User login

CDC update: Guidelines for treating STDs

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

In 2010, the CDC released an update of its Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Treatment Guidelines,1 which were last updated in 2006. The guidelines are widely viewed as the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of STDs, and they are the standard for publicly and privately funded clinics focusing on sexual health.

What’s new

Some of the notable changes made since the last update in 2006 appear in TABLE 1.1,2

Uncomplicated gonorrhea. Cephalosporins are the only class of antibiotic recommended as first-line treatment for gonorrhea. (In a 2007 recommendation revision, the CDC opted to no longer recommend quinolone antibiotics for the treatment of gonorrhea, because of widespread bacterial resistance.3) Preference is now given to ceftriaxone because of its proven effectiveness against pharyngeal infection, which is often asymptomatic, difficult to detect, and difficult to eradicate. Additionally, the 2010 update has increased the recommended dose of ceftriazone from 125 to 250 mg intramuscularly. The larger dose is more effective against pharyngeal infection; it is also a safeguard against decreased bacterial susceptibility to cephalosporins, which, although still very low, has been reported in more cases recently.

The guidelines still recommend that azithromycin, 1 g orally in a single dose, be given with ceftriaxone because of the relatively high rate of co-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis and the potential for azithromycin to assist with eradicating any gonorrhea with decreased susceptibility to ceftriaxone.

Pelvic inflammatory disease. Quinolones have also been removed from the list of options for outpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. All recommended regimens now specify a parenteral cephalosporin as a single injection with doxycycline 100 mg PO twice a day for 14 days, with or without metronidazole 500 mg PO twice a day for 14 days.

Bacterial vaginosis. Tinidazole, 2 g orally once a day for 2 days or 1 g orally once a day for 5 days, is now an alternative agent for bacterial vaginosis. However, preferred treatments remain metronidazole 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, metronidazole gel intravaginally once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days.

Newborn gonococcal eye infection. A relatively minor change is the elimination of tetracycline as prophylaxis for newborn gonococcal eye infections, leaving only erythromycin ointment to prevent the condition.

TABLE 1

2010 vs 2006: How have the CDC recommendations for STD treatment changed?1,2

Uncomplicated gonococcal infections of the cervix, urethra, rectum, and pharynx

|

| Pelvic inflammatory disease Parenteral regimens

|

Bacterial vaginosis

|

Prophylaxis for gonococcal eye infection in a newborn

|

Single-dose therapy preferred among equivalent options

Single-dose therapy (TABLE 2), while often more expensive than other options, increases compliance and helps ensure treatment completion. Single-dose therapy administered in your office is essentially directly observed treatment, an intervention that has become the standard of care for other diseases such as tuberculosis. If the single-dose agent is as effective as alternative medications, directly observed on-site administration is the preferred option for treating STDs.

TABLE 2

Single-dose therapies for specific STDs1

| Infection or condition | Single-dose therapy |

|---|---|

| Candida | Miconazole 1200 mg vaginal suppository or Tioconazole 6.5% ointment 5 g intravaginally or Butoconazole 2% cream 5 g intravaginally or Fluconazole 150 mg PO |

| Cervicitis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Chancroid | Azithromycin 1 g PO or Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Chlamydia urogenital infection | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: conjunctivitis | Ceftriaxone 1 g IM |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the cervix, urethra, rectum | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (preferred) or Cefixime 400 mg PO or Single-dose injectable cephalosporin plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Gonorrhea: uncomplicated infection of the pharynx | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Nongonococcal urethritis | Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Post-sexual assault prophylaxis | Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM or Cefixime 400 mg PO plus Metronidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO |

| Recurrent, persistent nongonococcal urethritis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO plus Azithromycin 1 g PO (if not used for initial episode) |

| Syphilis: primary, secondary, and early latent | Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM |

| Trichomoniasis | Metronidazole 2 g PO or Tinidazole 2 g PO |

Other guideline recommendations

The CDC’s STD treatment guidelines contain a wealth of useful information beyond treatment advice: recommended methods of confirming diagnoses, analyses of the usefulness of various diagnostic tests, recommendations on how to manage sex partners of those infected, guidance on STD prevention counseling, and considerations for special populations and circumstances.

Additionally, there is a section on screening for STDs reflecting recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); it also includes recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. In at least one instance, though, the USPSTF recommendation on screening for HIV infection contradicts other CDC sources.4,5 Also included is guidance on using vaccines to prevent hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and human papillomavirus (HPV), which follows the recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. When to use DNA testing to detect HPV is described briefly.

A shortcoming of the CDC guidelines

Although the CDC’s STD guidelines remain the most authoritative source of information on the diagnosis and treatment of STDs, they do not seem to use a consistent method for assessing and describing the strength of the evidence behind the recommendations, which family physicians have come to expect. (However, it is sometimes possible to discern the type and strength of evidence for a particular recommendation from the written discussion.)

The new guidelines state that a series of papers to be published in Clinical Infectious Diseases will describe more fully the evidence behind some of the recommendations and include evidence tables. However, in future guideline updates, it would be helpful if the CDC were to include a brief description of the quantity and strength of evidence alongside each recommended treatment option in the tables.

How best to keep up to date

Although the new guidelines summarize the current status of recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of STDs and are a useful resource for family physicians, we cannot stay current simply by referring to them alone over the next 4 to 5 years until a new edition is published. As new evidence develops, changes in recommendations will be published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Case in point: new interim HIV recommendations. Interim recommendations were recently released on pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men.6 (For more on these recommendations, check out this month’s audiocast at jfponline.com.) Final recommendations are expected later this year. Recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection are also expected soon.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

1. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

3. Campos-Outcalt D. Practice alert: CDC no longer recommends quinolones for treatment of gonorrhea. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:554-558.

4. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1-17.

5. Campos-Outcalt D. Time to revise your HIV testing routine. J Fam Pract. 2007;56:283-284.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance: preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:65-68.

