User login

COVID-19 has brought more complex, longer office visits

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

Evidence of this came from the latest Primary Care Collaborative (PCC) survey, which found that primary care clinicians are seeing more complex patients requiring longer appointments in the wake of COVID-19.

The PCC with the Larry A. Green Center regularly surveys primary care clinicians. This round of questions came August 14-17 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories.

More than 7 in 10 (71%) respondents said their patients are more complex and nearly the same percentage said appointments are taking more time.

Ann Greiner, president and CEO of the PCC, said in an interview that 55% of respondents reported that clinicians are struggling to keep up with pent-up demand after patients have delayed or canceled care. Sixty-five percent in the survey said they had seen a rise in children’s mental health issues, and 58% said they were unsure how to help their patients with long COVID.

In addition, primary care clinicians are having repeated conversations with patients on why they should get a vaccine and which one.

“I think that’s adding to the complexity. There is a lot going on here with patient trust,” Ms. Greiner said.

‘We’re going to be playing catch-up’

Jacqueline Fincher, MD, an internist in Thompson, Ga., said in an interview that appointments have gotten longer and more complex in the wake of the pandemic – “no question.”

The immediate past president of the American College of Physicians is seeing patients with chronic disease that has gone untreated for sometimes a year or more, she said.

“Their blood pressure was not under good control, they were under more stress, their sugars were up and weren’t being followed as closely for conditions such as congestive heart failure,” she said.

Dr. Fincher, who works in a rural practice 40 miles from Augusta, Ga., with her physician husband and two other physicians, said patients are ready to come back in, “but I don’t have enough slots for them.”

She said she prioritizes what to help patients with first and schedules the next tier for the next appointment, but added, “honestly, over the next 2 years we’re going to be playing catch-up.”

At the same time, the CDC has estimated that 45% of U.S. adults are at increased risk for complications from COVID-19 because of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, or cancer. Rates ranged from 19.8% for people 18-29 years old to 80.7% for people over 80 years of age.

Long COVID could overwhelm existing health care capacity

Primary care physicians are also having to diagnose sometimes “invisible” symptoms after people have recovered from acute COVID-19 infection. Diagnosing takes intent listening to patients who describe symptoms that tests can’t confirm.

As this news organization has previously reported, half of COVID-19 survivors report postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) lasting longer than 6 months.

“These long-term PASC effects occur on a scale that could overwhelm existing health care capacity, particularly in low- and middle-income countries,” the authors wrote.

Anxiety, depression ‘have gone off the charts’

Danielle Loeb, MD, MPH, associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Colorado in Denver, who studies complexity in primary care, said in the wake of COVID-19, more patients have developed “new, serious anxiety.”

“That got extremely exacerbated during the pandemic. Anxiety and depression have gone off the charts,” said Dr. Loeb, who prefers the pronoun “they.”

Dr. Loeb cares for a large number of transgender patients. As offices reopen, some patients are having trouble reintegrating into the workplace and resuming social contacts. The primary care doctor says appointments can get longer because of the need to complete tasks, such as filling out forms for Family Medical Leave Act for those not yet ready to return to work.

COVID-19–related fears are keeping many patients from coming into the office, Dr. Loeb said, either from fear of exposure or because they have mental health issues that keep them from feeling safe leaving the house.

“That really affects my ability to care for them,” they said.

Loss of employment in the pandemic or fear of job loss and subsequent changing of insurance has complicated primary care in terms of treatment and administrative tasks, according to Dr. Loeb.

To help treat patients with acute mental health issues and manage other patients, Dr. Loeb’s practice has brought in a social worker and a therapist.

Team-based care is key in the survival of primary care practices, though providing that is difficult in the smaller clinics because of the critical mass of patients needed to make it viable, they said.

“It’s the only answer. It’s the only way you don’t drown,” Dr. Loeb added. “I’m not drowning, and I credit that to my clinic having the help to support the mental health piece of things.”

Rethinking workflow

Tricia McGinnis, MPP, MPH, executive vice president of the nonprofit Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) says complexity has forced rethinking workflow.

“A lot of the trends we’re seeing in primary care were there pre-COVID, but COVID has exacerbated those trends,” she said in an interview.

“The good news ... is that it was already becoming clear that primary care needed to provide basic mental health services and integrate with behavioral health. It had also become clear that effective primary care needed to address social issues that keep patients from accessing health care,” she said.

