User login

Positional Atrial Flutter?

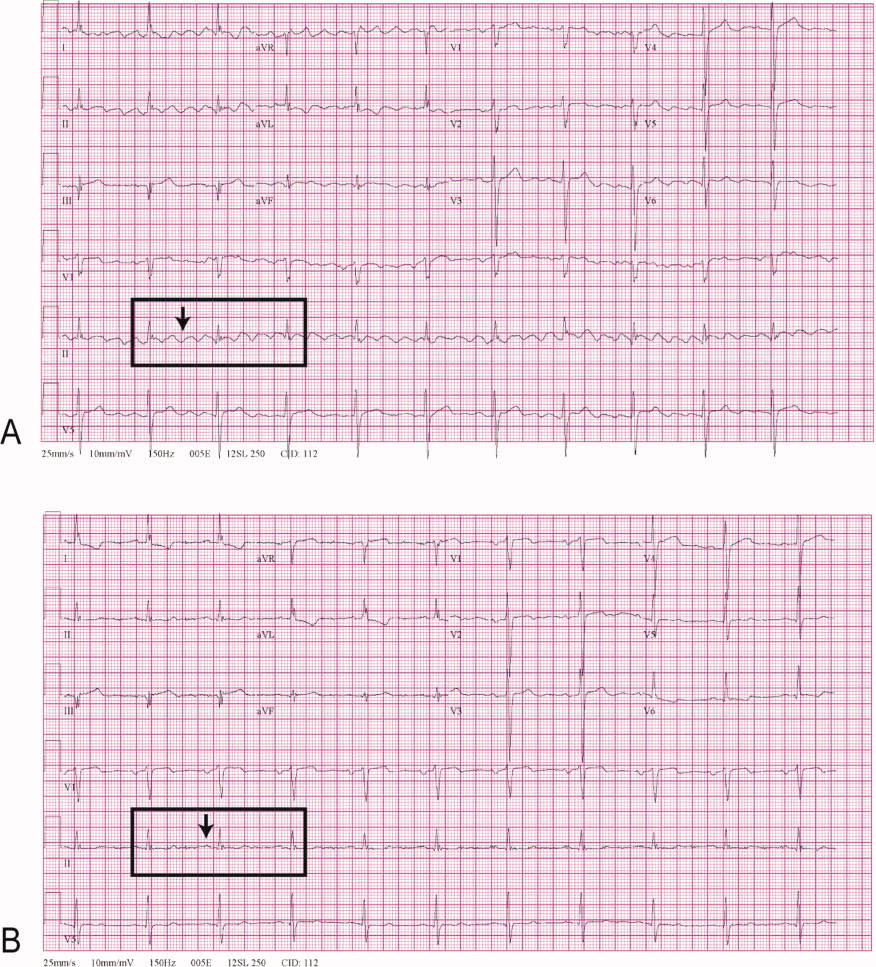

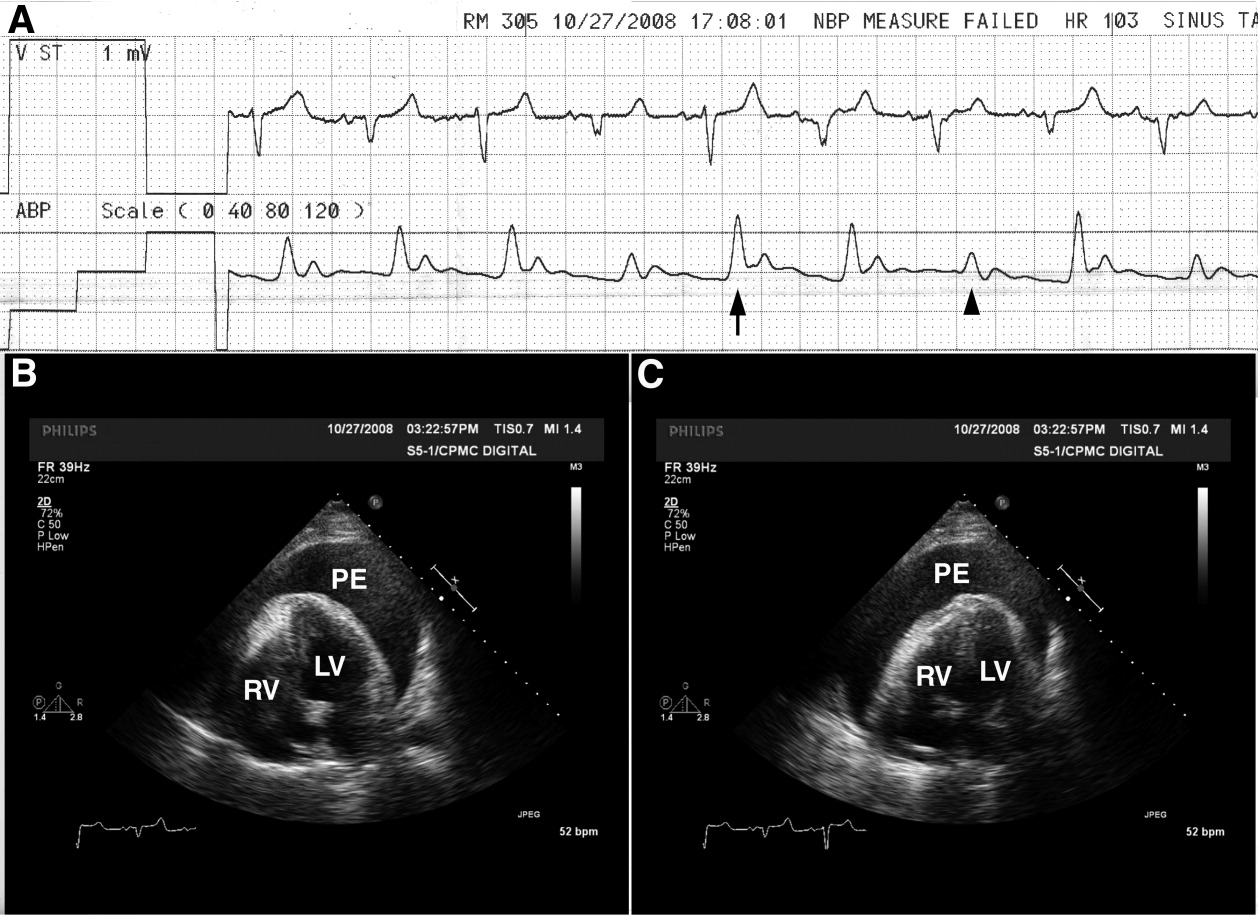

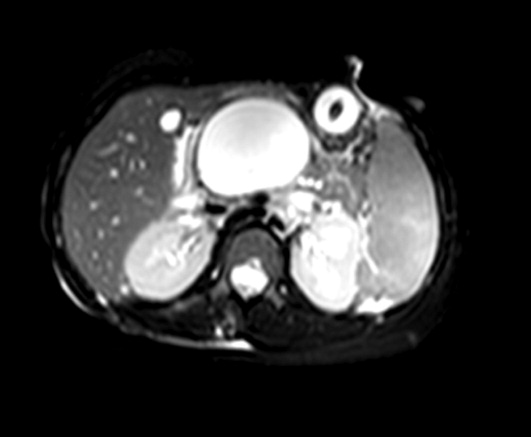

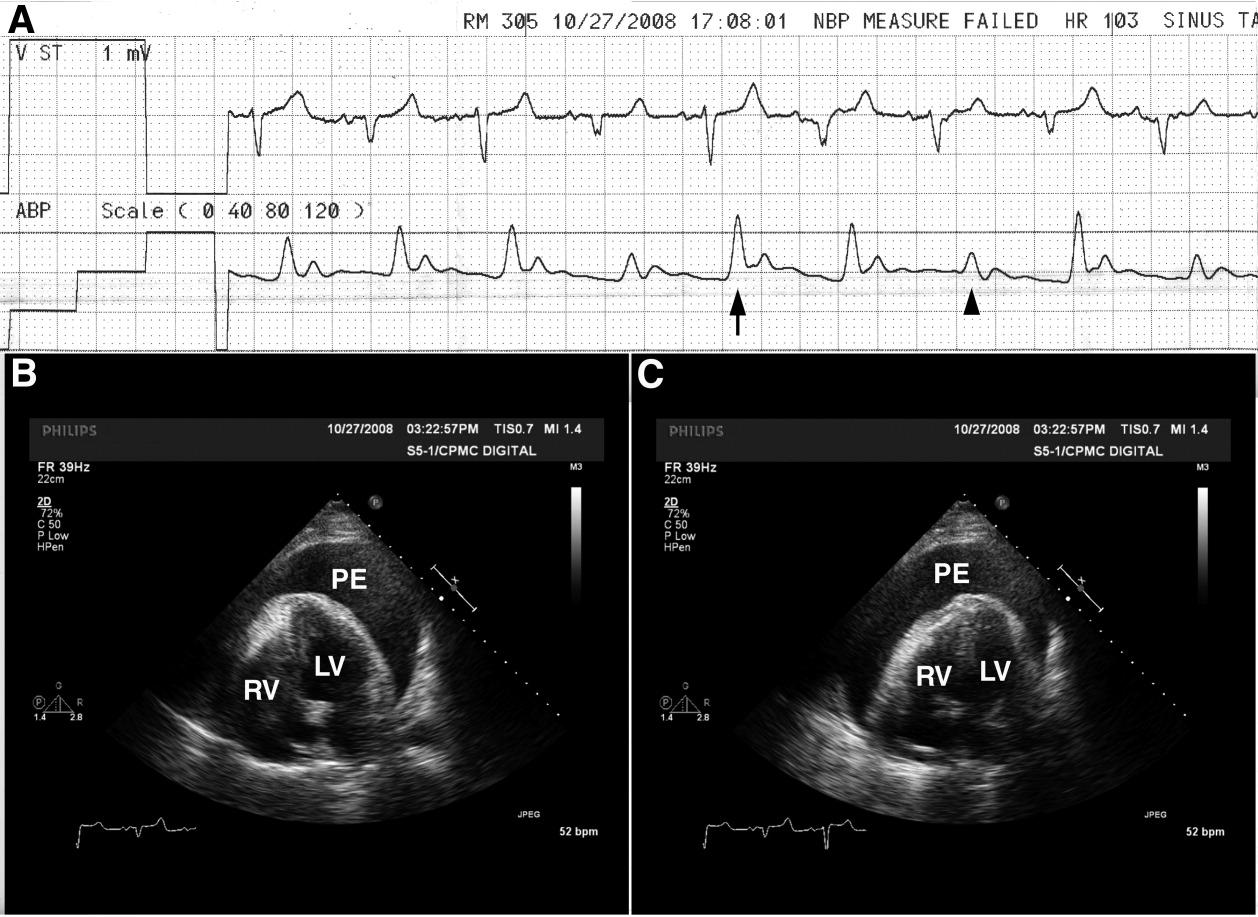

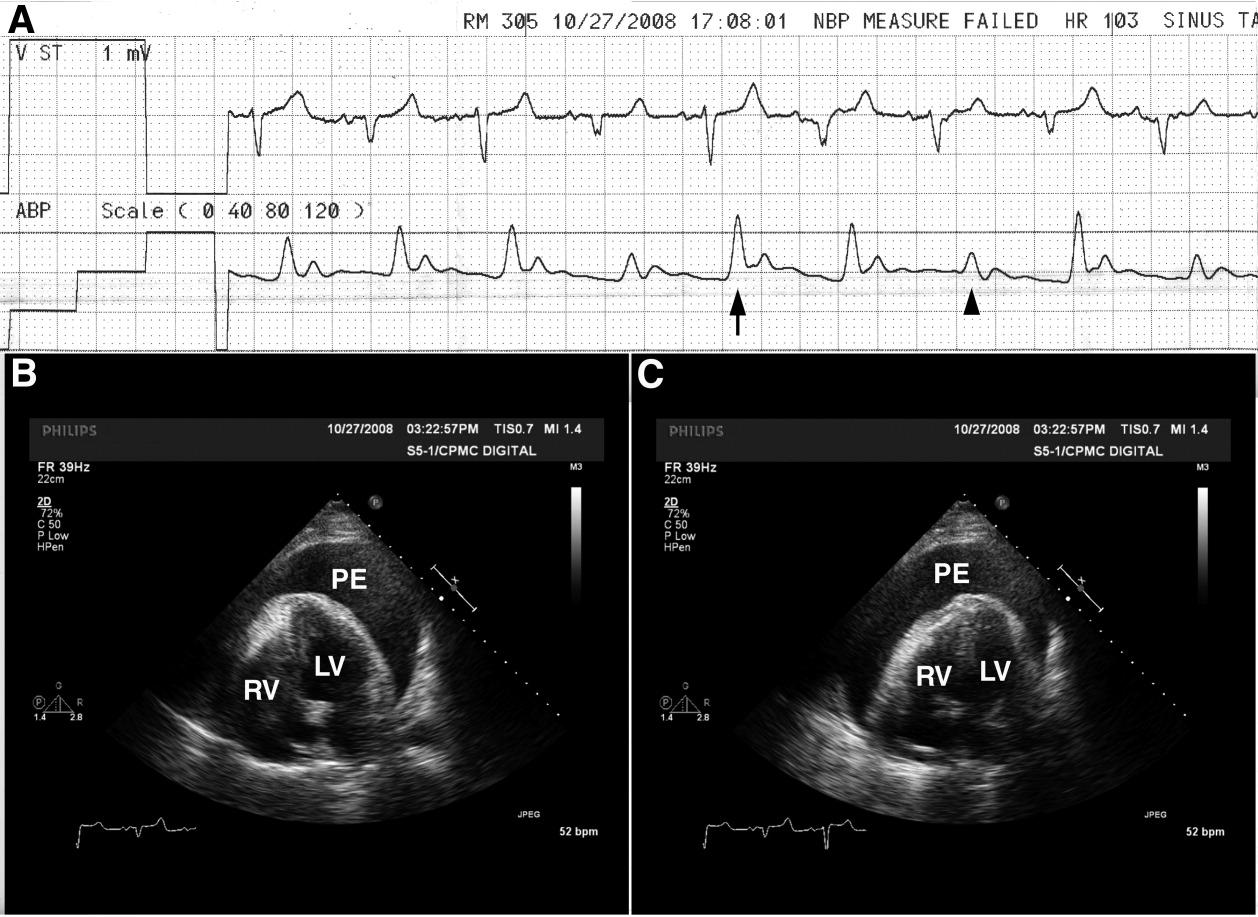

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

A 68‐year‐old man with a history of congestive heart failure and hypertension presented to the emergency department with fatigue and dyspnea of 3 weeks duration. Physical examination was consistent with heart failure. In addition, a right upper extremity resting tremor was noticed. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed an atrial flutter with a conduction ratio of 4:1 (Figure 1A). He denied palpitations or a previous history of atrial flutter/fibrillation. Unlike typical atrial flutter, these flutter like waves were distinctly absent in lead III, the only limb lead not connected to the right arm.

While holding the patient's right arm to control the tremor, a second ECG tracing was obtained. As expected the flutter like waves disappeared (Figure 1B). These ECG findings were attributed to the patient's tremor. A neurological consultation established a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. His congestive heart failure (CHF) was treated with increasing diuretics and appropriate treatment for Parkinson's disease was initiated.

Hospitalists and Quality of Care

Quality of care in US hospitals is inconsistent and often below accepted standards.1 This observation has catalyzed a number of performance measurement initiatives intended to publicize gaps and spur quality improvement.2 As the field has evolved, organizational factors such as teaching status, ownership model, nurse staffing levels, and hospital volume have been found to be associated with performance on quality measures.1, 3‐7 Hospitalists represent a more recent change in the organization of inpatient care8 that may impact hospital‐level performance. In fact, most hospitals provide financial support to hospitalists, not only for hopes of improving efficiency, but also for improving quality and safety.9

Only a few single‐site studies have examined the impact of hospitalists on quality of care for common medical conditions (ie, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction), and each has focused on patient‐level effects. Rifkin et al.10, 11 did not find differences between hospitalists' and nonhospitalists' patients in terms of pneumonia process measures. Roytman et al.12 found hospitalists more frequently prescribed afterload‐reducing agents for congestive heart failure (CHF), but other studies have shown no differences in care quality for heart failure.13, 14 Importantly, no studies have examined the role of hospitalists in the care of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In addition, studies have not addressed the effect of hospitalists at the hospital level to understand whether hospitalists have broader system‐level effects reflected by overall hospital performance.

We hypothesized that the presence of hospitalists within a hospital would be associated with improvements in hospital‐level adherence to publicly reported quality process measures, and having a greater percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists would be associated with improved performance. To test these hypotheses, we linked data from a statewide census of hospitalists with data collected as part of a hospital quality‐reporting initiative.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

