User login

Daily headaches • associated nausea • obesity • Dx?

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to our office complaining of headaches that started 6 weeks earlier. Initially the headache was throbbing, nonpositional, infrequent, and intermittent, lasting 15 to 45 minutes, often starting in the neck and migrating towards the right frontotemporal region. During the week prior to presentation, the headaches became daily and constant, with brief periods of relief after the patient took ibuprofen 400 mg 4 times a day as needed. The patient reported associated nausea, a sensation of pressure changes in the ears, and intermittent dimming of vision in the right eye (sometimes independent of headache). The patient denied photophobia and phonophobia. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive pill (OCP). She had no prior history of headaches.

Physical examination showed a blood pressure of 148/66 mm Hg, body mass index of 44.38, muscle tenderness in the neck and upper back, and no focal neurological findings. Funduscopic examination was unsuccessful. A working diagnosis of atypical migraine was made, but because of unilateral visual disturbance the patient was referred to Ophthalmology for further evaluation. The following day, ophthalmological consultation found bilateral papilledema and the patient was admitted to our hospitalist service via the Emergency Department. She subsequently was referred to inpatient Neurology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) with contrast of the brain showed possible stenosis at the junction of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses but no mass lesion nor venous sinus thrombosis. Lumbar puncture (LP) revealed an opening pressure of 650 mm H20 (reference range, 60–250 mm H2O).1 A diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) was made.

