User login

Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis Masquerading as Chronic ITP

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an immune-mediated acquired condition affecting both adults and children.1 Acute ITP is the most common form, which happens in the presence of a precipitant, leading to a drop in platelet counts. However, chronic ITP can occur when all the causes that might precipitate thrombocytopenia have been ruled out, and it is persistent for ≥ 12 months.2 Its presence can mask other diseases that exhibit somewhat similar signs and symptoms. We present a case of a patient presenting with chronic ITP with diffuse rash and was later diagnosed with idiopathic leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

Case Presentation

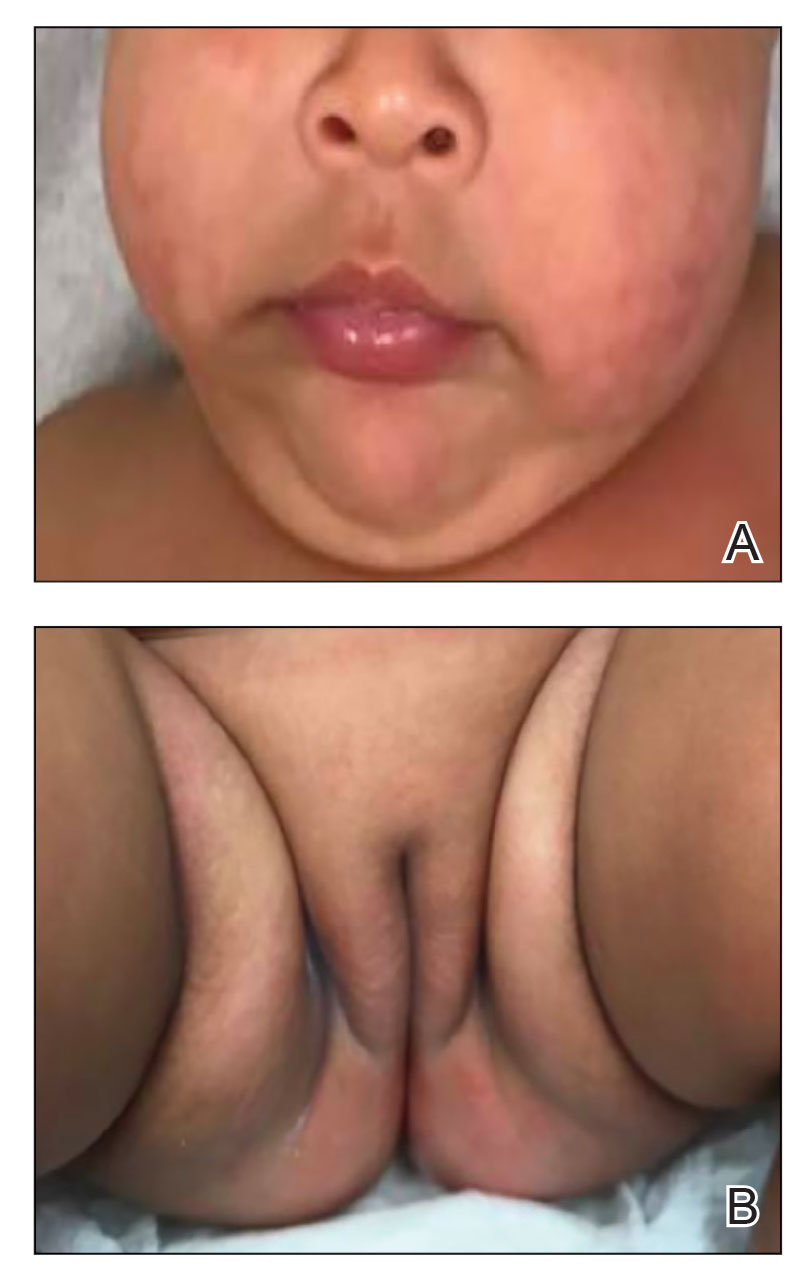

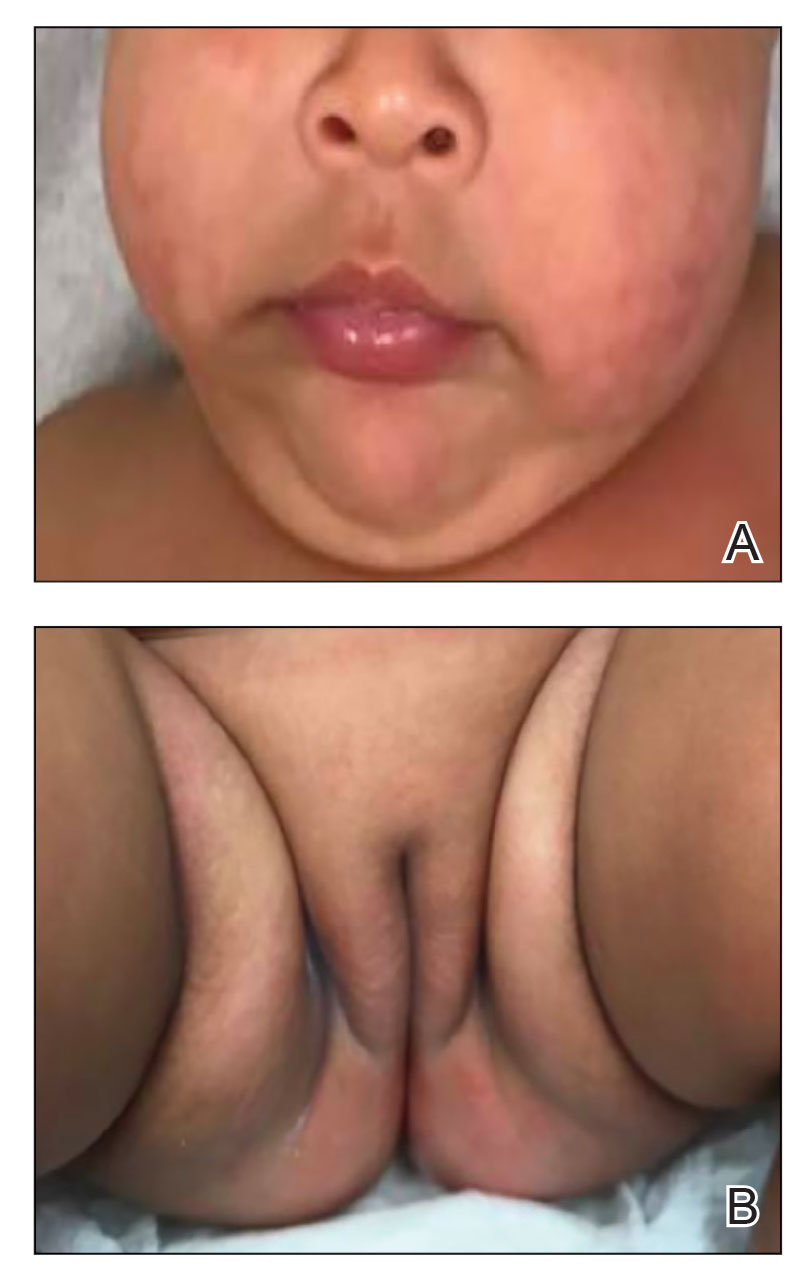

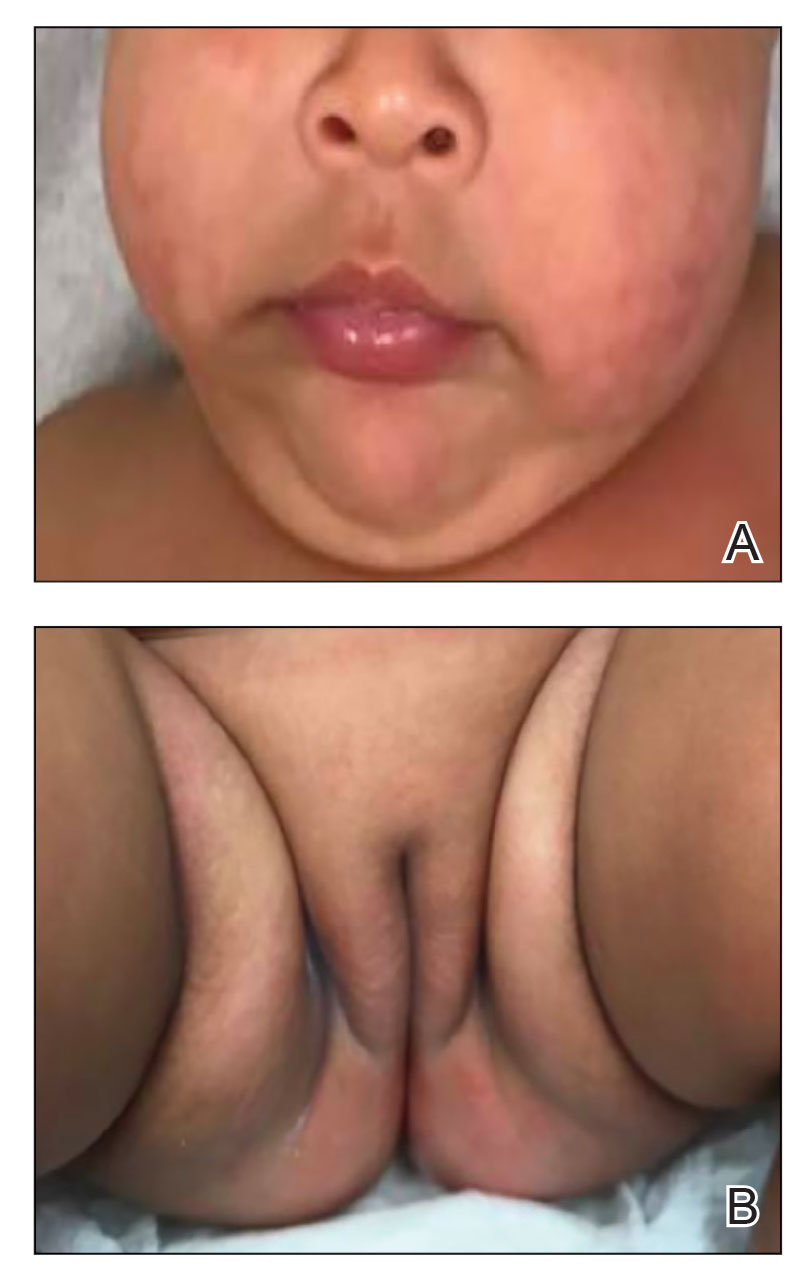

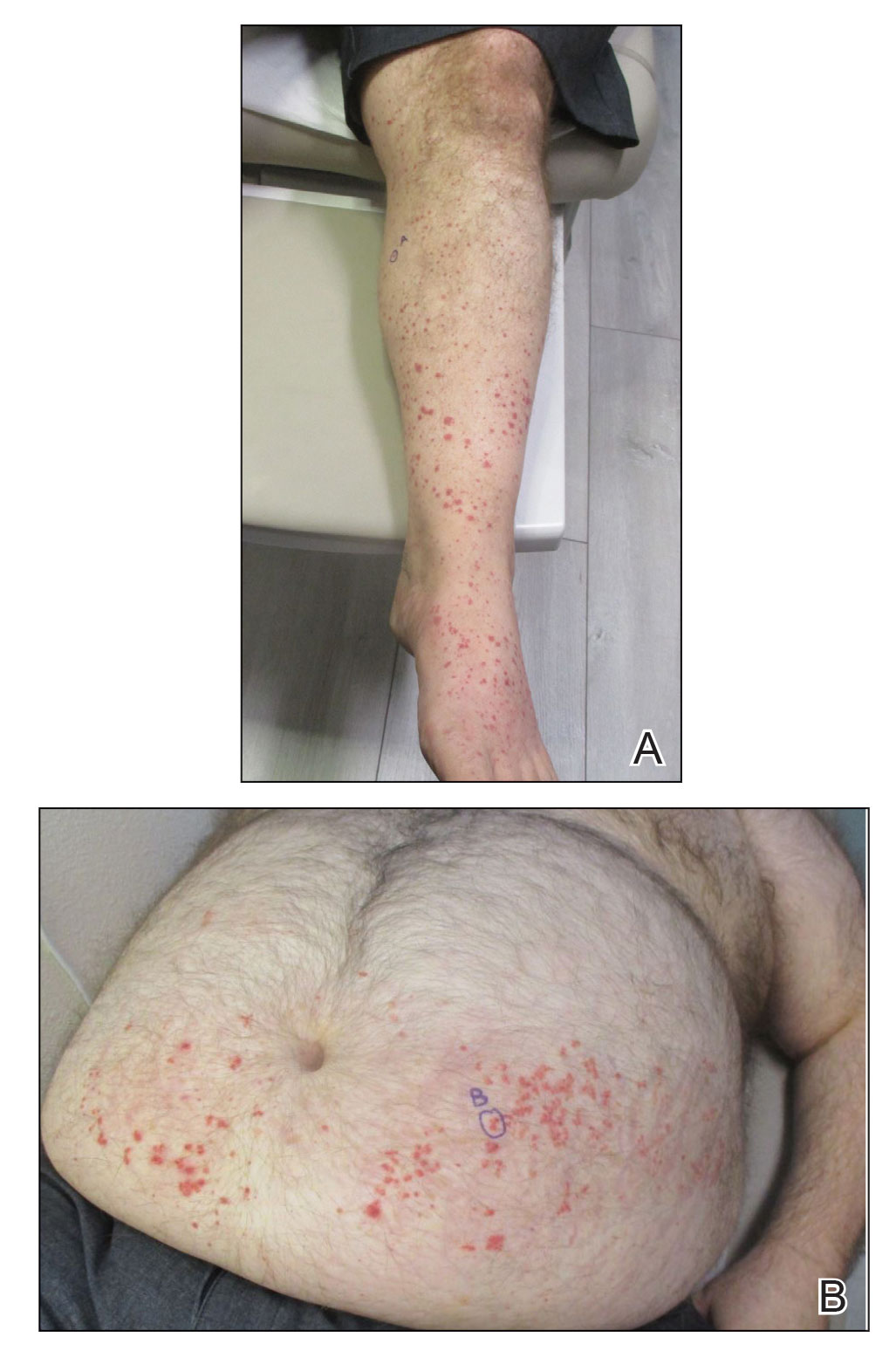

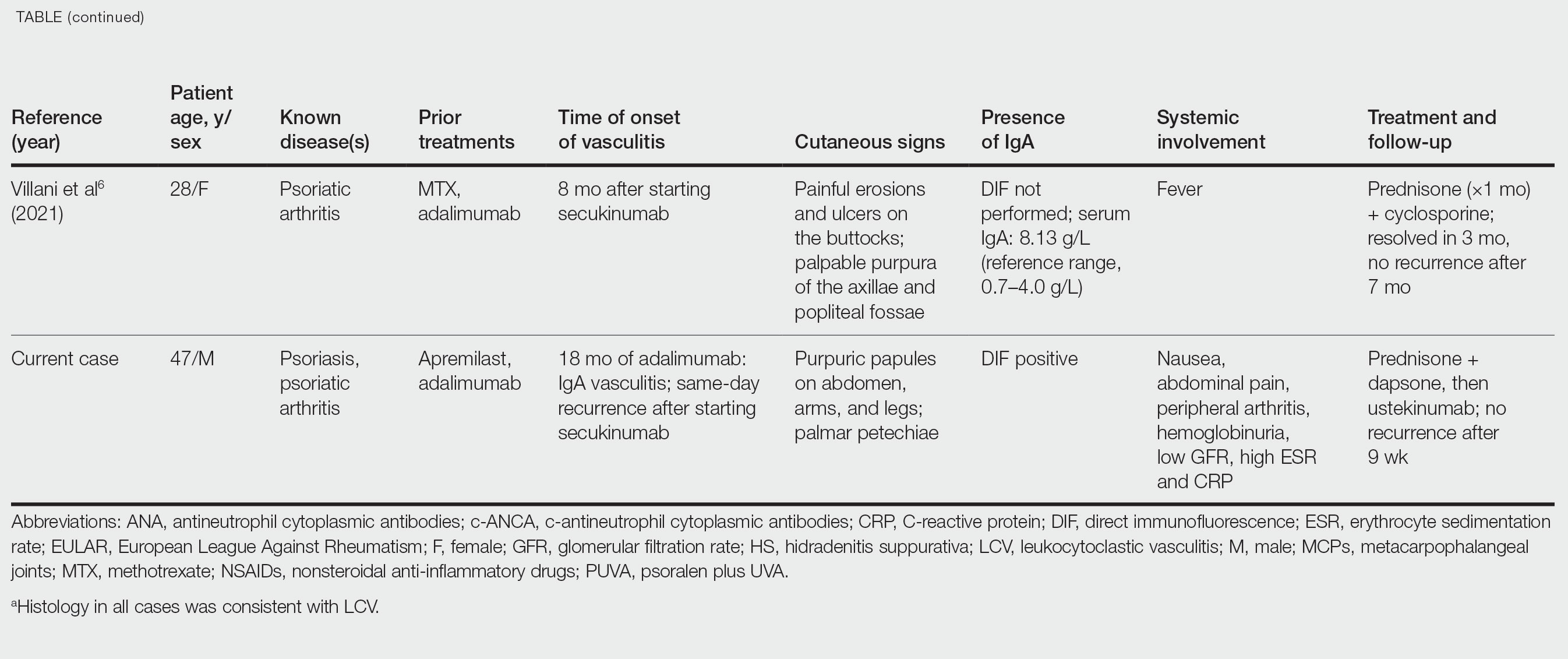

A 79-year-old presented to the hospital with 2-day history of a rash. The rash was purpureal and petechial and located on the trunk and bilateral upper and lower extremities. The rash was associated with itchiness and pain in the wrists, ankles, and small joints of the hands. The patient reported no changes in medication or diet,

The patient mentioned that at the time of diagnosis the platelet count was about 90,000 but had been fluctuating between 50 and 60,000 recently. The patient also reported no history of gum bleeding, nosebleeds, hemoptysis, hematemesis, or any miscarriages. She also had difficulty voiding for 2 to 3 days but no dysuria, frequency, urgency, or incontinence.

