User login

Treating stress urinary incontinence with suburethral slings

- Suburethral sling procedures are effective in treating patients with urethral hypermobility, intrinsic sphincter deficiency, low-pressure urethras, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

- Autologous slings may be a better choice in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs.

- For both the tension-free vaginal tape and SPARC slings, mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides and inject 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked regions.

- Once the trocars are in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test to confirm continence.

When the suburethral sling was first described in 1907 by von Giordano, it entailed placing autologous tissue underneath the bladder neck and suspending it superiorly. Complications including urethral erosion, infection, bleeding, and fistula formation led many surgeons to use it sparingly.

Fast forward to the 21st century: Synthetic materials and new techniques were introduced, simplifying the sling procedures and raising the long-term success rates to 84%.1 As a result, slings now stand at the forefront of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) treatment. Among advances are the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) sling (Gynecare, a division of Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) and the SPARC sling (American Medical Systems, Inc., Minnetonka, Minn). The former, approved in the U.S. in 1998, calls for another look due to of the recent publication of a Cochrane review of outcomes studies, while the latter, approved by the FDA in August 2001, is the newest technique deserving examination. Clearly, with 83,010 incontinence procedures performed in the U.S. in 1999,2 a detailed look at the suburethral sling is warranted. Here, we review materials, indications, techniques, complications, and outcomes.

Materials

The choice of material—either organic or synthetic—depends on several factors: availability, cost, patient and surgeon preference, and clinical variables. (TABLE 1) outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each material type. Organic slings include autologous tissues (rectus fascia and fascia lata graft), and allografts or xenografts (cadaveric fascia lata graft, human dermal graft, or porcine small intestine and dermal graft). Synthetic slings are made of polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, and polypropylene.

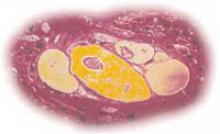

While sling procedures utilizing organic materials do have their benefits, synthetic slings, particularly the polypropylene mesh used in TVT and SPARC, have proven to be a stable material unlikely to deteriorate with time. Further, increased collagen metabolism around this synthetic sling promotes an ingrowth of tissue through the mesh.

TABLE 1

Slings: advantages and disadvantages of various materials

| SLING MATERIAL | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous tissues (rectus fascia, fascia lata, or vaginal wall) |

|

|

| Allografts (cadaveric fascia lata or dermis) |

|

|

| Xenografts (porcine dermis or small intestine) | ||

| Synthetic mesh (polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, or polypropylene) |

|

|

Indications

Suburethral sling procedures are typically used for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence (GSUI), in which the urethra becomes either hypermobile and unstable or its intrinsic sphincter becomes incompetent. In fact, slings are technically easier to place in patients with anatomic urethrovesical junction hypermobility compared to those with fixed urethras. Several authors also have suggested the sling’s advantage in patients with low-pressure urethras.3

Use urodynamic criteria to diagnose intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), which is defined as a Valsalva leak point pressure of less than 60 cm water or maximal urethral closure pressure of less than 20 cm water. (Bear in mind, however, that these cut-off criteria are controversial.4,5)

Also, consider slings in patients with recurrent GSUI, inherited collagen deficiency, and increased abdominal pressure (e.g., women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, or high-impact physical activity). The sling also can be used as an adjunct to other transvaginal surgeries (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair).

Autologous slings may be a better choice than synthetic slings in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs. In these instances, the patient may be at-risk for postoperative vaginal necrosis or erosion.6 Due to their biocompatibility, autologous slings are more likely to heal over a vaginal erosion and less likely to infect or erode into the urethra. In any event, urogenital atrophy should be treated with local estrogen preoperatively to prevent some of these complications.

Technique

Conventionally, suburethral slings were placed via a combined vaginal and abdominal approach into the retropubic space of Retzius. Alternatively, the procedure could be performed abdominally by creating a suburethral tunnel via pelvic incisions, but this is the most difficult route.

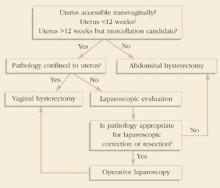

Most recently, technological advances have simplified the vaginal approach, which utilizes minimal suburethral dissection and small suprapubic incisions. This technique is subdivided into “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches. In the bottom-up TVT, the sling is inserted into a vaginal incision and threaded up through the patient’s pelvis, exiting from a small suprapubic incision. The topdown SPARC entails a reverse approach, starting from a suprapubic incision and exiting from a vaginal incision. New modifications allow for an abdominal TVT approach, as well, which we describe in detail in a later section.

Surgeons who are familiar with traditional needle suspensions may be more comfortable with the top-down approach. The need for concomitant surgery (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair) not only determines the type of incontinence procedure, but also dictates the approach.

Preparing the patient. Place the patient under regional or local anesthesia with sedation so that an intraoperative cough stress test can be performed. Then administer an intravenous dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Insert a 16 to 18 French Foley catheter into the urethra. Mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides of the patient. Inject approximately 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked areas. We typically use 60 cc of 0.25% bupivicaine with epinephrine, diluted 1:1 with 60 cc of normal saline. After administering the local anesthetic suprapubically, inject a similar solution into the anterior vaginal wall suburethrally in the midline and laterally toward the retropubic tunnels.

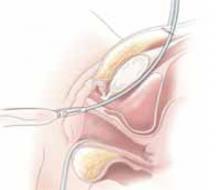

Making the incisions. Both the TVT and SPARC techniques utilize the same type and location of incisions. As such, make a 0.5-cm incision into the abdominal skin on each side of the midline, approximately 1 cm lateral to midline and 1 cm above the pubic symphsis. Next, make a 1.5- to 2-cm vertical incision in the vaginal mucosa, starting 1.5 cm from the urethral meatus (FIGURE 1). Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the pubocervical fascia sub- and para-urethrally on both sides (FIGURE 2). Insert a Foley catheter guide (similar to the Lowsley retractor) into the catheter and deviate it to the ipsilateral side, thereby retracting the bladder neck to the contralateral side. Proceed with the placement of either the TVT or SPARC sling.

Placing the TVT sling. Attach the TVT introducer to the curved needle trocar on 1 end of the polypropylene sling. Insert the trocar with the tape attached into the vaginal incision and push through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone (FIGURES 3 and 4). Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side (FIGURE 5). It is important to not deviate too laterally, medially, or cephalad during trocar insertion to prevent vessel, bladder, or bowel injury. Perform a cystoscopy to rule out cystotomy. Place the second trocar in a similar manner on the opposite side. After both trocars have been pulled through their respective incisions, perform a tension test.

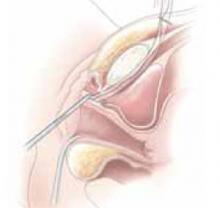

Placing the SPARC/abdominal TVT sling. Guide the abdominal needles through the previously marked suprapubic incision and the patient’s retropubic cavity (keeping the needle behind the pubic bone), to a finger placed in the vaginal incision (FIGURE 6). Snap the abdominal needle guides with the attached polypropylene mesh to the sling connectors (FIGURE 7). Bring the abdominal needles through the suprapubic incisions. Perform a tension test. As with the TVT sling, perform a cystoscopy after each needle placement to rule out cystotomy. Then pass the sling through the tunnel.

Testing for continence. Once the sling is in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test. Adjust sling tension by pulling up on both sling arms until only a few drops of leakage are noted. It is important not to secure the sling too tightly as this may lead to urinary retention, detrusor instability, or urethral erosion. We prefer placing a hemostat between the sling tape and the urethra to avoid over tightening.

Suspending the sling arms. Remove the plastic sheaths after tension adjustment and cut the sling flush with the skin (FIGURE 8). Compared to the conventional bone-anchored slings, the newer tension-free sling devices are not anchored but instead suspended through the retropubic space. At first, the sling is held in place by friction from the opposing tissues. Over time, collagen formation fixes the mesh more strongly within the suburethral and paravaginal tissues.

Finally, close the suprapubic and vaginal incisions with absorbable sutures.

