User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The pandemic changed smokers, but farming didn’t change humans

Pandemic smoking: More or less?

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed a lot of habits in people, for better or worse. Some people may have turned to food and alcohol for comfort, while others started on health kicks to emerge from the ordeal as new people. Well, the same can be said about smokers.

New evidence comes from a survey conducted from May to July 2020 of 694 current and former smokers with an average age of 53 years. All had been hospitalized prior to the pandemic and had previously participated in clinical trials to for smoking cessation in Boston, Nashville, and Pittsburgh hospitals.

Researchers found that 32% of participants smoked more, 37% smoked less, and 31% made no change in their smoking habits. By the time of the survey, 28% of former smokers had relapsed. Although 68% of the participants believed smoking increased the risk of getting COVID-19, that still didn’t stop some people from smoking more. Why?

Respondents “might have increased their smoking due to stress and boredom. On the other hand, the fear of catching COVID might have led them to cut down or quit smoking,” said lead author Nancy A. Rigotti, MD. “Even before the pandemic, tobacco smoking was the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. COVID-19 has given smokers yet another good reason to stop smoking.”

This creates an opportunity for physicians to preach the gospel to smokers about their vulnerability to respiratory disease in hopes of getting them to quit for good. We just wish the same could be said for all of our excessive pandemic online shopping.

3,000 years and just one pair of genomes to wear

Men and women are different. We’ll give you a moment to pick your jaw off the ground.

It makes sense though, the sexes being different, especially when you look at the broader animal kingdom. The males and females of many species are slightly different when it comes to size and shape, but there’s a big question that literally only anthropologists have asked: Were human males and females more different in the past than they are today?

To be more specific, some scientists believe that males and females grew more similar when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a farming-based lifestyle, as agriculture encouraged a more equitable division of labor. Others believe that the differences come down to random chance.

Researchers from Penn State University analyzed genomic data from over 350,000 males and females stored in the UK Biobank and looked at the recent (within the last ~3,000 years; post-agriculture adoption in Britain) evolutionary histories of these loci. Height, body mass, hip circumference, body fat percentage, and waist circumference were analyzed, and while there were thousands of differences in the genomes, only one trait occurred more frequently during that time period: Females gained a significantly higher body fat content than males.

It’s a sad day then for the millions of people who were big fans of the “farming caused men and women to become more similar” theory. Count the LOTME crew among them. Be honest: Wouldn’t life be so much simpler if men and women were exactly the same? Just think about it, no more arguments about leaving the toilet seat up. It’d be worth it just for that.

Proteins don’t lie

Research published in Open Biology shows that the human brain contains 14,315 different proteins. The team conducting that study wanted to find out which organ was the most similar to the old brain box, so they did protein counts for the 32 other major tissue types, including heart, salivary gland, lung, spleen, and endometrium.

The tissue with the most proteins in common with the center of human intelligence? You’re thinking it has to be colon at this point, right? We were sure it was going to be colon, but it’s not.

The winner, with 13,442 shared proteins, is the testes. The testes have 15,687 proteins, of which 85.7% are shared with the brain. The researchers, sadly, did not provide protein counts for the other tissue types, but we bet colon was a close second.

Dreaming about COVID?

We thought we were the only ones who have been having crazy dreams lately. Each one seems crazier and more vivid than the one before. Have you been having weird dreams lately?

This is likely your brain’s coping mechanism to handle your pandemic stress, according to Dr. Erik Hoel of Tufts University. Dreams that are crazy and scary might make real life seem lighter and simpler. He calls it the “overfitted brain hypothesis.”

“It is their very strangeness that gives them their biological function,” Dr. Hoel said. It literally makes you feel like COVID-19 and lockdowns aren’t as scary as they seem.

We always knew our minds were powerful things. Apparently, your brain gets tired of everyday familiarity just like you do, and it creates crazy dreams to keep things interesting.

Just remember: That recurring dream that you’re back in college and missing 10 assignments is there to help you, not scare you! Even though it is pretty scary.

Pandemic smoking: More or less?

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed a lot of habits in people, for better or worse. Some people may have turned to food and alcohol for comfort, while others started on health kicks to emerge from the ordeal as new people. Well, the same can be said about smokers.

New evidence comes from a survey conducted from May to July 2020 of 694 current and former smokers with an average age of 53 years. All had been hospitalized prior to the pandemic and had previously participated in clinical trials to for smoking cessation in Boston, Nashville, and Pittsburgh hospitals.

Researchers found that 32% of participants smoked more, 37% smoked less, and 31% made no change in their smoking habits. By the time of the survey, 28% of former smokers had relapsed. Although 68% of the participants believed smoking increased the risk of getting COVID-19, that still didn’t stop some people from smoking more. Why?

Respondents “might have increased their smoking due to stress and boredom. On the other hand, the fear of catching COVID might have led them to cut down or quit smoking,” said lead author Nancy A. Rigotti, MD. “Even before the pandemic, tobacco smoking was the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. COVID-19 has given smokers yet another good reason to stop smoking.”

This creates an opportunity for physicians to preach the gospel to smokers about their vulnerability to respiratory disease in hopes of getting them to quit for good. We just wish the same could be said for all of our excessive pandemic online shopping.

3,000 years and just one pair of genomes to wear

Men and women are different. We’ll give you a moment to pick your jaw off the ground.

It makes sense though, the sexes being different, especially when you look at the broader animal kingdom. The males and females of many species are slightly different when it comes to size and shape, but there’s a big question that literally only anthropologists have asked: Were human males and females more different in the past than they are today?

To be more specific, some scientists believe that males and females grew more similar when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a farming-based lifestyle, as agriculture encouraged a more equitable division of labor. Others believe that the differences come down to random chance.

Researchers from Penn State University analyzed genomic data from over 350,000 males and females stored in the UK Biobank and looked at the recent (within the last ~3,000 years; post-agriculture adoption in Britain) evolutionary histories of these loci. Height, body mass, hip circumference, body fat percentage, and waist circumference were analyzed, and while there were thousands of differences in the genomes, only one trait occurred more frequently during that time period: Females gained a significantly higher body fat content than males.

It’s a sad day then for the millions of people who were big fans of the “farming caused men and women to become more similar” theory. Count the LOTME crew among them. Be honest: Wouldn’t life be so much simpler if men and women were exactly the same? Just think about it, no more arguments about leaving the toilet seat up. It’d be worth it just for that.

Proteins don’t lie

Research published in Open Biology shows that the human brain contains 14,315 different proteins. The team conducting that study wanted to find out which organ was the most similar to the old brain box, so they did protein counts for the 32 other major tissue types, including heart, salivary gland, lung, spleen, and endometrium.

The tissue with the most proteins in common with the center of human intelligence? You’re thinking it has to be colon at this point, right? We were sure it was going to be colon, but it’s not.

The winner, with 13,442 shared proteins, is the testes. The testes have 15,687 proteins, of which 85.7% are shared with the brain. The researchers, sadly, did not provide protein counts for the other tissue types, but we bet colon was a close second.

Dreaming about COVID?

We thought we were the only ones who have been having crazy dreams lately. Each one seems crazier and more vivid than the one before. Have you been having weird dreams lately?

This is likely your brain’s coping mechanism to handle your pandemic stress, according to Dr. Erik Hoel of Tufts University. Dreams that are crazy and scary might make real life seem lighter and simpler. He calls it the “overfitted brain hypothesis.”

“It is their very strangeness that gives them their biological function,” Dr. Hoel said. It literally makes you feel like COVID-19 and lockdowns aren’t as scary as they seem.

We always knew our minds were powerful things. Apparently, your brain gets tired of everyday familiarity just like you do, and it creates crazy dreams to keep things interesting.

Just remember: That recurring dream that you’re back in college and missing 10 assignments is there to help you, not scare you! Even though it is pretty scary.

Pandemic smoking: More or less?

