User login

Broad application of JNC-8 would save lives, reduce costs

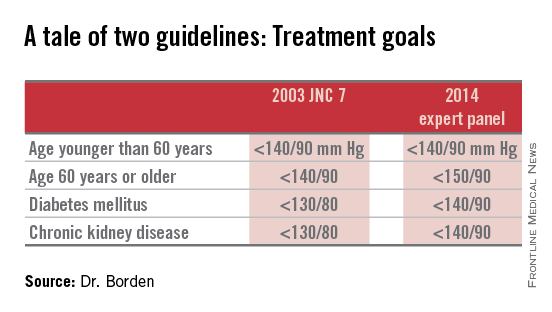

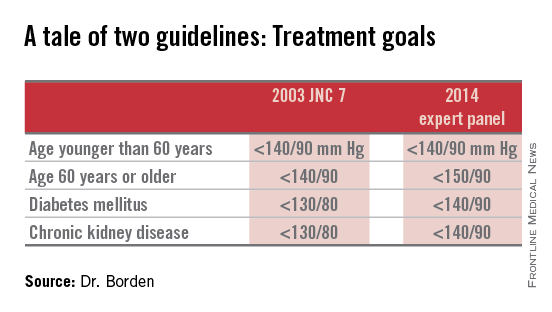

Antihypertensive therapy would prevent about 56,000 cardiovascular events annually and 13,000 deaths from strokes, myocardial infarctions, and other causes if it were used by all U.S. adults who qualify for treatment under 2014 Joint National Committee hypertension guidelines, according to computer modeling published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

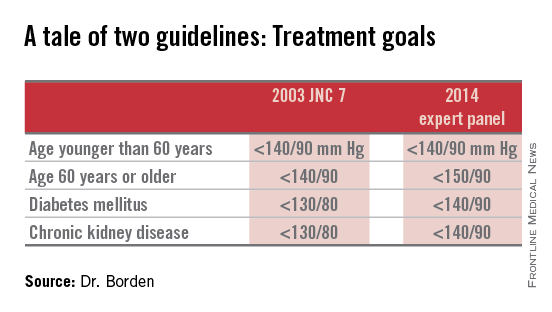

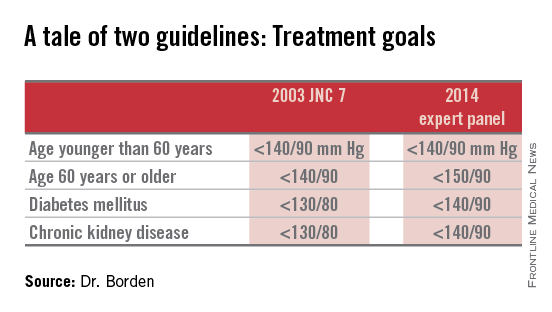

Even though the new Joint Committee guidelines are a bit less stringent than the committee’s prior 2003 advice, blood pressure remains inadequately controlled in 44% of the 64 million U.S. adults with hypertension, according to the investigators, led by Dr. Andrew Moran of Columbia University Medical Center, New York (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:447-55).

The team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Framingham Heart Study, and other sources to estimate costs and benefits of expanding treatment to all U.S. adults aged 35-74 years who meet the 2014 benchmarks. They then calculated cost-effectiveness of expanding use in various subpopulations, using $50,000/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, or less, as their cut-off.

Overall, the investigators found that fuller implementation of the Joint Committee goals would pay for itself in reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The results were driven primarily by secondary prevention in patients with cardiovascular disease and primary prevention in patients with stage 2 hypertension, meaning systolic BP of 160 mm Hg or higher or diastolic BP of 100 mm Hg or higher.

“There is an enormous potential for improving population health by expanding treatment and improving control. Our findings clearly show that it would be worthwhile to significantly increase spending on office visits, home blood pressure monitoring, and interventions to improve treatment adherence. In fact, we could double treatment and monitoring spending for some patients – namely those with severe hypertension – and still break even,” Dr. Moran said in a statement announcing the results.

Treatment of patients with existing cardiovascular disease or stage 2 hypertension would save lives and costs in all men 35-74 years old and in women aged 45-74 years. The treatment of more modest hypertension – systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of 90-99 mm Hg – was cost effective for all men and for women also between the ages of 45 and 74 years, but treating women 35-44 years old with moderate hypertension and diabetes or kidney disease had intermediate cost-effectiveness ($125,000 per QALY), and low cost-effectiveness ($181,000 per QALY) if those comorbidities were not present.

“Some people will be alarmed about our conclusion that it may not be cost effective to treat hypertension in young adults, especially young women. It’s worth noting that our analysis didn’t capture the cumulative, lifetime effects of hypertension. It may well turn out to be cost effective to treat this group if we look at data on costs and benefits over several decades,” Dr. Moran said.

The team assumed a medication adherence rate of 75%. The costs of treatment included medications, monitoring, and drug side effects.

They did not analyze the effect of diet and lifestyle interventions for lowering blood pressure, or compare the cost-effectiveness of specific antihypertensive medication classes or combinations.

The work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, among others. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Antihypertensive therapy would prevent about 56,000 cardiovascular events annually and 13,000 deaths from strokes, myocardial infarctions, and other causes if it were used by all U.S. adults who qualify for treatment under 2014 Joint National Committee hypertension guidelines, according to computer modeling published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the new Joint Committee guidelines are a bit less stringent than the committee’s prior 2003 advice, blood pressure remains inadequately controlled in 44% of the 64 million U.S. adults with hypertension, according to the investigators, led by Dr. Andrew Moran of Columbia University Medical Center, New York (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:447-55).

The team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Framingham Heart Study, and other sources to estimate costs and benefits of expanding treatment to all U.S. adults aged 35-74 years who meet the 2014 benchmarks. They then calculated cost-effectiveness of expanding use in various subpopulations, using $50,000/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, or less, as their cut-off.

Overall, the investigators found that fuller implementation of the Joint Committee goals would pay for itself in reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The results were driven primarily by secondary prevention in patients with cardiovascular disease and primary prevention in patients with stage 2 hypertension, meaning systolic BP of 160 mm Hg or higher or diastolic BP of 100 mm Hg or higher.

