User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

USPSTF recommends against screening for COPD in asymptomatic adults

There is no apparent benefit to screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in asymptomatic patients, a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes.

The recommendation statement, which was published in the April 5 edition of JAMA, meets Grade D criteria, which the task force defines as having “moderate or high certainty that the service has no benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.”

Led by Dr. Albert L. Siu of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, the 16-member task force “found no studies that directly assessed the effects of screening for COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in asymptomatic adults on morbidity, mortality, or health-related quality of life,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1372-7). “The USPSTF also found no studies that examined the effectiveness of screening on relevant immunization rates.” The five studies identified that assessed the effects of screening on smoking cessation “primarily examined the incremental value of adding spirometry testing to existing smoking cessation programs. One trial showed a statistically significant increase in smoking cessation rates between participants who received explanations of their spirometry results using ‘lung age’ and those who did not. The other four trials did not report any significant differences in smoking abstinence rates.”

The recommendations are based on a systematic review of evidence that was commissioned by the USPSTF and published in the same issue of JAMA. The reviewers set out to determine the accuracy of screening questionnaires and office-based screening pulmonary function testing and the efficacy and harms of treatment of screen-detected COPD. After reviewing 33 studies that met inclusion criteria, five experts led by Dr. Janelle M. Guirguis-Blake found “no direct evidence available to determine the benefits and harms of screening asymptomatic adults for COPD using questionnaires or office-based screening pulmonary function testing or to determine the benefits of treatment in screen-detected populations,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1378-93). “Indirect evidence suggests that the CDQ [COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire] has moderate overall performance for COPD detection. Among patients with mild to moderate COPD, the benefit of pharmacotherapy for reducing exacerbations was modest.”

The USPSTF last published an update on COPD in 2008. That report recommended against screening for COPD with spirometry in asymptomatic adults, a Grade D recommendation based on the conclusion that screening for COPD had no net benefit and large associated costs.

According to the current recommendations, an estimated 14% of U.S. adults aged 40-79 years have COPD, and it is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Although postbronchodilator spirometry is required to make a definitive diagnosis, “prescreening questionnaires can elicit current symptoms and previous exposures to harmful particles or gases,” Dr. Siu and his fellow task force members wrote.

They acknowledged limitations of the recommendations, including the fact that many of the reviewed studies did not report results separately by current versus former smokers. “Future studies that stratify risk by smoking status could help identify different risk groups that may benefit from screening,” they wrote “In addition, trials are needed that assess the effects of screening among current and previous smokers in primary care on long-term health outcomes. Long-term trials of treatment of COPD in screen-detected patients are also needed. Better treatment options for COPD and long-term epidemiological studies of the natural history and heterogeneity of COPD progression could also help identify patients who are at greatest risk for clinical deterioration.”

The systematic review was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under a contract to support the USPSTF. The authors of the recommendation statement reported having no financial disclosures.

The USPSTF Recommendation Statement “encourages clinicians ... to pursue active case-finding for COPD in patients with risk factors, such as exposure to cigarette smoke.” These recommendations require consideration of the difference between screening – testing large numbers of apparently healthy people to detect unrecognized disease at an earlier stage – and case-finding – evaluating subgroups of people at increased risk of having a disease to make a diagnosis earlier than would occur by waiting for them to present with symptoms or signs.

The group that conducted the systematic review for the USPSTF explicitly excluded analyses of studies that identified previously undiagnosed patients with severe airflow obstruction given their relative rarity in population-based spirometric screening studies (less than 5%). Currently available therapies have been shown to improve multiple measures of disease burden in this group, and accurate diagnosis and the institution of appropriate treatment have been recommended for these patients. Thus, case-finding approaches that can identify these patients with more severe disease in the primary care setting may be warranted.

The USPSTF has done an admirable job in reviewing and interpreting available evidence, and the recommendation against screening of truly asymptomatic patients for COPD is well reasoned, as such screening has not been shown to result in a clear net benefit. More research is needed, however, with respect to the “active case-finding for COPD,” among patients with risk factors. This is encouraged by the USPSTF report. The effect of COPD case-finding approaches on health outcomes and health care expenditure has yet to be demonstrated. Additional investigation is required to develop innovative formats to identify persons with undiagnosed yet more severe COPD, or risk of developing severe airflow obstruction that may be amenable to available treatments. Prospective examination of the benefit of such case-finding approaches on health care delivery and clinical outcomes is vital. Furthermore, if future therapies are developed that alter natural history and long-term health outcomes of “early” or “mild” COPD, the use of case-finding or even screening approaches may need to be reconsidered.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared in the April 5 issue of JAMA (315[13]:1343-4). Dr. Fernando J. Martinez is with the department of medicine at Cornell University, New York. Dr. George T. O’Connor is with the division of pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. He is also JAMA’s associate editor. Dr. Martinez reported having numerous financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry. Dr. O’Connor reported receiving research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute via a subcontract from Dimagi, in which he had no financial interest.

The USPSTF Recommendation Statement “encourages clinicians ... to pursue active case-finding for COPD in patients with risk factors, such as exposure to cigarette smoke.” These recommendations require consideration of the difference between screening – testing large numbers of apparently healthy people to detect unrecognized disease at an earlier stage – and case-finding – evaluating subgroups of people at increased risk of having a disease to make a diagnosis earlier than would occur by waiting for them to present with symptoms or signs.

The group that conducted the systematic review for the USPSTF explicitly excluded analyses of studies that identified previously undiagnosed patients with severe airflow obstruction given their relative rarity in population-based spirometric screening studies (less than 5%). Currently available therapies have been shown to improve multiple measures of disease burden in this group, and accurate diagnosis and the institution of appropriate treatment have been recommended for these patients. Thus, case-finding approaches that can identify these patients with more severe disease in the primary care setting may be warranted.

The USPSTF has done an admirable job in reviewing and interpreting available evidence, and the recommendation against screening of truly asymptomatic patients for COPD is well reasoned, as such screening has not been shown to result in a clear net benefit. More research is needed, however, with respect to the “active case-finding for COPD,” among patients with risk factors. This is encouraged by the USPSTF report. The effect of COPD case-finding approaches on health outcomes and health care expenditure has yet to be demonstrated. Additional investigation is required to develop innovative formats to identify persons with undiagnosed yet more severe COPD, or risk of developing severe airflow obstruction that may be amenable to available treatments. Prospective examination of the benefit of such case-finding approaches on health care delivery and clinical outcomes is vital. Furthermore, if future therapies are developed that alter natural history and long-term health outcomes of “early” or “mild” COPD, the use of case-finding or even screening approaches may need to be reconsidered.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared in the April 5 issue of JAMA (315[13]:1343-4). Dr. Fernando J. Martinez is with the department of medicine at Cornell University, New York. Dr. George T. O’Connor is with the division of pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. He is also JAMA’s associate editor. Dr. Martinez reported having numerous financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry. Dr. O’Connor reported receiving research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute via a subcontract from Dimagi, in which he had no financial interest.

The USPSTF Recommendation Statement “encourages clinicians ... to pursue active case-finding for COPD in patients with risk factors, such as exposure to cigarette smoke.” These recommendations require consideration of the difference between screening – testing large numbers of apparently healthy people to detect unrecognized disease at an earlier stage – and case-finding – evaluating subgroups of people at increased risk of having a disease to make a diagnosis earlier than would occur by waiting for them to present with symptoms or signs.

The group that conducted the systematic review for the USPSTF explicitly excluded analyses of studies that identified previously undiagnosed patients with severe airflow obstruction given their relative rarity in population-based spirometric screening studies (less than 5%). Currently available therapies have been shown to improve multiple measures of disease burden in this group, and accurate diagnosis and the institution of appropriate treatment have been recommended for these patients. Thus, case-finding approaches that can identify these patients with more severe disease in the primary care setting may be warranted.