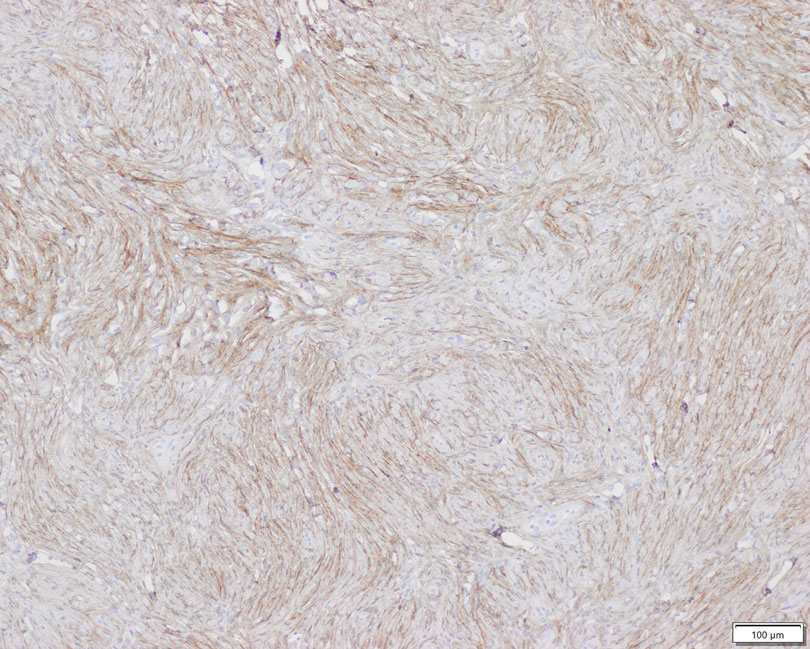

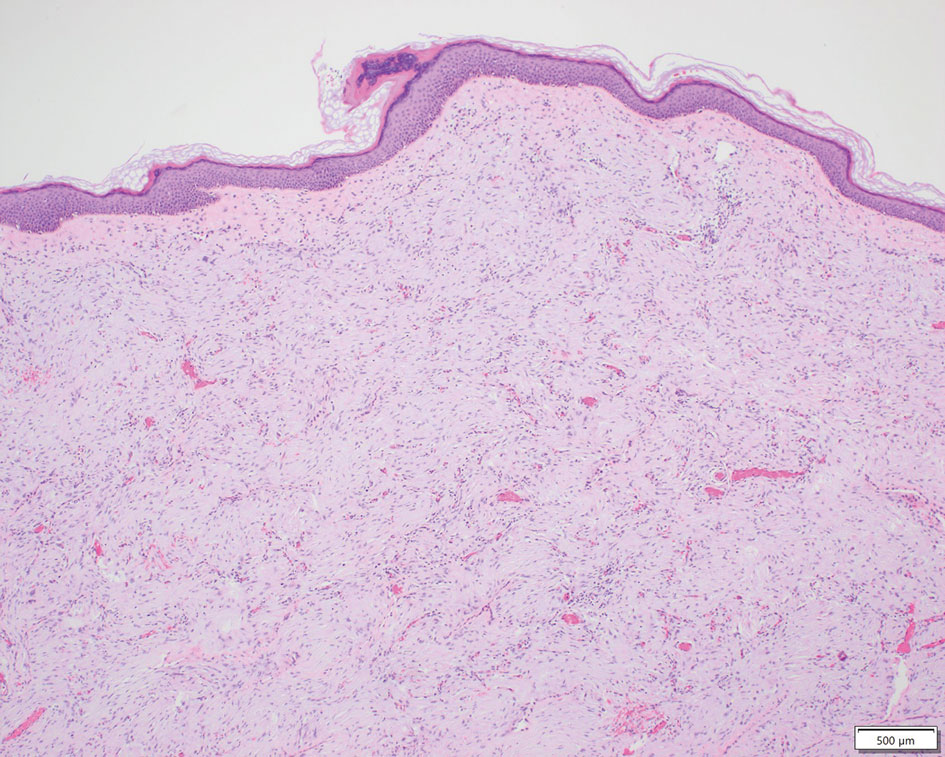

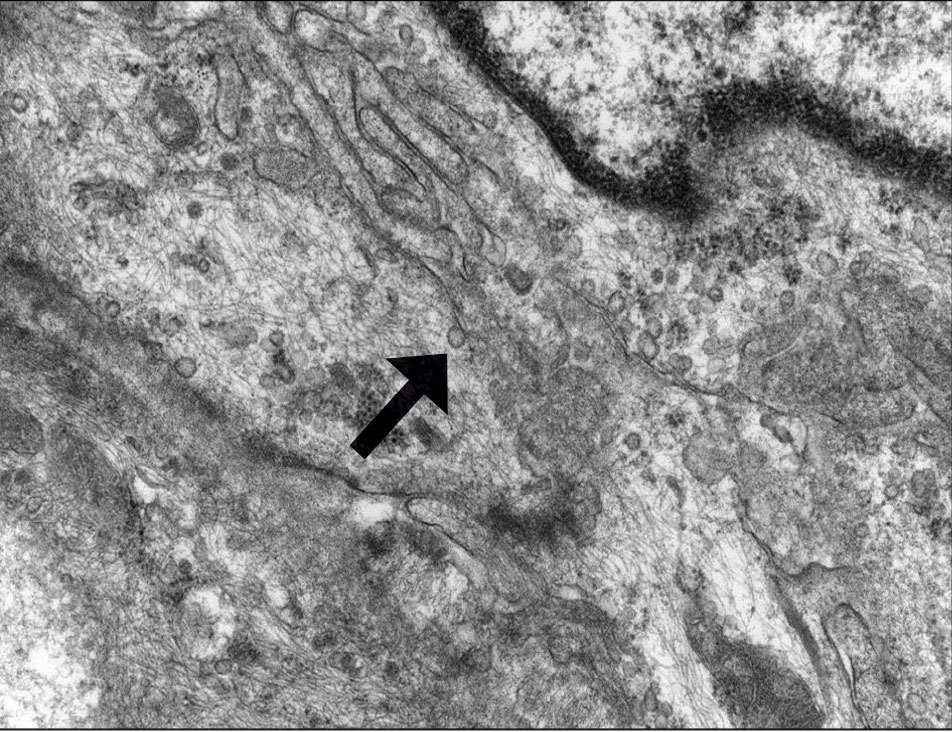

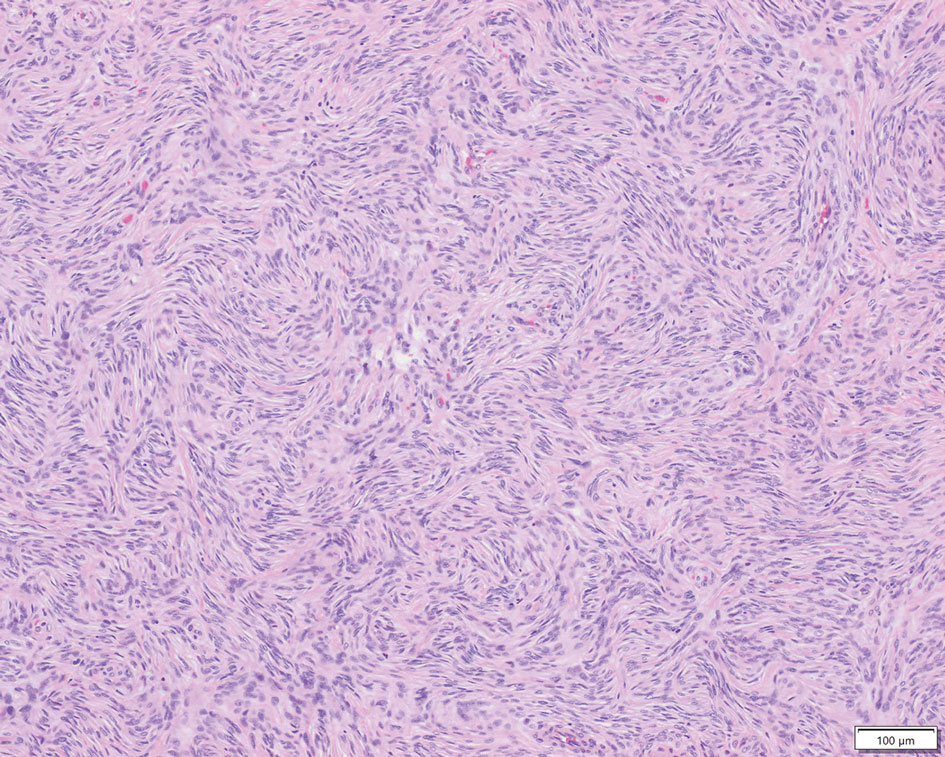

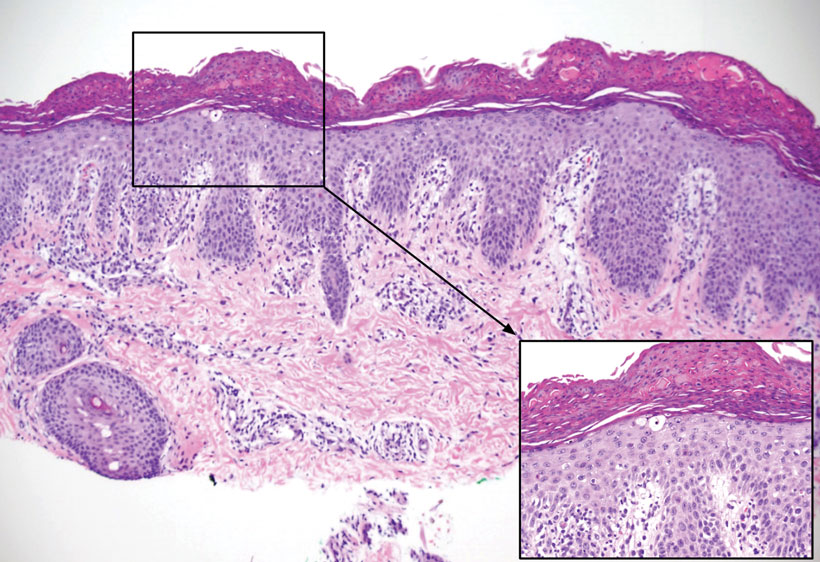

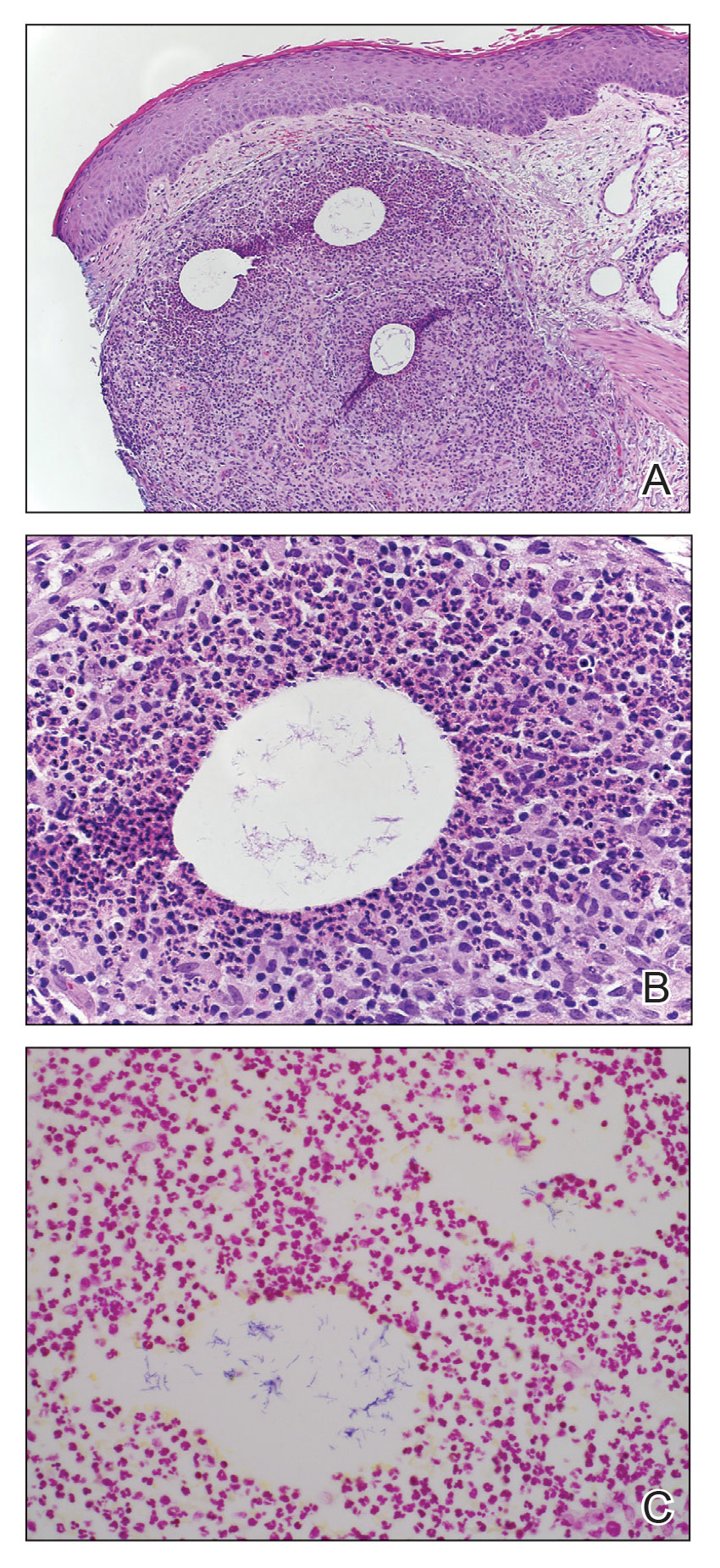

Laboratory results were significant for 57,000/µL platelet count (normal range, 150,000-450,000), elevated d-dimer (6.07), < 6 mg/dL C4 (normal range, 88-201). Hemoglobin level, coagulation panel, hemolytic panel, and fibrinogen level results were unremarkable. The hepatitis panel, Lyme disease, and HIV test were negative. The peripheral blood smear showed moderate thrombocytopenia, mild monocytosis, and borderline normochromic normocytic anemia without schistocytes. The autoimmune panel to evaluate thrombocytopenia showed platelet antibody against glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa, GP Ib/Ix, GP Ia/IIa, suggestive toward a diagnosis of chronic idiopathic ITP. However, the skin biopsy of the rash was indicative of LCV.

An autoimmune panel for vasculitis, including antinuclear antibody and antidouble-stranded DNA, was negative. While in the hospital, the patient completed the course of ciprofloxacin for the UTI, the rash started to fade without any intervention, and the platelet count improved to 69,000/µL. The patient was discharged after 3 days with the recommendation to follow up with her hematologist.