DISCUSSION

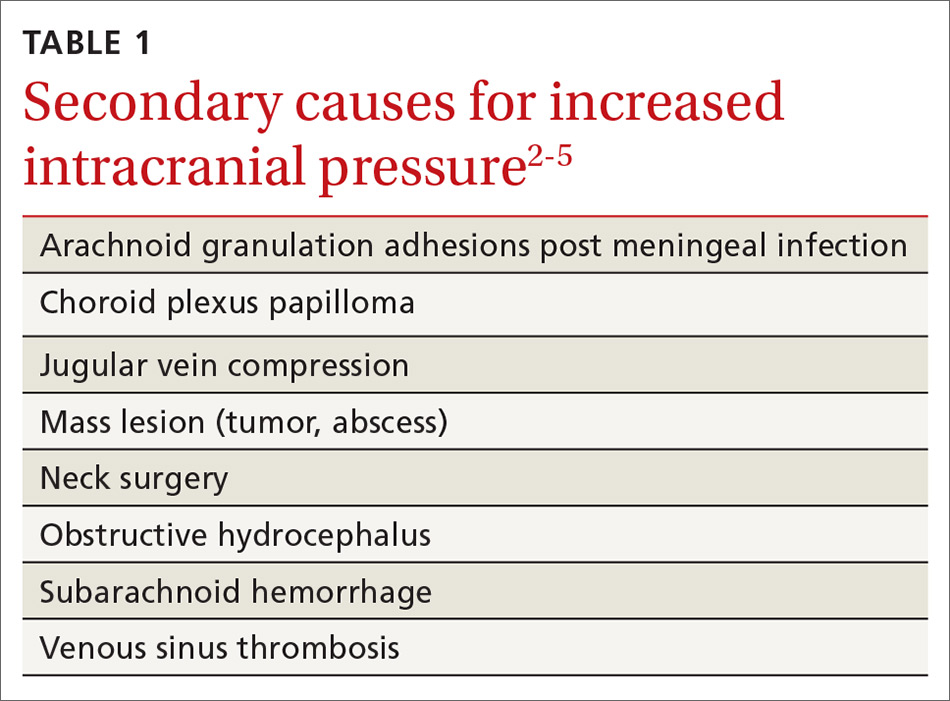

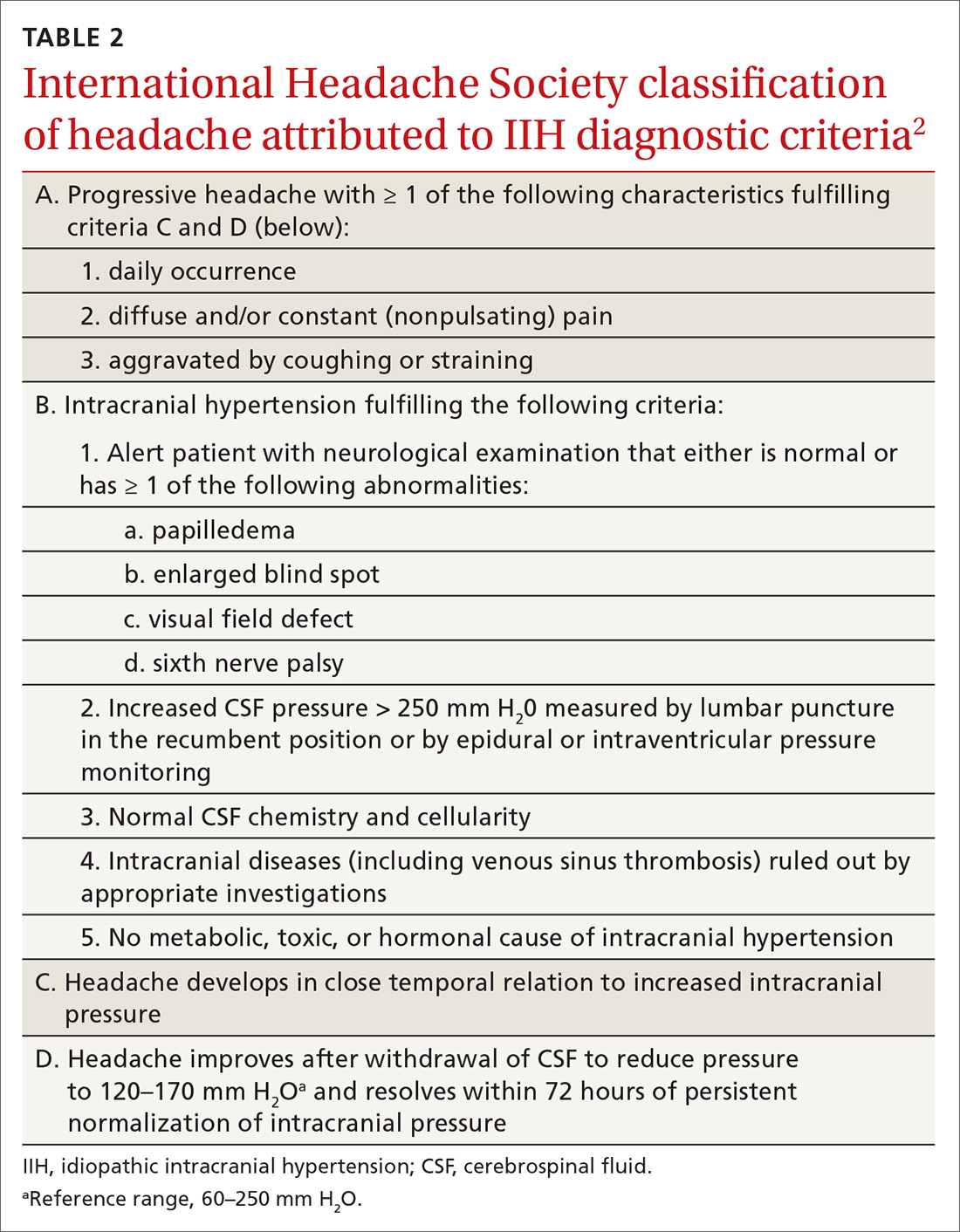

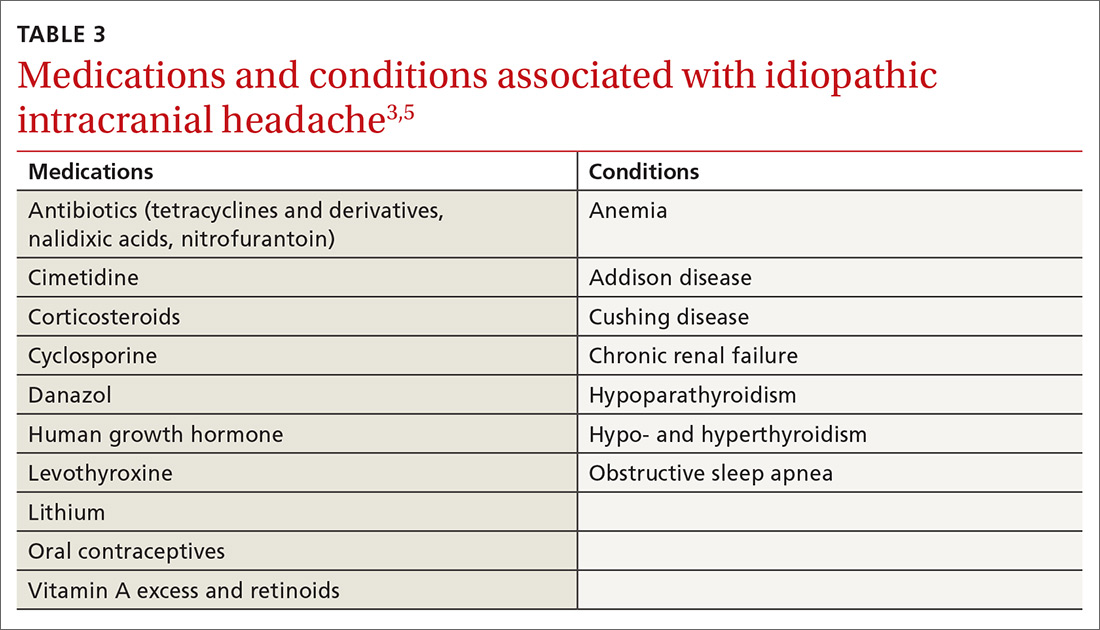

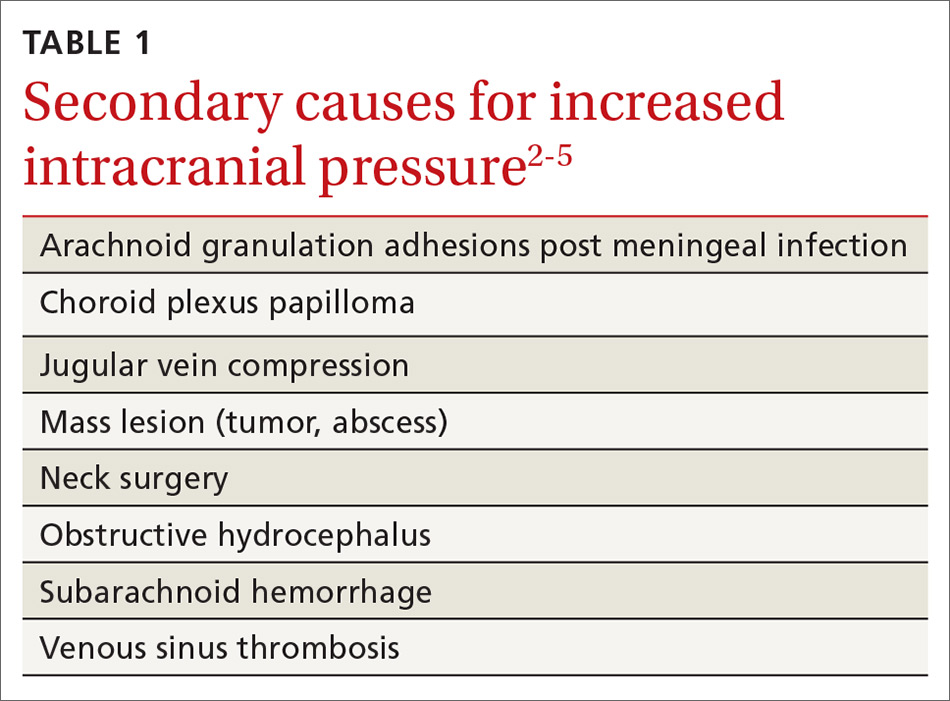

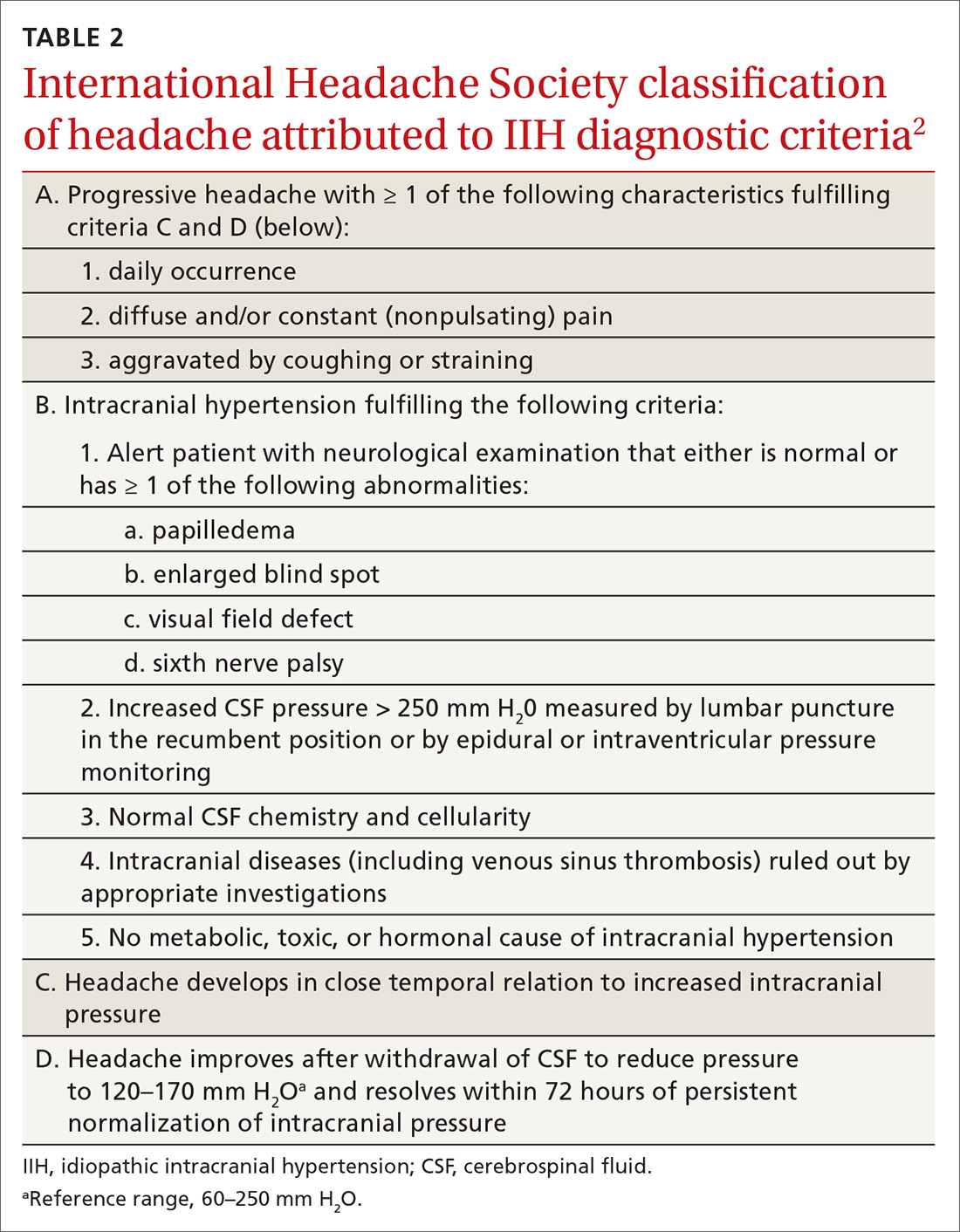

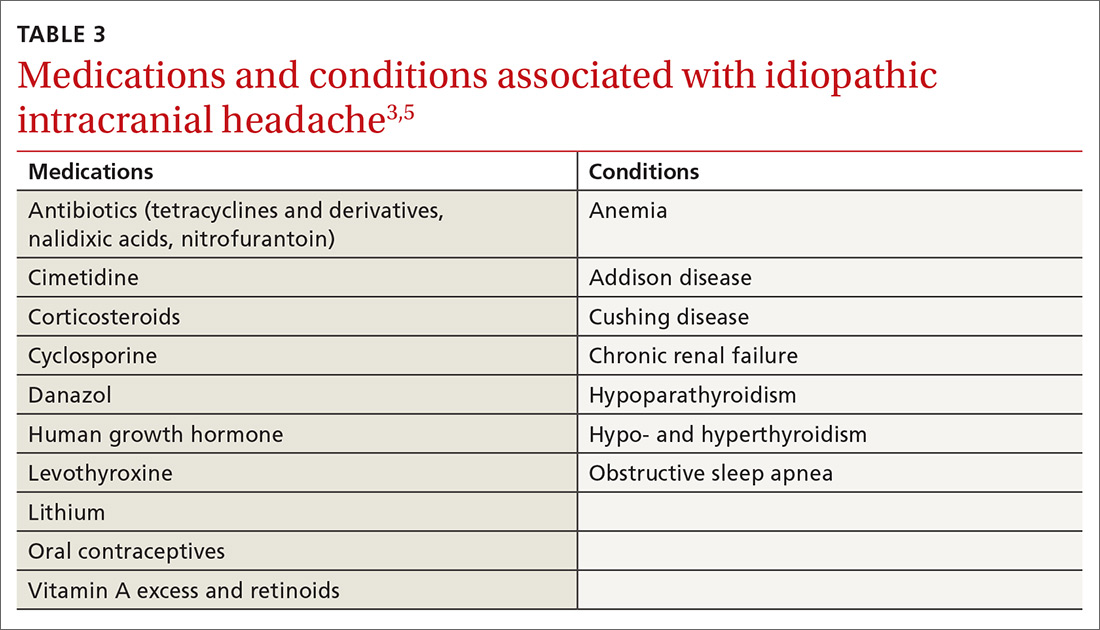

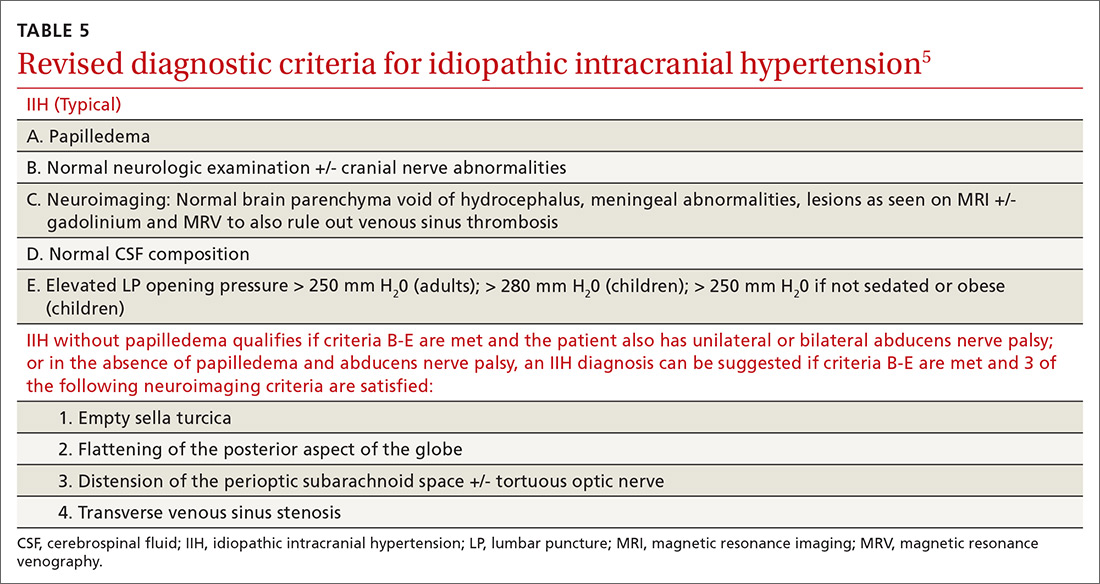

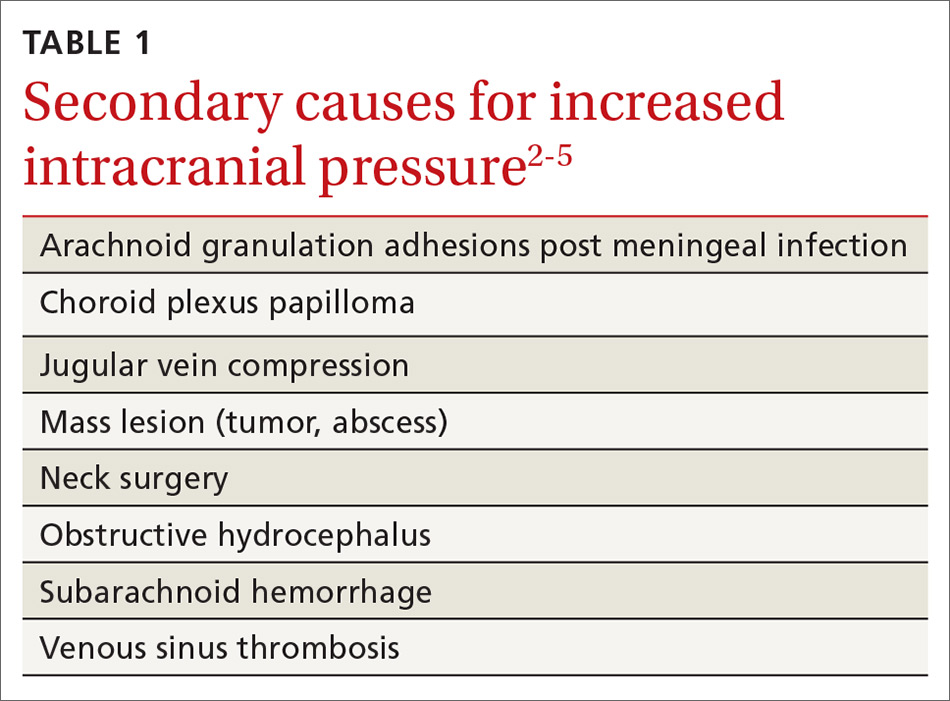

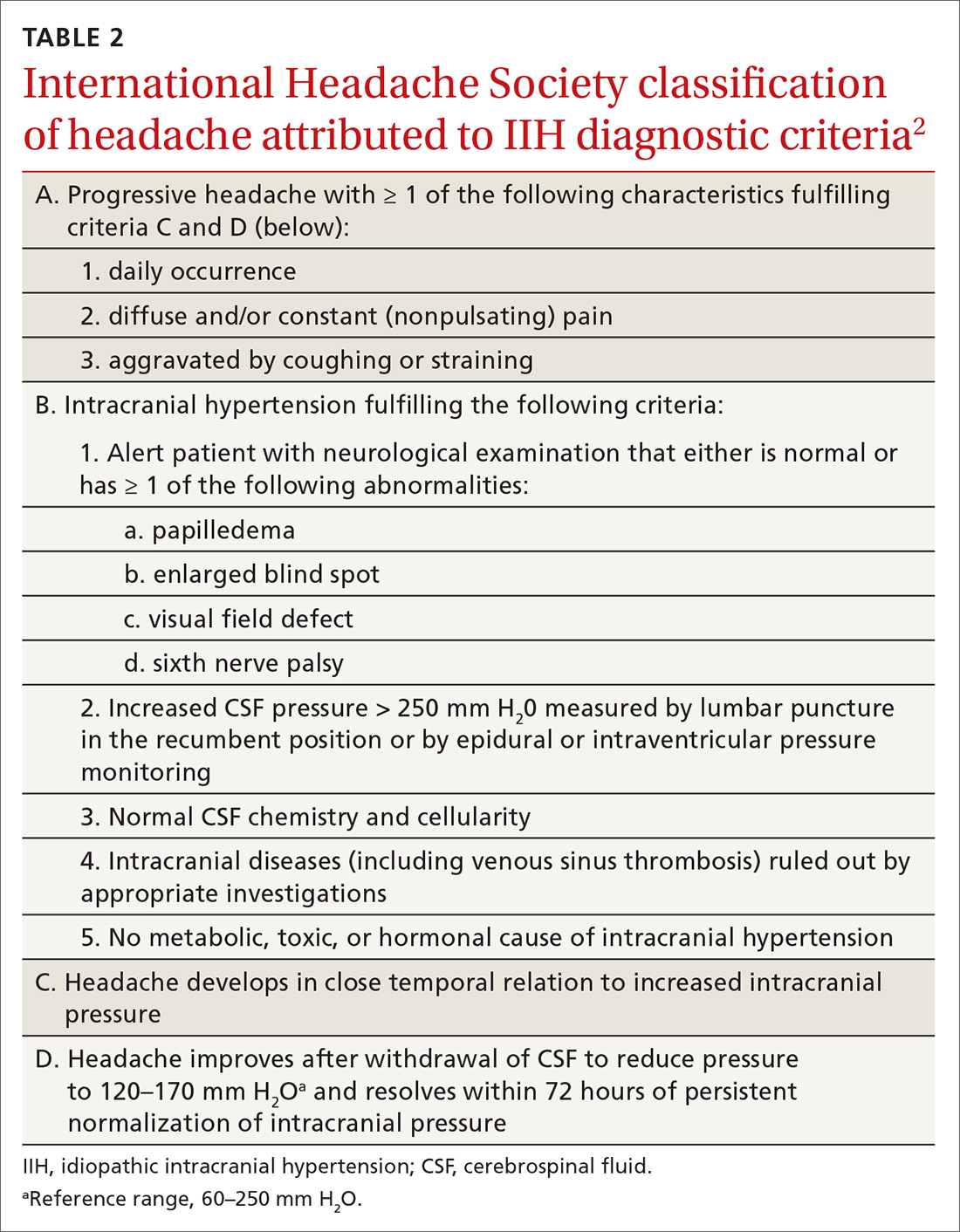

