User login

Plan Good Discharges

It was probably just the ramblings of a mad woman. Only she wasn’t mad, so I searched for a hint of delirium. Nothing. She was mentally fit and lucid—perhaps too lucid. Could it be true … had I become my archenemy?

To decide, I put her utterance to the test through the Kubler-Ross obstacle course, hopping the denial hurdle, quick-footing through the anger tire course, wading through the bargaining pool, and finally swinging safely across the depression crevasse to acceptance.

She was my eighth patient that day, a 78-year-old woman admitted to the orthopedic service with a hip fracture. I was asked to do a preoperative risk assessment and comanage her diabetes and heart failure. During our introductions she asked what kind of doctor I was.

“A hospitalist,” I replied.

“Oh … that’s nice,” she answered, her furrowed eyebrow transforming her crow’s feet into a question mark.

“You know, a doctor who only cares for patients in the hospital,” I clarified. “I just take care of your acute problems.”

“You think a broken hip is cute?”

“No, no, not ‘cute.’ Acute. You know, I only deal with your urgent problems. When you leave here you will go back to see your primary care doctor, who will follow up your hip fracture and your more chronic issues.”

That’s when she dropped the bomb.

“Oh, I see; you’re sort of like a contractor for my body then—just helping when things get broke.”

I should explain my aversion to this comment. Reared by a 10-thumbed father, I’m genetically incapable of curing even the simplest household hiccup. This doesn’t mean I haven’t or won’t try. In fact, I’m willing to try anything. My wife, however, is too smart to allow that. She knows that home improvement project plus me equals larger home improvement project. Combine this mathematical axiom with our turn-of-the-(20th)-century home, and it’s easy to see why I find myself betrothed in nearly continuous engagement with contractors.

But this is a marriage on the rocks. As dependent as I am on home contractors, I generally dislike working with them. They’re all fine people I’m sure, and truth be told most of them are quite skilled at their work. The problem is that they go about their job as if they are allergic to customer service.

The only contractors who are not perpetually late are those who won’t give you a time to meet. “I’ll meet you in the morning,” they’ll say, only to define morning as any time after the sun comes up.

Then there’s the estimate, which appears to be an approximation calculated in a cavernous ballpark using an underestimater. It’s also not exactly clear how or what goes into the calculation of an estimate.

I recently got a written estimate that read as follows: “Fix sink, $400.” When I asked what the $400 would go toward, I got the ever-so-helpful reply: “Fixing the sink.” I responded, “No, I mean, how much are the parts and the labor and things like that?” He gruffly countered, “Four hundred dollars.” Uncovering how he came up with this estimate was about as easy as solving a Rubik’s cube. I gave up trying—and eventually paid $550.

Another time, a contractor agreed to fix a plumbing leak in our upstairs bathroom that had caused water damage to our first-floor ceiling. While tearing out the floor to reach the leak, he mistakenly ran a circular saw through a pipe, causing a considerably larger gusher that quickly destroyed said ceiling.

I understand these things happen. However, imagine my surprise when the eventual project cost was more than twice the estimated cost. He explained that repairing the new water damage was quite expensive and accounted for the variance with the estimate. We “discussed” this development, during which time I explained to him in no uncertain terms what the temperature in hell would be when I paid for his mistake.

So, it stung a bit to be called a “contractor.” But I could live with it. In fact, on the surface my patient’s analogy was quite good. Hospitalists do swoop in and fix patients’ problems only to then leave their lives, most often for good. It was only after a few days that her statement started to sour in my amygdala.

Habitual tardiness, sketchy response times, vague payment structures, lack of transparency in pricing, pricing errors into the cost of the job—I don’t think the analogy was intended to be so perceptive. I and the healthcare system within which I work really had adopted some of the less-desirable attributes of the contracting world.

I usually tell patients I’ll be back in an hour to give them their test results, knowing that I’m on “doctor time” and this could mean several hours or more. My tardiness usually results from being delayed while caring for another patient—but it’s all the same to the patient left waiting. Trying to build in cushion time for these unforeseen delays leaves a patient with a disagreeable contractor-like window of time to wait. For those who want to have their family at our daily rounds, an “I’ll come see you in the morning” is not just unhelpful—it disrespects the importance of their time.

Then there’s our payment system. It’s a mystery even to me: $12 aspirins, $100,000 cancer drugs, intentionally inflated professional fees and hospital bills that aren’t expected to be paid in full (unless the patient lacks an insurer to negotiate a lower price when they ironically are expected to foot the entire bill). All of which is made worse by the lack of transparency in our pricing. Patients (and most often I) simply are not privy to the costs of various tests and interventions. And, costs for the same procedure often differ among hospitals.

Few of us would contract for work without playing a role in choosing the supplies and knowing the rough cost of the materials. Yet that’s the situation our patients find themselves in daily.

Finally, expecting patients or their insurers to pay for my mistakes is not fair. I recognize there are adverse events that are unavoidable and should be reimbursed. However, many errors are as avoidable as being careful not to cut through a working pipe. Payment for these outcomes should be shouldered by the health system—not the patient.

I limped through the next few days re-examining my patient interactions. I licked my wounds, vowing to eschew those traits that so offend me as a consumer. I might not be able to repair a broken healthcare system, but I can refurbish the way I interact with my patients by being timely and responsive and not underestimating the effect of poor customer service. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It was probably just the ramblings of a mad woman. Only she wasn’t mad, so I searched for a hint of delirium. Nothing. She was mentally fit and lucid—perhaps too lucid. Could it be true … had I become my archenemy?

To decide, I put her utterance to the test through the Kubler-Ross obstacle course, hopping the denial hurdle, quick-footing through the anger tire course, wading through the bargaining pool, and finally swinging safely across the depression crevasse to acceptance.

She was my eighth patient that day, a 78-year-old woman admitted to the orthopedic service with a hip fracture. I was asked to do a preoperative risk assessment and comanage her diabetes and heart failure. During our introductions she asked what kind of doctor I was.

“A hospitalist,” I replied.

“Oh … that’s nice,” she answered, her furrowed eyebrow transforming her crow’s feet into a question mark.

“You know, a doctor who only cares for patients in the hospital,” I clarified. “I just take care of your acute problems.”

“You think a broken hip is cute?”

“No, no, not ‘cute.’ Acute. You know, I only deal with your urgent problems. When you leave here you will go back to see your primary care doctor, who will follow up your hip fracture and your more chronic issues.”

That’s when she dropped the bomb.

“Oh, I see; you’re sort of like a contractor for my body then—just helping when things get broke.”

I should explain my aversion to this comment. Reared by a 10-thumbed father, I’m genetically incapable of curing even the simplest household hiccup. This doesn’t mean I haven’t or won’t try. In fact, I’m willing to try anything. My wife, however, is too smart to allow that. She knows that home improvement project plus me equals larger home improvement project. Combine this mathematical axiom with our turn-of-the-(20th)-century home, and it’s easy to see why I find myself betrothed in nearly continuous engagement with contractors.

But this is a marriage on the rocks. As dependent as I am on home contractors, I generally dislike working with them. They’re all fine people I’m sure, and truth be told most of them are quite skilled at their work. The problem is that they go about their job as if they are allergic to customer service.

The only contractors who are not perpetually late are those who won’t give you a time to meet. “I’ll meet you in the morning,” they’ll say, only to define morning as any time after the sun comes up.

Then there’s the estimate, which appears to be an approximation calculated in a cavernous ballpark using an underestimater. It’s also not exactly clear how or what goes into the calculation of an estimate.