Discussion

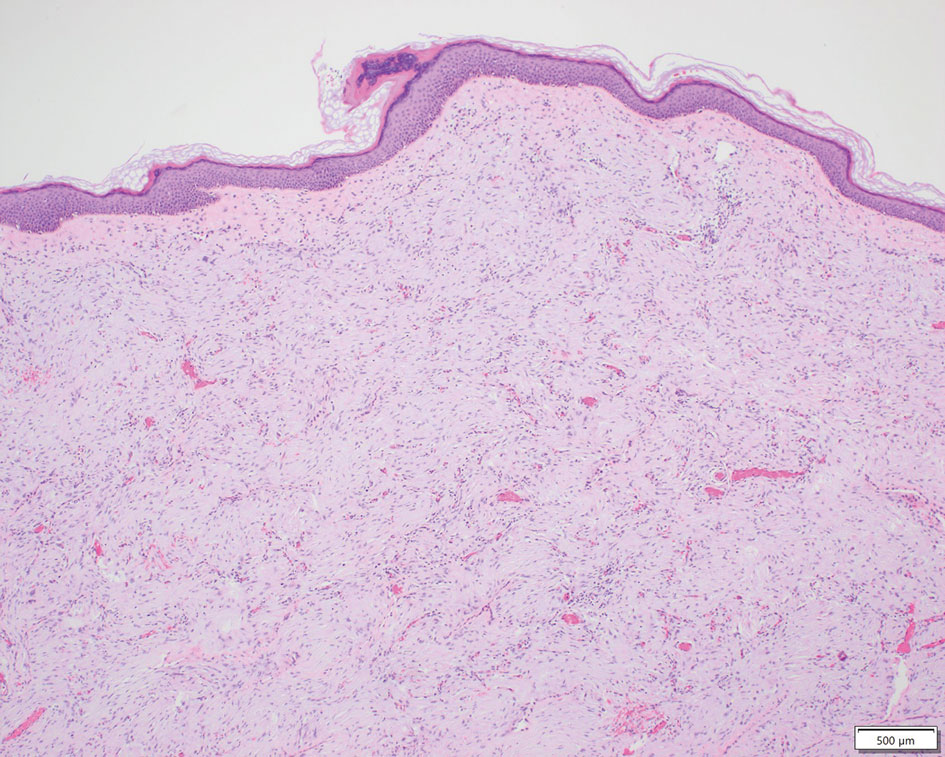

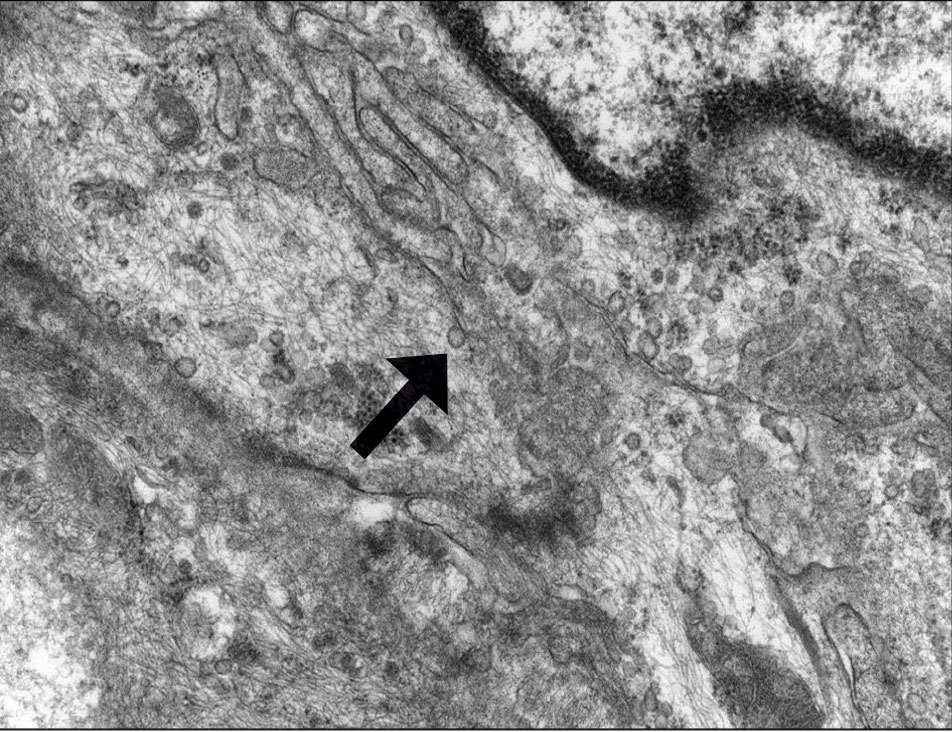

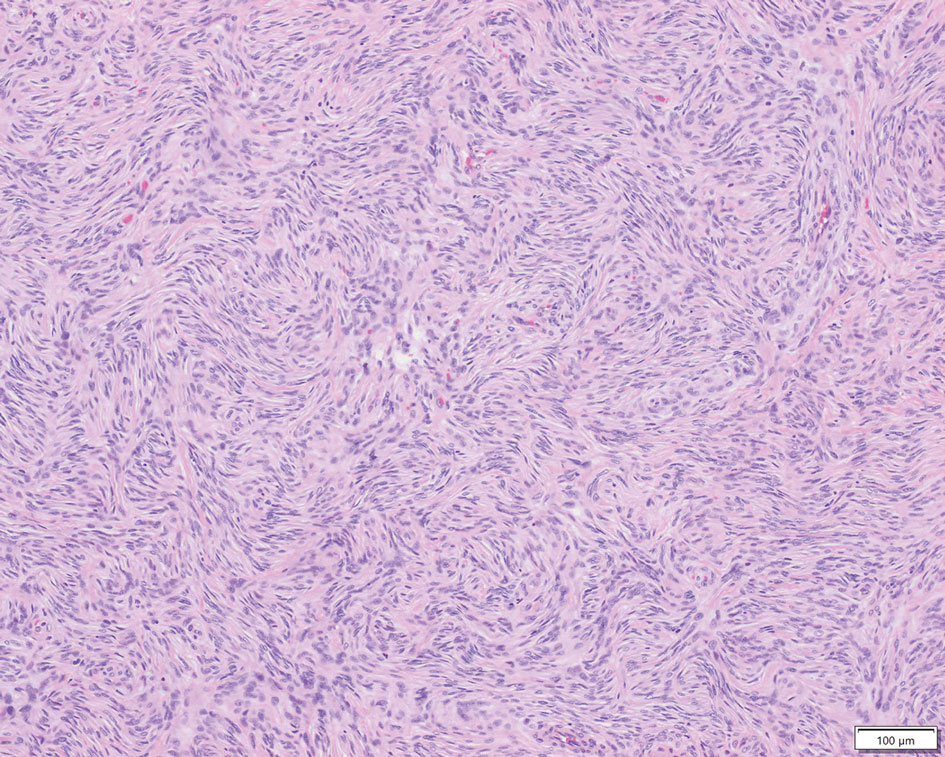

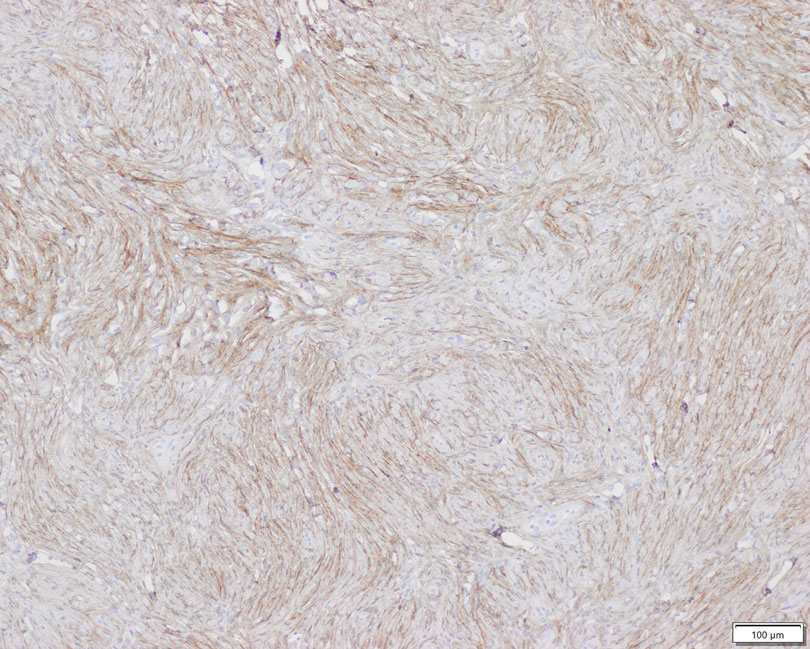

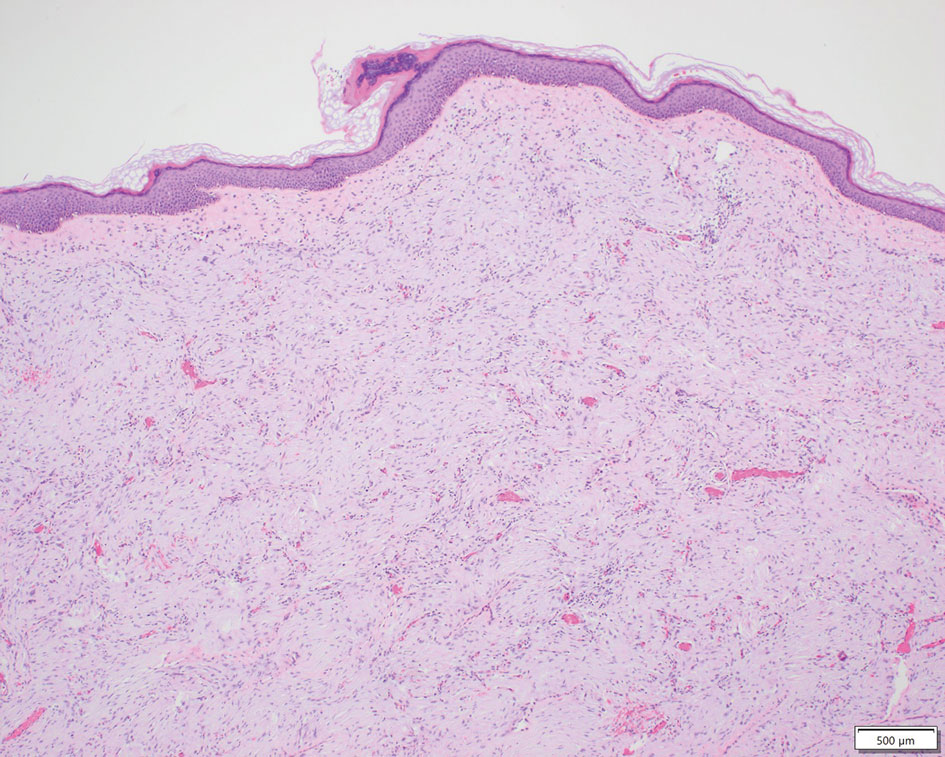

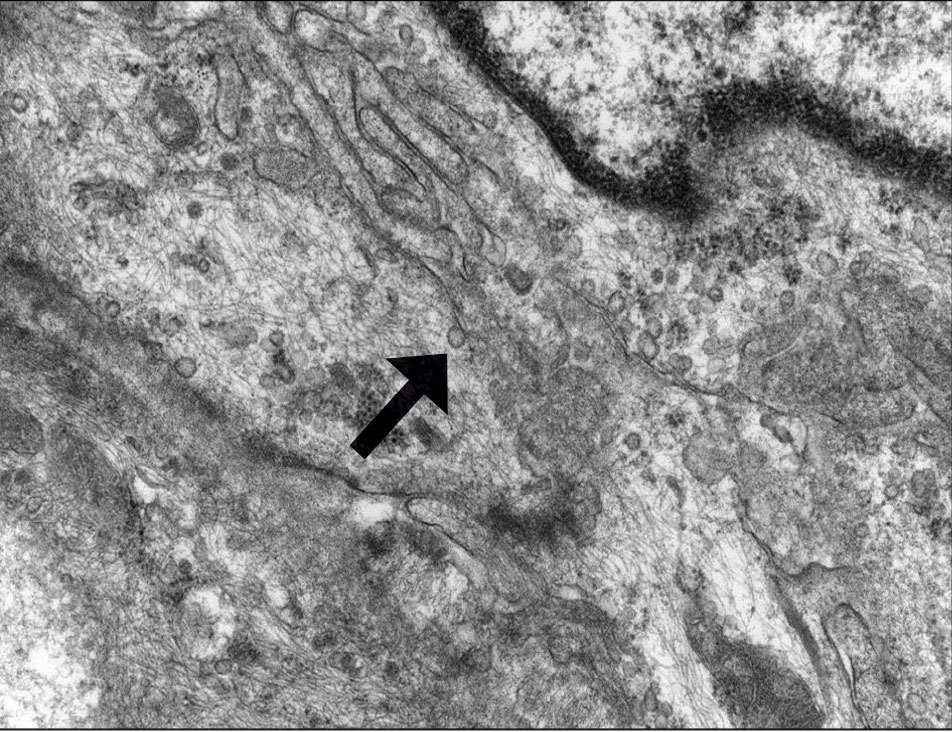

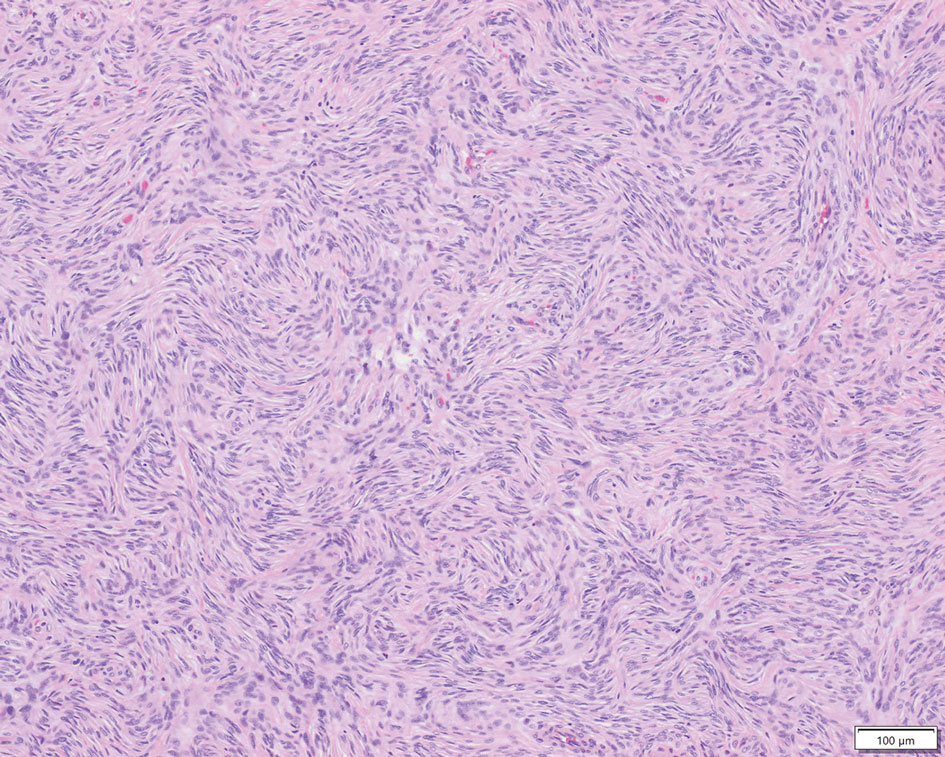

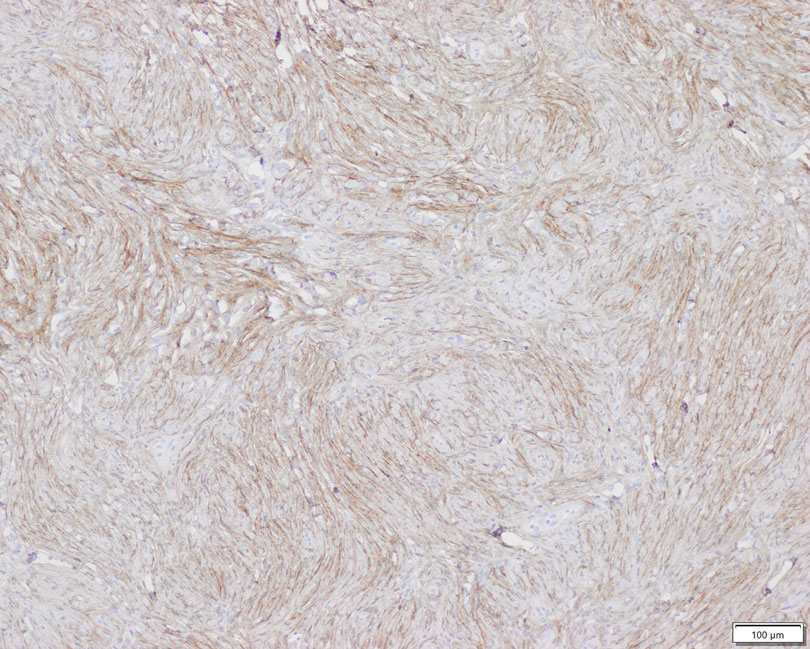

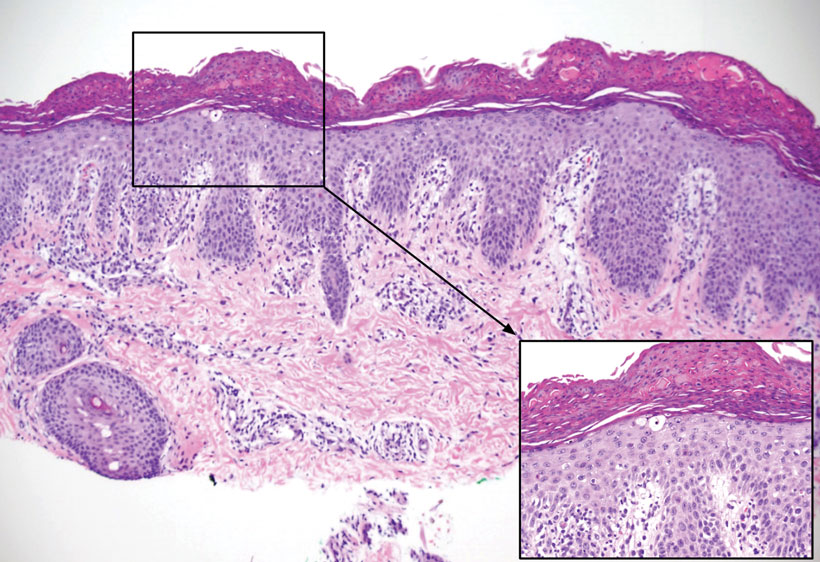

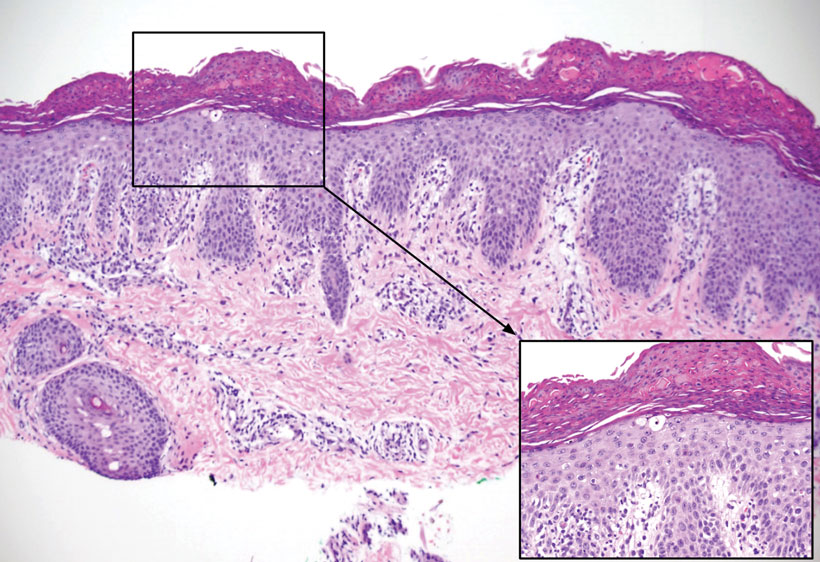

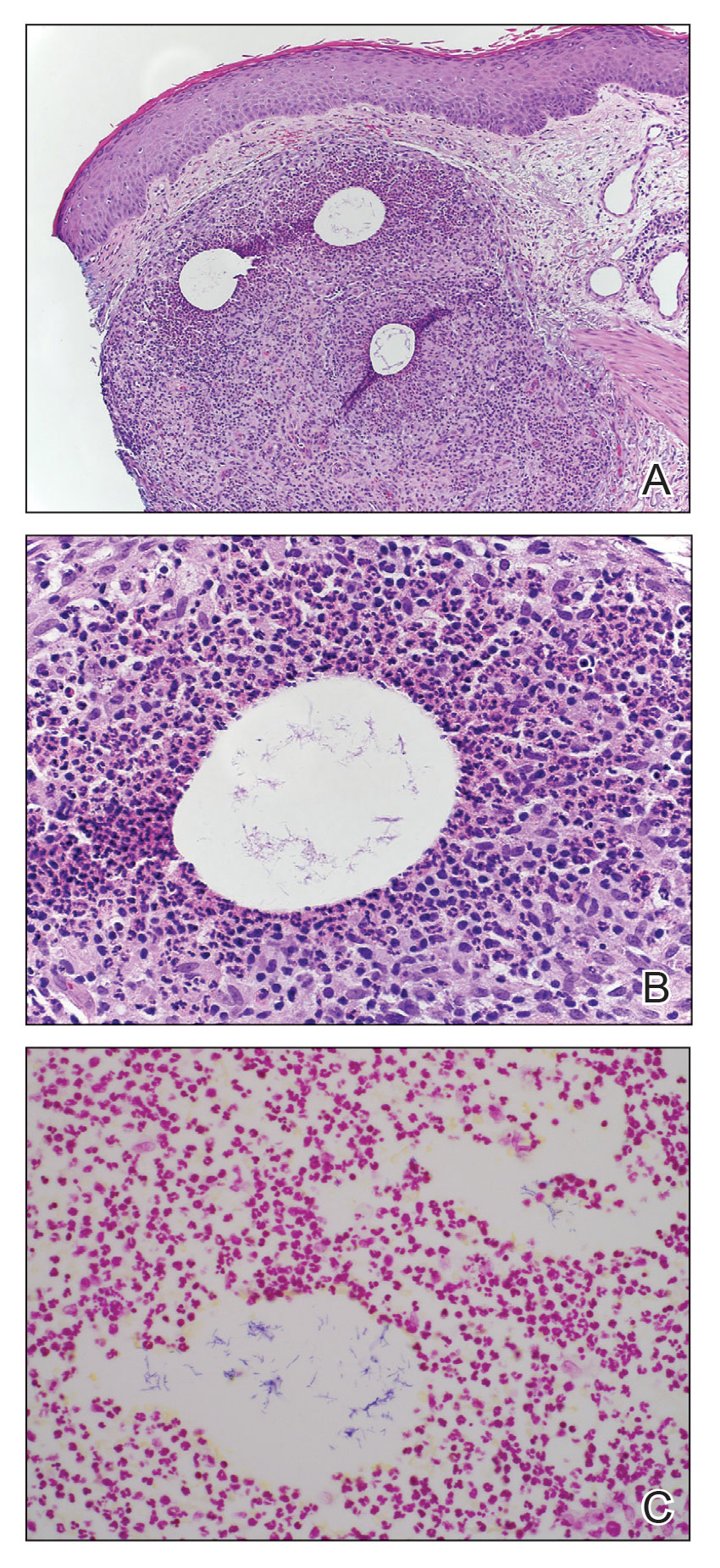

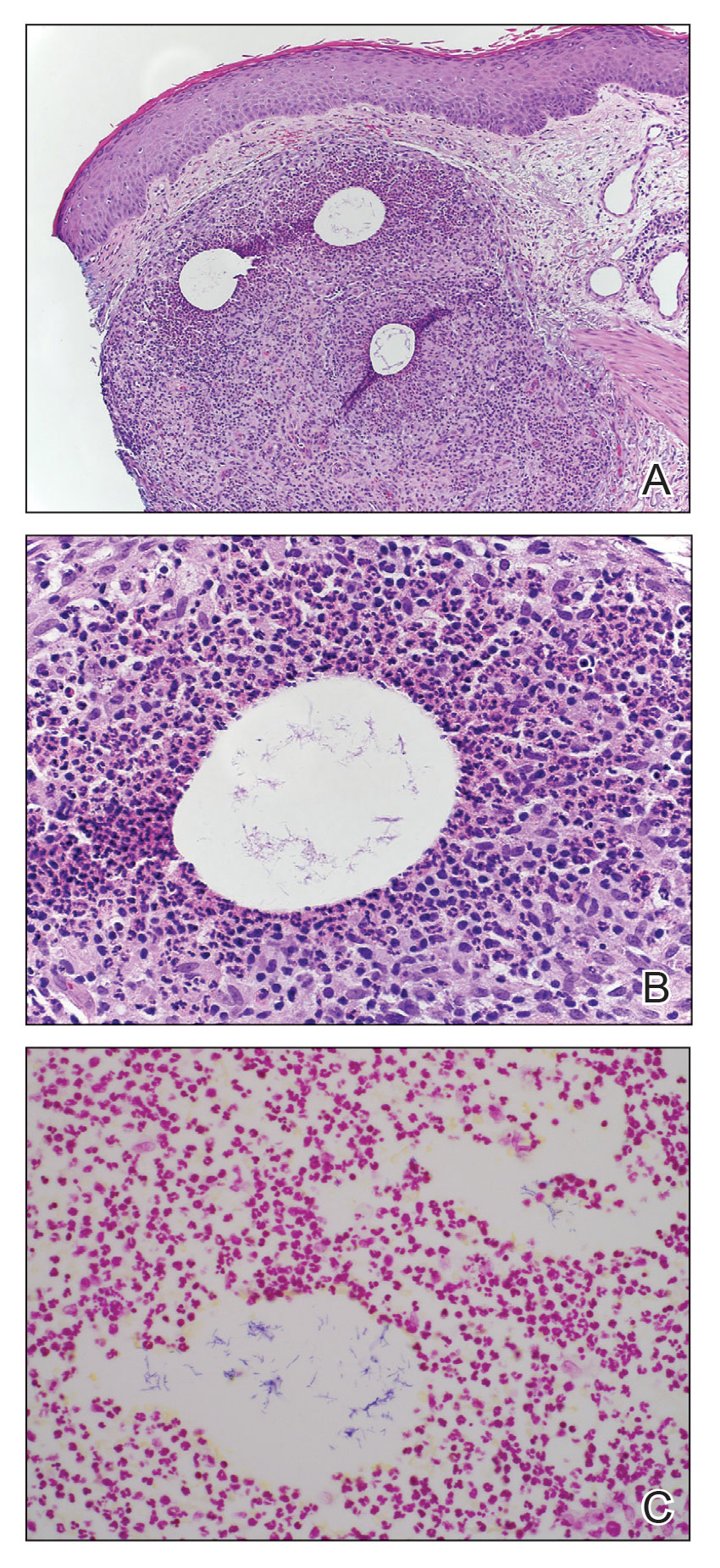

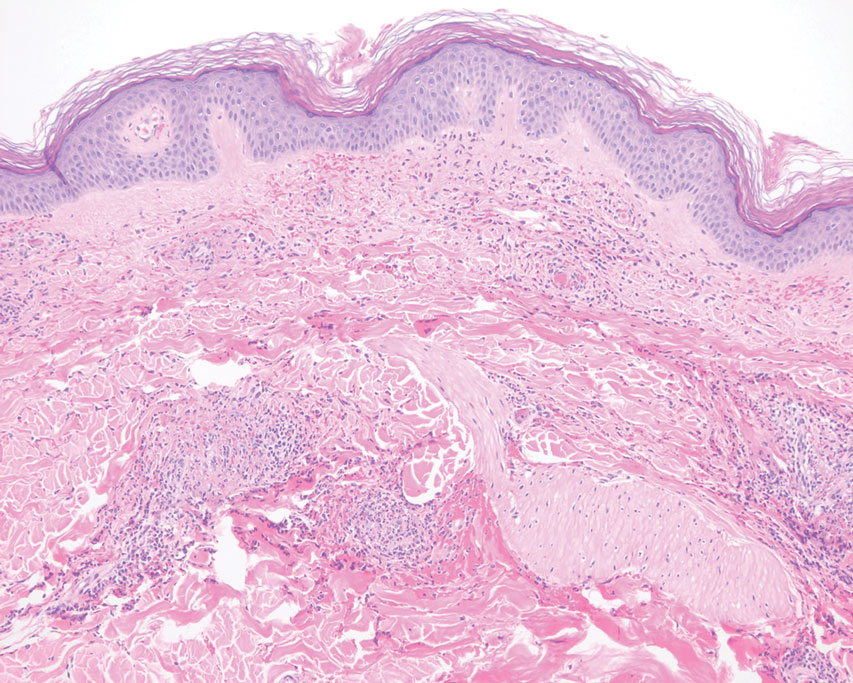

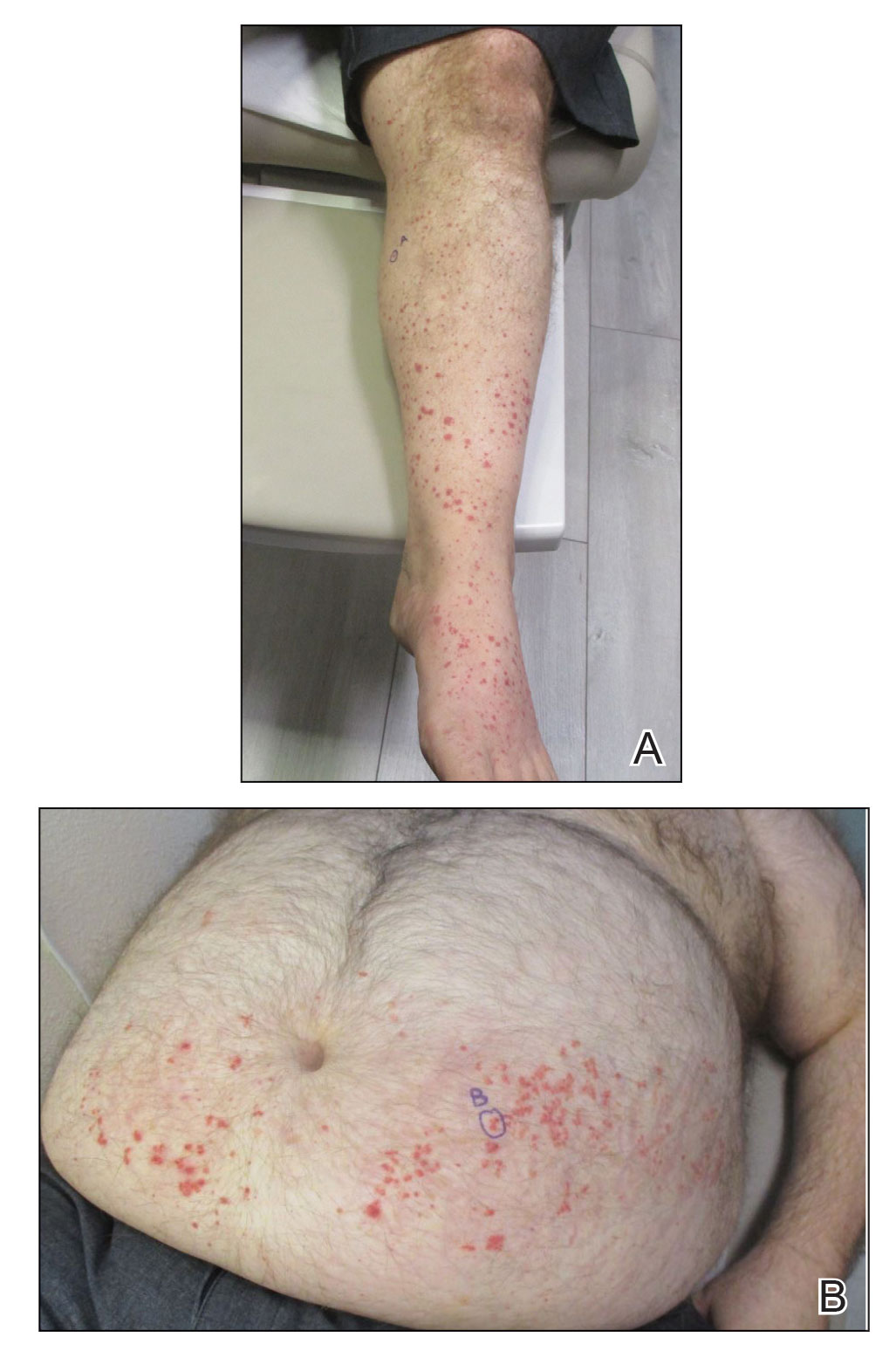

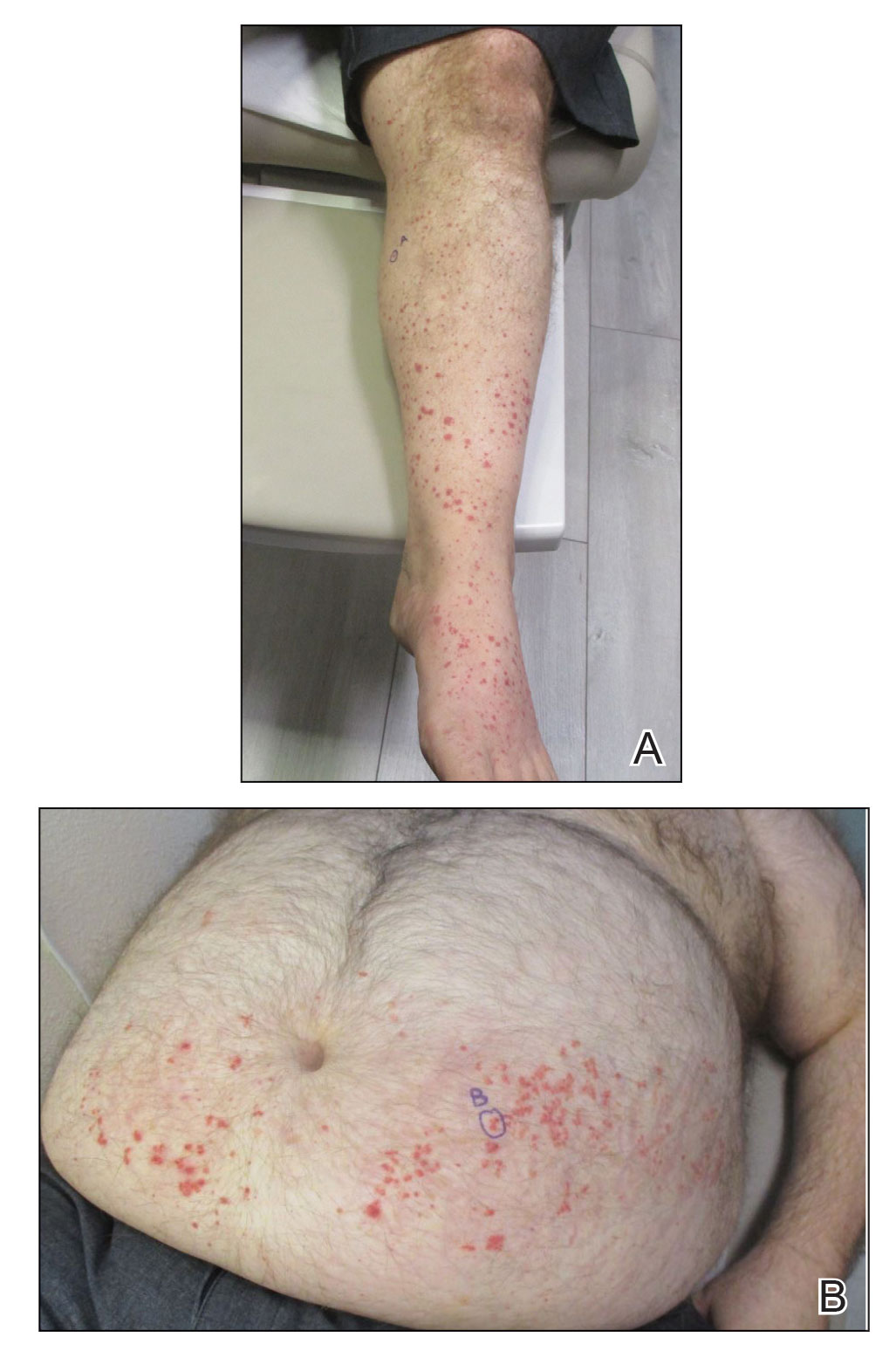

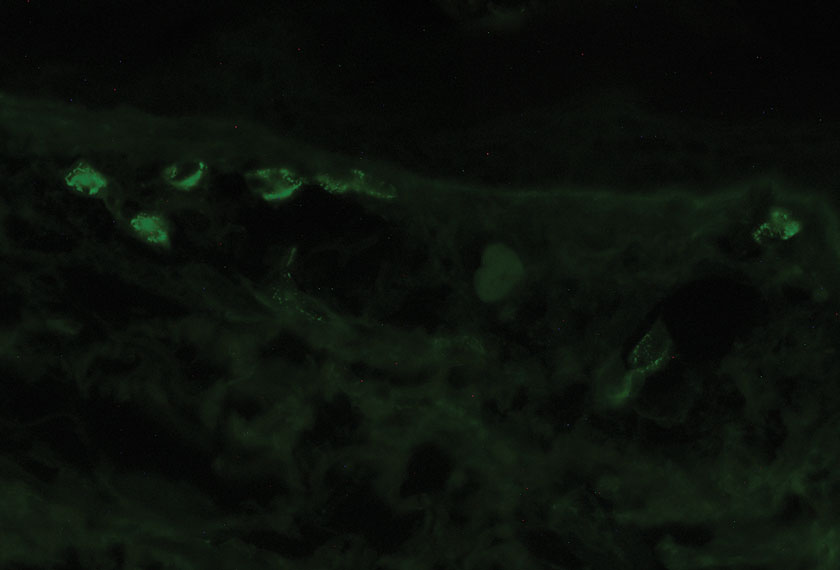

LCV is a small vessel vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and venules. Histologically, LCV is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall with frequent neutrophils, nuclear dust, and extravasated erythrocytes.3

Although a thorough evaluation is recommended to determine etiology, about 50% of cases are idiopathic. The most common precipitants are acute infection or a new medication. Postinfectious LCV is most commonly seen after streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection. Among other infectious triggers, Mycobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, chlamydia, Neisseria, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis are noteworthy. Foods, autoimmune disease, collagen vascular disease, and malignancy are also associated with LCV.4

In our patient we could not find any specific identifiable triggers. However, the presence of a UTI as a precipitating factor cannot be ruled out.5 Moreover, the patient received ciprofloxacin and there have been several case reports of LCV associated with use of a fluroquinolone.6 Nevertheless, in the presence of chronic ITP, which also is an auto-immune condition, an idiopathic cause seemed a reasonable explanation for the patient’s etiopathogenesis.

The cutaneous manifestations of LCV may appear about 1 to 3 weeks after the triggering event if present. The major clinical findings include palpable purpura and/or petechiae that are nonblanching. These findings can easily be confused with other diagnoses especially in the presence of a similar preexisting diagnosis. For example, our patient already had chronic ITP, and in such circumstances, a diagnosis of superimposed LCV can be easily