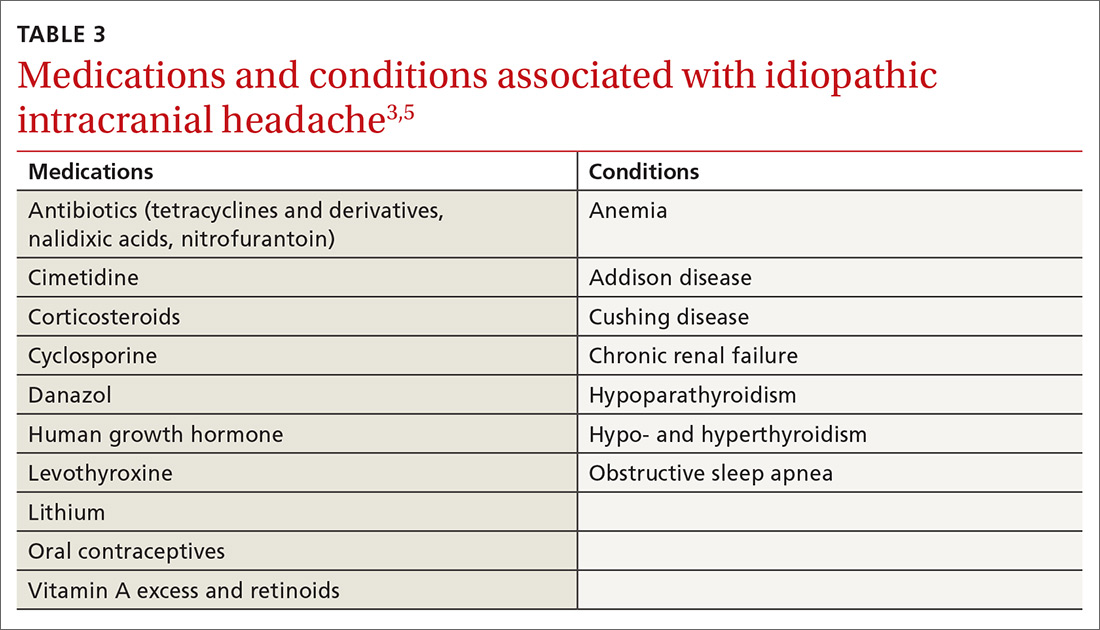

IIH, previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, is defined by signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) without obvious cause on neuroimaging (TABLE 12-5). It is well documented that IIH is consequential and can result in vision loss and intractable chronic headaches.5,6 Older terms such as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension are therefore no longer recommended because they are considered misleading and not reflective of the severity of potential injury caused by the condition3,4,6 IIH is considered a diagnosis of exclusion requiring certain criteria to be met (TABLE 22). Although the etiology of IIH is unclear, associations have been made between IIH and various medications and conditions2-5,7 (TABLE 33,5).

