User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Powered by CHEST Physician, Clinician Reviews, MDedge Family Medicine, Internal Medicine News, and The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management.

Asthma, eczema in children unrelated to allergic sensitization

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

Atopy was not related to development of eczema or asthma in children under age 13 years, according to Ann-Marie Malby Schoos, Ph.D., and her associates at the University of Copenhagen.

Allergic sensitization increased with age in the 399 children tested, rising from 12% at 6 months to 54% at 13 years. The incidence of asthma was highest at age 4 years at 16%, but decreased afterward, falling to 12% at 13 years. The incidence of eczema peaked at 39% in children aged 1.5 years old, but decreased steadily to only 12% in 13-year-olds.

Asthma and allergic sensitization were related only in late childhood, with an odds ratio of 4.49 in 13-year-olds. This pattern was seen throughout allergic sensitization subgroups. There were strong associations between eczema and allergic sensitization at 6 months (OR, 6.02), 1.5 years (OR, 2.06), and 6 years (OR, 2.77), but no association at 13 years. The proportion of children with allergic sensitization who did not have asthma or eczema also increased with age.

“The tradition of using atopy as a particular endotype of asthma and eczema seems unfounded because it depends on the method of testing for sensitization, type of allergens, and age of the patient. This questions the relevance of the terms atopic asthma and atopic eczema as true endotypes,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.004).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Pertussis vaccines effective against pertactin-deficient strains

Current pertussis vaccines were as effective against the rapidly evolving pertactin-deficient strains of the organism as they have been against other strains, according to a report published online April 13 in Pediatrics.

The proportion of pertussis strains lacking pertactin increased markedly in the United States, from 14% in 2010 to 85% in 2012. Pertactin, an autotransporter thought to be “involved in bacterial adhesion to the respiratory tract and resistance to neutrophil-induced bacterial clearance,” is a component of acellular pertussis vaccines. Some have speculated that pertactin deficiency evolved to give the bacteria an advantage in response to vaccine-related selection pressure, and that this evolution has contributed to the recent resurgence of pertussis disease, said Lucy Breakwell, Ph.D., of the epidemic intelligence service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

To assess vaccine efficacy in the setting of pertactin deficiency, the investigators studied 820 cases and 2,369 matched control subjects treated in Vermont during a 3-year period encompassing a recent pertussis outbreak there. The study included children aged 4-10 years given the five-dose DTaP childhood series and adolescents aged 11-19 years given the adolescent Tdap dose. Specimens from these cases had been cultured routinely by the state department of health laboratory, and more than 90% of the available isolates were found to be pertactin deficient.

The overall vaccine efficacy of the DTap series was 84%, and of the Tdap booster, 70%. “Remarkably,” these rates are comparable to the 89% efficacy of DTap reported in a 2010 California outbreak and the 64% efficacy of Tdap reported in a 2012 Washington state outbreak, the investigators said. “Our findings suggest that both acellular pertussis vaccines remain protective against pertussis disease in the setting of high pertactin deficiency,” and therefore remain the best method for protecting against severe disease, Dr. Breakwell and her associates said (Pediatr. 2016 April 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3973).

Nevertheless, further study is warranted “to better understand the implications of pertactin deficiency on pertussis pathogenesis and host immunologic response, which could provide insight into the development of novel pertussis vaccines,” they wrote.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Breakwell and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Immunity to pertussis from either natural infection or vaccination, is not lifelong. Two acellular pertussis vaccines are in widespread use in the United States, and they differ in the number and amounts of purified proteins and method of being chemically inactivated. A vaccine made by GlaxoSmithKline includes three proteins: pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), and pertactin (PRN). A vaccine made by Sanofi Pasteur includes the same three proteins (PT, FHA, and PRN) plus two types of fimbriae (FIM), for a total of five ingredients. PT causes virtually all the symptoms of pertussis disease. The other proteins included in the two acellular vaccines are principally there to prevent the Bordetella pertussis bacteria from attaching to the nasopharynx and lung because prevention of attachment is a prevention of pathogenesis.

Although both acellular pertussis vaccines provide good protection, many reports support that acellular pertussis vaccines have shown waning immunity. One hypothesis among experts is that waning immunity might be related to changes in the protein structure of one or more of the targets for acellular vaccines. The protein that has been shown to have changed since introduction of acellular vaccines is PRN.

In the current study from Vermont, we learn that acellular pertussis vaccine efficacy remained high in that state despite the presence of over 90% of the B. pertussis strains lacking a PRN protein on the bacteria surface that would serve as an antibody target following vaccination. In other words, the lack of PRN as a vaccine target did not reduce vaccine efficacy nor did it impact the waning immunity following vaccination.

The result is reassuring and expected. All bacteria that seek to attach themselves to our respiratory tract in the nose or lungs or both have many different proteins to accomplish that attachment task. The redundancy of those proteins fits easily in a biologic necessity framework because pathogenesis cannot begin for any of the respiratory pathogenic bacteria unless they can attach themselves to the host in the nose or lungs or both. The addition of FHA as well as PRN in the GlaxoSmithKline vaccine and FHA plus two types of FIM antigen as ingredients in the Sanofi Pasteur vaccine was to raise antibody to multiple “adhesion” proteins. That way if “escape mutants” occurred, as we are now observing for PRN-deficient strains, the vaccines would still work. The study from Vermont tells us that they still do work.

Michael E. Pichichero, M.D., a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero commented in an interview. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Immunity to pertussis from either natural infection or vaccination, is not lifelong. Two acellular pertussis vaccines are in widespread use in the United States, and they differ in the number and amounts of purified proteins and method of being chemically inactivated. A vaccine made by GlaxoSmithKline includes three proteins: pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), and pertactin (PRN). A vaccine made by Sanofi Pasteur includes the same three proteins (PT, FHA, and PRN) plus two types of fimbriae (FIM), for a total of five ingredients. PT causes virtually all the symptoms of pertussis disease. The other proteins included in the two acellular vaccines are principally there to prevent the Bordetella pertussis bacteria from attaching to the nasopharynx and lung because prevention of attachment is a prevention of pathogenesis.

