User login

Acroangiodermatitis of Mali and Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

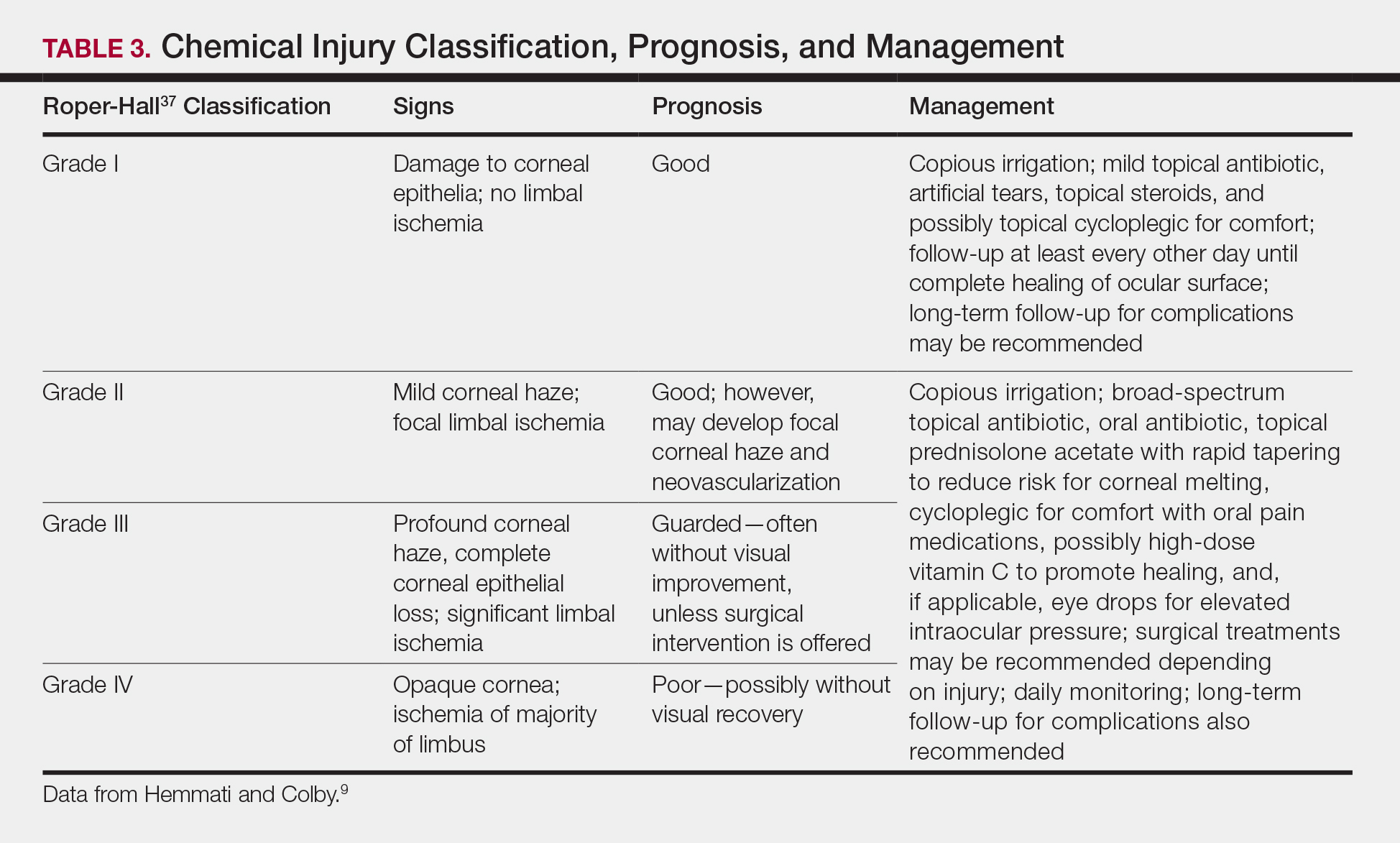

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

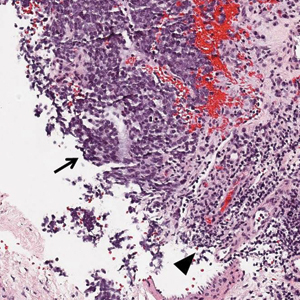

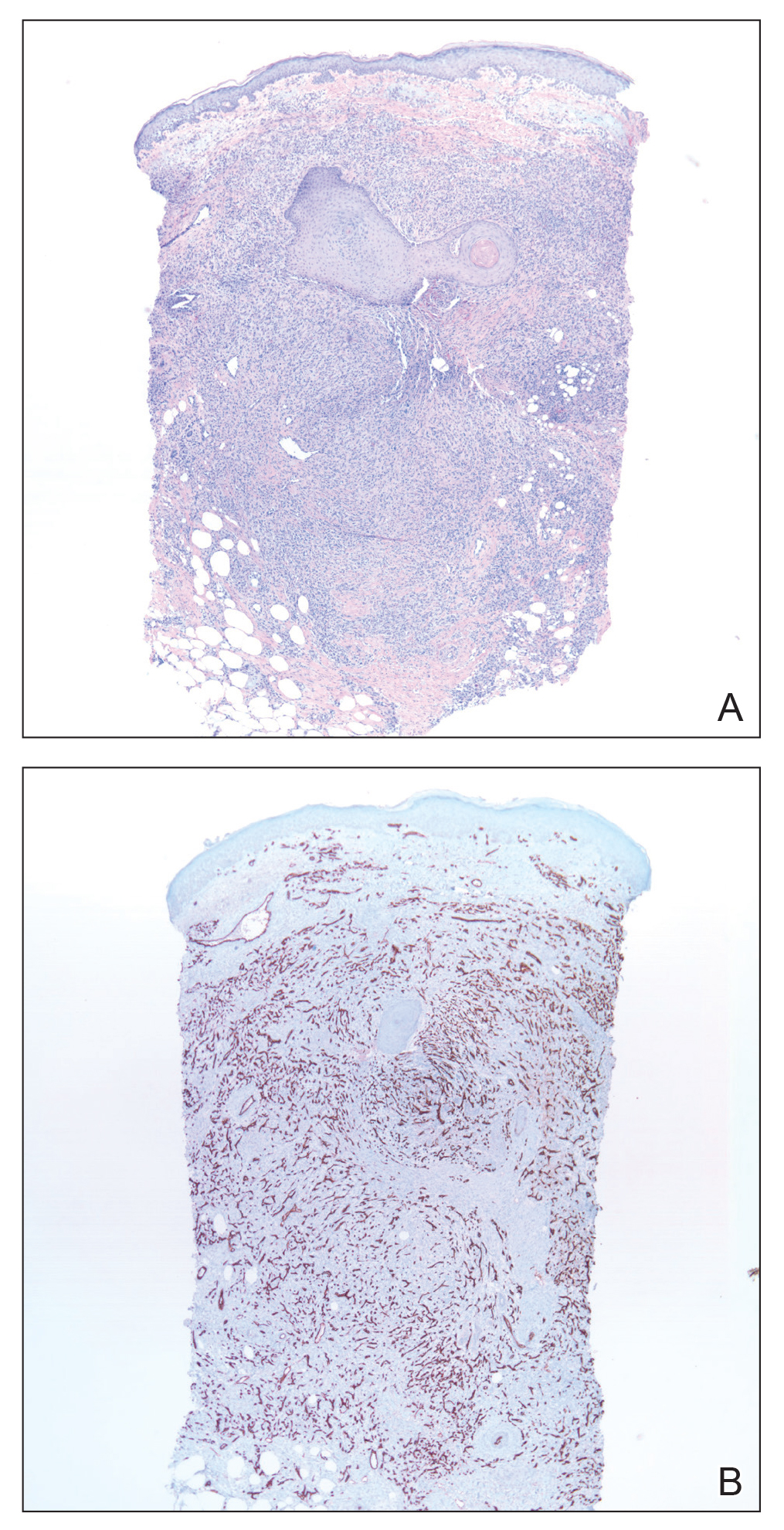

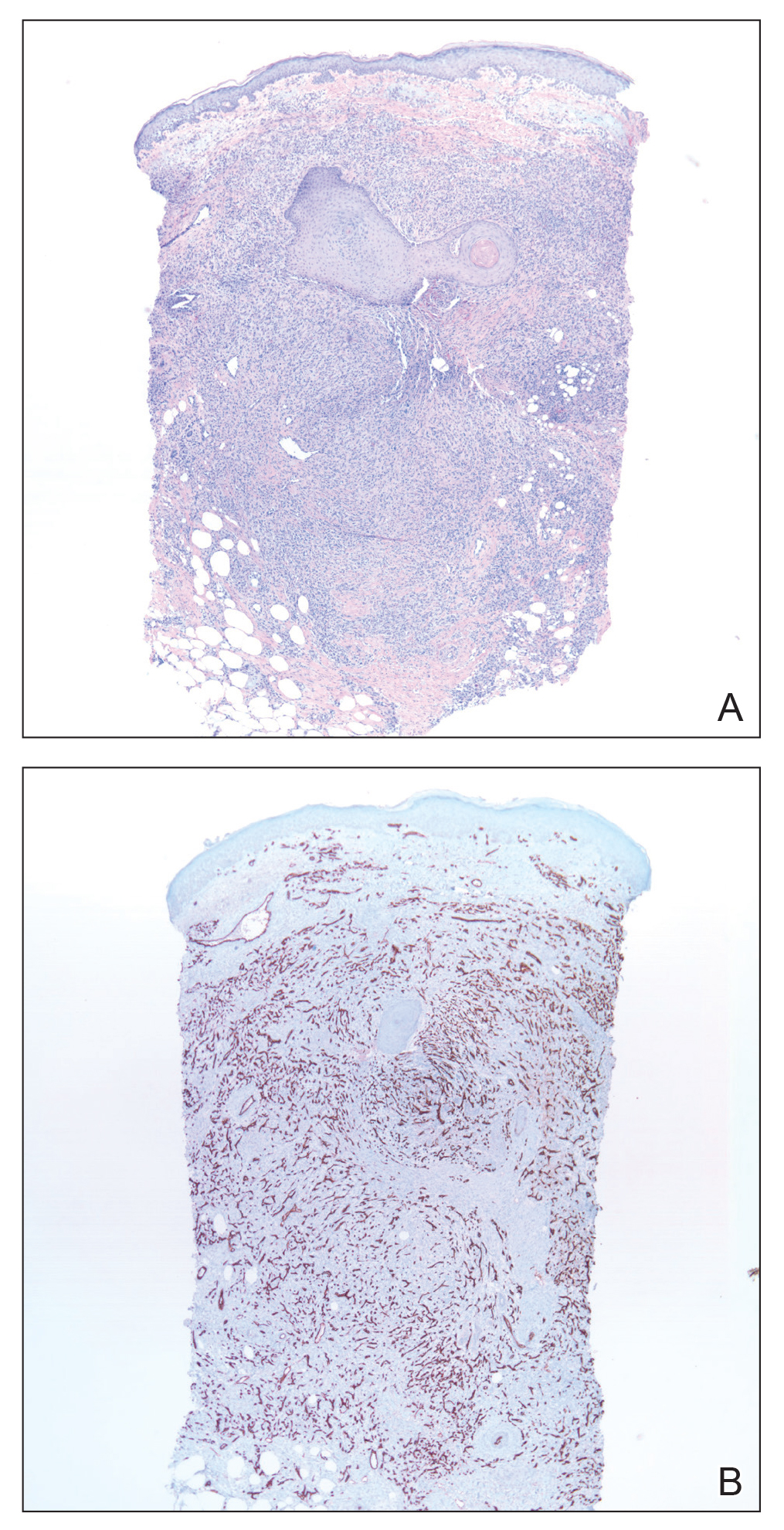

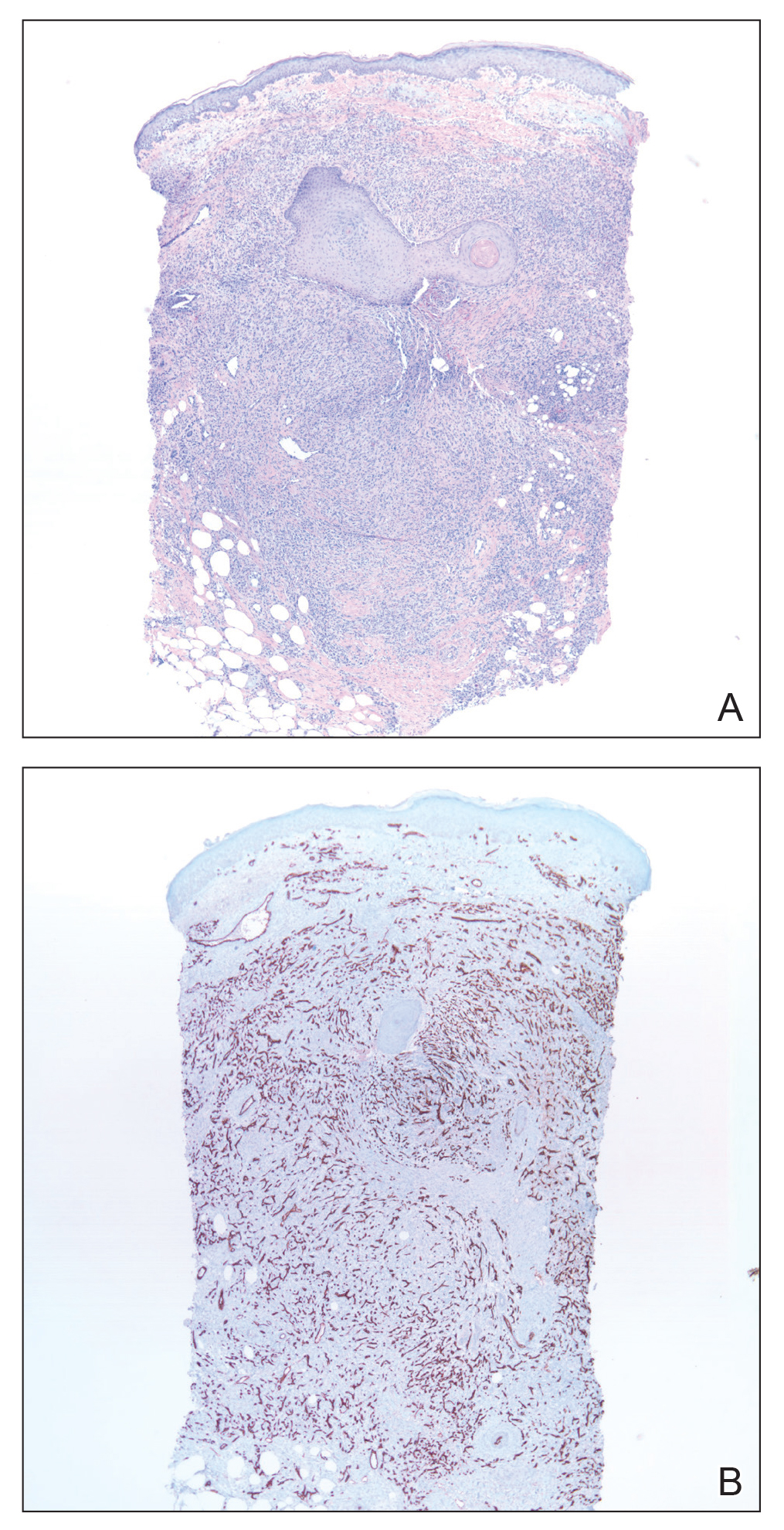

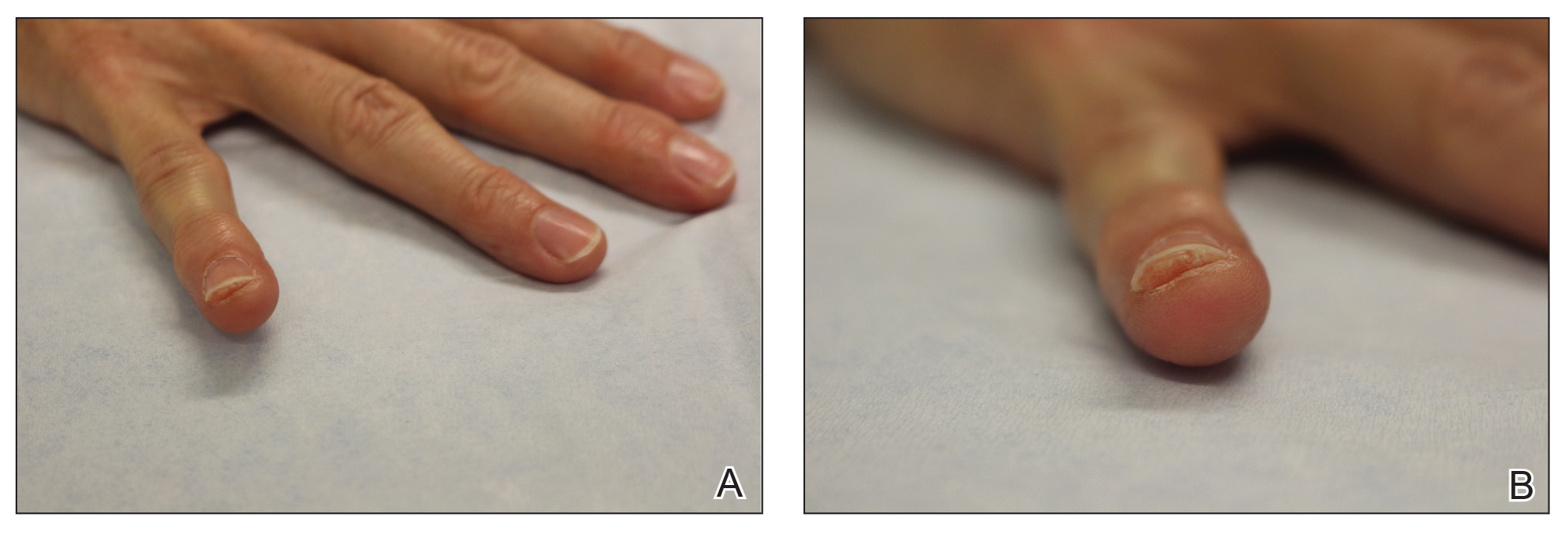

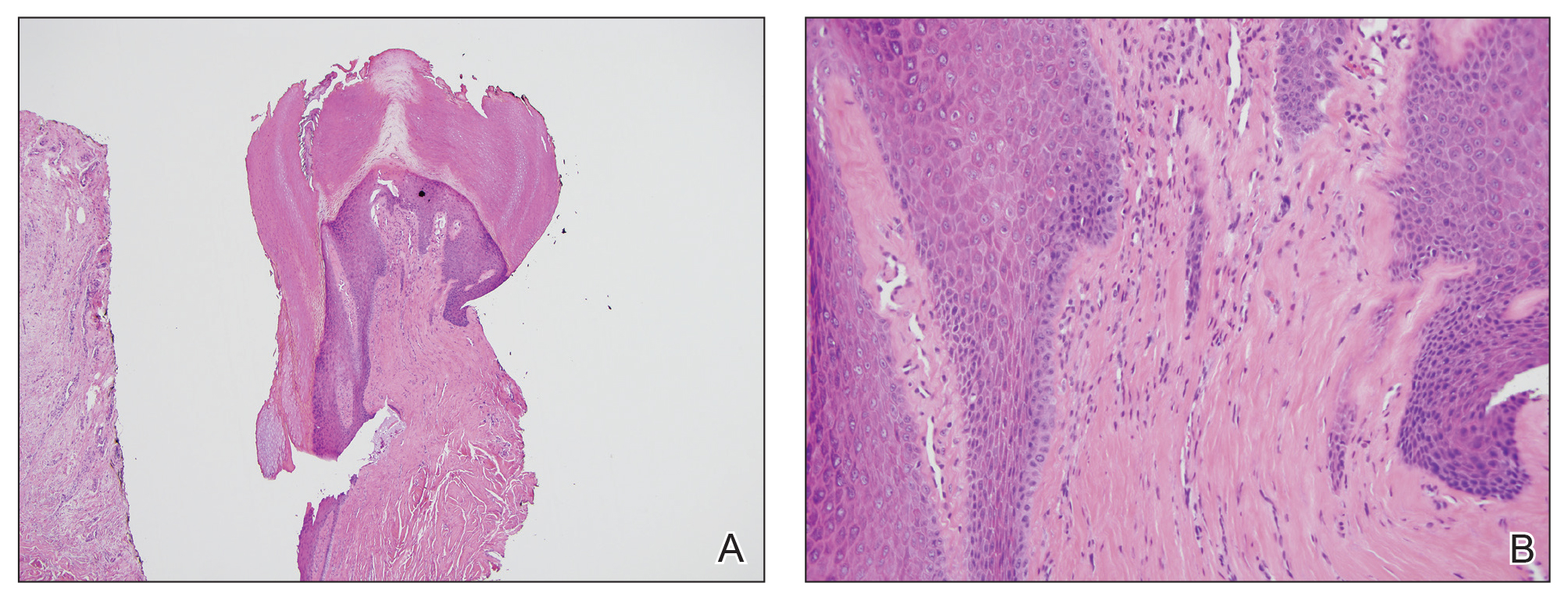

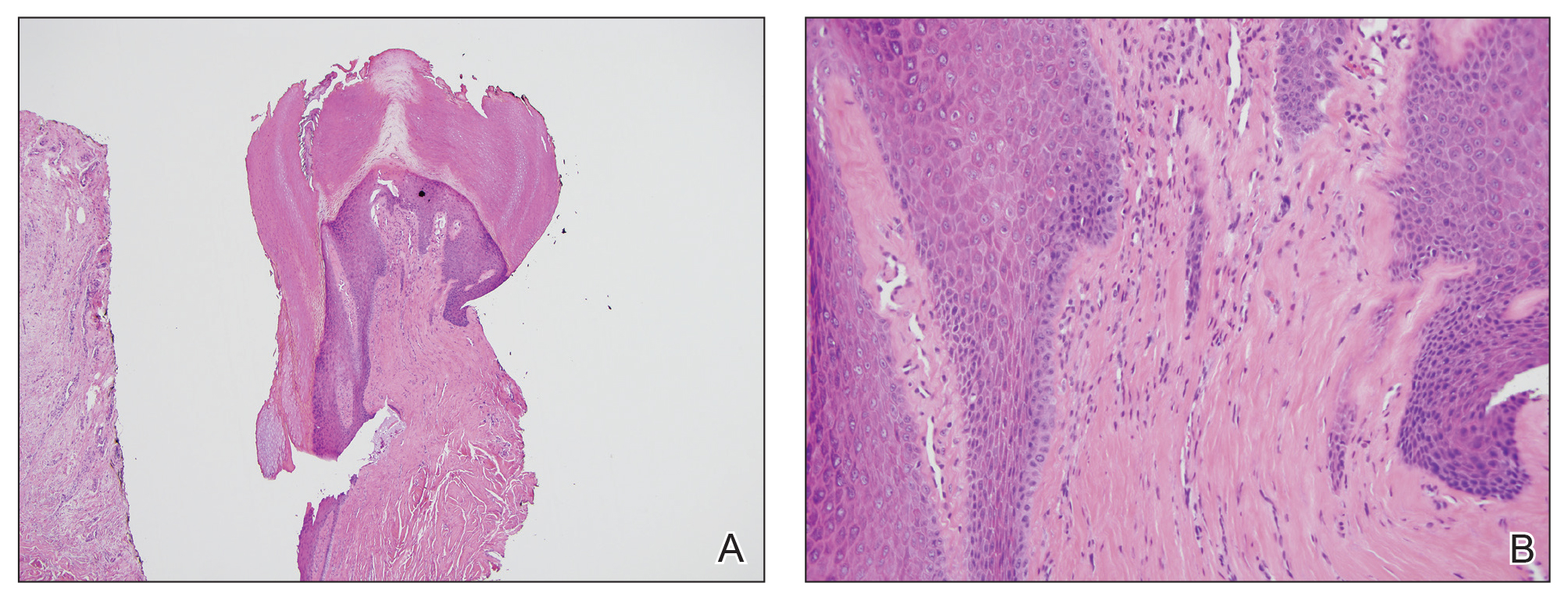

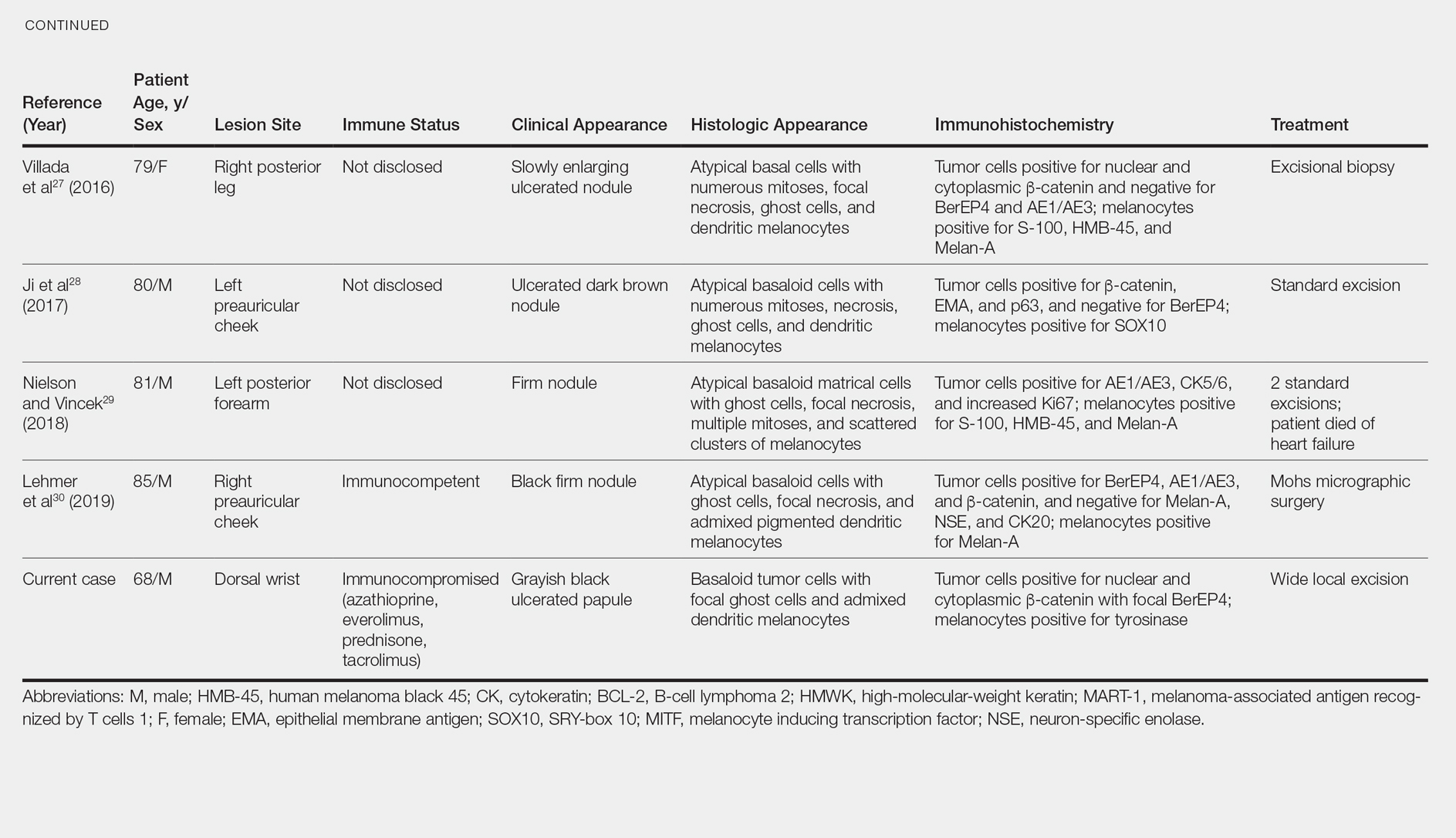

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

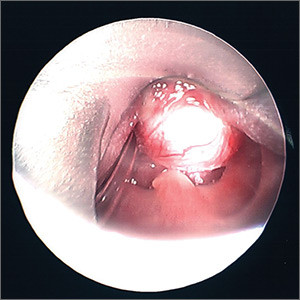

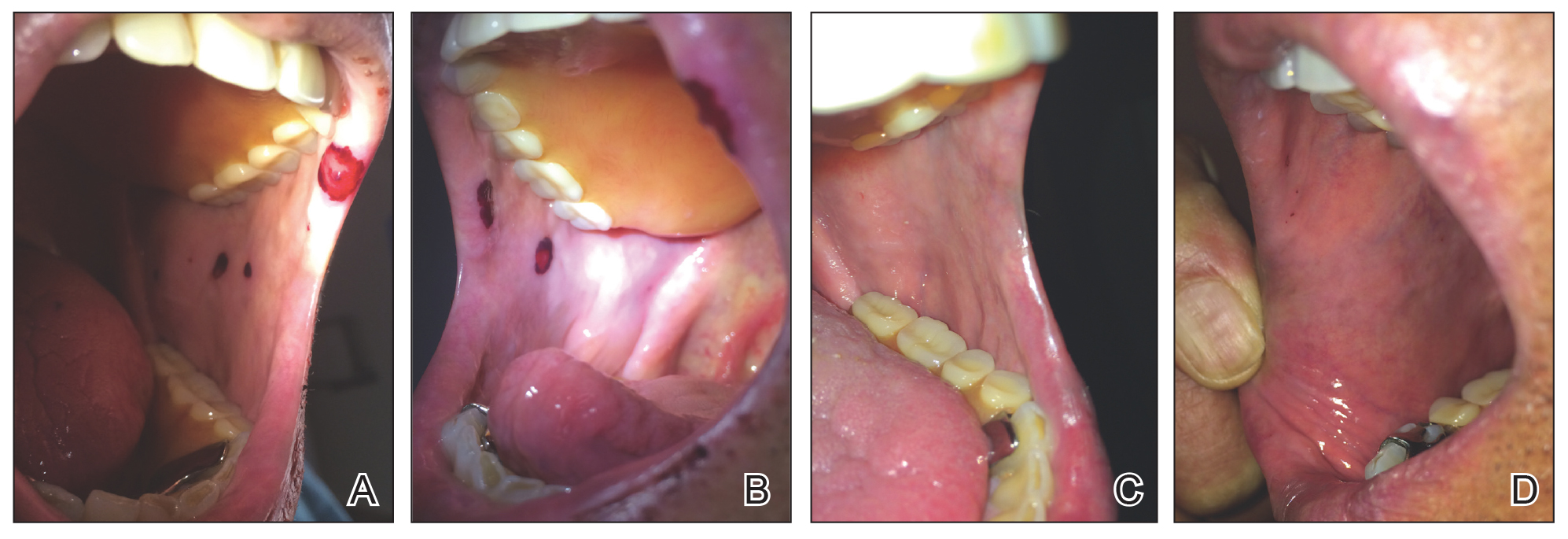

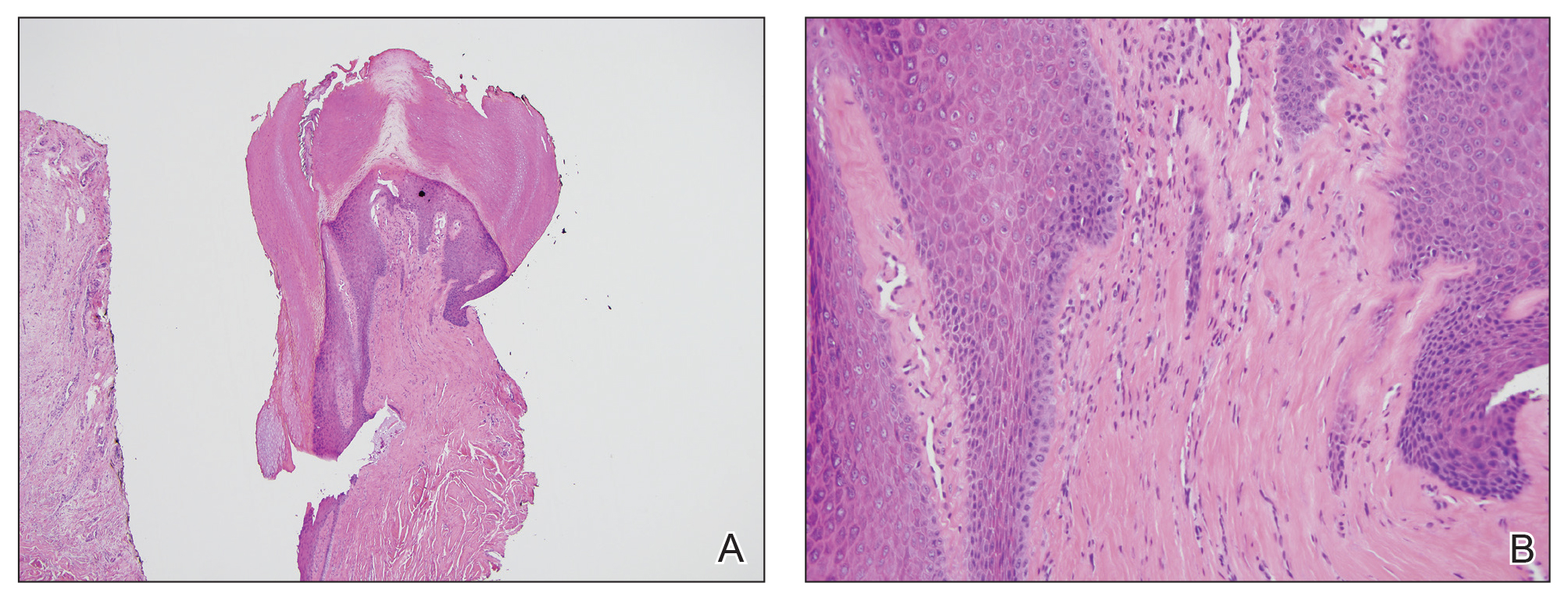

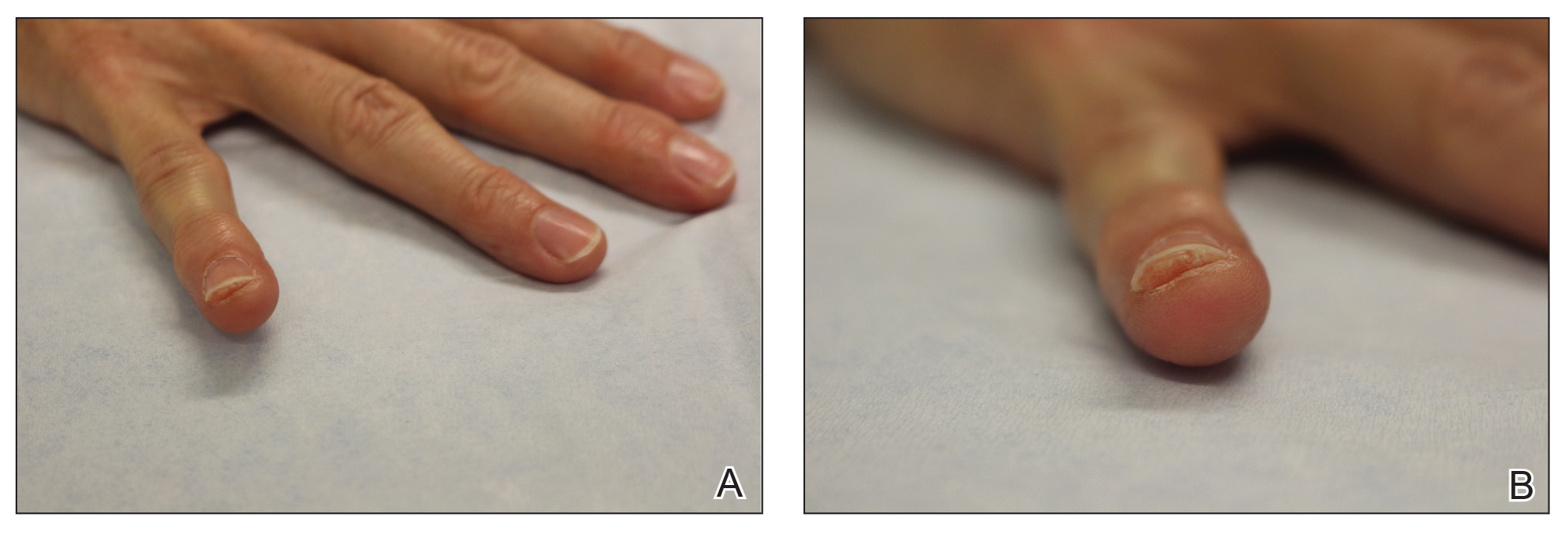

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

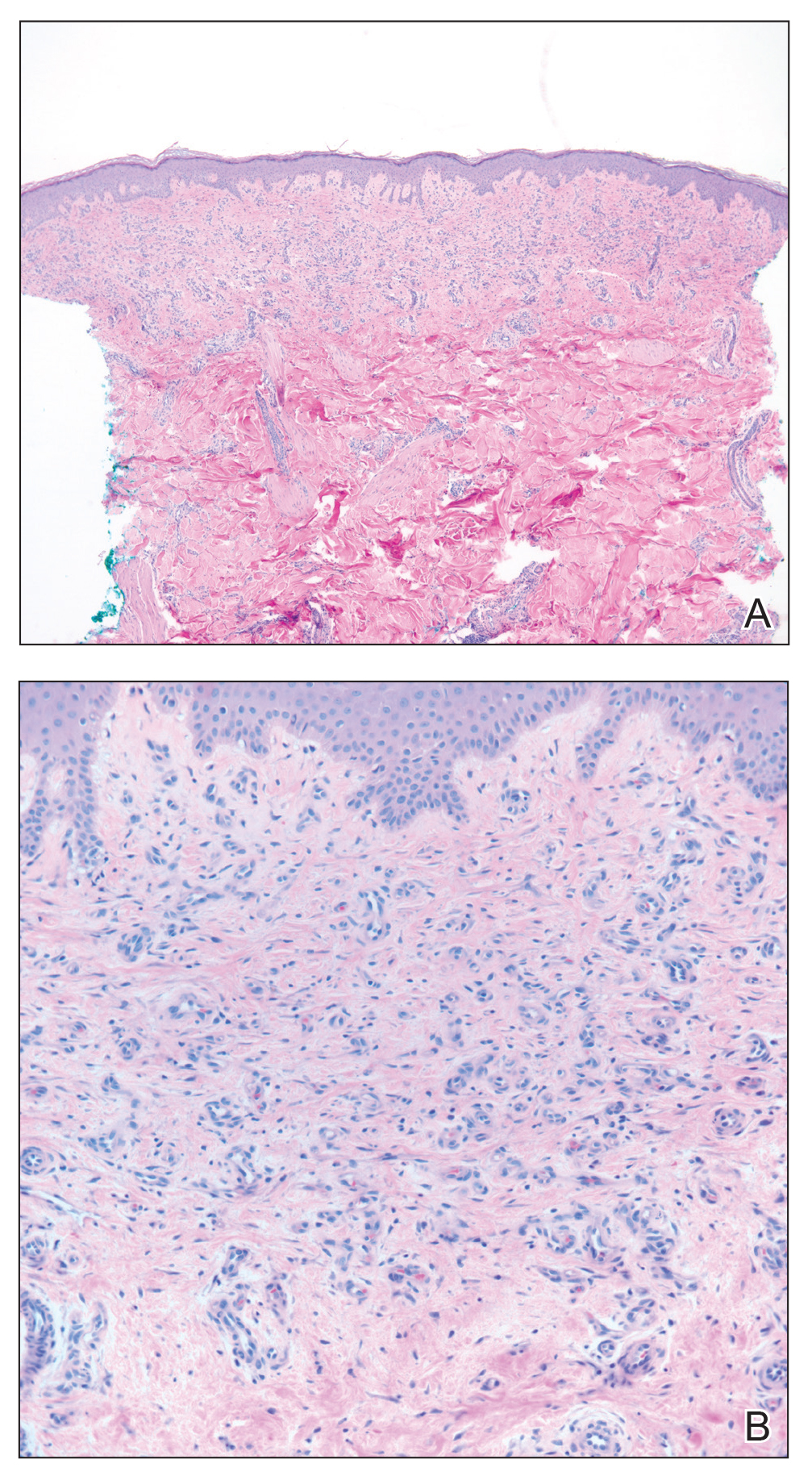

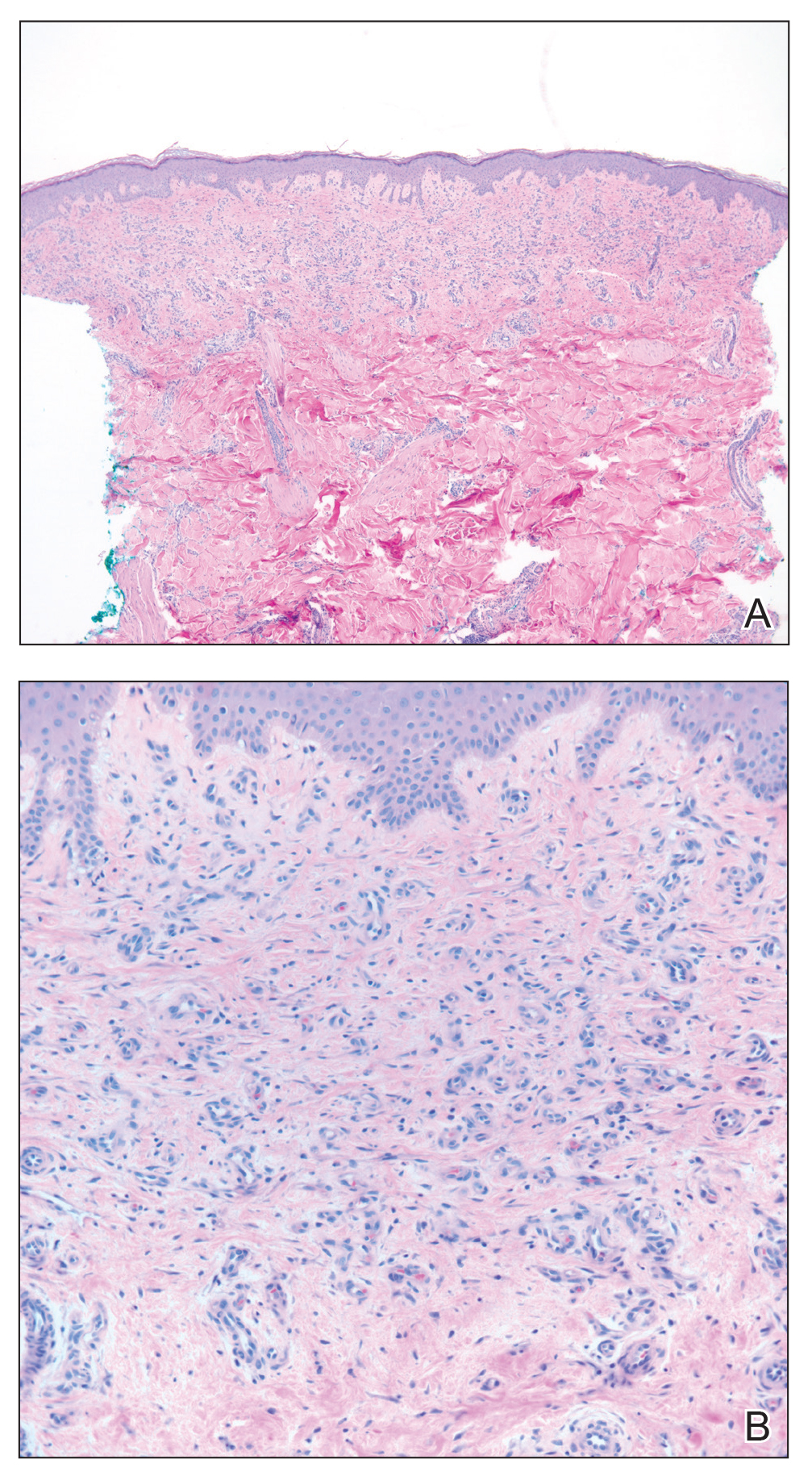

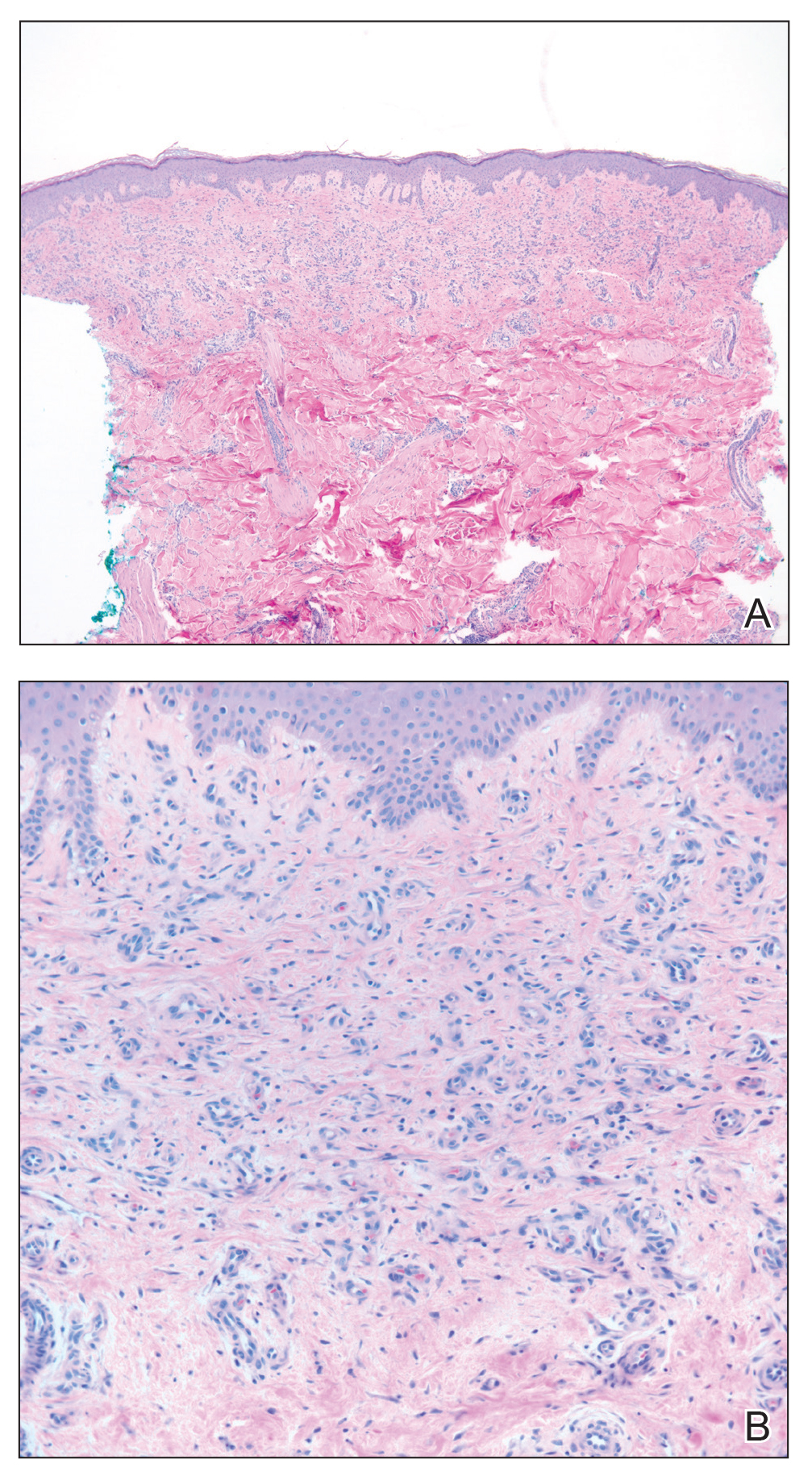

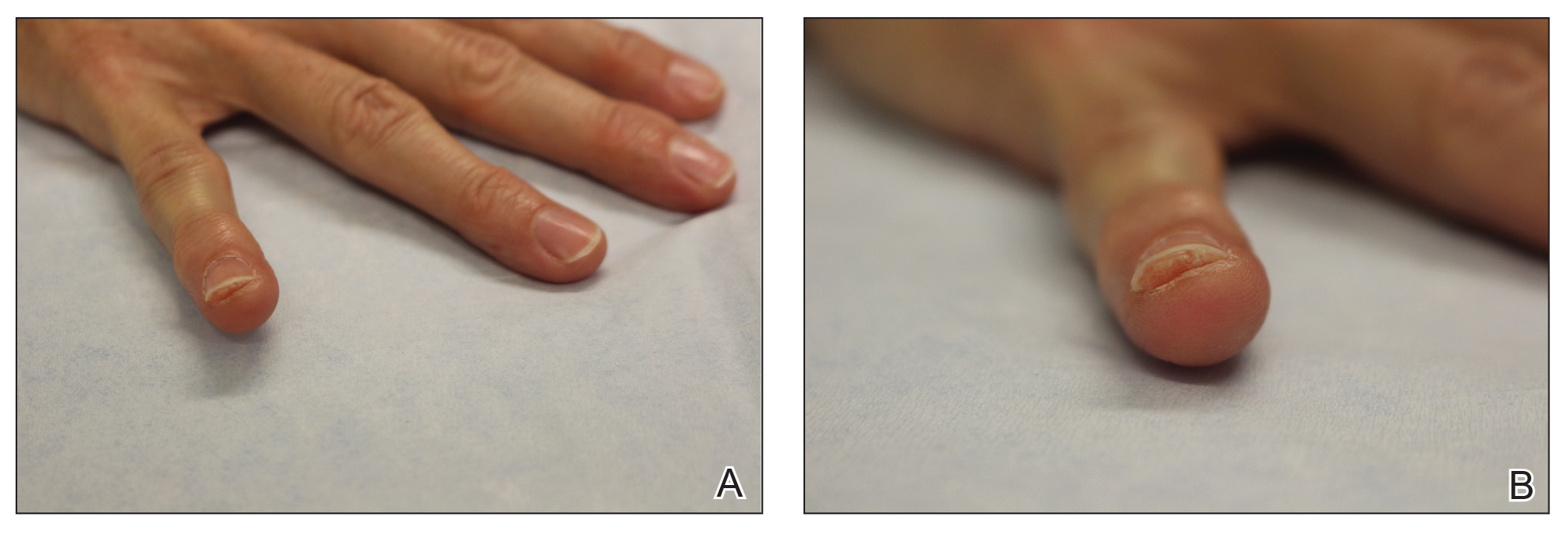

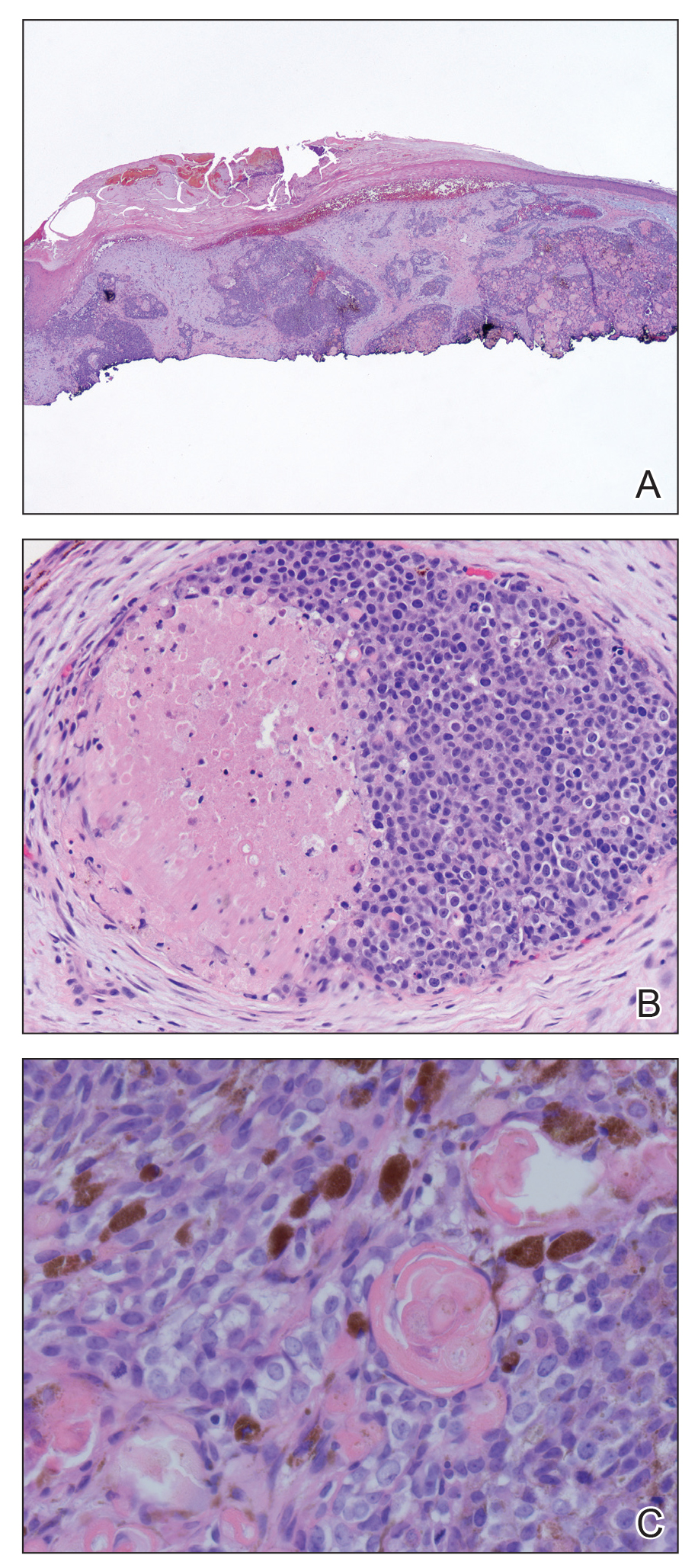

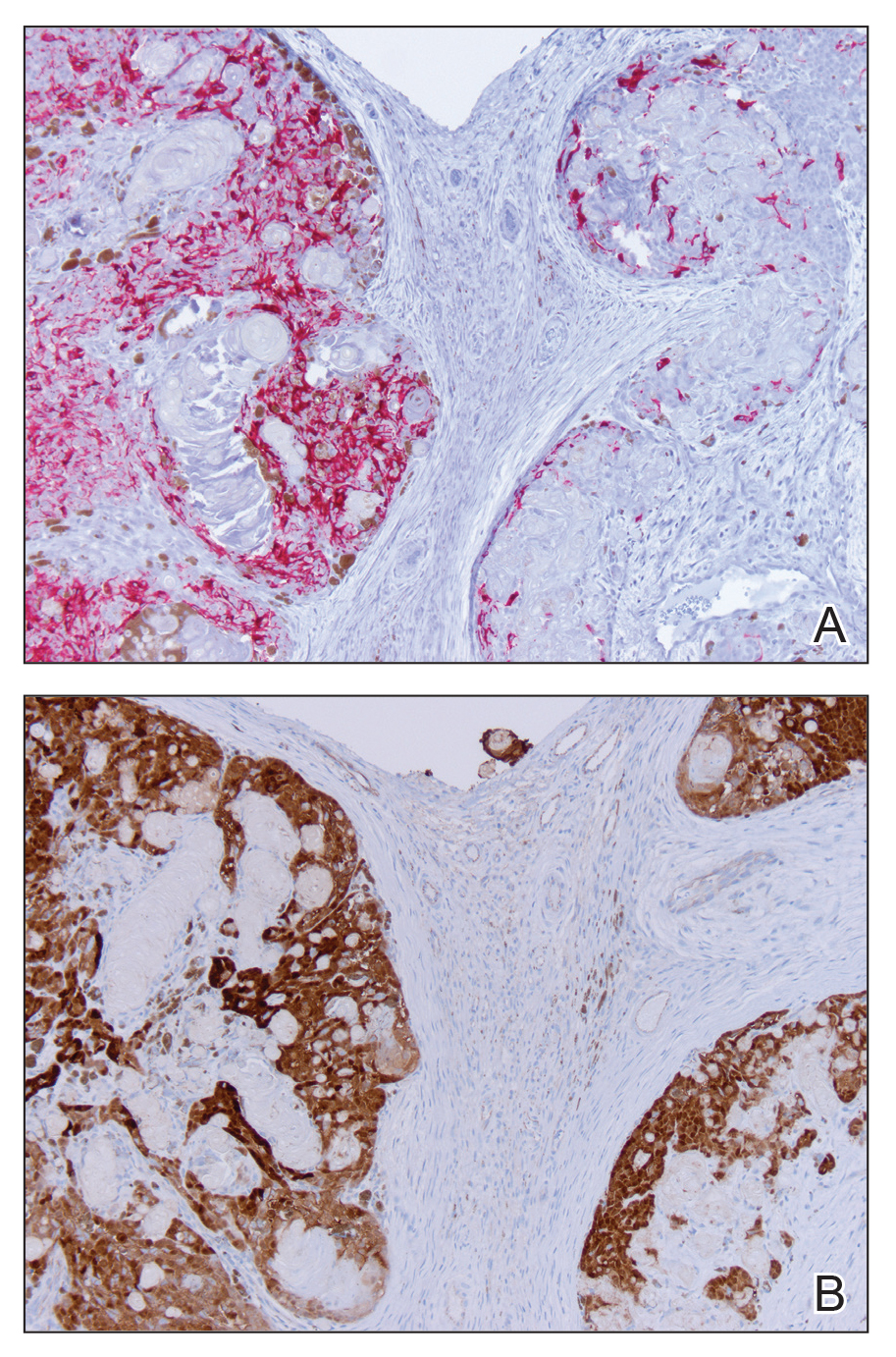

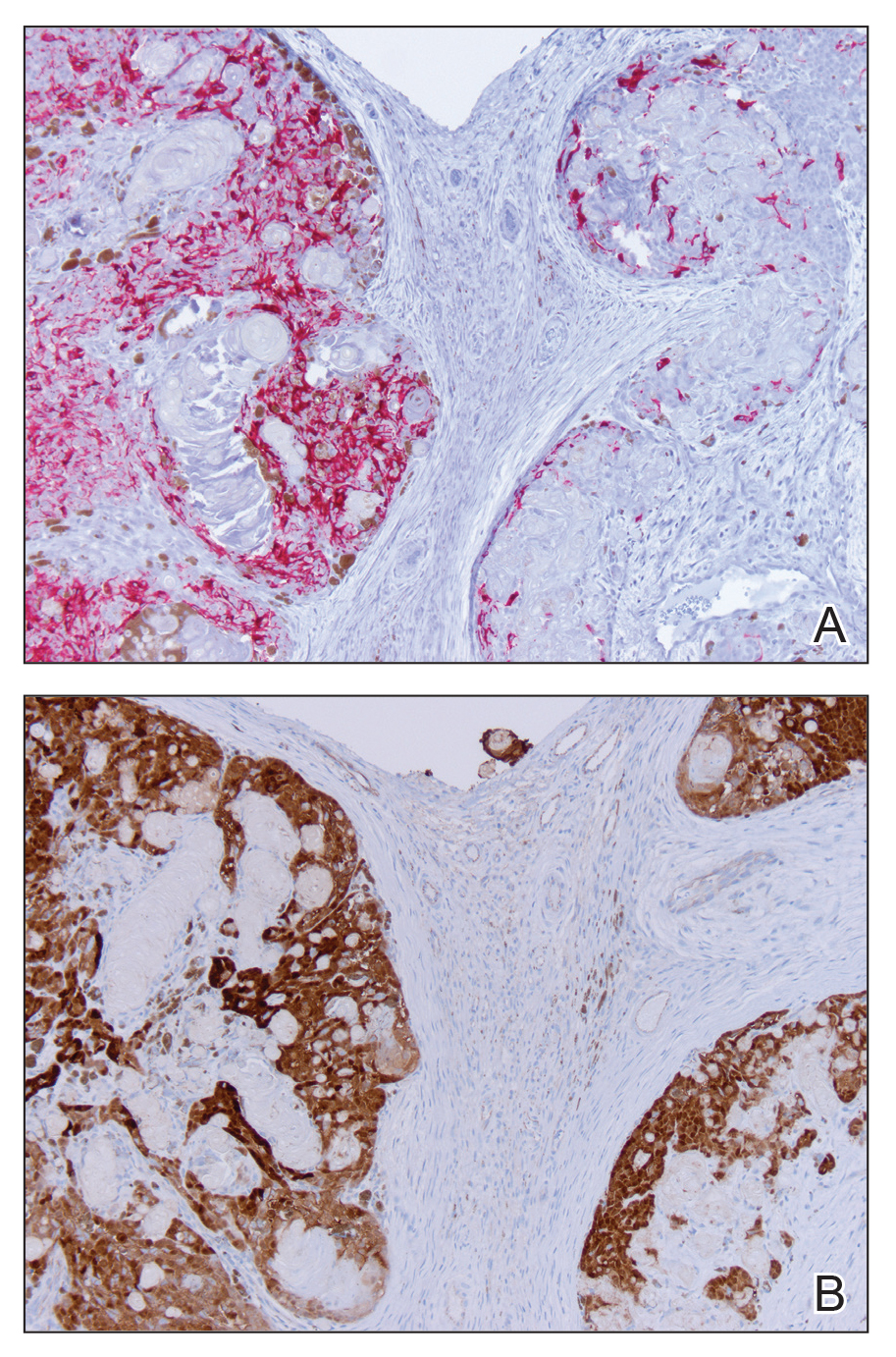

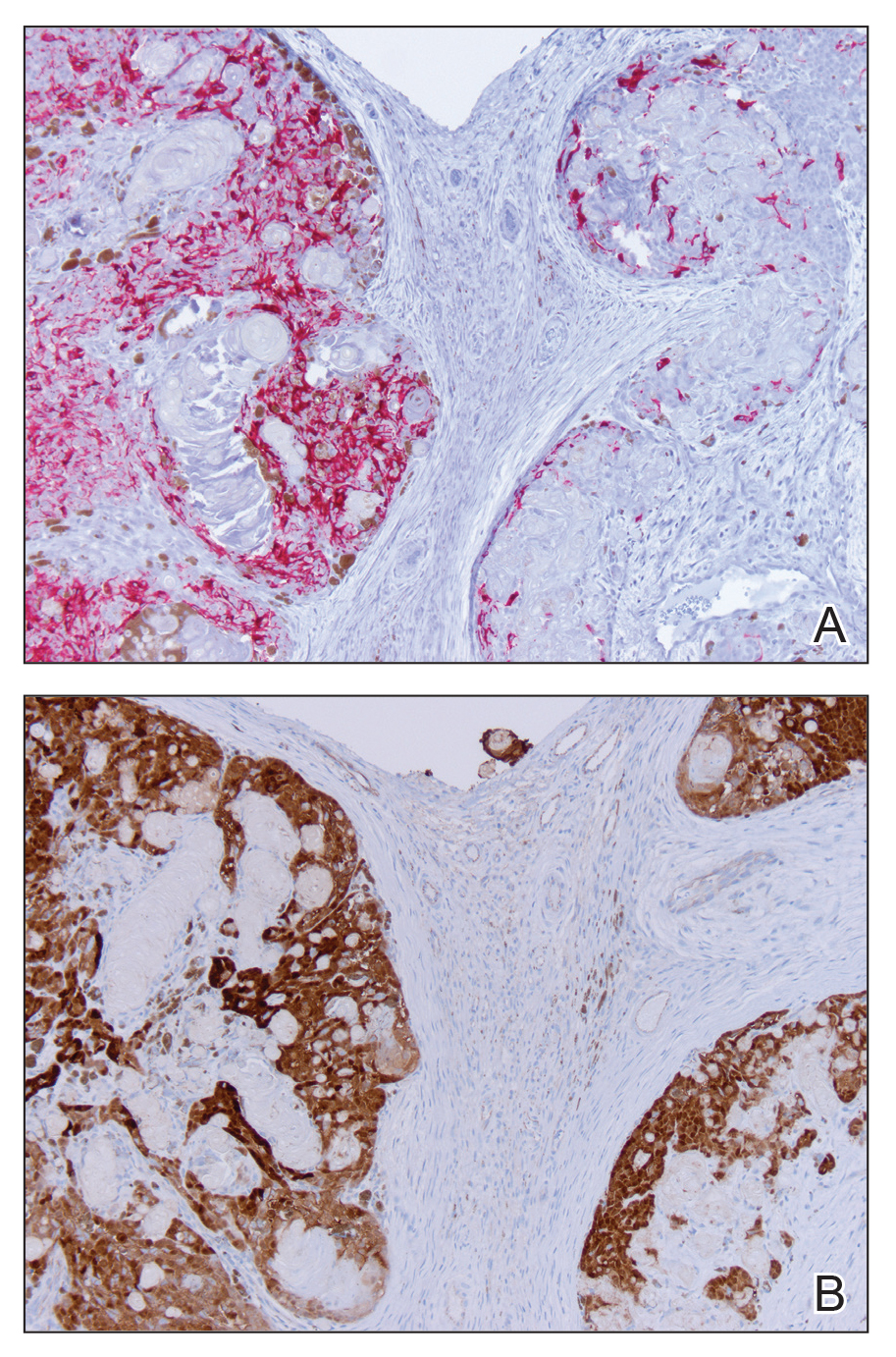

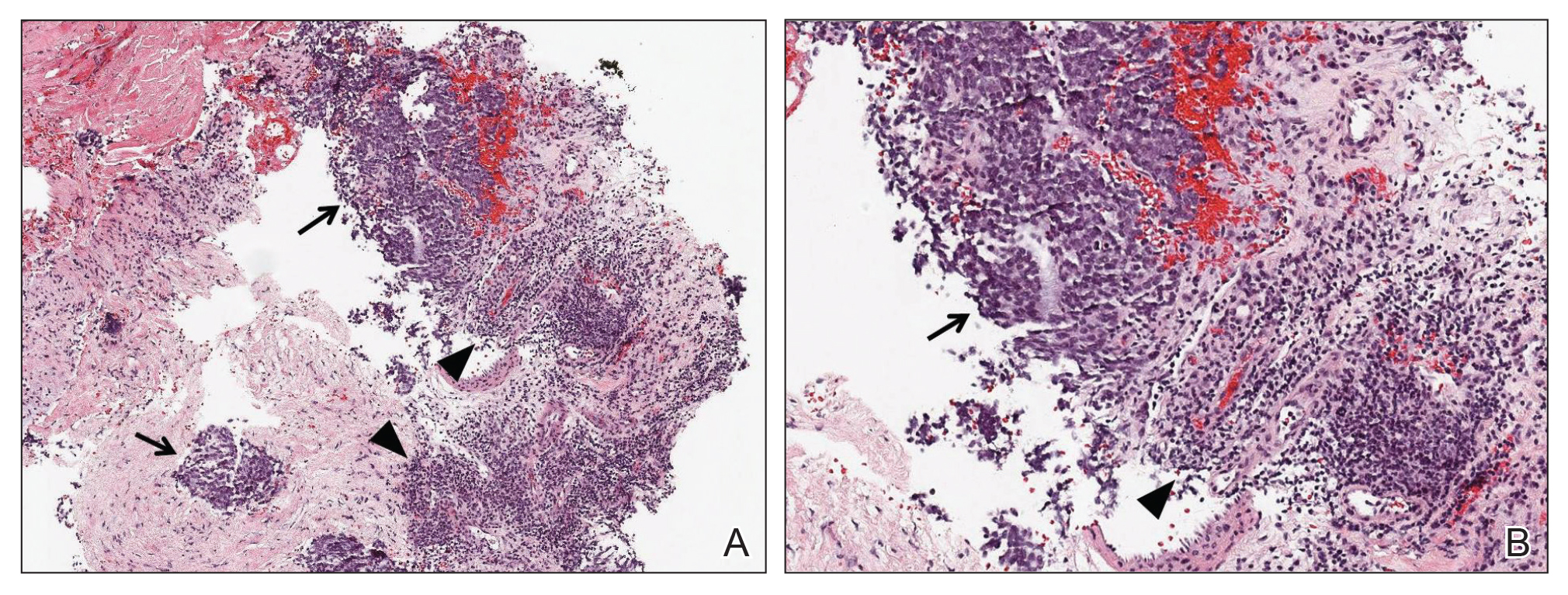

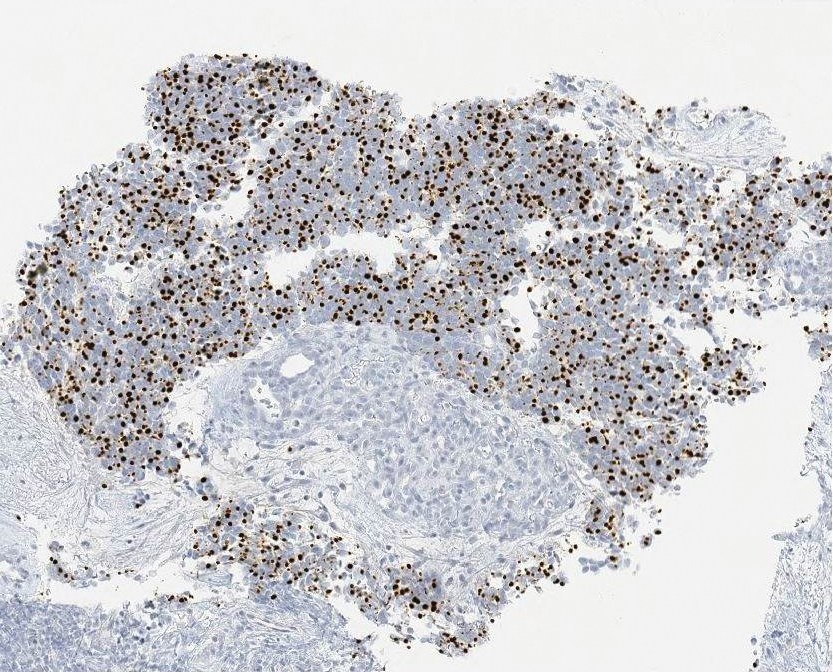

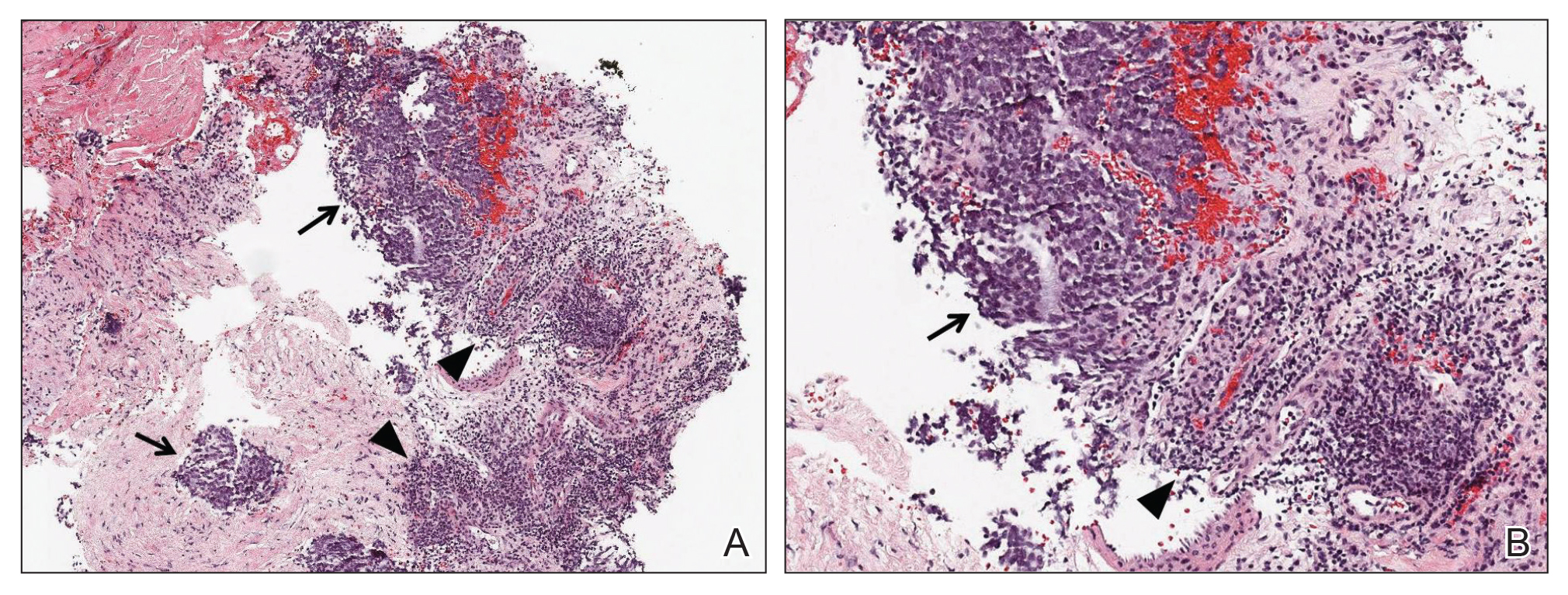

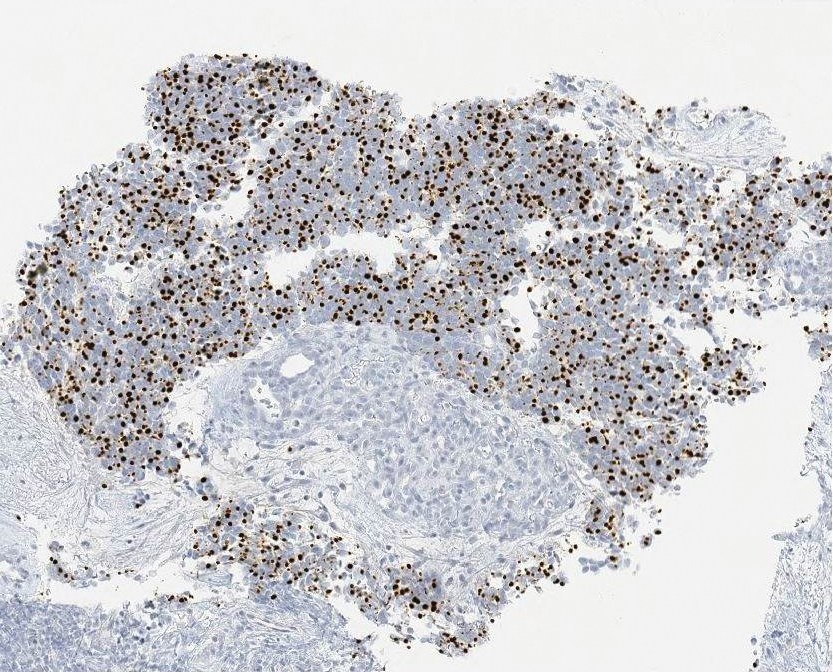

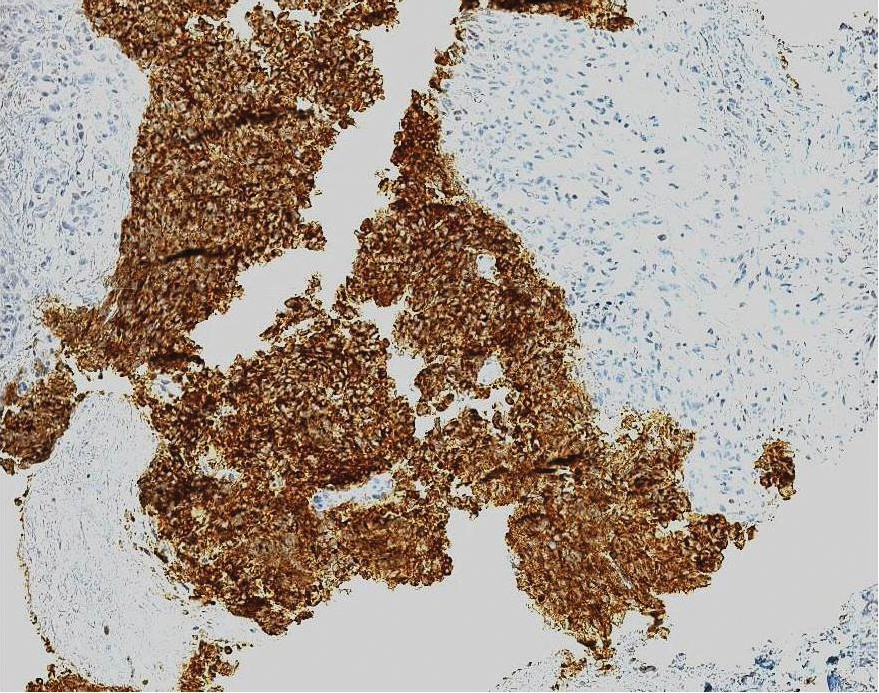

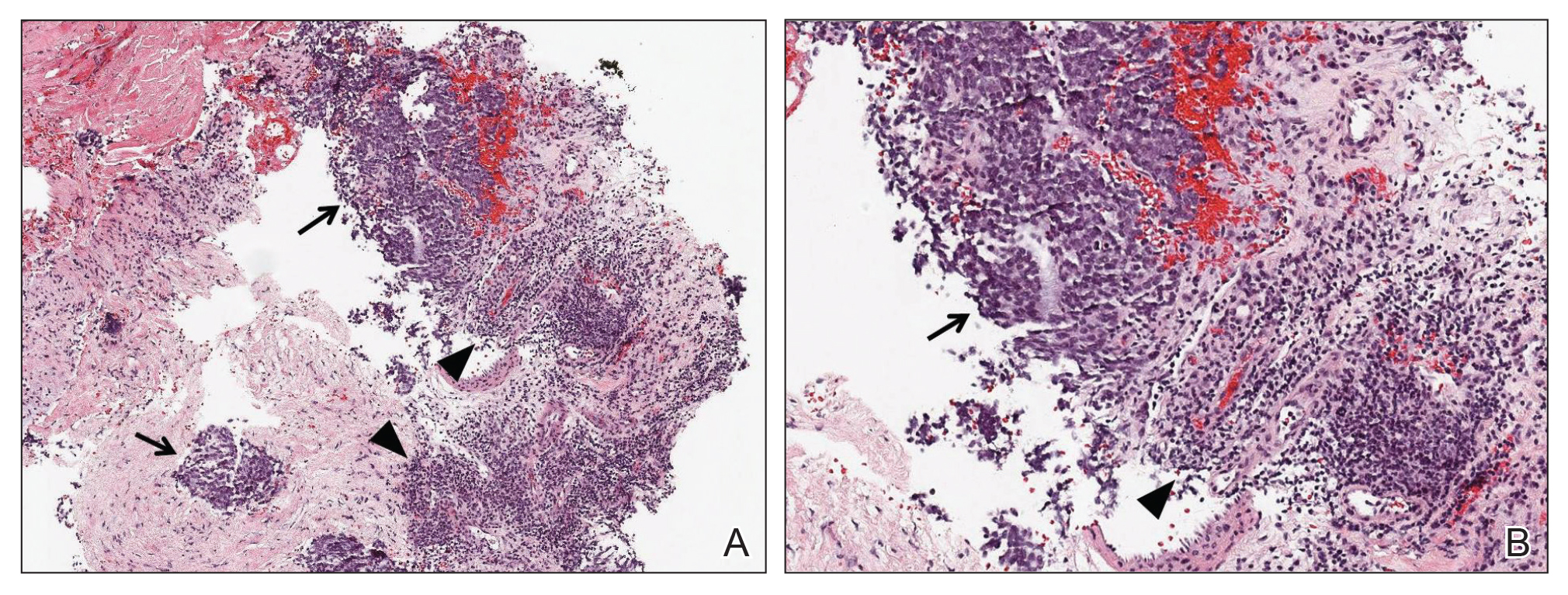

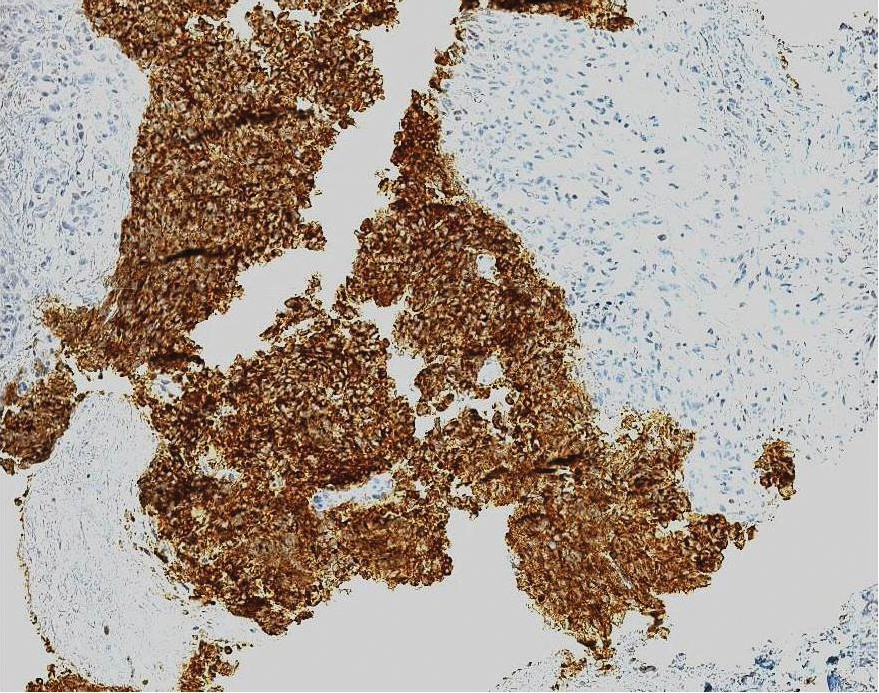

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

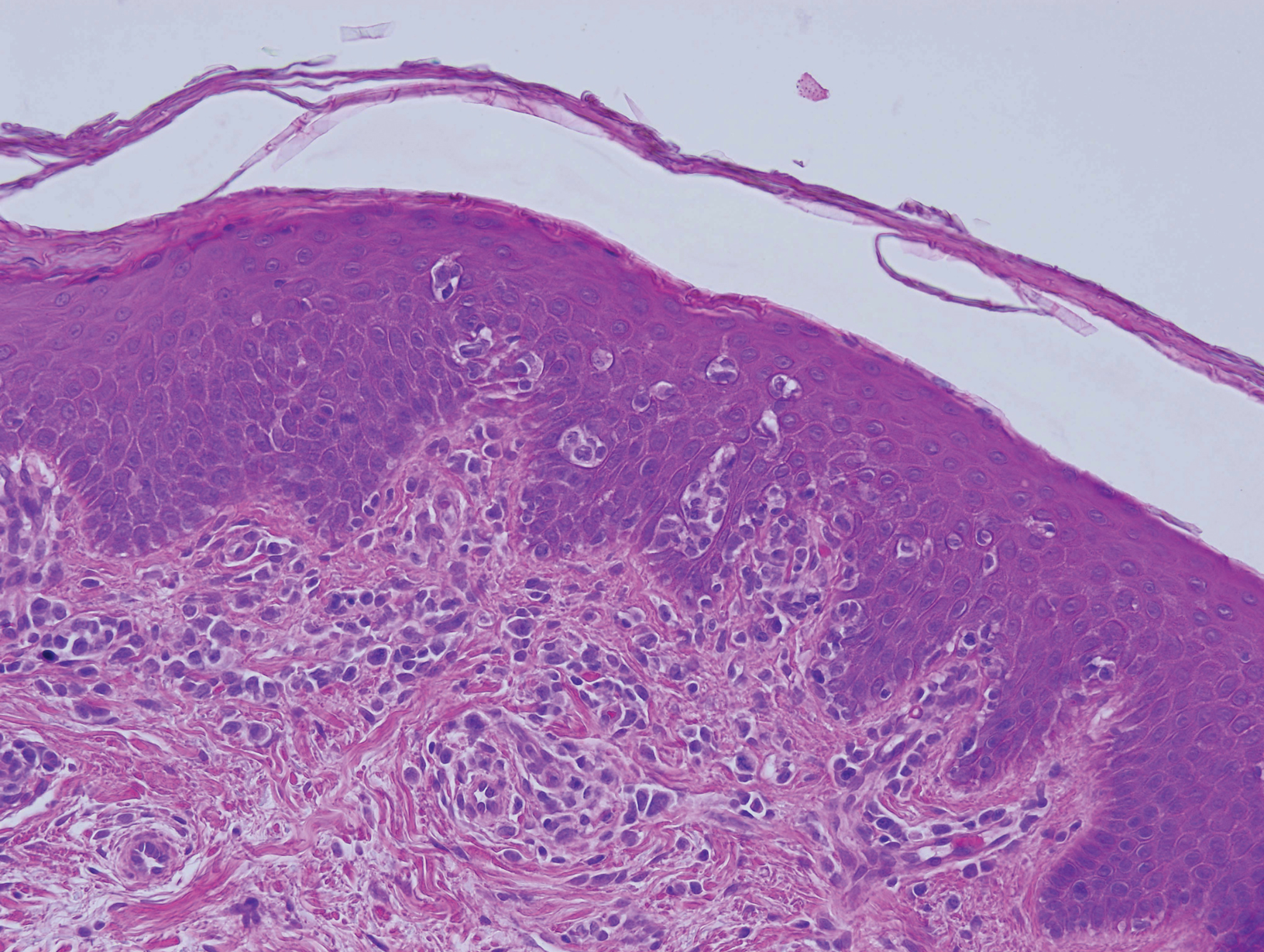

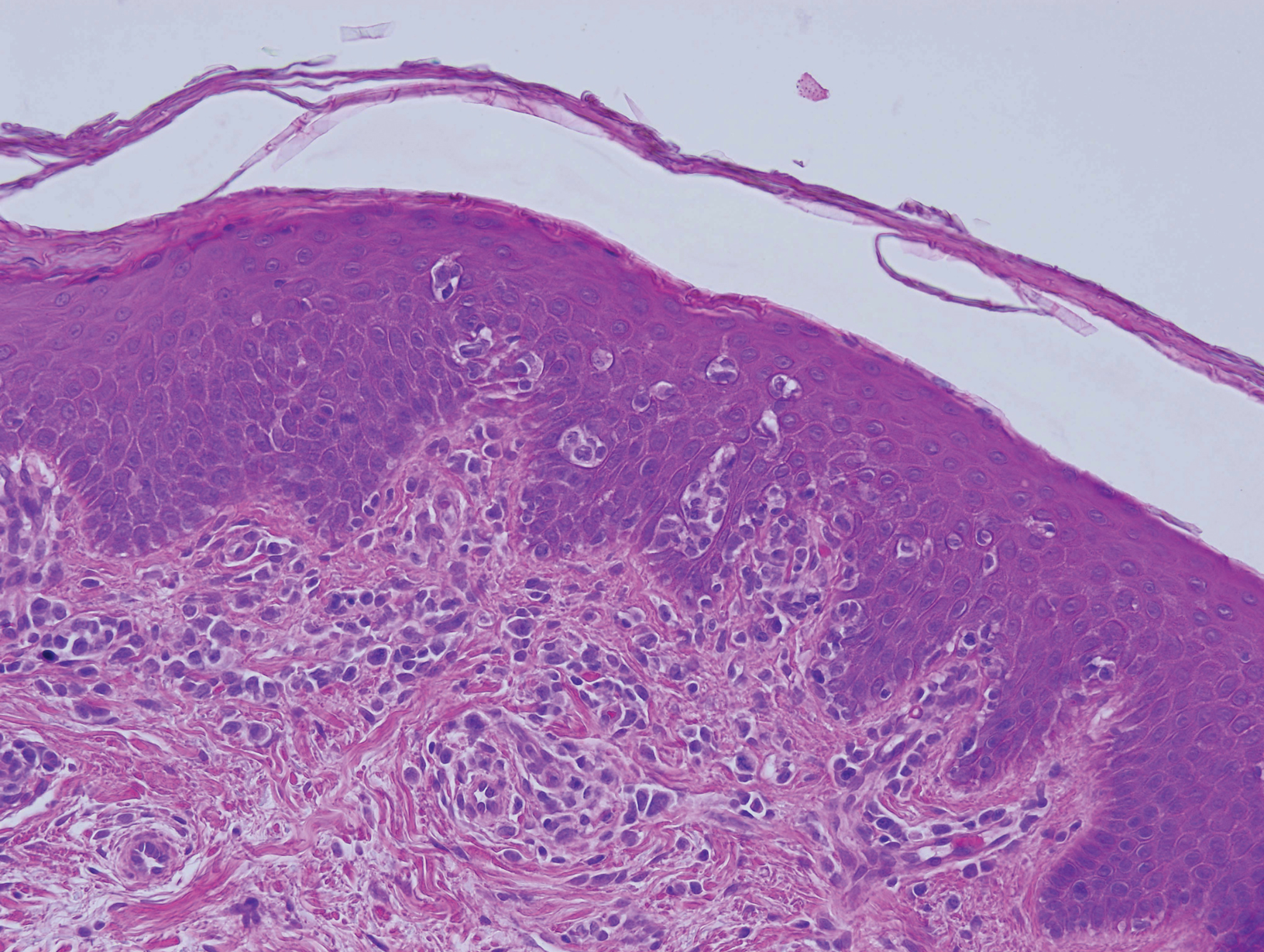

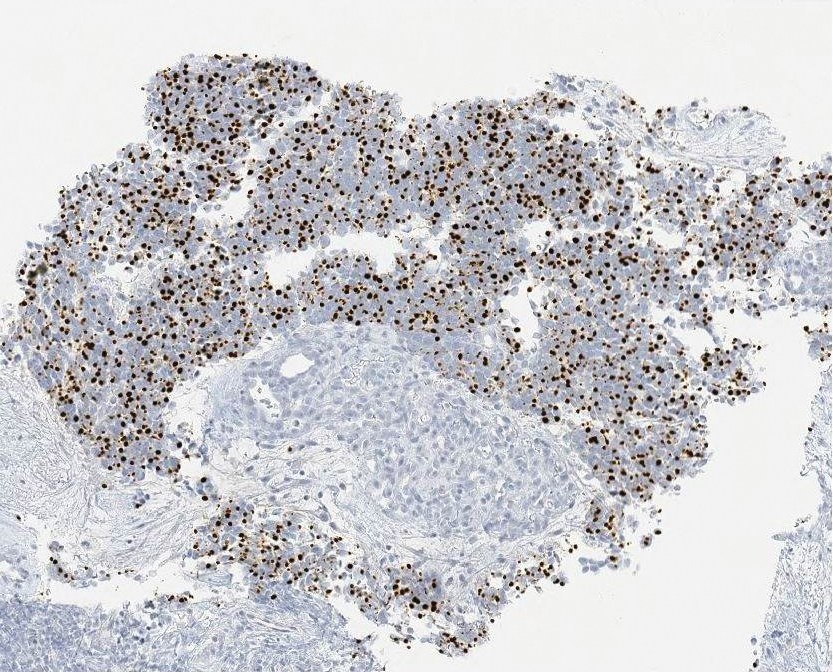

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 56-year-old white man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, bilateral knee replacement, and cataract removal presented to the emergency department with a worsening rash on the left posterior medial leg of 6 months’ duration. He reported associated redness and tenderness with the plaques as well as increased swelling and firmness of the leg. He was admitted to the hospital where the infectious disease team treated him with cefazolin for presumed cellulitis. His condition did not improve, and another course of cefazolin was started in addition to oral fluconazole and clotrimazole–betamethasone dipropionate lotion for a possible fungal cause. Again, treatment provided no improvement.

He was then evaluated by dermatology. On physical examination, the patient had edema, warmth, and induration of the left lower leg. There also was an annular and serpiginous indurated plaque with minimal scale on the left lower leg (Figure 1). A firm, dark red to purple plaque on the left medial thigh with mild scale was present. There also was scaling of the right plantar foot.

Skin biopsy revealed a dermal capillary proliferation with a scattering of inflammatory cells including eosinophils as well as dermal fibrosis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) immunostains were negative. Considering the degree and depth of vascular proliferation, Mali-type acroangiodermatitis (AAD) was the favored diagnosis.

