User login

Iliac vein compression syndrome: An underdiagnosed cause of lower extremity deep venous thrombosis

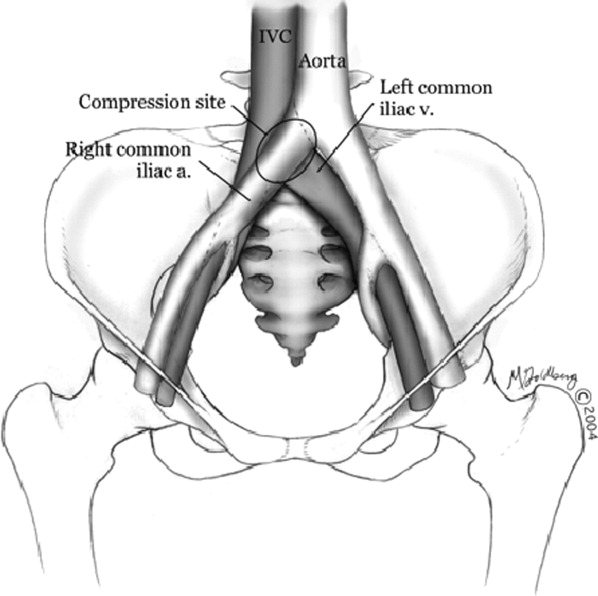

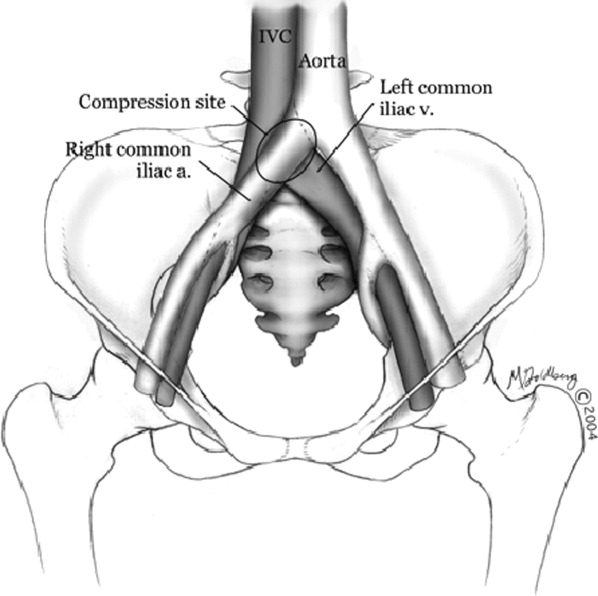

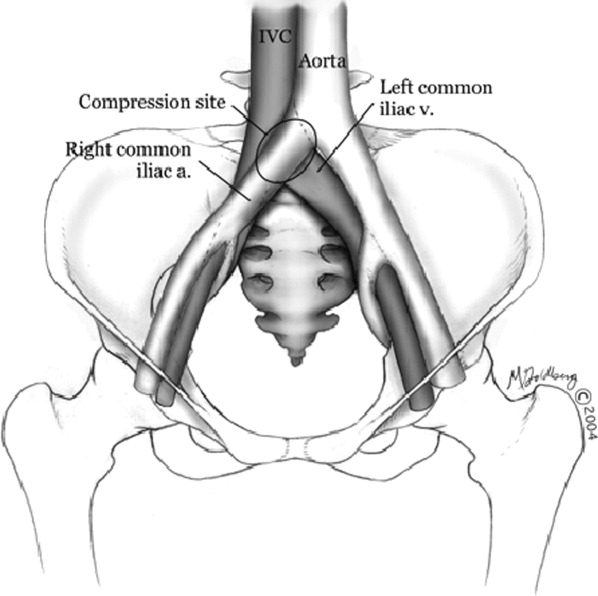

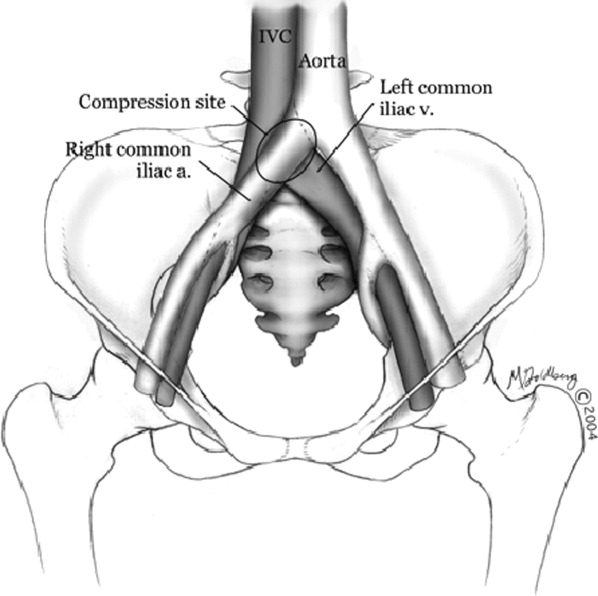

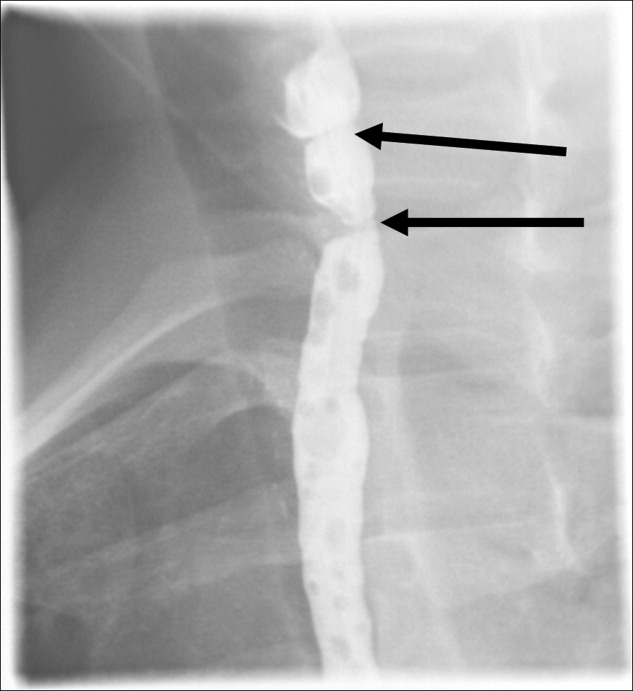

Hospitalists frequently diagnose and treat lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Patients presenting with acute DVT or chronic venous stasis of the left leg can have an underlying anatomic anomaly known as iliac vein compression syndrome (ICS), May‐Thurner syndrome, or Cockett syndrome in Europe. In this condition, the right iliac artery overlies the left iliac vein, causing extrinsic compression of the vein (Figure 1). 1 This compression and accompanying intraluminal changes predisposes patients to left‐sided lower extremity DVT.2 Failure to recognize and treat this anomaly in patients with acute thrombosis can result in serious vascular sequelae and chronic left leg symptoms.3 A high clinical suspicion should be maintained in young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. The following report is a case of ICS in a young male recognized and treated early by aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

11‐ Grunwald et al.

