User login

Long COVID associated with risk of metabolic liver disease

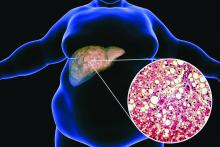

Postacute COVID syndrome (PACS), an ongoing inflammatory state following infection with SARS-CoV-2, is associated with greater risk of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), according to an analysis of patients at a single clinic in Canada published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

MAFLD, also known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is considered an indicator of general health and is in turn linked to greater risk of cardiovascular complications and mortality. It may be a multisystem disorder with various underlying causes.

PACS includes symptoms that affect various organ systems, with neurocognitive, autonomic, gastrointestinal, respiratory, musculoskeletal, psychological, sensory, and dermatologic clusters. An estimated 50%-80% of COVID-19 patients experience one or more clusters of symptoms 3 months after leaving the hospital.

But liver problems also appear in the acute phase, said Paul Martin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study. “Up to about half the patients during the acute illness may have elevated liver tests, but there seems to be a subset of patients in whom the abnormality persists. And then there are some reports in the literature of patients developing injury to their bile ducts in the liver over the long term, apparently as a consequence of COVID infection. What this paper suggests is that there may be some metabolic derangements associated with COVID infection, which in turn can accentuate or possibly cause fatty liver,” said Dr. Martin in an interview. He is chief of digestive health and liver diseases and a professor of medicine at the University of Miami.

“It highlights the need to get vaccinated against COVID and to take appropriate precautions because contracting the infection may lead to all sorts of consequences quite apart from having a respiratory illness,” said Dr. Martin.

The researchers retrospectively identified 235 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between July 2020 and April 2021. Overall, 69% were men, and the median age was 61 years; 19.2% underwent mechanical ventilation and the mean duration of hospitalization was 11.7 days. They were seen for PACS symptoms a median 143 days after COVID-19 symptoms began, with 77.5% having symptoms of at least one PACS cluster. Of these clusters, 34.9% were neurocognitive, 53.2% were respiratory, 26.4% were musculoskeletal, 29.4% were psychological, 25.1% were dermatologic, and 17.5% were sensory.

At the later clinical visit for PACS symptoms, all patients underwent screening for MAFLD, which was defined as the presence of liver steatosis plus overweight/obesity or type 2 diabetes. Hepatic steatosis was determined from controlled attenuation parameter using transient elastrography. The analysis excluded patients with significant alcohol intake or hepatitis B or C. All patients with liver steatosis also had MAFLD, and this included 55.3% of the study population.

The hospital was able to obtain hepatic steatosis index (HSI) scores for 103 of 235 patients. Of these, 50% had MAFLD on admission for acute COVID-19, and 48.1% had MAFLD upon discharge based on this criterion. At the PACS follow-up visit, 71.3% were diagnosed with MAFLD. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of glucocorticoids or tocilizumab during hospitalization between those with and without MAFLD, and remdesivir use was insignificant in the patient population.

Given that the prevalence of MAFLD among the study population is more than double that in the general population, the authors suggest that MAFLD may be a new PACS cluster phenotype that could lead to long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complications. A potential explanation is loss of lean body mass during COVID-19 hospitalization followed by liver fat accumulation during recovery.

Other infections have also shown an association with increased MAFLD incidence, including HIV, Heliobacter pylori, and viral hepatitis. The authors worry that COVID-19 infection could exacerbate underlying conditions to a more severe MAFLD disease state.

The study is limited by a small sample size, limited follow-up, and the lack of a control group. Its retrospective nature leaves it vulnerable to biases.

“The natural history of MAFLD in the context of PACS is unknown at this time, and careful follow-up of these patients is needed to understand the clinical implications of this syndrome in the context of long COVID,” the authors wrote. “We speculate that [MAFLD] may be considered as an independent PACS-cluster phenotype, potentially affecting the metabolic and cardiovascular health of patients with PACS.”

One author has relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but the remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Martin has no relevant financial disclosures.

Postacute COVID syndrome (PACS), an ongoing inflammatory state following infection with SARS-CoV-2, is associated with greater risk of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), according to an analysis of patients at a single clinic in Canada published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

MAFLD, also known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is considered an indicator of general health and is in turn linked to greater risk of cardiovascular complications and mortality. It may be a multisystem disorder with various underlying causes.

PACS includes symptoms that affect various organ systems, with neurocognitive, autonomic, gastrointestinal, respiratory, musculoskeletal, psychological, sensory, and dermatologic clusters. An estimated 50%-80% of COVID-19 patients experience one or more clusters of symptoms 3 months after leaving the hospital.

But liver problems also appear in the acute phase, said Paul Martin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study. “Up to about half the patients during the acute illness may have elevated liver tests, but there seems to be a subset of patients in whom the abnormality persists. And then there are some reports in the literature of patients developing injury to their bile ducts in the liver over the long term, apparently as a consequence of COVID infection. What this paper suggests is that there may be some metabolic derangements associated with COVID infection, which in turn can accentuate or possibly cause fatty liver,” said Dr. Martin in an interview. He is chief of digestive health and liver diseases and a professor of medicine at the University of Miami.

“It highlights the need to get vaccinated against COVID and to take appropriate precautions because contracting the infection may lead to all sorts of consequences quite apart from having a respiratory illness,” said Dr. Martin.

The researchers retrospectively identified 235 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between July 2020 and April 2021. Overall, 69% were men, and the median age was 61 years; 19.2% underwent mechanical ventilation and the mean duration of hospitalization was 11.7 days. They were seen for PACS symptoms a median 143 days after COVID-19 symptoms began, with 77.5% having symptoms of at least one PACS cluster. Of these clusters, 34.9% were neurocognitive, 53.2% were respiratory, 26.4% were musculoskeletal, 29.4% were psychological, 25.1% were dermatologic, and 17.5% were sensory.

At the later clinical visit for PACS symptoms, all patients underwent screening for MAFLD, which was defined as the presence of liver steatosis plus overweight/obesity or type 2 diabetes. Hepatic steatosis was determined from controlled attenuation parameter using transient elastrography. The analysis excluded patients with significant alcohol intake or hepatitis B or C. All patients with liver steatosis also had MAFLD, and this included 55.3% of the study population.