I recently got a written estimate that read as follows: “Fix sink, $400.” When I asked what the $400 would go toward, I got the ever-so-helpful reply: “Fixing the sink.” I responded, “No, I mean, how much are the parts and the labor and things like that?” He gruffly countered, “Four hundred dollars.” Uncovering how he came up with this estimate was about as easy as solving a Rubik’s cube. I gave up trying—and eventually paid $550.

Another time, a contractor agreed to fix a plumbing leak in our upstairs bathroom that had caused water damage to our first-floor ceiling. While tearing out the floor to reach the leak, he mistakenly ran a circular saw through a pipe, causing a considerably larger gusher that quickly destroyed said ceiling.

I understand these things happen. However, imagine my surprise when the eventual project cost was more than twice the estimated cost. He explained that repairing the new water damage was quite expensive and accounted for the variance with the estimate. We “discussed” this development, during which time I explained to him in no uncertain terms what the temperature in hell would be when I paid for his mistake.

So, it stung a bit to be called a “contractor.” But I could live with it. In fact, on the surface my patient’s analogy was quite good. Hospitalists do swoop in and fix patients’ problems only to then leave their lives, most often for good. It was only after a few days that her statement started to sour in my amygdala.

Habitual tardiness, sketchy response times, vague payment structures, lack of transparency in pricing, pricing errors into the cost of the job—I don’t think the analogy was intended to be so perceptive. I and the healthcare system within which I work really had adopted some of the less-desirable attributes of the contracting world.

I usually tell patients I’ll be back in an hour to give them their test results, knowing that I’m on “doctor time” and this could mean several hours or more. My tardiness usually results from being delayed while caring for another patient—but it’s all the same to the patient left waiting. Trying to build in cushion time for these unforeseen delays leaves a patient with a disagreeable contractor-like window of time to wait. For those who want to have their family at our daily rounds, an “I’ll come see you in the morning” is not just unhelpful—it disrespects the importance of their time.

Then there’s our payment system. It’s a mystery even to me: $12 aspirins, $100,000 cancer drugs, intentionally inflated professional fees and hospital bills that aren’t expected to be paid in full (unless the patient lacks an insurer to negotiate a lower price when they ironically are expected to foot the entire bill). All of which is made worse by the lack of transparency in our pricing. Patients (and most often I) simply are not privy to the costs of various tests and interventions. And, costs for the same procedure often differ among hospitals.

Few of us would contract for work without playing a role in choosing the supplies and knowing the rough cost of the materials. Yet that’s the situation our patients find themselves in daily.

Finally, expecting patients or their insurers to pay for my mistakes is not fair. I recognize there are adverse events that are unavoidable and should be reimbursed. However, many errors are as avoidable as being careful not to cut through a working pipe. Payment for these outcomes should be shouldered by the health system—not the patient.

I limped through the next few days re-examining my patient interactions. I licked my wounds, vowing to eschew those traits that so offend me as a consumer. I might not be able to repair a broken healthcare system, but I can refurbish the way I interact with my patients by being timely and responsive and not underestimating the effect of poor customer service. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It was probably just the ramblings of a mad woman. Only she wasn’t mad, so I searched for a hint of delirium. Nothing. She was mentally fit and lucid—perhaps too lucid. Could it be true … had I become my archenemy?

To decide, I put her utterance to the test through the Kubler-Ross obstacle course, hopping the denial hurdle, quick-footing through the anger tire course, wading through the bargaining pool, and finally swinging safely across the depression crevasse to acceptance.

She was my eighth patient that day, a 78-year-old woman admitted to the orthopedic service with a hip fracture. I was asked to do a preoperative risk assessment and comanage her diabetes and heart failure. During our introductions she asked what kind of doctor I was.

“A hospitalist,” I replied.

“Oh … that’s nice,” she answered, her furrowed eyebrow transforming her crow’s feet into a question mark.

“You know, a doctor who only cares for patients in the hospital,” I clarified. “I just take care of your acute problems.”

“You think a broken hip is cute?”

“No, no, not ‘cute.’ Acute. You know, I only deal with your urgent problems. When you leave here you will go back to see your primary care doctor, who will follow up your hip fracture and your more chronic issues.”

That’s when she dropped the bomb.

“Oh, I see; you’re sort of like a contractor for my body then—just helping when things get broke.”

I should explain my aversion to this comment. Reared by a 10-thumbed father, I’m genetically incapable of curing even the simplest household hiccup. This doesn’t mean I haven’t or won’t try. In fact, I’m willing to try anything. My wife, however, is too smart to allow that. She knows that home improvement project plus me equals larger home improvement project. Combine this mathematical axiom with our turn-of-the-(20th)-century home, and it’s easy to see why I find myself betrothed in nearly continuous engagement with contractors.

But this is a marriage on the rocks. As dependent as I am on home contractors, I generally dislike working with them. They’re all fine people I’m sure, and truth be told most of them are quite skilled at their work. The problem is that they go about their job as if they are allergic to customer service.

The only contractors who are not perpetually late are those who won’t give you a time to meet. “I’ll meet you in the morning,” they’ll say, only to define morning as any time after the sun comes up.

Then there’s the estimate, which appears to be an approximation calculated in a cavernous ballpark using an underestimater. It’s also not exactly clear how or what goes into the calculation of an estimate.

I recently got a written estimate that read as follows: “Fix sink, $400.” When I asked what the $400 would go toward, I got the ever-so-helpful reply: “Fixing the sink.” I responded, “No, I mean, how much are the parts and the labor and things like that?” He gruffly countered, “Four hundred dollars.” Uncovering how he came up with this estimate was about as easy as solving a Rubik’s cube. I gave up trying—and eventually paid $550.

Another time, a contractor agreed to fix a plumbing leak in our upstairs bathroom that had caused water damage to our first-floor ceiling. While tearing out the floor to reach the leak, he mistakenly ran a circular saw through a pipe, causing a considerably larger gusher that quickly destroyed said ceiling.

I understand these things happen. However, imagine my surprise when the eventual project cost was more than twice the estimated cost. He explained that repairing the new water damage was quite expensive and accounted for the variance with the estimate. We “discussed” this development, during which time I explained to him in no uncertain terms what the temperature in hell would be when I paid for his mistake.

So, it stung a bit to be called a “contractor.” But I could live with it. In fact, on the surface my patient’s analogy was quite good. Hospitalists do swoop in and fix patients’ problems only to then leave their lives, most often for good. It was only after a few days that her statement started to sour in my amygdala.

Habitual tardiness, sketchy response times, vague payment structures, lack of transparency in pricing, pricing errors into the cost of the job—I don’t think the analogy was intended to be so perceptive. I and the healthcare system within which I work really had adopted some of the less-desirable attributes of the contracting world.

I usually tell patients I’ll be back in an hour to give them their test results, knowing that I’m on “doctor time” and this could mean several hours or more. My tardiness usually results from being delayed while caring for another patient—but it’s all the same to the patient left waiting. Trying to build in cushion time for these unforeseen delays leaves a patient with a disagreeable contractor-like window of time to wait. For those who want to have their family at our daily rounds, an “I’ll come see you in the morning” is not just unhelpful—it disrespects the importance of their time.

Then there’s our payment system. It’s a mystery even to me: $12 aspirins, $100,000 cancer drugs, intentionally inflated professional fees and hospital bills that aren’t expected to be paid in full (unless the patient lacks an insurer to negotiate a lower price when they ironically are expected to foot the entire bill). All of which is made worse by the lack of transparency in our pricing. Patients (and most often I) simply are not privy to the costs of various tests and interventions. And, costs for the same procedure often differ among hospitals.