Although both acellular pertussis vaccines provide good protection, many reports support that acellular pertussis vaccines have shown waning immunity. One hypothesis among experts is that waning immunity might be related to changes in the protein structure of one or more of the targets for acellular vaccines. The protein that has been shown to have changed since introduction of acellular vaccines is PRN.

In the current study from Vermont, we learn that acellular pertussis vaccine efficacy remained high in that state despite the presence of over 90% of the B. pertussis strains lacking a PRN protein on the bacteria surface that would serve as an antibody target following vaccination. In other words, the lack of PRN as a vaccine target did not reduce vaccine efficacy nor did it impact the waning immunity following vaccination.

The result is reassuring and expected. All bacteria that seek to attach themselves to our respiratory tract in the nose or lungs or both have many different proteins to accomplish that attachment task. The redundancy of those proteins fits easily in a biologic necessity framework because pathogenesis cannot begin for any of the respiratory pathogenic bacteria unless they can attach themselves to the host in the nose or lungs or both. The addition of FHA as well as PRN in the GlaxoSmithKline vaccine and FHA plus two types of FIM antigen as ingredients in the Sanofi Pasteur vaccine was to raise antibody to multiple “adhesion” proteins. That way if “escape mutants” occurred, as we are now observing for PRN-deficient strains, the vaccines would still work. The study from Vermont tells us that they still do work.

Michael E. Pichichero, M.D., a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero commented in an interview. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Immunity to pertussis from either natural infection or vaccination, is not lifelong. Two acellular pertussis vaccines are in widespread use in the United States, and they differ in the number and amounts of purified proteins and method of being chemically inactivated. A vaccine made by GlaxoSmithKline includes three proteins: pertussis toxin (PT), filamentous hemagglutinin (FHA), and pertactin (PRN). A vaccine made by Sanofi Pasteur includes the same three proteins (PT, FHA, and PRN) plus two types of fimbriae (FIM), for a total of five ingredients. PT causes virtually all the symptoms of pertussis disease. The other proteins included in the two acellular vaccines are principally there to prevent the Bordetella pertussis bacteria from attaching to the nasopharynx and lung because prevention of attachment is a prevention of pathogenesis.

Although both acellular pertussis vaccines provide good protection, many reports support that acellular pertussis vaccines have shown waning immunity. One hypothesis among experts is that waning immunity might be related to changes in the protein structure of one or more of the targets for acellular vaccines. The protein that has been shown to have changed since introduction of acellular vaccines is PRN.

In the current study from Vermont, we learn that acellular pertussis vaccine efficacy remained high in that state despite the presence of over 90% of the B. pertussis strains lacking a PRN protein on the bacteria surface that would serve as an antibody target following vaccination. In other words, the lack of PRN as a vaccine target did not reduce vaccine efficacy nor did it impact the waning immunity following vaccination.

The result is reassuring and expected. All bacteria that seek to attach themselves to our respiratory tract in the nose or lungs or both have many different proteins to accomplish that attachment task. The redundancy of those proteins fits easily in a biologic necessity framework because pathogenesis cannot begin for any of the respiratory pathogenic bacteria unless they can attach themselves to the host in the nose or lungs or both. The addition of FHA as well as PRN in the GlaxoSmithKline vaccine and FHA plus two types of FIM antigen as ingredients in the Sanofi Pasteur vaccine was to raise antibody to multiple “adhesion” proteins. That way if “escape mutants” occurred, as we are now observing for PRN-deficient strains, the vaccines would still work. The study from Vermont tells us that they still do work.

Michael E. Pichichero, M.D., a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero commented in an interview. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Current pertussis vaccines were as effective against the rapidly evolving pertactin-deficient strains of the organism as they have been against other strains, according to a report published online April 13 in Pediatrics.

The proportion of pertussis strains lacking pertactin increased markedly in the United States, from 14% in 2010 to 85% in 2012. Pertactin, an autotransporter thought to be “involved in bacterial adhesion to the respiratory tract and resistance to neutrophil-induced bacterial clearance,” is a component of acellular pertussis vaccines. Some have speculated that pertactin deficiency evolved to give the bacteria an advantage in response to vaccine-related selection pressure, and that this evolution has contributed to the recent resurgence of pertussis disease, said Lucy Breakwell, Ph.D., of the epidemic intelligence service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

To assess vaccine efficacy in the setting of pertactin deficiency, the investigators studied 820 cases and 2,369 matched control subjects treated in Vermont during a 3-year period encompassing a recent pertussis outbreak there. The study included children aged 4-10 years given the five-dose DTaP childhood series and adolescents aged 11-19 years given the adolescent Tdap dose. Specimens from these cases had been cultured routinely by the state department of health laboratory, and more than 90% of the available isolates were found to be pertactin deficient.

The overall vaccine efficacy of the DTap series was 84%, and of the Tdap booster, 70%. “Remarkably,” these rates are comparable to the 89% efficacy of DTap reported in a 2010 California outbreak and the 64% efficacy of Tdap reported in a 2012 Washington state outbreak, the investigators said. “Our findings suggest that both acellular pertussis vaccines remain protective against pertussis disease in the setting of high pertactin deficiency,” and therefore remain the best method for protecting against severe disease, Dr. Breakwell and her associates said (Pediatr. 2016 April 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3973).

Nevertheless, further study is warranted “to better understand the implications of pertactin deficiency on pertussis pathogenesis and host immunologic response, which could provide insight into the development of novel pertussis vaccines,” they wrote.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Breakwell and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Current pertussis vaccines were as effective against the rapidly evolving pertactin-deficient strains of the organism as they have been against other strains, according to a report published online April 13 in Pediatrics.

The proportion of pertussis strains lacking pertactin increased markedly in the United States, from 14% in 2010 to 85% in 2012. Pertactin, an autotransporter thought to be “involved in bacterial adhesion to the respiratory tract and resistance to neutrophil-induced bacterial clearance,” is a component of acellular pertussis vaccines. Some have speculated that pertactin deficiency evolved to give the bacteria an advantage in response to vaccine-related selection pressure, and that this evolution has contributed to the recent resurgence of pertussis disease, said Lucy Breakwell, Ph.D., of the epidemic intelligence service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

To assess vaccine efficacy in the setting of pertactin deficiency, the investigators studied 820 cases and 2,369 matched control subjects treated in Vermont during a 3-year period encompassing a recent pertussis outbreak there. The study included children aged 4-10 years given the five-dose DTaP childhood series and adolescents aged 11-19 years given the adolescent Tdap dose. Specimens from these cases had been cultured routinely by the state department of health laboratory, and more than 90% of the available isolates were found to be pertactin deficient.