Classically, IIH affects women who are obese and of childbearing age, but studies have shown that this condition also can affect men and children—albeit less frequently.3,5-7 The incidence of IIH in the general population is between 0.03 to 2.36/100,000 people per year, but in women, the incidence is 0.65 to 4.65/100,000 per year.6 Furthermore, females who are obese have an incidence of 2.7 to 19.3/100,000 per year.6

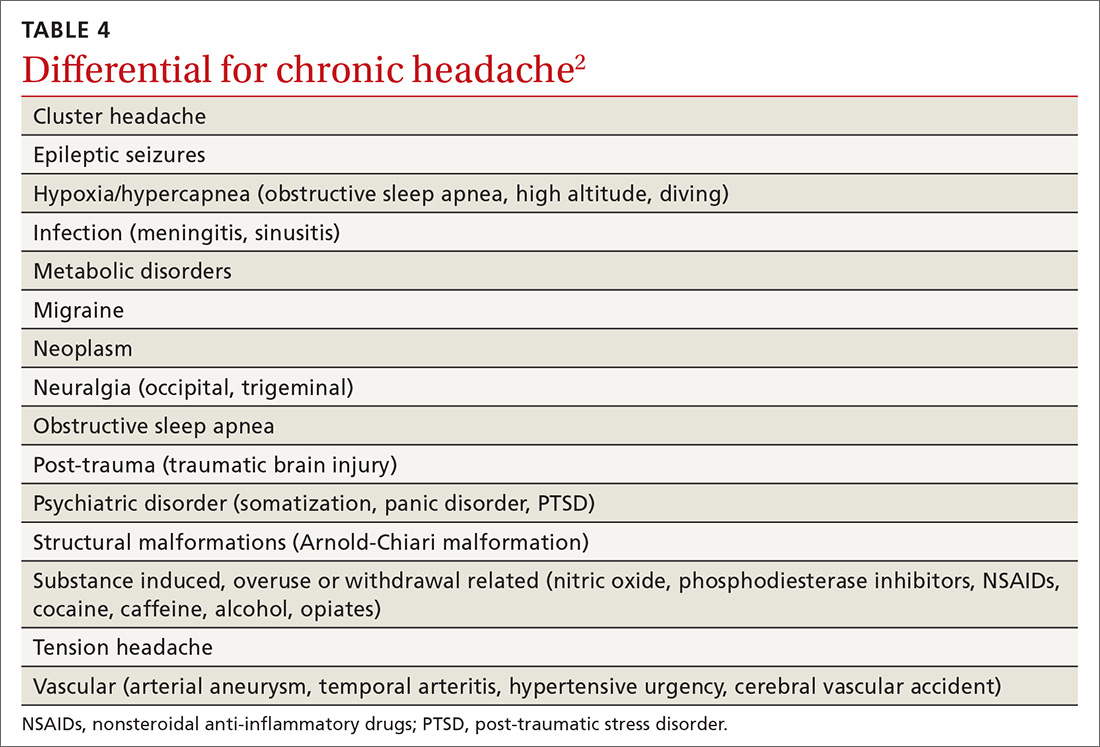

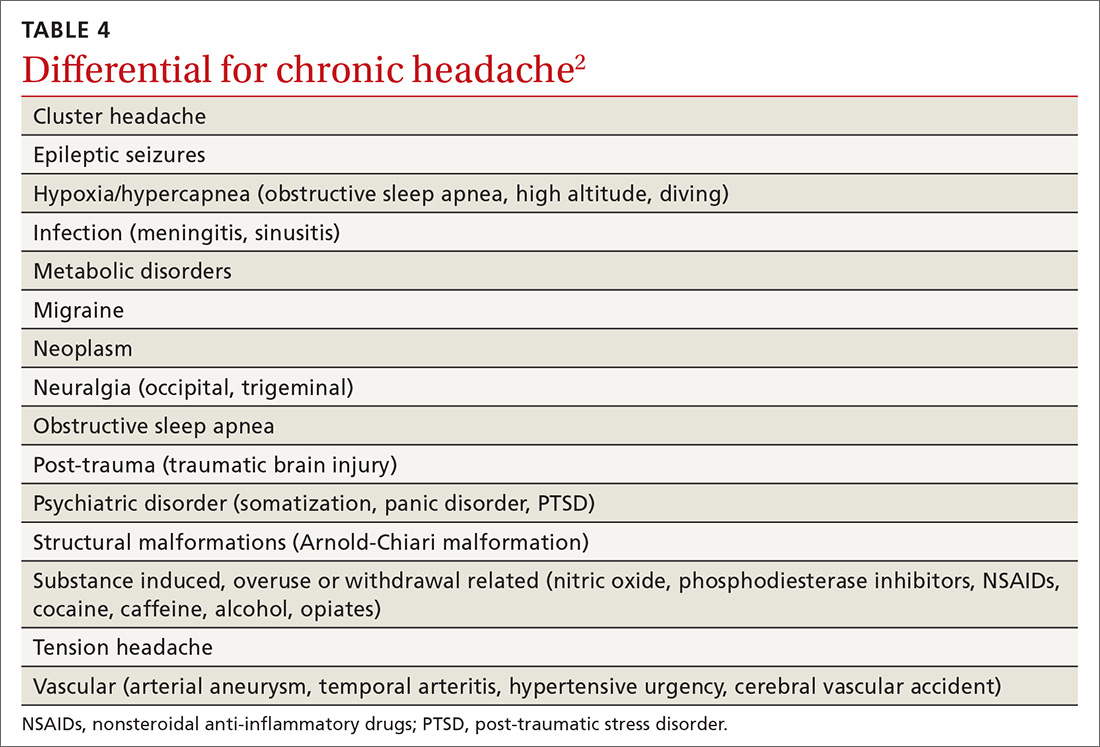

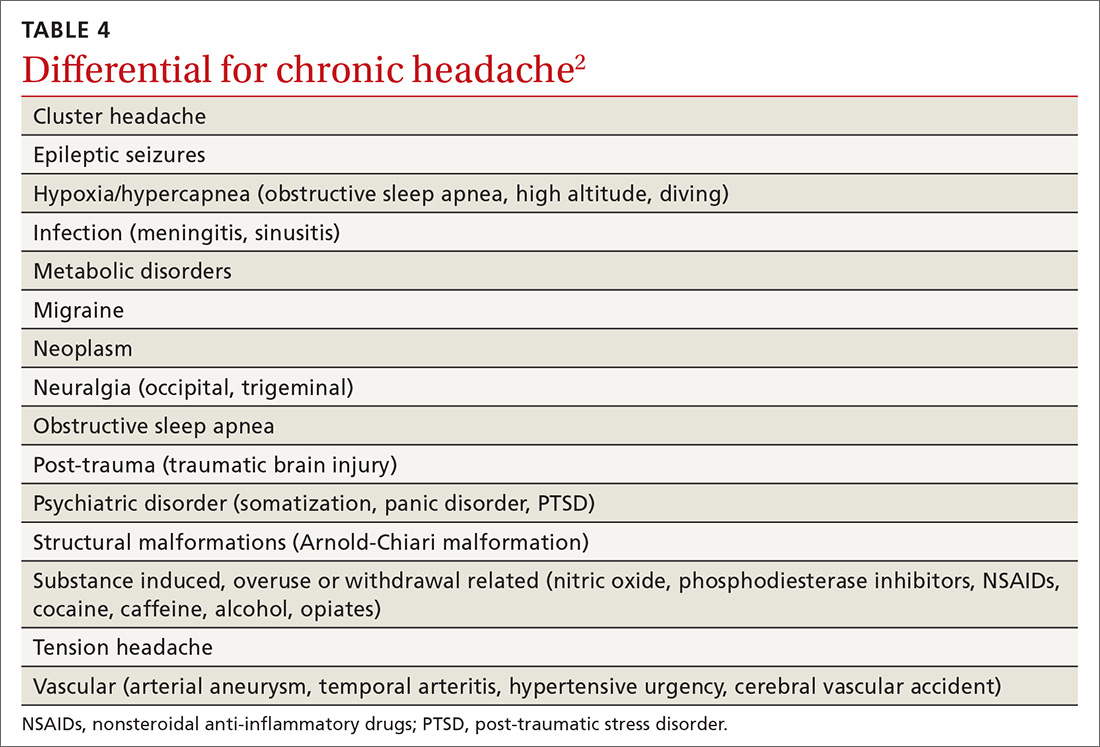

Headache is the most common symptom of IIH. Unfortunately, the differential diagnosis of headache is vast; thus, a careful history is needed to narrow the field3,5-7 (TABLE 42). Associated symptoms of transient visual changes, pulsatile tinnitus, neck and back pain, nausea, vomiting, photo/phonophobia, and findings of abducens nerve palsy or papilledema—while nonspecific— should raise suspicion for elevated ICP and IIH, especially in women who are obese.2-8 Once IIH is suspected, an urgent diagnosis and treatment is necessary to prevent permanent vision loss.3,4,6

Headache with findings of papilledema warrants neuroimaging, preferably with MRI, to rule out intracranial mass and hydrocephalus.1,2,5 MRV also is recommended to assess for intracranial venous thrombosis, an alternate cause for papilledema and increased ICP.1,2,4,5

Continue to: Recently, a classification of IIH...

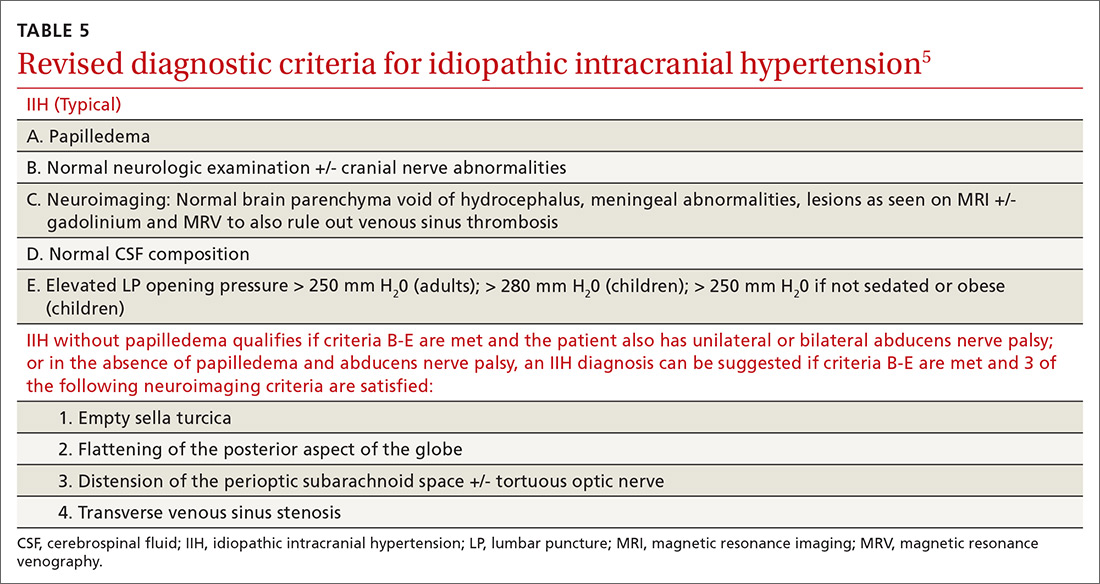

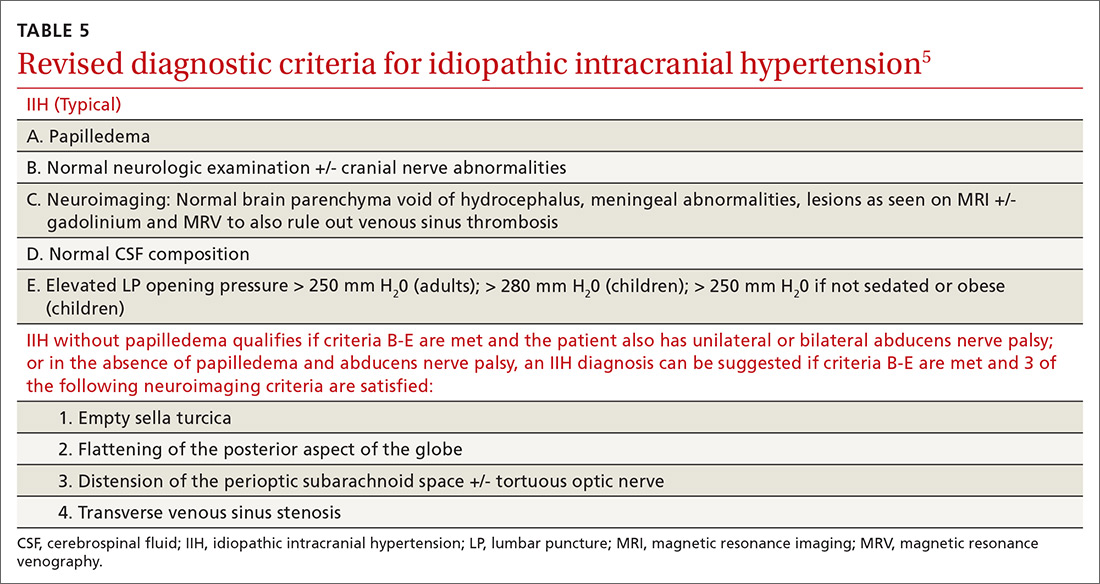

Recently, a classification of IIH without papilledema has been acknowledged by the International Headache Society.2,8 Specific MRI findings have been suggested to help make this diagnosis5,9 (TABLE 55).

TREATMENT FOR IIH CAN BE MEDICAL OR SURGICAL

Medications associated with IIH should be discontinued.7 The first-line medication for IIH is acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor that works in the choroid plexus to decrease cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production and thus, lower ICP.3,6 An adult dose of 1 to 2 g/day3,4,6 is tolerated well, but can be increased to 4 g/day,10 if necessary. Weight loss via diet and exercise or bariatric surgery has been shown to be effective in patients who are obese and have been given a diagnosis of IIH.3,4