Patient 2

A 72-year-old white man presented with a firm asymptomatic growth on the left dorsal forearm of 3 months’ duration. It was located near the site of a prior squamous cell carcinoma that was excised 1 year prior to presentation. The patient had no treatment or biopsy of the presenting lesion. His medical and surgical history included polycystic kidney disease and renal transplantation 4 years prior to presentation. He also had an arteriovenous fistula of the left arm. His other chronic diseases included chronic obstructive lung disease, congestive heart failure, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and obstructive sleep apnea.

On physical examination, the patient had a 1-cm violaceous nodule on the extensor surface of the left mid forearm. An arteriovenous fistula was present proximal to the lesion on the left arm (Figure 3).

Skin biopsy revealed a tightly packed proliferation of small vascular channels that tested negative for HHV-8, tumor protein p63, and cytokeratin 5/6. Erythrocytes were noted in the lumen of some of these vessels. Neutrophils were scattered and clustered throughout the specimen (Figure 4A). Blood vessels were highlighted with CD34 (Figure 4B). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain was negative for infectious agents. These findings favored AAD secondary to an arteriovenous malformation, consistent with Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome (SBS).

Comment

Presentation of AAD

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare chronic inflammatory skin process involving a reactive proliferation of capillaries and fibrosis of the skin that resembles Kaposi sarcoma both clinically and histopathologically. The condition has been reported in patients with chronic venous insufficiency,1 congenital arteriovenous malformation,2 acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula,3 paralyzed extremity,4 suction socket lower limb prosthesis (amputees),5 and minor trauma.6-8 The lesions of AAD tend to be circumscribed, slowly evolving, red-violaceous (or brown or dusky) macules, papules, or plaques that may become verrucous or develop into painful ulcerations. They generally occur on the distal dorsal aspects of the lower legs and feet.110

Variants of AAD

Mali et al9 first reported cutaneous manifestations resembling Kaposi sarcoma in 18 patients with chronic venous insufficiency in 1965. Two years later, Bluefarb and Adams10 described kaposiform skin lesions in one patient with a congenital arteriovenous malformation without chronic venous insufficiency. It was not until 1974, however, that Earhart et al11 proposed the term pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma.10,11 Based on these findings, AAD is described as 2 variants: Mali type and SBS.

