User login

Guideline recommends combination therapy for smoking cessation in cancer patients

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has published a new guideline on smoking cessation for cancer patients that recommends combining pharmacologic therapy with counseling as the most effective approach, along with rigorous review and close follow-ups to prevent relapses.

“Although the medical community recognizes the importance of smoking cessation, supporting patients in ceasing to smoke is generally not done well. Our hope is that by addressing smoking cessation in a cancer patient population, we can make it easier for oncologists to effectively support their patients in achieving their smoking cessation goals,” Dr. Peter Shields, deputy director of the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, said in a written statement. Of the estimated 590,000 cancer deaths in 2015, about 170,000, or nearly 30%, will be caused by tobacco smoking. Quitting tobacco improves cancer treatment effectiveness and reduces cancer recurrence, according to the NCCN.

Read the full statement on the NCCN website.

Statins for all eligible under new guidelines could save lives

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

BALTIMORE – If all Americans eligible for statins under new American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines actually took them, thousands of deaths per year from cardiovascular disease might be prevented but at a cost of increased incidence of diabetes and myopathy.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines expand criteria for the use of statins for primary prevention of CVD to more Americans (Circulation 2015;131:A05). Compliance with those guidelines would save 7,930 lives per year that would have been lost to CVD, according to Quanhe Yang, Ph.D., of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division for Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention, and colleagues from the CDC and Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Yang presented the findings at the American Heart Association Epidemiology and Prevention, Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health 2015 Scientific Sessions.

Statins are now indicated for primary prevention of CVD for anyone with an LDL cholesterol level greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL, for individuals aged 40-75 years with diabetes, and for those aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol greater than or equal to 70 mg/dL but less than 190 mg/dL who have at least a 7.5% estimated 10-year risk of developing atherosclerotic CVD. This means that an additional 24.2 million Americans are now eligible for statins but are not taking one, according to Dr. Yang and coinvestigators. However, “no study has assessed the potential impact of statin therapy under the new guidelines,” said Dr. Yang.

In order to obtain treatment group-specific atherosclerotic CVD, investigators first estimated hazard ratios for each treatment group by sex from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III)–linked Mortality files. These hazard ratios were then applied to data from NHANES 2005-2010, the 2010 Multiple Cause of Death file, and the 2010 U.S. census to obtain age/race/sex-specific atherosclerotic CVD for each treatment group.

Applying the per-group hazard ratios, Dr. Yang and colleagues calculated that an annual 7,930 atherosclerotic CVD deaths would be prevented with full statin compliance, a reduction of 12.6%. However, modeling predicted an additional 16,400 additional cases of diabetes caused by statin use, he cautioned. More cases of myopathy would also occur, though the estimated number depends on whether the rate is derived from randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) or from population-based reports of myopathy. If the RCT data are used, just 1,510 excess cases of myopathy would be seen, in contrast to the 36,100 cases predicted by population-based data.

The study could model deaths caused by CVD only and not the reduction in disease burden of CVD that would result if all of the additional 24.2 million Americans took a statin, Dr Yang noted. Other limitations of the study included the lack of agreement in incidence of myopathy between RCTs and population-based studies, as well as the likelihood that the risk of diabetes increases with age and higher statin dose – effects not accounted for in the study.

Questioning after the talk focused on sex-specific differences in statin takers. For example, statin-associated diabetes is more common in women than men, another effect not accounted for in the study’s modeling, noted an audience member. Additionally, given that women have been underrepresented in clinical trials in general and in those for CVD in particular, some modeling assumptions in the present study may also lack full generalizability to women at risk for CVD.

AT AHA EPI/LIFESTYLE 2015MEETING

Key clinical point: New statin guidelines, if followed, could save lives but increase cases of myopathy and diabetes.

Major finding: Up to 12.6% of current deaths from CVD could be prevented if all guideline-eligible Americans took statins; saving of these lives would come at the cost of excess cases of diabetes and myopathy.

Data source: Analysis of U.S. census data and data from the NHANES study, together with meta-analysis of RCTs, used to model outcomes for 100% guideline-eligible statin use.

Disclosures: No authors reported financial disclosures.