Topiramate also has been suggested as a treatment option, based on its usefulness in weight loss and because of its action as a weak carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.3,6 Also, LP has therapeutic merit—although relief is only short-term.3,6 Patients who fail medical therapy and have intractable headache or progressive visual loss appear to benefit from optic nerve sheath fenestration.3,7,8

Our patient experienced notable improvement in her headache after LP. Her OCP was discontinued, a diuretic regimen started, and weight loss counseling was provided. Prior to discharge, the patient was seen by a neuro-ophthalmologist for perimetry, a visual field test that assesses for acute vision loss and establishes a baseline for follow-up monitoring of vision.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Headache is a common condition that may be challenging to correctly diagnose. A thorough history and neurological examination, including fundoscopy, are essential in the evaluation of headache and suspected IIH. In the primary care setting, limited time, lack of mydriatic agents, suboptimal lighting, and practitioner inexperience may pose challenges for funduscopic examination. Ophthalmoscopes incorporating new technology to expand and magnify the examiner’s field of view may facilitate this exam.11 A global rise in the prevalence of obesity underscores a need for primary care providers to be compulsive about their clinical evaluation when symptoms suspicious of IIH are present. Lastly, if IIH cannot be ruled out confidently, recommend a prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aarti Paltoo, MD, MSc, CCFP, Peel Village Medical Center, 28 Rambler Drive, Brampton, Ontario L6W 1E2 Canada; [email protected]

1. Lee SC, Lueck CJ. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in adults. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:278-283.