Placing autologous or allogenic slings. Fashion the graft, typically 2 cm wide and 10 to 12 cm long, with permanent sutures at the edges. Make a 1-cm incision into the suprapubic rectus fascia. Use either a Stamey-type needle trocar or uterine packing forceps and guide the instrument “top down” from the retropubic incision to the vaginal tunnel. The tunnel is made directly into the retropubic space from the vaginal incision. Bring the sling arms up on each side. Attach the arms to the rectus fascia and tie them down once cystoscopy and the tension test are complete.

The sling also can be performed with bone anchors placed through the vaginal incision into the pubic bone. Placement requires vaginal dissection into the retropubic space with no suprapubic incision. Once anchored, the sutures are then passed through the chosen graft materials and tied down. Bear in mind that anchoring into the periosteum of the pubic bone may cause severe osteomyelitis or osteitis pubis, though the actual incidence is unknown.7

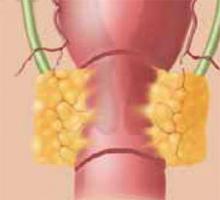

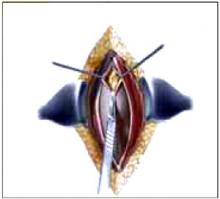

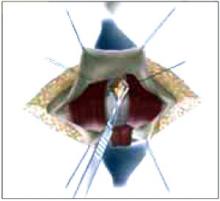

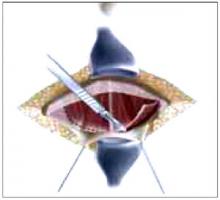

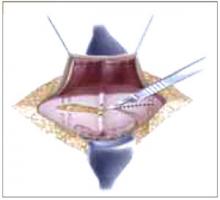

FIGURE 1 Surgical steps for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT)

Place a Sims speculum into the vagina and make a vertical incision 1.5 cm from the external urethra meatus.

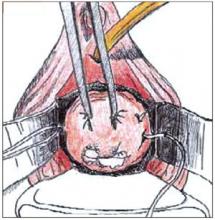

FIGURE 2

Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the underlying fascia bilaterally. Insert a Foley catheter with guide.

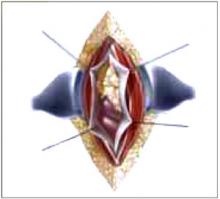

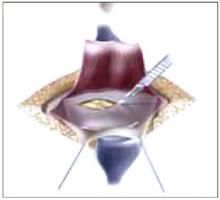

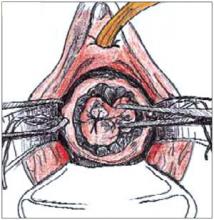

FIGURE 3

Place TVT trocars through the vaginal incision. Place abdominal guides suprapubically and attach them to the TVT trocar tip.

FIGURE 4

Push the tape through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone.

FIGURE 5

Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side.

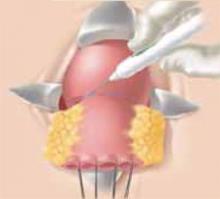

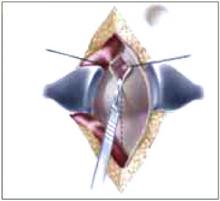

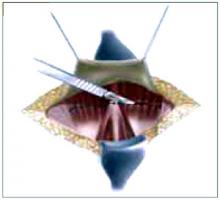

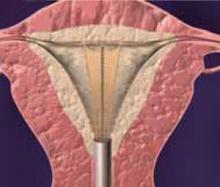

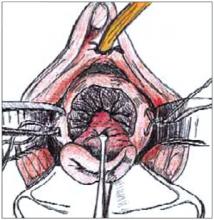

FIGURE 6 Surgical steps for SPARC

Guide the needle down the posterior side of the pubic bone, keeping the needle tip in contact with the pubic bone.

FIGURE 7

Snap the needle guide and sling onto the sling connectors and pull through the suprapubic incision.

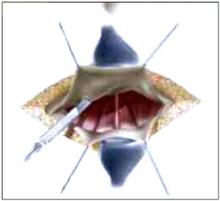

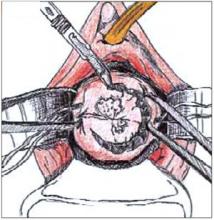

FIGURE 8

Perform a tension test. Remove the plastic sheaths and cut the sling flush with the skin.

Complications

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications include bladder perforation, vaginal or retropubic bleeding, wound or urinary tract infection (UTI), and short-term urinary retention. Possible long-term problems include urethral or vaginal erosion, mesh infection, prolonged voiding dysfunction, fistula formation, or de novo urge incontinence (TABLE 2).

Specifically, the TVT sling, which has been placed in more than 50,000 women in the U.S. and 200,000 worldwide, carries the potential for significant vascular injury and bowel perforation. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported 4 deaths (2 from unrecognized bowel injuries, 1 from retropubic bleeding in a patient with a bleeding disorder, and 1 from a heart attack more than 1 week after an incontinence repair procedure complicated by a vascular injury); 168 device malfunctions (mostly tape or sheath detachment from the trocar); and 128 other injuries, including bowel perforations and major vascular injuries to the obturator, external iliac, femoral, or inferior epigastrics (TABLE 3).8 In a review of 1,455 TVT sling cases at 38 hospitals, Kuuva and Nilsson9 found bladder perforation in 3.8% of the patients and retropubic hematoma in 1.9%, along with 1 case of vesicovaginal fistula, 1 obturator nerve injury, and 1 epigastric vessel injury.

According to the FDA, there have been 2 complications reported with the SPARC sling system. Both involved vaginal erosion subsequently repaired by oversewing the vaginal mucosa. One of these complications occurred in a woman undergoing her fourth vaginal procedure who was therefore deemed to have “poor tissue.”8

TABLE 2

Suburethral sling complications1

| COMPLICATION | 1,715 AUTOLOGOUS | 1,515 SYNTHETIC |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal erosion | 1 (.0001%) | 10 (.007%) |

| Urethral erosion | 5 (.003%) | 27 (.02%) |

| Fistula | 6 (.003%) | 4 (.002%) |

| Wound sinus | 3 (.002%) | 11 (.007%) |

| Wound infection | 11 (.006%) | 15 (.009%) |

| Seroma | 6 (.003%) | 1 (.0007%) |

TABLE 3

TVT complications in 200,000 procedures worldwide

| COMPLICATION | U.S. | WORLD | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular injury | 3 | 25 | 28 |

| Vaginal mesh exposure | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Urethral erosion | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Bowel perforation | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Nerve injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Outcomes studies

Unfortunately, most of the published clinical studies on the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence suffer from inadequate follow-up and sample size, unclear patient selection criteria, and poor postoperative documentation, especially with respect to quality of life. However, multiple studies to assess the effectiveness and safety of TVT slings have been published. The following is an outline of these preliminary yet important findings.

In 2002, the Cochrane Database evaluated 7 randomized and quasi-randomized trials of suburethral slings for the treatment of urinary incontinence.10 Of 682 women evaluated, 457 had some type of suburethral sling procedure. Four trials compared slings to retropubic urethropexies, 1 compared slings to Stamey needle suspensions, and 2 compared the use of different sling materials. The results indicated that the data were insufficient to suggest that slings were more effective than other incontinence procedures or that slings were associated with fewer postoperative complications. While TVT slings did provide similar cure rates as open retropubic urethropexy, research is still lacking with respect to other types of slings. More studies comparing TVT slings to traditional pubovaginal slings also are needed before the 2 can be deemed equivalent.

In Sweden and Finland, where the TVT procedure was developed,11 85 patients who had undergone the procedure were evaluated at 48 to 70 months. Of those, 84.7% were completely cured of stress incontinence, 10.6% had significantly improved symptoms, and 4.7% were regarded as failures.

A recent well-designed, multicenter, randomized, prospective trial in the U.K. and Ireland compared 146 open Burch colposuspensions to 170 TVTs. Similar cure rates (57% and 66%, respectively) were reported.12 Although these rates are low compared to the Nordic nonrandomized TVT studies mentioned, the U.K./Ireland outcome criteria were particularly stringent and included a negative cystometrogram for stress incontinence and negative pad test. These differences in reported success rates highlight the importance of clearly defining objective outcomes criteria from randomized trials.

