User login

Catheter-Directed Retrieval of an Infected Fragment in a Vietnam War Veteran

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

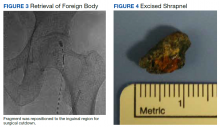

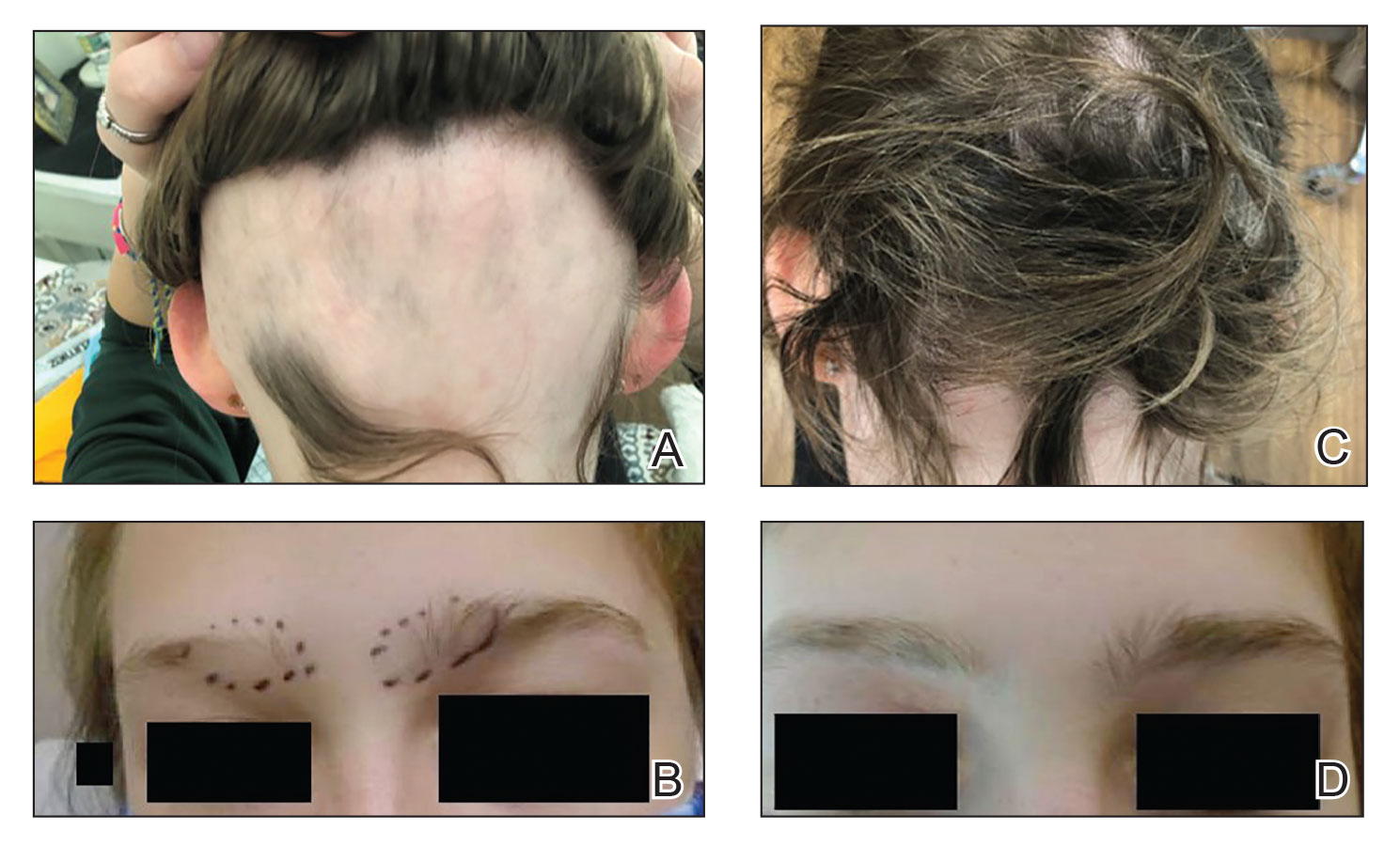

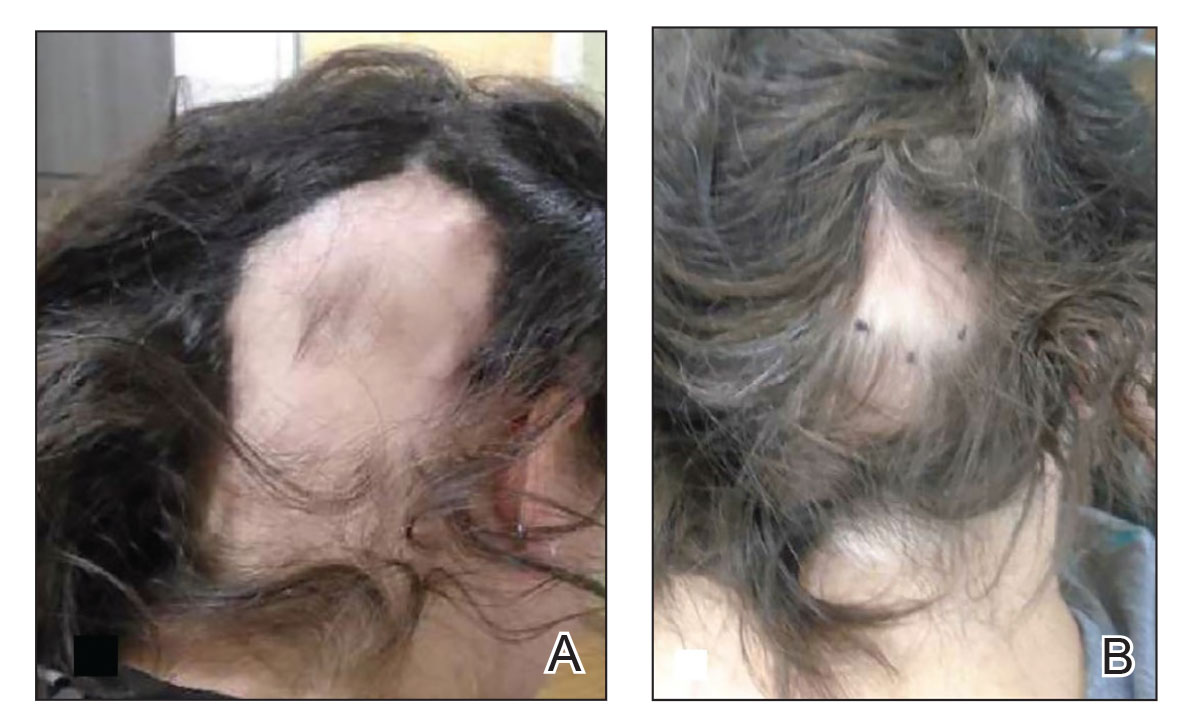

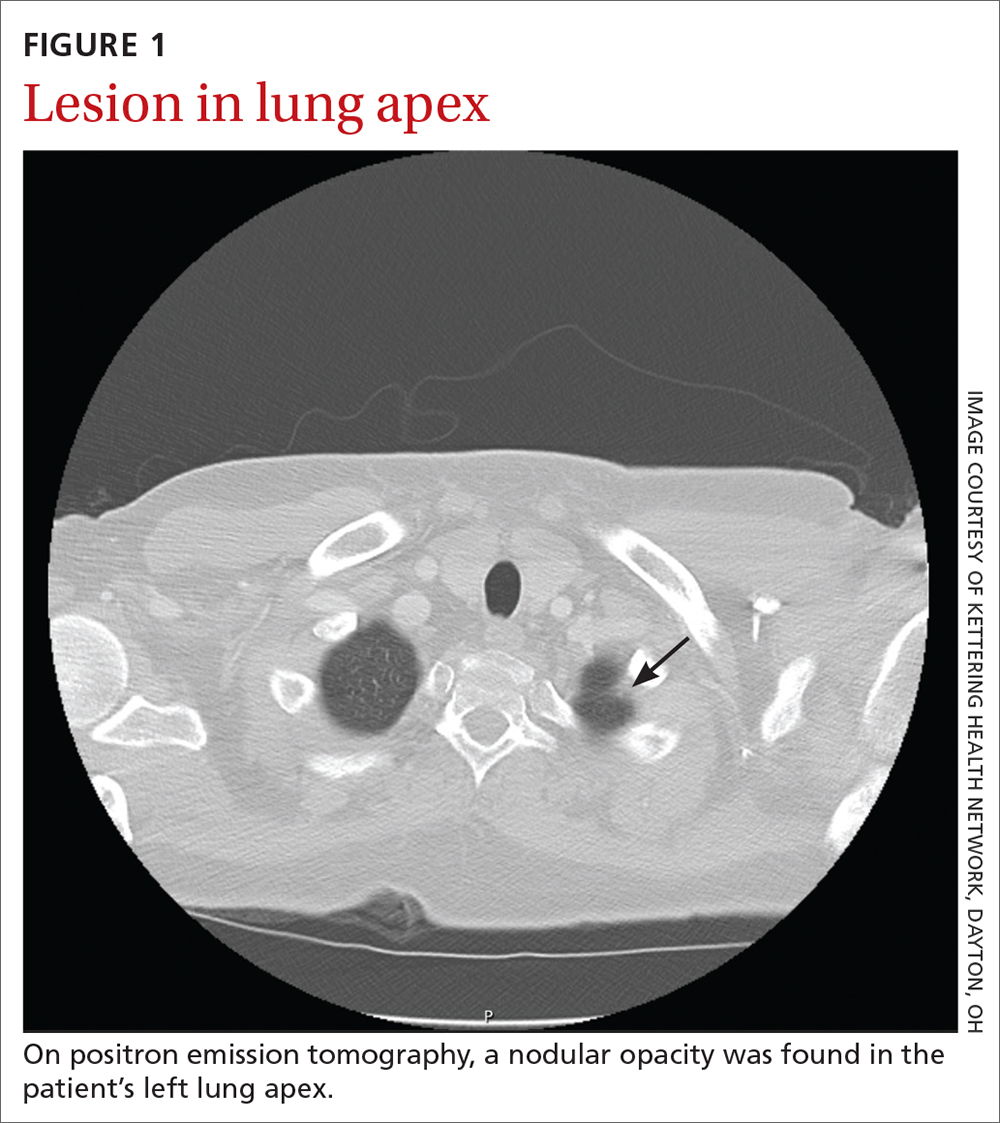

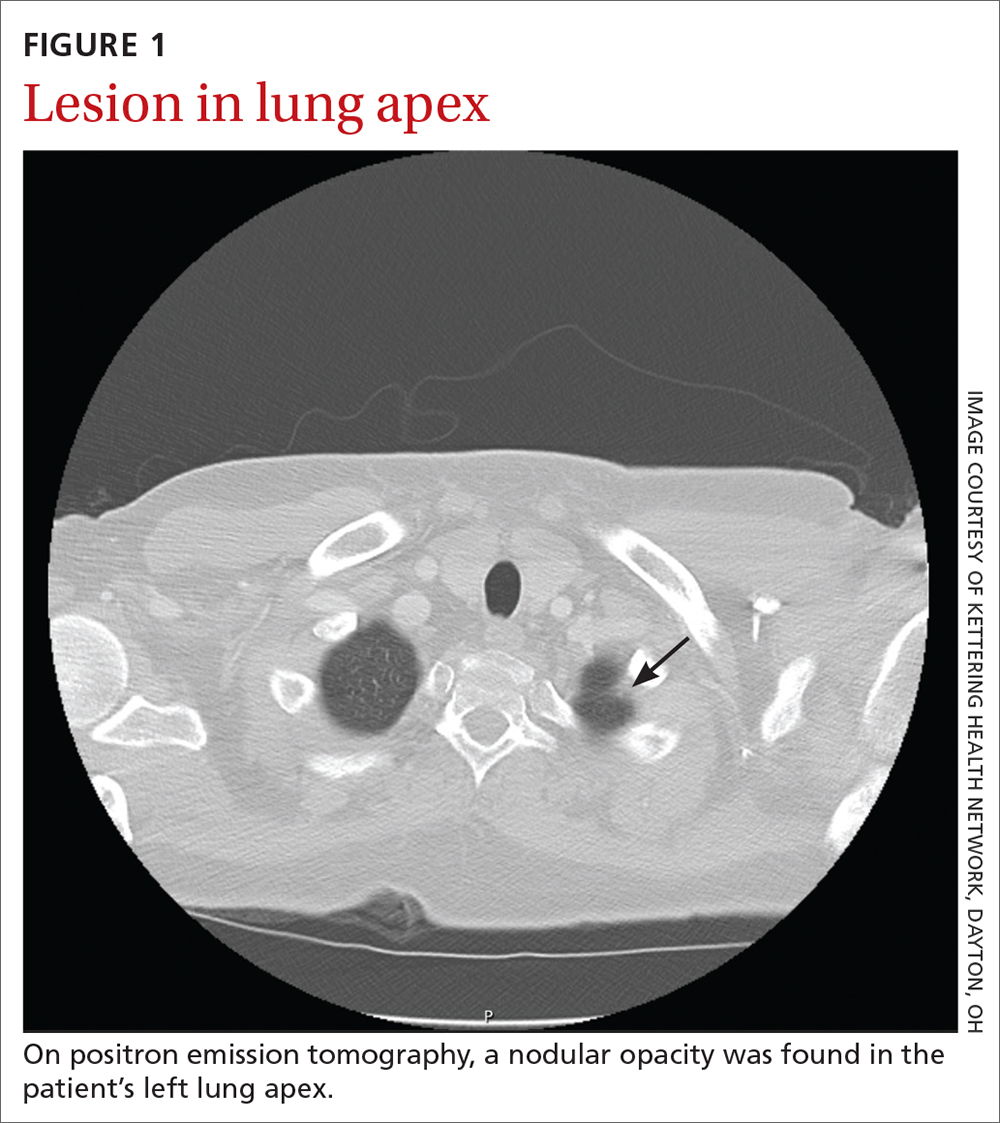

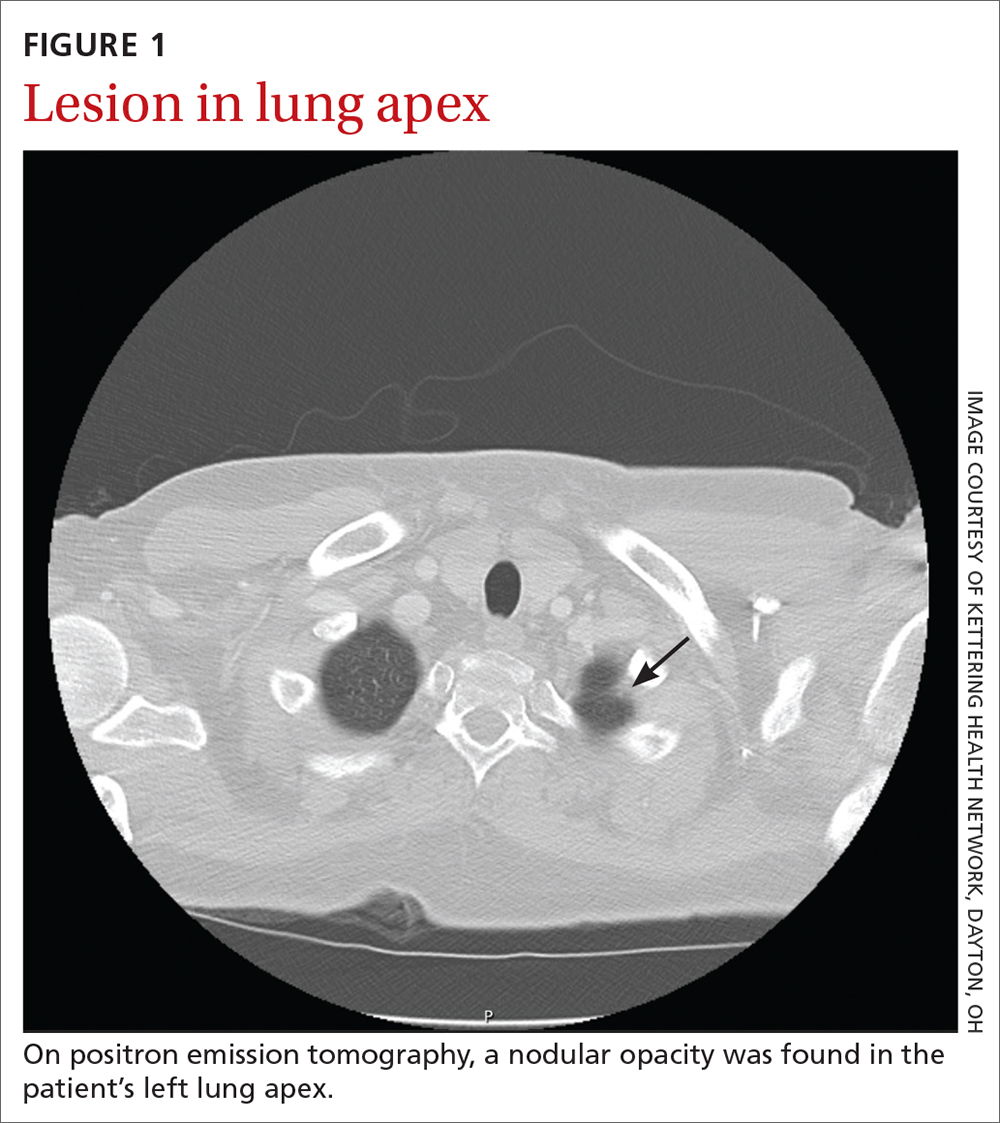

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

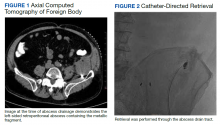

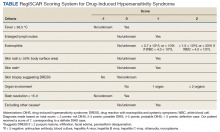

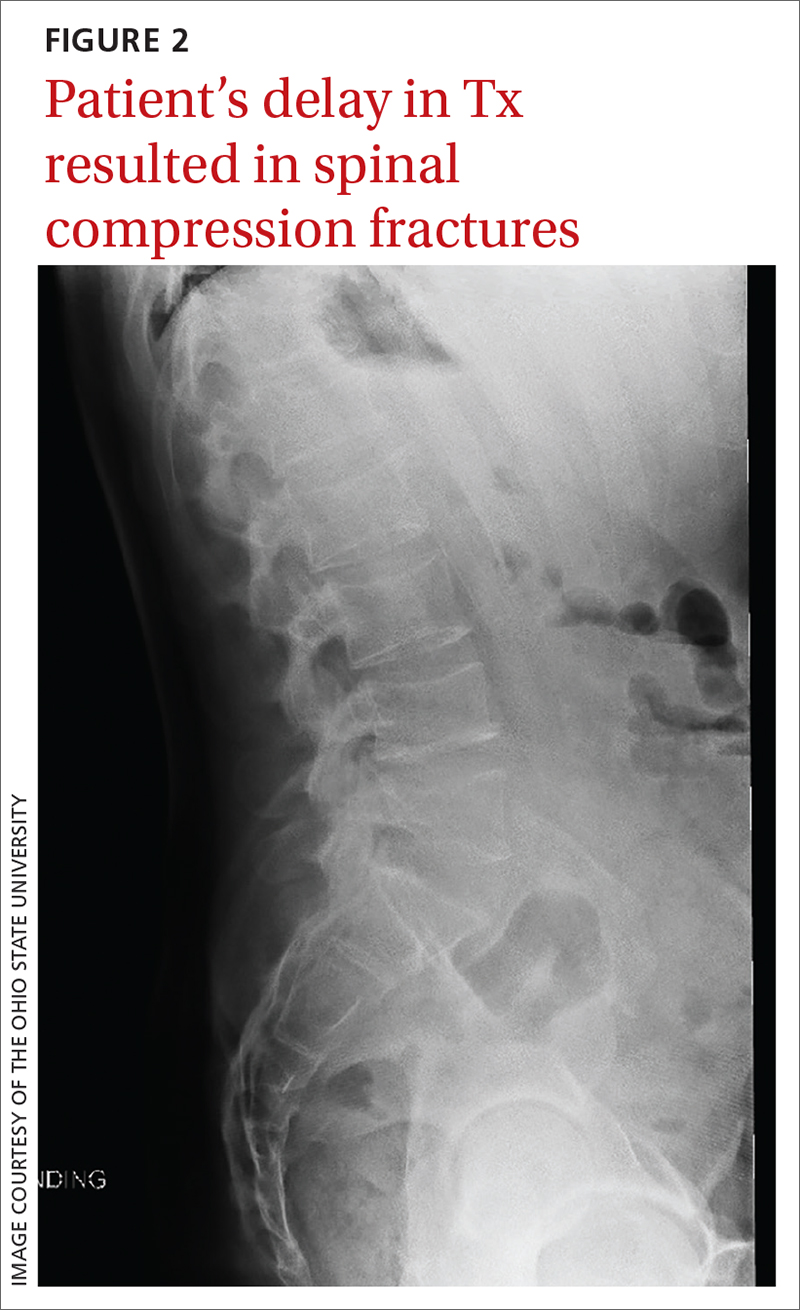

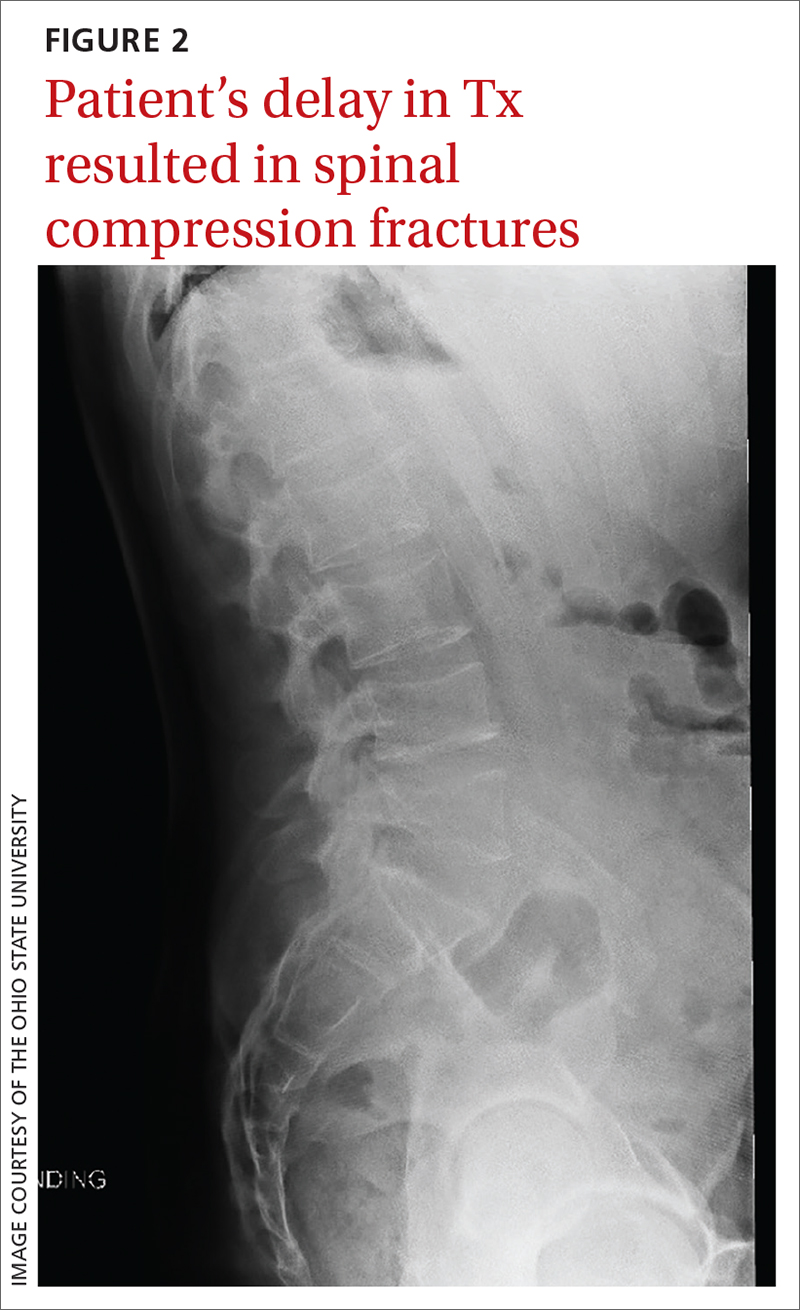

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

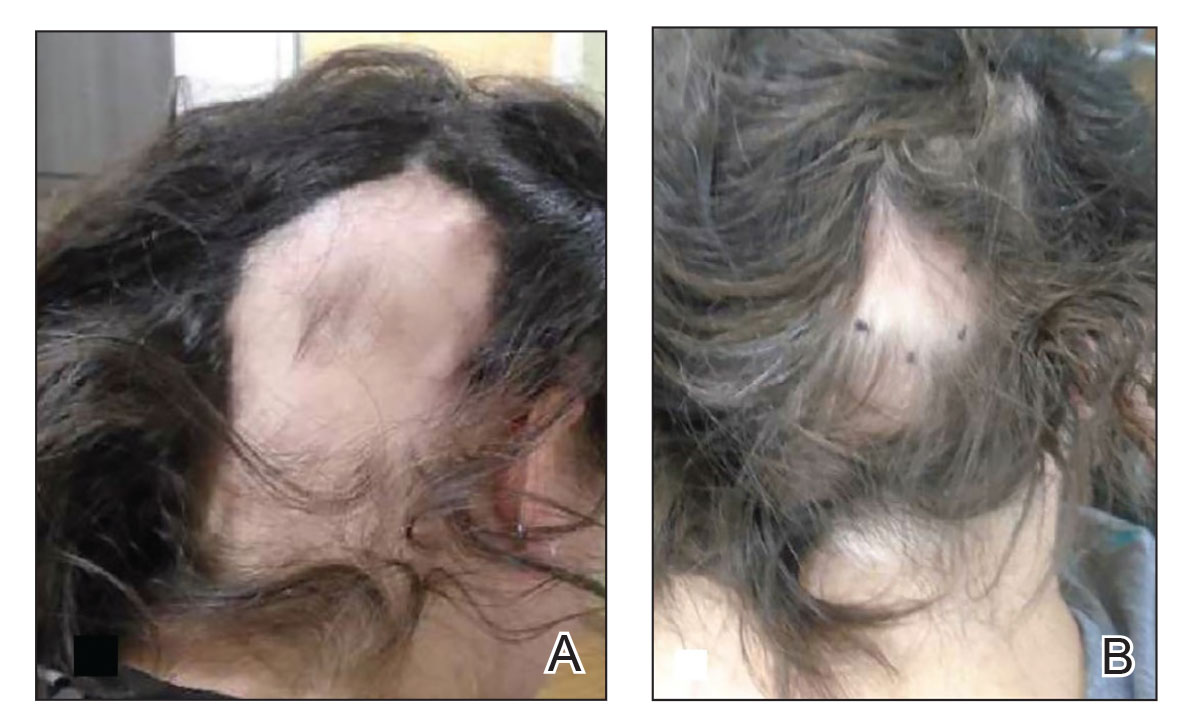

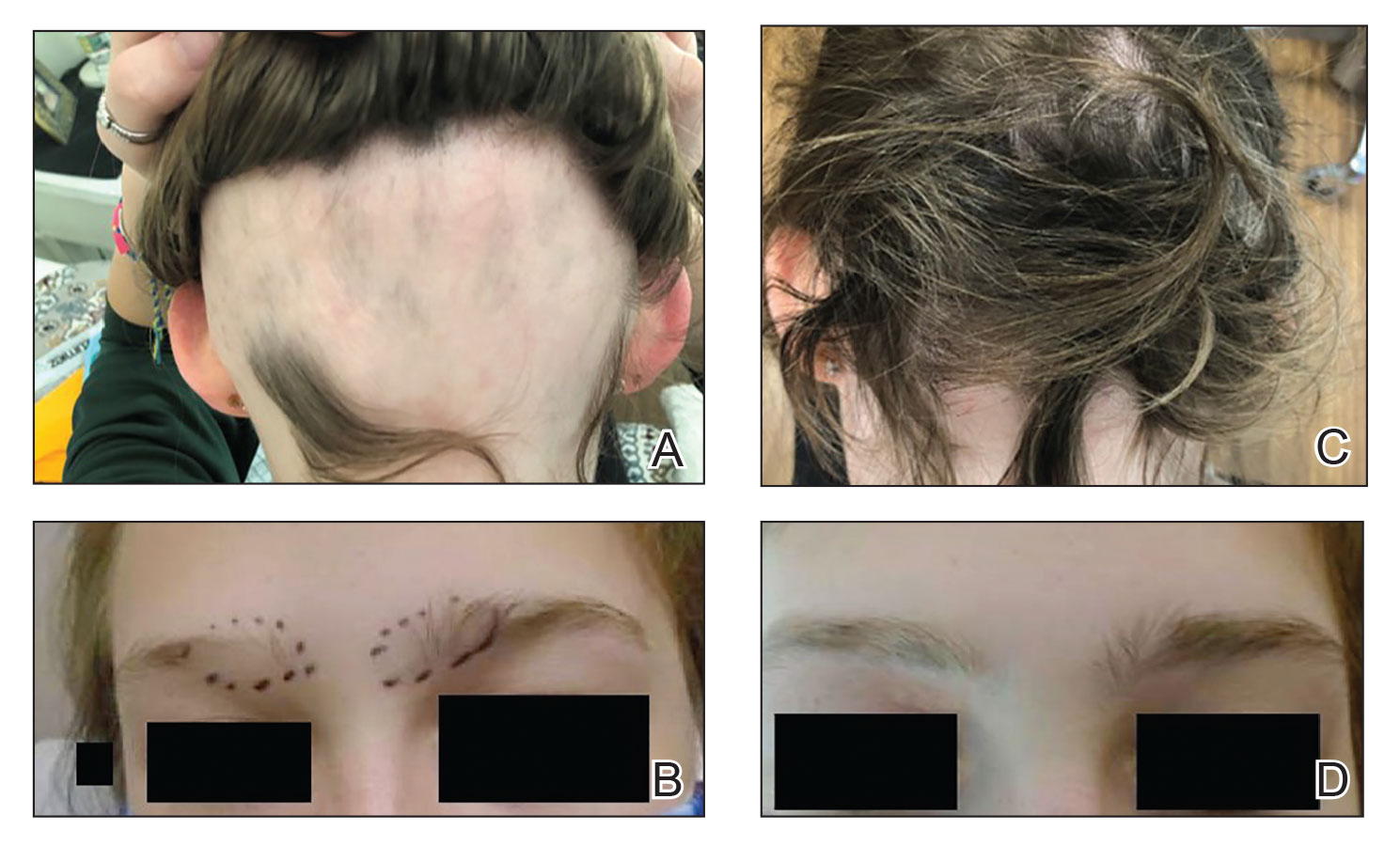

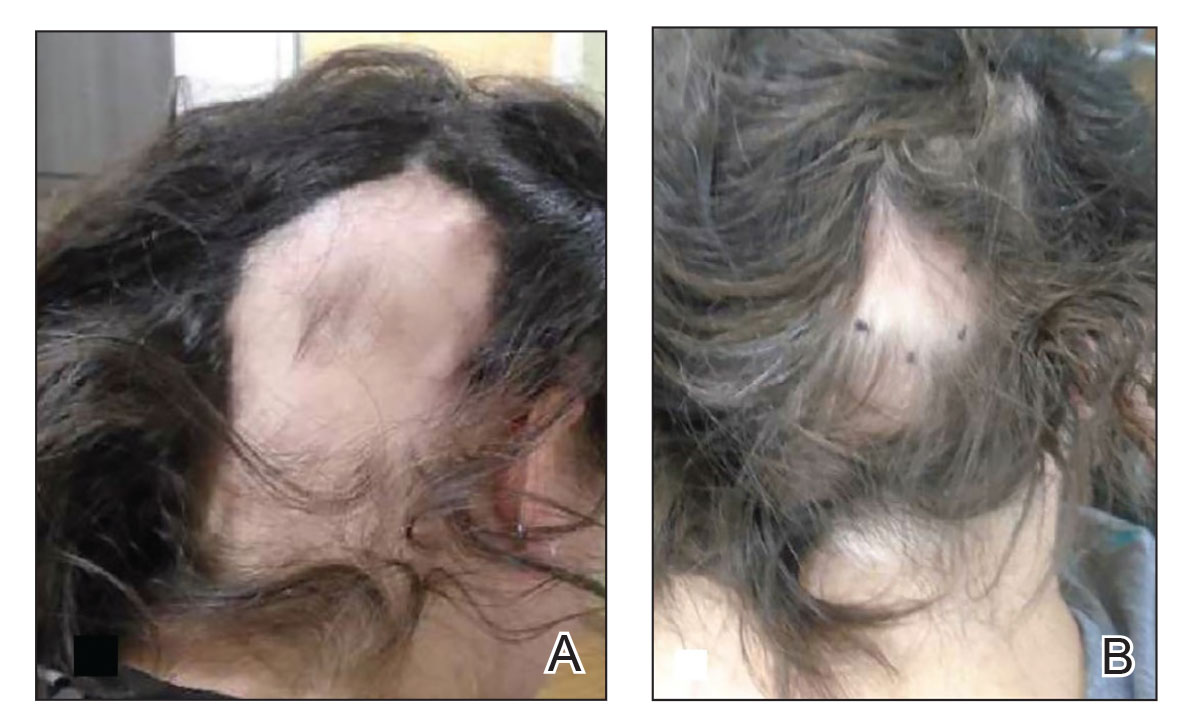

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

Shrapnel injuries are commonly encountered in war zones.1 Shrapnel injuries can remain asymptomatic or become systemic, with health effects of the retained foreign body ranging from local to systemic toxicities depending on the patient’s reaction to the chemical composition and corrosiveness of the fragments in vivo.2 We present a case of a reactivating shrapnel injury in the form of a retroperitoneal infection and subsequent iliopsoas abscess. A collaborative procedure was performed between surgery and interventional radiology to snare and remove the infected fragment and drain the abscess.

Case Presentation

While serving in Vietnam, a soldier sustained a fragment injury to his left lower abdomen. He underwent a laparotomy, small bowel resection, and a temporary ileostomy at the time of the injury. Nearly 50 years later, the patient presented with chronic left lower quadrant pain and a low-grade fever. He