User login

Management of Rodenticide Poisoning Associated with Synthetic Cannabinoids

Between March 7, 2018, and May 9, 2018, at least 164 people in Illinois were sickened by synthetic cannabinoids laced with rodenticides. The Illinois Department of Public Health has reported 4 deaths connected with the use of synthetic cannabinoids (sold under names such as Spice, K2, Legal Weed, etc).1 Synthetic cannabinoids are mind-altering chemicals that are sprayed on dried plant material and often sold at convenience stores. Some users have reported smoking these substances because they are generally not detected by standard urine toxicology tests.

Recreational use of synthetic cannabinoids can lead to serious and, at times, deadly complications. Chemicals found in rat poison have contaminated batches of synthetic cannabinoids, leading to coagulopathy and severe bleeding. Affected patients have reported hemoptysis, hematuria, severe epistaxis, bleeding gums, conjunctival hemorrhages, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The following case is of a patient who presented to an emergency department (ED) with severe coagulopathy and cardiotoxicity after using an adulterated synthetic cannabinoid product.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man presented to the ED reporting hematochezia, hematuria, and hemoptysis. He reported that these symptoms began about 1 day after he had smoked a synthetic cannabinoid called K2. The patient stated that some of his friends who used the same product were experiencing similar symptoms. He reported mild generalized abdominal pain but reported no chest pain, dyspnea, headache, fevers, chills, or dysuria.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lower back pain, and vitamin D deficiency. His past surgical history was notable for an exploratory laparotomy after a stab wound to the abdomen. The patient reported taking the following medications: morphine SA 30 mg bid, meloxicam 15 mg daily, amitriptyline 100 mg qhs, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg q12h prn, atorvastatin 20 mg qhs, omeprazole 20 mg qam, senna 187 mg daily prn, psyllium 1 packet dissolved in water daily prn, and cholecalciferol 1,000 IU daily.

The patient’s temperature was 98o F, blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg; pulse, 131 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and O2 saturation, 98% (ambient air). A physical examination revealed no acute distress; he was coughing up blood; clear lungs; heart sounds were tachycardic and irregularly irregular; soft, nondistended, mild generalized tenderness in the abdomen with no guarding and no rebound. The pertinent laboratory tests were international normalized ratio (INR), > 20; prothrombin time, > 150 seconds; prothrombin thromboplastin time, 157 seconds; hemoglobin, 13.3 g/dL; platelet count, 195 k/uL; white blood count, 11.3 k/uL; creatinine, 0.57mg/dL; potassium, 3.8 mmol/L, D-dimertest, 0.87 ug/mL fibrinogen equivalent units; fibrinogen level, 624 mg/dL; troponin, < 0.04 ng/mL; lactic acid, 1.3 mmol/L; total bilirubin, 0.8 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 22 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase, 22 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 89 U/L; urinalysis with > 50 red blood cells/high power field; large blood, negative leukocyte esterase, negative nitrite. The patient’s urine toxicology was negative for cannabinoids, methadone, amphetamines, cocaine, and benzodiazepines; but was positive for opiates. An anticoagulant poisoning panel also was ordered.

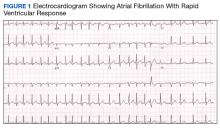

An electrocardiogram (ECG) and imaging studies were ordered. The ECG showed atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response (Figure 1). A chest X-ray indicated bibasilar consolidations that were worse on the right side. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head did not show intracranial bleeding. An abdomen/pelvis CT showed bilateral diffuse patchy peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities in the lung bases that could represent pulmonary hemorrhage, but no peritoneal or retroperitoneal bleeding.

Treatment

In the ED, the case was discussed with the Illinois Poison Control Center. The patient was diagnosed with coagulopathy likely due to anticoagulant poisoning. He was immediately treated with 10 mg of IV vitamin K, a fixed dose of 2,000 units of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate, and 4 units of fresh frozen plasma. His INR improved to 1.42 within several hours. He received 5 mg of IV metoprolol for uncontrolled AF and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further care.

In the ICU the patient was started on oral vitamin K 50 mg tid for ongoing treatment of coagulopathy due to concern for possible rodenticide poisoning associated with very long half-life. This dose was then decreased to 50 mg bid. He was given IV fluid resuscitation with normal saline and started on rate control for AF with oral metoprolol. His heart rate improved. An echocardiogram showed new cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 25% to 30%. Given basilar infiltrates and 1 episode of low-grade fever, he was started on ceftriaxone for possible community-acquired pneumonia. The patient was started on cholestyramine to help with washout of the possible rodenticide. No endoscopic interventions were performed.

The patient was transferred to an inpatient telemetry floor 24 hours after admission to the ICU once his tachycardia and bleeding improved. He did not require transfusion of packed red blood cells. In the ICU his INR had ranged between 1.62 and 2.46 (down from > 20 in the ED). His hemoglobin dropped from 13.3 g/dL on admission to 12 g/dL on transfer from the ICU, before stabilizing around 11 g/dL on the floor. The patient’s heart rate required better control, so metoprolol was increased to a total daily dose of 200 mg on the telemetry floor. Oral digoxin was then added after a digoxin load for additional rate control, as the patient remained tachycardic. Twice a day the patient continued to take 50 mg vitamin K. Cholestyramine and ceftriaxone were initially continued, but when the INR started increasing again, the cholestyramine was stopped to allow for an increase to more frequent 3-times daily vitamin 50 mg K administration (cholestyramine can interfere with vitamin K absorption). According to the toxicology service, there was only weak evidence to support use of cholestyramine in this setting.

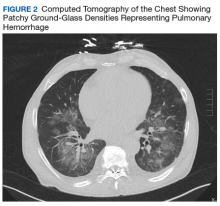

Given his ongoing mild hemoptysis, the patient received first 1 unit, and then another 4 units of FFP when the INR increased to 3.96 despite oral vitamin K. After FFP, the INR decreased to 1.93 and subsequently to 1.52. A CT of the chest showed patchy ground-glass densities throughout the lungs, predominantly at the lung bases and to a lesser extent in the upper lobes. The findings were felt to represent pulmonary hemorrhage given the patient’s history of hemoptysis (Figure 2).

The patient’s heart rate control improved, and he remained hemodynamically stable. A thyroid function test was within normal limits. Lisinopril was added to metoprolol and digoxin given his newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. The patient was observed for a total of 4 days on the inpatient floor and discharged after his INR stabilized around 1.5 on twice daily 50 mg vitamin K. The patient’s hematuria and hematochezia completely resolved, and hemoptysis was much improved at the time of discharge. His hemoglobin remained stable. The anticoagulant poisoning panel came back positive for

The patient has remained in AF at all follow-up visits. The INR normalized by 6 weeks after hospital discharge, and the dose of vitamin K slowly was tapered with close monitoring of the INR. Vitamin K was tapered for about 6 months after his initial presentation, and the patient was started on a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) for anticoagulation when the INR remained stable off vitamin K. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at direct current (DC) cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm, and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Discussion

Users generally smoke synthetic cannabinoids, which produce cannabis-like effects. However, atypical intoxication effects with worse complications often occur.2 These products typically contain dried shredded plant material that is soaked in or sprayed with several synthetic cannabinoids, varying in dosage and combination.3 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with serious adverse effects (AEs), including drowsiness, light-headedness, and fast or irregular heartbeat.4 More severe clinical features such as psychosis, delirium, cardiotoxicity, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, hyperthermia, myocardial ischemia, ischemic strokes, and death have also been noted.4

It is not known how some batches of synthetic cannabinoids came to be contaminated with rat poison or how commonly such an adulteration is found across the country. Several different guidelines provide pathways for the treatment of acute bleeding in the setting of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.5,6 Each guideline divides the indications for reversal into either severity of bleeding or the criticality of the bleeding based on location.5,6 All guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K (either oral or IV) followed by FFP or 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) for more severe bleeding.5,6 However, recommendations regarding the use of PCC vary in dosing for vitamin K antagonists (in contrast to treatment of coagulopathy due to DOACs). Recent studies and guidelines suggest that fixed-dose (rather than weight-based dose) PCC is effective for the reversal of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.6,7 Using fixed rather than weight-based dosing decreases cost and may decrease the possibility of thrombotic AEs.7 In this patient, a fixed-dose of 2,000 units of PCC was given based on data that were extrapolated from warfarin reversal using PCC.7

The vitamin K antagonists that adulterated this patient’s synthetic cannabinoid were difenacoum and brodifacoum, which are 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. These are second-generation long-acting anticoagulant rodenticides (LAARs) that are about 100 times more potent than warfarin.8 As the name implies, LAARs have a longer duration of action in the body of any organism that ingests the poison, which is due to the highly lipophilic groups that have been added to the warfarin molecule to combat resistance in rodents.9

As a result of the deposition in the tissues, there have been reports of the duration of action of brodifacoum ranging from 51 days to 9 months after ingestion, with the latter caused by an intentional overdose in a human.9-12 Reports suggest that coagulopathy is not likely to occur when the serum brodifacoum concentration is < 10 ng/mL.13,14 Animal models show difenacoum has a tissue half-life of about 62 days.15 Reports of difenacoum poisoning in humans have shown variable lengths of treatment, ranging from 30 to 47 days.16-18 The length of treatment for either brodifacoum or difenacoum will depend on the amount of poison exposure.

The long duration of action and treatment duration may lead to problems with drug procurement, especially in the early phase of treatment in which IV vitamin K is used. The supply of IV vitamin K recently has been limited for at least some manufacturers. According to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists Current Drug Shortage List, the increased demand is thought to be due to increased use of synthetic inhaled cannabinoids laced with anticoagulant.19 IV vitamin K products are available from suppliers such as Amphastar (Rancho Cucamonga, CA) and Hospira (Lake Forest, IL).

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends IV vitamin K administration in patients with major bleeding secondary to vitamin K antagonists.20 The oral route is thought to be more effective than a subcutaneous route in the treatment of nonbleeding patients with rodenticide-associated coagulopathy. Due to erratic and unpredictable absorption, the subcutaneous route of administration has fallen out of favor. Oral vitamin K products were not affected by the recent shortage. However, large doses of oral vitamin K can be costly. Due to the long half-life of LAAR, many patients are discharged with a prescription for oral vitamin K. Although vitamin K is found in most over-the-counter (OTC) multivitamins, the strength is insufficient. Most OTC formulations are ≤ 100 μg, whereas the prescription strength is 5 mg, but patients being treated for rodenticide poisoning require much larger doses.

Commercial insurance carriers and Medicare Part D usually do not cover vitamins and minerals unless it is for a medically accepted indication or is an indication supported by citation in either the American Hospital Formulary System, United States Pharmacopeia drug information book, or an electronic information resource that is supported by evidence such as Micromedex.21 For a patient without insurance coverage being treated with high-dose vitamin K therapy for rodenticide poisoning outside of a federal health care system, the cost could be as high as $500 to $1,000 per day, depending on the dose of vitamin K needed to maintain an acceptable INR.

Conclusion

In addition to bleeding as a result of coagulopathy, this patient presented with new onset of AF with rapid ventricular response and a newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. Although the patient had other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and a remote history of cocaine use, it is likely that the use of the synthetic cannabinoids contributed to the development and/or worsening of this arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in AF 6 weeks after hospital discharge with a controlled ventricular rate on metoprolol and digoxin. An interval echocardiogram 6 weeks after hospital discharge showed a recovered ejection fraction. In cases of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, the ejection fraction often recovers with control of the tachycardia. The patient was weaned off vitamin K about 6 months after his initial presentation and started on a DOAC for anticoagulation. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at DC cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Although unclear how synthetic cannabinoids became adulterated with a potent vitamin K antagonist, health care practitioners should consider this if a patient presents with unexplained coagulopathy and widespread bleeding. Fixed-dose PCC should be considered as an alternative to weight-based dosing in these cases. Physicians and pharmacy personnel should anticipate a need for long-term high doses of vitamin K in order to begin work early to obtain sufficient supplies to treat presenting patients.

1. Illinois Department of Public Health. Synthetic cannabinoids. http://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/prevention-wellness/medical-cannabis/synthetic-cannabinoids. Updated May 30, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

2. Tournebize J, Gibaja V, Kahn JP. Acute effects of synthetic cannabinoids: update 2015. Subst Abus. 2017;38(3):344-366.

3. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global SMART update. https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Global_SMART_Update_13_web.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed April 8, 2019.

4. Adams AJ, Banister SD, Irizarry L, Trecki J, Schwartz M, Gerona R, “Zombie” outbreak caused by the synthetic cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):235-242.

5. Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on management of bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulants: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):3042-3067.

6. Cushman M, Lim W, Zakai NA. 2011 Clinical Practice guide on anticoagulant dosing and management of anticoagulant-associated bleeding complications in adults. http://www.hematology.org/Clinicians/Guidelines-Quality/Quick-Ref/525.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2019.

7. Klein L, Peters J, Miner J, Gorlin J. Evaluation of fixed dose 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate for emergent warfarin reversal. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1213-1218.

8. Bachmann KA, Sullivan TJ. Dispositional and pharmacodynamic characteristics of brodifacoum in warfarin-sensitive rats. Pharmacology. 1983;27(5):281-288.

9. Lipton RA, Klass EM. Human ingestion of ‘superwarfarin’ rodenticide resulting in a prolonged anticoagulant effect. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3004-3005.

10. Chong LL, Chau WK, Ho CH. A case of ‘superwarfarin’ poisoning. Scand J Haematol. 1986;36(3):314-331.

11. Jones EC, Growe GH, Naiman SC. Prolonged anticoagulation in rat poisoning. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3005-3007.

12. Babcock J, Hartman K, Pedersen A, Murphy M, Alving B. Rodenticide-induced coagulopathy in a young child. A case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;15(1):126-130.

13. Hollinger BR, Pastoor TP. Case management and plasma half-life in a case of brodifacoum poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1925-1928.

14. Bruno GR, Howland MA, McMeeking A, Hoffman RS. Long-acting anticoagulant overdose: brodifacoum kinetics and optimal vitamin K dosing. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(3):262-267.