We examined the performance of 209 hospitals (63% of all 334 non‐federal facilities in California) participating in the California Hospital Assessment and Reporting Taskforce (CHART) at the time of the survey. CHART is a voluntary quality reporting initiative that began publicly reporting hospital quality data in January 2006.

Hospital‐level Organizational, Case‐mix, and Quality Data

Hospital organizational characteristics (eg, bed size) were obtained from publicly available discharge and utilization data sets from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). We also linked hospital‐level patient‐mix data (eg, race) from these OSHPD files.

We obtained quality of care data from CHART for January 2006 through June 2007, the time period corresponding to the survey. Quality metrics included 16 measures collected by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.hhs.gov) and extensively used in quality research.1, 4, 13, 15‐17 Rather than define a single measure, we examined multiple process measures, anticipating differential impacts of hospitalists on various processes of care for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia. Measures were further divided among those that are usually measured upon initial presentation to the hospital and those that are measured throughout the entire hospitalization and discharge. This division reflects the division of care in the hospital, where emergency room physicians are likely to have a more critical role for admission processes.

Survey Process

We surveyed all nonfederal, acute care hospitals in California that participated in CHART.2 We first identified contacts at each site via professional society mailing lists. We then sent web‐based surveys to all with available email addresses and a fax/paper survey to the remainder. We surveyed individuals between October 2006 and April 2007 and repeated the process at intervals of 1 to 3 weeks. For remaining nonrespondents, we placed a direct call unless consent to survey had been specifically refused. We contacted the following persons in sequence: (1) hospital executives or administrative leaders; (2) hospital medicine department leaders; (3) admitting emergency room personnel or medical staff officers; and (4) hospital website information. In the case of multiple responses with disagreement, the hospital/hospitalist leader's response was treated as the primary source. At each step, respondents were asked to answer questions only if they had a direct working knowledge of their hospitalist services.

Survey Data

Our key survey question to all respondents included whether the respondents could confirm their hospitals had at least one hospitalist medicine group. Hospital leaders were also asked to participate in a more comprehensive survey of their organizational and clinical characteristics. Within the comprehensive survey, leaders also provided estimates of the percent of general medical patients admitted by hospitalists. This measure, used in prior surveys of hospital leaders,9 was intended to be an easily understood approximation of the intensity of hospitalist utilization in any given hospital. A more rigorous, direct measure was not feasible due to the complexity of obtaining admission data over such a large, diverse set of hospitals.