Few of us would contract for work without playing a role in choosing the supplies and knowing the rough cost of the materials. Yet that’s the situation our patients find themselves in daily.

Finally, expecting patients or their insurers to pay for my mistakes is not fair. I recognize there are adverse events that are unavoidable and should be reimbursed. However, many errors are as avoidable as being careful not to cut through a working pipe. Payment for these outcomes should be shouldered by the health system—not the patient.

I limped through the next few days re-examining my patient interactions. I licked my wounds, vowing to eschew those traits that so offend me as a consumer. I might not be able to repair a broken healthcare system, but I can refurbish the way I interact with my patients by being timely and responsive and not underestimating the effect of poor customer service. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Coat Tales

Russ Cucina, MD, MS, a hospitalist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, and a colleague once spent a week wearing pedometers on the job to study how much ground they covered in the course of managing their patient caseloads in a huge hospital like UCSF. The result: an average of four miles walked per day.

“The usual productivity infrastructure for physicians in their offices is simply not as available to hospitalists, or isn’t under our control,” Dr. Cucina says. There may be networked computer terminals throughout the hospital, but how many there are, how accessible they are, and how much competition there is for them varies. Hospitalists may have their own offices, desks or shared office space, depending on institutional commitments, but these may be a trek from patient care areas.

As a result, they must bring essential tools of their trade on their persons. Some carry a briefcase or wear a fanny pack, but more often these essential tools are stuffed into every available pocket of their medical lab coats.

Dr. Cucina’s short list of essentials is typical of working hospitalists. It includes his “smart phone,” combining a personal digital assistant (PDA) and cell phone, pens, a reflex hammer, a tuning fork for testing neurologic sensitivities, a stethoscope, swabs for sterilizing the stethoscope, a stash of large hospital gloves (which can be a hard size to find), and a bulky and awkward—but secure—prescription pad in a cardstock wrapper.

He also totes a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards held together with a steel ring—one card for each active patient, updated daily by hand with medication changes, lab results and other information provided by the residents. “I have tried higher-tech approaches,” he explains. “I am the hospital’s associate medical director for information technology, and I need to keep up to date and try new things, including the various applications for keeping patient lists on line. But nothing has yet beaten out hand-written index cards for efficiency and ease of use. The time it takes to input this information electronically just isn’t worth it.”

Hospitalists say additional medical tools, such as an otoscope or ophthalmoscope, could be helpful but may pile on too much bulk and weight. “I’m often challenged to find one on the floor when I really need it,” Dr. Cucina says. Portable scopes are also quite valuable and at some risk for disappearing from an unattended lab coat in the highly trafficked hospital setting.

PDA Is No Panacea

For many hospitalists, one key to efficient mobility on the job is the PDA or laptop computer, with basic references such as UpToDate, Epocrates, Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia, or the Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics, either loaded or accessed via the Internet. PDAs involve serious compromises balancing size and weight with ease of keyboard use, ease of reading the screen, and memory or processing speed. (See “Tackle Technology,” November 2007, p. 22 for a discussion of how hospitalists use portable computing devices on the job.)

“We’ve come a long way from tongue depressors and otoscopes,” says William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare’s large and expanding hospitalist group based at Temple University, Collegeville, Pa. “Some of us at Temple, depending on the service, carry one or more cell phones and between one and three pagers, in a pocket or attached to a belt.” The doctors may have their own PDAs, but Cogent no longer supplies them, having converted to a Web-based tool that offers a variety of practice management resources accessed by laptop computers via the Internet.

Dr. Cucina believes the technology is evolving toward a tablet device that will integrate more of the resource databases hospitalists need in their daily practice with other essential functions, such as lab results, billing, and communications with primary physicians—all in a user-friendly scale and format. In the meantime, there’s still a lot that has to be stuffed into pockets.

Some hospitalists also prefer to hold favorite reference resources, such as the pocket-sized Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy in their hands. That also involves tradeoffs, notes Michelle Pezzani, MD, hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif.

“I tried carrying a book bag over my shoulder, but I felt like a school kid,” Dr. Pezzani relates. “I also noticed that the more reference books I had stuffed into my pockets, the less confidence other people seemed to have in me as a physician.” Not to mention that her pockets ripped open from the weight. She even developed a sore neck from her ergonomically unbalanced, overstuffed lab coat.

“Although I love being a hospitalist, it’s getting to the point where I feel disorganized because I have no real home base,” Dr. Pezzani laments. She finds her hospitalist group’s shared office—a converted labor-and-delivery room with no windows and three desktop computers for nine doctors—less than ideal. She spends as little time as possible there.

“My life would be easier if I didn’t have to carry my office in my pockets—my ink-stained pockets,” she says. “I can’t carry my laptop around with me because of the neck pain, so I asked the hospital to give me a locker closer to the middle of the building. It has also become a kind of science for me to transfer a few personal essentials into a little satchel with a string that I wear around my neck,” since a purse is not feasible.

Love/Hate Situation

Dr. Cucina uses an online custom supplier of medical lab coats with extra, zippered pockets on the inside and outside. He’s careful not to let the lab coat of out his sight when he takes it off.

Randy Ferrance, MD, a hospitalist in internal medicine and pediatrics at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., acknowledges his own love-hate relationship with the lab coat. In his pockets, he carries a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards, an 8.5-by-11-inch hospital census sheet, folded over, a prescription pad, a highlighter pen and spare pens, the ubiquitous stethoscope, an EKG caliper, a reflex hammer with microfilament test for diabetes, and a pocket Sanford Guide.

“I’d love to ditch the lab coat,” Dr. Ferrance says. “I often take it off when I sit down and sometimes end up leaving it behind, such as in the medical dictation area. I never want to wear one when I’m talking to a child. But for a lot of families of patients who are critically ill, it is a symbol, almost like the armor of the knighthood of medicine. You have to read each family, but for some, you lose credibility when you take it off. They’re looking for everything that medicine can offer, and the lab coat gives them more confidence in you.”

Dr. Ferrance appreciates the smaller size of his 47-bed hospital, where he is never a long walk from anyplace. He frequently returns during the day to his office, which he doesn’t have to share with other doctors. He uses it for family conferences and to store larger manuals, his laptop, and diagnostic kits.

He also values his Treo Smart phone, which incorporates a variety of programs, including a drug reference, billing program, lab reports on active patients, pediatric growth chart program, pneumonia severity index calculator, a medical calculator, Geriatrics At Your Fingertips, the Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, the American Association of Pediatrics’ Redbook comprehensive online infectious disease resource, hospice eligibility criteria, a camera—“to take pictures of odd lesions”—and access to e-mail and sports scores.

Although a briefcase is one more thing to lug around and risk losing, Julia Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospital in Madison, says she carries a bag that is a woman’s version of a briefcase, with her laptop and active administrative files required for her growing administrative duties as director of an academic hospitalist group.

“There are advantages to being mobile, but disadvantages as well,” Dr. Wright says. “You just can’t get everything done. I get between 50 and 60 phone pages a day, and a lot of curbside consults, as well.” The medical center is restructuring teaching services so a hospitalist’s assigned patients would be more often concentrated in one area, with less running from floor to floor, as well as exploring new office facilities for the hospitalist group.

Currently, 11 University of Wisconsin hospitalists share a room with five cubicles. “I’ve put my pictures up on the wall anyway, and I keep my files, stapler, and office supplies there. A couple of my partners keep their reference books there. What I like about sharing space like this is it can help with communication and collegiality within the group. We do a lot of patient hand-offs there. But as we grow and it becomes more crowded, we’re going to need some more dedicated space.” TH

Larry Beresford is a medical writer based in California.