Nonetheless, the U.K./Ireland study showed that TVT is less invasive than the Burch procedure and is associated with shorter recovery periods and greater cost savings. Follow-up on complications (bladder perforation and hematoma in TVTs and incisional hernia formation in Burch colposuspensions) will be the most crucial aspect of this study.13

Clearly, the question of whether a Burch retropubic urethropexy or a suburethral sling procedure is better for SUI needs to be further investigated. Weber and Walters sought to answer this question by developing a decision analytical model (without the aid of randomized, controlled trials) and discovered similar cure rates.14 However, there were higher rates of urinary retention and detrusor instability associated with the traditional pubovaginal sling. But, most importantly, sensitivity analyses proved that if the rate of permanent urinary retention after a sling procedure was less than 9%—as in most sling series—the overall effectiveness of slings was higher than that of the Burch.

Conclusion

The suburethral sling procedure has undergone many modifications since its first description nearly a century ago. As such, Ob/Gyns need to familiarize themselves with the current options. Typically, we perform up to 6 suburethral sling procedures per month. Of those, 50% are referrals from failed incontinence procedures. Recently, we have made the switch from using autologous slings to tension-free type slings due to ease and good outcomes. While more data from randomized, prospective, multicenter trials are needed to determine the best approach for individual patients, surgeons should become comfortable with the technique that works best for them.

The authors report no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, et al. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 1997;875-880.

2. Nihira MA, Schaffer JI. Surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence in 1999. Presented at: 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; March 6, 2002; Dallas, Texas.

3. Kobashi KC, Leach GE. Stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:285-290.

4. Bowen LW, Sand PK, Ostergard DR, Franti CE. Unsuccessful Burch retropubic urethropexy: a case-controlled urodynamic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:452-458.

5. Bump RC, Coates KW, Cundiff GW, Harris RL, Weidner AC. Diagnosing intrinsic sphincteric deficiency: Comparing urethral closure pressure, urethral axis, and Valsalva leak point pressures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:303-310.

6. Nichols DH, Randal CL. Operations for urinary stress incontinence. In: Vaginal Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996;402-415.

7. Rackley RR, Abdelmalak JB, Madjar S, Yanilmaz A, Appell RA, Tchetgen MB. Bone anchor infections in female pelvic reconstructive procedures: a literature review of series and case reports. J Urol. 2001;165:1975-1978.

8. Food and Drug Administration manufacturer and user facility device experience database. Available at: www.fda.gov/cdrh/maude.html. Accessed November 12, 2002.

9. Kuuva N, Nilsson CG. A nationwide analysis of complications associated with the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:394.-

10. Bezerra CA, Bruschini H. Suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001754.-

11. Nilsson CG, Kuuva N, Falconer C, Rezapour M, Ulmsten U. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure (TVT) for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(suppl 2):S5-S8.

12. Ward KL, Hilton P, Browning J. A randomized trial of colposuspension and tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for primary genuine stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:386.-

13. Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325:67.-

14. Weber A, Walters M. Burch procedure compared with sling for stress urinary incontinence: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:867-873.

- Suburethral sling procedures are effective in treating patients with urethral hypermobility, intrinsic sphincter deficiency, low-pressure urethras, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

- Autologous slings may be a better choice in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs.

- For both the tension-free vaginal tape and SPARC slings, mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides and inject 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked regions.

- Once the trocars are in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test to confirm continence.

When the suburethral sling was first described in 1907 by von Giordano, it entailed placing autologous tissue underneath the bladder neck and suspending it superiorly. Complications including urethral erosion, infection, bleeding, and fistula formation led many surgeons to use it sparingly.

Fast forward to the 21st century: Synthetic materials and new techniques were introduced, simplifying the sling procedures and raising the long-term success rates to 84%.1 As a result, slings now stand at the forefront of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) treatment. Among advances are the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) sling (Gynecare, a division of Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) and the SPARC sling (American Medical Systems, Inc., Minnetonka, Minn). The former, approved in the U.S. in 1998, calls for another look due to of the recent publication of a Cochrane review of outcomes studies, while the latter, approved by the FDA in August 2001, is the newest technique deserving examination. Clearly, with 83,010 incontinence procedures performed in the U.S. in 1999,2 a detailed look at the suburethral sling is warranted. Here, we review materials, indications, techniques, complications, and outcomes.

Materials

The choice of material—either organic or synthetic—depends on several factors: availability, cost, patient and surgeon preference, and clinical variables. (TABLE 1) outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each material type. Organic slings include autologous tissues (rectus fascia and fascia lata graft), and allografts or xenografts (cadaveric fascia lata graft, human dermal graft, or porcine small intestine and dermal graft). Synthetic slings are made of polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, and polypropylene.

While sling procedures utilizing organic materials do have their benefits, synthetic slings, particularly the polypropylene mesh used in TVT and SPARC, have proven to be a stable material unlikely to deteriorate with time. Further, increased collagen metabolism around this synthetic sling promotes an ingrowth of tissue through the mesh.

TABLE 1

Slings: advantages and disadvantages of various materials

| SLING MATERIAL | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous tissues (rectus fascia, fascia lata, or vaginal wall) |

|

|

| Allografts (cadaveric fascia lata or dermis) |

|

|

| Xenografts (porcine dermis or small intestine) | ||

| Synthetic mesh (polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, or polypropylene) |

|

|

Indications

Suburethral sling procedures are typically used for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence (GSUI), in which the urethra becomes either hypermobile and unstable or its intrinsic sphincter becomes incompetent. In fact, slings are technically easier to place in patients with anatomic urethrovesical junction hypermobility compared to those with fixed urethras. Several authors also have suggested the sling’s advantage in patients with low-pressure urethras.3

Use urodynamic criteria to diagnose intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), which is defined as a Valsalva leak point pressure of less than 60 cm water or maximal urethral closure pressure of less than 20 cm water. (Bear in mind, however, that these cut-off criteria are controversial.4,5)

Also, consider slings in patients with recurrent GSUI, inherited collagen deficiency, and increased abdominal pressure (e.g., women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, or high-impact physical activity). The sling also can be used as an adjunct to other transvaginal surgeries (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair).

Autologous slings may be a better choice than synthetic slings in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs. In these instances, the patient may be at-risk for postoperative vaginal necrosis or erosion.6 Due to their biocompatibility, autologous slings are more likely to heal over a vaginal erosion and less likely to infect or erode into the urethra. In any event, urogenital atrophy should be treated with local estrogen preoperatively to prevent some of these complications.

Technique

Conventionally, suburethral slings were placed via a combined vaginal and abdominal approach into the retropubic space of Retzius. Alternatively, the procedure could be performed abdominally by creating a suburethral tunnel via pelvic incisions, but this is the most difficult route.

Most recently, technological advances have simplified the vaginal approach, which utilizes minimal suburethral dissection and small suprapubic incisions. This technique is subdivided into “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches. In the bottom-up TVT, the sling is inserted into a vaginal incision and threaded up through the patient’s pelvis, exiting from a small suprapubic incision. The topdown SPARC entails a reverse approach, starting from a suprapubic incision and exiting from a vaginal incision. New modifications allow for an abdominal TVT approach, as well, which we describe in detail in a later section.

Surgeons who are familiar with traditional needle suspensions may be more comfortable with the top-down approach. The need for concomitant surgery (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair) not only determines the type of incontinence procedure, but also dictates the approach.

Preparing the patient. Place the patient under regional or local anesthesia with sedation so that an intraoperative cough stress test can be performed. Then administer an intravenous dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Insert a 16 to 18 French Foley catheter into the urethra. Mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides of the patient. Inject approximately 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked areas. We typically use 60 cc of 0.25% bupivicaine with epinephrine, diluted 1:1 with 60 cc of normal saline. After administering the local anesthetic suprapubically, inject a similar solution into the anterior vaginal wall suburethrally in the midline and laterally toward the retropubic tunnels.

Making the incisions. Both the TVT and SPARC techniques utilize the same type and location of incisions. As such, make a 0.5-cm incision into the abdominal skin on each side of the midline, approximately 1 cm lateral to midline and 1 cm above the pubic symphsis. Next, make a 1.5- to 2-cm vertical incision in the vaginal mucosa, starting 1.5 cm from the urethral meatus (FIGURE 1). Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the pubocervical fascia sub- and para-urethrally on both sides (FIGURE 2). Insert a Foley catheter guide (similar to the Lowsley retractor) into the catheter and deviate it to the ipsilateral side, thereby retracting the bladder neck to the contralateral side. Proceed with the placement of either the TVT or SPARC sling.

