User login

Frostbite on the Hand of a Homeless Man

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old homeless man presented to the emergency department after being found wandering in the middle of winter in Detroit, Michigan, with altered mental status. A workup for his mental incapacitation uncovered severe electrolyte disturbances, hyperglycemia, and acute renal failure, as well as both alcohol and drug intoxication. After 1 day of admission the patient reported progressive swelling, blistering, and pain in the right hand. The pain was stabbing in nature, worse with movement, and graded 10 of 10 (1=minimal; 10=severe). His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus with peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol and drug abuse. The patient was not taking any medications for these conditions.

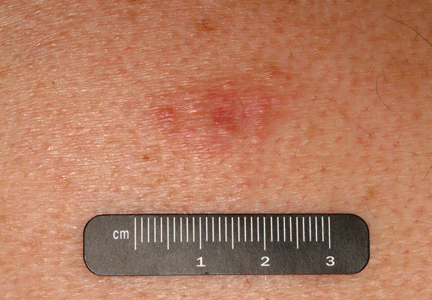

Physical examination revealed 2+ moderate pitting edema in all distal extremities, with increased edema of the dorsal aspect of the right hand. The right hand also demonstrated patchy erythema and was warm to touch. The dorsal aspect of the right ring finger had a dusky tip and was studded with several tense blisters (Figure). Vital signs were stable. Based on the patient’s history and physical examination findings, a diagnosis of frostbite was made. Our treatment process involved several modalities including immersion of the affected site in a warm water bath, surgical debridement of blistered sites, tetanus toxoid, penicillin to prevent infection, and oral ibuprofen for pain management. At 3-day follow-up, the patient’s condition substantially improved with a decreased amount of erythema, edema, and pain. All affected sites were successfully preserved with no evidence of focal, motor, or sensory impairment.

Frostbite is a form of localized tissue injury due to extreme cold that most commonly affects the hands and feet, with the greatest incidence occurring in adults aged 30 to 49 years.1,2 Other sites commonly affected include the ears, nose, cheeks, and penis. Frostbite injuries can be categorized into 4 degrees of severity that correlate with the clinical presentation.1,3 Rewarming the affected site is necessary to properly classify the injury, as the initial appearance may be similar among the different degrees of injury. A first-degree injury classically shows a central white plaque with peripheral erythema and is extremely cold to touch. Second-degree injuries display tense blisters filled with clear or milky fluid surrounded by erythema and edema within the first 24 hours. Third-degree injuries are associated with hemorrhagic blisters. Fourth-degree injuries involve complete tissue loss and necrosis.1 Frostbite injuries also may be classified as superficial or deep; the former affects skin and subcutaneous tissue, while the latter affects bones, joints, and tendons.3,4 The superficial form exhibits clear blisters, whereas hemorrhagic blisters demonstrate deep frostbite.

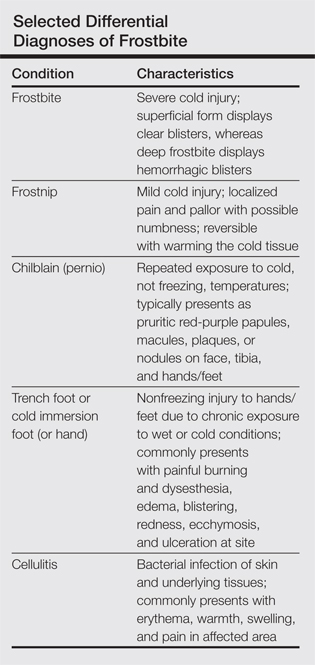

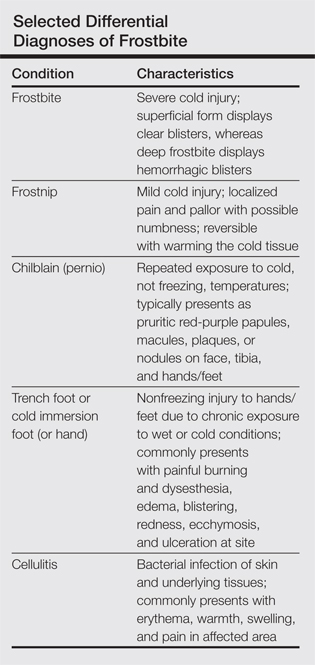

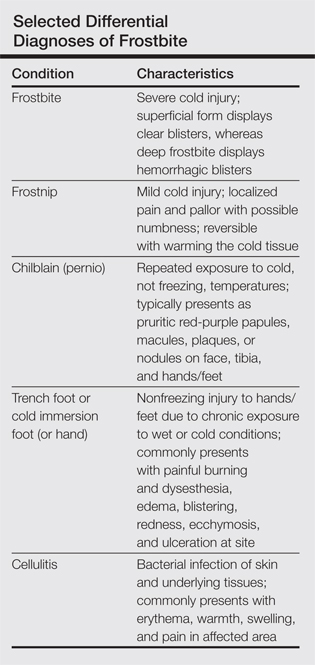

Factors such as the surrounding temperature, length of exposure, and alcohol consumption may exacerbate frostbite injuries.1 Conditions such as atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus, which can cause neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease, also are potential risks. Psychiatric patients also are at risk for frostbite given the propensity for eccentric behavior as well as the homeless due to inadequate clothing or shelter. Diagnosis often can be made based on medical history and physical examination, though techniques such as radiography, angiography, digital plethysmography, Doppler ultrasonography, and bone scintigraphy (technetium-99) also have been utilized to determine severity and prognosis.2 Differential diagnoses of frostbite are listed in the Table.

Frostbite treatment begins with removal of wet clothing and region protection. Rewarming the site should not begin until refreezing is unlikely to occur and involves placing the injured area in water (temperature, 40°C–42°C) for 15 to 30 minutes to minimize tissue loss.1,2 Analgesics, tetanus toxoid, oral ibuprofen, and benzylpenicillin also are indicated, along with daily hydrotherapy.1,2 White blisters should be debrided, while hemorrhagic blisters should be left intact. Amputation and aggressive debridement typically are delayed until complete ischemia occurs and final demarcation is determined, usually over 1 to 3 months.1 Combination therapy allowed for a positive outcome in our patient.

