User login

Children and COVID: New cases up again after dropping for 8 weeks

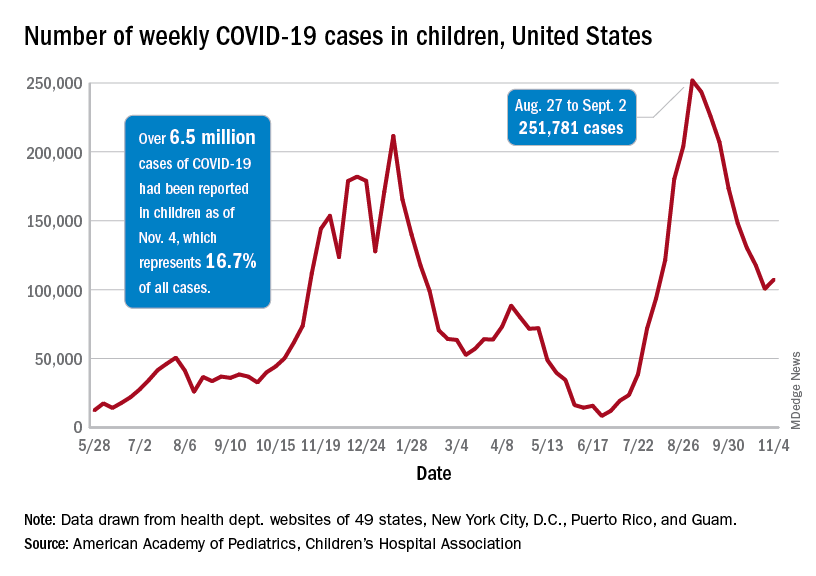

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

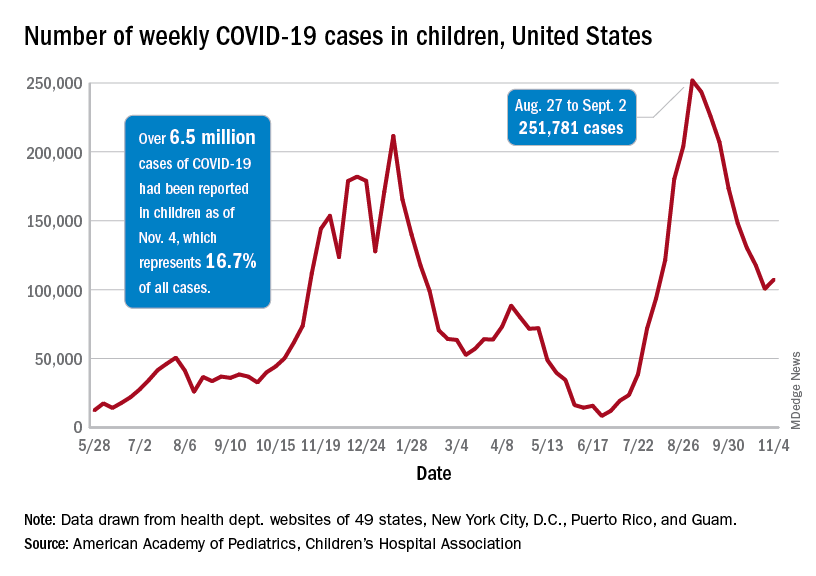

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

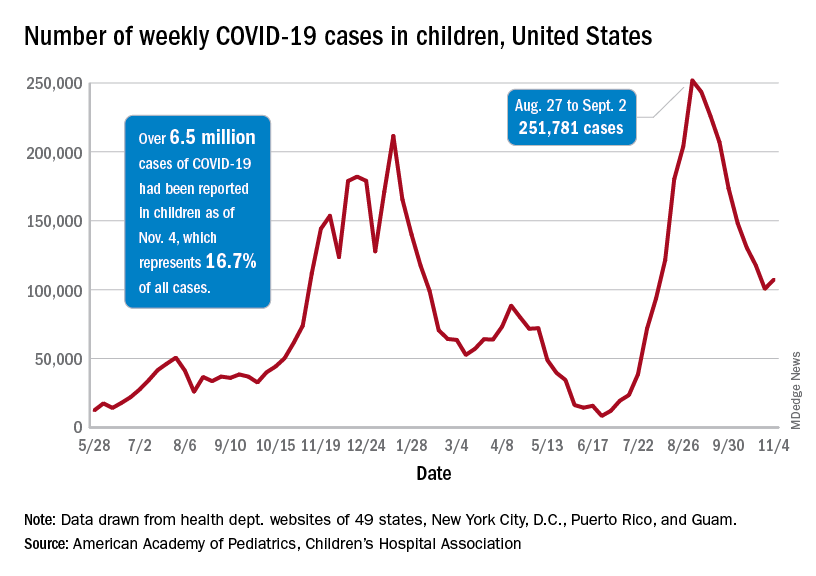

As children aged 5-11 years began to receive the first officially approved doses of COVID-19 vaccine, new pediatric cases increased after 8 consecutive weeks of declines, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Weekly cases peaked at almost 252,000 in early September and then dropped for 8 straight weeks before this latest rise, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report, which is based on data reported by 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The end of that 8-week drop, unfortunately, allowed another streak to continue: New cases have been above 100,000 for 13 consecutive weeks, the AAP and CHA noted.

The cumulative COVID count in children as of Nov. 4 was 6.5 million, the AAP/CHA said, although that figure does not fully cover Alabama, Nebraska, and Texas, which stopped public reporting over the summer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with input from all states and territories, puts the total through Nov. 8 at almost 5.7 million cases in children under 18 years of age, while most states define a child as someone aged 0-19 years.

As for the newest group of vaccinees, the CDC said that “updated vaccination data for 5-11 year-olds will be added to COVID Data Tracker later this week,” meaning the week of Nov. 7-13. Currently available data, however, show that almost 157,000 children under age 12 initiated vaccination in the 14 days ending Nov. 8, which was more than those aged 12-15 and 16-17 years combined (127,000).

Among those older groups, the CDC reports that 57.1% of 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose and 47.9% are fully vaccinated, while 64.0% of those aged 16-17 have gotten at least one dose and 55.2% are fully vaccinated. Altogether, about 13.9 million children under age 18 have gotten at least one dose and almost 11.6 million are fully vaccinated, according to the CDC.

Early trials underway to test mushrooms as COVID treatment

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the MACH-19 trials (the acronym for Mushrooms and Chinese Herbs for COVID-19) after researchers applied for approval in April.

The first two phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have begun at UCLA and the University of California San Diego to treat COVID-19 patients quarantining at home with mild to moderate symptoms. A third trial is investigating the use of medicinal mushrooms as an adjuvant to COVID-19 vaccines.

The researchers have also launched a fourth trial testing the mushrooms against placebo as an adjunct to a COVID booster shot. It looks at the effect in people who have comorbidities that would reduce their vaccine response. An article in JAMA described the trials.

The two mushroom varieties being tested — turkey tail and agarikon — are available as over-the-counter supplements, according to the report. They are a separate class from hallucinogenic or “magic” mushrooms being tested for other uses in medicine.

“They are not even as psychoactive as a cup of tea,” Gordon Saxe, MD, PhD, MPH, principal investigator for the MACH-19 trials, told this news organization.