The hospital was able to obtain hepatic steatosis index (HSI) scores for 103 of 235 patients. Of these, 50% had MAFLD on admission for acute COVID-19, and 48.1% had MAFLD upon discharge based on this criterion. At the PACS follow-up visit, 71.3% were diagnosed with MAFLD. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of glucocorticoids or tocilizumab during hospitalization between those with and without MAFLD, and remdesivir use was insignificant in the patient population.

Given that the prevalence of MAFLD among the study population is more than double that in the general population, the authors suggest that MAFLD may be a new PACS cluster phenotype that could lead to long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complications. A potential explanation is loss of lean body mass during COVID-19 hospitalization followed by liver fat accumulation during recovery.

Other infections have also shown an association with increased MAFLD incidence, including HIV, Heliobacter pylori, and viral hepatitis. The authors worry that COVID-19 infection could exacerbate underlying conditions to a more severe MAFLD disease state.

The study is limited by a small sample size, limited follow-up, and the lack of a control group. Its retrospective nature leaves it vulnerable to biases.

“The natural history of MAFLD in the context of PACS is unknown at this time, and careful follow-up of these patients is needed to understand the clinical implications of this syndrome in the context of long COVID,” the authors wrote. “We speculate that [MAFLD] may be considered as an independent PACS-cluster phenotype, potentially affecting the metabolic and cardiovascular health of patients with PACS.”

One author has relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but the remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Martin has no relevant financial disclosures.

Postacute COVID syndrome (PACS), an ongoing inflammatory state following infection with SARS-CoV-2, is associated with greater risk of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), according to an analysis of patients at a single clinic in Canada published in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

MAFLD, also known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), is considered an indicator of general health and is in turn linked to greater risk of cardiovascular complications and mortality. It may be a multisystem disorder with various underlying causes.

PACS includes symptoms that affect various organ systems, with neurocognitive, autonomic, gastrointestinal, respiratory, musculoskeletal, psychological, sensory, and dermatologic clusters. An estimated 50%-80% of COVID-19 patients experience one or more clusters of symptoms 3 months after leaving the hospital.

But liver problems also appear in the acute phase, said Paul Martin, MD, who was asked to comment on the study. “Up to about half the patients during the acute illness may have elevated liver tests, but there seems to be a subset of patients in whom the abnormality persists. And then there are some reports in the literature of patients developing injury to their bile ducts in the liver over the long term, apparently as a consequence of COVID infection. What this paper suggests is that there may be some metabolic derangements associated with COVID infection, which in turn can accentuate or possibly cause fatty liver,” said Dr. Martin in an interview. He is chief of digestive health and liver diseases and a professor of medicine at the University of Miami.

“It highlights the need to get vaccinated against COVID and to take appropriate precautions because contracting the infection may lead to all sorts of consequences quite apart from having a respiratory illness,” said Dr. Martin.

The researchers retrospectively identified 235 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between July 2020 and April 2021. Overall, 69% were men, and the median age was 61 years; 19.2% underwent mechanical ventilation and the mean duration of hospitalization was 11.7 days. They were seen for PACS symptoms a median 143 days after COVID-19 symptoms began, with 77.5% having symptoms of at least one PACS cluster. Of these clusters, 34.9% were neurocognitive, 53.2% were respiratory, 26.4% were musculoskeletal, 29.4% were psychological, 25.1% were dermatologic, and 17.5% were sensory.

At the later clinical visit for PACS symptoms, all patients underwent screening for MAFLD, which was defined as the presence of liver steatosis plus overweight/obesity or type 2 diabetes. Hepatic steatosis was determined from controlled attenuation parameter using transient elastrography. The analysis excluded patients with significant alcohol intake or hepatitis B or C. All patients with liver steatosis also had MAFLD, and this included 55.3% of the study population.

The hospital was able to obtain hepatic steatosis index (HSI) scores for 103 of 235 patients. Of these, 50% had MAFLD on admission for acute COVID-19, and 48.1% had MAFLD upon discharge based on this criterion. At the PACS follow-up visit, 71.3% were diagnosed with MAFLD. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of glucocorticoids or tocilizumab during hospitalization between those with and without MAFLD, and remdesivir use was insignificant in the patient population.

Given that the prevalence of MAFLD among the study population is more than double that in the general population, the authors suggest that MAFLD may be a new PACS cluster phenotype that could lead to long-term metabolic and cardiovascular complications. A potential explanation is loss of lean body mass during COVID-19 hospitalization followed by liver fat accumulation during recovery.

Other infections have also shown an association with increased MAFLD incidence, including HIV, Heliobacter pylori, and viral hepatitis. The authors worry that COVID-19 infection could exacerbate underlying conditions to a more severe MAFLD disease state.

The study is limited by a small sample size, limited follow-up, and the lack of a control group. Its retrospective nature leaves it vulnerable to biases.

“The natural history of MAFLD in the context of PACS is unknown at this time, and careful follow-up of these patients is needed to understand the clinical implications of this syndrome in the context of long COVID,” the authors wrote. “We speculate that [MAFLD] may be considered as an independent PACS-cluster phenotype, potentially affecting the metabolic and cardiovascular health of patients with PACS.”

One author has relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, but the remaining authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Martin has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM OPEN FORUM INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Five things you should know about ‘free’ at-home COVID tests

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Americans keep hearing that it is important to test frequently for COVID-19 at home. But just try to find an “at-home” rapid COVID test in a store and at a price that makes frequent tests affordable.

Testing, as well as mask-wearing, is an important measure if the country ever hopes to beat COVID, restore normal routines and get the economy running efficiently. To get Americans cheaper tests, the federal government now plans to have insurance companies pay for them.

You can either get one without any out-of-pocket expense from retail pharmacies that are part of an insurance company’s network or buy it at any store and get reimbursed by the insurer.

Congress said private insurers must cover all COVID testing and any associated medical services when it passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES, Act. The have-insurance-pay-for-it solution has been used frequently through the pandemic. Insurance companies have been told to pay for polymerase chain reaction tests, COVID treatments and the administration of vaccines. (Taxpayers are paying for the cost of the vaccines themselves.) It appears to be an elegant solution for a politician because it looks free and isn’t using taxpayer money.

1. Are the tests really free?

Well, no. As many an economist will tell you, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. Someone has to pick up the tab. Initially, the insurance companies bear the cost. Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF who studies the Affordable Care Act and private insurers, said the total bill could amount to billions of dollars. Exactly how much depends on “how easy it is to get them, and how many will be reimbursed,” she said.