Frostnip is a mild form of cold injury characterized by localized pain, pallor, and possible numbness.3 Warming the cold area restores the function and sensation with no loss of tissue. Chilblain or pernio refers to a localized cold injury that typically presents as pruritic red-purple papules, macules, plaques, or nodules on the face, anterior tibial surface, or dorsum and tips of the hands and feet.3 The primary cause is repeated exposure to cold, not freezing, temperatures.

Trench foot or cold immersion foot (or hand) is a nonfreezing injury to the hands or feet caused by chronic exposure to wet conditions and temperatures above freezing.3 Painful burning and dysesthesia as well as tissue damage involving edema, blistering, redness, ecchymosis, and ulceration are common. Cellulitis is a bacterial infection of the skin and underlying tissues that can occur anywhere on the body, but the legs are most commonly affected. Typical presentation involves erythema, warmth, swelling, and pain in the infected area.

Although the conditions described above may be considered in the differential diagnosis, physical examination and the patient’s clinical history typically will allow for the distinction of frostbite from these other disease processes.

- Petrone P, Kuncir EJ, Asensio JA. Surgical management and strategies in the treatment of hypothermia and cold injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:1165-1178.

- Reamy BV. Frostbite: review and current concepts. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:34-40.

- Jurkovich GJ. Environmental cold-induced injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:247-267, viii.

- Biem J, Koehncke N, Classen D, et al. Out of the cold: management of hypothermia and frostbite. CMAJ. 2003;168:305-311.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old homeless man presented to the emergency department after being found wandering in the middle of winter in Detroit, Michigan, with altered mental status. A workup for his mental incapacitation uncovered severe electrolyte disturbances, hyperglycemia, and acute renal failure, as well as both alcohol and drug intoxication. After 1 day of admission the patient reported progressive swelling, blistering, and pain in the right hand. The pain was stabbing in nature, worse with movement, and graded 10 of 10 (1=minimal; 10=severe). His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus with peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol and drug abuse. The patient was not taking any medications for these conditions.

Physical examination revealed 2+ moderate pitting edema in all distal extremities, with increased edema of the dorsal aspect of the right hand. The right hand also demonstrated patchy erythema and was warm to touch. The dorsal aspect of the right ring finger had a dusky tip and was studded with several tense blisters (Figure). Vital signs were stable. Based on the patient’s history and physical examination findings, a diagnosis of frostbite was made. Our treatment process involved several modalities including immersion of the affected site in a warm water bath, surgical debridement of blistered sites, tetanus toxoid, penicillin to prevent infection, and oral ibuprofen for pain management. At 3-day follow-up, the patient’s condition substantially improved with a decreased amount of erythema, edema, and pain. All affected sites were successfully preserved with no evidence of focal, motor, or sensory impairment.

Frostbite is a form of localized tissue injury due to extreme cold that most commonly affects the hands and feet, with the greatest incidence occurring in adults aged 30 to 49 years.1,2 Other sites commonly affected include the ears, nose, cheeks, and penis. Frostbite injuries can be categorized into 4 degrees of severity that correlate with the clinical presentation.1,3 Rewarming the affected site is necessary to properly classify the injury, as the initial appearance may be similar among the different degrees of injury. A first-degree injury classically shows a central white plaque with peripheral erythema and is extremely cold to touch. Second-degree injuries display tense blisters filled with clear or milky fluid surrounded by erythema and edema within the first 24 hours. Third-degree injuries are associated with hemorrhagic blisters. Fourth-degree injuries involve complete tissue loss and necrosis.1 Frostbite injuries also may be classified as superficial or deep; the former affects skin and subcutaneous tissue, while the latter affects bones, joints, and tendons.3,4 The superficial form exhibits clear blisters, whereas hemorrhagic blisters demonstrate deep frostbite.

Factors such as the surrounding temperature, length of exposure, and alcohol consumption may exacerbate frostbite injuries.1 Conditions such as atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus, which can cause neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease, also are potential risks. Psychiatric patients also are at risk for frostbite given the propensity for eccentric behavior as well as the homeless due to inadequate clothing or shelter. Diagnosis often can be made based on medical history and physical examination, though techniques such as radiography, angiography, digital plethysmography, Doppler ultrasonography, and bone scintigraphy (technetium-99) also have been utilized to determine severity and prognosis.2 Differential diagnoses of frostbite are listed in the Table.

Frostbite treatment begins with removal of wet clothing and region protection. Rewarming the site should not begin until refreezing is unlikely to occur and involves placing the injured area in water (temperature, 40°C–42°C) for 15 to 30 minutes to minimize tissue loss.1,2 Analgesics, tetanus toxoid, oral ibuprofen, and benzylpenicillin also are indicated, along with daily hydrotherapy.1,2 White blisters should be debrided, while hemorrhagic blisters should be left intact. Amputation and aggressive debridement typically are delayed until complete ischemia occurs and final demarcation is determined, usually over 1 to 3 months.1 Combination therapy allowed for a positive outcome in our patient.

Frostnip is a mild form of cold injury characterized by localized pain, pallor, and possible numbness.3 Warming the cold area restores the function and sensation with no loss of tissue. Chilblain or pernio refers to a localized cold injury that typically presents as pruritic red-purple papules, macules, plaques, or nodules on the face, anterior tibial surface, or dorsum and tips of the hands and feet.3 The primary cause is repeated exposure to cold, not freezing, temperatures.

Trench foot or cold immersion foot (or hand) is a nonfreezing injury to the hands or feet caused by chronic exposure to wet conditions and temperatures above freezing.3 Painful burning and dysesthesia as well as tissue damage involving edema, blistering, redness, ecchymosis, and ulceration are common. Cellulitis is a bacterial infection of the skin and underlying tissues that can occur anywhere on the body, but the legs are most commonly affected. Typical presentation involves erythema, warmth, swelling, and pain in the infected area.