Russ Cucina, MD, MS, a hospitalist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, and a colleague once spent a week wearing pedometers on the job to study how much ground they covered in the course of managing their patient caseloads in a huge hospital like UCSF. The result: an average of four miles walked per day.

“The usual productivity infrastructure for physicians in their offices is simply not as available to hospitalists, or isn’t under our control,” Dr. Cucina says. There may be networked computer terminals throughout the hospital, but how many there are, how accessible they are, and how much competition there is for them varies. Hospitalists may have their own offices, desks or shared office space, depending on institutional commitments, but these may be a trek from patient care areas.

As a result, they must bring essential tools of their trade on their persons. Some carry a briefcase or wear a fanny pack, but more often these essential tools are stuffed into every available pocket of their medical lab coats.

Dr. Cucina’s short list of essentials is typical of working hospitalists. It includes his “smart phone,” combining a personal digital assistant (PDA) and cell phone, pens, a reflex hammer, a tuning fork for testing neurologic sensitivities, a stethoscope, swabs for sterilizing the stethoscope, a stash of large hospital gloves (which can be a hard size to find), and a bulky and awkward—but secure—prescription pad in a cardstock wrapper.

He also totes a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards held together with a steel ring—one card for each active patient, updated daily by hand with medication changes, lab results and other information provided by the residents. “I have tried higher-tech approaches,” he explains. “I am the hospital’s associate medical director for information technology, and I need to keep up to date and try new things, including the various applications for keeping patient lists on line. But nothing has yet beaten out hand-written index cards for efficiency and ease of use. The time it takes to input this information electronically just isn’t worth it.”

Hospitalists say additional medical tools, such as an otoscope or ophthalmoscope, could be helpful but may pile on too much bulk and weight. “I’m often challenged to find one on the floor when I really need it,” Dr. Cucina says. Portable scopes are also quite valuable and at some risk for disappearing from an unattended lab coat in the highly trafficked hospital setting.

PDA Is No Panacea

For many hospitalists, one key to efficient mobility on the job is the PDA or laptop computer, with basic references such as UpToDate, Epocrates, Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia, or the Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics, either loaded or accessed via the Internet. PDAs involve serious compromises balancing size and weight with ease of keyboard use, ease of reading the screen, and memory or processing speed. (See “Tackle Technology,” November 2007, p. 22 for a discussion of how hospitalists use portable computing devices on the job.)

“We’ve come a long way from tongue depressors and otoscopes,” says William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare’s large and expanding hospitalist group based at Temple University, Collegeville, Pa. “Some of us at Temple, depending on the service, carry one or more cell phones and between one and three pagers, in a pocket or attached to a belt.” The doctors may have their own PDAs, but Cogent no longer supplies them, having converted to a Web-based tool that offers a variety of practice management resources accessed by laptop computers via the Internet.

Dr. Cucina believes the technology is evolving toward a tablet device that will integrate more of the resource databases hospitalists need in their daily practice with other essential functions, such as lab results, billing, and communications with primary physicians—all in a user-friendly scale and format. In the meantime, there’s still a lot that has to be stuffed into pockets.

Some hospitalists also prefer to hold favorite reference resources, such as the pocket-sized Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy in their hands. That also involves tradeoffs, notes Michelle Pezzani, MD, hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif.

“I tried carrying a book bag over my shoulder, but I felt like a school kid,” Dr. Pezzani relates. “I also noticed that the more reference books I had stuffed into my pockets, the less confidence other people seemed to have in me as a physician.” Not to mention that her pockets ripped open from the weight. She even developed a sore neck from her ergonomically unbalanced, overstuffed lab coat.

“Although I love being a hospitalist, it’s getting to the point where I feel disorganized because I have no real home base,” Dr. Pezzani laments. She finds her hospitalist group’s shared office—a converted labor-and-delivery room with no windows and three desktop computers for nine doctors—less than ideal. She spends as little time as possible there.

“My life would be easier if I didn’t have to carry my office in my pockets—my ink-stained pockets,” she says. “I can’t carry my laptop around with me because of the neck pain, so I asked the hospital to give me a locker closer to the middle of the building. It has also become a kind of science for me to transfer a few personal essentials into a little satchel with a string that I wear around my neck,” since a purse is not feasible.

Love/Hate Situation

Dr. Cucina uses an online custom supplier of medical lab coats with extra, zippered pockets on the inside and outside. He’s careful not to let the lab coat of out his sight when he takes it off.

Randy Ferrance, MD, a hospitalist in internal medicine and pediatrics at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., acknowledges his own love-hate relationship with the lab coat. In his pockets, he carries a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards, an 8.5-by-11-inch hospital census sheet, folded over, a prescription pad, a highlighter pen and spare pens, the ubiquitous stethoscope, an EKG caliper, a reflex hammer with microfilament test for diabetes, and a pocket Sanford Guide.

“I’d love to ditch the lab coat,” Dr. Ferrance says. “I often take it off when I sit down and sometimes end up leaving it behind, such as in the medical dictation area. I never want to wear one when I’m talking to a child. But for a lot of families of patients who are critically ill, it is a symbol, almost like the armor of the knighthood of medicine. You have to read each family, but for some, you lose credibility when you take it off. They’re looking for everything that medicine can offer, and the lab coat gives them more confidence in you.”

Dr. Ferrance appreciates the smaller size of his 47-bed hospital, where he is never a long walk from anyplace. He frequently returns during the day to his office, which he doesn’t have to share with other doctors. He uses it for family conferences and to store larger manuals, his laptop, and diagnostic kits.

He also values his Treo Smart phone, which incorporates a variety of programs, including a drug reference, billing program, lab reports on active patients, pediatric growth chart program, pneumonia severity index calculator, a medical calculator, Geriatrics At Your Fingertips, the Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, the American Association of Pediatrics’ Redbook comprehensive online infectious disease resource, hospice eligibility criteria, a camera—“to take pictures of odd lesions”—and access to e-mail and sports scores.

Although a briefcase is one more thing to lug around and risk losing, Julia Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospital in Madison, says she carries a bag that is a woman’s version of a briefcase, with her laptop and active administrative files required for her growing administrative duties as director of an academic hospitalist group.

“There are advantages to being mobile, but disadvantages as well,” Dr. Wright says. “You just can’t get everything done. I get between 50 and 60 phone pages a day, and a lot of curbside consults, as well.” The medical center is restructuring teaching services so a hospitalist’s assigned patients would be more often concentrated in one area, with less running from floor to floor, as well as exploring new office facilities for the hospitalist group.

Currently, 11 University of Wisconsin hospitalists share a room with five cubicles. “I’ve put my pictures up on the wall anyway, and I keep my files, stapler, and office supplies there. A couple of my partners keep their reference books there. What I like about sharing space like this is it can help with communication and collegiality within the group. We do a lot of patient hand-offs there. But as we grow and it becomes more crowded, we’re going to need some more dedicated space.” TH

Larry Beresford is a medical writer based in California.

Russ Cucina, MD, MS, a hospitalist at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center, and a colleague once spent a week wearing pedometers on the job to study how much ground they covered in the course of managing their patient caseloads in a huge hospital like UCSF. The result: an average of four miles walked per day.

“The usual productivity infrastructure for physicians in their offices is simply not as available to hospitalists, or isn’t under our control,” Dr. Cucina says. There may be networked computer terminals throughout the hospital, but how many there are, how accessible they are, and how much competition there is for them varies. Hospitalists may have their own offices, desks or shared office space, depending on institutional commitments, but these may be a trek from patient care areas.