2. Will the insurance company just swallow those imposed costs?

If companies draw from the time-tested insurance giants’ playbook, they’ll pass along those costs to customers. “This will put upward pressure on premiums,” said Emily Gee, vice president and coordinator for health policy at the Center for American Progress.

Major insurance companies like Cigna, Anthem, UnitedHealthcare, and Aetna did not respond to requests to discuss this issue.

3. If that’s the case, why haven’t I been hit with higher premiums already?

Insurance companies had the chance last year to raise premiums but, mostly, they did not.

Why? Perhaps because insurers have so far made so much money during the pandemic they didn’t need to. For example, the industry’s profits in 2020 increased 41% to $31 billion from $22 billion, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. The NAIC said the industry has continued its “tremendous growth trend” that started before COVID emerged. Companies will be reporting 2021 results soon.

The reason behind these profits is clear. You were paying premiums based on projections your insurance company made about how much health care consumers would use that year. Because people stayed home, had fewer accidents, postponed surgeries and often avoided going to visit the doctor or the hospital, insurers paid out less. They rebated some of their earnings back to customers, but they pocketed a lot more.

As the companies’ actuaries work on predicting 2023 expenditures, premiums could go up if they foresee more claims and expenses. Paying for millions of rapid tests is something they would include in their calculations.

4. Regardless of my premiums, will the tests cost me money directly?

It’s quite possible. If your insurance company doesn’t have an arrangement with a retailer where you can simply pick up your allotted tests, you’ll have to pay for them – at whatever price the store sets. If that’s the case, you’ll need to fill out a form to request a reimbursement from the insurance company. How many times have you lost receipts or just plain neglected to mail in for rebates on something you bought? A lot, right?

Here’s another thing: The reimbursement is set at $12 per test. If you pay $30 for a test – and that is not unheard of – your insurer is only on the hook for $12. You eat the $18.

And by the way, people on Medicare will have to pay for their tests themselves. People who get their health care covered by Medicaid can obtain free test kits at community centers.

A few free tests are supposed to arrive at every American home via the U.S. Postal Service. And the Biden administration has activated a website where Americans can order free tests from a cache of a billion the federal government ordered.

5. Will this help bring down the costs of at-home tests and make them easier to find?

The free COVID tests are unlikely to have much immediate impact on general cost and availability. You will still need to search for them. The federal measures likely will stimulate the demand for tests, which in the short term may make them harder to find.

But the demand, and some government guarantees to manufacturers, may induce test makers to make more of them faster. The increased competition and supply theoretically could bring down the price. There is certainly room for prices to decline since the wholesale cost of the test is between $5 and $7, analysts estimate. “It’s a big step in the right direction,” Ms. Gee said.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Two studies detail the dangers of COVID in pregnancy

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two new studies show how COVID-19 threatens the health of pregnant people and their newborn infants.

A study conducted in Scotland showed that unvaccinated pregnant people who got COVID were much more likely to have a stillborn infant or one that dies in the first 28 days. The study also found that pregnant women infected with COVID died or needed hospitalization at a much higher rate than vaccinated women who got pregnant.

The University of Edinburgh and Public Health Scotland studied national data in 88,000 pregnancies between Dec. 2020 and Oct. 2021, according to the study published in Nature Medicine.

Overall, 77.4% of infections, 90.9% of COVID-related hospitalizations, and 98% of critical care cases occurred in the unvaccinated people, as did all newborn deaths.

The study said 2,364 babies were born to women infected with COVID, with 2,353 live births. Eleven babies were stillborn and eight live-born babies died within 28 days. Of the live births, 241 were premature.

The problems were more likely if the infection occurred 28 days or less before the delivery date, the researchers said.

The authors said the low vaccination rate among pregnant people was a problem. Only 32% of people giving birth in Oct. 2021 were fully vaccinated, while 77% of the Scottish female population aged 18-44 was fully vaccinated.

“Vaccine hesitancy in pregnancy thus requires addressing, especially in light of new recommendations for booster vaccination administration 3 months after the initial vaccination course to help protect against new variants such as Omicron,” the authors wrote. “Addressing low vaccine uptake rates in pregnant women is imperative to protect the health of women and babies in the ongoing pandemic.”

Vaccinated women who were pregnant had complication rates that were about the same for all pregnant women, the study shows.

The second study, published in The Lancet, found that women who got COVID while pregnant in five Western U.S. states were more likely to have premature births, low birth weights, and stillbirths, even when the COVID cases are mild.

The Institute for Systems Biology researchers in Seattle studied data for women who gave birth in Alaska, California, Montana, Oregon, or Washington from March 5, 2020, to July 4, 2021. About 18,000 of them were tested for COVID, with 882 testing positive. Of the positive tests, 85 came in the first trimester, 226 in the second trimester, and 571 in the third semester. None of the pregnant women had been vaccinated at the time they were infected.

Most of the birth problems occurred with first and second trimester infections, the study noted, and problems occurred even if the pregnant person didn’t have respiratory complications, a major COVID symptom.

“Pregnant people are at an increased risk of adverse outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection, even when maternal COVID-19 is less severe, and they may benefit from increased monitoring following infection,” Jennifer Hadlock, MD, an author of the paper, said in a news release.

The study also pointed out continuing inequities in health care, with most of the positive cases occurring among young, non-White people with Medicaid and high body mass index.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID at 2 years: Preparing for a different ‘normal’

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is still breaking records in hospital overcrowding and new cases.

The United States is logging nearly 800,000 cases a day, hospitals are starting to fray, and deaths have topped 850,000. Schools oscillate from remote to in-person learning, polarizing communities.

The vaccines are lifesaving for many, yet frustration mounts as the numbers of unvaccinated people in this country stays relatively stagnant (63% in the United States are fully vaccinated) and other parts of the world have seen hardly a single dose. Africa has the slowest vaccination rate among continents, with only 14% of the population receiving one shot, according to the New York Times tracker.

Yet

Effective vaccines and treatments that can keep people out of the hospital were developed at an astounding pace, and advances in tracking and testing – in both access and effectiveness – are starting to pay off.

Some experts say it’s possible that the raging Omicron surge will slow by late spring, providing some relief and maybe shifting the pandemic to a slower-burning endemic.

