User login

Spontaneously Regressing Primary Nodular Melanoma of the Glans Penis

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

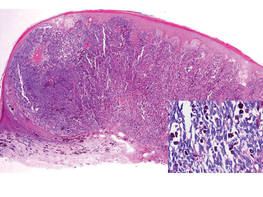

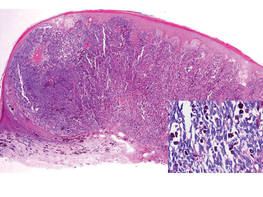

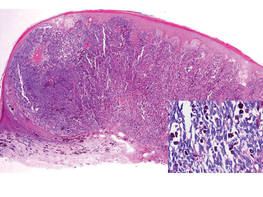

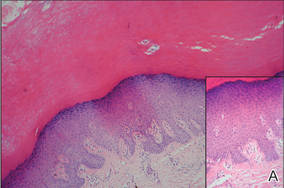

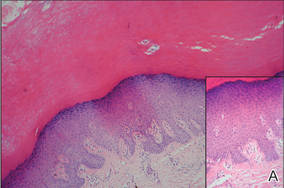

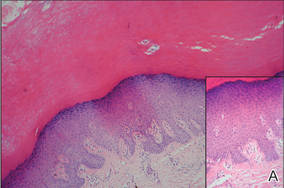

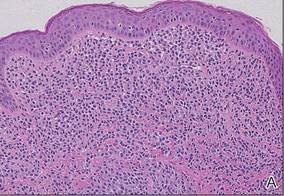

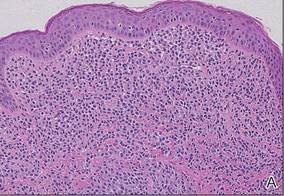

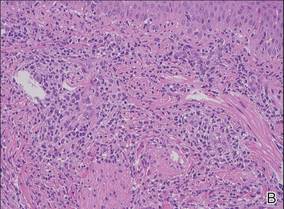

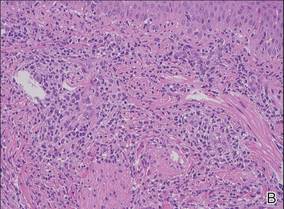

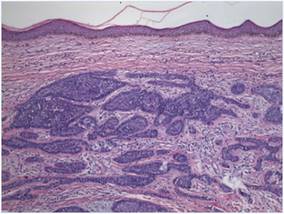

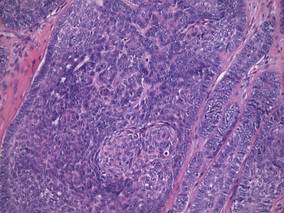

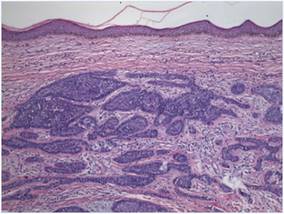

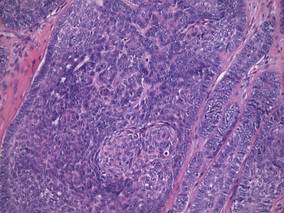

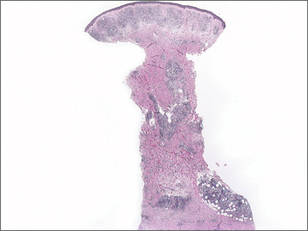

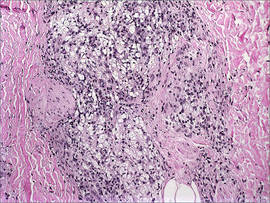

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

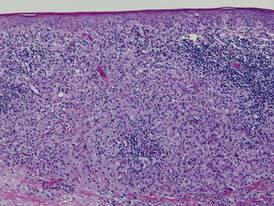

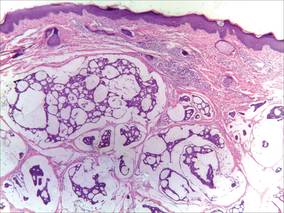

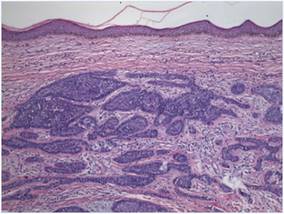

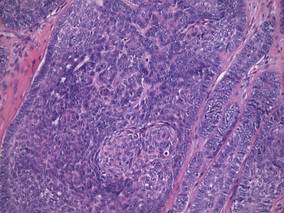

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

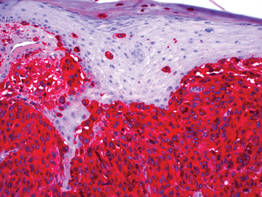

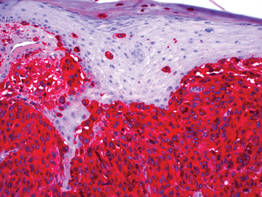

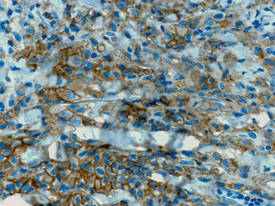

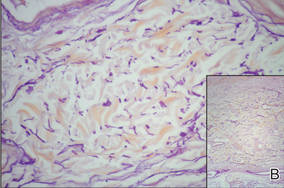

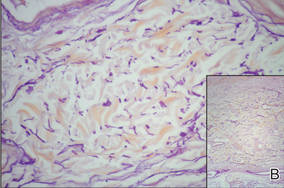

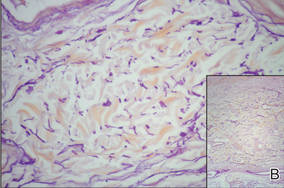

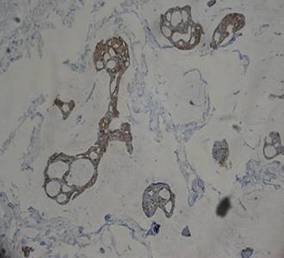

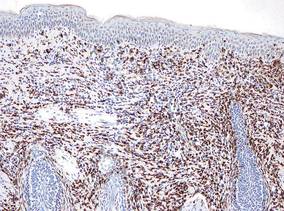

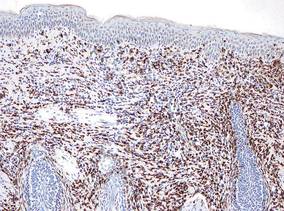

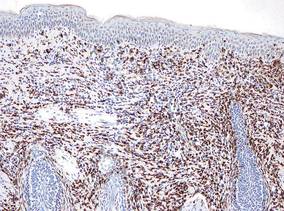

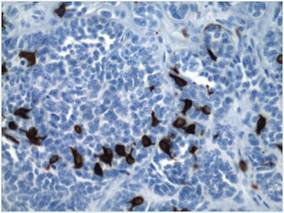

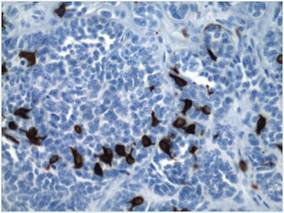

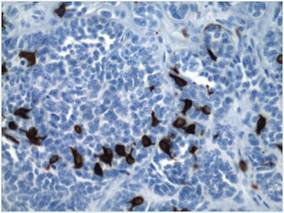

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

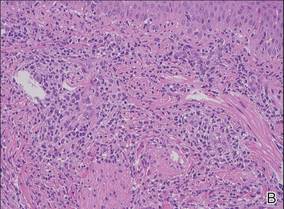

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

To the Editor:

Primary malignant melanoma (PMM) of the penis is rare, comprising 1% of melanomas overall and less than 4% of malignancies in the male genitourinary tract.1 However, regression of PMM is not rare. Melanoma is 6 times more likely to undergo regression compared to other malignancies.2 Approximately 10% to 35% of cutaneous PMMs undergo partial regression, but only 42 cases of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs have been reported,3,4 which may be due to underreporting of completely regressed cutaneous PMMs, as they often are clinically inconspicuous. Additionally, completely regressed cutaneous PMMs may be incorrectly reported as metastatic melanoma of unknown primary.5 Clinical characteristics of regression include pink coloration and a lightening or whitening of baseline lesional color. Dermatoscopic features of regression include white areas, blue areas, or vascular structures that translate microscopically to dermal fibrosis, melanophages, and telangiectases.5 We report a case of complete clinical regression of a nodular, mucosal, penile PMM with no evidence of metastatic disease.

An 86-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging, pigmented lesion on the glans penis of 2 years’ duration. His medical history was notable for retinal detachment, macular degeneration, lumbar stenosis, and seizures postneurosurgery for a subdural hematoma. Physical examination revealed a healthy man with a mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis (Figure 1). No other similar skin lesions or lymphadenopathy were detectable. A lesional deep shave biopsy obtained at presentation demonstrated a nodular-type malignant melanoma with a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm (Figure 2).

|

| Figure 1. Mottled, black-brown, macular, and nodular lesion with irregular margins and irregular shape on the glans penis. |

|

| Figure 2. Histologic section showed a nodular melanocytic proliferation with a dense sheetlike collection of melanocytes, predominantly in the dermis (H&E, original magnification ×20). Prominent cytologic atypia and multiple mitotic figures were consistent with melanoma (inset)(H&E, original magnification ×400). |

