User login

Clinically Impressive Tophaceous Gout With Significant Bony Destruction

Gout is an in inflammatory condition that is generally characterized by red, hot, swollen, and painful joints. The disease is often associated with increased serum uric acid levels; which are considered elevated when they are > 6 mg/dL in women and > 7 mg/dL in men. When gout affects joints, the subchondral bone may be involved, leading to destructive, painful changes. This article presents the case of a patient diagnosed with tophaceous gout of the left second toe with bony erosive changes and calcified nodules noted on magnetic resonance images (MRI).

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old white male presented to the podiatry clinic for a left second-toe mass that was diagnosed as tophaceous gout after being seen by his primary care physician. The patient reported that the mass had slowly grown over the past 10 years. At presentation, he had a 0.2-cm ulcer on the dorsal aspect of the left second-toe mass. The patient stated that the ulcer had recently appeared with some exudate; however, there was no active drainage of material. The patient had a 20-year history of gout that was untreated with dietary modifications or medication. The patient also stated that although the left second-toe mass did not cause any pain on rest, it did cause pain with shoe gear and during ambulation. A community-based podiatrist had recommended amputation of the second toe and as a result the patient was seeking a second opinion at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Lebanon VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania. The patient had not had acute gouty attacks during the past 10 years.

The patient’s medical history was significant for uncontrolled gout, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease with a 4-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting, impaired fasting glucose, prostate cancer that was in remission, alcohol misuse (currently limited to ≤ 2 drinks per night), and 30-year history of cigarette smoking (quit 2 months prior to visit).1,2

At his first visit to the clinic, an examination revealed distinct evidence of bulging of the soft tissues of the second toe of the left foot with a dry sinus tract that was not malodorous (Figure 1). The left second toe was erythematous and edematous. A local increase in skin temperature was present on the second toe of the left foot compared with that of the contralateral foot and other toes. The dorsalis pedis and tibialis posterior pulses were easily palpated, and the capillary return was within normal limits. Palpation of the left second-toe plantar elicited mild tenderness. Crepitation was not present at the left second metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) nor at the interphalangeal joint. There was restricted range of motion at the left second MPJ compared with that of the right foot and no motion at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The movement at the left second metatarsophalangeal elicited tenderness. The mass on the left second toe was firm, nonpulsatile, oval-shaped, with a white pigmented consistency that measured 2 cm x 2.5 cm.

There were no deficits present on the neurologic examination, which was noncontributory. There also was no gross evidence of motor weakness. His initial temporal temperature was 98.2° F. The initial laboratory findings were uric acid, 9.5 mg/dL; fasting glucose, 117 g/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate, 55 mL/min/1.73 m2; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 6.5 mm/h; and white blood count, 6.6 K/uL.3,4-6