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed a lot of habits in people, for better or worse. Some people may have turned to food and alcohol for comfort, while others started on health kicks to emerge from the ordeal as new people. Well, the same can be said about smokers.

New evidence comes from a survey conducted from May to July 2020 of 694 current and former smokers with an average age of 53 years. All had been hospitalized prior to the pandemic and had previously participated in clinical trials to for smoking cessation in Boston, Nashville, and Pittsburgh hospitals.

Researchers found that 32% of participants smoked more, 37% smoked less, and 31% made no change in their smoking habits. By the time of the survey, 28% of former smokers had relapsed. Although 68% of the participants believed smoking increased the risk of getting COVID-19, that still didn’t stop some people from smoking more. Why?

Respondents “might have increased their smoking due to stress and boredom. On the other hand, the fear of catching COVID might have led them to cut down or quit smoking,” said lead author Nancy A. Rigotti, MD. “Even before the pandemic, tobacco smoking was the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. COVID-19 has given smokers yet another good reason to stop smoking.”

This creates an opportunity for physicians to preach the gospel to smokers about their vulnerability to respiratory disease in hopes of getting them to quit for good. We just wish the same could be said for all of our excessive pandemic online shopping.

3,000 years and just one pair of genomes to wear

Men and women are different. We’ll give you a moment to pick your jaw off the ground.

It makes sense though, the sexes being different, especially when you look at the broader animal kingdom. The males and females of many species are slightly different when it comes to size and shape, but there’s a big question that literally only anthropologists have asked: Were human males and females more different in the past than they are today?

To be more specific, some scientists believe that males and females grew more similar when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a farming-based lifestyle, as agriculture encouraged a more equitable division of labor. Others believe that the differences come down to random chance.

Researchers from Penn State University analyzed genomic data from over 350,000 males and females stored in the UK Biobank and looked at the recent (within the last ~3,000 years; post-agriculture adoption in Britain) evolutionary histories of these loci. Height, body mass, hip circumference, body fat percentage, and waist circumference were analyzed, and while there were thousands of differences in the genomes, only one trait occurred more frequently during that time period: Females gained a significantly higher body fat content than males.

It’s a sad day then for the millions of people who were big fans of the “farming caused men and women to become more similar” theory. Count the LOTME crew among them. Be honest: Wouldn’t life be so much simpler if men and women were exactly the same? Just think about it, no more arguments about leaving the toilet seat up. It’d be worth it just for that.

Proteins don’t lie

Research published in Open Biology shows that the human brain contains 14,315 different proteins. The team conducting that study wanted to find out which organ was the most similar to the old brain box, so they did protein counts for the 32 other major tissue types, including heart, salivary gland, lung, spleen, and endometrium.

The tissue with the most proteins in common with the center of human intelligence? You’re thinking it has to be colon at this point, right? We were sure it was going to be colon, but it’s not.

The winner, with 13,442 shared proteins, is the testes. The testes have 15,687 proteins, of which 85.7% are shared with the brain. The researchers, sadly, did not provide protein counts for the other tissue types, but we bet colon was a close second.

Dreaming about COVID?

We thought we were the only ones who have been having crazy dreams lately. Each one seems crazier and more vivid than the one before. Have you been having weird dreams lately?

This is likely your brain’s coping mechanism to handle your pandemic stress, according to Dr. Erik Hoel of Tufts University. Dreams that are crazy and scary might make real life seem lighter and simpler. He calls it the “overfitted brain hypothesis.”

“It is their very strangeness that gives them their biological function,” Dr. Hoel said. It literally makes you feel like COVID-19 and lockdowns aren’t as scary as they seem.

We always knew our minds were powerful things. Apparently, your brain gets tired of everyday familiarity just like you do, and it creates crazy dreams to keep things interesting.

Just remember: That recurring dream that you’re back in college and missing 10 assignments is there to help you, not scare you! Even though it is pretty scary.

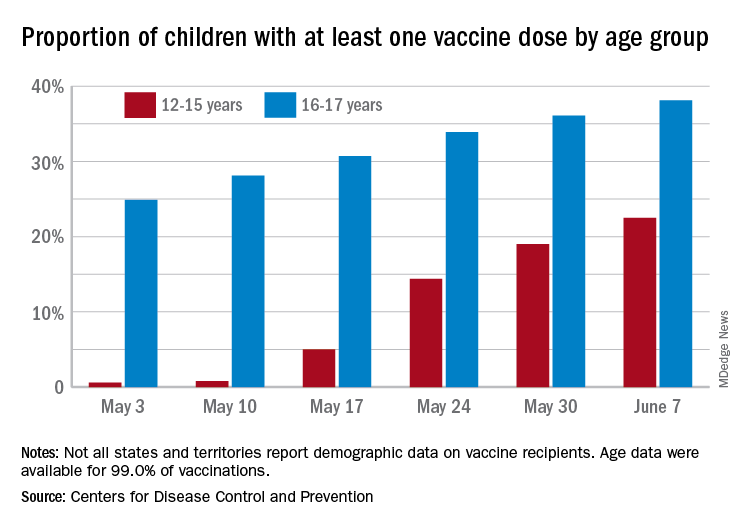

By the numbers: Children and COVID-19 prevention

Over 6.3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine have been administered to children aged 12-17 years as of June 7, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest results from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker show that , with the corresponding figures for vaccine completion coming in at 4.1% and 26.4%. Compared with a week earlier, those numbers are up by 15.4% (one dose) and 486% (completion) for the younger group and by 4.7% and 8.6%, respectively, for the older children.

Children aged 12-15 represented 17.9% of all persons who initiated vaccination in the last 14 days up to June 7, while children aged 16-17 made up 4.8% of vaccine initiation over that period. The 25- to 39-year-olds, at 23.7% of all vaccine initiators, were the only group ahead of those aged 12-15, and the 50- to 64-year-olds were just behind at 17.7%, the CDC data show.

Both groups of children were on the low side, however, when it came to vaccine completion in the last 14 days, with those aged 12-15 at 6.7% of the total and those aged 16-17 years at 4.3%. The only age groups lower than that were ≥75 at 3.5% and <12 at 0.2%, and the highest share of vaccine completion was 26.0% for those aged 25-39, which also happens to be the group with the largest share of the U.S. population (20.5%), the CDC said.

People considered fully vaccinated are those who have received the second dose of a two-dose series or one dose of a single-shot vaccine, but children under age 18 years are eligible only for the Pfizer-BioNTech version, the CDC noted.

Meanwhile, back on the incidence side of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of new cases in U.S. children for the week ending June 3 was at its lowest point (16,281) since mid-June of 2020, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Cases among children now total 3.99 million, which represents 14.1% of cases among all ages, a proportion that hasn’t increased since mid-May, which hasn’t happened since the two groups started keeping track in mid-April of 2020 in the 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam that report such data by age.

Less encouraging was the CDC’s report that “COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates among adolescents ages 12-17 years increased during March and April, following declines in January and February 2021.”

Children have been experiencing much lower rates of severe disease than those of adults throughout the pandemic, the CDC pointed out, but “recent increases in COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates and the potential for severe disease in adolescents reinforce the importance of continued prevention strategies, including vaccination and the correct and consistent use of masks in those who are not yet fully vaccinated.”