Mali-type AAD is more common and typically occurs in elderly men. It classically presents bilaterally on the lower extremities in association with severe chronic venous insufficiency.5 Skin lesions usually occur on the medial aspect of the lower legs (as in patient 1), dorsum of the heel, hallux, or second toe.12

The etiology of Mali-type AAD is poorly understood. The leading theory is that the condition involves reduced perfusion due to chronic edema, resulting in neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, hypertrophy, and inflammatory skin changes. When AAD occurs in the setting of a suction socket prosthesis, the negative pressure of the stump-socket environment is thought to alter local circulation, leading to proliferation of small blood vessels.5,13

Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome usually involves a single extremity in young adults with congenital arteriovenous malformations, amputees, and individuals with hemiplegia or iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulae (as in patient 2).1 It was once thought to occur secondary to Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome; however, SBS rarely is accompanied by limb hypertrophy.9 Pathogenesis is thought to involve an angiogenic response to a high perfusion rate and high oxygen saturation, which leads to fibroblast proliferation and reactive endothelial hyperplasia.1,14

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Prompt identification of an underlying arteriovenous anomaly is critical, given the sequelae of high-flow shunts, which may result in skin ulceration, limb length discrepancy, cortical thinning of bone with regional osteoporosis, and congestive heart failure.1,5 Duplex ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic modality because it is noninvasive and widely available. The key doppler feature of an arteriovenous malformation is low resistance and high diastolic pulsatile flow,1 which should be confirmed with magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography angiography if present on ultrasonography.

The differential diagnosis of AAD includes Kaposi sarcoma, reactive angioendotheliomatosis, diffuse dermal angiomatosis, intravascular histiocytosis, glomeruloid angioendotheliomatosis, and angiopericytomatosis.15,16 These entities present as multiple erythematous, violaceous, purpuric patches and plaques generally on the extremities but can have a widely varied distribution. Some lesions evolve to necrosis or ulceration. Histopathologic analysis is useful to differentiate these entities.

Histopathology

The histopathologic features of AAD can be nonspecific; clinicopathologic correlation often is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Features include a proliferation of small thick-walled vessels, often in a lobular arrangement, in an edematous papillary dermis. Small thrombi may be observed. There may be increased fibroblasts; plump endothelial cells; a superficial mixed infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils; and deposition of hemosiderin.2,5 These characteristics overlap with features of Kaposi sarcoma; AAD, however, lacks slitlike vascular spaces, perivascular CD34+ expression, and nuclear atypia. A negative HHV-8 stain will assist in ruling out Kaposi sarcoma.1,17