missed without a thorough investigation. Extracutaneous manifestations with LCV are less common. Systemic symptoms may include low-grade fevers, malaise, weight loss, myalgia, and arthralgia. These findings have been noted in about 30% of affected patients, with arthralgia the most common manifestation.7 Our patient also presented with pain involving multiple joints.

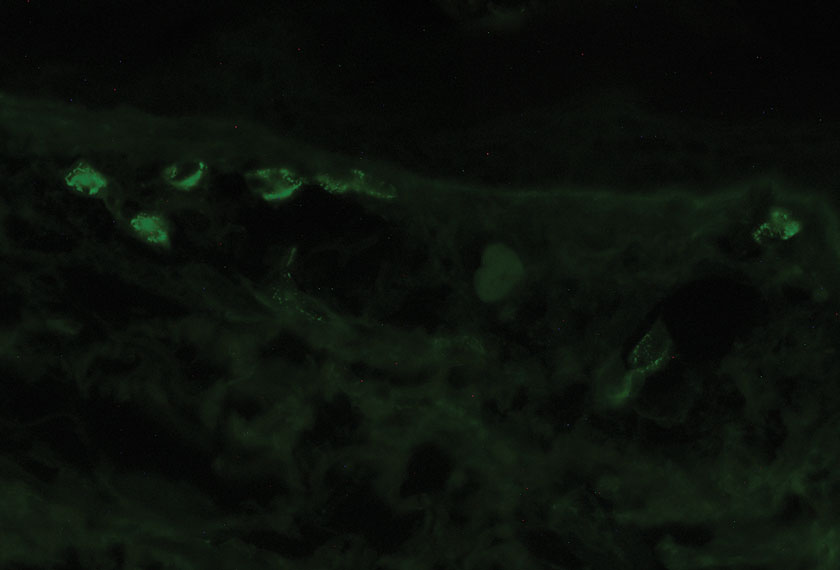

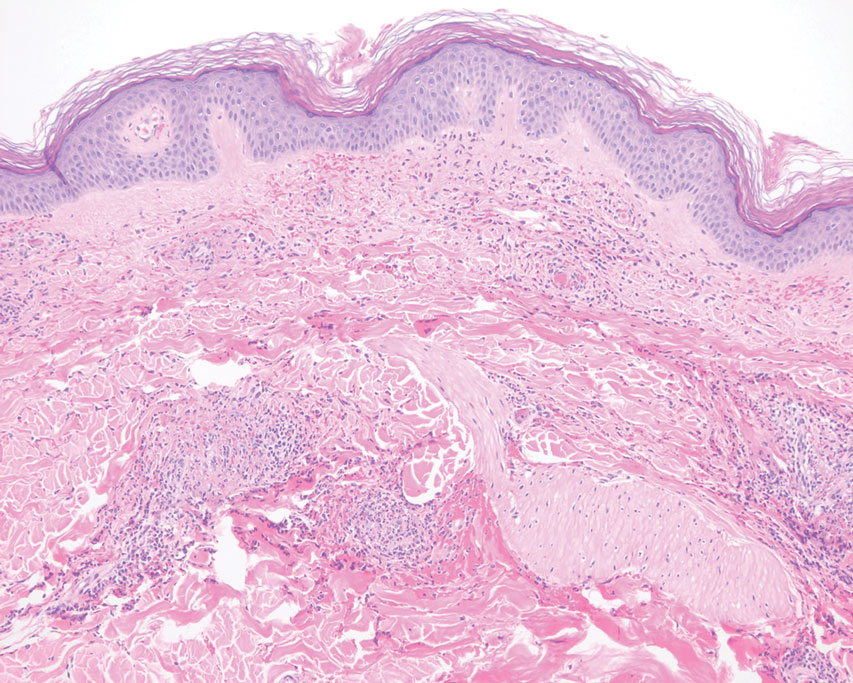

The mainstay of diagnosis for LCV is a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence. However, a workup for an underlying condition should be considered based on clinical suspicion. If a secondary cause is found, management should target treating the underlying cause, including withdrawal of the offending drug, treatment or control of the underlying infection, malignancy, or connective tissue disease. Most cases of idiopathic cutaneous LCV resolve with supportive measures, including leg elevation, rest, compression stockings, and antihistamines. In resistant cases, a 4- to 6-week tapering dose of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive steroid-sparing agents may be needed.8

Conclusions

Although most cases of LCV are mild and resolve without intervention, many cases go undiagnosed due to a delay in performing a biopsy. However, we should always look for the root cause of a patient’s condition to rule out underlying contributing conditions. Differentiating LCV from any other preexisting condition presenting similarly is important.

1. Gaurav K, Keith RM. Immune thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(3): 495-520. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.03.001

2. Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386-2393.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

4. Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19(3):77-78. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

5. The role of infectious agents in the pathogenesis of vasculitis. Nicolò P, Carlo S. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(5):897-911. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

6. Maunz G, Conzett T, Zimmerli W. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with fluoroquinolones. Infection. 2009;37(5):466-468. doi:10.1007/s15010-009-8437-4

7. Baigrie D, Goyal A, Crane J.C. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis. StatPearls [internet]. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482159