was diagnosed clinically in the emergency department (ED) with diverticulitis and treated with antibiotics. The patient initially responded to treatment but returned 6 months later with similar symptoms, low-grade fever, and mild leukocytosis. A computed tomography (CT) scan during that encounter without IV contrast revealed a few scattered colonic diverticula without definite diverticulitis as well as a metallic fragment embedded in the left iliopsoas with increased soft tissue density.

The patient was diagnosed with a pelvic/abdominal wall hematoma and was discharged with pain medication. The patient reported recurrent attacks of left lower quadrant pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits, prompting gastrointestinal consultation and a colonoscopy that was unremarkable. Ten months later, the patient again presented to the ED, with recurrent symptoms, a fever of 102 °F, and leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 11.7 × 109/L. CT scan with IV contrast revealed a large left iliopsoas abscess associated with an approximately 1-cm metallic fragment (Figure 1). A drainage catheter was placed under CT guidance and approximately 270 mL of purulent fluid was drained. Culture of the fluid was positive for Escherichia coli (E coli). Two days after drain placement, the fragment was removed as a joint procedure with interventional radiology and surgery. Using the drainage catheter tract as a point of entry, multiple attempts were made to retrieve the fragment with Olympus EndoJaw endoscopic forceps without success.

Ultimately a stiff directional sheath from a Cook Medical transjugular liver biopsy kit was used with a Merit Medical EnSnare to relocate the fragment to the left inguinal region for surgical excision (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The fragment was removed and swabbed for culture and sensitivity and a BLAKE drain was placed in the evacuated abscess cavity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged the following day. Three days later, culture and sensitivity grew E coli and Acinetobacter, thus confirming infection and a nidus for the surrounding abscess formation. On follow-up with general surgery 7 days later, the patient reported he was doing well, and the drain was removed without difficulty.

Discussion

Foreign body injuries can be benign or debilitating depending on the initial damage, anatomical location of the foreign body, composition of the foreign body, and the patient’s response to it. Retained shrapnel deep within the muscle tissue rarely causes complications. Although many times embedded objects can be asymptomatic and require no further management, migration of the foreign body or the formation of a fistula is possible, causing symptoms and requiring surgical intervention.1 One case involved the formation of a purulent fistula appearing a year after an explosive wound to the lumbosacral spine, which was treated with antimicrobials. Recurrence of the fistula several times after treatment led to surgical removal of the shrapnel along with antibiotic treatment of the osteomyelitis.3 Although uncommon, lead exposure that occurs due to retained foreign body fragments from gunshot or military-related injuries can cause systemic lead toxicity. Symptoms may range from abdominal pain, nausea, and constipation to jaundice and hepatitis.4 The severity has also been stated to correlate with the surface area of the lead exposed for dissolution.5 Migration of foreign bodies and shrapnel to other sites in the body, such as