“There is an enormous potential for improving population health by expanding treatment and improving control. Our findings clearly show that it would be worthwhile to significantly increase spending on office visits, home blood pressure monitoring, and interventions to improve treatment adherence. In fact, we could double treatment and monitoring spending for some patients – namely those with severe hypertension – and still break even,” Dr. Moran said in a statement announcing the results.

Treatment of patients with existing cardiovascular disease or stage 2 hypertension would save lives and costs in all men 35-74 years old and in women aged 45-74 years. The treatment of more modest hypertension – systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of 90-99 mm Hg – was cost effective for all men and for women also between the ages of 45 and 74 years, but treating women 35-44 years old with moderate hypertension and diabetes or kidney disease had intermediate cost-effectiveness ($125,000 per QALY), and low cost-effectiveness ($181,000 per QALY) if those comorbidities were not present.

“Some people will be alarmed about our conclusion that it may not be cost effective to treat hypertension in young adults, especially young women. It’s worth noting that our analysis didn’t capture the cumulative, lifetime effects of hypertension. It may well turn out to be cost effective to treat this group if we look at data on costs and benefits over several decades,” Dr. Moran said.

The team assumed a medication adherence rate of 75%. The costs of treatment included medications, monitoring, and drug side effects.

They did not analyze the effect of diet and lifestyle interventions for lowering blood pressure, or compare the cost-effectiveness of specific antihypertensive medication classes or combinations.

The work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, among others. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Antihypertensive therapy would prevent about 56,000 cardiovascular events annually and 13,000 deaths from strokes, myocardial infarctions, and other causes if it were used by all U.S. adults who qualify for treatment under 2014 Joint National Committee hypertension guidelines, according to computer modeling published online Jan. 28 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the new Joint Committee guidelines are a bit less stringent than the committee’s prior 2003 advice, blood pressure remains inadequately controlled in 44% of the 64 million U.S. adults with hypertension, according to the investigators, led by Dr. Andrew Moran of Columbia University Medical Center, New York (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:447-55).

The team used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the Framingham Heart Study, and other sources to estimate costs and benefits of expanding treatment to all U.S. adults aged 35-74 years who meet the 2014 benchmarks. They then calculated cost-effectiveness of expanding use in various subpopulations, using $50,000/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, or less, as their cut-off.

Overall, the investigators found that fuller implementation of the Joint Committee goals would pay for itself in reduced cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The results were driven primarily by secondary prevention in patients with cardiovascular disease and primary prevention in patients with stage 2 hypertension, meaning systolic BP of 160 mm Hg or higher or diastolic BP of 100 mm Hg or higher.

“There is an enormous potential for improving population health by expanding treatment and improving control. Our findings clearly show that it would be worthwhile to significantly increase spending on office visits, home blood pressure monitoring, and interventions to improve treatment adherence. In fact, we could double treatment and monitoring spending for some patients – namely those with severe hypertension – and still break even,” Dr. Moran said in a statement announcing the results.

Treatment of patients with existing cardiovascular disease or stage 2 hypertension would save lives and costs in all men 35-74 years old and in women aged 45-74 years. The treatment of more modest hypertension – systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or a diastolic BP of 90-99 mm Hg – was cost effective for all men and for women also between the ages of 45 and 74 years, but treating women 35-44 years old with moderate hypertension and diabetes or kidney disease had intermediate cost-effectiveness ($125,000 per QALY), and low cost-effectiveness ($181,000 per QALY) if those comorbidities were not present.

“Some people will be alarmed about our conclusion that it may not be cost effective to treat hypertension in young adults, especially young women. It’s worth noting that our analysis didn’t capture the cumulative, lifetime effects of hypertension. It may well turn out to be cost effective to treat this group if we look at data on costs and benefits over several decades,” Dr. Moran said.

The team assumed a medication adherence rate of 75%. The costs of treatment included medications, monitoring, and drug side effects.

They did not analyze the effect of diet and lifestyle interventions for lowering blood pressure, or compare the cost-effectiveness of specific antihypertensive medication classes or combinations.

The work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, among others. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Even young patients, in many cases, can benefit from adherence to theJoint National Committee 2014 hypertension guidelines.

Major finding: The treatment of modest hypertension is cost effective for men 35-74 years old, and women between the ages of 45 and 74 years, meaning that each quality-adjusted life-year gained would cost less than $50,000.

Data source: Computer estimates of the impact of applying JNC-8 to all hypertensive U.S. adults 35-74 years old.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, among others. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ACOG outlines new treatment options for hypertensive emergencies in pregnancy

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has added nifedipine as a first-line treatment for acute-onset severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period in an updated opinion from its Committee on Obstetric Practice.

The update, released on Jan. 22, points to studies showing that women who received oral nifedipine had their blood pressure lowered more quickly than with either intravenous labetalol or hydralazine – the traditional first-line treatments – and had a significant increase in urine output. Concerns about neuromuscular blockade and severe hypotension with the use of nifedipine and magnesium sulphate were not borne out in a large review, the committee members wrote, but they advised careful monitoring since both drugs are calcium antagonists.

The committee opinion includes model order sets for the use of labetalol, hydralazine, and nifedipine for the initial management of acute onset severe hypertension in women who are pregnant or post partum with preeclampsia or eclampsia (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:521-5).

While all three medications are appropriate in treating hypertensive emergencies during pregnancy, each drug has adverse effects.

For instance, parenteral hydralazine can increase the risk of maternal hypotension. Parenteral labetalol may cause neonatal bradycardia and should be avoided in women with asthma, heart disease, or heart failure. Nifedipine has been associated with increased maternal heart rate and overshoot hypotension.

“Patients may respond to one drug and not another,” the committee noted.

The ACOG committee also called for standardized clinical guidelines for the management of patients with preeclampsia and eclampsia.

“With the advent of pregnancy hypertension guidelines in the United Kingdom, care of maternity patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia improved significantly and maternal mortality rates decreased because of a reduction in cerebral and respiratory complications,” they wrote. “Individuals and institutions should have mechanisms in place to initiate the prompt administration of medication when a patient presents with a hypertensive emergency.”

The committee recommended checklists as one tool to help standardize the use of guidelines.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has added nifedipine as a first-line treatment for acute-onset severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period in an updated opinion from its Committee on Obstetric Practice.