|

| Figure 3. High-power view of HMB-45 stain showed strong and diffuse staining, including several pagetoid intraepidermal melanocytes (original magnification ×200). |

|

| Figure 4. Skin examination 8 years following the initial primary malignant melanoma diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent or metastatic melanoma and almost complete loss of pigmentation at the prior melanoma site. |

Histologic examination showed nodular nests of malignant melanocytes that were dispersed along the dermal-epidermal junction and coalesced into sheets within the dermis. Numerous dermal mitoses were present. The tumor was strongly and diffusely positive with Melan-A and HMB-45, which also highlighted scattered pagetoid intraepidermal cells (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of PMM of the mucocutaneous glans penis. The tumor was nonulcerated and invaded to a Breslow thickness of approximately 3.5 mm, corresponding to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IIA (T3aN0M0) with an expected 5-year survival rate of 79%.6

He was referred to the urology department and was offered cystoscopy, urethrography, and phallectomy, which he refused. He also refused a trial of imiquimod. Computed tomography (CT) scans of his brain, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative for metastatic disease. Following the initial melanoma diagnosis, he had yearly dermatologic evaluations consisting of total-body skin and lymph node (LN) examinations. At 87 years of age (1 year following the initial diagnosis), the melanoma became dramatically smaller. At 88 years of age (2 years after diagnosis), the melanoma had near-complete clinical resolution. At 89 years of age, the patient reported asymmetric hearing loss. A cranial magnetic resonance imaging study showed no evidence of metastases.

At 92 years of age (6 years after the initial diagnosis), the patient reported bilateral leg pain. A CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no evidence of metastasis. He also reported abdominal pain. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed an ileocecal mass. Biopsy of the ileocecal mass showed moderately differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma and no evidence of metastatic melanoma. The adenocarcinoma was resected and he continues to do well. Skin and LN examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis showed no clinical evidence of recurrent penile mucosal melanoma or metastatic melanoma (Figure 4). The PMM appeared to have clinically regressed spontaneously. He refused repeat skin biopsy and additional imaging studies.

The criteria for complete melanoma regression were initially described in 19657 and revised in 2005.2 Although our patient demonstrated complete clinical regression of his PMM, he did not meet the revised criteria for complete regression because there was no histopathologic confirmation of regression or of the absence of melanoma as well as no lymphatic involvement. It is extremely difficult to quantify the percentage of PMMs that completely regress. A case of a completely regressed untreated PMM with no metastatic disease 4 years after diagnosis has been reported. This case involved a nonulcerated melanoma with a Breslow thickness of 0.7 mm (American Joint Committee on Cancer stage IA).4 The prognosis of penile mucosal PMM is comparable to that of cutaneous PMM with a similar Breslow thickness.1

The prognostic significance of melanoma regression is controversial. Regression may be mediated by host immunity, apoptosis, and/or antiangiogenesis. The lymphocytic infiltrate in regressive melanomas consists of cytotoxic T cells with selective antitumor activity, which induces HLA class I–restricted melanoma lysis.8 Lymph node migration may result in T-lymphocyte priming and induction of antitumor immunity.9 Therefore, regression may indicate risk for sentinel LN metastasis.