The USPSTF has done an admirable job in reviewing and interpreting available evidence, and the recommendation against screening of truly asymptomatic patients for COPD is well reasoned, as such screening has not been shown to result in a clear net benefit. More research is needed, however, with respect to the “active case-finding for COPD,” among patients with risk factors. This is encouraged by the USPSTF report. The effect of COPD case-finding approaches on health outcomes and health care expenditure has yet to be demonstrated. Additional investigation is required to develop innovative formats to identify persons with undiagnosed yet more severe COPD, or risk of developing severe airflow obstruction that may be amenable to available treatments. Prospective examination of the benefit of such case-finding approaches on health care delivery and clinical outcomes is vital. Furthermore, if future therapies are developed that alter natural history and long-term health outcomes of “early” or “mild” COPD, the use of case-finding or even screening approaches may need to be reconsidered.

These comments were extracted from an editorial that appeared in the April 5 issue of JAMA (315[13]:1343-4). Dr. Fernando J. Martinez is with the department of medicine at Cornell University, New York. Dr. George T. O’Connor is with the division of pulmonary, allergy, sleep, and critical care medicine at Boston University School of Medicine. He is also JAMA’s associate editor. Dr. Martinez reported having numerous financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry. Dr. O’Connor reported receiving research funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute via a subcontract from Dimagi, in which he had no financial interest.

There is no apparent benefit to screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in asymptomatic patients, a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes.

The recommendation statement, which was published in the April 5 edition of JAMA, meets Grade D criteria, which the task force defines as having “moderate or high certainty that the service has no benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.”

Led by Dr. Albert L. Siu of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, the 16-member task force “found no studies that directly assessed the effects of screening for COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in asymptomatic adults on morbidity, mortality, or health-related quality of life,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1372-7). “The USPSTF also found no studies that examined the effectiveness of screening on relevant immunization rates.” The five studies identified that assessed the effects of screening on smoking cessation “primarily examined the incremental value of adding spirometry testing to existing smoking cessation programs. One trial showed a statistically significant increase in smoking cessation rates between participants who received explanations of their spirometry results using ‘lung age’ and those who did not. The other four trials did not report any significant differences in smoking abstinence rates.”

The recommendations are based on a systematic review of evidence that was commissioned by the USPSTF and published in the same issue of JAMA. The reviewers set out to determine the accuracy of screening questionnaires and office-based screening pulmonary function testing and the efficacy and harms of treatment of screen-detected COPD. After reviewing 33 studies that met inclusion criteria, five experts led by Dr. Janelle M. Guirguis-Blake found “no direct evidence available to determine the benefits and harms of screening asymptomatic adults for COPD using questionnaires or office-based screening pulmonary function testing or to determine the benefits of treatment in screen-detected populations,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1378-93). “Indirect evidence suggests that the CDQ [COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire] has moderate overall performance for COPD detection. Among patients with mild to moderate COPD, the benefit of pharmacotherapy for reducing exacerbations was modest.”

The USPSTF last published an update on COPD in 2008. That report recommended against screening for COPD with spirometry in asymptomatic adults, a Grade D recommendation based on the conclusion that screening for COPD had no net benefit and large associated costs.

According to the current recommendations, an estimated 14% of U.S. adults aged 40-79 years have COPD, and it is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Although postbronchodilator spirometry is required to make a definitive diagnosis, “prescreening questionnaires can elicit current symptoms and previous exposures to harmful particles or gases,” Dr. Siu and his fellow task force members wrote.

They acknowledged limitations of the recommendations, including the fact that many of the reviewed studies did not report results separately by current versus former smokers. “Future studies that stratify risk by smoking status could help identify different risk groups that may benefit from screening,” they wrote “In addition, trials are needed that assess the effects of screening among current and previous smokers in primary care on long-term health outcomes. Long-term trials of treatment of COPD in screen-detected patients are also needed. Better treatment options for COPD and long-term epidemiological studies of the natural history and heterogeneity of COPD progression could also help identify patients who are at greatest risk for clinical deterioration.”

The systematic review was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under a contract to support the USPSTF. The authors of the recommendation statement reported having no financial disclosures.

There is no apparent benefit to screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in asymptomatic patients, a new recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes.

The recommendation statement, which was published in the April 5 edition of JAMA, meets Grade D criteria, which the task force defines as having “moderate or high certainty that the service has no benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits.”

Led by Dr. Albert L. Siu of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, the 16-member task force “found no studies that directly assessed the effects of screening for COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] in asymptomatic adults on morbidity, mortality, or health-related quality of life,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1372-7). “The USPSTF also found no studies that examined the effectiveness of screening on relevant immunization rates.” The five studies identified that assessed the effects of screening on smoking cessation “primarily examined the incremental value of adding spirometry testing to existing smoking cessation programs. One trial showed a statistically significant increase in smoking cessation rates between participants who received explanations of their spirometry results using ‘lung age’ and those who did not. The other four trials did not report any significant differences in smoking abstinence rates.”

The recommendations are based on a systematic review of evidence that was commissioned by the USPSTF and published in the same issue of JAMA. The reviewers set out to determine the accuracy of screening questionnaires and office-based screening pulmonary function testing and the efficacy and harms of treatment of screen-detected COPD. After reviewing 33 studies that met inclusion criteria, five experts led by Dr. Janelle M. Guirguis-Blake found “no direct evidence available to determine the benefits and harms of screening asymptomatic adults for COPD using questionnaires or office-based screening pulmonary function testing or to determine the benefits of treatment in screen-detected populations,” they wrote (JAMA. 2016 Apr; 315[13]:1378-93). “Indirect evidence suggests that the CDQ [COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire] has moderate overall performance for COPD detection. Among patients with mild to moderate COPD, the benefit of pharmacotherapy for reducing exacerbations was modest.”

The USPSTF last published an update on COPD in 2008. That report recommended against screening for COPD with spirometry in asymptomatic adults, a Grade D recommendation based on the conclusion that screening for COPD had no net benefit and large associated costs.

According to the current recommendations, an estimated 14% of U.S. adults aged 40-79 years have COPD, and it is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. Although postbronchodilator spirometry is required to make a definitive diagnosis, “prescreening questionnaires can elicit current symptoms and previous exposures to harmful particles or gases,” Dr. Siu and his fellow task force members wrote.

They acknowledged limitations of the recommendations, including the fact that many of the reviewed studies did not report results separately by current versus former smokers. “Future studies that stratify risk by smoking status could help identify different risk groups that may benefit from screening,” they wrote “In addition, trials are needed that assess the effects of screening among current and previous smokers in primary care on long-term health outcomes. Long-term trials of treatment of COPD in screen-detected patients are also needed. Better treatment options for COPD and long-term epidemiological studies of the natural history and heterogeneity of COPD progression could also help identify patients who are at greatest risk for clinical deterioration.”