Urine drug testing: An unproven risk management tool?

As a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, an author of numerous scholarly articles about chronic pain (some of which are cited here), and a person who lives with chronic pain, I would like to comment on “Is it time to drug test your chronic pain patient?” (J Fam Pract. 2010;59:628-633). Drs. McBane and Weigle recommend the use of pain agreements and drug testing for every patient with noncancer chronic pain, but fail to mention that there is insufficient evidence of the efficacy of both adherence monitoring tools.1 In addition, a recent article in The American Journal of Bioethics recommends against the “universal application of pain agreements” and suggests that they can harm the patient/physician relationship.2 Consent for drug testing often comes from the pain contract3—agreements that have been called “unconscionable adhesion contracts” and may be unenforceable.4

The authors also suggest that urine drug testing is noninvasive. Nothing could be further from the truth. Drug testing of people with pain may be considered a suspicionless and warrantless search of bodily fluids and in certain cases may be unconstitutional.5 There is no question that drug misuse, abuse, addiction, and overdose are devastating to individuals, families, and society. However, using unproven risk management tools that may cause greater harm than good is just bad medicine.

Mark Collen

Sacramento, Calif

1. Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712-720.

2. Payne R, Anderson E, Arnold R, et al. A rose by any other name: pain contracts/agreements. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:5-12.

3. Collen M. Analysis of controlled substance agreements from private practice physicians. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23:357-364.

4. Collen M. Opioid contracts and random drug testing for people with chronic pain—think twice. J Law Med Ethics. 2009;37:841-845.

5. Collen M. The Fourth Amendment and random drug testing of people with chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25:in press.

As a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, an author of numerous scholarly articles about chronic pain (some of which are cited here), and a person who lives with chronic pain, I would like to comment on “Is it time to drug test your chronic pain patient?” (J Fam Pract. 2010;59:628-633). Drs. McBane and Weigle recommend the use of pain agreements and drug testing for every patient with noncancer chronic pain, but fail to mention that there is insufficient evidence of the efficacy of both adherence monitoring tools.1 In addition, a recent article in The American Journal of Bioethics recommends against the “universal application of pain agreements” and suggests that they can harm the patient/physician relationship.2 Consent for drug testing often comes from the pain contract3—agreements that have been called “unconscionable adhesion contracts” and may be unenforceable.4

The authors also suggest that urine drug testing is noninvasive. Nothing could be further from the truth. Drug testing of people with pain may be considered a suspicionless and warrantless search of bodily fluids and in certain cases may be unconstitutional.5 There is no question that drug misuse, abuse, addiction, and overdose are devastating to individuals, families, and society. However, using unproven risk management tools that may cause greater harm than good is just bad medicine.

Mark Collen

Sacramento, Calif

As a member of the editorial board of the Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy, an author of numerous scholarly articles about chronic pain (some of which are cited here), and a person who lives with chronic pain, I would like to comment on “Is it time to drug test your chronic pain patient?” (J Fam Pract. 2010;59:628-633). Drs. McBane and Weigle recommend the use of pain agreements and drug testing for every patient with noncancer chronic pain, but fail to mention that there is insufficient evidence of the efficacy of both adherence monitoring tools.1 In addition, a recent article in The American Journal of Bioethics recommends against the “universal application of pain agreements” and suggests that they can harm the patient/physician relationship.2 Consent for drug testing often comes from the pain contract3—agreements that have been called “unconscionable adhesion contracts” and may be unenforceable.4

The authors also suggest that urine drug testing is noninvasive. Nothing could be further from the truth. Drug testing of people with pain may be considered a suspicionless and warrantless search of bodily fluids and in certain cases may be unconstitutional.5 There is no question that drug misuse, abuse, addiction, and overdose are devastating to individuals, families, and society. However, using unproven risk management tools that may cause greater harm than good is just bad medicine.

Mark Collen

Sacramento, Calif

1. Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712-720.

2. Payne R, Anderson E, Arnold R, et al. A rose by any other name: pain contracts/agreements. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:5-12.

3. Collen M. Analysis of controlled substance agreements from private practice physicians. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23:357-364.

4. Collen M. Opioid contracts and random drug testing for people with chronic pain—think twice. J Law Med Ethics. 2009;37:841-845.

5. Collen M. The Fourth Amendment and random drug testing of people with chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25:in press.

1. Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712-720.

2. Payne R, Anderson E, Arnold R, et al. A rose by any other name: pain contracts/agreements. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:5-12.

3. Collen M. Analysis of controlled substance agreements from private practice physicians. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2009;23:357-364.

4. Collen M. Opioid contracts and random drug testing for people with chronic pain—think twice. J Law Med Ethics. 2009;37:841-845.

5. Collen M. The Fourth Amendment and random drug testing of people with chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25:in press.

Diffuse abdominal pain, vomiting

• Use the APACHE-II scoring system early on to help predict the severity of pancreatitis.

• Consider early enteral nutrition in patients with severe disease; taking this step has been linked to lower infection rates and shorter lengths of stay.

• Consider patient factors and the risk of severe infection when deciding whether or not to use prophylactic antibiotics in cases of severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

CASE A 57-year-old Caucasian woman sought care at our emergency department (ED) for diffuse abdominal pain and nausea. She said that the pain began after eating lunch earlier that day, and localized periumbilically, with radiation to the back. She had several episodes of nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting, but denied fever, chills, or diarrhea.

Her past medical history was notable only for an episode of gallstone pancreatitis 11 years earlier, after which she underwent a cholecystectomy. Her only medications were ibandronate sodium (Boniva) taken for osteoporosis (diagnosed 2 years earlier), a multivitamin, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin E supplements. Her family history was notable for a brother who had pancreatic cancer in his 50s. The patient reported infrequent alcohol use.