Although the conditions described above may be considered in the differential diagnosis, physical examination and the patient’s clinical history typically will allow for the distinction of frostbite from these other disease processes.

To the Editor:

A 58-year-old homeless man presented to the emergency department after being found wandering in the middle of winter in Detroit, Michigan, with altered mental status. A workup for his mental incapacitation uncovered severe electrolyte disturbances, hyperglycemia, and acute renal failure, as well as both alcohol and drug intoxication. After 1 day of admission the patient reported progressive swelling, blistering, and pain in the right hand. The pain was stabbing in nature, worse with movement, and graded 10 of 10 (1=minimal; 10=severe). His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus with peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol and drug abuse. The patient was not taking any medications for these conditions.

Physical examination revealed 2+ moderate pitting edema in all distal extremities, with increased edema of the dorsal aspect of the right hand. The right hand also demonstrated patchy erythema and was warm to touch. The dorsal aspect of the right ring finger had a dusky tip and was studded with several tense blisters (Figure). Vital signs were stable. Based on the patient’s history and physical examination findings, a diagnosis of frostbite was made. Our treatment process involved several modalities including immersion of the affected site in a warm water bath, surgical debridement of blistered sites, tetanus toxoid, penicillin to prevent infection, and oral ibuprofen for pain management. At 3-day follow-up, the patient’s condition substantially improved with a decreased amount of erythema, edema, and pain. All affected sites were successfully preserved with no evidence of focal, motor, or sensory impairment.

Frostbite is a form of localized tissue injury due to extreme cold that most commonly affects the hands and feet, with the greatest incidence occurring in adults aged 30 to 49 years.1,2 Other sites commonly affected include the ears, nose, cheeks, and penis. Frostbite injuries can be categorized into 4 degrees of severity that correlate with the clinical presentation.1,3 Rewarming the affected site is necessary to properly classify the injury, as the initial appearance may be similar among the different degrees of injury. A first-degree injury classically shows a central white plaque with peripheral erythema and is extremely cold to touch. Second-degree injuries display tense blisters filled with clear or milky fluid surrounded by erythema and edema within the first 24 hours. Third-degree injuries are associated with hemorrhagic blisters. Fourth-degree injuries involve complete tissue loss and necrosis.1 Frostbite injuries also may be classified as superficial or deep; the former affects skin and subcutaneous tissue, while the latter affects bones, joints, and tendons.3,4 The superficial form exhibits clear blisters, whereas hemorrhagic blisters demonstrate deep frostbite.

Factors such as the surrounding temperature, length of exposure, and alcohol consumption may exacerbate frostbite injuries.1 Conditions such as atherosclerosis and diabetes mellitus, which can cause neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease, also are potential risks. Psychiatric patients also are at risk for frostbite given the propensity for eccentric behavior as well as the homeless due to inadequate clothing or shelter. Diagnosis often can be made based on medical history and physical examination, though techniques such as radiography, angiography, digital plethysmography, Doppler ultrasonography, and bone scintigraphy (technetium-99) also have been utilized to determine severity and prognosis.2 Differential diagnoses of frostbite are listed in the Table.

Frostbite treatment begins with removal of wet clothing and region protection. Rewarming the site should not begin until refreezing is unlikely to occur and involves placing the injured area in water (temperature, 40°C–42°C) for 15 to 30 minutes to minimize tissue loss.1,2 Analgesics, tetanus toxoid, oral ibuprofen, and benzylpenicillin also are indicated, along with daily hydrotherapy.1,2 White blisters should be debrided, while hemorrhagic blisters should be left intact. Amputation and aggressive debridement typically are delayed until complete ischemia occurs and final demarcation is determined, usually over 1 to 3 months.1 Combination therapy allowed for a positive outcome in our patient.

Frostnip is a mild form of cold injury characterized by localized pain, pallor, and possible numbness.3 Warming the cold area restores the function and sensation with no loss of tissue. Chilblain or pernio refers to a localized cold injury that typically presents as pruritic red-purple papules, macules, plaques, or nodules on the face, anterior tibial surface, or dorsum and tips of the hands and feet.3 The primary cause is repeated exposure to cold, not freezing, temperatures.

Trench foot or cold immersion foot (or hand) is a nonfreezing injury to the hands or feet caused by chronic exposure to wet conditions and temperatures above freezing.3 Painful burning and dysesthesia as well as tissue damage involving edema, blistering, redness, ecchymosis, and ulceration are common. Cellulitis is a bacterial infection of the skin and underlying tissues that can occur anywhere on the body, but the legs are most commonly affected. Typical presentation involves erythema, warmth, swelling, and pain in the infected area.

Although the conditions described above may be considered in the differential diagnosis, physical examination and the patient’s clinical history typically will allow for the distinction of frostbite from these other disease processes.

- Petrone P, Kuncir EJ, Asensio JA. Surgical management and strategies in the treatment of hypothermia and cold injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:1165-1178.

- Reamy BV. Frostbite: review and current concepts. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:34-40.

- Jurkovich GJ. Environmental cold-induced injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:247-267, viii.

- Biem J, Koehncke N, Classen D, et al. Out of the cold: management of hypothermia and frostbite. CMAJ. 2003;168:305-311.

- Petrone P, Kuncir EJ, Asensio JA. Surgical management and strategies in the treatment of hypothermia and cold injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:1165-1178.

- Reamy BV. Frostbite: review and current concepts. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1998;11:34-40.

- Jurkovich GJ. Environmental cold-induced injury. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:247-267, viii.

- Biem J, Koehncke N, Classen D, et al. Out of the cold: management of hypothermia and frostbite. CMAJ. 2003;168:305-311.