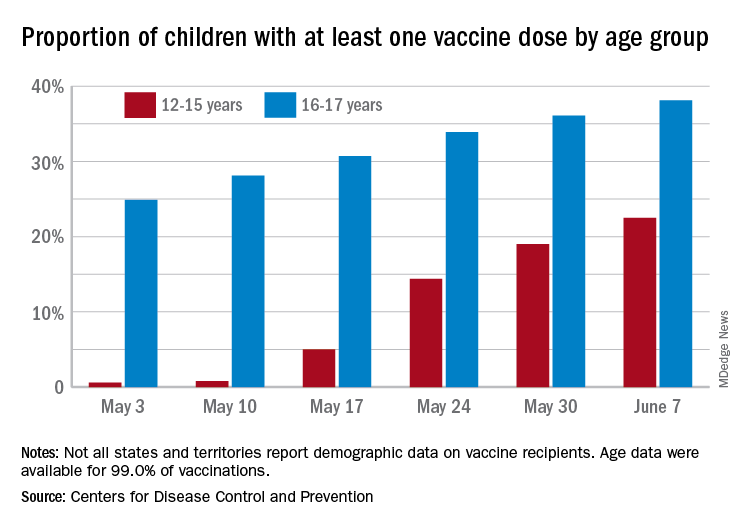

Over 6.3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine have been administered to children aged 12-17 years as of June 7, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest results from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker show that , with the corresponding figures for vaccine completion coming in at 4.1% and 26.4%. Compared with a week earlier, those numbers are up by 15.4% (one dose) and 486% (completion) for the younger group and by 4.7% and 8.6%, respectively, for the older children.

Children aged 12-15 represented 17.9% of all persons who initiated vaccination in the last 14 days up to June 7, while children aged 16-17 made up 4.8% of vaccine initiation over that period. The 25- to 39-year-olds, at 23.7% of all vaccine initiators, were the only group ahead of those aged 12-15, and the 50- to 64-year-olds were just behind at 17.7%, the CDC data show.

Both groups of children were on the low side, however, when it came to vaccine completion in the last 14 days, with those aged 12-15 at 6.7% of the total and those aged 16-17 years at 4.3%. The only age groups lower than that were ≥75 at 3.5% and <12 at 0.2%, and the highest share of vaccine completion was 26.0% for those aged 25-39, which also happens to be the group with the largest share of the U.S. population (20.5%), the CDC said.

People considered fully vaccinated are those who have received the second dose of a two-dose series or one dose of a single-shot vaccine, but children under age 18 years are eligible only for the Pfizer-BioNTech version, the CDC noted.

Meanwhile, back on the incidence side of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of new cases in U.S. children for the week ending June 3 was at its lowest point (16,281) since mid-June of 2020, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Cases among children now total 3.99 million, which represents 14.1% of cases among all ages, a proportion that hasn’t increased since mid-May, which hasn’t happened since the two groups started keeping track in mid-April of 2020 in the 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam that report such data by age.

Less encouraging was the CDC’s report that “COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates among adolescents ages 12-17 years increased during March and April, following declines in January and February 2021.”

Children have been experiencing much lower rates of severe disease than those of adults throughout the pandemic, the CDC pointed out, but “recent increases in COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates and the potential for severe disease in adolescents reinforce the importance of continued prevention strategies, including vaccination and the correct and consistent use of masks in those who are not yet fully vaccinated.”

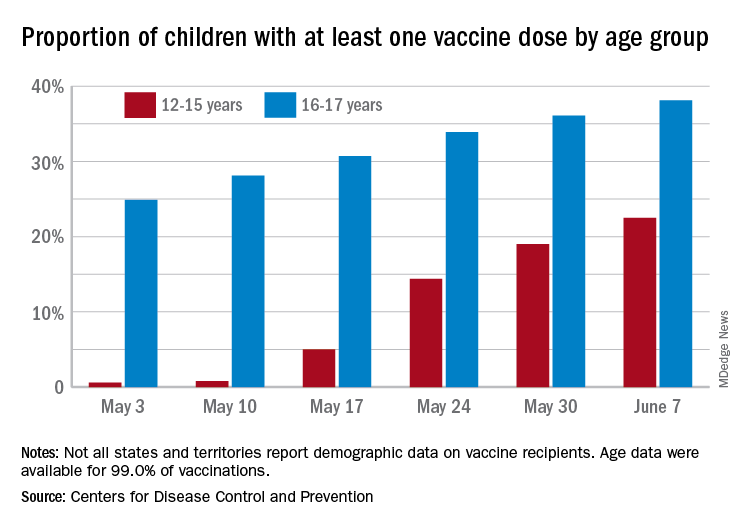

Over 6.3 million doses of COVID-19 vaccine have been administered to children aged 12-17 years as of June 7, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The latest results from the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker show that , with the corresponding figures for vaccine completion coming in at 4.1% and 26.4%. Compared with a week earlier, those numbers are up by 15.4% (one dose) and 486% (completion) for the younger group and by 4.7% and 8.6%, respectively, for the older children.

Children aged 12-15 represented 17.9% of all persons who initiated vaccination in the last 14 days up to June 7, while children aged 16-17 made up 4.8% of vaccine initiation over that period. The 25- to 39-year-olds, at 23.7% of all vaccine initiators, were the only group ahead of those aged 12-15, and the 50- to 64-year-olds were just behind at 17.7%, the CDC data show.

Both groups of children were on the low side, however, when it came to vaccine completion in the last 14 days, with those aged 12-15 at 6.7% of the total and those aged 16-17 years at 4.3%. The only age groups lower than that were ≥75 at 3.5% and <12 at 0.2%, and the highest share of vaccine completion was 26.0% for those aged 25-39, which also happens to be the group with the largest share of the U.S. population (20.5%), the CDC said.

People considered fully vaccinated are those who have received the second dose of a two-dose series or one dose of a single-shot vaccine, but children under age 18 years are eligible only for the Pfizer-BioNTech version, the CDC noted.

Meanwhile, back on the incidence side of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of new cases in U.S. children for the week ending June 3 was at its lowest point (16,281) since mid-June of 2020, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Cases among children now total 3.99 million, which represents 14.1% of cases among all ages, a proportion that hasn’t increased since mid-May, which hasn’t happened since the two groups started keeping track in mid-April of 2020 in the 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam that report such data by age.

Less encouraging was the CDC’s report that “COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates among adolescents ages 12-17 years increased during March and April, following declines in January and February 2021.”

Children have been experiencing much lower rates of severe disease than those of adults throughout the pandemic, the CDC pointed out, but “recent increases in COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates and the potential for severe disease in adolescents reinforce the importance of continued prevention strategies, including vaccination and the correct and consistent use of masks in those who are not yet fully vaccinated.”

First year of life sees initial bleeding episodes in children with von Willebrand disease

To remedy a lack of data on infants and toddlers with von Willebrand disease (VWD), researchers examined data on patients collected from the U.S. Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. They examined birth characteristics, bleeding episodes, and complications experienced by 105 patients with VWD who were younger than 2 years of age.

For these patients, the mean age of diagnosis was 7 months, with little variation by sex. Patients with type 2 VWD were diagnosed earlier than those with types 1 or 3 (P = .04), and those with a family history of VWD were diagnosed approximately 4 months earlier than those with none (P < .001), according to the report by Brandi Dupervil, DHSC, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

Approximately 14% of the patients were born preterm and 13% had low birth weight, proportions that were higher than national preterm birth rates (approximately 12% and 8%, respectively). There was no way of knowing from the data whether this was due to the presence of VWD or other factors, according to the report (Blood Adv. 2021;5[8]:2079-86).

Specialized care

The study found that initial bleeding episodes were most commonly oropharyngeal, related to circumcision, or intracranial or extracranial, and that most initial bleeding episodes occurred within the first year of life, according to the researchers.

Overall, there were 274 bleeding episodes among 73 children, including oral/nasal episodes (38 patients experienced 166 episodes), soft tissue hematomas (15 patients experienced 57 episodes), and head injuries, including skull fractures (13 patients experienced 19 episodes), according to the report.

In terms of treatment, among the two-thirds of the patients who had intervention to prevent or treat bleeding, most received either plasma-derived VW factor/factor VIII concentrates or antifibrinolytics.

Overall, the researchers advocated a team approach to treating these children “including genetic counselors throughout the prepartum period who work to increase expectant mothers’ understanding of the risks associated with having a child with VWD.”

They also recommended the input of “adult and pediatric hematologists, obstetrician gynecologists, genetic counselors, nurses, and social workers throughout the pre- and postpartum period who seek to optimize outcomes and disease management.”