But other experts caution to keep our guard up, saying it’s time to settle into a “new normal” and upend the strategy for fighting COVID-19.

Time to change COVID thinking

Three former members of the Biden-Harris Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board wrote recently in JAMA that COVID-19 has now become one of the many viral respiratory diseases that health care providers and patients will manage each year.

The group of experts from the University of Pennsylvania, University of Minnesota, and New York University write that “many of the measures to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (for example, ventilation) will also reduce transmission of other respiratory viruses. Thus, policy makers should retire previous public health categorizations, including deaths from pneumonia and influenza or pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19, and focus on a new category: the aggregate risk of all respiratory virus infections.”

Other experts, including Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, have said it’s been clear since the early days of SARS-CoV-2 that we must learn to live with the virus because it “will be ever present for the remaining history of our species.”

But that doesn’t mean the virus will always have the upper hand. Although the United States has been reaching record numbers of hospitalizations in January, these hospitalizations differ from those of last year – marked by fewer extreme lifesaving measures, fewer deaths, and shorter hospital stays – caused in part by medical and therapeutic advances and in part to the nature of the Omicron variant itself.

One sign of progress, Dr. Adalja said, will be the widespread decoupling of cases from hospitalizations, something that has already happened in countries such as the United Kingdom.

“That’s a reflection of how well they have vaccinated their high-risk population and how poorly we have vaccinated our high-risk population,” he said.

Omicron will bump up natural immunity

Dr. Adalja said though the numbers of unvaccinated in the United States appear to be stuck, Omicron’s sweep will make the difference, leaving behind more natural immunity in the population.

Currently, hospitals are struggling with staffing concerns as a “direct result” of too many unvaccinated people, he said.

Andrew Badley, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and director of the clinic’s COVID-19 Task Force, said the good news with Omicron is that nearly all people it infects will recover.

Over time, when the body sees foreign antigens repeatedly, the quantity and quality of the antibodies the immune system produces increase and the body becomes better at fighting disease.

So “a large amount of the population will have recovered and have a degree of immunity,” Dr. Badley said.

His optimism is tempered by his belief that “it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

But Dr. Badley still predicts a turnaround. “We’ll see a downturn in COVID in late spring or early summer,” and well into the second quarter of 2022, “we’ll see a reemergence of control.”

Right now, with Omicron, one infected person is infecting three to five others, he said. The hope is that it will eventually reach one-to-one endemic levels.

As for the threat of new variants, Badley said, “it’s not predictable whether they will be stronger or weaker.”

Masks may be around for years

Many experts predict that masks will continue to be part of the national wardrobe for the foreseeable future.

“We will continue to see new cases for years and years to come. Some will respond to that with masks in public places for a very long time. I personally will do so,” Dr. Badley said.

Two mindsets: Inside/outside the hospital

Emily Landon, MD, an infectious disease doctor and the executive medical director of infection prevention and control at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization she views the pandemic from two different vantage points.

As a health care provider, she sees her hospital, like others worldwide, overwhelmed. Supplies of a major weapon to help prevent hospitalization, the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab, are running out. Dr. Landon said she has been calling other hospitals to see if they have supplies and, if so, whether Omicron patients can transfer there.

Bottom line: The things they relied on a month ago to keep people out of the hospital are no longer there, she said.

Meanwhile, “We have more COVID patients than we have ever had,” Dr. Landon said.

Last year, UChicago hit a high of 170 people hospitalized with COVID. This year, so far, the peak was 270.

Dr. Landon said she is frustrated when she leaves that overburdened world inside the hospital for the outside world, where people wear no masks or ineffective face coverings and gather unsafely. Although some of that behavior reflects an intention to flout the advice of medical experts, some is caused in part, she said, by the lack of a clear national health strategy and garbled communication from those in charge of public safety.

Americans are deciding for themselves, on an a la carte basis, whether to wear a mask or get tested or travel, and school districts decide individually when it’s time to go virtual.

“People are exhausted from having to do a risk-benefit analysis for every single activity they, their friends, their kids want to participate in,” she said.

U.S. behind in several areas

Despite our self-image as the global leader in science and medicine, the United States stumbled badly in its response to the pandemic, with grave consequences both at home and abroad, experts say.

In a recent commentary in JAMA, Lawrence Gostin, JD, from Georgetown University, Washington, and Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, pointed to several critical shortfalls in the nation’s efforts to control the disease.

One such shortfall is public trust.

This news organization reported in June 2021 that a poll of its readers found that 44% said their trust in the CDC had waned during the pandemic, and 33% said their trust in the FDA had eroded as well.

Health care providers who responded to the poll lost trust as well. About half of the doctors and nurses who responded said they disagreed with the FDA’s decision-making during the pandemic. Nearly 60% of doctors and 65% of nurses said they disagreed with the CDC’s overall pandemic guidance.

Lack of trust can make people resist vaccines and efforts to fight the virus, the authors wrote.

“This will become really relevant when we have ample supply of Pfizer’s antiviral medication,” Mr. Gostin, who directs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown, told this news organization. “The next phase of the pandemic is not to link testing to contact tracing, because we’re way past that, but to link testing to treatment.”

Lack of regional manufacturing of products is also thwarting global progress.

“It is extraordinarily important that our pharmaceutical industry transfer technology in a pandemic,” Mr. Gostin said. “The most glaring failure to do that is the mRNA vaccines. We’ve got this enormously effective vaccine and the two manufacturers – Pfizer and Moderna – are refusing to share the technology with producers in other countries. That keeps coming back to haunt us.”

Another problem: When the vaccines are shared with other countries, they are being delivered close to the date they expire or arriving at a shipyards without warning, so even some of the doses that get delivered are going to waste, Mr. Gostin said.

“It’s one of the greatest moral failures of my lifetime,” he said.

Also a failure is the “jaw-dropping” state of testing 2 years into the pandemic, he said, as people continue to pay high prices for tests or endure long lines.

The U.S. government updated its calculations and ordered 1 billion tests for the general public. The COVIDtests.gov website to order the free tests is now live.

It’s a step in the right direction. Mr. Gostin and Dr. Nuzzo wrote that there is every reason to expect future epidemics that are as serious or more serious than COVID.

“Failure to address clearly observed weaknesses in the COVID-19 response will have preventable adverse health, social, and economic consequences when the next novel outbreak occurs,” they wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is still breaking records in hospital overcrowding and new cases.