Case Report

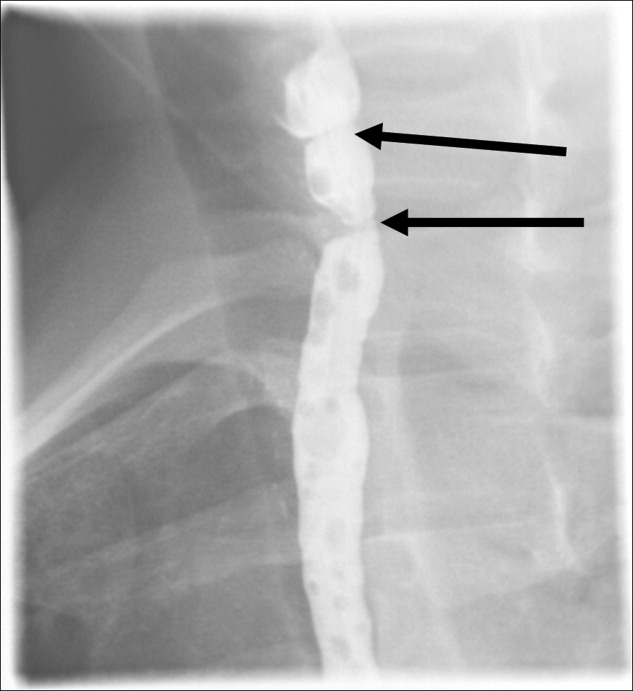

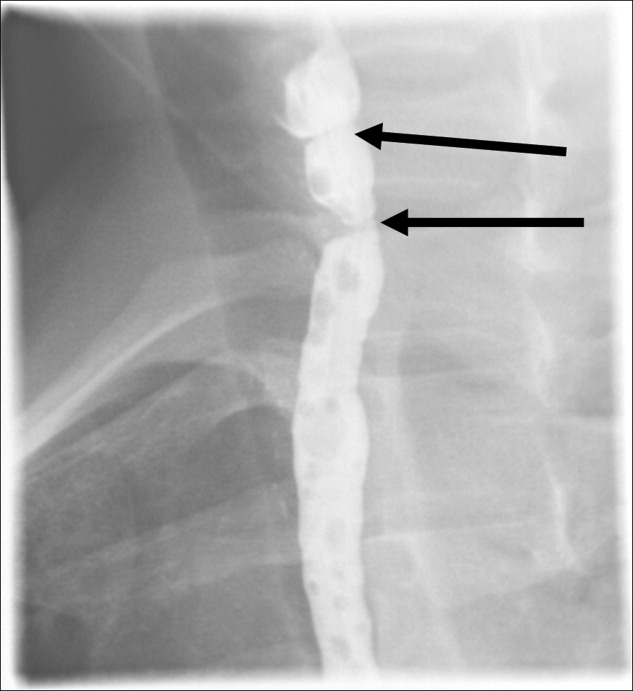

A 19‐year‐old man presented to the ER with sudden onset of left lower extremity swelling and pain 5 days after a fall. He had no known risk factors for DVT. On physical examination his left leg was dusky, swollen, and tender from his groin to his ankle, with good arterial pulses. Duplex ultra‐sonogram of the leg showed a clot in the femoral vein extending up the popliteal vein. Following a venogram, he underwent mechanical thrombectomy and regional thrombolysis. A repeat venogram showed an irregular narrowing of the left iliac vein and a tubular filling defect at the junction of the inferior vena cava and common iliac veins, suggestive of external compression from the right common iliac artery. The patient underwent successful angioplasty and stenting of the common iliac vein. He was treated with intravenous heparin, warfarin and clopidogrel. His hypercoagulable work‐up was inconclusive.

Discussion

In 1956, May and Thurner 1 brought clinical attention to ICS. They hypothesized that an abnormal compression of the left iliac vein by an overriding right iliac arterypresent in 22% of a series of 430 cadaversled to an intraluminal filling defect in the vein. The chronic extrinsic compression and pulsing force from the overlying artery results in endothelial irritation and formation of venous spurs (fibrous vascular lesions) in the intimal layer of the vein.1 Following the principles of Virchow's triad, this endothelial injury propagates the formation of a thrombus. Subsequent studies by Kim et al.4 suggest that there are 3 stages involved in the pathogenesis of thrombosis in ICS: asymptomatic vein compression, venous spur formation, and finally DVT formation.4, 5 It is estimated that 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT each year.5, 6

Patients with ICS may present to the emergency or ambulatory setting in either an acute or chronic phase. The acute phase is the actual episode of thrombosis. Symptoms include left leg pain and swelling up to the groin. In rare cases, pulmonary emboli may be the initial presentation. A lifelong chronic phase can follow if undiagnosed, resulting in pain and swelling of the entire left leg, venous claudication, recurrent thrombosis, pigmentation changes, and ulceration. 3

The typical ICS patient is a woman between 18 and 30 years old, 3 possibly due to the developmental changes in the pelvic structures in preparation for child‐bearing.2 Many patients also present after pregnancy; increased lordosis during pregnancy may put additional strain on the anatomic lesion.3 Nevertheless, Steinberg and Jacocks7 reported that out of 127 patients, 38 (30%) were male. Thus, it is critical not to overlook ICS as a possible cause of thrombosis in male patients.

The urgency in diagnosing this anatomic variation lies in the distinct need for more aggressive treatment than that required for a typical DVT. While Doppler ultrasound is typically the first diagnostic test performed in this patient population, it is not specific. For patients with physical exam findings highly suspicious of ICS, venography and magnetic resonance venography are superior modalities to make a definitive diagnosis of the syndrome. 8 In ICS, these studies will reveal left common iliac vein narrowing with intraluminal changes suggestive of spur formation.2

Due to the mechanical nature of ICS pathology, anticoagulation therapy alone is ineffective. ICS prevents recanalization in 70% to 80% of patients and up to 40% will have continued clot propagation. 5, 7 More aggressive treatment using endovascular techniques such as the combination of thrombectomy, angioplasty, and intraluminal stenting have proven to be the most efficacious treatment modality for ICS.9 A study by AbuRahma et al.10 demonstrated that one year following this aggressive combination, patency rate was 83% (vs. 24% following thrombectomy alone).

Conclusion

The anatomic anomaly present in ICS was identified by CT in as many as two‐thirds of an asymptomatic patient population studied by Kibbe et al. 12 Although a common structural anomaly, it is important to note that only 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT annually. ICS should be included in the differential diagnosis of all young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. If the mechanical compression is not diagnosed and treated, the syndrome can develop into a life‐long chronic phase with multiple complications.2 It is therefore critical that aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions be implemented immediately upon suspicion of ICS.

- , . A vascular spur in the vena iliaca communis sinistra as a cause of predominantly left‐sided thrombosis of the pelvic veins. Z Kreislaufforsch. 1956;45:912–922.

- , , , , . Compression of the left common iliac vein in asymptomatic subjects and patients with left iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:366–370; quiz 71.

- . The iliac compression syndrome alias ‘Iliofemoral thrombosis’ or ‘white leg’. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59:360–361.

- , , . Venographic anatomy, technique and interpretation. Pheripheral Vascular Imaging and Intervention. St. Louis (MO): Mosby‐Year Book; 1992. p. 269–349.

- , , , , . Symptomatic ileofemoral DVT after onset of oral contraceptive use in women with previously undiagnosed May‐Thurner Syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:697–703.

- , , . A prospective study of the incidence of deep vein thrombosis within a defined urban population. J Intern Med. 1992;232:152–160.

- , . May‐Thurner syndrome: a previously unreported variant. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7:577–581.

- , , , , , . Diagnosis and endovascular treatment of iliocaval compression syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:106–113.

- , , , et al. Endovascular management of iliac vein compression (May‐Thurner) syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:823–836.

- , , , . Iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: conventional therapy versus lysis and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. Ann Surg. 2001;233:752–760.

- , , . Endovascular management of May‐Thurner Syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1523–1524.

- , , , , , . Iliac vein compression in an asymptomatic patient population. J Vasc Surg. 2004:39:937–943.

Hospitalists frequently diagnose and treat lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Patients presenting with acute DVT or chronic venous stasis of the left leg can have an underlying anatomic anomaly known as iliac vein compression syndrome (ICS), May‐Thurner syndrome, or Cockett syndrome in Europe. In this condition, the right iliac artery overlies the left iliac vein, causing extrinsic compression of the vein (Figure 1). 1 This compression and accompanying intraluminal changes predisposes patients to left‐sided lower extremity DVT.2 Failure to recognize and treat this anomaly in patients with acute thrombosis can result in serious vascular sequelae and chronic left leg symptoms.3 A high clinical suspicion should be maintained in young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. The following report is a case of ICS in a young male recognized and treated early by aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

11‐ Grunwald et al.

Case Report

A 19‐year‐old man presented to the ER with sudden onset of left lower extremity swelling and pain 5 days after a fall. He had no known risk factors for DVT. On physical examination his left leg was dusky, swollen, and tender from his groin to his ankle, with good arterial pulses. Duplex ultra‐sonogram of the leg showed a clot in the femoral vein extending up the popliteal vein. Following a venogram, he underwent mechanical thrombectomy and regional thrombolysis. A repeat venogram showed an irregular narrowing of the left iliac vein and a tubular filling defect at the junction of the inferior vena cava and common iliac veins, suggestive of external compression from the right common iliac artery. The patient underwent successful angioplasty and stenting of the common iliac vein. He was treated with intravenous heparin, warfarin and clopidogrel. His hypercoagulable work‐up was inconclusive.

Discussion

In 1956, May and Thurner 1 brought clinical attention to ICS. They hypothesized that an abnormal compression of the left iliac vein by an overriding right iliac arterypresent in 22% of a series of 430 cadaversled to an intraluminal filling defect in the vein. The chronic extrinsic compression and pulsing force from the overlying artery results in endothelial irritation and formation of venous spurs (fibrous vascular lesions) in the intimal layer of the vein.1 Following the principles of Virchow's triad, this endothelial injury propagates the formation of a thrombus. Subsequent studies by Kim et al.4 suggest that there are 3 stages involved in the pathogenesis of thrombosis in ICS: asymptomatic vein compression, venous spur formation, and finally DVT formation.4, 5 It is estimated that 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT each year.5, 6

Patients with ICS may present to the emergency or ambulatory setting in either an acute or chronic phase. The acute phase is the actual episode of thrombosis. Symptoms include left leg pain and swelling up to the groin. In rare cases, pulmonary emboli may be the initial presentation. A lifelong chronic phase can follow if undiagnosed, resulting in pain and swelling of the entire left leg, venous claudication, recurrent thrombosis, pigmentation changes, and ulceration. 3

The typical ICS patient is a woman between 18 and 30 years old, 3 possibly due to the developmental changes in the pelvic structures in preparation for child‐bearing.2 Many patients also present after pregnancy; increased lordosis during pregnancy may put additional strain on the anatomic lesion.3 Nevertheless, Steinberg and Jacocks7 reported that out of 127 patients, 38 (30%) were male. Thus, it is critical not to overlook ICS as a possible cause of thrombosis in male patients.