The abdominal exam was notable for diffuse tenderness to palpation, most prominent in the epigastric region. The patient exhibited voluntary guarding, without rebound, and positive bowel sounds throughout.

The patient’s laboratory studies on admission included leukocytosis of 21,300 cells/mcL and hemoglobin and hematocrit of 17.3 g/dL and 52.1%, respectively. She had an amylase of 1733 U/L and lipase of 4288 U/L. Lactate and lactic dehydrogenase were 1.83 mg/dL and 265 U/L, respectively. Liver function tests and a basic metabolic panel were within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for an enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic edema and free fluid in the abdomen.

The patient underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation throughout the first 6 hours of her hospital stay. Urine output was noted to be incongruent with fluid intake, at just over 60 cc/h. Over the next 4 hours, she became progressively tachycardic, tachypneic, and somnolent, with increasing abdominal tenderness. Her serum potassium level rose to 4.9 mEq/L, while serum bicarbonate declined to 13 mEq/L and serum calcium, to 6.2 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas revealed metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.22.

Our patient was subsequently transferred to the medical intensive care unit, where she required endotracheal intubation.

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HER CONDITION?

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis

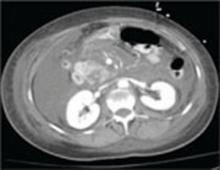

A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast taken on the second day of admission revealed extensive pancreatitis with complete disintegration of the pancreatic tissue and absence of pancreatic enhancement (FIGURE), as well as a large amount of abdominal ascites.

Pancreatitis is a common inpatient diagnosis, with approximately 200,000 hospitalizations yearly.1 Most cases are mild and self-limiting, requiring minimal intervention including parenteral fluid resuscitation, pain control, and restriction of oral intake. Most cases can be attributed to gallstones or excessive alcohol use, but approximately 25% of cases are idiopathic.1 Other causes include hypertriglyceridemia, infection, hypercalcemia, and medications such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, trimethoprim sulfa-methoxazole, and furosemide. Severe necrotizing pancreatitis represents about 20% of all cases, but carries a mortality rate of between 10% and 30%.1

Diagnosis is based on clinical features in conjunction with biochemical markers. Amylase is nonspecific, but levels 3 times the upper limit of normal are usually diagnostic of acute pancreatitis. Lipase is 85% to 100% sensitive for pancreatitis, and is more specific than amylase. Alanine aminotransferase >150 IU/L is 96% specific for gallstone pancreatitis.2 Of note: there is no evidence to support daily monitoring of these enzyme levels as predictors of clinical improvement or disease severity.

FIGURE

CT scan of abdomen taken on second day of admission

Predicting severity at time of presentation can be difficult

As was true with our patient, predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis at the time of presentation can be difficult. Scoring systems that are commonly used to evaluate disease severity include Ranson’s score, APACHE-II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II), and CT severity index, among others (TABLE). Of these, the APACHE-II score has been found to be most predictive of progression to severe disease, with accuracy of up to 75%.3

Recent studies have shown that a body mass index >30 kg/m2 is an independent risk factor for progression to severe pancreatitis.4 Other clinical predictors include poor urine output, rising hematocrit, agitation or confusion, and lack of improvement in symptoms within 48 hours.1

Though our patient came in with symptoms that were initially mild, she quickly manifested several clinical predictors for severe pancreatitis, including poor urine output and increasing confusion, as well as an APACHE-II score of 12 at 6 hours after presentation (values ≥8 indicate high risk for progression to severe disease).

TABLE

Predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis1

| Ranson score ≥3 |

| APACHE-II score ≥8 |

| CT severity index (CT grade + necrosis score) >6 |

| Body mass index >30 kg/m2 |

| Hematocrit >44% (clearly increases risk for pancreatic necrosis) |

Clinical findings:

|

| Lack of improvement in symptoms within the first 48 hours |

| APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CT, computed tomography. |

Role of antibiotics? A source of debate

Infection represents the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with pancreatic necrosis. Approximately 40% of patients with necrosis develop infection, with a 20% mortality rate.5 Signs of infection usually develop relatively late in the clinical course and rates increase drastically each week a patient remains hospitalized (71% of patients have signs of infection at 3 weeks).5

Interestingly, the role for antibiotics in such patients has been a source of debate in practice, as well as in the medical literature. Two recent large meta-analyses came to different conclusions regarding the use of antibiotics. A 2006 study by Heinrich et al concluded that patients with pancreatic necrosis demonstrated by contrast-enhanced CT scans should receive antibiotic prophylaxis with imipenem or meropenem for 14 days, and that prophylactic antibiotics do not increase rates of subsequent fungal infection.6 Conversely, as noted in a 2008 study published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, “prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis.”7

Two leading professional groups have similarly contradictory recommendations on the topic, with the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) supporting antibiotic use for patients with >30% pancreatic necrosis noted on CT and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommending against the use of prophylactic antibiotics.8

As with any clinical dilemma, it seems prudent to make the decision for or against prophylactic antibiotics based on available clinical information and the particular patient’s risk factors. Clearly, in the most high-risk patients, it would be difficult to justify withholding antibiotic therapy.

Complete bowel rest—or not?

In the past, it was thought necessary to allow for complete bowel rest and suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion during acute pancreatitis by providing total parenteral nutrition.6,9 More recently, though, the use of early nasojejunal enteral feeding (which was initiated for our patient) has been advocated by several large meta-analyses,6 as well as by the AGA and ACG.2

The use of enteral feeding has been associated with improved outcomes, including lower infection rates (due to maintenance of the intestinal barrier and prevention of bacterial translocation), decreased length of stay, reduced rates of organ failure, and fewer deaths among patients who require surgical intervention.6

A lengthy road to recovery for our patient

After 7 days of mechanical ventilation, our patient was extubated. However, she developed significant bilateral pleural effusions as a result of fluid third spacing, and required thoracentesis.