The United States is logging nearly 800,000 cases a day, hospitals are starting to fray, and deaths have topped 850,000. Schools oscillate from remote to in-person learning, polarizing communities.

The vaccines are lifesaving for many, yet frustration mounts as the numbers of unvaccinated people in this country stays relatively stagnant (63% in the United States are fully vaccinated) and other parts of the world have seen hardly a single dose. Africa has the slowest vaccination rate among continents, with only 14% of the population receiving one shot, according to the New York Times tracker.

Yet

Effective vaccines and treatments that can keep people out of the hospital were developed at an astounding pace, and advances in tracking and testing – in both access and effectiveness – are starting to pay off.

Some experts say it’s possible that the raging Omicron surge will slow by late spring, providing some relief and maybe shifting the pandemic to a slower-burning endemic.

But other experts caution to keep our guard up, saying it’s time to settle into a “new normal” and upend the strategy for fighting COVID-19.

Time to change COVID thinking

Three former members of the Biden-Harris Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board wrote recently in JAMA that COVID-19 has now become one of the many viral respiratory diseases that health care providers and patients will manage each year.

The group of experts from the University of Pennsylvania, University of Minnesota, and New York University write that “many of the measures to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (for example, ventilation) will also reduce transmission of other respiratory viruses. Thus, policy makers should retire previous public health categorizations, including deaths from pneumonia and influenza or pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19, and focus on a new category: the aggregate risk of all respiratory virus infections.”

Other experts, including Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, have said it’s been clear since the early days of SARS-CoV-2 that we must learn to live with the virus because it “will be ever present for the remaining history of our species.”

But that doesn’t mean the virus will always have the upper hand. Although the United States has been reaching record numbers of hospitalizations in January, these hospitalizations differ from those of last year – marked by fewer extreme lifesaving measures, fewer deaths, and shorter hospital stays – caused in part by medical and therapeutic advances and in part to the nature of the Omicron variant itself.

One sign of progress, Dr. Adalja said, will be the widespread decoupling of cases from hospitalizations, something that has already happened in countries such as the United Kingdom.

“That’s a reflection of how well they have vaccinated their high-risk population and how poorly we have vaccinated our high-risk population,” he said.

Omicron will bump up natural immunity

Dr. Adalja said though the numbers of unvaccinated in the United States appear to be stuck, Omicron’s sweep will make the difference, leaving behind more natural immunity in the population.

Currently, hospitals are struggling with staffing concerns as a “direct result” of too many unvaccinated people, he said.

Andrew Badley, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and director of the clinic’s COVID-19 Task Force, said the good news with Omicron is that nearly all people it infects will recover.

Over time, when the body sees foreign antigens repeatedly, the quantity and quality of the antibodies the immune system produces increase and the body becomes better at fighting disease.

So “a large amount of the population will have recovered and have a degree of immunity,” Dr. Badley said.

His optimism is tempered by his belief that “it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

But Dr. Badley still predicts a turnaround. “We’ll see a downturn in COVID in late spring or early summer,” and well into the second quarter of 2022, “we’ll see a reemergence of control.”

Right now, with Omicron, one infected person is infecting three to five others, he said. The hope is that it will eventually reach one-to-one endemic levels.

As for the threat of new variants, Badley said, “it’s not predictable whether they will be stronger or weaker.”

Masks may be around for years

Many experts predict that masks will continue to be part of the national wardrobe for the foreseeable future.

“We will continue to see new cases for years and years to come. Some will respond to that with masks in public places for a very long time. I personally will do so,” Dr. Badley said.

Two mindsets: Inside/outside the hospital

Emily Landon, MD, an infectious disease doctor and the executive medical director of infection prevention and control at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization she views the pandemic from two different vantage points.

As a health care provider, she sees her hospital, like others worldwide, overwhelmed. Supplies of a major weapon to help prevent hospitalization, the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab, are running out. Dr. Landon said she has been calling other hospitals to see if they have supplies and, if so, whether Omicron patients can transfer there.

Bottom line: The things they relied on a month ago to keep people out of the hospital are no longer there, she said.

Meanwhile, “We have more COVID patients than we have ever had,” Dr. Landon said.

Last year, UChicago hit a high of 170 people hospitalized with COVID. This year, so far, the peak was 270.

Dr. Landon said she is frustrated when she leaves that overburdened world inside the hospital for the outside world, where people wear no masks or ineffective face coverings and gather unsafely. Although some of that behavior reflects an intention to flout the advice of medical experts, some is caused in part, she said, by the lack of a clear national health strategy and garbled communication from those in charge of public safety.

Americans are deciding for themselves, on an a la carte basis, whether to wear a mask or get tested or travel, and school districts decide individually when it’s time to go virtual.

“People are exhausted from having to do a risk-benefit analysis for every single activity they, their friends, their kids want to participate in,” she said.

U.S. behind in several areas

Despite our self-image as the global leader in science and medicine, the United States stumbled badly in its response to the pandemic, with grave consequences both at home and abroad, experts say.

In a recent commentary in JAMA, Lawrence Gostin, JD, from Georgetown University, Washington, and Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, pointed to several critical shortfalls in the nation’s efforts to control the disease.

One such shortfall is public trust.

This news organization reported in June 2021 that a poll of its readers found that 44% said their trust in the CDC had waned during the pandemic, and 33% said their trust in the FDA had eroded as well.

Health care providers who responded to the poll lost trust as well. About half of the doctors and nurses who responded said they disagreed with the FDA’s decision-making during the pandemic. Nearly 60% of doctors and 65% of nurses said they disagreed with the CDC’s overall pandemic guidance.

Lack of trust can make people resist vaccines and efforts to fight the virus, the authors wrote.

“This will become really relevant when we have ample supply of Pfizer’s antiviral medication,” Mr. Gostin, who directs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown, told this news organization. “The next phase of the pandemic is not to link testing to contact tracing, because we’re way past that, but to link testing to treatment.”

Lack of regional manufacturing of products is also thwarting global progress.

“It is extraordinarily important that our pharmaceutical industry transfer technology in a pandemic,” Mr. Gostin said. “The most glaring failure to do that is the mRNA vaccines. We’ve got this enormously effective vaccine and the two manufacturers – Pfizer and Moderna – are refusing to share the technology with producers in other countries. That keeps coming back to haunt us.”

