User login

A Veteran Presenting With Leg Swelling, Dyspnea, and Proteinuria

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

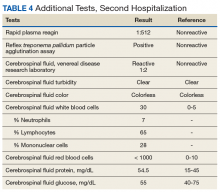

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.

Dr. William, what is his long-term renal prognosis? Do you expect that his acute episode of membranous nephropathy will have permanent effects on his renal function?

► Dr. William. His rapid response to therapy for neurosyphilis provides evidence for this etiology of his renal dysfunction and glomerulonephritis. His long-term prognosis is quite good if the syphilis is the only reason for him to have renal disease. The renal damage is often reversible in these cases. However, given his prior extensive NSAID exposure and history of hypertension, he may be at higher risk for chronic kidney disease than an otherwise healthy patient, especially after an episode of acute kidney injury. Therefore, his renal function should continue to be monitored as an outpatient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank this veteran for sharing his story and allowing us to learn from this unusual case for the benefit of our future patients.

1. Rennke H, Denker BM. Renal Pathophysiology: The Essentials. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

2. Maas RJ, Deegens JK, Smeets B, Moeller MJ, Wetzels JF. Minimal change disease and idiopathic FSGS: manifestations of the same disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):768-776.

3. Beck LH Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):11-21.

4. Rennke HG. Secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47(2):643-656.

5. Nawaz FA, Larsen CP, Troxell ML. Membranous nephropathy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):1012-1017.

6. Pillay A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Syphilis Summit—Diagnostics and laboratory issues. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(9S)(suppl 1):S13-S16.

7. Levett PN, Fonseca K, Tsang RS, et al. Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network laboratory guidelines for the use of serological tests (excluding point-of-care tests) for the diagnosis of syphilis in Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(suppl A):6A-12A.

8. Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular syphilis—eight jurisdictions, United States, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(43):1185-1188.

9. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2015;64(RR3):1-137. [Erratum in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924.]

10. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical advisory: ocular syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Updated March 24, 2016. Accessed August 12, 2019.

11. Braunstein GD, Lewis EJ, Galvanek EG, Hamilton A, Bell WR. The nephrotic syndrome associated with secondary syphilis: an immune deposit disease. Am J Med. 1970;48:643-648.1.

12. Handoko ML, Duijvestein M, Scheepstra CG, de Fijter CW. Syphilis: a reversible cause of nephrotic syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii:bcr2012008279

13. Krane NK, Espenan P, Walker PD, Bergman SM, Wallin JD. Renal disease and syphilis: a report of nephrotic syndrome with minimal change disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9(2):176-179.

14. Bhorade MS, Carag HB, Lee HJ, Potter EV, Dunea G. Nephropathy of secondary syphilis: a clinical and pathological spectrum. JAMA. 1971;216(7):1159-1166.

15. Hunte W, al-Ghraoui F, Cohen RJ. Secondary syphilis and the nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(7):1351-1355.

16. Gamble CN, Reardan JB. Immunopathogenesis of syphilitic glomerulonephritis. Elution of antitreponemal antibody from glomerular immune-complex deposits. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(9):449-454.

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.

Dr. William, what is his long-term renal prognosis? Do you expect that his acute episode of membranous nephropathy will have permanent effects on his renal function?

► Dr. William. His rapid response to therapy for neurosyphilis provides evidence for this etiology of his renal dysfunction and glomerulonephritis. His long-term prognosis is quite good if the syphilis is the only reason for him to have renal disease. The renal damage is often reversible in these cases. However, given his prior extensive NSAID exposure and history of hypertension, he may be at higher risk for chronic kidney disease than an otherwise healthy patient, especially after an episode of acute kidney injury. Therefore, his renal function should continue to be monitored as an outpatient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank this veteran for sharing his story and allowing us to learn from this unusual case for the benefit of our future patients.

*This article has been corrected to include a missing author.