15. Vandenbrouke V, Bousquet-Meloua A, De Backer P, Croubels S. Pharmacokinetics of eight anticoagulant rodenticides in mice after single oral administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(5):437-445.

16. Barlow AM, Gay AL, Park BK. Difenacoum (Neosorexa) poisoning. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285(6341):541.

17. Katona B, Wason S. Superwarfarin poisoning. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):627-631.

18. Butcher GP, Shearer MJ, MacNicoll AD, Kelly MJ, Ind PW. Difenacoum poisoning as a cause of haematuria. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1992;11(6):553-554.

19. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Current drug shortages. Vitamin K (phytonadione) injection. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/Drug-Shortage-Detail.aspx?id=100. Updated July 5, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

20. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e152S-e184S.

21. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Part D Excluded Drugs. https://www.medicareadvocacy.org/old-site/News/Archives/PartD_ExcludedDrugsByState.htm. Accessed on August 23, 2018.

Between March 7, 2018, and May 9, 2018, at least 164 people in Illinois were sickened by synthetic cannabinoids laced with rodenticides. The Illinois Department of Public Health has reported 4 deaths connected with the use of synthetic cannabinoids (sold under names such as Spice, K2, Legal Weed, etc).1 Synthetic cannabinoids are mind-altering chemicals that are sprayed on dried plant material and often sold at convenience stores. Some users have reported smoking these substances because they are generally not detected by standard urine toxicology tests.

Recreational use of synthetic cannabinoids can lead to serious and, at times, deadly complications. Chemicals found in rat poison have contaminated batches of synthetic cannabinoids, leading to coagulopathy and severe bleeding. Affected patients have reported hemoptysis, hematuria, severe epistaxis, bleeding gums, conjunctival hemorrhages, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The following case is of a patient who presented to an emergency department (ED) with severe coagulopathy and cardiotoxicity after using an adulterated synthetic cannabinoid product.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man presented to the ED reporting hematochezia, hematuria, and hemoptysis. He reported that these symptoms began about 1 day after he had smoked a synthetic cannabinoid called K2. The patient stated that some of his friends who used the same product were experiencing similar symptoms. He reported mild generalized abdominal pain but reported no chest pain, dyspnea, headache, fevers, chills, or dysuria.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lower back pain, and vitamin D deficiency. His past surgical history was notable for an exploratory laparotomy after a stab wound to the abdomen. The patient reported taking the following medications: morphine SA 30 mg bid, meloxicam 15 mg daily, amitriptyline 100 mg qhs, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg q12h prn, atorvastatin 20 mg qhs, omeprazole 20 mg qam, senna 187 mg daily prn, psyllium 1 packet dissolved in water daily prn, and cholecalciferol 1,000 IU daily.

The patient’s temperature was 98o F, blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg; pulse, 131 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and O2 saturation, 98% (ambient air). A physical examination revealed no acute distress; he was coughing up blood; clear lungs; heart sounds were tachycardic and irregularly irregular; soft, nondistended, mild generalized tenderness in the abdomen with no guarding and no rebound. The pertinent laboratory tests were international normalized ratio (INR), > 20; prothrombin time, > 150 seconds; prothrombin thromboplastin time, 157 seconds; hemoglobin, 13.3 g/dL; platelet count, 195 k/uL; white blood count, 11.3 k/uL; creatinine, 0.57mg/dL; potassium, 3.8 mmol/L, D-dimertest, 0.87 ug/mL fibrinogen equivalent units; fibrinogen level, 624 mg/dL; troponin, < 0.04 ng/mL; lactic acid, 1.3 mmol/L; total bilirubin, 0.8 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 22 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase, 22 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 89 U/L; urinalysis with > 50 red blood cells/high power field; large blood, negative leukocyte esterase, negative nitrite. The patient’s urine toxicology was negative for cannabinoids, methadone, amphetamines, cocaine, and benzodiazepines; but was positive for opiates. An anticoagulant poisoning panel also was ordered.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) and imaging studies were ordered. The ECG showed atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response (Figure 1). A chest X-ray indicated bibasilar consolidations that were worse on the right side. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head did not show intracranial bleeding. An abdomen/pelvis CT showed bilateral diffuse patchy peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities in the lung bases that could represent pulmonary hemorrhage, but no peritoneal or retroperitoneal bleeding.

Treatment

In the ED, the case was discussed with the Illinois Poison Control Center. The patient was diagnosed with coagulopathy likely due to anticoagulant poisoning. He was immediately treated with 10 mg of IV vitamin K, a fixed dose of 2,000 units of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate, and 4 units of fresh frozen plasma. His INR improved to 1.42 within several hours. He received 5 mg of IV metoprolol for uncontrolled AF and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further care.

In the ICU the patient was started on oral vitamin K 50 mg tid for ongoing treatment of coagulopathy due to concern for possible rodenticide poisoning associated with very long half-life. This dose was then decreased to 50 mg bid. He was given IV fluid resuscitation with normal saline and started on rate control for AF with oral metoprolol. His heart rate improved. An echocardiogram showed new cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 25% to 30%. Given basilar infiltrates and 1 episode of low-grade fever, he was started on ceftriaxone for possible community-acquired pneumonia. The patient was started on cholestyramine to help with washout of the possible rodenticide. No endoscopic interventions were performed.

The patient was transferred to an inpatient telemetry floor 24 hours after admission to the ICU once his tachycardia and bleeding improved. He did not require transfusion of packed red blood cells. In the ICU his INR had ranged between 1.62 and 2.46 (down from > 20 in the ED). His hemoglobin dropped from 13.3 g/dL on admission to 12 g/dL on transfer from the ICU, before stabilizing around 11 g/dL on the floor. The patient’s heart rate required better control, so metoprolol was increased to a total daily dose of 200 mg on the telemetry floor. Oral digoxin was then added after a digoxin load for additional rate control, as the patient remained tachycardic. Twice a day the patient continued to take 50 mg vitamin K. Cholestyramine and ceftriaxone were initially continued, but when the INR started increasing again, the cholestyramine was stopped to allow for an increase to more frequent 3-times daily vitamin 50 mg K administration (cholestyramine can interfere with vitamin K absorption). According to the toxicology service, there was only weak evidence to support use of cholestyramine in this setting.

Given his ongoing mild hemoptysis, the patient received first 1 unit, and then another 4 units of FFP when the INR increased to 3.96 despite oral vitamin K. After FFP, the INR decreased to 1.93 and subsequently to 1.52. A CT of the chest showed patchy ground-glass densities throughout the lungs, predominantly at the lung bases and to a lesser extent in the upper lobes. The findings were felt to represent pulmonary hemorrhage given the patient’s history of hemoptysis (Figure 2).

The patient’s heart rate control improved, and he remained hemodynamically stable. A thyroid function test was within normal limits. Lisinopril was added to metoprolol and digoxin given his newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. The patient was observed for a total of 4 days on the inpatient floor and discharged after his INR stabilized around 1.5 on twice daily 50 mg vitamin K. The patient’s hematuria and hematochezia completely resolved, and hemoptysis was much improved at the time of discharge. His hemoglobin remained stable. The anticoagulant poisoning panel came back positive for

The patient has remained in AF at all follow-up visits. The INR normalized by 6 weeks after hospital discharge, and the dose of vitamin K slowly was tapered with close monitoring of the INR. Vitamin K was tapered for about 6 months after his initial presentation, and the patient was started on a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) for anticoagulation when the INR remained stable off vitamin K. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at direct current (DC) cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm, and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Discussion

Users generally smoke synthetic cannabinoids, which produce cannabis-like effects. However, atypical intoxication effects with worse complications often occur.2 These products typically contain dried shredded plant material that is soaked in or sprayed with several synthetic cannabinoids, varying in dosage and combination.3 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with serious adverse effects (AEs), including drowsiness, light-headedness, and fast or irregular heartbeat.4 More severe clinical features such as psychosis, delirium, cardiotoxicity, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, hyperthermia, myocardial ischemia, ischemic strokes, and death have also been noted.4

It is not known how some batches of synthetic cannabinoids came to be contaminated with rat poison or how commonly such an adulteration is found across the country. Several different guidelines provide pathways for the treatment of acute bleeding in the setting of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.5,6 Each guideline divides the indications for reversal into either severity of bleeding or the criticality of the bleeding based on location.5,6 All guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K (either oral or IV) followed by FFP or 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) for more severe bleeding.5,6 However, recommendations regarding the use of PCC vary in dosing for vitamin K antagonists (in contrast to treatment of coagulopathy due to DOACs). Recent studies and guidelines suggest that fixed-dose (rather than weight-based dose) PCC is effective for the reversal of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.6,7 Using fixed rather than weight-based dosing decreases cost and may decrease the possibility of thrombotic AEs.7 In this patient, a fixed-dose of 2,000 units of PCC was given based on data that were extrapolated from warfarin reversal using PCC.7

The vitamin K antagonists that adulterated this patient’s synthetic cannabinoid were difenacoum and brodifacoum, which are 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. These are second-generation long-acting anticoagulant rodenticides (LAARs) that are about 100 times more potent than warfarin.8 As the name implies, LAARs have a longer duration of action in the body of any organism that ingests the poison, which is due to the highly lipophilic groups that have been added to the warfarin molecule to combat resistance in rodents.9

As a result of the deposition in the tissues, there have been reports of the duration of action of brodifacoum ranging from 51 days to 9 months after ingestion, with the latter caused by an intentional overdose in a human.9-12 Reports suggest that coagulopathy is not likely to occur when the serum brodifacoum concentration is < 10 ng/mL.13,14 Animal models show difenacoum has a tissue half-life of about 62 days.15 Reports of difenacoum poisoning in humans have shown variable lengths of treatment, ranging from 30 to 47 days.16-18 The length of treatment for either brodifacoum or difenacoum will depend on the amount of poison exposure.

The long duration of action and treatment duration may lead to problems with drug procurement, especially in the early phase of treatment in which IV vitamin K is used. The supply of IV vitamin K recently has been limited for at least some manufacturers. According to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists Current Drug Shortage List, the increased demand is thought to be due to increased use of synthetic inhaled cannabinoids laced with anticoagulant.19 IV vitamin K products are available from suppliers such as Amphastar (Rancho Cucamonga, CA) and Hospira (Lake Forest, IL).

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends IV vitamin K administration in patients with major bleeding secondary to vitamin K antagonists.20 The oral route is thought to be more effective than a subcutaneous route in the treatment of nonbleeding patients with rodenticide-associated coagulopathy. Due to erratic and unpredictable absorption, the subcutaneous route of administration has fallen out of favor. Oral vitamin K products were not affected by the recent shortage. However, large doses of oral vitamin K can be costly. Due to the long half-life of LAAR, many patients are discharged with a prescription for oral vitamin K. Although vitamin K is found in most over-the-counter (OTC) multivitamins, the strength is insufficient. Most OTC formulations are ≤ 100 μg, whereas the prescription strength is 5 mg, but patients being treated for rodenticide poisoning require much larger doses.

Commercial insurance carriers and Medicare Part D usually do not cover vitamins and minerals unless it is for a medically accepted indication or is an indication supported by citation in either the American Hospital Formulary System, United States Pharmacopeia drug information book, or an electronic information resource that is supported by evidence such as Micromedex.21 For a patient without insurance coverage being treated with high-dose vitamin K therapy for rodenticide poisoning outside of a federal health care system, the cost could be as high as $500 to $1,000 per day, depending on the dose of vitamin K needed to maintain an acceptable INR.

Conclusion

In addition to bleeding as a result of coagulopathy, this patient presented with new onset of AF with rapid ventricular response and a newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. Although the patient had other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and a remote history of cocaine use, it is likely that the use of the synthetic cannabinoids contributed to the development and/or worsening of this arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in AF 6 weeks after hospital discharge with a controlled ventricular rate on metoprolol and digoxin. An interval echocardiogram 6 weeks after hospital discharge showed a recovered ejection fraction. In cases of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, the ejection fraction often recovers with control of the tachycardia. The patient was weaned off vitamin K about 6 months after his initial presentation and started on a DOAC for anticoagulation. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at DC cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Although unclear how synthetic cannabinoids became adulterated with a potent vitamin K antagonist, health care practitioners should consider this if a patient presents with unexplained coagulopathy and widespread bleeding. Fixed-dose PCC should be considered as an alternative to weight-based dosing in these cases. Physicians and pharmacy personnel should anticipate a need for long-term high doses of vitamin K in order to begin work early to obtain sufficient supplies to treat presenting patients.

Between March 7, 2018, and May 9, 2018, at least 164 people in Illinois were sickened by synthetic cannabinoids laced with rodenticides. The Illinois Department of Public Health has reported 4 deaths connected with the use of synthetic cannabinoids (sold under names such as Spice, K2, Legal Weed, etc).1 Synthetic cannabinoids are mind-altering chemicals that are sprayed on dried plant material and often sold at convenience stores. Some users have reported smoking these substances because they are generally not detected by standard urine toxicology tests.

Recreational use of synthetic cannabinoids can lead to serious and, at times, deadly complications. Chemicals found in rat poison have contaminated batches of synthetic cannabinoids, leading to coagulopathy and severe bleeding. Affected patients have reported hemoptysis, hematuria, severe epistaxis, bleeding gums, conjunctival hemorrhages, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The following case is of a patient who presented to an emergency department (ED) with severe coagulopathy and cardiotoxicity after using an adulterated synthetic cannabinoid product.

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old man presented to the ED reporting hematochezia, hematuria, and hemoptysis. He reported that these symptoms began about 1 day after he had smoked a synthetic cannabinoid called K2. The patient stated that some of his friends who used the same product were experiencing similar symptoms. He reported mild generalized abdominal pain but reported no chest pain, dyspnea, headache, fevers, chills, or dysuria.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic lower back pain, and vitamin D deficiency. His past surgical history was notable for an exploratory laparotomy after a stab wound to the abdomen. The patient reported taking the following medications: morphine SA 30 mg bid, meloxicam 15 mg daily, amitriptyline 100 mg qhs, amlodipine 5 mg daily, hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg q12h prn, atorvastatin 20 mg qhs, omeprazole 20 mg qam, senna 187 mg daily prn, psyllium 1 packet dissolved in water daily prn, and cholecalciferol 1,000 IU daily.