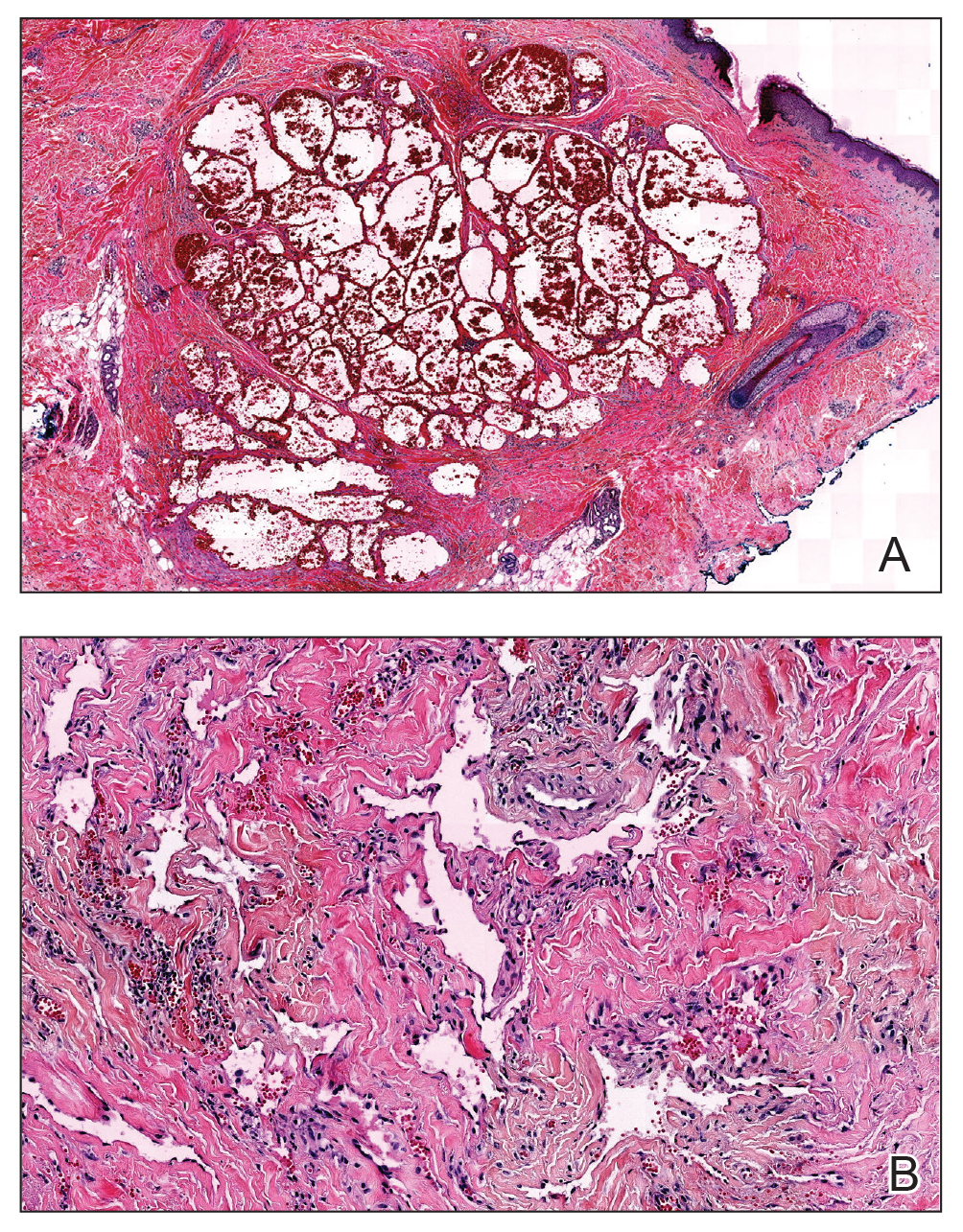

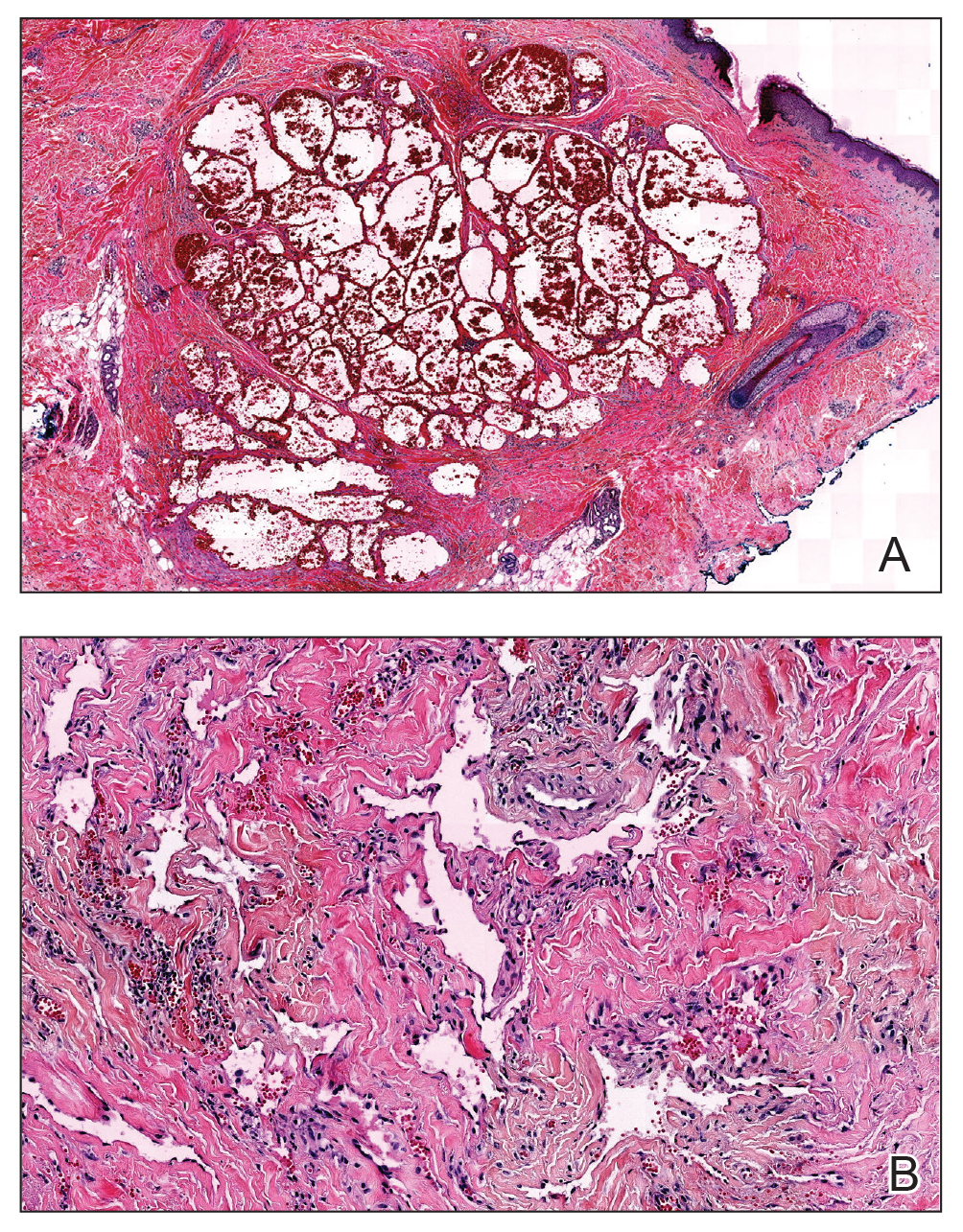

Diagnostic imaging included X-rays of the patient’s feet and a MRI of the left foot. The X-rays showed diffusely osteopenic bones with severe soft tissue swelling surrounding the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also present was moderate soft tissue swelling at the level of the first metatarsophalangeal joint accompanied by extensive erosions at both of these joints, most pronounced at the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also, there was narrowing at the first MPJ and the first interphalangeal joint. Erosive changes at the tarsometatarsal articulations and small lucencies within the navicular/midfoot joint were suggestive of additional gouty erosions. A small-to-moderate posterior calcaneal enthesophyte was present as well as a tiny calcaneal enthesophyte (Figure 2).

A MRI showed a destructive soft tissue mass, resulting in overhanging edges, with foci of calcifications centered about the proximal interphalangeal joint of the second toe, which is consistent with a calcified tophaceous gout nodule. The widest dimension of the mass measured 3.2 cm. There also was a less prominent calcified tophaceous gout nodule at the first MPJ. There were additional small punched-out lesions involving the bases of the first through fourth metatarsi and at the distal aspect of the first cuneiform in keeping with gouty arthropathy (Figure 3).4,7-10

The initial treatment plan presented to the patient was to amputate the left second toe. But the patient decided against amputation. Treatment guidelines for allopurinol are to titrate in 100-mg increments every 2 weeks until the serum uric acid levels are consistently < 6, tophi resolve, and the patient should be free of gout attacks.11 We initiated uric acid-lowering therapy with allopurinol at 50 mg/d for 7 days, increasing to 100 mg/d for 7 days, then to 200 mg/d for 10 days. The patient’s serum uric acid level was checked at 200 mg/d. Our patient could not tolerate the allopurinol and decided to discontinue treatment. After 1 year he started having severe pain and returned to have the toe amputated. The patient healed uneventfully.

Discussion

Tophaceous gout is characterized by collections of solid urate accompanied by chronic inflammatory and often destructive changes in the surrounding tissue brought on by periods of increased uric acid levels. Due to the patient’s 20-year history of untreated tophaceous gout, we saw the extent of bony and soft tissue destruction that this pathology created. This patient’s uric acid laboratory value of 9.5 mg/dL was well above the normal reference values of 2.6 to 7.2 mg/dL. The X-rays performed suggested that there was not only bony destruction, but also deformity.

The destruction to the surrounding soft tissues noted as advanced nonhealing wounds formed to the area of the tophi. The size of the second digit also was impressive, causing displacement of the other digits. As stated in the literature, tophaceous gout is usually painless as was the case in our patient. It is the combination of the relatively painless nature of this pathology accompanied by no treatment over many years that led to the patient’s level of deformity and tissue destruction.

Conclusion

We describe a common presentation of bone involvement secondary to significant tophaceous gout in the absence osteomyelitis. The goal of treatment was to maintain a functional foot free of major deformity, pain, or associated risk factors that could lead to a more significant surgical procedure, such as a proximal amputation.11 Given the destructive nature of this pathology, it is important to educate the patient, perform regular examinations, and start medications early to control uric acid levels. These measures will improve the patient’s prognosis and avoid severe sequelae.

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):155-175.

3. Choi H. Epidemiology of crystal arthropathy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32(2):255-273.

4. Nakayama DA, Barthelemy C, Carrera G, Lightfoot RW Jr, Wortmann RL. Tophaceous gout: a clinical and radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(4):468-471.

5. Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Pathophysiology of crystal-induced arthritis. In: Wortmann RL, Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Ryan LM, eds. Crystal-induced Arthropathies. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006.

6. Dalbeth N, Pool B, Gamble GD, et al. Cellular characterization of the gouty tophus: a quantitative analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1549-1556.

7. Hsu CY, Shih TT, Huang KM, Chen PQ, Sheu JJ, Li YW. Tophaceous gout of the spine: MR imaging features. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(10):919-925.

8. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Edwards NL, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the quantitative assessment of gouty tophi. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(4):408-414.

9. McQueen FM, Doyle A, Dalbeth N. Imaging in the crystal arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):231-249.

10. Choi HK, Al-Arfaj AM, Eftekhari A, et al. Dual energy computed tomography in tophaceous gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1609-1612.

11. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(10):1431-1446.

Gout is an in inflammatory condition that is generally characterized by red, hot, swollen, and painful joints. The disease is often associated with increased serum uric acid levels; which are considered elevated when they are > 6 mg/dL in women and > 7 mg/dL in men. When gout affects joints, the subchondral bone may be involved, leading to destructive, painful changes. This article presents the case of a patient diagnosed with tophaceous gout of the left second toe with bony erosive changes and calcified nodules noted on magnetic resonance images (MRI).

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old white male presented to the podiatry clinic for a left second-toe mass that was diagnosed as tophaceous gout after being seen by his primary care physician. The patient reported that the mass had slowly grown over the past 10 years. At presentation, he had a 0.2-cm ulcer on the dorsal aspect of the left second-toe mass. The patient stated that the ulcer had recently appeared with some exudate; however, there was no active drainage of material. The patient had a 20-year history of gout that was untreated with dietary modifications or medication. The patient also stated that although the left second-toe mass did not cause any pain on rest, it did cause pain with shoe gear and during ambulation. A community-based podiatrist had recommended amputation of the second toe and as a result the patient was seeking a second opinion at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Lebanon VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania. The patient had not had acute gouty attacks during the past 10 years.

The patient’s medical history was significant for uncontrolled gout, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease with a 4-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting, impaired fasting glucose, prostate cancer that was in remission, alcohol misuse (currently limited to ≤ 2 drinks per night), and 30-year history of cigarette smoking (quit 2 months prior to visit).1,2

At his first visit to the clinic, an examination revealed distinct evidence of bulging of the soft tissues of the second toe of the left foot with a dry sinus tract that was not malodorous (Figure 1). The left second toe was erythematous and edematous. A local increase in skin temperature was present on the second toe of the left foot compared with that of the contralateral foot and other toes. The dorsalis pedis and tibialis posterior pulses were easily palpated, and the capillary return was within normal limits. Palpation of the left second-toe plantar elicited mild tenderness. Crepitation was not present at the left second metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) nor at the interphalangeal joint. There was restricted range of motion at the left second MPJ compared with that of the right foot and no motion at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The movement at the left second metatarsophalangeal elicited tenderness. The mass on the left second toe was firm, nonpulsatile, oval-shaped, with a white pigmented consistency that measured 2 cm x 2.5 cm.

There were no deficits present on the neurologic examination, which was noncontributory. There also was no gross evidence of motor weakness. His initial temporal temperature was 98.2° F. The initial laboratory findings were uric acid, 9.5 mg/dL; fasting glucose, 117 g/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate, 55 mL/min/1.73 m2; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 6.5 mm/h; and white blood count, 6.6 K/uL.3,4-6

Diagnostic imaging included X-rays of the patient’s feet and a MRI of the left foot. The X-rays showed diffusely osteopenic bones with severe soft tissue swelling surrounding the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also present was moderate soft tissue swelling at the level of the first metatarsophalangeal joint accompanied by extensive erosions at both of these joints, most pronounced at the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also, there was narrowing at the first MPJ and the first interphalangeal joint. Erosive changes at the tarsometatarsal articulations and small lucencies within the navicular/midfoot joint were suggestive of additional gouty erosions. A small-to-moderate posterior calcaneal enthesophyte was present as well as a tiny calcaneal enthesophyte (Figure 2).

A MRI showed a destructive soft tissue mass, resulting in overhanging edges, with foci of calcifications centered about the proximal interphalangeal joint of the second toe, which is consistent with a calcified tophaceous gout nodule. The widest dimension of the mass measured 3.2 cm. There also was a less prominent calcified tophaceous gout nodule at the first MPJ. There were additional small punched-out lesions involving the bases of the first through fourth metatarsi and at the distal aspect of the first cuneiform in keeping with gouty arthropathy (Figure 3).4,7-10

The initial treatment plan presented to the patient was to amputate the left second toe. But the patient decided against amputation. Treatment guidelines for allopurinol are to titrate in 100-mg increments every 2 weeks until the serum uric acid levels are consistently < 6, tophi resolve, and the patient should be free of gout attacks.11 We initiated uric acid-lowering therapy with allopurinol at 50 mg/d for 7 days, increasing to 100 mg/d for 7 days, then to 200 mg/d for 10 days. The patient’s serum uric acid level was checked at 200 mg/d. Our patient could not tolerate the allopurinol and decided to discontinue treatment. After 1 year he started having severe pain and returned to have the toe amputated. The patient healed uneventfully.