Latest valvular disease guidelines bring big changes

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease break new ground in numerous ways, Dr. Rick A. Nishimura said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“We needed to do things differently. These guidelines were created in a different format from prior valvular heart disease guidelines. We wanted these guidelines to promote access to concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care,” explained Dr. Nishimura, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and cochair of the guidelines writing committee.

These guidelines – the first major revision in 8 years – introduce a new taxonomy and the first staging system for valvular heart disease. The guidelines also lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients, recommending surgical or catheter-based treatment at an earlier point in the disease process than ever before. And the guidelines introduce the concept of heart valve centers of excellence, offering a strong recommendation that patients be referred to those centers for procedures to be performed in the asymptomatic phase of disease (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2438-88).

These valvular heart disease guidelines place greater emphasis than before on the quality of the scientific evidence underlying recommendations. Since valvular heart disease is a field with a paucity of randomized trials, that meant cutting back.

“Our goal was, if there’s little evidence, don’t write a recommendation. So the number of recommendations went down, but at least the ones that were made were based on evidence,” the cardiologist noted.

Indeed, in the 2006 guidelines, more than 70% of the recommendations were Level of Evidence C and based solely upon expert opinion; in the new guidelines, that’s true for less than 50%. And the proportion of recommendations that are Level of Evidence B increased from 30% to 45%.

The 2014 update was prompted by huge changes in the field of valvular heart disease since 2006. For example, better data became available on the natural history of valvular heart disease. The old concept was not to operate on the asymptomatic patient with severe aortic stenosis and normal left ventricular function, but more recent natural history studies have shown that, left untreated, 72% of such patients will die or develop symptoms within 5 years.

So there has been a push to intervene earlier. Fortunately, that became doable, as recent years also brought improved noninvasive imaging, new catheter-based interventions, and refined surgical methods, enabling operators to safely lower the threshold for intervention in asymptomatic patients while at the same time extending procedural therapies to older, sicker populations.

Dr. Nishimura predicted that cardiologists and surgeons will find the new staging system clinically useful. The four stages, A-D, define the categories “at risk,” “progressive,” “asymptomatic severe,” and “symptomatic severe,” respectively. These categories are particularly helpful in determining how often to schedule patient follow-up and when to time intervention.

The guidelines recommend observation for patients who are Stage A or B and intervention when reasonable in patients who are Stage C2 or D. What bumps a patient with hemodynamically severe yet asymptomatic mitral regurgitation from Stage C1 to C2 is an left ventricular ejection fraction below 60% or a left ventricular end systolic dimension of 40 mm or more. In the setting of asymptomatic aortic stenosis, it’s a peak aortic valve velocity of 4.0 m/sec on Doppler echocardiography plus an LVEF of less than 50%.

The latest guidelines introduced the concept of heart valve centers of excellence in response to evidence of large variability across the country in terms of experience with valve operations. For example, the majority of centers perform fewer than 40 mitral valve repairs per year, and surgeons who perform mitral operations do a median of just five per year. The guideline committee, which included general and interventional cardiologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, and imaging experts, was persuaded that those numbers are not sufficient to achieve optimal results in complex valve operations for asymptomatic patients.

The criteria for qualifying as a heart valve center of excellence, as defined in the guidelines, include having a multidisciplinary heart valve team, high patient volume, high-level surgical experience and expertise in complex valve procedures, and active participation in multicenter data registries and continuous quality improvement processes.

“The most important thing is you have to be very transparent with your data,” according to the cardiologist.

Ultimately, the most far-reaching change introduced in the current valvular heart disease guidelines is the switch from textbook format to what Dr. Nishimura calls structured data knowledge management.

“The AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines are generally recognized as the flagship of U.S. cardiovascular medicine, but they’re like a library of old books. Clinically valuable knowledge is buried within documents that can be 200 pages long. What we need at the point of care is the gist: concise, relevant bytes of information that answer a specific clinical question, synthesized by experts,” Dr. Nishimura said.

The new approach is designed to counter the information overload that plagues contemporary medical practice. Each recommendation in the current valvular heart disease guidelines addresses a specific clinical question via a brief summary statement followed by a short explanatory paragraph, with accompanying references for those who seek additional details. This new format is designed to lead AHA/ACC clinical practice guidelines into the electronic information management future.

