User login

What is the proper workup of a patient with hypertension?

How extensive a workup does a patient with high blood pressure need?

On one hand, we would not want to start therapy on the basis of a single elevated reading, as blood pressure fluctuates considerably during the day, and even experienced physicians often make errors in taking blood pressure that tend to falsely elevate the patient’s readings. Similarly, we would not want to miss the diagnosis of a potentially curable cause of hypertension or of a condition that increases a patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease. But considering that nearly one-third of adults in the United States have hypertension and that another one-fourth have prehypertension (formerly called high-normal blood pressure),1 if we were to launch an intensive workup for every patient with high blood pressure, the cost and effort would be enormous.

Fortunately, for most patients, it is enough to measure blood pressure accurately and repeatedly, perform a focused history and physical examination, and obtain the results of a few basic laboratory tests and an electrocardiogram, with additional tests in special cases.

In this review we address four fundamental questions in the evaluation of patients with a high blood pressure reading, and how to answer them.

ANSWERING FOUR QUESTIONS

The goal of the hypertension evaluation is to answer four questions:

- Does the patient have sustained hypertension? And if so—

- Is the hypertension primary or secondary?

- Does the patient have other cardiovascular risk factors?

- Does he or she have evidence of target organ damage?

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE SUSTAINED HYPERTENSION?

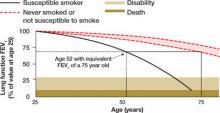

It is important to measure blood pressure accurately, for several reasons. A diagnosis of hypertension has a measurable impact on the patient’s quality of life.2 Furthermore, we want to avoid undertaking a full evaluation of hypertension if the patient doesn’t actually have high blood pressure, ie, systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. However, many people have blood pressures in the prehypertensive range (ie, 120–139 mm Hg systolic; 80–89 mm Hg diastolic). Many people in this latter group can expect to develop hypertension in time, as the prevalence of hypertension increases steadily with age unless effective preventive measures are implemented, such as losing weight, exercising regularly, and avoiding excessive consumption of sodium and alcohol.

The best position to use is sitting, as the Framingham Heart Study and most randomized clinical trials that established the value of treating hypertension used this position for diagnosis and follow-up.6

Proper patient positioning, the correct cuff size, calibrated equipment, and good inflation and deflation technique will yield the best assessment of blood pressure levels. But even if your technique is perfect, blood pressure is a dynamic vital sign, so it is necessary to repeat the measurement, average the values for any particular day, and keep in mind that the pressure is higher (or lower) on some days than on others, so that the running average is more important than individual readings. This leads to two final points about blood pressure measurement:

- Take it right, at least two times on any occasion

- Take it on at least two (preferably three) separate days.

Following up on blood pressure

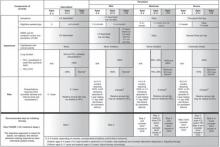

After measuring the blood pressure, it is necessary to plan for follow-up readings, guided by both the blood pressure levels (Table 2) and your clinical judgment.

If the systolic and diastolic blood pressures fall into different categories, you should follow the recommendations for the shorter follow-up time.

IS THE HYPERTENSION PRIMARY OR SECONDARY?

Most patients with hypertension have primary (“essential”) hypertension and are likely to remain hypertensive for life. However, some have secondary hypertension, ie, high blood pressure due to an identifiable cause. Some of these conditions (and the hypertension that they cause) can be cured. For example, pheochromocytoma can be cured if found and removed. Other causes of secondary hypertension, such as parenchymal renal disease, are infrequently cured, and the goal is usually to control the blood pressure with drugs.

The sudden onset of severe hypertension in a patient previously known to have had normal blood pressure raises the suspicion of a secondary form of hypertension, as does the onset of hypertension in a young person (< 25 years) or an older person (> 55 years). However, these ages are arbitrary; with the increasing body mass index in young people, essential hypertension is now more commonly diagnosed in the third decade. And since systolic pressure increases throughout life, we can expect many older patients to develop essential hypertension.7 Indeed, current guidelines are urging us to pay more attention to systolic pressure than in the past.

WHAT IS THE PATIENT’S CARDIOVASCULAR RISK?

The relationship between blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease is linear, continuous, and independent of (though additive to) other risk factors.1 For people 40 to 70 years old, each increment of either 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease across the entire range from 115/75 to 185/115 mm Hg.1 If the patient smokes or has elevated cholesterol, other cardiovascular risk factors, or the metabolic syndrome, the risk is even higher.8

The usual goal of antihypertensive treatment is systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg and diastolic pressure less than 90 mm Hg. However, the target is lower—less than 130/80 mm Hg—for those with diabetes9 or target organ damage such as heart failure or renal disease.1,10 Thus, it is important to try to detect these conditions in the evaluation of the hypertensive patient.

Another reason it is important is that reducing such risk sometimes calls for using (or avoiding) antihypertensive drugs that are likely to alter these factors. For example, the use of beta-blockers in patients with a low level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) can lower HDL-C further.11

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE TARGET ORGAN DAMAGE?

Target organ damage is very important to detect because it changes the goal of treatment from primary prevention of adverse target organ outcomes into the more challenging realm of secondary prevention. For example, if a patient has had a stroke, his or her chance of having another stroke in the next 5 years is about 20%. This is much higher than the risk in an average hypertensive patient without such a history. For such patients, the current guidelines1 recommend the combination of a diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, a combination shown to reduce the risk of a second stroke.12 Thus, we need to discover whether the patient had a stroke in the first place.

HISTORY

- The duration (if known) and severity of the hypertension

- The degree of blood pressure fluctuation

- Concomitant medical conditions, especially cardiovascular or renal problems

- Dietary habits

- Alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use

- Level of physical activity

- A family history of hypertension, renal disease, cardiovascular problems, or diabetes mellitus

- Past medications, with particular attention to their side effects and their efficacy in controlling blood pressure

- Current medications, including over-the-counter preparations. One reason: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin can decrease the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs, presumably through mechanisms that inhibit the effects of vasodilatory and natriuretic prostaglandins and potentiate those of angiotensin II.13

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination starts with measurement of height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure—in both arms and the leg if coarctation of the aorta is suspected. Measurements with the patient supine, sitting, and standing are usually taken at the first visit, though such an approach is more suited to a hypertension specialty clinic than a primary care setting, in which time constraints usually limit the blood pressure readings to two or three seated values. Most prospective data on the benefits of hypertension treatment are based on a seated blood pressure, so we favor that measurement for follow-up.

Special attention in the physical examination is directed to:

The retina (to assess the vascular impact of the high blood pressure). Look for arteriolar narrowing (grade 1), arteriovenous compression (grade 2), hemorrhages or exudates (grade 3), and papilledema.2 Such findings not only relate to severity (higher grade = more severe blood pressure) but also predict future cardiovascular disease.14

The blood vessels. Bruits in the neck may indicate carotid stenosis, bruits in the abdomen may indicate renovascular disease, and femoral bruits are a sign of general atherosclerosis. Bruits also signal vascular stenosis and irregularity and may be a clue to vascular damage or future loss of target organ function. However, bruits may simply result from vascular tortuosity, particularly with significant flow in the vessel.