Discussion

Tophaceous gout is characterized by collections of solid urate accompanied by chronic inflammatory and often destructive changes in the surrounding tissue brought on by periods of increased uric acid levels. Due to the patient’s 20-year history of untreated tophaceous gout, we saw the extent of bony and soft tissue destruction that this pathology created. This patient’s uric acid laboratory value of 9.5 mg/dL was well above the normal reference values of 2.6 to 7.2 mg/dL. The X-rays performed suggested that there was not only bony destruction, but also deformity.

The destruction to the surrounding soft tissues noted as advanced nonhealing wounds formed to the area of the tophi. The size of the second digit also was impressive, causing displacement of the other digits. As stated in the literature, tophaceous gout is usually painless as was the case in our patient. It is the combination of the relatively painless nature of this pathology accompanied by no treatment over many years that led to the patient’s level of deformity and tissue destruction.

Conclusion

We describe a common presentation of bone involvement secondary to significant tophaceous gout in the absence osteomyelitis. The goal of treatment was to maintain a functional foot free of major deformity, pain, or associated risk factors that could lead to a more significant surgical procedure, such as a proximal amputation.11 Given the destructive nature of this pathology, it is important to educate the patient, perform regular examinations, and start medications early to control uric acid levels. These measures will improve the patient’s prognosis and avoid severe sequelae.

Gout is an in inflammatory condition that is generally characterized by red, hot, swollen, and painful joints. The disease is often associated with increased serum uric acid levels; which are considered elevated when they are > 6 mg/dL in women and > 7 mg/dL in men. When gout affects joints, the subchondral bone may be involved, leading to destructive, painful changes. This article presents the case of a patient diagnosed with tophaceous gout of the left second toe with bony erosive changes and calcified nodules noted on magnetic resonance images (MRI).

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old white male presented to the podiatry clinic for a left second-toe mass that was diagnosed as tophaceous gout after being seen by his primary care physician. The patient reported that the mass had slowly grown over the past 10 years. At presentation, he had a 0.2-cm ulcer on the dorsal aspect of the left second-toe mass. The patient stated that the ulcer had recently appeared with some exudate; however, there was no active drainage of material. The patient had a 20-year history of gout that was untreated with dietary modifications or medication. The patient also stated that although the left second-toe mass did not cause any pain on rest, it did cause pain with shoe gear and during ambulation. A community-based podiatrist had recommended amputation of the second toe and as a result the patient was seeking a second opinion at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Lebanon VA Medical Center (VAMC) in Pennsylvania. The patient had not had acute gouty attacks during the past 10 years.

The patient’s medical history was significant for uncontrolled gout, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease with a 4-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting, impaired fasting glucose, prostate cancer that was in remission, alcohol misuse (currently limited to ≤ 2 drinks per night), and 30-year history of cigarette smoking (quit 2 months prior to visit).1,2

At his first visit to the clinic, an examination revealed distinct evidence of bulging of the soft tissues of the second toe of the left foot with a dry sinus tract that was not malodorous (Figure 1). The left second toe was erythematous and edematous. A local increase in skin temperature was present on the second toe of the left foot compared with that of the contralateral foot and other toes. The dorsalis pedis and tibialis posterior pulses were easily palpated, and the capillary return was within normal limits. Palpation of the left second-toe plantar elicited mild tenderness. Crepitation was not present at the left second metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ) nor at the interphalangeal joint. There was restricted range of motion at the left second MPJ compared with that of the right foot and no motion at the proximal interphalangeal joint. The movement at the left second metatarsophalangeal elicited tenderness. The mass on the left second toe was firm, nonpulsatile, oval-shaped, with a white pigmented consistency that measured 2 cm x 2.5 cm.

There were no deficits present on the neurologic examination, which was noncontributory. There also was no gross evidence of motor weakness. His initial temporal temperature was 98.2° F. The initial laboratory findings were uric acid, 9.5 mg/dL; fasting glucose, 117 g/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate, 55 mL/min/1.73 m2; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 6.5 mm/h; and white blood count, 6.6 K/uL.3,4-6

Diagnostic imaging included X-rays of the patient’s feet and a MRI of the left foot. The X-rays showed diffusely osteopenic bones with severe soft tissue swelling surrounding the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also present was moderate soft tissue swelling at the level of the first metatarsophalangeal joint accompanied by extensive erosions at both of these joints, most pronounced at the second proximal interphalangeal joint. Also, there was narrowing at the first MPJ and the first interphalangeal joint. Erosive changes at the tarsometatarsal articulations and small lucencies within the navicular/midfoot joint were suggestive of additional gouty erosions. A small-to-moderate posterior calcaneal enthesophyte was present as well as a tiny calcaneal enthesophyte (Figure 2).

A MRI showed a destructive soft tissue mass, resulting in overhanging edges, with foci of calcifications centered about the proximal interphalangeal joint of the second toe, which is consistent with a calcified tophaceous gout nodule. The widest dimension of the mass measured 3.2 cm. There also was a less prominent calcified tophaceous gout nodule at the first MPJ. There were additional small punched-out lesions involving the bases of the first through fourth metatarsi and at the distal aspect of the first cuneiform in keeping with gouty arthropathy (Figure 3).4,7-10

The initial treatment plan presented to the patient was to amputate the left second toe. But the patient decided against amputation. Treatment guidelines for allopurinol are to titrate in 100-mg increments every 2 weeks until the serum uric acid levels are consistently < 6, tophi resolve, and the patient should be free of gout attacks.11 We initiated uric acid-lowering therapy with allopurinol at 50 mg/d for 7 days, increasing to 100 mg/d for 7 days, then to 200 mg/d for 10 days. The patient’s serum uric acid level was checked at 200 mg/d. Our patient could not tolerate the allopurinol and decided to discontinue treatment. After 1 year he started having severe pain and returned to have the toe amputated. The patient healed uneventfully.

Discussion

Tophaceous gout is characterized by collections of solid urate accompanied by chronic inflammatory and often destructive changes in the surrounding tissue brought on by periods of increased uric acid levels. Due to the patient’s 20-year history of untreated tophaceous gout, we saw the extent of bony and soft tissue destruction that this pathology created. This patient’s uric acid laboratory value of 9.5 mg/dL was well above the normal reference values of 2.6 to 7.2 mg/dL. The X-rays performed suggested that there was not only bony destruction, but also deformity.

The destruction to the surrounding soft tissues noted as advanced nonhealing wounds formed to the area of the tophi. The size of the second digit also was impressive, causing displacement of the other digits. As stated in the literature, tophaceous gout is usually painless as was the case in our patient. It is the combination of the relatively painless nature of this pathology accompanied by no treatment over many years that led to the patient’s level of deformity and tissue destruction.

Conclusion

We describe a common presentation of bone involvement secondary to significant tophaceous gout in the absence osteomyelitis. The goal of treatment was to maintain a functional foot free of major deformity, pain, or associated risk factors that could lead to a more significant surgical procedure, such as a proximal amputation.11 Given the destructive nature of this pathology, it is important to educate the patient, perform regular examinations, and start medications early to control uric acid levels. These measures will improve the patient’s prognosis and avoid severe sequelae.

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):155-175.

3. Choi H. Epidemiology of crystal arthropathy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32(2):255-273.

4. Nakayama DA, Barthelemy C, Carrera G, Lightfoot RW Jr, Wortmann RL. Tophaceous gout: a clinical and radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(4):468-471.

5. Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Pathophysiology of crystal-induced arthritis. In: Wortmann RL, Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Ryan LM, eds. Crystal-induced Arthropathies. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006.

6. Dalbeth N, Pool B, Gamble GD, et al. Cellular characterization of the gouty tophus: a quantitative analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1549-1556.

7. Hsu CY, Shih TT, Huang KM, Chen PQ, Sheu JJ, Li YW. Tophaceous gout of the spine: MR imaging features. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(10):919-925.

8. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Edwards NL, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the quantitative assessment of gouty tophi. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(4):408-414.

9. McQueen FM, Doyle A, Dalbeth N. Imaging in the crystal arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):231-249.

10. Choi HK, Al-Arfaj AM, Eftekhari A, et al. Dual energy computed tomography in tophaceous gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1609-1612.

11. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(10):1431-1446.

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):155-175.

3. Choi H. Epidemiology of crystal arthropathy. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2006;32(2):255-273.

4. Nakayama DA, Barthelemy C, Carrera G, Lightfoot RW Jr, Wortmann RL. Tophaceous gout: a clinical and radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(4):468-471.

5. Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Pathophysiology of crystal-induced arthritis. In: Wortmann RL, Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Ryan LM, eds. Crystal-induced Arthropathies. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2006.

6. Dalbeth N, Pool B, Gamble GD, et al. Cellular characterization of the gouty tophus: a quantitative analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1549-1556.

7. Hsu CY, Shih TT, Huang KM, Chen PQ, Sheu JJ, Li YW. Tophaceous gout of the spine: MR imaging features. Clin Radiol. 2002;57(10):919-925.

8. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Edwards NL, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the quantitative assessment of gouty tophi. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(4):408-414.

9. McQueen FM, Doyle A, Dalbeth N. Imaging in the crystal arthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(2):231-249.

10. Choi HK, Al-Arfaj AM, Eftekhari A, et al. Dual energy computed tomography in tophaceous gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1609-1612.

11. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(10):1431-1446.

Partners in Oncology Care: Coordinated Follicular Lymphoma Management (FULL)

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.

As this patient’s laboratory results and physical examination suggested new-onset congestive heart failure, the PCP obtained an echocardiogram, which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35% and global hypokinesis. Because the patient was symptomatic, she was admitted to the hospital to begin guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including IV diuresis.