Process Performance Measures

AMI measures assessed at admission included aspirin and ‐blocker administration within 24 hours of arrival. AMI measures assessed at discharge included aspirin administration, ‐blocker administration, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE‐I) (or angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]) administration for left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. There were no CHF admission measures. CHF discharge measures included assessment of LV function, the use of an ACE‐I or ARB for LV dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. Pneumonia admission measures included the drawing of blood cultures prior to the receipt of antibiotics, timely administration of initial antibiotics (<8 hours), and antibiotics consistent with recommendations. Pneumonia discharge measures included pneumococcal vaccination, flu vaccination, and smoking cessation counseling.

For each performance measure, we quantified the percentage of missed quality opportunities, defined as the number of patients who did not receive a care process divided by the number of eligible patients, multiplied by 100. In addition, we calculated composite scores for admission and discharge measures across each condition. We summed the numerators and denominators of individual performance measures to generate a disease‐specific composite numerator and denominator. Both individual and composite scores were produced using methodology outlined by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.18 In order to retain as representative a sample of hospitals as possible, we calculated composite scores for hospitals that had a minimum of 25 observations in at least 2 of the quality indicators that made up each composite score.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi‐square tests, Student t tests, and Mann‐Whitney tests, where appropriate, to compare hospital‐level characteristics of hospitals that utilized hospitalists vs. those that did not. Similar analyses were performed among the subset of hospitals that utilized hospitalists. Among this subgroup of hospitals, we compared hospital‐level characteristics between hospitals that provided information regarding the percent of patients admitted by hospitalists vs. those who did not provide this information.

We used multivariable, generalized linear regression models to assess the relationship between having at least 1 hospitalist group and the percentage of missed quality of care measures. Because percentages were not normally distributed (ie, a majority of hospitals had few missed opportunities, while a minority had many), multivariable models employed log‐link functions with a gamma distribution.19, 20 Coefficients for our key predictor (presence of hospitalists) were transformed back to the original units (percentage of missed quality opportunities) so that a positive coefficient represented a higher number of quality measures missed relative to hospitals without hospitalists. Models were adjusted for factors previously reported to be associated with care quality. Hospital organizational characteristics included the number of beds, teaching status, registered nursing (RN) hours per adjusted patient day, and hospital ownership (for‐profit vs. not‐for‐profit). Hospital patient mix factors included annual percentage of admissions by insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, other), annual percentage of admissions by race (white vs. nonwhite), annual percentage of do‐not‐resuscitate status at admission, and mean diagnosis‐related group‐based case‐mix index.21 We additionally adjusted for the number of cardiac catheterizations, a measure that moderately correlates with the number of cardiologists and technology utilization.22‐24 In our subset analysis among those hospitals with hospitalists, our key predictor for regression analyses was the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. For ease of interpretation, the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists was centered on the mean across all respondent hospitals, and we report the effect of increasing by 10% the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. Models were adjusted for the same hospital organizational characteristics listed above. For those models, a positive coefficient also meant a higher number of measures missed.

For both sets of predictors, we additionally tested for the presence of interactions between the predictors and hospital bed size (both continuous as well as dichotomized at 150 beds) in composite measure performance, given the possibility that any hospitalist effect may be greater among smaller, resource‐limited hospitals. Tests for interaction were performed with the likelihood ratio test. In addition, to minimize any potential bias or loss of power that might result from limiting the analysis to hospitals with complete data, we used the multivariate imputation by chained equations method, as implemented in STATA 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), to create 10 imputed datasets.25 Imputation of missing values was restricted to confounding variables. Standard methods were then used to combine results over the 10 imputed datasets. We also applied Bonferroni corrections to composite measure tests based on the number of composites generated (n = 5). Thus, for the 5 inpatient composites created, standard definitions of significance (P 0.05) were corrected by dividing composite P values by 5, requiring P 0.01 for significance. The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco, approved the study. All analyses were performed using STATA 9.2.

Results

Characteristics of Participating Sites

There were 209 eligible hospitals. All 209 (100%) hospitals provided data about the presence or absence of hospitalists via at least 1 of our survey strategies. The majority of identification of hospitalist utilization was via contact with either hospital or hospitalist leaders, n = 147 (70.3%). Web‐sites informed hospitalist prevalence in only 3 (1.4%) hospitals. There were 8 (3.8%) occurrences of disagreement between sources, all of which had available hospital/hospitalist leader responses. Only 1 (0.5%) hospital did not have the minimum 25 patients eligible for any disease‐specific quality measures during the data reporting period. Collectively, the remaining 208 hospitals accounted for 81% of California's acute care hospital population.

Comparisons of Sites With Hospitalists and Those Without

A total of 170 hospitals (82%) participating in CHART used hospitalists. Hospitals with and without hospitalists differed by a variety of characteristics (Table 1). Sites with hospitalists were larger, less likely to be for‐profit, had more registered nursing hours per day, and performed more cardiac catheterizations.

| Characteristic | Hospitals Without Hospitalists (n = 38) | Hospitals With Hospitalists (n = 170) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Number of beds, n (% of hospitals) | <0.001 | ||

| 0‐99 | 16 (42.1) | 14 (8.2) | |

| 100‐199 | 8 (21.1) | 44 (25.9) | |

| 200‐299 | 7 (18.4) | 42 (24.7) | |

| 300+ | 7 (18.4) | 70 (41.2) | |

| For profit, n (% of hospitals) | 9 (23.7) | 18 (10.6) | 0.03 |

| Teaching hospital, n (% of hospitals) | 7 (18.4) | 55 (32.4) | 0.09 |

| RN hours per adjusted patient day, number of hours (IQR) | 7.4 (5.7‐8.6) | 8.5 (7.4‐9.9) | <0.001 |

| Annual cardiac catheterizations, n (IQR) | 0 (0‐356) | 210 (0‐813) | 0.007 |

| Hospital total census days, n (IQR) | 37161 (14910‐59750) | 60626 (34402‐87950) | <0.001 |

| ICU total census, n (IQR) | 2193 (1132‐4289) | 3855 (2489‐6379) | <0.001 |

| Medicare insurance, % patients (IQR) | 36.9 (28.5‐48.0) | 35.3(28.2‐44.3) | 0.95 |

| Medicaid insurance, % patients (IQR) | 21.0 (12.7‐48.3) | 16.6 (5.6‐27.6) | 0.02 |

| Race, white, % patients (IQR) | 53.7 (26.0‐82.7) | 59.1 (45.6‐74.3) | 0.73 |

| DNR at admission, % patients (IQR) | 3.6 (2.0‐6.4) | 4.4 (2.7‐7.1) | 0.12 |

| Case‐mix index, index (IQR) | 1.05 (0.90‐1.21) | 1.13 (1.01‐1.26) | 0.11 |

Relationship Between Hospitalist Group Utilization and the Percentage of Missed Quality Opportunities

Table 2 shows the frequency of missed quality opportunities in sites with hospitalists compared to those without. In general, for both individual and composite measures of quality, multivariable adjustment modestly attenuated the observed differences between the 2 groups of hospitals. We present only the more conservative adjusted estimates.

| Quality Measure | Number of Hospitals | Adjusted Mean % Missed Quality Opportunities (95% CI) | Difference With Hospitalists | Relative % Change | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals Without Hospitalists | Hospitals With Hospitalists | |||||

| ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at admission | 193 | 3.7 (2.4‐5.1) | 3.4 (2.3‐4.4) | 0.3 | 10.0 | 0.44 |

| Beta‐blocker at admission | 186 | 7.8 (4.7‐10.9) | 6.4 (4.4‐8.3) | 1.4 | 18.3 | 0.19 |

| AMI admission composite | 186 | 5.5 (3.6‐7.5) | 4.8 (3.4‐6.1) | 0.7 | 14.3 | 0.26 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at discharge | 173 | 7.5 (4.5‐10.4) | 5.2 (3.4‐6.9) | 2.3 | 31.0 | 0.02 |

| Beta‐blocker at discharge | 179 | 6.6 (3.8‐9.4) | 5.9 (3.6‐8.2) | 0.7 | 9.6 | 0.54 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 119 | 20.7 (9.5‐31.8) | 11.8 (6.6‐17.0) | 8.9 | 43.0 | 0.006 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 193 | 3.8 (2.4‐5.1) | 3.4 (2.4‐4.4) | 0.4 | 10.0 | 0.44 |

| AMI hospital/discharge composite | 179 | 6.4 (4.1‐8.6) | 5.3 (3.7‐6.8) | 1.1 | 17.6 | 0.16 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Ejection fraction assessment | 208 | 12.6 (7.7‐17.6) | 6.5 (4.6‐8.4) | 6.1 | 48.2 | <0.001 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 201 | 14.7 (10.0‐19.4) | 12.9 (9.8‐16.1) | 1.8 | 12.1 | 0.31 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 168 | 9.1 (2.9‐15.4) | 9.0 (4.2‐13.8) | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.98 |

| CHF hospital/discharge composite | 201 | 12.2 (7.9‐16.5) | 8.2 (6.2‐10.2) | 4.0 | 33.1 | 0.006* |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Blood culture before antibiotics | 206 | 12.0 (9.1‐14.9) | 10.9 (8.8‐13.0) | 1.1 | 9.1 | 0.29 |

| Timing of antibiotics <8 hours | 208 | 5.8 (4.1‐7.5) | 6.2 (4.7‐7.7) | 0.4 | 6.9 | 0.56 |

| Initial antibiotic consistent with recommendations | 207 | 15.0 (11.6‐18.6) | 13.8 (10.9‐16.8) | 1.2 | 8.1 | 0.27 |

| Pneumonia admission composite | 207 | 10.5 (8.5‐12.5) | 9.9 (8.3‐11.5) | 0.6 | 5.9 | 0.37 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Pneumonia vaccine | 208 | 29.4 (19.5‐39.2) | 27.1 (19.9‐34.3) | 2.3 | 7.7 | 0.54 |

| Influenza vaccine | 207 | 36.9 (25.4‐48.4) | 35.0 (27.0‐43.1) | 1.9 | 5.2 | 0.67 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 196 | 15.4 (7.8‐23.1) | 13.9 (8.9‐18.9) | 1.5 | 10.2 | 0.59 |

| Pneumonia hospital/discharge composite | 207 | 29.6 (20.5‐38.7) | 27.3 (20.9‐33.6) | 2.3 | 7.8 | 0.51 |

Compared to hospitals without hospitalists, those with hospitalists did not have any statistically significant differences in the individual and composite admission measures for each of the disease processes. In contrast, there were statistically significant differences between hospitalist and nonhospitalist sites for many individual cardiac processes of care that typically occur after admission from the emergency room (ie, LV function assessment for CHF) or those that occurred at discharge (ie, aspirin and ACE‐I/ARB at discharge for AMI). Similarly, the composite discharge scores for AMI and CHF revealed better overall process measure performance at sites with hospitalists, although the AMI composite did not meet statistical significance. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the pneumonia process measures assessed at discharge. In addition, for composite measures there were no statistically significant interactions between hospitalist prevalence and bed size, although there was a trend (P = 0.06) for the CHF discharge composite, with a larger effect of hospitalists among smaller hospitals.