The patient’s temperature was 98o F, blood pressure, 144/80 mm Hg; pulse, 131 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute; and O2 saturation, 98% (ambient air). A physical examination revealed no acute distress; he was coughing up blood; clear lungs; heart sounds were tachycardic and irregularly irregular; soft, nondistended, mild generalized tenderness in the abdomen with no guarding and no rebound. The pertinent laboratory tests were international normalized ratio (INR), > 20; prothrombin time, > 150 seconds; prothrombin thromboplastin time, 157 seconds; hemoglobin, 13.3 g/dL; platelet count, 195 k/uL; white blood count, 11.3 k/uL; creatinine, 0.57mg/dL; potassium, 3.8 mmol/L, D-dimertest, 0.87 ug/mL fibrinogen equivalent units; fibrinogen level, 624 mg/dL; troponin, < 0.04 ng/mL; lactic acid, 1.3 mmol/L; total bilirubin, 0.8 mg/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 22 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase, 22 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 89 U/L; urinalysis with > 50 red blood cells/high power field; large blood, negative leukocyte esterase, negative nitrite. The patient’s urine toxicology was negative for cannabinoids, methadone, amphetamines, cocaine, and benzodiazepines; but was positive for opiates. An anticoagulant poisoning panel also was ordered.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) and imaging studies were ordered. The ECG showed atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response (Figure 1). A chest X-ray indicated bibasilar consolidations that were worse on the right side. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) of the head did not show intracranial bleeding. An abdomen/pelvis CT showed bilateral diffuse patchy peribronchovascular ground-glass opacities in the lung bases that could represent pulmonary hemorrhage, but no peritoneal or retroperitoneal bleeding.

Treatment

In the ED, the case was discussed with the Illinois Poison Control Center. The patient was diagnosed with coagulopathy likely due to anticoagulant poisoning. He was immediately treated with 10 mg of IV vitamin K, a fixed dose of 2,000 units of 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate, and 4 units of fresh frozen plasma. His INR improved to 1.42 within several hours. He received 5 mg of IV metoprolol for uncontrolled AF and was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further care.

In the ICU the patient was started on oral vitamin K 50 mg tid for ongoing treatment of coagulopathy due to concern for possible rodenticide poisoning associated with very long half-life. This dose was then decreased to 50 mg bid. He was given IV fluid resuscitation with normal saline and started on rate control for AF with oral metoprolol. His heart rate improved. An echocardiogram showed new cardiomyopathy with an ejection fraction of 25% to 30%. Given basilar infiltrates and 1 episode of low-grade fever, he was started on ceftriaxone for possible community-acquired pneumonia. The patient was started on cholestyramine to help with washout of the possible rodenticide. No endoscopic interventions were performed.

The patient was transferred to an inpatient telemetry floor 24 hours after admission to the ICU once his tachycardia and bleeding improved. He did not require transfusion of packed red blood cells. In the ICU his INR had ranged between 1.62 and 2.46 (down from > 20 in the ED). His hemoglobin dropped from 13.3 g/dL on admission to 12 g/dL on transfer from the ICU, before stabilizing around 11 g/dL on the floor. The patient’s heart rate required better control, so metoprolol was increased to a total daily dose of 200 mg on the telemetry floor. Oral digoxin was then added after a digoxin load for additional rate control, as the patient remained tachycardic. Twice a day the patient continued to take 50 mg vitamin K. Cholestyramine and ceftriaxone were initially continued, but when the INR started increasing again, the cholestyramine was stopped to allow for an increase to more frequent 3-times daily vitamin 50 mg K administration (cholestyramine can interfere with vitamin K absorption). According to the toxicology service, there was only weak evidence to support use of cholestyramine in this setting.

Given his ongoing mild hemoptysis, the patient received first 1 unit, and then another 4 units of FFP when the INR increased to 3.96 despite oral vitamin K. After FFP, the INR decreased to 1.93 and subsequently to 1.52. A CT of the chest showed patchy ground-glass densities throughout the lungs, predominantly at the lung bases and to a lesser extent in the upper lobes. The findings were felt to represent pulmonary hemorrhage given the patient’s history of hemoptysis (Figure 2).

The patient’s heart rate control improved, and he remained hemodynamically stable. A thyroid function test was within normal limits. Lisinopril was added to metoprolol and digoxin given his newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. The patient was observed for a total of 4 days on the inpatient floor and discharged after his INR stabilized around 1.5 on twice daily 50 mg vitamin K. The patient’s hematuria and hematochezia completely resolved, and hemoptysis was much improved at the time of discharge. His hemoglobin remained stable. The anticoagulant poisoning panel came back positive for

The patient has remained in AF at all follow-up visits. The INR normalized by 6 weeks after hospital discharge, and the dose of vitamin K slowly was tapered with close monitoring of the INR. Vitamin K was tapered for about 6 months after his initial presentation, and the patient was started on a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) for anticoagulation when the INR remained stable off vitamin K. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at direct current (DC) cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm, and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Discussion

Users generally smoke synthetic cannabinoids, which produce cannabis-like effects. However, atypical intoxication effects with worse complications often occur.2 These products typically contain dried shredded plant material that is soaked in or sprayed with several synthetic cannabinoids, varying in dosage and combination.3 Synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with serious adverse effects (AEs), including drowsiness, light-headedness, and fast or irregular heartbeat.4 More severe clinical features such as psychosis, delirium, cardiotoxicity, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, hyperthermia, myocardial ischemia, ischemic strokes, and death have also been noted.4

It is not known how some batches of synthetic cannabinoids came to be contaminated with rat poison or how commonly such an adulteration is found across the country. Several different guidelines provide pathways for the treatment of acute bleeding in the setting of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.5,6 Each guideline divides the indications for reversal into either severity of bleeding or the criticality of the bleeding based on location.5,6 All guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K (either oral or IV) followed by FFP or 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) for more severe bleeding.5,6 However, recommendations regarding the use of PCC vary in dosing for vitamin K antagonists (in contrast to treatment of coagulopathy due to DOACs). Recent studies and guidelines suggest that fixed-dose (rather than weight-based dose) PCC is effective for the reversal of coagulopathy due to vitamin K antagonists.6,7 Using fixed rather than weight-based dosing decreases cost and may decrease the possibility of thrombotic AEs.7 In this patient, a fixed-dose of 2,000 units of PCC was given based on data that were extrapolated from warfarin reversal using PCC.7

The vitamin K antagonists that adulterated this patient’s synthetic cannabinoid were difenacoum and brodifacoum, which are 4-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. These are second-generation long-acting anticoagulant rodenticides (LAARs) that are about 100 times more potent than warfarin.8 As the name implies, LAARs have a longer duration of action in the body of any organism that ingests the poison, which is due to the highly lipophilic groups that have been added to the warfarin molecule to combat resistance in rodents.9

As a result of the deposition in the tissues, there have been reports of the duration of action of brodifacoum ranging from 51 days to 9 months after ingestion, with the latter caused by an intentional overdose in a human.9-12 Reports suggest that coagulopathy is not likely to occur when the serum brodifacoum concentration is < 10 ng/mL.13,14 Animal models show difenacoum has a tissue half-life of about 62 days.15 Reports of difenacoum poisoning in humans have shown variable lengths of treatment, ranging from 30 to 47 days.16-18 The length of treatment for either brodifacoum or difenacoum will depend on the amount of poison exposure.

The long duration of action and treatment duration may lead to problems with drug procurement, especially in the early phase of treatment in which IV vitamin K is used. The supply of IV vitamin K recently has been limited for at least some manufacturers. According to the American Society of Health System Pharmacists Current Drug Shortage List, the increased demand is thought to be due to increased use of synthetic inhaled cannabinoids laced with anticoagulant.19 IV vitamin K products are available from suppliers such as Amphastar (Rancho Cucamonga, CA) and Hospira (Lake Forest, IL).

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends IV vitamin K administration in patients with major bleeding secondary to vitamin K antagonists.20 The oral route is thought to be more effective than a subcutaneous route in the treatment of nonbleeding patients with rodenticide-associated coagulopathy. Due to erratic and unpredictable absorption, the subcutaneous route of administration has fallen out of favor. Oral vitamin K products were not affected by the recent shortage. However, large doses of oral vitamin K can be costly. Due to the long half-life of LAAR, many patients are discharged with a prescription for oral vitamin K. Although vitamin K is found in most over-the-counter (OTC) multivitamins, the strength is insufficient. Most OTC formulations are ≤ 100 μg, whereas the prescription strength is 5 mg, but patients being treated for rodenticide poisoning require much larger doses.

Commercial insurance carriers and Medicare Part D usually do not cover vitamins and minerals unless it is for a medically accepted indication or is an indication supported by citation in either the American Hospital Formulary System, United States Pharmacopeia drug information book, or an electronic information resource that is supported by evidence such as Micromedex.21 For a patient without insurance coverage being treated with high-dose vitamin K therapy for rodenticide poisoning outside of a federal health care system, the cost could be as high as $500 to $1,000 per day, depending on the dose of vitamin K needed to maintain an acceptable INR.

Conclusion

In addition to bleeding as a result of coagulopathy, this patient presented with new onset of AF with rapid ventricular response and a newly diagnosed cardiomyopathy. Although the patient had other cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and a remote history of cocaine use, it is likely that the use of the synthetic cannabinoids contributed to the development and/or worsening of this arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy. The patient remained in AF 6 weeks after hospital discharge with a controlled ventricular rate on metoprolol and digoxin. An interval echocardiogram 6 weeks after hospital discharge showed a recovered ejection fraction. In cases of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy, the ejection fraction often recovers with control of the tachycardia. The patient was weaned off vitamin K about 6 months after his initial presentation and started on a DOAC for anticoagulation. He subsequently underwent a transesophageal echocardiogram followed by an attempt at DC cardioversion; however, he did not remain in sinus rhythm and is being continued on anticoagulation and rate control for his AF.

Although unclear how synthetic cannabinoids became adulterated with a potent vitamin K antagonist, health care practitioners should consider this if a patient presents with unexplained coagulopathy and widespread bleeding. Fixed-dose PCC should be considered as an alternative to weight-based dosing in these cases. Physicians and pharmacy personnel should anticipate a need for long-term high doses of vitamin K in order to begin work early to obtain sufficient supplies to treat presenting patients.

1. Illinois Department of Public Health. Synthetic cannabinoids. http://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/prevention-wellness/medical-cannabis/synthetic-cannabinoids. Updated May 30, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

2. Tournebize J, Gibaja V, Kahn JP. Acute effects of synthetic cannabinoids: update 2015. Subst Abus. 2017;38(3):344-366.

3. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global SMART update. https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Global_SMART_Update_13_web.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed April 8, 2019.

4. Adams AJ, Banister SD, Irizarry L, Trecki J, Schwartz M, Gerona R, “Zombie” outbreak caused by the synthetic cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):235-242.

5. Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on management of bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulants: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):3042-3067.

6. Cushman M, Lim W, Zakai NA. 2011 Clinical Practice guide on anticoagulant dosing and management of anticoagulant-associated bleeding complications in adults. http://www.hematology.org/Clinicians/Guidelines-Quality/Quick-Ref/525.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2019.

7. Klein L, Peters J, Miner J, Gorlin J. Evaluation of fixed dose 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate for emergent warfarin reversal. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1213-1218.

8. Bachmann KA, Sullivan TJ. Dispositional and pharmacodynamic characteristics of brodifacoum in warfarin-sensitive rats. Pharmacology. 1983;27(5):281-288.

9. Lipton RA, Klass EM. Human ingestion of ‘superwarfarin’ rodenticide resulting in a prolonged anticoagulant effect. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3004-3005.

10. Chong LL, Chau WK, Ho CH. A case of ‘superwarfarin’ poisoning. Scand J Haematol. 1986;36(3):314-331.

11. Jones EC, Growe GH, Naiman SC. Prolonged anticoagulation in rat poisoning. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3005-3007.

12. Babcock J, Hartman K, Pedersen A, Murphy M, Alving B. Rodenticide-induced coagulopathy in a young child. A case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;15(1):126-130.

13. Hollinger BR, Pastoor TP. Case management and plasma half-life in a case of brodifacoum poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1925-1928.

14. Bruno GR, Howland MA, McMeeking A, Hoffman RS. Long-acting anticoagulant overdose: brodifacoum kinetics and optimal vitamin K dosing. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(3):262-267.

15. Vandenbrouke V, Bousquet-Meloua A, De Backer P, Croubels S. Pharmacokinetics of eight anticoagulant rodenticides in mice after single oral administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(5):437-445.

16. Barlow AM, Gay AL, Park BK. Difenacoum (Neosorexa) poisoning. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285(6341):541.

17. Katona B, Wason S. Superwarfarin poisoning. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):627-631.

18. Butcher GP, Shearer MJ, MacNicoll AD, Kelly MJ, Ind PW. Difenacoum poisoning as a cause of haematuria. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1992;11(6):553-554.

19. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Current drug shortages. Vitamin K (phytonadione) injection. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/Drug-Shortage-Detail.aspx?id=100. Updated July 5, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

20. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e152S-e184S.

21. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Part D Excluded Drugs. https://www.medicareadvocacy.org/old-site/News/Archives/PartD_ExcludedDrugsByState.htm. Accessed on August 23, 2018.

1. Illinois Department of Public Health. Synthetic cannabinoids. http://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/prevention-wellness/medical-cannabis/synthetic-cannabinoids. Updated May 30, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

2. Tournebize J, Gibaja V, Kahn JP. Acute effects of synthetic cannabinoids: update 2015. Subst Abus. 2017;38(3):344-366.

3. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global SMART update. https://www.unodc.org/documents/scientific/Global_SMART_Update_13_web.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed April 8, 2019.

4. Adams AJ, Banister SD, Irizarry L, Trecki J, Schwartz M, Gerona R, “Zombie” outbreak caused by the synthetic cannabinoid AMB-FUBINACA in New York. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(3):235-242.