Discussion

Given the absence of significant risk factors and prior history of coronary artery disease, the most probable cause for this patient’s cardiomyopathy is doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline chemotherapy that can cause nonischemic, dilated cardiomyopathy, particularly when cumulative doses > 400 mg/m2 are administered, or when combined with chest radiation.13 This patient benefited from GDMT for reduced ejection-fraction heart failure (HFrEF). Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes when HFrEF patients are cared for by a multidisciplinary team who focus of volume management as well as uptitration of therapies to target doses.14

Case Example 4

An 80-year-old female was diagnosed with stage III FL but did not require immediate therapy. After developing discomfort due to enlarging lymphadenopathy, she initiated therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP). She presented to her oncologist for consideration of her fifth cycle of R-CVP and reported a burning sensation on the soles of her feet and numbness in her fingertips and toes. On examination, her pulses were intact and there were no signs of infection, reduced blood flow, or edema. The patient demonstrated decreased sensation on monofilament testing. She had no history of DM and a recent HbA1c test was 4.9% An evaluation for other causes of neuropathy, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency was negative. Thus, vincristine therapy was identified as the most likely etiology for her peripheral neuropathy. The oncologist decided to proceed with cycle 5 of chemotherapy but reduced the dose of vincristine by 50%.

Discussion

Vincristine is a microtubule inhibitor used in many chemotherapy regimens and may cause reversible or permanent neuropathy, including autonomic (constipation), sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or motor (foot-drop).15 A nerve conduction study may be indicated as part of the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for painful sensory neuropathy may include pharmacologic therapy (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, capsaicin cream).16 Podiatrists can provide foot care and may provide shoes and inserts if appropriate. Physical therapists may assist with safety and mobility evaluations and can provide therapeutic exercises and assistive devices that improve function and quality of life.17

Conclusion

As cancer becomes more curable and more manageable, patients with cancer and survivors no longer rely exclusively on their oncologists for medical care. This is increasingly prevalent for patients with incurable but indolent cancers that may be present for years to decades, as acute and cumulative toxicities may complicate existing comorbidities. Thus, in this era of increasingly complex cancer therapies, multidisciplinary medical care that involves PCPs, specialists, and allied medical professionals, is essential for providing care that optimizes health and fully addresses patients’ needs.

1. Friedman EL, Chawla N, Morris PT, et al. Assessing the development of multidisciplinary care: experience of the National Cancer Institute community cancer centers program. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e36-e43.

2. Peterson K, Helfand M, Humphrey L, Christensen V, Carson S. Evidence brief: effectiveness of intensive primary care programs. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Intensive-Primary-Care-Supplement.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed April 5, 2019.

3. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Oncology medical home recognition. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/oncology-medical-home. Accessed April 5, 2019.

4. Kahl BS, Yang DT. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127(17):2055-2063.

5. Dulaney C, Wallace AS, Everett AS, Dover L, McDonald A, Kropp L. Defining health across the cancer continuum. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1029.

6. Hopkins J, Mumber MP. Patient navigation through the cancer care continuum: an overview. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(4):150-152.

7. Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1385-1390.

8. McGill M, Blonde L, Juliana CN, et al; Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2017;7:21-27.

9. Horný M, Glover W, Gupte G, Saraswat A, Vimalananda V, Rosenzweig J. Patient navigation to improve diabetes outpatient care at a safety-net hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):759.

10. Reinwald M, Silva JT, Mueller NJ, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Intracellular signaling pathways: tyrosine kinase and mTOR inhibitors). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(suppl 2):S53-S70.

11. Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014;10(3):e142-e145.

12. Morgan KP, Muluneh B, Dean AM, Amerine LB. Impact of an integrated oral chemotherapy program on patient adherence. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24(5):332-336.

13. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869-2879.

14. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784.

15. Mora E, Smith EM, Donohoe C, Hertz DL. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in pediatric cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(11):2416-2430.

16. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–1967

17. Duregon F, Vendramin B, Bullo V, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer patients suffering chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;121:90-100.

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Four case examples illustrate the important role of multidisciplinary medical care for the optimal long-term care of patients with follicular lymphoma.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.

As this patient’s laboratory results and physical examination suggested new-onset congestive heart failure, the PCP obtained an echocardiogram, which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35% and global hypokinesis. Because the patient was symptomatic, she was admitted to the hospital to begin guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including IV diuresis.

Discussion

Given the absence of significant risk factors and prior history of coronary artery disease, the most probable cause for this patient’s cardiomyopathy is doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline chemotherapy that can cause nonischemic, dilated cardiomyopathy, particularly when cumulative doses > 400 mg/m2 are administered, or when combined with chest radiation.13 This patient benefited from GDMT for reduced ejection-fraction heart failure (HFrEF). Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes when HFrEF patients are cared for by a multidisciplinary team who focus of volume management as well as uptitration of therapies to target doses.14

Case Example 4

An 80-year-old female was diagnosed with stage III FL but did not require immediate therapy. After developing discomfort due to enlarging lymphadenopathy, she initiated therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP). She presented to her oncologist for consideration of her fifth cycle of R-CVP and reported a burning sensation on the soles of her feet and numbness in her fingertips and toes. On examination, her pulses were intact and there were no signs of infection, reduced blood flow, or edema. The patient demonstrated decreased sensation on monofilament testing. She had no history of DM and a recent HbA1c test was 4.9% An evaluation for other causes of neuropathy, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency was negative. Thus, vincristine therapy was identified as the most likely etiology for her peripheral neuropathy. The oncologist decided to proceed with cycle 5 of chemotherapy but reduced the dose of vincristine by 50%.

Discussion

Vincristine is a microtubule inhibitor used in many chemotherapy regimens and may cause reversible or permanent neuropathy, including autonomic (constipation), sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or motor (foot-drop).15 A nerve conduction study may be indicated as part of the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for painful sensory neuropathy may include pharmacologic therapy (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, capsaicin cream).16 Podiatrists can provide foot care and may provide shoes and inserts if appropriate. Physical therapists may assist with safety and mobility evaluations and can provide therapeutic exercises and assistive devices that improve function and quality of life.17

Conclusion

As cancer becomes more curable and more manageable, patients with cancer and survivors no longer rely exclusively on their oncologists for medical care. This is increasingly prevalent for patients with incurable but indolent cancers that may be present for years to decades, as acute and cumulative toxicities may complicate existing comorbidities. Thus, in this era of increasingly complex cancer therapies, multidisciplinary medical care that involves PCPs, specialists, and allied medical professionals, is essential for providing care that optimizes health and fully addresses patients’ needs.

Patients benefit from multidisciplinary care that coordinates management of complex medical problems. Traditionally, multidisciplinary cancer care involves oncology specialty providers in fields that include medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology. Multidisciplinary cancer care intends to improve patient outcomes by bringing together different health care providers (HCPs) who are involved in the treatment of patients with cancer. Because new therapies are more effective and allow patients with cancer to live longer, adverse effects (AEs) are more likely to impact patients’ well-being, both while receiving treatment and long after it has completed. Thus, this population may benefit from an expanded approach to multidisciplinary care that includes input from specialty and primary care providers (PCPs), clinical pharmacy specialists (CPS), physical and occupational therapists, and patient navigators and educators.

We present 4 hypothetical cases, based on actual patients, that illustrate opportunities where multidisciplinary care coordination may improve patient experiences. These cases draw on current quality initiatives from the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program, which has focused on improving the quality of multidisciplinary cancer care at selected community centers, and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient-aligned care team (PACT) model, which brings together different health professionals to optimize primary care coordination.1,2 In addition, the National Committee for Quality Assurance has introduced an educational initiative to facilitate implementation of an oncologic medical home.3 This initiative stresses increased multidisciplinary communication, patient-centered care delivery, and reduced fragmentation of care for this population. Despite these guidelines and experiences from other medical specialties, models for integrated cancer care have not been implemented in a prospective fashion within the VHA.

In this article, we focus on opportunities to take collaborative care approaches for the treatment of patients with follicular lymphoma (FL): a common, incurable, and often indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4 FL was selected because these patients may be treated numerous times and long-term sequalae can accumulate throughout their cancer continuum (a series of health events encompassing cancer screening, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, relapse, and death).5 HCPs in distinct roles can assist patients with cancer in optimizing their health outcomes and overall wellbeing.6

Case Example 1

A 70-year-old male was diagnosed with stage IV FL. Because of his advanced disease, he began therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone). Prednisone was administered at 100 mg daily on the first 5 days of each 21-day cycle. On day 4 of the first treatment cycle, the patient notified his oncologist that he had been very thirsty and his random blood sugar values on 2 different days were 283 mg/dL and 312 mg/dL. A laboratory review revealed his hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) 7 months prior was 5.6%.

Discussion

The high-dose prednisone component of this and other lymphoma therapy regimens can worsen diabetes mellitus (DM) control and/or worsen prediabetes. Patient characteristics that increase the risk of developing glucocorticoid-induced DM after CHOP chemotherapy include age ≥ 60 years, HbA1c > 6.1%, and body mass index > 30.7 This patient did not have DM prior to the FL therapy initiation, but afterwards he met diagnostic criteria for DM. For completeness, other causes for elevated blood glucose should be ruled out (ie, infection, laboratory error, etc.). An oncologist often will triage acute hyperglycemia, treating immediately with IV fluids and/or insulin. Thereafter, ongoing chronic disease management for DM may be best managed by PCPs, certified DM educators, and registered dieticians.