Percent of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists

Of the 171 hospitals with hospitalists, 71 (42%) estimated the percent of patients admitted by their hospitalist physicians. Among the respondents, the mean and median percentages of medical patients admitted by hospitalists were 51% (SD = 25%) and 49% (IQR = 30‐70%), respectively. Thirty hospitals were above the sample mean. Compared to nonrespondent sites, respondent hospitals took care of more white patients; otherwise, respondent and nonrespondent hospitals were similar in terms of bed size, location, performance across each measure, and other observable characteristics (Supporting Information, Appendix 1).

Relationship Between the Estimated Percentages of Medical Patients Admitted by Hospitalists and Missed Quality Opportunities

Table 3 displays the change in missed quality measures associated with each additional 10% of patients estimated to be admitted by hospitalists. A higher estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists was associated with statistically significant improvements in quality of care across a majority of individual measures and for all composite discharge measures regardless of condition. For example, every 10% increase in the mean estimated number of patients admitted by hospitalists was associated with a mean of 0.6% (P < 0.001), 0.5% (P = 0.004), and 1.5% (P = 0.006) fewer missed quality opportunities for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia discharge process measures composites, respectively. In addition, for these composite measures, there were no statistically significant interactions between the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and bed size (dichotomized at 150 beds), although there was a trend (P = 0.09) for the AMI discharge composite, with a larger effect of hospitalists among smaller hospitals.

| Quality Measure | Number of Hospitals | Adjusted % Missed Quality Opportunities (95% CI) | Difference With Hospitalists | Relative Percent Change | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Hospitals With Mean % of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists | Among Hospitals With Mean + 10% of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists | |||||

| ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at admission | 70 | 3.4 (2.3‐4.6) | 3.1 (2.0‐3.1) | 0.3 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Beta‐blocker at admission | 65 | 5.8 (3.4‐8.2) | 5.1 (3.0‐7.3) | 0.7 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| AMI admission composite | 65 | 4.5 (2.9‐6.1) | 4.0 (2.6‐5.5) | 0.5 | 11.1 | <0.001* |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at discharge | 62 | 5.1 (3.3‐6.9) | 4.6 (3.1‐6.2) | 0.5 | 9.0 | 0.03 |

| Beta‐blocker at discharge | 63 | 5.1 (2.9‐7.2) | 4.3 (2.5‐6.0) | 0.8 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 44 | 11.4 (6.2‐16.6) | 10.3 (5.4‐15.1) | 1.1 | 10.0 | 0.02 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 70 | 3.4 (2.3‐4.6) | 3.1 (2.0‐4.1) | 0.3 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| AMI hospital/discharge composite | 63 | 5.0 (3.3‐6.7) | 4.4 (3.0‐5.8) | 0.6 | 11.3 | 0.001* |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Ejection fraction assessment | 71 | 5.9 (4.1‐7.6) | 5.6 (3.9‐7.2) | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.07 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 70 | 12.3 (8.6‐16.0) | 11.4 (7.9‐15.0) | 0.9 | 7.1 | 0.008* |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 56 | 8.4 (4.1‐12.6) | 8.2 (4.2‐12.3) | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.67 |

| CHF hospital/discharge composite | 70 | 7.7 (5.8‐9.6) | 7.2 (5.4‐9.0) | 0.5 | 6.0 | 0.004* |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Timing of antibiotics <8 hours | 71 | 5.9 (4.2‐7.6) | 5.9 (4.1‐7.7) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.98 |

| Blood culture before antibiotics | 71 | 10.0 (8.0‐12.0) | 9.8 (7.7‐11.8) | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.18 |

| Initial antibiotic consistent with recommendations | 71 | 13.3 (10.4‐16.2) | 12.9 (9.9‐15.9) | 0.4 | 2.8 | 0.20 |

| Pneumonia admission composite | 71 | 9.4 (7.7‐11.1) | 9.2 (7.6‐10.9) | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.23 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Pneumonia vaccine | 71 | 27.0 (19.2‐34.8) | 24.7 (17.2‐32.2) | 2.3 | 8.4 | 0.006 |

| Influenza vaccine | 71 | 34.1 (25.9‐42.2) | 32.6 (24.7‐40.5) | 1.5 | 4.3 | 0.03 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 67 | 15.2 (9.8‐20.7) | 15.0 (9.6‐20.4) | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.56 |

| Pneumonia hospital/discharge composite | 71 | 26.7 (20.3‐33.1) | 25.2 (19.0‐31.3) | 1.5 | 5.8 | 0.006* |

In order to test the robustness of our results, we carried out 2 secondary analyses. First, we used multivariable models to generate a propensity score representing the predicted probability of being assigned to a hospital with hospitalists. We then used the propensity score as an additional covariate in subsequent multivariable models. In addition, we performed a complete‐case analysis (including only hospitals with complete data, n = 204) as a check on the sensitivity of our results to missing data. Neither analysis produced results substantially different from those presented.

Discussion

In this cross‐sectional analysis of hospitals participating in a voluntary quality reporting initiative, hospitals with at least 1 hospitalist group had fewer missed discharge care process measures for CHF, even after adjusting for hospital‐level characteristics. In addition, as the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists increased, the percentage of missed quality opportunities decreased across all measures. The observed relationships were most apparent for measures that could be completed at any time during the hospitalization and at discharge. While it is likely that hospitalists are a marker of a hospital's ability to invest in systems (and as a result, care improvement initiatives), the presence of a potential dose‐response relationship suggests that hospitalists themselves may have a role in improving processes of care.

Our study suggests a generally positive, but mixed, picture of hospitalists' effects on quality process measure performance. Lack of uniformity across measures may depend on the timing of the process measure (eg, whether or not the process is measured at admission or discharge). For example, in contrast to admission process measures, we more commonly observed a positive association between hospitalists and care quality on process measures targeting processes that generally took place later in hospitalization or at discharge. Many admission process measures (eg, door to antibiotic time, blood cultures, and appropriate initial antibiotics) likely occurred prior to hospitalist involvement in most cases and were instead under the direction of emergency medicine physicians. Performance on these measures would not be expected to relate to use of hospitalists, and that is what we observed.

In addition to the timing of when a process was measured or took place, associations between hospitalists and care quality vary by disease. The apparent variation in impact of hospitalists by disease (more impact for cardiac conditions, less for pneumonia) may relate primarily to the characteristics of the processes of care that were measured for each condition. For example, one‐half of the pneumonia process measures related to care occurring within a few hours of admission, while the other one‐half (smoking cessation advice and streptococcal and influenza vaccines) were often administered per protocol or by nonphysician providers.26‐29 However, more of the cardiac measures required physician action (eg, prescription of an ACE‐I at discharge). Alternatively, unmeasured confounders important in the delivery of cardiac care might play an important role in the relationship between hospitalists and cardiac process measure performance.

Our approach to defining hospitalists bears mention as well. While a dichotomous measure of having hospitalists available was only statistically significant for the single CHF discharge composite measure, our measure of hospitalist availabilitythe percentage of patients admitted by hospitalistswas more strongly associated with a larger number of quality measures. Contrast between the dichotomous and continuous measures may have statistical explanations (the power to see differences between 2 groups is more limited with use of a binary predictor, which itself can be subject to bias),30 but may also indicate a dose‐response relationship. A larger number of admissions to hospitalists may help standardize practices, as care is concentrated in a smaller number of physicians' hands. Moreover, larger hospitalist programs may be more likely to have implemented care standardization or quality improvement processes or to have been incorporated into (or lead) hospitals' quality infrastructures. Finally, presence of larger hospitalist groups may be a marker for a hospital's capacity to make hospital‐wide investments in improvement. However, the association between the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and care quality persisted even after adjustment for many measures plausibly associated with ability to invest in care quality.