For each of the MACH-19 treatment trials, researchers plan to recruit 66 people who are quarantined at home with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms. Participants will be randomly assigned either to receive the mushroom combination, the Chinese herbs, or a placebo for 2 weeks, according to the JAMA paper.

D. Craig Hopp, PhD, deputy director of the division of extramural research at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), told JAMA in an interview that he was “mildly concerned” about using mushrooms to treat people with active SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“We know that a cytokine storm poses the greatest risk of COVID mortality, not the virus itself,” Dr. Hopp said. “The danger is that an immune-stimulating agent like mushrooms might supercharge an individual’s immune response, leading to a cytokine storm.”

Stephen Wilson, PhD, an immunologist who consulted on the trials when he was chief operating officer of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, says in the JAMA article that a cytokine storm is unlikely for these patients because the mushroom components “don’t mimic inflammatory cytokines.” Dr. Wilson is now chief innovations officer at Statera Biopharma.

“We think the mushrooms increase the number of immunologic opportunities to better see and respond to a specific threat. In the doses used, the mushrooms perturb the immune system in a good way but fall far short of driving hyper or sustained inflammation,” Dr. Wilson said.

Dr. Saxe said the FDA process was extensive and rigorous and FDA investigators also asked about potential cytokine storms before approving the trials. Cytokine storm is not an issue with a healthy response, Dr. Saxe pointed out. It’s a response that’s not balanced or modulated.

“Mushrooms are immunomodulatory,” he said. “In some ways they very specifically enhance immunity. In other ways they calm down overimmunity.” Dr. Saxe noted that they did a sentinel study for the storm potential “and we didn’t see any evidence for it.”

“Not a crazy concept”

Dr. Saxe pointed out that one of the mushrooms in the combo they use — agarikon — was used to treat pulmonary infections 2,300 years ago.

“Hippocrates, the father of western medicine, used mushrooms,” he said. “Penicillin comes from fungi. It’s not a crazy concept. Most people who oppose this or are skeptics — to some extent, it’s a lack of information.”

Dr. Saxe explained that there are receptors on human cells that bind specific mushroom polysaccharides.

“There’s a hand-in-glove fit there,” Dr. Saxe said, and that’s one way mushrooms can modulate immune cell behavior, which could have an effect against SARS-CoV-2.

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not part of the study, told this news organization that he wasn’t surprised the FDA approved moving forward with the trials.

“As long as you can demonstrate that there is a rationale for doing the trial and that you have some safety data or a plan to collect safety data, they are fairly liberal about doing early-phase studies. It would be a much different issue, I think, if they were proposing to do a study for actual licensing or approval of a drug,” Dr. Kuritzkes said.

As yet unanswered, he noted, is which component of the mushrooms or herbs is having the effect. It will be a challenge, he said, to know from one batch of the compound to the next that you have the same amount of material and that it’s going to have the same potency among lots.

Another challenge is how the mushrooms and herbs might interact with other therapies, Dr. Kuritzkes said.

He gave the example of St. John’s Wort, which has been problematic in HIV treatment.

“If someone is on certain HIV medicines and they also are taking St. John’s Wort, they basically are causing the liver to eat up the HIV drug and they don’t get adequate levels of the drug,” he said.

Though there are many challenges ahead, Dr. Kuritzkes acknowledged, but added that “this is a great starting point.”

He, too, pointed out that many traditional medicines were discovered from plants.

“The most famous of these is quinine, which came from cinchona bark that was used to treat malaria.” Dr. Kuritzkes said. Digitalis, often used to treat heart failure, comes from the fox glove plant, he added.

He said it’s important to remember that “people shouldn’t be seeking experimental therapies in place of proven therapies, they should be thinking of them in addition to proven therapies.»

A co-author reports an investment in the dietary supplement company Mycomedica Life Sciences, for which he also serves as an unpaid scientific adviser. Another co-author is a medical consultant for Evergreen Herbs and Medical Supplies. Dr. Hopp, Dr. Saxe, and Dr. Wilson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kuritzkes consults for Merck, Gilead, and GlaxoSmithKline.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the MACH-19 trials (the acronym for Mushrooms and Chinese Herbs for COVID-19) after researchers applied for approval in April.

The first two phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have begun at UCLA and the University of California San Diego to treat COVID-19 patients quarantining at home with mild to moderate symptoms. A third trial is investigating the use of medicinal mushrooms as an adjuvant to COVID-19 vaccines.

The researchers have also launched a fourth trial testing the mushrooms against placebo as an adjunct to a COVID booster shot. It looks at the effect in people who have comorbidities that would reduce their vaccine response. An article in JAMA described the trials.

The two mushroom varieties being tested — turkey tail and agarikon — are available as over-the-counter supplements, according to the report. They are a separate class from hallucinogenic or “magic” mushrooms being tested for other uses in medicine.

“They are not even as psychoactive as a cup of tea,” Gordon Saxe, MD, PhD, MPH, principal investigator for the MACH-19 trials, told this news organization.

For each of the MACH-19 treatment trials, researchers plan to recruit 66 people who are quarantined at home with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms. Participants will be randomly assigned either to receive the mushroom combination, the Chinese herbs, or a placebo for 2 weeks, according to the JAMA paper.

D. Craig Hopp, PhD, deputy director of the division of extramural research at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), told JAMA in an interview that he was “mildly concerned” about using mushrooms to treat people with active SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“We know that a cytokine storm poses the greatest risk of COVID mortality, not the virus itself,” Dr. Hopp said. “The danger is that an immune-stimulating agent like mushrooms might supercharge an individual’s immune response, leading to a cytokine storm.”

Stephen Wilson, PhD, an immunologist who consulted on the trials when he was chief operating officer of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, says in the JAMA article that a cytokine storm is unlikely for these patients because the mushroom components “don’t mimic inflammatory cytokines.” Dr. Wilson is now chief innovations officer at Statera Biopharma.

“We think the mushrooms increase the number of immunologic opportunities to better see and respond to a specific threat. In the doses used, the mushrooms perturb the immune system in a good way but fall far short of driving hyper or sustained inflammation,” Dr. Wilson said.

Dr. Saxe said the FDA process was extensive and rigorous and FDA investigators also asked about potential cytokine storms before approving the trials. Cytokine storm is not an issue with a healthy response, Dr. Saxe pointed out. It’s a response that’s not balanced or modulated.

“Mushrooms are immunomodulatory,” he said. “In some ways they very specifically enhance immunity. In other ways they calm down overimmunity.” Dr. Saxe noted that they did a sentinel study for the storm potential “and we didn’t see any evidence for it.”

“Not a crazy concept”

Dr. Saxe pointed out that one of the mushrooms in the combo they use — agarikon — was used to treat pulmonary infections 2,300 years ago.

“Hippocrates, the father of western medicine, used mushrooms,” he said. “Penicillin comes from fungi. It’s not a crazy concept. Most people who oppose this or are skeptics — to some extent, it’s a lack of information.”

Dr. Saxe explained that there are receptors on human cells that bind specific mushroom polysaccharides.

“There’s a hand-in-glove fit there,” Dr. Saxe said, and that’s one way mushrooms can modulate immune cell behavior, which could have an effect against SARS-CoV-2.

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not part of the study, told this news organization that he wasn’t surprised the FDA approved moving forward with the trials.