The overall vaccine efficacy of the DTap series was 84%, and of the Tdap booster, 70%. “Remarkably,” these rates are comparable to the 89% efficacy of DTap reported in a 2010 California outbreak and the 64% efficacy of Tdap reported in a 2012 Washington state outbreak, the investigators said. “Our findings suggest that both acellular pertussis vaccines remain protective against pertussis disease in the setting of high pertactin deficiency,” and therefore remain the best method for protecting against severe disease, Dr. Breakwell and her associates said (Pediatr. 2016 April 12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3973).

Nevertheless, further study is warranted “to better understand the implications of pertactin deficiency on pertussis pathogenesis and host immunologic response, which could provide insight into the development of novel pertussis vaccines,” they wrote.

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Breakwell and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Current pertussis vaccines remain effective against rapidly evolving pertactin-deficient strains of the organism.

Major finding: The overall vaccine efficacy of the DTap series was 84%, and of the Tdap booster, 70%.

Data source: A case-control study assessing vaccine efficacy in 820 patients and 2,369 controls involved in the recent Vermont outbreak of pertussis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dr. Breakwell and her associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Immunization need not be delayed in most preterm infants with BPD

Despite concerns that preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) are more likely to experience respiratory decompensation after immunization than those without BPD, no difference in the incidence of respiratory decompensation within 72 hours after immunization was found between these groups in a cohort study at a tertiary care facility, according to a report published April 11 in Pediatrics.

These results demonstrate the safety of immunizing preterm infants with BPD, and that the findings should negate delays in immunizations in these patients based on safety concerns described in previous studies, Dr. Edwin Clark Montague of Emory University, Atlanta, and his colleagues assert.

In a retrospective observational study, Dr. Clark and his associates assessed a cohort of infants admitted to the NICU at a level 4, nonbirthing referral hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, who received any immunizations while hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2008, and Aug. 1, 2014. Inclusion criteria were birth at less than 32 weeks’ estimated gestational age and the availability of data for 72 hours before and 72 hours after immunization. The incidence of respiratory decompensation and cardiorespiratory events (apnea, bradycardia, desaturations) after immunization was compared between infants with and without BPD after immunization (Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4225).

Of the 403 patients assessed, 240 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 170 were identified as having BPD and were compared with the 70 patients without BPD. The study results revealed no statistically significant difference in respiratory decompensation between patients with and without BPD. In addition, both groups showed an increased incidence of cardiorespiratory events, but there was no statistically significant difference between those with and without BPD.

In addition to BPD, the authors assessed risk factors that may predispose preterm infants to respiratory decompensation after immunization, such as a history of necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation, grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage, or periventricular leukomalacia. Results from these analyses indicated that severe intraventricular hemorrhage was a predictor of respiratory decompensation after immunization, and that a positive blood culture within 72 hours of immunization was predictive as well. The authors said that decompensation was likely secondary to the underlying infection in those with positive blood cultures, but that additional research would be required to better understand this finding.

The authors reported no external funding sources and no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite concerns that preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) are more likely to experience respiratory decompensation after immunization than those without BPD, no difference in the incidence of respiratory decompensation within 72 hours after immunization was found between these groups in a cohort study at a tertiary care facility, according to a report published April 11 in Pediatrics.

These results demonstrate the safety of immunizing preterm infants with BPD, and that the findings should negate delays in immunizations in these patients based on safety concerns described in previous studies, Dr. Edwin Clark Montague of Emory University, Atlanta, and his colleagues assert.

In a retrospective observational study, Dr. Clark and his associates assessed a cohort of infants admitted to the NICU at a level 4, nonbirthing referral hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, who received any immunizations while hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2008, and Aug. 1, 2014. Inclusion criteria were birth at less than 32 weeks’ estimated gestational age and the availability of data for 72 hours before and 72 hours after immunization. The incidence of respiratory decompensation and cardiorespiratory events (apnea, bradycardia, desaturations) after immunization was compared between infants with and without BPD after immunization (Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4225).

Of the 403 patients assessed, 240 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 170 were identified as having BPD and were compared with the 70 patients without BPD. The study results revealed no statistically significant difference in respiratory decompensation between patients with and without BPD. In addition, both groups showed an increased incidence of cardiorespiratory events, but there was no statistically significant difference between those with and without BPD.

In addition to BPD, the authors assessed risk factors that may predispose preterm infants to respiratory decompensation after immunization, such as a history of necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation, grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage, or periventricular leukomalacia. Results from these analyses indicated that severe intraventricular hemorrhage was a predictor of respiratory decompensation after immunization, and that a positive blood culture within 72 hours of immunization was predictive as well. The authors said that decompensation was likely secondary to the underlying infection in those with positive blood cultures, but that additional research would be required to better understand this finding.

The authors reported no external funding sources and no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Despite concerns that preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) are more likely to experience respiratory decompensation after immunization than those without BPD, no difference in the incidence of respiratory decompensation within 72 hours after immunization was found between these groups in a cohort study at a tertiary care facility, according to a report published April 11 in Pediatrics.

These results demonstrate the safety of immunizing preterm infants with BPD, and that the findings should negate delays in immunizations in these patients based on safety concerns described in previous studies, Dr. Edwin Clark Montague of Emory University, Atlanta, and his colleagues assert.

In a retrospective observational study, Dr. Clark and his associates assessed a cohort of infants admitted to the NICU at a level 4, nonbirthing referral hospital, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, who received any immunizations while hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2008, and Aug. 1, 2014. Inclusion criteria were birth at less than 32 weeks’ estimated gestational age and the availability of data for 72 hours before and 72 hours after immunization. The incidence of respiratory decompensation and cardiorespiratory events (apnea, bradycardia, desaturations) after immunization was compared between infants with and without BPD after immunization (Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4225).