Disseminated Waxy Papules: A Sign of Systemic Disease

To the Editor:

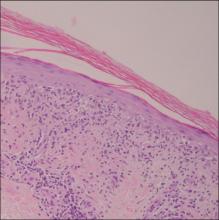

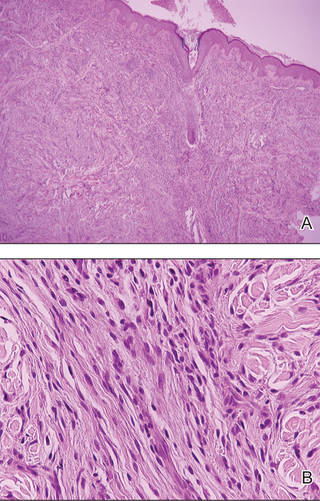

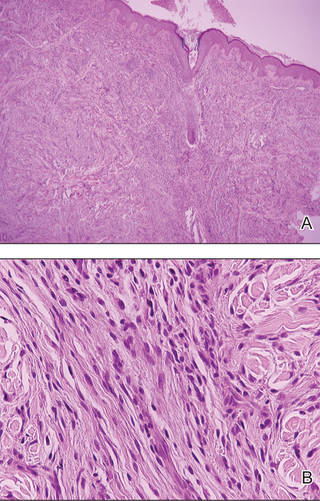

A 35-year-old man presented with asymptomatic multiple waxy firm papules on the dorsal aspect of the hands (Figure 1). On complete clinical examination, multiple similar lesions were found on the face and the lateral aspect of the neck; slightly pruritic, clustered, erythematous papules were seen in the pubic area. Deep longitudinal furrows on the glabella and swelling of the ears (Figure 2) also were present. Histology revealed a dermal infiltrate of fibroblasts (Figure 3). Abundant mucin deposition between collagen bundles stained positive with Alcian blue, confirming the diagnosis of generalized lichen myxedematosus (GLM). A thorough laboratory evaluation revealed λ light chain gammopathy. Bone marrow examination was normal. Thyroid function tests and radiography did not detect any abnormalities.

Being a musician, the patient traveled frequently and therefore did not present for follow-up. The disease ran its course. Approximately 6 months later he presented with a generalized eruption with weakness and intense bone pain. Progression to multiple myeloma was confirmed by serum protein electrophoresis and plain radiography, which revealed lytic lesions of the skull.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus, or scleromyxedema, is a form of papular mucinosis. It is a cutaneous mucinosis characterized by a generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption, mucin deposition, increased fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis, and monoclonal gammopathy in the absence of thyroid disease. It is a rare disease that does not have a gender predilection and affects men and women aged 30 to 80 years.1,2

Clinically, GLM is characterized by a widespread symmetric eruption of small, closely spaced, waxy, firm, dome-shaped or flat-topped papules that measure 2 to 3 mm in diameter. Papules commonly form clusters on the face, neck, distal forearms, and hands. The affected skin may have a shiny sclerodermatous appearance.2

Histologically, there is a pronounced mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, along with a proliferation of irregularly arranged fibroblasts and fibrosis.3 Collagen bundles appear pushed together into fascicles by the mucinous deposits.4

Generalized lichen myxedematosus should be distinguished from nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, granuloma annulare, amyloidosis, and Hansen disease. In nearly 83% of cases there is an accompanying paraproteinemia, most commonly an IgG λ light chain elevation.2 Monoclonal gammopathy of IgG with λ light chain has been considered as a fibroblast growth factor. Paraprotein levels do not correlate with the extent or progression of the disease.1 Nonparaprotein factors also can be responsible for excess fibroblast proliferation.2 It still is not elucidated as to how the abnormal mucin production results from the proliferation of fibroblasts.

Patients with GLM must be closely followed. The course of the disease is chronic and progressive. Extracutaneous manifestations may involve the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and central nervous systems, most likely because of mucin deposition in various organs.1,4 In these cases, the life expectancy is limited. Possibility of progression to multiple myeloma is less than 10%.1 Waldenström macroglobulinemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas all have been associated with GLM.2 Although extremely uncommon, spontaneous resolution has been reported after as long as a decade.5

Treatment of GLM, including melphalan, plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, thalidomide, electron beam therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, extracorporeal photochemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue, and melphalan with autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant are considered to improve the prognosis of this noncurable disease.6 As there is still no consensus on the treatment of scleromyxedema, multicenter studies on therapeutic schemes and responses are anticipated.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus is an instructive example of skin lesions being the presenting sign of a systemic disease. Progression to multiple myeloma in our patient made the prognosis less favorable.

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104.

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Pomann JJ, Rudner EJ. Scleromyxedema revisited. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:31-35.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37-43.

- Heymann WR. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:890-891.

To the Editor:

A 35-year-old man presented with asymptomatic multiple waxy firm papules on the dorsal aspect of the hands (Figure 1). On complete clinical examination, multiple similar lesions were found on the face and the lateral aspect of the neck; slightly pruritic, clustered, erythematous papules were seen in the pubic area. Deep longitudinal furrows on the glabella and swelling of the ears (Figure 2) also were present. Histology revealed a dermal infiltrate of fibroblasts (Figure 3). Abundant mucin deposition between collagen bundles stained positive with Alcian blue, confirming the diagnosis of generalized lichen myxedematosus (GLM). A thorough laboratory evaluation revealed λ light chain gammopathy. Bone marrow examination was normal. Thyroid function tests and radiography did not detect any abnormalities.