“As long as you can demonstrate that there is a rationale for doing the trial and that you have some safety data or a plan to collect safety data, they are fairly liberal about doing early-phase studies. It would be a much different issue, I think, if they were proposing to do a study for actual licensing or approval of a drug,” Dr. Kuritzkes said.

As yet unanswered, he noted, is which component of the mushrooms or herbs is having the effect. It will be a challenge, he said, to know from one batch of the compound to the next that you have the same amount of material and that it’s going to have the same potency among lots.

Another challenge is how the mushrooms and herbs might interact with other therapies, Dr. Kuritzkes said.

He gave the example of St. John’s Wort, which has been problematic in HIV treatment.

“If someone is on certain HIV medicines and they also are taking St. John’s Wort, they basically are causing the liver to eat up the HIV drug and they don’t get adequate levels of the drug,” he said.

Though there are many challenges ahead, Dr. Kuritzkes acknowledged, but added that “this is a great starting point.”

He, too, pointed out that many traditional medicines were discovered from plants.

“The most famous of these is quinine, which came from cinchona bark that was used to treat malaria.” Dr. Kuritzkes said. Digitalis, often used to treat heart failure, comes from the fox glove plant, he added.

He said it’s important to remember that “people shouldn’t be seeking experimental therapies in place of proven therapies, they should be thinking of them in addition to proven therapies.»

A co-author reports an investment in the dietary supplement company Mycomedica Life Sciences, for which he also serves as an unpaid scientific adviser. Another co-author is a medical consultant for Evergreen Herbs and Medical Supplies. Dr. Hopp, Dr. Saxe, and Dr. Wilson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kuritzkes consults for Merck, Gilead, and GlaxoSmithKline.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the MACH-19 trials (the acronym for Mushrooms and Chinese Herbs for COVID-19) after researchers applied for approval in April.

The first two phase 1 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have begun at UCLA and the University of California San Diego to treat COVID-19 patients quarantining at home with mild to moderate symptoms. A third trial is investigating the use of medicinal mushrooms as an adjuvant to COVID-19 vaccines.

The researchers have also launched a fourth trial testing the mushrooms against placebo as an adjunct to a COVID booster shot. It looks at the effect in people who have comorbidities that would reduce their vaccine response. An article in JAMA described the trials.

The two mushroom varieties being tested — turkey tail and agarikon — are available as over-the-counter supplements, according to the report. They are a separate class from hallucinogenic or “magic” mushrooms being tested for other uses in medicine.

“They are not even as psychoactive as a cup of tea,” Gordon Saxe, MD, PhD, MPH, principal investigator for the MACH-19 trials, told this news organization.

For each of the MACH-19 treatment trials, researchers plan to recruit 66 people who are quarantined at home with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms. Participants will be randomly assigned either to receive the mushroom combination, the Chinese herbs, or a placebo for 2 weeks, according to the JAMA paper.

D. Craig Hopp, PhD, deputy director of the division of extramural research at the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), told JAMA in an interview that he was “mildly concerned” about using mushrooms to treat people with active SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“We know that a cytokine storm poses the greatest risk of COVID mortality, not the virus itself,” Dr. Hopp said. “The danger is that an immune-stimulating agent like mushrooms might supercharge an individual’s immune response, leading to a cytokine storm.”

Stephen Wilson, PhD, an immunologist who consulted on the trials when he was chief operating officer of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, says in the JAMA article that a cytokine storm is unlikely for these patients because the mushroom components “don’t mimic inflammatory cytokines.” Dr. Wilson is now chief innovations officer at Statera Biopharma.

“We think the mushrooms increase the number of immunologic opportunities to better see and respond to a specific threat. In the doses used, the mushrooms perturb the immune system in a good way but fall far short of driving hyper or sustained inflammation,” Dr. Wilson said.

Dr. Saxe said the FDA process was extensive and rigorous and FDA investigators also asked about potential cytokine storms before approving the trials. Cytokine storm is not an issue with a healthy response, Dr. Saxe pointed out. It’s a response that’s not balanced or modulated.

“Mushrooms are immunomodulatory,” he said. “In some ways they very specifically enhance immunity. In other ways they calm down overimmunity.” Dr. Saxe noted that they did a sentinel study for the storm potential “and we didn’t see any evidence for it.”

“Not a crazy concept”

Dr. Saxe pointed out that one of the mushrooms in the combo they use — agarikon — was used to treat pulmonary infections 2,300 years ago.

“Hippocrates, the father of western medicine, used mushrooms,” he said. “Penicillin comes from fungi. It’s not a crazy concept. Most people who oppose this or are skeptics — to some extent, it’s a lack of information.”

Dr. Saxe explained that there are receptors on human cells that bind specific mushroom polysaccharides.

“There’s a hand-in-glove fit there,” Dr. Saxe said, and that’s one way mushrooms can modulate immune cell behavior, which could have an effect against SARS-CoV-2.

Daniel Kuritzkes, MD, chief of the division of infectious diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who was not part of the study, told this news organization that he wasn’t surprised the FDA approved moving forward with the trials.

“As long as you can demonstrate that there is a rationale for doing the trial and that you have some safety data or a plan to collect safety data, they are fairly liberal about doing early-phase studies. It would be a much different issue, I think, if they were proposing to do a study for actual licensing or approval of a drug,” Dr. Kuritzkes said.

As yet unanswered, he noted, is which component of the mushrooms or herbs is having the effect. It will be a challenge, he said, to know from one batch of the compound to the next that you have the same amount of material and that it’s going to have the same potency among lots.

Another challenge is how the mushrooms and herbs might interact with other therapies, Dr. Kuritzkes said.

He gave the example of St. John’s Wort, which has been problematic in HIV treatment.

“If someone is on certain HIV medicines and they also are taking St. John’s Wort, they basically are causing the liver to eat up the HIV drug and they don’t get adequate levels of the drug,” he said.

Though there are many challenges ahead, Dr. Kuritzkes acknowledged, but added that “this is a great starting point.”

He, too, pointed out that many traditional medicines were discovered from plants.

“The most famous of these is quinine, which came from cinchona bark that was used to treat malaria.” Dr. Kuritzkes said. Digitalis, often used to treat heart failure, comes from the fox glove plant, he added.

He said it’s important to remember that “people shouldn’t be seeking experimental therapies in place of proven therapies, they should be thinking of them in addition to proven therapies.»

A co-author reports an investment in the dietary supplement company Mycomedica Life Sciences, for which he also serves as an unpaid scientific adviser. Another co-author is a medical consultant for Evergreen Herbs and Medical Supplies. Dr. Hopp, Dr. Saxe, and Dr. Wilson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Kuritzkes consults for Merck, Gilead, and GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM JAMA

As constituents clamor for ivermectin, Republican politicians embrace the cause

When state senators in South Carolina held two hearings in September about COVID-19 treatments, they got an earful on the benefits of ivermectin — which many of the lawmakers echoed, sharing experiences of their own loved ones.

The demands for access to the drug were loud and insistent, despite federal regulators’ recent warning against using the drug to treat COVID.

Ivermectin is a generic drug that has been used for decades to treat river blindness, scabies, and even head lice. Veterinarians also use it, in different formulations and dosages, to treat animals for parasites like worms.

At one of the South Carolina hearings, Pressley Stutts III reminded the panel that his father, a prominent GOP leader in the state, had died of COVID a month earlier. He believed ivermectin could have helped him. But doctors at the hospital wouldn’t discuss it.