The update, released on Jan. 22, points to studies showing that women who received oral nifedipine had their blood pressure lowered more quickly than with either intravenous labetalol or hydralazine – the traditional first-line treatments – and had a significant increase in urine output. Concerns about neuromuscular blockade and severe hypotension with the use of nifedipine and magnesium sulphate were not borne out in a large review, the committee members wrote, but they advised careful monitoring since both drugs are calcium antagonists.

The committee opinion includes model order sets for the use of labetalol, hydralazine, and nifedipine for the initial management of acute onset severe hypertension in women who are pregnant or post partum with preeclampsia or eclampsia (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:521-5).

While all three medications are appropriate in treating hypertensive emergencies during pregnancy, each drug has adverse effects.

For instance, parenteral hydralazine can increase the risk of maternal hypotension. Parenteral labetalol may cause neonatal bradycardia and should be avoided in women with asthma, heart disease, or heart failure. Nifedipine has been associated with increased maternal heart rate and overshoot hypotension.

“Patients may respond to one drug and not another,” the committee noted.

The ACOG committee also called for standardized clinical guidelines for the management of patients with preeclampsia and eclampsia.

“With the advent of pregnancy hypertension guidelines in the United Kingdom, care of maternity patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia improved significantly and maternal mortality rates decreased because of a reduction in cerebral and respiratory complications,” they wrote. “Individuals and institutions should have mechanisms in place to initiate the prompt administration of medication when a patient presents with a hypertensive emergency.”

The committee recommended checklists as one tool to help standardize the use of guidelines.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has added nifedipine as a first-line treatment for acute-onset severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period in an updated opinion from its Committee on Obstetric Practice.

The update, released on Jan. 22, points to studies showing that women who received oral nifedipine had their blood pressure lowered more quickly than with either intravenous labetalol or hydralazine – the traditional first-line treatments – and had a significant increase in urine output. Concerns about neuromuscular blockade and severe hypotension with the use of nifedipine and magnesium sulphate were not borne out in a large review, the committee members wrote, but they advised careful monitoring since both drugs are calcium antagonists.

The committee opinion includes model order sets for the use of labetalol, hydralazine, and nifedipine for the initial management of acute onset severe hypertension in women who are pregnant or post partum with preeclampsia or eclampsia (Obstet. Gynecol. 2015;125:521-5).

While all three medications are appropriate in treating hypertensive emergencies during pregnancy, each drug has adverse effects.

For instance, parenteral hydralazine can increase the risk of maternal hypotension. Parenteral labetalol may cause neonatal bradycardia and should be avoided in women with asthma, heart disease, or heart failure. Nifedipine has been associated with increased maternal heart rate and overshoot hypotension.

“Patients may respond to one drug and not another,” the committee noted.

The ACOG committee also called for standardized clinical guidelines for the management of patients with preeclampsia and eclampsia.

“With the advent of pregnancy hypertension guidelines in the United Kingdom, care of maternity patients with preeclampsia or eclampsia improved significantly and maternal mortality rates decreased because of a reduction in cerebral and respiratory complications,” they wrote. “Individuals and institutions should have mechanisms in place to initiate the prompt administration of medication when a patient presents with a hypertensive emergency.”

The committee recommended checklists as one tool to help standardize the use of guidelines.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Psoriasis treatment recommendations address four clinical scenarios

New guidelines on nail psoriasis address four clinical manifestations of the disease. The recommendations by the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation appeared as a consensus statement in the January issue of JAMA Dermatology.

Limitations in clinical trial data make comparing treatments difficult, noted lead author Dr. Jeffrey J. Crowley of Bakersfield (Calif.) Dermatology and his associates. “There are limited data to evaluate or support the use of combination therapy in nail psoriasis. Thus, treatment options recommended in this review are monotherapy,” the guidelines authors added (JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:87-94).

To develop the guidelines, the research team searched PubMed for articles on nail psoriasis dating from Jan. 1, 1947 through May 11, 2014. They evaluated these studies for level of evidence based on recommendations for writing guidelines from Dr. Paul G. Shekelle of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center and his associates (BMJ 1999;318:593-6).

They also polled the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation regarding their treatment approach for four clinical presentations of nail psoriasis:

• For treatment-naive patients with psoriasis of the nails only (affecting at least 3 of 10 fingernails), the board recommended initial treatment with high-potency topical corticosteroids (with or without calcipotriol), with intralesional corticosteroids as a secondary option. Intralesional corticosteroids have been used for decades, but clinical data supporting their use are “extremely limited,” the guidelines state.

• For extensive nail psoriasis (affecting at least five fingernails and causing moderate to severe pain) that has failed topical treatment, the board recommended adalimumab most enthusiastically, followed by etanercept, intralesional corticosteroids, ustekinumab, methotrexate sodium, and acitretin in decreasing order.

• For concurrent skin and nail disease without joint involvement (defined as skin disease on at least 8% of the body surface and moderately to severely painful dystrophy of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board strongly recommended adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab, and also recommended methotrexate, acitretin, infliximab, and apremilast.

• For concurrent nail, skin, and joint involvement (defined as skin disease on 8% of the body surface, a history of dactylitis and morning stiffness (psoriatic arthritis), and severe, painful involvement of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board most strongly recommended adalimumab, followed by etanercept, ustekinumab, infliximab, methotrexate, apremilast, and golimumab.

Because nails grow slowly, psoriatic joint and skin disease often improve before nail psoriasis does, the authors noted. “Few studies show any significant improvement before 12 weeks, and several studies with etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab demonstrate continued improvement beyond 6 months,” they wrote.

About half of patients with psoriasis have some amount of nail involvement, and about 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail disease, according to the literature review. Dermatophyte infections can further complicate treatment of nail psoriasis, and immunosuppressive therapies can lead to onychomycosis in patients whose psoriasis includes the toenails, the authors added.

Dr. Crowley reported speaker and consulting honoraria from AbbVie, Abbott, and Amgen, and research funding from Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Four coauthors reported advisory, consulting, or financial relationships with Amgen, Abbott, Janssen Biotech Inc., Celgene, Novartis International AG, Abbvie, Merck, Celgene, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

New guidelines on nail psoriasis address four clinical manifestations of the disease. The recommendations by the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation appeared as a consensus statement in the January issue of JAMA Dermatology.

Limitations in clinical trial data make comparing treatments difficult, noted lead author Dr. Jeffrey J. Crowley of Bakersfield (Calif.) Dermatology and his associates. “There are limited data to evaluate or support the use of combination therapy in nail psoriasis. Thus, treatment options recommended in this review are monotherapy,” the guidelines authors added (JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:87-94).