The authors reported that they had no competing interests.

To remedy a lack of data on infants and toddlers with von Willebrand disease (VWD), researchers examined data on patients collected from the U.S. Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. They examined birth characteristics, bleeding episodes, and complications experienced by 105 patients with VWD who were younger than 2 years of age.

For these patients, the mean age of diagnosis was 7 months, with little variation by sex. Patients with type 2 VWD were diagnosed earlier than those with types 1 or 3 (P = .04), and those with a family history of VWD were diagnosed approximately 4 months earlier than those with none (P < .001), according to the report by Brandi Dupervil, DHSC, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

Approximately 14% of the patients were born preterm and 13% had low birth weight, proportions that were higher than national preterm birth rates (approximately 12% and 8%, respectively). There was no way of knowing from the data whether this was due to the presence of VWD or other factors, according to the report (Blood Adv. 2021;5[8]:2079-86).

Specialized care

The study found that initial bleeding episodes were most commonly oropharyngeal, related to circumcision, or intracranial or extracranial, and that most initial bleeding episodes occurred within the first year of life, according to the researchers.

Overall, there were 274 bleeding episodes among 73 children, including oral/nasal episodes (38 patients experienced 166 episodes), soft tissue hematomas (15 patients experienced 57 episodes), and head injuries, including skull fractures (13 patients experienced 19 episodes), according to the report.

In terms of treatment, among the two-thirds of the patients who had intervention to prevent or treat bleeding, most received either plasma-derived VW factor/factor VIII concentrates or antifibrinolytics.

Overall, the researchers advocated a team approach to treating these children “including genetic counselors throughout the prepartum period who work to increase expectant mothers’ understanding of the risks associated with having a child with VWD.”

They also recommended the input of “adult and pediatric hematologists, obstetrician gynecologists, genetic counselors, nurses, and social workers throughout the pre- and postpartum period who seek to optimize outcomes and disease management.”

The authors reported that they had no competing interests.

To remedy a lack of data on infants and toddlers with von Willebrand disease (VWD), researchers examined data on patients collected from the U.S. Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. They examined birth characteristics, bleeding episodes, and complications experienced by 105 patients with VWD who were younger than 2 years of age.

For these patients, the mean age of diagnosis was 7 months, with little variation by sex. Patients with type 2 VWD were diagnosed earlier than those with types 1 or 3 (P = .04), and those with a family history of VWD were diagnosed approximately 4 months earlier than those with none (P < .001), according to the report by Brandi Dupervil, DHSC, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

Approximately 14% of the patients were born preterm and 13% had low birth weight, proportions that were higher than national preterm birth rates (approximately 12% and 8%, respectively). There was no way of knowing from the data whether this was due to the presence of VWD or other factors, according to the report (Blood Adv. 2021;5[8]:2079-86).

Specialized care

The study found that initial bleeding episodes were most commonly oropharyngeal, related to circumcision, or intracranial or extracranial, and that most initial bleeding episodes occurred within the first year of life, according to the researchers.

Overall, there were 274 bleeding episodes among 73 children, including oral/nasal episodes (38 patients experienced 166 episodes), soft tissue hematomas (15 patients experienced 57 episodes), and head injuries, including skull fractures (13 patients experienced 19 episodes), according to the report.

In terms of treatment, among the two-thirds of the patients who had intervention to prevent or treat bleeding, most received either plasma-derived VW factor/factor VIII concentrates or antifibrinolytics.

Overall, the researchers advocated a team approach to treating these children “including genetic counselors throughout the prepartum period who work to increase expectant mothers’ understanding of the risks associated with having a child with VWD.”

They also recommended the input of “adult and pediatric hematologists, obstetrician gynecologists, genetic counselors, nurses, and social workers throughout the pre- and postpartum period who seek to optimize outcomes and disease management.”

The authors reported that they had no competing interests.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

Improving emergency care for children living outside of urban areas

A new physician workforce study documents that almost all clinically active pediatric emergency physicians in the United States – 99% of them – work in urban areas, and that those who do practice in rural areas are significantly older and closer to retirement age.

The portrait of approximately 2,400 self-identified pediatric emergency medicine (EM) physicians may be unsurprising given the overall propensity of physicians – including board-certified general emergency physicians – to practice in urban areas. Even so, it underscores a decades-long concern that many children do not have access to optimal pediatric emergency care.

And the findings highlight the need, the authors say, to keep pressing to improve emergency care for a population of children with “a mortality rate that is already higher than that of its suburban and urban peers (JAMA Network Open 2021;4[5]:e2110084).”

Emergent care of pediatric patients is well within the scope of practice for physicians with training and board certification in general EM, but children and adolescents have different clinical needs and “there are high-stakes scenarios [in children] that we [as emergency physicians] don’t get exposed to as often because we’re not in a children’s hospital or we just don’t have that additional level of training,” said Christopher L. Bennett, MD, MA, of the department of emergency medicine at Stanford University and lead author of the study.

Researchers have documented that some emergency physicians have some discomfort in caring for very ill pediatric patients, he and his coauthors wrote.

Children account for more than 20% of annual ED visits, and most children who seek emergency care in the United States – upwards of 80% – present to general emergency departments. Yet the vast majority of these EDs care for fewer than 14-15 children a day.

With such low pediatric volume, “there will never be pediatric emergency medicine physicians in the rural hospitals in [our] health care system,” said Kathleen M. Brown, MD, medical director for quality and safety of the Emergency Medicine and Trauma Center at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Redistribution “is not a practical solution, and we’ve known that for a long time,” said Dr. Brown, past chairperson of the American College of Emergency Physicians’ pediatric emergency medicine committee. “That’s why national efforts have focused on better preparing the general emergency department and making sure the hospital workforce is ready to take care of children ... to manage and stabilize [them] and recognize when they need more definitive care.”

Continuing efforts to increase “pediatric readiness” in general EDs is one of the recommendations issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics, ACEP, and Emergency Nurses Association in its most recent joint policy statement on emergency care for children, published in May (Pediatrics 2021;147[5]:e2021050787). A 2018 joint policy statement detailed the resources – medications, equipment, policies, and education – necessary for EDs to provide effective pediatric care (Pediatrics 2018;142[5]:e20182459).

There is some evidence that pediatric readiness has improved and that EDs with higher readiness scores may have better pediatric outcomes and lower mortality, said Dr. Brown, a coauthor of both policy statements. (One study cited in the 2018 policy statement, for example, found that children with extremity immobilization and a pain score of 5 or greater had faster management of their pain and decreased exposure to radiation when they were treated in a better-prepared facility than in a facility with less readiness.)

Yet many hospitals still do not have designated pediatric emergency care coordinators (PECCs) – roles that are widely believed to be central to pediatric readiness. PECCs (physicians and nurses) were recommended in 2006 by the then-Institute of Medicine and have been advocated by the AAP, ACEP, and other organizations.

According to 2013 data from the National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP), launched that year by the AAP, ACEP, ENA, and the federal Emergency Medical Services for Children program of the Health Resources and Services Administration, at least 15% of EDs lacked at least 1 piece of recommended equipment, and 81% reported barriers to pediatric emergency care guidelines. The NPRP is currently conducting an updated assessment, Dr. Brown said.

Some experts have proposed a different kind of solution – one in which American Board of Pediatrics–certified pediatric EM physicians would care for selective adult patients with common disease patterns who present to rural EDs, in addition to children. They might provide direct patient care across several hospitals in a region, while also addressing quality improvement and assisting EPs and other providers in the region on pediatric care issues.

The proposal, published in May 2020, comes from the 13-member special subcommittee of the ACEP committee on PEM that was tasked with exploring strategies to improve access to emergency pediatric expertise and disaster preparedness in all settings. The proposal was endorsed by the ACEP board of directors, said Jim Homme, MD, a coauthor of the paper (JACEP Open 2020;1:1520-6.)