Case Presentation. A 63-year-old male with well-controlled HIV (CD4 count 757, undetectable viral load), epilepsy, and hypertension presented to the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) emergency department with 1 week of bilateral leg swelling and exertional shortness of breath. He reported having no fever, cough, chest pain, pain with inspiration and orthopnea. There was no personal or family history of pulmonary embolism. He reported weight gain but was unable to quantify how much. He also reported flare up of chronic knee pain, without swelling for which he had taken up to 4 tablets of naproxen daily for several weeks. His physical examination was notable for a heart rate of 105 beats per minute and bilateral pitting edema to his knees. Laboratory testing revealed a creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, which was increased from a baseline of 1.0 mg/dL (Table 1), and a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg (Table 2). A renal ultrasound showed normal-sized kidneys without hydronephrosis or obstructing renal calculi. The patient was admitted for further workup of his dyspnea and acute kidney injury.

► Jonathan Li, MD, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC). Dr. William, based on the degree of proteinuria and edema, a diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made. How is nephrotic syndrome defined, and how is it distinguished from glomerulonephritis?

► Jeffrey William, MD, Nephrologist, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The pathophysiology of nephrotic disease and glomerulonephritis are quite distinct, resulting in symptoms and systemic manifestations that only slightly overlap. Glomerulonephritis is characterized by inflammation of the endothelial cells of the trilayered glomerular capillary, with a resulting active urine sediment with red blood cells, white blood cells, and casts. Nephrotic syndrome mostly affects the visceral epithelial cells of the glomerular capillary, commonly referred to as podocytes, and hence, the urine sediment in nephrotic disease is often inactive. Patients with nephrotic syndrome have nephrotic-range proteinuria (excretion of > 3.5 g per 24 h or a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio > 3.5 g in the steady state) and both hypoalbuminemia (< 3 g/dL) and peripheral edema. Lipiduria and hyperlipidemia are common findings in nephrotic syndrome but are not required for a clinical diagnosis.1 In contrast, glomerulonephritis is defined by a constellation of findings that include renal insufficiency (often indicated by an elevation in blood urea nitrogen and creatinine), hypertension, hematuria, and subnephrotic range proteinuria. In practice, patients may fulfill criteria of both nephrotic and nephritic syndromes, but the preponderance of clinical evidence often points one way or the other. In this case, nephrotic syndrome was diagnosed based on the urine protein-to-creatinine ratio of 7.8 mg/mg, hypoalbuminemia, and edema.

► Dr. Li. What would be your first-line workup for evaluation of the etiology of this patient’s nephrotic syndrome?

► Dr. William. Rather than memorizing a list of etiologies of nephrotic syndrome, it is essential to consider the pathophysiology of heavy proteinuria. Though the glomerular filtration barrier is extremely complex and defects in any component can cause proteinuria, disruption of the podocyte is often involved. Common disease processes that chiefly target the podocyte include minimal change disease, primary focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and membranous nephropathy, all by differing mechanisms. Minimal change disease and idiopathic/primary FSGS are increasingly thought to be at differing points on a spectrum of the same disease.2 Secondary FSGS, on the other hand, is a progressive disease, commonly resulting from longstanding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity in adults. Membranous nephropathy can also be either primary or secondary. Primary membranous nephropathy is chiefly caused by a circulating IgG4 antibody to the podocyte membrane antigen PLA2R (M-type phospholipase A2 receptor), whereas secondary membranous nephropathy can be caused by a variety of systemic etiologies, including autoimmune disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), certain malignancies, chronic infections (eg, hepatitis B and C), and many medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-5 Paraprotein deposition diseases can also cause glomerular damage leading to nephrotic-range proteinuria.

Given these potential diagnoses, a careful history should be taken to assess exposures and recent medication use. Urine sediment evaluation is essential in the evaluation of nephrotic syndrome to determine if there is an underlying nephritic process. Select serologies may be sent to look for autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and common viral exposures like hepatitis B or C. Serum and urine protein electrophoreses would be appropriate initial tests of suspected paraprotein-related diseases. Other serologies, such as antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies or antiglomerular basement membrane antibodies, would not necessarily be indicated here given the lack of hematuria and presence of nephrotic-range proteinuria.

► Dr. Li. The initial evaluation was notable for an erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 120 (mm/h) and a weakly positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:40. The remainder of his initial workup did not reveal an etiology for his nephrotic syndrome (Table 3).

Dr. William, is there a role for starting urgent empiric steroids in nephrotic syndrome while workup is ongoing? If so, do the severity of proteinuria and/or symptoms play a role or is this determination based on something else?