Our study has several limitations. First, although we used a widely accepted definition of hospitalists endorsed by the Society of Hospital Medicine, there are no gold standard definitions for a hospitalist's job description or skill set. As a result, it is possible that a model utilizing rotating internists (from a multispecialty group) might have been misidentified as a hospitalist model. Second, our findings represent a convenience sample of hospitals in a voluntary reporting initiative (CHART) and may not be applicable to hospitals that are less able to participate in such an endeavor. CHART hospitals are recognized to be better performers than the overall California population of hospitals, potentially decreasing variability in our quality of care measures.2 Third, there were significant differences between our comparison groups within the CHART hospitals, including sample size. Although we attempted to adjust our analyses for many important potential confounders and applied conservative measures to assess statistical significance, given the baseline differences, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured factors. Fourth, as described above, this observational study cannot provide robust evidence to support conclusions regarding causality. Fifth, the estimation of the percent of patients admitted by hospitalists is unvalidated and based upon self‐reported and incomplete (41% of respondents) data. We are somewhat reassured by the fact that respondents and nonresponders were similar across all hospital characteristics, as well as outcomes. Sixth, misclassification of the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists may have influenced our results. Although possible, misclassification often biases results toward the null, potentially weakening any observed association. Given that our respondents were not aware of our hypotheses, there is no reason to expect recall issues to bias the results one way or the other. Finally, for many performance measures, overall performance was excellent among all hospitals (eg, aspirin at admission) with limited variability, thus limiting the ability to assess for differences.

In summary, in a large, cross‐sectional study of California hospitals participating in a voluntary quality reporting initiative, the presence of hospitalists was associated with modest improvements in hospital‐level performance of quality process measures. In addition, we found a relationship between the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and improved process measure adherence. Although we cannot determine causality, our data support the hypothesis that dedicated hospital physicians can positively affect the quality of care. Future research should examine this relationship in other settings and should address causality using broader measures of quality including both processes and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Teresa Chipps, BS, Center for Health Services Research, Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, for her administrative and editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

- ,,,.Care in U.S. hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance Program.N Engl J Med.2005;353:265–274.

- CalHospitalCompare.org: online report card simplifies the search for quality hospital care. Available at: http://www.chcf.org/topics/hospitals/index.cfm?itemID=131387. Accessed September 2009.

- ,,, et al.Hospital characteristics and quality of care.JAMA.1992;268:1709–1714.

- ,,,,.Patient and hospital characteristics associated with recommended processes of care for elderly patients hospitalized with pneumonia: results from the Medicare quality indicator system pneumonia module.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:827–833.

- ,,, et al.A systematic review and meta‐analysis of studies comparing mortality rates of private for‐profit and private not‐for‐profit hospitals.CMAJ.2002;166:1399–1406.

- ,.Teaching hospitals and quality of care: a review of the literature.Milbank Q.2002;80:569–593.

- ,,,,.Nurse‐staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals.N Engl J Med.2002;346:1715–1722.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360:1102–1112.

- ,,,.Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and roles.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20:101–107.

- ,,,.Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community‐based primary care physicians.Mayo Clin Proc.2002;77:1053–1058.

- ,,,.Comparison of hospitalists and nonhospitalists regarding core measures of pneumonia care.Am J Manag Care.2007;13:129–132.

- ,,.Comparison of practice patterns of hospitalists and community physicians in the care of patients with congestive heart failure.J Hosp Med.2008;3:35–41.

- ,,, et al.Quality of care for decompensated heart failure: comparable performance between academic hospitalists and non‐hospitalists.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23:1399–1406.

- ,,,,.Quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: assessing the impact of hospitalists.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1251–1256.

- ,,,.The inverse relationship between mortality rates and performance in the Hospital Quality Alliance measures.Health Aff.2007;26:1104–1110.

- ,,,,.Does the Leapfrog program help identify high‐quality hospitals?Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2008;34:318–325.

- ,,,,,.Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians.N Engl J Med.2007;357:2589–2600.

- CMS HQI demonstration project—composite quality score methodology overview. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HospitalQualityInits/downloads/HospitalCompositeQualityScoreMethodologyOverview.pdf. Accessed September 2009.

- ,,.Modeling risk using generalized linear models.J Health Econ.1999;18:153–171.

- ,,.Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data.J Health Econ.2005;24:465–488.

- ,,, et al.Quality of care for the treatment of acute medical conditions in US hospitals.Arch Intern Med.2006;166:2511–2517.

- ,,, et al.The Dartmouth Atlas of Cardiovascular Health Care.Chicago:AHA Press;1999. Current data from the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Lebanon, NH. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/atlases/atlas_ series.shtm. Accessed September 2009.

- ,,.Differences in per capita rates of revascularization and in choice of revascularization procedure for eleven states.BMC Health Serv Res.2006;6:35.

- ,,.The relationship between physician supply, cardiovascular health service use and cardiac disease burden in Ontario: supply‐need mismatch.Can J Card.2008;24:187.

- .Multiple imputation: a primer.Stat Methods Med Res.1999;8:3–15.

- .Nursing intervention and smoking cessation: Meta‐analysis update.Heart Lung.2006;35:147–163.

- .Ten‐year durability and success of an organized program to increase influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates among high‐risk adults.Am J Med.1998;105:385–392.

- ,,, et al.Role of student pharmacist interns in hospital‐based standing orders pneumococcal vaccination program.J Am Pharm Assoc.2007;47:404–409.

- ,,,.Effect of a pharmacist‐managed program of pneumococcal and influenza immunization on vaccination rates among adult inpatients.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2003;60:1767–1771.

- ,,.Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: a bad idea.Stat Med.2006;25:127–141.

Quality of care in US hospitals is inconsistent and often below accepted standards.1 This observation has catalyzed a number of performance measurement initiatives intended to publicize gaps and spur quality improvement.2 As the field has evolved, organizational factors such as teaching status, ownership model, nurse staffing levels, and hospital volume have been found to be associated with performance on quality measures.1, 3‐7 Hospitalists represent a more recent change in the organization of inpatient care8 that may impact hospital‐level performance. In fact, most hospitals provide financial support to hospitalists, not only for hopes of improving efficiency, but also for improving quality and safety.9

Only a few single‐site studies have examined the impact of hospitalists on quality of care for common medical conditions (ie, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction), and each has focused on patient‐level effects. Rifkin et al.10, 11 did not find differences between hospitalists' and nonhospitalists' patients in terms of pneumonia process measures. Roytman et al.12 found hospitalists more frequently prescribed afterload‐reducing agents for congestive heart failure (CHF), but other studies have shown no differences in care quality for heart failure.13, 14 Importantly, no studies have examined the role of hospitalists in the care of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In addition, studies have not addressed the effect of hospitalists at the hospital level to understand whether hospitalists have broader system‐level effects reflected by overall hospital performance.

We hypothesized that the presence of hospitalists within a hospital would be associated with improvements in hospital‐level adherence to publicly reported quality process measures, and having a greater percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists would be associated with improved performance. To test these hypotheses, we linked data from a statewide census of hospitalists with data collected as part of a hospital quality‐reporting initiative.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

We examined the performance of 209 hospitals (63% of all 334 non‐federal facilities in California) participating in the California Hospital Assessment and Reporting Taskforce (CHART) at the time of the survey. CHART is a voluntary quality reporting initiative that began publicly reporting hospital quality data in January 2006.

Hospital‐level Organizational, Case‐mix, and Quality Data

Hospital organizational characteristics (eg, bed size) were obtained from publicly available discharge and utilization data sets from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). We also linked hospital‐level patient‐mix data (eg, race) from these OSHPD files.

We obtained quality of care data from CHART for January 2006 through June 2007, the time period corresponding to the survey. Quality metrics included 16 measures collected by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.hhs.gov) and extensively used in quality research.1, 4, 13, 15‐17 Rather than define a single measure, we examined multiple process measures, anticipating differential impacts of hospitalists on various processes of care for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia. Measures were further divided among those that are usually measured upon initial presentation to the hospital and those that are measured throughout the entire hospitalization and discharge. This division reflects the division of care in the hospital, where emergency room physicians are likely to have a more critical role for admission processes.

Survey Process

We surveyed all nonfederal, acute care hospitals in California that participated in CHART.2 We first identified contacts at each site via professional society mailing lists. We then sent web‐based surveys to all with available email addresses and a fax/paper survey to the remainder. We surveyed individuals between October 2006 and April 2007 and repeated the process at intervals of 1 to 3 weeks. For remaining nonrespondents, we placed a direct call unless consent to survey had been specifically refused. We contacted the following persons in sequence: (1) hospital executives or administrative leaders; (2) hospital medicine department leaders; (3) admitting emergency room personnel or medical staff officers; and (4) hospital website information. In the case of multiple responses with disagreement, the hospital/hospitalist leader's response was treated as the primary source. At each step, respondents were asked to answer questions only if they had a direct working knowledge of their hospitalist services.

Survey Data

Our key survey question to all respondents included whether the respondents could confirm their hospitals had at least one hospitalist medicine group. Hospital leaders were also asked to participate in a more comprehensive survey of their organizational and clinical characteristics. Within the comprehensive survey, leaders also provided estimates of the percent of general medical patients admitted by hospitalists. This measure, used in prior surveys of hospital leaders,9 was intended to be an easily understood approximation of the intensity of hospitalist utilization in any given hospital. A more rigorous, direct measure was not feasible due to the complexity of obtaining admission data over such a large, diverse set of hospitals.

Process Performance Measures

AMI measures assessed at admission included aspirin and ‐blocker administration within 24 hours of arrival. AMI measures assessed at discharge included aspirin administration, ‐blocker administration, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE‐I) (or angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]) administration for left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. There were no CHF admission measures. CHF discharge measures included assessment of LV function, the use of an ACE‐I or ARB for LV dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. Pneumonia admission measures included the drawing of blood cultures prior to the receipt of antibiotics, timely administration of initial antibiotics (<8 hours), and antibiotics consistent with recommendations. Pneumonia discharge measures included pneumococcal vaccination, flu vaccination, and smoking cessation counseling.