Another problem: When the vaccines are shared with other countries, they are being delivered close to the date they expire or arriving at a shipyards without warning, so even some of the doses that get delivered are going to waste, Mr. Gostin said.

“It’s one of the greatest moral failures of my lifetime,” he said.

Also a failure is the “jaw-dropping” state of testing 2 years into the pandemic, he said, as people continue to pay high prices for tests or endure long lines.

The U.S. government updated its calculations and ordered 1 billion tests for the general public. The COVIDtests.gov website to order the free tests is now live.

It’s a step in the right direction. Mr. Gostin and Dr. Nuzzo wrote that there is every reason to expect future epidemics that are as serious or more serious than COVID.

“Failure to address clearly observed weaknesses in the COVID-19 response will have preventable adverse health, social, and economic consequences when the next novel outbreak occurs,” they wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States is still breaking records in hospital overcrowding and new cases.

The United States is logging nearly 800,000 cases a day, hospitals are starting to fray, and deaths have topped 850,000. Schools oscillate from remote to in-person learning, polarizing communities.

The vaccines are lifesaving for many, yet frustration mounts as the numbers of unvaccinated people in this country stays relatively stagnant (63% in the United States are fully vaccinated) and other parts of the world have seen hardly a single dose. Africa has the slowest vaccination rate among continents, with only 14% of the population receiving one shot, according to the New York Times tracker.

Yet

Effective vaccines and treatments that can keep people out of the hospital were developed at an astounding pace, and advances in tracking and testing – in both access and effectiveness – are starting to pay off.

Some experts say it’s possible that the raging Omicron surge will slow by late spring, providing some relief and maybe shifting the pandemic to a slower-burning endemic.

But other experts caution to keep our guard up, saying it’s time to settle into a “new normal” and upend the strategy for fighting COVID-19.

Time to change COVID thinking

Three former members of the Biden-Harris Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board wrote recently in JAMA that COVID-19 has now become one of the many viral respiratory diseases that health care providers and patients will manage each year.

The group of experts from the University of Pennsylvania, University of Minnesota, and New York University write that “many of the measures to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (for example, ventilation) will also reduce transmission of other respiratory viruses. Thus, policy makers should retire previous public health categorizations, including deaths from pneumonia and influenza or pneumonia, influenza, and COVID-19, and focus on a new category: the aggregate risk of all respiratory virus infections.”

Other experts, including Amesh Adalja, MD, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, Baltimore, have said it’s been clear since the early days of SARS-CoV-2 that we must learn to live with the virus because it “will be ever present for the remaining history of our species.”

But that doesn’t mean the virus will always have the upper hand. Although the United States has been reaching record numbers of hospitalizations in January, these hospitalizations differ from those of last year – marked by fewer extreme lifesaving measures, fewer deaths, and shorter hospital stays – caused in part by medical and therapeutic advances and in part to the nature of the Omicron variant itself.

One sign of progress, Dr. Adalja said, will be the widespread decoupling of cases from hospitalizations, something that has already happened in countries such as the United Kingdom.

“That’s a reflection of how well they have vaccinated their high-risk population and how poorly we have vaccinated our high-risk population,” he said.

Omicron will bump up natural immunity

Dr. Adalja said though the numbers of unvaccinated in the United States appear to be stuck, Omicron’s sweep will make the difference, leaving behind more natural immunity in the population.

Currently, hospitals are struggling with staffing concerns as a “direct result” of too many unvaccinated people, he said.

Andrew Badley, MD, an infectious diseases specialist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and director of the clinic’s COVID-19 Task Force, said the good news with Omicron is that nearly all people it infects will recover.

Over time, when the body sees foreign antigens repeatedly, the quantity and quality of the antibodies the immune system produces increase and the body becomes better at fighting disease.

So “a large amount of the population will have recovered and have a degree of immunity,” Dr. Badley said.

His optimism is tempered by his belief that “it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

But Dr. Badley still predicts a turnaround. “We’ll see a downturn in COVID in late spring or early summer,” and well into the second quarter of 2022, “we’ll see a reemergence of control.”

Right now, with Omicron, one infected person is infecting three to five others, he said. The hope is that it will eventually reach one-to-one endemic levels.

As for the threat of new variants, Badley said, “it’s not predictable whether they will be stronger or weaker.”

Masks may be around for years

Many experts predict that masks will continue to be part of the national wardrobe for the foreseeable future.

“We will continue to see new cases for years and years to come. Some will respond to that with masks in public places for a very long time. I personally will do so,” Dr. Badley said.

Two mindsets: Inside/outside the hospital

Emily Landon, MD, an infectious disease doctor and the executive medical director of infection prevention and control at University of Chicago Medicine, told this news organization she views the pandemic from two different vantage points.

As a health care provider, she sees her hospital, like others worldwide, overwhelmed. Supplies of a major weapon to help prevent hospitalization, the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab, are running out. Dr. Landon said she has been calling other hospitals to see if they have supplies and, if so, whether Omicron patients can transfer there.

Bottom line: The things they relied on a month ago to keep people out of the hospital are no longer there, she said.

Meanwhile, “We have more COVID patients than we have ever had,” Dr. Landon said.

Last year, UChicago hit a high of 170 people hospitalized with COVID. This year, so far, the peak was 270.

Dr. Landon said she is frustrated when she leaves that overburdened world inside the hospital for the outside world, where people wear no masks or ineffective face coverings and gather unsafely. Although some of that behavior reflects an intention to flout the advice of medical experts, some is caused in part, she said, by the lack of a clear national health strategy and garbled communication from those in charge of public safety.

Americans are deciding for themselves, on an a la carte basis, whether to wear a mask or get tested or travel, and school districts decide individually when it’s time to go virtual.

“People are exhausted from having to do a risk-benefit analysis for every single activity they, their friends, their kids want to participate in,” she said.

U.S. behind in several areas

Despite our self-image as the global leader in science and medicine, the United States stumbled badly in its response to the pandemic, with grave consequences both at home and abroad, experts say.

In a recent commentary in JAMA, Lawrence Gostin, JD, from Georgetown University, Washington, and Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, pointed to several critical shortfalls in the nation’s efforts to control the disease.

One such shortfall is public trust.

This news organization reported in June 2021 that a poll of its readers found that 44% said their trust in the CDC had waned during the pandemic, and 33% said their trust in the FDA had eroded as well.