Placing the TVT sling. Attach the TVT introducer to the curved needle trocar on 1 end of the polypropylene sling. Insert the trocar with the tape attached into the vaginal incision and push through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone (FIGURES 3 and 4). Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side (FIGURE 5). It is important to not deviate too laterally, medially, or cephalad during trocar insertion to prevent vessel, bladder, or bowel injury. Perform a cystoscopy to rule out cystotomy. Place the second trocar in a similar manner on the opposite side. After both trocars have been pulled through their respective incisions, perform a tension test.

Placing the SPARC/abdominal TVT sling. Guide the abdominal needles through the previously marked suprapubic incision and the patient’s retropubic cavity (keeping the needle behind the pubic bone), to a finger placed in the vaginal incision (FIGURE 6). Snap the abdominal needle guides with the attached polypropylene mesh to the sling connectors (FIGURE 7). Bring the abdominal needles through the suprapubic incisions. Perform a tension test. As with the TVT sling, perform a cystoscopy after each needle placement to rule out cystotomy. Then pass the sling through the tunnel.

Testing for continence. Once the sling is in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test. Adjust sling tension by pulling up on both sling arms until only a few drops of leakage are noted. It is important not to secure the sling too tightly as this may lead to urinary retention, detrusor instability, or urethral erosion. We prefer placing a hemostat between the sling tape and the urethra to avoid over tightening.

Suspending the sling arms. Remove the plastic sheaths after tension adjustment and cut the sling flush with the skin (FIGURE 8). Compared to the conventional bone-anchored slings, the newer tension-free sling devices are not anchored but instead suspended through the retropubic space. At first, the sling is held in place by friction from the opposing tissues. Over time, collagen formation fixes the mesh more strongly within the suburethral and paravaginal tissues.

Finally, close the suprapubic and vaginal incisions with absorbable sutures.

Placing autologous or allogenic slings. Fashion the graft, typically 2 cm wide and 10 to 12 cm long, with permanent sutures at the edges. Make a 1-cm incision into the suprapubic rectus fascia. Use either a Stamey-type needle trocar or uterine packing forceps and guide the instrument “top down” from the retropubic incision to the vaginal tunnel. The tunnel is made directly into the retropubic space from the vaginal incision. Bring the sling arms up on each side. Attach the arms to the rectus fascia and tie them down once cystoscopy and the tension test are complete.

The sling also can be performed with bone anchors placed through the vaginal incision into the pubic bone. Placement requires vaginal dissection into the retropubic space with no suprapubic incision. Once anchored, the sutures are then passed through the chosen graft materials and tied down. Bear in mind that anchoring into the periosteum of the pubic bone may cause severe osteomyelitis or osteitis pubis, though the actual incidence is unknown.7

FIGURE 1 Surgical steps for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT)

Place a Sims speculum into the vagina and make a vertical incision 1.5 cm from the external urethra meatus.

FIGURE 2

Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the underlying fascia bilaterally. Insert a Foley catheter with guide.

FIGURE 3

Place TVT trocars through the vaginal incision. Place abdominal guides suprapubically and attach them to the TVT trocar tip.

FIGURE 4

Push the tape through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone.

FIGURE 5

Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side.

FIGURE 6 Surgical steps for SPARC

Guide the needle down the posterior side of the pubic bone, keeping the needle tip in contact with the pubic bone.

FIGURE 7

Snap the needle guide and sling onto the sling connectors and pull through the suprapubic incision.

FIGURE 8

Perform a tension test. Remove the plastic sheaths and cut the sling flush with the skin.

Complications

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications include bladder perforation, vaginal or retropubic bleeding, wound or urinary tract infection (UTI), and short-term urinary retention. Possible long-term problems include urethral or vaginal erosion, mesh infection, prolonged voiding dysfunction, fistula formation, or de novo urge incontinence (TABLE 2).

Specifically, the TVT sling, which has been placed in more than 50,000 women in the U.S. and 200,000 worldwide, carries the potential for significant vascular injury and bowel perforation. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported 4 deaths (2 from unrecognized bowel injuries, 1 from retropubic bleeding in a patient with a bleeding disorder, and 1 from a heart attack more than 1 week after an incontinence repair procedure complicated by a vascular injury); 168 device malfunctions (mostly tape or sheath detachment from the trocar); and 128 other injuries, including bowel perforations and major vascular injuries to the obturator, external iliac, femoral, or inferior epigastrics (TABLE 3).8 In a review of 1,455 TVT sling cases at 38 hospitals, Kuuva and Nilsson9 found bladder perforation in 3.8% of the patients and retropubic hematoma in 1.9%, along with 1 case of vesicovaginal fistula, 1 obturator nerve injury, and 1 epigastric vessel injury.

According to the FDA, there have been 2 complications reported with the SPARC sling system. Both involved vaginal erosion subsequently repaired by oversewing the vaginal mucosa. One of these complications occurred in a woman undergoing her fourth vaginal procedure who was therefore deemed to have “poor tissue.”8

TABLE 2

Suburethral sling complications1

| COMPLICATION | 1,715 AUTOLOGOUS | 1,515 SYNTHETIC |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal erosion | 1 (.0001%) | 10 (.007%) |

| Urethral erosion | 5 (.003%) | 27 (.02%) |

| Fistula | 6 (.003%) | 4 (.002%) |

| Wound sinus | 3 (.002%) | 11 (.007%) |

| Wound infection | 11 (.006%) | 15 (.009%) |

| Seroma | 6 (.003%) | 1 (.0007%) |

TABLE 3

TVT complications in 200,000 procedures worldwide

| COMPLICATION | U.S. | WORLD | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular injury | 3 | 25 | 28 |

| Vaginal mesh exposure | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Urethral erosion | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Bowel perforation | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Nerve injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Outcomes studies

Unfortunately, most of the published clinical studies on the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence suffer from inadequate follow-up and sample size, unclear patient selection criteria, and poor postoperative documentation, especially with respect to quality of life. However, multiple studies to assess the effectiveness and safety of TVT slings have been published. The following is an outline of these preliminary yet important findings.

In 2002, the Cochrane Database evaluated 7 randomized and quasi-randomized trials of suburethral slings for the treatment of urinary incontinence.10 Of 682 women evaluated, 457 had some type of suburethral sling procedure. Four trials compared slings to retropubic urethropexies, 1 compared slings to Stamey needle suspensions, and 2 compared the use of different sling materials. The results indicated that the data were insufficient to suggest that slings were more effective than other incontinence procedures or that slings were associated with fewer postoperative complications. While TVT slings did provide similar cure rates as open retropubic urethropexy, research is still lacking with respect to other types of slings. More studies comparing TVT slings to traditional pubovaginal slings also are needed before the 2 can be deemed equivalent.

In Sweden and Finland, where the TVT procedure was developed,11 85 patients who had undergone the procedure were evaluated at 48 to 70 months. Of those, 84.7% were completely cured of stress incontinence, 10.6% had significantly improved symptoms, and 4.7% were regarded as failures.

A recent well-designed, multicenter, randomized, prospective trial in the U.K. and Ireland compared 146 open Burch colposuspensions to 170 TVTs. Similar cure rates (57% and 66%, respectively) were reported.12 Although these rates are low compared to the Nordic nonrandomized TVT studies mentioned, the U.K./Ireland outcome criteria were particularly stringent and included a negative cystometrogram for stress incontinence and negative pad test. These differences in reported success rates highlight the importance of clearly defining objective outcomes criteria from randomized trials.

Nonetheless, the U.K./Ireland study showed that TVT is less invasive than the Burch procedure and is associated with shorter recovery periods and greater cost savings. Follow-up on complications (bladder perforation and hematoma in TVTs and incisional hernia formation in Burch colposuspensions) will be the most crucial aspect of this study.13

Clearly, the question of whether a Burch retropubic urethropexy or a suburethral sling procedure is better for SUI needs to be further investigated. Weber and Walters sought to answer this question by developing a decision analytical model (without the aid of randomized, controlled trials) and discovered similar cure rates.14 However, there were higher rates of urinary retention and detrusor instability associated with the traditional pubovaginal sling. But, most importantly, sensitivity analyses proved that if the rate of permanent urinary retention after a sling procedure was less than 9%—as in most sling series—the overall effectiveness of slings was higher than that of the Burch.