It is possible that complete regression of melanoma does not truly exist, and late recurrence due to cancer dormancy is inevitable. Late recurrence is defined as first metastasis 10 years after complete removal of the PMM.10 Our patient has only been followed for 8 years, so this possibility cannot be entirely excluded.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.

1. van Geel AN, den Bakker MA, Kirkels W, et al. Prognosis of primary mucosal penile melanoma: a series of 19 Dutch patients and 47 patients from the literature. Urology. 2007;70:143-147.

2. High WA, Stewart D, Wilbers CR, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with nodal and/or visceral metastases: a report of 5 cases and assessment of the literature and diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:89-100.

3. Emanuel PO, Mannion M, Phelps RG. Complete regression of primary malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:178-181.

4. Muniesa C, Ferreres JR, Moreno A, et al. Completely regressed primary cutaneous malignant melanoma with metastases [published online ahead of print June 23, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:327-328.

5. Bories N, Dalle S, Debarbieux S, et al. Dermoscopy of fully regressive cutaneous melanoma [published online ahead of print March 13, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1224-1229.

6. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

7. Smith JL Jr, Stehlin JS Jr. Spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanomas with regional metastasis. Cancer. 1965;18:1399-1415.

8. Bottger D, Dowden RV, Kay PP. Complete spontaneous regression of cutaneous primary malignant melanoma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:548-553.

9. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1989;15:257-265.

10. Hansel G, Schönlebe J, Haroske G, et al. Late recurrence (10 years or more) of malignant melanoma in south-east Germany (Saxony). a single-centre analysis of 1881 patients with a follow-up of 10 years or more [published online ahead of print January 11, 2010]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:833-836.

Adult-Type Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Minimal Treatment for Maximal Results

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

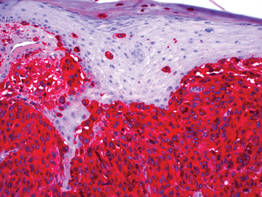

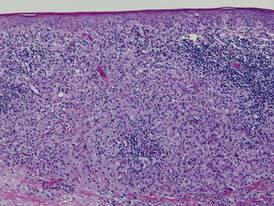

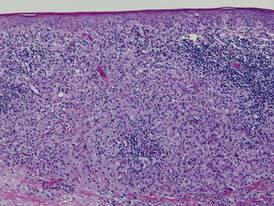

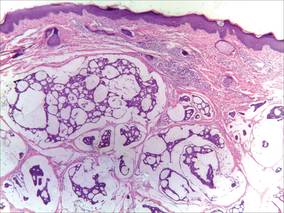

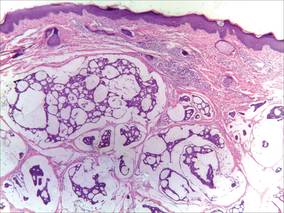

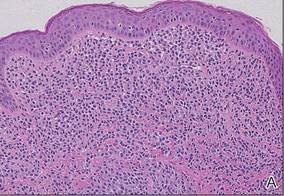

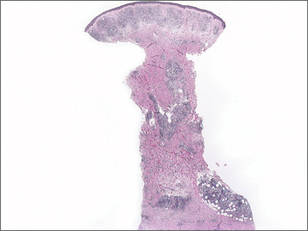

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

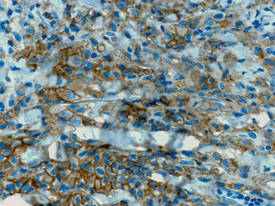

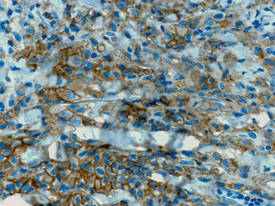

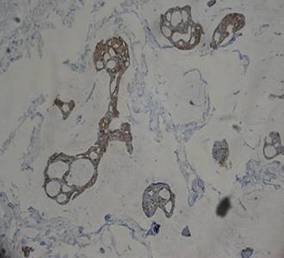

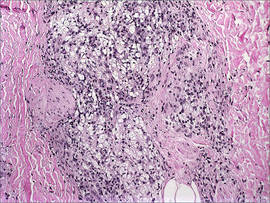

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

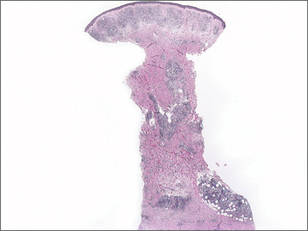

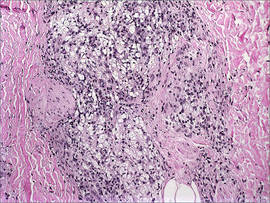

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man presented with erythematous circular skin papules that were widely scattered over the trunk. He denied recent contact with ill individuals and denied any systemic symptoms indicating internal involvement or malignancy leading to possible paraneoplastic presentation. Physical examination showed erythematous, circular, slightly elevated plaques of varying sizes scattered over the trunk (Figure 1) and right axilla.

|

| Figure 1. Nontender, erythematous, brown nodules scattered over the trunk. |

|

| Figure 2. Light microscopy revealed Langerhans cells filling the superficial dermis, abutting the epidermis, and extending into the deep dermis with surrounding inflammatory infiltrates (CD1a, original magnification ×100). |

|

| Figure 3. Langerhans cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (original magnification ×400). |

Biopsies of lesions were taken and stained with immunoperoxidase. On light microscopy there was a reticular and papillary dermal dense infiltrate of cells with indented nuclei (Figure 2). At higher magnification, cells appeared strongly positive for CD1a (Figure 3) and S-100 protein, which was histologically consistent with adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis (ALCH).

Computed tomography of the head, chest, abdomen, and pelvis were ordered to rule out spread of ALCH to other organ sites. Results were clear of evidence of systemic spread. Additionally, a complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range.

He was started on topical tacrolimus; however, most of the lesions resolved on their own. As a result, tacrolimus was discontinued due to its propensity to cause skin irritation and lack of change in disease progression. At 3-month follow-up, he was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for minor outbreaks. After 2 years, he was completely clear of all skin signs of ALCH.