Also check the femoral pulses: poor or delayed femoral pulses are a sign of aortic coarctation. The radial artery is about as far away from the heart as the femoral artery; consequently, when palpating both sites simultaneously the pulse should arrive at about the same moment. In aortic coarctation, a palpable delay in the arrival of the femoral pulse may occur, and an interscapular murmur may be heard during auscultation of the back. In these instances, a low leg blood pressure (usually measured by placing a thigh-sized adult cuff on the patient’s thigh and listening over the popliteal area with the patient prone) may confirm the presence of aortic obstruction. When taking a leg blood pressure, the large cuff and the amount of pressure necessary to occlude the artery may be uncomfortable, and one should warn the patient about the discomfort before taking the measurement.

Poor or absent pedal pulses are a sign of peripheral arterial disease.

The heart (to detect gallops, enlargement, or both). Palpation may reveal a displaced apical impulse, which can indicate left ventricular enlargement. A sustained apical impulse may indicate left ventricular hypertrophy. Listen for a fourth heart sound (S4), one of the earliest physical findings of hypertension when physical findings are present. An S4 indicates that the left atrium is working hard to overcome the stiffness of the left ventricle. An S3 indicates an impairment in left ventricular function and is usually a harbinger of underlying heart disease. In some cases, lung rales can also be heard, though the combination of an S3 gallop and rales is an unusual office presentation in the early management of the hypertensive patient.

The lungs. Listen for rales (see above).

The lower extremities should be examined for peripheral arterial pulsations and edema. The loss of pedal pulses is a common finding, particularly in smokers, and is a clue to increased cardiovascular risk.

Strength, gait, and cognition. Perform a brief neurologic examination for evidence of remote stroke. We usually observe our patients’ gait as they enter or leave the examination room, test their bilateral grip strength, and assess their judgment, speech, and memory during the history and physical examination.

A great deal of research has linked high blood pressure to future loss of cognitive function,15 and it is useful to know that impairment is present before beginning treatment, since some patients will complain of memory loss after starting antihypertensive drug treatment.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Routine tests

The routine evaluation of hypertensive patients should include, at a minimum:

- A hemoglobin or hematocrit measurement

- Urinalysis with microscopic examination

- Serum electrolyte concentrations

- Serum glucose concentration

- A fasting lipid profile

- A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Table 5).

Nonroutine tests

In some cases, other studies may be appropriate, depending on the clinical situation, eg:

- Serum uric acid in those with a history of gout, since some antihypertensive drugs (eg, diuretics) may increase serum uric acid and predispose to further episodes of gout

- Serum calcium in those with a personal or family history of kidney stones, to detect subtle parathyroid excess

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone or other thyroid studies if the history suggests thyroid excess, or if a thyroid nodule is discovered

- Limited echocardiography, which is more sensitive than electrocardiography for detecting left ventricular hypertrophy.

We sometimes use echocardiography if the patient is overweight but seems motivated to lose weight. In these cases we might not start drug therapy right away, choosing rather to wait and see if the patient can lose some weight (which might lower the blood pressure and make drug therapy unnecessary)—but only if the echocardiogram shows that he or she does not have left ventricular hypertrophy.

We also use echocardiography in patients with white-coat hypertension (see below), in whom office pressures are consistently high but whom we have elected to either not treat or not alter treatment. In these cases the echocardiogram serves as a “second opinion” about the merits of not altering therapy and supports this decision when the left ventricular wall thicknesses are normal (and remain so during long-term follow-up). In cases of suspected white-coat hypertension, home or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is valuable to establish or exclude this diagnosis.1

Urinary albumin excretion. Microalbuminuria is an early manifestation of diabetic nephropathy and hypertension. Although routine urine screening for microalbuminuria is typically done in the management of diabetes, it is still not considered a standard of care, though the growing literature on its role as a cardiovascular risk predictor16–18 and its value as a therapeutic target in diabetes19,20 make it an attractive aid in the overall assessment of patients with hypertension.

Plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone concentrations are useful in screening for aldosterone excess, but are usually reserved as follow-up tests in patients with either hypokalemia or failure to achieve blood pressure control on a three-drug regimen in which at least one drug is a diuretic.1,21

Of note, primary aldosteronism is not as rare as previously thought. In a study of patients referred to hypertension centers, 11% had primary aldosteronism according to prospective diagnostic criteria, almost 5% had curable aldosterone-producing adenomas, and 6% had idiopathic hyperaldosteronism.22

If secondary hypertension is suspected

A search for secondary forms of hypertension is usually considered in patients with moderate or severe hypertension that does not respond to antihypertensive agents. Another situation is in hypertensive patients younger than 25 years, since curable forms of hypertension are more common in this age group. In older patients, the prevalence of secondary hypertension is lower and does not justify the costs and effort of routine elaborate workups unless there is evidence from the history, physical examination, or routine laboratory work for suspecting its presence. An exception to this rule is the need to exclude atherosclerotic renovascular hypertension in an elderly patient. This cause of secondary hypertension is common in the elderly and may be amenable to therapeutic intervention.26

WHEN TO CONSIDER HOME OR AMBULATORY MONITORING

Suspected white-coat hypertension

Blood pressure can be influenced by an environment such as an office or hospital clinic. This has led to the development of ambulatory blood pressure monitors and more use of self-measurement of blood pressure in the home. Blood pressure readings with these techniques are generally lower than those measured in an office or hospital clinic. These methods make it possible to screen for white-coat hypertension. In 10% to 20% of people with hypertensive readings, the blood pressure may be elevated persistently only in the presence of a physician.28 When measured elsewhere, including at work, the blood pressure is not elevated in those with the white-coat effect. Although this response may become less prominent with repeated measurements, it occasionally persists in the office setting, sometimes for years in our experience.

Suspected nocturnal hypertension (’nondipping’ status)

Ambulatory blood pressure is also helpful to screen for nocturnal hypertension. Evidence is accumulating to suggest that hypertensive patients whose pressure remains relatively high at night (“nondippers,” ie, those with less than a 10% reduction at night compared with daytime blood pressure readings) are at greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity than “dippers” (those whose blood pressure is at least 10% lower at night than during the day).29

An early morning surge

Ambulatory monitoring can also detect morning surges in systolic blood pressure,30 a marker of cerebrovascular risk. Generally, these patients have an increase of more than 55 mm Hg in systolic pressure between their sleeping and early-hour waking values, and we may wish to start or alter treatment specifically to address these high morning systolic values.31

‘PIPESTEM’ VESSELS AND PSEUDOHYPERTENSION

Occasionally, one encounters patients with vessels that are stiff and difficult to compress. If the pressure required to compress the brachial artery and stop audible blood flow with a standard blood pressure cuff is greater than the actual blood pressure within the artery as measured invasively, the condition is called pseudohypertension. The stiffness is thought to be due to calcification of the arterial wall.

A way to check for this condition is to inflate the cuff to at least 30 mm Hg above the palpable systolic pressure and then try to “roll” the brachial or radial artery underneath your fingertips, a procedure known as Osler’s maneuver.32 If you feel something that resembles a stiff tube reminiscent of the stem of a tobacco smoker’s pipe (healthy arteries are not palpable when empty), the patient may have pseudohypertension. However, the specificity of Osler’s maneuver has been questioned, particularly in hospitalized elderly patients.33

Pseudohypertension is important because the patients in whom it occurs, usually the elderly or the chronically ill (with diabetes or chronic kidney disease), are prone to orthostatic or postural hypotension, which may be aggravated by increasing their antihypertensive treatment on the basis of a cuff pressure that is actually much higher than the real blood pressure.33

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252.