Conclusion

The suburethral sling procedure has undergone many modifications since its first description nearly a century ago. As such, Ob/Gyns need to familiarize themselves with the current options. Typically, we perform up to 6 suburethral sling procedures per month. Of those, 50% are referrals from failed incontinence procedures. Recently, we have made the switch from using autologous slings to tension-free type slings due to ease and good outcomes. While more data from randomized, prospective, multicenter trials are needed to determine the best approach for individual patients, surgeons should become comfortable with the technique that works best for them.

The authors report no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

- Suburethral sling procedures are effective in treating patients with urethral hypermobility, intrinsic sphincter deficiency, low-pressure urethras, and increased intra-abdominal pressure.

- Autologous slings may be a better choice in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs.

- For both the tension-free vaginal tape and SPARC slings, mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides and inject 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked regions.

- Once the trocars are in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test to confirm continence.

When the suburethral sling was first described in 1907 by von Giordano, it entailed placing autologous tissue underneath the bladder neck and suspending it superiorly. Complications including urethral erosion, infection, bleeding, and fistula formation led many surgeons to use it sparingly.

Fast forward to the 21st century: Synthetic materials and new techniques were introduced, simplifying the sling procedures and raising the long-term success rates to 84%.1 As a result, slings now stand at the forefront of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) treatment. Among advances are the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) sling (Gynecare, a division of Ethicon Inc., Somerville, NJ) and the SPARC sling (American Medical Systems, Inc., Minnetonka, Minn). The former, approved in the U.S. in 1998, calls for another look due to of the recent publication of a Cochrane review of outcomes studies, while the latter, approved by the FDA in August 2001, is the newest technique deserving examination. Clearly, with 83,010 incontinence procedures performed in the U.S. in 1999,2 a detailed look at the suburethral sling is warranted. Here, we review materials, indications, techniques, complications, and outcomes.

Materials

The choice of material—either organic or synthetic—depends on several factors: availability, cost, patient and surgeon preference, and clinical variables. (TABLE 1) outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each material type. Organic slings include autologous tissues (rectus fascia and fascia lata graft), and allografts or xenografts (cadaveric fascia lata graft, human dermal graft, or porcine small intestine and dermal graft). Synthetic slings are made of polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, and polypropylene.

While sling procedures utilizing organic materials do have their benefits, synthetic slings, particularly the polypropylene mesh used in TVT and SPARC, have proven to be a stable material unlikely to deteriorate with time. Further, increased collagen metabolism around this synthetic sling promotes an ingrowth of tissue through the mesh.

TABLE 1

Slings: advantages and disadvantages of various materials

| SLING MATERIAL | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous tissues (rectus fascia, fascia lata, or vaginal wall) |

|

|

| Allografts (cadaveric fascia lata or dermis) |

|

|

| Xenografts (porcine dermis or small intestine) | ||

| Synthetic mesh (polyethylene terephthalate, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, or polypropylene) |

|

|

Indications

Suburethral sling procedures are typically used for the treatment of genuine stress urinary incontinence (GSUI), in which the urethra becomes either hypermobile and unstable or its intrinsic sphincter becomes incompetent. In fact, slings are technically easier to place in patients with anatomic urethrovesical junction hypermobility compared to those with fixed urethras. Several authors also have suggested the sling’s advantage in patients with low-pressure urethras.3

Use urodynamic criteria to diagnose intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD), which is defined as a Valsalva leak point pressure of less than 60 cm water or maximal urethral closure pressure of less than 20 cm water. (Bear in mind, however, that these cut-off criteria are controversial.4,5)

Also, consider slings in patients with recurrent GSUI, inherited collagen deficiency, and increased abdominal pressure (e.g., women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, or high-impact physical activity). The sling also can be used as an adjunct to other transvaginal surgeries (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair).

Autologous slings may be a better choice than synthetic slings in cases of severe urogenital atrophy, previous radiation, or extensive scarring from previous repairs. In these instances, the patient may be at-risk for postoperative vaginal necrosis or erosion.6 Due to their biocompatibility, autologous slings are more likely to heal over a vaginal erosion and less likely to infect or erode into the urethra. In any event, urogenital atrophy should be treated with local estrogen preoperatively to prevent some of these complications.

Technique

Conventionally, suburethral slings were placed via a combined vaginal and abdominal approach into the retropubic space of Retzius. Alternatively, the procedure could be performed abdominally by creating a suburethral tunnel via pelvic incisions, but this is the most difficult route.

Most recently, technological advances have simplified the vaginal approach, which utilizes minimal suburethral dissection and small suprapubic incisions. This technique is subdivided into “bottom-up” and “top-down” approaches. In the bottom-up TVT, the sling is inserted into a vaginal incision and threaded up through the patient’s pelvis, exiting from a small suprapubic incision. The topdown SPARC entails a reverse approach, starting from a suprapubic incision and exiting from a vaginal incision. New modifications allow for an abdominal TVT approach, as well, which we describe in detail in a later section.

Surgeons who are familiar with traditional needle suspensions may be more comfortable with the top-down approach. The need for concomitant surgery (e.g., hysterectomy or prolapse repair) not only determines the type of incontinence procedure, but also dictates the approach.

Preparing the patient. Place the patient under regional or local anesthesia with sedation so that an intraoperative cough stress test can be performed. Then administer an intravenous dose of a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Insert a 16 to 18 French Foley catheter into the urethra. Mark the suprapubic region 1 cm above and 1 cm lateral to the pubic symphsis on the left and right sides of the patient. Inject approximately 20 cc of a 1:1 mixture of local anesthetic and normal saline into the marked areas. We typically use 60 cc of 0.25% bupivicaine with epinephrine, diluted 1:1 with 60 cc of normal saline. After administering the local anesthetic suprapubically, inject a similar solution into the anterior vaginal wall suburethrally in the midline and laterally toward the retropubic tunnels.

Making the incisions. Both the TVT and SPARC techniques utilize the same type and location of incisions. As such, make a 0.5-cm incision into the abdominal skin on each side of the midline, approximately 1 cm lateral to midline and 1 cm above the pubic symphsis. Next, make a 1.5- to 2-cm vertical incision in the vaginal mucosa, starting 1.5 cm from the urethral meatus (FIGURE 1). Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the pubocervical fascia sub- and para-urethrally on both sides (FIGURE 2). Insert a Foley catheter guide (similar to the Lowsley retractor) into the catheter and deviate it to the ipsilateral side, thereby retracting the bladder neck to the contralateral side. Proceed with the placement of either the TVT or SPARC sling.

Placing the TVT sling. Attach the TVT introducer to the curved needle trocar on 1 end of the polypropylene sling. Insert the trocar with the tape attached into the vaginal incision and push through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone (FIGURES 3 and 4). Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side (FIGURE 5). It is important to not deviate too laterally, medially, or cephalad during trocar insertion to prevent vessel, bladder, or bowel injury. Perform a cystoscopy to rule out cystotomy. Place the second trocar in a similar manner on the opposite side. After both trocars have been pulled through their respective incisions, perform a tension test.

Placing the SPARC/abdominal TVT sling. Guide the abdominal needles through the previously marked suprapubic incision and the patient’s retropubic cavity (keeping the needle behind the pubic bone), to a finger placed in the vaginal incision (FIGURE 6). Snap the abdominal needle guides with the attached polypropylene mesh to the sling connectors (FIGURE 7). Bring the abdominal needles through the suprapubic incisions. Perform a tension test. As with the TVT sling, perform a cystoscopy after each needle placement to rule out cystotomy. Then pass the sling through the tunnel.

Testing for continence. Once the sling is in place, fill the bladder with 250 cc of water and perform a cough stress test. Adjust sling tension by pulling up on both sling arms until only a few drops of leakage are noted. It is important not to secure the sling too tightly as this may lead to urinary retention, detrusor instability, or urethral erosion. We prefer placing a hemostat between the sling tape and the urethra to avoid over tightening.