Health care providers who responded to the poll lost trust as well. About half of the doctors and nurses who responded said they disagreed with the FDA’s decision-making during the pandemic. Nearly 60% of doctors and 65% of nurses said they disagreed with the CDC’s overall pandemic guidance.

Lack of trust can make people resist vaccines and efforts to fight the virus, the authors wrote.

“This will become really relevant when we have ample supply of Pfizer’s antiviral medication,” Mr. Gostin, who directs the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown, told this news organization. “The next phase of the pandemic is not to link testing to contact tracing, because we’re way past that, but to link testing to treatment.”

Lack of regional manufacturing of products is also thwarting global progress.

“It is extraordinarily important that our pharmaceutical industry transfer technology in a pandemic,” Mr. Gostin said. “The most glaring failure to do that is the mRNA vaccines. We’ve got this enormously effective vaccine and the two manufacturers – Pfizer and Moderna – are refusing to share the technology with producers in other countries. That keeps coming back to haunt us.”

Another problem: When the vaccines are shared with other countries, they are being delivered close to the date they expire or arriving at a shipyards without warning, so even some of the doses that get delivered are going to waste, Mr. Gostin said.

“It’s one of the greatest moral failures of my lifetime,” he said.

Also a failure is the “jaw-dropping” state of testing 2 years into the pandemic, he said, as people continue to pay high prices for tests or endure long lines.

The U.S. government updated its calculations and ordered 1 billion tests for the general public. The COVIDtests.gov website to order the free tests is now live.

It’s a step in the right direction. Mr. Gostin and Dr. Nuzzo wrote that there is every reason to expect future epidemics that are as serious or more serious than COVID.

“Failure to address clearly observed weaknesses in the COVID-19 response will have preventable adverse health, social, and economic consequences when the next novel outbreak occurs,” they wrote.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

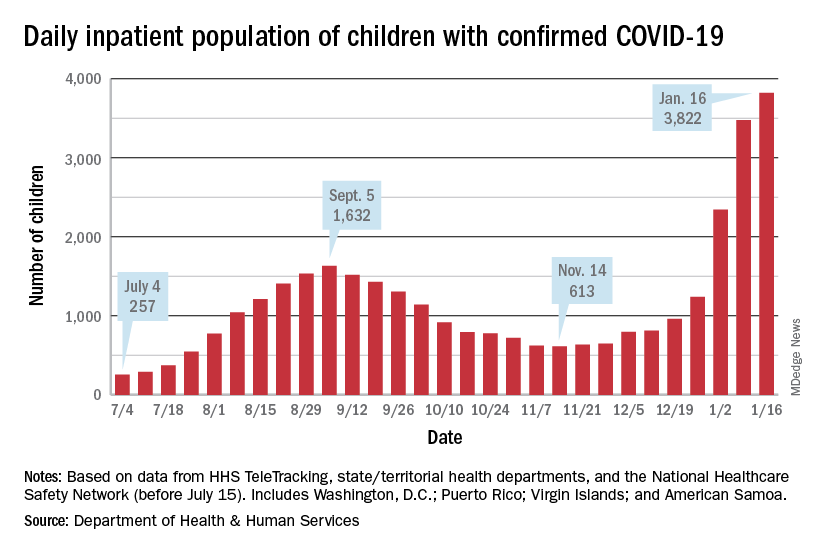

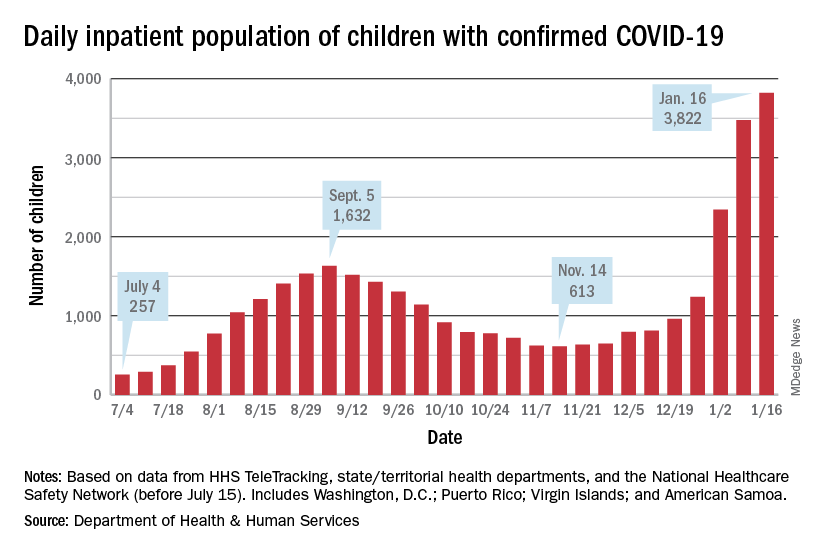

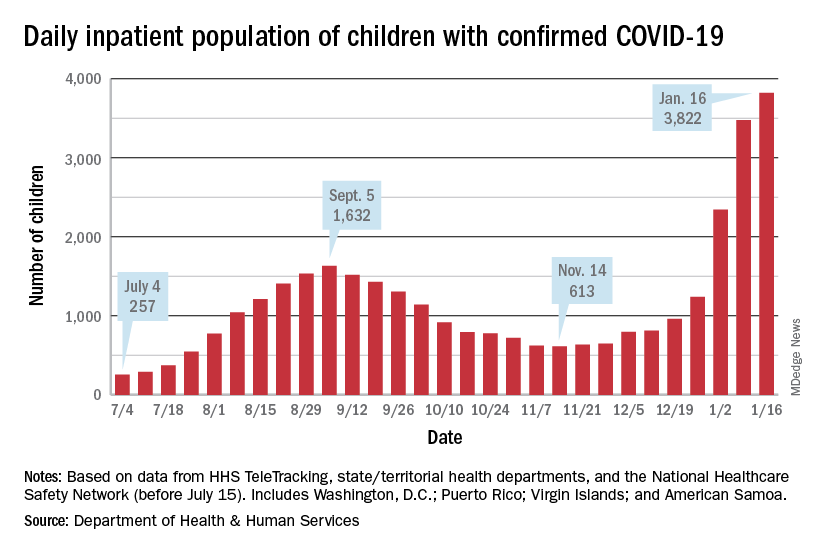

Severe outcomes increased in youth hospitalized after positive COVID-19 test

Approximately 3% of youth who tested positive for COVID-19 in an emergency department setting had severe outcomes after 2 weeks, but this risk was 0.5% among those not admitted to the hospital, based on data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 and younger.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, youth younger than 18 years accounted for fewer than 5% of reported cases, but now account for approximately 25% of positive cases, wrote Anna L. Funk, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and colleagues.