To develop the guidelines, the research team searched PubMed for articles on nail psoriasis dating from Jan. 1, 1947 through May 11, 2014. They evaluated these studies for level of evidence based on recommendations for writing guidelines from Dr. Paul G. Shekelle of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center and his associates (BMJ 1999;318:593-6).

They also polled the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation regarding their treatment approach for four clinical presentations of nail psoriasis:

• For treatment-naive patients with psoriasis of the nails only (affecting at least 3 of 10 fingernails), the board recommended initial treatment with high-potency topical corticosteroids (with or without calcipotriol), with intralesional corticosteroids as a secondary option. Intralesional corticosteroids have been used for decades, but clinical data supporting their use are “extremely limited,” the guidelines state.

• For extensive nail psoriasis (affecting at least five fingernails and causing moderate to severe pain) that has failed topical treatment, the board recommended adalimumab most enthusiastically, followed by etanercept, intralesional corticosteroids, ustekinumab, methotrexate sodium, and acitretin in decreasing order.

• For concurrent skin and nail disease without joint involvement (defined as skin disease on at least 8% of the body surface and moderately to severely painful dystrophy of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board strongly recommended adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab, and also recommended methotrexate, acitretin, infliximab, and apremilast.

• For concurrent nail, skin, and joint involvement (defined as skin disease on 8% of the body surface, a history of dactylitis and morning stiffness (psoriatic arthritis), and severe, painful involvement of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board most strongly recommended adalimumab, followed by etanercept, ustekinumab, infliximab, methotrexate, apremilast, and golimumab.

Because nails grow slowly, psoriatic joint and skin disease often improve before nail psoriasis does, the authors noted. “Few studies show any significant improvement before 12 weeks, and several studies with etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab demonstrate continued improvement beyond 6 months,” they wrote.

About half of patients with psoriasis have some amount of nail involvement, and about 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail disease, according to the literature review. Dermatophyte infections can further complicate treatment of nail psoriasis, and immunosuppressive therapies can lead to onychomycosis in patients whose psoriasis includes the toenails, the authors added.

Dr. Crowley reported speaker and consulting honoraria from AbbVie, Abbott, and Amgen, and research funding from Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Four coauthors reported advisory, consulting, or financial relationships with Amgen, Abbott, Janssen Biotech Inc., Celgene, Novartis International AG, Abbvie, Merck, Celgene, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

New guidelines on nail psoriasis address four clinical manifestations of the disease. The recommendations by the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation appeared as a consensus statement in the January issue of JAMA Dermatology.

Limitations in clinical trial data make comparing treatments difficult, noted lead author Dr. Jeffrey J. Crowley of Bakersfield (Calif.) Dermatology and his associates. “There are limited data to evaluate or support the use of combination therapy in nail psoriasis. Thus, treatment options recommended in this review are monotherapy,” the guidelines authors added (JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:87-94).

To develop the guidelines, the research team searched PubMed for articles on nail psoriasis dating from Jan. 1, 1947 through May 11, 2014. They evaluated these studies for level of evidence based on recommendations for writing guidelines from Dr. Paul G. Shekelle of the VA West Los Angeles Medical Center and his associates (BMJ 1999;318:593-6).

They also polled the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation regarding their treatment approach for four clinical presentations of nail psoriasis:

• For treatment-naive patients with psoriasis of the nails only (affecting at least 3 of 10 fingernails), the board recommended initial treatment with high-potency topical corticosteroids (with or without calcipotriol), with intralesional corticosteroids as a secondary option. Intralesional corticosteroids have been used for decades, but clinical data supporting their use are “extremely limited,” the guidelines state.

• For extensive nail psoriasis (affecting at least five fingernails and causing moderate to severe pain) that has failed topical treatment, the board recommended adalimumab most enthusiastically, followed by etanercept, intralesional corticosteroids, ustekinumab, methotrexate sodium, and acitretin in decreasing order.

• For concurrent skin and nail disease without joint involvement (defined as skin disease on at least 8% of the body surface and moderately to severely painful dystrophy of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board strongly recommended adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab, and also recommended methotrexate, acitretin, infliximab, and apremilast.

• For concurrent nail, skin, and joint involvement (defined as skin disease on 8% of the body surface, a history of dactylitis and morning stiffness (psoriatic arthritis), and severe, painful involvement of at least 5 of 10 nails), the board most strongly recommended adalimumab, followed by etanercept, ustekinumab, infliximab, methotrexate, apremilast, and golimumab.

Because nails grow slowly, psoriatic joint and skin disease often improve before nail psoriasis does, the authors noted. “Few studies show any significant improvement before 12 weeks, and several studies with etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab demonstrate continued improvement beyond 6 months,” they wrote.

About half of patients with psoriasis have some amount of nail involvement, and about 70% of patients with psoriatic arthritis have nail disease, according to the literature review. Dermatophyte infections can further complicate treatment of nail psoriasis, and immunosuppressive therapies can lead to onychomycosis in patients whose psoriasis includes the toenails, the authors added.

Dr. Crowley reported speaker and consulting honoraria from AbbVie, Abbott, and Amgen, and research funding from Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Four coauthors reported advisory, consulting, or financial relationships with Amgen, Abbott, Janssen Biotech Inc., Celgene, Novartis International AG, Abbvie, Merck, Celgene, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and the National Psoriasis Foundation.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

ADA’s revised diabetes 'standards' broaden statin use

Most patients with diabetes should receive at least a moderate statin dosage regardless of their cardiovascular disease risk profile, according to the American Diabetes Association’s annual update to standards for managing patients with diabetes.

“Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2015” also shifts the ADA’s official recommendation on assessing patients for statin treatment from a decision based on blood levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol to a risk-based assessment. That change brings the ADA’s position in line with the approach advocated in late 2013 by guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-934).

The ADA released the revised standards online Dec. 23.

The statin use recommendation is “a major change, a fairly big change in how we provide care, although not that big a change in what most patients are prescribed,” said Dr. Richard W. Grant, a primary care physician and researcher at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and chair of the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee, the 14-member panel that produced the revised standards.