The urgency in diagnosing this anatomic variation lies in the distinct need for more aggressive treatment than that required for a typical DVT. While Doppler ultrasound is typically the first diagnostic test performed in this patient population, it is not specific. For patients with physical exam findings highly suspicious of ICS, venography and magnetic resonance venography are superior modalities to make a definitive diagnosis of the syndrome. 8 In ICS, these studies will reveal left common iliac vein narrowing with intraluminal changes suggestive of spur formation.2

Due to the mechanical nature of ICS pathology, anticoagulation therapy alone is ineffective. ICS prevents recanalization in 70% to 80% of patients and up to 40% will have continued clot propagation. 5, 7 More aggressive treatment using endovascular techniques such as the combination of thrombectomy, angioplasty, and intraluminal stenting have proven to be the most efficacious treatment modality for ICS.9 A study by AbuRahma et al.10 demonstrated that one year following this aggressive combination, patency rate was 83% (vs. 24% following thrombectomy alone).

Conclusion

The anatomic anomaly present in ICS was identified by CT in as many as two‐thirds of an asymptomatic patient population studied by Kibbe et al. 12 Although a common structural anomaly, it is important to note that only 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT annually. ICS should be included in the differential diagnosis of all young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. If the mechanical compression is not diagnosed and treated, the syndrome can develop into a life‐long chronic phase with multiple complications.2 It is therefore critical that aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions be implemented immediately upon suspicion of ICS.

Hospitalists frequently diagnose and treat lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT). Patients presenting with acute DVT or chronic venous stasis of the left leg can have an underlying anatomic anomaly known as iliac vein compression syndrome (ICS), May‐Thurner syndrome, or Cockett syndrome in Europe. In this condition, the right iliac artery overlies the left iliac vein, causing extrinsic compression of the vein (Figure 1). 1 This compression and accompanying intraluminal changes predisposes patients to left‐sided lower extremity DVT.2 Failure to recognize and treat this anomaly in patients with acute thrombosis can result in serious vascular sequelae and chronic left leg symptoms.3 A high clinical suspicion should be maintained in young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. The following report is a case of ICS in a young male recognized and treated early by aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

11‐ Grunwald et al.

Case Report

A 19‐year‐old man presented to the ER with sudden onset of left lower extremity swelling and pain 5 days after a fall. He had no known risk factors for DVT. On physical examination his left leg was dusky, swollen, and tender from his groin to his ankle, with good arterial pulses. Duplex ultra‐sonogram of the leg showed a clot in the femoral vein extending up the popliteal vein. Following a venogram, he underwent mechanical thrombectomy and regional thrombolysis. A repeat venogram showed an irregular narrowing of the left iliac vein and a tubular filling defect at the junction of the inferior vena cava and common iliac veins, suggestive of external compression from the right common iliac artery. The patient underwent successful angioplasty and stenting of the common iliac vein. He was treated with intravenous heparin, warfarin and clopidogrel. His hypercoagulable work‐up was inconclusive.

Discussion

In 1956, May and Thurner 1 brought clinical attention to ICS. They hypothesized that an abnormal compression of the left iliac vein by an overriding right iliac arterypresent in 22% of a series of 430 cadaversled to an intraluminal filling defect in the vein. The chronic extrinsic compression and pulsing force from the overlying artery results in endothelial irritation and formation of venous spurs (fibrous vascular lesions) in the intimal layer of the vein.1 Following the principles of Virchow's triad, this endothelial injury propagates the formation of a thrombus. Subsequent studies by Kim et al.4 suggest that there are 3 stages involved in the pathogenesis of thrombosis in ICS: asymptomatic vein compression, venous spur formation, and finally DVT formation.4, 5 It is estimated that 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT each year.5, 6

Patients with ICS may present to the emergency or ambulatory setting in either an acute or chronic phase. The acute phase is the actual episode of thrombosis. Symptoms include left leg pain and swelling up to the groin. In rare cases, pulmonary emboli may be the initial presentation. A lifelong chronic phase can follow if undiagnosed, resulting in pain and swelling of the entire left leg, venous claudication, recurrent thrombosis, pigmentation changes, and ulceration. 3

The typical ICS patient is a woman between 18 and 30 years old, 3 possibly due to the developmental changes in the pelvic structures in preparation for child‐bearing.2 Many patients also present after pregnancy; increased lordosis during pregnancy may put additional strain on the anatomic lesion.3 Nevertheless, Steinberg and Jacocks7 reported that out of 127 patients, 38 (30%) were male. Thus, it is critical not to overlook ICS as a possible cause of thrombosis in male patients.

The urgency in diagnosing this anatomic variation lies in the distinct need for more aggressive treatment than that required for a typical DVT. While Doppler ultrasound is typically the first diagnostic test performed in this patient population, it is not specific. For patients with physical exam findings highly suspicious of ICS, venography and magnetic resonance venography are superior modalities to make a definitive diagnosis of the syndrome. 8 In ICS, these studies will reveal left common iliac vein narrowing with intraluminal changes suggestive of spur formation.2

Due to the mechanical nature of ICS pathology, anticoagulation therapy alone is ineffective. ICS prevents recanalization in 70% to 80% of patients and up to 40% will have continued clot propagation. 5, 7 More aggressive treatment using endovascular techniques such as the combination of thrombectomy, angioplasty, and intraluminal stenting have proven to be the most efficacious treatment modality for ICS.9 A study by AbuRahma et al.10 demonstrated that one year following this aggressive combination, patency rate was 83% (vs. 24% following thrombectomy alone).

Conclusion

The anatomic anomaly present in ICS was identified by CT in as many as two‐thirds of an asymptomatic patient population studied by Kibbe et al. 12 Although a common structural anomaly, it is important to note that only 1 to 3 out of 1000 individuals with this malformation develop DVT annually. ICS should be included in the differential diagnosis of all young individuals presenting with proximal left leg DVT with or without hypercoagulable risk factors. If the mechanical compression is not diagnosed and treated, the syndrome can develop into a life‐long chronic phase with multiple complications.2 It is therefore critical that aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic interventions be implemented immediately upon suspicion of ICS.

- , . A vascular spur in the vena iliaca communis sinistra as a cause of predominantly left‐sided thrombosis of the pelvic veins. Z Kreislaufforsch. 1956;45:912–922.

- , , , , . Compression of the left common iliac vein in asymptomatic subjects and patients with left iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:366–370; quiz 71.

- . The iliac compression syndrome alias ‘Iliofemoral thrombosis’ or ‘white leg’. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59:360–361.

- , , . Venographic anatomy, technique and interpretation. Pheripheral Vascular Imaging and Intervention. St. Louis (MO): Mosby‐Year Book; 1992. p. 269–349.

- , , , , . Symptomatic ileofemoral DVT after onset of oral contraceptive use in women with previously undiagnosed May‐Thurner Syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:697–703.

- , , . A prospective study of the incidence of deep vein thrombosis within a defined urban population. J Intern Med. 1992;232:152–160.

- , . May‐Thurner syndrome: a previously unreported variant. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7:577–581.

- , , , , , . Diagnosis and endovascular treatment of iliocaval compression syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:106–113.

- , , , et al. Endovascular management of iliac vein compression (May‐Thurner) syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:823–836.

- , , , . Iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: conventional therapy versus lysis and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. Ann Surg. 2001;233:752–760.

- , , . Endovascular management of May‐Thurner Syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1523–1524.

- , , , , , . Iliac vein compression in an asymptomatic patient population. J Vasc Surg. 2004:39:937–943.

- , . A vascular spur in the vena iliaca communis sinistra as a cause of predominantly left‐sided thrombosis of the pelvic veins. Z Kreislaufforsch. 1956;45:912–922.

- , , , , . Compression of the left common iliac vein in asymptomatic subjects and patients with left iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:366–370; quiz 71.

- . The iliac compression syndrome alias ‘Iliofemoral thrombosis’ or ‘white leg’. Proc R Soc Med. 1966;59:360–361.

- , , . Venographic anatomy, technique and interpretation. Pheripheral Vascular Imaging and Intervention. St. Louis (MO): Mosby‐Year Book; 1992. p. 269–349.