- Wenger NK. Quality of life issues in hypertension: consequences of diagnosis and considerations in management. Am Heart J 1988; 116:628–632.

- McFadden CB, Townsend RR. Blood pressure measurement: common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Consultant 2003; 43:161–165.

- Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111:697–716.

- Myers MG. Automated blood pressure measurement in routine clinical practice. Blood Press Monit 2006; 11:59–62.

- Mosenkis A, Townsend RR. Sitting on the evidence: what is the proper patient position for the office measurement of blood pressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005; 7:365–366.

- Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2002; 287:1003–1010.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:720–732.

- American Diabetes Association. Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:199–201.

- Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2007; 115:2761–2788.

- Papadakis JA, Mikhailidis DP, Vrentzos GE, Kalikaki A, Kazakou I, Ganotakis ES. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on plasma fibrinogen and serum HDL levels in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2005; 11:139–146.

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001; 358:1033–1041.

- Fierro-Carrion GA, Ram CV. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 1997; 80:775–776.

- Wong TY, McIntosh R. Hypertensive retinopathy signs as risk indicators of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 2005; 73–74:57–70.

- Forette F, Boller F. Hypertension and the risk of dementia in the elderly. Am J Med 1991; 90:14S–19S.

- Schrader J, Luders S, Kulschewski A, et al. Microalbuminuria and tubular proteinuria as risk predictors of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in essential hypertension: final results of a prospective long-term study (MARPLE Study). J Hypertens 2006; 24:541–548.

- Luque M, de Rivas B, Alvarez B, Garcia G, Fernandez C, Martell N. Influence of target organ lesion detection (assessment of microalbuminuria and echocardiogram) in cardiovascular risk stratification and treatment of untreated hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 2006; 20:187–192.

- Pontremoli R, Leoncini G, Viazzi F, et al. Role of microalbuminuria in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16 suppl 1:S39–S41.

- Erdmann E. Microalbuminuria as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Cardiol 2006; 107:147–153.

- Bakris GL, Sowers JR. Microalbuminuria in diabetes: focus on cardiovascular and renal risk reduction. Curr Diab Rep 2002; 2:258–262.

- Gallay BJ, Ahmad S, Xu L, Toivola B, Davidson RC. Screening for primary aldosteronism without discontinuing hypertensive medications: plasma aldosteronerenin ratio. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 37:699–705.

- Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:2293–2300.

- Onusko E. Diagnosing secondary hypertension. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:67–74.

- Aurell M. Screening for secondary hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 1999; 1:461.

- Garovic VD, Kane GC, Schwartz GL. Renovascular hypertension: balancing the controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:1135–1137.

- Textor SC. Renovascular hypertension in 2007: where are we now? Curr Cardiol Rep 2007; 9:453–461.

- Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2368–2374.

- Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Gattobigio R, Sardone M, Reboldi G. White-coat hypertension in adults. Blood Press Monit 2005; 10:301–305.

- Cicconetti P, Morelli S, De Serra C, et al. Left ventricular mass in dippers and nondippers with newly diagnosed hypertension. Angiology 2003; 54:661–669.

- Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation 2003; 107:1401–1406.

- Katakam R, Townsend RR. Morning surges in blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens 2006; 8:450–451.

- Messerli FH. Osler’s maneuver, pseudohypertension, and true hypertension in the elderly. Am J Med 1986; 80:906–910.

- Belmin J, Visintin JM, Salvatore R, Sebban C, Moulias R. Osler’s maneuver: absence of usefulness for the detection of pseudohypertension in an elderly population. Am J Med 1995; 98:42–49.

- Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Amodeo C. Osler’s maneuver and pseudohypertension. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:1548–1551.

How extensive a workup does a patient with high blood pressure need?

On one hand, we would not want to start therapy on the basis of a single elevated reading, as blood pressure fluctuates considerably during the day, and even experienced physicians often make errors in taking blood pressure that tend to falsely elevate the patient’s readings. Similarly, we would not want to miss the diagnosis of a potentially curable cause of hypertension or of a condition that increases a patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease. But considering that nearly one-third of adults in the United States have hypertension and that another one-fourth have prehypertension (formerly called high-normal blood pressure),1 if we were to launch an intensive workup for every patient with high blood pressure, the cost and effort would be enormous.

Fortunately, for most patients, it is enough to measure blood pressure accurately and repeatedly, perform a focused history and physical examination, and obtain the results of a few basic laboratory tests and an electrocardiogram, with additional tests in special cases.

In this review we address four fundamental questions in the evaluation of patients with a high blood pressure reading, and how to answer them.

ANSWERING FOUR QUESTIONS

The goal of the hypertension evaluation is to answer four questions:

- Does the patient have sustained hypertension? And if so—

- Is the hypertension primary or secondary?

- Does the patient have other cardiovascular risk factors?

- Does he or she have evidence of target organ damage?

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE SUSTAINED HYPERTENSION?

It is important to measure blood pressure accurately, for several reasons. A diagnosis of hypertension has a measurable impact on the patient’s quality of life.2 Furthermore, we want to avoid undertaking a full evaluation of hypertension if the patient doesn’t actually have high blood pressure, ie, systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. However, many people have blood pressures in the prehypertensive range (ie, 120–139 mm Hg systolic; 80–89 mm Hg diastolic). Many people in this latter group can expect to develop hypertension in time, as the prevalence of hypertension increases steadily with age unless effective preventive measures are implemented, such as losing weight, exercising regularly, and avoiding excessive consumption of sodium and alcohol.

The best position to use is sitting, as the Framingham Heart Study and most randomized clinical trials that established the value of treating hypertension used this position for diagnosis and follow-up.6

Proper patient positioning, the correct cuff size, calibrated equipment, and good inflation and deflation technique will yield the best assessment of blood pressure levels. But even if your technique is perfect, blood pressure is a dynamic vital sign, so it is necessary to repeat the measurement, average the values for any particular day, and keep in mind that the pressure is higher (or lower) on some days than on others, so that the running average is more important than individual readings. This leads to two final points about blood pressure measurement:

- Take it right, at least two times on any occasion

- Take it on at least two (preferably three) separate days.

Following up on blood pressure

After measuring the blood pressure, it is necessary to plan for follow-up readings, guided by both the blood pressure levels (Table 2) and your clinical judgment.

If the systolic and diastolic blood pressures fall into different categories, you should follow the recommendations for the shorter follow-up time.

IS THE HYPERTENSION PRIMARY OR SECONDARY?

Most patients with hypertension have primary (“essential”) hypertension and are likely to remain hypertensive for life. However, some have secondary hypertension, ie, high blood pressure due to an identifiable cause. Some of these conditions (and the hypertension that they cause) can be cured. For example, pheochromocytoma can be cured if found and removed. Other causes of secondary hypertension, such as parenchymal renal disease, are infrequently cured, and the goal is usually to control the blood pressure with drugs.

The sudden onset of severe hypertension in a patient previously known to have had normal blood pressure raises the suspicion of a secondary form of hypertension, as does the onset of hypertension in a young person (< 25 years) or an older person (> 55 years). However, these ages are arbitrary; with the increasing body mass index in young people, essential hypertension is now more commonly diagnosed in the third decade. And since systolic pressure increases throughout life, we can expect many older patients to develop essential hypertension.7 Indeed, current guidelines are urging us to pay more attention to systolic pressure than in the past.