She completed a 14-day course of imipenem, followed by an additional 10-day course due to hypotension and a suspected infected pseudocyst. Subsequent imaging studies confirmed our suspicions: She had developed a large pseudocyst (>13 cm), which remained under observation by both a gastroenterologist and general surgeon. Six weeks after admission, our patient was discharged to home with family.

But what was the cause? Although we were unable to clearly delineate an inciting cause for her pancreatitis during the admission, she was to undergo further investigation as an outpatient. There were also plans to drain the pseudocyst 6 weeks after discharge.

A learning opportunity. This patient’s case provided an excellent opportunity for our team to review the important clinical predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis, and the rapid nature of clinical decline in such patients. In hindsight, the predictors of severity in our patient were few, but included the rapid onset and clinical progression of her symptoms, as well as her elevated hematocrit on presentation and poor urine output over the first 6 hours of admission.

1. Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150.

2. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS. ed. UpTo-Date [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpTo-Date; 2010.

3. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

4. Skipworth JRA, Pereira SP. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:172-178.

5. Windsor JA, Schweder P. Complications of acute pancreatitis (including pseudocysts). In: Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, eds. Main-got’s Abdominal Operations. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007:chap 37. Available at: http://www.accesssurgery.com/content.aspx?filename="6003JFP_HospitalRounds" aid=130125. Accessed November 30, 2010.

6. Heinrich S, Shafer M, Rousson V, et al. Evidenced-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154-168.

7. Bai Y, Gao J, Zou DW, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:104-110.

8. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Treatment of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

9. Haney JC, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1431-1446.

• Use the APACHE-II scoring system early on to help predict the severity of pancreatitis.

• Consider early enteral nutrition in patients with severe disease; taking this step has been linked to lower infection rates and shorter lengths of stay.

• Consider patient factors and the risk of severe infection when deciding whether or not to use prophylactic antibiotics in cases of severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

CASE A 57-year-old Caucasian woman sought care at our emergency department (ED) for diffuse abdominal pain and nausea. She said that the pain began after eating lunch earlier that day, and localized periumbilically, with radiation to the back. She had several episodes of nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting, but denied fever, chills, or diarrhea.

Her past medical history was notable only for an episode of gallstone pancreatitis 11 years earlier, after which she underwent a cholecystectomy. Her only medications were ibandronate sodium (Boniva) taken for osteoporosis (diagnosed 2 years earlier), a multivitamin, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin E supplements. Her family history was notable for a brother who had pancreatic cancer in his 50s. The patient reported infrequent alcohol use.

The abdominal exam was notable for diffuse tenderness to palpation, most prominent in the epigastric region. The patient exhibited voluntary guarding, without rebound, and positive bowel sounds throughout.

The patient’s laboratory studies on admission included leukocytosis of 21,300 cells/mcL and hemoglobin and hematocrit of 17.3 g/dL and 52.1%, respectively. She had an amylase of 1733 U/L and lipase of 4288 U/L. Lactate and lactic dehydrogenase were 1.83 mg/dL and 265 U/L, respectively. Liver function tests and a basic metabolic panel were within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for an enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic edema and free fluid in the abdomen.

The patient underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation throughout the first 6 hours of her hospital stay. Urine output was noted to be incongruent with fluid intake, at just over 60 cc/h. Over the next 4 hours, she became progressively tachycardic, tachypneic, and somnolent, with increasing abdominal tenderness. Her serum potassium level rose to 4.9 mEq/L, while serum bicarbonate declined to 13 mEq/L and serum calcium, to 6.2 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas revealed metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.22.

Our patient was subsequently transferred to the medical intensive care unit, where she required endotracheal intubation.

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HER CONDITION?

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis

A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast taken on the second day of admission revealed extensive pancreatitis with complete disintegration of the pancreatic tissue and absence of pancreatic enhancement (FIGURE), as well as a large amount of abdominal ascites.

Pancreatitis is a common inpatient diagnosis, with approximately 200,000 hospitalizations yearly.1 Most cases are mild and self-limiting, requiring minimal intervention including parenteral fluid resuscitation, pain control, and restriction of oral intake. Most cases can be attributed to gallstones or excessive alcohol use, but approximately 25% of cases are idiopathic.1 Other causes include hypertriglyceridemia, infection, hypercalcemia, and medications such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, trimethoprim sulfa-methoxazole, and furosemide. Severe necrotizing pancreatitis represents about 20% of all cases, but carries a mortality rate of between 10% and 30%.1

Diagnosis is based on clinical features in conjunction with biochemical markers. Amylase is nonspecific, but levels 3 times the upper limit of normal are usually diagnostic of acute pancreatitis. Lipase is 85% to 100% sensitive for pancreatitis, and is more specific than amylase. Alanine aminotransferase >150 IU/L is 96% specific for gallstone pancreatitis.2 Of note: there is no evidence to support daily monitoring of these enzyme levels as predictors of clinical improvement or disease severity.

FIGURE

CT scan of abdomen taken on second day of admission

Predicting severity at time of presentation can be difficult

As was true with our patient, predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis at the time of presentation can be difficult. Scoring systems that are commonly used to evaluate disease severity include Ranson’s score, APACHE-II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II), and CT severity index, among others (TABLE). Of these, the APACHE-II score has been found to be most predictive of progression to severe disease, with accuracy of up to 75%.3

Recent studies have shown that a body mass index >30 kg/m2 is an independent risk factor for progression to severe pancreatitis.4 Other clinical predictors include poor urine output, rising hematocrit, agitation or confusion, and lack of improvement in symptoms within 48 hours.1

Though our patient came in with symptoms that were initially mild, she quickly manifested several clinical predictors for severe pancreatitis, including poor urine output and increasing confusion, as well as an APACHE-II score of 12 at 6 hours after presentation (values ≥8 indicate high risk for progression to severe disease).