Expanding care teams, as Dr. Loeb mentioned, is a key strategy, according to Ms. McGinnis. Potential teams would include the clinical staff, but also social workers and community health workers – people who come from the community primary care is serving who can help build trust with patients and connect the patient to the primary care team.

“There’s a lot that needs to happen that the clinician doesn’t need to do,” she said.

Telehealth can be a big factor in coordinating the team, Ms. McGinnis added.

“It’s thinking less about who’s doing the work, but more about the work that needs to be done to keep people healthy. Then let’s think about the type of workers best suited to perform those tasks,” she said.

As for reimbursing more complex care, population-based, up-front capitated payments linked to high-quality care and better outcomes will need to replace fee-for-service models, according to Ms. McGinnis.

That will provide reliable incomes for primary care offices, but also flexibility in how each patient with different levels of complexity is managed, she said.

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Fincher, Dr. Loeb, and Ms. McGinnis have no relevant financial relationships.

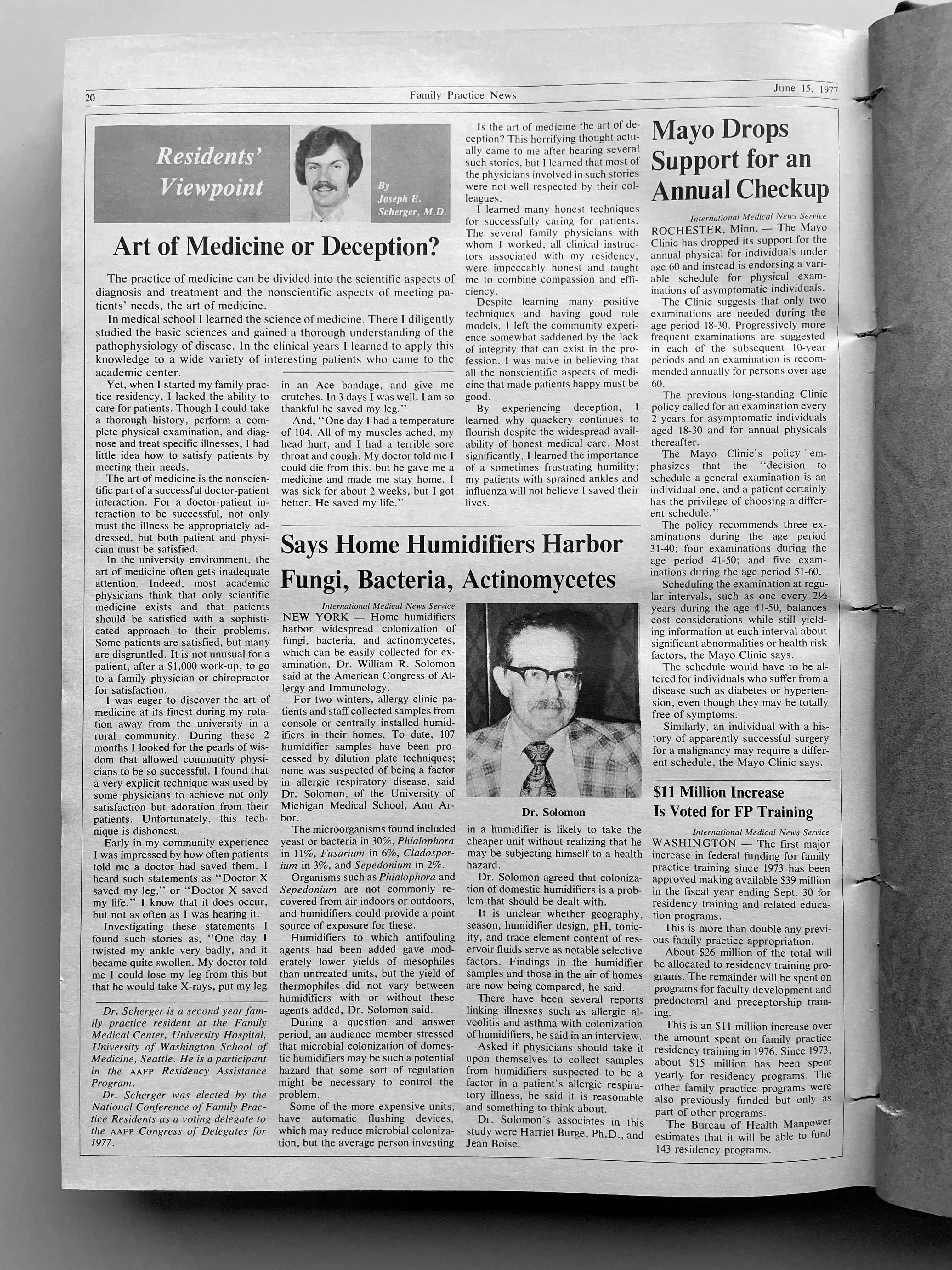

‘Residents’ Viewpoint’ revisited

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

We are currently republishing an installment of this column as part of our continuing celebration of Family Practice News’s 50th anniversary.

Bruce A. Bagley, MD, wrote the first batch of these columns, when he was chief resident in family medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Syracuse, N.Y. Joseph E. Scherger, MD, was the second writer for Family Practice News’s monthly “Residents’ Viewpoint.” At the time Dr. Scherger became a columnist, he was a 26-year-old, 2nd-year family practice resident at the Family Medical Center, University Hospital, University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Scherger’s first column was published on Feb. 5, 1977. We are republishing his “Residents’ Viewpoint” from June 15, 1977 (see below) and a new column by Victoria Persampiere, DO, who is currently a 2nd-year resident in the family medicine program at Abington Jefferson Health. (See “My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021” after Dr. Scherger’s column.).

We hope you will enjoy comparing and contrasting the experiences of a resident practicing family medicine today to those of a resident practicing family medicine nearly 4½ decades ago.To learn about Dr. Scherger’s current practice and long career, you can read his profile on the cover of the September 2021 issue of Family Practice News or on MDedge.com/FamilyMedicine in our “Family Practice News 50th Anniversary” section.

Art of medicine or deception?

Originally published in Family Practice News on June 15, 1977.

In medical school I learned the science of medicine. There I diligently studied the basic sciences and gained a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of disease. In the clinical years I learned to apply this knowledge to a wide variety of interesting patients who came to the academic center.