“We’re saying, look at the ped-trained pediatric emergency provider more broadly. They can actually successfully care for a broader patient population and make it financially feasible ... [for that physician] to be a part of the system,” said Dr. Homme, program director of the emergency medicine residency at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Rochester, Minn.

“The benefit would be not only having the expertise to see children, but to train up other individuals in the institution, and be advocates for the care of children,” he said.

“We’re not saying we want a pediatrics-trained EM physician in every site so that every child would be seen by one – that’s not the goal,” Dr. Homme said. “The goal is to distribute them more broadly than they currently are, and in doing so, make available the other benefits besides direct patient care.”

Most of the physicians in the United States who identify as pediatric EM physicians have completed either a pediatrics or EM residency, followed by a pediatric EM fellowship. It is much more common to have primary training in pediatrics than in EM, said Dr. Homme and Dr. Bennett. A small number of physicians, like Dr. Homme, are dually trained in pediatrics and EM through the completion of two residencies. Dr. Bennett’s workforce study used the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile database and identified 2,403 clinically active pediatric EPs – 5% of all clinically active emergency physicians. Those practicing in rural areas had a median age of 59, compared with a median age of 46 in urban areas. More than half of the pediatric EPs – 68% – reported having pediatric EM board certification.

Three states – Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming – had no pediatric EMs at all, Dr. Bennett noted.

Readiness in rural Oregon, New England

Torree McGowan, MD, an emergency physician with the St. Charles Health System in Oregon, works in small critical access hospitals in the rural towns of Madras and Prineville, each several hours by ground to the nearest pediatric hospital. She said she feels well equipped to care for children through her training (a rotation in a pediatric ICU and several months working in pediatric EDs) and through her ongoing work with pediatric patients. Children and adolescents comprise about 20%-30% of her volume.

She sees more pediatric illness – children with respiratory syncytial virus who need respiratory support, for instance, and children with severe asthma or diabetic ketoacidosis – than pediatric trauma. When she faces questions, uncertainties, or wants confirmation of a decision, she consults by phone with pediatric subspecialists.

“I don’t take care of kids on vasopressor drips on a regular basis [for instance],” said Dr. McGowan, who sits on ACEP’s disaster preparedness committee and is an Air Force veteran. “But I know the basics and can phone a colleague to be sure I’m doing it correctly. The ability to outreach is there.”

Telemedicine is valuable, she said, but there may also be value in working alongside a pediatric EM physician. One of her EP colleagues is fellowship-trained in ultrasonography and “leads us in training and quality control,” Dr. McGowan said. “And if she’s on shift with you she’ll teach you all about ultrasound. There’s probably utility in having a pediatric EP who does that as well. But incentivizing that and taking them away from the pediatric hospital is a paradigm shift.”

Either way, she said, “being able to bring that expertise out of urban centers, whether it’s to a hospital group like ours or whether it’s by telemedicine, is really, really helpful.”

Her group does not have official PECCs, but the joint policy statements by AAP/ACEP/ENA on pediatric readiness and the “whole pediatric readiness effort’ have been valuable in “driving conversations” with administrators about needs such as purchasing pediatric-sized video laryngoscope blades and other equipment needed for pediatric emergencies, however infrequently they may occur, Dr. McGowan said.

In New England, researchers leading a grassroots regional intervention to establish a PECC in every ED in the region have reported an increased prevalence of “pediatric champions” from less than 30% 5 years ago to greater than 90% in 2019, investigators have reported (Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002456).

The initiative involved individual outreach to leaders of each ED – largely through phone and e-mail appeals – and collaboration among the State Emergency Medical Services for Children agencies and ACEP and ENA state chapters. The researchers are currently investigating the direct impact of PECCs on patient outcomes.

More on regionalization of ped-trained EPs

Dr. Bennett sees telemedicine as a primary part of improving pediatric emergency care. “I think that’s where things are going to go in pediatric emergency medicine,” he said, especially in the wake of COVID-19: “I don’t see how it’s not going to become much more common.”

Dr. Homme maintains that a broader integration of ABP-certified pediatric EM physicians into underserved regions would advance ED preparedness in a way that telemedicine, or even the appointment of PECCs, does not, said Dr. Homme.

Institutions would need to acknowledge that many of the current restrictions on pediatric EM physicians’ scope of practice are based on arbitrary age cut-offs, and their leaders would need to expand hospital-defined privileges to better align with training and capabilities, he said. Local credentialing provisions and other policies would also need to be adjusted.

Pediatric EM physicians spend at least 4 months of their graduate EM training in an adult ED, and there is significant overlap in the core competencies and the procedures considered essential for practice between pediatric EM fellowship programs and EM programs, Dr. Homme and his coauthors wrote in their proposal. “The pandemic really reinforced this concept,” Dr. Homme said. “As the number of patients in pediatric EDs plummeted, many of the ped-trained providers had to pivot and help care for adults. ... It worked great.”

The broader integration of pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians fits well, he believes, with current workforce dynamics. “There aren’t enough individuals coming out of an EM background and doing that subspecialty training to have any hope that they’d be able to cover these underserved areas,” he said. “And the academic pediatric workforce is getting kind of saturated. So having additional employment opportunities would be great.”

Dr. Homme pursued an EM residency after pediatrics training (rather than a pediatric EM fellowship) because he did not want to be limited geographically and because, while he wanted to focus on children, he also “wanted to be available to a larger population.”

He believes that some pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians would choose rural practice options, and hopes that the proposal will gain traction. Some EPs will be opposed, he said, and some pediatrics-trained EPs will not interested, “but if we can find people open to the idea on both sides, I think we can really move the needle in the direction we’re trying to, which is to disseminate an area of expertise into areas that just don’t have it.”

A new physician workforce study documents that almost all clinically active pediatric emergency physicians in the United States – 99% of them – work in urban areas, and that those who do practice in rural areas are significantly older and closer to retirement age.

The portrait of approximately 2,400 self-identified pediatric emergency medicine (EM) physicians may be unsurprising given the overall propensity of physicians – including board-certified general emergency physicians – to practice in urban areas. Even so, it underscores a decades-long concern that many children do not have access to optimal pediatric emergency care.

And the findings highlight the need, the authors say, to keep pressing to improve emergency care for a population of children with “a mortality rate that is already higher than that of its suburban and urban peers (JAMA Network Open 2021;4[5]:e2110084).”

Emergent care of pediatric patients is well within the scope of practice for physicians with training and board certification in general EM, but children and adolescents have different clinical needs and “there are high-stakes scenarios [in children] that we [as emergency physicians] don’t get exposed to as often because we’re not in a children’s hospital or we just don’t have that additional level of training,” said Christopher L. Bennett, MD, MA, of the department of emergency medicine at Stanford University and lead author of the study.

Researchers have documented that some emergency physicians have some discomfort in caring for very ill pediatric patients, he and his coauthors wrote.

Children account for more than 20% of annual ED visits, and most children who seek emergency care in the United States – upwards of 80% – present to general emergency departments. Yet the vast majority of these EDs care for fewer than 14-15 children a day.

With such low pediatric volume, “there will never be pediatric emergency medicine physicians in the rural hospitals in [our] health care system,” said Kathleen M. Brown, MD, medical director for quality and safety of the Emergency Medicine and Trauma Center at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Redistribution “is not a practical solution, and we’ve known that for a long time,” said Dr. Brown, past chairperson of the American College of Emergency Physicians’ pediatric emergency medicine committee. “That’s why national efforts have focused on better preparing the general emergency department and making sure the hospital workforce is ready to take care of children ... to manage and stabilize [them] and recognize when they need more definitive care.”

Continuing efforts to increase “pediatric readiness” in general EDs is one of the recommendations issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics, ACEP, and Emergency Nurses Association in its most recent joint policy statement on emergency care for children, published in May (Pediatrics 2021;147[5]:e2021050787). A 2018 joint policy statement detailed the resources – medications, equipment, policies, and education – necessary for EDs to provide effective pediatric care (Pediatrics 2018;142[5]:e20182459).