The systematic review was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality under a contract to support the USPSTF. The authors of the recommendation statement reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

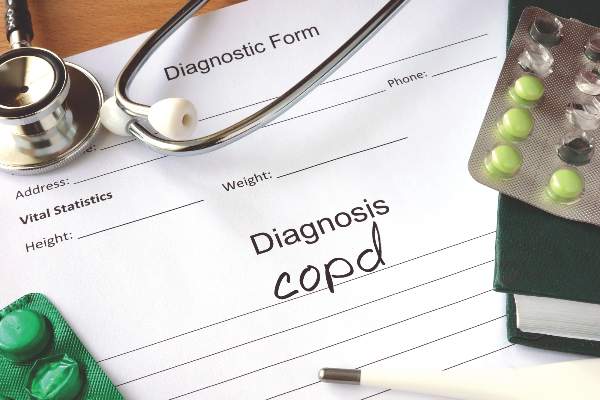

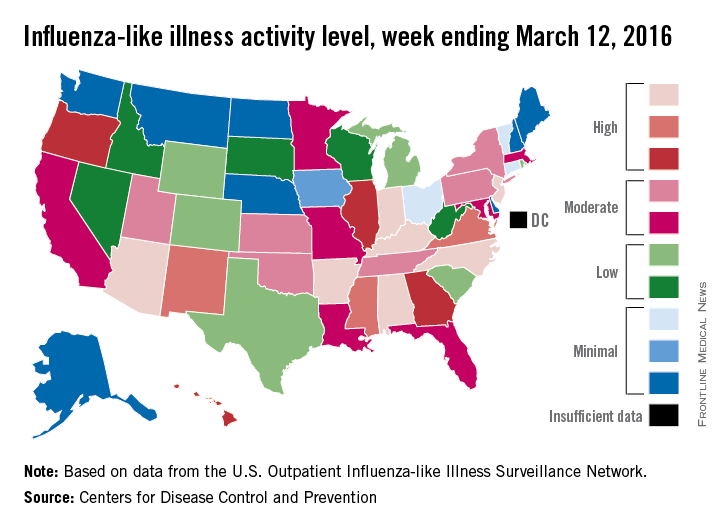

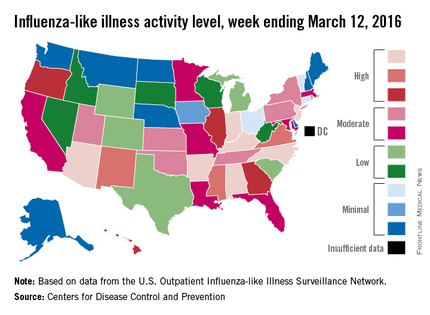

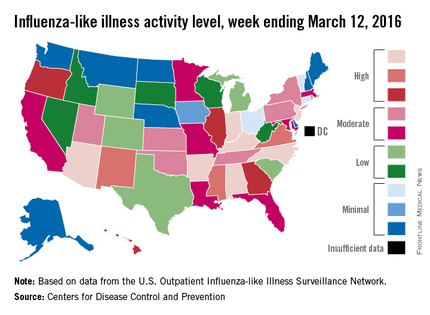

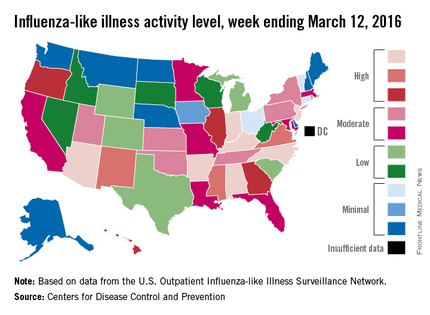

U.S. flu activity continues downward trend

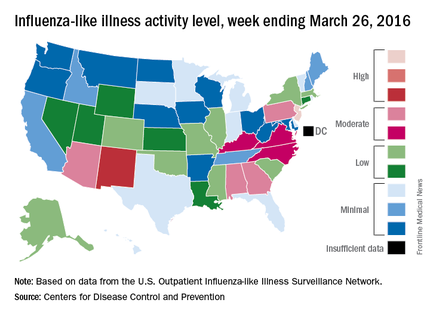

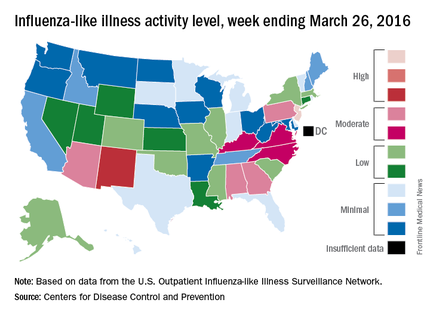

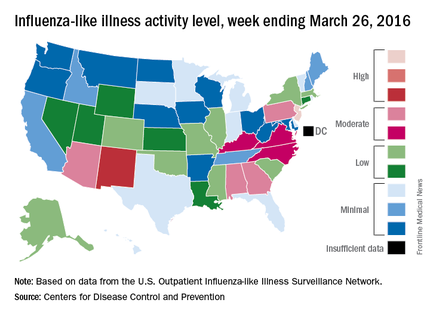

Influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States continued to drop during the week ending March 26, 2016, with only one state still at the highest level, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That one state was New Jersey, which was at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity. One state at level 10 was down from three states the week before and seven states 2 weeks earlier. Also down for a second consecutive week was the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI, which was 2.9% for the most recent week, compared with 3.2% the previous week and a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12, the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) reported.

The only other state in the “high” range for the week ending March 26 was New Mexico at level 8. States in the “moderate” range were Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania at level 7 and Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia at level 6, according to data from ILINet.

Three flu-related pediatric deaths were reported to CDC during the week, but two occurred the previous week and one occurred in February. That brings the total of flu-related pediatric deaths to 33 for the 2015-2016 influenza season, the CDC said. However, 7.7% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.2%.

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate for the season of 21.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (54.5 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (31.4 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (29.3 per 100,000 population).

Influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States continued to drop during the week ending March 26, 2016, with only one state still at the highest level, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That one state was New Jersey, which was at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity. One state at level 10 was down from three states the week before and seven states 2 weeks earlier. Also down for a second consecutive week was the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI, which was 2.9% for the most recent week, compared with 3.2% the previous week and a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12, the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) reported.

The only other state in the “high” range for the week ending March 26 was New Mexico at level 8. States in the “moderate” range were Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania at level 7 and Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia at level 6, according to data from ILINet.

Three flu-related pediatric deaths were reported to CDC during the week, but two occurred the previous week and one occurred in February. That brings the total of flu-related pediatric deaths to 33 for the 2015-2016 influenza season, the CDC said. However, 7.7% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.2%.

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate for the season of 21.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (54.5 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (31.4 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (29.3 per 100,000 population).

Influenza-like illness (ILI) activity in the United States continued to drop during the week ending March 26, 2016, with only one state still at the highest level, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That one state was New Jersey, which was at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity. One state at level 10 was down from three states the week before and seven states 2 weeks earlier. Also down for a second consecutive week was the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI, which was 2.9% for the most recent week, compared with 3.2% the previous week and a season high of 3.7% for the week ending March 12, the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) reported.

The only other state in the “high” range for the week ending March 26 was New Mexico at level 8. States in the “moderate” range were Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, and Pennsylvania at level 7 and Kentucky, North Carolina, and Virginia at level 6, according to data from ILINet.

Three flu-related pediatric deaths were reported to CDC during the week, but two occurred the previous week and one occurred in February. That brings the total of flu-related pediatric deaths to 33 for the 2015-2016 influenza season, the CDC said. However, 7.7% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.2%.

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate for the season of 21.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged 65 years or older (54.5 per 100,000 population), followed by adults aged 50-64 (31.4 per 100,000 population) and children aged 0-4 years (29.3 per 100,000 population).

Blood test predicts progression to active TB

An international team of researchers has developed a blood test that identifies the 5%-10% of patients infected with latent tuberculosis who are likely to progress to active TB, up to 18 months before they show any sign of illness, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Worldwide, one-third of the apparently healthy population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but only a fraction will develop active TB during their lifetimes. Until now there has been no way to predict which of these people will progress and become ill. Treating all latently infected people in endemic areas for the necessary 6-9 months isn’t feasible, but a test that distinguishes which cases will become active would allow targeted preventive therapy. This could potentially interrupt the global spread of TB, said Daniel E. Zak, Ph.D. of the Center for Infectious Disease Research, Seattle, and his associates.

Such a test also might be used to assess treatment response, as well as to enroll only the highest-risk carriers of M. tuberculosis in trials of new drugs and vaccines, they added.