However, the risk of severe outcomes of youth with COVID-19 remains poorly understood and data from large studies are lacking, they noted.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 3,221 children and adolescents who were tested for COVID-19 at one of 41 emergency departments in 10 countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, New Zealand, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain, and the United States between March 2020 and June 2021. Positive infections were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. At 14 days’ follow-up after a positive test, 735 patients (22.8%), were hospitalized, 107 (3.3%) had severe outcomes, and 4 (0.12%) had died. Severe outcomes were significantly more likely in children aged 5-10 years and 10-18 years vs. less than 1 year (odds ratios, 1.60 and 2.39, respectively), and in children with a self-reported chronic illness (OR, 2.34) or a prior episode of pneumonia (OR, 3.15).

Severe outcomes were more likely in patients who presented with symptoms that started 4-7 days before seeking care, compared with those whose symptoms started 0-3 days before seeking care (OR, 2.22).

The researchers also reviewed data from a subgroup of 2,510 individuals who were discharged home from the ED after initial testing. At 14 days’ follow-up, 50 of these patients (2.0%) were hospitalized and 12 (0.5%) had severe outcomes. In addition, the researchers found that the risk of severe outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19–positive youth was nearly four times higher, compared with hospitalized youth who tested negative for COVID-19 (risk difference, 3.9%).

Previous retrospective studies of severe outcomes in children and adolescents with COVID-19 have yielded varying results, in part because of the variation in study populations, the researchers noted in their discussion of the findings. “Our study population provides a risk estimate for youths brought for ED care.” Therefore, “Our lower estimate of severe disease likely reflects our stringent definition, which required the occurrence of complications or specific invasive interventions,” they said.

The study limitations included the potential overestimation of the risk of severe outcomes because patients were recruited in the ED, the researchers noted. Other limitations included variation in regional case definitions, screening criteria, and testing capacity among different sites and time periods. “Thus, 5% of our SARS-CoV-2–positive participants were asymptomatic – most of whom were tested as they were positive contacts of known cases or as part of routine screening procedures,” they said. The findings also are not generalizable to all community EDs and did not account for variants, they added.

However, the results were strengthened by the ability to compare outcomes for children with positive tests to similar children with negative tests, and add to the literature showing an increased risk of severe outcomes for those hospitalized with positive tests, the researchers concluded.

Data may inform clinical decisions

“The data [in the current study] are concerning for severe outcomes for children even prior to the Omicron strain,” said Margaret Thew, DNP, FP-BC, of Children’s Wisconsin-Milwaukee Hospital, in an interview. “Presently, the number of children infected with the Omicron strain is much higher and hospitalizations among children are at their highest since COVID-19 began,” she said. “For medical providers caring for this population, the study sheds light on pediatric patients who may be at higher risk of severe illness when they become infected with COVID-19,” she added.

“I was surprised by how high the number of pediatric patients hospitalized (22%) and the percentage (3%) with severe disease were during this time,” given that the timeline for these data preceded the spread of the Omicron strain, said Ms. Thew. “The risk of prior pneumonia was quite surprising. I do not recall seeing prior pneumonia as a risk factor for more severe COVID-19 with children or adults,” she added.

The take-home messaging for clinicians caring for children and adolescents is the added knowledge of the risk factors for severe outcomes from COVID-19, including the 10-18 age range, chronic illness, prior pneumonia, and longer symptom duration before seeking care in the ED, Ms. Thew emphasized.

However, additional research is needed on the impact of the new strains of COVID-19 on pediatric and adolescent hospitalizations, Ms. Thew said. Research also is needed on the other illnesses that have resulted from COVID-19, including illness requiring antibiotic use or medical interventions or treatments, and on the risk of combined COVID-19 and influenza viruses, she noted.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Alberta Innovates, the Alberta Health Services University of Calgary Clinical Research Fund, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, the COVID-19 Research Accelerator Funding Track (CRAFT) Program at the University of California, Davis, and the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Division of Emergency Medicine Small Grants Program. Lead author Dr. Funk was supported by the University of Calgary Eyes-High Post-Doctoral Research Fund, but had no financial conflicts to disclose. Ms. Thew had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Pediatric News.

Approximately 3% of youth who tested positive for COVID-19 in an emergency department setting had severe outcomes after 2 weeks, but this risk was 0.5% among those not admitted to the hospital, based on data from more than 3,000 individuals aged 18 and younger.

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, youth younger than 18 years accounted for fewer than 5% of reported cases, but now account for approximately 25% of positive cases, wrote Anna L. Funk, PhD, of the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, and colleagues.

However, the risk of severe outcomes of youth with COVID-19 remains poorly understood and data from large studies are lacking, they noted.

In a prospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 3,221 children and adolescents who were tested for COVID-19 at one of 41 emergency departments in 10 countries including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Costa Rica, Italy, New Zealand, Paraguay, Singapore, Spain, and the United States between March 2020 and June 2021. Positive infections were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. At 14 days’ follow-up after a positive test, 735 patients (22.8%), were hospitalized, 107 (3.3%) had severe outcomes, and 4 (0.12%) had died. Severe outcomes were significantly more likely in children aged 5-10 years and 10-18 years vs. less than 1 year (odds ratios, 1.60 and 2.39, respectively), and in children with a self-reported chronic illness (OR, 2.34) or a prior episode of pneumonia (OR, 3.15).

Severe outcomes were more likely in patients who presented with symptoms that started 4-7 days before seeking care, compared with those whose symptoms started 0-3 days before seeking care (OR, 2.22).

The researchers also reviewed data from a subgroup of 2,510 individuals who were discharged home from the ED after initial testing. At 14 days’ follow-up, 50 of these patients (2.0%) were hospitalized and 12 (0.5%) had severe outcomes. In addition, the researchers found that the risk of severe outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19–positive youth was nearly four times higher, compared with hospitalized youth who tested negative for COVID-19 (risk difference, 3.9%).