5. Tomaselli GF, Mahaffey KW, Cuker A, et al. 2017 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on management of bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulants: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Expert Consensus Decision Pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(24):3042-3067.

6. Cushman M, Lim W, Zakai NA. 2011 Clinical Practice guide on anticoagulant dosing and management of anticoagulant-associated bleeding complications in adults. http://www.hematology.org/Clinicians/Guidelines-Quality/Quick-Ref/525.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed April 8, 2019.

7. Klein L, Peters J, Miner J, Gorlin J. Evaluation of fixed dose 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate for emergent warfarin reversal. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1213-1218.

8. Bachmann KA, Sullivan TJ. Dispositional and pharmacodynamic characteristics of brodifacoum in warfarin-sensitive rats. Pharmacology. 1983;27(5):281-288.

9. Lipton RA, Klass EM. Human ingestion of ‘superwarfarin’ rodenticide resulting in a prolonged anticoagulant effect. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3004-3005.

10. Chong LL, Chau WK, Ho CH. A case of ‘superwarfarin’ poisoning. Scand J Haematol. 1986;36(3):314-331.

11. Jones EC, Growe GH, Naiman SC. Prolonged anticoagulation in rat poisoning. JAMA. 1984;252(21):3005-3007.

12. Babcock J, Hartman K, Pedersen A, Murphy M, Alving B. Rodenticide-induced coagulopathy in a young child. A case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;15(1):126-130.

13. Hollinger BR, Pastoor TP. Case management and plasma half-life in a case of brodifacoum poisoning. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1925-1928.

14. Bruno GR, Howland MA, McMeeking A, Hoffman RS. Long-acting anticoagulant overdose: brodifacoum kinetics and optimal vitamin K dosing. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(3):262-267.

15. Vandenbrouke V, Bousquet-Meloua A, De Backer P, Croubels S. Pharmacokinetics of eight anticoagulant rodenticides in mice after single oral administration. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31(5):437-445.

16. Barlow AM, Gay AL, Park BK. Difenacoum (Neosorexa) poisoning. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285(6341):541.

17. Katona B, Wason S. Superwarfarin poisoning. J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):627-631.

18. Butcher GP, Shearer MJ, MacNicoll AD, Kelly MJ, Ind PW. Difenacoum poisoning as a cause of haematuria. Hum Exp Toxicol. 1992;11(6):553-554.

19. American Society of Health System Pharmacists. Current drug shortages. Vitamin K (phytonadione) injection. https://www.ashp.org/drug-shortages/current-shortages/Drug-Shortage-Detail.aspx?id=100. Updated July 5, 2018. Accessed April 8, 2019.

20. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e152S-e184S.

21. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Part D Excluded Drugs. https://www.medicareadvocacy.org/old-site/News/Archives/PartD_ExcludedDrugsByState.htm. Accessed on August 23, 2018.