For each performance measure, we quantified the percentage of missed quality opportunities, defined as the number of patients who did not receive a care process divided by the number of eligible patients, multiplied by 100. In addition, we calculated composite scores for admission and discharge measures across each condition. We summed the numerators and denominators of individual performance measures to generate a disease‐specific composite numerator and denominator. Both individual and composite scores were produced using methodology outlined by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.18 In order to retain as representative a sample of hospitals as possible, we calculated composite scores for hospitals that had a minimum of 25 observations in at least 2 of the quality indicators that made up each composite score.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi‐square tests, Student t tests, and Mann‐Whitney tests, where appropriate, to compare hospital‐level characteristics of hospitals that utilized hospitalists vs. those that did not. Similar analyses were performed among the subset of hospitals that utilized hospitalists. Among this subgroup of hospitals, we compared hospital‐level characteristics between hospitals that provided information regarding the percent of patients admitted by hospitalists vs. those who did not provide this information.

We used multivariable, generalized linear regression models to assess the relationship between having at least 1 hospitalist group and the percentage of missed quality of care measures. Because percentages were not normally distributed (ie, a majority of hospitals had few missed opportunities, while a minority had many), multivariable models employed log‐link functions with a gamma distribution.19, 20 Coefficients for our key predictor (presence of hospitalists) were transformed back to the original units (percentage of missed quality opportunities) so that a positive coefficient represented a higher number of quality measures missed relative to hospitals without hospitalists. Models were adjusted for factors previously reported to be associated with care quality. Hospital organizational characteristics included the number of beds, teaching status, registered nursing (RN) hours per adjusted patient day, and hospital ownership (for‐profit vs. not‐for‐profit). Hospital patient mix factors included annual percentage of admissions by insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, other), annual percentage of admissions by race (white vs. nonwhite), annual percentage of do‐not‐resuscitate status at admission, and mean diagnosis‐related group‐based case‐mix index.21 We additionally adjusted for the number of cardiac catheterizations, a measure that moderately correlates with the number of cardiologists and technology utilization.22‐24 In our subset analysis among those hospitals with hospitalists, our key predictor for regression analyses was the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. For ease of interpretation, the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists was centered on the mean across all respondent hospitals, and we report the effect of increasing by 10% the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. Models were adjusted for the same hospital organizational characteristics listed above. For those models, a positive coefficient also meant a higher number of measures missed.

For both sets of predictors, we additionally tested for the presence of interactions between the predictors and hospital bed size (both continuous as well as dichotomized at 150 beds) in composite measure performance, given the possibility that any hospitalist effect may be greater among smaller, resource‐limited hospitals. Tests for interaction were performed with the likelihood ratio test. In addition, to minimize any potential bias or loss of power that might result from limiting the analysis to hospitals with complete data, we used the multivariate imputation by chained equations method, as implemented in STATA 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), to create 10 imputed datasets.25 Imputation of missing values was restricted to confounding variables. Standard methods were then used to combine results over the 10 imputed datasets. We also applied Bonferroni corrections to composite measure tests based on the number of composites generated (n = 5). Thus, for the 5 inpatient composites created, standard definitions of significance (P 0.05) were corrected by dividing composite P values by 5, requiring P 0.01 for significance. The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco, approved the study. All analyses were performed using STATA 9.2.

Results

Characteristics of Participating Sites

There were 209 eligible hospitals. All 209 (100%) hospitals provided data about the presence or absence of hospitalists via at least 1 of our survey strategies. The majority of identification of hospitalist utilization was via contact with either hospital or hospitalist leaders, n = 147 (70.3%). Web‐sites informed hospitalist prevalence in only 3 (1.4%) hospitals. There were 8 (3.8%) occurrences of disagreement between sources, all of which had available hospital/hospitalist leader responses. Only 1 (0.5%) hospital did not have the minimum 25 patients eligible for any disease‐specific quality measures during the data reporting period. Collectively, the remaining 208 hospitals accounted for 81% of California's acute care hospital population.

Comparisons of Sites With Hospitalists and Those Without

A total of 170 hospitals (82%) participating in CHART used hospitalists. Hospitals with and without hospitalists differed by a variety of characteristics (Table 1). Sites with hospitalists were larger, less likely to be for‐profit, had more registered nursing hours per day, and performed more cardiac catheterizations.

| Characteristic | Hospitals Without Hospitalists (n = 38) | Hospitals With Hospitalists (n = 170) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Number of beds, n (% of hospitals) | <0.001 | ||

| 0‐99 | 16 (42.1) | 14 (8.2) | |

| 100‐199 | 8 (21.1) | 44 (25.9) | |

| 200‐299 | 7 (18.4) | 42 (24.7) | |

| 300+ | 7 (18.4) | 70 (41.2) | |

| For profit, n (% of hospitals) | 9 (23.7) | 18 (10.6) | 0.03 |

| Teaching hospital, n (% of hospitals) | 7 (18.4) | 55 (32.4) | 0.09 |

| RN hours per adjusted patient day, number of hours (IQR) | 7.4 (5.7‐8.6) | 8.5 (7.4‐9.9) | <0.001 |

| Annual cardiac catheterizations, n (IQR) | 0 (0‐356) | 210 (0‐813) | 0.007 |

| Hospital total census days, n (IQR) | 37161 (14910‐59750) | 60626 (34402‐87950) | <0.001 |

| ICU total census, n (IQR) | 2193 (1132‐4289) | 3855 (2489‐6379) | <0.001 |

| Medicare insurance, % patients (IQR) | 36.9 (28.5‐48.0) | 35.3(28.2‐44.3) | 0.95 |

| Medicaid insurance, % patients (IQR) | 21.0 (12.7‐48.3) | 16.6 (5.6‐27.6) | 0.02 |

| Race, white, % patients (IQR) | 53.7 (26.0‐82.7) | 59.1 (45.6‐74.3) | 0.73 |

| DNR at admission, % patients (IQR) | 3.6 (2.0‐6.4) | 4.4 (2.7‐7.1) | 0.12 |

| Case‐mix index, index (IQR) | 1.05 (0.90‐1.21) | 1.13 (1.01‐1.26) | 0.11 |

Relationship Between Hospitalist Group Utilization and the Percentage of Missed Quality Opportunities

Table 2 shows the frequency of missed quality opportunities in sites with hospitalists compared to those without. In general, for both individual and composite measures of quality, multivariable adjustment modestly attenuated the observed differences between the 2 groups of hospitals. We present only the more conservative adjusted estimates.

| Quality Measure | Number of Hospitals | Adjusted Mean % Missed Quality Opportunities (95% CI) | Difference With Hospitalists | Relative % Change | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals Without Hospitalists | Hospitals With Hospitalists | |||||

| ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at admission | 193 | 3.7 (2.4‐5.1) | 3.4 (2.3‐4.4) | 0.3 | 10.0 | 0.44 |

| Beta‐blocker at admission | 186 | 7.8 (4.7‐10.9) | 6.4 (4.4‐8.3) | 1.4 | 18.3 | 0.19 |

| AMI admission composite | 186 | 5.5 (3.6‐7.5) | 4.8 (3.4‐6.1) | 0.7 | 14.3 | 0.26 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at discharge | 173 | 7.5 (4.5‐10.4) | 5.2 (3.4‐6.9) | 2.3 | 31.0 | 0.02 |

| Beta‐blocker at discharge | 179 | 6.6 (3.8‐9.4) | 5.9 (3.6‐8.2) | 0.7 | 9.6 | 0.54 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 119 | 20.7 (9.5‐31.8) | 11.8 (6.6‐17.0) | 8.9 | 43.0 | 0.006 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 193 | 3.8 (2.4‐5.1) | 3.4 (2.4‐4.4) | 0.4 | 10.0 | 0.44 |

| AMI hospital/discharge composite | 179 | 6.4 (4.1‐8.6) | 5.3 (3.7‐6.8) | 1.1 | 17.6 | 0.16 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Ejection fraction assessment | 208 | 12.6 (7.7‐17.6) | 6.5 (4.6‐8.4) | 6.1 | 48.2 | <0.001 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 201 | 14.7 (10.0‐19.4) | 12.9 (9.8‐16.1) | 1.8 | 12.1 | 0.31 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 168 | 9.1 (2.9‐15.4) | 9.0 (4.2‐13.8) | 0.1 | 1.8 | 0.98 |

| CHF hospital/discharge composite | 201 | 12.2 (7.9‐16.5) | 8.2 (6.2‐10.2) | 4.0 | 33.1 | 0.006* |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Blood culture before antibiotics | 206 | 12.0 (9.1‐14.9) | 10.9 (8.8‐13.0) | 1.1 | 9.1 | 0.29 |

| Timing of antibiotics <8 hours | 208 | 5.8 (4.1‐7.5) | 6.2 (4.7‐7.7) | 0.4 | 6.9 | 0.56 |

| Initial antibiotic consistent with recommendations | 207 | 15.0 (11.6‐18.6) | 13.8 (10.9‐16.8) | 1.2 | 8.1 | 0.27 |

| Pneumonia admission composite | 207 | 10.5 (8.5‐12.5) | 9.9 (8.3‐11.5) | 0.6 | 5.9 | 0.37 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Pneumonia vaccine | 208 | 29.4 (19.5‐39.2) | 27.1 (19.9‐34.3) | 2.3 | 7.7 | 0.54 |

| Influenza vaccine | 207 | 36.9 (25.4‐48.4) | 35.0 (27.0‐43.1) | 1.9 | 5.2 | 0.67 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 196 | 15.4 (7.8‐23.1) | 13.9 (8.9‐18.9) | 1.5 | 10.2 | 0.59 |

| Pneumonia hospital/discharge composite | 207 | 29.6 (20.5‐38.7) | 27.3 (20.9‐33.6) | 2.3 | 7.8 | 0.51 |

Compared to hospitals without hospitalists, those with hospitalists did not have any statistically significant differences in the individual and composite admission measures for each of the disease processes. In contrast, there were statistically significant differences between hospitalist and nonhospitalist sites for many individual cardiac processes of care that typically occur after admission from the emergency room (ie, LV function assessment for CHF) or those that occurred at discharge (ie, aspirin and ACE‐I/ARB at discharge for AMI). Similarly, the composite discharge scores for AMI and CHF revealed better overall process measure performance at sites with hospitalists, although the AMI composite did not meet statistical significance. There were no statistically significant differences between groups for the pneumonia process measures assessed at discharge. In addition, for composite measures there were no statistically significant interactions between hospitalist prevalence and bed size, although there was a trend (P = 0.06) for the CHF discharge composite, with a larger effect of hospitalists among smaller hospitals.