There is some evidence that pediatric readiness has improved and that EDs with higher readiness scores may have better pediatric outcomes and lower mortality, said Dr. Brown, a coauthor of both policy statements. (One study cited in the 2018 policy statement, for example, found that children with extremity immobilization and a pain score of 5 or greater had faster management of their pain and decreased exposure to radiation when they were treated in a better-prepared facility than in a facility with less readiness.)

Yet many hospitals still do not have designated pediatric emergency care coordinators (PECCs) – roles that are widely believed to be central to pediatric readiness. PECCs (physicians and nurses) were recommended in 2006 by the then-Institute of Medicine and have been advocated by the AAP, ACEP, and other organizations.

According to 2013 data from the National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP), launched that year by the AAP, ACEP, ENA, and the federal Emergency Medical Services for Children program of the Health Resources and Services Administration, at least 15% of EDs lacked at least 1 piece of recommended equipment, and 81% reported barriers to pediatric emergency care guidelines. The NPRP is currently conducting an updated assessment, Dr. Brown said.

Some experts have proposed a different kind of solution – one in which American Board of Pediatrics–certified pediatric EM physicians would care for selective adult patients with common disease patterns who present to rural EDs, in addition to children. They might provide direct patient care across several hospitals in a region, while also addressing quality improvement and assisting EPs and other providers in the region on pediatric care issues.

The proposal, published in May 2020, comes from the 13-member special subcommittee of the ACEP committee on PEM that was tasked with exploring strategies to improve access to emergency pediatric expertise and disaster preparedness in all settings. The proposal was endorsed by the ACEP board of directors, said Jim Homme, MD, a coauthor of the paper (JACEP Open 2020;1:1520-6.)

“We’re saying, look at the ped-trained pediatric emergency provider more broadly. They can actually successfully care for a broader patient population and make it financially feasible ... [for that physician] to be a part of the system,” said Dr. Homme, program director of the emergency medicine residency at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Rochester, Minn.

“The benefit would be not only having the expertise to see children, but to train up other individuals in the institution, and be advocates for the care of children,” he said.

“We’re not saying we want a pediatrics-trained EM physician in every site so that every child would be seen by one – that’s not the goal,” Dr. Homme said. “The goal is to distribute them more broadly than they currently are, and in doing so, make available the other benefits besides direct patient care.”

Most of the physicians in the United States who identify as pediatric EM physicians have completed either a pediatrics or EM residency, followed by a pediatric EM fellowship. It is much more common to have primary training in pediatrics than in EM, said Dr. Homme and Dr. Bennett. A small number of physicians, like Dr. Homme, are dually trained in pediatrics and EM through the completion of two residencies. Dr. Bennett’s workforce study used the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile database and identified 2,403 clinically active pediatric EPs – 5% of all clinically active emergency physicians. Those practicing in rural areas had a median age of 59, compared with a median age of 46 in urban areas. More than half of the pediatric EPs – 68% – reported having pediatric EM board certification.

Three states – Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming – had no pediatric EMs at all, Dr. Bennett noted.

Readiness in rural Oregon, New England

Torree McGowan, MD, an emergency physician with the St. Charles Health System in Oregon, works in small critical access hospitals in the rural towns of Madras and Prineville, each several hours by ground to the nearest pediatric hospital. She said she feels well equipped to care for children through her training (a rotation in a pediatric ICU and several months working in pediatric EDs) and through her ongoing work with pediatric patients. Children and adolescents comprise about 20%-30% of her volume.

She sees more pediatric illness – children with respiratory syncytial virus who need respiratory support, for instance, and children with severe asthma or diabetic ketoacidosis – than pediatric trauma. When she faces questions, uncertainties, or wants confirmation of a decision, she consults by phone with pediatric subspecialists.

“I don’t take care of kids on vasopressor drips on a regular basis [for instance],” said Dr. McGowan, who sits on ACEP’s disaster preparedness committee and is an Air Force veteran. “But I know the basics and can phone a colleague to be sure I’m doing it correctly. The ability to outreach is there.”

Telemedicine is valuable, she said, but there may also be value in working alongside a pediatric EM physician. One of her EP colleagues is fellowship-trained in ultrasonography and “leads us in training and quality control,” Dr. McGowan said. “And if she’s on shift with you she’ll teach you all about ultrasound. There’s probably utility in having a pediatric EP who does that as well. But incentivizing that and taking them away from the pediatric hospital is a paradigm shift.”

Either way, she said, “being able to bring that expertise out of urban centers, whether it’s to a hospital group like ours or whether it’s by telemedicine, is really, really helpful.”

Her group does not have official PECCs, but the joint policy statements by AAP/ACEP/ENA on pediatric readiness and the “whole pediatric readiness effort’ have been valuable in “driving conversations” with administrators about needs such as purchasing pediatric-sized video laryngoscope blades and other equipment needed for pediatric emergencies, however infrequently they may occur, Dr. McGowan said.

In New England, researchers leading a grassroots regional intervention to establish a PECC in every ED in the region have reported an increased prevalence of “pediatric champions” from less than 30% 5 years ago to greater than 90% in 2019, investigators have reported (Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002456).

The initiative involved individual outreach to leaders of each ED – largely through phone and e-mail appeals – and collaboration among the State Emergency Medical Services for Children agencies and ACEP and ENA state chapters. The researchers are currently investigating the direct impact of PECCs on patient outcomes.

More on regionalization of ped-trained EPs

Dr. Bennett sees telemedicine as a primary part of improving pediatric emergency care. “I think that’s where things are going to go in pediatric emergency medicine,” he said, especially in the wake of COVID-19: “I don’t see how it’s not going to become much more common.”

Dr. Homme maintains that a broader integration of ABP-certified pediatric EM physicians into underserved regions would advance ED preparedness in a way that telemedicine, or even the appointment of PECCs, does not, said Dr. Homme.

Institutions would need to acknowledge that many of the current restrictions on pediatric EM physicians’ scope of practice are based on arbitrary age cut-offs, and their leaders would need to expand hospital-defined privileges to better align with training and capabilities, he said. Local credentialing provisions and other policies would also need to be adjusted.

Pediatric EM physicians spend at least 4 months of their graduate EM training in an adult ED, and there is significant overlap in the core competencies and the procedures considered essential for practice between pediatric EM fellowship programs and EM programs, Dr. Homme and his coauthors wrote in their proposal. “The pandemic really reinforced this concept,” Dr. Homme said. “As the number of patients in pediatric EDs plummeted, many of the ped-trained providers had to pivot and help care for adults. ... It worked great.”

The broader integration of pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians fits well, he believes, with current workforce dynamics. “There aren’t enough individuals coming out of an EM background and doing that subspecialty training to have any hope that they’d be able to cover these underserved areas,” he said. “And the academic pediatric workforce is getting kind of saturated. So having additional employment opportunities would be great.”

Dr. Homme pursued an EM residency after pediatrics training (rather than a pediatric EM fellowship) because he did not want to be limited geographically and because, while he wanted to focus on children, he also “wanted to be available to a larger population.”

He believes that some pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians would choose rural practice options, and hopes that the proposal will gain traction. Some EPs will be opposed, he said, and some pediatrics-trained EPs will not interested, “but if we can find people open to the idea on both sides, I think we can really move the needle in the direction we’re trying to, which is to disseminate an area of expertise into areas that just don’t have it.”

A new physician workforce study documents that almost all clinically active pediatric emergency physicians in the United States – 99% of them – work in urban areas, and that those who do practice in rural areas are significantly older and closer to retirement age.

The portrait of approximately 2,400 self-identified pediatric emergency medicine (EM) physicians may be unsurprising given the overall propensity of physicians – including board-certified general emergency physicians – to practice in urban areas. Even so, it underscores a decades-long concern that many children do not have access to optimal pediatric emergency care.