As a result, they must bring essential tools of their trade on their persons. Some carry a briefcase or wear a fanny pack, but more often these essential tools are stuffed into every available pocket of their medical lab coats.

Dr. Cucina’s short list of essentials is typical of working hospitalists. It includes his “smart phone,” combining a personal digital assistant (PDA) and cell phone, pens, a reflex hammer, a tuning fork for testing neurologic sensitivities, a stethoscope, swabs for sterilizing the stethoscope, a stash of large hospital gloves (which can be a hard size to find), and a bulky and awkward—but secure—prescription pad in a cardstock wrapper.

He also totes a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards held together with a steel ring—one card for each active patient, updated daily by hand with medication changes, lab results and other information provided by the residents. “I have tried higher-tech approaches,” he explains. “I am the hospital’s associate medical director for information technology, and I need to keep up to date and try new things, including the various applications for keeping patient lists on line. But nothing has yet beaten out hand-written index cards for efficiency and ease of use. The time it takes to input this information electronically just isn’t worth it.”

Hospitalists say additional medical tools, such as an otoscope or ophthalmoscope, could be helpful but may pile on too much bulk and weight. “I’m often challenged to find one on the floor when I really need it,” Dr. Cucina says. Portable scopes are also quite valuable and at some risk for disappearing from an unattended lab coat in the highly trafficked hospital setting.

PDA Is No Panacea

For many hospitalists, one key to efficient mobility on the job is the PDA or laptop computer, with basic references such as UpToDate, Epocrates, Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia, or the Washington Manual of Medical Therapeutics, either loaded or accessed via the Internet. PDAs involve serious compromises balancing size and weight with ease of keyboard use, ease of reading the screen, and memory or processing speed. (See “Tackle Technology,” November 2007, p. 22 for a discussion of how hospitalists use portable computing devices on the job.)

“We’ve come a long way from tongue depressors and otoscopes,” says William Ford, MD, program medical director for Cogent Healthcare’s large and expanding hospitalist group based at Temple University, Collegeville, Pa. “Some of us at Temple, depending on the service, carry one or more cell phones and between one and three pagers, in a pocket or attached to a belt.” The doctors may have their own PDAs, but Cogent no longer supplies them, having converted to a Web-based tool that offers a variety of practice management resources accessed by laptop computers via the Internet.

Dr. Cucina believes the technology is evolving toward a tablet device that will integrate more of the resource databases hospitalists need in their daily practice with other essential functions, such as lab results, billing, and communications with primary physicians—all in a user-friendly scale and format. In the meantime, there’s still a lot that has to be stuffed into pockets.

Some hospitalists also prefer to hold favorite reference resources, such as the pocket-sized Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy in their hands. That also involves tradeoffs, notes Michelle Pezzani, MD, hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif.

“I tried carrying a book bag over my shoulder, but I felt like a school kid,” Dr. Pezzani relates. “I also noticed that the more reference books I had stuffed into my pockets, the less confidence other people seemed to have in me as a physician.” Not to mention that her pockets ripped open from the weight. She even developed a sore neck from her ergonomically unbalanced, overstuffed lab coat.

“Although I love being a hospitalist, it’s getting to the point where I feel disorganized because I have no real home base,” Dr. Pezzani laments. She finds her hospitalist group’s shared office—a converted labor-and-delivery room with no windows and three desktop computers for nine doctors—less than ideal. She spends as little time as possible there.

“My life would be easier if I didn’t have to carry my office in my pockets—my ink-stained pockets,” she says. “I can’t carry my laptop around with me because of the neck pain, so I asked the hospital to give me a locker closer to the middle of the building. It has also become a kind of science for me to transfer a few personal essentials into a little satchel with a string that I wear around my neck,” since a purse is not feasible.

Love/Hate Situation

Dr. Cucina uses an online custom supplier of medical lab coats with extra, zippered pockets on the inside and outside. He’s careful not to let the lab coat of out his sight when he takes it off.

Randy Ferrance, MD, a hospitalist in internal medicine and pediatrics at Riverside Tappahannock Hospital in Tappahannock, Va., acknowledges his own love-hate relationship with the lab coat. In his pockets, he carries a stack of 3-by-5-inch index cards, an 8.5-by-11-inch hospital census sheet, folded over, a prescription pad, a highlighter pen and spare pens, the ubiquitous stethoscope, an EKG caliper, a reflex hammer with microfilament test for diabetes, and a pocket Sanford Guide.

“I’d love to ditch the lab coat,” Dr. Ferrance says. “I often take it off when I sit down and sometimes end up leaving it behind, such as in the medical dictation area. I never want to wear one when I’m talking to a child. But for a lot of families of patients who are critically ill, it is a symbol, almost like the armor of the knighthood of medicine. You have to read each family, but for some, you lose credibility when you take it off. They’re looking for everything that medicine can offer, and the lab coat gives them more confidence in you.”

Dr. Ferrance appreciates the smaller size of his 47-bed hospital, where he is never a long walk from anyplace. He frequently returns during the day to his office, which he doesn’t have to share with other doctors. He uses it for family conferences and to store larger manuals, his laptop, and diagnostic kits.

He also values his Treo Smart phone, which incorporates a variety of programs, including a drug reference, billing program, lab reports on active patients, pediatric growth chart program, pneumonia severity index calculator, a medical calculator, Geriatrics At Your Fingertips, the Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers, the American Association of Pediatrics’ Redbook comprehensive online infectious disease resource, hospice eligibility criteria, a camera—“to take pictures of odd lesions”—and access to e-mail and sports scores.

Although a briefcase is one more thing to lug around and risk losing, Julia Wright, MD, director of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospital in Madison, says she carries a bag that is a woman’s version of a briefcase, with her laptop and active administrative files required for her growing administrative duties as director of an academic hospitalist group.

“There are advantages to being mobile, but disadvantages as well,” Dr. Wright says. “You just can’t get everything done. I get between 50 and 60 phone pages a day, and a lot of curbside consults, as well.” The medical center is restructuring teaching services so a hospitalist’s assigned patients would be more often concentrated in one area, with less running from floor to floor, as well as exploring new office facilities for the hospitalist group.

Currently, 11 University of Wisconsin hospitalists share a room with five cubicles. “I’ve put my pictures up on the wall anyway, and I keep my files, stapler, and office supplies there. A couple of my partners keep their reference books there. What I like about sharing space like this is it can help with communication and collegiality within the group. We do a lot of patient hand-offs there. But as we grow and it becomes more crowded, we’re going to need some more dedicated space.” TH

Larry Beresford is a medical writer based in California.

The Patient Has Left the Building

The hospitalist service at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics in the Department of Medicine recently admitted a patient with altered sensorium, which the team determined most likely was narcotic-related. Going the extra distance, they did a spinal tap to rule out meningitis.

Within a day of changing the medication, the patient got better and was ready for discharge. However, says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of the Madison-based service, an important test remained from the spinal tap. “We thought that those results would not change the medical management of the case, but we knew if it were positive, it would be a big deal,” she recalls.

Not all medical-legal experts would agree the responsibility for patient care ends when patients leave the hospital. Often there are extenuating circumstances that may warrant the hospitalist’s continued communication and contact with patients and/or their providers and caregivers. Although there are no universally accepted standards of care that define these post-discharge issues, several hospitalists recently discussed their institutions’ and groups’ guiding principles for managing the nuances of post-discharge protocol.