Percent of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists

Of the 171 hospitals with hospitalists, 71 (42%) estimated the percent of patients admitted by their hospitalist physicians. Among the respondents, the mean and median percentages of medical patients admitted by hospitalists were 51% (SD = 25%) and 49% (IQR = 30‐70%), respectively. Thirty hospitals were above the sample mean. Compared to nonrespondent sites, respondent hospitals took care of more white patients; otherwise, respondent and nonrespondent hospitals were similar in terms of bed size, location, performance across each measure, and other observable characteristics (Supporting Information, Appendix 1).

Relationship Between the Estimated Percentages of Medical Patients Admitted by Hospitalists and Missed Quality Opportunities

Table 3 displays the change in missed quality measures associated with each additional 10% of patients estimated to be admitted by hospitalists. A higher estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists was associated with statistically significant improvements in quality of care across a majority of individual measures and for all composite discharge measures regardless of condition. For example, every 10% increase in the mean estimated number of patients admitted by hospitalists was associated with a mean of 0.6% (P < 0.001), 0.5% (P = 0.004), and 1.5% (P = 0.006) fewer missed quality opportunities for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia discharge process measures composites, respectively. In addition, for these composite measures, there were no statistically significant interactions between the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and bed size (dichotomized at 150 beds), although there was a trend (P = 0.09) for the AMI discharge composite, with a larger effect of hospitalists among smaller hospitals.

| Quality Measure | Number of Hospitals | Adjusted % Missed Quality Opportunities (95% CI) | Difference With Hospitalists | Relative Percent Change | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Hospitals With Mean % of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists | Among Hospitals With Mean + 10% of Patients Admitted by Hospitalists | |||||

| ||||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at admission | 70 | 3.4 (2.3‐4.6) | 3.1 (2.0‐3.1) | 0.3 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| Beta‐blocker at admission | 65 | 5.8 (3.4‐8.2) | 5.1 (3.0‐7.3) | 0.7 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| AMI admission composite | 65 | 4.5 (2.9‐6.1) | 4.0 (2.6‐5.5) | 0.5 | 11.1 | <0.001* |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Aspirin at discharge | 62 | 5.1 (3.3‐6.9) | 4.6 (3.1‐6.2) | 0.5 | 9.0 | 0.03 |

| Beta‐blocker at discharge | 63 | 5.1 (2.9‐7.2) | 4.3 (2.5‐6.0) | 0.8 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 44 | 11.4 (6.2‐16.6) | 10.3 (5.4‐15.1) | 1.1 | 10.0 | 0.02 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 70 | 3.4 (2.3‐4.6) | 3.1 (2.0‐4.1) | 0.3 | 10.2 | 0.001 |

| AMI hospital/discharge composite | 63 | 5.0 (3.3‐6.7) | 4.4 (3.0‐5.8) | 0.6 | 11.3 | 0.001* |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Ejection fraction assessment | 71 | 5.9 (4.1‐7.6) | 5.6 (3.9‐7.2) | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.07 |

| ACE‐I/ARB at discharge | 70 | 12.3 (8.6‐16.0) | 11.4 (7.9‐15.0) | 0.9 | 7.1 | 0.008* |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 56 | 8.4 (4.1‐12.6) | 8.2 (4.2‐12.3) | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.67 |

| CHF hospital/discharge composite | 70 | 7.7 (5.8‐9.6) | 7.2 (5.4‐9.0) | 0.5 | 6.0 | 0.004* |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| Admission measures | ||||||

| Timing of antibiotics <8 hours | 71 | 5.9 (4.2‐7.6) | 5.9 (4.1‐7.7) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.98 |

| Blood culture before antibiotics | 71 | 10.0 (8.0‐12.0) | 9.8 (7.7‐11.8) | 0.2 | 2.6 | 0.18 |

| Initial antibiotic consistent with recommendations | 71 | 13.3 (10.4‐16.2) | 12.9 (9.9‐15.9) | 0.4 | 2.8 | 0.20 |

| Pneumonia admission composite | 71 | 9.4 (7.7‐11.1) | 9.2 (7.6‐10.9) | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.23 |

| Hospital/discharge measures | ||||||

| Pneumonia vaccine | 71 | 27.0 (19.2‐34.8) | 24.7 (17.2‐32.2) | 2.3 | 8.4 | 0.006 |

| Influenza vaccine | 71 | 34.1 (25.9‐42.2) | 32.6 (24.7‐40.5) | 1.5 | 4.3 | 0.03 |

| Smoking cessation counseling | 67 | 15.2 (9.8‐20.7) | 15.0 (9.6‐20.4) | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.56 |

| Pneumonia hospital/discharge composite | 71 | 26.7 (20.3‐33.1) | 25.2 (19.0‐31.3) | 1.5 | 5.8 | 0.006* |

In order to test the robustness of our results, we carried out 2 secondary analyses. First, we used multivariable models to generate a propensity score representing the predicted probability of being assigned to a hospital with hospitalists. We then used the propensity score as an additional covariate in subsequent multivariable models. In addition, we performed a complete‐case analysis (including only hospitals with complete data, n = 204) as a check on the sensitivity of our results to missing data. Neither analysis produced results substantially different from those presented.

Discussion

In this cross‐sectional analysis of hospitals participating in a voluntary quality reporting initiative, hospitals with at least 1 hospitalist group had fewer missed discharge care process measures for CHF, even after adjusting for hospital‐level characteristics. In addition, as the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists increased, the percentage of missed quality opportunities decreased across all measures. The observed relationships were most apparent for measures that could be completed at any time during the hospitalization and at discharge. While it is likely that hospitalists are a marker of a hospital's ability to invest in systems (and as a result, care improvement initiatives), the presence of a potential dose‐response relationship suggests that hospitalists themselves may have a role in improving processes of care.

Our study suggests a generally positive, but mixed, picture of hospitalists' effects on quality process measure performance. Lack of uniformity across measures may depend on the timing of the process measure (eg, whether or not the process is measured at admission or discharge). For example, in contrast to admission process measures, we more commonly observed a positive association between hospitalists and care quality on process measures targeting processes that generally took place later in hospitalization or at discharge. Many admission process measures (eg, door to antibiotic time, blood cultures, and appropriate initial antibiotics) likely occurred prior to hospitalist involvement in most cases and were instead under the direction of emergency medicine physicians. Performance on these measures would not be expected to relate to use of hospitalists, and that is what we observed.

In addition to the timing of when a process was measured or took place, associations between hospitalists and care quality vary by disease. The apparent variation in impact of hospitalists by disease (more impact for cardiac conditions, less for pneumonia) may relate primarily to the characteristics of the processes of care that were measured for each condition. For example, one‐half of the pneumonia process measures related to care occurring within a few hours of admission, while the other one‐half (smoking cessation advice and streptococcal and influenza vaccines) were often administered per protocol or by nonphysician providers.26‐29 However, more of the cardiac measures required physician action (eg, prescription of an ACE‐I at discharge). Alternatively, unmeasured confounders important in the delivery of cardiac care might play an important role in the relationship between hospitalists and cardiac process measure performance.

Our approach to defining hospitalists bears mention as well. While a dichotomous measure of having hospitalists available was only statistically significant for the single CHF discharge composite measure, our measure of hospitalist availabilitythe percentage of patients admitted by hospitalistswas more strongly associated with a larger number of quality measures. Contrast between the dichotomous and continuous measures may have statistical explanations (the power to see differences between 2 groups is more limited with use of a binary predictor, which itself can be subject to bias),30 but may also indicate a dose‐response relationship. A larger number of admissions to hospitalists may help standardize practices, as care is concentrated in a smaller number of physicians' hands. Moreover, larger hospitalist programs may be more likely to have implemented care standardization or quality improvement processes or to have been incorporated into (or lead) hospitals' quality infrastructures. Finally, presence of larger hospitalist groups may be a marker for a hospital's capacity to make hospital‐wide investments in improvement. However, the association between the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and care quality persisted even after adjustment for many measures plausibly associated with ability to invest in care quality.

Our study has several limitations. First, although we used a widely accepted definition of hospitalists endorsed by the Society of Hospital Medicine, there are no gold standard definitions for a hospitalist's job description or skill set. As a result, it is possible that a model utilizing rotating internists (from a multispecialty group) might have been misidentified as a hospitalist model. Second, our findings represent a convenience sample of hospitals in a voluntary reporting initiative (CHART) and may not be applicable to hospitals that are less able to participate in such an endeavor. CHART hospitals are recognized to be better performers than the overall California population of hospitals, potentially decreasing variability in our quality of care measures.2 Third, there were significant differences between our comparison groups within the CHART hospitals, including sample size. Although we attempted to adjust our analyses for many important potential confounders and applied conservative measures to assess statistical significance, given the baseline differences, we cannot rule out the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured factors. Fourth, as described above, this observational study cannot provide robust evidence to support conclusions regarding causality. Fifth, the estimation of the percent of patients admitted by hospitalists is unvalidated and based upon self‐reported and incomplete (41% of respondents) data. We are somewhat reassured by the fact that respondents and nonresponders were similar across all hospital characteristics, as well as outcomes. Sixth, misclassification of the estimated percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists may have influenced our results. Although possible, misclassification often biases results toward the null, potentially weakening any observed association. Given that our respondents were not aware of our hypotheses, there is no reason to expect recall issues to bias the results one way or the other. Finally, for many performance measures, overall performance was excellent among all hospitals (eg, aspirin at admission) with limited variability, thus limiting the ability to assess for differences.