WHAT IS THE PATIENT’S CARDIOVASCULAR RISK?

The relationship between blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease is linear, continuous, and independent of (though additive to) other risk factors.1 For people 40 to 70 years old, each increment of either 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease across the entire range from 115/75 to 185/115 mm Hg.1 If the patient smokes or has elevated cholesterol, other cardiovascular risk factors, or the metabolic syndrome, the risk is even higher.8

The usual goal of antihypertensive treatment is systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg and diastolic pressure less than 90 mm Hg. However, the target is lower—less than 130/80 mm Hg—for those with diabetes9 or target organ damage such as heart failure or renal disease.1,10 Thus, it is important to try to detect these conditions in the evaluation of the hypertensive patient.

Another reason it is important is that reducing such risk sometimes calls for using (or avoiding) antihypertensive drugs that are likely to alter these factors. For example, the use of beta-blockers in patients with a low level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) can lower HDL-C further.11

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE TARGET ORGAN DAMAGE?

Target organ damage is very important to detect because it changes the goal of treatment from primary prevention of adverse target organ outcomes into the more challenging realm of secondary prevention. For example, if a patient has had a stroke, his or her chance of having another stroke in the next 5 years is about 20%. This is much higher than the risk in an average hypertensive patient without such a history. For such patients, the current guidelines1 recommend the combination of a diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, a combination shown to reduce the risk of a second stroke.12 Thus, we need to discover whether the patient had a stroke in the first place.

HISTORY

- The duration (if known) and severity of the hypertension

- The degree of blood pressure fluctuation

- Concomitant medical conditions, especially cardiovascular or renal problems

- Dietary habits

- Alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use

- Level of physical activity

- A family history of hypertension, renal disease, cardiovascular problems, or diabetes mellitus

- Past medications, with particular attention to their side effects and their efficacy in controlling blood pressure

- Current medications, including over-the-counter preparations. One reason: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin can decrease the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs, presumably through mechanisms that inhibit the effects of vasodilatory and natriuretic prostaglandins and potentiate those of angiotensin II.13

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination starts with measurement of height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure—in both arms and the leg if coarctation of the aorta is suspected. Measurements with the patient supine, sitting, and standing are usually taken at the first visit, though such an approach is more suited to a hypertension specialty clinic than a primary care setting, in which time constraints usually limit the blood pressure readings to two or three seated values. Most prospective data on the benefits of hypertension treatment are based on a seated blood pressure, so we favor that measurement for follow-up.

Special attention in the physical examination is directed to:

The retina (to assess the vascular impact of the high blood pressure). Look for arteriolar narrowing (grade 1), arteriovenous compression (grade 2), hemorrhages or exudates (grade 3), and papilledema.2 Such findings not only relate to severity (higher grade = more severe blood pressure) but also predict future cardiovascular disease.14

The blood vessels. Bruits in the neck may indicate carotid stenosis, bruits in the abdomen may indicate renovascular disease, and femoral bruits are a sign of general atherosclerosis. Bruits also signal vascular stenosis and irregularity and may be a clue to vascular damage or future loss of target organ function. However, bruits may simply result from vascular tortuosity, particularly with significant flow in the vessel.

Also check the femoral pulses: poor or delayed femoral pulses are a sign of aortic coarctation. The radial artery is about as far away from the heart as the femoral artery; consequently, when palpating both sites simultaneously the pulse should arrive at about the same moment. In aortic coarctation, a palpable delay in the arrival of the femoral pulse may occur, and an interscapular murmur may be heard during auscultation of the back. In these instances, a low leg blood pressure (usually measured by placing a thigh-sized adult cuff on the patient’s thigh and listening over the popliteal area with the patient prone) may confirm the presence of aortic obstruction. When taking a leg blood pressure, the large cuff and the amount of pressure necessary to occlude the artery may be uncomfortable, and one should warn the patient about the discomfort before taking the measurement.

Poor or absent pedal pulses are a sign of peripheral arterial disease.

The heart (to detect gallops, enlargement, or both). Palpation may reveal a displaced apical impulse, which can indicate left ventricular enlargement. A sustained apical impulse may indicate left ventricular hypertrophy. Listen for a fourth heart sound (S4), one of the earliest physical findings of hypertension when physical findings are present. An S4 indicates that the left atrium is working hard to overcome the stiffness of the left ventricle. An S3 indicates an impairment in left ventricular function and is usually a harbinger of underlying heart disease. In some cases, lung rales can also be heard, though the combination of an S3 gallop and rales is an unusual office presentation in the early management of the hypertensive patient.

The lungs. Listen for rales (see above).

The lower extremities should be examined for peripheral arterial pulsations and edema. The loss of pedal pulses is a common finding, particularly in smokers, and is a clue to increased cardiovascular risk.

Strength, gait, and cognition. Perform a brief neurologic examination for evidence of remote stroke. We usually observe our patients’ gait as they enter or leave the examination room, test their bilateral grip strength, and assess their judgment, speech, and memory during the history and physical examination.

A great deal of research has linked high blood pressure to future loss of cognitive function,15 and it is useful to know that impairment is present before beginning treatment, since some patients will complain of memory loss after starting antihypertensive drug treatment.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Routine tests

The routine evaluation of hypertensive patients should include, at a minimum:

- A hemoglobin or hematocrit measurement

- Urinalysis with microscopic examination

- Serum electrolyte concentrations

- Serum glucose concentration

- A fasting lipid profile

- A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Table 5).

Nonroutine tests

In some cases, other studies may be appropriate, depending on the clinical situation, eg:

- Serum uric acid in those with a history of gout, since some antihypertensive drugs (eg, diuretics) may increase serum uric acid and predispose to further episodes of gout

- Serum calcium in those with a personal or family history of kidney stones, to detect subtle parathyroid excess

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone or other thyroid studies if the history suggests thyroid excess, or if a thyroid nodule is discovered

- Limited echocardiography, which is more sensitive than electrocardiography for detecting left ventricular hypertrophy.

We sometimes use echocardiography if the patient is overweight but seems motivated to lose weight. In these cases we might not start drug therapy right away, choosing rather to wait and see if the patient can lose some weight (which might lower the blood pressure and make drug therapy unnecessary)—but only if the echocardiogram shows that he or she does not have left ventricular hypertrophy.

We also use echocardiography in patients with white-coat hypertension (see below), in whom office pressures are consistently high but whom we have elected to either not treat or not alter treatment. In these cases the echocardiogram serves as a “second opinion” about the merits of not altering therapy and supports this decision when the left ventricular wall thicknesses are normal (and remain so during long-term follow-up). In cases of suspected white-coat hypertension, home or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is valuable to establish or exclude this diagnosis.1

Urinary albumin excretion. Microalbuminuria is an early manifestation of diabetic nephropathy and hypertension. Although routine urine screening for microalbuminuria is typically done in the management of diabetes, it is still not considered a standard of care, though the growing literature on its role as a cardiovascular risk predictor16–18 and its value as a therapeutic target in diabetes19,20 make it an attractive aid in the overall assessment of patients with hypertension.

Plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone concentrations are useful in screening for aldosterone excess, but are usually reserved as follow-up tests in patients with either hypokalemia or failure to achieve blood pressure control on a three-drug regimen in which at least one drug is a diuretic.1,21

Of note, primary aldosteronism is not as rare as previously thought. In a study of patients referred to hypertension centers, 11% had primary aldosteronism according to prospective diagnostic criteria, almost 5% had curable aldosterone-producing adenomas, and 6% had idiopathic hyperaldosteronism.22

If secondary hypertension is suspected

A search for secondary forms of hypertension is usually considered in patients with moderate or severe hypertension that does not respond to antihypertensive agents. Another situation is in hypertensive patients younger than 25 years, since curable forms of hypertension are more common in this age group. In older patients, the prevalence of secondary hypertension is lower and does not justify the costs and effort of routine elaborate workups unless there is evidence from the history, physical examination, or routine laboratory work for suspecting its presence. An exception to this rule is the need to exclude atherosclerotic renovascular hypertension in an elderly patient. This cause of secondary hypertension is common in the elderly and may be amenable to therapeutic intervention.26

WHEN TO CONSIDER HOME OR AMBULATORY MONITORING

Suspected white-coat hypertension

Blood pressure can be influenced by an environment such as an office or hospital clinic. This has led to the development of ambulatory blood pressure monitors and more use of self-measurement of blood pressure in the home. Blood pressure readings with these techniques are generally lower than those measured in an office or hospital clinic. These methods make it possible to screen for white-coat hypertension. In 10% to 20% of people with hypertensive readings, the blood pressure may be elevated persistently only in the presence of a physician.28 When measured elsewhere, including at work, the blood pressure is not elevated in those with the white-coat effect. Although this response may become less prominent with repeated measurements, it occasionally persists in the office setting, sometimes for years in our experience.

Suspected nocturnal hypertension (’nondipping’ status)

Ambulatory blood pressure is also helpful to screen for nocturnal hypertension. Evidence is accumulating to suggest that hypertensive patients whose pressure remains relatively high at night (“nondippers,” ie, those with less than a 10% reduction at night compared with daytime blood pressure readings) are at greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity than “dippers” (those whose blood pressure is at least 10% lower at night than during the day).29

An early morning surge

Ambulatory monitoring can also detect morning surges in systolic blood pressure,30 a marker of cerebrovascular risk. Generally, these patients have an increase of more than 55 mm Hg in systolic pressure between their sleeping and early-hour waking values, and we may wish to start or alter treatment specifically to address these high morning systolic values.31

‘PIPESTEM’ VESSELS AND PSEUDOHYPERTENSION

Occasionally, one encounters patients with vessels that are stiff and difficult to compress. If the pressure required to compress the brachial artery and stop audible blood flow with a standard blood pressure cuff is greater than the actual blood pressure within the artery as measured invasively, the condition is called pseudohypertension. The stiffness is thought to be due to calcification of the arterial wall.

A way to check for this condition is to inflate the cuff to at least 30 mm Hg above the palpable systolic pressure and then try to “roll” the brachial or radial artery underneath your fingertips, a procedure known as Osler’s maneuver.32 If you feel something that resembles a stiff tube reminiscent of the stem of a tobacco smoker’s pipe (healthy arteries are not palpable when empty), the patient may have pseudohypertension. However, the specificity of Osler’s maneuver has been questioned, particularly in hospitalized elderly patients.33

Pseudohypertension is important because the patients in whom it occurs, usually the elderly or the chronically ill (with diabetes or chronic kidney disease), are prone to orthostatic or postural hypotension, which may be aggravated by increasing their antihypertensive treatment on the basis of a cuff pressure that is actually much higher than the real blood pressure.33

How extensive a workup does a patient with high blood pressure need?

On one hand, we would not want to start therapy on the basis of a single elevated reading, as blood pressure fluctuates considerably during the day, and even experienced physicians often make errors in taking blood pressure that tend to falsely elevate the patient’s readings. Similarly, we would not want to miss the diagnosis of a potentially curable cause of hypertension or of a condition that increases a patient’s risk of cardiovascular disease. But considering that nearly one-third of adults in the United States have hypertension and that another one-fourth have prehypertension (formerly called high-normal blood pressure),1 if we were to launch an intensive workup for every patient with high blood pressure, the cost and effort would be enormous.

Fortunately, for most patients, it is enough to measure blood pressure accurately and repeatedly, perform a focused history and physical examination, and obtain the results of a few basic laboratory tests and an electrocardiogram, with additional tests in special cases.

In this review we address four fundamental questions in the evaluation of patients with a high blood pressure reading, and how to answer them.

ANSWERING FOUR QUESTIONS

The goal of the hypertension evaluation is to answer four questions:

- Does the patient have sustained hypertension? And if so—

- Is the hypertension primary or secondary?

- Does the patient have other cardiovascular risk factors?

- Does he or she have evidence of target organ damage?

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE SUSTAINED HYPERTENSION?

It is important to measure blood pressure accurately, for several reasons. A diagnosis of hypertension has a measurable impact on the patient’s quality of life.2 Furthermore, we want to avoid undertaking a full evaluation of hypertension if the patient doesn’t actually have high blood pressure, ie, systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or diastolic pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. However, many people have blood pressures in the prehypertensive range (ie, 120–139 mm Hg systolic; 80–89 mm Hg diastolic). Many people in this latter group can expect to develop hypertension in time, as the prevalence of hypertension increases steadily with age unless effective preventive measures are implemented, such as losing weight, exercising regularly, and avoiding excessive consumption of sodium and alcohol.

The best position to use is sitting, as the Framingham Heart Study and most randomized clinical trials that established the value of treating hypertension used this position for diagnosis and follow-up.6

Proper patient positioning, the correct cuff size, calibrated equipment, and good inflation and deflation technique will yield the best assessment of blood pressure levels. But even if your technique is perfect, blood pressure is a dynamic vital sign, so it is necessary to repeat the measurement, average the values for any particular day, and keep in mind that the pressure is higher (or lower) on some days than on others, so that the running average is more important than individual readings. This leads to two final points about blood pressure measurement:

- Take it right, at least two times on any occasion

- Take it on at least two (preferably three) separate days.

Following up on blood pressure

After measuring the blood pressure, it is necessary to plan for follow-up readings, guided by both the blood pressure levels (Table 2) and your clinical judgment.

If the systolic and diastolic blood pressures fall into different categories, you should follow the recommendations for the shorter follow-up time.

IS THE HYPERTENSION PRIMARY OR SECONDARY?

Most patients with hypertension have primary (“essential”) hypertension and are likely to remain hypertensive for life. However, some have secondary hypertension, ie, high blood pressure due to an identifiable cause. Some of these conditions (and the hypertension that they cause) can be cured. For example, pheochromocytoma can be cured if found and removed. Other causes of secondary hypertension, such as parenchymal renal disease, are infrequently cured, and the goal is usually to control the blood pressure with drugs.

The sudden onset of severe hypertension in a patient previously known to have had normal blood pressure raises the suspicion of a secondary form of hypertension, as does the onset of hypertension in a young person (< 25 years) or an older person (> 55 years). However, these ages are arbitrary; with the increasing body mass index in young people, essential hypertension is now more commonly diagnosed in the third decade. And since systolic pressure increases throughout life, we can expect many older patients to develop essential hypertension.7 Indeed, current guidelines are urging us to pay more attention to systolic pressure than in the past.

WHAT IS THE PATIENT’S CARDIOVASCULAR RISK?