Management

Treatment reports are anecdotal. The goal is to correct underlying venous hypertension. Conservative measures with compression garments, intermittent pneumatic compression, and limb elevation are first line.18 Oral antibiotics and local wound care with topical emollients and corticosteroids have been shown to be effective treatments.19-21

Oral erythromycin 500 mg 4 times daily for 3 weeks and clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% healed a lower extremity ulcer in a patient with Mali-type AAD.21 In another patient, conservative treatment of Mali-type AAD failed, but rapid improvement of 2 lower extremity ulcers resulted after 3 weeks of oral dapsone 50 mg twice daily.22

Conclusion

Acroangiodermatitis is a rare entity that is characterized by erythematous violaceous papules and plaques of the extremities, commonly in the setting of chronic venous insufficiency or an arteriovenous shunt. Histopathologic analysis shows proliferation of capillaries with fibrosis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and deposition of hemosiderin without the spindle cells and slitlike vascular spaces characteristic of Kaposi sarcoma. Detection of an underlying arteriovenous malformation is essential, as the disease can have local and systemic consequences, such as skin ulceration and congestive heart failure.1 Treatment options are conservative, directed toward local wound care, compression, and management of complications, such as ulceration and infection, as well as obliterating any underlying arteriovenous malformation.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

- Parsi K, O’Connor AA, Bester L. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: report of five cases and a review of literature. Phlebology. 2015;30:505-514.

- Larralde M, Gonzalez V, Marietti R, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma with arteriovenous malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:325-327.

- Nakanishi G, Tachibana T, Soga H, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma of the hand associated with acquired iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:415-416.

- Landthaler M, Langehenke H, Holzmann H, et al. Mali’s acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi) in paralyzed legs. Hautarzt. 1988;39:304-307.

- Trindade F, Requena L. Pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma because of suction socket lower limb prosthesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:482-485.

- Yu-Lu W, Tao Q, Hong-Zhong J, et al. Non-tender pedal plaques and nodules: pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (Stewart-Bluefarb type) induced by trauma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:927-930.

- Del-Río E, Aguilar A, Ambrojo P, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma induced by minor trauma in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:151-153.