Of the 403 patients assessed, 240 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 170 were identified as having BPD and were compared with the 70 patients without BPD. The study results revealed no statistically significant difference in respiratory decompensation between patients with and without BPD. In addition, both groups showed an increased incidence of cardiorespiratory events, but there was no statistically significant difference between those with and without BPD.

In addition to BPD, the authors assessed risk factors that may predispose preterm infants to respiratory decompensation after immunization, such as a history of necrotizing enterocolitis or spontaneous intestinal perforation, grade III or IV intraventricular hemorrhage, or periventricular leukomalacia. Results from these analyses indicated that severe intraventricular hemorrhage was a predictor of respiratory decompensation after immunization, and that a positive blood culture within 72 hours of immunization was predictive as well. The authors said that decompensation was likely secondary to the underlying infection in those with positive blood cultures, but that additional research would be required to better understand this finding.

The authors reported no external funding sources and no financial relationships relevant to this article.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Respiratory decompensation after immunization of preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia is rare and should not be a cause for delayed immunization.

Major finding: No statistically significant differences regarding respiratory decompensation within 72 hours of immunization or its individual components were found between preterm infants with or without bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Data source: A retrospective observational study of a cohort of premature infants less than 32 weeks’ gestational age admitted to a tertiary level 4 NICU, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, immunized as inpatients between January 1, 2008, and August 1, 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no external funding sources and no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Stick with wheat flour for baked egg and milk challenges

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Children who pass oral food challenges to baked egg and milk with wheat flour are at risk for reacting to baked goods made with nonwheat flours, according to a review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges at National Jewish Health in Denver.

The children were already known to be sensitive to egg and milk, and some were being challenged to see if exposure therapy was helping. Unbeknown to the pediatric food allergy team, a kitchen worker at National Jewish had started making muffins with rice flour, thinking it would be safer.

During the month of muffins with rice flour, the failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14) (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.579).

Adjusting for age, gender, and atopic dermatitis, children were more than five times more likely to fail baked eggs without wheat (odds ratio, 5.4; P = .002), and more than four times more likely to fail baked milk (OR, 4.06; P = .05).

Given that the phenomenon hasn’t been reported before, “This was very surprising to us,” said study investigator Dr. Bruce Lanser, director of the pediatric food allergy program at National Jewish. “You have to warn parents that if children pass a baked challenge with wheat, they have to continue to eat their baked milk and egg with wheat. Gluten-free products are not going to have the same effect.

“If somebody is avoiding wheat because it causes a bit of redness and itchiness, you have to clear that wheat allergy” before moving to baked egg and milk, Dr. Lanser added.

There’s also concern that “kids will go home after passing a wheat muffin challenge, eat something that’s gluten-free, and have a reaction,” he noted. Wheat-free baked goods might also not build tolerance as well, although that’s not clear from the study, Dr. Lanser said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

Wheat seems to have something unique that alters the allergic properties of egg and milk proteins to help children outgrow their sensitivities. “Rice doesn’t have the same effect,” he observed, and it’s not known if any other grains do. Dr. Lanser said he is interested in looking into rye, barley, oats, and other alternatives.

The mean age of the children in the study was 6 years, and most children had multiple food allergies. Sensitization was confirmed by skin tests and specific IgE.

Meanwhile, there’s a new rule in the National Jewish kitchen: Unless a child has true celiac disease, “always make [challenge] muffins with wheat,” Dr. Lanser said.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

AT 2016 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Children are more likely to react to nonwheat challenge muffins, and wheat substitutes might not work as well for oral immunotherapy.

Major finding: The failure rate for baked egg challenge muffins rose from 28% (33/120) to 58% (11/19) with rice flour. Failure to baked milk muffins rose from 14% (9/66) to 36% (5/14).

Data source: Single-center review of more than 200 pediatric food challenges.

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no disclosures.

Some infants predisposed to epidermal barrier breakdown, atopic dermatitis

Neonates with the highest transepidermal water loss at birth, likely mediated through an impaired epidermal barrier, show significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors, which may predispose them to the development of atopic dermatitis, according to a report published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

John Chittock of the University of Sheffield, England, and his colleagues assessed the biophysical, biologic, and functional properties of the developing neonatal stratum corneum (SC) from birth to 4 weeks of age in 115 healthy, full-term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation) neonates from the OBSERVE (Oil in Baby Skincare) randomized study birth cohort recruited at Saint Mary’s Hospital, Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, between September 2013 and June 2014.

For comparative purposes, an unrelated cohort of 20 adults with healthy skin was recruited from the local community between January and April 2015 (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14568).

The researchers found that the biophysical properties of the neonatal SC are transitional from birth. For example, overall transepidermal water loss (TEWL) increased significantly during the first 4 weeks of infant life. Compared with adult skin, the newborn infant SC was found to be drier and more alkaline. In addition, levels of superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity at birth did not differ between newborns and adults, while levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors (NMF) were significantly lower at birth than in adulthood.

The increased chymotrypsinlike protease activity and NMF at 4 weeks of age exceeded levels found in healthy adults, rather than reaching their mature state. Compared with adult skin, the skin of infants is functionally immature, with undeveloped mechanisms of desquamation and differentiation, the investigators noted.

Further analysis revealed a correlation between TEWL and both superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity and filaggrin-derived NMF at birth.

To explore that link, the researchers stratified the neonatal cohort according to TEWL percentile. The neonates in the 76th-100th percentile, the highest TEWL at birth, showed significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived NMF, compared with neonates in lower percentiles. Therefore, those neonates are at highest risk for developing atopic dermatitis, the study authors said.

The findings indicate a need for infant skin care regimens that protect and support normal barrier development from birth, the researchers noted. They also suggested that clinical strategies targeting the early mechanisms of barrier breakdown could act as preventive measures in neonates at increased risk of developing atopic dermatitis.

The research was funded jointly by the University of Sheffield and a doctoral research fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Neonates with the highest transepidermal water loss at birth, likely mediated through an impaired epidermal barrier, show significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors, which may predispose them to the development of atopic dermatitis, according to a report published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

John Chittock of the University of Sheffield, England, and his colleagues assessed the biophysical, biologic, and functional properties of the developing neonatal stratum corneum (SC) from birth to 4 weeks of age in 115 healthy, full-term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation) neonates from the OBSERVE (Oil in Baby Skincare) randomized study birth cohort recruited at Saint Mary’s Hospital, Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, between September 2013 and June 2014.