movement from soft tissues into distantly located body cavities, have been reported as well. Such a case involved the spontaneous onset of knee synovitis due to an intra-articular metallic object that was introduced via a blast injury to the upper third of the ipsilateral thigh.1

In this patient’s case, a large intramuscular abscess had formed nearly 50 years after the initial combat injury, requiring drainage of the abscess and removal of the fragment. By snaring the foreign body to a more superficial site, the surgical removal only required a minor incision, decreasing recovery time and the likelihood of postoperative complications that would have been associated with a large retroperitoneal dissection. While loop snare is often the first-line technique for the removal of intravascular foreign bodies, its use in soft tissue retained materials is scarcely reported.6 The more typical uses involve the removal of intraluminal materials, such as partially fractured venous catheters, guide wires, stents, and vena cava filters. The same report mentioned that in all 16 cases of percutaneous foreign body retrieval, no surgical intervention was required.7 In the case of most nonvascular foreign bodies, however, surgical retrieval is usually performed.8

Surgical removal of foreign bodies can be difficult in cases where a foreign body is anatomically located next to vital structures.9 An additional challenge with a sole surgical approach to foreign body retrieval is when it is small in size and lies deep within the soft tissue, as was the case for our patient. In such cases, the surgical procedure can be time consuming and lead to more trauma to the surrounding tissues.10 These factors alone necessitate consideration of postoperative morbidity and mortality.

