User login

Criteria for Appropriate Use of Peripherally Inserted Central Catheters

Clinical question: What are criteria for appropriate and inappropriate use of PICCs?

Background: PICCs are commonly used in medical care in a variety of clinical contexts; however, criteria defining the appropriate use of PICCs and practices related to PICC placement have not been previously established.

Study design: A multispecialty panel classified indications for PICC use as appropriate or inappropriate using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.

Synopsis: Selected appropriate PICC uses include:

- Infusion of peripherally compatible infusates, intermittent infusions, or infrequent phlebotomy in patients with poor or difficult venous access when the expected duration of use is at least six days;

- Phlebotomy at least every eight hours when the expected duration of use is at least six days; and

- Invasive hemodynamic monitoring in a critically ill patient only if the duration of use is expected to exceed 15 days.

Selected appropriate PICC-related practices:

- Verify PICC tip position using a chest radiograph only after non-ECG or non-fluoroscopically guided PICC insertion;

- Provide an interval without a PICC to allow resolution of bacteremia when managing PICC-related bloodstream infections; and

- For PICC-related DVT, provide at least three months of systemic anticoagulation if not otherwise contraindicated.

Selected inappropriate PICC-related practices:

- Adjustment of PICC tips that reside in the lower third of the superior vena cava, cavoatrial junction, or right atrium; and

- Removal or replacement of PICCs that are clinically necessary, well positioned, and functional in the setting of PICC-related DVT or without evidence of catheter-associated bloodstream infection.

Bottom line: A multispecialty expert panel provides guidance for appropriate use of PICCs and PICC-related practices.

Citation: Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan appropriateness guide for intravenous catheters (MAGIC): results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):S1-S40.

Clinical question: What are criteria for appropriate and inappropriate use of PICCs?

Background: PICCs are commonly used in medical care in a variety of clinical contexts; however, criteria defining the appropriate use of PICCs and practices related to PICC placement have not been previously established.

Study design: A multispecialty panel classified indications for PICC use as appropriate or inappropriate using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.

Synopsis: Selected appropriate PICC uses include:

- Infusion of peripherally compatible infusates, intermittent infusions, or infrequent phlebotomy in patients with poor or difficult venous access when the expected duration of use is at least six days;

- Phlebotomy at least every eight hours when the expected duration of use is at least six days; and

- Invasive hemodynamic monitoring in a critically ill patient only if the duration of use is expected to exceed 15 days.

Selected appropriate PICC-related practices:

- Verify PICC tip position using a chest radiograph only after non-ECG or non-fluoroscopically guided PICC insertion;

- Provide an interval without a PICC to allow resolution of bacteremia when managing PICC-related bloodstream infections; and

- For PICC-related DVT, provide at least three months of systemic anticoagulation if not otherwise contraindicated.

Selected inappropriate PICC-related practices:

- Adjustment of PICC tips that reside in the lower third of the superior vena cava, cavoatrial junction, or right atrium; and

- Removal or replacement of PICCs that are clinically necessary, well positioned, and functional in the setting of PICC-related DVT or without evidence of catheter-associated bloodstream infection.

Bottom line: A multispecialty expert panel provides guidance for appropriate use of PICCs and PICC-related practices.

Citation: Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan appropriateness guide for intravenous catheters (MAGIC): results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):S1-S40.

Clinical question: What are criteria for appropriate and inappropriate use of PICCs?

Background: PICCs are commonly used in medical care in a variety of clinical contexts; however, criteria defining the appropriate use of PICCs and practices related to PICC placement have not been previously established.

Study design: A multispecialty panel classified indications for PICC use as appropriate or inappropriate using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method.

Synopsis: Selected appropriate PICC uses include:

- Infusion of peripherally compatible infusates, intermittent infusions, or infrequent phlebotomy in patients with poor or difficult venous access when the expected duration of use is at least six days;

- Phlebotomy at least every eight hours when the expected duration of use is at least six days; and

- Invasive hemodynamic monitoring in a critically ill patient only if the duration of use is expected to exceed 15 days.

Selected appropriate PICC-related practices:

- Verify PICC tip position using a chest radiograph only after non-ECG or non-fluoroscopically guided PICC insertion;

- Provide an interval without a PICC to allow resolution of bacteremia when managing PICC-related bloodstream infections; and

- For PICC-related DVT, provide at least three months of systemic anticoagulation if not otherwise contraindicated.