Adult-type Langerhans cell histiocytosis is characterized as a group of disorders associated with abnormal spread and proliferation of dendritic cells of the epidermis. The disease primarily affects children aged 1 to 4 years. It is estimated that only 1 to 2 cases of ALCH per million occur.1 The pathophysiology of ALCH is unknown; it is speculated that it may be associated with a reactive inflammatory process triggered by proliferation of Langerhans-type dendritic cells. It is possible that the release of multiple cytokines by dendritic cells and T cells in ALCH lesions leads to erythematous eruptions and can contribute to spontaneous remission of the disorder.2 Various cases of ALCH have reported high serum levels of IL-17 and IL-10 proinflammatory cytokines, supporting the theory of an inflammatory etiology of ALCH.3

Comparative genomic hybridization with loss of heterozygosity of pulmonary lesions has provided further evidence to suggest that chromosomal aberrations also may contribute to the pathophysiology of ALCH.4 One study evaluated 14 cases of pulmonary ALCH for loss of heterozygosity and found allelic loss of 1p, 1q, 3p, 5p, 17p, and 22q.5 In addition, allelic loss of 1 or more tumor suppressor genes was identified in 19 of 24 specimens, suggesting a neoplastic type of pathology through uncontrolled cellular proliferation.6

Lesions of ALCH can be broad but typically present as red-brown maculopapular lesions with petechiae that erupt over the trunk, axilla, and perivulvar or retroauricular regions.7 The papules may unify to form an erythematous, weeping, or crusted eruption that appears similar to seborrheic dermatitis. Typically the lesions remit on their own; however, lesions can recur with the same or decreased severity as the primary eruption. Complications have been noted with lesions, particularly secondary infection and ulceration.7

Systemic involvement has been noted in adults, particularly in the lungs. Patients typically present with chronic cough, dyspnea, and chest pain with evidence of a solitary nodular lesion on radiologic testing. In addition, bone involvement has been noted as eosinophilic granulomas that can produce osteolytic lesions that lead to spontaneous fractures. Use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, as opposed to just observation, is warranted in cases of systemic involvement, according to the National Cancer Institute.7

Exact treatment modalities have not yet been elucidated due to the ambiguity of pathogenesis. In addition, ALCH is known to remit and relapse in patients, which increases the difficulty in evaluating the efficacy of particular treatments. Trials conducted by the Histiocyte Society have shown that treatment regimens should be tailored to disease severity. Epidermal involvement of ALCH typically responds to corticosteroid creams, whereas patients with systemic involvement respond well to strong chemotherapeutic agents such as vincristine and prednisone with mercaptopurine.8 However, as demonstrated in our case, lesions may remit on their own and use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents may lead to further detriment without treating disease progression.

Because of a low prevalence among adults, ALCH is difficult to recognize and diagnose, and the uncertainty of the pathogenesis of ALCH limits treatment alternatives. Further study into proper treatment modalities is warranted given that the remitting and relapsing course of the disease and cosmetic quandaries are detrimental to patient well-being. Our case illustrates that it is appropriate to simply monitor lesions for cases limited to cutaneous involvement. Systemic agents may be used when there are signs of organ involvement outside the skin, but providers must proceed to do so with caution.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.

1. Baumgartner I, von Hochstetter A, Baumert B, et al. Langerhans’-cell histiocytosis in adults. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:9-14.

2. Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1999;94:4195-4201.

3. da Costa CE, Szuhai K, van Eijk R, et al. No genomic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis as assessed by diverse molecular technologies. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:239-249.

4. Murakami I, Gogusev J, Fournet JC, et al. Detection of molecular cytogenetic aberrations in Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:555-560.

5. Dacic S, Trusky C, Bakker A, et al. Genotypic analysis of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1345-1349.

6. Chikwava KR, Hunt JL, Mantha GS, et al. Analysis of loss of heterozygosity in single-system and multisystem Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007;10:18-24.

7. Langerhans cell histiocytosis treatment. National Cancer Institute Web site. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/lchistio/HealthProfessional/page5. Updated June 4, 2014. Accessed August 27, 2014.

8. Weitzman S, Wayne AS, Arceci R, et al. Nucleoside analogues in the therapy of Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a survey of members of the histiocyte society and review of the literature. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:476-481.

Successful Treatment of Schnitzler Syndrome With Canakinumab

To the Editor:

Schnitzler syndrome occurs with a triad of chronic urticaria, recurring fevers, and monoclonal gammopathy. It was recognized as a clinical entity in 1972; now nearly 200 patients are reported in the medical literature.1-3 Flulike symptoms, arthralgia, bone pain, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly also are clinical findings.4,5 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) often is markedly elevated, as are other acute phase reactants. Leukocytosis with neutrophilia and IgM and IgG monoclonal gammopathies have been described.4

Schnitzler syndrome shares many clinical characteristics with a subset of autoinflammatory disorders referred to as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), which includes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wellssyndrome. These syndromes are associated with mutations in the cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 gene, CIAS1, which encodes the NALP3 inflammasome, leading to overproduction of IL-1β.5 A gain-of-function mutation in CIAS1 has been described in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome.6

Treatment of urticaria and constitutional symptoms associated with Schnitzler syndrome is challenging. Antihistamines are ineffective, though high-dose systemic glucocorticosteroids control most of the clinical manifestations. Methotrexate sodium, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists are utilized as glucocorticosteroid-sparing agents. Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor monoclonal antibody that is approved for use in CAPS, has been reported to induce complete resolution of Schnitzler syndrome when administered daily; however, it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this disorder.7 Canakinumab, an IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is dosed every 8 weeks, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2009 for the treatment of CAPS. Given the similar clinical characteristics and genetic mutations found in CAPS and Schnitzler syndrome, canakinumab may be an effective treatment of both disorders. We report successful treatment with this monoclonal antibody in 2 patients with Schnitzler syndrome.