Yet, when I started my family practice residency, I lacked the ability to care for patients. Though I could take a thorough history, perform a complete physical examination, and diagnose and treat specific illnesses, I had little idea how to satisfy patients by meeting their needs.

The art of medicine is the nonscientific part of a successful doctor-patient interaction. For a doctor-patient interaction to be successful, not only must the illness be appropriately addressed, but both patient and physician must be satisfied.

In the university environment, the art of medicine often gets inadequate attention. Indeed, most academic physicians think that only scientific medicine exists and that patients should be satisfied with a sophisticated approach to their problems. Some patients are satisfied, but many are disgruntled. It is not unusual for a patient, after a $1,000 work-up, to go to a family physician or chiropractor for satisfaction.

I was eager to discover the art of medicine at its finest during my rotation away from the university in a rural community. During these 2 months I looked for the pearls of wisdom that allowed community physicians to be so successful. I found that a very explicit technique was used by some physicians to achieve not only satisfaction but adoration from their patients. Unfortunately, this technique is dishonest.

Early in my community experience I was impressed by how often patients told me a doctor had saved them. I heard such statements as “Dr. X saved my leg,” or “Dr. X saved my life.” I know that it does occur, but not as often as I was hearing it.

Investigating these statements I found such stories as, “One day l twisted my ankle very badly, and it became quite swollen. My doctor told me 1 could lose my leg from this but that he would take x-rays, put my leg in an Ace bandage, and give me crutches. In 3 days I was well. I am so thankful he saved my leg.”

And, “One day I had a temperature of 104. All of my muscles ached, my head hurt, and I had a terrible sore throat and cough. My doctor told me l could die from this, but he gave me a medicine and made me stay home. I was sick for about 2 weeks, but I got better. He saved my life.”

Is the art of medicine the art of deception? This horrifying thought actually came to me after hearing several such stories, but I learned that most of the physicians involved in such stories were not well respected by their colleagues.

I learned many honest techniques for successfully caring for patients. The several family physicians with whom I worked, all clinical instructors associated with my residency, were impeccably honest and taught me to combine compassion and efficiency.

Despite learning many positive techniques and having good role models, I left the community experience somewhat saddened by the lack of integrity that can exist in the profession. I was naive in believing that all the nonscientific aspects of medicine that made patients happy must be good.