TABLE

Predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis1

| Ranson score ≥3 |

| APACHE-II score ≥8 |

| CT severity index (CT grade + necrosis score) >6 |

| Body mass index >30 kg/m2 |

| Hematocrit >44% (clearly increases risk for pancreatic necrosis) |

Clinical findings:

|

| Lack of improvement in symptoms within the first 48 hours |

| APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CT, computed tomography. |

Role of antibiotics? A source of debate

Infection represents the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with pancreatic necrosis. Approximately 40% of patients with necrosis develop infection, with a 20% mortality rate.5 Signs of infection usually develop relatively late in the clinical course and rates increase drastically each week a patient remains hospitalized (71% of patients have signs of infection at 3 weeks).5

Interestingly, the role for antibiotics in such patients has been a source of debate in practice, as well as in the medical literature. Two recent large meta-analyses came to different conclusions regarding the use of antibiotics. A 2006 study by Heinrich et al concluded that patients with pancreatic necrosis demonstrated by contrast-enhanced CT scans should receive antibiotic prophylaxis with imipenem or meropenem for 14 days, and that prophylactic antibiotics do not increase rates of subsequent fungal infection.6 Conversely, as noted in a 2008 study published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, “prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis.”7

Two leading professional groups have similarly contradictory recommendations on the topic, with the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) supporting antibiotic use for patients with >30% pancreatic necrosis noted on CT and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommending against the use of prophylactic antibiotics.8

As with any clinical dilemma, it seems prudent to make the decision for or against prophylactic antibiotics based on available clinical information and the particular patient’s risk factors. Clearly, in the most high-risk patients, it would be difficult to justify withholding antibiotic therapy.

Complete bowel rest—or not?

In the past, it was thought necessary to allow for complete bowel rest and suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion during acute pancreatitis by providing total parenteral nutrition.6,9 More recently, though, the use of early nasojejunal enteral feeding (which was initiated for our patient) has been advocated by several large meta-analyses,6 as well as by the AGA and ACG.2

The use of enteral feeding has been associated with improved outcomes, including lower infection rates (due to maintenance of the intestinal barrier and prevention of bacterial translocation), decreased length of stay, reduced rates of organ failure, and fewer deaths among patients who require surgical intervention.6

A lengthy road to recovery for our patient

After 7 days of mechanical ventilation, our patient was extubated. However, she developed significant bilateral pleural effusions as a result of fluid third spacing, and required thoracentesis.

She completed a 14-day course of imipenem, followed by an additional 10-day course due to hypotension and a suspected infected pseudocyst. Subsequent imaging studies confirmed our suspicions: She had developed a large pseudocyst (>13 cm), which remained under observation by both a gastroenterologist and general surgeon. Six weeks after admission, our patient was discharged to home with family.

But what was the cause? Although we were unable to clearly delineate an inciting cause for her pancreatitis during the admission, she was to undergo further investigation as an outpatient. There were also plans to drain the pseudocyst 6 weeks after discharge.

A learning opportunity. This patient’s case provided an excellent opportunity for our team to review the important clinical predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis, and the rapid nature of clinical decline in such patients. In hindsight, the predictors of severity in our patient were few, but included the rapid onset and clinical progression of her symptoms, as well as her elevated hematocrit on presentation and poor urine output over the first 6 hours of admission.

• Use the APACHE-II scoring system early on to help predict the severity of pancreatitis.

• Consider early enteral nutrition in patients with severe disease; taking this step has been linked to lower infection rates and shorter lengths of stay.

• Consider patient factors and the risk of severe infection when deciding whether or not to use prophylactic antibiotics in cases of severe necrotizing pancreatitis.

CASE A 57-year-old Caucasian woman sought care at our emergency department (ED) for diffuse abdominal pain and nausea. She said that the pain began after eating lunch earlier that day, and localized periumbilically, with radiation to the back. She had several episodes of nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting, but denied fever, chills, or diarrhea.

Her past medical history was notable only for an episode of gallstone pancreatitis 11 years earlier, after which she underwent a cholecystectomy. Her only medications were ibandronate sodium (Boniva) taken for osteoporosis (diagnosed 2 years earlier), a multivitamin, calcium, magnesium, and vitamin E supplements. Her family history was notable for a brother who had pancreatic cancer in his 50s. The patient reported infrequent alcohol use.

The abdominal exam was notable for diffuse tenderness to palpation, most prominent in the epigastric region. The patient exhibited voluntary guarding, without rebound, and positive bowel sounds throughout.

The patient’s laboratory studies on admission included leukocytosis of 21,300 cells/mcL and hemoglobin and hematocrit of 17.3 g/dL and 52.1%, respectively. She had an amylase of 1733 U/L and lipase of 4288 U/L. Lactate and lactic dehydrogenase were 1.83 mg/dL and 265 U/L, respectively. Liver function tests and a basic metabolic panel were within normal limits. A noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis was notable for an enlarged pancreas with peripancreatic edema and free fluid in the abdomen.

The patient underwent aggressive fluid resuscitation throughout the first 6 hours of her hospital stay. Urine output was noted to be incongruent with fluid intake, at just over 60 cc/h. Over the next 4 hours, she became progressively tachycardic, tachypneic, and somnolent, with increasing abdominal tenderness. Her serum potassium level rose to 4.9 mEq/L, while serum bicarbonate declined to 13 mEq/L and serum calcium, to 6.2 mg/dL. Arterial blood gas revealed metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.22.

Our patient was subsequently transferred to the medical intensive care unit, where she required endotracheal intubation.

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HER CONDITION?

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis

A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast taken on the second day of admission revealed extensive pancreatitis with complete disintegration of the pancreatic tissue and absence of pancreatic enhancement (FIGURE), as well as a large amount of abdominal ascites.