A 63-year-old man reported having night sweats and fatigue but had no arthralgia or arthritis. He had a 1-year history of severe urticaria and recurrent fevers (temperature, up to 38.4°C) and he also had type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and celiac disease. Physical examination revealed an elevated temperature (38.4°C) and generalized urticaria but no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, adenopathy, or arthritis. Leukocytosis was revealed (white blood cell count, 12,400/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000/μL]) with neutrophilia (88.5% [reference range, 56%]), elevated ESR (81 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and IgM κ monoclonal gammopathy (0.37 g/L [reference range, 0.4–2.3 g/L]). Clinical examination as well as laboratory and imaging studies did not show evidence of malignancy or autoimmune disease. A skin biopsy identified neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis. Prednisone 20 mg daily controlled the urticaria and fever, but symptoms recurred within days of glucocorticosteroid withdrawal.

A 47-year-old woman presented with a 7-year history of severe urticaria, fever (temperature, 38.9°C), myalgia, and arthralgia. She had a medical history of allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pain syndrome, and depression. Physical examination revealed generalized urticaria with cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy 1 to 2 cm in size but no hepatosplenomegaly or arthritis. Prior evaluations for fever of unknown origin as well as autoimmune and malignant disorders were negative. Skin biopsies reported neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis, and a lymph node biopsy from the left axilla revealed neutrophilic inflammation. A white blood cell count of 17,800/μL with 61.6% neutrophils, elevated C-reactive protein (153.4 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) and ESR (90 mm/h), and an IgG λ monoclonal gammopathy were present. She was previously treated with etanercept, methotrexate sodium, golimumab, and adalimumab, with only a partial response. For more than 5 years, prednisone 20 to 50 mg daily was necessary to control her symptoms. Cyclosporine 200 mg twice daily was added as a corticosteroid-sparing drug with partial response.

Both patients were diagnosed with Schnitzler syndrome and were started on canakinumab 150 mg administered subcutaneously in the upper arm every 8 weeks. Resolution of the urticaria and fevers occurred within 2 weeks, and all other medications for the treatment of Schnitzler syndrome were withdrawn without recurrence of symptoms after 3 years. The neutrophil count and acute phase reactants returned within reference range in each patient, but the monoclonal gammopathies remained unchanged. Patient 2 noted worsening of arthralgia after initiation of canakinumab, but long-term corticosteroid withdrawal was considered the cause. Patient 1 has been able to increase the interval of dosing to every 3 to 4 months without recurrence of symptoms. Patient 2 has not tolerated similar changes in dosing interval.

Canakinumab given at 8-week intervals was a safe and effective treatment of Schnitzler syndrome in this open trial of 2 patients. Anakinra also induces remission, but daily dosing is required. Cost may be a notable factor in the choice of therapy, as canakinumab costs substantially more per year than anakinra. Further investigation is required to determine if treatment with canakinumab will result in long-term remission and if less-frequent dosing will provide continued efficacy.

1. Schnitzler L. Lésions urticariennes chroniques permanentes (érythème pétaloïde?). Cas cliniques. nº 46 B. Journee Dermatologique d’Angers. October 1972.

2. Schnitzler L, Schubert B, Boasson M, et al. Urticaire chronique, lésions osseuses, macroglobulinémie IgM: maladie de Waldenstrӧm. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1974;81:363.

3. Simon A, Asli B, Braun-Falco M, et al. Schnitzler’s syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Allergy. 2013;68:562-568.

4. de Koning HD, Bodar EJ, van der Meer JW, et al. Schnitzler syndrome: beyond the case reports: review and follow-up of 94 patients with an emphasis on prognosis and treatment [published online ahead of print June 21, 2007]. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:137-148.

5. Lipsker D, Veran Y, Grunenberger F, et al. The Schnitzler syndrome. four new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:37-44.

6. Loock J, Lamprecht P, Timmann C, et al. Genetic predisposition (NLRP3 V198M mutation) for IL-1-mediated inflammation in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:500-502.

7. Ryan JG, de Koning HD, Beck LA, et al. IL-1 blockade in Schnitzler syndrome: ex vivo findings correlate with clinical remission [published online ahead of print October 22, 2007]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:260-262.

To the Editor:

Schnitzler syndrome occurs with a triad of chronic urticaria, recurring fevers, and monoclonal gammopathy. It was recognized as a clinical entity in 1972; now nearly 200 patients are reported in the medical literature.1-3 Flulike symptoms, arthralgia, bone pain, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly also are clinical findings.4,5 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) often is markedly elevated, as are other acute phase reactants. Leukocytosis with neutrophilia and IgM and IgG monoclonal gammopathies have been described.4

Schnitzler syndrome shares many clinical characteristics with a subset of autoinflammatory disorders referred to as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), which includes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wellssyndrome. These syndromes are associated with mutations in the cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 gene, CIAS1, which encodes the NALP3 inflammasome, leading to overproduction of IL-1β.5 A gain-of-function mutation in CIAS1 has been described in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome.6

Treatment of urticaria and constitutional symptoms associated with Schnitzler syndrome is challenging. Antihistamines are ineffective, though high-dose systemic glucocorticosteroids control most of the clinical manifestations. Methotrexate sodium, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists are utilized as glucocorticosteroid-sparing agents. Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor monoclonal antibody that is approved for use in CAPS, has been reported to induce complete resolution of Schnitzler syndrome when administered daily; however, it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this disorder.7 Canakinumab, an IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is dosed every 8 weeks, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2009 for the treatment of CAPS. Given the similar clinical characteristics and genetic mutations found in CAPS and Schnitzler syndrome, canakinumab may be an effective treatment of both disorders. We report successful treatment with this monoclonal antibody in 2 patients with Schnitzler syndrome.

A 63-year-old man reported having night sweats and fatigue but had no arthralgia or arthritis. He had a 1-year history of severe urticaria and recurrent fevers (temperature, up to 38.4°C) and he also had type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and celiac disease. Physical examination revealed an elevated temperature (38.4°C) and generalized urticaria but no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, adenopathy, or arthritis. Leukocytosis was revealed (white blood cell count, 12,400/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000/μL]) with neutrophilia (88.5% [reference range, 56%]), elevated ESR (81 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and IgM κ monoclonal gammopathy (0.37 g/L [reference range, 0.4–2.3 g/L]). Clinical examination as well as laboratory and imaging studies did not show evidence of malignancy or autoimmune disease. A skin biopsy identified neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis. Prednisone 20 mg daily controlled the urticaria and fever, but symptoms recurred within days of glucocorticosteroid withdrawal.