“In the future, you’ll go to your iPad or iPhone or whatever, type in search terms such as ‘anticoagulation for mechanical valves during pregnancy,’ and it will take you straight to the relevant knowledge byte. You can then click on ‘more’ and find out more and get to the supporting evidence tables. The knowledge chunks will be stored in a centralized knowledge management system. The nice thing about this is that it will be a living document that can easily be updated, instead of having to wait 8 years for a new version,” Dr. Nishimura explained.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Infectious Diseases Society of America 2014 Practice Guidelines To Diagnose, Manage Skin, Soft Tissue Infections

Background

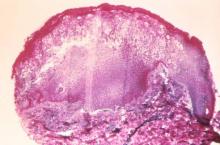

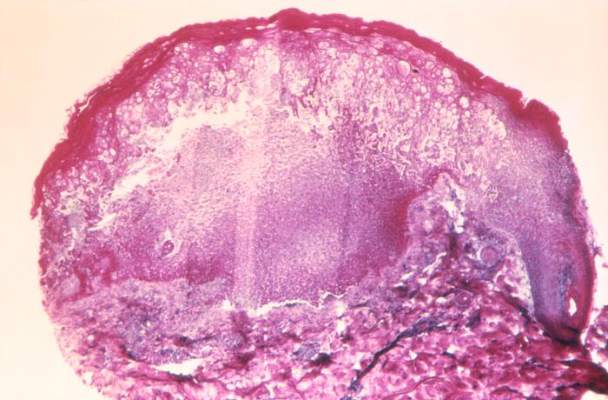

Surveillance studies in the U.S. have shown an increase in the number of hospitalizations for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) by 29% from 2000 to 2004.1 Moreover, recent studies on the inpatient management of SSTIs have shown significant deviation from recommended therapy, with the majority of patients receiving excessively long treatment courses or unnecessarily broad antimicrobial coverage.2,3

With the ever-increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and rising rates of Clostridium difficile colitis, this update provides clinicians with a set of recommendations to apply antibiotic stewardship while effectively managing SSTIs.4

Guideline Update

In June 2014, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published an update to its 2005 guidelines for the treatment of SSTIs.5 For purulent SSTIs (cutaneous abscesses, furuncles, carbuncles, and inflamed epidermoid cysts), incision and drainage is primary therapy. The use of systemic antimicrobial therapy is unnecessary for mild cases, even those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The use of empiric adjunctive antibiotics should be reserved for those with impaired host defenses or signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The recommended antibiotics in such patients have anti-MRSA activity and include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline for moderate infections and vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, telavancin, or ceftaroline for severe infections. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on susceptibilities of the organism cultured from purulent drainage.

Nonpurulent cellulitis without SIRS may be treated on an outpatient basis with an oral antibiotic targeted against streptococci, including penicillin VK, cephalosporins, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin. Cellulitis with SIRS may be treated with an intravenous antibiotic with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) activity, including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

The use of antibiotics with MRSA activity should be reserved for those at highest risk, such as patients with impaired immunity or signs of a deep space infection. Cultures of blood, cutaneous biopsies, or swabs are not routinely recommended; however, prompt surgical consultation is recommended for patients suspected of having a necrotizing infection or gangrene.

The recommended duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis is five days, and therapy should only be extended in those who have not shown clinical improvement. Elevation of the affected area and the use of systemic corticosteroids in nondiabetic adults may lead to a more rapid resolution of cellulitis, although the clinician must ensure that a deeper space infection is not present prior to initiating steroids.

Preventing the recurrence of cellulitis is an integral part of routine patient care and includes the treatment of interdigital toe space fissuring, scaling, and maceration, which may act as a reservoir for streptococci. Likewise, treatment of predisposing conditions such as eczema, venous insufficiency, and lymphedema may reduce the recurrence of infection. In patients who have three to four episodes of cellulitis despite attempts to treat or control predisposing risk factors, the use of prophylactic antibiotics with erythromycin or penicillin may be considered.