The investigators began by analyzing gene expression in peripheral whole-blood samples from 6,363 apparently healthy adolescents participating in a South African cohort study who were followed for 2-4 years for the development of active TB. They compared RNA-sequencing data from 46 participants who developed active TB against that from 107 matched control subjects who remained healthy and identified a candidate 16-gene risk signature for TB progression. “Robust discrimination between progressors and controls based on the expression of the gene pairs in the signature was readily apparent,” the researchers said.

In this subgroup of patients, the risk signature had a 71.2% sensitivity for predicting active TB during the 6 months preceding diagnosis, a 62.9% sensitivity during the 12 months preceding diagnosis, and a 47.7% sensitivity during the 18 months preceding diagnosis. The specificity was 80.6%.

To validate their findings, the investigators adapted the risk signature to a more practical PCR platform and used it to predict the risk of active TB in the remainder of the study population. The risk signature remained comparably sensitive and specific in this analysis.

To validate their findings in an independent cohort, Dr. Zak and his associates analyzed whole-blood samples from 4,466 apparently healthy adults from South Africa and the Gambia who were participating in a study of household contacts of patients with newly diagnosed active TB. During follow-up, 43 progressors and 172 control subjects were identified at the South African study site, and 30 progressors and 129 control subjects were identified at the Gambian study site. The risk signature again reliably distinguished patients who progressed from latent to active TB from those who didn’t progress, months before any sign of illness surfaced.

“When applied to combined data from 4 studies of HIV-uninfected South African adults involving 130 prevalent TB cases and 230 controls, the signature discriminated between patients with active TB and controls with 87% sensitivity and 97% specificity,” the investigators noted.

Adapting the risk signature further to microarrays so that it could be used in other datasets, the researchers found that it readily distinguished latent from active TB infection in stored samples from more cohorts from the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Malawi. In these cases the risk signature also distinguished active TB from other pulmonary diseases and from other diseases of childhood, and did so regardless of whether the study subjects were coinfected with HIV or not. “Finally, applying the signature to data from a treatment study showed that the active TB signature gradually disappears during 6 months of therapy,” Dr. Zak and his associates wrote (Lancet 2016 March 23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01316-1).

These latter observations suggest that the risk signature may reflect the TB bacterial load in the lung.

The study results were particularly encouraging given the marked diversity among these study populations. The participants had different age ranges, different infection or exposure status, distinct ethnic and genetic backgrounds, different local epidemiology, and different circulating strains of M. tuberculosis. “Our results … pave the way for the establishment of diagnostic methods that are scalable and inexpensive. An important first step would be to test whether the signature can predict TB in the general population, rather than the select populations included in this project,” the investigators added.

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the South African Medical Research Council, and Aeras. Dr. Hanekom and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The current TB epidemic is sustained by the emergence of new cases from the 2 billion people worldwide who have latent TB infection, and from the subsequent infection of their contacts. A test that identifies which people with latent infection will progress to active infection would transform TB control by allowing targeted treatment that would prevent these new cases from emerging.

Another significant finding from the work of Dr. Zak and his associates is that differences in gene expression were detected months before TB symptoms developed. This suggests that progressors have an immune response well before they are diagnosed, that their immune response differs from that of people who remain well, and that the progression from latent to active TB infection is a continuum in the battle between host and pathogen.

Dr. Michael Levin and Dr. Myrsini Kaforou are in the section for pediatric infectious diseases at Imperial College London. They reported being members of an EU-funded TB vaccine consortium and previously worked on an EU-funded study of TB biomarkers, both of which included some of Dr. Zak’s associates. Dr. Levin and Dr. Kaforou made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Zak’s report (Lancet. 2016 Mar 23. doi: 10.1016/S50140-6736[16]00165-3).

The current TB epidemic is sustained by the emergence of new cases from the 2 billion people worldwide who have latent TB infection, and from the subsequent infection of their contacts. A test that identifies which people with latent infection will progress to active infection would transform TB control by allowing targeted treatment that would prevent these new cases from emerging.

Another significant finding from the work of Dr. Zak and his associates is that differences in gene expression were detected months before TB symptoms developed. This suggests that progressors have an immune response well before they are diagnosed, that their immune response differs from that of people who remain well, and that the progression from latent to active TB infection is a continuum in the battle between host and pathogen.

Dr. Michael Levin and Dr. Myrsini Kaforou are in the section for pediatric infectious diseases at Imperial College London. They reported being members of an EU-funded TB vaccine consortium and previously worked on an EU-funded study of TB biomarkers, both of which included some of Dr. Zak’s associates. Dr. Levin and Dr. Kaforou made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Zak’s report (Lancet. 2016 Mar 23. doi: 10.1016/S50140-6736[16]00165-3).

The current TB epidemic is sustained by the emergence of new cases from the 2 billion people worldwide who have latent TB infection, and from the subsequent infection of their contacts. A test that identifies which people with latent infection will progress to active infection would transform TB control by allowing targeted treatment that would prevent these new cases from emerging.

Another significant finding from the work of Dr. Zak and his associates is that differences in gene expression were detected months before TB symptoms developed. This suggests that progressors have an immune response well before they are diagnosed, that their immune response differs from that of people who remain well, and that the progression from latent to active TB infection is a continuum in the battle between host and pathogen.

Dr. Michael Levin and Dr. Myrsini Kaforou are in the section for pediatric infectious diseases at Imperial College London. They reported being members of an EU-funded TB vaccine consortium and previously worked on an EU-funded study of TB biomarkers, both of which included some of Dr. Zak’s associates. Dr. Levin and Dr. Kaforou made these remarks in an editorial comment accompanying Dr. Zak’s report (Lancet. 2016 Mar 23. doi: 10.1016/S50140-6736[16]00165-3).

An international team of researchers has developed a blood test that identifies the 5%-10% of patients infected with latent tuberculosis who are likely to progress to active TB, up to 18 months before they show any sign of illness, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Worldwide, one-third of the apparently healthy population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but only a fraction will develop active TB during their lifetimes. Until now there has been no way to predict which of these people will progress and become ill. Treating all latently infected people in endemic areas for the necessary 6-9 months isn’t feasible, but a test that distinguishes which cases will become active would allow targeted preventive therapy. This could potentially interrupt the global spread of TB, said Daniel E. Zak, Ph.D. of the Center for Infectious Disease Research, Seattle, and his associates.

Such a test also might be used to assess treatment response, as well as to enroll only the highest-risk carriers of M. tuberculosis in trials of new drugs and vaccines, they added.

The investigators began by analyzing gene expression in peripheral whole-blood samples from 6,363 apparently healthy adolescents participating in a South African cohort study who were followed for 2-4 years for the development of active TB. They compared RNA-sequencing data from 46 participants who developed active TB against that from 107 matched control subjects who remained healthy and identified a candidate 16-gene risk signature for TB progression. “Robust discrimination between progressors and controls based on the expression of the gene pairs in the signature was readily apparent,” the researchers said.

In this subgroup of patients, the risk signature had a 71.2% sensitivity for predicting active TB during the 6 months preceding diagnosis, a 62.9% sensitivity during the 12 months preceding diagnosis, and a 47.7% sensitivity during the 18 months preceding diagnosis. The specificity was 80.6%.

To validate their findings, the investigators adapted the risk signature to a more practical PCR platform and used it to predict the risk of active TB in the remainder of the study population. The risk signature remained comparably sensitive and specific in this analysis.

To validate their findings in an independent cohort, Dr. Zak and his associates analyzed whole-blood samples from 4,466 apparently healthy adults from South Africa and the Gambia who were participating in a study of household contacts of patients with newly diagnosed active TB. During follow-up, 43 progressors and 172 control subjects were identified at the South African study site, and 30 progressors and 129 control subjects were identified at the Gambian study site. The risk signature again reliably distinguished patients who progressed from latent to active TB from those who didn’t progress, months before any sign of illness surfaced.