For comparative purposes, an unrelated cohort of 20 adults with healthy skin was recruited from the local community between January and April 2015 (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14568).

The researchers found that the biophysical properties of the neonatal SC are transitional from birth. For example, overall transepidermal water loss (TEWL) increased significantly during the first 4 weeks of infant life. Compared with adult skin, the newborn infant SC was found to be drier and more alkaline. In addition, levels of superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity at birth did not differ between newborns and adults, while levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors (NMF) were significantly lower at birth than in adulthood.

The increased chymotrypsinlike protease activity and NMF at 4 weeks of age exceeded levels found in healthy adults, rather than reaching their mature state. Compared with adult skin, the skin of infants is functionally immature, with undeveloped mechanisms of desquamation and differentiation, the investigators noted.

Further analysis revealed a correlation between TEWL and both superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity and filaggrin-derived NMF at birth.

To explore that link, the researchers stratified the neonatal cohort according to TEWL percentile. The neonates in the 76th-100th percentile, the highest TEWL at birth, showed significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived NMF, compared with neonates in lower percentiles. Therefore, those neonates are at highest risk for developing atopic dermatitis, the study authors said.

The findings indicate a need for infant skin care regimens that protect and support normal barrier development from birth, the researchers noted. They also suggested that clinical strategies targeting the early mechanisms of barrier breakdown could act as preventive measures in neonates at increased risk of developing atopic dermatitis.

The research was funded jointly by the University of Sheffield and a doctoral research fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Neonates with the highest transepidermal water loss at birth, likely mediated through an impaired epidermal barrier, show significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors, which may predispose them to the development of atopic dermatitis, according to a report published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

John Chittock of the University of Sheffield, England, and his colleagues assessed the biophysical, biologic, and functional properties of the developing neonatal stratum corneum (SC) from birth to 4 weeks of age in 115 healthy, full-term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation) neonates from the OBSERVE (Oil in Baby Skincare) randomized study birth cohort recruited at Saint Mary’s Hospital, Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, between September 2013 and June 2014.

For comparative purposes, an unrelated cohort of 20 adults with healthy skin was recruited from the local community between January and April 2015 (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Mar 19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14568).

The researchers found that the biophysical properties of the neonatal SC are transitional from birth. For example, overall transepidermal water loss (TEWL) increased significantly during the first 4 weeks of infant life. Compared with adult skin, the newborn infant SC was found to be drier and more alkaline. In addition, levels of superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity at birth did not differ between newborns and adults, while levels of filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factors (NMF) were significantly lower at birth than in adulthood.

The increased chymotrypsinlike protease activity and NMF at 4 weeks of age exceeded levels found in healthy adults, rather than reaching their mature state. Compared with adult skin, the skin of infants is functionally immature, with undeveloped mechanisms of desquamation and differentiation, the investigators noted.

Further analysis revealed a correlation between TEWL and both superficial chymotrypsinlike protease activity and filaggrin-derived NMF at birth.

To explore that link, the researchers stratified the neonatal cohort according to TEWL percentile. The neonates in the 76th-100th percentile, the highest TEWL at birth, showed significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of filaggrin-derived NMF, compared with neonates in lower percentiles. Therefore, those neonates are at highest risk for developing atopic dermatitis, the study authors said.

The findings indicate a need for infant skin care regimens that protect and support normal barrier development from birth, the researchers noted. They also suggested that clinical strategies targeting the early mechanisms of barrier breakdown could act as preventive measures in neonates at increased risk of developing atopic dermatitis.

The research was funded jointly by the University of Sheffield and a doctoral research fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Some infants are predisposed to epidermal barrier breakdown and the development of atopic dermatitis through elevated protease activity and reduced levels of natural moisturizing factors at birth.

Major finding: Significantly elevated chymotrypsinlike protease activity and reduced levels of natural moisturizing factors were associated with impaired epidermal barrier function at birth.

Data sources: The OBSERVE study birth cohort included a total of 115 healthy, full-term (at least 37 weeks’ gestation) neonates recruited at Saint Mary’s Hospital, Central Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, between September 2013 and June 2014, as well as an unrelated cohort of 20 adults with healthy skin recruited from the local community between January and April 2015.

Disclosures: This independent research was funded jointly by the University of Sheffield and a Doctoral Research Fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Postvaccination anaphylaxis still possible with certain vaccines

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

New findings confirm that although it is rare, postvaccination anaphylaxis can still occur with certain vaccines.

Dr. Michael M. McNeil of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and his associates identified 17,606,500 vaccination visits from Jan. 1, 2009, through Dec. 31, 2011, at which 25,173,965 vaccine doses were administered. The researchers identified 76 cases of chart-confirmed anaphylaxis; 33 anaphylaxis cases were associated with vaccination, and 43 were attributed to other causes.

Inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) was the major contributor to vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases in the population, although the rate (1.35 cases per 1 million vaccine doses of TIV given alone) was similar to the rate for all vaccines. The postvaccination anaphylaxis case rate not involving TIV was 1.32 per million vaccine doses.

The study factored in race, age, gender, symptoms, and history of the patients. There were no deaths, and only 1 patient (3%) was hospitalized. A total of 28 of the 33 vaccine-triggered anaphylaxis cases involved patients with a history of atopy.

“Although anaphylaxis after immunization is rare, its immediate onset (usually within minutes) and life-threatening nature require that all personnel and facilities providing vaccinations have procedures in place for anaphylaxis management,” the investigators noted. “Additional provider education concerning current recommendations for treatment and follow-up appears to be warranted.”