Basal Cell Carcinoma Masquerading as a Dermoid Cyst and Bursitis of the Knee

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

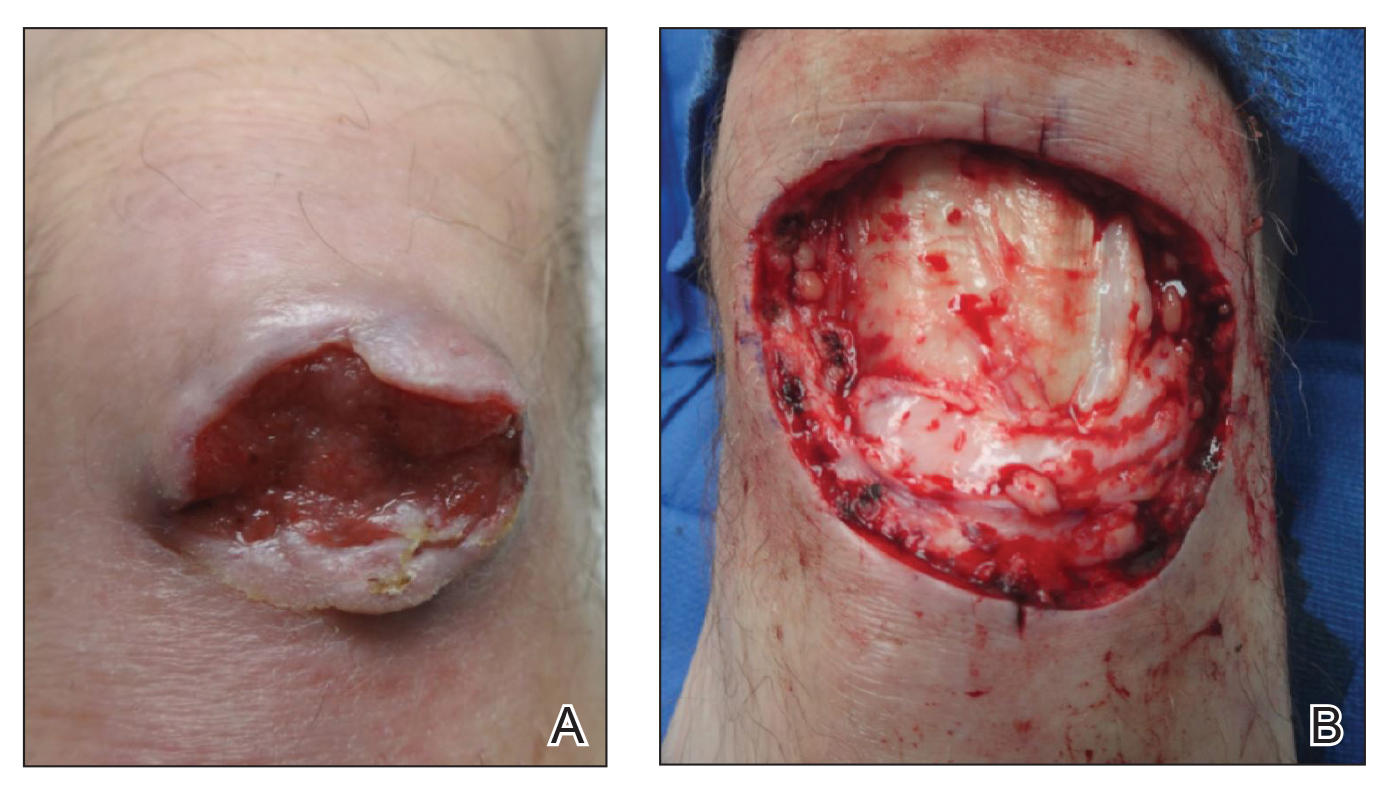

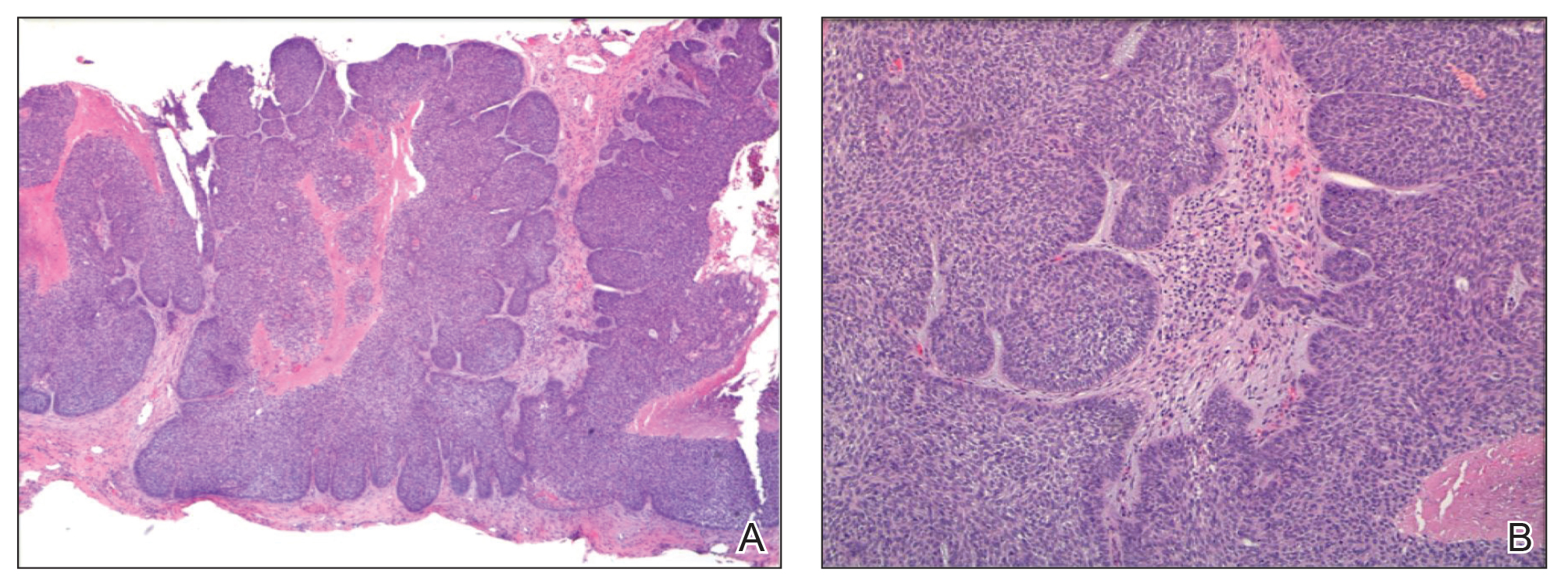

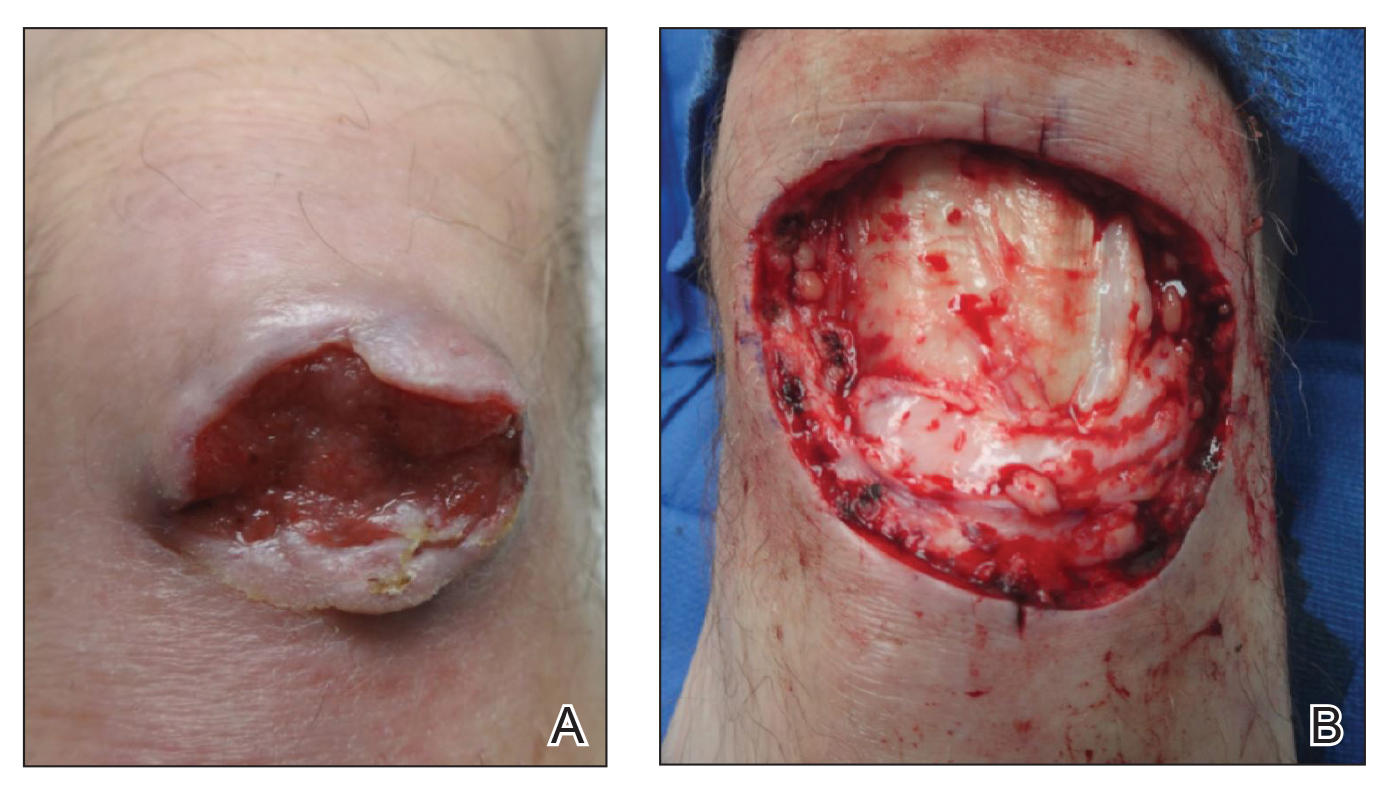

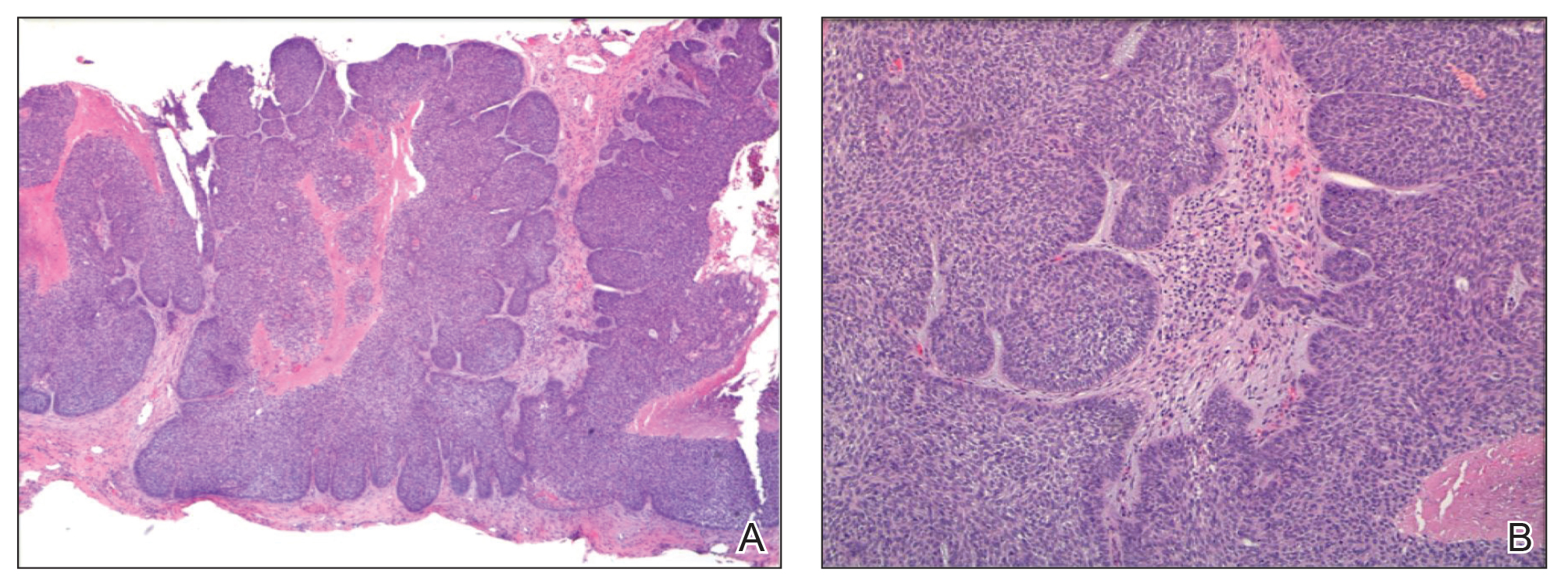

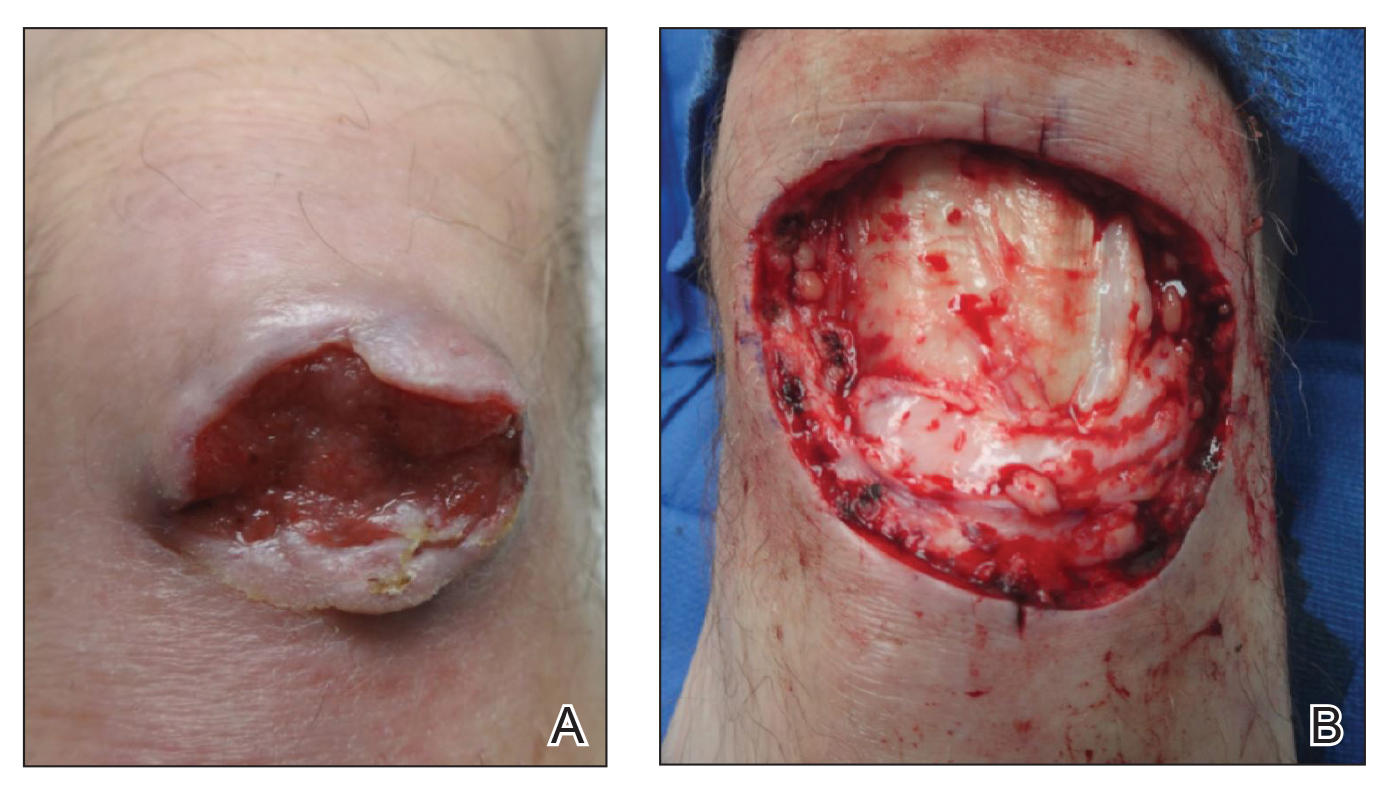

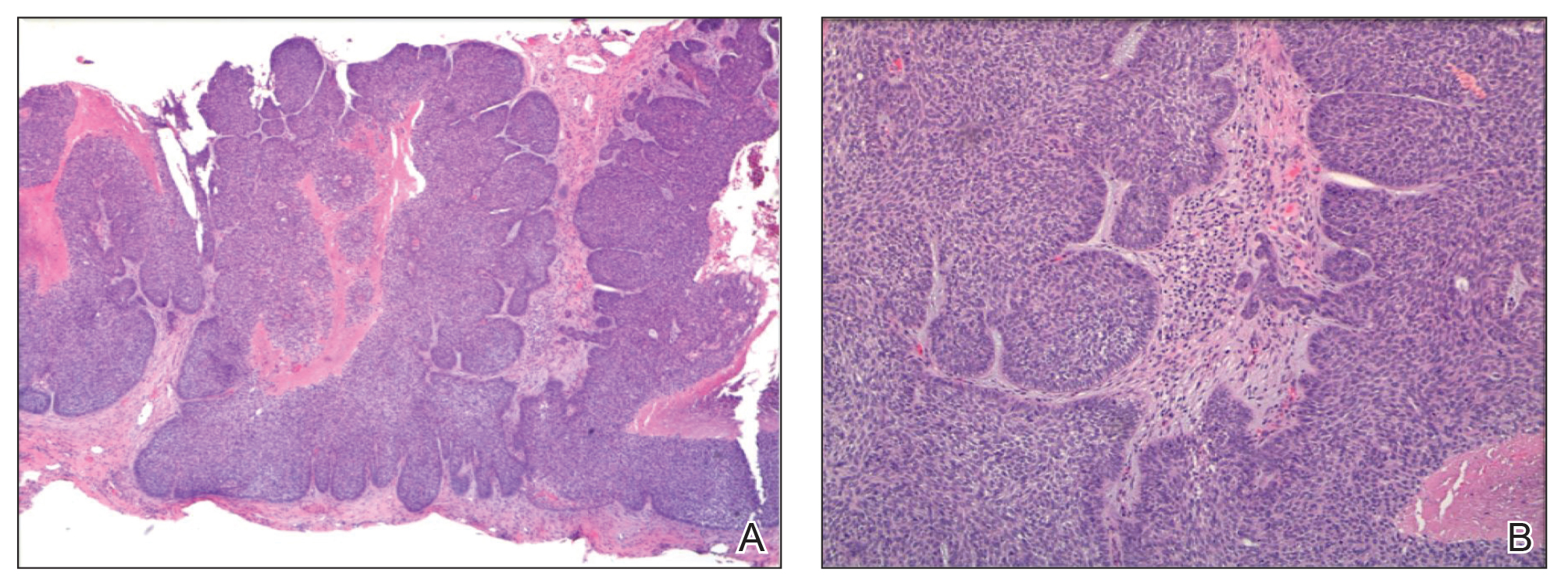

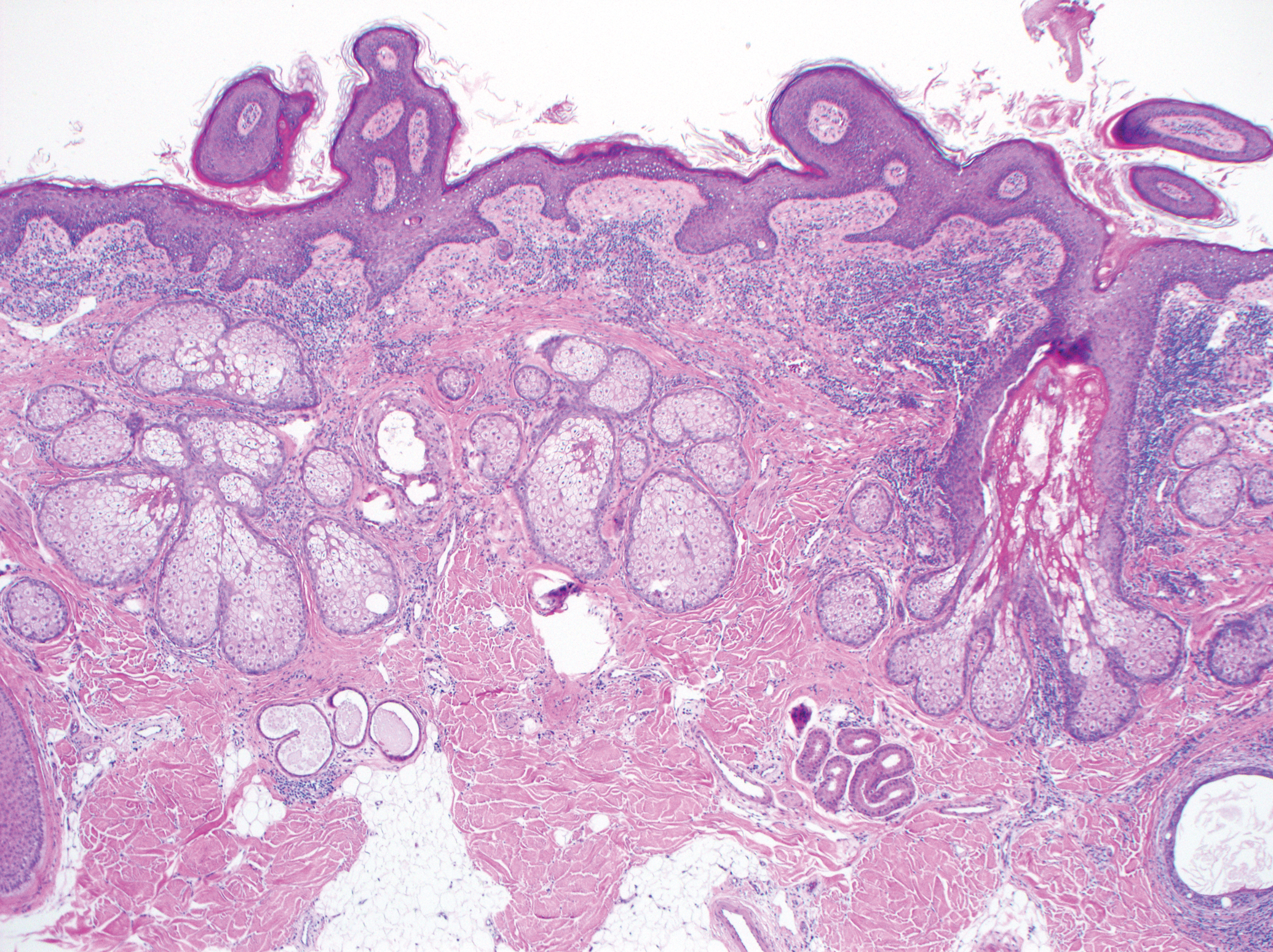

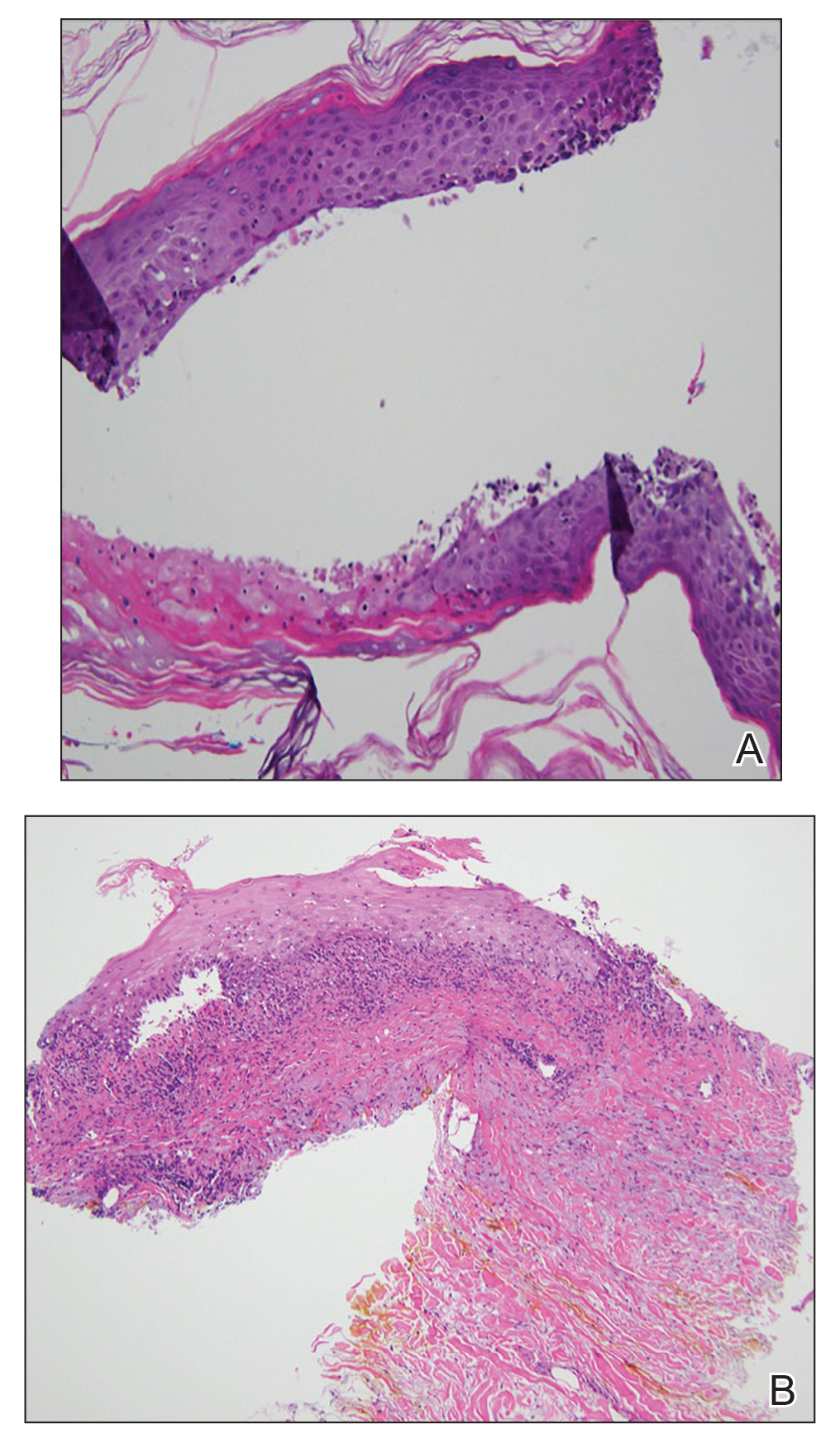

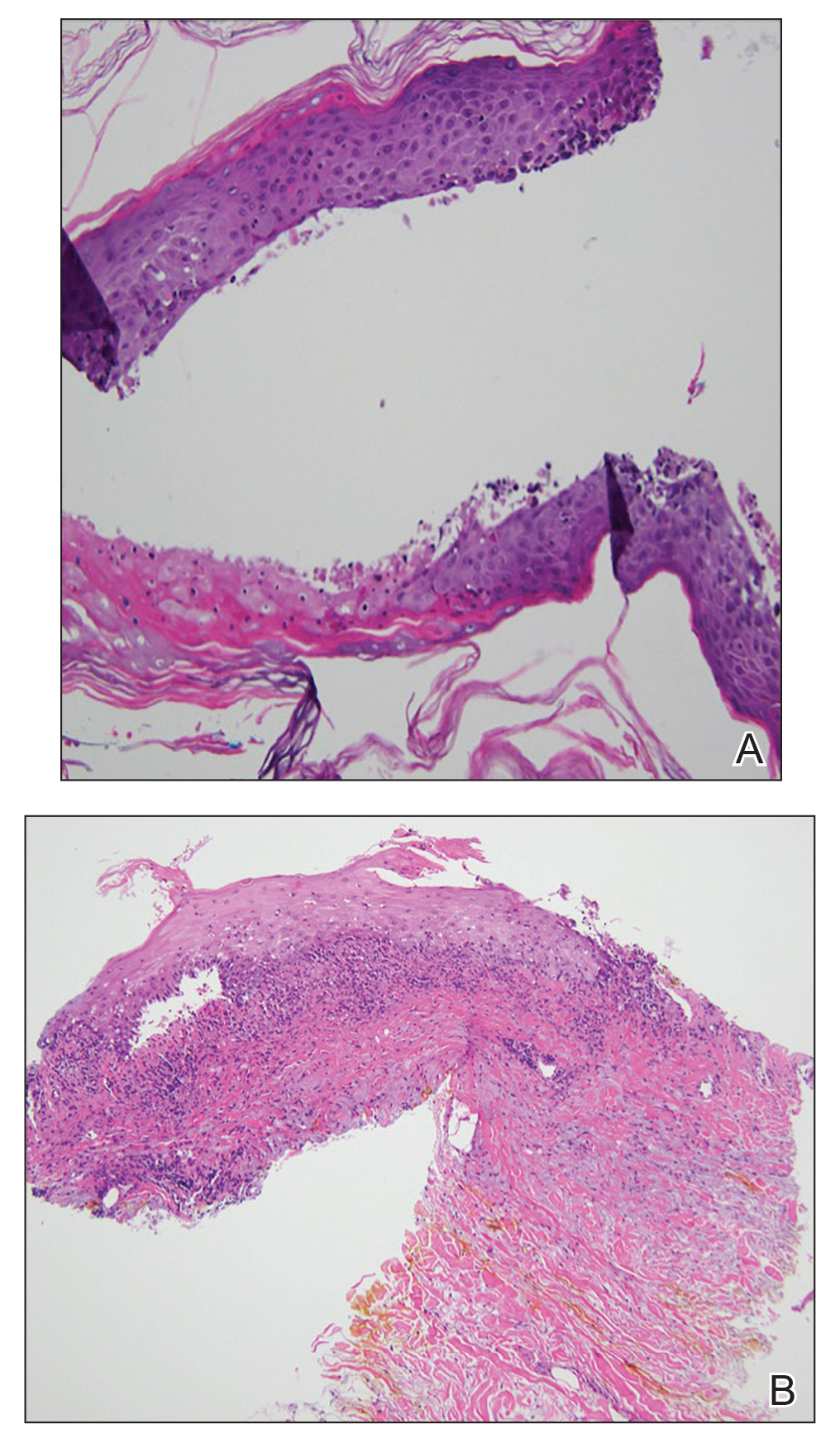

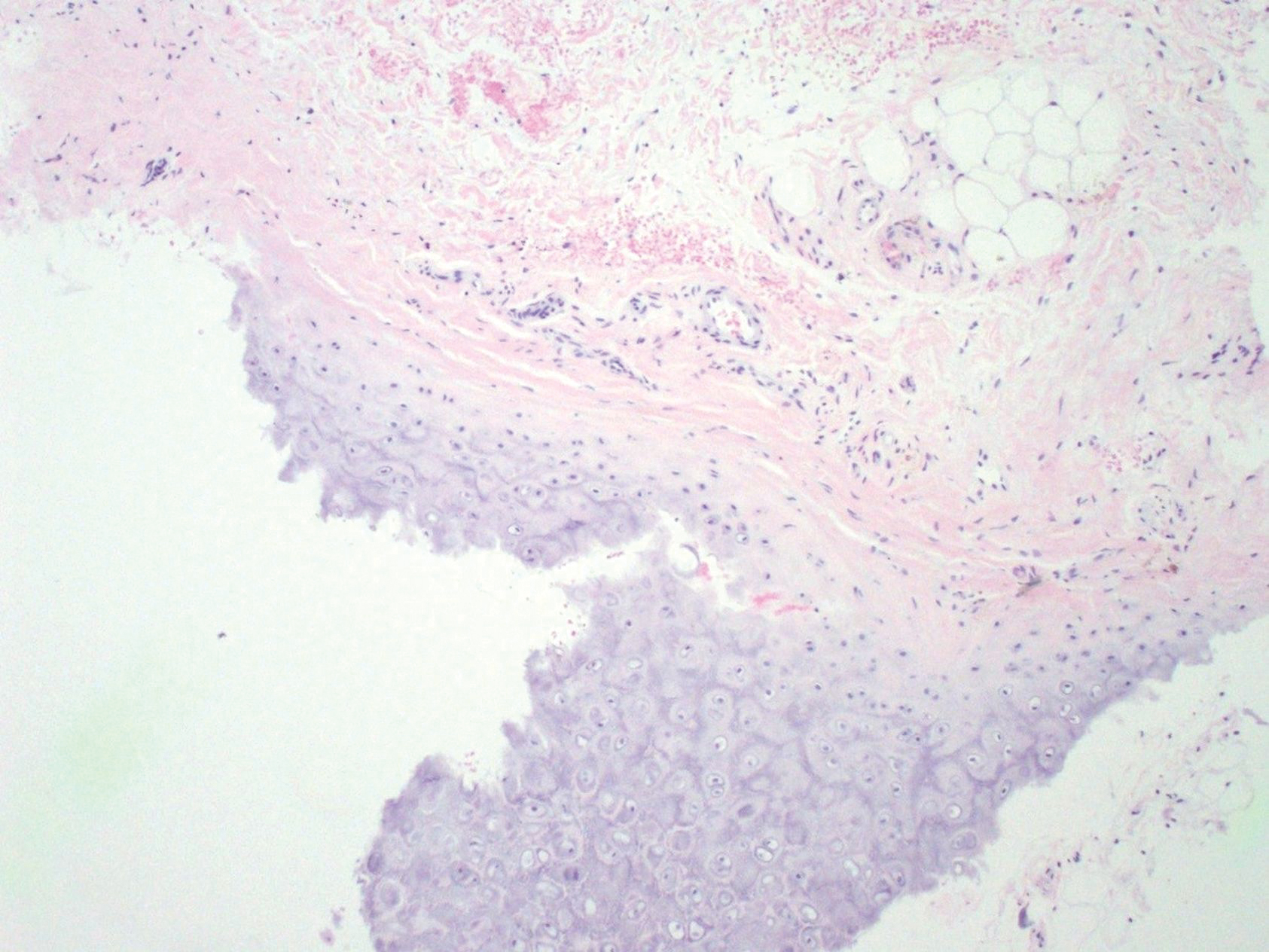

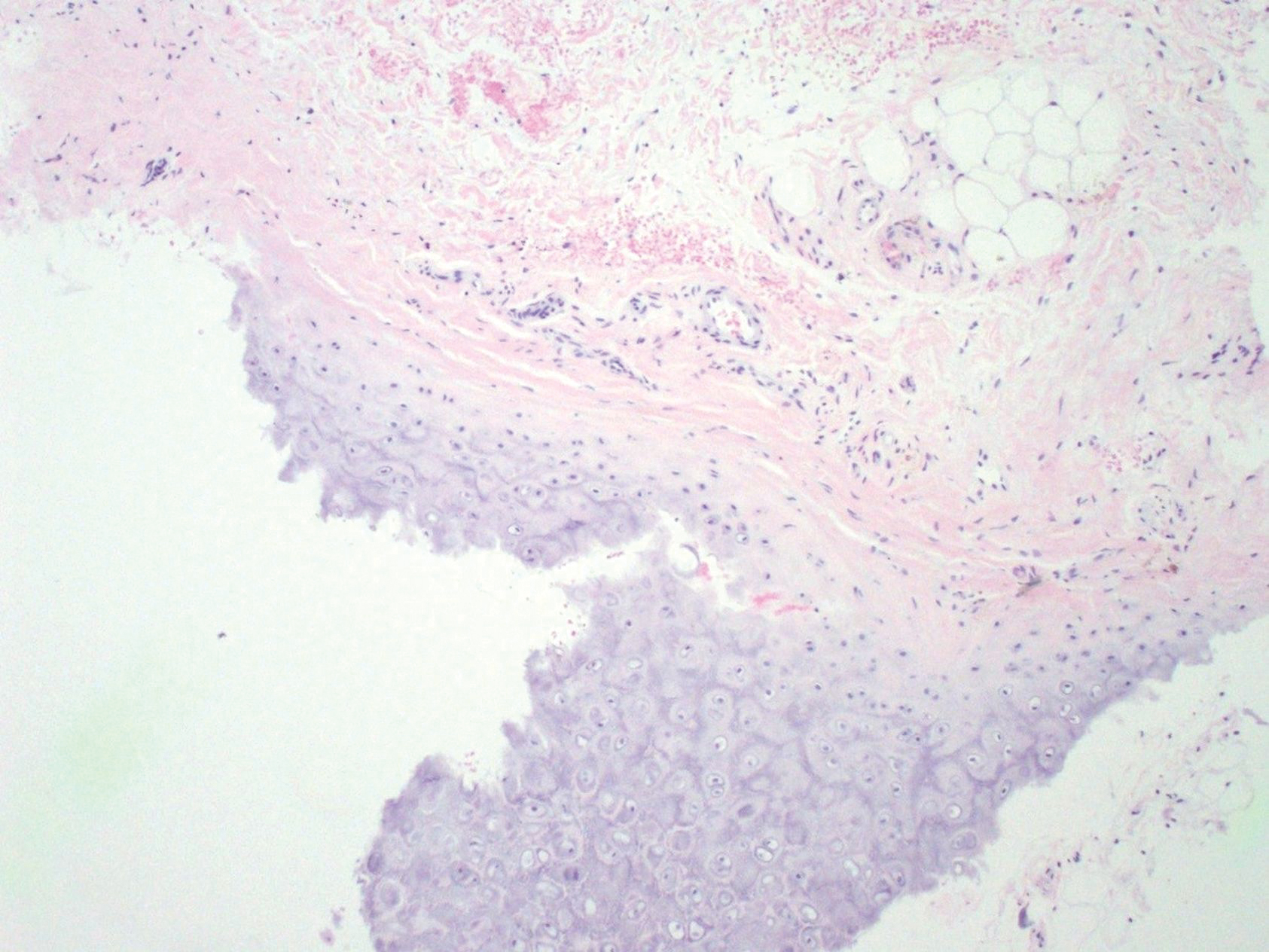

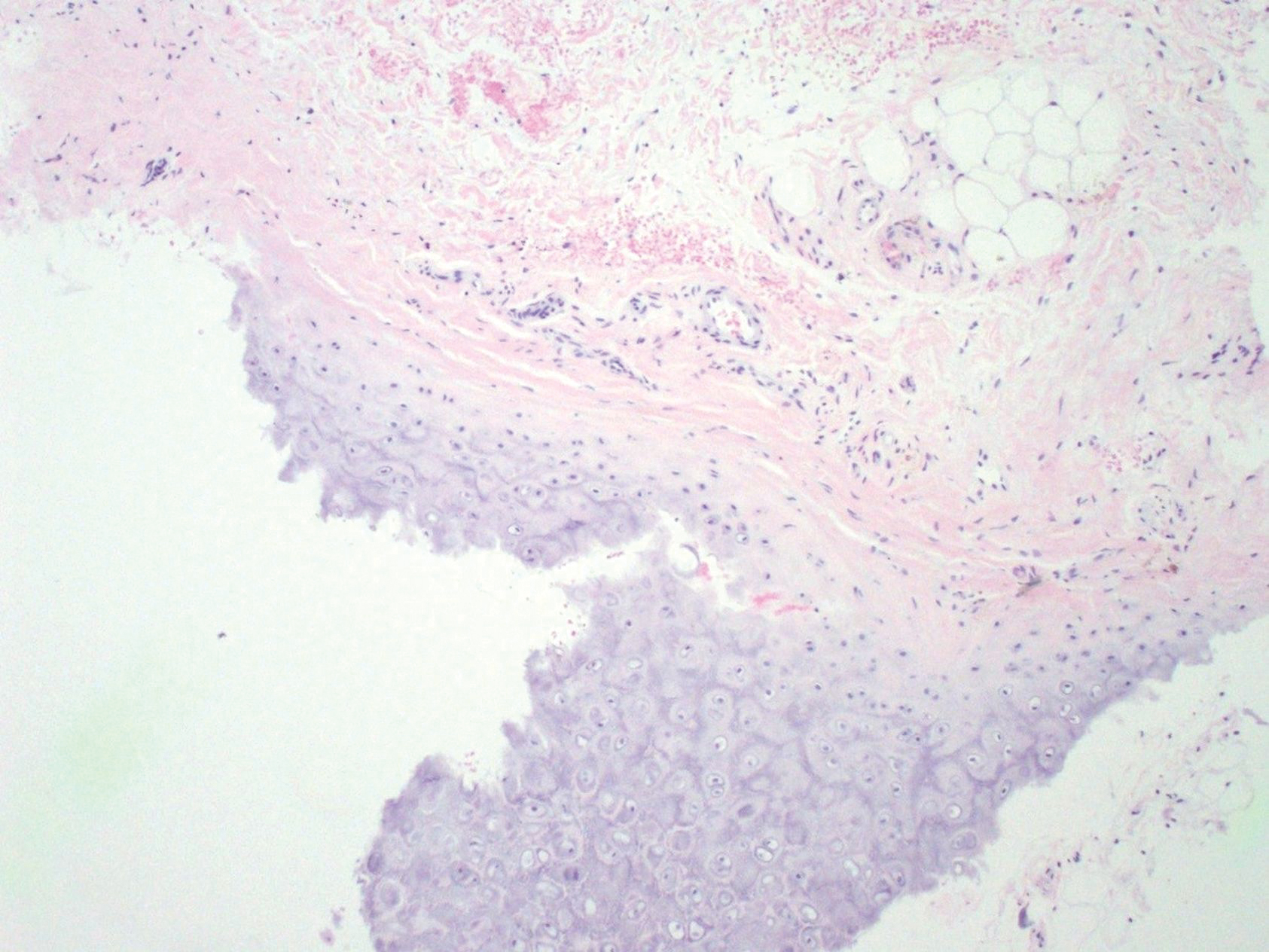

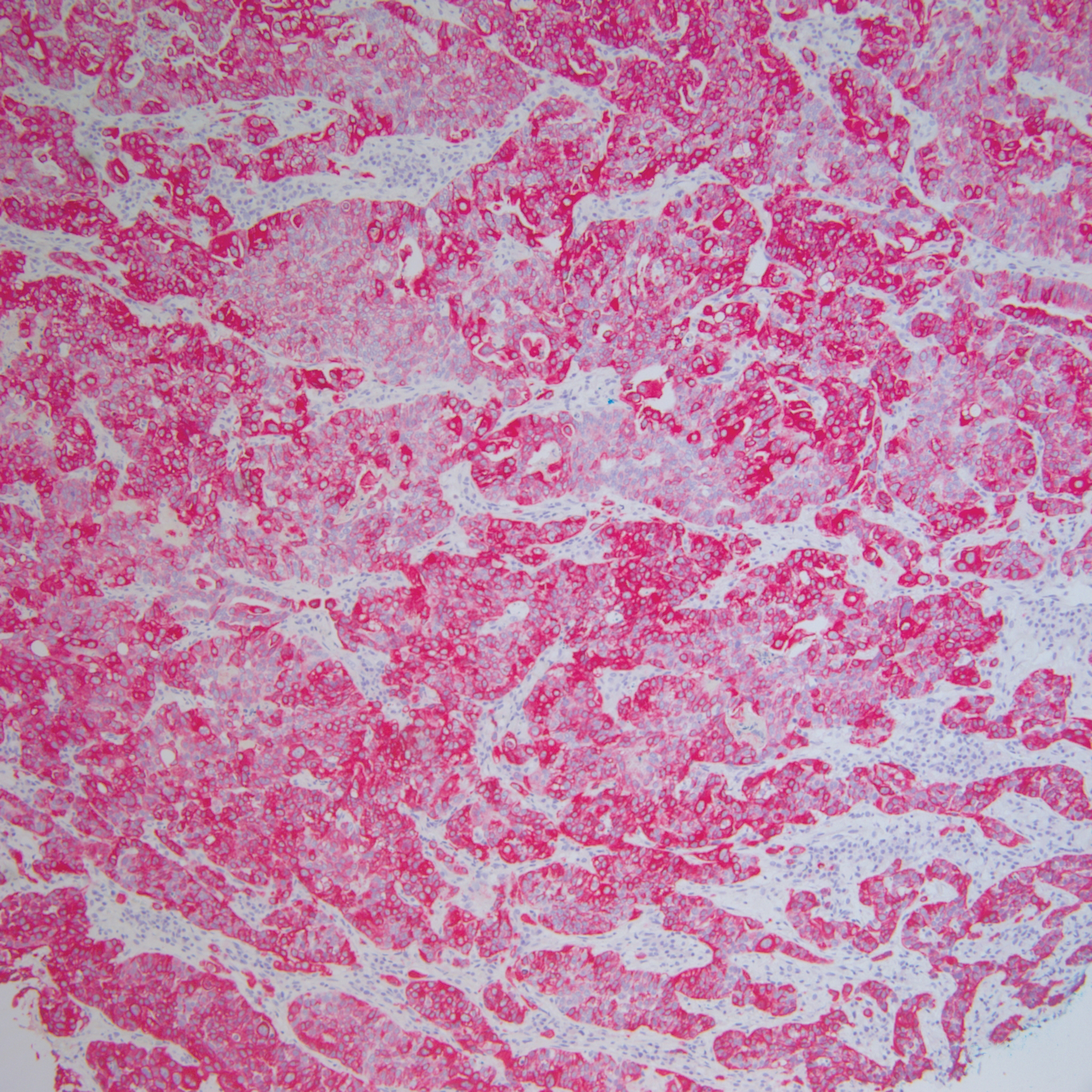

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most frequently diagnosed skin cancer in the United States. It develops most often on sun-exposed skin, including the face and neck. Although BCCs are slow-growing tumors that rarely metastasize, they can cause notable local destruction with disfigurement if neglected or inadequately treated. Basal cell carcinoma arising on the legs is relatively uncommon.1,2 We present an interesting case of delayed diagnosis of BCC on the left knee due to earlier misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with no history of skin cancer presented with a painful growing tumor on the left knee of approximately 2 years’ duration. The patient’s primary care physician as well as a general surgeon initially diagnosed it as a dermoid cyst and bursitis. The nodule failed to respond to conservative therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and continued to grow until it began to ulcerate. Concerned about the possibility of septic arthritis, the patient’s primary care physician referred him to the emergency department. He was subsequently sent to the dermatology clinic.