And the findings highlight the need, the authors say, to keep pressing to improve emergency care for a population of children with “a mortality rate that is already higher than that of its suburban and urban peers (JAMA Network Open 2021;4[5]:e2110084).”

Emergent care of pediatric patients is well within the scope of practice for physicians with training and board certification in general EM, but children and adolescents have different clinical needs and “there are high-stakes scenarios [in children] that we [as emergency physicians] don’t get exposed to as often because we’re not in a children’s hospital or we just don’t have that additional level of training,” said Christopher L. Bennett, MD, MA, of the department of emergency medicine at Stanford University and lead author of the study.

Researchers have documented that some emergency physicians have some discomfort in caring for very ill pediatric patients, he and his coauthors wrote.

Children account for more than 20% of annual ED visits, and most children who seek emergency care in the United States – upwards of 80% – present to general emergency departments. Yet the vast majority of these EDs care for fewer than 14-15 children a day.

With such low pediatric volume, “there will never be pediatric emergency medicine physicians in the rural hospitals in [our] health care system,” said Kathleen M. Brown, MD, medical director for quality and safety of the Emergency Medicine and Trauma Center at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Redistribution “is not a practical solution, and we’ve known that for a long time,” said Dr. Brown, past chairperson of the American College of Emergency Physicians’ pediatric emergency medicine committee. “That’s why national efforts have focused on better preparing the general emergency department and making sure the hospital workforce is ready to take care of children ... to manage and stabilize [them] and recognize when they need more definitive care.”

Continuing efforts to increase “pediatric readiness” in general EDs is one of the recommendations issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics, ACEP, and Emergency Nurses Association in its most recent joint policy statement on emergency care for children, published in May (Pediatrics 2021;147[5]:e2021050787). A 2018 joint policy statement detailed the resources – medications, equipment, policies, and education – necessary for EDs to provide effective pediatric care (Pediatrics 2018;142[5]:e20182459).

There is some evidence that pediatric readiness has improved and that EDs with higher readiness scores may have better pediatric outcomes and lower mortality, said Dr. Brown, a coauthor of both policy statements. (One study cited in the 2018 policy statement, for example, found that children with extremity immobilization and a pain score of 5 or greater had faster management of their pain and decreased exposure to radiation when they were treated in a better-prepared facility than in a facility with less readiness.)

Yet many hospitals still do not have designated pediatric emergency care coordinators (PECCs) – roles that are widely believed to be central to pediatric readiness. PECCs (physicians and nurses) were recommended in 2006 by the then-Institute of Medicine and have been advocated by the AAP, ACEP, and other organizations.

According to 2013 data from the National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP), launched that year by the AAP, ACEP, ENA, and the federal Emergency Medical Services for Children program of the Health Resources and Services Administration, at least 15% of EDs lacked at least 1 piece of recommended equipment, and 81% reported barriers to pediatric emergency care guidelines. The NPRP is currently conducting an updated assessment, Dr. Brown said.

Some experts have proposed a different kind of solution – one in which American Board of Pediatrics–certified pediatric EM physicians would care for selective adult patients with common disease patterns who present to rural EDs, in addition to children. They might provide direct patient care across several hospitals in a region, while also addressing quality improvement and assisting EPs and other providers in the region on pediatric care issues.

The proposal, published in May 2020, comes from the 13-member special subcommittee of the ACEP committee on PEM that was tasked with exploring strategies to improve access to emergency pediatric expertise and disaster preparedness in all settings. The proposal was endorsed by the ACEP board of directors, said Jim Homme, MD, a coauthor of the paper (JACEP Open 2020;1:1520-6.)

“We’re saying, look at the ped-trained pediatric emergency provider more broadly. They can actually successfully care for a broader patient population and make it financially feasible ... [for that physician] to be a part of the system,” said Dr. Homme, program director of the emergency medicine residency at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Rochester, Minn.

“The benefit would be not only having the expertise to see children, but to train up other individuals in the institution, and be advocates for the care of children,” he said.

“We’re not saying we want a pediatrics-trained EM physician in every site so that every child would be seen by one – that’s not the goal,” Dr. Homme said. “The goal is to distribute them more broadly than they currently are, and in doing so, make available the other benefits besides direct patient care.”

Most of the physicians in the United States who identify as pediatric EM physicians have completed either a pediatrics or EM residency, followed by a pediatric EM fellowship. It is much more common to have primary training in pediatrics than in EM, said Dr. Homme and Dr. Bennett. A small number of physicians, like Dr. Homme, are dually trained in pediatrics and EM through the completion of two residencies. Dr. Bennett’s workforce study used the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile database and identified 2,403 clinically active pediatric EPs – 5% of all clinically active emergency physicians. Those practicing in rural areas had a median age of 59, compared with a median age of 46 in urban areas. More than half of the pediatric EPs – 68% – reported having pediatric EM board certification.

Three states – Montana, South Dakota, and Wyoming – had no pediatric EMs at all, Dr. Bennett noted.

Readiness in rural Oregon, New England

Torree McGowan, MD, an emergency physician with the St. Charles Health System in Oregon, works in small critical access hospitals in the rural towns of Madras and Prineville, each several hours by ground to the nearest pediatric hospital. She said she feels well equipped to care for children through her training (a rotation in a pediatric ICU and several months working in pediatric EDs) and through her ongoing work with pediatric patients. Children and adolescents comprise about 20%-30% of her volume.

She sees more pediatric illness – children with respiratory syncytial virus who need respiratory support, for instance, and children with severe asthma or diabetic ketoacidosis – than pediatric trauma. When she faces questions, uncertainties, or wants confirmation of a decision, she consults by phone with pediatric subspecialists.

“I don’t take care of kids on vasopressor drips on a regular basis [for instance],” said Dr. McGowan, who sits on ACEP’s disaster preparedness committee and is an Air Force veteran. “But I know the basics and can phone a colleague to be sure I’m doing it correctly. The ability to outreach is there.”

Telemedicine is valuable, she said, but there may also be value in working alongside a pediatric EM physician. One of her EP colleagues is fellowship-trained in ultrasonography and “leads us in training and quality control,” Dr. McGowan said. “And if she’s on shift with you she’ll teach you all about ultrasound. There’s probably utility in having a pediatric EP who does that as well. But incentivizing that and taking them away from the pediatric hospital is a paradigm shift.”

Either way, she said, “being able to bring that expertise out of urban centers, whether it’s to a hospital group like ours or whether it’s by telemedicine, is really, really helpful.”

Her group does not have official PECCs, but the joint policy statements by AAP/ACEP/ENA on pediatric readiness and the “whole pediatric readiness effort’ have been valuable in “driving conversations” with administrators about needs such as purchasing pediatric-sized video laryngoscope blades and other equipment needed for pediatric emergencies, however infrequently they may occur, Dr. McGowan said.

In New England, researchers leading a grassroots regional intervention to establish a PECC in every ED in the region have reported an increased prevalence of “pediatric champions” from less than 30% 5 years ago to greater than 90% in 2019, investigators have reported (Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002456).

The initiative involved individual outreach to leaders of each ED – largely through phone and e-mail appeals – and collaboration among the State Emergency Medical Services for Children agencies and ACEP and ENA state chapters. The researchers are currently investigating the direct impact of PECCs on patient outcomes.

More on regionalization of ped-trained EPs

Dr. Bennett sees telemedicine as a primary part of improving pediatric emergency care. “I think that’s where things are going to go in pediatric emergency medicine,” he said, especially in the wake of COVID-19: “I don’t see how it’s not going to become much more common.”

Dr. Homme maintains that a broader integration of ABP-certified pediatric EM physicians into underserved regions would advance ED preparedness in a way that telemedicine, or even the appointment of PECCs, does not, said Dr. Homme.