- , , , , . Symptomatic ileofemoral DVT after onset of oral contraceptive use in women with previously undiagnosed May‐Thurner Syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:697–703.

- , , . A prospective study of the incidence of deep vein thrombosis within a defined urban population. J Intern Med. 1992;232:152–160.

- , . May‐Thurner syndrome: a previously unreported variant. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7:577–581.

- , , , , , . Diagnosis and endovascular treatment of iliocaval compression syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:106–113.

- , , , et al. Endovascular management of iliac vein compression (May‐Thurner) syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:823–836.

- , , , . Iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: conventional therapy versus lysis and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. Ann Surg. 2001;233:752–760.

- , , . Endovascular management of May‐Thurner Syndrome. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1523–1524.

- , , , , , . Iliac vein compression in an asymptomatic patient population. J Vasc Surg. 2004:39:937–943.

Stevens‐Johnson and mycoplasma pneumoniae: A scary duo

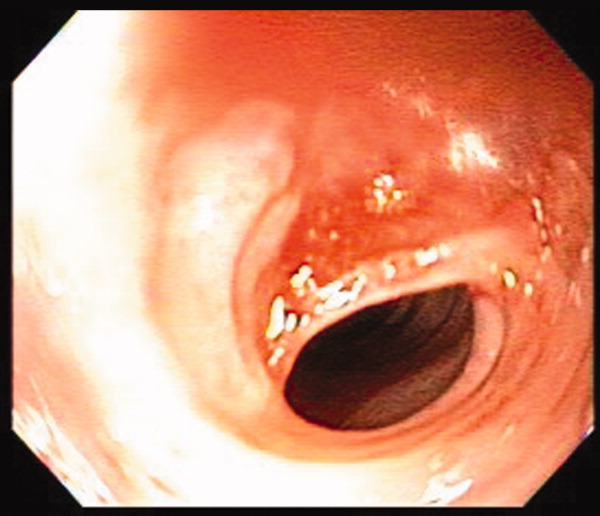

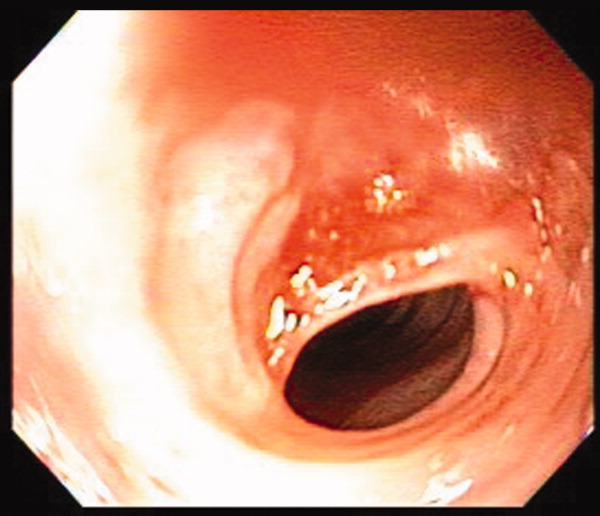

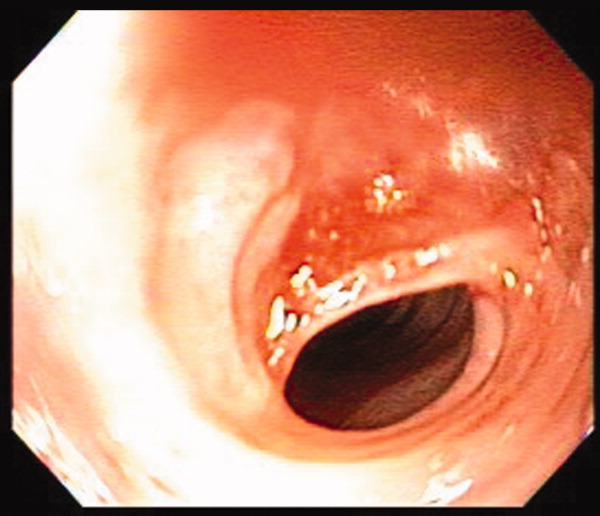

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.

New Research Target

A report in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine shows macrolide and quinolone antibiotics are associated with similar rates of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease (AECOPD). The lead author says the study could be a precursor to, say, an intrepid HM researcher working on a randomized trial of the antibiotics’ effectiveness.

“It’s a perfect thing for hospitalists to study because they’re the ones treating it,” says Michael Rothberg, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, and lead author of "Comparative Effectiveness of Macrolides and Quinolones for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)."

The retrospective cohort review reported that out of nearly 20,000 patients, 6,139 (31%) were treated initially with a macrolide and 13,469 (69%) with a quinolone. “Those who received macrolides had a lower risk of treatment failure (6.8% vs. 8.1%, p<0.01), a finding that was attenuated after multivariable adjustment (OR=0.89, 95% CI 0.78-1.01), and disappeared in a grouped-treatment analysis (OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.75-1.35),” the authors wrote. The study found no differences in adjusted length of stay or cost. However, antibiotic-associated diarrhea was more common with quinolones (1.2% vs. 0.6%, p<0.001).

Dr. Rothberg, who is affiliated with the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., says the data, while a point in the right direction, should be viewed as a first step in doing more search to determine the best treatment for AECOPD.

“If you look at the guidelines, the recommendations are all over the map,” Dr. Rothberg says. “This is really because there are no randomized trials in COPD patients. … There are so many unanswered questions. There’s been so much focus on pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. COPD kind of has a dearth of research.”

Dr. Rothberg hopes to further that research via the COPD Outcomes-Based Network for Clinical Effectiveness & Research Translation (CONCERT), a team of physicians and researchers from centers around the country who are advocating for improvements to COPD treatment. Baystate is one of CONCERT’s outposts.

A report in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine shows macrolide and quinolone antibiotics are associated with similar rates of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease (AECOPD). The lead author says the study could be a precursor to, say, an intrepid HM researcher working on a randomized trial of the antibiotics’ effectiveness.

“It’s a perfect thing for hospitalists to study because they’re the ones treating it,” says Michael Rothberg, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, and lead author of "Comparative Effectiveness of Macrolides and Quinolones for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)."

The retrospective cohort review reported that out of nearly 20,000 patients, 6,139 (31%) were treated initially with a macrolide and 13,469 (69%) with a quinolone. “Those who received macrolides had a lower risk of treatment failure (6.8% vs. 8.1%, p<0.01), a finding that was attenuated after multivariable adjustment (OR=0.89, 95% CI 0.78-1.01), and disappeared in a grouped-treatment analysis (OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.75-1.35),” the authors wrote. The study found no differences in adjusted length of stay or cost. However, antibiotic-associated diarrhea was more common with quinolones (1.2% vs. 0.6%, p<0.001).

Dr. Rothberg, who is affiliated with the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., says the data, while a point in the right direction, should be viewed as a first step in doing more search to determine the best treatment for AECOPD.

“If you look at the guidelines, the recommendations are all over the map,” Dr. Rothberg says. “This is really because there are no randomized trials in COPD patients. … There are so many unanswered questions. There’s been so much focus on pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. COPD kind of has a dearth of research.”

Dr. Rothberg hopes to further that research via the COPD Outcomes-Based Network for Clinical Effectiveness & Research Translation (CONCERT), a team of physicians and researchers from centers around the country who are advocating for improvements to COPD treatment. Baystate is one of CONCERT’s outposts.

A report in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine shows macrolide and quinolone antibiotics are associated with similar rates of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic pulmonary disease (AECOPD). The lead author says the study could be a precursor to, say, an intrepid HM researcher working on a randomized trial of the antibiotics’ effectiveness.

“It’s a perfect thing for hospitalists to study because they’re the ones treating it,” says Michael Rothberg, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, and lead author of "Comparative Effectiveness of Macrolides and Quinolones for Patients Hospitalized with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD)."

The retrospective cohort review reported that out of nearly 20,000 patients, 6,139 (31%) were treated initially with a macrolide and 13,469 (69%) with a quinolone. “Those who received macrolides had a lower risk of treatment failure (6.8% vs. 8.1%, p<0.01), a finding that was attenuated after multivariable adjustment (OR=0.89, 95% CI 0.78-1.01), and disappeared in a grouped-treatment analysis (OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.75-1.35),” the authors wrote. The study found no differences in adjusted length of stay or cost. However, antibiotic-associated diarrhea was more common with quinolones (1.2% vs. 0.6%, p<0.001).

Dr. Rothberg, who is affiliated with the Center for Quality of Care Research at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., says the data, while a point in the right direction, should be viewed as a first step in doing more search to determine the best treatment for AECOPD.

“If you look at the guidelines, the recommendations are all over the map,” Dr. Rothberg says. “This is really because there are no randomized trials in COPD patients. … There are so many unanswered questions. There’s been so much focus on pneumonia, heart failure, and acute myocardial infarction. COPD kind of has a dearth of research.”