► Dr. William. Edema is a primary symptom of nephrotic syndrome and can often be managed with diuretics alone. If a clear medication-mediated cause is suspected, discontinuation of this agent may result in spontaneous improvement without steroid treatment. However,in cases where an etiology is unclear and there are serious thrombotic complications requiring anticoagulation, and a renal biopsy is deemed to be too risky, then empiric steroid therapy may be necessary. Children with new-onset nephrotic syndrome are presumed to have minimal change disease, given its prevalence in this patient population, and are often given empiric steroids without obtaining a renal biopsy. However, in the adult population, a renal biopsy can typically be performed quickly and safely, with pathology results interpreted within days. In this patient, since a diagnosis was unclear and there was no contraindication to renal biopsy, a biopsy should be obtained before consideration of steroids.

► Dr. Li. Steroids were deferred in anticipation of renal biopsy, which showed stage I membranous nephropathy, suggestive of membranous lupus nephritis Class V. The deposits were strongly reactive for immunoglobuline G (IgG), IgA, and complement 1q (C1q), showed co-dominant staining for IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3, and were weakly positive for the PLA2 receptor. Focal intimal arteritis in a small interlobular vessel was seen.

Dr. William, the pathology returned suggestive of lupus nephritis. Does the overall clinical picture fit with lupus nephritis?

► Dr. William. Given the history and a rather low ANA, the diagnosis of lupus nephritis seems unlikely. The lack of IgG4 and PLA2R staining in the biopsy suggests that this membranous pattern on the biopsy is likely to be secondary to a systemic etiology, but further investigation should be pursued.

► Dr. Li. The patient was discharged after the biopsy with a planned outpatient nephrology follow-up to discuss results and treatment. He was prescribed an oral diuretic, and his symptoms improved. Several days after discharge, he developed blurry vision and was evaluated in the Ophthalmology clinic. On fundoscopy, he was found to have acute papillitis, a form of optic neuritis. As part of initial evaluation of infectious etiologies of papillitis, ophthalmology recommended testing for syphilis.

Dr. Strymish, when we are considering secondary syphilis, what is the recommended approach to diagnostic testing?

► Judith Strymish, MD, Infectious Diseases, BIDMC, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School. The diagnosis of syphilis is usually made through serologic testing of blood specimens. Methods that detect the spirochete directly like dark-field smears are not readily available. Serologic tests include treponemal tests (eg, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA]) and nontreponemal tests (eg, rapid plasma reagin [RPR]). One needs a confirmatory test because either test is associated with false positives. Either test can be done first. Most laboratories, including those at VABHS are now performing treponemal tests first as these have become more cost-effective.6 The TPPA treponemal test was found to have a lower false negative rate in primary syphilis compared with that of nontreponemal tests.7 Nontreponemal tests can be followed for response to therapy. If a patient has a history of treated syphilis, a nontreponemal test should be sent, since the treponemal test will remain positive for life.

If there is clinical concern for neurosyphilis, cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent (CSF) treponemal antibody needs to be sampled and sent for the nontreponemal venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test. The VDRL is highly specific for neurosyphilis but not as sensitive. Cerebrospinal fluid fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA) may also be sent; it is very sensitive but not very specific for neurosyphilis.

► Dr. Li. An RPR returned positive at 1:512 (was negative 14 months prior on a routine screening test), with positive reflex TPPA (Table 4). A diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. Dr. Strymish, at this point, what additional testing and treatment is necessary?

► Dr. Strymish. With papillitis and a very high RPR, we need to assume that he has ophthalmic syphilis. This can occur in any stage of syphilis, but his eye findings and high RPR are consistent with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmic syphilis has been on the upswing, even more than is expected with recent increases in syphilis cases.8 Ophthalmic syphilis is considered a form of neurosyphilis. A lumbar puncture and treatment for neurosyphilis is recommended.9,10

► Dr. Li. A lumbar puncture was performed, and his CSF was VDRL positive. This confirmed a diagnosis of neurosyphilis (Table 4). The patient was treated for neurosyphilis with IV penicillin. The patient shared that he had episodes of unprotected oral sexual activity within the past year and approximately 1 year ago, he came in close contact (but no sexual activity) with a person who had a rash consistent with syphilis.Dr. William, syphilis would be a potential unifying diagnosis of his renal and ophthalmologic manifestations. Is syphilis known to cause membranous nephropathy?