Suspending the sling arms. Remove the plastic sheaths after tension adjustment and cut the sling flush with the skin (FIGURE 8). Compared to the conventional bone-anchored slings, the newer tension-free sling devices are not anchored but instead suspended through the retropubic space. At first, the sling is held in place by friction from the opposing tissues. Over time, collagen formation fixes the mesh more strongly within the suburethral and paravaginal tissues.

Finally, close the suprapubic and vaginal incisions with absorbable sutures.

Placing autologous or allogenic slings. Fashion the graft, typically 2 cm wide and 10 to 12 cm long, with permanent sutures at the edges. Make a 1-cm incision into the suprapubic rectus fascia. Use either a Stamey-type needle trocar or uterine packing forceps and guide the instrument “top down” from the retropubic incision to the vaginal tunnel. The tunnel is made directly into the retropubic space from the vaginal incision. Bring the sling arms up on each side. Attach the arms to the rectus fascia and tie them down once cystoscopy and the tension test are complete.

The sling also can be performed with bone anchors placed through the vaginal incision into the pubic bone. Placement requires vaginal dissection into the retropubic space with no suprapubic incision. Once anchored, the sutures are then passed through the chosen graft materials and tied down. Bear in mind that anchoring into the periosteum of the pubic bone may cause severe osteomyelitis or osteitis pubis, though the actual incidence is unknown.7

FIGURE 1 Surgical steps for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT)

Place a Sims speculum into the vagina and make a vertical incision 1.5 cm from the external urethra meatus.

FIGURE 2

Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the underlying fascia bilaterally. Insert a Foley catheter with guide.

FIGURE 3

Place TVT trocars through the vaginal incision. Place abdominal guides suprapubically and attach them to the TVT trocar tip.

FIGURE 4

Push the tape through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone.

FIGURE 5

Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side.

FIGURE 6 Surgical steps for SPARC

Guide the needle down the posterior side of the pubic bone, keeping the needle tip in contact with the pubic bone.

FIGURE 7

Snap the needle guide and sling onto the sling connectors and pull through the suprapubic incision.

FIGURE 8

Perform a tension test. Remove the plastic sheaths and cut the sling flush with the skin.

Complications

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications include bladder perforation, vaginal or retropubic bleeding, wound or urinary tract infection (UTI), and short-term urinary retention. Possible long-term problems include urethral or vaginal erosion, mesh infection, prolonged voiding dysfunction, fistula formation, or de novo urge incontinence (TABLE 2).

Specifically, the TVT sling, which has been placed in more than 50,000 women in the U.S. and 200,000 worldwide, carries the potential for significant vascular injury and bowel perforation. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported 4 deaths (2 from unrecognized bowel injuries, 1 from retropubic bleeding in a patient with a bleeding disorder, and 1 from a heart attack more than 1 week after an incontinence repair procedure complicated by a vascular injury); 168 device malfunctions (mostly tape or sheath detachment from the trocar); and 128 other injuries, including bowel perforations and major vascular injuries to the obturator, external iliac, femoral, or inferior epigastrics (TABLE 3).8 In a review of 1,455 TVT sling cases at 38 hospitals, Kuuva and Nilsson9 found bladder perforation in 3.8% of the patients and retropubic hematoma in 1.9%, along with 1 case of vesicovaginal fistula, 1 obturator nerve injury, and 1 epigastric vessel injury.

According to the FDA, there have been 2 complications reported with the SPARC sling system. Both involved vaginal erosion subsequently repaired by oversewing the vaginal mucosa. One of these complications occurred in a woman undergoing her fourth vaginal procedure who was therefore deemed to have “poor tissue.”8

TABLE 2

Suburethral sling complications1

| COMPLICATION | 1,715 AUTOLOGOUS | 1,515 SYNTHETIC |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal erosion | 1 (.0001%) | 10 (.007%) |

| Urethral erosion | 5 (.003%) | 27 (.02%) |

| Fistula | 6 (.003%) | 4 (.002%) |

| Wound sinus | 3 (.002%) | 11 (.007%) |

| Wound infection | 11 (.006%) | 15 (.009%) |

| Seroma | 6 (.003%) | 1 (.0007%) |

TABLE 3

TVT complications in 200,000 procedures worldwide

| COMPLICATION | U.S. | WORLD | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular injury | 3 | 25 | 28 |

| Vaginal mesh exposure | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Urethral erosion | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Bowel perforation | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Nerve injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Outcomes studies

Unfortunately, most of the published clinical studies on the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence suffer from inadequate follow-up and sample size, unclear patient selection criteria, and poor postoperative documentation, especially with respect to quality of life. However, multiple studies to assess the effectiveness and safety of TVT slings have been published. The following is an outline of these preliminary yet important findings.

In 2002, the Cochrane Database evaluated 7 randomized and quasi-randomized trials of suburethral slings for the treatment of urinary incontinence.10 Of 682 women evaluated, 457 had some type of suburethral sling procedure. Four trials compared slings to retropubic urethropexies, 1 compared slings to Stamey needle suspensions, and 2 compared the use of different sling materials. The results indicated that the data were insufficient to suggest that slings were more effective than other incontinence procedures or that slings were associated with fewer postoperative complications. While TVT slings did provide similar cure rates as open retropubic urethropexy, research is still lacking with respect to other types of slings. More studies comparing TVT slings to traditional pubovaginal slings also are needed before the 2 can be deemed equivalent.

In Sweden and Finland, where the TVT procedure was developed,11 85 patients who had undergone the procedure were evaluated at 48 to 70 months. Of those, 84.7% were completely cured of stress incontinence, 10.6% had significantly improved symptoms, and 4.7% were regarded as failures.

A recent well-designed, multicenter, randomized, prospective trial in the U.K. and Ireland compared 146 open Burch colposuspensions to 170 TVTs. Similar cure rates (57% and 66%, respectively) were reported.12 Although these rates are low compared to the Nordic nonrandomized TVT studies mentioned, the U.K./Ireland outcome criteria were particularly stringent and included a negative cystometrogram for stress incontinence and negative pad test. These differences in reported success rates highlight the importance of clearly defining objective outcomes criteria from randomized trials.

Nonetheless, the U.K./Ireland study showed that TVT is less invasive than the Burch procedure and is associated with shorter recovery periods and greater cost savings. Follow-up on complications (bladder perforation and hematoma in TVTs and incisional hernia formation in Burch colposuspensions) will be the most crucial aspect of this study.13

Clearly, the question of whether a Burch retropubic urethropexy or a suburethral sling procedure is better for SUI needs to be further investigated. Weber and Walters sought to answer this question by developing a decision analytical model (without the aid of randomized, controlled trials) and discovered similar cure rates.14 However, there were higher rates of urinary retention and detrusor instability associated with the traditional pubovaginal sling. But, most importantly, sensitivity analyses proved that if the rate of permanent urinary retention after a sling procedure was less than 9%—as in most sling series—the overall effectiveness of slings was higher than that of the Burch.

Conclusion

The suburethral sling procedure has undergone many modifications since its first description nearly a century ago. As such, Ob/Gyns need to familiarize themselves with the current options. Typically, we perform up to 6 suburethral sling procedures per month. Of those, 50% are referrals from failed incontinence procedures. Recently, we have made the switch from using autologous slings to tension-free type slings due to ease and good outcomes. While more data from randomized, prospective, multicenter trials are needed to determine the best approach for individual patients, surgeons should become comfortable with the technique that works best for them.

The authors report no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, et al. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 1997;875-880.

2. Nihira MA, Schaffer JI. Surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence in 1999. Presented at: 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; March 6, 2002; Dallas, Texas.

3. Kobashi KC, Leach GE. Stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:285-290.

4. Bowen LW, Sand PK, Ostergard DR, Franti CE. Unsuccessful Burch retropubic urethropexy: a case-controlled urodynamic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:452-458.

5. Bump RC, Coates KW, Cundiff GW, Harris RL, Weidner AC. Diagnosing intrinsic sphincteric deficiency: Comparing urethral closure pressure, urethral axis, and Valsalva leak point pressures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:303-310.