A 47-year-old woman presented with a 7-year history of severe urticaria, fever (temperature, 38.9°C), myalgia, and arthralgia. She had a medical history of allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pain syndrome, and depression. Physical examination revealed generalized urticaria with cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy 1 to 2 cm in size but no hepatosplenomegaly or arthritis. Prior evaluations for fever of unknown origin as well as autoimmune and malignant disorders were negative. Skin biopsies reported neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis, and a lymph node biopsy from the left axilla revealed neutrophilic inflammation. A white blood cell count of 17,800/μL with 61.6% neutrophils, elevated C-reactive protein (153.4 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) and ESR (90 mm/h), and an IgG λ monoclonal gammopathy were present. She was previously treated with etanercept, methotrexate sodium, golimumab, and adalimumab, with only a partial response. For more than 5 years, prednisone 20 to 50 mg daily was necessary to control her symptoms. Cyclosporine 200 mg twice daily was added as a corticosteroid-sparing drug with partial response.

Both patients were diagnosed with Schnitzler syndrome and were started on canakinumab 150 mg administered subcutaneously in the upper arm every 8 weeks. Resolution of the urticaria and fevers occurred within 2 weeks, and all other medications for the treatment of Schnitzler syndrome were withdrawn without recurrence of symptoms after 3 years. The neutrophil count and acute phase reactants returned within reference range in each patient, but the monoclonal gammopathies remained unchanged. Patient 2 noted worsening of arthralgia after initiation of canakinumab, but long-term corticosteroid withdrawal was considered the cause. Patient 1 has been able to increase the interval of dosing to every 3 to 4 months without recurrence of symptoms. Patient 2 has not tolerated similar changes in dosing interval.

Canakinumab given at 8-week intervals was a safe and effective treatment of Schnitzler syndrome in this open trial of 2 patients. Anakinra also induces remission, but daily dosing is required. Cost may be a notable factor in the choice of therapy, as canakinumab costs substantially more per year than anakinra. Further investigation is required to determine if treatment with canakinumab will result in long-term remission and if less-frequent dosing will provide continued efficacy.

To the Editor:

Schnitzler syndrome occurs with a triad of chronic urticaria, recurring fevers, and monoclonal gammopathy. It was recognized as a clinical entity in 1972; now nearly 200 patients are reported in the medical literature.1-3 Flulike symptoms, arthralgia, bone pain, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly also are clinical findings.4,5 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) often is markedly elevated, as are other acute phase reactants. Leukocytosis with neutrophilia and IgM and IgG monoclonal gammopathies have been described.4

Schnitzler syndrome shares many clinical characteristics with a subset of autoinflammatory disorders referred to as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), which includes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wellssyndrome. These syndromes are associated with mutations in the cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome 1 gene, CIAS1, which encodes the NALP3 inflammasome, leading to overproduction of IL-1β.5 A gain-of-function mutation in CIAS1 has been described in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome.6

Treatment of urticaria and constitutional symptoms associated with Schnitzler syndrome is challenging. Antihistamines are ineffective, though high-dose systemic glucocorticosteroids control most of the clinical manifestations. Methotrexate sodium, cyclosporine, and tumor necrosis factor antagonists are utilized as glucocorticosteroid-sparing agents. Anakinra, an IL-1 receptor monoclonal antibody that is approved for use in CAPS, has been reported to induce complete resolution of Schnitzler syndrome when administered daily; however, it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this disorder.7 Canakinumab, an IL-1β monoclonal antibody that is dosed every 8 weeks, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2009 for the treatment of CAPS. Given the similar clinical characteristics and genetic mutations found in CAPS and Schnitzler syndrome, canakinumab may be an effective treatment of both disorders. We report successful treatment with this monoclonal antibody in 2 patients with Schnitzler syndrome.

A 63-year-old man reported having night sweats and fatigue but had no arthralgia or arthritis. He had a 1-year history of severe urticaria and recurrent fevers (temperature, up to 38.4°C) and he also had type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, and celiac disease. Physical examination revealed an elevated temperature (38.4°C) and generalized urticaria but no evidence of hepatosplenomegaly, adenopathy, or arthritis. Leukocytosis was revealed (white blood cell count, 12,400/μL [reference range, 4500–11,000/μL]) with neutrophilia (88.5% [reference range, 56%]), elevated ESR (81 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]), and IgM κ monoclonal gammopathy (0.37 g/L [reference range, 0.4–2.3 g/L]). Clinical examination as well as laboratory and imaging studies did not show evidence of malignancy or autoimmune disease. A skin biopsy identified neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis. Prednisone 20 mg daily controlled the urticaria and fever, but symptoms recurred within days of glucocorticosteroid withdrawal.

A 47-year-old woman presented with a 7-year history of severe urticaria, fever (temperature, 38.9°C), myalgia, and arthralgia. She had a medical history of allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, chronic pain syndrome, and depression. Physical examination revealed generalized urticaria with cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy 1 to 2 cm in size but no hepatosplenomegaly or arthritis. Prior evaluations for fever of unknown origin as well as autoimmune and malignant disorders were negative. Skin biopsies reported neutrophilic urticaria without vasculitis, and a lymph node biopsy from the left axilla revealed neutrophilic inflammation. A white blood cell count of 17,800/μL with 61.6% neutrophils, elevated C-reactive protein (153.4 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) and ESR (90 mm/h), and an IgG λ monoclonal gammopathy were present. She was previously treated with etanercept, methotrexate sodium, golimumab, and adalimumab, with only a partial response. For more than 5 years, prednisone 20 to 50 mg daily was necessary to control her symptoms. Cyclosporine 200 mg twice daily was added as a corticosteroid-sparing drug with partial response.

Both patients were diagnosed with Schnitzler syndrome and were started on canakinumab 150 mg administered subcutaneously in the upper arm every 8 weeks. Resolution of the urticaria and fevers occurred within 2 weeks, and all other medications for the treatment of Schnitzler syndrome were withdrawn without recurrence of symptoms after 3 years. The neutrophil count and acute phase reactants returned within reference range in each patient, but the monoclonal gammopathies remained unchanged. Patient 2 noted worsening of arthralgia after initiation of canakinumab, but long-term corticosteroid withdrawal was considered the cause. Patient 1 has been able to increase the interval of dosing to every 3 to 4 months without recurrence of symptoms. Patient 2 has not tolerated similar changes in dosing interval.