Selected inappropriate PICC-related practices:

- Adjustment of PICC tips that reside in the lower third of the superior vena cava, cavoatrial junction, or right atrium; and

- Removal or replacement of PICCs that are clinically necessary, well positioned, and functional in the setting of PICC-related DVT or without evidence of catheter-associated bloodstream infection.

Bottom line: A multispecialty expert panel provides guidance for appropriate use of PICCs and PICC-related practices.

Citation: Chopra V, Flanders SA, Saint S, et al. The Michigan appropriateness guide for intravenous catheters (MAGIC): results from a multispecialty panel using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):S1-S40.

ACP Guidelines for Evaluation of Suspected Pulmonary Embolism

Clinical question: What are best practices for evaluating patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism (PE)?

Background: Use of CT in the evaluation of PE has increased across all clinical settings without improving mortality. Contrast CT carries the risks of radiation exposure, contrast-induced nephropathy, and incidental findings that require further investigation. The authors highlight evidence-based strategies for evaluation of PE, focusing on delivering high-value care.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Literature review of studies across all adult clinical settings.

Synopsis: The clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians conducted a literature search surrounding evaluation of suspected acute PE. From their review, they concluded:

- Pretest probability should initially be determined based on validated prediction tools (Wells score, Revised Geneva);

- In patients found to have low pretest probability and meeting the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC), clinicians can forego d-dimer testing;

- In those with intermediate pretest probability or those with low pre-test probability who do not pass PERC, d-dimer measurement should be obtained;

- The d-dimer threshold should be age adjusted and imaging should not be pursued in patients whose d-dimer level falls below this cutoff, while those with positive d-dimers should receive CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and

- Patients with high pretest probability should undergo CTPA (or V/Q scan if CTPA is contraindicated) without d-dimer testing.

Bottom line: In suspected acute PE, first determine pretest probability using Wells and Revised Geneva, and then use this probability in conjunction with the PERC and d-dimer (as indicated) to guide decisions about imaging.

Citation: Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Fitterman N, Schuur JD. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711.

Clinical question: What are best practices for evaluating patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism (PE)?

Background: Use of CT in the evaluation of PE has increased across all clinical settings without improving mortality. Contrast CT carries the risks of radiation exposure, contrast-induced nephropathy, and incidental findings that require further investigation. The authors highlight evidence-based strategies for evaluation of PE, focusing on delivering high-value care.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Literature review of studies across all adult clinical settings.

Synopsis: The clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians conducted a literature search surrounding evaluation of suspected acute PE. From their review, they concluded:

- Pretest probability should initially be determined based on validated prediction tools (Wells score, Revised Geneva);

- In patients found to have low pretest probability and meeting the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC), clinicians can forego d-dimer testing;

- In those with intermediate pretest probability or those with low pre-test probability who do not pass PERC, d-dimer measurement should be obtained;

- The d-dimer threshold should be age adjusted and imaging should not be pursued in patients whose d-dimer level falls below this cutoff, while those with positive d-dimers should receive CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and

- Patients with high pretest probability should undergo CTPA (or V/Q scan if CTPA is contraindicated) without d-dimer testing.

Bottom line: In suspected acute PE, first determine pretest probability using Wells and Revised Geneva, and then use this probability in conjunction with the PERC and d-dimer (as indicated) to guide decisions about imaging.

Citation: Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Fitterman N, Schuur JD. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711.

Clinical question: What are best practices for evaluating patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism (PE)?

Background: Use of CT in the evaluation of PE has increased across all clinical settings without improving mortality. Contrast CT carries the risks of radiation exposure, contrast-induced nephropathy, and incidental findings that require further investigation. The authors highlight evidence-based strategies for evaluation of PE, focusing on delivering high-value care.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Literature review of studies across all adult clinical settings.

Synopsis: The clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians conducted a literature search surrounding evaluation of suspected acute PE. From their review, they concluded:

- Pretest probability should initially be determined based on validated prediction tools (Wells score, Revised Geneva);

- In patients found to have low pretest probability and meeting the pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC), clinicians can forego d-dimer testing;

- In those with intermediate pretest probability or those with low pre-test probability who do not pass PERC, d-dimer measurement should be obtained;

- The d-dimer threshold should be age adjusted and imaging should not be pursued in patients whose d-dimer level falls below this cutoff, while those with positive d-dimers should receive CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA); and

- Patients with high pretest probability should undergo CTPA (or V/Q scan if CTPA is contraindicated) without d-dimer testing.

Bottom line: In suspected acute PE, first determine pretest probability using Wells and Revised Geneva, and then use this probability in conjunction with the PERC and d-dimer (as indicated) to guide decisions about imaging.