The relationship between blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease is linear, continuous, and independent of (though additive to) other risk factors.1 For people 40 to 70 years old, each increment of either 20 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure or 10 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease across the entire range from 115/75 to 185/115 mm Hg.1 If the patient smokes or has elevated cholesterol, other cardiovascular risk factors, or the metabolic syndrome, the risk is even higher.8

The usual goal of antihypertensive treatment is systolic pressure less than 140 mm Hg and diastolic pressure less than 90 mm Hg. However, the target is lower—less than 130/80 mm Hg—for those with diabetes9 or target organ damage such as heart failure or renal disease.1,10 Thus, it is important to try to detect these conditions in the evaluation of the hypertensive patient.

Another reason it is important is that reducing such risk sometimes calls for using (or avoiding) antihypertensive drugs that are likely to alter these factors. For example, the use of beta-blockers in patients with a low level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) can lower HDL-C further.11

DOES THE PATIENT HAVE TARGET ORGAN DAMAGE?

Target organ damage is very important to detect because it changes the goal of treatment from primary prevention of adverse target organ outcomes into the more challenging realm of secondary prevention. For example, if a patient has had a stroke, his or her chance of having another stroke in the next 5 years is about 20%. This is much higher than the risk in an average hypertensive patient without such a history. For such patients, the current guidelines1 recommend the combination of a diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, a combination shown to reduce the risk of a second stroke.12 Thus, we need to discover whether the patient had a stroke in the first place.

HISTORY

- The duration (if known) and severity of the hypertension

- The degree of blood pressure fluctuation

- Concomitant medical conditions, especially cardiovascular or renal problems

- Dietary habits

- Alcohol consumption

- Tobacco use

- Level of physical activity

- A family history of hypertension, renal disease, cardiovascular problems, or diabetes mellitus

- Past medications, with particular attention to their side effects and their efficacy in controlling blood pressure

- Current medications, including over-the-counter preparations. One reason: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin can decrease the efficacy of antihypertensive drugs, presumably through mechanisms that inhibit the effects of vasodilatory and natriuretic prostaglandins and potentiate those of angiotensin II.13

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination starts with measurement of height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure—in both arms and the leg if coarctation of the aorta is suspected. Measurements with the patient supine, sitting, and standing are usually taken at the first visit, though such an approach is more suited to a hypertension specialty clinic than a primary care setting, in which time constraints usually limit the blood pressure readings to two or three seated values. Most prospective data on the benefits of hypertension treatment are based on a seated blood pressure, so we favor that measurement for follow-up.

Special attention in the physical examination is directed to:

The retina (to assess the vascular impact of the high blood pressure). Look for arteriolar narrowing (grade 1), arteriovenous compression (grade 2), hemorrhages or exudates (grade 3), and papilledema.2 Such findings not only relate to severity (higher grade = more severe blood pressure) but also predict future cardiovascular disease.14

The blood vessels. Bruits in the neck may indicate carotid stenosis, bruits in the abdomen may indicate renovascular disease, and femoral bruits are a sign of general atherosclerosis. Bruits also signal vascular stenosis and irregularity and may be a clue to vascular damage or future loss of target organ function. However, bruits may simply result from vascular tortuosity, particularly with significant flow in the vessel.

Also check the femoral pulses: poor or delayed femoral pulses are a sign of aortic coarctation. The radial artery is about as far away from the heart as the femoral artery; consequently, when palpating both sites simultaneously the pulse should arrive at about the same moment. In aortic coarctation, a palpable delay in the arrival of the femoral pulse may occur, and an interscapular murmur may be heard during auscultation of the back. In these instances, a low leg blood pressure (usually measured by placing a thigh-sized adult cuff on the patient’s thigh and listening over the popliteal area with the patient prone) may confirm the presence of aortic obstruction. When taking a leg blood pressure, the large cuff and the amount of pressure necessary to occlude the artery may be uncomfortable, and one should warn the patient about the discomfort before taking the measurement.

Poor or absent pedal pulses are a sign of peripheral arterial disease.

The heart (to detect gallops, enlargement, or both). Palpation may reveal a displaced apical impulse, which can indicate left ventricular enlargement. A sustained apical impulse may indicate left ventricular hypertrophy. Listen for a fourth heart sound (S4), one of the earliest physical findings of hypertension when physical findings are present. An S4 indicates that the left atrium is working hard to overcome the stiffness of the left ventricle. An S3 indicates an impairment in left ventricular function and is usually a harbinger of underlying heart disease. In some cases, lung rales can also be heard, though the combination of an S3 gallop and rales is an unusual office presentation in the early management of the hypertensive patient.

The lungs. Listen for rales (see above).

The lower extremities should be examined for peripheral arterial pulsations and edema. The loss of pedal pulses is a common finding, particularly in smokers, and is a clue to increased cardiovascular risk.

Strength, gait, and cognition. Perform a brief neurologic examination for evidence of remote stroke. We usually observe our patients’ gait as they enter or leave the examination room, test their bilateral grip strength, and assess their judgment, speech, and memory during the history and physical examination.

A great deal of research has linked high blood pressure to future loss of cognitive function,15 and it is useful to know that impairment is present before beginning treatment, since some patients will complain of memory loss after starting antihypertensive drug treatment.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Routine tests

The routine evaluation of hypertensive patients should include, at a minimum:

- A hemoglobin or hematocrit measurement

- Urinalysis with microscopic examination

- Serum electrolyte concentrations

- Serum glucose concentration

- A fasting lipid profile

- A 12-lead electrocardiogram (Table 5).

Nonroutine tests

In some cases, other studies may be appropriate, depending on the clinical situation, eg:

- Serum uric acid in those with a history of gout, since some antihypertensive drugs (eg, diuretics) may increase serum uric acid and predispose to further episodes of gout

- Serum calcium in those with a personal or family history of kidney stones, to detect subtle parathyroid excess

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone or other thyroid studies if the history suggests thyroid excess, or if a thyroid nodule is discovered

- Limited echocardiography, which is more sensitive than electrocardiography for detecting left ventricular hypertrophy.

We sometimes use echocardiography if the patient is overweight but seems motivated to lose weight. In these cases we might not start drug therapy right away, choosing rather to wait and see if the patient can lose some weight (which might lower the blood pressure and make drug therapy unnecessary)—but only if the echocardiogram shows that he or she does not have left ventricular hypertrophy.

We also use echocardiography in patients with white-coat hypertension (see below), in whom office pressures are consistently high but whom we have elected to either not treat or not alter treatment. In these cases the echocardiogram serves as a “second opinion” about the merits of not altering therapy and supports this decision when the left ventricular wall thicknesses are normal (and remain so during long-term follow-up). In cases of suspected white-coat hypertension, home or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is valuable to establish or exclude this diagnosis.1

Urinary albumin excretion. Microalbuminuria is an early manifestation of diabetic nephropathy and hypertension. Although routine urine screening for microalbuminuria is typically done in the management of diabetes, it is still not considered a standard of care, though the growing literature on its role as a cardiovascular risk predictor16–18 and its value as a therapeutic target in diabetes19,20 make it an attractive aid in the overall assessment of patients with hypertension.