“When applied to combined data from 4 studies of HIV-uninfected South African adults involving 130 prevalent TB cases and 230 controls, the signature discriminated between patients with active TB and controls with 87% sensitivity and 97% specificity,” the investigators noted.

Adapting the risk signature further to microarrays so that it could be used in other datasets, the researchers found that it readily distinguished latent from active TB infection in stored samples from more cohorts from the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Malawi. In these cases the risk signature also distinguished active TB from other pulmonary diseases and from other diseases of childhood, and did so regardless of whether the study subjects were coinfected with HIV or not. “Finally, applying the signature to data from a treatment study showed that the active TB signature gradually disappears during 6 months of therapy,” Dr. Zak and his associates wrote (Lancet 2016 March 23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01316-1).

These latter observations suggest that the risk signature may reflect the TB bacterial load in the lung.

The study results were particularly encouraging given the marked diversity among these study populations. The participants had different age ranges, different infection or exposure status, distinct ethnic and genetic backgrounds, different local epidemiology, and different circulating strains of M. tuberculosis. “Our results … pave the way for the establishment of diagnostic methods that are scalable and inexpensive. An important first step would be to test whether the signature can predict TB in the general population, rather than the select populations included in this project,” the investigators added.

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the South African Medical Research Council, and Aeras. Dr. Hanekom and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

An international team of researchers has developed a blood test that identifies the 5%-10% of patients infected with latent tuberculosis who are likely to progress to active TB, up to 18 months before they show any sign of illness, according to a report published in the Lancet.

Worldwide, one-third of the apparently healthy population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but only a fraction will develop active TB during their lifetimes. Until now there has been no way to predict which of these people will progress and become ill. Treating all latently infected people in endemic areas for the necessary 6-9 months isn’t feasible, but a test that distinguishes which cases will become active would allow targeted preventive therapy. This could potentially interrupt the global spread of TB, said Daniel E. Zak, Ph.D. of the Center for Infectious Disease Research, Seattle, and his associates.

Such a test also might be used to assess treatment response, as well as to enroll only the highest-risk carriers of M. tuberculosis in trials of new drugs and vaccines, they added.

The investigators began by analyzing gene expression in peripheral whole-blood samples from 6,363 apparently healthy adolescents participating in a South African cohort study who were followed for 2-4 years for the development of active TB. They compared RNA-sequencing data from 46 participants who developed active TB against that from 107 matched control subjects who remained healthy and identified a candidate 16-gene risk signature for TB progression. “Robust discrimination between progressors and controls based on the expression of the gene pairs in the signature was readily apparent,” the researchers said.

In this subgroup of patients, the risk signature had a 71.2% sensitivity for predicting active TB during the 6 months preceding diagnosis, a 62.9% sensitivity during the 12 months preceding diagnosis, and a 47.7% sensitivity during the 18 months preceding diagnosis. The specificity was 80.6%.

To validate their findings, the investigators adapted the risk signature to a more practical PCR platform and used it to predict the risk of active TB in the remainder of the study population. The risk signature remained comparably sensitive and specific in this analysis.

To validate their findings in an independent cohort, Dr. Zak and his associates analyzed whole-blood samples from 4,466 apparently healthy adults from South Africa and the Gambia who were participating in a study of household contacts of patients with newly diagnosed active TB. During follow-up, 43 progressors and 172 control subjects were identified at the South African study site, and 30 progressors and 129 control subjects were identified at the Gambian study site. The risk signature again reliably distinguished patients who progressed from latent to active TB from those who didn’t progress, months before any sign of illness surfaced.

“When applied to combined data from 4 studies of HIV-uninfected South African adults involving 130 prevalent TB cases and 230 controls, the signature discriminated between patients with active TB and controls with 87% sensitivity and 97% specificity,” the investigators noted.

Adapting the risk signature further to microarrays so that it could be used in other datasets, the researchers found that it readily distinguished latent from active TB infection in stored samples from more cohorts from the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Malawi. In these cases the risk signature also distinguished active TB from other pulmonary diseases and from other diseases of childhood, and did so regardless of whether the study subjects were coinfected with HIV or not. “Finally, applying the signature to data from a treatment study showed that the active TB signature gradually disappears during 6 months of therapy,” Dr. Zak and his associates wrote (Lancet 2016 March 23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736[15]01316-1).

These latter observations suggest that the risk signature may reflect the TB bacterial load in the lung.

The study results were particularly encouraging given the marked diversity among these study populations. The participants had different age ranges, different infection or exposure status, distinct ethnic and genetic backgrounds, different local epidemiology, and different circulating strains of M. tuberculosis. “Our results … pave the way for the establishment of diagnostic methods that are scalable and inexpensive. An important first step would be to test whether the signature can predict TB in the general population, rather than the select populations included in this project,” the investigators added.

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the South African Medical Research Council, and Aeras. Dr. Hanekom and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Researchers have developed a blood test that identifies the 5%-10% of patients infected with latent tuberculosis who will progress to active TB.

Major finding: The TB-RNA risk signature had a 71.2% sensitivity for predicting active TB during the 6 months preceding diagnosis, a 62.9% sensitivity during the 12 months preceding diagnosis, and a 47.7% sensitivity during the 18 months preceding diagnosis.

Data source: A prospective cohort study to develop (6,363 patients) and validate (4,466 patients) a method of testing whole blood for an M. tuberculosis RNA signature.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the European Union, the South African Medical Research Council, and Aeras. Dr. Hanekom and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Number of U.S. tuberculosis cases increased in 2015

For the first time in 20 years, incidence of tuberculosis in the United States increased slightly in 2015, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB were reported in the United States, up 1.7% from the 9,406 cases reported in 2014. Texas saw the largest total increase in TB cases, going from 1,269 cases in 2014 to 1,334 cases in 2015, followed by South Carolina and Michigan, which both had 25 more TB cases in 2015 than in 2014. Vermont saw the largest relative increase, going from two cases in 2014 to seven cases in 2015, an increase of 250%.

Among U.S.-born patients, the largest number of TB cases were reported in black non-Hispanics, although the incidence rate was highest in Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders at 8.4/100,000 people. For foreign-born patients, Mexico was the most common origin country, followed by the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China. Incidence rate was significantly higher for patients from Asian countries than from any other region.

“Resuming declines in TB incidence will require more comprehensive public health approaches, both globally and domestically. These include increasing case detection and cure rates globally, reducing TB transmission in institutional settings such as health care settings and correctional facilities, and increasing detection and treatment of preexisting latent TB infection among the U.S. populations most affected by TB,” the CDC investigators said.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6511a2).

For the first time in 20 years, incidence of tuberculosis in the United States increased slightly in 2015, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB were reported in the United States, up 1.7% from the 9,406 cases reported in 2014. Texas saw the largest total increase in TB cases, going from 1,269 cases in 2014 to 1,334 cases in 2015, followed by South Carolina and Michigan, which both had 25 more TB cases in 2015 than in 2014. Vermont saw the largest relative increase, going from two cases in 2014 to seven cases in 2015, an increase of 250%.

Among U.S.-born patients, the largest number of TB cases were reported in black non-Hispanics, although the incidence rate was highest in Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders at 8.4/100,000 people. For foreign-born patients, Mexico was the most common origin country, followed by the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China. Incidence rate was significantly higher for patients from Asian countries than from any other region.

“Resuming declines in TB incidence will require more comprehensive public health approaches, both globally and domestically. These include increasing case detection and cure rates globally, reducing TB transmission in institutional settings such as health care settings and correctional facilities, and increasing detection and treatment of preexisting latent TB infection among the U.S. populations most affected by TB,” the CDC investigators said.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6511a2).