Citation: Raja AS, Greenberg JO, Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Fitterman N, Schuur JD. Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(9):701-711.

When Should Hospitalists Order Continuous Cardiac Monitoring?

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

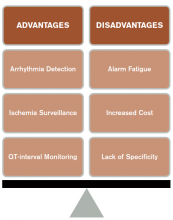

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

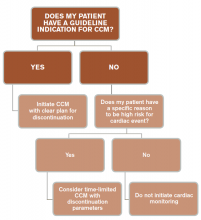

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

Case

Two patients on continuous cardiac monitoring (CCM) are admitted to the hospital. One is a 56-year-old man with hemodynamically stable sepsis secondary to pneumonia. There is no sign of arrhythmia on initial evaluation. The second patient is a 67-year-old man with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD) admitted with chest pain. Should these patients be admitted with CCM?

Overview

CCM was first introduced in hospitals in the early 1960s for heart rate and rhythm monitoring in coronary ICUs. Since that time, CCM has been widely used in the hospital setting among critically and noncritically ill patients. Some hospitals have a limited capacity for monitoring, which is dictated by bed or technology availability. Other hospitals have the ability to monitor any patient.

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) in 1991 and the American Heart Association (AHA) in 2004 guide inpatient use of CCM. These guidelines make recommendations based on the likelihood of patient benefit—will likely benefit, may benefit, unlikely to benefit—and are primarily based on expert opinion; rigorous clinical trial data is not available.1,2 Based on these guidelines, patients with primary cardiac diagnoses, including acute coronary syndrome (ACS), post-cardiac surgery, and arrhythmia, are the most likely to benefit from monitoring.2,3

In practical use, many hospitalists use CCM to detect signs of hemodynamic instability.3 Currently there is no data to support the idea that CCM is a safe or equivalent method of detecting hemodynamic instability compared to close clinical evaluation and frequent vital sign measurement. In fact, physicians overestimate the utility of CCM in guiding management decisions, and witnessed clinical deterioration is a more frequent factor in the decision to escalate the level of care of a patient.3,4

Guideline Recommendations

CCM is intended to identify life-threatening arrhythmias, ischemia, and QT prolongation (see Figure 1). The AHA guidelines address which patients will benefit from CCM; the main indications include an acute cardiac diagnosis or critical illness.1

In addition, the AHA guidelines provide recommendations for the duration of monitoring. These recommendations vary from time-limited monitoring (e.g. unexplained syncope) to a therapeutic-based recommendation (e.g. high-grade atrioventricular block requiring pacemaker placement).

The guidelines also identify a subset of patients who are unlikely to benefit from monitoring (Class III), including low-risk post-operative patients, patients with rate-controlled atrial fibrillation, and patients undergoing hemodialysis without other indications for monitoring.

Several studies have examined the frequency of CCM use. In one study of 236 admissions to a community hospital general ward population, approximately 50% of the 745 monitoring days were not indicated by ACC/AHA guidelines.5 In this study, only 5% of telemetry events occurred in patients without indications, and none of these events required any specific therapy.5 Thus, improved adherence to the ACC/AHA guidelines can decrease CCM use in patients who are unlikely to benefit.

Life-threatening arrhythmia detection. Cleverley and colleagues reported that patients who suffered a cardiac arrest on noncritical care units had a higher survival to hospital discharge if they were on CCM during the event.6 However, a similar study recently showed no benefit to cardiac monitoring for in-hospital arrest if patients were monitored remotely.7 Patients who experience a cardiac arrest in a noncritical care area may benefit from direct cardiac monitoring, though larger studies are needed to assess all potential confounding effects, including nurse-to-patient ratios, location of monitoring (remote or unit-based), advanced cardiac life support response times, and whether the event was witnessed.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend use of CCM in patients with a higher likelihood of developing a life-threatening arrhythmia, including those with an ACS, those experiencing post-cardiac arrest, or those who are critically ill. Medical ward patients who should be monitored include those with acute or subacute congestive heart failure, syncope of unknown etiology, and uncontrolled atrial fibrillation.1

Ischemia surveillance. Computerized ST-segment monitoring has been available for high-risk post-operative patients and those with acute cardiac events since the mid-1980s. When properly used, it offers the ability to detect “silent” ischemia, which is associated with increased in-hospital complications and worse patient outcomes.