Plasma renin activity and serum aldosterone concentrations are useful in screening for aldosterone excess, but are usually reserved as follow-up tests in patients with either hypokalemia or failure to achieve blood pressure control on a three-drug regimen in which at least one drug is a diuretic.1,21

Of note, primary aldosteronism is not as rare as previously thought. In a study of patients referred to hypertension centers, 11% had primary aldosteronism according to prospective diagnostic criteria, almost 5% had curable aldosterone-producing adenomas, and 6% had idiopathic hyperaldosteronism.22

If secondary hypertension is suspected

A search for secondary forms of hypertension is usually considered in patients with moderate or severe hypertension that does not respond to antihypertensive agents. Another situation is in hypertensive patients younger than 25 years, since curable forms of hypertension are more common in this age group. In older patients, the prevalence of secondary hypertension is lower and does not justify the costs and effort of routine elaborate workups unless there is evidence from the history, physical examination, or routine laboratory work for suspecting its presence. An exception to this rule is the need to exclude atherosclerotic renovascular hypertension in an elderly patient. This cause of secondary hypertension is common in the elderly and may be amenable to therapeutic intervention.26

WHEN TO CONSIDER HOME OR AMBULATORY MONITORING

Suspected white-coat hypertension

Blood pressure can be influenced by an environment such as an office or hospital clinic. This has led to the development of ambulatory blood pressure monitors and more use of self-measurement of blood pressure in the home. Blood pressure readings with these techniques are generally lower than those measured in an office or hospital clinic. These methods make it possible to screen for white-coat hypertension. In 10% to 20% of people with hypertensive readings, the blood pressure may be elevated persistently only in the presence of a physician.28 When measured elsewhere, including at work, the blood pressure is not elevated in those with the white-coat effect. Although this response may become less prominent with repeated measurements, it occasionally persists in the office setting, sometimes for years in our experience.

Suspected nocturnal hypertension (’nondipping’ status)

Ambulatory blood pressure is also helpful to screen for nocturnal hypertension. Evidence is accumulating to suggest that hypertensive patients whose pressure remains relatively high at night (“nondippers,” ie, those with less than a 10% reduction at night compared with daytime blood pressure readings) are at greater risk of cardiovascular morbidity than “dippers” (those whose blood pressure is at least 10% lower at night than during the day).29

An early morning surge

Ambulatory monitoring can also detect morning surges in systolic blood pressure,30 a marker of cerebrovascular risk. Generally, these patients have an increase of more than 55 mm Hg in systolic pressure between their sleeping and early-hour waking values, and we may wish to start or alter treatment specifically to address these high morning systolic values.31

‘PIPESTEM’ VESSELS AND PSEUDOHYPERTENSION

Occasionally, one encounters patients with vessels that are stiff and difficult to compress. If the pressure required to compress the brachial artery and stop audible blood flow with a standard blood pressure cuff is greater than the actual blood pressure within the artery as measured invasively, the condition is called pseudohypertension. The stiffness is thought to be due to calcification of the arterial wall.

A way to check for this condition is to inflate the cuff to at least 30 mm Hg above the palpable systolic pressure and then try to “roll” the brachial or radial artery underneath your fingertips, a procedure known as Osler’s maneuver.32 If you feel something that resembles a stiff tube reminiscent of the stem of a tobacco smoker’s pipe (healthy arteries are not palpable when empty), the patient may have pseudohypertension. However, the specificity of Osler’s maneuver has been questioned, particularly in hospitalized elderly patients.33

Pseudohypertension is important because the patients in whom it occurs, usually the elderly or the chronically ill (with diabetes or chronic kidney disease), are prone to orthostatic or postural hypotension, which may be aggravated by increasing their antihypertensive treatment on the basis of a cuff pressure that is actually much higher than the real blood pressure.33

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252.

- Wenger NK. Quality of life issues in hypertension: consequences of diagnosis and considerations in management. Am Heart J 1988; 116:628–632.

- McFadden CB, Townsend RR. Blood pressure measurement: common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Consultant 2003; 43:161–165.

- Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111:697–716.

- Myers MG. Automated blood pressure measurement in routine clinical practice. Blood Press Monit 2006; 11:59–62.

- Mosenkis A, Townsend RR. Sitting on the evidence: what is the proper patient position for the office measurement of blood pressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005; 7:365–366.

- Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2002; 287:1003–1010.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:720–732.

- American Diabetes Association. Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:199–201.

- Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2007; 115:2761–2788.

- Papadakis JA, Mikhailidis DP, Vrentzos GE, Kalikaki A, Kazakou I, Ganotakis ES. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on plasma fibrinogen and serum HDL levels in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2005; 11:139–146.

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001; 358:1033–1041.

- Fierro-Carrion GA, Ram CV. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 1997; 80:775–776.

- Wong TY, McIntosh R. Hypertensive retinopathy signs as risk indicators of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 2005; 73–74:57–70.

- Forette F, Boller F. Hypertension and the risk of dementia in the elderly. Am J Med 1991; 90:14S–19S.

- Schrader J, Luders S, Kulschewski A, et al. Microalbuminuria and tubular proteinuria as risk predictors of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in essential hypertension: final results of a prospective long-term study (MARPLE Study). J Hypertens 2006; 24:541–548.

- Luque M, de Rivas B, Alvarez B, Garcia G, Fernandez C, Martell N. Influence of target organ lesion detection (assessment of microalbuminuria and echocardiogram) in cardiovascular risk stratification and treatment of untreated hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 2006; 20:187–192.

- Pontremoli R, Leoncini G, Viazzi F, et al. Role of microalbuminuria in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16 suppl 1:S39–S41.

- Erdmann E. Microalbuminuria as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Cardiol 2006; 107:147–153.

- Bakris GL, Sowers JR. Microalbuminuria in diabetes: focus on cardiovascular and renal risk reduction. Curr Diab Rep 2002; 2:258–262.

- Gallay BJ, Ahmad S, Xu L, Toivola B, Davidson RC. Screening for primary aldosteronism without discontinuing hypertensive medications: plasma aldosteronerenin ratio. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 37:699–705.

- Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:2293–2300.

- Onusko E. Diagnosing secondary hypertension. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:67–74.

- Aurell M. Screening for secondary hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 1999; 1:461.

- Garovic VD, Kane GC, Schwartz GL. Renovascular hypertension: balancing the controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:1135–1137.

- Textor SC. Renovascular hypertension in 2007: where are we now? Curr Cardiol Rep 2007; 9:453–461.

- Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2368–2374.

- Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Gattobigio R, Sardone M, Reboldi G. White-coat hypertension in adults. Blood Press Monit 2005; 10:301–305.

- Cicconetti P, Morelli S, De Serra C, et al. Left ventricular mass in dippers and nondippers with newly diagnosed hypertension. Angiology 2003; 54:661–669.

- Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation 2003; 107:1401–1406.

- Katakam R, Townsend RR. Morning surges in blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens 2006; 8:450–451.

- Messerli FH. Osler’s maneuver, pseudohypertension, and true hypertension in the elderly. Am J Med 1986; 80:906–910.

- Belmin J, Visintin JM, Salvatore R, Sebban C, Moulias R. Osler’s maneuver: absence of usefulness for the detection of pseudohypertension in an elderly population. Am J Med 1995; 98:42–49.

- Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Amodeo C. Osler’s maneuver and pseudohypertension. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:1548–1551.

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42:1206–1252.

- Wenger NK. Quality of life issues in hypertension: consequences of diagnosis and considerations in management. Am Heart J 1988; 116:628–632.

- McFadden CB, Townsend RR. Blood pressure measurement: common pitfalls and how to avoid them. Consultant 2003; 43:161–165.

- Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation 2005; 111:697–716.