Being a musician, the patient traveled frequently and therefore did not present for follow-up. The disease ran its course. Approximately 6 months later he presented with a generalized eruption with weakness and intense bone pain. Progression to multiple myeloma was confirmed by serum protein electrophoresis and plain radiography, which revealed lytic lesions of the skull.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus, or scleromyxedema, is a form of papular mucinosis. It is a cutaneous mucinosis characterized by a generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption, mucin deposition, increased fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis, and monoclonal gammopathy in the absence of thyroid disease. It is a rare disease that does not have a gender predilection and affects men and women aged 30 to 80 years.1,2

Clinically, GLM is characterized by a widespread symmetric eruption of small, closely spaced, waxy, firm, dome-shaped or flat-topped papules that measure 2 to 3 mm in diameter. Papules commonly form clusters on the face, neck, distal forearms, and hands. The affected skin may have a shiny sclerodermatous appearance.2

Histologically, there is a pronounced mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, along with a proliferation of irregularly arranged fibroblasts and fibrosis.3 Collagen bundles appear pushed together into fascicles by the mucinous deposits.4

Generalized lichen myxedematosus should be distinguished from nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, granuloma annulare, amyloidosis, and Hansen disease. In nearly 83% of cases there is an accompanying paraproteinemia, most commonly an IgG λ light chain elevation.2 Monoclonal gammopathy of IgG with λ light chain has been considered as a fibroblast growth factor. Paraprotein levels do not correlate with the extent or progression of the disease.1 Nonparaprotein factors also can be responsible for excess fibroblast proliferation.2 It still is not elucidated as to how the abnormal mucin production results from the proliferation of fibroblasts.

Patients with GLM must be closely followed. The course of the disease is chronic and progressive. Extracutaneous manifestations may involve the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and central nervous systems, most likely because of mucin deposition in various organs.1,4 In these cases, the life expectancy is limited. Possibility of progression to multiple myeloma is less than 10%.1 Waldenström macroglobulinemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas all have been associated with GLM.2 Although extremely uncommon, spontaneous resolution has been reported after as long as a decade.5

Treatment of GLM, including melphalan, plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, thalidomide, electron beam therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, extracorporeal photochemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue, and melphalan with autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant are considered to improve the prognosis of this noncurable disease.6 As there is still no consensus on the treatment of scleromyxedema, multicenter studies on therapeutic schemes and responses are anticipated.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus is an instructive example of skin lesions being the presenting sign of a systemic disease. Progression to multiple myeloma in our patient made the prognosis less favorable.

To the Editor:

A 35-year-old man presented with asymptomatic multiple waxy firm papules on the dorsal aspect of the hands (Figure 1). On complete clinical examination, multiple similar lesions were found on the face and the lateral aspect of the neck; slightly pruritic, clustered, erythematous papules were seen in the pubic area. Deep longitudinal furrows on the glabella and swelling of the ears (Figure 2) also were present. Histology revealed a dermal infiltrate of fibroblasts (Figure 3). Abundant mucin deposition between collagen bundles stained positive with Alcian blue, confirming the diagnosis of generalized lichen myxedematosus (GLM). A thorough laboratory evaluation revealed λ light chain gammopathy. Bone marrow examination was normal. Thyroid function tests and radiography did not detect any abnormalities.

Being a musician, the patient traveled frequently and therefore did not present for follow-up. The disease ran its course. Approximately 6 months later he presented with a generalized eruption with weakness and intense bone pain. Progression to multiple myeloma was confirmed by serum protein electrophoresis and plain radiography, which revealed lytic lesions of the skull.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus, or scleromyxedema, is a form of papular mucinosis. It is a cutaneous mucinosis characterized by a generalized papular and sclerodermoid eruption, mucin deposition, increased fibroblast proliferation, fibrosis, and monoclonal gammopathy in the absence of thyroid disease. It is a rare disease that does not have a gender predilection and affects men and women aged 30 to 80 years.1,2

Clinically, GLM is characterized by a widespread symmetric eruption of small, closely spaced, waxy, firm, dome-shaped or flat-topped papules that measure 2 to 3 mm in diameter. Papules commonly form clusters on the face, neck, distal forearms, and hands. The affected skin may have a shiny sclerodermatous appearance.2

Histologically, there is a pronounced mucin deposition within the upper and mid reticular dermis, along with a proliferation of irregularly arranged fibroblasts and fibrosis.3 Collagen bundles appear pushed together into fascicles by the mucinous deposits.4

Generalized lichen myxedematosus should be distinguished from nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, granuloma annulare, amyloidosis, and Hansen disease. In nearly 83% of cases there is an accompanying paraproteinemia, most commonly an IgG λ light chain elevation.2 Monoclonal gammopathy of IgG with λ light chain has been considered as a fibroblast growth factor. Paraprotein levels do not correlate with the extent or progression of the disease.1 Nonparaprotein factors also can be responsible for excess fibroblast proliferation.2 It still is not elucidated as to how the abnormal mucin production results from the proliferation of fibroblasts.

Patients with GLM must be closely followed. The course of the disease is chronic and progressive. Extracutaneous manifestations may involve the gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and central nervous systems, most likely because of mucin deposition in various organs.1,4 In these cases, the life expectancy is limited. Possibility of progression to multiple myeloma is less than 10%.1 Waldenström macroglobulinemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphomas all have been associated with GLM.2 Although extremely uncommon, spontaneous resolution has been reported after as long as a decade.5

Treatment of GLM, including melphalan, plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, thalidomide, electron beam therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, extracorporeal photochemotherapy, high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue, and melphalan with autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplant are considered to improve the prognosis of this noncurable disease.6 As there is still no consensus on the treatment of scleromyxedema, multicenter studies on therapeutic schemes and responses are anticipated.

Generalized lichen myxedematosus is an instructive example of skin lesions being the presenting sign of a systemic disease. Progression to multiple myeloma in our patient made the prognosis less favorable.

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104.

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Pomann JJ, Rudner EJ. Scleromyxedema revisited. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:31-35.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37-43.

- Heymann WR. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:890-891.

- Rongioletti F. Lichen myxedematosus (papular mucinosis): new concepts and perspectives for an old disease. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:100-104.

- Cokonis Georgakis CD, Falasca G, Georgakis A, et al. Scleromyxedema. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:493-497.

- Rongioletti F, Rebora A. Updated classification of papular mucinosis, lichen myxedematosus, and scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:273-281.

