widely effective because it requires decreased follicular enzymatic activity to form its active metabolite as compared with its topical form.

In a retrospective series by Beach and colleagues evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of LDOM for treating AGA, there was increased scalp hair growth in 33 of 51 patients (65%) and decreased hair shedding in 14 of the 51 patients (27%) with LDOM. Patients with nonscarring alopecia were most likely to show improvement. Side effects were dose dependent and infrequent. The most frequent adverse effects were hypertrichosis, lightheadedness, edema, and tachycardia. No life-threatening adverse effects were observed. Although there has been a recently reported case report of severe pericardial effusion, edema, and anasarca in a woman with frontal fibrosing alopecia treated with LDOM, life threatening side effects are rare.3

To compare the efficacy of topical versus oral minoxidil, Ramos and colleagues performed a 24-week prospective study of low-dose (1 mg/day) oral minoxidil, compared with topical 5% minoxidil, in the treatment of 52 women with female pattern hair loss. Blinded analysis of trichoscopic images were evaluated to compare the change in total hair density in a target area from baseline to week 24 by three dermatologists.

Results after 24 weeks of treatment showed an increase in total hair density (12%) among the women taking oral minoxidil, compared with 7.2% in women who applied topical minoxidil (P =.09).

In the armamentarium of hair-loss treatments, dermatologists have limited choices. LDOM can be used in patients with both scarring and nonscarring alopecia if monitored regularly. Treatment doses I recommend are 1.25-5 mg daily titrated up slowly in properly selected patients without contraindications and those who are not taking other vasodilators. Self-reported dizziness, edema, and headache are common and treatments for facial hypertrichosis in women are always discussed. Clinical efficacy can be evaluated after 10-12 months of therapy and concomitant spironolactone can be given to mitigate the side effect of hypertrichosis.Patient selection is crucial as patients with severe scarring alopecia and those with active inflammatory diseases of the scalp may not see similar results. Similar to other hair loss treatments, treatment courses of 10-12 months are often needed to see visible signs of hair growth.

Dr. Talakoub and Naissan O. Wesley, MD, are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Write to them at [email protected]. Dr. Talakoub had no relevant disclosures.

References

Beach RA et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):761-3.

Dlova et al. JAAD Case Reports. 2022 Oct;28:94-6.

Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jan;84(1):222-3.

Ramos PM et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jan;34(1):e40-1.

Ramos PM et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jan;82(1):252-3.

Randolph M and Tosti A. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Mar;84(3):737-46.

Vañó-Galván S et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Jun;84(6):1644-51.

FDA approves Botox challenger Daxxify for frown lines

The U.S. .

According to a company news release, Daxxify, an acetylcholine release inhibitor and neuromuscular blocking agent, is the first peptide-formulated, long-acting neuromodulator approved for this indication.

The approval of Daxxify, manufactured by Revance Therapeutics, was based on the data from the SAKURA phase 3 clinical trial program, which included more than 2,700 adults who received roughly 4,200 treatments, according to the company.

About three-quarters of participants achieved at least a two-grade improvement in glabellar lines at week 4 as judged by both investigator and patient, and 98% achieved “none or mild wrinkle severity” at week 4 per investigator assessment, the company said.

The median duration of treatment effect was 6 months, with some patients maintaining treatment results at 9 months, compared with a 3- to 4-month duration of treatment effect with conventional neuromodulators.

“Compelling data from the largest phase 3 clinical program ever conducted for glabellar lines demonstrated that Daxxify was well tolerated and achieved clinically significant improvement with long-lasting results and high patient satisfaction,” SAKURA investigator Jeffrey Dover, MD, co-director of SkinCare Physicians, Chestnut Hill, Mass., said in the news release.

“Notably,” said Dr. Dover, “Daxxify was able to demonstrate a long duration of effect while only utilizing 0.18 ng of core active ingredient in the 40-unit labeled indication for glabellar lines.”

Daxxify has a safety profile in line with other currently available neuromodulators in the aesthetics market, the company said, with no serious treatment-related adverse events reported in clinical trial participants.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the pivotal studies were headache (6%), eyelid ptosis (2%) and facial paresis, including facial asymmetry (1%).

Daxxify is contraindicated in adults with hypersensitivity to any botulinum toxin preparation or any of the components in the formulation and infection at the injection sites.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. .