Canakinumab given at 8-week intervals was a safe and effective treatment of Schnitzler syndrome in this open trial of 2 patients. Anakinra also induces remission, but daily dosing is required. Cost may be a notable factor in the choice of therapy, as canakinumab costs substantially more per year than anakinra. Further investigation is required to determine if treatment with canakinumab will result in long-term remission and if less-frequent dosing will provide continued efficacy.

1. Schnitzler L. Lésions urticariennes chroniques permanentes (érythème pétaloïde?). Cas cliniques. nº 46 B. Journee Dermatologique d’Angers. October 1972.

2. Schnitzler L, Schubert B, Boasson M, et al. Urticaire chronique, lésions osseuses, macroglobulinémie IgM: maladie de Waldenstrӧm. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1974;81:363.

3. Simon A, Asli B, Braun-Falco M, et al. Schnitzler’s syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Allergy. 2013;68:562-568.

4. de Koning HD, Bodar EJ, van der Meer JW, et al. Schnitzler syndrome: beyond the case reports: review and follow-up of 94 patients with an emphasis on prognosis and treatment [published online ahead of print June 21, 2007]. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:137-148.

5. Lipsker D, Veran Y, Grunenberger F, et al. The Schnitzler syndrome. four new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:37-44.

6. Loock J, Lamprecht P, Timmann C, et al. Genetic predisposition (NLRP3 V198M mutation) for IL-1-mediated inflammation in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:500-502.

7. Ryan JG, de Koning HD, Beck LA, et al. IL-1 blockade in Schnitzler syndrome: ex vivo findings correlate with clinical remission [published online ahead of print October 22, 2007]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:260-262.

1. Schnitzler L. Lésions urticariennes chroniques permanentes (érythème pétaloïde?). Cas cliniques. nº 46 B. Journee Dermatologique d’Angers. October 1972.

2. Schnitzler L, Schubert B, Boasson M, et al. Urticaire chronique, lésions osseuses, macroglobulinémie IgM: maladie de Waldenstrӧm. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1974;81:363.

3. Simon A, Asli B, Braun-Falco M, et al. Schnitzler’s syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Allergy. 2013;68:562-568.

4. de Koning HD, Bodar EJ, van der Meer JW, et al. Schnitzler syndrome: beyond the case reports: review and follow-up of 94 patients with an emphasis on prognosis and treatment [published online ahead of print June 21, 2007]. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;37:137-148.

5. Lipsker D, Veran Y, Grunenberger F, et al. The Schnitzler syndrome. four new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:37-44.

6. Loock J, Lamprecht P, Timmann C, et al. Genetic predisposition (NLRP3 V198M mutation) for IL-1-mediated inflammation in a patient with Schnitzler syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:500-502.

7. Ryan JG, de Koning HD, Beck LA, et al. IL-1 blockade in Schnitzler syndrome: ex vivo findings correlate with clinical remission [published online ahead of print October 22, 2007]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:260-262.

Fungal Melanonychia Caused by Trichophyton rubrum and the Value of Dermoscopy

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.

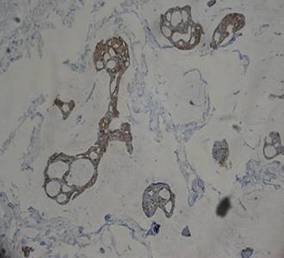

A 39-year-old man visited the dermatology clinic with a concern for melanoma because of blackish pigmentation of the toenails of 1 month’s duration. He denied history of trauma and was not taking any medications. On physical examination the second and third toenails revealed a 2-mm longitudinal band of black pigment on the lateral side; the fifth toenail showed diffuse black pigment (Figure 1A). The nail plates were thickened. Dermoscopy revealed prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, a homogeneous brown-black band with wide yellow streaks that were wider in the distal ends, and some focal reddish hue. No visible melanin inclusions were observed (Figure 2). These findings were suggestive of fungal infection. Cultures from the diseased nail grew a fungus identified as Trichophyton rubrum. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months. Clinical cure with disappearance of pigment was obtained at 5-month follow-up (Figure 1B).

|

|

| Figure 1. Blackish discoloration of the right second, third, and fifth toenails (A). Resolution of pigmentation and subungual hyperkeratosis was achieved at 5-month follow-up after treatment (B). |

|

|

| Figure 2. Top view (A) and front view (B) of a homogeneous brown-black band with subungual hyperkeratosis and wide intervening yellow streaks. Each ruler mark denotes 1 mm. |

Our patient illustrates the value of dermoscopy in evaluating melanonychia. The pigmentation of adult-onset melanonychia involving multiple fingers can be divided into nonmelanocytic or melanocytic origin. Causes of the former include subungual hematoma, fungal or bacterial infection, and exogenous pigmentation. The nonmelanocytic pigment often is homogeneously distributed without melanin inclusions under the dermoscope.2

On the contrary, melanin inclusions can be detected as fine granules in pigmentation of melanocytic origin, either from focal melanocytic activation or melanocyte proliferation. Causes of focal melanocytic activation include ethnic-type nail hyperpigmentation; inflammatory nail diseases; or drug-, radiation-, and friction-induced hyperpigmentation. The characteristic dermoscopic features are thin longitudinal gray lines with regular thickness and spacing in a grayish background.1-3

Melanocyte proliferation can result in a nevus or melanoma of the nail apparatus. Both share dermoscopic features of brown-black longitudinal lines in a brown background. However, the longitudinal lines in melanoma are irregular in coloration, spacing, thickness, and parallelism, in contrast with the regular pattern of a nevus.1-4 Although patients often are concerned about melanoma, involvement of multiple fingers at the same time is less likely.

In our patient, the homogeneous deep brown color without melanin inclusions favored a nonmel-anocytic origin. The distally wider pigmentation suggested fungal infection because most ungual infections extend from the distal to the proximal part of the nail.5,6 The focal reddish hue may be related with traumatic hemorrhage from subungual hyperkeratosis.