Find the full story in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (2016 Mar;137[3]:868-78).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

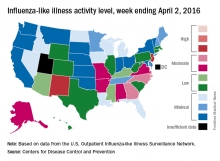

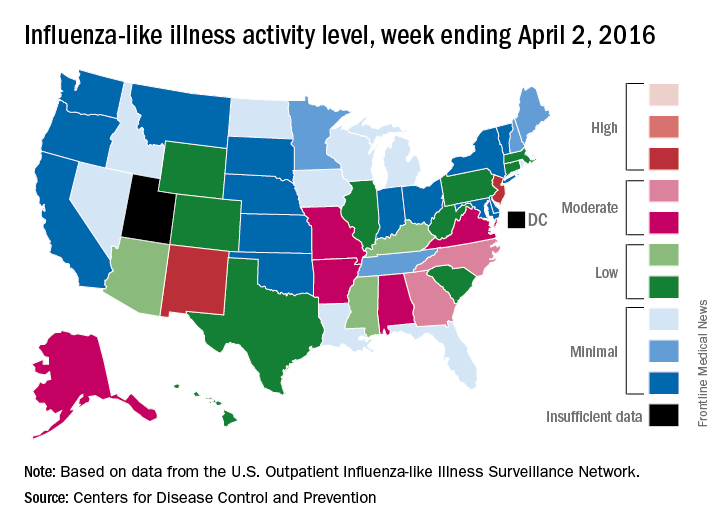

U.S. flu activity continues to drop, but still widespread

A third straight week of reduced influenza-like illness (ILI) left the U.S. with no states at the highest level of ILI activity for the first time since early February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The states with the highest activity for the week ending April 2, 2016, were New Jersey and New Mexico, and both were at level 8 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, putting them on the low end of the “high” range. States in the “moderate” range were Georgia and North Carolina at level 7 and Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Missouri, and Virginia at level 6, according to a report from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.4% for the week, down from 2.9% the week before but still above the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 24.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-16 flu season.

There were seven flu-related pediatric deaths reported – all of them occurring during earlier weeks. So far, 40 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, with California having the highest number (9). The CDC said 7.4% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.1% for week 13 of the flu season.

A third straight week of reduced influenza-like illness (ILI) left the U.S. with no states at the highest level of ILI activity for the first time since early February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The states with the highest activity for the week ending April 2, 2016, were New Jersey and New Mexico, and both were at level 8 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, putting them on the low end of the “high” range. States in the “moderate” range were Georgia and North Carolina at level 7 and Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Missouri, and Virginia at level 6, according to a report from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.4% for the week, down from 2.9% the week before but still above the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 24.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-16 flu season.

There were seven flu-related pediatric deaths reported – all of them occurring during earlier weeks. So far, 40 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, with California having the highest number (9). The CDC said 7.4% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.1% for week 13 of the flu season.

A third straight week of reduced influenza-like illness (ILI) left the U.S. with no states at the highest level of ILI activity for the first time since early February, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The states with the highest activity for the week ending April 2, 2016, were New Jersey and New Mexico, and both were at level 8 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale, putting them on the low end of the “high” range. States in the “moderate” range were Georgia and North Carolina at level 7 and Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Missouri, and Virginia at level 6, according to a report from the CDC’s Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet).

The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI was 2.4% for the week, down from 2.9% the week before but still above the national baseline of 2.1%, the CDC said. The CDC also reported a cumulative rate of 24.4 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population for the 2015-16 flu season.

There were seven flu-related pediatric deaths reported – all of them occurring during earlier weeks. So far, 40 flu-related pediatric deaths have been reported during the 2015-2016 season, with California having the highest number (9). The CDC said 7.4% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to pneumonia and influenza. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.1% for week 13 of the flu season.

Clinical Guidelines: Evaluating suspected acute pulmonary embolism

When a patient comes to the office or emergency department complaining of shortness of breath, acute pulmonary embolism is a diagnosis that must be considered.

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE) – which include tachycardia, shortness of breath, and chest pain – are nonspecific. So, it is important to have a well-thought-out approach to make the diagnosis in patients who have PE and avoid unnecessary tests and risks in patients with a low likelihood of PE.

New guidelines from the American College of Physicians suggest a graded approach to diagnostic testing based on a patient’s estimated pre-test probability of having PE.

When deciding whether to test for PE and which test to order, it is essential to determine the likelihood that a patient’s symptoms are due to PE. Validated decision-support tests include the Well’s Criteria, Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC), and the revised Geneva score. Although they have been recommended for years, these tests often are not used. The guidelines note that the accuracy of an experienced clinician’s gut sense appears to be similar to that of the validated decision tools.

The first decision is whether to do any testing at all. PERC was developed in response to the growing and inappropriate use of D-dimer testing to rule out PE in situations with very low clinical suspicion. The ACP guidelines discuss a meta-analysis of 12 studies, which determined that the overall proportion of missed PEs in patients who had a negative PERC score was 0.3%.

PERC criteria are age younger than 50 years, heart rate less than 100 beats per minute, oxygen saturation greater than 94% on room air, no unilateral leg swelling, no hemoptysis, no surgery or trauma, no history of venous thromboembolism, and no estrogen use. The PERC test is negative when an individual meets all of the criteria above.

It is recommended that, in patients felt to be at low risk and whose PERC test is negative, then no other workup should be done. In this circumstance, “the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing.”

If the PERC test is positive, then low-risk patients should undergo a highly sensitive D-dimer test. When used this way, the PERC tool decreases the use of D-dimer testing in patients who otherwise would have been tested inappropriately.

For intermediate-risk patients, the first test to obtain is a highly sensitive D-dimer test. The ACP guidelines summarized two recent studies – one using the Well’s Criteria and the other a revised Geneva score – which examined D-dimer testing specifically in intermediate-risk groups.

The studies evaluated 1,679 and 330 patients, respectively, at intermediate risk and found that a normal D-dimer level in these patients was 99.5% and 100% sensitive, respectively, for excluding PE on CT. Therefore, patients at both low- and intermediate-level risk should be screened first with a D-dimer rather than going directly to imaging.

When evaluating D-dimer results, a threshold of greater than 500 ng/mL usually indicates a positive test. However, in patients older than 50 years, the guidelines note that it may be more accurate to use a D-dimer level equal to a patient’s age multiplied by 10 ng/mL. Because it is a very sensitive test, a negative D-dimer test indicates no further testing is needed, and there is no reason to obtain a CT scan.