“I went every bit as far as I could without getting myself thrown in jail trying to save my father’s life,” he told the panel, as lawmakers offered condolences.

“What is going on here?” he asked, with the passion in his voice growing. “My dad’s dead!”

After the pandemic began, scientists launched clinical trials to see if ivermectin could help as a treatment for COVID. Some are still ongoing. But providers in mainstream medicine have rejected it as a COVID treatment, citing the poor quality of the studies to date, and two notorious “preprint” studies that were circulated before they were peer-reviewed, and later taken off the internet because of inaccurate and flawed data.

On Aug. 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised clinicians not to use ivermectin, citing insufficient evidence of benefit and pointing out that unauthorized use had led to accidental poisonings. Vaccination, the CDC reiterated, is still the best way to avoid serious illness and death from the coronavirus.

But many Americans remain convinced ivermectin could be beneficial, and some politicians appear to be listening to them.

“If we have medications out here that are working — or seem to be working — I think it’s absolutely horrible that we’re not trying them,” said Republican state Sen. Tom Corbin in South Carolina. He questioned doctors who had come to the Statehouse to counter efforts to move ivermectin into mainstream use.

The doctors challenged the implied insult that they weren’t following best practices: “Any implication that any of us would do anything to withhold effective treatments from our patients is really insulting to our profession,” said Dr. Annie Andrews, a professor at the Medical University of South Carolina who has cared for COVID patients throughout the pandemic.

Instead of listening to the medical consensus, some politicians in states like South Carolina seem to be taking cues from doctors on the fringe. During one September hearing, state senators patched in a call from Dr. Pierre Kory.

Last year, Dr. Kory started a nonprofit called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, which promotes ivermectin. He said he’s not making money by prescribing the drug, though the nonprofit does solicit donations and has not yet filed required financial documents with the IRS.

Dr. Kory acknowledged his medical opinions have landed him on “an island.”

He first testified about ivermectin to a U.S. Senate committee in December. That video went viral. Although it was taken down by YouTube, his Senate testimony prompted patients across the country to ask for ivermectin when they fell ill.

By late August, outpatient prescriptions had jumped 24-fold. Calls to poison control hotlines had tripled, mostly related to people taking ivermectin formulations meant for livestock.

Dr. Kory said he has effectively lost two jobs over his views on ivermectin. At his current hospital in Wisconsin, where he runs the intensive care unit two weeks a month, managers called him to a meeting in September, where he was informed he could no longer prescribe ivermectin. He’d been giving it to “every patient with COVID,” he said.

“After the pharma-geddon that was unleashed, yeah, they shut it down,” he told the South Carolina lawmakers. “And I will tell you that many hospitals across the country had already shut it down months ago.”

Framing the ivermectin fight as a battle against faceless federal agencies and big pharmaceutical corporations appealed to Americans already suspicious of the science behind the pandemic and the approved COVID vaccines.

Dr. Kory suggests success stories with COVID treatments in other parts of the world have been suppressed to instead promote the vaccines.

In an interview with NPR, Dr. Kory said he regrets the flashpoint he helped ignite.

“I feel really bad for the patients, and I feel really bad for the doctors,” he told NPR. “Both of them — both the patients and doctors — are trapped.”

Patients are still demanding the treatment, but doctors sympathetic to their wishes are being told by their health systems not to try it.

Now conservatives in elected office are sensing political payoff if they step in to help patients get the drug. State legislatures, including those in Tennessee and Alaska, are debating various ways to increase access to ivermectin — with proposals such as shielding doctors from repercussions for prescribing it, or forcing pharmacists to fill questionable prescriptions.

The Montana State News Bureau reported that the state’s Republican attorney general dispatched a state trooper to a hospital in Helena where a politically connected patient was dying of COVID. Her family was asking for ivermectin.

In a statement, St. Peter’s Hospital said doctors and nurses were “harassed and threatened by three public officials.”

“These officials have no medical training or experience, yet they were insisting our providers give treatments for COVID-19 that are not authorized, clinically approved, or within the guidelines established by the FDA and the CDC,” the statement added.

On Oct. 14, the Republican attorney general in Nebraska addressed the controversy, issuing a nearly 50-page legal opinion arguing that doctors who consider the “off-label” use of ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine for COVID are acting within the parameters of their state medical licenses, as long as the physician obtains appropriate informed consent from a patient.

Some patients have filed lawsuits to obtain ivermectin, with mixed success. A patient in Illinois was denied. But other hospitals, including one in Ohio, have been forced to administer the drug against the objections of their physicians.

Even as they gain powerful political supporters, some ivermectin fans say they’re now avoiding the health care system — because they’ve lost faith in it.

Lesa Berry, of Richmond, Va., had a friend who died earlier this year of COVID. The doctors refused to use ivermectin, despite requests from Ms. Berry and the patient’s daughter.

They know better now, she said.

“My first attempt would have been to keep her out of the hospital,” Ms. Berry said. “Because right now when you go to the hospital, they only give you what’s on the CDC protocol.”

Ms. Berry and her husband have purchased their own supply of ivermectin, which they keep at home.

This story is from a partnership that includes NPR, Nashville Public Radio and KHN. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

When state senators in South Carolina held two hearings in September about COVID-19 treatments, they got an earful on the benefits of ivermectin — which many of the lawmakers echoed, sharing experiences of their own loved ones.

The demands for access to the drug were loud and insistent, despite federal regulators’ recent warning against using the drug to treat COVID.

Ivermectin is a generic drug that has been used for decades to treat river blindness, scabies, and even head lice. Veterinarians also use it, in different formulations and dosages, to treat animals for parasites like worms.

At one of the South Carolina hearings, Pressley Stutts III reminded the panel that his father, a prominent GOP leader in the state, had died of COVID a month earlier. He believed ivermectin could have helped him. But doctors at the hospital wouldn’t discuss it.

“I went every bit as far as I could without getting myself thrown in jail trying to save my father’s life,” he told the panel, as lawmakers offered condolences.

“What is going on here?” he asked, with the passion in his voice growing. “My dad’s dead!”

After the pandemic began, scientists launched clinical trials to see if ivermectin could help as a treatment for COVID. Some are still ongoing. But providers in mainstream medicine have rejected it as a COVID treatment, citing the poor quality of the studies to date, and two notorious “preprint” studies that were circulated before they were peer-reviewed, and later taken off the internet because of inaccurate and flawed data.

On Aug. 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised clinicians not to use ivermectin, citing insufficient evidence of benefit and pointing out that unauthorized use had led to accidental poisonings. Vaccination, the CDC reiterated, is still the best way to avoid serious illness and death from the coronavirus.

But many Americans remain convinced ivermectin could be beneficial, and some politicians appear to be listening to them.

“If we have medications out here that are working — or seem to be working — I think it’s absolutely horrible that we’re not trying them,” said Republican state Sen. Tom Corbin in South Carolina. He questioned doctors who had come to the Statehouse to counter efforts to move ivermectin into mainstream use.

The doctors challenged the implied insult that they weren’t following best practices: “Any implication that any of us would do anything to withhold effective treatments from our patients is really insulting to our profession,” said Dr. Annie Andrews, a professor at the Medical University of South Carolina who has cared for COVID patients throughout the pandemic.