Dr. Rothberg hopes to further that research via the COPD Outcomes-Based Network for Clinical Effectiveness & Research Translation (CONCERT), a team of physicians and researchers from centers around the country who are advocating for improvements to COPD treatment. Baystate is one of CONCERT’s outposts.

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: Is glucose variability associated with increased mortality independent of mean glucose values in intensive-care-unit (ICU) patients on a strict glucose-control algorithm?

Background: Initial studies demonstrating that strict glycemic control in the ICU improves mortality have not been reproduced in more recent trials and meta-analyses. This inconsistency may be due to unstudied aspects of glycemic control, such as glucose variability.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Eighteen-bed medical/surgical ICU in a teaching hospital in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Synopsis: Data were collected on 5,728 patients admitted to the ICU from January 2004 to December 2007, all of whom were treated with a computerized intensive insulin protocol. Mean glucose, standard deviation in glucose, and mean absolute glucose change per hour (glucose variability) were calculated for each patient stay in the ICU. The results from these three calculated values were divided into quartiles and evaluated for their predictive value of ICU death and in-hospital death.

Within each mean glucose quartile, the uppermost glucose variability quartile was associated with increased risk of death. Compared with the lowest glucose variability quartile, the highest quartile had a 3.3-fold increased risk of ICU death and a 2.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital death. Patients in the highest glucose quartile with the highest glucose variability had a 12.4-fold increased risk of ICU death.

Bottom line: High glucose variability is associated with increased ICU and in-hospital mortality independent of mean glucose values in patients on a strict glucose control algorithm.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Dimitriy Levin, MD, Jeffrey Carter, MD, Erin Egan, MD, JD, Jonathan Pell, MD, Laura Rosenthal, MSN, ACNP, Nichole Zehnder, MD, Hospital Medicine Group, University of Colorado Denver

For more reviews of HM-related literature, visit our website.

Clinical question: Is glucose variability associated with increased mortality independent of mean glucose values in intensive-care-unit (ICU) patients on a strict glucose-control algorithm?

Background: Initial studies demonstrating that strict glycemic control in the ICU improves mortality have not been reproduced in more recent trials and meta-analyses. This inconsistency may be due to unstudied aspects of glycemic control, such as glucose variability.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Eighteen-bed medical/surgical ICU in a teaching hospital in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Synopsis: Data were collected on 5,728 patients admitted to the ICU from January 2004 to December 2007, all of whom were treated with a computerized intensive insulin protocol. Mean glucose, standard deviation in glucose, and mean absolute glucose change per hour (glucose variability) were calculated for each patient stay in the ICU. The results from these three calculated values were divided into quartiles and evaluated for their predictive value of ICU death and in-hospital death.

Within each mean glucose quartile, the uppermost glucose variability quartile was associated with increased risk of death. Compared with the lowest glucose variability quartile, the highest quartile had a 3.3-fold increased risk of ICU death and a 2.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital death. Patients in the highest glucose quartile with the highest glucose variability had a 12.4-fold increased risk of ICU death.

Bottom line: High glucose variability is associated with increased ICU and in-hospital mortality independent of mean glucose values in patients on a strict glucose control algorithm.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Dimitriy Levin, MD, Jeffrey Carter, MD, Erin Egan, MD, JD, Jonathan Pell, MD, Laura Rosenthal, MSN, ACNP, Nichole Zehnder, MD, Hospital Medicine Group, University of Colorado Denver

For more reviews of HM-related literature, visit our website.

Clinical question: Is glucose variability associated with increased mortality independent of mean glucose values in intensive-care-unit (ICU) patients on a strict glucose-control algorithm?

Background: Initial studies demonstrating that strict glycemic control in the ICU improves mortality have not been reproduced in more recent trials and meta-analyses. This inconsistency may be due to unstudied aspects of glycemic control, such as glucose variability.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Eighteen-bed medical/surgical ICU in a teaching hospital in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Synopsis: Data were collected on 5,728 patients admitted to the ICU from January 2004 to December 2007, all of whom were treated with a computerized intensive insulin protocol. Mean glucose, standard deviation in glucose, and mean absolute glucose change per hour (glucose variability) were calculated for each patient stay in the ICU. The results from these three calculated values were divided into quartiles and evaluated for their predictive value of ICU death and in-hospital death.

Within each mean glucose quartile, the uppermost glucose variability quartile was associated with increased risk of death. Compared with the lowest glucose variability quartile, the highest quartile had a 3.3-fold increased risk of ICU death and a 2.8-fold increased risk of in-hospital death. Patients in the highest glucose quartile with the highest glucose variability had a 12.4-fold increased risk of ICU death.

Bottom line: High glucose variability is associated with increased ICU and in-hospital mortality independent of mean glucose values in patients on a strict glucose control algorithm.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Dimitriy Levin, MD, Jeffrey Carter, MD, Erin Egan, MD, JD, Jonathan Pell, MD, Laura Rosenthal, MSN, ACNP, Nichole Zehnder, MD, Hospital Medicine Group, University of Colorado Denver

For more reviews of HM-related literature, visit our website.

Insurance Status and Hospital Care

With about 1 in 5 working‐age Americans (age 18‐64 years) currently uninsured and a large number relying on Medicaid, adequate access to quality health care services is becoming increasingly difficult.1 Substantial literature has accumulated over the years suggesting that access and quality in health care are closely linked to an individual's health insurance status.211 Some studies indicate that being uninsured or publicly insured is associated with negative health consequences.12, 13 Although the Medicaid program has improved access for qualifying low‐income individuals, significant gaps in access and quality remain.2, 5, 11, 1419 These issues are likely to become more pervasive should there be further modifications to state Medicaid funding in response to the unfolding economic crisis.

Although numerous studies have focused on insurance‐related disparities in the outpatient setting, few nationally representative studies have examined such disparities among hospitalized patients. A cross‐sectional study of a large hospital database from 1987 reported higher risk‐adjusted in‐hospital mortality, shorter length of stay (LOS), and lower procedure use among uninsured patients.9 A more recent analysis, limited to patients admitted with stroke, reported significant variation in hospital care associated with insurance status.15 Other studies reporting myocardial infarction registry and quality improvement program data are biased by the self‐selection of large urban teaching hospitals.1618 To our knowledge, no nationally representative study has focused on the impact of insurance coverage on hospital care for common medical conditions among working‐age Americans, the fastest growing segment of the uninsured population.

To address this gap in knowledge, we analyzed a nationally representative hospital database to determine whether there are significant insurance‐related disparities in in‐hospital mortality, LOS, and cost per hospitalization for 3 common medical conditions among working‐age adults, and, if present, to determine whether these disparities are due to differences in disease severity and comorbidities, and whether these disparities are affected by the proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients receiving care in each hospital.

Methods

Design and Subjects

We examined data from the 2005 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), a nationally representative database of hospital inpatient stays maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP).20, 21 The NIS is a stratified probability sample of 20% of all US community hospitals, including public hospitals, academic medical centers, and specialty hospitals. Long‐term care hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, and alcoholism/chemical‐dependency treatment facilities are excluded. The 2005 NIS contains data on 7,995,048 discharges from 1054 hospitals located in 37 States and is designed to be representative of all acute care discharges from all US community hospitals.21

We identified discharges with a principal diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), stroke, and pneumonia using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes specified in the AHRQ definitions of Inpatient Quality Indicators (Supporting Information Appendix).22 These 3 conditions are among the leading causes of noncancer inpatient deaths in patients under 65 years old,23 and evidence suggests that high mortality may be associated with deficiencies in the quality of inpatient care.24

We confined our analysis to patients 18 to 64 years of age, since this population is most at risk of being uninsured or underinsured.25 We excluded pregnant women because they account for an unusually high proportion of uninsured discharges and were relatively few in our cohort.26 In addition, we excluded patients transferred to another acute care hospital and patients missing payer source and discharge disposition. Our study protocol was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee.

Study Variables

We categorized insurance status as privately insured, uninsured, Medicaid, or Medicare. We defined privately insured patients as those having either Blue Cross or another commercial carrier listed as the primary payer and uninsured patients as those having either no charge or self‐pay listed as the primary payer.27 Other governmental payer categories were noted to share several characteristics with Medicare patients and comprised only a small proportion of the sample, and were thus included with Medicare. In order to account for NIS's sampling scheme and accurately apply sample weights in our analysis, we used Medicare as a separate category. However, since Medicare patients age 18 to 64 years represent a fundamentally different population that is primarily disabled or very ill, only results of privately insured, uninsured, and Medicaid patients are reported.