- Myers MG. Automated blood pressure measurement in routine clinical practice. Blood Press Monit 2006; 11:59–62.

- Mosenkis A, Townsend RR. Sitting on the evidence: what is the proper patient position for the office measurement of blood pressure? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2005; 7:365–366.

- Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 2002; 287:1003–1010.

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:720–732.

- American Diabetes Association. Treatment of hypertension in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002; 25:199–201.

- Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation 2007; 115:2761–2788.

- Papadakis JA, Mikhailidis DP, Vrentzos GE, Kalikaki A, Kazakou I, Ganotakis ES. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on plasma fibrinogen and serum HDL levels in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2005; 11:139–146.

- PROGRESS Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6,105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001; 358:1033–1041.

- Fierro-Carrion GA, Ram CV. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and blood pressure. Am J Cardiol 1997; 80:775–776.

- Wong TY, McIntosh R. Hypertensive retinopathy signs as risk indicators of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 2005; 73–74:57–70.

- Forette F, Boller F. Hypertension and the risk of dementia in the elderly. Am J Med 1991; 90:14S–19S.

- Schrader J, Luders S, Kulschewski A, et al. Microalbuminuria and tubular proteinuria as risk predictors of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in essential hypertension: final results of a prospective long-term study (MARPLE Study). J Hypertens 2006; 24:541–548.

- Luque M, de Rivas B, Alvarez B, Garcia G, Fernandez C, Martell N. Influence of target organ lesion detection (assessment of microalbuminuria and echocardiogram) in cardiovascular risk stratification and treatment of untreated hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens 2006; 20:187–192.

- Pontremoli R, Leoncini G, Viazzi F, et al. Role of microalbuminuria in the assessment of cardiovascular risk in essential hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16 suppl 1:S39–S41.

- Erdmann E. Microalbuminuria as a marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Cardiol 2006; 107:147–153.

- Bakris GL, Sowers JR. Microalbuminuria in diabetes: focus on cardiovascular and renal risk reduction. Curr Diab Rep 2002; 2:258–262.

- Gallay BJ, Ahmad S, Xu L, Toivola B, Davidson RC. Screening for primary aldosteronism without discontinuing hypertensive medications: plasma aldosteronerenin ratio. Am J Kidney Dis 2001; 37:699–705.

- Rossi GP, Bernini G, Caliumi C, et al. A prospective study of the prevalence of primary aldosteronism in 1,125 hypertensive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 48:2293–2300.

- Onusko E. Diagnosing secondary hypertension. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67:67–74.

- Aurell M. Screening for secondary hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 1999; 1:461.

- Garovic VD, Kane GC, Schwartz GL. Renovascular hypertension: balancing the controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:1135–1137.

- Textor SC. Renovascular hypertension in 2007: where are we now? Curr Cardiol Rep 2007; 9:453–461.

- Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:2368–2374.

- Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Gattobigio R, Sardone M, Reboldi G. White-coat hypertension in adults. Blood Press Monit 2005; 10:301–305.

- Cicconetti P, Morelli S, De Serra C, et al. Left ventricular mass in dippers and nondippers with newly diagnosed hypertension. Angiology 2003; 54:661–669.

- Kario K, Pickering TG, Umeda Y, et al. Morning surge in blood pressure as a predictor of silent and clinical cerebrovascular disease in elderly hypertensives: a prospective study. Circulation 2003; 107:1401–1406.

- Katakam R, Townsend RR. Morning surges in blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens 2006; 8:450–451.

- Messerli FH. Osler’s maneuver, pseudohypertension, and true hypertension in the elderly. Am J Med 1986; 80:906–910.

- Belmin J, Visintin JM, Salvatore R, Sebban C, Moulias R. Osler’s maneuver: absence of usefulness for the detection of pseudohypertension in an elderly population. Am J Med 1995; 98:42–49.

- Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Amodeo C. Osler’s maneuver and pseudohypertension. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:1548–1551.

KEY POINTS

- To confirm the diagnosis of hypertension, multiple readings should be taken at various times.

- Proper technique is important in measuring blood pressure, including using the correct cuff size, having the patient sit quietly for 5 minutes before taking the pressure, and supporting the arm at the level of the heart.

- If white-coat hypertension is suspected, one can consider ambulatory or home blood pressure measurements to confirm that the hypertension is sustained.

Perioperative statins: More than lipid-lowering?

Soon, the checklist for internists seeing patients about to undergo surgery may include prescribing one of the lipid-lowering hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, also called statins.

Statins? Not long ago, we were debating whether patients who take statins should stop taking them before surgery, based on the manufacturers’ recommendations.1 The discussion, however, has changed to whether patients who have never received a statin should be started on one before surgery to provide immediate prophylaxis against cardiac morbidity, and how much harm long-term statin users face if these drugs are withheld perioperatively.

The evidence is still very preliminary and based mostly on studies in animals and retrospective studies in people. However, an expanding body of indirect evidence suggests that these drugs are beneficial in this situation.

In this review, we discuss the mechanisms by which statins may protect the heart in the short term, drawing on data from animal and human studies of acute myocardial infarction, and we review the current (albeit limited) data from the perioperative setting.

FEW INTERVENTIONS DECREASE RISK

Each year, approximately 50,000 patients suffer a perioperative cardiovascular event; the incidence of myocardial infarction during or after noncardiac surgery is 2% to 3%.2 The primary goal of preoperative cardiovascular risk assessment is to predict and avert these events.

But short of canceling surgery, few interventions have been found to reduce a patient’s risk. For example, a landmark study in 2004 cast doubt on the efficacy of preoperative coronary revascularization.3 Similarly, although early studies of beta-blockers were promising4,5 and although most internists prescribe these drugs before surgery, more recent studies have cast doubt on their efficacy, particularly in patients at low risk undergoing intermediate-risk (rather than vascular) surgery.6–8

This changing clinical landscape has prompted a search for new strategies for perioperative risk-reduction. Several recent studies have placed statins in the spotlight.

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS OF SHORT-TERM BENEFIT

Statins have been proven to save lives when used long-term, but how could this class of drugs, designed to prevent the accumulation of arterial plaques by lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, have any short-term impact on operative outcomes? Although LDL-C reduction is the principal mechanism of action of statins, not all of the benefit can be ascribed to this mechanism.9 The answer may lie in their “pleiotropic” effects—ie, actions other than LDL-C reduction.

The more immediate pleiotropic effects of statins in the proinflammatory and prothrombotic environment of the perioperative period are thought to include improved endothelial function (both antithrombotic function and vasomotor function in response to ischemic stress), enhanced stability of atherosclerotic plaques, decreased oxidative stress, and decreased vascular inflammation.10–12

EVIDENCE FROM ANIMAL STUDIES

Experiments in animals suggest that statins, given shortly before or after a cardiovascular event, confer benefit before any changes in LDL-C are measurable.

Lefer et al13 found that simvastatin (Zocor), given 18 hours before an ischemic episode in rats, blunted the inflammatory response in cardiac reperfusion injury. Not only was reperfusion injury significantly less in the hearts of the rats that received simvastatin than in the saline control group, but the simvastatin-treated hearts also expressed fewer neutrophil adhesion molecules such as P-selectin, and they had more basal release of nitric oxide, the potent endothelial-derived vasodilator with antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative effects.14 These results suggest that statins may improve endothelial function acutely, particularly during ischemic stress.