Several programs involving multidisciplinary DM care, comprised of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, certified DM educators, and/or pharmacists have been shown to improve HbA1c, cardiovascular outcomes, and all-cause mortality, while reducing health care costs.8 In addition, patient navigators can assist patients with coordinating visits to disease-state specialists and identifying further educational needs. For example, in 1 program, nonclinical peer navigators were shown to improve the number of appointments attended and reduce HbA1c in a population of patients with DM who were primarily minority, urban, and of low socioeconomic status.9 Thus, integrating DM care shows potential to improve outcomes for patients with lymphoma who develop glucocorticoid

Case Example 2

A 75-year-old male was diagnosed with FL. He was treated initially with bendamustine and rituximab. He required reinitiation of therapy 20 months later when he developed lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and night sweats and began treatment with oral idelalisib, a second-line therapy. Later, the patient presented to his PCP for a routine visit, and on medication reconciliation review, the patient reported regular use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Discussion

Upon consultation with the CPS and the patient’s oncologist, the PCP confirmed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be continued during therapy and for about 6 months following completion of therapy. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is used for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii (formerly Pneumocystis carinii). While use of prophylactic therapy is not necessary for all patients with FL, idelalisib impairs the function of circulating lymphoid B-cells and thus has been associated with an increased risk of serious infection.10 A CPS can provide insight that maximizes medication adherence and efficacy while minimizing food-drug, drug-drug interactions, and AEs. CPS have been shown to: improve adherence to oral therapies, increase prospective monitoring required for safe therapy dose selection, and document assessment of chemotherapy-related AEs.11,12 Thus, multidisciplinary, integrated care is an important component of providing quality oncology care.

Case Example 3

A 60-year-old female presented to her PCP with a 2-week history of shortness of breath and leg swelling. She was treated for FL 4 years previously with 6 cycles of R-CHOP. She reported no chest pain and did not have a prior history of hypertension, DM, or heart disease. On physical exam, she had elevated jugular venous pressure to jaw at 45°, bilateral pulmonary rales, and 2+ pitting pretibial edema. Laboratory tests that included complete blood count, basic chemistries, and thyroid stimulating hormone were unremarkable, though brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 425 pg/mL.

As this patient’s laboratory results and physical examination suggested new-onset congestive heart failure, the PCP obtained an echocardiogram, which demonstrated an ejection fraction of 35% and global hypokinesis. Because the patient was symptomatic, she was admitted to the hospital to begin guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) including IV diuresis.

Discussion

Given the absence of significant risk factors and prior history of coronary artery disease, the most probable cause for this patient’s cardiomyopathy is doxorubicin. Doxorubicin is an anthracycline chemotherapy that can cause nonischemic, dilated cardiomyopathy, particularly when cumulative doses > 400 mg/m2 are administered, or when combined with chest radiation.13 This patient benefited from GDMT for reduced ejection-fraction heart failure (HFrEF). Studies have demonstrated positive outcomes when HFrEF patients are cared for by a multidisciplinary team who focus of volume management as well as uptitration of therapies to target doses.14

Case Example 4

An 80-year-old female was diagnosed with stage III FL but did not require immediate therapy. After developing discomfort due to enlarging lymphadenopathy, she initiated therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CVP). She presented to her oncologist for consideration of her fifth cycle of R-CVP and reported a burning sensation on the soles of her feet and numbness in her fingertips and toes. On examination, her pulses were intact and there were no signs of infection, reduced blood flow, or edema. The patient demonstrated decreased sensation on monofilament testing. She had no history of DM and a recent HbA1c test was 4.9% An evaluation for other causes of neuropathy, such as hypothyroidism and vitamin B12 deficiency was negative. Thus, vincristine therapy was identified as the most likely etiology for her peripheral neuropathy. The oncologist decided to proceed with cycle 5 of chemotherapy but reduced the dose of vincristine by 50%.

Discussion

Vincristine is a microtubule inhibitor used in many chemotherapy regimens and may cause reversible or permanent neuropathy, including autonomic (constipation), sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or motor (foot-drop).15 A nerve conduction study may be indicated as part of the diagnostic evaluation. Treatment for painful sensory neuropathy may include pharmacologic therapy (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, capsaicin cream).16 Podiatrists can provide foot care and may provide shoes and inserts if appropriate. Physical therapists may assist with safety and mobility evaluations and can provide therapeutic exercises and assistive devices that improve function and quality of life.17

Conclusion

As cancer becomes more curable and more manageable, patients with cancer and survivors no longer rely exclusively on their oncologists for medical care. This is increasingly prevalent for patients with incurable but indolent cancers that may be present for years to decades, as acute and cumulative toxicities may complicate existing comorbidities. Thus, in this era of increasingly complex cancer therapies, multidisciplinary medical care that involves PCPs, specialists, and allied medical professionals, is essential for providing care that optimizes health and fully addresses patients’ needs.

1. Friedman EL, Chawla N, Morris PT, et al. Assessing the development of multidisciplinary care: experience of the National Cancer Institute community cancer centers program. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e36-e43.

2. Peterson K, Helfand M, Humphrey L, Christensen V, Carson S. Evidence brief: effectiveness of intensive primary care programs. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Intensive-Primary-Care-Supplement.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed April 5, 2019.

3. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Oncology medical home recognition. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/oncology-medical-home. Accessed April 5, 2019.

4. Kahl BS, Yang DT. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127(17):2055-2063.

5. Dulaney C, Wallace AS, Everett AS, Dover L, McDonald A, Kropp L. Defining health across the cancer continuum. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1029.

6. Hopkins J, Mumber MP. Patient navigation through the cancer care continuum: an overview. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(4):150-152.

7. Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1385-1390.

8. McGill M, Blonde L, Juliana CN, et al; Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2017;7:21-27.

9. Horný M, Glover W, Gupte G, Saraswat A, Vimalananda V, Rosenzweig J. Patient navigation to improve diabetes outpatient care at a safety-net hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):759.

10. Reinwald M, Silva JT, Mueller NJ, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Intracellular signaling pathways: tyrosine kinase and mTOR inhibitors). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(suppl 2):S53-S70.

11. Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014;10(3):e142-e145.

12. Morgan KP, Muluneh B, Dean AM, Amerine LB. Impact of an integrated oral chemotherapy program on patient adherence. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24(5):332-336.

13. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869-2879.

14. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784.

15. Mora E, Smith EM, Donohoe C, Hertz DL. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in pediatric cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(11):2416-2430.

16. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–1967

17. Duregon F, Vendramin B, Bullo V, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer patients suffering chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;121:90-100.

1. Friedman EL, Chawla N, Morris PT, et al. Assessing the development of multidisciplinary care: experience of the National Cancer Institute community cancer centers program. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e36-e43.

2. Peterson K, Helfand M, Humphrey L, Christensen V, Carson S. Evidence brief: effectiveness of intensive primary care programs. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/Intensive-Primary-Care-Supplement.pdf. Published February 2013. Accessed April 5, 2019.

3. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Oncology medical home recognition. https://www.ncqa.org/programs/health-care-providers-practices/oncology-medical-home. Accessed April 5, 2019.

4. Kahl BS, Yang DT. Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127(17):2055-2063.

5. Dulaney C, Wallace AS, Everett AS, Dover L, McDonald A, Kropp L. Defining health across the cancer continuum. Cureus. 2017;9(2):e1029.

6. Hopkins J, Mumber MP. Patient navigation through the cancer care continuum: an overview. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(4):150-152.

7. Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(5):1385-1390.

8. McGill M, Blonde L, Juliana CN, et al; Global Partnership for Effective Diabetes Management. The interdisciplinary team in type 2 diabetes management: challenges and best practice solutions from real-world scenarios. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2017;7:21-27.

9. Horný M, Glover W, Gupte G, Saraswat A, Vimalananda V, Rosenzweig J. Patient navigation to improve diabetes outpatient care at a safety-net hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):759.

10. Reinwald M, Silva JT, Mueller NJ, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Intracellular signaling pathways: tyrosine kinase and mTOR inhibitors). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(suppl 2):S53-S70.

11. Holle LM, Boehnke Michaud L. Oncology pharmacists in health care delivery: vital members of the cancer care team. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014;10(3):e142-e145.

12. Morgan KP, Muluneh B, Dean AM, Amerine LB. Impact of an integrated oral chemotherapy program on patient adherence. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2018;24(5):332-336.

13. Swain SM, Whaley FS, Ewer MS. Congestive heart failure in patients treated with doxorubicin: a retrospective analysis of three trials. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2869-2879.

14. Feltner C, Jones CD, Cené CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(11):774-784.

15. Mora E, Smith EM, Donohoe C, Hertz DL. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in pediatric cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(11):2416-2430.

16. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(18):1941–1967

17. Duregon F, Vendramin B, Bullo V, et al. Effects of exercise on cancer patients suffering chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy undergoing treatment: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;121:90-100.