8. Micheletti RG, Pagnoux C. Management of cutaneous vasculitis. Presse Med. 2020; 49(3):104033. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2020.104033

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an immune-mediated acquired condition affecting both adults and children.1 Acute ITP is the most common form, which happens in the presence of a precipitant, leading to a drop in platelet counts. However, chronic ITP can occur when all the causes that might precipitate thrombocytopenia have been ruled out, and it is persistent for ≥ 12 months.2 Its presence can mask other diseases that exhibit somewhat similar signs and symptoms. We present a case of a patient presenting with chronic ITP with diffuse rash and was later diagnosed with idiopathic leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

Case Presentation

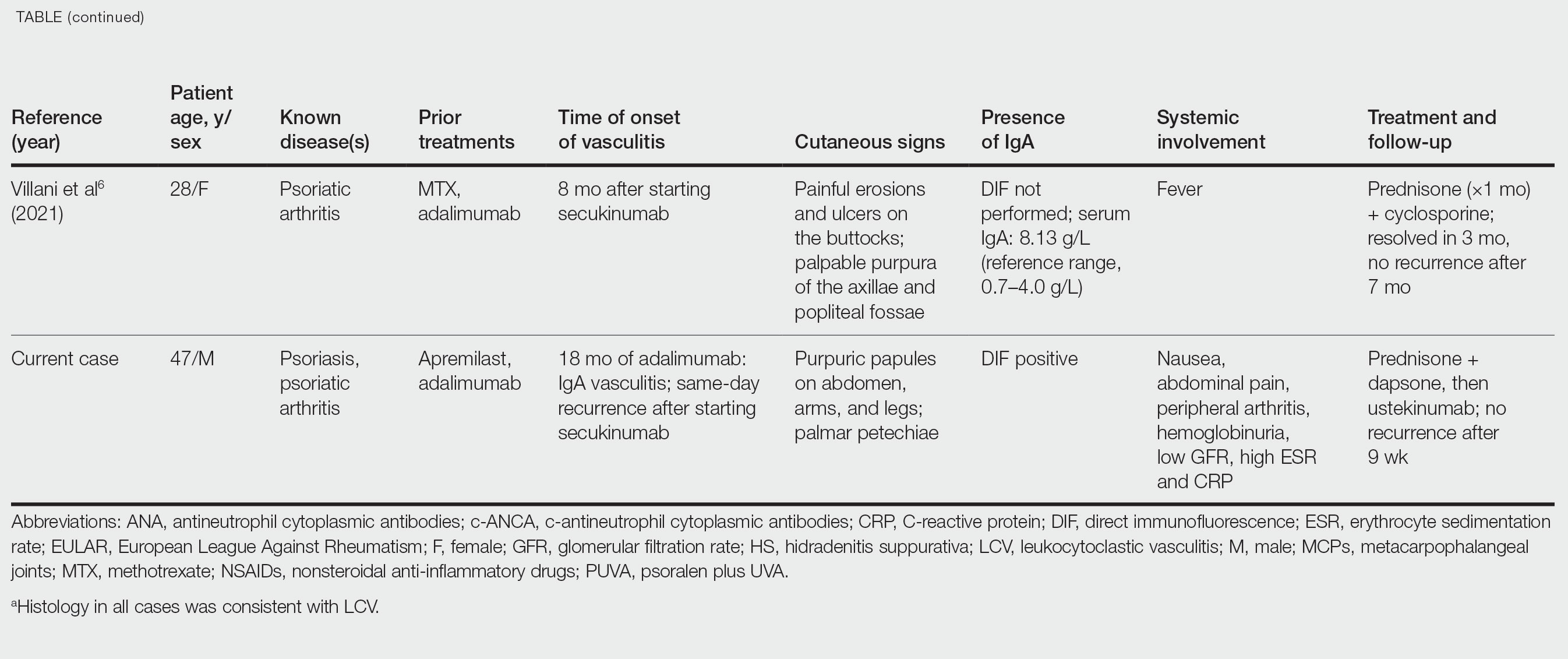

A 79-year-old presented to the hospital with 2-day history of a rash. The rash was purpureal and petechial and located on the trunk and bilateral upper and lower extremities. The rash was associated with itchiness and pain in the wrists, ankles, and small joints of the hands. The patient reported no changes in medication or diet,

The patient mentioned that at the time of diagnosis the platelet count was about 90,000 but had been fluctuating between 50 and 60,000 recently. The patient also reported no history of gum bleeding, nosebleeds, hemoptysis, hematemesis, or any miscarriages. She also had difficulty voiding for 2 to 3 days but no dysuria, frequency, urgency, or incontinence.

Laboratory results were significant for 57,000/µL platelet count (normal range, 150,000-450,000), elevated d-dimer (6.07), < 6 mg/dL C4 (normal range, 88-201). Hemoglobin level, coagulation panel, hemolytic panel, and fibrinogen level results were unremarkable. The hepatitis panel, Lyme disease, and HIV test were negative. The peripheral blood smear showed moderate thrombocytopenia, mild monocytosis, and borderline normochromic normocytic anemia without schistocytes. The autoimmune panel to evaluate thrombocytopenia showed platelet antibody against glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa, GP Ib/Ix, GP Ia/IIa, suggestive toward a diagnosis of chronic idiopathic ITP. However, the skin biopsy of the rash was indicative of LCV.