- Archie M, Khademi S, Aungst D, et al. A rare case of acroangiodermatitis associated with a congenital arteriovenous malformation (Stewart-Bluefarb Syndrome) in a young veteran: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29:1448.e5-1448.e10.

- Mali JW, Kuiper JP, Hamers AA. Acro-angiodermatitis of the foot. Arch Dermatol. 1965;92:515-518.

- Bluefarb SM, Adams LA. Arteriovenous malformation with angiodermatitis. stasis dermatitis simulating Kaposi’s disease. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:176-181.

- Earhart RN, Aeling JA, Nuss DD, et al. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. A patient with arteriovenous malformation and skin lesions simulating Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:907-910.

- Lugovic´ L, Pusic´ J, Situm M, et al. Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma): three case reports. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2007;15:152-157.

- Horiguchi Y, Takahashi K, Tanizaki H, et al. Case of bilateral acroangiodermatitis due to symmetrical arteriovenous fistulas of the soles. J Dermatol. 2015;42:989-991.

- Dog˘an S, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma: a challenging vascular phenomenon. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:22.

- Mazloom SE, Stallings A, Kyei A. Differentiating intralymphatic histiocytosis, intravascular histiocytosis, and subtypes of reactive angioendotheliomatosis: review of clinical and histologic features of all cases reported to date. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:33-39.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Kanitakis J, Narvaez D, Claudy A. Expression of the CD34 antigen distinguishes Kaposi’s sarcoma from pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma (acroangiodermatitis). Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:44-46.

- Pires A, Depairon M, Ricci C, et al. Effect of compression therapy on a pseudo-Kaposi sarcoma. Dermatology. 1999;198:439-441.

- Hayek S, Atiyeh B, Zgheib E. Stewart-Bluefarb syndrome: review of the literature and case report of chronic ulcer treatment with heparan sulphate (Cacipliq20®). Int Wound J. 2015;12:169-172.

- Varyani N, Thukral A, Kumar N, et al. Nonhealing ulcer: acroangiodermatitis of Mali. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2011;2011:909383.

- Mehta AA, Pereira RR, Nayak C, et al. Acroangiodermatitis of Mali: a rare vascular phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:553-556.

- Rashkovsky I, Gilead L, Schamroth J, et al. Acro-angiodermatitis: review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:475-478.

Practice Points

- Acroangiodermatitis (AAD) may mimic Kaposi sarcoma clinically and histopathologically. A human herpesvirus 8 stain is helpful to differentiate these two entities.

- Diagnosis of AAD should prompt investigation of an underlying arteriovenous malformation, as the disease may have systemic consequences such as congestive heart failure.