Instead of listening to the medical consensus, some politicians in states like South Carolina seem to be taking cues from doctors on the fringe. During one September hearing, state senators patched in a call from Dr. Pierre Kory.

Last year, Dr. Kory started a nonprofit called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, which promotes ivermectin. He said he’s not making money by prescribing the drug, though the nonprofit does solicit donations and has not yet filed required financial documents with the IRS.

Dr. Kory acknowledged his medical opinions have landed him on “an island.”

He first testified about ivermectin to a U.S. Senate committee in December. That video went viral. Although it was taken down by YouTube, his Senate testimony prompted patients across the country to ask for ivermectin when they fell ill.

By late August, outpatient prescriptions had jumped 24-fold. Calls to poison control hotlines had tripled, mostly related to people taking ivermectin formulations meant for livestock.

Dr. Kory said he has effectively lost two jobs over his views on ivermectin. At his current hospital in Wisconsin, where he runs the intensive care unit two weeks a month, managers called him to a meeting in September, where he was informed he could no longer prescribe ivermectin. He’d been giving it to “every patient with COVID,” he said.

“After the pharma-geddon that was unleashed, yeah, they shut it down,” he told the South Carolina lawmakers. “And I will tell you that many hospitals across the country had already shut it down months ago.”

Framing the ivermectin fight as a battle against faceless federal agencies and big pharmaceutical corporations appealed to Americans already suspicious of the science behind the pandemic and the approved COVID vaccines.

Dr. Kory suggests success stories with COVID treatments in other parts of the world have been suppressed to instead promote the vaccines.

In an interview with NPR, Dr. Kory said he regrets the flashpoint he helped ignite.

“I feel really bad for the patients, and I feel really bad for the doctors,” he told NPR. “Both of them — both the patients and doctors — are trapped.”

Patients are still demanding the treatment, but doctors sympathetic to their wishes are being told by their health systems not to try it.

Now conservatives in elected office are sensing political payoff if they step in to help patients get the drug. State legislatures, including those in Tennessee and Alaska, are debating various ways to increase access to ivermectin — with proposals such as shielding doctors from repercussions for prescribing it, or forcing pharmacists to fill questionable prescriptions.

The Montana State News Bureau reported that the state’s Republican attorney general dispatched a state trooper to a hospital in Helena where a politically connected patient was dying of COVID. Her family was asking for ivermectin.

In a statement, St. Peter’s Hospital said doctors and nurses were “harassed and threatened by three public officials.”

“These officials have no medical training or experience, yet they were insisting our providers give treatments for COVID-19 that are not authorized, clinically approved, or within the guidelines established by the FDA and the CDC,” the statement added.

On Oct. 14, the Republican attorney general in Nebraska addressed the controversy, issuing a nearly 50-page legal opinion arguing that doctors who consider the “off-label” use of ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine for COVID are acting within the parameters of their state medical licenses, as long as the physician obtains appropriate informed consent from a patient.

Some patients have filed lawsuits to obtain ivermectin, with mixed success. A patient in Illinois was denied. But other hospitals, including one in Ohio, have been forced to administer the drug against the objections of their physicians.

Even as they gain powerful political supporters, some ivermectin fans say they’re now avoiding the health care system — because they’ve lost faith in it.

Lesa Berry, of Richmond, Va., had a friend who died earlier this year of COVID. The doctors refused to use ivermectin, despite requests from Ms. Berry and the patient’s daughter.

They know better now, she said.

“My first attempt would have been to keep her out of the hospital,” Ms. Berry said. “Because right now when you go to the hospital, they only give you what’s on the CDC protocol.”

Ms. Berry and her husband have purchased their own supply of ivermectin, which they keep at home.

This story is from a partnership that includes NPR, Nashville Public Radio and KHN. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

When state senators in South Carolina held two hearings in September about COVID-19 treatments, they got an earful on the benefits of ivermectin — which many of the lawmakers echoed, sharing experiences of their own loved ones.

The demands for access to the drug were loud and insistent, despite federal regulators’ recent warning against using the drug to treat COVID.

Ivermectin is a generic drug that has been used for decades to treat river blindness, scabies, and even head lice. Veterinarians also use it, in different formulations and dosages, to treat animals for parasites like worms.

At one of the South Carolina hearings, Pressley Stutts III reminded the panel that his father, a prominent GOP leader in the state, had died of COVID a month earlier. He believed ivermectin could have helped him. But doctors at the hospital wouldn’t discuss it.

“I went every bit as far as I could without getting myself thrown in jail trying to save my father’s life,” he told the panel, as lawmakers offered condolences.

“What is going on here?” he asked, with the passion in his voice growing. “My dad’s dead!”

After the pandemic began, scientists launched clinical trials to see if ivermectin could help as a treatment for COVID. Some are still ongoing. But providers in mainstream medicine have rejected it as a COVID treatment, citing the poor quality of the studies to date, and two notorious “preprint” studies that were circulated before they were peer-reviewed, and later taken off the internet because of inaccurate and flawed data.

On Aug. 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised clinicians not to use ivermectin, citing insufficient evidence of benefit and pointing out that unauthorized use had led to accidental poisonings. Vaccination, the CDC reiterated, is still the best way to avoid serious illness and death from the coronavirus.

But many Americans remain convinced ivermectin could be beneficial, and some politicians appear to be listening to them.

“If we have medications out here that are working — or seem to be working — I think it’s absolutely horrible that we’re not trying them,” said Republican state Sen. Tom Corbin in South Carolina. He questioned doctors who had come to the Statehouse to counter efforts to move ivermectin into mainstream use.

The doctors challenged the implied insult that they weren’t following best practices: “Any implication that any of us would do anything to withhold effective treatments from our patients is really insulting to our profession,” said Dr. Annie Andrews, a professor at the Medical University of South Carolina who has cared for COVID patients throughout the pandemic.

Instead of listening to the medical consensus, some politicians in states like South Carolina seem to be taking cues from doctors on the fringe. During one September hearing, state senators patched in a call from Dr. Pierre Kory.

Last year, Dr. Kory started a nonprofit called the Front Line COVID-19 Critical Care Alliance, which promotes ivermectin. He said he’s not making money by prescribing the drug, though the nonprofit does solicit donations and has not yet filed required financial documents with the IRS.

Dr. Kory acknowledged his medical opinions have landed him on “an island.”

He first testified about ivermectin to a U.S. Senate committee in December. That video went viral. Although it was taken down by YouTube, his Senate testimony prompted patients across the country to ask for ivermectin when they fell ill.

By late August, outpatient prescriptions had jumped 24-fold. Calls to poison control hotlines had tripled, mostly related to people taking ivermectin formulations meant for livestock.

Dr. Kory said he has effectively lost two jobs over his views on ivermectin. At his current hospital in Wisconsin, where he runs the intensive care unit two weeks a month, managers called him to a meeting in September, where he was informed he could no longer prescribe ivermectin. He’d been giving it to “every patient with COVID,” he said.

“After the pharma-geddon that was unleashed, yeah, they shut it down,” he told the South Carolina lawmakers. “And I will tell you that many hospitals across the country had already shut it down months ago.”

Framing the ivermectin fight as a battle against faceless federal agencies and big pharmaceutical corporations appealed to Americans already suspicious of the science behind the pandemic and the approved COVID vaccines.