2. International Headache Society. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2003:1-232.

3. Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:488-494.

4. Mollan SP, Markey KA, Benzimra JD, et al. A practical approach to diagnosis, assessment and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:380-390.

5. Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81:1159-1165.

6. Julayanont P, Karukote A, Ruthirago D, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: ongoing clinical challenges and future prospects. J Pain Res. 2016;9:87-99.

7. Friedman DI, Digre KB. Headache medicine meets neuro-ophthalmology: exam techniques and challenging cases. Headache. 2013;53:703-716.

8. Digre KB, Nakamoto BK, Warner JE, et al. A comparison of idiopathic intracranaial hypertension with and without papilledema. Headache. 2009;49:185-193.

9. Digre KB. Imaging characteristics of IIH: are they reliable? Cephalagia. 2013;33:1067-1069.

10. Horton J. Acetazolamide for pseudotumor cerebri--evidence from the NORDIC trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1618-1619.

11. Petrushkin H, Barsam A, Mavrakakis M, et al. Optic disc assessment in the emergency department: a comparative study between the PanOptic and direct ophthalmoscopes. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:1007-1008.

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to our office complaining of headaches that started 6 weeks earlier. Initially the headache was throbbing, nonpositional, infrequent, and intermittent, lasting 15 to 45 minutes, often starting in the neck and migrating towards the right frontotemporal region. During the week prior to presentation, the headaches became daily and constant, with brief periods of relief after the patient took ibuprofen 400 mg 4 times a day as needed. The patient reported associated nausea, a sensation of pressure changes in the ears, and intermittent dimming of vision in the right eye (sometimes independent of headache). The patient denied photophobia and phonophobia. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive pill (OCP). She had no prior history of headaches.

Physical examination showed a blood pressure of 148/66 mm Hg, body mass index of 44.38, muscle tenderness in the neck and upper back, and no focal neurological findings. Funduscopic examination was unsuccessful. A working diagnosis of atypical migraine was made, but because of unilateral visual disturbance the patient was referred to Ophthalmology for further evaluation. The following day, ophthalmological consultation found bilateral papilledema and the patient was admitted to our hospitalist service via the Emergency Department. She subsequently was referred to inpatient Neurology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) with contrast of the brain showed possible stenosis at the junction of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses but no mass lesion nor venous sinus thrombosis. Lumbar puncture (LP) revealed an opening pressure of 650 mm H20 (reference range, 60–250 mm H2O).1 A diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) was made.

DISCUSSION

IIH, previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, is defined by signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) without obvious cause on neuroimaging (TABLE 12-5). It is well documented that IIH is consequential and can result in vision loss and intractable chronic headaches.5,6 Older terms such as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension are therefore no longer recommended because they are considered misleading and not reflective of the severity of potential injury caused by the condition3,4,6 IIH is considered a diagnosis of exclusion requiring certain criteria to be met (TABLE 22). Although the etiology of IIH is unclear, associations have been made between IIH and various medications and conditions2-5,7 (TABLE 33,5).

Classically, IIH affects women who are obese and of childbearing age, but studies have shown that this condition also can affect men and children—albeit less frequently.3,5-7 The incidence of IIH in the general population is between 0.03 to 2.36/100,000 people per year, but in women, the incidence is 0.65 to 4.65/100,000 per year.6 Furthermore, females who are obese have an incidence of 2.7 to 19.3/100,000 per year.6

Headache is the most common symptom of IIH. Unfortunately, the differential diagnosis of headache is vast; thus, a careful history is needed to narrow the field3,5-7 (TABLE 42). Associated symptoms of transient visual changes, pulsatile tinnitus, neck and back pain, nausea, vomiting, photo/phonophobia, and findings of abducens nerve palsy or papilledema—while nonspecific— should raise suspicion for elevated ICP and IIH, especially in women who are obese.2-8 Once IIH is suspected, an urgent diagnosis and treatment is necessary to prevent permanent vision loss.3,4,6

Headache with findings of papilledema warrants neuroimaging, preferably with MRI, to rule out intracranial mass and hydrocephalus.1,2,5 MRV also is recommended to assess for intracranial venous thrombosis, an alternate cause for papilledema and increased ICP.1,2,4,5

Continue to: Recently, a classification of IIH...

Recently, a classification of IIH without papilledema has been acknowledged by the International Headache Society.2,8 Specific MRI findings have been suggested to help make this diagnosis5,9 (TABLE 55).

TREATMENT FOR IIH CAN BE MEDICAL OR SURGICAL

Medications associated with IIH should be discontinued.7 The first-line medication for IIH is acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor that works in the choroid plexus to decrease cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production and thus, lower ICP.3,6 An adult dose of 1 to 2 g/day3,4,6 is tolerated well, but can be increased to 4 g/day,10 if necessary. Weight loss via diet and exercise or bariatric surgery has been shown to be effective in patients who are obese and have been given a diagnosis of IIH.3,4

Topiramate also has been suggested as a treatment option, based on its usefulness in weight loss and because of its action as a weak carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.3,6 Also, LP has therapeutic merit—although relief is only short-term.3,6 Patients who fail medical therapy and have intractable headache or progressive visual loss appear to benefit from optic nerve sheath fenestration.3,7,8

Our patient experienced notable improvement in her headache after LP. Her OCP was discontinued, a diuretic regimen started, and weight loss counseling was provided. Prior to discharge, the patient was seen by a neuro-ophthalmologist for perimetry, a visual field test that assesses for acute vision loss and establishes a baseline for follow-up monitoring of vision.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Headache is a common condition that may be challenging to correctly diagnose. A thorough history and neurological examination, including fundoscopy, are essential in the evaluation of headache and suspected IIH. In the primary care setting, limited time, lack of mydriatic agents, suboptimal lighting, and practitioner inexperience may pose challenges for funduscopic examination. Ophthalmoscopes incorporating new technology to expand and magnify the examiner’s field of view may facilitate this exam.11 A global rise in the prevalence of obesity underscores a need for primary care providers to be compulsive about their clinical evaluation when symptoms suspicious of IIH are present. Lastly, if IIH cannot be ruled out confidently, recommend a prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aarti Paltoo, MD, MSc, CCFP, Peel Village Medical Center, 28 Rambler Drive, Brampton, Ontario L6W 1E2 Canada; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 22-year-old woman presented to our office complaining of headaches that started 6 weeks earlier. Initially the headache was throbbing, nonpositional, infrequent, and intermittent, lasting 15 to 45 minutes, often starting in the neck and migrating towards the right frontotemporal region. During the week prior to presentation, the headaches became daily and constant, with brief periods of relief after the patient took ibuprofen 400 mg 4 times a day as needed. The patient reported associated nausea, a sensation of pressure changes in the ears, and intermittent dimming of vision in the right eye (sometimes independent of headache). The patient denied photophobia and phonophobia. Her only medication was an oral contraceptive pill (OCP). She had no prior history of headaches.