► Dr. William. Though it is uncommon, the nephrotic syndrome is a well-described complication of secondary syphilis.11,12 Syphilis has been shown to cause nephrotic syndrome in a variety of ways. Case reports abound linking syphilis to minimal change disease and other glomerular diseases.13,14 A case report from 1993 shows a membranous pattern of glomerular disease similar to this case.15 As a form of secondary membranous nephropathy, the immunofluorescence pattern can demonstrate staining similar to the “full house” seen in lupus nephritis (IgA, IgM, and C1q, in addition to IgG and C3).16 This explains the initial interpretation of this patient’s biopsy, as lupus nephritis would be a much more common etiology of secondary membranous nephropathy than is acute syphilis with this immunofluorescence pattern. However, the data in this case are highly suggestive of a causal relationship between secondary syphilis and membranous nephropathy.

► Dr. Li. Dr. Strymish, how should this patient be screened for syphilis reinfection, and at what intervals would you recommend?

► Dr. Strymish. He will need follow-up testing to make sure that his syphilis is effectively treated. If CSF pleocytosis was present initially, a CSF examination should be repeated every 6 months until the cell count is normal. He will also need follow-up for normalization of his RPR. Persons with HIV infection and primary or secondary syphilis should be evaluated clinically and serologically for treatment failure at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months after therapy according to US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.9

His treponemal test for syphilis will likely stay positive for life. His RPR should decrease significantly with effective treatment. It makes sense to screen with RPR alone as long as he continues to have risk factors for acquiring syphilis. Routine syphilis testing is recommended for pregnant women, sexually active men who have sex with men, sexually active persons with HIV, and persons taking PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) for HIV prevention. He should be screened at least yearly for syphilis.

► Dr. Li. Over the next several months, the patient’s creatinine normalized and his proteinuria resolved. His vision recovered, and he has had no further ophthalmologic complications.

Dr. William, what is his long-term renal prognosis? Do you expect that his acute episode of membranous nephropathy will have permanent effects on his renal function?

► Dr. William. His rapid response to therapy for neurosyphilis provides evidence for this etiology of his renal dysfunction and glomerulonephritis. His long-term prognosis is quite good if the syphilis is the only reason for him to have renal disease. The renal damage is often reversible in these cases. However, given his prior extensive NSAID exposure and history of hypertension, he may be at higher risk for chronic kidney disease than an otherwise healthy patient, especially after an episode of acute kidney injury. Therefore, his renal function should continue to be monitored as an outpatient.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank this veteran for sharing his story and allowing us to learn from this unusual case for the benefit of our future patients.

1. Rennke H, Denker BM. Renal Pathophysiology: The Essentials. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

2. Maas RJ, Deegens JK, Smeets B, Moeller MJ, Wetzels JF. Minimal change disease and idiopathic FSGS: manifestations of the same disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):768-776.

3. Beck LH Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):11-21.

4. Rennke HG. Secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47(2):643-656.

5. Nawaz FA, Larsen CP, Troxell ML. Membranous nephropathy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):1012-1017.

6. Pillay A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Syphilis Summit—Diagnostics and laboratory issues. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(9S)(suppl 1):S13-S16.

7. Levett PN, Fonseca K, Tsang RS, et al. Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network laboratory guidelines for the use of serological tests (excluding point-of-care tests) for the diagnosis of syphilis in Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(suppl A):6A-12A.

8. Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular syphilis—eight jurisdictions, United States, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(43):1185-1188.

9. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2015;64(RR3):1-137. [Erratum in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924.]

10. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical advisory: ocular syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Updated March 24, 2016. Accessed August 12, 2019.

11. Braunstein GD, Lewis EJ, Galvanek EG, Hamilton A, Bell WR. The nephrotic syndrome associated with secondary syphilis: an immune deposit disease. Am J Med. 1970;48:643-648.1.

12. Handoko ML, Duijvestein M, Scheepstra CG, de Fijter CW. Syphilis: a reversible cause of nephrotic syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii:bcr2012008279

13. Krane NK, Espenan P, Walker PD, Bergman SM, Wallin JD. Renal disease and syphilis: a report of nephrotic syndrome with minimal change disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9(2):176-179.