For the first time in 20 years, incidence of tuberculosis in the United States increased slightly in 2015, according to investigators from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, 9,563 cases of TB were reported in the United States, up 1.7% from the 9,406 cases reported in 2014. Texas saw the largest total increase in TB cases, going from 1,269 cases in 2014 to 1,334 cases in 2015, followed by South Carolina and Michigan, which both had 25 more TB cases in 2015 than in 2014. Vermont saw the largest relative increase, going from two cases in 2014 to seven cases in 2015, an increase of 250%.

Among U.S.-born patients, the largest number of TB cases were reported in black non-Hispanics, although the incidence rate was highest in Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders at 8.4/100,000 people. For foreign-born patients, Mexico was the most common origin country, followed by the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China. Incidence rate was significantly higher for patients from Asian countries than from any other region.

“Resuming declines in TB incidence will require more comprehensive public health approaches, both globally and domestically. These include increasing case detection and cure rates globally, reducing TB transmission in institutional settings such as health care settings and correctional facilities, and increasing detection and treatment of preexisting latent TB infection among the U.S. populations most affected by TB,” the CDC investigators said.

Find the full report in the MMWR (doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6511a2).

FROM THE MMWR

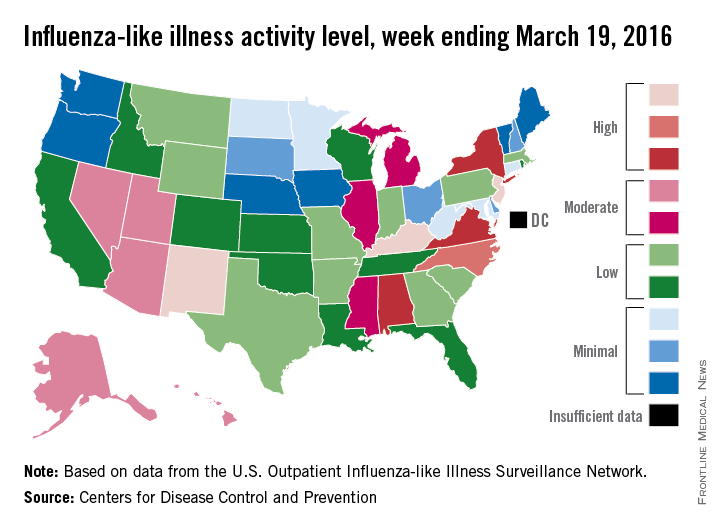

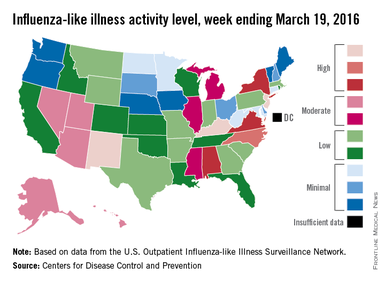

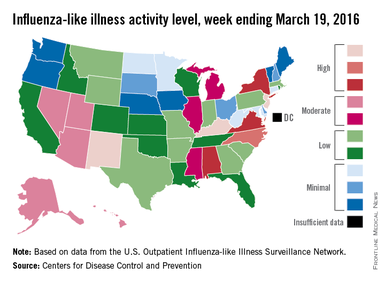

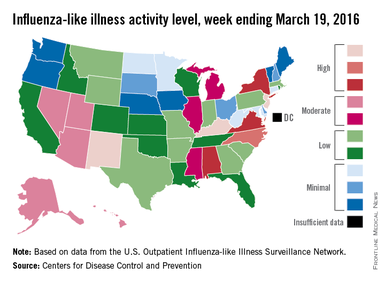

U.S. flu activity may be waning

The 2015-2016 U.S. flu season may have reached its peak. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) dropped to 3.2% for the week ending March 19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The drop came after 9 consecutive weeks without a decrease, as the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI topped out at 3.7%, the CDC reported. The national baseline is 2.1%.

For the week ending March 19, three states – Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, compared with seven the week before. Other states in the “high” range for the week were North Carolina at level 9 and Alabama, New York, and Virginia at level 8, according to data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 18.2 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-2016 flu season.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the most recent week, one of which occurred during the week ending March 5. That brings the total to 30 reported for the 2015-2016 season. For the three previous flu seasons, the pediatric death totals were 148 (2014-2015), 111 (2013-2014), and 171 (2012-2013), according to the CDC report.

The 2015-2016 U.S. flu season may have reached its peak. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) dropped to 3.2% for the week ending March 19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The drop came after 9 consecutive weeks without a decrease, as the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI topped out at 3.7%, the CDC reported. The national baseline is 2.1%.

For the week ending March 19, three states – Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, compared with seven the week before. Other states in the “high” range for the week were North Carolina at level 9 and Alabama, New York, and Virginia at level 8, according to data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 18.2 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-2016 flu season.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the most recent week, one of which occurred during the week ending March 5. That brings the total to 30 reported for the 2015-2016 season. For the three previous flu seasons, the pediatric death totals were 148 (2014-2015), 111 (2013-2014), and 171 (2012-2013), according to the CDC report.

The 2015-2016 U.S. flu season may have reached its peak. The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) dropped to 3.2% for the week ending March 19, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The drop came after 9 consecutive weeks without a decrease, as the proportion of outpatient visits for ILI topped out at 3.7%, the CDC reported. The national baseline is 2.1%.

For the week ending March 19, three states – Kentucky, New Jersey, and New Mexico – were at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of ILI activity, compared with seven the week before. Other states in the “high” range for the week were North Carolina at level 9 and Alabama, New York, and Virginia at level 8, according to data from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 18.2 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-2016 flu season.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the most recent week, one of which occurred during the week ending March 5. That brings the total to 30 reported for the 2015-2016 season. For the three previous flu seasons, the pediatric death totals were 148 (2014-2015), 111 (2013-2014), and 171 (2012-2013), according to the CDC report.

Studies underscore limits of Tdap vaccine

Replacing the first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine with its whole-cell predecessor could cut the rate of whooping cough by about 95% – including in neonates at greatest risk of severe outcomes, researchers reported March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Their model also predicted 95% fewer lost quality-adjusted life-years under the combined (whole-cell and acellular) vaccination strategy – even after accounting for vaccine-related adverse events, said Dr. Benjamin Althouse of the Santa Fe Institute and New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, and his associates. “Although new pertussis vaccines combining the safety of acellular pertussis and the efficacy of whole-cell pertussis are in early development, [they are] still a number of years away from regulatory approval,” they wrote. “In the interim, switching to the combined strategy is an effective option for reducing the disease and mortality burdens of Bordetella pertussis.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends five doses of acellular pertussis vaccine between 2 months and 4 to 6 years old. Infants born in the 1990s during the switch from the whole-cell vaccine to the safer acellular vaccine often received an initial whole-cell dose, followed by acellular doses. These “primed” children had less than half the rate of whooping cough than children who received only the acellular vaccine, multiple studies later showed. Since then, U.S. pertussis rates have surged, with more than 48,000 cases reported in 2012. Waning immunity is one factor, but the acellular vaccine also failed to prevent secondary B. pertussis transmission in a study of nonhuman primates, Dr. Althouse and his associates noted (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0047).

They compared the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the acellular vaccination schedule with a schedule in which the first dose was whole-cell vaccine and the next four doses were acellular vaccine. In a model fitted to pertussis data from 2012, incidence was about 95% lower (95% confidence interval, 91%-98%) with the combined strategy, and infection rates in neonates fell by 96% (95% CI, 92%-98%). Even after accounting for adverse events, loss of quality-adjusted life-years also fell by about 95%, and healthcare costs dropped by 94%, saving more than $142 million per year.

The acellular pertussis vaccine was licensed as a booster for adolescents and adults in 2005. Over the next several years, pertussis rates dropped faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among other age groups (Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:344-9). But that encouraging trend “abruptly reversed” in 2010, “corresponding directly to the aging of acellular pertussis-vaccinated cohorts” who were primed with the acellular vaccine, said the authors of a follow-up study also published March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4875).