Dr. Kory suggests success stories with COVID treatments in other parts of the world have been suppressed to instead promote the vaccines.

In an interview with NPR, Dr. Kory said he regrets the flashpoint he helped ignite.

“I feel really bad for the patients, and I feel really bad for the doctors,” he told NPR. “Both of them — both the patients and doctors — are trapped.”

Patients are still demanding the treatment, but doctors sympathetic to their wishes are being told by their health systems not to try it.

Now conservatives in elected office are sensing political payoff if they step in to help patients get the drug. State legislatures, including those in Tennessee and Alaska, are debating various ways to increase access to ivermectin — with proposals such as shielding doctors from repercussions for prescribing it, or forcing pharmacists to fill questionable prescriptions.

The Montana State News Bureau reported that the state’s Republican attorney general dispatched a state trooper to a hospital in Helena where a politically connected patient was dying of COVID. Her family was asking for ivermectin.

In a statement, St. Peter’s Hospital said doctors and nurses were “harassed and threatened by three public officials.”

“These officials have no medical training or experience, yet they were insisting our providers give treatments for COVID-19 that are not authorized, clinically approved, or within the guidelines established by the FDA and the CDC,” the statement added.

On Oct. 14, the Republican attorney general in Nebraska addressed the controversy, issuing a nearly 50-page legal opinion arguing that doctors who consider the “off-label” use of ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine for COVID are acting within the parameters of their state medical licenses, as long as the physician obtains appropriate informed consent from a patient.

Some patients have filed lawsuits to obtain ivermectin, with mixed success. A patient in Illinois was denied. But other hospitals, including one in Ohio, have been forced to administer the drug against the objections of their physicians.

Even as they gain powerful political supporters, some ivermectin fans say they’re now avoiding the health care system — because they’ve lost faith in it.

Lesa Berry, of Richmond, Va., had a friend who died earlier this year of COVID. The doctors refused to use ivermectin, despite requests from Ms. Berry and the patient’s daughter.

They know better now, she said.

“My first attempt would have been to keep her out of the hospital,” Ms. Berry said. “Because right now when you go to the hospital, they only give you what’s on the CDC protocol.”

Ms. Berry and her husband have purchased their own supply of ivermectin, which they keep at home.

This story is from a partnership that includes NPR, Nashville Public Radio and KHN. KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Breast milk of COVID-19–infected mothers helps build infant’s immune defenses

It’s rare for mothers with COVID-19 to transfer the infection to their newborns, according to a new small study.

The research, published in JAMA Network Open, found that newborns of mothers infected with the COVID-19 virus were able to develop their own immune defenses via their mother’s breast milk. Researchers detected antibodies in the infants’ saliva.

“It is the first time that this mechanism has been demonstrated,” said study author Rita Carsetti, MD, head of immunology diagnostics for Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome. “We now know how breast milk can help babies develop their immune defenses. The system could work the same way for many other pathogens, which are present in the mother during breastfeeding.”

Dr. Carsetti and colleagues examined data from 28 pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 and who gave birth at Policlinico Umberto I in Rome between November 2020 and May 2021, and their newborns. They investigated the immune responses of the mothers and their newborns by detecting spike-specific antibodies in serum, and the mucosal immune response was assessed by measuring specific antibodies in maternal breast milk and infant saliva 48 hours after delivery and 2 months later.

Twenty-one mothers and their newborns completed the 2 months of follow-up. Researchers found that the majority of the mothers had mild symptoms of COVID-19, while only three of them were admitted for worsening condition. There was only one reported case of a possible vertical transmission – transmitted in utero – and one case of a horizontal infection through droplets or respiratory secretions, which occurred when the newborn was taken home.

The results of the study showed that antibodies specific to the virus were present in the mothers’ blood at 2 months after delivery, but not at 48 hours. However, in milk, specific antibodies were already present 48 hours after delivery.

Therefore, after 48 hours, the breastfed babies had specific mucosal antibodies against COVID-19 in their saliva that the other newborns did not have. Two months later, these antibodies continued to be present even though the mothers had stopped producing them.

The findings suggest that breast milk offers protection by transferring the antibodies produced by the mother to the baby, but also by helping them to produce their own immune defenses.

“I am not surprised that infants of mothers who had COVID-19 infection in the peripartum period pass anti-spike protein IgA to their infants,” J. Howard Smart, MD, FAAP, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview. “This confirmation is good news for breastfeeding mothers.

“I wonder whether we really know these infants did not become infected, and produce their own antibodies,” said Dr. Smart, chairman of the department of pediatrics at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said having COVID-19 should not stop mothers from giving their children breast milk. The organization also said that the chance of COVID-19 passing through the breast milk and causing infection in the newborn infant is slim.

“Breast milk also helps protect babies from infections, including infections of the ears, lungs, and digestive system. For these reasons, having COVID-19 should not stop you from giving your baby breast milk,” according to ACOG’s website.

Similar studies on mothers who received the COVID-19 vaccination rather than being infected would be interesting, Dr. Smart added.

The authors of the current study plan to broaden their research by evaluating the response of pregnant mothers vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 for the presence of antibodies in the milk and the immunity of their newborns. Dr. Carsetti said her team plans to expand the study to other infections, such as cytomegalovirus and respiratory syncytial virus.

None of the researchers or commentators had financial disclosures.

It’s rare for mothers with COVID-19 to transfer the infection to their newborns, according to a new small study.

The research, published in JAMA Network Open, found that newborns of mothers infected with the COVID-19 virus were able to develop their own immune defenses via their mother’s breast milk. Researchers detected antibodies in the infants’ saliva.

“It is the first time that this mechanism has been demonstrated,” said study author Rita Carsetti, MD, head of immunology diagnostics for Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome. “We now know how breast milk can help babies develop their immune defenses. The system could work the same way for many other pathogens, which are present in the mother during breastfeeding.”

Dr. Carsetti and colleagues examined data from 28 pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 and who gave birth at Policlinico Umberto I in Rome between November 2020 and May 2021, and their newborns. They investigated the immune responses of the mothers and their newborns by detecting spike-specific antibodies in serum, and the mucosal immune response was assessed by measuring specific antibodies in maternal breast milk and infant saliva 48 hours after delivery and 2 months later.

Twenty-one mothers and their newborns completed the 2 months of follow-up. Researchers found that the majority of the mothers had mild symptoms of COVID-19, while only three of them were admitted for worsening condition. There was only one reported case of a possible vertical transmission – transmitted in utero – and one case of a horizontal infection through droplets or respiratory secretions, which occurred when the newborn was taken home.

The results of the study showed that antibodies specific to the virus were present in the mothers’ blood at 2 months after delivery, but not at 48 hours. However, in milk, specific antibodies were already present 48 hours after delivery.

Therefore, after 48 hours, the breastfed babies had specific mucosal antibodies against COVID-19 in their saliva that the other newborns did not have. Two months later, these antibodies continued to be present even though the mothers had stopped producing them.

The findings suggest that breast milk offers protection by transferring the antibodies produced by the mother to the baby, but also by helping them to produce their own immune defenses.

“I am not surprised that infants of mothers who had COVID-19 infection in the peripartum period pass anti-spike protein IgA to their infants,” J. Howard Smart, MD, FAAP, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview. “This confirmation is good news for breastfeeding mothers.