In our patient, the retained fragment was embedded in the wall of an abscess located retroperitoneally in his iliopsoas muscle. When considering the proximity of the iliopsoas muscle to the digestive tract, urinary tract, and iliac lymph nodes, it is reasonable for infectious material to come in contact with the foreign body from these nearby structures, resulting in secondary infection.11 Surgery was previously considered the first-line treatment for retroperitoneal abscesses until the advent of imaging-guided percutaneous drainage.12

In some instances, surgical drainage may still be attempted, such as if there are different disease processes requiring open surgery or if percutaneous catheter drainage is not technically possible due to the location of the abscess, thick exudate, loculation/septations, or phlegmon. In these cases, laparoscopic drainage as opposed to open surgical drainage can provide the benefits of an open procedure (ie, total drainage and resection of infected tissue) but is less invasive, requires a smaller incision, and heals faster.13 Percutaneous drainage is the current first-line treatment due to the lack of need for general anesthesia, lower cost, and better morbidity and mortality outcomes compared to surgical methods.12 While percutaneous drainage proved to be immediately therapeutic for our patient, the risk of abscess recurrence with the retained infected fragment necessitated coordination of procedures across specialties to provide the best outcome for the patient.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates a multidisciplinary approach to transforming an otherwise large retroperitoneal dissection to a minimally invasive and technically efficient abscess drainage and foreign body retrieval.

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

1. Schroeder JE, Lowe J, Chaimsky G, Liebergall M, Mosheiff R. Migrating shrapnel: a rare cause of knee synovitis. Mil Med. 2010;175(11):929-930. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-09-00254

2. Centeno JA, Rogers DA, van der Voet GB, et al. Embedded fragments from U.S. military personnel—chemical analysis and potential health implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(2):1261-1278. Published 2014 Jan 23. doi:10.3390/ijerph110201261

3. Carija R, Busic Z, Bradaric N, Bulovic B, Borzic Z, Pavicic-Perkovic S. Surgical removal of metallic foreign body (shrapnel) from the lumbosacral spine and the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis: a case report. West Indian Med J. 2014;63(4):373-375. doi:10.7727/wimj.2012.290

4. Grasso I, Blattner M, Short T, Downs J. Severe systemic lead toxicity resulting from extra-articular retained shrapnel presenting as jaundice and hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2017;182(3-4):e1843-e1848. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00231

5. Dillman RO, Crumb CK, Lidsky MJ. Lead poisoning from a gunshot wound: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Med. 1979;66(3):509-514. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(79)91083-0

6. Woodhouse JB, Uberoi R. Techniques for intravascular foreign body retrieval. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(4):888-897. doi:10.1007/s00270-012-0488-8

7. Mallmann CV, Wolf KJ, Wacker FK. Retrieval of vascular foreign bodies using a self-made wire snare. Acta Radiol. 2008;49(10):1124-1128. doi:10.1080/02841850802454741

8. Nosher JL, Siegel R. Percutaneous retrieval of nonvascular foreign bodies. Radiology. 1993;187(3):649-651. doi:10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497610

9. Fu Y, Cui LG, Romagnoli C, Li ZQ, Lei YT. Ultrasound-guided removal of retained soft tissue foreign body with late presentation. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(14):1753-1754. doi:10.4103/0366-6999.209910

10. Liang HD, Li H, Feng H, Zhao ZN, Song WJ, Yuan B. Application of intraoperative navigation and positioning system in the removal of deep foreign bodies in the limbs. Chin Med J (Engl). 2019;132(11):1375-1377. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000253

11. Moriarty CM, Baker RJ. A pain in the psoas. Sports Health. 2016;8(6):568-572. doi:10.1177/1941738116665112

12. Akhan O, Durmaz H, Balcı S, Birgi E, Çiftçi T, Akıncı D. Percutaneous drainage of retroperitoneal abscesses: variables for success, failure, and recurrence. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26(2):124-130. doi:10.5152/dir.2019.19199

13. Hong CH, Hong YC, Bae SH, et al. Laparoscopic drainage as a minimally invasive treatment for a psoas abscess: a single center case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(14):e19640. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019640

Successful Use of Lanadelumab in an Older Patient With Type II Hereditary Angioedema

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disorder affecting about 1 in 67,000 individuals and may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 HAE is characterized by recurring episodes of subcutaneous and/or submucosal edema without urticaria due to an excess of bradykinin.2,3 Autosomal dominant inheritance is present in 75% of patients with HAE and is classified into 2 main types.2 Type I HAE is caused by deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor, accounting for 85% of cases.2 Type II HAE is marked by normal to elevated levels of C1 esterase inhibitor but with reduced activity.2

Cutaneous and abdominal angioedema attacks are the most common presentation.1 However, any location may be affected, including the face, oropharynx, and larynx.1 Only 0.9% of all HAE attacks cause laryngeal edema, but 50% of HAE patients have experienced a laryngeal attack, which may be lethal.1 An angioedema attack can range in severity, depending on the location and degree of edema.3 In addition, patients with HAE often are diagnosed with anxiety and depression secondary to their poor quality of life.4 Thus, long-term prophylaxis of attacks is crucial to reduce the physical and psychological implications.

Previously, HAE was treated with antifibrinolytic agents and attenuated androgens for short- and long-term prophylaxis.1 These treatment modalities are now considered second-line since the development of novel medications with improved efficacy and limited adverse effects (AEs).1 For long-term prophylaxis, subcutaneous and IV C1 esterase inhibitor has been proven effective in both types I and II HAE.1 Another option, lanadelumab, a subcutaneously delivered monoclonal antibody inhibitor of plasma kallikrein, has been proven to decrease the frequency of HAE attacks without significant AEs.5 Lanadelumab works by binding to the active site of plasma kallikrein, which reduces its activity and slows the production of bradykinin.6 This results in decreasing vascular permeability and swelling episodes in patients with HAE.7 Data, however, are limited, specifically regarding patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 This article reports on an older male with type II HAE successfully treated with lanadelumab.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old male patient with hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and aortic aneurysm had recurrent, frequent episodes of severe abdominal pain with a remote history of extremity and scrotal swelling since adolescence. He was misdiagnosed for years and was eventually determined to have HAE at age 75 years after his niece was diagnosed, prompting him to be reevaluated for his frequent bouts of abdominal pain. His laboratory findings were consistent with HAE type II with low C4 (7.8 mg/dL), normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels (24 mg/dL), and low levels of C1 esterase inhibitor activity (28% of normal).

Initially, he described having weekly attacks of abdominal pain that could last 1 to several days. At worst, these attacks would last up to a month, causing a decrease in appetite and weight loss. At age 77 years, he began an on-demand treatment, icatibant, a bradykinin receptor blocker. After initiating icatibant during an acute attack, the pain would diminish within 1 to 2 hours, and within several hours, he would be pain free. Previously, pain relief would take several days to weeks. He continued to use icatibant on-demand, typically requiring treatment every 1 to 2 months for only the more severe attacks.

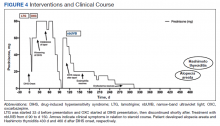

After an increasing frequency of abdominal pain attacks, prophylactic medication was recommended. Therefore, subcutaneous lanadelumab 300 mg every 2 weeks was initiated for long-term prophylaxis. The patient went from requiring on-demand treatment 2 to 3 times per month to once in 6 months after starting lanadelumab. In addition, he tolerated the medication well without any AEs.

Discussion

According to the international WAO/EAACI 2021 guidelines, HAE treatment goals are “to achieve complete control of the disease and to normalize patients’ lives.”8 On-demand treatment options include C1 esterase inhibitor, icatibant, or ecallantide (a kallikrein inhibitor).8 Long-term prophylaxis in HAE should be considered, accounting for disease activity, burden, control, and patient preference. Five medications have been used for long-term prophylaxis: antifibrinolytic agents (not recommended), attenuated androgens (considered second-line), C1 esterase inhibitor, berotralstat, and lanadelumab.8

Antifibrinolytics are no longer recommended for long-term prophylactic treatment as their efficacy is poor and was not considered for our patient. Attenuated androgens, such as danazol, have a history of prophylactic use in patients with HAE due to their good efficacy but are suboptimal due to their significant AE profile and many drug-drug interactions.8 In addition, androgens have many contraindications, including hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, which were both present in our patient. Consequently, danazol was not an advised treatment for our patient. C1 esterase inhibitor is often used to prevent HAE attacks and can be given intravenously or subcutaneously, typically administered biweekly. A potential AE of C1 esterase inhibitor is thrombosis.Therefore, C1 esterase inhibitor was not a preferred choice in our older patient with a history of hypercoagulability. Berotralstat, a plasma kallikrein inhibitor, is an oral treatment option that also has shown efficacy in long-term prophylaxis. The most common AEs of berotralstat tend to be gastrointestinal symptoms, and the medication requires dose adjustment for patients with hepatic impairment.8 Berotralstat was not considered because it was not an approved treatment option at the time of this patient’s treatment. Lanadelumab is a human monoclonal antibody against plasma kallikrein, which decreases bradykinin production in patients with HAE, thus preventing angioedema attacks.5 Data regarding the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE are limited, but because HAE with normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels involves the production of bradykinin via kallikrein, lanadelumab should still be effective.1 Lanadelumab was chosen for our patient because of its minimal AEs and is not known to increase the risk of thrombosis.