In patients believed to be at high risk of having PE, either through the use of a validated clinical decision tool or by clinical gestalt, a negative D-dimer test is not sensitive enough to rule out PE. Patients who are deemed to be at high risk of having PE should go directly to evaluation by CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Pulmonary ventilation/perfusion scanning should be used when CTPA is unavailable or contraindicated.

The bottom line

• The first step when evaluating a patient is to determine his or her pretest probability of PE using either a clinical tool or clinical judgment. The Well’s Criteria and Geneva score have been validated and are considered equally accurate, and neither has been shown to be superior to risk stratification using clinical gestalt.

• Low pretest probability of PE: First, use the PERC criteria. In those patients who meet all eight rule-out criteria, DO NOT order a D-dimer; the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing. Those who do not meet all eight criteria should undergo a D-dimer. A normal D-dimer level is sufficient to rule out PE, and imaging studies are not needed. An elevated plasma D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• Intermediate pretest probability of PE: D-dimer testing is the first step. A negative D-dimer has sufficient negative predictive value to eliminate the need for further testing. An elevated D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• High pretest probability of PE: In patients with a high pretest probability secondary to either clinical gestalt or a clinical prediction tool, evaluation by CTPA is warranted.

References

• “Evaluation of Patients With Suspected Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Best Practice Advice From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians.” Ann Intern Med. 2015 Nov 3;163(9):701-11.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Vandergrift is a first-year resident in the program.

When a patient comes to the office or emergency department complaining of shortness of breath, acute pulmonary embolism is a diagnosis that must be considered.

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE) – which include tachycardia, shortness of breath, and chest pain – are nonspecific. So, it is important to have a well-thought-out approach to make the diagnosis in patients who have PE and avoid unnecessary tests and risks in patients with a low likelihood of PE.

New guidelines from the American College of Physicians suggest a graded approach to diagnostic testing based on a patient’s estimated pre-test probability of having PE.

When deciding whether to test for PE and which test to order, it is essential to determine the likelihood that a patient’s symptoms are due to PE. Validated decision-support tests include the Well’s Criteria, Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC), and the revised Geneva score. Although they have been recommended for years, these tests often are not used. The guidelines note that the accuracy of an experienced clinician’s gut sense appears to be similar to that of the validated decision tools.

The first decision is whether to do any testing at all. PERC was developed in response to the growing and inappropriate use of D-dimer testing to rule out PE in situations with very low clinical suspicion. The ACP guidelines discuss a meta-analysis of 12 studies, which determined that the overall proportion of missed PEs in patients who had a negative PERC score was 0.3%.

PERC criteria are age younger than 50 years, heart rate less than 100 beats per minute, oxygen saturation greater than 94% on room air, no unilateral leg swelling, no hemoptysis, no surgery or trauma, no history of venous thromboembolism, and no estrogen use. The PERC test is negative when an individual meets all of the criteria above.

It is recommended that, in patients felt to be at low risk and whose PERC test is negative, then no other workup should be done. In this circumstance, “the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing.”

If the PERC test is positive, then low-risk patients should undergo a highly sensitive D-dimer test. When used this way, the PERC tool decreases the use of D-dimer testing in patients who otherwise would have been tested inappropriately.

For intermediate-risk patients, the first test to obtain is a highly sensitive D-dimer test. The ACP guidelines summarized two recent studies – one using the Well’s Criteria and the other a revised Geneva score – which examined D-dimer testing specifically in intermediate-risk groups.

The studies evaluated 1,679 and 330 patients, respectively, at intermediate risk and found that a normal D-dimer level in these patients was 99.5% and 100% sensitive, respectively, for excluding PE on CT. Therefore, patients at both low- and intermediate-level risk should be screened first with a D-dimer rather than going directly to imaging.

When evaluating D-dimer results, a threshold of greater than 500 ng/mL usually indicates a positive test. However, in patients older than 50 years, the guidelines note that it may be more accurate to use a D-dimer level equal to a patient’s age multiplied by 10 ng/mL. Because it is a very sensitive test, a negative D-dimer test indicates no further testing is needed, and there is no reason to obtain a CT scan.

In patients believed to be at high risk of having PE, either through the use of a validated clinical decision tool or by clinical gestalt, a negative D-dimer test is not sensitive enough to rule out PE. Patients who are deemed to be at high risk of having PE should go directly to evaluation by CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Pulmonary ventilation/perfusion scanning should be used when CTPA is unavailable or contraindicated.

The bottom line

• The first step when evaluating a patient is to determine his or her pretest probability of PE using either a clinical tool or clinical judgment. The Well’s Criteria and Geneva score have been validated and are considered equally accurate, and neither has been shown to be superior to risk stratification using clinical gestalt.

• Low pretest probability of PE: First, use the PERC criteria. In those patients who meet all eight rule-out criteria, DO NOT order a D-dimer; the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing. Those who do not meet all eight criteria should undergo a D-dimer. A normal D-dimer level is sufficient to rule out PE, and imaging studies are not needed. An elevated plasma D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• Intermediate pretest probability of PE: D-dimer testing is the first step. A negative D-dimer has sufficient negative predictive value to eliminate the need for further testing. An elevated D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• High pretest probability of PE: In patients with a high pretest probability secondary to either clinical gestalt or a clinical prediction tool, evaluation by CTPA is warranted.

References

• “Evaluation of Patients With Suspected Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Best Practice Advice From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians.” Ann Intern Med. 2015 Nov 3;163(9):701-11.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Vandergrift is a first-year resident in the program.

When a patient comes to the office or emergency department complaining of shortness of breath, acute pulmonary embolism is a diagnosis that must be considered.

The signs and symptoms of pulmonary embolism (PE) – which include tachycardia, shortness of breath, and chest pain – are nonspecific. So, it is important to have a well-thought-out approach to make the diagnosis in patients who have PE and avoid unnecessary tests and risks in patients with a low likelihood of PE.

New guidelines from the American College of Physicians suggest a graded approach to diagnostic testing based on a patient’s estimated pre-test probability of having PE.

When deciding whether to test for PE and which test to order, it is essential to determine the likelihood that a patient’s symptoms are due to PE. Validated decision-support tests include the Well’s Criteria, Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC), and the revised Geneva score. Although they have been recommended for years, these tests often are not used. The guidelines note that the accuracy of an experienced clinician’s gut sense appears to be similar to that of the validated decision tools.