For this study, Tami Skoff and Stacey Martin of the CDC analyzed all pertussis cases reported in the United States between 1990 and 2014. Between 1990 and 2003, rates rose from 1.7 to 4.0 cases per 100,000 individuals, and pertussis epidemics dominated later years, the researchers said. The acellular vaccine helped reverse infection rates among adolescents immediately after its introduction, but after 2010, infection rates rose faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among all other age groups combined (slope, 0.5727; P less than .001). By 2014, adolescents had the highest infection rates of any group except infants under 1 year old, who had the highest pertussis incidence throughout the study period.

The findings “support the accumulating literature on waning acellular vaccine-induced immunity,” said the researchers. Because immunity with the acellular vaccine wanes after about 2 years, additional vaccinations are unlikely to have much impact, they noted. They also emphasized the importance of timely vaccination and vaccinating pregnant women to protect infants.

Dr. Althouse and his associates were funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Omidyar Group, and the Santa Fe Institute. Skoff and Martin reported no external funding sources. None of the investigators had disclosures.

Although it has been clear for several years that immunity following acellular pertussis vaccines wanes, the study [by Skoff and Martin] documents the effect at a population level. The bad news is that Tdap vaccination mostly [benefited] adolescents who, when they were infants, received at least some doses of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine when it was still in use. Now, as those cohorts are replaced by younger ones who only received acellular vaccines, pertussis is making a comeback. Several studies have shown that the immune responses to the 2 types of vaccine are quite different and unfortunately the response to acellular vaccines is inferior. We will continue to see a lot of pertussis until new vaccines are developed.

What can we do to protect older children and adults from pertussis while we wait for new vaccines? DeAngelis et al. suggest that we could achieve a dramatic reduction in pertussis cases by giving an initial priming dose of whole-cell vaccine in infancy, followed by the remainder of the vaccine series with acellular vaccine. These findings must be considered preliminary because the authors made a number of assumptions for which we have insufficient data.

Pertussis is back. While we consider alternative vaccination strategies and develop new vaccines, we can at least do a better job of preventing pertussis-related deaths in infants by immunizing women during each pregnancy. We know that is safe and effective and is being increasingly accepted by pregnant women. As for other strategies, which might include reintroducing whole-cell vaccines, we need to be sure parents are going to go along.

Dr. Mark H. Sawyer is at the Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He had no disclosures. These comments are based on his editorial (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0157).

Although it has been clear for several years that immunity following acellular pertussis vaccines wanes, the study [by Skoff and Martin] documents the effect at a population level. The bad news is that Tdap vaccination mostly [benefited] adolescents who, when they were infants, received at least some doses of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine when it was still in use. Now, as those cohorts are replaced by younger ones who only received acellular vaccines, pertussis is making a comeback. Several studies have shown that the immune responses to the 2 types of vaccine are quite different and unfortunately the response to acellular vaccines is inferior. We will continue to see a lot of pertussis until new vaccines are developed.

What can we do to protect older children and adults from pertussis while we wait for new vaccines? DeAngelis et al. suggest that we could achieve a dramatic reduction in pertussis cases by giving an initial priming dose of whole-cell vaccine in infancy, followed by the remainder of the vaccine series with acellular vaccine. These findings must be considered preliminary because the authors made a number of assumptions for which we have insufficient data.

Pertussis is back. While we consider alternative vaccination strategies and develop new vaccines, we can at least do a better job of preventing pertussis-related deaths in infants by immunizing women during each pregnancy. We know that is safe and effective and is being increasingly accepted by pregnant women. As for other strategies, which might include reintroducing whole-cell vaccines, we need to be sure parents are going to go along.

Dr. Mark H. Sawyer is at the Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He had no disclosures. These comments are based on his editorial (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0157).

Although it has been clear for several years that immunity following acellular pertussis vaccines wanes, the study [by Skoff and Martin] documents the effect at a population level. The bad news is that Tdap vaccination mostly [benefited] adolescents who, when they were infants, received at least some doses of the whole-cell pertussis vaccine when it was still in use. Now, as those cohorts are replaced by younger ones who only received acellular vaccines, pertussis is making a comeback. Several studies have shown that the immune responses to the 2 types of vaccine are quite different and unfortunately the response to acellular vaccines is inferior. We will continue to see a lot of pertussis until new vaccines are developed.

What can we do to protect older children and adults from pertussis while we wait for new vaccines? DeAngelis et al. suggest that we could achieve a dramatic reduction in pertussis cases by giving an initial priming dose of whole-cell vaccine in infancy, followed by the remainder of the vaccine series with acellular vaccine. These findings must be considered preliminary because the authors made a number of assumptions for which we have insufficient data.

Pertussis is back. While we consider alternative vaccination strategies and develop new vaccines, we can at least do a better job of preventing pertussis-related deaths in infants by immunizing women during each pregnancy. We know that is safe and effective and is being increasingly accepted by pregnant women. As for other strategies, which might include reintroducing whole-cell vaccines, we need to be sure parents are going to go along.

Dr. Mark H. Sawyer is at the Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He had no disclosures. These comments are based on his editorial (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0157).

Replacing the first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine with its whole-cell predecessor could cut the rate of whooping cough by about 95% – including in neonates at greatest risk of severe outcomes, researchers reported March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Their model also predicted 95% fewer lost quality-adjusted life-years under the combined (whole-cell and acellular) vaccination strategy – even after accounting for vaccine-related adverse events, said Dr. Benjamin Althouse of the Santa Fe Institute and New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, and his associates. “Although new pertussis vaccines combining the safety of acellular pertussis and the efficacy of whole-cell pertussis are in early development, [they are] still a number of years away from regulatory approval,” they wrote. “In the interim, switching to the combined strategy is an effective option for reducing the disease and mortality burdens of Bordetella pertussis.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends five doses of acellular pertussis vaccine between 2 months and 4 to 6 years old. Infants born in the 1990s during the switch from the whole-cell vaccine to the safer acellular vaccine often received an initial whole-cell dose, followed by acellular doses. These “primed” children had less than half the rate of whooping cough than children who received only the acellular vaccine, multiple studies later showed. Since then, U.S. pertussis rates have surged, with more than 48,000 cases reported in 2012. Waning immunity is one factor, but the acellular vaccine also failed to prevent secondary B. pertussis transmission in a study of nonhuman primates, Dr. Althouse and his associates noted (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0047).

They compared the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the acellular vaccination schedule with a schedule in which the first dose was whole-cell vaccine and the next four doses were acellular vaccine. In a model fitted to pertussis data from 2012, incidence was about 95% lower (95% confidence interval, 91%-98%) with the combined strategy, and infection rates in neonates fell by 96% (95% CI, 92%-98%). Even after accounting for adverse events, loss of quality-adjusted life-years also fell by about 95%, and healthcare costs dropped by 94%, saving more than $142 million per year.

The acellular pertussis vaccine was licensed as a booster for adolescents and adults in 2005. Over the next several years, pertussis rates dropped faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among other age groups (Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:344-9). But that encouraging trend “abruptly reversed” in 2010, “corresponding directly to the aging of acellular pertussis-vaccinated cohorts” who were primed with the acellular vaccine, said the authors of a follow-up study also published March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4875).

For this study, Tami Skoff and Stacey Martin of the CDC analyzed all pertussis cases reported in the United States between 1990 and 2014. Between 1990 and 2003, rates rose from 1.7 to 4.0 cases per 100,000 individuals, and pertussis epidemics dominated later years, the researchers said. The acellular vaccine helped reverse infection rates among adolescents immediately after its introduction, but after 2010, infection rates rose faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among all other age groups combined (slope, 0.5727; P less than .001). By 2014, adolescents had the highest infection rates of any group except infants under 1 year old, who had the highest pertussis incidence throughout the study period.