An autoimmune panel for vasculitis, including antinuclear antibody and antidouble-stranded DNA, was negative. While in the hospital, the patient completed the course of ciprofloxacin for the UTI, the rash started to fade without any intervention, and the platelet count improved to 69,000/µL. The patient was discharged after 3 days with the recommendation to follow up with her hematologist.

Discussion

LCV is a small vessel vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and venules. Histologically, LCV is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall with frequent neutrophils, nuclear dust, and extravasated erythrocytes.3

Although a thorough evaluation is recommended to determine etiology, about 50% of cases are idiopathic. The most common precipitants are acute infection or a new medication. Postinfectious LCV is most commonly seen after streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection. Among other infectious triggers, Mycobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, chlamydia, Neisseria, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis are noteworthy. Foods, autoimmune disease, collagen vascular disease, and malignancy are also associated with LCV.4

In our patient we could not find any specific identifiable triggers. However, the presence of a UTI as a precipitating factor cannot be ruled out.5 Moreover, the patient received ciprofloxacin and there have been several case reports of LCV associated with use of a fluroquinolone.6 Nevertheless, in the presence of chronic ITP, which also is an auto-immune condition, an idiopathic cause seemed a reasonable explanation for the patient’s etiopathogenesis.

The cutaneous manifestations of LCV may appear about 1 to 3 weeks after the triggering event if present. The major clinical findings include palpable purpura and/or petechiae that are nonblanching. These findings can easily be confused with other diagnoses especially in the presence of a similar preexisting diagnosis. For example, our patient already had chronic ITP, and in such circumstances, a diagnosis of superimposed LCV can be easily missed without a thorough investigation. Extracutaneous manifestations with LCV are less common. Systemic symptoms may include low-grade fevers, malaise, weight loss, myalgia, and arthralgia. These findings have been noted in about 30% of affected patients, with arthralgia the most common manifestation.7 Our patient also presented with pain involving multiple joints.

The mainstay of diagnosis for LCV is a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence. However, a workup for an underlying condition should be considered based on clinical suspicion. If a secondary cause is found, management should target treating the underlying cause, including withdrawal of the offending drug, treatment or control of the underlying infection, malignancy, or connective tissue disease. Most cases of idiopathic cutaneous LCV resolve with supportive measures, including leg elevation, rest, compression stockings, and antihistamines. In resistant cases, a 4- to 6-week tapering dose of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive steroid-sparing agents may be needed.8

Conclusions

Although most cases of LCV are mild and resolve without intervention, many cases go undiagnosed due to a delay in performing a biopsy. However, we should always look for the root cause of a patient’s condition to rule out underlying contributing conditions. Differentiating LCV from any other preexisting condition presenting similarly is important.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an immune-mediated acquired condition affecting both adults and children.1 Acute ITP is the most common form, which happens in the presence of a precipitant, leading to a drop in platelet counts. However, chronic ITP can occur when all the causes that might precipitate thrombocytopenia have been ruled out, and it is persistent for ≥ 12 months.2 Its presence can mask other diseases that exhibit somewhat similar signs and symptoms. We present a case of a patient presenting with chronic ITP with diffuse rash and was later diagnosed with idiopathic leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV).

Case Presentation

A 79-year-old presented to the hospital with 2-day history of a rash. The rash was purpureal and petechial and located on the trunk and bilateral upper and lower extremities. The rash was associated with itchiness and pain in the wrists, ankles, and small joints of the hands. The patient reported no changes in medication or diet,

The patient mentioned that at the time of diagnosis the platelet count was about 90,000 but had been fluctuating between 50 and 60,000 recently. The patient also reported no history of gum bleeding, nosebleeds, hemoptysis, hematemesis, or any miscarriages. She also had difficulty voiding for 2 to 3 days but no dysuria, frequency, urgency, or incontinence.

Laboratory results were significant for 57,000/µL platelet count (normal range, 150,000-450,000), elevated d-dimer (6.07), < 6 mg/dL C4 (normal range, 88-201). Hemoglobin level, coagulation panel, hemolytic panel, and fibrinogen level results were unremarkable. The hepatitis panel, Lyme disease, and HIV test were negative. The peripheral blood smear showed moderate thrombocytopenia, mild monocytosis, and borderline normochromic normocytic anemia without schistocytes. The autoimmune panel to evaluate thrombocytopenia showed platelet antibody against glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa, GP Ib/Ix, GP Ia/IIa, suggestive toward a diagnosis of chronic idiopathic ITP. However, the skin biopsy of the rash was indicative of LCV.

An autoimmune panel for vasculitis, including antinuclear antibody and antidouble-stranded DNA, was negative. While in the hospital, the patient completed the course of ciprofloxacin for the UTI, the rash started to fade without any intervention, and the platelet count improved to 69,000/µL. The patient was discharged after 3 days with the recommendation to follow up with her hematologist.

Discussion

LCV is a small vessel vasculitis of the dermal capillaries and venules. Histologically, LCV is characterized by fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel wall with frequent neutrophils, nuclear dust, and extravasated erythrocytes.3

Although a thorough evaluation is recommended to determine etiology, about 50% of cases are idiopathic. The most common precipitants are acute infection or a new medication. Postinfectious LCV is most commonly seen after streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection. Among other infectious triggers, Mycobacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, chlamydia, Neisseria, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis are noteworthy. Foods, autoimmune disease, collagen vascular disease, and malignancy are also associated with LCV.4

In our patient we could not find any specific identifiable triggers. However, the presence of a UTI as a precipitating factor cannot be ruled out.5 Moreover, the patient received ciprofloxacin and there have been several case reports of LCV associated with use of a fluroquinolone.6 Nevertheless, in the presence of chronic ITP, which also is an auto-immune condition, an idiopathic cause seemed a reasonable explanation for the patient’s etiopathogenesis.

The cutaneous manifestations of LCV may appear about 1 to 3 weeks after the triggering event if present. The major clinical findings include palpable purpura and/or petechiae that are nonblanching. These findings can easily be confused with other diagnoses especially in the presence of a similar preexisting diagnosis. For example, our patient already had chronic ITP, and in such circumstances, a diagnosis of superimposed LCV can be easily missed without a thorough investigation. Extracutaneous manifestations with LCV are less common. Systemic symptoms may include low-grade fevers, malaise, weight loss, myalgia, and arthralgia. These findings have been noted in about 30% of affected patients, with arthralgia the most common manifestation.7 Our patient also presented with pain involving multiple joints.

The mainstay of diagnosis for LCV is a skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence. However, a workup for an underlying condition should be considered based on clinical suspicion. If a secondary cause is found, management should target treating the underlying cause, including withdrawal of the offending drug, treatment or control of the underlying infection, malignancy, or connective tissue disease. Most cases of idiopathic cutaneous LCV resolve with supportive measures, including leg elevation, rest, compression stockings, and antihistamines. In resistant cases, a 4- to 6-week tapering dose of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive steroid-sparing agents may be needed.8

Conclusions

Although most cases of LCV are mild and resolve without intervention, many cases go undiagnosed due to a delay in performing a biopsy. However, we should always look for the root cause of a patient’s condition to rule out underlying contributing conditions. Differentiating LCV from any other preexisting condition presenting similarly is important.

1. Gaurav K, Keith RM. Immune thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(3): 495-520. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.03.001

2. Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386-2393.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

4. Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19(3):77-78. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

5. The role of infectious agents in the pathogenesis of vasculitis. Nicolò P, Carlo S. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(5):897-911. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

6. Maunz G, Conzett T, Zimmerli W. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with fluoroquinolones. Infection. 2009;37(5):466-468. doi:10.1007/s15010-009-8437-4

7. Baigrie D, Goyal A, Crane J.C. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis. StatPearls [internet]. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482159

8. Micheletti RG, Pagnoux C. Management of cutaneous vasculitis. Presse Med. 2020; 49(3):104033. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2020.104033

1. Gaurav K, Keith RM. Immune thrombocytopenia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(3): 495-520. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.03.001

2. Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;113(11):2386-2393.

3. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

4. Einhorn J, Levis JT. Dermatologic diagnosis: leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Perm J. 2015;19(3):77-78. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

5. The role of infectious agents in the pathogenesis of vasculitis. Nicolò P, Carlo S. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(5):897-911. doi:10.7812/TPP/15-001

6. Maunz G, Conzett T, Zimmerli W. Cutaneous vasculitis associated with fluoroquinolones. Infection. 2009;37(5):466-468. doi:10.1007/s15010-009-8437-4

7. Baigrie D, Goyal A, Crane J.C. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis. StatPearls [internet]. Updated May 8, 2022. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482159

8. Micheletti RG, Pagnoux C. Management of cutaneous vasculitis. Presse Med. 2020; 49(3):104033. doi:10.1016/j.lpm.2020.104033

Challenges and Considerations in Treating Negative and Cognitive Symptoms of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) represent some of the most debilitating mental health disorders.1 While these disorders have myriad presentations, the prototypical patient with SSD is often thought to possess positive symptoms. More recently, clinicians and researchers are raising awareness of another presentation of SSD: predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms. This symptom profile is not a novel phenomenon; for many years this presentation was recognized as a “deficit” presentation, referring to negative symptoms as the prominent feature.2,3 However, it presents unique diagnostic and treatment considerations that are often underappreciated in clinical settings.

Negative symptoms (blunted/flat affect, avolition, alogia, anhedonia, asociality) have long been identified as key features of SSD and are widely recognized as predictive of poor prognostic outcomes for patients with SSDs.1 In many patients, negative symptoms may precede the development of positive symptoms and emerge as a more robust predictor of functional outcomes than positive symptoms.1 Negative symptoms also appear to be inextricably linked to cognitive symptoms. Specifically, patients with primary negative symptoms seem to perform poorly on measures of global cognitive functioning.1 Similar to negative symptoms, cognitive symptoms of SSDs are a primary source of functional impairment and persistent disability.1 Despite this, little attention is given in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) to the neurocognitive and social cognitive deficits seen in patients with SSDs. Previous research highlights broad deficits in a range of neurocognitive abilities, including attention, working memory, processing speed, executive functioning, learning and memory, and receptive and expressive language.4 Similarly, patients also display deficits in domains of social cognition, such as emotion processing, identifying and utilizing social cues, evaluating attributions of others, and perspective-taking.5

A predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation can present diagnostic and treatment challenges. We present a case of a patient with such a presentation and the unique considerations given to diagnostic clarification and her treatment.

Case Presentation

A 33-year-old female veteran presented to the emergency department (ED) at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, in 2020. She was brought to the ED by local police following an attempted assault of her neighbor. Per collateral information from the police, the veteran stated she “had the urge to hurt someone” but was unable to provide any other information about this event. The veteran demonstrated diminished speech output, providing 2- to 3-word responses before refusing to speak entirely. She also presented with markedly blunted affect and tangential speech. She was not oriented to situation, stating confusion as to how she was brought to the hospital, and appeared to be responding to internal stimuli. She was subsequently admitted to the inpatient mental health unit due to unspecified psychosis.

The veteran presented as an unreliable historian, and much of her medical history was obtained via a review of US Department of Defense (DoD) records and collateral interview with her parents. Before her hospitalization, the veteran had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) and adjustment disorder while serving in the Navy. Her psychiatric history before her military career was otherwise unremarkable. At that time, she began a trial of sertraline 50 mg and completed 10 sessions of psychotherapy. After approximately 1 year, she elected to stop taking sertraline due to improved mental health. However, shortly after this she began experiencing significant depressive symptoms and was ultimately released early from the Navy due to her mental health concerns.

The veteran’s parents provided interim history between her discharge and establishing care at MEDVAMC as the veteran was reluctant to discuss this period of her life. According to her parents the veteran had prior diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD and had difficulty adhering to her current medications (bupropion and duloxetine) for about 1 month before her hospitalization. During the previous month, her parents observed her staying in her room around the clock and “[going] mute.”

The veteran remained hospitalized for about 1 month, during which she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and stabilized on injections of long-acting olanzapine 210 mg (administered every 2 weeks). She was referred for outpatient psychotherapy in a specialty clinic for veterans with SSDs. However, she did not attend her initial intake assessment.

About 2 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the veteran presented for her injection appointment. At this time, she was noted to be disorganized in her thinking and behavior, displaying thought blocking and catatonic behavior. Her parents also described concerning behavior since her discharge. They stated she went to a hotel after her discharge and spent all her available money. She then returned to her parents’ home, where she did not sleep or bathe for several days. She was observed wandering around the house aimlessly and in a confused manner and had become verbally aggressive and threatening toward her parents. The veteran was again psychiatrically admitted due to psychosis and concerns for her safety. She was discharged about 2 weeks later and continued olanzapine injections. She was also referred for outpatient psychotherapy; although she did not initially engage in psychotherapy, she was referred again about 5 months after discharge and began psychotherapy at that time.

The veteran began a course of weekly outpatient psychotherapy employing cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CBTp).6 During this time, she described her primary concerns as anxiety and feeling disconnected from others. She reported a history of depression but not of schizoaffective disorder. When asked about this, the veteran stated that she did not feel this diagnosis was accurate and instead believed she had severe depression. When asked why she was prescribed olanzapine, the veteran stated that this medication was for depression. As with her inpatient stays, the veteran demonstrated several negative symptoms during her course of psychotherapy. She presented with noticeably blunted affect, evidenced by lack of facial expression and monotonic speech. She also routinely displayed alogia (ie, lack of speech), often stating that she “did not feel like talking much.” She described difficulty finding motivation to initiate tasks (avolition) as well as a tendency toward social isolation (asociality).

The veteran also described concerns related to neurocognitive and social cognitive symptoms. She reported difficulties in processing speed, cognitive set-shifting (mentally switching between tasks), and inhibition, describing how these concerns interfered with her occupational functioning. She noted difficulty maintaining the expected pace of work at her previous positions, stating that she felt it took her longer to complete tasks compared with others. In addition, she displayed some difficulties with attention and memory. On more than one occasion, she seemed to have forgotten the previous day’s conversations with clinicians. Regarding social cognitive symptoms, she noted difficulties in emotion processing, indicating that it was difficult for her to identify and manage her emotions. This was especially prominent during times of depressed mood.

She also displayed a hostile attribution bias, or tendency to overattribute hostile intent to others’ ambiguous actions. For example, she described an instance where a family member sat too close to her on the couch, stating that she felt this behavior indicated the family member did not care about her. Relatedly, the veteran demonstrated difficulty with perspective taking, which became evident during cognitive restructuring regarding interpretations of her family’s behavior. Finally, the veteran displayed some deficits in social perception, or the ability to identify social context and rules based on nonverbal communication, verbal cues, and vocal intonation. She stated that she often felt conversing with others was difficult for her and indicated that she was “not good at conversations.” This may have in part been due to deficits in social perception.

During the first 2 months of psychotherapy, the veteran regularly attended sessions (conducted over telephone due to the COVID-19 pandemic) and was adherent to twice-weekly olanzapine injections. Despite this, she began experiencing an increase in depressive symptoms accompanied by a noticeable worsening of her blunted affect, alogia, and avolition. After about 2 months of psychotherapy, she described active suicidal ideation and requested to be voluntarily hospitalized. During this hospitalization, the veteran was consulted about the use of clozapine in treatment-refractory conditions and began a trial of clozapine 400 mg. She demonstrated marked improvement in her depressed mood after taking the medication and was discharged about 2 weeks after admission. The veteran completed 10 sessions of CBTp before electing to terminate due to an upcoming move. She was adherent to weekly blood draws per the requirements of clozapine and described intentions to engage in mental health care after her move. The patient’s mother contacted the clinic to inform the treatment team that the patient and her family had moved to a different city and the patient had started receiving care at the VAMC in that city.

Discussion

As the veteran’s case highlights, a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation may present diagnostic challenges. Since this presentation may not be viewed as representative of SSDs, patients with this presentation may be misdiagnosed. This was evident in the current case, not only in the veteran’s prodromal phase of illness while in the Navy, but also in her reported previous diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD. More than one clinician at the MEDVAMC provisionally considered a diagnosis of MDD before collecting collateral information from the veteran’s family regarding her clear psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, such misdiagnoses may have prevented early intervention of the veteran’s schizoaffective disorder, which is found to be instrumental in reducing impairment and disability among patients with SSDs.7,8

These misdiagnoses are understandable given the considerable symptom overlap between SSDs and other mental health disorders. For instance, anhedonia and avolition are 2 key symptoms seen in depressive episodes. Both anhedonia and lack of positive emotion are often seen in posttraumatic stress disorder. Additionally, anxiety disorders may induce a lack of positive emotion, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, and lack of motivation secondary to primary symptoms of anxiety. Furthermore, schizoaffective disorder requires the presence of a major mood episode. In the absence of apparent positive symptoms (as is the case for patients with a predominantly negative symptom presentation), schizoaffective disorder may be easily misdiagnosed as a mood disorder.