“I wonder whether we really know these infants did not become infected, and produce their own antibodies,” said Dr. Smart, chairman of the department of pediatrics at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said having COVID-19 should not stop mothers from giving their children breast milk. The organization also said that the chance of COVID-19 passing through the breast milk and causing infection in the newborn infant is slim.

“Breast milk also helps protect babies from infections, including infections of the ears, lungs, and digestive system. For these reasons, having COVID-19 should not stop you from giving your baby breast milk,” according to ACOG’s website.

Similar studies on mothers who received the COVID-19 vaccination rather than being infected would be interesting, Dr. Smart added.

The authors of the current study plan to broaden their research by evaluating the response of pregnant mothers vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 for the presence of antibodies in the milk and the immunity of their newborns. Dr. Carsetti said her team plans to expand the study to other infections, such as cytomegalovirus and respiratory syncytial virus.

None of the researchers or commentators had financial disclosures.

It’s rare for mothers with COVID-19 to transfer the infection to their newborns, according to a new small study.

The research, published in JAMA Network Open, found that newborns of mothers infected with the COVID-19 virus were able to develop their own immune defenses via their mother’s breast milk. Researchers detected antibodies in the infants’ saliva.

“It is the first time that this mechanism has been demonstrated,” said study author Rita Carsetti, MD, head of immunology diagnostics for Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome. “We now know how breast milk can help babies develop their immune defenses. The system could work the same way for many other pathogens, which are present in the mother during breastfeeding.”

Dr. Carsetti and colleagues examined data from 28 pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 and who gave birth at Policlinico Umberto I in Rome between November 2020 and May 2021, and their newborns. They investigated the immune responses of the mothers and their newborns by detecting spike-specific antibodies in serum, and the mucosal immune response was assessed by measuring specific antibodies in maternal breast milk and infant saliva 48 hours after delivery and 2 months later.

Twenty-one mothers and their newborns completed the 2 months of follow-up. Researchers found that the majority of the mothers had mild symptoms of COVID-19, while only three of them were admitted for worsening condition. There was only one reported case of a possible vertical transmission – transmitted in utero – and one case of a horizontal infection through droplets or respiratory secretions, which occurred when the newborn was taken home.

The results of the study showed that antibodies specific to the virus were present in the mothers’ blood at 2 months after delivery, but not at 48 hours. However, in milk, specific antibodies were already present 48 hours after delivery.

Therefore, after 48 hours, the breastfed babies had specific mucosal antibodies against COVID-19 in their saliva that the other newborns did not have. Two months later, these antibodies continued to be present even though the mothers had stopped producing them.

The findings suggest that breast milk offers protection by transferring the antibodies produced by the mother to the baby, but also by helping them to produce their own immune defenses.

“I am not surprised that infants of mothers who had COVID-19 infection in the peripartum period pass anti-spike protein IgA to their infants,” J. Howard Smart, MD, FAAP, who was not involved with the study, said in an interview. “This confirmation is good news for breastfeeding mothers.

“I wonder whether we really know these infants did not become infected, and produce their own antibodies,” said Dr. Smart, chairman of the department of pediatrics at Sharp Rees-Stealy Medical Group in San Diego.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said having COVID-19 should not stop mothers from giving their children breast milk. The organization also said that the chance of COVID-19 passing through the breast milk and causing infection in the newborn infant is slim.

“Breast milk also helps protect babies from infections, including infections of the ears, lungs, and digestive system. For these reasons, having COVID-19 should not stop you from giving your baby breast milk,” according to ACOG’s website.

Similar studies on mothers who received the COVID-19 vaccination rather than being infected would be interesting, Dr. Smart added.

The authors of the current study plan to broaden their research by evaluating the response of pregnant mothers vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 for the presence of antibodies in the milk and the immunity of their newborns. Dr. Carsetti said her team plans to expand the study to other infections, such as cytomegalovirus and respiratory syncytial virus.

None of the researchers or commentators had financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Expected spike in acute flaccid myelitis did not occur in 2020

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

suggested researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is an uncommon but serious complication of some viral infections, including West Nile virus and nonpolio enteroviruses. It is “characterized by sudden onset of limb weakness and lesions in the gray matter of the spinal cord,” they said, and more than 90% of cases occur in young children.

Cases of AFM, which can lead to respiratory insufficiency and permanent paralysis, spiked during the late summer and early fall in 2014, 2016, and 2018 and were expected to do so again in 2020, Sarah Kidd, MD, and associates at the division of viral diseases at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta, said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Monthly peaks in those previous years – each occurring in September – reached 51 cases in 2014, 43 cases in 2016, and 88 cases in 2018, but in 2020 there was only 1 case reported in September, with a high of 4 coming in May, CDC data show. The total number of cases for 2020 (32) was, in fact, lower than in 2019, when 47 were reported.

The investigators’ main objective was to see if there were any differences between the 2018 and 2019-2020 cases. Reports from state health departments to the CDC showed that, in 2019-2020, “patients were older; more likely to have lower limb involvement; and less likely to have upper limb involvement, prodromal illness, [cerebrospinal fluid] pleocytosis, or specimens that tested positive for EV [enterovirus]-D68” than patients from 2018, Dr. Kidd and associates said.

Mask wearing and reduced in-school attendance may have decreased circulation of EV-D68 – the enterovirus type most often detected in the stool and respiratory specimens of AFM patients – as was seen with other respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus, in 2020. Previous studies have suggested that EV-D68 drives the increases in cases during peak years, the researchers noted.

The absence of such an increase “in 2020 reflects a deviation from the previously observed biennial pattern, and it is unclear when the next increase in AFM should be expected. Clinicians should continue to maintain vigilance and suspect AFM in any child with acute flaccid limb weakness, particularly in the setting of recent febrile or respiratory illness,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

COVID vaccines’ protection dropped sharply over 6 months: Study

, a study of almost 800,000 veterans found.

The study, published in the journal Science ., says the three vaccines offered about the same protection against the virus in March, when the Delta variant was first detected in the United States, but that changed 6 months later.

The Moderna two-dose vaccine went from being 89% effective in March to 58% effective in September, according to a story about the study in theLos Angeles Times.

Meanwhile, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine went from being 87% effective to 45% effective over the same time period.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine showed the biggest drop -- from 86% effectiveness to 13% over those 6 months.

“In summary, although vaccination remains protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection, protection waned as the Delta variant emerged in the U.S., and this decline did not differ by age,” the study said.

The three vaccines also lost effectiveness in the ability to protect against death in veterans 65 and over after only 3 months, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group, veterans who got the Moderna vaccine and had a breakthrough case were 76% less likely to die of COVID-19 by July.

The protection was 70% for Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine recipients and 52% for J&J vaccine recipients for the same age group, compared to unvaccinated veterans, according to the newspaper.

For veterans under 65, the protectiveness against a fatal case of COVID was 84% for Pfizer/BioNTech recipients, 82% for Moderna recipients, and 73% for J&J recipients, compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group.

The study confirms the need for booster vaccines and protective measures such as vaccine passports, vaccine mandates, masking, hand-washing, and social distancing, the researchers said.

Of the veterans studied, about 500,000 were vaccinated and 300,000 were not. Researchers noted that the study population had 6 times as many men as women. About 48% of the study group was 65 or older, 29% was 50-64, while 24% was under 50.