For patients with an SSTI during the first episode of febrile neutropenia, hospitalization and empiric therapy with vancomycin and an antipseudomonal beta-lactam are recommended. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on the antimicrobial susceptibilities of isolated organisms.

For patients with SSTIs in the presence of persistent or recurrent febrile neutropenia, empirically adding antifungal therapy is recommended. Such patients should be aggressively evaluated with blood cultures and biopsy with tissue culture of the skin lesions. The recommended duration of therapy is seven to 14 days for most bacterial SSTIs in the immunocompromised patient.

Analysis

The updated SSTI guidelines provide hospitalists with a practical algorithm for the management of SSTIs, focusing on the presence or absence of purulence, systemic signs of infection, and host immune status to guide therapy. Whereas the 2005 guidelines provided clinicians with a list of recommended antibiotics based on spectrum of activity, the updated guidelines provide a short list of empiric antibiotics based on the type and severity of infection.6

The list of recommended antibiotics with MRSA activity has been updated to include ceftaroline and telavancin. Of note, since these guidelines have been published, three new antibiotics with MRSA activity (tedizolid, oritavancin, and dalbavancin) have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of SSTIs, although their specific role in routine clinical practice is not yet determined.

The treatment algorithm for surgical site infections remains largely unchanged, which reinforces the concept that fever in the first 48 hours is unlikely to represent infection unless accompanied by purulent wound drainage with a positive culture. Likewise, the guidelines recommend risk-stratifying patients with fever and a suspected wound infection more than four days after surgery by the presence or absence of systemic infection or evidence of surrounding cellulitis.

A comprehensive guide to the management of specific pathogens or conditions, such as tularemia, cutaneous anthrax, and bite wounds, is largely unchanged, although the update now includes focused summary statements to navigate through these recommendations more easily.

The updated guidelines provide a more robust yet focused set of recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial, fungal, and viral skin infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially those with neutropenia.

HM Takeaways

The 2014 update to the IDSA practice guidelines for SSTIs contains a chart to help clinicians diagnose and manage common skin infections more effectively. The guidelines’ algorithm stratifies the severity of illness according to whether or not the patient has SIRS or is immunocompromised. The authors recommend against the use of antibiotics for mild purulent SSTIs and reserve the use of anti-MRSA therapy mainly for patients with moderate purulent SSTIs, those with severe SSTIs, or those at high risk for MRSA. Likewise, the use of broad spectrum gram-negative coverage is not recommended in most common, uncomplicated SSTIs and should be reserved for special populations, such as those with immune compromise.

The guidelines strongly recommend a short, five-day course of therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis. Longer treatment courses (i.e., 10 days) are unnecessary and do not improve efficacy for those exhibiting clinical improvement by day five.

Drs. Yogo and Saveli work in the division of infectious disease in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

References

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in the US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1516-1518.

- Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sacrone EE, Price CS, Mehler PS, Burman WJ. Skin and soft-tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895-903.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Moore SJ, et al. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a multicenter cohort of patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1241-1250.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2015.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al.

- Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

Background

Surveillance studies in the U.S. have shown an increase in the number of hospitalizations for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) by 29% from 2000 to 2004.1 Moreover, recent studies on the inpatient management of SSTIs have shown significant deviation from recommended therapy, with the majority of patients receiving excessively long treatment courses or unnecessarily broad antimicrobial coverage.2,3

With the ever-increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and rising rates of Clostridium difficile colitis, this update provides clinicians with a set of recommendations to apply antibiotic stewardship while effectively managing SSTIs.4

Guideline Update

In June 2014, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published an update to its 2005 guidelines for the treatment of SSTIs.5 For purulent SSTIs (cutaneous abscesses, furuncles, carbuncles, and inflamed epidermoid cysts), incision and drainage is primary therapy. The use of systemic antimicrobial therapy is unnecessary for mild cases, even those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The use of empiric adjunctive antibiotics should be reserved for those with impaired host defenses or signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The recommended antibiotics in such patients have anti-MRSA activity and include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline for moderate infections and vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, telavancin, or ceftaroline for severe infections. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on susceptibilities of the organism cultured from purulent drainage.