By experiencing deception, I learned why quackery continues to flourish despite the widespread availability of honest medical care. Most significantly, I learned the importance of a sometimes frustrating humility; my patients with sprained ankles and influenza will not believe I saved their lives.

My experience as a family medicine resident in 2021

I did not get a medical school graduation; I was one of the many thousands of newly graduated students who simply left their 4th-year rotation sites one chilly day in March 2020 and just never went back. My medical school education didn’t end with me walking triumphantly across the stage – a first-generation college student finally achieving the greatest dream in her life. Instead, it ended with a Zoom “graduation” and a cross-country move from Georgia to Pennsylvania amidst the greatest pandemic in recent memory. To say my impostor syndrome was bad would be an understatement.

Residency in the COVID-19 era

The joy and the draw to family medicine for me has always been the broad scope of conditions that we see and treat. From day 1, however, much of my residency has been devoted to one very small subset of patients – those with COVID-19. At one point, our hospital was so strained that our family medicine program had to run a second inpatient service alongside our usual five-resident service team just to provide care to everybody. Patients were in the hallways. The ER was packed to the gills. We were sleepless, terrified, unvaccinated, and desperate to help our patients survive a disease that was incompletely understood, with very few tools in our toolbox to combat it.

I distinctly remember sitting in the workroom with a coresident of mine, our faces seemingly permanently lined from wearing N95s all shift, and saying to him, “I worry I will be a bad family medicine physician. I worry I haven’t seen enough, other than COVID.” It was midway through my intern year; the days were short, so I was driving to and from the hospital in chilly darkness. My patients, like many around the country, were doing poorly. Vaccines seemed like a promise too good to be true. Worst of all: Those of us who were interns, who had no triumphant podium moment to end our medical school education, were suffering with an intense sense of impostor syndrome, which was strengthened by every “there is nothing else we can offer your loved one at this time” conversation we had. My apprehension about not having seen a wider breadth of medicine during my training is a sentiment still widely shared by COVID-era residents.

Luckily, my coresident was supportive.

“We’re going to be great family medicine physicians,” he said. “We’re learning the hard stuff – the bread and butter of FM – up-front. You’ll see.”

In some ways, I think he was right. Clinical skills, empathy, humility, and forging strong relationships are at the center of every family medicine physician’s heart; my generation has had to learn these skills early and under pressure. Sometimes, there are no answers. Sometimes, the best thing a family doctor can do for a patient is to hear them, understand them, and hold their hand.

‘We watched Cinderella together’

Shortly after that conversation with my coresident, I had a particular case which moved me. This gentleman with intellectual disability and COVID had been declining steadily since his admission to the hospital. He was isolated from everybody he knew and loved, but it did not dampen his spirits. He was cheerful to every person who entered his room, clad in their shrouds of PPE, which more often than not felt more like mourning garb than protective wear. I remember very little about this patient’s clinical picture – the COVID, the superimposed pneumonia, the repeated intubations. What I do remember is he loved the Disney classic Cinderella. I knew this because I developed a very close relationship with his family during the course of his hospitalization. Amidst the torrential onslaught of patients, I made sure to call families every day – not because I wanted to, but because my mentors and attendings and coresidents had all drilled into me from day 1 that we are family medicine, and a large part of our role is to advocate for our patients, and to communicate with their loved ones. So I called. I learned a lot about him; his likes, his dislikes, his close bond with his siblings, and of course his lifelong love for Cinderella. On the last week of my ICU rotation, my patient passed peacefully. His nurse and I were bedside. We held his hand. We told him his family loved him. We watched Cinderella together on an iPad encased in protective plastic.

My next rotation was an outpatient one and it looked more like the “bread and butter” of family medicine. But as I whisked in and out of patient rooms, attending to patients with diabetes, with depression, with pain, I could not stop thinking about my hospitalized patients who my coresidents had assumed care of. Each exam room I entered, I rather morbidly thought “this patient could be next on our hospital service.” Without realizing it, I made more of an effort to get to know each patient holistically. I learned who they were as people. I found myself writing small, medically low-yield details in the chart: “Margaret loves to sing in her church choir;” “Katherine is a self-published author.”

I learned from my attendings. As I sat at the precepting table with them, observing their conversations about patients, their collective decades of experience were apparent.

“I’ve been seeing this patient every few weeks since I was a resident,” said one of my attendings.