Lanadelumab is a novel medication, recently approved in 2018 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type I and type 2 HAE in patients aged ≥ 12 years.7 The phase 3 Hereditary Angioedema Long-term Prophylaxis (HELP) study concluded that treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly decreased the frequency of angioedema attacks compared with placebo.5 However, 113 (90.4%) of patients in the phase III HELP study had type I HAE.5 Of the 125 patients that completed this randomized, double-blind study, only 12 had type II HAE.5 In addition, this study only included 5 patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 Also, no patients aged ≥ 65 years were part of the treatment arms that included a lanadelumab dose of 300 mg.5 In a case series of 12 patients in Canada, treatment with lanadelumab decreased angioedema attacks by 72%.9 However, the series only included 1 patient with type II HAE who was aged 36 years.9 Therefore, our case demonstrates the efficacy of lanadelumab in a patient aged ≥ 65 years with type II HAE.

Conclusions

HAE is a rare and potentially fatal disease characterized by recurrent, unpredictable attacks of edema throughout the body. The disease burden adversely affects a patient’s quality of life. Therefore, long-term prophylaxis is critical to managing patients with HAE. Lanadelumab has been proven as an effective long-term prophylactic treatment option for HAE attacks. This case supports the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.

Acknowledgments

The patient was initially written up based on his delayed diagnosis as a case report.3 An earlier version of this article was presented by Samuel Weiss, MD, and Derek Smith, MD, as a poster at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology virtual conference February 26 to March 1, 2021.

1. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1136-1148. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1808012

2. Bernstein JA. Severity of hereditary angioedema, prevalence, and diagnostic considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(14)(suppl):S292-S298.

3. Berger J, Carroll MP Jr, Champoux E, Coop CA. Extremely delayed diagnosis of type II hereditary angioedema: case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e765-e767. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy031

4. Fouche AS, Saunders EF, Craig T. Depression and anxiety in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(4):371-375. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.05.028

5. Banerji A, Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, et al; HELP Investigators. Effect of lanadelumab compared with placebo on prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2108-2121. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16773

6. Busse PJ, Farkas H, Banerji A, et al. Lanadelumab for the prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: a review of preclinical and phase I studies. BioDrugs. 2019;33(1):33-43. doi:10.1007/s40259-018-0325-y

7. Riedl MA, Maurer M, Bernstein JA, et al. Lanadelumab demonstrates rapid and sustained prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks. Allergy. 2020;75(11):2879-2887. doi:10.1111/all.14416

8. Maurer M, Magerl M, Betschel S, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema—the 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77(7):1961-1990. doi:10.1111/all.15214

9. Iaboni A, Kanani A, Lacuesta G, Song C, Kan M, Betschel SD. Impact of lanadelumab in hereditary angioedema: a case series of 12 patients in Canada. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):78. Published 2021 Jul 23. doi:10.1186/s13223-021-00579-6

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disorder affecting about 1 in 67,000 individuals and may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 HAE is characterized by recurring episodes of subcutaneous and/or submucosal edema without urticaria due to an excess of bradykinin.2,3 Autosomal dominant inheritance is present in 75% of patients with HAE and is classified into 2 main types.2 Type I HAE is caused by deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor, accounting for 85% of cases.2 Type II HAE is marked by normal to elevated levels of C1 esterase inhibitor but with reduced activity.2

Cutaneous and abdominal angioedema attacks are the most common presentation.1 However, any location may be affected, including the face, oropharynx, and larynx.1 Only 0.9% of all HAE attacks cause laryngeal edema, but 50% of HAE patients have experienced a laryngeal attack, which may be lethal.1 An angioedema attack can range in severity, depending on the location and degree of edema.3 In addition, patients with HAE often are diagnosed with anxiety and depression secondary to their poor quality of life.4 Thus, long-term prophylaxis of attacks is crucial to reduce the physical and psychological implications.

Previously, HAE was treated with antifibrinolytic agents and attenuated androgens for short- and long-term prophylaxis.1 These treatment modalities are now considered second-line since the development of novel medications with improved efficacy and limited adverse effects (AEs).1 For long-term prophylaxis, subcutaneous and IV C1 esterase inhibitor has been proven effective in both types I and II HAE.1 Another option, lanadelumab, a subcutaneously delivered monoclonal antibody inhibitor of plasma kallikrein, has been proven to decrease the frequency of HAE attacks without significant AEs.5 Lanadelumab works by binding to the active site of plasma kallikrein, which reduces its activity and slows the production of bradykinin.6 This results in decreasing vascular permeability and swelling episodes in patients with HAE.7 Data, however, are limited, specifically regarding patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 This article reports on an older male with type II HAE successfully treated with lanadelumab.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old male patient with hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and aortic aneurysm had recurrent, frequent episodes of severe abdominal pain with a remote history of extremity and scrotal swelling since adolescence. He was misdiagnosed for years and was eventually determined to have HAE at age 75 years after his niece was diagnosed, prompting him to be reevaluated for his frequent bouts of abdominal pain. His laboratory findings were consistent with HAE type II with low C4 (7.8 mg/dL), normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels (24 mg/dL), and low levels of C1 esterase inhibitor activity (28% of normal).

Initially, he described having weekly attacks of abdominal pain that could last 1 to several days. At worst, these attacks would last up to a month, causing a decrease in appetite and weight loss. At age 77 years, he began an on-demand treatment, icatibant, a bradykinin receptor blocker. After initiating icatibant during an acute attack, the pain would diminish within 1 to 2 hours, and within several hours, he would be pain free. Previously, pain relief would take several days to weeks. He continued to use icatibant on-demand, typically requiring treatment every 1 to 2 months for only the more severe attacks.

After an increasing frequency of abdominal pain attacks, prophylactic medication was recommended. Therefore, subcutaneous lanadelumab 300 mg every 2 weeks was initiated for long-term prophylaxis. The patient went from requiring on-demand treatment 2 to 3 times per month to once in 6 months after starting lanadelumab. In addition, he tolerated the medication well without any AEs.

Discussion

According to the international WAO/EAACI 2021 guidelines, HAE treatment goals are “to achieve complete control of the disease and to normalize patients’ lives.”8 On-demand treatment options include C1 esterase inhibitor, icatibant, or ecallantide (a kallikrein inhibitor).8 Long-term prophylaxis in HAE should be considered, accounting for disease activity, burden, control, and patient preference. Five medications have been used for long-term prophylaxis: antifibrinolytic agents (not recommended), attenuated androgens (considered second-line), C1 esterase inhibitor, berotralstat, and lanadelumab.8

Antifibrinolytics are no longer recommended for long-term prophylactic treatment as their efficacy is poor and was not considered for our patient. Attenuated androgens, such as danazol, have a history of prophylactic use in patients with HAE due to their good efficacy but are suboptimal due to their significant AE profile and many drug-drug interactions.8 In addition, androgens have many contraindications, including hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, which were both present in our patient. Consequently, danazol was not an advised treatment for our patient. C1 esterase inhibitor is often used to prevent HAE attacks and can be given intravenously or subcutaneously, typically administered biweekly. A potential AE of C1 esterase inhibitor is thrombosis.Therefore, C1 esterase inhibitor was not a preferred choice in our older patient with a history of hypercoagulability. Berotralstat, a plasma kallikrein inhibitor, is an oral treatment option that also has shown efficacy in long-term prophylaxis. The most common AEs of berotralstat tend to be gastrointestinal symptoms, and the medication requires dose adjustment for patients with hepatic impairment.8 Berotralstat was not considered because it was not an approved treatment option at the time of this patient’s treatment. Lanadelumab is a human monoclonal antibody against plasma kallikrein, which decreases bradykinin production in patients with HAE, thus preventing angioedema attacks.5 Data regarding the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE are limited, but because HAE with normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels involves the production of bradykinin via kallikrein, lanadelumab should still be effective.1 Lanadelumab was chosen for our patient because of its minimal AEs and is not known to increase the risk of thrombosis.

Lanadelumab is a novel medication, recently approved in 2018 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type I and type 2 HAE in patients aged ≥ 12 years.7 The phase 3 Hereditary Angioedema Long-term Prophylaxis (HELP) study concluded that treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly decreased the frequency of angioedema attacks compared with placebo.5 However, 113 (90.4%) of patients in the phase III HELP study had type I HAE.5 Of the 125 patients that completed this randomized, double-blind study, only 12 had type II HAE.5 In addition, this study only included 5 patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 Also, no patients aged ≥ 65 years were part of the treatment arms that included a lanadelumab dose of 300 mg.5 In a case series of 12 patients in Canada, treatment with lanadelumab decreased angioedema attacks by 72%.9 However, the series only included 1 patient with type II HAE who was aged 36 years.9 Therefore, our case demonstrates the efficacy of lanadelumab in a patient aged ≥ 65 years with type II HAE.