Researchers from the Public Health Institute in Oakland, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Francisco, and the University of Texas Health Science Center conducted the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a study of almost 800,000 veterans found.

The study, published in the journal Science ., says the three vaccines offered about the same protection against the virus in March, when the Delta variant was first detected in the United States, but that changed 6 months later.

The Moderna two-dose vaccine went from being 89% effective in March to 58% effective in September, according to a story about the study in theLos Angeles Times.

Meanwhile, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine went from being 87% effective to 45% effective over the same time period.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine showed the biggest drop -- from 86% effectiveness to 13% over those 6 months.

“In summary, although vaccination remains protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection, protection waned as the Delta variant emerged in the U.S., and this decline did not differ by age,” the study said.

The three vaccines also lost effectiveness in the ability to protect against death in veterans 65 and over after only 3 months, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group, veterans who got the Moderna vaccine and had a breakthrough case were 76% less likely to die of COVID-19 by July.

The protection was 70% for Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine recipients and 52% for J&J vaccine recipients for the same age group, compared to unvaccinated veterans, according to the newspaper.

For veterans under 65, the protectiveness against a fatal case of COVID was 84% for Pfizer/BioNTech recipients, 82% for Moderna recipients, and 73% for J&J recipients, compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group.

The study confirms the need for booster vaccines and protective measures such as vaccine passports, vaccine mandates, masking, hand-washing, and social distancing, the researchers said.

Of the veterans studied, about 500,000 were vaccinated and 300,000 were not. Researchers noted that the study population had 6 times as many men as women. About 48% of the study group was 65 or older, 29% was 50-64, while 24% was under 50.

Researchers from the Public Health Institute in Oakland, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Francisco, and the University of Texas Health Science Center conducted the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

, a study of almost 800,000 veterans found.

The study, published in the journal Science ., says the three vaccines offered about the same protection against the virus in March, when the Delta variant was first detected in the United States, but that changed 6 months later.

The Moderna two-dose vaccine went from being 89% effective in March to 58% effective in September, according to a story about the study in theLos Angeles Times.

Meanwhile, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine went from being 87% effective to 45% effective over the same time period.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine showed the biggest drop -- from 86% effectiveness to 13% over those 6 months.

“In summary, although vaccination remains protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection, protection waned as the Delta variant emerged in the U.S., and this decline did not differ by age,” the study said.

The three vaccines also lost effectiveness in the ability to protect against death in veterans 65 and over after only 3 months, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group, veterans who got the Moderna vaccine and had a breakthrough case were 76% less likely to die of COVID-19 by July.

The protection was 70% for Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine recipients and 52% for J&J vaccine recipients for the same age group, compared to unvaccinated veterans, according to the newspaper.

For veterans under 65, the protectiveness against a fatal case of COVID was 84% for Pfizer/BioNTech recipients, 82% for Moderna recipients, and 73% for J&J recipients, compared to unvaccinated veterans in that age group.

The study confirms the need for booster vaccines and protective measures such as vaccine passports, vaccine mandates, masking, hand-washing, and social distancing, the researchers said.

Of the veterans studied, about 500,000 were vaccinated and 300,000 were not. Researchers noted that the study population had 6 times as many men as women. About 48% of the study group was 65 or older, 29% was 50-64, while 24% was under 50.

Researchers from the Public Health Institute in Oakland, the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Francisco, and the University of Texas Health Science Center conducted the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

Severe COVID two times higher for cancer patients

A new systematic review and meta-analysis finds that unvaccinated cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 last year, were more than two times more likely – than people without cancer – to develop a case of COVID-19 so severe it required hospitalization in an intensive care unit.

“Our study provides the most precise measure to date of the effect of COVID-19 in cancer patients,” wrote researchers who were led by Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, a specialist in population science with the Stony Brook Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Boffetta and colleagues also found that patients with hematologic neoplasms had a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 comparable to that of all cancers combined.

Cancer patients have long been considered to be among those patients who are at high risk of developing COVID-19, and if they contract the disease, they are at high risk of having poor outcomes. Other high-risk patients include those with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or COPD, or the elderly. But how high the risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease is for cancer patients hasn’t yet been documented on a wide scale.

The study, which was made available as a preprint on medRxiv on Oct. 23, is based on an analysis of COVID-19 cases that were documented in 35 reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and studies indexed in PubMed from authors in North America, Europe, and Asia.

In this study, the pooled odds ratio for mortality for all patients with any cancer was 2.32 (95% confidence interval, 1.82-2.94; 24 studies). For ICU admission, the odds ratio was 2.39 (95% CI, 1.90-3.02; I2 0.0%; 5 studies). And, for disease severity or hospitalization, it was 2.08 (95% CI, 1.60-2.72; I2 92.1%; 15 studies). The pooled mortality odds ratio for hematologic neoplasms was 2.14 (95% CI, 1.87-2.44; I2 20.8%; 8 studies).

Their findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, confirmed the results of a similar analysis from China published as a preprint in May 2020. The analysis included 181,323 patients (23,736 cancer patients) from 26 studies reported an odds ratio of 2.54 (95% CI, 1.47-4.42). “Cancer patients with COVID-19 have an increased likelihood of death compared to non-cancer COVID-19 patients,” Venkatesulu et al. wrote. And a systematic review and meta-analysis of five studies of 2,619 patients published in October 2020 in Medicine also found a significantly higher risk of death from COVID-19 among cancer patients (odds ratio, 2.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-6.06; P = .023; I2 = 26.4%).

Fakih et al., writing in the journal Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy conducted a meta-analysis early last year finding a threefold increase for admission to the intensive care unit, an almost fourfold increase for a severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a fivefold increase for being intubated.

The three studies show that mortality rates were higher early in the pandemic “when diagnosis and treatment for SARS-CoV-2 might have been delayed, resulting in higher death rate,” Boffetta et al. wrote, adding that their analysis showed only a twofold increase most likely because it was a year-long analysis.

“Future studies will be able to better analyze this association for the different subtypes of cancer. Furthermore, they will eventually be able to evaluate whether the difference among vaccinated population is reduced,” Boffetta et al. wrote.

The authors noted several limitations for the study, including the fact that many of the studies included in the analysis did not include sex, age, comorbidities, and therapy. Nor were the authors able to analyze specific cancers other than hematologic neoplasms.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A new systematic review and meta-analysis finds that unvaccinated cancer patients who contracted COVID-19 last year, were more than two times more likely – than people without cancer – to develop a case of COVID-19 so severe it required hospitalization in an intensive care unit.

“Our study provides the most precise measure to date of the effect of COVID-19 in cancer patients,” wrote researchers who were led by Paolo Boffetta, MD, MPH, a specialist in population science with the Stony Brook Cancer Center in New York.

Dr. Boffetta and colleagues also found that patients with hematologic neoplasms had a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 comparable to that of all cancers combined.

Cancer patients have long been considered to be among those patients who are at high risk of developing COVID-19, and if they contract the disease, they are at high risk of having poor outcomes. Other high-risk patients include those with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, or COPD, or the elderly. But how high the risk of developing severe COVID-19 disease is for cancer patients hasn’t yet been documented on a wide scale.

The study, which was made available as a preprint on medRxiv on Oct. 23, is based on an analysis of COVID-19 cases that were documented in 35 reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, and studies indexed in PubMed from authors in North America, Europe, and Asia.