6. Nichols DH, Randal CL. Operations for urinary stress incontinence. In: Vaginal Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996;402-415.

7. Rackley RR, Abdelmalak JB, Madjar S, Yanilmaz A, Appell RA, Tchetgen MB. Bone anchor infections in female pelvic reconstructive procedures: a literature review of series and case reports. J Urol. 2001;165:1975-1978.

8. Food and Drug Administration manufacturer and user facility device experience database. Available at: www.fda.gov/cdrh/maude.html. Accessed November 12, 2002.

9. Kuuva N, Nilsson CG. A nationwide analysis of complications associated with the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:394.-

10. Bezerra CA, Bruschini H. Suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001754.-

11. Nilsson CG, Kuuva N, Falconer C, Rezapour M, Ulmsten U. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure (TVT) for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(suppl 2):S5-S8.

12. Ward KL, Hilton P, Browning J. A randomized trial of colposuspension and tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for primary genuine stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:386.-

13. Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325:67.-

14. Weber A, Walters M. Burch procedure compared with sling for stress urinary incontinence: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:867-873.

1. Leach GE, Dmochowski RR, Appell RA, et al. Female Stress Urinary Incontinence Clinical Guidelines Panel summary report on surgical management of female stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 1997;875-880.

2. Nihira MA, Schaffer JI. Surgical procedures for stress urinary incontinence in 1999. Presented at: 28th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons; March 6, 2002; Dallas, Texas.

3. Kobashi KC, Leach GE. Stress urinary incontinence. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:285-290.

4. Bowen LW, Sand PK, Ostergard DR, Franti CE. Unsuccessful Burch retropubic urethropexy: a case-controlled urodynamic study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:452-458.

5. Bump RC, Coates KW, Cundiff GW, Harris RL, Weidner AC. Diagnosing intrinsic sphincteric deficiency: Comparing urethral closure pressure, urethral axis, and Valsalva leak point pressures. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:303-310.

6. Nichols DH, Randal CL. Operations for urinary stress incontinence. In: Vaginal Surgery. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996;402-415.

7. Rackley RR, Abdelmalak JB, Madjar S, Yanilmaz A, Appell RA, Tchetgen MB. Bone anchor infections in female pelvic reconstructive procedures: a literature review of series and case reports. J Urol. 2001;165:1975-1978.

8. Food and Drug Administration manufacturer and user facility device experience database. Available at: www.fda.gov/cdrh/maude.html. Accessed November 12, 2002.

9. Kuuva N, Nilsson CG. A nationwide analysis of complications associated with the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:394.-

10. Bezerra CA, Bruschini H. Suburethral sling operations for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):CD001754.-

11. Nilsson CG, Kuuva N, Falconer C, Rezapour M, Ulmsten U. Long-term results of the tension-free vaginal tape procedure (TVT) for surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(suppl 2):S5-S8.

12. Ward KL, Hilton P, Browning J. A randomized trial of colposuspension and tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) for primary genuine stress incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:386.-

13. Ward K, Hilton P. Prospective multicenter randomized trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325:67.-

14. Weber A, Walters M. Burch procedure compared with sling for stress urinary incontinence: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:867-873.

Pearls on cesarean

Even with its recent decline in occurrence, cesarean delivery remains the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the United States, accounting for approximately 21.5% of all deliveries. Here, obstetricians from across the country share pearls on various aspects of cesarean birth.

The difficult cesarean. When a difficult cesarean is predicted and the threat of obstetrical hemorrhage is imminent, I recommend that clinicians position the patient in low Allen stirrups, using a drape that provides vaginal access. This allows for proper elevation of the fetal head and better assessment of potential blood loss. Make sure a hysterectomy instrument tray is nearby and an experienced gynecologic scrub nurse is available. These steps should eliminate occult hemorrhage and allow for rapid response to any changes in the patient’s clinical status. —Richard Hill, MD, Kansas City, Mo

Cranial dystocia. A cesarean is often required when labor-arrest disorders occur. Cranial dystocia is sometimes found in these cases, making for a difficult delivery. When manual extraction of the fetal head fails, the surgeon typically has an assistant place a hand in the vagina to elevate and disengage the head. In these cases, I instead suggest surgeons remove their delivering hand from the uterine incision, cup the fetal head outside the lower uterine segment and bladder, and then pull upward. This will break the vacuum that spontaneously occurs, liberating the fetal head and allowing for successful cesarean delivery. —Peter Napolitano, MD, Tacoma, Wash

Intact membranes. When a patient with unruptured membranes presents for a cesarean, avoid breaching the amniotic sac sharply or with a clamp. Instead, first approach the uterine muscle sharply through the outer layers, then bluntly dissect the remaining fibers with your fingertip, allowing the amniotic sac to bulge out through the incision. Complete the uterine incision sharply with bandage scissors prior to rupturing the membranes, then open the bulging membranes either bluntly or with an Allis clamp. These steps ensure that the fetus will not experience trauma from sharp surgical objects. —Scott Resnick, MD, Taos, NM

Lowering the cesarean rate. To reduce the number of cesarean deliveries, try inducing labor of the unscarred uterus as follows:

- 8 AM: Insert 50 μg of misoprostol deep in the vagina.

- Noon: If the cervix is dilated, rupture membranes regardless of the Bishop score. Labor will almost invariably ensue within 1 to 2 hours. If the cervix is still closed at this time, insert another dose of misoprostol.

- Noon to 5 PM: Observe for cervical dilation. If this does not occur, augment labor with oxytocin.

Some patients will achieve vaginal delivery by 5 PM, and most will deliver by midnight.

With this technique, selecting patients for induction prior to their due date and before macrosomia or fetal stress develop is key to successfully keeping the cesarean rate low. —Susan Vicente, MD, Kailua, Hawaii

Even with its recent decline in occurrence, cesarean delivery remains the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the United States, accounting for approximately 21.5% of all deliveries. Here, obstetricians from across the country share pearls on various aspects of cesarean birth.

The difficult cesarean. When a difficult cesarean is predicted and the threat of obstetrical hemorrhage is imminent, I recommend that clinicians position the patient in low Allen stirrups, using a drape that provides vaginal access. This allows for proper elevation of the fetal head and better assessment of potential blood loss. Make sure a hysterectomy instrument tray is nearby and an experienced gynecologic scrub nurse is available. These steps should eliminate occult hemorrhage and allow for rapid response to any changes in the patient’s clinical status. —Richard Hill, MD, Kansas City, Mo

Cranial dystocia. A cesarean is often required when labor-arrest disorders occur. Cranial dystocia is sometimes found in these cases, making for a difficult delivery. When manual extraction of the fetal head fails, the surgeon typically has an assistant place a hand in the vagina to elevate and disengage the head. In these cases, I instead suggest surgeons remove their delivering hand from the uterine incision, cup the fetal head outside the lower uterine segment and bladder, and then pull upward. This will break the vacuum that spontaneously occurs, liberating the fetal head and allowing for successful cesarean delivery. —Peter Napolitano, MD, Tacoma, Wash

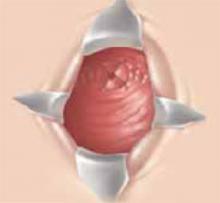

Intact membranes. When a patient with unruptured membranes presents for a cesarean, avoid breaching the amniotic sac sharply or with a clamp. Instead, first approach the uterine muscle sharply through the outer layers, then bluntly dissect the remaining fibers with your fingertip, allowing the amniotic sac to bulge out through the incision. Complete the uterine incision sharply with bandage scissors prior to rupturing the membranes, then open the bulging membranes either bluntly or with an Allis clamp. These steps ensure that the fetus will not experience trauma from sharp surgical objects. —Scott Resnick, MD, Taos, NM

Lowering the cesarean rate. To reduce the number of cesarean deliveries, try inducing labor of the unscarred uterus as follows:

- 8 AM: Insert 50 μg of misoprostol deep in the vagina.

- Noon: If the cervix is dilated, rupture membranes regardless of the Bishop score. Labor will almost invariably ensue within 1 to 2 hours. If the cervix is still closed at this time, insert another dose of misoprostol.