“We agreed [with the 2013 ACC and AHA lipid guidelines] that the decision to start a statin should be based on a patient’s cardiovascular disease risk, and it turns out that nearly every patient with type 2 diabetes should be on a statin,” Dr. Grant said in an interview.

The revised standards recommend a “moderate” statin dosage for patients with diabetes who are aged 40-75 years, as well as those who are older than 75 years even if they have no other cardiovascular disease risk factors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:S1-S94).

The dosage should be intensified to “high” for patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease, and for patients aged 40-75 years with other cardiovascular disease risk factors. For patients older than 75 years with cardiovascular disease risk factors, the new revision calls for either a moderate or high dosage.

However, for patients younger than 40 years with no cardiovascular disease or risk factors, the revised standards call for no statin treatment, a moderate or high dosage for patients younger than 40 years with risk factors, and a high dosage for those with cardiovascular disease.

The ADA’s recommendation for no statin treatment of the youngest and lowest-risk patients with diabetes is somewhat at odds with the 2013 ACC and AHA recommendations. For this patient group, those recommendations said, “statin therapy should be individualized on the basis of considerations of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk-reduction benefits, the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, and patient preferences.”

The new standards revision contains several other changes, including:

• The recommended goal diastolic blood pressure for patients with diabetes was revised to less than 90 mm Hg, an increase from the 80–mm Hg target that had been in place. That change follows a revision in the ADA’s 2014 standards that increased the systolic blood pressure target to less than 140 mm Hg.

Changing the diastolic target to less than 90 mm Hg was primarily a matter of following the best evidence that exists in the literature, Dr. Grant said, because only lower-grade evidence supports a target of less than 80 mm Hg.

The revised standards also note that the new targets of less than 140/90 mm Hg put the standards “ in harmonization” with the 2014 recommendations of the panel originally assembled at the Eighth Joint National Committee (JAMA 2014;311:507-20).

• The recommended blood glucose target when measured before eating is now 80-130 mg/dL, with the lower limit increased from 70 mg/dL. That change reflects new data that correlate blood glucose levels with blood levels of hemoglobin A1c.

• The revision sets the body mass index cutpoint for screening overweight or obese Asian Americans at 23 kg/m2, an increase from the prior cutpoint of 25 kg/m2.

• A new section devoted to managing patients with diabetes during pregnancy draws together information that previously had been scattered throughout the standards document, Dr. Grant explained. The section discusses gestational diabetes management, as well as managing women who had preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes prior to becoming pregnant.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The efficacy of a moderate statin dosage for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in patients age 40-75 years with type 2 diabetes and no other risk factors was clearly established a decade ago by results from the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS) (Lancet 2004;364:685-96).

No prospective, randomized study has proved the efficacy of statin treatment in patients younger than 40 years with diabetes and no other risk factors; but we see increasing numbers of these patients, and they, too, are at high risk for cardiovascular disease events. I agree with the 2013 recommendation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association that statin treatment should be discussed and in many cases started for these younger, lower-risk patients who still face an important cardiovascular disease risk from their diabetes alone.

Changing the target diastolic blood pressure to less than 90 mm Hg is also consistent with existing evidence. A few years ago, I wrote in an editorial that some prior blood pressure targets for patients with diabetes had been set too low (Circulation 2011;123:2776-8).

There is no evidence that patients with diabetes will benefit from a diastolic blood pressure target that is lower than less than 90 mm Hg, and an overly aggressive approach to blood pressure reduction potentially can cause adverse events. Elderly patients with diabetes often have “silent” coronary artery disease, and if their diastolic pressure goes too low, they can have inadequate coronary perfusion that will cause coronary ischemia.

|

Dr. Prakash Deedwania |

But the diastolic blood pressure target also needs individualization. Some patients, such as those with Asian ethnicity, may benefit from the greater stroke reduction achieved with more aggressive blood pressure reduction.

Aspirin use in patients with diabetes and no other cardiovascular disease risk factors has been controversial, but recent evidence from the Japanese Primary Prevention Project suggests it does not benefit patients with diabetes, even if they may also have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or both. About a third of the patients aged 60-85 years enrolled in this Japanese study had diabetes, more than 70% had dyslipidemia, and 85% had hypertension. But despite this background, daily low-dose aspirin did not reduce the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during 5 years of follow-up of more than 14,000 randomized patients (JAMA 2014;312:2510-20).

Dr. Prakash C. Deedwania is professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of cardiology at the VA Central California Health Care System in Fresno. He made these comments in an interview. He has served as a consultant to several drug companies that market statins.

The efficacy of a moderate statin dosage for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in patients age 40-75 years with type 2 diabetes and no other risk factors was clearly established a decade ago by results from the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS) (Lancet 2004;364:685-96).

No prospective, randomized study has proved the efficacy of statin treatment in patients younger than 40 years with diabetes and no other risk factors; but we see increasing numbers of these patients, and they, too, are at high risk for cardiovascular disease events. I agree with the 2013 recommendation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association that statin treatment should be discussed and in many cases started for these younger, lower-risk patients who still face an important cardiovascular disease risk from their diabetes alone.

Changing the target diastolic blood pressure to less than 90 mm Hg is also consistent with existing evidence. A few years ago, I wrote in an editorial that some prior blood pressure targets for patients with diabetes had been set too low (Circulation 2011;123:2776-8).

There is no evidence that patients with diabetes will benefit from a diastolic blood pressure target that is lower than less than 90 mm Hg, and an overly aggressive approach to blood pressure reduction potentially can cause adverse events. Elderly patients with diabetes often have “silent” coronary artery disease, and if their diastolic pressure goes too low, they can have inadequate coronary perfusion that will cause coronary ischemia.

|

Dr. Prakash Deedwania |

But the diastolic blood pressure target also needs individualization. Some patients, such as those with Asian ethnicity, may benefit from the greater stroke reduction achieved with more aggressive blood pressure reduction.

Aspirin use in patients with diabetes and no other cardiovascular disease risk factors has been controversial, but recent evidence from the Japanese Primary Prevention Project suggests it does not benefit patients with diabetes, even if they may also have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or both. About a third of the patients aged 60-85 years enrolled in this Japanese study had diabetes, more than 70% had dyslipidemia, and 85% had hypertension. But despite this background, daily low-dose aspirin did not reduce the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during 5 years of follow-up of more than 14,000 randomized patients (JAMA 2014;312:2510-20).