Institutions would need to acknowledge that many of the current restrictions on pediatric EM physicians’ scope of practice are based on arbitrary age cut-offs, and their leaders would need to expand hospital-defined privileges to better align with training and capabilities, he said. Local credentialing provisions and other policies would also need to be adjusted.

Pediatric EM physicians spend at least 4 months of their graduate EM training in an adult ED, and there is significant overlap in the core competencies and the procedures considered essential for practice between pediatric EM fellowship programs and EM programs, Dr. Homme and his coauthors wrote in their proposal. “The pandemic really reinforced this concept,” Dr. Homme said. “As the number of patients in pediatric EDs plummeted, many of the ped-trained providers had to pivot and help care for adults. ... It worked great.”

The broader integration of pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians fits well, he believes, with current workforce dynamics. “There aren’t enough individuals coming out of an EM background and doing that subspecialty training to have any hope that they’d be able to cover these underserved areas,” he said. “And the academic pediatric workforce is getting kind of saturated. So having additional employment opportunities would be great.”

Dr. Homme pursued an EM residency after pediatrics training (rather than a pediatric EM fellowship) because he did not want to be limited geographically and because, while he wanted to focus on children, he also “wanted to be available to a larger population.”

He believes that some pediatrics-trained pediatric EM physicians would choose rural practice options, and hopes that the proposal will gain traction. Some EPs will be opposed, he said, and some pediatrics-trained EPs will not interested, “but if we can find people open to the idea on both sides, I think we can really move the needle in the direction we’re trying to, which is to disseminate an area of expertise into areas that just don’t have it.”

Cortical thinning in adolescence ‘definitively’ tied to subsequent psychosis

Subtle differences in brain morphometric features present in adolescence were associated with the subsequent development of psychosis in what is believed to be the largest neuroimaging investigation to date involving people at clinical high risk (CHR).

Investigators found widespread lower cortical thickness (CT) in individuals at CHR, consistent with previously reported CT differences in individuals with an established psychotic disorder.

“This is the first study to definitively show that there are subtle, widespread structural brain differences in high-risk youth before they develop psychosis,” study investigator Maria Jalbrzikowski, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings also suggest that there are developmental periods during which certain brain abnormalities may be more apparent, “highlighting the need to consider developmental period when developing objective, biological risk factors for early intervention in psychosis,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said.

The study was published online May 5 in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Sobering’ results

The findings are based on pooled structural MRI scans from 3,169 individuals recruited at 31 international sites participating in the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) Clinical High Risk for Psychosis Working Group.

Forty-five percent of the participants were female; the mean age was 21 years (range, 9.5 to 39.9 years).

The cohort included 1,792 individuals at CHR for psychosis and 1,377 healthy control persons. Using longitudinal clinical information, the researchers identified 253 individuals at CHR who went on to develop a psychotic disorder (CHR-PS+) and 1,234 at CHR who did not develop a psychotic disorder (CHR-PS-). For the remaining 305 individuals at CHR, follow-up data were unavailable.

Compared with healthy control persons, individuals at CHR had widespread lower CT measures but not lower surface area or subcortical volume. Lower CT measures in the fusiform, superior temporal, and paracentral regions were associated with conversion to psychosis.

The pattern of differences in cortical thickness in those in the CHR-PS+ group mirrored patterns seen in people with schizophrenia and in people with 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome who developed a psychotic disorder.

The researchers note that although all individuals experience cortical thinning as they move into adulthood, in their study, cortical thinning was already present in participants aged 12 to 16 years who developed psychosis.

“We don’t yet know exactly what this means, but adolescence is a critical time in a child’s life – it’s a time of opportunity to take risks and explore, but also a period of vulnerability,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said in a news release.

“We could be seeing the result of something that happened even earlier in brain development but only begins to influence behavior during this developmental stage,” she noted.

This analysis represents the largest-ever pooling of brain scans in children and young adults who were determined by psychiatric assessment to be at high risk of developing psychosis.

“These results were, in a sense, sobering. On the one hand, our dataset includes 600% more high-risk youth who developed psychosis than any existing study, allowing us to see statistically significant results in brain structure.”

“But the variance between whether or not a high-risk youth develops psychosis is so small that it would be impossible to see a difference at the individual level,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said.

More work is needed in order for the findings to be translated into clinical care, she added.

Definitive findings

Commenting on the findings for an interview, Russell Margolis, MD, clinical director, Johns Hopkins Schizophrenia Center, said that “it’s not so much that the findings are novel but rather that they’re fairly definitive in that this is by far the largest study of its kind looking at this particular question, and that gives it power. The problem with imaging studies has often been inconsistent results from study to study because of small sample size.”

“In order to see these differences in a robust way, you need a large sample size, meaning that for any one individual, this kind of structural imaging is not going to add much to the prediction of whether someone will eventually develop a schizophrenia-like illness,” said Dr. Margolis, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

From a clinical standpoint,

“The predominant hypothesis in the field is that early developmental abnormalities are the root cause of schizophrenia and related disorders, and this study is consistent with that, particularly the age-related differences, which are suggestive of neurodevelopmental abnormalities preceding the development of overt symptoms, which many other findings have also suggested,” Dr. Margolis said.

“Abnormalities in cortical thickness could be from a number of different neurobiological processes, and research into those processes are worth investigating,” he added.

The researchers received support from numerous funders, all of which are listed in the original article, along with author disclosures for ENIGMA working group members. Dr. Margolis has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subtle differences in brain morphometric features present in adolescence were associated with the subsequent development of psychosis in what is believed to be the largest neuroimaging investigation to date involving people at clinical high risk (CHR).

Investigators found widespread lower cortical thickness (CT) in individuals at CHR, consistent with previously reported CT differences in individuals with an established psychotic disorder.

“This is the first study to definitively show that there are subtle, widespread structural brain differences in high-risk youth before they develop psychosis,” study investigator Maria Jalbrzikowski, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said in an interview.

The findings also suggest that there are developmental periods during which certain brain abnormalities may be more apparent, “highlighting the need to consider developmental period when developing objective, biological risk factors for early intervention in psychosis,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said.

The study was published online May 5 in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Sobering’ results

The findings are based on pooled structural MRI scans from 3,169 individuals recruited at 31 international sites participating in the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) Clinical High Risk for Psychosis Working Group.

Forty-five percent of the participants were female; the mean age was 21 years (range, 9.5 to 39.9 years).

The cohort included 1,792 individuals at CHR for psychosis and 1,377 healthy control persons. Using longitudinal clinical information, the researchers identified 253 individuals at CHR who went on to develop a psychotic disorder (CHR-PS+) and 1,234 at CHR who did not develop a psychotic disorder (CHR-PS-). For the remaining 305 individuals at CHR, follow-up data were unavailable.

Compared with healthy control persons, individuals at CHR had widespread lower CT measures but not lower surface area or subcortical volume. Lower CT measures in the fusiform, superior temporal, and paracentral regions were associated with conversion to psychosis.

The pattern of differences in cortical thickness in those in the CHR-PS+ group mirrored patterns seen in people with schizophrenia and in people with 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome who developed a psychotic disorder.

The researchers note that although all individuals experience cortical thinning as they move into adulthood, in their study, cortical thinning was already present in participants aged 12 to 16 years who developed psychosis.

“We don’t yet know exactly what this means, but adolescence is a critical time in a child’s life – it’s a time of opportunity to take risks and explore, but also a period of vulnerability,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said in a news release.

“We could be seeing the result of something that happened even earlier in brain development but only begins to influence behavior during this developmental stage,” she noted.

This analysis represents the largest-ever pooling of brain scans in children and young adults who were determined by psychiatric assessment to be at high risk of developing psychosis.

“These results were, in a sense, sobering. On the one hand, our dataset includes 600% more high-risk youth who developed psychosis than any existing study, allowing us to see statistically significant results in brain structure.”

“But the variance between whether or not a high-risk youth develops psychosis is so small that it would be impossible to see a difference at the individual level,” Dr. Jalbrzikowski said.