Who’s Responsible?

Hospitalist Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee and also has been investigating pre- and post-discharge interventions through a grant-funded project from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) called “Project RED” (the Re-Engineered Discharge, online at www.ahrq.gov/qual/pips).

One reason the post-discharge period is a “gray zone” of responsibility for care, he believes, is that the hospital system was designed to have a finite endpoint—the discharge. “This ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality has existed forever in the inpatient service, but it has become more highlighted in the post-hospitalist era,” he notes.

That mentality can sometimes take over in the hospitalists’ minds. “I think a lot of hospitalists are burying their heads [in the sand] about how these patients are being sent home and the chances for miscommunication and a ‘bounce-back,’ ” notes David Yu, MD, FACP, ABIM, medical director of hospitalist services, Decatur Memorial Hospital, Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. “This is going to be more of an issue as hospitalists become increasingly busy. The temptation is to squeeze time on discharges, because it takes an effort to reconcile medications and tie up loose ends at time of discharge. It is not acceptable to write, ‘resume current medications and follow up with PCP’ and think the job is done. It is magical thinking that discharge medications and follow-up instructions will be figured out somehow by the patient and discharging nurse.”

Cover the Gray Zone

Hospitalists describe differing approaches to ensuring patients get the care they need when they leave the hospital.

In the case of the UWHC patient who wanted to leave the hospital, the hospitalist team arranged to stay in touch with the patient. They watched for the test results during the next 24 hours. When the test came back positive, they called the patient back to the hospital, and began treatment.

“Although tracking test results may be out of the hospitalist’s purview, I think we have a strong obligation to make sure we look at some of that data,” Dr. Wright says. “I think there has to be some redundancy, otherwise, the patient probably would not have seen the primary care physician in time and would have become more ill.”

Attention to detail before discharge can avoid problems in the post-discharge period. Partnering with the pharmacy to achieve medication reconciliation has been shown to reduce risk of readmission, notes Tom Bookwalter, PharmD, associate professor of health sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine and formerly clinical pharmacist there. Using standardized templates and electronic medical records (EMR), hospitalists at many academic centers can furnish real-time discharge summaries to patients’ primary care physicians.

Dr. Yu is especially proud of the EMR system at his institution, by which discharge summaries are faxed to the primary care physician (PCP) in real time. “A patient can call their primary care physician right after discharge, and that physician will know exactly what happened during the hospital course, and what the medications and the discharge plan are,” he explains.

In addition, computerized entry and transmission eliminates the risk of error introduced when handwritten instructions are given to patients. “We believe that communication is the ‘mother’s milk’ of the hospitalist,” Dr. Yu says. Accordingly, his hospitalist service also makes a courtesy call to the PCP following transmission of the EMR for the patient.

Attorney Patrick T. O’Rourke of the Office of University Counsel at Colorado University in Denver and legal columnist for The Hospitalist, advises how to avoid inviting unintended legal consequences. “It’s important for hospitalists to understand that they are the conduit of information about what happened during the hospitalization,” he notes. “Failing to define everyone’s job in the discharge process can expose people to liability.”

In that vein, he urges hospitalists not to delegate the process of giving discharge instructions to the patient. Patients should hear directly from the hospitalist about their condition, the recommended course of action, and how to respond in case of emergency post-discharge. When returning the patient to their regular physician, the hospitalist should also touch base with the patient’s physician via e-mail or telephone to prevent gaps in communication.

Other Strategies

If budgets allow, some groups employ ancillary staff who call patients after discharge.

Hospitalist David Grace, MD, area medical officer for the Schumacher Group, Hospital Medicine Division, in Lafayette, La., reports that having a practice coordinator who calls patients within 48 hours of discharge “adds one more layer of safety to the process.” “Yes” answers to some questions (e.g., “Have your symptoms worsened? Do you have any new symptoms?”) trigger follow-up calls to the on-call hospitalist to take appropriate steps. However, O’Rourke cautions that midlevel providers should possess adequate training to be able to act appropriately upon patients’ information.

Hospitalist Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, medical director at Riverside Tappahannock Hospice in Tappahannock, Va., agrees follow-up calls to patients are a good idea. “I think more aggressive follow up in the short term, and then turning the patient over, for continuity reasons, to their primary care physician as quickly as possible is very important.” His hospitalist group, comprising only four staff, struggles with having the time to devote to such activities. However, with an average inpatient age of 72, their patients often transition to home healthcare. His group enjoys an “excellent relationship” with all the area home health agencies. Those agencies are asked to call the hospitalist group during their first visit with the patient, in addition to sending their usual report to the primary care physician. “At that first home health visit, we consider ourselves still responsible for the patient,” he says.

Beyond Liability Protection

Adhering to the “higher standard” of patient safety can improve transitions of care even further, Dr. Greenwald believes. Such actions might include a mechanism for patients to reach a member of the hospitalist team (nurse, pharmacist or physician) if they have post-discharge concerns; empowering patients and family members to know what to do if an adverse event occurs; and enabling patients to have copies of their own medical information (discharge summary, lab tests, medication reconciliations).

“In addition, we need to involve the nonmedical caregivers who are going to help the patient recuperate,” he asserts. Physicians can educate patients and their caregivers about what happened while they were in the hospital, what treatments are planned, and what information is pending at discharge. While these efforts might require that hospitalists shift their thinking about doctor-patient roles, they can help to create a more comprehensive approach to patient care.

Inherent Dangers

Ironically, what hospitalists do best—promote effective inpatient management—can also lead to a disconnect when the patient leaves the hospital. “Part of what we do, as hospitalists, is to drive down the patient’s length of stay and get them home sooner,” Dr. Grace says. “While unquestionably beneficial for a variety of reasons, it increases the chance that a patient can leave before a result comes back.”

“This change from the continuity of healthcare [provided by a physician who also saw his or her hospitalized patients] to a division of labor does have some inherent fragmentation,” agrees Dr. Wright. “We need to still look at the patient as a whole and be in communication with [our primary care colleagues] and supporting each other on both ends so that the patient does get this more comprehensive care.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a medical writer based in California.

The hospitalist service at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics in the Department of Medicine recently admitted a patient with altered sensorium, which the team determined most likely was narcotic-related. Going the extra distance, they did a spinal tap to rule out meningitis.

Within a day of changing the medication, the patient got better and was ready for discharge. However, says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of the Madison-based service, an important test remained from the spinal tap. “We thought that those results would not change the medical management of the case, but we knew if it were positive, it would be a big deal,” she recalls.

Not all medical-legal experts would agree the responsibility for patient care ends when patients leave the hospital. Often there are extenuating circumstances that may warrant the hospitalist’s continued communication and contact with patients and/or their providers and caregivers. Although there are no universally accepted standards of care that define these post-discharge issues, several hospitalists recently discussed their institutions’ and groups’ guiding principles for managing the nuances of post-discharge protocol.

Who’s Responsible?

Hospitalist Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee and also has been investigating pre- and post-discharge interventions through a grant-funded project from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) called “Project RED” (the Re-Engineered Discharge, online at www.ahrq.gov/qual/pips).

One reason the post-discharge period is a “gray zone” of responsibility for care, he believes, is that the hospital system was designed to have a finite endpoint—the discharge. “This ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality has existed forever in the inpatient service, but it has become more highlighted in the post-hospitalist era,” he notes.