Dr. Prakash C. Deedwania is professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of cardiology at the VA Central California Health Care System in Fresno. He made these comments in an interview. He has served as a consultant to several drug companies that market statins.

The efficacy of a moderate statin dosage for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in patients age 40-75 years with type 2 diabetes and no other risk factors was clearly established a decade ago by results from the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS) (Lancet 2004;364:685-96).

No prospective, randomized study has proved the efficacy of statin treatment in patients younger than 40 years with diabetes and no other risk factors; but we see increasing numbers of these patients, and they, too, are at high risk for cardiovascular disease events. I agree with the 2013 recommendation from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association that statin treatment should be discussed and in many cases started for these younger, lower-risk patients who still face an important cardiovascular disease risk from their diabetes alone.

Changing the target diastolic blood pressure to less than 90 mm Hg is also consistent with existing evidence. A few years ago, I wrote in an editorial that some prior blood pressure targets for patients with diabetes had been set too low (Circulation 2011;123:2776-8).

There is no evidence that patients with diabetes will benefit from a diastolic blood pressure target that is lower than less than 90 mm Hg, and an overly aggressive approach to blood pressure reduction potentially can cause adverse events. Elderly patients with diabetes often have “silent” coronary artery disease, and if their diastolic pressure goes too low, they can have inadequate coronary perfusion that will cause coronary ischemia.

|

Dr. Prakash Deedwania |

But the diastolic blood pressure target also needs individualization. Some patients, such as those with Asian ethnicity, may benefit from the greater stroke reduction achieved with more aggressive blood pressure reduction.

Aspirin use in patients with diabetes and no other cardiovascular disease risk factors has been controversial, but recent evidence from the Japanese Primary Prevention Project suggests it does not benefit patients with diabetes, even if they may also have hypertension, dyslipidemia, or both. About a third of the patients aged 60-85 years enrolled in this Japanese study had diabetes, more than 70% had dyslipidemia, and 85% had hypertension. But despite this background, daily low-dose aspirin did not reduce the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events during 5 years of follow-up of more than 14,000 randomized patients (JAMA 2014;312:2510-20).

Dr. Prakash C. Deedwania is professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of cardiology at the VA Central California Health Care System in Fresno. He made these comments in an interview. He has served as a consultant to several drug companies that market statins.

Most patients with diabetes should receive at least a moderate statin dosage regardless of their cardiovascular disease risk profile, according to the American Diabetes Association’s annual update to standards for managing patients with diabetes.

“Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2015” also shifts the ADA’s official recommendation on assessing patients for statin treatment from a decision based on blood levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol to a risk-based assessment. That change brings the ADA’s position in line with the approach advocated in late 2013 by guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-934).

The ADA released the revised standards online Dec. 23.

The statin use recommendation is “a major change, a fairly big change in how we provide care, although not that big a change in what most patients are prescribed,” said Dr. Richard W. Grant, a primary care physician and researcher at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and chair of the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee, the 14-member panel that produced the revised standards.

“We agreed [with the 2013 ACC and AHA lipid guidelines] that the decision to start a statin should be based on a patient’s cardiovascular disease risk, and it turns out that nearly every patient with type 2 diabetes should be on a statin,” Dr. Grant said in an interview.

The revised standards recommend a “moderate” statin dosage for patients with diabetes who are aged 40-75 years, as well as those who are older than 75 years even if they have no other cardiovascular disease risk factors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:S1-S94).

The dosage should be intensified to “high” for patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease, and for patients aged 40-75 years with other cardiovascular disease risk factors. For patients older than 75 years with cardiovascular disease risk factors, the new revision calls for either a moderate or high dosage.

However, for patients younger than 40 years with no cardiovascular disease or risk factors, the revised standards call for no statin treatment, a moderate or high dosage for patients younger than 40 years with risk factors, and a high dosage for those with cardiovascular disease.

The ADA’s recommendation for no statin treatment of the youngest and lowest-risk patients with diabetes is somewhat at odds with the 2013 ACC and AHA recommendations. For this patient group, those recommendations said, “statin therapy should be individualized on the basis of considerations of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk-reduction benefits, the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, and patient preferences.”

The new standards revision contains several other changes, including:

• The recommended goal diastolic blood pressure for patients with diabetes was revised to less than 90 mm Hg, an increase from the 80–mm Hg target that had been in place. That change follows a revision in the ADA’s 2014 standards that increased the systolic blood pressure target to less than 140 mm Hg.

Changing the diastolic target to less than 90 mm Hg was primarily a matter of following the best evidence that exists in the literature, Dr. Grant said, because only lower-grade evidence supports a target of less than 80 mm Hg.

The revised standards also note that the new targets of less than 140/90 mm Hg put the standards “ in harmonization” with the 2014 recommendations of the panel originally assembled at the Eighth Joint National Committee (JAMA 2014;311:507-20).

• The recommended blood glucose target when measured before eating is now 80-130 mg/dL, with the lower limit increased from 70 mg/dL. That change reflects new data that correlate blood glucose levels with blood levels of hemoglobin A1c.

• The revision sets the body mass index cutpoint for screening overweight or obese Asian Americans at 23 kg/m2, an increase from the prior cutpoint of 25 kg/m2.

• A new section devoted to managing patients with diabetes during pregnancy draws together information that previously had been scattered throughout the standards document, Dr. Grant explained. The section discusses gestational diabetes management, as well as managing women who had preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes prior to becoming pregnant.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Most patients with diabetes should receive at least a moderate statin dosage regardless of their cardiovascular disease risk profile, according to the American Diabetes Association’s annual update to standards for managing patients with diabetes.

“Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2015” also shifts the ADA’s official recommendation on assessing patients for statin treatment from a decision based on blood levels of low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol to a risk-based assessment. That change brings the ADA’s position in line with the approach advocated in late 2013 by guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-934).

The ADA released the revised standards online Dec. 23.

The statin use recommendation is “a major change, a fairly big change in how we provide care, although not that big a change in what most patients are prescribed,” said Dr. Richard W. Grant, a primary care physician and researcher at Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and chair of the ADA’s Professional Practice Committee, the 14-member panel that produced the revised standards.

“We agreed [with the 2013 ACC and AHA lipid guidelines] that the decision to start a statin should be based on a patient’s cardiovascular disease risk, and it turns out that nearly every patient with type 2 diabetes should be on a statin,” Dr. Grant said in an interview.