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis Confined to the Oral Mucosa

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

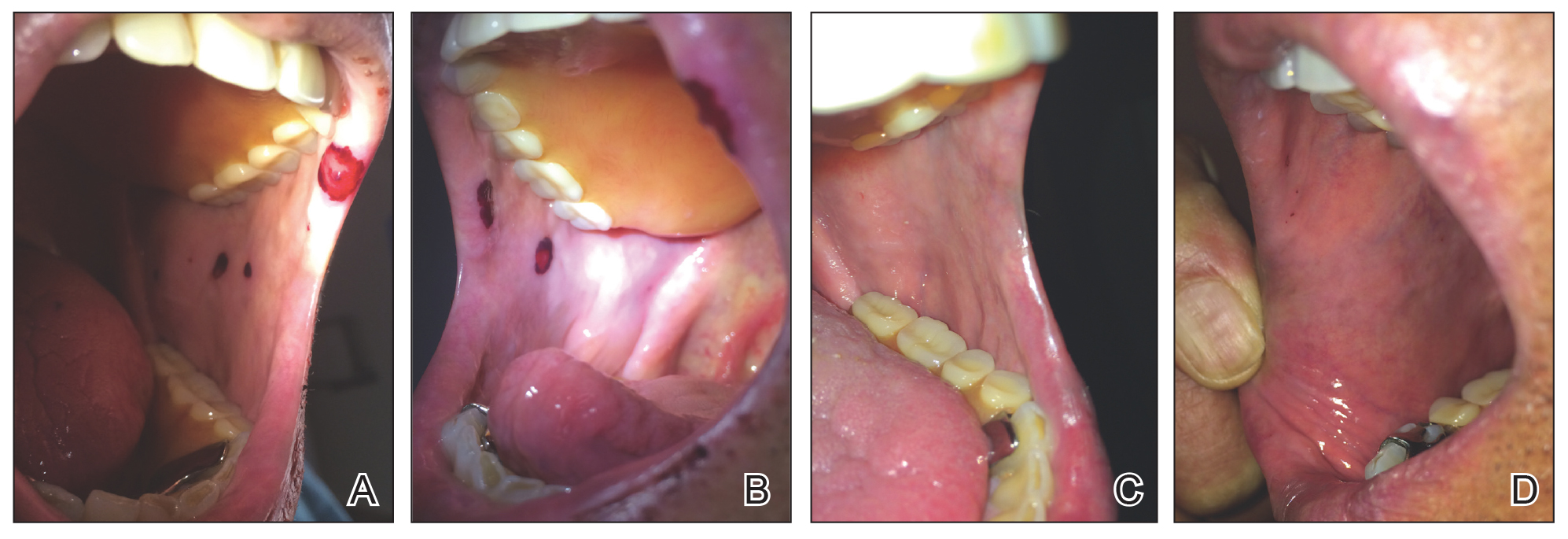

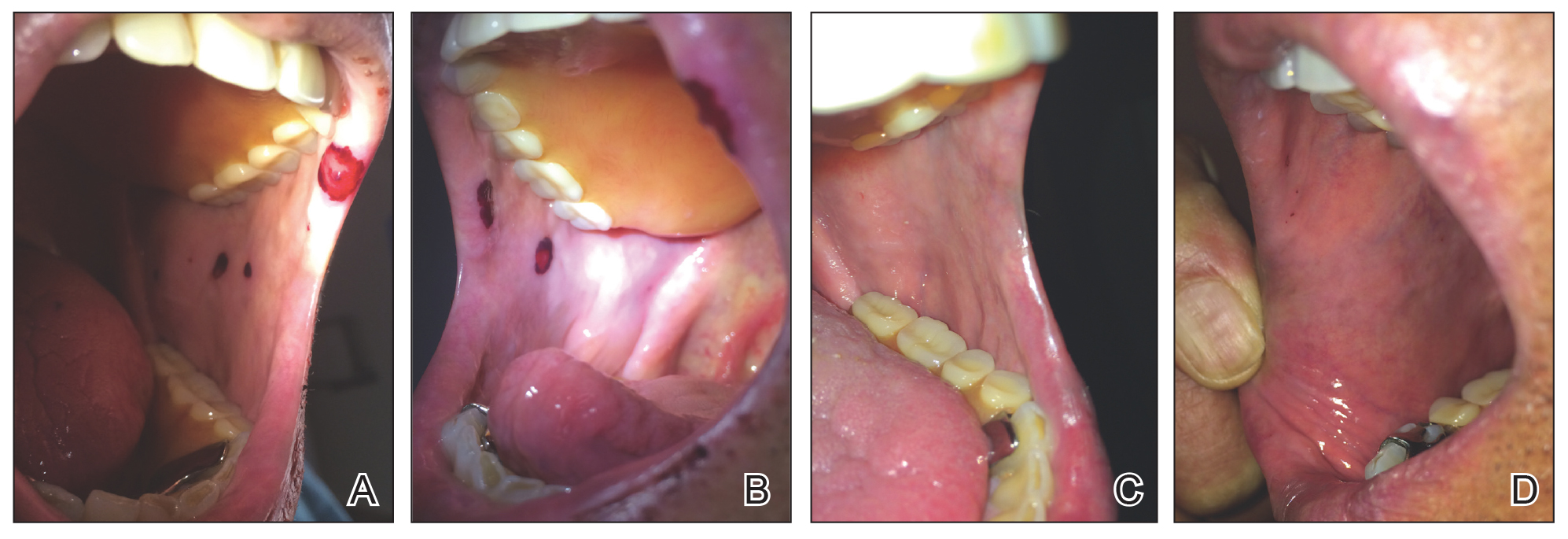

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant and is commonly used to treat or prevent venous thrombosis or the extension of thrombosis.

Adverse effects of heparin administration include bleeding, injection-site pain, and thrombocytopenia. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a serious side effect wherein antibodies are formed against platelet antigens and predispose the patient to venous and arterial thrombosis.

Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a poorly understood idiosyncratic drug reaction characterized by tense, blood-filled blisters that arise following the administration of subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). First reported in 2006 by Perrinaud et al

Case Report

An 84-year-old man was admitted to the cardiology service with severe substernal chest pain. An electrocardiogram did not show any ST-segment elevations; however, he had elevated troponin T levels. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease complicated by myocardial infarction (MI), as well as ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic stroke, and pulmonary embolism for which he was on long-term anticoagulation for years with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel. The patient was diagnosed with a non–ST-segment elevation MI. Accordingly, the patient’s warfarin was discontinued, and he was administered a bolus and continuous infusion of UFH. He also was continued on aspirin and clopidogrel. Within 6 hours of initiation of UFH, the patient noted multiple discrete swollen lesions in the mouth. Dermatology consultation and biopsy of the lesions were deferred due to acute management of the patient’s MI.

Physical examination revealed a moist oral mucosa with 7 slightly raised, hemorrhagic bullae ranging from 2 to 7 mm in diameter (Figure, A and B). One oral lesion was tense and had become denuded prior to evaluation. Laboratory testing included a normal platelet count (160,000/µL), a nearly therapeutic international normalized ratio (1.9), and a partial thromboplastin time that was initially normal (27 seconds) prior to admission and development of the oral lesions but found to be elevated (176 seconds) after admission and initial UFH bolus.

Upon further questioning, the patient revealed a history of similar oral lesions 1 year prior, following exposure to subcutaneous enoxaparin. At that time, formal evaluation by dermatology was deferred due to the rapid resolution of the blisters. Despite these new oral lesions, the patient was continued on a heparin drip for the next 48 hours because of the mortality benefit of heparin in non–ST-segment elevation MI. The patient was discharged from the hospital on a regimen of aspirin, warfarin, and clopidogrel. At 2-week follow-up, the oral lesions had resolved (Figure, C and D).

Comment

Heparin-Induced Skin Lesions

The 2 most common types of heparin-induced skin lesions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions and immune-mediated HIT. A 2009 Canadian study found that the overwhelming majority of heparin-induced skin lesions are due to delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions.

Types of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is one of the most serious adverse reactions to heparin administration. There are 2 subtypes of HIT, which differ in their clinical significance and pathophysiology.

Type II HIT is an immune-mediated response caused by the formation of IgG autoantibodies against the heparin–platelet factor 4 complex. Antibody formation and thrombocytopenia typically occur after 4 to 10 days of heparin exposure, and there can be devastating arterial and venous thrombotic complications.

Diagnosis of HIT

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be suspected in patients with a lowered platelet count, particularly if the decrease is more than 50% from baseline, and in patients who develop stroke, MI, pulmonary embolism, or deep vein thrombosis while on heparin. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not observed in our patient, as his platelet count remained stable between 160,000 and 164,000/µL throughout his hospital stay and he did not develop any evidence of thrombosis.

Differential Diagnosis

Our patient’s lesions appeared morphologically similar to

Bullous pemphigoid also was considered given the presence of tense bullae in an elderly patient. However, the rapid and spontaneous resolution of these lesions with complete lack of skin involvement made this diagnosis less likely.12

Heparin-Induced Bullous Hemorrhagic Dermatosis

Because our patient described a similar reaction while taking enoxaparin in the past, this case represents an idiosyncratic drug reaction, possibly from antibodies to a heparin-antigen complex. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis is a rarely reported condition with the majority of lesions presenting on the extremities.

Conclusion

We describe a rare side effect of heparin therapy characterized by discrete blisters on the oral mucosa. However, familiarity with the spectrum of reactions to heparin allowed the patient to continue heparin therapy despite this side effect, as the eruption was not life-threatening and the benefit of continuing heparin outweighed this adverse effect.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

- Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML, Calvo-Rojas G, et al. Discovery of anticoagulant drugs: a historical perspective. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2012;9:83-104.

- Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemical approaches to define the structure-activity relationship of heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. Chem Biol. 2005;12:731-756.

- Bakchoul T. An update on heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:787-797.

- Schindewolf M, Schwaner S, Wolter M, et al. Incidence and causes of heparin-induced skin lesions. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:477-481.

- Perrinaud A, Jacobi D, Machet MC, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis occurring at sites distant from subcutaneous injections of heparin: three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(2 suppl):S5-S7.

- Naveen KN, Rai V. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:423.

- Choudhry S, Fishman PM, Hernandez C. Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis. Cutis. 2013;91:93-98.

- Villanueva CA, Nájera L, Espinosa P, et al. Bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis at distant sites: a report of 2 new cases due to enoxaparin injection and a review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:816-819.

- Ahmed I, Majeed A, Powell R. Heparin induced thrombocytopenia: diagnosis and management update. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:575-582.

- Horie N, Kawano R, Inaba J, et al. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica of the soft palate: a clinical study of 16 cases. J Oral Sci. 2008;50:33-36.

- Rai S, Kaur M, Goel S. Angina bullosa hemorrhagica: report of 2 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:503.

- Lawson W. Bullous oral lesions: clues to identifying—and managing—the cause. Consultant. 2013;53:168-176.

Practice Points

- It is important for physicians to recognize the clinical appearance of cutaneous adverse reactions to heparin, including bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis.

- Heparin-induced bullous hemorrhagic dermatosis tends to self-resolve, even with continuation of unfractionated heparin.

Erythema Gyratum Repens–like Eruption in Sézary Syndrome: Evidence for the Role of a Dermatophyte

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman presented with stage IVA2 mycosis fungoides (MF)(T4N3M0B2)/Sézary syndrome (SS). A peripheral blood count contained 6000 Sézary cells with cerebriform nuclei, a CD2+/−CD3+CD4+CD5+/−CD7+CD8−CD26−immunophenotype, and a highly abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio (70:1). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography demonstrated hypermetabolic subcutaneous nodules in the base of the neck and generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymph node biopsy showed involvement by T-cell lymphoma and dominant T-cell receptor γ clonality by polymerase chain reaction.

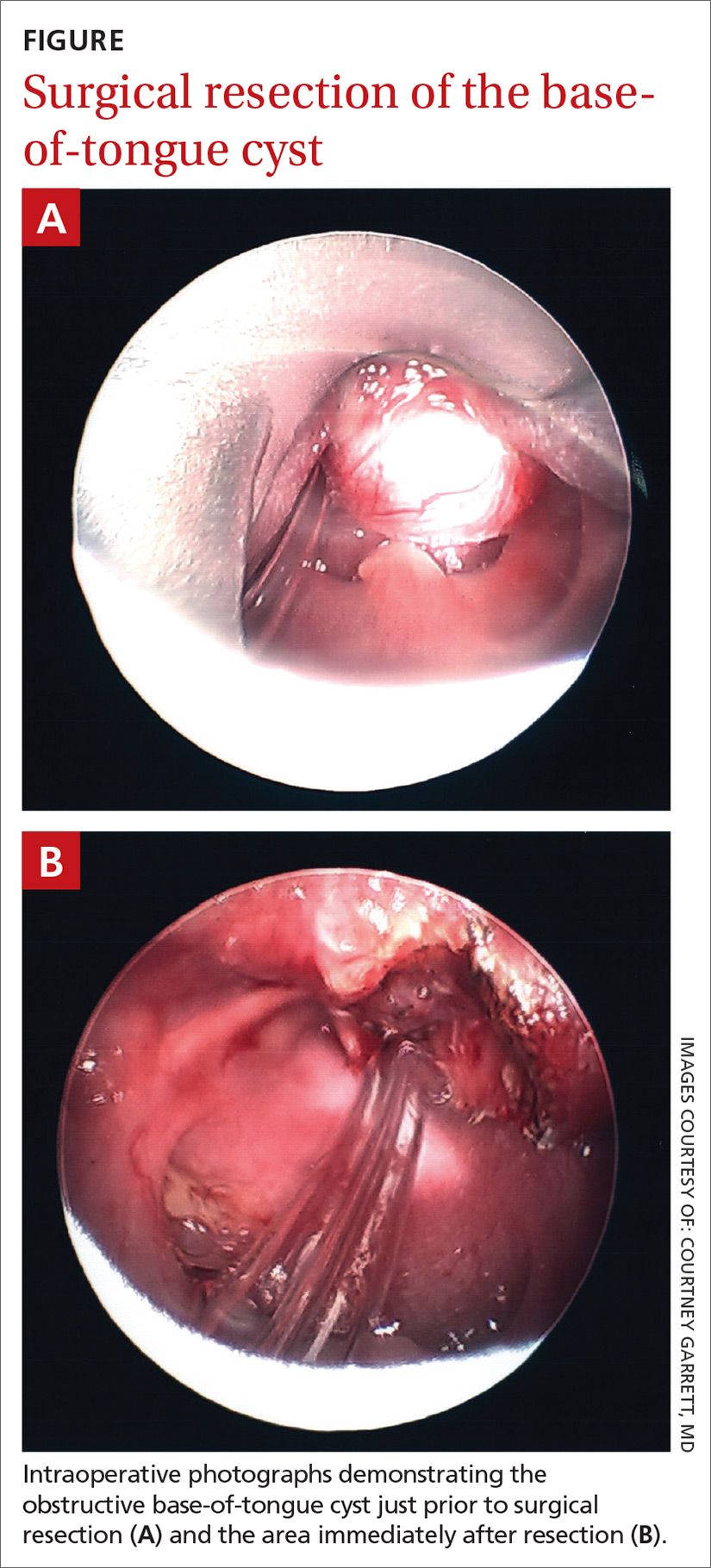

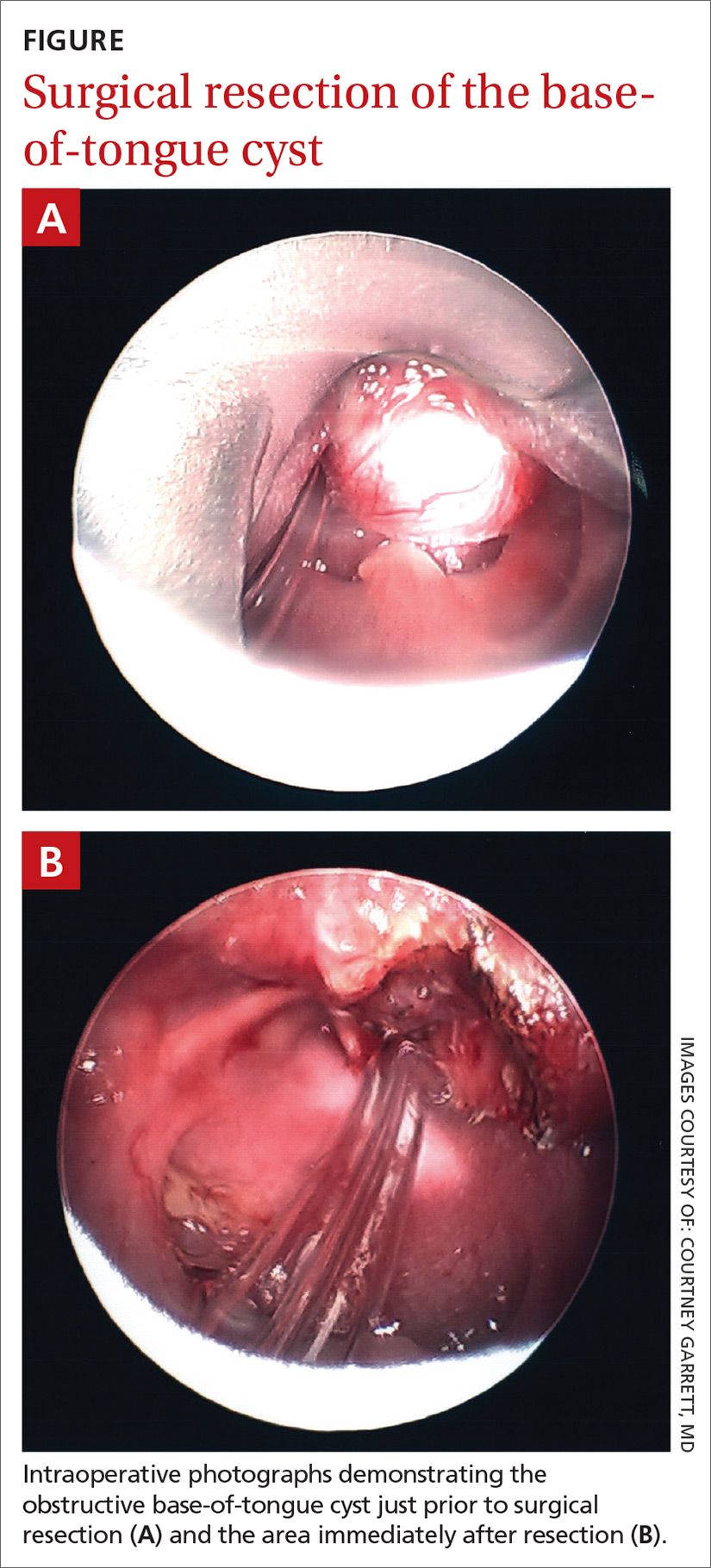

On initial presentation to the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the patient was erythrodermic. She also was noted to have undulating wavy bands and concentric annular, ringlike, thin, erythematous plaques with trailing scale, giving a wood grain, zebra hide–like appearance involving the buttocks, abdomen, and lower extremities (Figure 1). Lesions were markedly pruritic and were advancing rapidly. A diagnosis of erythema gyratum repens (EGR)–like eruption was made.