On examination by dermatology, a 6.3×4.4-cm, tender, mobile, ulcerated nodule was noted on the left knee (Figure 1A). No popliteal or inguinal lymph nodes were palpable. Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or atypical infection (eg, Leishmania, deep fungal, mycobacterial) was suspected clinically. The patient underwent a diagnostic skin biopsy; hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lobular proliferation of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and central tumoral necrosis, consistent with primary BCC (Figure 2).

Given the size of the tumor, the patient was referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and eventual reconstruction by a plastic surgeon. The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs surgery, with a final wound size of 7.7×5.4 cm (Figure 1B). Plastic surgery later performed a gastrocnemius muscle flap with a split-thickness skin graft (175 cm2) to repair the wound.

Comment

Exposure to UV radiation is the primary causative agent of most BCCs, accounting for the preferential distribution of these tumors on sun-exposed areas of the body. Approximately 80% of BCCs are located on the head and neck, 10% occur on the trunk, and only 8% are found on the lower extremities.1

Giant BCC, the finding in this case, is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer as a tumor larger than 5 cm in diameter. Fewer than 1% of all BCCs achieve this size; they appear more commonly on the back where they can go unnoticed.2 Neglect and inadequate treatment of the primary tumor are the most important contributing factors to the size of giant BCCs. Giant BCCs also have more aggressive biologic behavior, with an increased risk for local invasion and metastasis.3 In this case, the lesion was larger than 5 cm in diameter and occurred on the lower extremity rather than on the trunk.

This case is unusual because delayed diagnosis of BCC was the result of misdiagnoses of a dermoid cyst and bursitis, with a diagnostic skin biopsy demonstrating BCC almost 2 years later. It should be emphasized that early diagnosis and treatment could prevent tumor expansion. Physicians should have a high degree of suspicion for BCC, especially when a dermoid cyst and knee bursitis fail to respond to conservative management.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

- Pearson G, King LE, Boyd AS. Basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:852-854.

- Arnaiz J, Gallardo E, Piedra T, et al. Giant basal cell carcinoma on the lower leg: MRI findings. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:1167-1168.

- Randle HW. Giant basal cell carcinoma [letter]. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:222-223.

Practice Points

- This case highlights an unusual presentation of basal cell carcinoma masquerading as bursitis.

- Clinicians should be aware of confirmation bias, especially when multiple physicians and specialists are involved in a case.

- When the initial clinical impression is not corroborated by objective data or the condition is not responding to conventional therapy, it is important for clinicians to revisit the possibility of an inaccurate diagnosis.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma With Perineural Involvement in Nevus Sebaceus

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.