Computerized ST-segment monitoring is often associated with a high rate of false positive alarms, however, and has not been universally adopted. Recommendations for its use are based on expert opinion, because no randomized trial has shown that increasing the sensitivity of ischemia detection improves patient outcomes.

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend ST-segment monitoring in patients with early ACS and post-acute MI as well as in patients at high risk for silent ischemia, including high-risk post-operative patients.1

QT-interval monitoring. A corrected QT-interval (QTc) greater than 0.50 milliseconds correlates with a higher risk for torsades de pointes and is associated with higher mortality. In critically ill patients in a large academic medical center, guideline-based QT-interval monitoring showed poor specificity for predicting the development of QTc prolongation; however, the risk of QTc prolongation increased with the presence of multiple risk factors.8

Bottom line: AHA guidelines recommend QT-interval monitoring in patients with risk factors for QTc-prolongation, including those starting QTc-prolonging drugs, those with overdose of pro-arrhythmic drugs, those with new-onset bradyarrhythmias, those with severe hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia, and those who have experienced acute neurologic events.1

Recommendations Outside of Guidelines

Patients admitted to medical services for noncardiac diagnoses have a high rate of telemetry use and a perceived benefit associated with cardiac monitoring.3 Although guidelines for noncardiac patients to direct hospitalists on when to use this technology are lacking, there may be some utility in monitoring certain subsets of inpatients.

Sepsis. Patients with hemodynamically stable sepsis develop atrial fibrillation at a higher rate than patients without sepsis and have higher in-hospital mortality. Patients at highest risk are those who are elderly or have severe sepsis.7 CCM can identify atrial fibrillation in real time, which may allow for earlier intervention; however, it is important to consider that other modalities, such as patient symptoms, physical exam, and standard EKG, are potentially as effective at detecting atrial fibrillation as CCM.

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients who are at higher risk, including elderly patients and those with severe sepsis, until sepsis has resolved and/or the patient is hemodynamically stable for 24 hours.

Alcohol withdrawal. Patients with severe alcohol withdrawal have an increased incidence of arrhythmia and ischemia during the detoxification process. Specifically, patients with delirium tremens and seizures are at higher risk for significant QTc prolongation and tachyarrhythmias.9

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM in patients with severe alcohol withdrawal and to discontinue monitoring once withdrawal has resolved.

COPD. Patients with COPD exacerbations have a high risk of in-hospital and long-term mortality. The highest risk for mortality appears to be in patients presenting with atrial or ventricular arrhythmias and those over 65 years old.10 There is no clear evidence that beta-agonist use in COPD exacerbations increases arrhythmias other than sinus tachycardia or is associated with worse outcomes.11

Bottom line: Our recommendation is to use CCM only in patients with COPD exacerbation who have other indications as described in the AHA guidelines.

CCM Disadvantages

Alarm fatigue. Alarm fatigue is defined as the desensitization of a clinician to an alarm stimulus, resulting from sensory overload and causing the response of an alarm to be delayed or dismissed.12 In 2014, the Emergency Care Research Institute named alarm hazards as the number one health technology hazard, noting that numerous alarms on a daily basis can lead to desensitization and “alarm fatigue.”

CCM, and the overuse of CCM in particular, contribute to alarm fatigue, which can lead to patient safety issues, including delays in treatment, medication errors, and potentially death.

Increased cost. Because telemetry requires specialized equipment and trained monitoring staff, cost can be significant. In addition to equipment, cost includes time spent by providers, nurses, and technicians interpreting the images and discussing findings with consultants, as well as the additional studies obtained as a result of identified arrhythmias.

Studies on CCM cost vary widely, with conservative estimates of approximately $53 to as much as $1,400 per patient per day in some hospitals.13

Lack of specificity. Because of the high sensitivity and low specificity of CCM, use of CCM in low-risk patients without indications increases the risk of misinterpreting false-positive findings as clinically significant. This can lead to errors in management, including overtesting, unnecessary consultation with subspecialists, and the potential for inappropriate invasive procedures.1

High-Value CCM Use

Because of the low value associated with cardiac monitoring in many patients and the high sensitivity of the guidelines to capture patients at high risk for cardiac events, many hospitals have sought to limit the overuse of this technology. The most successful interventions have targeted the electronic ordering system by requiring an indication and hardwiring an order duration based on guideline recommendations. In a recent study, this intervention led to a 70% decrease in usage and reported $4.8 million cost savings without increasing the rate of in-hospital rapid response or cardiac arrest.14

Systems-level interventions to decrease inappropriate initiation and facilitate discontinuation of cardiac monitoring are a proven way to increase compliance with guidelines and decrease the overuse of CCM.