- Noon to 5 PM: Observe for cervical dilation. If this does not occur, augment labor with oxytocin.

Some patients will achieve vaginal delivery by 5 PM, and most will deliver by midnight.

With this technique, selecting patients for induction prior to their due date and before macrosomia or fetal stress develop is key to successfully keeping the cesarean rate low. —Susan Vicente, MD, Kailua, Hawaii

Even with its recent decline in occurrence, cesarean delivery remains the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the United States, accounting for approximately 21.5% of all deliveries. Here, obstetricians from across the country share pearls on various aspects of cesarean birth.

The difficult cesarean. When a difficult cesarean is predicted and the threat of obstetrical hemorrhage is imminent, I recommend that clinicians position the patient in low Allen stirrups, using a drape that provides vaginal access. This allows for proper elevation of the fetal head and better assessment of potential blood loss. Make sure a hysterectomy instrument tray is nearby and an experienced gynecologic scrub nurse is available. These steps should eliminate occult hemorrhage and allow for rapid response to any changes in the patient’s clinical status. —Richard Hill, MD, Kansas City, Mo

Cranial dystocia. A cesarean is often required when labor-arrest disorders occur. Cranial dystocia is sometimes found in these cases, making for a difficult delivery. When manual extraction of the fetal head fails, the surgeon typically has an assistant place a hand in the vagina to elevate and disengage the head. In these cases, I instead suggest surgeons remove their delivering hand from the uterine incision, cup the fetal head outside the lower uterine segment and bladder, and then pull upward. This will break the vacuum that spontaneously occurs, liberating the fetal head and allowing for successful cesarean delivery. —Peter Napolitano, MD, Tacoma, Wash

Intact membranes. When a patient with unruptured membranes presents for a cesarean, avoid breaching the amniotic sac sharply or with a clamp. Instead, first approach the uterine muscle sharply through the outer layers, then bluntly dissect the remaining fibers with your fingertip, allowing the amniotic sac to bulge out through the incision. Complete the uterine incision sharply with bandage scissors prior to rupturing the membranes, then open the bulging membranes either bluntly or with an Allis clamp. These steps ensure that the fetus will not experience trauma from sharp surgical objects. —Scott Resnick, MD, Taos, NM

Lowering the cesarean rate. To reduce the number of cesarean deliveries, try inducing labor of the unscarred uterus as follows:

- 8 AM: Insert 50 μg of misoprostol deep in the vagina.

- Noon: If the cervix is dilated, rupture membranes regardless of the Bishop score. Labor will almost invariably ensue within 1 to 2 hours. If the cervix is still closed at this time, insert another dose of misoprostol.

- Noon to 5 PM: Observe for cervical dilation. If this does not occur, augment labor with oxytocin.

Some patients will achieve vaginal delivery by 5 PM, and most will deliver by midnight.

With this technique, selecting patients for induction prior to their due date and before macrosomia or fetal stress develop is key to successfully keeping the cesarean rate low. —Susan Vicente, MD, Kailua, Hawaii

Excisional biopsy for CIN

- In most cases, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) and cold-knife conization (CKC) result in equivalent success rates and margin status.

- CKC is preferred in cases of adenocarcinoma in situ or squamous microinvasion.

- Conservative follow-up is generally possible in adenocarcinoma in situ and squamous microinvasion when margins are negative.

- Colposcopy, endocervical curettage, and biopsies should be part of the follow-up strategy for patients with positive margins.

When cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) requires treatment, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is the most frequently used modality, although cold-knife conization (CKC) of the cervical transformation zone still is preferred in select cases. Since excisional techniques are used with CKC, margin status is known and clinical decisions may be based on this information.

This article reviews current indications for excisional biopsy and presents evidence to direct management and follow-up of patients with positive and negative margins.

Selecting a technique

Several large randomized and prospective studies have demonstrated that LEEP is similar in efficacy to CKC and may even remove less of the normal cervical stroma.1-3 In general, LEEP is used to excise high-grade and recurrent squamous dysplasia, as it is similar to CKC in its rates of incomplete excision and residual disease.1,4 However, when adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) is present, CKC is preferred for diagnosis and treatment, since it results in a lower incidence of involved margins and a lower recurrence rate.3,5-7

CKC also is preferred when histologic confirmation of the margin status is crucial, such as when invasion with squamous lesions is suspected. This is because thermal artifacts that may result from LEEP will interfere with interpretation, further complicating treatment planning.1,4,8,9 In cases of microinvasion, the ability to confirm margins makes conservative treatment possible; if the depth of invasion cannot be determined from the specimen, radical surgery may be necessary.

In the hands of an experienced clinician, however, thermal artifact from the LEEP technique generally is not a significant problem. Series reporting high rates of uninterpretable margins have been attributed to operator inexperience.10 In general, thermal artifact is reduced by limiting the number of sections taken. In ideal cases, only a single-piece specimen is obtained, similar to that achieved using CKC.8,10,11 Newer loops, such as the cone biopsy excision loop, may decrease the number of sections and further improve margin interpretation.8

I use CKC in cases of suspected squamous invasion and in the evaluation of glandular lesions, but feel that in other cases LEEP is efficacious and quicker.

Identifying residual disease

When both the endocervical margin and endocervical curettage (ECC) are positive for squamous dysplasia at the time of excision, there is an increased risk of residual disease (TABLE 1).12-14 However, it is not clear whether ECC alone is an independent predictor of residual disease. Although 1 study suggests an increased risk of invasive cancer in women over 50 years of age with a positive ECC at the time of conization, other series have failed to demonstrate a difference in treatment failure rates based on ECC.15-17 Thus, the utility of ECC in directing further therapy at the time of excisional biopsy is unclear. I generally do not perform an ECC with LEEP for squamous dysplasia.

In AIS, a positive ECC is a strong predictor of residual disease, while a negative ECC is of limited significance.18 I am more likely to perform an ECC with glandular lesions. If it is negative, close follow-up still is indicated. If it is positive, repeat excision may be necessary.

TABLE 1

Residual disease and margin status: squamous dysplasia

| AUTHOR | PROPORTION WITH RESIDUAL DISEASE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEGATIVE MARGINS | POSITIVE MARGINS | |||

| NUMBER | % | NUMBER | % | |

| SQUAMOUS LESIONS | ||||

| Bertelsen et al, 199923 | 44/485 | 9 | 29/76 | 38.2 |

| Moore et al, 199524 | 170/523 | 32.5 | 37/91 | 40.7 |

| Lopes et al, 199325 | 0/176 | 0 | 11/131 | 8.4 |

| Murdoch et al, 199226 | 7/405 | 1.7 | 22/160 | 13.8 |

| Andersen et al, 199019 | 0/411 | 0 | 6/469 | 1.3 |

| TOTALS | 221/2,000 | 11 | 105/927 | 11.3 |

| SQUAMOUS MICROINVASION | ||||

| Gurgel et al, 199727 | 6/74 | 8.1 | 45/76 | 59.2 |

| Roman et al, 199722 | 1/30 | 3.3 | 7/50 | 14 |

| TOTALS | 7/104 | 6.7 | 52/126 | 41.3 |

Follow-up of squamous lesions

Considerable clinical uncertainty remains over the relative strengths of cytologic, colposcopic, and histologic evaluation for residual or recurrent disease following excisional biopsy. Conservative management includes Papanicolaou smears alone or in combination with ECC and/or colposcopy.

Negative margins. If margins are negative, the success rate of excisional biopsy is high (90%-100%), and careful observation is the preferred follow-up. Repeat cytologic testing will identify the majority of patients with residual high-grade disease. A prospective randomized trial of cytologic surveillance showed that the detection rate was only 1.9% higher for histology.19 Although 1 report suggests that colposcopy can expedite the diagnosis of recurrent dysplasia, it is unclear from this report whether colposcopy identified significant high-grade dysplasia that cytology missed.20

Positive margins. In most series involving CIN with positive margins, treatment success rates do not differ significantly between patients who undergo repeat surgical procedures and those who have close follow-up. However, endocervical margin involvement appears to carry a higher treatment failure rate than ectocervical margin involvement. Data are conflicting on the proper method of conservative follow-up. Some authors propose only frequent cytologic testing, while others recommend that colposcopy be performed.19-21