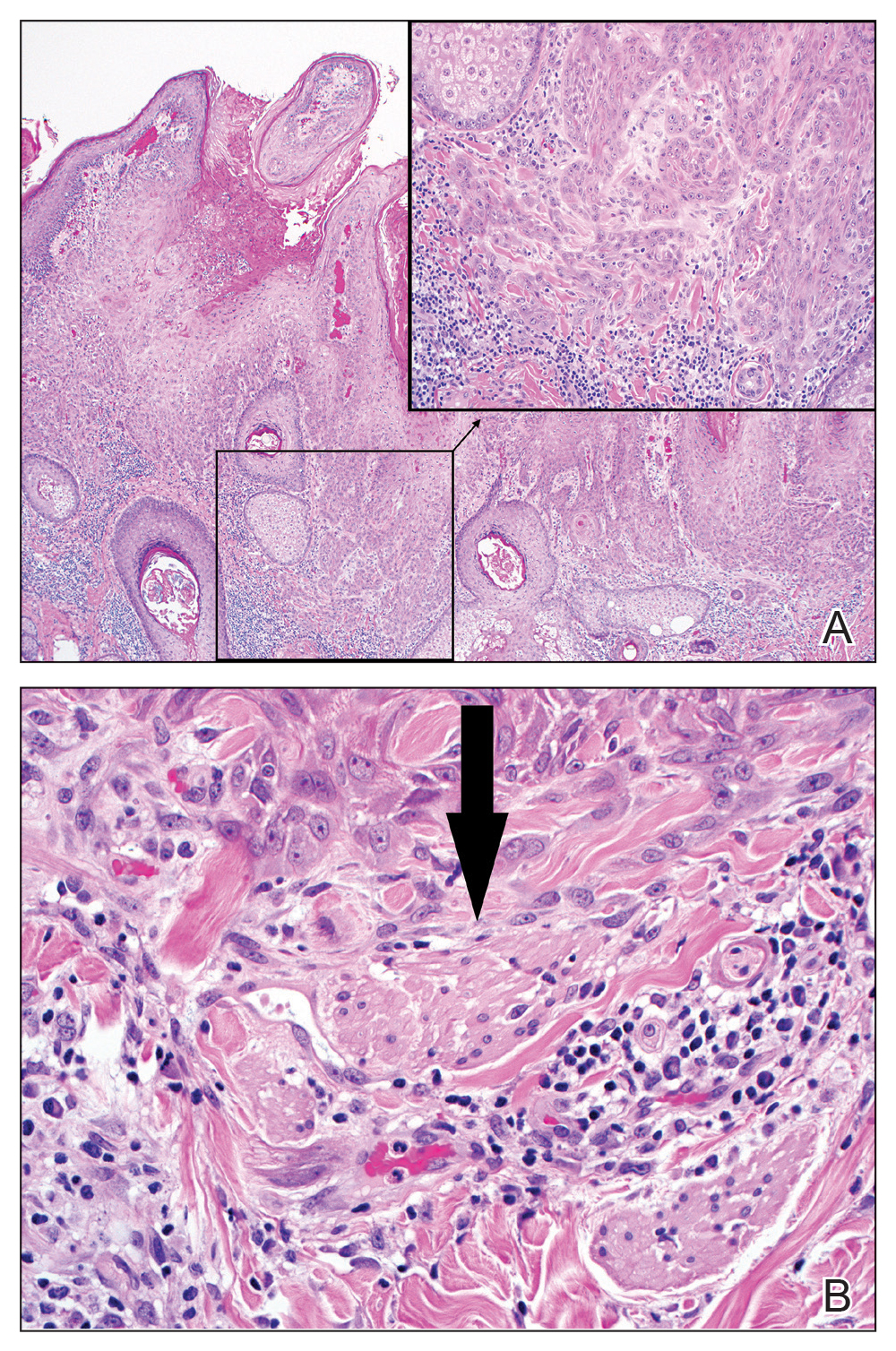

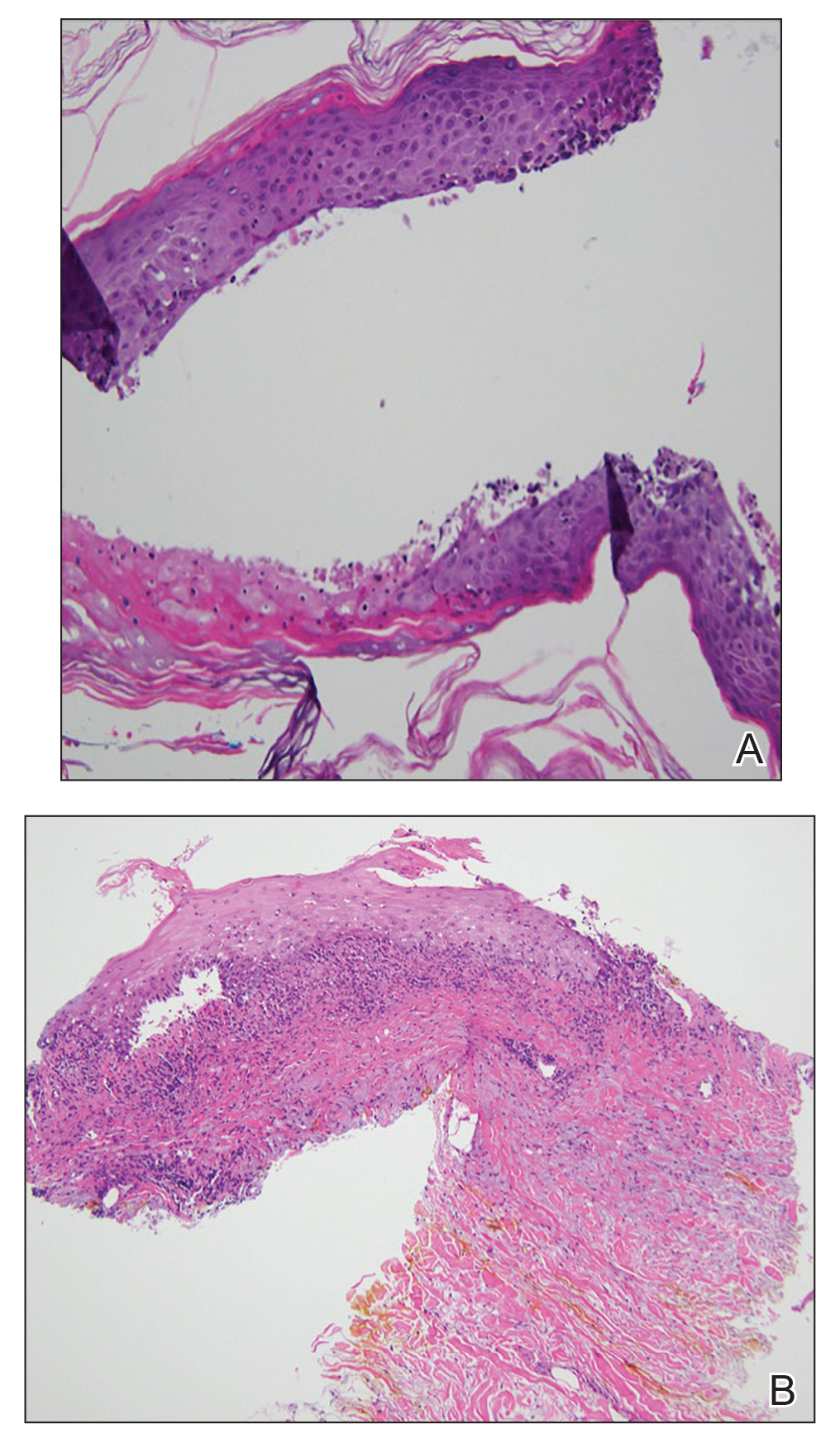

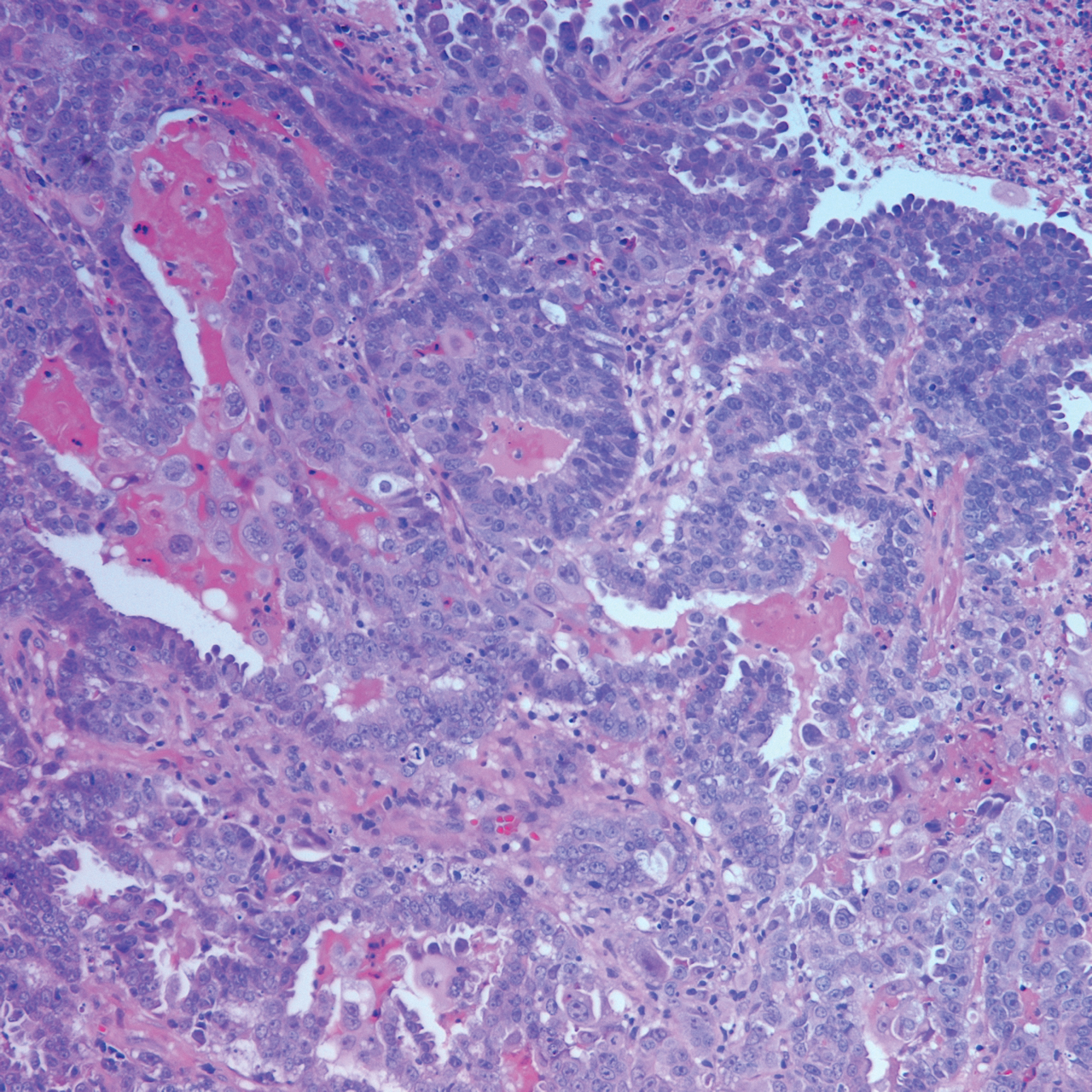

Excision was conducted under local anesthesia without complication. An elliptical section of skin measuring 0.8×2.5 cm was excised to a depth of 3 mm. The resulting wound was closed using a complex linear repair. The section was placed in formalin specimen transport medium and sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). Microscopic examination of the specimen revealed features typical for NS, including mild verrucous epidermal hyperplasia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia, presence of apocrine glands, and hamartomatous follicular proliferations (Figure 2). An even more papillomatous epidermal proliferation that was comprised of atypical squamous cells was present within the lesion. Similar atypical squamous cells infiltrated the superficial dermis in nests, cords, and single cells (Figure 3A). One focus showed perineural invasion with a small superficial nerve fiber surrounded by SCC (Figure 3B). The tumor was completely excised, with negative surgical margins extending approximately 2 mm. Adjuvant radiation therapy and further specialized Mohs micrographic excision were not performed because of the clear histologic appearance of the carcinoma and strong evidence of complete excision.

At 2-week follow-up, the surgical scar on the anterior central forehead was well healed without evidence of SCC recurrence. On physical examination there was neither lymphadenopathy nor signs of neurologic deficit, except for superficial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the immediate area surrounding the healed site. Following discussion with the patient and her parents, it was decided that the patient would obtain baseline laboratory tests, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography, and she would undergo serial follow-up examinations every 3 months for the next 2 years. Annual follow-up was recommended after 2 years, with the caveat to return sooner if recurrence or symptoms were to arise.

Comment

Historically, there has been variability in the histopathologic interpretation of SCC in NS in the literature. Retrospective analysis of the histologic evidence of SCC in the 2 earliest possible cases of pediatric SCC in NS have been questioned due to the lack of clinical data presented and the possibility that the diagnosis of SCC was inaccurate.6 Our case was histopathologically interpreted as superficially invasive, well-differentiated SCC arising within an NS; therefore, we classified this case as SCC and took every precaution to ensure the lesion was completely excised, given the potentially invasive nature of SCC.

Our case is unique because it represents SCC in NS with histologic evidence of perineural involvement. Perineural invasion is a major route of tumor spread in SCC and may result in increased occurrence of regional lymph node spread and distant metastases, with path of least resistance or neural cell adhesion as possible spreading methods.7-9 However, there is a notable amount of prognostic variability based on tumor type, the nerve involved, and degree of involvement.9 It is common for cutaneous SCC to occur with invasion of small intradermal nerves, but a poor outcome is less likely in asymptomatic patients who have perineural involvement that was incidentally discovered on histologic examination.10

In our patient, the entire tumor was completely removed with local excision. Recurrence of the SCC or future symptoms of deep neural invasion were not anticipated given the postoperative evidence of clear margins in the excised skin and subdermal structures as well as the lack of preoperative and postoperative symptoms. Close clinical follow-up was warranted to monitor for early signs of recurrence or neural involvement. We have confidence that the planned follow-up regimen in our patient will reveal any early signs of new occurrence or recurrence.

In the case of recurrence, Mohs micrographic surgery would likely be indicated. We elected not to treat with adjuvant radiotherapy because its benefit in cutaneous SCC with perineural invasion is debatable based on the lack of randomized controlled clinical evidence.10,11 The patient obtained postoperative baseline complete blood cell count with differential, posterior/anterior and lateral chest radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasonography. Each returned negative findings of hematologic or distant organ metastases, with subsequent follow-up visits also negative for any new concerning findings.

- Cribier B, Scrivener Y, Grosshans E. Tumors arising in nevus sebaceus: a study of 596 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42(2, pt 1):263-268.

- Aguayo R, Pallares J, Cassanova JM, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in Jadassohn’s sebaceous nevus: case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1763-1768.

- Taher M, Feibleman C, Bennet R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a 9-year-old girl: treatment using Mohs micrographic surgery with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1203-1208.

- Hidvegi NC, Kangesu L, Wolfe KQ. Squamous cell carcinoma complicating naevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in a child. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56:50-52.

- Belhadjali H, Moussa A, Yahia S, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas within a nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn in an 11-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:236-237.

- Wilson-Jones EW, Heyl T. Naevus sebaceus: a report of 140 cases with special regard to the development of secondary malignant tumors. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:99-117.

- Ballantyne AJ, McCarten AB, Ibanez ML. The extension of cancer of the head and neck through perineural peripheral nerves. Am J Surg. 1963;106:651-667.

- Goepfert H, Dichtel WJ, Medina JE, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell skin carcinoma of the head and neck. Am J Surg. 1984;148:542-547.

- Feasel AM, Brown TJ, Bogle MA, et al. Perineural invasion of cutaneous malignancies. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:531-542.

- Cottel WI. Perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8:589-600.

- Mendenhall WM, Parsons JT, Mendenhall NP, et al. Carcinoma of the skin of the head and neck with perineural invasion. Head Neck. 1989;11:301-308.

First reported in 1895, nevus sebaceus (NS) is a con genital papillomatous hamartoma most commonly found on the scalp and face. 1 Lesions typically are yellow-orange plaques and often are hairless. Nevus sebaceus is most prominent in the few first months after birth and again at puberty during development of the sebaceous glands. Development of epithelial hyperplasia, cysts, verrucas, and benign or malignant tumors has been reported. 1 The most common benign tumors are syringocystadenoma papilliferum and trichoblastoma. Cases of malignancy are rare, and basal cell carcinoma is the predominant form (approximately 2% of cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adnexal carcinoma are reported at even lower rates. 1 Malignant transformation occurring during childhood is extremely uncommon. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms nevus sebaceous, malignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma and narrowing the results to children, there have been only 4 prior reports of SCC developing within an NS in a child. 2-5 We report a case of SCC arising in an NS in a 13-year-old adolescent girl with perineural invasion.

Case Report

A 13-year-old fair-skinned adolescent girl presented with a hairless 2×2.5-cm yellow plaque at the hairline on the anterior central scalp. The plaque had been present since birth and had progressively developed a superiorly located 3×5-mm erythematous verrucous nodule (Figure 1) with an approximate height of 6 mm over the last year. The nodule was subjected to regular trauma and bled with minimal insult. The patient appeared otherwise healthy, with no history of skin cancer or other chronic medical conditions. There was no evidence of lymphadenopathy on examination, and no other skin abnormalities were noted. There was no reported family history of skin cancer or chronic skin conditions suggestive of increased risk for cancer or other pathologic dermatoses. Differential diagnoses for the plaque and nodule complex included verruca, Spitz nevus, or secondary neoplasm within NS.