- Pomann JJ, Rudner EJ. Scleromyxedema revisited. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:31-35.

- Dinneen AM, Dicken CH. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:37-43.

- Heymann WR. Scleromyxedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:890-891.

Photoinduced Classic Sweet Syndrome Presenting as Hemorrhagic Bullae

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

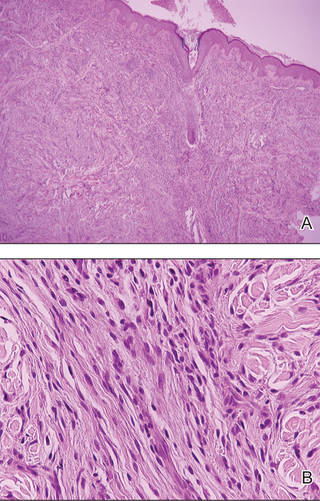

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.

Primary Cutaneous Plasmacytoma

To the Editor:

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs as an isolated finding without detectable underlying multiple myeloma. Uncommonly, it has been reported to occur in the skin as a primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (PCP). We describe a case of an asymptomatic plaque on the back that was found to contain a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells without evidence of systemic disease despite thorough evaluation. We also include a brief discussion of PCPs, including diagnosis and treatment.

An indurated plaque was discovered on the upper back of a 57-year-old man during a routine follow-up visit for acne treatment. The patient reported the lesion had been present for approximately 2 years; it was asymptomatic and had not increased in size. A review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, osteoarthritis, acne, type 2 diabetes mellitus, well-controlled herpes labialis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Physical examination revealed a nontender 2-cm erythematous plaque on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). No other lesions or lymphadenopathy were noted. A biopsy was performed to rule out a primary neoplasm or metastatic lesion. Histopathologic examination of 3 separate punch biopsies revealed a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 2). On immunohistochemical staining, the plasma cells essentially were all κ positive, with rare λ-positive plasma cells (Figure 3).

The patient underwent complete evaluation for myeloma. A bone marrow biopsy was negative with no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia. A skeletal survey showed no lytic lesions, and serum and urine protein electrophoreses were negative for M proteins. Urine immunofixation was negative for Bence Jones proteins. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of disease. Serum free k light chains were elevated at 32 mg/L (reference range, <19.4 mg/L), and IgA and b2-microglobulin also were elevated at 435 mg/dL (reference range, <400 mg/dL) and 2.8 mg/L (reference range, <1.8 mg/L), respectively. The k:λ ratio was slightly elevated at 2.2 (reference range, 0.26–1.65).

Local radiotherapy was considered but was rejected by the patient. A single 5-mg/cc intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (1 cc total) was administered, which resulted in modest improvement but did not yield complete resolution. A repeat biopsy showed a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells with areas of follicular mucinosis. Immunohistochemical studies also demonstrated CD3+ lymphocytes with more CD4+ cells than CD8+ cells and scattered CD20+ cells. Repeat serum and urine protein electrophoreses as well as bone marrow biopsy were negative or myeloma.

Because of the localized and recalcitrant nature of the neoplasm, the patient underwent wide local excision. Positron emission tomography performed 1 year following surgery demonstrated no residual disease. The patient has had no clinical recurrence but has demonstrated persistently elevated free k light chains. Seven years following the excision, there was no evidence of systemic disease.

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs without detectable underlying multiple myeloma.1 Originally classified as a discrete entity, PCP currently is considered to be a variant of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.2 Cases of localization to the skin are thought to represent 2% to 4% of all primary extramedullary plasmacytomas.3 Very few cases of PCPs have been reported in the literature thus far.1 Primary cutaneous plasmacytomas are most commonly reported in Asian men, with an age range of 22 to 88 years; lesions typically present as slow-growing, reddish brown macules or plaques on the face, trunk, or extremities.4 They may be single or multiple, though solitary lesions are thought to portend a better prognosis. Associated features include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 Multiple myeloma has been estimated to develop in one-third of patients.6 Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma also has been linked to organ transplantation and Epstein-Barr virus–associated proteins7 as well as recurrent herpes simplex virus infections.8

Diagnosis is based on a proliferation of a clonal k or λ light chain with the exclusion of multiple myeloma.9 Typical histologic findings include a diffuse or nodular dermal and subcuticular infiltrate of plasma cells, often with a grenz zone. Less commonly, an interstitial pattern predominates, mimicking a benign inflammatory process.4 The plasma cells may display varying degrees of maturation and atypia but no epidermotropism.10 On immunohistochemical staining, plasma cells stain positive for CD79a, CD34, and CD138, and also may stain positively for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.4

The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous plasmacytoma occurring in the setting of systemic disease, and reactive polyclonal processes occurring in the setting of chronic infection or autoimmune disease. Possible treatment options include intralesional steroids, psoralen plus UVA, topical immunomodulators,10 local radiotherapy,11 and excision. Prognosis is varied, with reported cases showing complete remission, local recurrence, and progression to systemic disease, with the development of multiple myeloma in one-third of cases.4 More aggressive cases are associated with multiple lesions, larger size, and IgA secretion by neoplastic cells.

Our patient with a solitary dermal infiltrate of monoclonal plasma cells did not have bone marrow involvement and had an unexplained elevated level of free k light chains in the serum. This unexplained relationship underscores the importance of continued surveillance in any cutaneous lymphoma.

1. Rongioletti F, Patterson JW, Rebora A. The histological and pathogenetic spectrum of cutaneous disease in monoclonal gammopathies. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:705-721.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Muscardin LM, Pulsoni A, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: report of a case with review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):962-965.

4. Kazakov DV, Belousova IE, Müller B, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: a clinicopathological study of two cases with a long-term follow-up and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:244-248.

5. Aricò M, Bongiorno MR. Primary cutaneous plasmacytosis in a child. is this a new entity? J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2002;16:164-167.