Multiple Atypical Vascular Lesions Following Breast-Conserving Surgery and Radiation

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) are rare flesh-colored, erythematous, or violaceous macules, patches, papules, or plaques that may occur following adjuvant radiation in breast cancer patients who have undergone conservative lumpectomy.1,2 They range in size from 1 mm to 6 cm and are most often confined to the radiation field. Presentation occurs 1 to 20 years following radiation, though the lesions most often present within 5 years.1,2 Although generally considered benign, 2 of 29 cases of AVLs progressed to angiosarcoma over a 5-year follow-up period in a retrospective clinicopathologic study.1

Atypical vascular lesions show considerable histologic and clinical overlap with radiation-induced angiosarcomas (RIAs), making differentiation between the two challenging.3,4 Mentzel et al5 compared benign, atypical, and malignant postradiation vascular lesions with nonradiation-associated angiosarcomas and found that RIAs were highly variable histopathologically, ranging from well differentiated to poorly differentiated, with atypia ranging from mild to severe. Radiation-induced angiosarcomas could be distinguished from AVLs and nonradiation-associated angiosarcomas by their oncogene amplification and protein expression profiles. Most strikingly, they found amplification of the MYC oncogene by fluorescence in situ hybridization in the nucleus of almost all the RIA cells, which was not seen in AVLs or nonradiation-associated angiosarcomas. Similarly, they found positive nuclear staining for MYC protein by immunohistochemistry in the nucleus of almost all cases of RIA but not in AVL or nonradiation-associated angiosarcomas, making MYC staining a useful diagnostic marker.5 In contrast, a study by Patton et al1 concluded that AVLs demonstrate morphologic patterns and clinical outcomes that suggest they are precursors of angiosarcoma rather than just markers of risk.

Atypical vascular lesions and RIAs usually follow a total radiation dose of 40 to 50 Gy, but RIAs typically are diagnosed later (approximately 10 years following exposure).6,7 Although RIAs are rare, they are known to be aggressive and often high grade, with a median survival of less than 5 years.6,7 Survival is poor even with radical surgical treatment.8 We present a patient with at least 29 AVLs following breast-conserving surgery and radiation and suggest the need for increased awareness of the elevated risk for RIA in patients with numerous benign AVLs.

Case Report

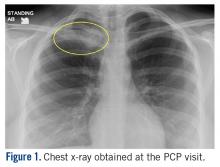

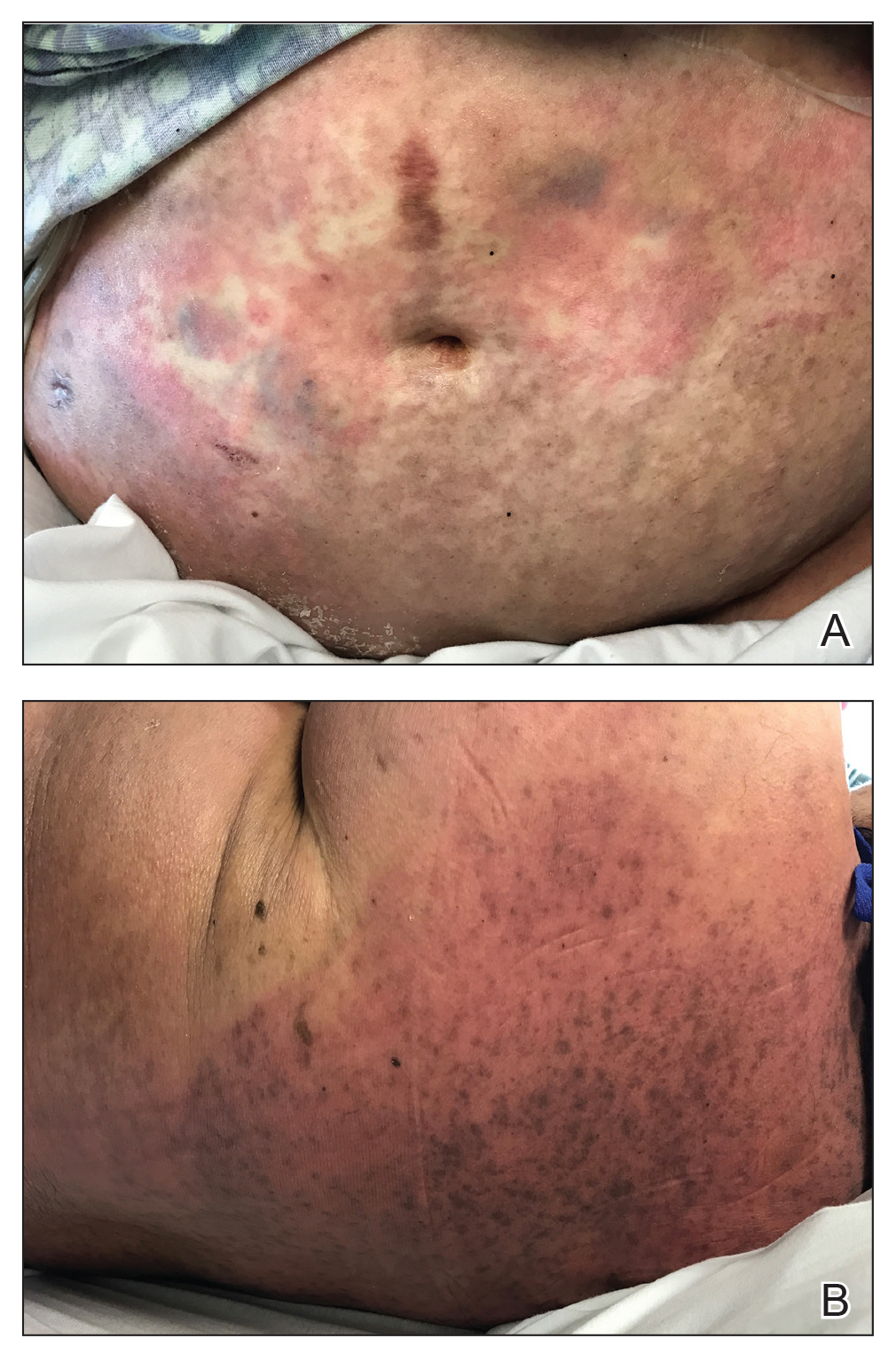

A 43-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer who underwent breast-conserving lumpectomy and adjuvant radiation presented to dermatology upon referral from surgical oncology for multiple lesions on the right breast (Figure 1). Seven years prior to presentation she was diagnosed with grade 3 poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma with lobular features in the right breast that was positive for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 but negative for estrogen or progesterone receptors. She was given neoadjuvant treatment with trastuzumab, docetaxel, and carboplatin prior to conservation lumpectomy with adjuvant radiation. She received a total dose of 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions of 1.8 Gy each over 1 month, with a final boost of 10 Gy in 5 fractions of 2 Gy, each with local skin irritation as the only concern posttreatment.