The revised standards recommend a “moderate” statin dosage for patients with diabetes who are aged 40-75 years, as well as those who are older than 75 years even if they have no other cardiovascular disease risk factors (Diabetes Care 2015;38:S1-S94).

The dosage should be intensified to “high” for patients with diagnosed cardiovascular disease, and for patients aged 40-75 years with other cardiovascular disease risk factors. For patients older than 75 years with cardiovascular disease risk factors, the new revision calls for either a moderate or high dosage.

However, for patients younger than 40 years with no cardiovascular disease or risk factors, the revised standards call for no statin treatment, a moderate or high dosage for patients younger than 40 years with risk factors, and a high dosage for those with cardiovascular disease.

The ADA’s recommendation for no statin treatment of the youngest and lowest-risk patients with diabetes is somewhat at odds with the 2013 ACC and AHA recommendations. For this patient group, those recommendations said, “statin therapy should be individualized on the basis of considerations of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk-reduction benefits, the potential for adverse effects and drug-drug interactions, and patient preferences.”

The new standards revision contains several other changes, including:

• The recommended goal diastolic blood pressure for patients with diabetes was revised to less than 90 mm Hg, an increase from the 80–mm Hg target that had been in place. That change follows a revision in the ADA’s 2014 standards that increased the systolic blood pressure target to less than 140 mm Hg.

Changing the diastolic target to less than 90 mm Hg was primarily a matter of following the best evidence that exists in the literature, Dr. Grant said, because only lower-grade evidence supports a target of less than 80 mm Hg.

The revised standards also note that the new targets of less than 140/90 mm Hg put the standards “ in harmonization” with the 2014 recommendations of the panel originally assembled at the Eighth Joint National Committee (JAMA 2014;311:507-20).

• The recommended blood glucose target when measured before eating is now 80-130 mg/dL, with the lower limit increased from 70 mg/dL. That change reflects new data that correlate blood glucose levels with blood levels of hemoglobin A1c.

• The revision sets the body mass index cutpoint for screening overweight or obese Asian Americans at 23 kg/m2, an increase from the prior cutpoint of 25 kg/m2.

• A new section devoted to managing patients with diabetes during pregnancy draws together information that previously had been scattered throughout the standards document, Dr. Grant explained. The section discusses gestational diabetes management, as well as managing women who had preexisting type 1 or type 2 diabetes prior to becoming pregnant.

Dr. Grant had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

FROM DIABETES CARE

USPSTF: Use ambulatory BP screening before diagnosing hypertension

Physicians should use ambulatory blood pressure screening to confirm elevated office measurements before diagnosing hypertension, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Because high blood pressure affects nearly a third of U.S. adults, the USPSTF recommends screening all adults for high blood pressure, based on good evidence that screening and treatment reduce cardiovascular events with few major harms.

However, blood pressure fluctuates with emotion, stress, pain, physical activity, medications, and even the presence of health care providers. So, the USPSTF issued a draft, A-level recommendation to use ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring following an initial elevated screening to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, except when initiating therapy immediately is medically necessary.

Patients with blood pressure at or above 180/110 mm Hg or evidence of end-organ damage should begin drug therapy immediately. In addition, patients diagnosed with secondary hypertension do not need ambulatory monitoring confirmation.

The USPSTF recommendations are based on a meta-analysis published Dec. 22 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014: [doi10.7326/M14-1539]. Although the evidence for ambulatory screening confirmation was of good quality, the evidence base is less robust for home monitoring, the task force noted.

“Our evidence review shows that overdiagnosis of hypertension from unconfirmed office-based screening could result in unnecessary treatment in a substantial number of persons,” reported Margaret A. Piper, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, Ore., and her associates in the study. “Ambulatory BP monitoring provides multiple measurements over time in a nonmedical setting, which potentially avoids measurement error, regression to the mean, and misdiagnosis of isolated clinic hypertension, and is best correlated with long-term outcomes.”

Dr. Piper’s team searched for good- and fair-quality studies in MEDLINE, PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and CINAHL through August 2014, yielding 1 trial for the benefits of screening, 7 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of office blood pressure measurement, 11 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of ambulatory blood pressure measurement, 27 studies on using ambulatory screenings to confirm hypertension, 4 studies on harms of screening, and 40 studies on rescreening intervals and hypertension incidence in those with normal blood pressure.

The meta-analysis showed that 5%-65% of patients were not diagnosed with hypertension following ambulatory blood pressure monitoring after an initially elevated office screening measurement.

The USPSTF draft recommendation also noted past epidemiological evidence that 15%-30% of those diagnosed with hypertension may actually have lower blood pressure when not in a medical setting.

The meta-analysis also found that the risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke and cardiovascular events was “consistently and significantly associated with” elevated systolic ambulatory blood pressure, regardless of the measurements in an office.

The primary harms of screening identified in the study were greater absenteeism from work and greater illness episodes after diagnosis, as well as sleep disturbances, discomfort, and daily activity restrictions because of the ambulatory device.

On the basis of the evidence from the meta-analysis, the USPSTF recommended annual screenings for adults age 40 years and older and those at high risk for hypertension, including African Americans, those who are overweight or obese, and those with a normally high blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg). Screenings should occur every 3-5 years for those age 18-39 years with no risk factors and a normal blood pressure.

Target blood pressure should remain below 140/90 mm Hg for adults younger than 60 years, and below 150/90 mm Hg for adults 60 years or older with neither diabetes nor chronic kidney disease, according to guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the meta-analysis. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

Physicians should use ambulatory blood pressure screening to confirm elevated office measurements before diagnosing hypertension, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Because high blood pressure affects nearly a third of U.S. adults, the USPSTF recommends screening all adults for high blood pressure, based on good evidence that screening and treatment reduce cardiovascular events with few major harms.

However, blood pressure fluctuates with emotion, stress, pain, physical activity, medications, and even the presence of health care providers. So, the USPSTF issued a draft, A-level recommendation to use ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring following an initial elevated screening to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, except when initiating therapy immediately is medically necessary.

Patients with blood pressure at or above 180/110 mm Hg or evidence of end-organ damage should begin drug therapy immediately. In addition, patients diagnosed with secondary hypertension do not need ambulatory monitoring confirmation.