6. Willoughby V, Werlang-Perurena A, Kelly A, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, plasmacytoma-like) in a heart transplant patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:442-445.

7. Buffet M, Dupin N, Carlotti A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous plasmacytoma post–solid organ transplantation [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:1085-1091.

8. Zendri E, Venturi C, Ricci R, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: a role for a triggering stimulus? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:229-231.

9. Tüting T, Bork K. Primary plasmacytoma of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2, pt 2):386-390.

10. Miura H, Itami S, Yoshikawa K. Treatment of facial lesion of cutaneous plasmacytosis with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1195-1196.

11. Tessari G, Fabbian F, Colato C, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma after rejection of a transplanted kidney: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. 2004;80:361-364.

To the Editor:

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs as an isolated finding without detectable underlying multiple myeloma. Uncommonly, it has been reported to occur in the skin as a primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (PCP). We describe a case of an asymptomatic plaque on the back that was found to contain a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells without evidence of systemic disease despite thorough evaluation. We also include a brief discussion of PCPs, including diagnosis and treatment.

An indurated plaque was discovered on the upper back of a 57-year-old man during a routine follow-up visit for acne treatment. The patient reported the lesion had been present for approximately 2 years; it was asymptomatic and had not increased in size. A review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, osteoarthritis, acne, type 2 diabetes mellitus, well-controlled herpes labialis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Physical examination revealed a nontender 2-cm erythematous plaque on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). No other lesions or lymphadenopathy were noted. A biopsy was performed to rule out a primary neoplasm or metastatic lesion. Histopathologic examination of 3 separate punch biopsies revealed a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 2). On immunohistochemical staining, the plasma cells essentially were all κ positive, with rare λ-positive plasma cells (Figure 3).

The patient underwent complete evaluation for myeloma. A bone marrow biopsy was negative with no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia. A skeletal survey showed no lytic lesions, and serum and urine protein electrophoreses were negative for M proteins. Urine immunofixation was negative for Bence Jones proteins. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of disease. Serum free k light chains were elevated at 32 mg/L (reference range, <19.4 mg/L), and IgA and b2-microglobulin also were elevated at 435 mg/dL (reference range, <400 mg/dL) and 2.8 mg/L (reference range, <1.8 mg/L), respectively. The k:λ ratio was slightly elevated at 2.2 (reference range, 0.26–1.65).

Local radiotherapy was considered but was rejected by the patient. A single 5-mg/cc intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (1 cc total) was administered, which resulted in modest improvement but did not yield complete resolution. A repeat biopsy showed a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells with areas of follicular mucinosis. Immunohistochemical studies also demonstrated CD3+ lymphocytes with more CD4+ cells than CD8+ cells and scattered CD20+ cells. Repeat serum and urine protein electrophoreses as well as bone marrow biopsy were negative or myeloma.

Because of the localized and recalcitrant nature of the neoplasm, the patient underwent wide local excision. Positron emission tomography performed 1 year following surgery demonstrated no residual disease. The patient has had no clinical recurrence but has demonstrated persistently elevated free k light chains. Seven years following the excision, there was no evidence of systemic disease.

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs without detectable underlying multiple myeloma.1 Originally classified as a discrete entity, PCP currently is considered to be a variant of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.2 Cases of localization to the skin are thought to represent 2% to 4% of all primary extramedullary plasmacytomas.3 Very few cases of PCPs have been reported in the literature thus far.1 Primary cutaneous plasmacytomas are most commonly reported in Asian men, with an age range of 22 to 88 years; lesions typically present as slow-growing, reddish brown macules or plaques on the face, trunk, or extremities.4 They may be single or multiple, though solitary lesions are thought to portend a better prognosis. Associated features include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 Multiple myeloma has been estimated to develop in one-third of patients.6 Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma also has been linked to organ transplantation and Epstein-Barr virus–associated proteins7 as well as recurrent herpes simplex virus infections.8

Diagnosis is based on a proliferation of a clonal k or λ light chain with the exclusion of multiple myeloma.9 Typical histologic findings include a diffuse or nodular dermal and subcuticular infiltrate of plasma cells, often with a grenz zone. Less commonly, an interstitial pattern predominates, mimicking a benign inflammatory process.4 The plasma cells may display varying degrees of maturation and atypia but no epidermotropism.10 On immunohistochemical staining, plasma cells stain positive for CD79a, CD34, and CD138, and also may stain positively for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.4

The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous plasmacytoma occurring in the setting of systemic disease, and reactive polyclonal processes occurring in the setting of chronic infection or autoimmune disease. Possible treatment options include intralesional steroids, psoralen plus UVA, topical immunomodulators,10 local radiotherapy,11 and excision. Prognosis is varied, with reported cases showing complete remission, local recurrence, and progression to systemic disease, with the development of multiple myeloma in one-third of cases.4 More aggressive cases are associated with multiple lesions, larger size, and IgA secretion by neoplastic cells.

Our patient with a solitary dermal infiltrate of monoclonal plasma cells did not have bone marrow involvement and had an unexplained elevated level of free k light chains in the serum. This unexplained relationship underscores the importance of continued surveillance in any cutaneous lymphoma.

To the Editor:

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs as an isolated finding without detectable underlying multiple myeloma. Uncommonly, it has been reported to occur in the skin as a primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (PCP). We describe a case of an asymptomatic plaque on the back that was found to contain a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells without evidence of systemic disease despite thorough evaluation. We also include a brief discussion of PCPs, including diagnosis and treatment.

An indurated plaque was discovered on the upper back of a 57-year-old man during a routine follow-up visit for acne treatment. The patient reported the lesion had been present for approximately 2 years; it was asymptomatic and had not increased in size. A review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. His medical history included hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, osteoarthritis, acne, type 2 diabetes mellitus, well-controlled herpes labialis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Physical examination revealed a nontender 2-cm erythematous plaque on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). No other lesions or lymphadenopathy were noted. A biopsy was performed to rule out a primary neoplasm or metastatic lesion. Histopathologic examination of 3 separate punch biopsies revealed a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 2). On immunohistochemical staining, the plasma cells essentially were all κ positive, with rare λ-positive plasma cells (Figure 3).