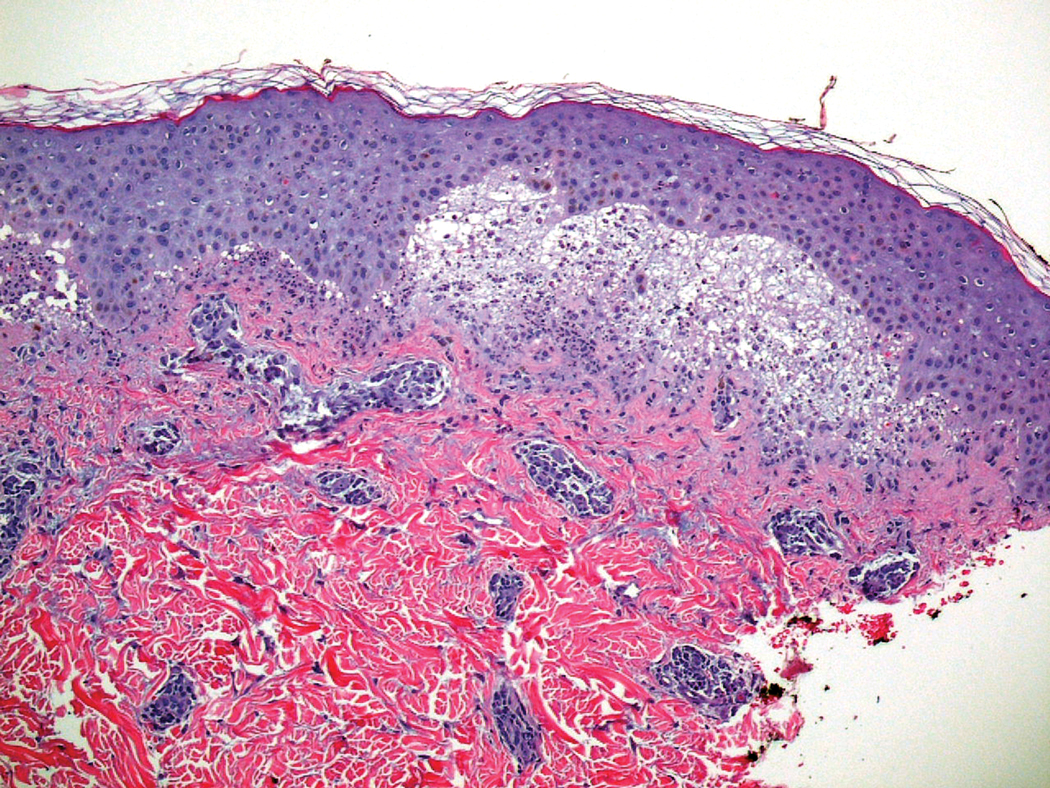

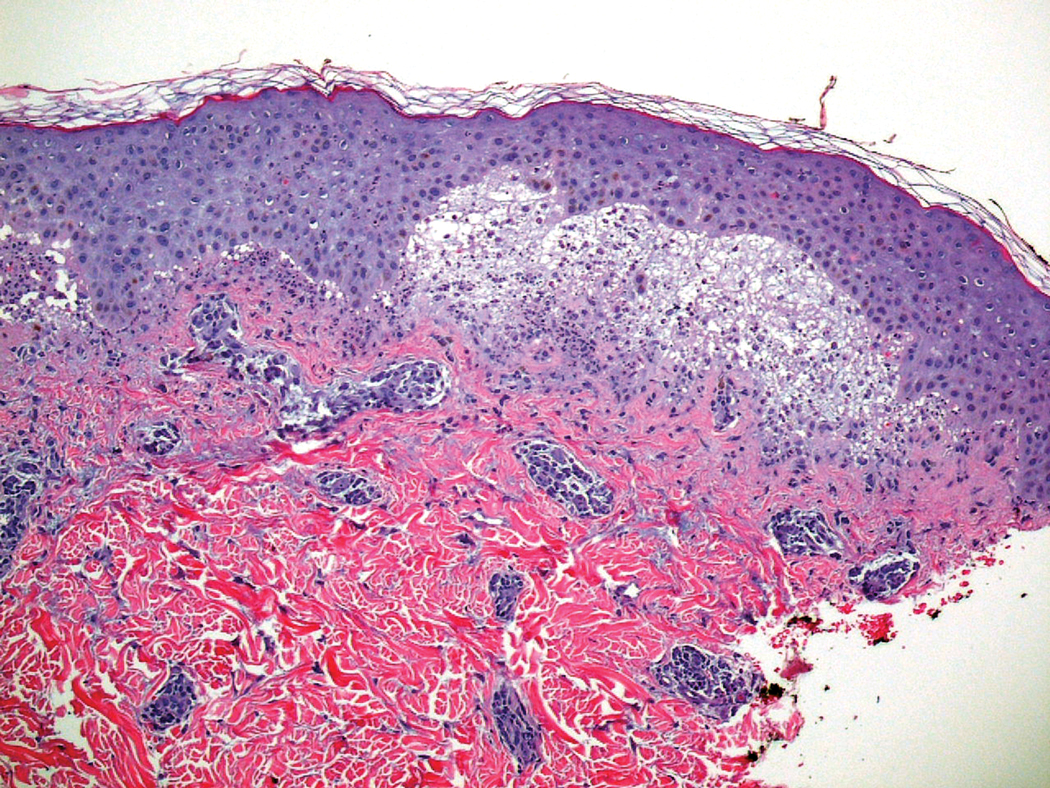

She initially presented to dermatology approximately 3 years after radiotherapy (5 years prior to current presentation) with lesions on the breast that had been present for 6 to 9 months. Physical examination showed 2 firm, painless, 4- to 5-mm papules on the right upper breast. The patient was reassured that the lesions were not suspicious for malignancy; however, 3 years later she presented to surgical oncology with 8 bluish papules or macules (all approximately 4 mm in diameter) on the right breast. These lesions were biopsied and examined by 2 institutions. Pathology of the initial punch biopsy favored a diagnosis of AVLs, though the possibility of RIA could not be ruled out without a complete excisional biopsy. Two excisional biopsies a month later were again consistent with AVLs. In all cases, the lesions were negative for MYC protein. The patient was again reassured but referred to dermatology for a second opinion.