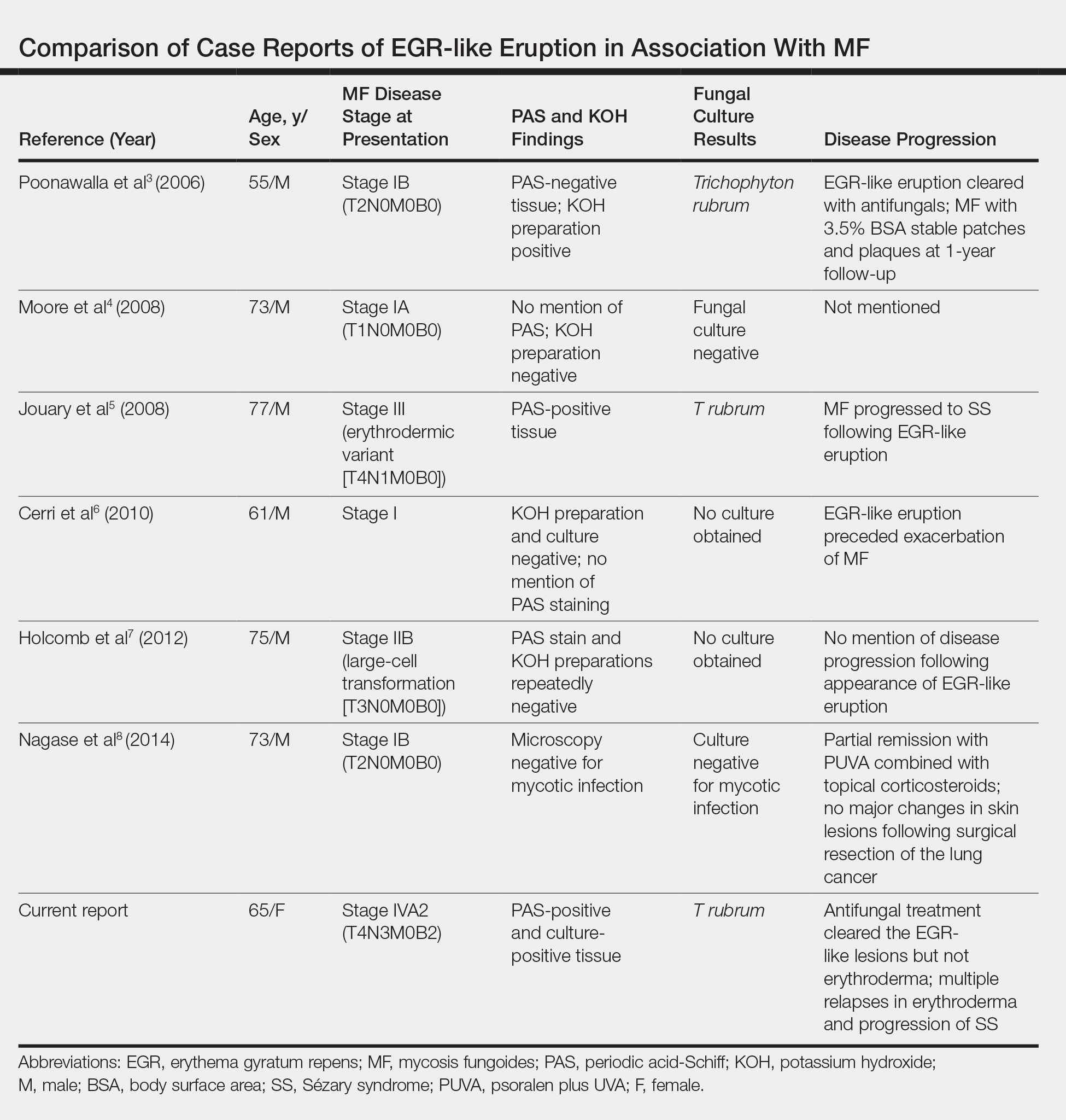

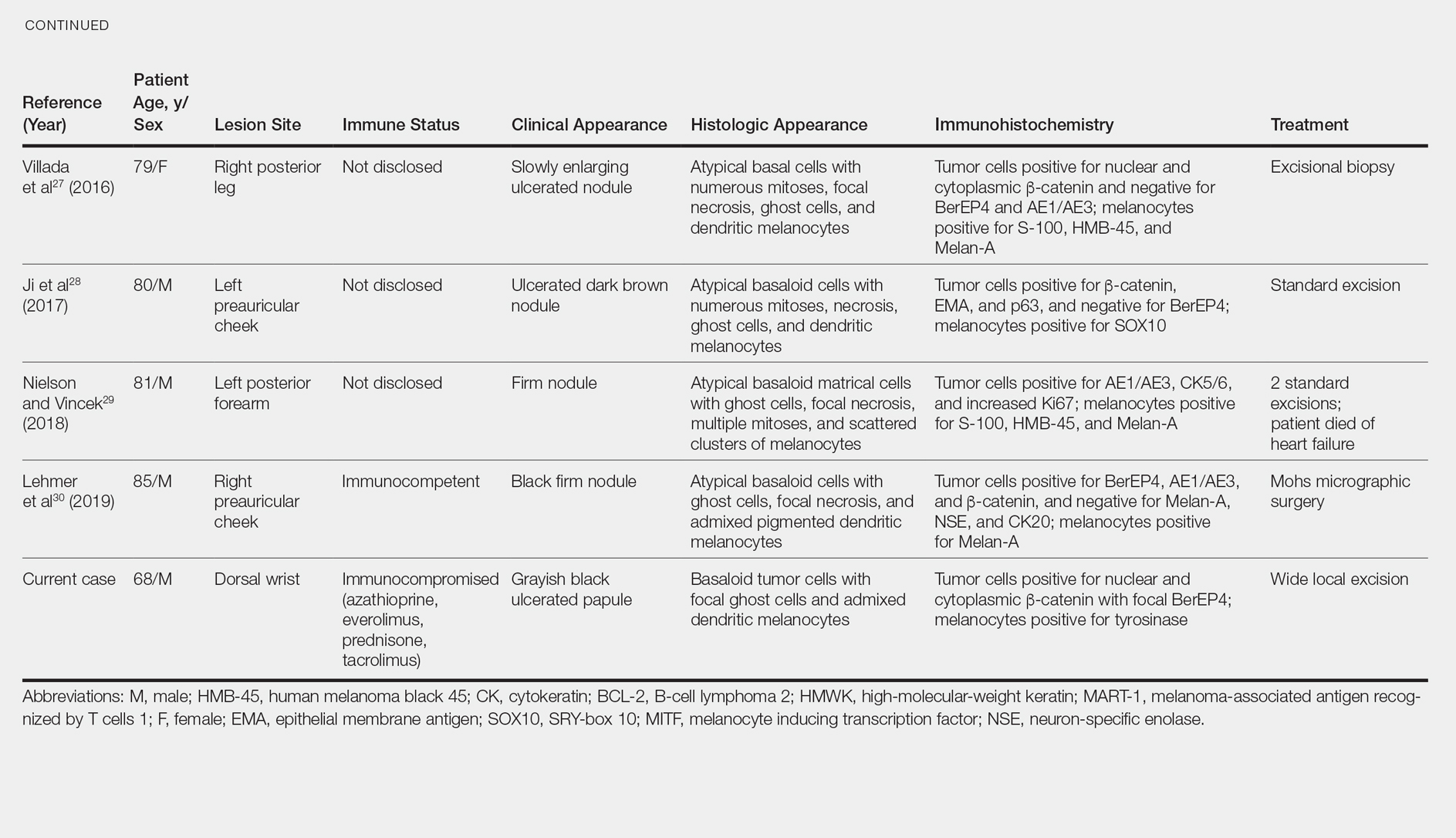

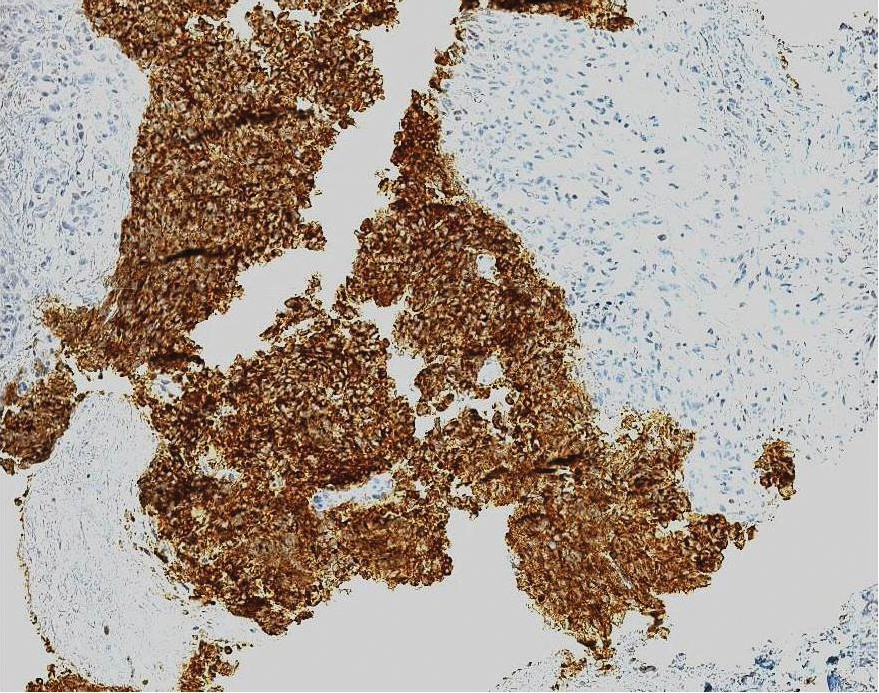

Biopsy of an EGR-like area on the leg showed a superficial perivascular and somewhat lichenoid lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 2). Lymphocytes were lined up along the basal layer, occasionally forming nests within the epidermis. Nearly all mononuclear cells in the epidermis and dermis exhibited positive CD3 and CD4 staining, with only scattered CD8 cells. These features were compatible with cutaneous involvement in SS. A concurrent biopsy from diffusely erythrodermic forearm skin, which lacked EGR-like morphology, showed similar histopathologic and immunophenotypic features.

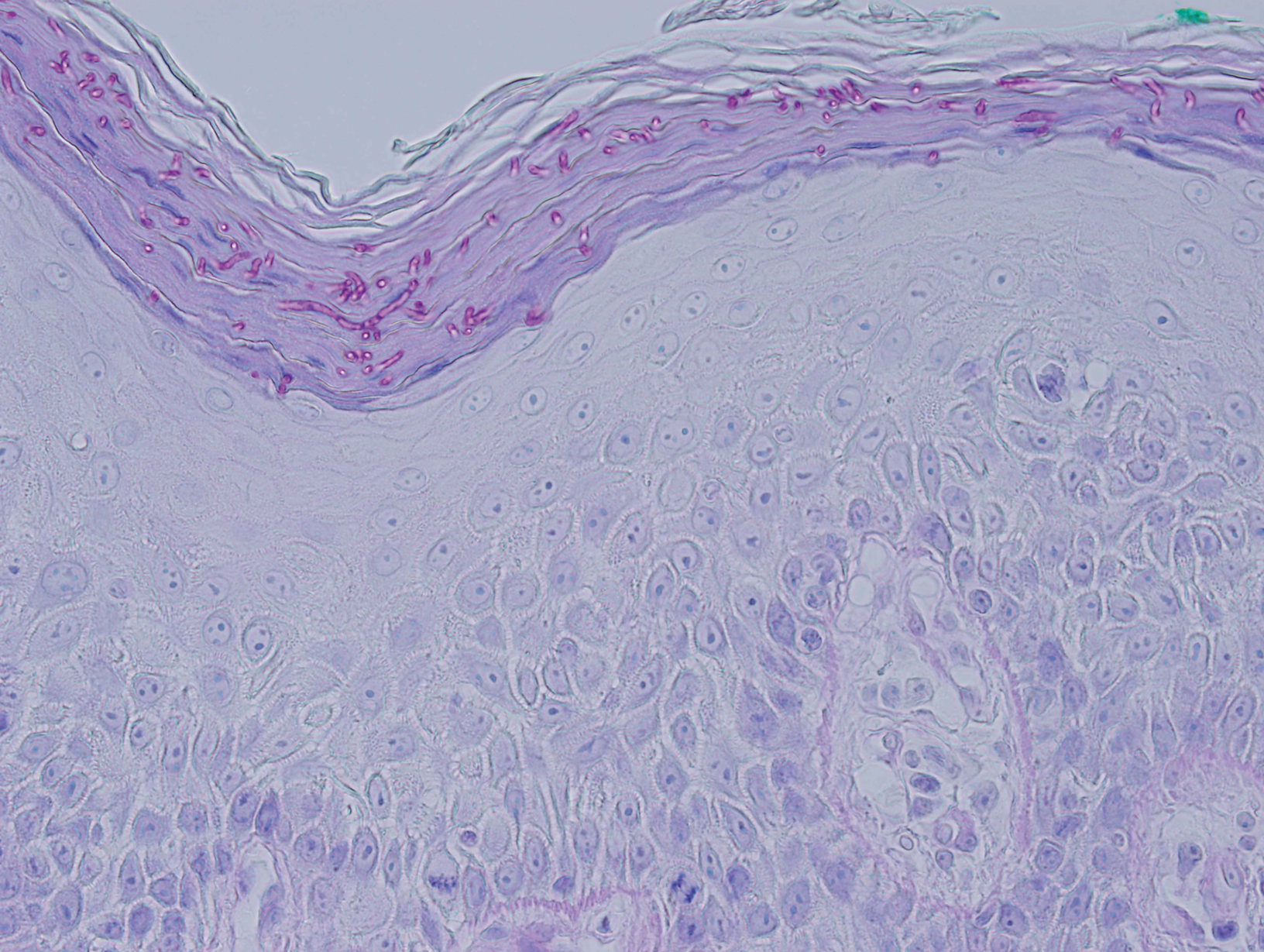

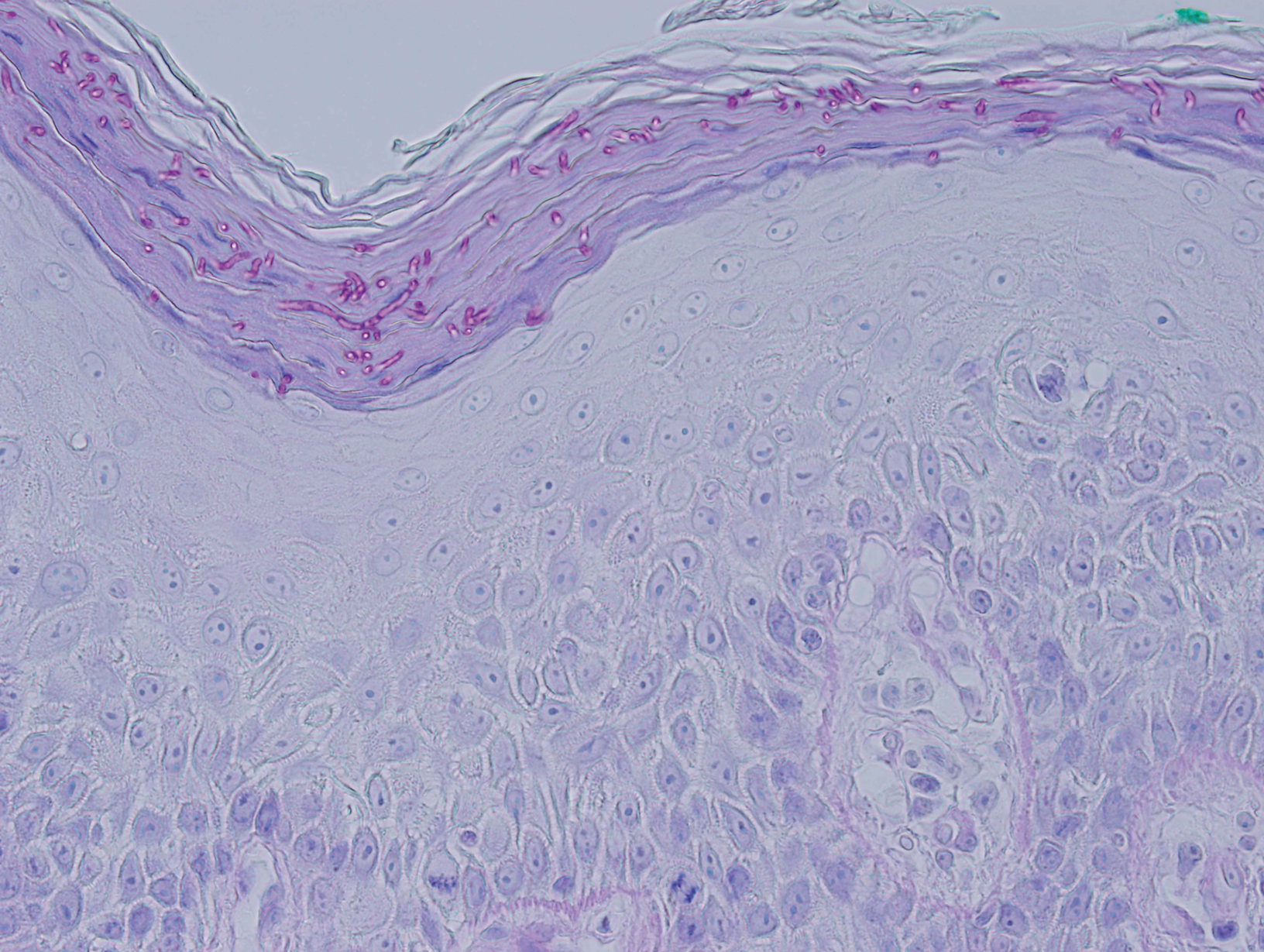

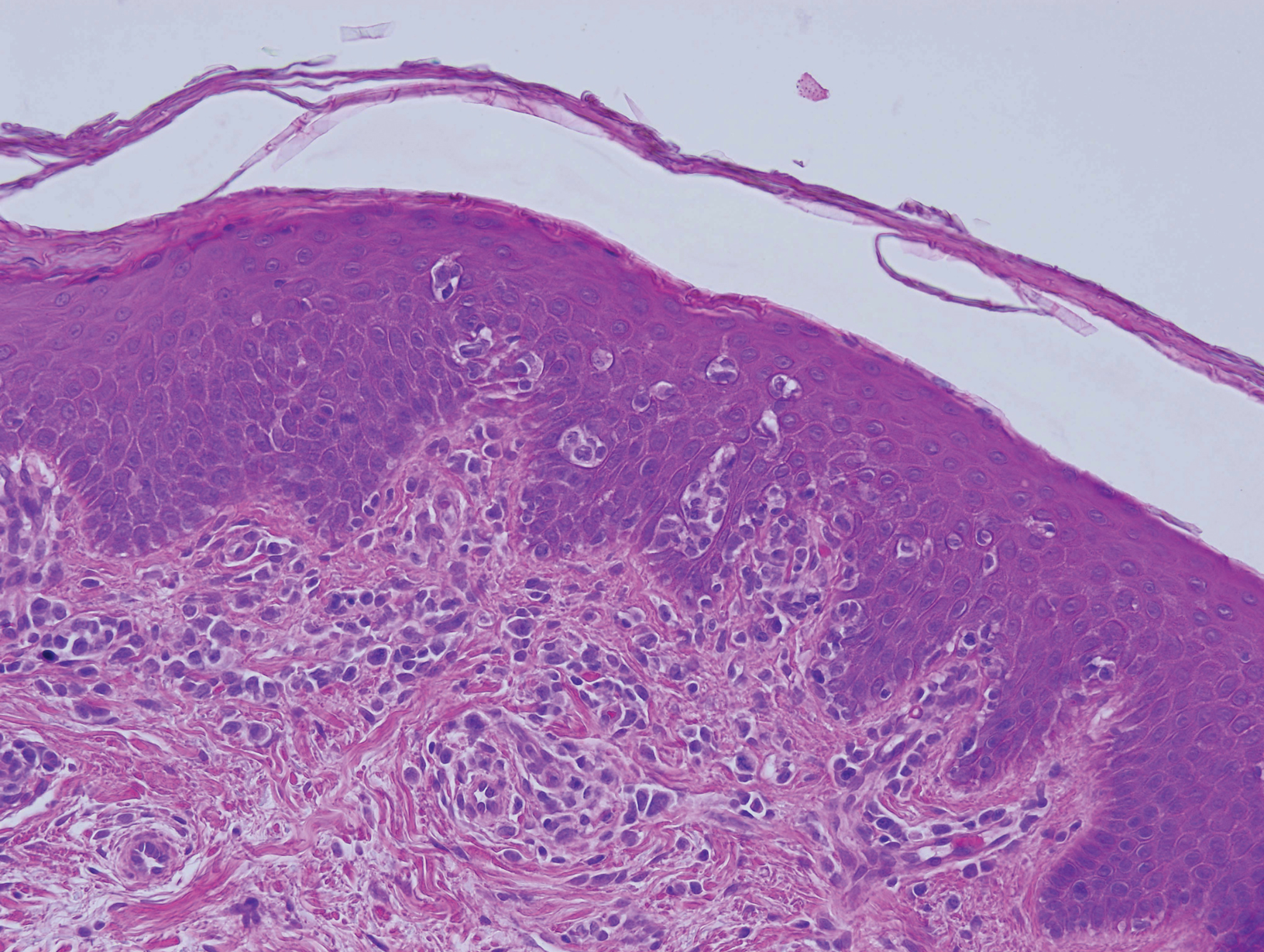

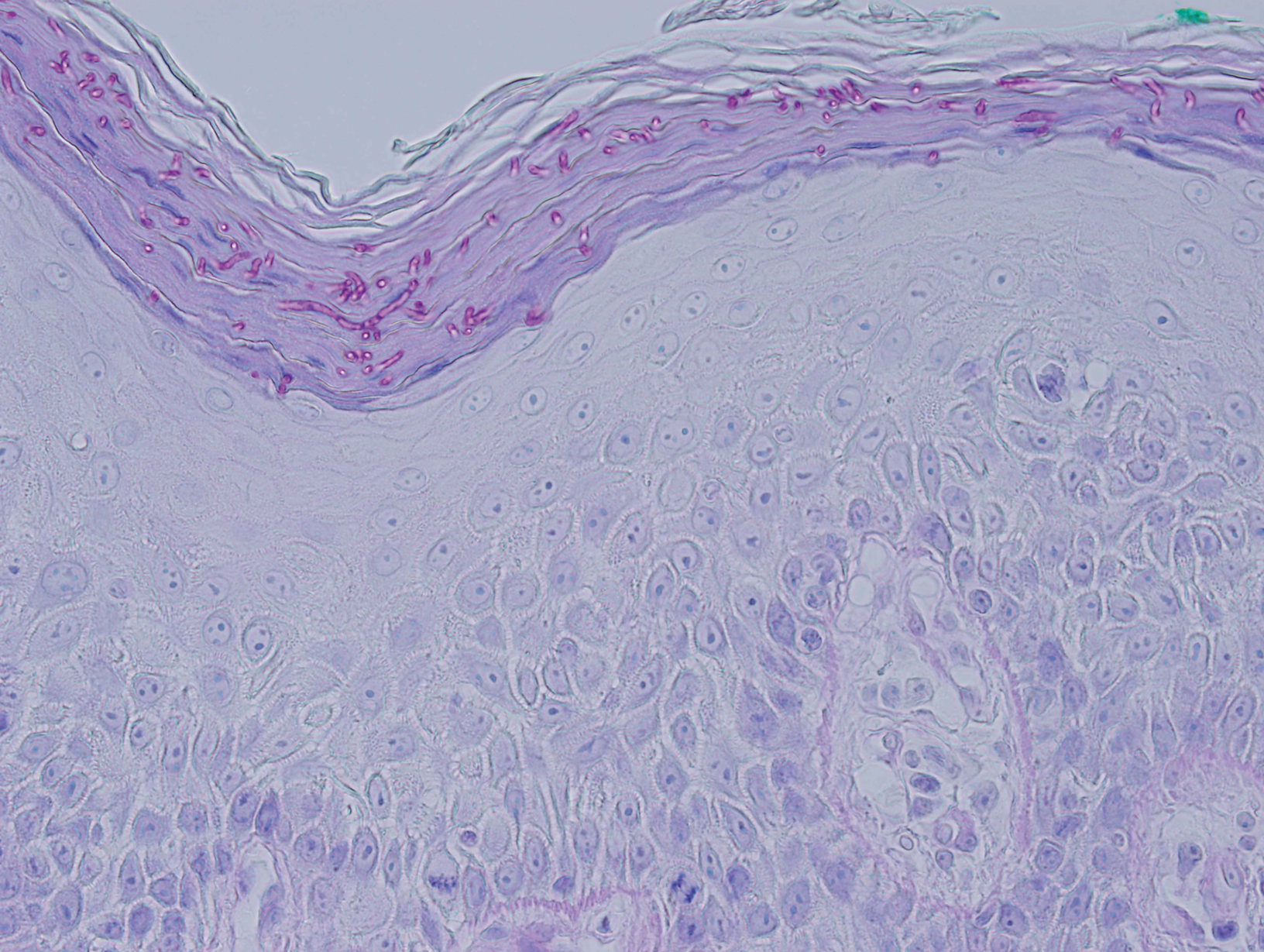

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain revealed numerous septate hyphae within the stratum corneum in both skin biopsy specimens (Figure 3). Fungal culture of EGR-like lesions was positive for a nonsporulating filamentous fungus, identified as Trichophyton rubrum by DNA sequencing.