Pancreatitis is a common inpatient diagnosis, with approximately 200,000 hospitalizations yearly.1 Most cases are mild and self-limiting, requiring minimal intervention including parenteral fluid resuscitation, pain control, and restriction of oral intake. Most cases can be attributed to gallstones or excessive alcohol use, but approximately 25% of cases are idiopathic.1 Other causes include hypertriglyceridemia, infection, hypercalcemia, and medications such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, trimethoprim sulfa-methoxazole, and furosemide. Severe necrotizing pancreatitis represents about 20% of all cases, but carries a mortality rate of between 10% and 30%.1

Diagnosis is based on clinical features in conjunction with biochemical markers. Amylase is nonspecific, but levels 3 times the upper limit of normal are usually diagnostic of acute pancreatitis. Lipase is 85% to 100% sensitive for pancreatitis, and is more specific than amylase. Alanine aminotransferase >150 IU/L is 96% specific for gallstone pancreatitis.2 Of note: there is no evidence to support daily monitoring of these enzyme levels as predictors of clinical improvement or disease severity.

FIGURE

CT scan of abdomen taken on second day of admission

Predicting severity at time of presentation can be difficult

As was true with our patient, predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis at the time of presentation can be difficult. Scoring systems that are commonly used to evaluate disease severity include Ranson’s score, APACHE-II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II), and CT severity index, among others (TABLE). Of these, the APACHE-II score has been found to be most predictive of progression to severe disease, with accuracy of up to 75%.3

Recent studies have shown that a body mass index >30 kg/m2 is an independent risk factor for progression to severe pancreatitis.4 Other clinical predictors include poor urine output, rising hematocrit, agitation or confusion, and lack of improvement in symptoms within 48 hours.1

Though our patient came in with symptoms that were initially mild, she quickly manifested several clinical predictors for severe pancreatitis, including poor urine output and increasing confusion, as well as an APACHE-II score of 12 at 6 hours after presentation (values ≥8 indicate high risk for progression to severe disease).

TABLE

Predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis1

| Ranson score ≥3 |

| APACHE-II score ≥8 |

| CT severity index (CT grade + necrosis score) >6 |

| Body mass index >30 kg/m2 |

| Hematocrit >44% (clearly increases risk for pancreatic necrosis) |

Clinical findings:

|

| Lack of improvement in symptoms within the first 48 hours |

| APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CT, computed tomography. |

Role of antibiotics? A source of debate

Infection represents the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with pancreatic necrosis. Approximately 40% of patients with necrosis develop infection, with a 20% mortality rate.5 Signs of infection usually develop relatively late in the clinical course and rates increase drastically each week a patient remains hospitalized (71% of patients have signs of infection at 3 weeks).5

Interestingly, the role for antibiotics in such patients has been a source of debate in practice, as well as in the medical literature. Two recent large meta-analyses came to different conclusions regarding the use of antibiotics. A 2006 study by Heinrich et al concluded that patients with pancreatic necrosis demonstrated by contrast-enhanced CT scans should receive antibiotic prophylaxis with imipenem or meropenem for 14 days, and that prophylactic antibiotics do not increase rates of subsequent fungal infection.6 Conversely, as noted in a 2008 study published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, “prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis.”7

Two leading professional groups have similarly contradictory recommendations on the topic, with the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) supporting antibiotic use for patients with >30% pancreatic necrosis noted on CT and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommending against the use of prophylactic antibiotics.8

As with any clinical dilemma, it seems prudent to make the decision for or against prophylactic antibiotics based on available clinical information and the particular patient’s risk factors. Clearly, in the most high-risk patients, it would be difficult to justify withholding antibiotic therapy.

Complete bowel rest—or not?

In the past, it was thought necessary to allow for complete bowel rest and suppression of pancreatic exocrine secretion during acute pancreatitis by providing total parenteral nutrition.6,9 More recently, though, the use of early nasojejunal enteral feeding (which was initiated for our patient) has been advocated by several large meta-analyses,6 as well as by the AGA and ACG.2

The use of enteral feeding has been associated with improved outcomes, including lower infection rates (due to maintenance of the intestinal barrier and prevention of bacterial translocation), decreased length of stay, reduced rates of organ failure, and fewer deaths among patients who require surgical intervention.6

A lengthy road to recovery for our patient

After 7 days of mechanical ventilation, our patient was extubated. However, she developed significant bilateral pleural effusions as a result of fluid third spacing, and required thoracentesis.

She completed a 14-day course of imipenem, followed by an additional 10-day course due to hypotension and a suspected infected pseudocyst. Subsequent imaging studies confirmed our suspicions: She had developed a large pseudocyst (>13 cm), which remained under observation by both a gastroenterologist and general surgeon. Six weeks after admission, our patient was discharged to home with family.

But what was the cause? Although we were unable to clearly delineate an inciting cause for her pancreatitis during the admission, she was to undergo further investigation as an outpatient. There were also plans to drain the pseudocyst 6 weeks after discharge.

A learning opportunity. This patient’s case provided an excellent opportunity for our team to review the important clinical predictors for progression to severe pancreatitis, and the rapid nature of clinical decline in such patients. In hindsight, the predictors of severity in our patient were few, but included the rapid onset and clinical progression of her symptoms, as well as her elevated hematocrit on presentation and poor urine output over the first 6 hours of admission.

1. Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150.

2. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS. ed. UpTo-Date [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpTo-Date; 2010.

3. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

4. Skipworth JRA, Pereira SP. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:172-178.

5. Windsor JA, Schweder P. Complications of acute pancreatitis (including pseudocysts). In: Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, eds. Main-got’s Abdominal Operations. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007:chap 37. Available at: http://www.accesssurgery.com/content.aspx?filename="6003JFP_HospitalRounds" aid=130125. Accessed November 30, 2010.

6. Heinrich S, Shafer M, Rousson V, et al. Evidenced-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154-168.

7. Bai Y, Gao J, Zou DW, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:104-110.

8. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Treatment of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

9. Haney JC, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1431-1446.

1. Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2142-2150.

2. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS. ed. UpTo-Date [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpTo-Date; 2010.

3. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Predicting severity of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

4. Skipworth JRA, Pereira SP. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:172-178.

5. Windsor JA, Schweder P. Complications of acute pancreatitis (including pseudocysts). In: Zinner MJ, Ashley SW, eds. Main-got’s Abdominal Operations. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007:chap 37. Available at: http://www.accesssurgery.com/content.aspx?filename="6003JFP_HospitalRounds" aid=130125. Accessed November 30, 2010.

6. Heinrich S, Shafer M, Rousson V, et al. Evidenced-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154-168.

7. Bai Y, Gao J, Zou DW, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot reduce infected pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:104-110.

8. Vege SS, Whitcomb DC, Ginsburg CH. Treatment of acute pancreatitis. In: Basow DS, ed. UpToDate [online database]. Version 18.2. Waltham, Mass: UpToDate; 2010.

9. Haney JC, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1431-1446.

How best to diagnose asthma in infants and toddlers?

NO RELIABLE WAY EXISTS TO DIAGNOSE ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS. Recurrent wheezing, especially apart from colds, combined with physician-diagnosed eczema or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilia, and a parental history of asthma, increase the probability of a subsequent asthma diagnosis in the absence of other causes (strength of recommendation: B, 2 good-quality cohort studies).

Evidence summary

Wheezing in children is common and the differential diagnosis is broad. The many potential causes include upper respiratory infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, foreign body aspiration, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, primary immunodeficiency, and congenital heart disease.1

Outpatient primary care cohort studies estimate that about half of children wheeze before they reach school age. Only one-third of children who wheeze during the first 3 years of life, however, continue to wheeze into later childhood and young adulthood.2-4

These findings have led some experts to suggest that not all wheezing in children is asthma and that asthma exists in variant forms.5-7 Variant wheezing patterns include transient early wheezing, which seems to be most prevalent in the first 3 years of life; wheezing without atopy, which occurs most often at 3 to 6 years of age; and wheezing with immunoglobulin E-associated atopy, which gradually increases in prevalence from birth and dominates in the over-6 age group. It is children in this last group whom we generally consider to have asthma.

Objective measures of lung function are challenging to perform in young children. Clinical signs and symptoms thus suggest the diagnosis of asthma.

Atopy, rhinitis, and eczema most often accompany persistent wheezing

Primary care cohort studies provide the best available evidence on which findings in infants and toddlers most likely predict persistent airway disease in childhood. A whole-population cohort study followed nearly all children born on the Isle of Wight from January 1989 through February 1990 to evaluate the natural history of childhood wheezing and to study associated risk factors.8 Children were seen at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 10 years of age.

Findings most associated with current wheezing (within the last year) in 10-year-olds were atopy (odds ratio [OR]=4.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.07-6.25), rhinitis (OR=3.72; 95% CI, 2.21-6.27), and eczema (OR=3.04; 95% CI, 2.05-4.51).8

An index to predict asthma

Since 1980, the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study has followed 1246 healthy newborns seen by pediatricians affiliated with a large HMO in Tucson, Arizona. Questionnaires about parental asthma history and prenatal smoking history were obtained at enrollment. Childhood wheezing and its frequency, as well as physician-diagnosed allergies or asthma, were assessed at ages 2 and 3. If the child had wheezed in the past year, then the child was considered to be an “early wheezer.” If the frequency was 3 or more on a 5-point scale, then the child was considered to be an “early frequent wheezer.” Questionnaires were re-administered at ages 6, 8, 11, and 13. Three episodes of wheezing within the past year or a physician diagnosis of asthma with symptoms in the past year was considered “active asthma.” Blood specimens for eosinophils were obtained at age 10.

Using these data, the researchers developed stringent and loose criteria (TABLE 1) and odds ratios (TABLES 2 and 3) for childhood factors most predictive of an asthma diagnosis at an older age. The findings of the study may help clinicians care for wheezing infants and toddlers.9

TABLE 1

A clinical index of asthma risk9*

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Parental asthma (history of physician diagnosis of asthma in a parent) | Allergic rhinitis (physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) |

| Eczema (physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) | Wheezing apart from colds |

| Eosinophilia (≥4%) | |

| *Stringent index for predicting asthma: Child has early, frequent wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. Loose index for predicting asthma: Child has early wheezing plus at least 1 of the 2 major criteria or 2 of the 3 minor criteria. | |

TABLE 2

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by stringent index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 9.8 (5.6-17.2) | 27.5 (24.6-30.4) | 96.3 (95.1-97.5) | 47.5 (44.3-50.7) | 91.6 (89.8-93.4) |

| At 8 y | 5.8 (2.9-11.2) | 16.3 (13.7-18.9) | 96.7 (95.4-98.0) | 43.6 (40.1-47.1) | 88.2 (85.9-90.5) |

| At 11 y | 4.3 (2.4-7.8) | 15 (12.6-17.4) | 96.1 (94.8-97.4) | 42.0 (38.7-45.3) | 85.6 (83.3-87.9) |

| At 13 y | 5.7 (2.8-11.6) | 14.8 (12.1-17.5) | 97.0 (95.7-98.3) | 51.5 (47.7-55.3) | 84.2 (81.4-87.0) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

TABLE 3

Likelihood of active asthma predicted by loose index9

| Active asthma | OR (95% CI) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % (95% CI) | NPV, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 6 y | 5.5 (3.5-8.4) | 56.6 (53.3-59.9) | 80.8 (78.3-83.3) | 26.2 (23.4-29.0) | 93.9 (92.4-95.4) |

| At 8 y | 4.4 (2.8-6.8) | 50.5 (47.0-54.0) | 81.1 (78.3-83.9) | 29.4 (26.2-32.6) | 91.3 (89.3-93.3) |

| At 11 y | 2.6 (1.8-3.8) | 40.1 (36.8-43.4) | 79.6 (76.9-82.3) | 27.1 (24.1-30.1) | 87.5 (85.3-89.7) |

| At 13 y | 3.0 (1.9-4.6) | 39.3 (35.5-43.1) | 82.1 (79.1-85.1) | 31.7 (28.1-35.3) | 86.5 (83.9-89.1) |

| CI, confidence interval; NPV, negative predictive value; OR, odds ratio; PPV, positive predictive value. | |||||