14. Bhorade MS, Carag HB, Lee HJ, Potter EV, Dunea G. Nephropathy of secondary syphilis: a clinical and pathological spectrum. JAMA. 1971;216(7):1159-1166.

15. Hunte W, al-Ghraoui F, Cohen RJ. Secondary syphilis and the nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(7):1351-1355.

16. Gamble CN, Reardan JB. Immunopathogenesis of syphilitic glomerulonephritis. Elution of antitreponemal antibody from glomerular immune-complex deposits. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(9):449-454.

1. Rennke H, Denker BM. Renal Pathophysiology: The Essentials. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

2. Maas RJ, Deegens JK, Smeets B, Moeller MJ, Wetzels JF. Minimal change disease and idiopathic FSGS: manifestations of the same disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(12):768-776.

3. Beck LH Jr, Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):11-21.

4. Rennke HG. Secondary membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1995;47(2):643-656.

5. Nawaz FA, Larsen CP, Troxell ML. Membranous nephropathy and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):1012-1017.

6. Pillay A. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Syphilis Summit—Diagnostics and laboratory issues. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(9S)(suppl 1):S13-S16.

7. Levett PN, Fonseca K, Tsang RS, et al. Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network laboratory guidelines for the use of serological tests (excluding point-of-care tests) for the diagnosis of syphilis in Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(suppl A):6A-12A.

8. Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular syphilis—eight jurisdictions, United States, 2014-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(43):1185-1188.

9. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 2015;64(RR3):1-137. [Erratum in MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(33):924.]

10. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical advisory: ocular syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Updated March 24, 2016. Accessed August 12, 2019.

11. Braunstein GD, Lewis EJ, Galvanek EG, Hamilton A, Bell WR. The nephrotic syndrome associated with secondary syphilis: an immune deposit disease. Am J Med. 1970;48:643-648.1.

12. Handoko ML, Duijvestein M, Scheepstra CG, de Fijter CW. Syphilis: a reversible cause of nephrotic syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:pii:bcr2012008279

13. Krane NK, Espenan P, Walker PD, Bergman SM, Wallin JD. Renal disease and syphilis: a report of nephrotic syndrome with minimal change disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;9(2):176-179.

14. Bhorade MS, Carag HB, Lee HJ, Potter EV, Dunea G. Nephropathy of secondary syphilis: a clinical and pathological spectrum. JAMA. 1971;216(7):1159-1166.

15. Hunte W, al-Ghraoui F, Cohen RJ. Secondary syphilis and the nephrotic syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1993;3(7):1351-1355.

16. Gamble CN, Reardan JB. Immunopathogenesis of syphilitic glomerulonephritis. Elution of antitreponemal antibody from glomerular immune-complex deposits. N Engl J Med. 1975;292(9):449-454.

Fatal Drug-Resistant Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus in a 56-Year-Old Immunosuppressed Man (FULL)

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

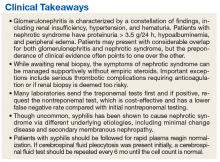

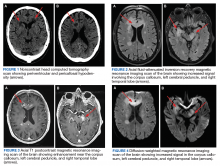

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

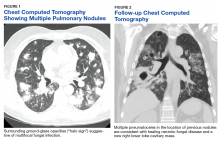

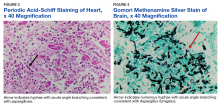

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

1. Upton A, Kirby KA, Carpenter P, Boeckh M, Marr KA. Invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic cell transplantation: outcomes and prognostic factors associated with mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):531-540.

2. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, et al; Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(6):408-415.

3. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Disease Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60.

4. García-Cadenas I, Rivera I, Martino R, et al. Patterns of infection and infection-related mortality in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2017;52(1):107-113.

5. Vermeulen E, Maertens J, De Bel A, et al. Nationwide surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus diseases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(8):4569-4576.

6. Wiederhold NP, Patterson TF. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(5):673-680.

7. Cuenca-Estrella M, Moore CB, Barchiesi F, et al; AFST Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Multicenter evaluation of the reproducibility of the proposed antifungal susceptibility testing method for fermentative yeasts of the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(6):467-474.

8. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, et al; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Antifungal Testing Subcommittee. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for broth microdilution methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3142-3146.

9. Marr KA, Schlamm HT, Herbrecht R, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for invasive aspergillosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):81-89.

10. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(1):584-587.

11. Rajendran R, Mowat E, Jones B, Williams C, Ramage G. Prior in vitro exposure to voriconazole confers resistance to amphotericin B in Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;46(3):342-345.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion

This case of fatal, progressive, invasive, pulmonary aspergillosis demonstrates several important factors in the treatment of patients with this disease. Treatment failure usually relates to any of 4 possible factors: host immune status, severity or burden of disease, appropriate dosing of antifungal agents, and drug resistance. This patient’s immune system was heavily suppressed for a prolonged period. Attempts at reducing immunosuppression to the minimal required dosage to prevent a GVHD flare were unsuccessful and became an unmodifiable risk factor, a major contributor to his demise.

The risks of continuous high-dose immunosuppression in steroid-refractory GVHD is well understood and has been previously demonstrated to have up to 50% 4-year nonrelapse mortality, mainly due to overwhelming bacterial, viral, and fungal infections.4 All attempts should be made to cease or reduce immunosuppression in the setting of a severe infection, although this is sometimes impossible as in this case.

The patient’s disease burden was significant as evidenced by the bilateral, multifocal pulmonary nodules seen on chest imaging and the disseminated disease found at postmortem examination. His initial improvement in symptoms with voriconazole and the evolution of his images (with many of his initial pulmonary nodules becoming pneumatoceles) suggested a temporary positive immune response. The authors believe that the Rhizopus in his sputum represents noninvasive colonization of one of his pneumatoceles, because postmortem examination failed to reveal Rhizopus at any other location.

Voriconazole has excellent pulmonary and central nervous system penetration: In this patient serum levels were well within the therapeutic range. His peculiar drug resistance pattern (sensitivity to azoles and resistance to amphotericin) is unusual. Azole resistance in leukemia and patients with HSCT is more common than is amphotericin resistance, with current estimates of azole resistance close to 5%, ranging between 1% and 30%.5,6 Widespread use of antifungal prophylaxis with azoles likely selects for azole resistance.6

Despite this concern of azole resistance, current IDSA guidelines recommend against routine susceptibility testing of Aspergillus to azole therapy because of the current lack of consensus between the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute on break points for resistance patterns.3,7 This is an area of emerging research, and proposed cut points for declaration of resistance do exist in the literature even if not globally agreed on.8

Combination antifungal therapy is an option for treatment in cases of possible drug resistance. Nonetheless, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial comparing voriconazole monotherapy with the combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin failed to demonstrate an overall mortality benefit in the primary analysis, although secondary analysis showed a mortality benefit with combination therapy in patients at highest risk for death.9

Despite the lack of unified standards with susceptibility testing, it may be reasonable to perform such tests in patients with demonstrating progressive disease. In this patient’s case, amphotericin B was added to treat the Rhizopus species found in his sputum, and while not the combination studied in the previously mentioned study, the drug should have provided an additional active agent for Aspergillus should this patient have had azole resistance.

Surprisingly, subsequent testing demonstrated the Aspergillus species to be resistant to amphotericin B. De novo amphotericin B-resistant A fumigates is extremely rare, with an expected incidence of 1% or less.10 The authors believe the patient may have demonstrated induction of amphotericin-B resistance through activation of fungal stress pathways by prior treatment with voriconazole. This has been demonstrated in vitro and should be considered should combination salvage therapy be required for the treatment of a refractory Aspergillus infection especially if patients have received prior treatment with voriconazole.11

Conclusion

This fatal case of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis illustrates the importance of considering the 4 main causes of treatment failure in an infection. Although the patient had a high burden of disease with a rare resistance pattern, he was treated with appropriate and well-dosed therapy. Ultimately, his unmodifiable immunosuppression was likely the driving factor leading to treatment failure and death. The indication for and number of bone marrow transplants continues to increase, thus exposure to and treatment of invasive fungal infections will increase accordingly. As such, providers should ensure that all causes of treatment failure are considered and addressed.