In summary, in a large, cross‐sectional study of California hospitals participating in a voluntary quality reporting initiative, the presence of hospitalists was associated with modest improvements in hospital‐level performance of quality process measures. In addition, we found a relationship between the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists and improved process measure adherence. Although we cannot determine causality, our data support the hypothesis that dedicated hospital physicians can positively affect the quality of care. Future research should examine this relationship in other settings and should address causality using broader measures of quality including both processes and outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Teresa Chipps, BS, Center for Health Services Research, Division of General Internal Medicine and Public Health, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, for her administrative and editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Quality of care in US hospitals is inconsistent and often below accepted standards.1 This observation has catalyzed a number of performance measurement initiatives intended to publicize gaps and spur quality improvement.2 As the field has evolved, organizational factors such as teaching status, ownership model, nurse staffing levels, and hospital volume have been found to be associated with performance on quality measures.1, 3‐7 Hospitalists represent a more recent change in the organization of inpatient care8 that may impact hospital‐level performance. In fact, most hospitals provide financial support to hospitalists, not only for hopes of improving efficiency, but also for improving quality and safety.9

Only a few single‐site studies have examined the impact of hospitalists on quality of care for common medical conditions (ie, pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction), and each has focused on patient‐level effects. Rifkin et al.10, 11 did not find differences between hospitalists' and nonhospitalists' patients in terms of pneumonia process measures. Roytman et al.12 found hospitalists more frequently prescribed afterload‐reducing agents for congestive heart failure (CHF), but other studies have shown no differences in care quality for heart failure.13, 14 Importantly, no studies have examined the role of hospitalists in the care of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In addition, studies have not addressed the effect of hospitalists at the hospital level to understand whether hospitalists have broader system‐level effects reflected by overall hospital performance.

We hypothesized that the presence of hospitalists within a hospital would be associated with improvements in hospital‐level adherence to publicly reported quality process measures, and having a greater percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists would be associated with improved performance. To test these hypotheses, we linked data from a statewide census of hospitalists with data collected as part of a hospital quality‐reporting initiative.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

We examined the performance of 209 hospitals (63% of all 334 non‐federal facilities in California) participating in the California Hospital Assessment and Reporting Taskforce (CHART) at the time of the survey. CHART is a voluntary quality reporting initiative that began publicly reporting hospital quality data in January 2006.

Hospital‐level Organizational, Case‐mix, and Quality Data

Hospital organizational characteristics (eg, bed size) were obtained from publicly available discharge and utilization data sets from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). We also linked hospital‐level patient‐mix data (eg, race) from these OSHPD files.

We obtained quality of care data from CHART for January 2006 through June 2007, the time period corresponding to the survey. Quality metrics included 16 measures collected by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (www.cms.hhs.gov) and extensively used in quality research.1, 4, 13, 15‐17 Rather than define a single measure, we examined multiple process measures, anticipating differential impacts of hospitalists on various processes of care for AMI, CHF, and pneumonia. Measures were further divided among those that are usually measured upon initial presentation to the hospital and those that are measured throughout the entire hospitalization and discharge. This division reflects the division of care in the hospital, where emergency room physicians are likely to have a more critical role for admission processes.

Survey Process

We surveyed all nonfederal, acute care hospitals in California that participated in CHART.2 We first identified contacts at each site via professional society mailing lists. We then sent web‐based surveys to all with available email addresses and a fax/paper survey to the remainder. We surveyed individuals between October 2006 and April 2007 and repeated the process at intervals of 1 to 3 weeks. For remaining nonrespondents, we placed a direct call unless consent to survey had been specifically refused. We contacted the following persons in sequence: (1) hospital executives or administrative leaders; (2) hospital medicine department leaders; (3) admitting emergency room personnel or medical staff officers; and (4) hospital website information. In the case of multiple responses with disagreement, the hospital/hospitalist leader's response was treated as the primary source. At each step, respondents were asked to answer questions only if they had a direct working knowledge of their hospitalist services.

Survey Data

Our key survey question to all respondents included whether the respondents could confirm their hospitals had at least one hospitalist medicine group. Hospital leaders were also asked to participate in a more comprehensive survey of their organizational and clinical characteristics. Within the comprehensive survey, leaders also provided estimates of the percent of general medical patients admitted by hospitalists. This measure, used in prior surveys of hospital leaders,9 was intended to be an easily understood approximation of the intensity of hospitalist utilization in any given hospital. A more rigorous, direct measure was not feasible due to the complexity of obtaining admission data over such a large, diverse set of hospitals.

Process Performance Measures

AMI measures assessed at admission included aspirin and ‐blocker administration within 24 hours of arrival. AMI measures assessed at discharge included aspirin administration, ‐blocker administration, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE‐I) (or angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]) administration for left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. There were no CHF admission measures. CHF discharge measures included assessment of LV function, the use of an ACE‐I or ARB for LV dysfunction, and smoking cessation counseling. Pneumonia admission measures included the drawing of blood cultures prior to the receipt of antibiotics, timely administration of initial antibiotics (<8 hours), and antibiotics consistent with recommendations. Pneumonia discharge measures included pneumococcal vaccination, flu vaccination, and smoking cessation counseling.

For each performance measure, we quantified the percentage of missed quality opportunities, defined as the number of patients who did not receive a care process divided by the number of eligible patients, multiplied by 100. In addition, we calculated composite scores for admission and discharge measures across each condition. We summed the numerators and denominators of individual performance measures to generate a disease‐specific composite numerator and denominator. Both individual and composite scores were produced using methodology outlined by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.18 In order to retain as representative a sample of hospitals as possible, we calculated composite scores for hospitals that had a minimum of 25 observations in at least 2 of the quality indicators that made up each composite score.

Statistical Analysis

We used chi‐square tests, Student t tests, and Mann‐Whitney tests, where appropriate, to compare hospital‐level characteristics of hospitals that utilized hospitalists vs. those that did not. Similar analyses were performed among the subset of hospitals that utilized hospitalists. Among this subgroup of hospitals, we compared hospital‐level characteristics between hospitals that provided information regarding the percent of patients admitted by hospitalists vs. those who did not provide this information.

We used multivariable, generalized linear regression models to assess the relationship between having at least 1 hospitalist group and the percentage of missed quality of care measures. Because percentages were not normally distributed (ie, a majority of hospitals had few missed opportunities, while a minority had many), multivariable models employed log‐link functions with a gamma distribution.19, 20 Coefficients for our key predictor (presence of hospitalists) were transformed back to the original units (percentage of missed quality opportunities) so that a positive coefficient represented a higher number of quality measures missed relative to hospitals without hospitalists. Models were adjusted for factors previously reported to be associated with care quality. Hospital organizational characteristics included the number of beds, teaching status, registered nursing (RN) hours per adjusted patient day, and hospital ownership (for‐profit vs. not‐for‐profit). Hospital patient mix factors included annual percentage of admissions by insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, other), annual percentage of admissions by race (white vs. nonwhite), annual percentage of do‐not‐resuscitate status at admission, and mean diagnosis‐related group‐based case‐mix index.21 We additionally adjusted for the number of cardiac catheterizations, a measure that moderately correlates with the number of cardiologists and technology utilization.22‐24 In our subset analysis among those hospitals with hospitalists, our key predictor for regression analyses was the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. For ease of interpretation, the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists was centered on the mean across all respondent hospitals, and we report the effect of increasing by 10% the percentage of patients admitted by hospitalists. Models were adjusted for the same hospital organizational characteristics listed above. For those models, a positive coefficient also meant a higher number of measures missed.

For both sets of predictors, we additionally tested for the presence of interactions between the predictors and hospital bed size (both continuous as well as dichotomized at 150 beds) in composite measure performance, given the possibility that any hospitalist effect may be greater among smaller, resource‐limited hospitals. Tests for interaction were performed with the likelihood ratio test. In addition, to minimize any potential bias or loss of power that might result from limiting the analysis to hospitals with complete data, we used the multivariate imputation by chained equations method, as implemented in STATA 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), to create 10 imputed datasets.25 Imputation of missing values was restricted to confounding variables. Standard methods were then used to combine results over the 10 imputed datasets. We also applied Bonferroni corrections to composite measure tests based on the number of composites generated (n = 5). Thus, for the 5 inpatient composites created, standard definitions of significance (P 0.05) were corrected by dividing composite P values by 5, requiring P 0.01 for significance. The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco, approved the study. All analyses were performed using STATA 9.2.

Results

Characteristics of Participating Sites

There were 209 eligible hospitals. All 209 (100%) hospitals provided data about the presence or absence of hospitalists via at least 1 of our survey strategies. The majority of identification of hospitalist utilization was via contact with either hospital or hospitalist leaders, n = 147 (70.3%). Web‐sites informed hospitalist prevalence in only 3 (1.4%) hospitals. There were 8 (3.8%) occurrences of disagreement between sources, all of which had available hospital/hospitalist leader responses. Only 1 (0.5%) hospital did not have the minimum 25 patients eligible for any disease‐specific quality measures during the data reporting period. Collectively, the remaining 208 hospitals accounted for 81% of California's acute care hospital population.