The patient underwent complete evaluation for myeloma. A bone marrow biopsy was negative with no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia. A skeletal survey showed no lytic lesions, and serum and urine protein electrophoreses were negative for M proteins. Urine immunofixation was negative for Bence Jones proteins. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of disease. Serum free k light chains were elevated at 32 mg/L (reference range, <19.4 mg/L), and IgA and b2-microglobulin also were elevated at 435 mg/dL (reference range, <400 mg/dL) and 2.8 mg/L (reference range, <1.8 mg/L), respectively. The k:λ ratio was slightly elevated at 2.2 (reference range, 0.26–1.65).

Local radiotherapy was considered but was rejected by the patient. A single 5-mg/cc intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (1 cc total) was administered, which resulted in modest improvement but did not yield complete resolution. A repeat biopsy showed a monoclonal proliferation of plasma cells with areas of follicular mucinosis. Immunohistochemical studies also demonstrated CD3+ lymphocytes with more CD4+ cells than CD8+ cells and scattered CD20+ cells. Repeat serum and urine protein electrophoreses as well as bone marrow biopsy were negative or myeloma.

Because of the localized and recalcitrant nature of the neoplasm, the patient underwent wide local excision. Positron emission tomography performed 1 year following surgery demonstrated no residual disease. The patient has had no clinical recurrence but has demonstrated persistently elevated free k light chains. Seven years following the excision, there was no evidence of systemic disease.

Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare plasma cell neoplasm that occurs without detectable underlying multiple myeloma.1 Originally classified as a discrete entity, PCP currently is considered to be a variant of primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma.2 Cases of localization to the skin are thought to represent 2% to 4% of all primary extramedullary plasmacytomas.3 Very few cases of PCPs have been reported in the literature thus far.1 Primary cutaneous plasmacytomas are most commonly reported in Asian men, with an age range of 22 to 88 years; lesions typically present as slow-growing, reddish brown macules or plaques on the face, trunk, or extremities.4 They may be single or multiple, though solitary lesions are thought to portend a better prognosis. Associated features include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, hypergammaglobulinemia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 Multiple myeloma has been estimated to develop in one-third of patients.6 Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma also has been linked to organ transplantation and Epstein-Barr virus–associated proteins7 as well as recurrent herpes simplex virus infections.8

Diagnosis is based on a proliferation of a clonal k or λ light chain with the exclusion of multiple myeloma.9 Typical histologic findings include a diffuse or nodular dermal and subcuticular infiltrate of plasma cells, often with a grenz zone. Less commonly, an interstitial pattern predominates, mimicking a benign inflammatory process.4 The plasma cells may display varying degrees of maturation and atypia but no epidermotropism.10 On immunohistochemical staining, plasma cells stain positive for CD79a, CD34, and CD138, and also may stain positively for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin.4

The differential diagnosis includes cutaneous plasmacytoma occurring in the setting of systemic disease, and reactive polyclonal processes occurring in the setting of chronic infection or autoimmune disease. Possible treatment options include intralesional steroids, psoralen plus UVA, topical immunomodulators,10 local radiotherapy,11 and excision. Prognosis is varied, with reported cases showing complete remission, local recurrence, and progression to systemic disease, with the development of multiple myeloma in one-third of cases.4 More aggressive cases are associated with multiple lesions, larger size, and IgA secretion by neoplastic cells.

Our patient with a solitary dermal infiltrate of monoclonal plasma cells did not have bone marrow involvement and had an unexplained elevated level of free k light chains in the serum. This unexplained relationship underscores the importance of continued surveillance in any cutaneous lymphoma.

1. Rongioletti F, Patterson JW, Rebora A. The histological and pathogenetic spectrum of cutaneous disease in monoclonal gammopathies. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:705-721.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Muscardin LM, Pulsoni A, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: report of a case with review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):962-965.

4. Kazakov DV, Belousova IE, Müller B, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: a clinicopathological study of two cases with a long-term follow-up and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:244-248.

5. Aricò M, Bongiorno MR. Primary cutaneous plasmacytosis in a child. is this a new entity? J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2002;16:164-167.

6. Willoughby V, Werlang-Perurena A, Kelly A, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, plasmacytoma-like) in a heart transplant patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:442-445.

7. Buffet M, Dupin N, Carlotti A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous plasmacytoma post–solid organ transplantation [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:1085-1091.

8. Zendri E, Venturi C, Ricci R, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: a role for a triggering stimulus? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:229-231.

9. Tüting T, Bork K. Primary plasmacytoma of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34(2, pt 2):386-390.

10. Miura H, Itami S, Yoshikawa K. Treatment of facial lesion of cutaneous plasmacytosis with tacrolimus ointment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1195-1196.

11. Tessari G, Fabbian F, Colato C, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma after rejection of a transplanted kidney: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. 2004;80:361-364.

1. Rongioletti F, Patterson JW, Rebora A. The histological and pathogenetic spectrum of cutaneous disease in monoclonal gammopathies. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:705-721.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Muscardin LM, Pulsoni A, Cerroni L. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: report of a case with review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5, pt 2):962-965.

4. Kazakov DV, Belousova IE, Müller B, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma: a clinicopathological study of two cases with a long-term follow-up and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:244-248.

5. Aricò M, Bongiorno MR. Primary cutaneous plasmacytosis in a child. is this a new entity? J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2002;16:164-167.

6. Willoughby V, Werlang-Perurena A, Kelly A, et al. Primary cutaneous plasmacytoma (posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, plasmacytoma-like) in a heart transplant patient. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:442-445.

7. Buffet M, Dupin N, Carlotti A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus–associated cutaneous plasmacytoma post–solid organ transplantation [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2004;131:1085-1091.