Nonpurulent cellulitis without SIRS may be treated on an outpatient basis with an oral antibiotic targeted against streptococci, including penicillin VK, cephalosporins, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin. Cellulitis with SIRS may be treated with an intravenous antibiotic with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) activity, including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

The use of antibiotics with MRSA activity should be reserved for those at highest risk, such as patients with impaired immunity or signs of a deep space infection. Cultures of blood, cutaneous biopsies, or swabs are not routinely recommended; however, prompt surgical consultation is recommended for patients suspected of having a necrotizing infection or gangrene.

The recommended duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis is five days, and therapy should only be extended in those who have not shown clinical improvement. Elevation of the affected area and the use of systemic corticosteroids in nondiabetic adults may lead to a more rapid resolution of cellulitis, although the clinician must ensure that a deeper space infection is not present prior to initiating steroids.

Preventing the recurrence of cellulitis is an integral part of routine patient care and includes the treatment of interdigital toe space fissuring, scaling, and maceration, which may act as a reservoir for streptococci. Likewise, treatment of predisposing conditions such as eczema, venous insufficiency, and lymphedema may reduce the recurrence of infection. In patients who have three to four episodes of cellulitis despite attempts to treat or control predisposing risk factors, the use of prophylactic antibiotics with erythromycin or penicillin may be considered.

For patients with an SSTI during the first episode of febrile neutropenia, hospitalization and empiric therapy with vancomycin and an antipseudomonal beta-lactam are recommended. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on the antimicrobial susceptibilities of isolated organisms.

For patients with SSTIs in the presence of persistent or recurrent febrile neutropenia, empirically adding antifungal therapy is recommended. Such patients should be aggressively evaluated with blood cultures and biopsy with tissue culture of the skin lesions. The recommended duration of therapy is seven to 14 days for most bacterial SSTIs in the immunocompromised patient.

Analysis

The updated SSTI guidelines provide hospitalists with a practical algorithm for the management of SSTIs, focusing on the presence or absence of purulence, systemic signs of infection, and host immune status to guide therapy. Whereas the 2005 guidelines provided clinicians with a list of recommended antibiotics based on spectrum of activity, the updated guidelines provide a short list of empiric antibiotics based on the type and severity of infection.6

The list of recommended antibiotics with MRSA activity has been updated to include ceftaroline and telavancin. Of note, since these guidelines have been published, three new antibiotics with MRSA activity (tedizolid, oritavancin, and dalbavancin) have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of SSTIs, although their specific role in routine clinical practice is not yet determined.

The treatment algorithm for surgical site infections remains largely unchanged, which reinforces the concept that fever in the first 48 hours is unlikely to represent infection unless accompanied by purulent wound drainage with a positive culture. Likewise, the guidelines recommend risk-stratifying patients with fever and a suspected wound infection more than four days after surgery by the presence or absence of systemic infection or evidence of surrounding cellulitis.

A comprehensive guide to the management of specific pathogens or conditions, such as tularemia, cutaneous anthrax, and bite wounds, is largely unchanged, although the update now includes focused summary statements to navigate through these recommendations more easily.

The updated guidelines provide a more robust yet focused set of recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial, fungal, and viral skin infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially those with neutropenia.

HM Takeaways

The 2014 update to the IDSA practice guidelines for SSTIs contains a chart to help clinicians diagnose and manage common skin infections more effectively. The guidelines’ algorithm stratifies the severity of illness according to whether or not the patient has SIRS or is immunocompromised. The authors recommend against the use of antibiotics for mild purulent SSTIs and reserve the use of anti-MRSA therapy mainly for patients with moderate purulent SSTIs, those with severe SSTIs, or those at high risk for MRSA. Likewise, the use of broad spectrum gram-negative coverage is not recommended in most common, uncomplicated SSTIs and should be reserved for special populations, such as those with immune compromise.

The guidelines strongly recommend a short, five-day course of therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis. Longer treatment courses (i.e., 10 days) are unnecessary and do not improve efficacy for those exhibiting clinical improvement by day five.

Drs. Yogo and Saveli work in the division of infectious disease in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

References

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in the US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1516-1518.

- Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sacrone EE, Price CS, Mehler PS, Burman WJ. Skin and soft-tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895-903.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Moore SJ, et al. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a multicenter cohort of patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1241-1250.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2015.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al.

- Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

Background

Surveillance studies in the U.S. have shown an increase in the number of hospitalizations for skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) by 29% from 2000 to 2004.1 Moreover, recent studies on the inpatient management of SSTIs have shown significant deviation from recommended therapy, with the majority of patients receiving excessively long treatment courses or unnecessarily broad antimicrobial coverage.2,3

With the ever-increasing threat of antibiotic resistance and rising rates of Clostridium difficile colitis, this update provides clinicians with a set of recommendations to apply antibiotic stewardship while effectively managing SSTIs.4

Guideline Update

In June 2014, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) published an update to its 2005 guidelines for the treatment of SSTIs.5 For purulent SSTIs (cutaneous abscesses, furuncles, carbuncles, and inflamed epidermoid cysts), incision and drainage is primary therapy. The use of systemic antimicrobial therapy is unnecessary for mild cases, even those caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The use of empiric adjunctive antibiotics should be reserved for those with impaired host defenses or signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). The recommended antibiotics in such patients have anti-MRSA activity and include trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline for moderate infections and vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, telavancin, or ceftaroline for severe infections. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on susceptibilities of the organism cultured from purulent drainage.

Nonpurulent cellulitis without SIRS may be treated on an outpatient basis with an oral antibiotic targeted against streptococci, including penicillin VK, cephalosporins, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin. Cellulitis with SIRS may be treated with an intravenous antibiotic with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) activity, including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

The use of antibiotics with MRSA activity should be reserved for those at highest risk, such as patients with impaired immunity or signs of a deep space infection. Cultures of blood, cutaneous biopsies, or swabs are not routinely recommended; however, prompt surgical consultation is recommended for patients suspected of having a necrotizing infection or gangrene.

The recommended duration of antimicrobial therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis is five days, and therapy should only be extended in those who have not shown clinical improvement. Elevation of the affected area and the use of systemic corticosteroids in nondiabetic adults may lead to a more rapid resolution of cellulitis, although the clinician must ensure that a deeper space infection is not present prior to initiating steroids.

Preventing the recurrence of cellulitis is an integral part of routine patient care and includes the treatment of interdigital toe space fissuring, scaling, and maceration, which may act as a reservoir for streptococci. Likewise, treatment of predisposing conditions such as eczema, venous insufficiency, and lymphedema may reduce the recurrence of infection. In patients who have three to four episodes of cellulitis despite attempts to treat or control predisposing risk factors, the use of prophylactic antibiotics with erythromycin or penicillin may be considered.

For patients with an SSTI during the first episode of febrile neutropenia, hospitalization and empiric therapy with vancomycin and an antipseudomonal beta-lactam are recommended. Antibiotics should subsequently be adjusted based on the antimicrobial susceptibilities of isolated organisms.

For patients with SSTIs in the presence of persistent or recurrent febrile neutropenia, empirically adding antifungal therapy is recommended. Such patients should be aggressively evaluated with blood cultures and biopsy with tissue culture of the skin lesions. The recommended duration of therapy is seven to 14 days for most bacterial SSTIs in the immunocompromised patient.

Analysis

The updated SSTI guidelines provide hospitalists with a practical algorithm for the management of SSTIs, focusing on the presence or absence of purulence, systemic signs of infection, and host immune status to guide therapy. Whereas the 2005 guidelines provided clinicians with a list of recommended antibiotics based on spectrum of activity, the updated guidelines provide a short list of empiric antibiotics based on the type and severity of infection.6

The list of recommended antibiotics with MRSA activity has been updated to include ceftaroline and telavancin. Of note, since these guidelines have been published, three new antibiotics with MRSA activity (tedizolid, oritavancin, and dalbavancin) have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of SSTIs, although their specific role in routine clinical practice is not yet determined.

The treatment algorithm for surgical site infections remains largely unchanged, which reinforces the concept that fever in the first 48 hours is unlikely to represent infection unless accompanied by purulent wound drainage with a positive culture. Likewise, the guidelines recommend risk-stratifying patients with fever and a suspected wound infection more than four days after surgery by the presence or absence of systemic infection or evidence of surrounding cellulitis.