A diagnosis of EGR-like eruption secondary to tinea corporis in SS was made. The possibility of tinea incognito also was considered to explain the presence of dermatophytes in the biopsy from skin that exhibited only erythroderma clinically; however, the patient did not have a history of corticosteroid use.

Interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate therapy was initiated. Additionally, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) was initiated for 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the EGR-like eruption; nevertheless, diffuse erythema remained. Subsequently, within 3 months of treatment, the cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) improved with continued interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate. Erythroderma became minimal; the circulating Sézary cell count decreased by 50%. The patient ultimately had multiple relapses in erythroderma and progression of SS. Erythema gyratum repens–like lesions recurred on multiple occasions, with a temporary response to repeat courses of oral terbinafine.

Comment

Defining True EGR vs EGR-like Eruption

Sézary syndrome represents the leukemic stage of CTCL, which is defined by the triad of erythroderma; generalized lymphadenopathy; and neoplastic T cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. It is well known that CTCL can mimic multiple benign and malignant dermatoses. One rare presentation of CTCL is an EGR-like eruption.

Erythema gyratum repens presents as rapidly advancing, erythematous, concentric bands that can be figurate, gyrate, or annular, with a fine trailing edge of scale (wood grain pattern). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic clinical pattern of EGR and by ruling out other mimicking conditions with biopsy.1 Patients with the characteristic clinical pattern but with an alternate underlying dermatosis are described as having an EGR-like eruption rather than true EGR.

True EGR is most often but not always associated with underlying malignancy. Biopsy of true EGR eruptions show nonspecific histopathologic features, with perivascular superficial mononuclear dermatitis, occasional mild spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis; specific features of an alternate dermatosis are lacking.2 In addition to CTCL, EGR-like eruptions have been described in a number of diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema annulare centrifugum, bullous dermatosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, urticarial vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

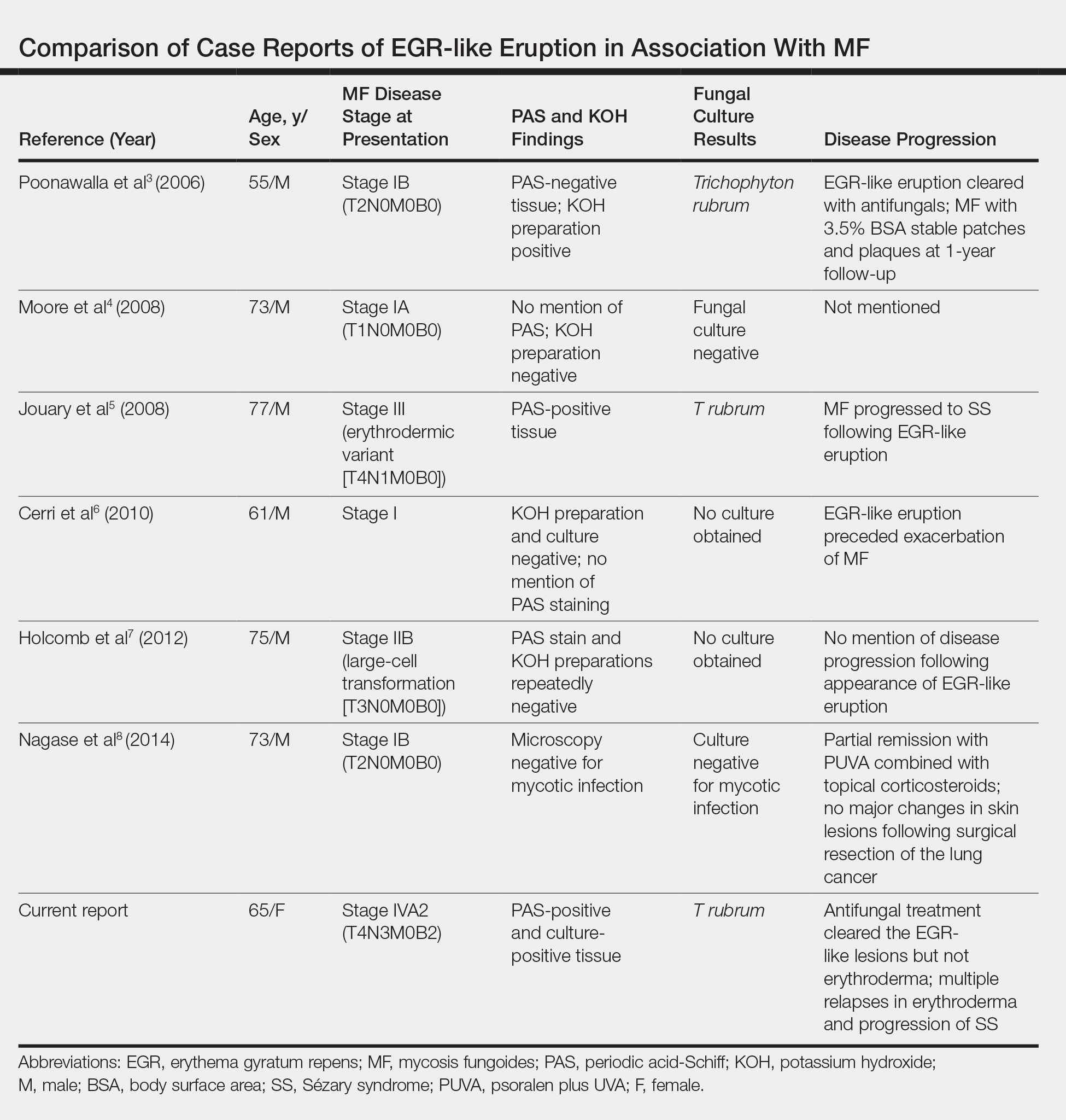

Prior Reports of EGR-like Eruption in Association With MF

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erythema gyratum repens in mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides with tinea, and concentric wood grain erythema, there have been 6 other cases of an EGR-like eruption in association with MF (Table). Poonawalla et al3 first described an EGR-like eruption (utilizing the term tinea pseudoimbricata) in a 55-year-old man with stage IB MF (T2N0M0B0). The patient had a preceding history of tinea pedis and tinea corporis that preceded the diagnosis of MF. At the time of MF diagnosis, the patient presented with extensive concentric, gyrate, wood grain, annular lesions. His MF was resistant to topical mechlorethamine, psoralen plus UVA, and oral bexarotene. The body surface area involvement decreased from 60% to less than 1% after institution of oral and topical antifungal therapy. It was postulated that the widespread dermatophytosis that preceded the development of MF may have been the persistent antigen leading to his disease. Preceding the diagnosis of MF, skin scrapings were floridly positive for dermatophyte hyphae. Fungal cultures from the affected areas of skin grew T rubrum.3

Moore et al4 described an EGR-like eruption on the trunk of a 73-year-old man with stage IA MF (T1N0M0B0). Biopsy was consistent with MF, but no fungal organisms were seen. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures of the lesions also were negative for organisms. The patient was successfully treated with topical betamethasone.4Jouary et al5 described an EGR-like eruption in a 77-year-old man with stage III erythrodermic MF (T4N1M0B0). Biopsy showed mycelia on PAS stain. Subsequent culture isolated T rubrum. Terbinafine (250 mg/d) and ketoconazole cream 2% daily were initiated and the patient’s EGR-like rash quickly cleared, while MF progressed to SS.5

Cerri et al6 later described a case of EGR-like eruption in a 61-year-old man with stage I MF and an EGR-like eruption. Microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal culture of the lesions failed to demonstrate mycotic infection. There was no mention of PAS stain of skin biopsy specimens. In this case, the authors mentioned that EGR-like lesions preceded exacerbation of MF and questioned the prognostic significance of the EGR-like eruption in relation to MF.6

Holcomb et al7 reported the next case of a 75-year-old man with stage IIB MF (T3N0M0B0) with CD25+ and CD30+ large cell transformation who presented with an EGR-like eruption. In this case, PAS stain and KOH preparations were repeatedly negative for mycotic infection. Disease progression was not mentioned following the appearance of the EGR-like eruption.7

Nagase et al8 most recently described a case of a 73-year-old Japanese man with stage IB (T2N0M0B0) CD4−CD8− MF and lung cancer who developed a cutaneous eruption mimicking EGR. Microscopy and culture excluded the presence of a mycotic infection. The patient achieved partial remission with photochemotherapy (psoralen plus UVA) combined with topical corticosteroids. No major changes in the patient’s skin lesions were noted following surgical resection of the lung cancer.8

Dermatophyte Infection

It is known that conventional tinea corporis can occur in the setting of CTCL. However, EGR-like eruptions in CTCL can be distinguished from standard tinea corporis by the classic morphology of EGR and clinical history of rapid migration of these characteristic lesions.

Tinea imbricata is known to have a clinical appearance that is similar to EGR, but the infection is caused by Tinea concentricum, which is limited to southwest Polynesia, Melanesia, Southeast Asia, India, and Central America. Although T rubrum was the dermatophyte isolated by Poonawalla et al,3 Jouary et al,5 and in our case, whether T rubrum infection in the setting of CTCL has any impact on prognosis needs further study.

Our case of an EGR-like eruption presented in a patient with SS and tinea corporis. Biopsy specimens showed CTCL and concomitant dermatophytic infection that was confirmed with PAS stain and identified as T rubrum. Interestingly, our patient’s EGR-like eruption cleared with oral terbinafine therapy, consistent with findings described by Poonawalla et al3 and Jouary et al5 in which treatment of the dermatophytic infection led to resolution of the EGR-like eruption, suggesting a causative role.

However, testing for dermatophytes was negative in the other reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in patients with MF, despite screening for the presence of fungal microorganisms using KOH preparation, PAS staining, or fungal culture, or a combination of these methods,3-8 which raises the question: Do the cases reported without dermatophytic infection represent false-negative test results, or can the distinct clinical appearance of EGR indeed be seen in patients with CTCL who lack superimposed dermatophytosis? In 3 prior reported cases of EGR-like eruptions in MF, the eruption was preceded by immunosuppressive therapy.5-7

Further investigation is needed to correlate the role of dermatophytic infection in EGR-like eruptions. Our case and the Jouary et al5 case reported dermatophyte-positive EGR-like eruptions in MF and SS detected with histopathologic analysis and PAS stain. This low-cost screening method should be considered in future cases. If the test result is dermatophyte positive, a 14-day course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) might induce resolution of the EGR-like eruption.

Conclusion

The role of dermatophyte-induced EGR or EGR-like eruptions in other settings also warrants further investigation to shed light on this poorly understood yet striking dermatologic condition. Our patient showed both MF and dermatophytes in skin biopsy results, regardless of whether those sites showed erythroderma or EGR-like features clinically. On 3 occasions, antifungal treatment cleared the EGR-like lesions and associated pruritus but not erythroderma. Therefore, it appears that the mere presence of dermatophytes was necessary but not sufficient to produce the EGR-like lesions observed in our case.

- Rongioletti F, Fausti V, Parodi A. Erythema gyratum repens is not an obligate paraneoplastic disease: a systematic review of the literature and personal experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;28:112-115.

- Albers SE, Fenske NA, Glass LF. Erythema gyratum repens: direct immunofluorescence microscopic findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:493-494.

- Poonawalla T, Chen W, Duvic M. Mycosis fungoides with tinea pseudoimbricata owing to Trichophyton rubrum infection. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:52-56.

- Moore E, McFarlane R, Olerud J. Concentric wood grain erythema on the trunk. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:673-678.

- Jouary T, Lalanne N, Stanislas S, et al. Erythema gyratum repens-like eruption in mycosis fungoides: is dermatophyte superinfection underdiagnosed in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1276-1278.

- Cerri A, Vezzoli P, Serini SM, et al. Mycosis fungoides mimicking erythema gyratum repens: an additional variant? Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:540-541.

- Holcomb M, Duvic M, Cutlan J. Erythema gyratum repens-like eruptions with large cell transformation in a patient with mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1231-1233.

- Nagase K, Shirai R, Okawa T, et al. CD4/CD8 double-negative mycosis fungoides mimicking erythema gyratum repens in a patient with underlying lung cancer. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:89-90.

Case Report

A 65-year-old woman presented with stage IVA2 mycosis fungoides (MF)(T4N3M0B2)/Sézary syndrome (SS). A peripheral blood count contained 6000 Sézary cells with cerebriform nuclei, a CD2+/−CD3+CD4+CD5+/−CD7+CD8−CD26−immunophenotype, and a highly abnormal CD4 to CD8 ratio (70:1). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography demonstrated hypermetabolic subcutaneous nodules in the base of the neck and generalized lymphadenopathy. Lymph node biopsy showed involvement by T-cell lymphoma and dominant T-cell receptor γ clonality by polymerase chain reaction.

On initial presentation to the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the patient was erythrodermic. She also was noted to have undulating wavy bands and concentric annular, ringlike, thin, erythematous plaques with trailing scale, giving a wood grain, zebra hide–like appearance involving the buttocks, abdomen, and lower extremities (Figure 1). Lesions were markedly pruritic and were advancing rapidly. A diagnosis of erythema gyratum repens (EGR)–like eruption was made.

Biopsy of an EGR-like area on the leg showed a superficial perivascular and somewhat lichenoid lymphoid infiltrate (Figure 2). Lymphocytes were lined up along the basal layer, occasionally forming nests within the epidermis. Nearly all mononuclear cells in the epidermis and dermis exhibited positive CD3 and CD4 staining, with only scattered CD8 cells. These features were compatible with cutaneous involvement in SS. A concurrent biopsy from diffusely erythrodermic forearm skin, which lacked EGR-like morphology, showed similar histopathologic and immunophenotypic features.

Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) with diastase stain revealed numerous septate hyphae within the stratum corneum in both skin biopsy specimens (Figure 3). Fungal culture of EGR-like lesions was positive for a nonsporulating filamentous fungus, identified as Trichophyton rubrum by DNA sequencing.

A diagnosis of EGR-like eruption secondary to tinea corporis in SS was made. The possibility of tinea incognito also was considered to explain the presence of dermatophytes in the biopsy from skin that exhibited only erythroderma clinically; however, the patient did not have a history of corticosteroid use.

Interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate therapy was initiated. Additionally, oral terbinafine (250 mg/d) was initiated for 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the EGR-like eruption; nevertheless, diffuse erythema remained. Subsequently, within 3 months of treatment, the cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) improved with continued interferon alfa-2b and methotrexate. Erythroderma became minimal; the circulating Sézary cell count decreased by 50%. The patient ultimately had multiple relapses in erythroderma and progression of SS. Erythema gyratum repens–like lesions recurred on multiple occasions, with a temporary response to repeat courses of oral terbinafine.

Comment

Defining True EGR vs EGR-like Eruption

Sézary syndrome represents the leukemic stage of CTCL, which is defined by the triad of erythroderma; generalized lymphadenopathy; and neoplastic T cells in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood. It is well known that CTCL can mimic multiple benign and malignant dermatoses. One rare presentation of CTCL is an EGR-like eruption.

Erythema gyratum repens presents as rapidly advancing, erythematous, concentric bands that can be figurate, gyrate, or annular, with a fine trailing edge of scale (wood grain pattern). The diagnosis is based on the characteristic clinical pattern of EGR and by ruling out other mimicking conditions with biopsy.1 Patients with the characteristic clinical pattern but with an alternate underlying dermatosis are described as having an EGR-like eruption rather than true EGR.

True EGR is most often but not always associated with underlying malignancy. Biopsy of true EGR eruptions show nonspecific histopathologic features, with perivascular superficial mononuclear dermatitis, occasional mild spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis; specific features of an alternate dermatosis are lacking.2 In addition to CTCL, EGR-like eruptions have been described in a number of diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, erythema annulare centrifugum, bullous dermatosis, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, urticarial vasculitis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and neutrophilic dermatoses.

Prior Reports of EGR-like Eruption in Association With MF

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erythema gyratum repens in mycosis fungoides, mycosis fungoides with tinea, and concentric wood grain erythema, there have been 6 other cases of an EGR-like eruption in association with MF (Table). Poonawalla et al3 first described an EGR-like eruption (utilizing the term tinea pseudoimbricata) in a 55-year-old man with stage IB MF (T2N0M0B0). The patient had a preceding history of tinea pedis and tinea corporis that preceded the diagnosis of MF. At the time of MF diagnosis, the patient presented with extensive concentric, gyrate, wood grain, annular lesions. His MF was resistant to topical mechlorethamine, psoralen plus UVA, and oral bexarotene. The body surface area involvement decreased from 60% to less than 1% after institution of oral and topical antifungal therapy. It was postulated that the widespread dermatophytosis that preceded the development of MF may have been the persistent antigen leading to his disease. Preceding the diagnosis of MF, skin scrapings were floridly positive for dermatophyte hyphae. Fungal cultures from the affected areas of skin grew T rubrum.3

Moore et al4 described an EGR-like eruption on the trunk of a 73-year-old man with stage IA MF (T1N0M0B0). Biopsy was consistent with MF, but no fungal organisms were seen. Potassium hydroxide preparation and fungal cultures of the lesions also were negative for organisms. The patient was successfully treated with topical betamethasone.4Jouary et al5 described an EGR-like eruption in a 77-year-old man with stage III erythrodermic MF (T4N1M0B0). Biopsy showed mycelia on PAS stain. Subsequent culture isolated T rubrum. Terbinafine (250 mg/d) and ketoconazole cream 2% daily were initiated and the patient’s EGR-like rash quickly cleared, while MF progressed to SS.5

Cerri et al6 later described a case of EGR-like eruption in a 61-year-old man with stage I MF and an EGR-like eruption. Microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal culture of the lesions failed to demonstrate mycotic infection. There was no mention of PAS stain of skin biopsy specimens. In this case, the authors mentioned that EGR-like lesions preceded exacerbation of MF and questioned the prognostic significance of the EGR-like eruption in relation to MF.6

Holcomb et al7 reported the next case of a 75-year-old man with stage IIB MF (T3N0M0B0) with CD25+ and CD30+ large cell transformation who presented with an EGR-like eruption. In this case, PAS stain and KOH preparations were repeatedly negative for mycotic infection. Disease progression was not mentioned following the appearance of the EGR-like eruption.7