Conclusions

HAE is a rare and potentially fatal disease characterized by recurrent, unpredictable attacks of edema throughout the body. The disease burden adversely affects a patient’s quality of life. Therefore, long-term prophylaxis is critical to managing patients with HAE. Lanadelumab has been proven as an effective long-term prophylactic treatment option for HAE attacks. This case supports the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.

Acknowledgments

The patient was initially written up based on his delayed diagnosis as a case report.3 An earlier version of this article was presented by Samuel Weiss, MD, and Derek Smith, MD, as a poster at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology virtual conference February 26 to March 1, 2021.

Hereditary angioedema (HAE) is a rare genetic disorder affecting about 1 in 67,000 individuals and may lead to increased morbidity and mortality.1,2 HAE is characterized by recurring episodes of subcutaneous and/or submucosal edema without urticaria due to an excess of bradykinin.2,3 Autosomal dominant inheritance is present in 75% of patients with HAE and is classified into 2 main types.2 Type I HAE is caused by deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor, accounting for 85% of cases.2 Type II HAE is marked by normal to elevated levels of C1 esterase inhibitor but with reduced activity.2

Cutaneous and abdominal angioedema attacks are the most common presentation.1 However, any location may be affected, including the face, oropharynx, and larynx.1 Only 0.9% of all HAE attacks cause laryngeal edema, but 50% of HAE patients have experienced a laryngeal attack, which may be lethal.1 An angioedema attack can range in severity, depending on the location and degree of edema.3 In addition, patients with HAE often are diagnosed with anxiety and depression secondary to their poor quality of life.4 Thus, long-term prophylaxis of attacks is crucial to reduce the physical and psychological implications.

Previously, HAE was treated with antifibrinolytic agents and attenuated androgens for short- and long-term prophylaxis.1 These treatment modalities are now considered second-line since the development of novel medications with improved efficacy and limited adverse effects (AEs).1 For long-term prophylaxis, subcutaneous and IV C1 esterase inhibitor has been proven effective in both types I and II HAE.1 Another option, lanadelumab, a subcutaneously delivered monoclonal antibody inhibitor of plasma kallikrein, has been proven to decrease the frequency of HAE attacks without significant AEs.5 Lanadelumab works by binding to the active site of plasma kallikrein, which reduces its activity and slows the production of bradykinin.6 This results in decreasing vascular permeability and swelling episodes in patients with HAE.7 Data, however, are limited, specifically regarding patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 This article reports on an older male with type II HAE successfully treated with lanadelumab.

Case Presentation

An 81-year-old male patient with hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and aortic aneurysm had recurrent, frequent episodes of severe abdominal pain with a remote history of extremity and scrotal swelling since adolescence. He was misdiagnosed for years and was eventually determined to have HAE at age 75 years after his niece was diagnosed, prompting him to be reevaluated for his frequent bouts of abdominal pain. His laboratory findings were consistent with HAE type II with low C4 (7.8 mg/dL), normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels (24 mg/dL), and low levels of C1 esterase inhibitor activity (28% of normal).

Initially, he described having weekly attacks of abdominal pain that could last 1 to several days. At worst, these attacks would last up to a month, causing a decrease in appetite and weight loss. At age 77 years, he began an on-demand treatment, icatibant, a bradykinin receptor blocker. After initiating icatibant during an acute attack, the pain would diminish within 1 to 2 hours, and within several hours, he would be pain free. Previously, pain relief would take several days to weeks. He continued to use icatibant on-demand, typically requiring treatment every 1 to 2 months for only the more severe attacks.

After an increasing frequency of abdominal pain attacks, prophylactic medication was recommended. Therefore, subcutaneous lanadelumab 300 mg every 2 weeks was initiated for long-term prophylaxis. The patient went from requiring on-demand treatment 2 to 3 times per month to once in 6 months after starting lanadelumab. In addition, he tolerated the medication well without any AEs.

Discussion

According to the international WAO/EAACI 2021 guidelines, HAE treatment goals are “to achieve complete control of the disease and to normalize patients’ lives.”8 On-demand treatment options include C1 esterase inhibitor, icatibant, or ecallantide (a kallikrein inhibitor).8 Long-term prophylaxis in HAE should be considered, accounting for disease activity, burden, control, and patient preference. Five medications have been used for long-term prophylaxis: antifibrinolytic agents (not recommended), attenuated androgens (considered second-line), C1 esterase inhibitor, berotralstat, and lanadelumab.8

Antifibrinolytics are no longer recommended for long-term prophylactic treatment as their efficacy is poor and was not considered for our patient. Attenuated androgens, such as danazol, have a history of prophylactic use in patients with HAE due to their good efficacy but are suboptimal due to their significant AE profile and many drug-drug interactions.8 In addition, androgens have many contraindications, including hypertension and hypertriglyceridemia, which were both present in our patient. Consequently, danazol was not an advised treatment for our patient. C1 esterase inhibitor is often used to prevent HAE attacks and can be given intravenously or subcutaneously, typically administered biweekly. A potential AE of C1 esterase inhibitor is thrombosis.Therefore, C1 esterase inhibitor was not a preferred choice in our older patient with a history of hypercoagulability. Berotralstat, a plasma kallikrein inhibitor, is an oral treatment option that also has shown efficacy in long-term prophylaxis. The most common AEs of berotralstat tend to be gastrointestinal symptoms, and the medication requires dose adjustment for patients with hepatic impairment.8 Berotralstat was not considered because it was not an approved treatment option at the time of this patient’s treatment. Lanadelumab is a human monoclonal antibody against plasma kallikrein, which decreases bradykinin production in patients with HAE, thus preventing angioedema attacks.5 Data regarding the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE are limited, but because HAE with normal C1 esterase inhibitor levels involves the production of bradykinin via kallikrein, lanadelumab should still be effective.1 Lanadelumab was chosen for our patient because of its minimal AEs and is not known to increase the risk of thrombosis.

Lanadelumab is a novel medication, recently approved in 2018 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of type I and type 2 HAE in patients aged ≥ 12 years.7 The phase 3 Hereditary Angioedema Long-term Prophylaxis (HELP) study concluded that treatment with subcutaneous lanadelumab for 26 weeks significantly decreased the frequency of angioedema attacks compared with placebo.5 However, 113 (90.4%) of patients in the phase III HELP study had type I HAE.5 Of the 125 patients that completed this randomized, double-blind study, only 12 had type II HAE.5 In addition, this study only included 5 patients aged ≥ 65 years.5 Also, no patients aged ≥ 65 years were part of the treatment arms that included a lanadelumab dose of 300 mg.5 In a case series of 12 patients in Canada, treatment with lanadelumab decreased angioedema attacks by 72%.9 However, the series only included 1 patient with type II HAE who was aged 36 years.9 Therefore, our case demonstrates the efficacy of lanadelumab in a patient aged ≥ 65 years with type II HAE.

Conclusions

HAE is a rare and potentially fatal disease characterized by recurrent, unpredictable attacks of edema throughout the body. The disease burden adversely affects a patient’s quality of life. Therefore, long-term prophylaxis is critical to managing patients with HAE. Lanadelumab has been proven as an effective long-term prophylactic treatment option for HAE attacks. This case supports the use of lanadelumab in patients with type II HAE and patients aged ≥ 65 years.

Acknowledgments

The patient was initially written up based on his delayed diagnosis as a case report.3 An earlier version of this article was presented by Samuel Weiss, MD, and Derek Smith, MD, as a poster at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology virtual conference February 26 to March 1, 2021.

1. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1136-1148. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1808012

2. Bernstein JA. Severity of hereditary angioedema, prevalence, and diagnostic considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(14)(suppl):S292-S298.

3. Berger J, Carroll MP Jr, Champoux E, Coop CA. Extremely delayed diagnosis of type II hereditary angioedema: case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e765-e767. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy031

4. Fouche AS, Saunders EF, Craig T. Depression and anxiety in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(4):371-375. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.05.028

5. Banerji A, Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, et al; HELP Investigators. Effect of lanadelumab compared with placebo on prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2108-2121. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16773

6. Busse PJ, Farkas H, Banerji A, et al. Lanadelumab for the prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: a review of preclinical and phase I studies. BioDrugs. 2019;33(1):33-43. doi:10.1007/s40259-018-0325-y

7. Riedl MA, Maurer M, Bernstein JA, et al. Lanadelumab demonstrates rapid and sustained prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks. Allergy. 2020;75(11):2879-2887. doi:10.1111/all.14416

8. Maurer M, Magerl M, Betschel S, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema—the 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77(7):1961-1990. doi:10.1111/all.15214

9. Iaboni A, Kanani A, Lacuesta G, Song C, Kan M, Betschel SD. Impact of lanadelumab in hereditary angioedema: a case series of 12 patients in Canada. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):78. Published 2021 Jul 23. doi:10.1186/s13223-021-00579-6

1. Busse PJ, Christiansen SC. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1136-1148. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1808012

2. Bernstein JA. Severity of hereditary angioedema, prevalence, and diagnostic considerations. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(14)(suppl):S292-S298.