Back to the Case

According to AHA guidelines, the only patient who has an indication for CCM is the 67-year-old man with known CAD and chest pain, and, accordingly, the patient was placed on CCM. The patient underwent evaluation for ACS, and monitoring was discontinued after 24 hours when ACS was ruled out. The 56-year-old man with sepsis responded to treatment of pneumonia and was not placed on CCM.

In general, patients admitted with acute cardiac-related diseases should be placed on CCM. Guidelines are lacking with respect to many noncardiac diseases, and we recommend a time-limited duration (typically 24 hours) if CCM is ordered for a patient with a special circumstance outside of guidelines (see Figure 3).

Key Takeaway

Hospitalists should use continuous cardiac monitoring for specific indications and not routinely for all patients.

Drs. Lacy and Rendon are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. Dr. Davis is a resident in internal medicine at UNM, and Dr. Tolstrup is a cardiologist at UNM.

References

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2721-2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(6):1431-1433.

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1349-1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163.

- Estrada CA, Rosman HS, Prasad NK, et al. Role of telemetry monitoring in the non-intensive care unit. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(12):960-965.

- Curry JP, Hanson CW III, Russell MW, Hanna C, Devine G, Ochroch EA. The use and effectiveness of electrocardiographic telemetry monitoring in a community hospital general care setting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1483-1487.

- Cleverley K, Mousavi N, Stronger L, et al. The impact of telemetry on survival of in-hospital cardiac arrests in non-critical care patients. Resuscitation. 2013;84(7):878-882. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.038.

- Walkey AJ, Greiner MA, Heckbert SR, et al. Atrial fibrillation among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with sepsis: incidence and risk factors. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):949-955.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.020.

- Pickham D, Helfenbein E, Shinn JA, Chan G, Funk M, Drew BJ. How many patients need QT interval monitoring in critical care units? Preliminary report of the QT in Practice study. J Electrocardiol. 2010;43(6):572-576. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.05.016.

- Cuculi F, Kobza R, Ehmann T, Erne P. ECG changes amongst patients with alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(13-14):223-227. doi:2006/13/smw-11319.

- Fuso L, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, et al. Predicting mortality of patients hospitalized for acutely exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 1995;98(3):272-277.

- Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardiovascular effects of beta-agonists in patients with asthma and COPD: a meta-analysis. Chest. 2004;125(6):2309-2321.

- McCartney PR. Clinical alarm management. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2012;37(3):202. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e31824c5b4a.

- Benjamin EM, Klugman RA, Luckmann R, Fairchild DG, Abookire SA. Impact of cardiac telemetry on patient safety and cost. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):e225-e232.

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1852-1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491.

COPD Exacerbation Prevention: April 2015 CHEST Guidelines

Background

The CHEST guidelines for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) were developed through a collaboration between the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS). They are the first evidence-based guidelines dedicated entirely to the prevention of AECOPD and largely exclude material related to the treatment of symptomatic disease.1

Patients with AECOPD are commonly cared for by hospitalists, so we fill an important role in the longitudinal treatment of this disease. Acute exacerbations and hospitalizations for COPD account for 50% of all COPD-related expenses.2,3 Further, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed a 20% readmission rate nationally for AECOPD, far higher than the rate for most other diagnoses.4 Consequently, COPD readmission has been added to Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for fiscal year 2015.5

Hospitalization, when the patient is a captive audience and many of the necessary resources are available, may be a time to initiate preventative strategies.

Guideline Updates

The guidelines for non-pharmacologic interventions start with vaccination and continue with behavioral modification. They support the use of the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccination, noting that only influenza vaccination has been shown to decrease AECOPD.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for patients with a recent (fewer than four weeks) exacerbation. Several recommendations favor combining social work interventions with education, adding that face-to-face verbal education is superior to written educational materials. Interestingly, smoking cessation interventions received a weak recommendation, based upon lack of literature specifically focusing on the prevention of AECOPD. Despite this recommendation, smoking cessation intervention is strongly encouraged by the authors, given evidence of a marked reduction in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization among smokers with COPD who quit.6 Finally, telemonitoring is not considered to be superior to usual care.

The guidelines concerning inhaled therapies fall into three major drug classes, including short- and long-acting inhaled muscarinic antagonists (anticholinergic agents), short- and long-acting inhaled beta-agonists, and inhaled corticosteroids.