That mentality can sometimes take over in the hospitalists’ minds. “I think a lot of hospitalists are burying their heads [in the sand] about how these patients are being sent home and the chances for miscommunication and a ‘bounce-back,’ ” notes David Yu, MD, FACP, ABIM, medical director of hospitalist services, Decatur Memorial Hospital, Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. “This is going to be more of an issue as hospitalists become increasingly busy. The temptation is to squeeze time on discharges, because it takes an effort to reconcile medications and tie up loose ends at time of discharge. It is not acceptable to write, ‘resume current medications and follow up with PCP’ and think the job is done. It is magical thinking that discharge medications and follow-up instructions will be figured out somehow by the patient and discharging nurse.”

Cover the Gray Zone

Hospitalists describe differing approaches to ensuring patients get the care they need when they leave the hospital.

In the case of the UWHC patient who wanted to leave the hospital, the hospitalist team arranged to stay in touch with the patient. They watched for the test results during the next 24 hours. When the test came back positive, they called the patient back to the hospital, and began treatment.

“Although tracking test results may be out of the hospitalist’s purview, I think we have a strong obligation to make sure we look at some of that data,” Dr. Wright says. “I think there has to be some redundancy, otherwise, the patient probably would not have seen the primary care physician in time and would have become more ill.”

Attention to detail before discharge can avoid problems in the post-discharge period. Partnering with the pharmacy to achieve medication reconciliation has been shown to reduce risk of readmission, notes Tom Bookwalter, PharmD, associate professor of health sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine and formerly clinical pharmacist there. Using standardized templates and electronic medical records (EMR), hospitalists at many academic centers can furnish real-time discharge summaries to patients’ primary care physicians.

Dr. Yu is especially proud of the EMR system at his institution, by which discharge summaries are faxed to the primary care physician (PCP) in real time. “A patient can call their primary care physician right after discharge, and that physician will know exactly what happened during the hospital course, and what the medications and the discharge plan are,” he explains.

In addition, computerized entry and transmission eliminates the risk of error introduced when handwritten instructions are given to patients. “We believe that communication is the ‘mother’s milk’ of the hospitalist,” Dr. Yu says. Accordingly, his hospitalist service also makes a courtesy call to the PCP following transmission of the EMR for the patient.

Attorney Patrick T. O’Rourke of the Office of University Counsel at Colorado University in Denver and legal columnist for The Hospitalist, advises how to avoid inviting unintended legal consequences. “It’s important for hospitalists to understand that they are the conduit of information about what happened during the hospitalization,” he notes. “Failing to define everyone’s job in the discharge process can expose people to liability.”

In that vein, he urges hospitalists not to delegate the process of giving discharge instructions to the patient. Patients should hear directly from the hospitalist about their condition, the recommended course of action, and how to respond in case of emergency post-discharge. When returning the patient to their regular physician, the hospitalist should also touch base with the patient’s physician via e-mail or telephone to prevent gaps in communication.

Other Strategies

If budgets allow, some groups employ ancillary staff who call patients after discharge.

Hospitalist David Grace, MD, area medical officer for the Schumacher Group, Hospital Medicine Division, in Lafayette, La., reports that having a practice coordinator who calls patients within 48 hours of discharge “adds one more layer of safety to the process.” “Yes” answers to some questions (e.g., “Have your symptoms worsened? Do you have any new symptoms?”) trigger follow-up calls to the on-call hospitalist to take appropriate steps. However, O’Rourke cautions that midlevel providers should possess adequate training to be able to act appropriately upon patients’ information.

Hospitalist Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, medical director at Riverside Tappahannock Hospice in Tappahannock, Va., agrees follow-up calls to patients are a good idea. “I think more aggressive follow up in the short term, and then turning the patient over, for continuity reasons, to their primary care physician as quickly as possible is very important.” His hospitalist group, comprising only four staff, struggles with having the time to devote to such activities. However, with an average inpatient age of 72, their patients often transition to home healthcare. His group enjoys an “excellent relationship” with all the area home health agencies. Those agencies are asked to call the hospitalist group during their first visit with the patient, in addition to sending their usual report to the primary care physician. “At that first home health visit, we consider ourselves still responsible for the patient,” he says.

Beyond Liability Protection

Adhering to the “higher standard” of patient safety can improve transitions of care even further, Dr. Greenwald believes. Such actions might include a mechanism for patients to reach a member of the hospitalist team (nurse, pharmacist or physician) if they have post-discharge concerns; empowering patients and family members to know what to do if an adverse event occurs; and enabling patients to have copies of their own medical information (discharge summary, lab tests, medication reconciliations).

“In addition, we need to involve the nonmedical caregivers who are going to help the patient recuperate,” he asserts. Physicians can educate patients and their caregivers about what happened while they were in the hospital, what treatments are planned, and what information is pending at discharge. While these efforts might require that hospitalists shift their thinking about doctor-patient roles, they can help to create a more comprehensive approach to patient care.

Inherent Dangers

Ironically, what hospitalists do best—promote effective inpatient management—can also lead to a disconnect when the patient leaves the hospital. “Part of what we do, as hospitalists, is to drive down the patient’s length of stay and get them home sooner,” Dr. Grace says. “While unquestionably beneficial for a variety of reasons, it increases the chance that a patient can leave before a result comes back.”

“This change from the continuity of healthcare [provided by a physician who also saw his or her hospitalized patients] to a division of labor does have some inherent fragmentation,” agrees Dr. Wright. “We need to still look at the patient as a whole and be in communication with [our primary care colleagues] and supporting each other on both ends so that the patient does get this more comprehensive care.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a medical writer based in California.

The hospitalist service at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics in the Department of Medicine recently admitted a patient with altered sensorium, which the team determined most likely was narcotic-related. Going the extra distance, they did a spinal tap to rule out meningitis.

Within a day of changing the medication, the patient got better and was ready for discharge. However, says Julia S. Wright, MD, director of the Madison-based service, an important test remained from the spinal tap. “We thought that those results would not change the medical management of the case, but we knew if it were positive, it would be a big deal,” she recalls.

Not all medical-legal experts would agree the responsibility for patient care ends when patients leave the hospital. Often there are extenuating circumstances that may warrant the hospitalist’s continued communication and contact with patients and/or their providers and caregivers. Although there are no universally accepted standards of care that define these post-discharge issues, several hospitalists recently discussed their institutions’ and groups’ guiding principles for managing the nuances of post-discharge protocol.

Who’s Responsible?

Hospitalist Jeffrey Greenwald, MD, associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine, is a member of SHM’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee and also has been investigating pre- and post-discharge interventions through a grant-funded project from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) called “Project RED” (the Re-Engineered Discharge, online at www.ahrq.gov/qual/pips).

One reason the post-discharge period is a “gray zone” of responsibility for care, he believes, is that the hospital system was designed to have a finite endpoint—the discharge. “This ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality has existed forever in the inpatient service, but it has become more highlighted in the post-hospitalist era,” he notes.

That mentality can sometimes take over in the hospitalists’ minds. “I think a lot of hospitalists are burying their heads [in the sand] about how these patients are being sent home and the chances for miscommunication and a ‘bounce-back,’ ” notes David Yu, MD, FACP, ABIM, medical director of hospitalist services, Decatur Memorial Hospital, Decatur, Ill., and clinical assistant professor of family and community medicine, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine. “This is going to be more of an issue as hospitalists become increasingly busy. The temptation is to squeeze time on discharges, because it takes an effort to reconcile medications and tie up loose ends at time of discharge. It is not acceptable to write, ‘resume current medications and follow up with PCP’ and think the job is done. It is magical thinking that discharge medications and follow-up instructions will be figured out somehow by the patient and discharging nurse.”