We selected in‐hospital mortality as the outcome measure and LOS and cost per hospitalization as measures of resource utilization. The NIS includes a binary indicator variable for in‐hospital mortality and specifies inpatient LOS in integers, with same‐day stays coded as 0. NIS's cost estimates are based on hospital cost reports submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. To test the validity of our cost analyses, we performed parallel analyses using hospital charges as a measure of utilization (charges include hospital overhead, charity care, and bad debt). The resulting adjusted ratios differed little from cost ratios and we opted to report only the details of our cost analyses.

In order to assess the independent association between insurance status and the outcome measures listed above, we selected covariates for inclusion in multivariable models based on the existing literature. Patient covariates included: age group (18‐34 years, 35‐49 years, 50‐64 years), sex (male/female), race/ethnicity (non‐Hispanic white, non‐Hispanic black, Hispanic, other, missing), median income by zip code of residence (less than $37,000, $37,000‐$45,999, $46,000‐$60,999, $61,000 or more), admission through the emergency department (yes/no), admission on a weekend (yes/no), measures of disease severity, and comorbidity indicators. Measures of disease severity specific to each outcome are assigned in the NIS using criteria developed by Medstat (Medstat Disease Staging Software Version 5.2, Thomson Medstat Inc., Ann Arbor, MI). Severity is categorized into 5 levels, with a higher level indicating greater risk. We recorded comorbidities for each patient in our sample using HCUP Comorbidity Software, Version 3.2 (

Hospital covariates included: bed size (small, medium, large), ownership/control (private, government, private or government), geographic region (northeast, midwest, south, west), teaching status (teaching, non‐teaching), and the proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients (combined) admitted to each hospital for AMI, stroke, or pneumonia. The actual number of hospital beds in each bed size category varies according to a hospital's geographic region and teaching status.27 Ownership/control, geographic region, and teaching status are assigned according to information from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey of Hospitals. The proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients admitted to each hospital was found to have a nonmonotonic relationship with the outcomes being assessed and was thus treated as a 6‐level categorical variable with the following levels: 0% to 10%, 11% to 20%, 21% to 30%, 31% to 40%, 41% to 50%, and 51% to 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were constructed at the patient level and differences in proportions were evaluated with the chi‐square test. We employed direct standardization, using the age and sex distribution of the entire cohort, to compute age‐standardized and sex‐standardized estimates for each insurance group and compared them using the chi‐square test for in‐hospital mortality and t test for log transformed LOS and cost per hospitalization. For each condition, we developed multivariable logistic regression models for in‐hospital mortality and multivariable linear regression models for log transformed LOS and cost. The patient was the unit of analysis in all models.

In order to elucidate the contribution of disease severity and comorbidities and the proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients admitted to each hospital, we fitted 3 sequential models for each outcome measure: Model 1 adjusted for patient sociodemographic characteristics and hospital characteristics with the exception of the covariate for the proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients, Model 2 adjusted for all covariates in the preceding model as well as patients' comorbidities and severity of principal diagnosis, and Model 3 adjusted for all previously mentioned covariates as well as the proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients admitted to each hospital. We excluded patients who died during hospitalization from the models for LOS and cost. We exponentiated the effect estimates from the log transformed linear regression models so that the adjusted ratio represents the percentage change in the mean LOS or mean cost.

To determine whether the association between patients' insurance status and in‐hospital mortality was modified by seeking care in hospitals treating a smaller or larger proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients, we entered an interaction term for insurance status and proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients in the final models (Model 3) for our primary outcome of in‐hospital mortality. However, since no significant interaction was found for any of the 3 conditions, this term was removed from the models and results from the interaction models are not described. In order to assess model specification for the linear regression models, we evaluated the normality of model residuals and found that these were approximately normally distributed. Lastly, we attempted to test the robustness of our analyses by creating fixed effects models that controlled for hospital site but were unable to do so due to the computational limitations of available software packages that could not render fixed effects models with more than 1000 hospital sites.

For all variables except race/ethnicity, data were missing for less than 3% of patients, so we excluded these individuals from adjusted analyses. However, race/ethnicity data were missing for 29% of the sample and were analyzed in 3 different ways, namely, with the missing data treated as a separate covariate level, with the missing data removed from the analysis, and with the missing data assigned to the majority covariate level (white race). The results of our analysis were unchanged no matter how the missing values were assigned. As a result, missing values for race/ethnicity were treated as a separate covariate level in the final analysis.15 Sociodemographic characteristics of patients with missing race/ethnicity information were similar to those with complete data.

We used SUDAAN (Release 9.0.1, Research Triangle Institute, NC) to account for NIS's sampling scheme and generalized estimating equations to adjust for the clustering of patients within hospitals and hospitals within sampling strata.29 In order to account for NIS's stratified probability sampling scheme, SUDAAN uses Taylor series linearization for robust variance estimation of descriptive statistics and regression parameters.30, 31 We present 2‐tailed P values or 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all statistical comparisons.

Results

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

The final cohort comprised of 154,381 patients discharged from 1018 hospitals in 37 states during calendar year 2005 (Table 1). This cohort was representative of 755,346 working‐age Americans, representing approximately 225,947 cases of AMI (29.9%), 151,812 cases of stroke (20.1%), and 377,588 cases of pneumonia (50.0%). Of these patients, 47.5% were privately insured, 12.0% were uninsured, 17.0% received Medicaid, and 23.5% were assigned to Medicare. Compared with the privately insured, uninsured and Medicaid patients were generally younger, less likely to be white, more likely to have lower income, and more likely to be admitted through the emergency department. Of the 1018 hospitals included in our study, close to half (44.3%) were small, with bedsize ranging from 24 to 249. A large number of hospitals were located in the South (39.9%), and 14.9% were designated teaching hospitals.

| Characteristic* | Privately insured (n = 73,256) | Uninsured (n = 18,531) | Medicaid (n = 26,222) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Principal diagnosis (%) | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 36.7 | 31.2 | 19.7 |

| Stroke | 20.6 | 23.7 | 19.9 |

| Pneumonia | 42.7 | 45.2 | 60.4 |

| Age group (%) | |||

| 18‐34 years | 6.8 | 13.0 | 13.7 |

| 35‐49 years | 27.6 | 36.9 | 33.2 |

| 50‐64 years | 65.7 | 50.1 | 53.2 |

| Male sex (%) | 59.3 | 62.3 | 46.6 |

| Race or ethnicity (%) | |||

| White | 55.7 | 41.5 | 38.0 |

| Black | 7.6 | 14.8 | 16.6 |

| Hispanic | 4.8 | 10.5 | 10.4 |

| Other race | 3.6 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

| Missing | 28.4 | 29.0 | 29.7 |

| Median income by ZIP code (%) | |||

| <$37,000 | 21.5 | 36.7 | 43.0 |

| $37,000‐$45,999 | 25.2 | 27.8 | 27.1 |

| $46,000‐$60,999 | 26.3 | 20.3 | 17.6 |

| $61,000 | 24.8 | 11.5 | 8.4 |

| Emergency admission (%) | 63.3 | 75.6 | 72.9 |

| Weekend admission (%) | 24.5 | 26.2 | 25.1 |

| Hospital bed size (%) | |||

| Small | 8.9 | 10.3 | 11.4 |

| Medium | 24.0 | 22.3 | 25.9 |

| Large | 67.1 | 67.5 | 62.8 |

| Hospital control (%) | |||

| Private | 33.8 | 34.8 | 34.4 |

| Government (nonfederal) | 6.7 | 9.7 | 8.3 |

| Private or government | 59.5 | 55.5 | 57.3 |

| Hospital region (%) | |||

| Northeast | 17.4 | 12.5 | 17.6 |

| Midwest | 25.7 | 19.4 | 20.9 |

| South | 39.5 | 56.8 | 42.4 |

| West | 17.4 | 11.3 | 19.2 |

| Teaching hospital (%) | 41.7 | 43.8 | 43.3 |

Compared with privately insured patients, a larger proportion of uninsured and Medicaid patients had higher predicted mortality levels (Table 2). Medicaid patients had a disproportionately higher predicted LOS, whereas predicted resource demand was higher among privately insured patients. Hypertension (48%), chronic pulmonary disease (29.5%), and uncomplicated diabetes (21.5%) were the 3 most common comorbidities in the study cohort, with a generally higher prevalence of comorbidities among Medicaid patients.