Long-acting medications are generally considered more effective in preventing exacerbations than those that are short acting. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are highlighted for their efficacy, and combination inhaled long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and inhaled corticosteroids are preferred over monotherapy with either agent alone. LAMAs are preferred to inhaled corticosteroids or LABAs when given as monotherapy.

Short-acting agents are rated as inferior at preventing exacerbations compared to their long-acting analogs, but short-acting medications are better than placebo when combined with long-acting agents from other drug classes. Triple drug therapy (inhaled LAMAs, LABAs, and corticosteroids) can be considered based on current evidence.

The final recommendations address the use of oral medications. A potentially practice-changing guideline is the recommendation for long-term use of N-acetylcysteine tablets twice daily for patients who have experienced more than two exacerbations within two years. A more intuitive recommendation in this group is that treating an AECOPD with oral or IV steroids decreases the chance of recurrent exacerbations in the future.

The remaining recommendations include daily macrolide therapy, the phosphodiesterate-4 inhibitor roflumilast for those with chronic bronchitis and a recent exacerbation, and slow-release theophylline for stable disease. These guidelines also point out that statins do not have a role in AECOPD prevention. An expert consensus also recommends carbocysteine for patients who have failed “maximal” therapy.1

Established Guideline Analysis

Prior guidelines that address stable COPD do exist, most notably from Quaseem and colleagues in the 2011 Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM) and the 2015 GOLD guidelines.7,8 The prior guidelines published in AIM offered limited recommendations on the preventative interventions of bronchodilator use, pulmonary rehabilitation, and oxygen use.

The recommendations made in AIM are similar to those in the CHEST guidelines; the lack of breadth in the AIM report reflects new data generated over the last half decade. They include preventing causative exposures (e.g. tobacco, occupational), recommending bronchodilator use (with or without inhaled corticosteroids), possibly using phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PD-4 inhibitors), administering appropriate vaccines, and providing education; however, GOLD does not actually present or rate the evidence associated with those recommendations. GOLD does specifically state that statins have no role in AECOPD prevention, a position that is updated from more recent literature.8,9

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) also includes some references to prevention of AECOPD but has no sections explicitly dedicated to prevention. Of note, the NGC still endorses statin use and does not appear to have incorporated data from newer studies.8,10

Hospitalist Takeaways

Given the high rate of COPD readmissions and its broad impact on morbidity and healthcare costs, measures to prevent COPD exacerbations cannot remain out of scope of care for inpatient physicians. It is important to initiate pulmonary rehab within four weeks of an exacerbation of COPD to prevent future exacerbations. Systems should be put in place to assure that all patients who qualify are vaccinated for influenza and patients who continue to smoke receive cessation counseling.

Today, hospitalists are comfortable with these non-pharmacologic interventions, as well as medications that include inhaled bronchodilators, nebulized medications, macrolide maintenance therapy, and oral steroids; however, other oral medications, such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors, theophylline, and N-acetylcysteine, may be appropriate for select patients, and hospitalists should become more familiar with their utility.11,12,13,14

Finally, it is important to note that both short- and long-acting inhaled muscarinic antagonists have come to the forefront of pharmacologic interventions for COPD exacerbation prevention.

Dr. Lampman, MD, is a hospitalist, consulting provider, and physician leader of the physician advisor program at Duke Regional Hospital in Durham, N.C. Dr. Lovins is a hospitalist, associate chief medical informatics officer, and assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and Duke Regional Hospital.

References

- Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147(4):894-942.

- Miravitlles M, Garcia-Polo C, Domenech A, Villegas G, Conget F, de la Roza C. Clinical outcomes and cost analysis of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung. 2013;191(5):523-530.

- Miravitlles M, Murio C, Guerrero T, Gisbert R; DAFNE Study Group. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1449-1455.

- Elixhauser A, Au DH, Podulka J. Readmissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2008: Statistical Brief #121.In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: 2006.

- Readmissions Reduction Program. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas-Gutiérrez J, Navarro-Artieda R, Ibáñez-Nolla J. The effect of quitting smoking on costs and healthcare utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparison of current smokers versus ex-smokers in routine clinical practice. Lung. 2014;192(4):505-518.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):179-191.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2015. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SK, et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2201-2210.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse. COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In: Pulmonary (acute & chronic). Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Cazzola M, Matera MG. N-acetylcysteine in COPD may be beneficial, but for whom? Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):166-167.

- Turner RD Bothamley. N-acetylcysteine for COPD: the evidence remains inconclusive. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(4):e3.

- Zheng JP, Wen FQ, Bai CX, et al. Twice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):187-194.