“I don’t even see my parents that often,” I thought.

The depth of her relationship with, understanding of, and compassion for this patient struck me deeply. This was why I went into family medicine. My attending knew her patients; they were not faceless unknowns in a hospital gown to her. She would have known to play Cinderella for them in the end.

This is a unique time for trainees. We have been challenged, terrified, overwhelmed, and heartbroken. But at no point have we been isolated. We’ve had the generations of doctors before us to lead the way, to teach us the “hard stuff.” We’ve had senior residents to lean on, who have taken us aside and told us, “I can do the goals-of-care talk today; you need a break.” While the plague seems to have passed over our hospital for now, it has left behind a class of family medicine residents who are proud to carry on our specialty’s long tradition of compassionate, empathetic, lifelong care. “We care for all life stages, from cradle to grave,” says every family medicine physician.

My class, for better or for worse, has cared more often for patients in the twilight of their lives, and while it has been hard, I believe it has made us all better doctors. Now, when I hold a newborn in my arms for a well-child check, I am exceptionally grateful – for the opportunities I have been given, for new beginnings amidst so much sadness, and for the great privilege of being a family medicine physician. ■

Dr. Persampiere is a second-year resident in the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Jefferson Health. You can contact her directly at [email protected] or via [email protected].

Ivermectin–COVID-19 study retracted; authors blame file mix-up

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

Feds launch COVID-19 worker vaccine mandates

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Biden administration on Nov. 4 unveiled its rule to require most of the country’s larger employers to mandate workers be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but set a Jan. 4 deadline, avoiding the busy holiday season.

The White House also shifted the time lines for earlier mandates applying to federal workers and contractors to Jan. 4. And the same deadline applies to a new separate rule for health care workers.

The new rules are meant to preempt “any inconsistent state or local laws,” including bans and limits on employers’ authority to require vaccination, masks, or testing, the White House said in a statement.

The rule on employers from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration will apply to organizations with 100 or more employees. These employers will need to make sure each worker is fully vaccinated or tests for COVID-19 on at least a weekly basis. The OSHA rule will also require that employers provide paid time for employees to get vaccinated and ensure that all unvaccinated workers wear a face mask in the workplace. This rule will cover 84 million employees. The OSHA rule will not apply to workplaces covered by either the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services rule or the federal contractor vaccination requirement

“The virus will not go away by itself, or because we wish it away: We have to act,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “Vaccination is the single best pathway out of this pandemic.”

Mandates were not the preferred route to managing the pandemic, he said.

“Too many people remain unvaccinated for us to get out of this pandemic for good,” he said. “So I instituted requirements – and they are working.”

The White House said 70% percent of U.S. adults are now fully vaccinated – up from less than 1% when Mr. Biden took office in January.

The CMS vaccine rule is meant to cover more than 17 million workers and about 76,000 medical care sites, including hospitals, ambulatory surgery centers, nursing homes, dialysis facilities, home health agencies, and long-term care facilities. The rule will apply to employees whether their positions involve patient care or not.

Unlike the OSHA mandate, the one for health care workers will not offer the option of frequent COVID-19 testing instead of vaccination. There is a “higher bar” for health care workers, given their role in treating patients, so the mandate allows only for vaccination or limited exemptions, a senior administration official said on Nov. 3 during a call with reporters.

The CMS rule includes a “range of remedies,” including penalties and denial of payment for health care facilities that fail to meet the vaccine mandate. CMS could theoretically cut off hospitals and other medical organizations for failure to comply, but that would be a “last resort,” a senior administration official said. CMS will instead work with health care facilities to help them comply with the federal rule on vaccination of medical workers.

The new CMS rules apply only to Medicare- and Medicaid-certified centers and organizations. The rule does not directly apply to other health care entities, such as doctor’s offices, that are not regulated by CMS.

“Most states have separate licensing requirements for health care staff and health care providers that would be applicable to physician office staff and other staff in small health care entities that are not subject to vaccination requirements under this IFC,” CMS said in the rule.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Q&A: Meeting the challenge of giving COVID vaccines to younger kids

This news organization spoke to several pediatric experts to get answers.

More than 6 million children and adolescents (up to age 18 years) in the United States have been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Children represent about 17% of all cases, and an estimated 0.1%-2% of infected children end up hospitalized, according to Oct. 28 data from the American Academy of Pediatrics.