Cover the Gray Zone

Hospitalists describe differing approaches to ensuring patients get the care they need when they leave the hospital.

In the case of the UWHC patient who wanted to leave the hospital, the hospitalist team arranged to stay in touch with the patient. They watched for the test results during the next 24 hours. When the test came back positive, they called the patient back to the hospital, and began treatment.

“Although tracking test results may be out of the hospitalist’s purview, I think we have a strong obligation to make sure we look at some of that data,” Dr. Wright says. “I think there has to be some redundancy, otherwise, the patient probably would not have seen the primary care physician in time and would have become more ill.”

Attention to detail before discharge can avoid problems in the post-discharge period. Partnering with the pharmacy to achieve medication reconciliation has been shown to reduce risk of readmission, notes Tom Bookwalter, PharmD, associate professor of health sciences at the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine and formerly clinical pharmacist there. Using standardized templates and electronic medical records (EMR), hospitalists at many academic centers can furnish real-time discharge summaries to patients’ primary care physicians.

Dr. Yu is especially proud of the EMR system at his institution, by which discharge summaries are faxed to the primary care physician (PCP) in real time. “A patient can call their primary care physician right after discharge, and that physician will know exactly what happened during the hospital course, and what the medications and the discharge plan are,” he explains.

In addition, computerized entry and transmission eliminates the risk of error introduced when handwritten instructions are given to patients. “We believe that communication is the ‘mother’s milk’ of the hospitalist,” Dr. Yu says. Accordingly, his hospitalist service also makes a courtesy call to the PCP following transmission of the EMR for the patient.

Attorney Patrick T. O’Rourke of the Office of University Counsel at Colorado University in Denver and legal columnist for The Hospitalist, advises how to avoid inviting unintended legal consequences. “It’s important for hospitalists to understand that they are the conduit of information about what happened during the hospitalization,” he notes. “Failing to define everyone’s job in the discharge process can expose people to liability.”

In that vein, he urges hospitalists not to delegate the process of giving discharge instructions to the patient. Patients should hear directly from the hospitalist about their condition, the recommended course of action, and how to respond in case of emergency post-discharge. When returning the patient to their regular physician, the hospitalist should also touch base with the patient’s physician via e-mail or telephone to prevent gaps in communication.

Other Strategies

If budgets allow, some groups employ ancillary staff who call patients after discharge.

Hospitalist David Grace, MD, area medical officer for the Schumacher Group, Hospital Medicine Division, in Lafayette, La., reports that having a practice coordinator who calls patients within 48 hours of discharge “adds one more layer of safety to the process.” “Yes” answers to some questions (e.g., “Have your symptoms worsened? Do you have any new symptoms?”) trigger follow-up calls to the on-call hospitalist to take appropriate steps. However, O’Rourke cautions that midlevel providers should possess adequate training to be able to act appropriately upon patients’ information.

Hospitalist Randy Ferrance, DC, MD, medical director at Riverside Tappahannock Hospice in Tappahannock, Va., agrees follow-up calls to patients are a good idea. “I think more aggressive follow up in the short term, and then turning the patient over, for continuity reasons, to their primary care physician as quickly as possible is very important.” His hospitalist group, comprising only four staff, struggles with having the time to devote to such activities. However, with an average inpatient age of 72, their patients often transition to home healthcare. His group enjoys an “excellent relationship” with all the area home health agencies. Those agencies are asked to call the hospitalist group during their first visit with the patient, in addition to sending their usual report to the primary care physician. “At that first home health visit, we consider ourselves still responsible for the patient,” he says.

Beyond Liability Protection

Adhering to the “higher standard” of patient safety can improve transitions of care even further, Dr. Greenwald believes. Such actions might include a mechanism for patients to reach a member of the hospitalist team (nurse, pharmacist or physician) if they have post-discharge concerns; empowering patients and family members to know what to do if an adverse event occurs; and enabling patients to have copies of their own medical information (discharge summary, lab tests, medication reconciliations).

“In addition, we need to involve the nonmedical caregivers who are going to help the patient recuperate,” he asserts. Physicians can educate patients and their caregivers about what happened while they were in the hospital, what treatments are planned, and what information is pending at discharge. While these efforts might require that hospitalists shift their thinking about doctor-patient roles, they can help to create a more comprehensive approach to patient care.

Inherent Dangers

Ironically, what hospitalists do best—promote effective inpatient management—can also lead to a disconnect when the patient leaves the hospital. “Part of what we do, as hospitalists, is to drive down the patient’s length of stay and get them home sooner,” Dr. Grace says. “While unquestionably beneficial for a variety of reasons, it increases the chance that a patient can leave before a result comes back.”

“This change from the continuity of healthcare [provided by a physician who also saw his or her hospitalized patients] to a division of labor does have some inherent fragmentation,” agrees Dr. Wright. “We need to still look at the patient as a whole and be in communication with [our primary care colleagues] and supporting each other on both ends so that the patient does get this more comprehensive care.” TH

Gretchen Henkel is a medical writer based in California.

Do post-discharge telephone calls to patients reduce the rate of complications?

Case

A 75-year-old male with history of diabetes and heart disease is discharged from the hospital after treatment for pneumonia. He has eight medications on his discharge list and is given two new prescriptions at discharge. He has a primary care provider but will not be able to see her until three weeks after discharge. Will a follow-up call decrease potential complications?

Overview

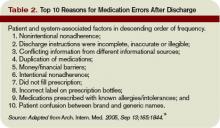

Medication errors are prevalent, especially during the transition period from discharge to follow-up with primary care physicians. There are more than 700,000 emergency department (ED) visits each year for adverse drug events with nearly 120,000 of these episodes resulting in hospitalization.1

The likelihood of an adverse drug event increases in patients using more than five medications and when there is a lack of understanding of how and why they are taking certain medications, scenarios common on hospital discharge.2 Studies evaluating effective means to reduce medication errors during transitions out of the hospital offer few solutions. One effective method, however, appears to be follow-up telephone calls.

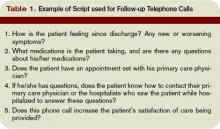

Telephone calls have been looked at in multiple studies and usually are performed in the studies by nurses, nurse practitioners, or pharmacists and occur within days of discharge from the hospital. These calls offer a mechanism to provide answers to questions about their medical condition or medications.

Review of the Data

There is a wide range of studies evaluating the benefit of a post-discharge telephone call. Unfortunately, most of the data are of low methodological quality with low patient numbers and high risk of bias.3

Much of the data are divided into subgroups of patients, including ED patients, cardiac patients, surgical patients, medicine patients, and other small groups. The end points also vary and examine areas such as patient satisfaction, reduction in medication errors, and effect on readmissions or repeat ED visits. The bulk of studies used a standardized script. These calls lasted only minutes, which could make it user-friendly, especially for a busy hospitalist’s schedule. Unfortunately, the effect of these interventions is mixed.

With ED patients, phone calls have been shown to be an effective means of communication between patients and physicians. In a study of 297 patients, the authors were only able to reach half the patients but still were able to identify medical problems needing referral or further intervention in 37% of the patients contacted.4 Another two studies revealed similar results with approximately 40% of the contacted patients requiring further clarification on their discharge instructions.5,6

Importantly, 95% of these patients felt the call was beneficial. Thus, more than one-third of patients discharged from an ED are likely to have problems and a follow-up telephone call offers an opportunity to intervene on these potential problems. Another ED study evaluated patients older than 75 and found a nurse liaison could effectively assess the complexity of a patient’s questions and appropriately advise them over the phone or triage them to the correct care provider for further care.7