A comprehensive guide to the management of specific pathogens or conditions, such as tularemia, cutaneous anthrax, and bite wounds, is largely unchanged, although the update now includes focused summary statements to navigate through these recommendations more easily.

The updated guidelines provide a more robust yet focused set of recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial, fungal, and viral skin infections in immunocompromised hosts, especially those with neutropenia.

HM Takeaways

The 2014 update to the IDSA practice guidelines for SSTIs contains a chart to help clinicians diagnose and manage common skin infections more effectively. The guidelines’ algorithm stratifies the severity of illness according to whether or not the patient has SIRS or is immunocompromised. The authors recommend against the use of antibiotics for mild purulent SSTIs and reserve the use of anti-MRSA therapy mainly for patients with moderate purulent SSTIs, those with severe SSTIs, or those at high risk for MRSA. Likewise, the use of broad spectrum gram-negative coverage is not recommended in most common, uncomplicated SSTIs and should be reserved for special populations, such as those with immune compromise.

The guidelines strongly recommend a short, five-day course of therapy for uncomplicated cellulitis. Longer treatment courses (i.e., 10 days) are unnecessary and do not improve efficacy for those exhibiting clinical improvement by day five.

Drs. Yogo and Saveli work in the division of infectious disease in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora.

References

- Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in the US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1516-1518.

- Jenkins TC, Sabel AL, Sacrone EE, Price CS, Mehler PS, Burman WJ. Skin and soft-tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895-903.

- Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, Moore SJ, et al. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a multicenter cohort of patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1241-1250.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2015.

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10-52. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al.

- Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373-1406.

ACP guidelines for preventing, treating pressure ulcers

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

These guidelines emphasize the dire need for good science to guide both prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers. Despite the ubiquity of pressure ulcers and their potential to threaten life and limb, clinical management varies greatly. Most of the research in this field to date has been underpowered and focused on early signs of healing rather than on more definitive outcomes.

Joyce Black, Ph.D., R.N., is at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. Her financial disclosures are available at www.acponline.org. Dr. Black made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the ACP Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1326/M15-0190]).

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

Alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays have little data to support their use for preventing or treating pressure ulcers, the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians has concluded.

Many U.S. acute-care hospitals, home caregivers, and long-term nursing facilities use alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, even though the evidence in favor of using these surfaces is sparse and of poor quality, the guideline writers said.

The devices have not been show to actually reduce pressure ulcers. The harms have been poorly reported but could be significant. “Using these support systems is expensive and adds unnecessary burden on the health care system. Based on a review of the current evidence, lower-cost support surfaces should be the preferred approach to care,” Dr. Amir Qaseem, of the ACP, Philadelphia, and his associates wrote.

The committee performed an extensive review of the literature on pressure ulcers and compiled two Clinical Practice Guidelines – one concerning prevention (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]) and the other concerning treatment (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]) – in part because “a growing industry” has developed in recent years and aggressively pitches a wide array of products for this patient population. The guidelines present the available evidence on the comparative effectiveness of tools and strategies but state repeatedly that evidence regarding pressure ulcers is sparse and of poor quality.

The prevention guideline strongly recommends that clinicians choose advanced static mattresses or advanced static overlays rather than standard hospital mattresses for at-risk patients. Static mattresses and advanced static overlays provide a constant level of inflation or support and evenly distribute body weight. These products are among the few actually shown to reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers. They are also preferable to alternating-air mattresses and overlays, which change the distribution of pressure by inflating or deflating cells within the devices, and to low-air-loss mattresses and overlays, which use flowing air to regulate heat and humidity and adjust pressure.

Evidence is similarly poor or lacking concerning the use of other support surfaces such as heel supports or boots and a variety of wheelchair cushions. Also lacking evidence are other preventive interventions that extend beyond “usual care,” such as different types of repositioning schemes, a variety of leg elevations, various nutritional supplements, and a wide variety of skin care strategies and topical treatments.