| Characteristic* | Privately insured (n = 73,256) | Uninsured (n = 18,531) | Medicaid (n = 26,222) |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Medstat disease staging (%) | |||

| Mortality level 1 | 50.8 | 45.4 | 36.7 |

| Mortality level 2 | 44.0 | 49.1 | 56.7 |

| Mortality level 3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 6.7 |

| Length of stay level 1 | 66.8 | 71.6 | 53.8 |

| Length of stay level 2 | 28.5 | 24.5 | 39.3 |

| Length of stay level 3 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 6.9 |

| Resource demand level 1 | 45.2 | 54.2 | 48.5 |

| Resource demand level 2 | 40.5 | 34.2 | 39.2 |

| Resource demand level 3 | 14.2 | 11.7 | 12.3 |

| Coexisting medical conditions (%) | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 4.7 | 4.8 | 10.1 |

| Valvular disease | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.7 |

| Pulmonary circulation disease | 0.8 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| Paralysis | 1.2 | 0.8 | 3.5 |

| Other neurological disorders | 2.4 | 1.9 | 7.3 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 23.6 | 22.4 | 37.7 |

| Uncomplicated diabetes | 19.6 | 18.6 | 23.4 |

| Complicated diabetes | 3.3 | 2.1 | 4.9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 5.6 | 2.7 | 4.7 |

| Renal failure | 3.0 | 1.9 | 5.6 |

| Liver disease | 1.6 | 2.5 | 4.4 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | <0.5 | <0.5 | <0.5 |

| AIDS | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Lymphoma | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.6 |

| Metastatic cancer | 2.1 | 0.7 | 2.2 |

| Non‐metastatic solid tumor | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.1 |

| Collagen vascular diseases | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 |

| Coagulopathy | 2.7 | 2.4 | 3.4 |

| Obesity | 10.3 | 8.2 | 9.3 |

| Weight loss | 1.6 | 1.8 | 3.3 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 18.3 | 19.4 | 23.8 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Deficiency anemias | 8.6 | 8.5 | 13.4 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3.3 | 9.8 | 8.3 |

| Drug abuse | 1.9 | 10.2 | 9.8 |

| Psychoses | 1.5 | 1.9 | 6.8 |

| Depression | 7.2 | 4.8 | 9.9 |

| Hypertension | 48.0 | 44.1 | 45.7 |

In‐Hospital Mortality

Compared with the privately insured, age‐standardized and sex‐standardized in‐hospital mortality for AMI and stroke was significantly higher for uninsured and Medicaid patients (Table 3). Among pneumonia patients, Medicaid recipients had significantly higher in‐hospital mortality compared with privately insured and uninsured patients.

| Privately Insured | Uninsured | Medicaid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital mortality, rate per 100 discharges (SE) | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.22 (0.10) | 4.03 (0.31)* | 4.57 (0.34)* |

| Stroke | 7.49 (0.27) | 10.46 (0.64)* | 9.89 (0.45)* |

| Pneumonia | 1.75 (0.09) | 1.74 (0.18) | 2.48 (0.14)* |

| Length of stay, mean (SE), days | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 4.17 (0.06) | 4.46 (0.09) | 5.85 (0.16) |

| Stroke | 6.37 (0.13) | 7.15 (0.25) | 9.28 (0.30) |

| Pneumonia | 4.89 (0.05) | 4.64 (0.10) | 5.80 (0.08) |

| Cost per episode, mean (SE), dollars | |||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 21,077 (512) | 19,977 (833) | 22,452 (841) |

| Stroke | 16,022 (679) | 14,571 (1,036) | 18,462 (824) |

| Pneumonia | 8,223 (192) | 7,086 (293) | 9,479 (271) |

After multivariable adjustment for additional patient and hospital characteristics, uninsured AMI and stroke patients continued to have significantly higher in‐hospital mortality compared with the privately insured (Table 4). Among pneumonia patients, Medicaid recipients persisted in having significantly higher in‐hospital mortality than the privately insured.

| Model 1* | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital mortality, adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 1.59 (1.35‐1.88) | 1.58 (1.30‐1.93) | 1.52 (1.24‐1.85) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.83 (1.54‐2.18) | 1.22 (0.99‐1.50) | 1.15 (0.94‐1.42) |

| Stroke | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 1.56 (1.35‐1.80) | 1.50 (1.30‐1.73) | 1.49 (1.29‐1.72) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.32 (1.15‐1.52) | 1.09 (0.93‐1.27) | 1.08 (0.93‐1.26) |

| Pneumonia | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 0.99 (0.81‐1.21) | 1.12 (0.91‐1.39) | 1.10 (0.89‐1.36) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.41 (1.20‐1.65) | 1.24 (1.04‐1.48) | 1.21 (1.01‐1.45) |

| Length of stay, adjusted ratio (95% CI)| | |||

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 1.00 (0.98‐1.02) | 1.00 (0.98‐1.02) | 1.00 (0.98‐1.02) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.17 (1.14‐1.21) | 1.07 (1.05‐1.09) | 1.07 (1.05‐1.09) |

| Stroke | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 1.06 (1.02‐1.10) | 1.08 (1.04‐1.11) | 1.07 (1.04‐1.11) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.30 (1.26‐1.34) | 1.17 (1.14‐1.20) | 1.17 (1.14‐1.20) |

| Pneumonia | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 0.95 (0.93‐0.97) | 0.96 (0.94‐0.99) | 0.96 (0.94‐0.98) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.15 (1.13‐1.17) | 1.04 (1.03‐1.06) | 1.04 (1.03‐1.06) |

| Cost per episode, adjusted ratio (95% CI)| | |||

| Acute Myocardial Infarction | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 0.97 (0.95‐0.99) | 0.99 (0.97‐1.00) | 0.99 (0.97‐1.00) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.01 (0.98‐1.04) | 0.99 (0.97‐1.01) | 0.99 (0.97‐1.01) |

| Stroke | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 0.97 (0.93‐1.02) | 1.00 (0.96‐1.03) | 1.00 (0.97‐1.03) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.17 (1.13‐1.21) | 1.06 (1.04‐1.09) | 1.06 (1.04‐1.09) |

| Pneumonia | |||

| Uninsured vs. privately insured | 0.95 (0.92‐0.97) | 0.98 (0.96‐1.00) | 0.98 (0.96‐1.00) |

| Medicaid vs. privately insured | 1.17 (1.15‐1.19) | 1.05 (1.04‐1.07) | 1.05 (1.04‐1.07) |

LOS

Among AMI and stroke patients, age‐standardized and sex‐standardized mean LOS was significantly longer for the uninsured and Medicaid recipients compared with the privately insured (Table 3). Among pneumonia patients, the uninsured had a slightly shorter mean LOS compared with the privately insured whereas Medicaid recipients averaged the longest LOS.

These insurance‐related disparities in LOS among pneumonia patients persisted after multivariable adjustment (Table 4). Among AMI patients, only Medicaid recipients persisted in having a significantly longer LOS than the privately insured. Among stroke patients, both the uninsured and Medicaid recipients averaged a longer LOS compared with the privately insured.

Cost per Episode

For all 3 conditions, the uninsured had significantly lower age‐standardized and sex‐standardized costs compared with the privately insured (Table 3). However, Medicaid patients had higher costs than the privately insured for all three conditions, significantly so among patients with stroke and pneumonia.

These insurance‐related disparities in costs persisted in multivariable analyses (Table 4). The uninsured continued to have lower costs compared with the privately insured, significantly so for patients with AMI and pneumonia. Among stroke and pneumonia patients, Medicaid recipients continued to accrue higher costs than the uninsured or privately insured.

Discussion

In this nationally representative study of working‐age Americans hospitalized for 3 common medical conditions, we found that insurance status was associated with significant variations in in‐hospital mortality and resource use. Whereas privately insured patients experienced comparatively lower in‐hospital mortality in most cases, mortality risk was highest among the uninsured for 2 of the 3 common causes of noncancer inpatient deaths. Although previous studies have examined insurance‐related disparities in inpatient care for individual diagnoses and specific populations, no broad overview of this important issue has been published in the past decade. In light of the current economic recession and national healthcare debate, these findings may be a prescient indication of a widening insurance gap in the quality of hospital care.

There are several potential mechanisms for these disparities. For instance, Hadley et al.9 reported significant underuse of high‐cost or high‐discretion procedures among the uninsured in their analysis of a nationally representative sample of 592,598 hospitalized patients. Similarly, Burstin et al.10 found that among a population of 30,195 hospitalized patients with diverse diagnoses, the uninsured were at greater risk for receiving substandard care regardless of hospital characteristics. These, and other similar findings,7, 8, 19 are suggestive of differences in the way uninsured patients are generally managed in the hospital that may partly explain the disparities reported herein.

More specifically, analyses of national registries of AMI have documented lower rates of utilization of invasive, potentially life‐saving, cardiac interventions among the uninsured.16, 17 Similarly, a lower rate of carotid endarterectomy was reported among uninsured stroke patients from an analysis of the 2002 NIS.15 Other differences in inpatient management unmeasured by administrative data, such as the use of subspecialists and allied health professionals, may also contribute.32 Unfortunately, limitations in the available data prevented us from being able to appropriately address the important issue of insurance related differences in the utilization of specific inpatient procedures.