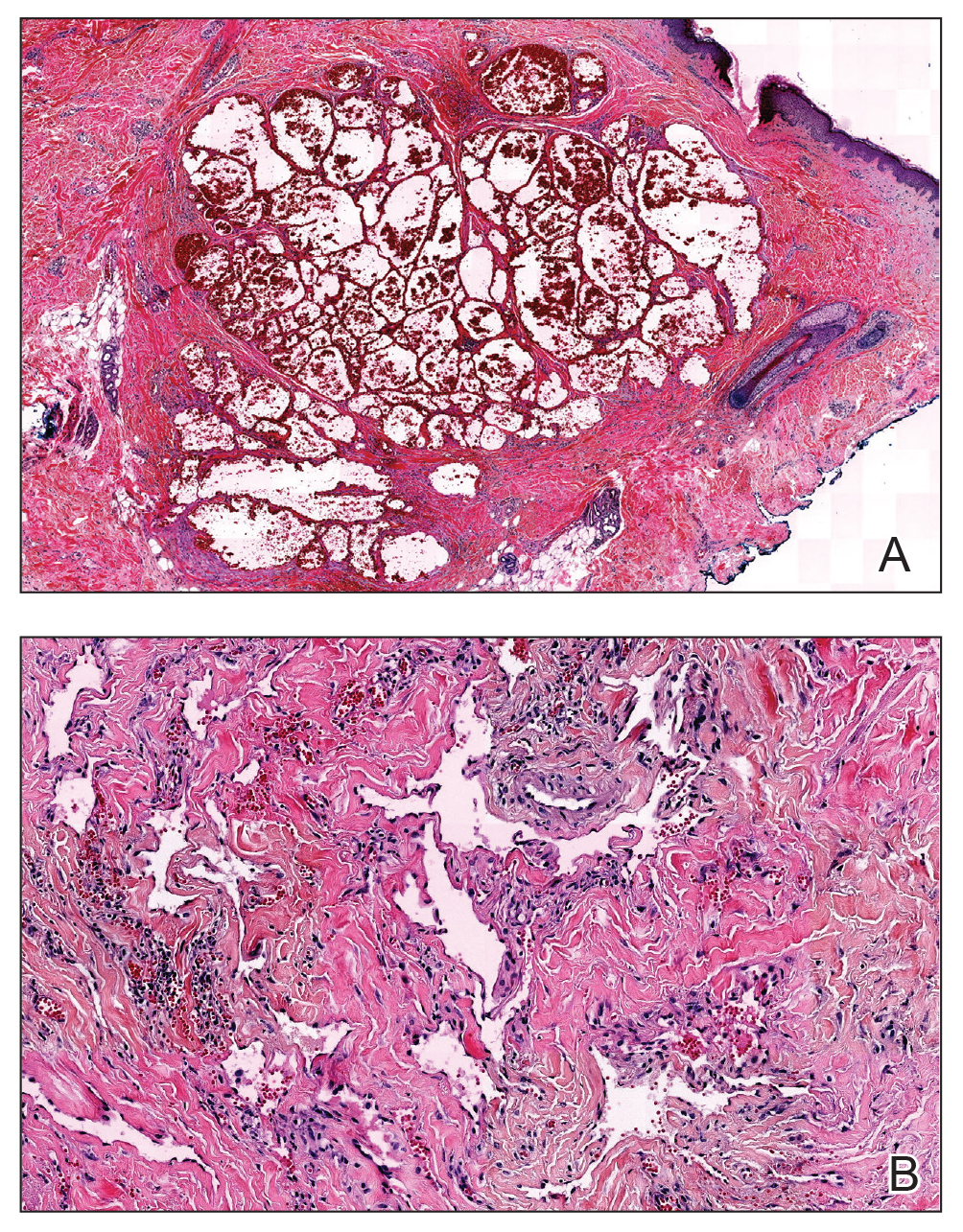

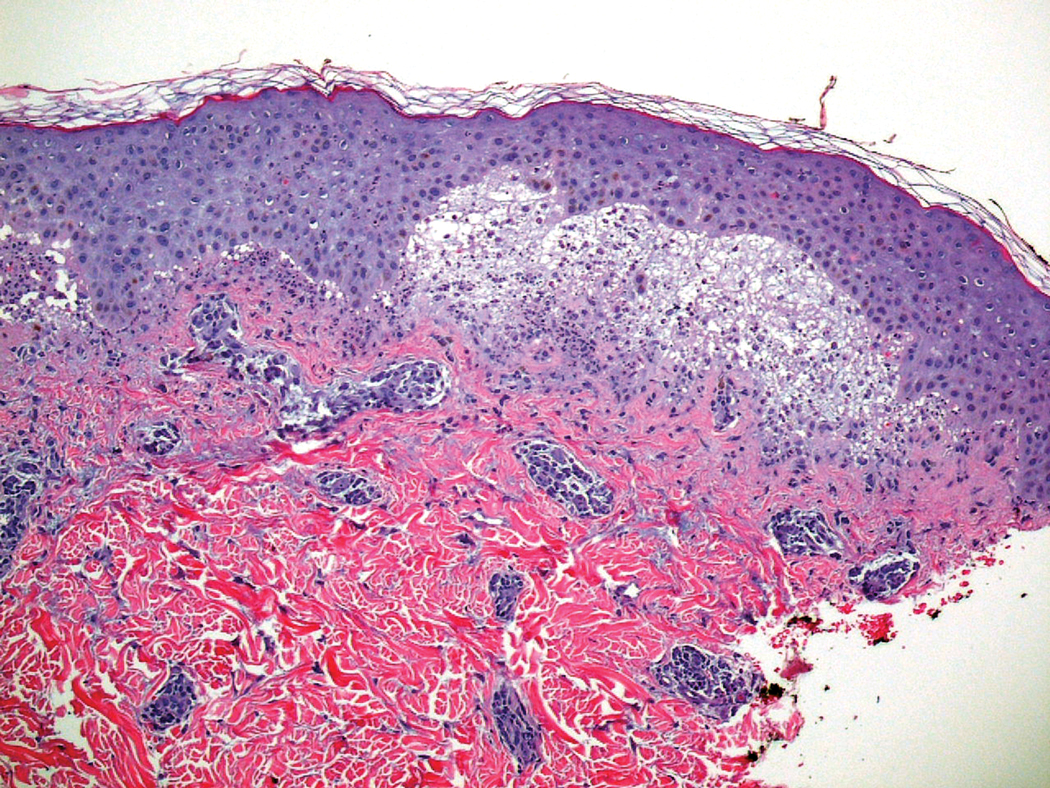

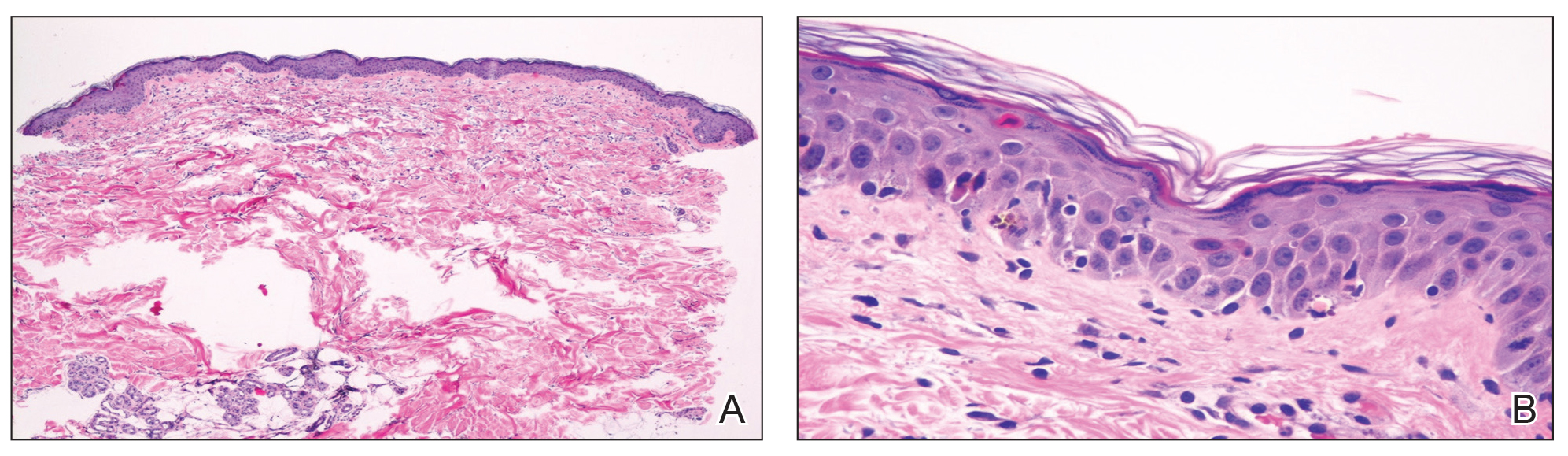

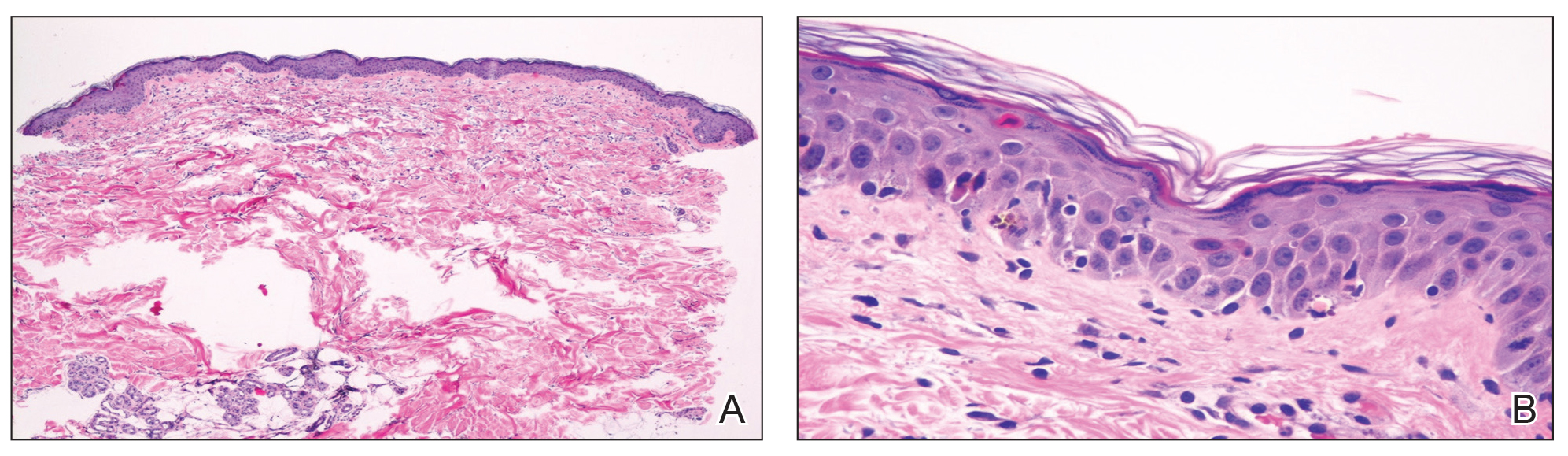

At the current presentation, physical examination showed at least 29 subcutaneous nodules on the right breast ranging in color from pink to deep blue to flesh colored with others more superficially hyperpigmented, possibly secondary to prior biopsy, and measuring 2 to 8 mm in diameter. Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens showed a vascular proliferation extending from the dermis into the subcutaneous tissue comprised of dilated and cavernous vascular channels lined by a single layer of endothelial cells with minimal cytologic atypia (Figure 2). There were focal areas of anastomosing slitlike vascular spaces dissecting dermal collagen. No features of malignancy, such as nuclear crowding, multilayering, or increased mitotic activity, were evident. Immunohistochemical studies for MYC protein were negative. The overall morphologic features and immunoprofile were felt to be most consistent with postradiation AVLs.

At the time, surgical oncology felt that the risk of radical mastectomy outweighed the risk of angiosarcoma due to the absence of frank angiosarcoma and the patient’s notable comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and smoking; however, after reviewing the literature and considering the difficulty of following such a large number of lesions, the dermatology team brought the patient’s case to the multidisciplinary cutaneous tumor board at the University of Massachusetts (Worcester, Massachusetts). In consensus, the tumor board recommended radical mastectomy despite the comorbidities, given her young age and the potential risk for malignant transformation of any one of the numerous AVLs to angiosarcoma.

Postmastectomy pathology showed multiple scattered foci of AVLs ranging from 1.5 to 4 mm in the dermis, similar to those seen on prior biopsies, with no frank evidence of RIA. At 3-year follow-up, the patient has had no recurrence of AVLs or findings suggestive of RIA. There were no reported complications.

Comment

Conservative breast cancer surgery and radiotherapy are becoming more prevalent for breast cancer treatment, thus the number of patients likely to present with AVLs has increased. These patients are at risk for transformation to RIAs.6 It is important for clinicians to be aware of the diagnosis of both AVLs and RIAs and their management given their more frequent presentation. In most cases, one or a few AVLs are present, and excision is the treatment of choice. In a retrospective study by Brenn and Fletcher3 examining 16 patients with AVLs and 26 patients with RIA, the majority of cases of AVL had a single lesion and the maximum number of AVLs was 4. One patient in their study had 30 AVLs (each 3–4 mm in diameter), and she was diagnosed with RIA.3 Our patient—with at least 29 identifiable AVL lesions—was felt to be at considerable risk for developing RIA, as the only other case reported with this many AVLs developed RIA.1 Given the large number of lesions, it was neither feasible to excise each one individually nor monitor all of them for malignant transformation.

Our case demonstrates the important role dermatologists may play in orchestrating care by a multispecialty team including oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, and plastic surgery. In our patient, a close examination of the literature by the dermatology team led to recognition of the potentially elevated risk for malignant transformation. The dermatology team also brought the case for review at the tumor board.

Although future studies are required to determine the relationship between AVL burden and the risk for progression to RIA, it is clear that a multidisciplinary approach and careful consideration of the current literature can prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality for patients with this increasingly common problem.

- Patton KT, Deyrup AT, Weiss SW. Atypical vascular lesions after surgery and radiation of the breast: a clinicopathologic study of 32 cases analyzing histologic heterogeneity and association with angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:943-950.

- Mandrell J, Mehta S, McClure S. Atypical vascular lesion of the breast. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:337-340.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Losch A, Chilek KD, Zirwas MJ. Post-radiation atypical vascular proliferation mimicking angiosarcoma eight months following breast-conserving therapy for breast carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:47-48.

- Mentzel T, Schildhaus HU, Palmedo G, et al. Postradiation cutaneous angiosarcoma after treatment of breast carcinoma is characterized by MYC amplification in contrast to atypical vascular lesions after radiotherapy and control cases: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 66 cases. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:75-85.

- Tahir M, Hendry P, Baird L, et al. Radiation induced angiosarcoma a sequela of radiotherapy for breast cancer following conservative surgery. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:26.

- Hillenbrand T, Menge F, Hohenberger P, et al. Primary and secondary angiosarcomas: a comparative single-center analysis. Clin Sarcoma Res. 2015;5:14.

- Seinen JM, Styring E, Verstappen V, et al. Radiation-associated angiosarcoma after breast cancer: high recurrence rate and poor survival despite surgical treatment with R0 resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2700-2706.

Atypical vascular lesions (AVLs) are rare flesh-colored, erythematous, or violaceous macules, patches, papules, or plaques that may occur following adjuvant radiation in breast cancer patients who have undergone conservative lumpectomy.1,2 They range in size from 1 mm to 6 cm and are most often confined to the radiation field. Presentation occurs 1 to 20 years following radiation, though the lesions most often present within 5 years.1,2 Although generally considered benign, 2 of 29 cases of AVLs progressed to angiosarcoma over a 5-year follow-up period in a retrospective clinicopathologic study.1