- Amazon.com. Amazon Search. 2015 06/1/2015].

Background

The CHEST guidelines for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) were developed through a collaboration between the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS). They are the first evidence-based guidelines dedicated entirely to the prevention of AECOPD and largely exclude material related to the treatment of symptomatic disease.1

Patients with AECOPD are commonly cared for by hospitalists, so we fill an important role in the longitudinal treatment of this disease. Acute exacerbations and hospitalizations for COPD account for 50% of all COPD-related expenses.2,3 Further, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed a 20% readmission rate nationally for AECOPD, far higher than the rate for most other diagnoses.4 Consequently, COPD readmission has been added to Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for fiscal year 2015.5

Hospitalization, when the patient is a captive audience and many of the necessary resources are available, may be a time to initiate preventative strategies.

Guideline Updates

The guidelines for non-pharmacologic interventions start with vaccination and continue with behavioral modification. They support the use of the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccination, noting that only influenza vaccination has been shown to decrease AECOPD.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for patients with a recent (fewer than four weeks) exacerbation. Several recommendations favor combining social work interventions with education, adding that face-to-face verbal education is superior to written educational materials. Interestingly, smoking cessation interventions received a weak recommendation, based upon lack of literature specifically focusing on the prevention of AECOPD. Despite this recommendation, smoking cessation intervention is strongly encouraged by the authors, given evidence of a marked reduction in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization among smokers with COPD who quit.6 Finally, telemonitoring is not considered to be superior to usual care.

The guidelines concerning inhaled therapies fall into three major drug classes, including short- and long-acting inhaled muscarinic antagonists (anticholinergic agents), short- and long-acting inhaled beta-agonists, and inhaled corticosteroids.

Long-acting medications are generally considered more effective in preventing exacerbations than those that are short acting. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are highlighted for their efficacy, and combination inhaled long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and inhaled corticosteroids are preferred over monotherapy with either agent alone. LAMAs are preferred to inhaled corticosteroids or LABAs when given as monotherapy.

Short-acting agents are rated as inferior at preventing exacerbations compared to their long-acting analogs, but short-acting medications are better than placebo when combined with long-acting agents from other drug classes. Triple drug therapy (inhaled LAMAs, LABAs, and corticosteroids) can be considered based on current evidence.

The final recommendations address the use of oral medications. A potentially practice-changing guideline is the recommendation for long-term use of N-acetylcysteine tablets twice daily for patients who have experienced more than two exacerbations within two years. A more intuitive recommendation in this group is that treating an AECOPD with oral or IV steroids decreases the chance of recurrent exacerbations in the future.

The remaining recommendations include daily macrolide therapy, the phosphodiesterate-4 inhibitor roflumilast for those with chronic bronchitis and a recent exacerbation, and slow-release theophylline for stable disease. These guidelines also point out that statins do not have a role in AECOPD prevention. An expert consensus also recommends carbocysteine for patients who have failed “maximal” therapy.1

Established Guideline Analysis

Prior guidelines that address stable COPD do exist, most notably from Quaseem and colleagues in the 2011 Annals of Internal Medicine (AIM) and the 2015 GOLD guidelines.7,8 The prior guidelines published in AIM offered limited recommendations on the preventative interventions of bronchodilator use, pulmonary rehabilitation, and oxygen use.

The recommendations made in AIM are similar to those in the CHEST guidelines; the lack of breadth in the AIM report reflects new data generated over the last half decade. They include preventing causative exposures (e.g. tobacco, occupational), recommending bronchodilator use (with or without inhaled corticosteroids), possibly using phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors (PD-4 inhibitors), administering appropriate vaccines, and providing education; however, GOLD does not actually present or rate the evidence associated with those recommendations. GOLD does specifically state that statins have no role in AECOPD prevention, a position that is updated from more recent literature.8,9

The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) also includes some references to prevention of AECOPD but has no sections explicitly dedicated to prevention. Of note, the NGC still endorses statin use and does not appear to have incorporated data from newer studies.8,10

Hospitalist Takeaways

Given the high rate of COPD readmissions and its broad impact on morbidity and healthcare costs, measures to prevent COPD exacerbations cannot remain out of scope of care for inpatient physicians. It is important to initiate pulmonary rehab within four weeks of an exacerbation of COPD to prevent future exacerbations. Systems should be put in place to assure that all patients who qualify are vaccinated for influenza and patients who continue to smoke receive cessation counseling.