These disparities may also be indicative of differences in severity of illness that are not captured fully by the MedStat disease staging criteria. The uninsured might have more severe illness at admission, either due to the presence of more advanced chronic disease or delay in seeking care for the acute episode. AMI and stroke are usually the culmination of longstanding atherosclerosis that is amenable to improvement through timely and consistent risk‐factor modification. Not having a usual source of medical care,6, 33 inadequate screening and management of known risk‐factors,3, 34 and difficulties in obtaining specialty care5 among the uninsured likely increases their risk of being hospitalized with more advanced disease. The higher likelihood of being admitted through the emergency department19 and on weekends9 among the uninsured lends credence to the possibility of delays in seeking care. All of these are potential mediators of higher AMI and stroke mortality in uninsured patients.

Finally, these mortality differences could also be due to the additional risks imposed by poorly managed comorbidities among uninsured patients. Although we controlled for the presence of comorbidities in our analysis, we lacked data about the severity of individual comorbidities. A recent study reported significant lapses in follow‐up care after the onset of a chronic condition in uninsured individuals under 65 years of age.34 Other studies have also documented insurance related disparities in the care of chronic diseases3, 35 that were among the most common comorbidities in our cohort.

Most of the reasons for insurance‐related disparities noted above for the uninsured are also applicable to Medicaid patients. Differences in the intensity of inpatient care,7, 8, 1519 limited access to health care services,2, 14 unmet health needs,5 and suboptimal management of chronic medical conditions35 were also reported for Medicaid patients in prior research. These factors likely contributed to the higher in‐hospital mortality in this patient population, evidenced by the sequential decrease in odds after adjusting for comorbidities and disease severity. Medicaid patients hospitalized for stroke were noted to have significantly longer LOS, which could plausibly be due to difficulties with arranging appropriate discharge disposition; the higher likelihood of paralysis among these patients15 would likely necessitate a higher frequency of rehabilitation facility placement. The higher costs for Medicaid patients with stroke and pneumonia may potentially be the result of these patients longer LOS. Although cost differences between the uninsured and privately insured were statistically significant, these were not large enough to be of material significance.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Since the NIS does not assign unique patient identifiers that would permit tracking of readmissions, we excluded patients transferred to another acute‐care hospital from our study to avoid counting the same patient twice. However, only 10% of hospitalized patients underwent transfer for cardiac procedures in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction, with privately insured patients more likely to be transferred than other insurance groups.17 Since these patients are also more likely to have better survival, their exclusion likely biased our study toward the null. The same is probable for stroke patients as well.

Some uninsured patients begin Medicaid coverage during hospitalization and should ideally be counted as uninsured but were included under Medicaid in our analysis. They are also likely to be state‐ and plan‐specific variations in Medicaid and private payer coverage that we could not incorporate into our analysis. In addition, we were unable to include deaths that may have occurred shortly after discharge, even though these may have been related to the quality of hospital care. Furthermore, although the 3 conditions we studied are common and responsible for a large number of hospital deaths, they make up about 8% of total annual hospital discharges,23 and caution should be exercised in generalizing our findings to the full spectrum of hospitalizations. Lastly, it is possible that unmeasured confounding could be responsible for the observed associations. Uninsured and Medicaid patients are likely to have more severe disease, which may not be adequately captured by the administrative data available in the NIS. If so, this would explain the mortality association rather than insurance status.36, 37

Conclusions

Significant insurance‐related differences in mortality exist for 2 of the leading causes of noncancer inpatient deaths among working‐age Americans. Further studies are needed to determine whether provider sensitivity to insurance status or unmeasured sociodemographic and clinical prognostic factors are responsible for these disparities. Policy makers, hospital administrators, and physicians should be cognizant of these disparities and consider policies to address potential insurance related gaps in the quality of inpatient care.

- , .The U.S. economy and changes in health insurance coverage, 2000‐2006.Health Aff (Millwood).2008;27(2):w135‐w144.

- , , .Rates of avoidable hospitalization by insurance status in Massachusetts and Maryland.JAMA.1992;268(17):2388‐2394.

- , , , et al.Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States.JAMA.2000;284(16):2061‐2069.

- , , .Health insurance and access to care for symptomatic conditions.Arch Intern Med.2000;160(9):1269‐1274.

- , , , et al.Access to specialty care and medical services in community health centers.Health Aff (Millwood).2007;26(5):1459‐1468.

- , , , et al.A national study of chronic disease prevalence and access to care in uninsured U.S. adults.Ann Intern Med.2008;149:170–176.

- , , , .Relationship between patient source of payment and the intensity of hospital services.Med Care.1988;26(11):1111‐1114.

- , , .The association of payer with utilization of cardiac procedures in Massachusetts.JAMA.1990;264(10):1255‐1260.

- , , .Comparison of uninsured and privately insured hospital patients: condition on admission, resource use, and outcome.JAMA.1991;265:374–379.

- , , .Socioeconomic status and risk for substandard medical care.JAMA.1992;268(17):2383‐2387.

- , , , .The relation between health insurance coverage and clinical outcomes among women with breast cancer.N Engl J Med.1993;329(5):326‐331.

- , , .Health insurance and mortality. Evidence from a national cohort.JAMA.1993;270(6):737‐741.

- , , , .Mortality in the uninsured compared with that in persons with public and private health insurance.Arch Intern Med.1994;154(21):2409‐2416.

- .Medicaid policy and the substitution of hospital outpatient care for physician care.Health Serv Res.1989;24:33–66.

- , .Disparities in outcomes among patients with stroke associated with insurance status.Stroke.2007;38(3):1010‐1016.

- , , , et al.Influence of payor on use of invasive cardiac procedures and patient outcome after myocardial infarction in the United States. Participants in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction.J Am Coll Cardiol.1998;31(7):1474‐1480.

- , , , et al.Payer status and the utilization of hospital resources in acute myocardial infarction: a report from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2.Arch Intern Med.2000;160(6):817–823.

- , , , et al.Insurance coverage and care of patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes.Ann Intern Med.2006;145(10):739–748.

- , , .Comparing uninsured and privately insured hospital patients: Admission severity, health outcomes and resource use.Health Serv Manage Res.2001;14(3):203–210.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2005. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007:6. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/NIS_Introduction_2005.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Design of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2005. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/reports/NIS_2005_Design_Report.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators. Inpatient Quality Indicators: Technical Specifications. Version 3.1 (March 12, 2007). Available at: www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/downloads/iqi/iqi_technical_specs_v31.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- , , . National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2005 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Vital and Health Statistics 13(165). Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_13/sr13_165.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- AHRQ Quality Indicators. Guide to Inpatient Quality Indicators: Quality of Care in Hospitals—Volume, Mortality, and Utilization. Version 3.1 (March 12, 2007). Available at: www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/downloads/iqi/iqi_guide_v31.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- , , .Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2006.Washington, DC:US Census Bureau. Current Population Reports;2007:60–233.

- , . Conditions Related to Uninsured Hospitalizations, 2003. HCUP Statistical Brief #8. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006:6. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb8.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. NIS Description of Data Elements. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp. Accessed February2010.

- , , , .Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data.Med Care.1998;36:8–27.

- SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 9.0. Research TrianglePark, NC:Research Triangle Institute;2006.

- , . Final Report on Calculating Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Variances, 2001. HCUP Methods Series Report #2003‐2. Online June 2005 (revised June 6, 2005). U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/CalculatingNISVariances200106092005.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- .On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys.Int Stat Rev.1983;51:279–292.

- , , , et al.Patient characteristics associated with care by a cardiologist among adults hospitalized with severe congestive heart failure.J Am Coll Cardiol.2000;36:2119–2125.

- , . Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007:12. Vital and Health Statistics 10(235). Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_235.pdf. Accessed February2010.

- .Insurance coverage, medical care use, and short‐term health changes following an unintentional injury or the onset of a chronic condition.JAMA.2007;297(10):1073–1084.

- , , , et al.The quality of chronic disease care in U.S. community health centers.Health Aff (Millwood).2006;25(6):1712–1723.

- , , , , , .Risk‐adjusting hospital inpatient mortality using automated inpatient, outpatient, and laboratory databases.Med Care.2008;46(3):232–239.

- , , , .The Kaiser Permanente inpatient risk adjustment methodology was valid in an external patient population.J Clin Epidemiol. [E‐pub ahead of print].

With about 1 in 5 working‐age Americans (age 18‐64 years) currently uninsured and a large number relying on Medicaid, adequate access to quality health care services is becoming increasingly difficult.1 Substantial literature has accumulated over the years suggesting that access and quality in health care are closely linked to an individual's health insurance status.211 Some studies indicate that being uninsured or publicly insured is associated with negative health consequences.12, 13 Although the Medicaid program has improved access for qualifying low‐income individuals, significant gaps in access and quality remain.2, 5, 11, 1419 These issues are likely to become more pervasive should there be further modifications to state Medicaid funding in response to the unfolding economic crisis.