Patients with predominantly negative or cognitive symptoms may also be less accepting of a diagnosis of SSD. A wealth of research points to the clear stigma of SSDs, with many suggesting that these disorders are among the most stigmatized mental health disorders.9 Therefore, patients with predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms may be more likely to attribute their symptoms to another, less stigmatized mental health disorder. This was seen in the current case, as the veteran repeatedly denied a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and instead claimed to have severe depression. This reluctance to accept a diagnosis of an SSD, coupled with the diagnostic ambiguity of negative symptoms, is likely to make it challenging for clinicians to accurately identify patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation of SSDs.

Clinicians working within a team-based setting may be less likely to misdiagnose patients as they can consult others. Diagnostic clarity in the current case was undoubtedly facilitated by the multidisciplinary team involved in the veteran’s care; clinicians involved in her care were able to consult with one another to determine that her symptoms were indicative of an SSD rather than a mood disorder. Mental health professionals in private practice are unlikely to have access to such multidisciplinary specialty services and may be particularly vulnerable to misdiagnoses.

Treatment Considerations

This case also highlights several psychotherapy and psychopharmacology treatment considerations for patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation. The veteran was initially difficult to engage in psychotherapy. Although patients with SSDs often have difficulty engaging in treatment, patients with a predominant negative and cognitive symptom profile may experience more difficulty doing so.10 Previous research suggests that both negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms are inversely related to treatment engagement.11,12

By their very nature, negative symptoms may make it difficult to fully engage in psychotherapy. First, avolition and amotivation likely make it difficult for patients to attend psychotherapy appointments. Furthermore, negative symptoms may make it difficult to emotionally engage with the content of psychotherapy, thus limiting the potential benefits. Cognitive symptoms may also make it more difficult for patients to fully reap the benefits of psychotherapy. Deficits in attention, memory, and abstract reasoning seen in other mental health and medical conditions are associated with poorer treatment outcomes in psychotherapy.13,14 Thus, it may be especially difficult to engage patients with primarily negative and cognitive symptoms of SSDs in psychotherapy. However, given the link between these symptoms and functional impairment, it is even more important to evaluate and address such barriers to treatment.

This case highlights the utility of clozapine in the treatment of SSDs. Many commonly prescribed antipsychotic medications have questionable efficacy in treating negative symptoms, and none of the currently available antipsychotics are approved for this indication.15 In our case, the veteran saw a limited reduction of her negative or cognitive symptoms from her use of olanzapine. However, case reports, naturalistic follow-up, and open-label studies suggest that clozapine may be efficacious in targeting negative symptoms of SSDs.16-19 Previous research also suggests clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in decreasing overall SSD symptoms.20,21 Additionally, there is initial evidence of the efficacy of clozapine in treating cognitive symptoms, suggesting that some areas of cognition may improve in response to this medication.22-24 On the other hand, a recent case study suggests high doses of clozapine may be associated with cognitive impairment, although cognitive impairment was still greater without medication than at this higher dose.25 Thus, further research is needed to refine our understanding of the impact of clozapine on cognitive symptoms in SSDs.

Despite the promising research behind clozapine, it remains widely underprescribed, likely due to concerns regarding the potential adverse effects.26,27 Clozapine has been associated with many adverse effects, the most concerning being neutropenia, which can lead to serious infection and death. Thus, one concern among clinicians may be the potential lethality of clozapine. However, a wealth of research indicates clozapine can be safely administered under medical supervision.26,28 In fact, clozapine has been linked to lower all-cause mortality rates and lower mortality rates by suicide compared with other antipsychotic medications.29-31 It may therefore be argued that clozapine lowers the overall risk of mortality. Prescribers may also be weary of adherence to regular blood tests that patients must undergo to monitor their risk for neutropenia. This is the most frequently cited anticipated barrier to beginning a trial of clozapine.27 These concerns may not be unfounded; indeed, if avolition and amotivation make it difficult to attend psychotherapy sessions, these factors may logically make it difficult to attend blood draw appointments. In response to such barriers, several solutions have been suggested regarding potential blood draw nonadherence, including the use of in-home treatment teams and point-of-care monitoring.32,33

Conclusions

Predominant negative and cognitive symptom presentations of SSDs require unique considerations to accurately identify and provide optimal treatment for patients with such presentations. As our case highlights, patients with such presentations may often be misdiagnosed, as negative and cognitive symptoms may be attributed to other disorders. Additionally, patients with this presentation may experience difficulty engaging in psychotherapy and may not see the same benefits from common antipsychotic medications as patients with predominantly positive symptoms. Clozapine emerges as a promising treatment for addressing negative and cognitive symptoms, although it remains widely underutilized. In cases where clinicians encounter patients with predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms, we strongly recommend consultation and referral to psychiatric care for medication management.

The current case highlights the need for individually tailored treatment plans for individuals seeking mental health care. Clinicians of patients with any mental disorder, but especially those with SSDs of predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms, should carefully formulate a treatment plan based on relevant case history, presentation, and current empirical literature. A singular, one-size-fits-all approach should not be universally implemented for such patients. Our case demonstrates how careful multidisciplinary evaluations, review of medical records, collateral information from patients’ family members, and other diagnostic and treatment considerations in patients with predominant negative and cognitive symptoms of SSDs can refine and enhance the clinical care offered to such patients.

Acknowledgments

A.K. is supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and the VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans.

1. Kantrowitz JT. Managing negative symptoms of schizophrenia: how far have we come? CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):373-388. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0428-x

2. Fenton WS, McGlashan TH. Antecedents, symptom progression, and long-term outcome of the deficit syndrome in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(3):351-356. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.3.351

3. Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, Carpenter WT. A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(2):165. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.165

4. Kalkstein S, Hurford I, Gur RC. Neurocognition in schizophrenia. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;4:373-390. doi:10.1007/7854_2010_42

5. Green MF, Horan WP. Social cognition in schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(4):243-248. doi:10.1177/0963721410377600

6. Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive Therapy of Schizophrenia. Guilford Press; 2008.

7. Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623

8. McGorry PD. Early intervention in psychosis: obvious, effective, overdue. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):310-318. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000284

9. Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(1):4-7. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.1.4

10. Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):13-20. doi:10.1002/wps.20306

11. Kukla M, Davis LW, Lysaker PH. Cognitive behavioral therapy and work outcomes: correlates of treatment engagement and full and partial success in schizophrenia. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;42(5):577-592. doi:10.1017/S1352465813000428

12. Johansen R, Hestad K, Iversen VC, et al. Cognitive and clinical factors are associated with service engagement in early-phase schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(3):176-182. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31820bc2f9

13. Aharonovich E, Hasin DS, Brooks AC, Liu X, Bisaga A, Nunes EV. Cognitive deficits predict low treatment retention in cocaine dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(3):313-322. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.003

14. Aarsland D, Taylor JP, Weintraub D. Psychiatric issues in cognitive impairment. Mov Disord. 2014;29(5):651-662. doi:10.1002/mds.25873

15. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3

16. Khan AH, Zaidi S. Clozapine: Improvement of Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Cureus. 2017;9(12):e1973. Published 2017 Dec 20. doi:10.7759/cureus.1973

17. Brar JS, Chengappa KN, Parepally H, et al. The effects of clozapine on negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia with minimal positive symptoms. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997;9(4):227-234. doi:10.1023/a:1022352326334

18. Llorca PM, Lancon C, Farisse J, Scotto JC. Clozapine and negative symptoms. An open study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2000;24(3):373-384. doi:10.1016/s0278-5846(99)00105-0

19. Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):385-392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.115.177261

20. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600-610. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.600

21. Stroup TS, Gerhard T, Crystal S, Huang C, Olfson M. Comparative Effectiveness of Clozapine and Standard Antipsychotic Treatment in Adults With Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):166-173. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030332

22. Lee MA, Thompson PA, Meltzer HY. Effects of clozapine in cognitive function in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(suppl B):82-87.

23. Sharma T, Hughes C, Soni W, Kumari V. Cognitive effects of olanzapine and clozapine treatment in chronic schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2003;169(3-4):398-403. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1506-y

24. Spagna A, Dong Y, Mackie MA, et al. Clozapine improves the orienting of attention in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;168(1-2):285-291. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.009

25. Savulich G, Mezquida G, Atkinson S, Bernardo M, Fernandez-Egea E. A case study of clozapine and cognition: friend or foe? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38(2):152-153. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000847

26. Bogers JPAM, Schulte PFJ, Van Dijk D, Bakker B, Cohen D. Clozapine underutilization in the treatment of schizophrenia: how can clozapine prescription rates be improved? J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(2):109-111. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000478

27. Kelly DL, Freudenreich O, Sayer MA, Love RC. Addressing Barriers to Clozapine Underutilization: A National Effort. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):224-227. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700162

28. Honigfeld G, Arellano F, Sethi J, Bianchini A, Schein J. Reducing clozapine-related morbidity and mortality: 5 years of experience with the Clozaril National Registry. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):3-7.

29. Cho J, Hayes RD, Jewell A, et al. Clozapine and all-cause mortality in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a historical cohort study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(3):237-247. doi:10.1111/acps.12989

30. Kane JM. Clozapine Reduces All-Cause Mortality. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):920-921. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17070770

31. Taipale H, Lähteenvuo M, Tanskanen A, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tiihonen J. Comparative Effectiveness of Antipsychotics for Risk of Attempted or Completed Suicide Among Persons With Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(1):23-30. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbaa111

32. Love RC, Kelly DL, Freudenreich O, Sayer MA. Clozapine underutilization: addressing the barriers. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2016. Accessed October 6, 2022. https://www.nasmhpd.org/sites/default/files/Assessment%201_Clozapine%20Underutilization.pdf

33. Kelly DL, Ben-Yoav H, Payne GF, et al. Blood draw barriers for treatment with clozapine and development of a point-of-care monitoring device. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2018;12(1):23-30. doi:10.3371/CSRP.KEBE.070415

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) represent some of the most debilitating mental health disorders.1 While these disorders have myriad presentations, the prototypical patient with SSD is often thought to possess positive symptoms. More recently, clinicians and researchers are raising awareness of another presentation of SSD: predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms. This symptom profile is not a novel phenomenon; for many years this presentation was recognized as a “deficit” presentation, referring to negative symptoms as the prominent feature.2,3 However, it presents unique diagnostic and treatment considerations that are often underappreciated in clinical settings.

Negative symptoms (blunted/flat affect, avolition, alogia, anhedonia, asociality) have long been identified as key features of SSD and are widely recognized as predictive of poor prognostic outcomes for patients with SSDs.1 In many patients, negative symptoms may precede the development of positive symptoms and emerge as a more robust predictor of functional outcomes than positive symptoms.1 Negative symptoms also appear to be inextricably linked to cognitive symptoms. Specifically, patients with primary negative symptoms seem to perform poorly on measures of global cognitive functioning.1 Similar to negative symptoms, cognitive symptoms of SSDs are a primary source of functional impairment and persistent disability.1 Despite this, little attention is given in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) to the neurocognitive and social cognitive deficits seen in patients with SSDs. Previous research highlights broad deficits in a range of neurocognitive abilities, including attention, working memory, processing speed, executive functioning, learning and memory, and receptive and expressive language.4 Similarly, patients also display deficits in domains of social cognition, such as emotion processing, identifying and utilizing social cues, evaluating attributions of others, and perspective-taking.5

A predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation can present diagnostic and treatment challenges. We present a case of a patient with such a presentation and the unique considerations given to diagnostic clarification and her treatment.

Case Presentation

A 33-year-old female veteran presented to the emergency department (ED) at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, in 2020. She was brought to the ED by local police following an attempted assault of her neighbor. Per collateral information from the police, the veteran stated she “had the urge to hurt someone” but was unable to provide any other information about this event. The veteran demonstrated diminished speech output, providing 2- to 3-word responses before refusing to speak entirely. She also presented with markedly blunted affect and tangential speech. She was not oriented to situation, stating confusion as to how she was brought to the hospital, and appeared to be responding to internal stimuli. She was subsequently admitted to the inpatient mental health unit due to unspecified psychosis.

The veteran presented as an unreliable historian, and much of her medical history was obtained via a review of US Department of Defense (DoD) records and collateral interview with her parents. Before her hospitalization, the veteran had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) and adjustment disorder while serving in the Navy. Her psychiatric history before her military career was otherwise unremarkable. At that time, she began a trial of sertraline 50 mg and completed 10 sessions of psychotherapy. After approximately 1 year, she elected to stop taking sertraline due to improved mental health. However, shortly after this she began experiencing significant depressive symptoms and was ultimately released early from the Navy due to her mental health concerns.

The veteran’s parents provided interim history between her discharge and establishing care at MEDVAMC as the veteran was reluctant to discuss this period of her life. According to her parents the veteran had prior diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD and had difficulty adhering to her current medications (bupropion and duloxetine) for about 1 month before her hospitalization. During the previous month, her parents observed her staying in her room around the clock and “[going] mute.”

The veteran remained hospitalized for about 1 month, during which she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and stabilized on injections of long-acting olanzapine 210 mg (administered every 2 weeks). She was referred for outpatient psychotherapy in a specialty clinic for veterans with SSDs. However, she did not attend her initial intake assessment.

About 2 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the veteran presented for her injection appointment. At this time, she was noted to be disorganized in her thinking and behavior, displaying thought blocking and catatonic behavior. Her parents also described concerning behavior since her discharge. They stated she went to a hotel after her discharge and spent all her available money. She then returned to her parents’ home, where she did not sleep or bathe for several days. She was observed wandering around the house aimlessly and in a confused manner and had become verbally aggressive and threatening toward her parents. The veteran was again psychiatrically admitted due to psychosis and concerns for her safety. She was discharged about 2 weeks later and continued olanzapine injections. She was also referred for outpatient psychotherapy; although she did not initially engage in psychotherapy, she was referred again about 5 months after discharge and began psychotherapy at that time.

The veteran began a course of weekly outpatient psychotherapy employing cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CBTp).6 During this time, she described her primary concerns as anxiety and feeling disconnected from others. She reported a history of depression but not of schizoaffective disorder. When asked about this, the veteran stated that she did not feel this diagnosis was accurate and instead believed she had severe depression. When asked why she was prescribed olanzapine, the veteran stated that this medication was for depression. As with her inpatient stays, the veteran demonstrated several negative symptoms during her course of psychotherapy. She presented with noticeably blunted affect, evidenced by lack of facial expression and monotonic speech. She also routinely displayed alogia (ie, lack of speech), often stating that she “did not feel like talking much.” She described difficulty finding motivation to initiate tasks (avolition) as well as a tendency toward social isolation (asociality).

The veteran also described concerns related to neurocognitive and social cognitive symptoms. She reported difficulties in processing speed, cognitive set-shifting (mentally switching between tasks), and inhibition, describing how these concerns interfered with her occupational functioning. She noted difficulty maintaining the expected pace of work at her previous positions, stating that she felt it took her longer to complete tasks compared with others. In addition, she displayed some difficulties with attention and memory. On more than one occasion, she seemed to have forgotten the previous day’s conversations with clinicians. Regarding social cognitive symptoms, she noted difficulties in emotion processing, indicating that it was difficult for her to identify and manage her emotions. This was especially prominent during times of depressed mood.

She also displayed a hostile attribution bias, or tendency to overattribute hostile intent to others’ ambiguous actions. For example, she described an instance where a family member sat too close to her on the couch, stating that she felt this behavior indicated the family member did not care about her. Relatedly, the veteran demonstrated difficulty with perspective taking, which became evident during cognitive restructuring regarding interpretations of her family’s behavior. Finally, the veteran displayed some deficits in social perception, or the ability to identify social context and rules based on nonverbal communication, verbal cues, and vocal intonation. She stated that she often felt conversing with others was difficult for her and indicated that she was “not good at conversations.” This may have in part been due to deficits in social perception.

During the first 2 months of psychotherapy, the veteran regularly attended sessions (conducted over telephone due to the COVID-19 pandemic) and was adherent to twice-weekly olanzapine injections. Despite this, she began experiencing an increase in depressive symptoms accompanied by a noticeable worsening of her blunted affect, alogia, and avolition. After about 2 months of psychotherapy, she described active suicidal ideation and requested to be voluntarily hospitalized. During this hospitalization, the veteran was consulted about the use of clozapine in treatment-refractory conditions and began a trial of clozapine 400 mg. She demonstrated marked improvement in her depressed mood after taking the medication and was discharged about 2 weeks after admission. The veteran completed 10 sessions of CBTp before electing to terminate due to an upcoming move. She was adherent to weekly blood draws per the requirements of clozapine and described intentions to engage in mental health care after her move. The patient’s mother contacted the clinic to inform the treatment team that the patient and her family had moved to a different city and the patient had started receiving care at the VAMC in that city.