Recommendations

A European and United States expert panel guide to the diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood, PRACTALL, states that “asthma should be suspected in any infant with recurrent wheezing and cough episodes. Frequently, diagnosis is possible only through long-term follow-up, consideration of the extensive differential diagnoses, and by observing the child’s response to bronchodilator and/or anti-inflammatory treatment.”10

The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program’s Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3) notes that diagnostic evaluation for asthma in children 0 to 4 years of age should include history, symptoms, physical examination, and assessment of quality of life.1

1. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. NIH publication 07-4051. Bethesda, Md: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 2007. Available at: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. Accessed June 20, 2008.

2. Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. The Group Health Medical Associates. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133-138.

3. Sears MR, Greene JM, Willan AR, et al. A longitudinal, population-based cohort study of childhood asthma followed to adulthood. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1414-1422.

4. Jenkins MA, Hopper JL, Bowes G, et al. Factors in childhood as predictors of asthma in adult life. BMJ. 1994;309:90-93.

5. Rusconi F, Galassi C, Corbo GM, et al. Risk factors for early, persistent, and late-onset wheezing in young children. SIDRIA Collaborative Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;167:1617-1622.

6. Stein RT, Martinez FD. Asthma phenotypes in childhood: lessons from an epidemiologic approach. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004;5:155-161.

7. Stein RT, Holberg CJ, Morgan WJ, et al. Peak flow variability, methacholine responsiveness and atopy as markers for detecting different wheezing phenotypes in childhood. Thorax. 1997;52:946-952.

8. Arshad SH, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, et al. Early life risk factors for current wheeze, asthma, and bronchial hyper-responsiveness at 10 years of age. Chest. 2005;127:502-508.

9. Castro-Rodriguez JA, Holberg CJ, Wright AL, et al. A clinical index to define risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1403-1406.

10. Bacharier LB, Boner A, Carlsen KH, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy. 2008;63:5-34.

NO RELIABLE WAY EXISTS TO DIAGNOSE ASTHMA IN INFANTS AND TODDLERS. Recurrent wheezing, especially apart from colds, combined with physician-diagnosed eczema or atopic dermatitis, eosinophilia, and a parental history of asthma, increase the probability of a subsequent asthma diagnosis in the absence of other causes (strength of recommendation: B, 2 good-quality cohort studies).

Evidence summary

Wheezing in children is common and the differential diagnosis is broad. The many potential causes include upper respiratory infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, foreign body aspiration, vascular ring, tracheomalacia, primary immunodeficiency, and congenital heart disease.1

Outpatient primary care cohort studies estimate that about half of children wheeze before they reach school age. Only one-third of children who wheeze during the first 3 years of life, however, continue to wheeze into later childhood and young adulthood.2-4

These findings have led some experts to suggest that not all wheezing in children is asthma and that asthma exists in variant forms.5-7 Variant wheezing patterns include transient early wheezing, which seems to be most prevalent in the first 3 years of life; wheezing without atopy, which occurs most often at 3 to 6 years of age; and wheezing with immunoglobulin E-associated atopy, which gradually increases in prevalence from birth and dominates in the over-6 age group. It is children in this last group whom we generally consider to have asthma.

Objective measures of lung function are challenging to perform in young children. Clinical signs and symptoms thus suggest the diagnosis of asthma.

Atopy, rhinitis, and eczema most often accompany persistent wheezing

Primary care cohort studies provide the best available evidence on which findings in infants and toddlers most likely predict persistent airway disease in childhood. A whole-population cohort study followed nearly all children born on the Isle of Wight from January 1989 through February 1990 to evaluate the natural history of childhood wheezing and to study associated risk factors.8 Children were seen at birth and at 1, 2, 4, and 10 years of age.

Findings most associated with current wheezing (within the last year) in 10-year-olds were atopy (odds ratio [OR]=4.38; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.07-6.25), rhinitis (OR=3.72; 95% CI, 2.21-6.27), and eczema (OR=3.04; 95% CI, 2.05-4.51).8

An index to predict asthma

Since 1980, the Tucson Children’s Respiratory Study has followed 1246 healthy newborns seen by pediatricians affiliated with a large HMO in Tucson, Arizona. Questionnaires about parental asthma history and prenatal smoking history were obtained at enrollment. Childhood wheezing and its frequency, as well as physician-diagnosed allergies or asthma, were assessed at ages 2 and 3. If the child had wheezed in the past year, then the child was considered to be an “early wheezer.” If the frequency was 3 or more on a 5-point scale, then the child was considered to be an “early frequent wheezer.” Questionnaires were re-administered at ages 6, 8, 11, and 13. Three episodes of wheezing within the past year or a physician diagnosis of asthma with symptoms in the past year was considered “active asthma.” Blood specimens for eosinophils were obtained at age 10.

Using these data, the researchers developed stringent and loose criteria (TABLE 1) and odds ratios (TABLES 2 and 3) for childhood factors most predictive of an asthma diagnosis at an older age. The findings of the study may help clinicians care for wheezing infants and toddlers.9

TABLE 1

A clinical index of asthma risk9*

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Parental asthma (history of physician diagnosis of asthma in a parent) | Allergic rhinitis (physician diagnosis of allergic rhinitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) |

| Eczema (physician diagnosis of atopic dermatitis as reported in questionnaires at ages 2 or 3 y) | Wheezing apart from colds |

| Eosinophilia (≥4%) | |