The prevention guideline advises patient assessments to identify those at risk of developing pressure ulcers. However, there is not enough evidence to demonstrate that any one of the many risk assessment tools for this purpose is superior to the others, nor that any of these tools is superior to simple clinical judgment. Risk factors for pressure ulcers include older age; black race or Hispanic ethnicity; low body weight; cognitive impairment; physical impairments; and comorbid conditions that may affect soft-tissue integrity and healing, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, diabetes, edema, impaired microcirculation, hypoalbuminemia, and malnutrition, Dr. Qaseem and his associates wrote (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1567]).

The treatment guideline for patients who already have pressure ulcers similarly notes that the lack of evidence for advanced support surfaces such as alternating-air and low-air-loss mattresses and overlays. It similarly recommends advanced static mattresses or overlays for these patients.

The treatment guideline recommends protein or amino acid supplements as well as hydrocolloid or foam dressings to reduce wound size, and electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing. The evidence for these recommendations is “weak” and of low- to moderate-quality, Dr. Qaseem and his associates said (Ann. Intern. Med. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.7326/M14-1568]).

The evidence for the safety and efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy, even though it is often used to treat pressure ulcers in hospitals, is similarly inconclusive. Also lacking good-quality evidence are the use of alternating-air chair cushions, three-dimensional polyester overlays, zinc supplements, L-carnosine supplements, wound dressings other than the ones already discussed, debriding enzymes, topical phenytoin, maggot therapy, biological agents other than platelet-derived growth factor, or hydrotherapy in which wounds are cleaned using a whirlpool or pulsed lavage.

Guidelines updated for postoperative delirium in geriatric patients

The American Geriatrics Society has released its new Clinical Practice Guideline for Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults, which the society hopes will enable health care professionals to improve delirium prevention and treatment through evidence-based measures.

Among the recommendations for treating delirium in geriatric postsurgical patients are nonpharmacologic interventions such as mobility and walking, avoiding physical restraints, and assuring adequate oxygen, fluids, and nutrition; pain management, preferably with nonopioid medications; and avoidance of certain medications such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and cholinesterase inhibitors.

The guidelines are part of a larger package that includes patient resources, evidence tables and journal articles, and other companion public education materials, available on the AGS website.

The American Geriatrics Society has released its new Clinical Practice Guideline for Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults, which the society hopes will enable health care professionals to improve delirium prevention and treatment through evidence-based measures.

Among the recommendations for treating delirium in geriatric postsurgical patients are nonpharmacologic interventions such as mobility and walking, avoiding physical restraints, and assuring adequate oxygen, fluids, and nutrition; pain management, preferably with nonopioid medications; and avoidance of certain medications such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and cholinesterase inhibitors.

The guidelines are part of a larger package that includes patient resources, evidence tables and journal articles, and other companion public education materials, available on the AGS website.

The American Geriatrics Society has released its new Clinical Practice Guideline for Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults, which the society hopes will enable health care professionals to improve delirium prevention and treatment through evidence-based measures.

Among the recommendations for treating delirium in geriatric postsurgical patients are nonpharmacologic interventions such as mobility and walking, avoiding physical restraints, and assuring adequate oxygen, fluids, and nutrition; pain management, preferably with nonopioid medications; and avoidance of certain medications such as antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and cholinesterase inhibitors.

The guidelines are part of a larger package that includes patient resources, evidence tables and journal articles, and other companion public education materials, available on the AGS website.

Postexposure smallpox vaccination not recommended for immunodeficient patients

Persons exposed to smallpox should be vaccinated with a replication-competent vaccine, unless they are severely immunodeficient, according to a guideline from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Severely immunodeficient persons won’t benefit from a smallpox vaccination because there will likely be a poor immune response and heightened risk of negative events. These include bone marrow transplant recipients within 4 months of transplantation, people infected with HIV with CD4 cell counts <50 cells/mm3, persons with severe combined immunodeficiency, complete DiGeorge syndrome patients, and people with other severely immunocompromised states requiring isolation.

“If antivirals are not immediately available, it is reasonable to consider the use of Imvamune in the setting of a smallpox virus exposure in persons with severe immunodeficiency,” the CDC added.