Today, hospitalists are comfortable with these non-pharmacologic interventions, as well as medications that include inhaled bronchodilators, nebulized medications, macrolide maintenance therapy, and oral steroids; however, other oral medications, such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors, theophylline, and N-acetylcysteine, may be appropriate for select patients, and hospitalists should become more familiar with their utility.11,12,13,14

Finally, it is important to note that both short- and long-acting inhaled muscarinic antagonists have come to the forefront of pharmacologic interventions for COPD exacerbation prevention.

Dr. Lampman, MD, is a hospitalist, consulting provider, and physician leader of the physician advisor program at Duke Regional Hospital in Durham, N.C. Dr. Lovins is a hospitalist, associate chief medical informatics officer, and assistant professor of medicine at Duke University and Duke Regional Hospital.

References

- Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147(4):894-942.

- Miravitlles M, Garcia-Polo C, Domenech A, Villegas G, Conget F, de la Roza C. Clinical outcomes and cost analysis of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung. 2013;191(5):523-530.

- Miravitlles M, Murio C, Guerrero T, Gisbert R; DAFNE Study Group. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1449-1455.

- Elixhauser A, Au DH, Podulka J. Readmissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2008: Statistical Brief #121.In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, Md.: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: 2006.

- Readmissions Reduction Program. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Sicras-Mainar A, Rejas-Gutiérrez J, Navarro-Artieda R, Ibáñez-Nolla J. The effect of quitting smoking on costs and healthcare utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparison of current smokers versus ex-smokers in routine clinical practice. Lung. 2014;192(4):505-518.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(3):179-191.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2015. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SK, et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2201-2210.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Guideline Clearinghouse. COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In: Pulmonary (acute & chronic). Accessed September 8, 2015.

- Cazzola M, Matera MG. N-acetylcysteine in COPD may be beneficial, but for whom? Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):166-167.

- Turner RD Bothamley. N-acetylcysteine for COPD: the evidence remains inconclusive. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(4):e3.

- Zheng JP, Wen FQ, Bai CX, et al. Twice daily N-acetylcysteine 600 mg for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (PANTHEON): a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):187-194.

- Amazon.com. Amazon Search. 2015 06/1/2015].

Background

The CHEST guidelines for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) were developed through a collaboration between the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) and the Canadian Thoracic Society (CTS). They are the first evidence-based guidelines dedicated entirely to the prevention of AECOPD and largely exclude material related to the treatment of symptomatic disease.1

Patients with AECOPD are commonly cared for by hospitalists, so we fill an important role in the longitudinal treatment of this disease. Acute exacerbations and hospitalizations for COPD account for 50% of all COPD-related expenses.2,3 Further, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality showed a 20% readmission rate nationally for AECOPD, far higher than the rate for most other diagnoses.4 Consequently, COPD readmission has been added to Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for fiscal year 2015.5

Hospitalization, when the patient is a captive audience and many of the necessary resources are available, may be a time to initiate preventative strategies.

Guideline Updates

The guidelines for non-pharmacologic interventions start with vaccination and continue with behavioral modification. They support the use of the 23-valent polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccination, noting that only influenza vaccination has been shown to decrease AECOPD.

Pulmonary rehabilitation is recommended for patients with a recent (fewer than four weeks) exacerbation. Several recommendations favor combining social work interventions with education, adding that face-to-face verbal education is superior to written educational materials. Interestingly, smoking cessation interventions received a weak recommendation, based upon lack of literature specifically focusing on the prevention of AECOPD. Despite this recommendation, smoking cessation intervention is strongly encouraged by the authors, given evidence of a marked reduction in morbidity, mortality, and healthcare utilization among smokers with COPD who quit.6 Finally, telemonitoring is not considered to be superior to usual care.

The guidelines concerning inhaled therapies fall into three major drug classes, including short- and long-acting inhaled muscarinic antagonists (anticholinergic agents), short- and long-acting inhaled beta-agonists, and inhaled corticosteroids.

Long-acting medications are generally considered more effective in preventing exacerbations than those that are short acting. Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are highlighted for their efficacy, and combination inhaled long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and inhaled corticosteroids are preferred over monotherapy with either agent alone. LAMAs are preferred to inhaled corticosteroids or LABAs when given as monotherapy.

Short-acting agents are rated as inferior at preventing exacerbations compared to their long-acting analogs, but short-acting medications are better than placebo when combined with long-acting agents from other drug classes. Triple drug therapy (inhaled LAMAs, LABAs, and corticosteroids) can be considered based on current evidence.