According to a company news release, Daxxify, an acetylcholine release inhibitor and neuromuscular blocking agent, is the first peptide-formulated, long-acting neuromodulator approved for this indication.

The approval of Daxxify, manufactured by Revance Therapeutics, was based on the data from the SAKURA phase 3 clinical trial program, which included more than 2,700 adults who received roughly 4,200 treatments, according to the company.

About three-quarters of participants achieved at least a two-grade improvement in glabellar lines at week 4 as judged by both investigator and patient, and 98% achieved “none or mild wrinkle severity” at week 4 per investigator assessment, the company said.

The median duration of treatment effect was 6 months, with some patients maintaining treatment results at 9 months, compared with a 3- to 4-month duration of treatment effect with conventional neuromodulators.

“Compelling data from the largest phase 3 clinical program ever conducted for glabellar lines demonstrated that Daxxify was well tolerated and achieved clinically significant improvement with long-lasting results and high patient satisfaction,” SAKURA investigator Jeffrey Dover, MD, co-director of SkinCare Physicians, Chestnut Hill, Mass., said in the news release.

“Notably,” said Dr. Dover, “Daxxify was able to demonstrate a long duration of effect while only utilizing 0.18 ng of core active ingredient in the 40-unit labeled indication for glabellar lines.”

Daxxify has a safety profile in line with other currently available neuromodulators in the aesthetics market, the company said, with no serious treatment-related adverse events reported in clinical trial participants.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the pivotal studies were headache (6%), eyelid ptosis (2%) and facial paresis, including facial asymmetry (1%).

Daxxify is contraindicated in adults with hypersensitivity to any botulinum toxin preparation or any of the components in the formulation and infection at the injection sites.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. .

According to a company news release, Daxxify, an acetylcholine release inhibitor and neuromuscular blocking agent, is the first peptide-formulated, long-acting neuromodulator approved for this indication.

The approval of Daxxify, manufactured by Revance Therapeutics, was based on the data from the SAKURA phase 3 clinical trial program, which included more than 2,700 adults who received roughly 4,200 treatments, according to the company.

About three-quarters of participants achieved at least a two-grade improvement in glabellar lines at week 4 as judged by both investigator and patient, and 98% achieved “none or mild wrinkle severity” at week 4 per investigator assessment, the company said.

The median duration of treatment effect was 6 months, with some patients maintaining treatment results at 9 months, compared with a 3- to 4-month duration of treatment effect with conventional neuromodulators.

“Compelling data from the largest phase 3 clinical program ever conducted for glabellar lines demonstrated that Daxxify was well tolerated and achieved clinically significant improvement with long-lasting results and high patient satisfaction,” SAKURA investigator Jeffrey Dover, MD, co-director of SkinCare Physicians, Chestnut Hill, Mass., said in the news release.

“Notably,” said Dr. Dover, “Daxxify was able to demonstrate a long duration of effect while only utilizing 0.18 ng of core active ingredient in the 40-unit labeled indication for glabellar lines.”

Daxxify has a safety profile in line with other currently available neuromodulators in the aesthetics market, the company said, with no serious treatment-related adverse events reported in clinical trial participants.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the pivotal studies were headache (6%), eyelid ptosis (2%) and facial paresis, including facial asymmetry (1%).

Daxxify is contraindicated in adults with hypersensitivity to any botulinum toxin preparation or any of the components in the formulation and infection at the injection sites.

Full prescribing information is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Blue light from cell phones and other devices could be causing wrinkles

Blue light from screens on smartphones, computers, and other gadgets “may have detrimental effects on a wide range of cells in our body, from skin and fat cells to sensory neurons,” Oregon State University scientist Jadwiga Giebultowicz, PhD, said of the study, which was published in the journal Frontiers in Aging.

“Our study suggests that avoidance of excessive blue light exposure may be a good anti-aging strategy,” Dr. Giebultowicz added.

Ultraviolet rays from the sun harm skin appearance and health. Doctors are continuing to study the damage caused by the screens of devices that most people are exposed to throughout the day. These devices emit blue light.

“Aging occurs in various ways, but on a cellular level, we age when cells stop repairing and producing new healthy cells. And cells that aren’t functioning properly are more likely to self destruct – which has ramifications not only in terms of appearance but for the whole body,” the New York Post wrote. “It’s the reason why the elderly take longer to heal, and their bones and organs begin to deteriorate.”