3. Berger J, Carroll MP Jr, Champoux E, Coop CA. Extremely delayed diagnosis of type II hereditary angioedema: case report and review of the literature. Mil Med. 2018;183(11-12):e765-e767. doi:10.1093/milmed/usy031

4. Fouche AS, Saunders EF, Craig T. Depression and anxiety in patients with hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(4):371-375. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.05.028

5. Banerji A, Riedl MA, Bernstein JA, et al; HELP Investigators. Effect of lanadelumab compared with placebo on prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2108-2121. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16773

6. Busse PJ, Farkas H, Banerji A, et al. Lanadelumab for the prophylactic treatment of hereditary angioedema with C1 inhibitor deficiency: a review of preclinical and phase I studies. BioDrugs. 2019;33(1):33-43. doi:10.1007/s40259-018-0325-y

7. Riedl MA, Maurer M, Bernstein JA, et al. Lanadelumab demonstrates rapid and sustained prevention of hereditary angioedema attacks. Allergy. 2020;75(11):2879-2887. doi:10.1111/all.14416

8. Maurer M, Magerl M, Betschel S, et al. The international WAO/EAACI guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema—the 2021 revision and update. Allergy. 2022;77(7):1961-1990. doi:10.1111/all.15214

9. Iaboni A, Kanani A, Lacuesta G, Song C, Kan M, Betschel SD. Impact of lanadelumab in hereditary angioedema: a case series of 12 patients in Canada. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(1):78. Published 2021 Jul 23. doi:10.1186/s13223-021-00579-6

56-year-old man • increased heart rate • weakness • intense sweating • horseradish consumption • Dx?

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16

Another theory involves clot production and suggests that VVS-induced hypotension is a defense against bleeding by improving clot formation.17

A psychological defense theory maintains that the fainting and memory loss are designed to prevent a painful or overwhelming experience from being remembered. None of these theories, however, explain orthostatic VVS.18

The brain defense theory could explain all forms of VVS. It postulates that hypotension causes decreased cerebral perfusion, which leads to syncope resulting in the body returning to a more orthostatic position with increased cerebral profusion.19

Continue to: The patient

The patient in this case was able to leave the restaurant on his own volition 30 minutes after the event and resume normal activities. Ten days later, an electrocardiogram was performed, with negative results. In this case, the use of a potassium-wasting diuretic exacerbated the risk of a fluid-deprived state, hypokalemia, and hypotension, possibly contributing to the syncope. The patient has since “gotten back on the horseradish” without ill effect.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consumers and health care providers should be aware of the risks associated with consumption of fresh horseradish and should allow it to rest prior to ingestion to allow some evaporation of its active ingredient. An old case report saved the patient from an unnecessary (and costly) emergency department visit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Terry J. Hannan, MBBS, FRACP, FACHI, FACMI for his critical review of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christoph U. Lehmann, MD, Clinical Informatics Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390; [email protected]

1. Rubin HR, Wu AW. The bitter herbs of Seder: more on horseradish horrors. JAMA. 1988;259:1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.13.1943b

2. Seder syncope. The Free Dictionary. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Horseradish+Syncope

3. Sheldon RS, Sheldon AG, Connolly SJ, et al. Age of first faint in patients with vasovagal syncope. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:49-54. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00267.x

4. Wallin BG, Sundlöf G. Sympathetic outflow to muscles during vasovagal syncope. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1982;6:287-291. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(82)90001-7

5. Jardine DL, Melton IC, Crozier IG, et al. Decrease in cardiac output and muscle sympathetic activity during vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1804-H1809. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00640.2001

6. Waxman MB, Asta JA, Cameron DA. Localization of the reflex pathway responsible for the vasodepressor reaction induced by inferior vena caval occlusion and isoproterenol. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:882-889. doi: 10.1139/y92-118

7. Alboni P, Alboni M. Typical vasovagal syncope as a “defense mechanism” for the heart by contrasting sympathetic overactivity. Clin Auton Res. 2017;27:253-261. doi: 10.1007/s10286-017-0446-2

8. Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631-2671. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp298

9. Davies J, MacDonald L, Sivakumar B, et al. Prospective analysis of syncope/pre-syncope in a tertiary paediatric orthopaedic fracture outpatient clinic. ANZ J Surg. 2021;91:668-672. doi: 10.1111/ans.16664

10. Almutairi H, Salam M, Batarfi K, et al. Incidence and severity of adverse events among platelet donors: a three-year retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e23648. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023648

11. Coakley A, Bailey A, Tao J, et al. Video education to improve clinical skills in the prevention of and response to vasovagal syncopal episodes. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:186-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.02.002

12. Thijs RD, Brignole M, Falup-Pecurariu C, et al. Recommendations for tilt table testing and other provocative cardiovascular autonomic tests in conditions that may cause transient loss of consciousness: consensus statement of the European Federation of Autonomic Societies (EFAS) endorsed by the American Autonomic Society (AAS) and the European Academy of Neurology (EAN). Auton Neurosci. 2021;233:102792. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2021.102792

13. Nakagawa S, Hisanaga S, Kondoh H, et al. A case of swallow syncope induced by vagotonic visceral reflex resulting in atrioventricular node suppression. J Electrocardiol. 1987;20:65-69. doi: 10.1016/0022-0736(87)90010-0

14. O’Dwyer C, Bennett K, Langan Y, et al. Amnesia for loss of consciousness is common in vasovagal syncope. Europace. 2011;13:1040-1045. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur069

15. Jorge JG, Raj SR, Teixeira PS, et al. Likelihood of injury due to vasovagal syncope: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2021;23:1092-1099. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab041

16. Bracha HS, Bracha AS, Williams AE, et al. The human fear-circuitry and fear-induced fainting in healthy individuals—the paleolithic-threat hypothesis. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:238-241. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0245-z

17. Diehl RR. Vasovagal syncope and Darwinian fitness. Clin Auton Res. 2005;15:126-129. doi: 10.1007/s10286-005-0244-0

18. Engel CL, Romano J. Studies of syncope; biologic interpretation of vasodepressor syncope. Psychosom Med. 1947;9:288-294. doi: 10.1097/00006842-194709000-00002

19. Blanc JJ, Benditt DG. Vasovagal syncope: hypothesis focusing on its being a clinical feature unique to humans. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:623-629. doi: 10.1111/jce.12945

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16

Another theory involves clot production and suggests that VVS-induced hypotension is a defense against bleeding by improving clot formation.17

A psychological defense theory maintains that the fainting and memory loss are designed to prevent a painful or overwhelming experience from being remembered. None of these theories, however, explain orthostatic VVS.18

The brain defense theory could explain all forms of VVS. It postulates that hypotension causes decreased cerebral perfusion, which leads to syncope resulting in the body returning to a more orthostatic position with increased cerebral profusion.19

Continue to: The patient

The patient in this case was able to leave the restaurant on his own volition 30 minutes after the event and resume normal activities. Ten days later, an electrocardiogram was performed, with negative results. In this case, the use of a potassium-wasting diuretic exacerbated the risk of a fluid-deprived state, hypokalemia, and hypotension, possibly contributing to the syncope. The patient has since “gotten back on the horseradish” without ill effect.

THE TAKEAWAY

Consumers and health care providers should be aware of the risks associated with consumption of fresh horseradish and should allow it to rest prior to ingestion to allow some evaporation of its active ingredient. An old case report saved the patient from an unnecessary (and costly) emergency department visit.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Terry J. Hannan, MBBS, FRACP, FACHI, FACMI for his critical review of the manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christoph U. Lehmann, MD, Clinical Informatics Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX 75390; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 56-year-old physician (CUL) visited a local seafood restaurant, after having fasted since the prior evening. He had a history of hypertension that was well controlled with lisinopril/hydrochlorothiazide.

The physician and his party were seated outside, where the temperature was in the mid-70s. The group ordered oysters on the half shell accompanied by mignonette sauce, cocktail sauce, and horseradish. The physician ate an olive-size amount of horseradish with an oyster. He immediately complained of a sharp burning sensation in his stomach and remarked that the horseradish was significantly stronger than what he was accustomed to. Within 30 seconds, he noted an increased heart rate, weakness, and intense sweating. There was no increase in nasal secretions. Observers noted that he was very pale.

About 5 minutes after eating the horseradish, the physician leaned his head back and briefly lost consciousness. His wife, while supporting his head and checking his pulse, instructed other diners to call for emergency services, at which point the physician regained consciousness and the dispatcher was told that an ambulance was no longer necessary. Within a matter of minutes, all symptoms had abated, except for some mild weakness.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Ten minutes after the event, the physician identified his symptoms as a horseradish-induced vasovagal syncope (VVS), based on a case report published in JAMA in 1988, which his wife found after he asked her to do an Internet search of his symptoms.1

THE DISCUSSION

Horseradish’s active component is isothiocyanate. Horseradish-induced syncope is also called Seder syncope after the Jewish Passover holiday dinner at which observant Jews are required to eat “bitter herbs.”1,2 This type of syncope is thought to occur when horseradish vapors directly irritate the gastric or respiratory tract mucosa.

VVS commonly manifests for the first time at around age 13 years; however, the timing of that first occurrence can vary significantly among individuals (as in this case)

The loss of consciousness may be caused by an emotional trigger (eg, sight of blood, cast removal,8 blood or platelet donations9,10), a painful event (eg, an injection11), an orthostatic trigger12 (eg, prolonged standing), or visceral reflexes such as swallowing.13 In approximately 30% of cases, loss of consciousness is associated with memory loss.14 Loss of consciousness with VVS may be associated with injury in 33% of cases.15

Continue to: The recovery with awareness

The recovery with awareness of time, place, and person may be a feature of VVS, which would differentiate it from seizures and brainstem vascular events. Autonomic prodromal symptoms—including abdominal discomfort, pallor, sweating, and nausea—may precede the loss of consciousness.8

An evolutionary response?

VVS may have developed as a trait through evolution, although modern medicine treats it as a disease. Many potential explanations for VVS as a body defense mechanism have been proposed. Examples include fainting at the sight of blood, which developed during the Old Stone Age—a period with extreme human-to-human violence—or acting like a “possum playing dead” as a tactic designed to confuse an attacker.16