Discussion

As the veteran’s case highlights, a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation may present diagnostic challenges. Since this presentation may not be viewed as representative of SSDs, patients with this presentation may be misdiagnosed. This was evident in the current case, not only in the veteran’s prodromal phase of illness while in the Navy, but also in her reported previous diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD. More than one clinician at the MEDVAMC provisionally considered a diagnosis of MDD before collecting collateral information from the veteran’s family regarding her clear psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, such misdiagnoses may have prevented early intervention of the veteran’s schizoaffective disorder, which is found to be instrumental in reducing impairment and disability among patients with SSDs.7,8

These misdiagnoses are understandable given the considerable symptom overlap between SSDs and other mental health disorders. For instance, anhedonia and avolition are 2 key symptoms seen in depressive episodes. Both anhedonia and lack of positive emotion are often seen in posttraumatic stress disorder. Additionally, anxiety disorders may induce a lack of positive emotion, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, and lack of motivation secondary to primary symptoms of anxiety. Furthermore, schizoaffective disorder requires the presence of a major mood episode. In the absence of apparent positive symptoms (as is the case for patients with a predominantly negative symptom presentation), schizoaffective disorder may be easily misdiagnosed as a mood disorder.

Patients with predominantly negative or cognitive symptoms may also be less accepting of a diagnosis of SSD. A wealth of research points to the clear stigma of SSDs, with many suggesting that these disorders are among the most stigmatized mental health disorders.9 Therefore, patients with predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms may be more likely to attribute their symptoms to another, less stigmatized mental health disorder. This was seen in the current case, as the veteran repeatedly denied a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and instead claimed to have severe depression. This reluctance to accept a diagnosis of an SSD, coupled with the diagnostic ambiguity of negative symptoms, is likely to make it challenging for clinicians to accurately identify patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation of SSDs.

Clinicians working within a team-based setting may be less likely to misdiagnose patients as they can consult others. Diagnostic clarity in the current case was undoubtedly facilitated by the multidisciplinary team involved in the veteran’s care; clinicians involved in her care were able to consult with one another to determine that her symptoms were indicative of an SSD rather than a mood disorder. Mental health professionals in private practice are unlikely to have access to such multidisciplinary specialty services and may be particularly vulnerable to misdiagnoses.

Treatment Considerations

This case also highlights several psychotherapy and psychopharmacology treatment considerations for patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation. The veteran was initially difficult to engage in psychotherapy. Although patients with SSDs often have difficulty engaging in treatment, patients with a predominant negative and cognitive symptom profile may experience more difficulty doing so.10 Previous research suggests that both negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms are inversely related to treatment engagement.11,12

By their very nature, negative symptoms may make it difficult to fully engage in psychotherapy. First, avolition and amotivation likely make it difficult for patients to attend psychotherapy appointments. Furthermore, negative symptoms may make it difficult to emotionally engage with the content of psychotherapy, thus limiting the potential benefits. Cognitive symptoms may also make it more difficult for patients to fully reap the benefits of psychotherapy. Deficits in attention, memory, and abstract reasoning seen in other mental health and medical conditions are associated with poorer treatment outcomes in psychotherapy.13,14 Thus, it may be especially difficult to engage patients with primarily negative and cognitive symptoms of SSDs in psychotherapy. However, given the link between these symptoms and functional impairment, it is even more important to evaluate and address such barriers to treatment.

This case highlights the utility of clozapine in the treatment of SSDs. Many commonly prescribed antipsychotic medications have questionable efficacy in treating negative symptoms, and none of the currently available antipsychotics are approved for this indication.15 In our case, the veteran saw a limited reduction of her negative or cognitive symptoms from her use of olanzapine. However, case reports, naturalistic follow-up, and open-label studies suggest that clozapine may be efficacious in targeting negative symptoms of SSDs.16-19 Previous research also suggests clozapine is more effective than other antipsychotic medications, including olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone, in decreasing overall SSD symptoms.20,21 Additionally, there is initial evidence of the efficacy of clozapine in treating cognitive symptoms, suggesting that some areas of cognition may improve in response to this medication.22-24 On the other hand, a recent case study suggests high doses of clozapine may be associated with cognitive impairment, although cognitive impairment was still greater without medication than at this higher dose.25 Thus, further research is needed to refine our understanding of the impact of clozapine on cognitive symptoms in SSDs.

Despite the promising research behind clozapine, it remains widely underprescribed, likely due to concerns regarding the potential adverse effects.26,27 Clozapine has been associated with many adverse effects, the most concerning being neutropenia, which can lead to serious infection and death. Thus, one concern among clinicians may be the potential lethality of clozapine. However, a wealth of research indicates clozapine can be safely administered under medical supervision.26,28 In fact, clozapine has been linked to lower all-cause mortality rates and lower mortality rates by suicide compared with other antipsychotic medications.29-31 It may therefore be argued that clozapine lowers the overall risk of mortality. Prescribers may also be weary of adherence to regular blood tests that patients must undergo to monitor their risk for neutropenia. This is the most frequently cited anticipated barrier to beginning a trial of clozapine.27 These concerns may not be unfounded; indeed, if avolition and amotivation make it difficult to attend psychotherapy sessions, these factors may logically make it difficult to attend blood draw appointments. In response to such barriers, several solutions have been suggested regarding potential blood draw nonadherence, including the use of in-home treatment teams and point-of-care monitoring.32,33

Conclusions

Predominant negative and cognitive symptom presentations of SSDs require unique considerations to accurately identify and provide optimal treatment for patients with such presentations. As our case highlights, patients with such presentations may often be misdiagnosed, as negative and cognitive symptoms may be attributed to other disorders. Additionally, patients with this presentation may experience difficulty engaging in psychotherapy and may not see the same benefits from common antipsychotic medications as patients with predominantly positive symptoms. Clozapine emerges as a promising treatment for addressing negative and cognitive symptoms, although it remains widely underutilized. In cases where clinicians encounter patients with predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms, we strongly recommend consultation and referral to psychiatric care for medication management.

The current case highlights the need for individually tailored treatment plans for individuals seeking mental health care. Clinicians of patients with any mental disorder, but especially those with SSDs of predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms, should carefully formulate a treatment plan based on relevant case history, presentation, and current empirical literature. A singular, one-size-fits-all approach should not be universally implemented for such patients. Our case demonstrates how careful multidisciplinary evaluations, review of medical records, collateral information from patients’ family members, and other diagnostic and treatment considerations in patients with predominant negative and cognitive symptoms of SSDs can refine and enhance the clinical care offered to such patients.

Acknowledgments

A.K. is supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Health Care System, and the VISN 17 Center of Excellence for Research on Returning War Veterans.

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSDs) represent some of the most debilitating mental health disorders.1 While these disorders have myriad presentations, the prototypical patient with SSD is often thought to possess positive symptoms. More recently, clinicians and researchers are raising awareness of another presentation of SSD: predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms. This symptom profile is not a novel phenomenon; for many years this presentation was recognized as a “deficit” presentation, referring to negative symptoms as the prominent feature.2,3 However, it presents unique diagnostic and treatment considerations that are often underappreciated in clinical settings.

Negative symptoms (blunted/flat affect, avolition, alogia, anhedonia, asociality) have long been identified as key features of SSD and are widely recognized as predictive of poor prognostic outcomes for patients with SSDs.1 In many patients, negative symptoms may precede the development of positive symptoms and emerge as a more robust predictor of functional outcomes than positive symptoms.1 Negative symptoms also appear to be inextricably linked to cognitive symptoms. Specifically, patients with primary negative symptoms seem to perform poorly on measures of global cognitive functioning.1 Similar to negative symptoms, cognitive symptoms of SSDs are a primary source of functional impairment and persistent disability.1 Despite this, little attention is given in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) to the neurocognitive and social cognitive deficits seen in patients with SSDs. Previous research highlights broad deficits in a range of neurocognitive abilities, including attention, working memory, processing speed, executive functioning, learning and memory, and receptive and expressive language.4 Similarly, patients also display deficits in domains of social cognition, such as emotion processing, identifying and utilizing social cues, evaluating attributions of others, and perspective-taking.5

A predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation can present diagnostic and treatment challenges. We present a case of a patient with such a presentation and the unique considerations given to diagnostic clarification and her treatment.

Case Presentation

A 33-year-old female veteran presented to the emergency department (ED) at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, in 2020. She was brought to the ED by local police following an attempted assault of her neighbor. Per collateral information from the police, the veteran stated she “had the urge to hurt someone” but was unable to provide any other information about this event. The veteran demonstrated diminished speech output, providing 2- to 3-word responses before refusing to speak entirely. She also presented with markedly blunted affect and tangential speech. She was not oriented to situation, stating confusion as to how she was brought to the hospital, and appeared to be responding to internal stimuli. She was subsequently admitted to the inpatient mental health unit due to unspecified psychosis.

The veteran presented as an unreliable historian, and much of her medical history was obtained via a review of US Department of Defense (DoD) records and collateral interview with her parents. Before her hospitalization, the veteran had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) and adjustment disorder while serving in the Navy. Her psychiatric history before her military career was otherwise unremarkable. At that time, she began a trial of sertraline 50 mg and completed 10 sessions of psychotherapy. After approximately 1 year, she elected to stop taking sertraline due to improved mental health. However, shortly after this she began experiencing significant depressive symptoms and was ultimately released early from the Navy due to her mental health concerns.

The veteran’s parents provided interim history between her discharge and establishing care at MEDVAMC as the veteran was reluctant to discuss this period of her life. According to her parents the veteran had prior diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD and had difficulty adhering to her current medications (bupropion and duloxetine) for about 1 month before her hospitalization. During the previous month, her parents observed her staying in her room around the clock and “[going] mute.”

The veteran remained hospitalized for about 1 month, during which she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and stabilized on injections of long-acting olanzapine 210 mg (administered every 2 weeks). She was referred for outpatient psychotherapy in a specialty clinic for veterans with SSDs. However, she did not attend her initial intake assessment.

About 2 weeks after discharge from the hospital, the veteran presented for her injection appointment. At this time, she was noted to be disorganized in her thinking and behavior, displaying thought blocking and catatonic behavior. Her parents also described concerning behavior since her discharge. They stated she went to a hotel after her discharge and spent all her available money. She then returned to her parents’ home, where she did not sleep or bathe for several days. She was observed wandering around the house aimlessly and in a confused manner and had become verbally aggressive and threatening toward her parents. The veteran was again psychiatrically admitted due to psychosis and concerns for her safety. She was discharged about 2 weeks later and continued olanzapine injections. She was also referred for outpatient psychotherapy; although she did not initially engage in psychotherapy, she was referred again about 5 months after discharge and began psychotherapy at that time.

The veteran began a course of weekly outpatient psychotherapy employing cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CBTp).6 During this time, she described her primary concerns as anxiety and feeling disconnected from others. She reported a history of depression but not of schizoaffective disorder. When asked about this, the veteran stated that she did not feel this diagnosis was accurate and instead believed she had severe depression. When asked why she was prescribed olanzapine, the veteran stated that this medication was for depression. As with her inpatient stays, the veteran demonstrated several negative symptoms during her course of psychotherapy. She presented with noticeably blunted affect, evidenced by lack of facial expression and monotonic speech. She also routinely displayed alogia (ie, lack of speech), often stating that she “did not feel like talking much.” She described difficulty finding motivation to initiate tasks (avolition) as well as a tendency toward social isolation (asociality).

The veteran also described concerns related to neurocognitive and social cognitive symptoms. She reported difficulties in processing speed, cognitive set-shifting (mentally switching between tasks), and inhibition, describing how these concerns interfered with her occupational functioning. She noted difficulty maintaining the expected pace of work at her previous positions, stating that she felt it took her longer to complete tasks compared with others. In addition, she displayed some difficulties with attention and memory. On more than one occasion, she seemed to have forgotten the previous day’s conversations with clinicians. Regarding social cognitive symptoms, she noted difficulties in emotion processing, indicating that it was difficult for her to identify and manage her emotions. This was especially prominent during times of depressed mood.

She also displayed a hostile attribution bias, or tendency to overattribute hostile intent to others’ ambiguous actions. For example, she described an instance where a family member sat too close to her on the couch, stating that she felt this behavior indicated the family member did not care about her. Relatedly, the veteran demonstrated difficulty with perspective taking, which became evident during cognitive restructuring regarding interpretations of her family’s behavior. Finally, the veteran displayed some deficits in social perception, or the ability to identify social context and rules based on nonverbal communication, verbal cues, and vocal intonation. She stated that she often felt conversing with others was difficult for her and indicated that she was “not good at conversations.” This may have in part been due to deficits in social perception.

During the first 2 months of psychotherapy, the veteran regularly attended sessions (conducted over telephone due to the COVID-19 pandemic) and was adherent to twice-weekly olanzapine injections. Despite this, she began experiencing an increase in depressive symptoms accompanied by a noticeable worsening of her blunted affect, alogia, and avolition. After about 2 months of psychotherapy, she described active suicidal ideation and requested to be voluntarily hospitalized. During this hospitalization, the veteran was consulted about the use of clozapine in treatment-refractory conditions and began a trial of clozapine 400 mg. She demonstrated marked improvement in her depressed mood after taking the medication and was discharged about 2 weeks after admission. The veteran completed 10 sessions of CBTp before electing to terminate due to an upcoming move. She was adherent to weekly blood draws per the requirements of clozapine and described intentions to engage in mental health care after her move. The patient’s mother contacted the clinic to inform the treatment team that the patient and her family had moved to a different city and the patient had started receiving care at the VAMC in that city.

Discussion

As the veteran’s case highlights, a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation may present diagnostic challenges. Since this presentation may not be viewed as representative of SSDs, patients with this presentation may be misdiagnosed. This was evident in the current case, not only in the veteran’s prodromal phase of illness while in the Navy, but also in her reported previous diagnoses of borderline personality disorder and MDD. More than one clinician at the MEDVAMC provisionally considered a diagnosis of MDD before collecting collateral information from the veteran’s family regarding her clear psychotic symptoms. Unfortunately, such misdiagnoses may have prevented early intervention of the veteran’s schizoaffective disorder, which is found to be instrumental in reducing impairment and disability among patients with SSDs.7,8

These misdiagnoses are understandable given the considerable symptom overlap between SSDs and other mental health disorders. For instance, anhedonia and avolition are 2 key symptoms seen in depressive episodes. Both anhedonia and lack of positive emotion are often seen in posttraumatic stress disorder. Additionally, anxiety disorders may induce a lack of positive emotion, loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, and lack of motivation secondary to primary symptoms of anxiety. Furthermore, schizoaffective disorder requires the presence of a major mood episode. In the absence of apparent positive symptoms (as is the case for patients with a predominantly negative symptom presentation), schizoaffective disorder may be easily misdiagnosed as a mood disorder.

Patients with predominantly negative or cognitive symptoms may also be less accepting of a diagnosis of SSD. A wealth of research points to the clear stigma of SSDs, with many suggesting that these disorders are among the most stigmatized mental health disorders.9 Therefore, patients with predominantly negative and cognitive symptoms may be more likely to attribute their symptoms to another, less stigmatized mental health disorder. This was seen in the current case, as the veteran repeatedly denied a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and instead claimed to have severe depression. This reluctance to accept a diagnosis of an SSD, coupled with the diagnostic ambiguity of negative symptoms, is likely to make it challenging for clinicians to accurately identify patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation of SSDs.

Clinicians working within a team-based setting may be less likely to misdiagnose patients as they can consult others. Diagnostic clarity in the current case was undoubtedly facilitated by the multidisciplinary team involved in the veteran’s care; clinicians involved in her care were able to consult with one another to determine that her symptoms were indicative of an SSD rather than a mood disorder. Mental health professionals in private practice are unlikely to have access to such multidisciplinary specialty services and may be particularly vulnerable to misdiagnoses.

Treatment Considerations

This case also highlights several psychotherapy and psychopharmacology treatment considerations for patients with a predominantly negative and cognitive symptom presentation. The veteran was initially difficult to engage in psychotherapy. Although patients with SSDs often have difficulty engaging in treatment, patients with a predominant negative and cognitive symptom profile may experience more difficulty doing so.10 Previous research suggests that both negative symptoms and cognitive symptoms are inversely related to treatment engagement.11,12