Physical examination showed a blood pressure of 148/66 mm Hg, body mass index of 44.38, muscle tenderness in the neck and upper back, and no focal neurological findings. Funduscopic examination was unsuccessful. A working diagnosis of atypical migraine was made, but because of unilateral visual disturbance the patient was referred to Ophthalmology for further evaluation. The following day, ophthalmological consultation found bilateral papilledema and the patient was admitted to our hospitalist service via the Emergency Department. She subsequently was referred to inpatient Neurology.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with and without contrast was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance venography (MRV) with contrast of the brain showed possible stenosis at the junction of the transverse and sigmoid sinuses but no mass lesion nor venous sinus thrombosis. Lumbar puncture (LP) revealed an opening pressure of 650 mm H20 (reference range, 60–250 mm H2O).1 A diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) was made.

DISCUSSION

IIH, previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, is defined by signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) without obvious cause on neuroimaging (TABLE 12-5). It is well documented that IIH is consequential and can result in vision loss and intractable chronic headaches.5,6 Older terms such as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension are therefore no longer recommended because they are considered misleading and not reflective of the severity of potential injury caused by the condition3,4,6 IIH is considered a diagnosis of exclusion requiring certain criteria to be met (TABLE 22). Although the etiology of IIH is unclear, associations have been made between IIH and various medications and conditions2-5,7 (TABLE 33,5).

Classically, IIH affects women who are obese and of childbearing age, but studies have shown that this condition also can affect men and children—albeit less frequently.3,5-7 The incidence of IIH in the general population is between 0.03 to 2.36/100,000 people per year, but in women, the incidence is 0.65 to 4.65/100,000 per year.6 Furthermore, females who are obese have an incidence of 2.7 to 19.3/100,000 per year.6

Headache is the most common symptom of IIH. Unfortunately, the differential diagnosis of headache is vast; thus, a careful history is needed to narrow the field3,5-7 (TABLE 42). Associated symptoms of transient visual changes, pulsatile tinnitus, neck and back pain, nausea, vomiting, photo/phonophobia, and findings of abducens nerve palsy or papilledema—while nonspecific— should raise suspicion for elevated ICP and IIH, especially in women who are obese.2-8 Once IIH is suspected, an urgent diagnosis and treatment is necessary to prevent permanent vision loss.3,4,6

Headache with findings of papilledema warrants neuroimaging, preferably with MRI, to rule out intracranial mass and hydrocephalus.1,2,5 MRV also is recommended to assess for intracranial venous thrombosis, an alternate cause for papilledema and increased ICP.1,2,4,5

Continue to: Recently, a classification of IIH...

Recently, a classification of IIH without papilledema has been acknowledged by the International Headache Society.2,8 Specific MRI findings have been suggested to help make this diagnosis5,9 (TABLE 55).

TREATMENT FOR IIH CAN BE MEDICAL OR SURGICAL

Medications associated with IIH should be discontinued.7 The first-line medication for IIH is acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor that works in the choroid plexus to decrease cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production and thus, lower ICP.3,6 An adult dose of 1 to 2 g/day3,4,6 is tolerated well, but can be increased to 4 g/day,10 if necessary. Weight loss via diet and exercise or bariatric surgery has been shown to be effective in patients who are obese and have been given a diagnosis of IIH.3,4

Topiramate also has been suggested as a treatment option, based on its usefulness in weight loss and because of its action as a weak carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.3,6 Also, LP has therapeutic merit—although relief is only short-term.3,6 Patients who fail medical therapy and have intractable headache or progressive visual loss appear to benefit from optic nerve sheath fenestration.3,7,8

Our patient experienced notable improvement in her headache after LP. Her OCP was discontinued, a diuretic regimen started, and weight loss counseling was provided. Prior to discharge, the patient was seen by a neuro-ophthalmologist for perimetry, a visual field test that assesses for acute vision loss and establishes a baseline for follow-up monitoring of vision.7

THE TAKEAWAY

Headache is a common condition that may be challenging to correctly diagnose. A thorough history and neurological examination, including fundoscopy, are essential in the evaluation of headache and suspected IIH. In the primary care setting, limited time, lack of mydriatic agents, suboptimal lighting, and practitioner inexperience may pose challenges for funduscopic examination. Ophthalmoscopes incorporating new technology to expand and magnify the examiner’s field of view may facilitate this exam.11 A global rise in the prevalence of obesity underscores a need for primary care providers to be compulsive about their clinical evaluation when symptoms suspicious of IIH are present. Lastly, if IIH cannot be ruled out confidently, recommend a prompt evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aarti Paltoo, MD, MSc, CCFP, Peel Village Medical Center, 28 Rambler Drive, Brampton, Ontario L6W 1E2 Canada; [email protected]

1. Lee SC, Lueck CJ. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in adults. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:278-283.

2. International Headache Society. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2003:1-232.

3. Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:488-494.

4. Mollan SP, Markey KA, Benzimra JD, et al. A practical approach to diagnosis, assessment and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:380-390.

5. Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81:1159-1165.

6. Julayanont P, Karukote A, Ruthirago D, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: ongoing clinical challenges and future prospects. J Pain Res. 2016;9:87-99.

7. Friedman DI, Digre KB. Headache medicine meets neuro-ophthalmology: exam techniques and challenging cases. Headache. 2013;53:703-716.

8. Digre KB, Nakamoto BK, Warner JE, et al. A comparison of idiopathic intracranaial hypertension with and without papilledema. Headache. 2009;49:185-193.

9. Digre KB. Imaging characteristics of IIH: are they reliable? Cephalagia. 2013;33:1067-1069.

10. Horton J. Acetazolamide for pseudotumor cerebri--evidence from the NORDIC trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1618-1619.

11. Petrushkin H, Barsam A, Mavrakakis M, et al. Optic disc assessment in the emergency department: a comparative study between the PanOptic and direct ophthalmoscopes. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:1007-1008.

1. Lee SC, Lueck CJ. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure in adults. J Neuroophthalmol. 2014;34:278-283.

2. International Headache Society. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2003:1-232.

3. Biousse V, Bruce BB, Newman NJ. Update on the pathophysiology and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:488-494.

4. Mollan SP, Markey KA, Benzimra JD, et al. A practical approach to diagnosis, assessment and management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2014;14:380-390.

5. Friedman DI, Liu GT, Digre KB. Revised diagnostic criteria for the pseudotumor cerebri syndrome in adults and children. Neurology. 2013;81:1159-1165.

6. Julayanont P, Karukote A, Ruthirago D, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: ongoing clinical challenges and future prospects. J Pain Res. 2016;9:87-99.

7. Friedman DI, Digre KB. Headache medicine meets neuro-ophthalmology: exam techniques and challenging cases. Headache. 2013;53:703-716.

8. Digre KB, Nakamoto BK, Warner JE, et al. A comparison of idiopathic intracranaial hypertension with and without papilledema. Headache. 2009;49:185-193.

9. Digre KB. Imaging characteristics of IIH: are they reliable? Cephalagia. 2013;33:1067-1069.

10. Horton J. Acetazolamide for pseudotumor cerebri--evidence from the NORDIC trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1618-1619.

11. Petrushkin H, Barsam A, Mavrakakis M, et al. Optic disc assessment in the emergency department: a comparative study between the PanOptic and direct ophthalmoscopes. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:1007-1008.