Historically, aspergillosis in patients with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has carried a high mortality rate. However, recent data demonstrate a dramatic improvement in outcomes for patients with HSCT: 90-day survival increased from 22% before 2000 to 45% over the past 15 years.1 Improved outcomes coincide with changes in transplant immunosuppression practices, use of cross-sectional imaging for early disease identification, galactomannan screening, and the development of novel treatment options.

Voriconazole is an azole drug that blocks the synthesis of ergosterol, a vital component of the cellular membrane of fungi. Voriconazole was approved in 2002 after a clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in 50% of patients with invasive aspergillosis in the voriconazole arm vs 30% in the amphotericin B arm at 12 weeks.2 Amphotericin B is a polyene antifungal drug that binds with ergosterol, creating leaks in the cell membrane that lead to cellular demise. Voriconazole quickly became the first-line therapy for invasive aspergillosis and is recommended by both the Infectious Disease Society of American (IDSA) and the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia.3

Case Presentation

A 55-year-old man with high-risk chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) underwent a 10 of 10 human leukocyte antigen allele and antigen-matched peripheral blood allogeneic HSCT with a myeloablative-conditioning regimen of busulfan and cyclophosphamide, along with prophylactic voriconazole, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and acyclovir. After successful engraftment (without significant neutropenia), his posttransplant course was complicated by grade 2 graft vs host disease (GVHD) of the skin, eyes, and liver, which responded well to steroids and tacrolimus. Voriconazole was continued for 5 months until immunosuppression was minimized (tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily). Two months later, the patient’s GVHD worsened, necessitating treatment at an outside hospital with high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) and cyclosporine (300 mg twice daily). Voriconazole prophylaxis was not reinitiated at that time.

One year later, at a routine follow-up appointment, the patient endorsed several weeks of malaise, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The patient’s immunosuppression recently had been reduced to 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone and 100 mg of cyclosporine twice daily. A chest X-ray demonstrated multiple pulmonary nodules; follow-up chest computed tomography (CT) confirmed multiple nodular infiltrates with surrounding ground-glass opacities suspicious with a fungal infection (Figure 1).

Treatment with oral voriconazole (300 mg twice daily) was initiated for probable pulmonary aspergillosis. Cyclosporine (150 mg twice daily) and prednisone (1 mg/kg/d) were continued throughout treatment out of concern for hepatic GVHD. The patient’s symptoms improved over the next 10 days, and follow-up chest imaging demonstrated improvement.

Two weeks after initiation of voriconazole treatment, the patient developed a new productive cough and dyspnea, associated with fevers and chills. Repeat imaging revealed right lower-lobe pneumonia. The serum voriconazole trough level was checked and was 3.1 mg/L, suggesting therapeutic dosing. The patient subsequently developed acute respiratory distress syndrome and required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Repeat BAL sampling demonstrated multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli, a BAL galactomannan level of 2.0 ODI, and negative fungal cultures. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by profound hypoxemia, requiring prone positioning and neuromuscular blockade. He was treated with meropenem and voriconazole. His immunosuppression was reduced, but he rapidly developed acute liver injury from hepatic GVHD that resolved after reinitiation of cyclosporine and prednisone at 0.75 mg/kg/d.

The patient improved over the next 3 weeks and was successfully extubated. Repeat chest CT imaging demonstrated numerous pneumatoceles in the location of previous nodules, consistent with healing necrotic fungal disease, and a new right lower-lobe cavitary mass (Figure 2). Two days after transferring out of the intensive care unit, the patient again developed hypoxemia and fevers to 39° C. Bronchoscopy with BAL of the right lower lobe revealed positive A fumigatus and Rhizopus sp polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, although fungal cultures were positive only for A fumigatus. Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg) was added to voriconazole therapy to treat mucormycosis and to provide a second active agent against A fumigatus.

Unfortunately, the patient’s clinical status continued to deteriorate with signs of progressive respiratory failure and infection despite empiric, broad-spectrum antibiotics and dual antifungal therapy. His serum voriconazole level continued to be therapeutic at 1.9 mg/L. The patient declined reintubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, and he ultimately transitioned to comfort measures and died with his family at the bedside.

Autopsy demonstrated widely disseminated Aspergillus infection as the cause of death, with evidence of myocardial, neural, and vascular invasion of A fumigatus (Figures 3 and 4).

Discussion