The first decision is whether to do any testing at all. PERC was developed in response to the growing and inappropriate use of D-dimer testing to rule out PE in situations with very low clinical suspicion. The ACP guidelines discuss a meta-analysis of 12 studies, which determined that the overall proportion of missed PEs in patients who had a negative PERC score was 0.3%.

PERC criteria are age younger than 50 years, heart rate less than 100 beats per minute, oxygen saturation greater than 94% on room air, no unilateral leg swelling, no hemoptysis, no surgery or trauma, no history of venous thromboembolism, and no estrogen use. The PERC test is negative when an individual meets all of the criteria above.

It is recommended that, in patients felt to be at low risk and whose PERC test is negative, then no other workup should be done. In this circumstance, “the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing.”

If the PERC test is positive, then low-risk patients should undergo a highly sensitive D-dimer test. When used this way, the PERC tool decreases the use of D-dimer testing in patients who otherwise would have been tested inappropriately.

For intermediate-risk patients, the first test to obtain is a highly sensitive D-dimer test. The ACP guidelines summarized two recent studies – one using the Well’s Criteria and the other a revised Geneva score – which examined D-dimer testing specifically in intermediate-risk groups.

The studies evaluated 1,679 and 330 patients, respectively, at intermediate risk and found that a normal D-dimer level in these patients was 99.5% and 100% sensitive, respectively, for excluding PE on CT. Therefore, patients at both low- and intermediate-level risk should be screened first with a D-dimer rather than going directly to imaging.

When evaluating D-dimer results, a threshold of greater than 500 ng/mL usually indicates a positive test. However, in patients older than 50 years, the guidelines note that it may be more accurate to use a D-dimer level equal to a patient’s age multiplied by 10 ng/mL. Because it is a very sensitive test, a negative D-dimer test indicates no further testing is needed, and there is no reason to obtain a CT scan.

In patients believed to be at high risk of having PE, either through the use of a validated clinical decision tool or by clinical gestalt, a negative D-dimer test is not sensitive enough to rule out PE. Patients who are deemed to be at high risk of having PE should go directly to evaluation by CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA). Pulmonary ventilation/perfusion scanning should be used when CTPA is unavailable or contraindicated.

The bottom line

• The first step when evaluating a patient is to determine his or her pretest probability of PE using either a clinical tool or clinical judgment. The Well’s Criteria and Geneva score have been validated and are considered equally accurate, and neither has been shown to be superior to risk stratification using clinical gestalt.

• Low pretest probability of PE: First, use the PERC criteria. In those patients who meet all eight rule-out criteria, DO NOT order a D-dimer; the risk of PE is lower than the risk of testing. Those who do not meet all eight criteria should undergo a D-dimer. A normal D-dimer level is sufficient to rule out PE, and imaging studies are not needed. An elevated plasma D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• Intermediate pretest probability of PE: D-dimer testing is the first step. A negative D-dimer has sufficient negative predictive value to eliminate the need for further testing. An elevated D-dimer, ideally adjusted for age, should prompt evaluation by CTPA.

• High pretest probability of PE: In patients with a high pretest probability secondary to either clinical gestalt or a clinical prediction tool, evaluation by CTPA is warranted.

References

• “Evaluation of Patients With Suspected Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Best Practice Advice From the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians.” Ann Intern Med. 2015 Nov 3;163(9):701-11.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Vandergrift is a first-year resident in the program.

Acute otitis media rates have dropped, but tied to upper respiratory infections

Close to half of all infants have an episode of acute otitis media by age 1 year, but incidence appears to have dropped in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era, a recent study found.

“We clearly showed that frequent viral infections, bacterial colonization, and lack of breastfeeding are major acute otitis media (AOM) risk factors,” reported Dr. Tasnee Chonmaitree and her associates at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston (Pediatrics 2016 March 28 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3555). “It is likely that medical interventions in the past few decades, such as the use of pneumococcal and influenza virus vaccines, higher breastfeeding rates and decreased smoking, helped reduce AOM incidence.”

Between October 2008 and March 2014, researchers began tracking 367 infants from birth until they experienced their first case of AOM (and then on to age 6 months) or until they reached age 12 months; 85% completed the study. Preterm infants and those with anatomic defects or major medical problems were not included. The researchers collected nasopharyngeal specimens once during each of the first 6 months, once in the child’s 9th month, and during any viral upper respiratory infections to conduct bacterial cultures and viral polymerase chain reactions for 13 respiratory viruses.

During the course of the study, 305 children experienced a total of 887 upper respiratory infections, and 143 children experienced a total of 180 AOM episodes. Upper respiratory infections occurred at a rate of 3.2 episodes per child per year, and lower respiratory infections occurred at a rate of 0.24 episodes per child per year. Clinical sinusitis complications followed 4.6% of the upper respiratory infections, and lower respiratory infections followed 7.6%.

The rate of AOM was 0.67 episodes per child per year. Although only 6% of the infants had experienced AOM by age 3 months, that rose to nearly a quarter (23%) of the children at age 6 months and nearly half (46%) at age 12 months. Still, it remained below the rates of 18% by 3 months and 30%-39% by 6 months that had been reported in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Children who had AOM experienced 4.7 upper respiratory infections per year, compared with 2.3 episodes per year in children without AOM (P less than .002). They also had significantly greater pathogenic bacterial colonization overall and for Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, in their monthly nasopharyngeal specimens, although Streptococcus pneumoniae rates were not significantly greater.

“Interestingly, we found that not only viruses increased upper respiratory infection risk; M. catarrhalis and S. pneumoniae also increased upper respiratory infection risk,” the authors wrote “On the other hand, we found better protection for S. pneumoniae (infants born after 2010) associated with decreased upper respiratory infection risk.”

Upper respiratory infections were 74% more likely among children attending day care, and 7% more likely among children with at least one sibling at home. These infections were 37% less likely in children exclusively breastfed at least 6 months, 16% less likely in children born after February 2010, and 4% less likely for each month of any breastfeeding.

Similarly, AOM episodes were 60% less likely in children exclusively breastfed at least 3 months, and 15% less likely for each month children were breastfed.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported no disclosures.