The USPSTF recommendations are based on a meta-analysis published Dec. 22 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014: [doi10.7326/M14-1539]. Although the evidence for ambulatory screening confirmation was of good quality, the evidence base is less robust for home monitoring, the task force noted.

“Our evidence review shows that overdiagnosis of hypertension from unconfirmed office-based screening could result in unnecessary treatment in a substantial number of persons,” reported Margaret A. Piper, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, Ore., and her associates in the study. “Ambulatory BP monitoring provides multiple measurements over time in a nonmedical setting, which potentially avoids measurement error, regression to the mean, and misdiagnosis of isolated clinic hypertension, and is best correlated with long-term outcomes.”

Dr. Piper’s team searched for good- and fair-quality studies in MEDLINE, PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and CINAHL through August 2014, yielding 1 trial for the benefits of screening, 7 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of office blood pressure measurement, 11 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of ambulatory blood pressure measurement, 27 studies on using ambulatory screenings to confirm hypertension, 4 studies on harms of screening, and 40 studies on rescreening intervals and hypertension incidence in those with normal blood pressure.

The meta-analysis showed that 5%-65% of patients were not diagnosed with hypertension following ambulatory blood pressure monitoring after an initially elevated office screening measurement.

The USPSTF draft recommendation also noted past epidemiological evidence that 15%-30% of those diagnosed with hypertension may actually have lower blood pressure when not in a medical setting.

The meta-analysis also found that the risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke and cardiovascular events was “consistently and significantly associated with” elevated systolic ambulatory blood pressure, regardless of the measurements in an office.

The primary harms of screening identified in the study were greater absenteeism from work and greater illness episodes after diagnosis, as well as sleep disturbances, discomfort, and daily activity restrictions because of the ambulatory device.

On the basis of the evidence from the meta-analysis, the USPSTF recommended annual screenings for adults age 40 years and older and those at high risk for hypertension, including African Americans, those who are overweight or obese, and those with a normally high blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg). Screenings should occur every 3-5 years for those age 18-39 years with no risk factors and a normal blood pressure.

Target blood pressure should remain below 140/90 mm Hg for adults younger than 60 years, and below 150/90 mm Hg for adults 60 years or older with neither diabetes nor chronic kidney disease, according to guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the meta-analysis. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

Physicians should use ambulatory blood pressure screening to confirm elevated office measurements before diagnosing hypertension, according to a draft recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Because high blood pressure affects nearly a third of U.S. adults, the USPSTF recommends screening all adults for high blood pressure, based on good evidence that screening and treatment reduce cardiovascular events with few major harms.

However, blood pressure fluctuates with emotion, stress, pain, physical activity, medications, and even the presence of health care providers. So, the USPSTF issued a draft, A-level recommendation to use ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring following an initial elevated screening to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, except when initiating therapy immediately is medically necessary.

Patients with blood pressure at or above 180/110 mm Hg or evidence of end-organ damage should begin drug therapy immediately. In addition, patients diagnosed with secondary hypertension do not need ambulatory monitoring confirmation.

The USPSTF recommendations are based on a meta-analysis published Dec. 22 (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014: [doi10.7326/M14-1539]. Although the evidence for ambulatory screening confirmation was of good quality, the evidence base is less robust for home monitoring, the task force noted.

“Our evidence review shows that overdiagnosis of hypertension from unconfirmed office-based screening could result in unnecessary treatment in a substantial number of persons,” reported Margaret A. Piper, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, Portland, Ore., and her associates in the study. “Ambulatory BP monitoring provides multiple measurements over time in a nonmedical setting, which potentially avoids measurement error, regression to the mean, and misdiagnosis of isolated clinic hypertension, and is best correlated with long-term outcomes.”

Dr. Piper’s team searched for good- and fair-quality studies in MEDLINE, PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and CINAHL through August 2014, yielding 1 trial for the benefits of screening, 7 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of office blood pressure measurement, 11 studies on the diagnostic accuracy of ambulatory blood pressure measurement, 27 studies on using ambulatory screenings to confirm hypertension, 4 studies on harms of screening, and 40 studies on rescreening intervals and hypertension incidence in those with normal blood pressure.

The meta-analysis showed that 5%-65% of patients were not diagnosed with hypertension following ambulatory blood pressure monitoring after an initially elevated office screening measurement.

The USPSTF draft recommendation also noted past epidemiological evidence that 15%-30% of those diagnosed with hypertension may actually have lower blood pressure when not in a medical setting.

The meta-analysis also found that the risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke and cardiovascular events was “consistently and significantly associated with” elevated systolic ambulatory blood pressure, regardless of the measurements in an office.

The primary harms of screening identified in the study were greater absenteeism from work and greater illness episodes after diagnosis, as well as sleep disturbances, discomfort, and daily activity restrictions because of the ambulatory device.

On the basis of the evidence from the meta-analysis, the USPSTF recommended annual screenings for adults age 40 years and older and those at high risk for hypertension, including African Americans, those who are overweight or obese, and those with a normally high blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg). Screenings should occur every 3-5 years for those age 18-39 years with no risk factors and a normal blood pressure.

Target blood pressure should remain below 140/90 mm Hg for adults younger than 60 years, and below 150/90 mm Hg for adults 60 years or older with neither diabetes nor chronic kidney disease, according to guidelines from the Eighth Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the meta-analysis. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Ambulatory blood pressure screening should be used to confirm elevated office measurements before diagnosing hypertension.

Major finding: 5%-65% of patients with elevated office blood pressure readings were later not diagnosed with hypertension following ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

Data source: A meta-analysis of studies on blood pressure screenings published through August 2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

Implications of cholesterol guidelines for cardiology practices

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.

But Dr. Maddox took a more sanguine view of the statin gap. Although it’s likely there is some heterogeneity in clinical practice that needs to be corrected, he cautioned that the limitations of an analysis based upon EMR data must be borne in mind. Some cardiologists probably didn’t record the use of statins at every visit, and they may not have always reliably documented patients’ intolerance of statins in the EMR.

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Maddox reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.

But Dr. Maddox took a more sanguine view of the statin gap. Although it’s likely there is some heterogeneity in clinical practice that needs to be corrected, he cautioned that the limitations of an analysis based upon EMR data must be borne in mind. Some cardiologists probably didn’t record the use of statins at every visit, and they may not have always reliably documented patients’ intolerance of statins in the EMR.

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Maddox reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.