Cases of fungal melanonychia are being reported at an increasing rate. Some fungal strains are capable of synthesizing melanin, which is associated with virulence and acts as a fungal armor against toxic insults.5 In T rubrum, the melanoid variant, the diffusible black pigment infiltrates the nail plate and attributes to the black nail clinically.4 The most frequently isolated fungi in fungal melanonychia are T rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum6; however, Candida species,7,8 dematiaceous fungus,9 and other dermatophytes such as Trichophyton soudanense10 have been reported to be the cause.5

Our patient presented with fungal melanonychia due to T rubrum with dermoscopic features. The prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, distally wider homogeneous brown-black pigmented band, and wide yellow streaks with focal reddish hue all suggested fungal melanonychia. The diagnosis was further confirmed by a good response to antifungal agents.

1. Ronger S, Touzet S, Ligeron C, et al. Dermoscopic examination of nail pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1327-1333.

2. Braun RP, Baran R, Le Gal FA, et al. Diagnosis and management of nail pigmentations [published online ahead of print February 22, 2007]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:835-847.

3. Koga H, Saida T, Uhara H. Key point in dermoscopic differentiation between early nail apparatus melanoma and benign longitudinal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2011;38:45-52.

4. Phan A, Dalle S, Touzet S, et al. Dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma in a large series of 110 cases in a white population [published online ahead of print November 18, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:765-771.

5. Finch J, Arenas R, Baran R. Fungal melanonychia [published online ahead of print January 17, 2012]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:830-841.

6. Lee SW, Kim YC, Kim DK, et al. Fungal melanonychia. J Dermatol. 2004;31:904-909.

7. Parlak AH, Goksugur N, Karabay O. A case of melanonychia due to Candida albicans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:398-400.

8. Gautret P, Rodier MH, Kauffmann-Lacroix C, et al. Case report and review. onychomycosis due to Candida parapsilosis. Mycoses. 2000;43:433-435.

9. Barua P, Barua S, Borkakoty B, et al. Onychomycosis by Scytalidium dimidiatum in green tea leaf pluckers: report of two cases [published online ahead of print July 20, 2007]. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:193-195.

10. Ricci C, Monod M, Baudraz-Rosselet F. Onychomycosis due to Trichophyton soudanense in Switzerland. Dermatology. 1998;197:297-298.

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.

A 39-year-old man visited the dermatology clinic with a concern for melanoma because of blackish pigmentation of the toenails of 1 month’s duration. He denied history of trauma and was not taking any medications. On physical examination the second and third toenails revealed a 2-mm longitudinal band of black pigment on the lateral side; the fifth toenail showed diffuse black pigment (Figure 1A). The nail plates were thickened. Dermoscopy revealed prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, a homogeneous brown-black band with wide yellow streaks that were wider in the distal ends, and some focal reddish hue. No visible melanin inclusions were observed (Figure 2). These findings were suggestive of fungal infection. Cultures from the diseased nail grew a fungus identified as Trichophyton rubrum. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200 mg daily for 3 months. Clinical cure with disappearance of pigment was obtained at 5-month follow-up (Figure 1B).

|

|

| Figure 1. Blackish discoloration of the right second, third, and fifth toenails (A). Resolution of pigmentation and subungual hyperkeratosis was achieved at 5-month follow-up after treatment (B). |

|

|

| Figure 2. Top view (A) and front view (B) of a homogeneous brown-black band with subungual hyperkeratosis and wide intervening yellow streaks. Each ruler mark denotes 1 mm. |

Our patient illustrates the value of dermoscopy in evaluating melanonychia. The pigmentation of adult-onset melanonychia involving multiple fingers can be divided into nonmelanocytic or melanocytic origin. Causes of the former include subungual hematoma, fungal or bacterial infection, and exogenous pigmentation. The nonmelanocytic pigment often is homogeneously distributed without melanin inclusions under the dermoscope.2

On the contrary, melanin inclusions can be detected as fine granules in pigmentation of melanocytic origin, either from focal melanocytic activation or melanocyte proliferation. Causes of focal melanocytic activation include ethnic-type nail hyperpigmentation; inflammatory nail diseases; or drug-, radiation-, and friction-induced hyperpigmentation. The characteristic dermoscopic features are thin longitudinal gray lines with regular thickness and spacing in a grayish background.1-3

Melanocyte proliferation can result in a nevus or melanoma of the nail apparatus. Both share dermoscopic features of brown-black longitudinal lines in a brown background. However, the longitudinal lines in melanoma are irregular in coloration, spacing, thickness, and parallelism, in contrast with the regular pattern of a nevus.1-4 Although patients often are concerned about melanoma, involvement of multiple fingers at the same time is less likely.

In our patient, the homogeneous deep brown color without melanin inclusions favored a nonmel-anocytic origin. The distally wider pigmentation suggested fungal infection because most ungual infections extend from the distal to the proximal part of the nail.5,6 The focal reddish hue may be related with traumatic hemorrhage from subungual hyperkeratosis.

Cases of fungal melanonychia are being reported at an increasing rate. Some fungal strains are capable of synthesizing melanin, which is associated with virulence and acts as a fungal armor against toxic insults.5 In T rubrum, the melanoid variant, the diffusible black pigment infiltrates the nail plate and attributes to the black nail clinically.4 The most frequently isolated fungi in fungal melanonychia are T rubrum and Scytalidium dimidiatum6; however, Candida species,7,8 dematiaceous fungus,9 and other dermatophytes such as Trichophyton soudanense10 have been reported to be the cause.5

Our patient presented with fungal melanonychia due to T rubrum with dermoscopic features. The prominent subungual hyperkeratosis, distally wider homogeneous brown-black pigmented band, and wide yellow streaks with focal reddish hue all suggested fungal melanonychia. The diagnosis was further confirmed by a good response to antifungal agents.

To the Editor:

Longitudinal melanonychia encompasses a broad spectrum of diseases and often is a complex diagnostic problem. Differential diagnoses include ethnic-type nail pigmentation, which is more frequently seen in darker-skinned individuals; drug-induced pigmentation; subungual hemorrhage; fungal or bacterial infection; nevus; and melanoma.1,2 Fungal melan-onychia is an uncommon presentation of onychomycosis. Dermoscopy can assist in the evaluation of nail pigmentation caused by fungi to avoid unnecessary nail biopsies.