The findings “support the accumulating literature on waning acellular vaccine-induced immunity,” said the researchers. Because immunity with the acellular vaccine wanes after about 2 years, additional vaccinations are unlikely to have much impact, they noted. They also emphasized the importance of timely vaccination and vaccinating pregnant women to protect infants.

Dr. Althouse and his associates were funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Omidyar Group, and the Santa Fe Institute. Skoff and Martin reported no external funding sources. None of the investigators had disclosures.

Replacing the first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine with its whole-cell predecessor could cut the rate of whooping cough by about 95% – including in neonates at greatest risk of severe outcomes, researchers reported March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Their model also predicted 95% fewer lost quality-adjusted life-years under the combined (whole-cell and acellular) vaccination strategy – even after accounting for vaccine-related adverse events, said Dr. Benjamin Althouse of the Santa Fe Institute and New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, and his associates. “Although new pertussis vaccines combining the safety of acellular pertussis and the efficacy of whole-cell pertussis are in early development, [they are] still a number of years away from regulatory approval,” they wrote. “In the interim, switching to the combined strategy is an effective option for reducing the disease and mortality burdens of Bordetella pertussis.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommends five doses of acellular pertussis vaccine between 2 months and 4 to 6 years old. Infants born in the 1990s during the switch from the whole-cell vaccine to the safer acellular vaccine often received an initial whole-cell dose, followed by acellular doses. These “primed” children had less than half the rate of whooping cough than children who received only the acellular vaccine, multiple studies later showed. Since then, U.S. pertussis rates have surged, with more than 48,000 cases reported in 2012. Waning immunity is one factor, but the acellular vaccine also failed to prevent secondary B. pertussis transmission in a study of nonhuman primates, Dr. Althouse and his associates noted (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.0047).

They compared the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the acellular vaccination schedule with a schedule in which the first dose was whole-cell vaccine and the next four doses were acellular vaccine. In a model fitted to pertussis data from 2012, incidence was about 95% lower (95% confidence interval, 91%-98%) with the combined strategy, and infection rates in neonates fell by 96% (95% CI, 92%-98%). Even after accounting for adverse events, loss of quality-adjusted life-years also fell by about 95%, and healthcare costs dropped by 94%, saving more than $142 million per year.

The acellular pertussis vaccine was licensed as a booster for adolescents and adults in 2005. Over the next several years, pertussis rates dropped faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among other age groups (Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:344-9). But that encouraging trend “abruptly reversed” in 2010, “corresponding directly to the aging of acellular pertussis-vaccinated cohorts” who were primed with the acellular vaccine, said the authors of a follow-up study also published March 28 in JAMA Pediatrics (JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4875).

For this study, Tami Skoff and Stacey Martin of the CDC analyzed all pertussis cases reported in the United States between 1990 and 2014. Between 1990 and 2003, rates rose from 1.7 to 4.0 cases per 100,000 individuals, and pertussis epidemics dominated later years, the researchers said. The acellular vaccine helped reverse infection rates among adolescents immediately after its introduction, but after 2010, infection rates rose faster among 11- to 18-year-olds than among all other age groups combined (slope, 0.5727; P less than .001). By 2014, adolescents had the highest infection rates of any group except infants under 1 year old, who had the highest pertussis incidence throughout the study period.

The findings “support the accumulating literature on waning acellular vaccine-induced immunity,” said the researchers. Because immunity with the acellular vaccine wanes after about 2 years, additional vaccinations are unlikely to have much impact, they noted. They also emphasized the importance of timely vaccination and vaccinating pregnant women to protect infants.

Dr. Althouse and his associates were funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Omidyar Group, and the Santa Fe Institute. Skoff and Martin reported no external funding sources. None of the investigators had disclosures.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Two studies underscored the problem of waning immunity with the acellular pertussis vaccine.

Major finding: Replacing the first dose of acellular pertussis vaccine with its whole-cell predecessor cut incidence by about 95% in a mathematical model. After 2010, pertussis infection rates rose faster among 11 to 18-year-olds than among all other age groups combined (slope, 0.5727; P less than .001).

Data source: Two separate analyses of national pertussis incidence data.

Disclosures: Dr. Althouse and his associates were funded by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the Omidyar Group, and the Santa Fe Institute. Ms. Skoff and Ms. Martin reported no external funding sources. None of the investigators had disclosures.

FDA approves reslizumab as add-on drug for adults with severe asthma

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of reslizumab with other asthma medication for maintenance treatment in adult patients with a history of severe asthma attacks.

The drug is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG4/K isotype, and reduces blood levels of eosinophils. The intravenously infused biologic must be administered in a clinical setting by a health professional who is prepared to manage anaphylaxis, according to a written statement from the FDA.

In December, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drug Advisory Committee had recommended approval of the drug for use in 18- to 75-year-olds with inadequately controlled eosinophilic asthma, based on the results of phase III double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trials in which the drug was administered every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. As compared with patients who received a placebo, patients who received the drug had fewer asthma attacks, had a later-onset first attack, and experienced a significant improvement in lung function based on measures of forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

The most common side effects of taking reslizumab experienced by patients in clinical trials included anaphylaxis, cancer, and muscle pain.

Teva Pharmaceuticals is marketing the drug as Cinqair.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of reslizumab with other asthma medication for maintenance treatment in adult patients with a history of severe asthma attacks.

The drug is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG4/K isotype, and reduces blood levels of eosinophils. The intravenously infused biologic must be administered in a clinical setting by a health professional who is prepared to manage anaphylaxis, according to a written statement from the FDA.

In December, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drug Advisory Committee had recommended approval of the drug for use in 18- to 75-year-olds with inadequately controlled eosinophilic asthma, based on the results of phase III double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trials in which the drug was administered every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. As compared with patients who received a placebo, patients who received the drug had fewer asthma attacks, had a later-onset first attack, and experienced a significant improvement in lung function based on measures of forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

The most common side effects of taking reslizumab experienced by patients in clinical trials included anaphylaxis, cancer, and muscle pain.

Teva Pharmaceuticals is marketing the drug as Cinqair.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the use of reslizumab with other asthma medication for maintenance treatment in adult patients with a history of severe asthma attacks.

The drug is a humanized monoclonal antibody of the IgG4/K isotype, and reduces blood levels of eosinophils. The intravenously infused biologic must be administered in a clinical setting by a health professional who is prepared to manage anaphylaxis, according to a written statement from the FDA.

In December, the FDA’s Pulmonary-Allergy Drug Advisory Committee had recommended approval of the drug for use in 18- to 75-year-olds with inadequately controlled eosinophilic asthma, based on the results of phase III double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled trials in which the drug was administered every 4 weeks as an add-on asthma treatment. As compared with patients who received a placebo, patients who received the drug had fewer asthma attacks, had a later-onset first attack, and experienced a significant improvement in lung function based on measures of forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

The most common side effects of taking reslizumab experienced by patients in clinical trials included anaphylaxis, cancer, and muscle pain.

Teva Pharmaceuticals is marketing the drug as Cinqair.

Does sharing genetic risk change behavior?

In the era of individualized (or precision) medicine, we are presented with a unique opportunity to peer into the genetic “maps” of our patients. Through this window, we can envision the self-evident present or predict a possible future.

For the front-line provider, knowing that we could someday have a large amount of these data to deal with can be overwhelming. We may be loath to think that, amongst all the other daily battles we wage with current disease states, we may now need to understand and explain risk for future disease states.

But would we be more likely to use these data if we thought that they would change patient behavior? Maybe.

So does it?

Gareth Hollands, Ph.D., of the University of Cambridge, England, and his colleagues conducted a brilliantly timed and welcome systematic review of the literature assessing the impact of communicating DNA-based disease risk estimates on risk-reducing health behaviors and motivation to engage in such behaviors (BMJ. 2016 Mar 15;352:i1102).