User login

Verify Your Liability Coverage before Taking that New Job

Does your employer provide your medical malpractice insurance coverage? Are you looking for new employment? Are you in the market to purchase a professional malpractice insurance policy? Are you planning to retire soon?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, you likely will confront the concept of “tail” insurance at some point in your medical career.

Now is the time to dust off your employment agreement and professional liability insurance policy and review what happens in the event a lawsuit is filed against you after you leave your current employer. This means paying special attention to whether your professional liability insurance policy provides for claims-made or occurrence-based coverage, and, if it’s the former, who is responsible for purchasing tail coverage.

When Do I Need Tail Coverage?

Tail insurance issues frequently arise when a physician leaves his or her place of employment, whether due to switching jobs, retirement, or a buyout of a physician’s ownership interest. If the physician is leaving an employer that has claims-made professional liability insurance, the physician’s insurance coverage might not be seamless. Instead, tail or similar coverage is required.

Claims-made coverage protects a physician for professional negligence, as long as a two-part test is met: First, the physician must have the claims-made coverage in place when the negligent act occurs (with employer No. 1); second, the physician must be covered by the same carrier when he or she is notified of the claim while employed by employer No. 2. If either test is not satisfied, the current claims-made insurance policy will not provide coverage to the physician in the event a lawsuit is filed for an act of negligence that took place while employed by employer No. 1. Alternatively, some employers offer “nose” coverage from its insurance carrier, which will cover negligent acts that might have occurred during your current job. The vast majority of professional liability insurance policies written for medical practice groups are for claims-made coverage.

If, however, an employer has occurrence-based professional liability insurance, the departing physician’s insurance coverage is seamless and no tail insurance is required.

Example A

Here is a common example of what happens when a physician leaves an employer with claims-made professional liability coverage:

An employer maintains claims-made professional liability insurance coverage for its physicians with ABC Insurance Co. A physician decides to leave his or her current employer and accepts employment by a new employer, which maintains claims-made coverage with XYZ Insurance Co.

Within a few months of the physician’s new employment, a medical malpractice lawsuit is filed by a patient for medical treatment the patient received when the physician was employed by the former employer. By leaving the former employer, the departing physician automatically fails the two-part test for claims-made coverage, as the second prong is not satisfied. Therefore, even though the physician has liability coverage through the new employer, this insurance policy will not cover the lawsuit described above.

Unless the physician has tail insurance (or nose coverage) to cover lawsuits related to the former employment, a gap in liability coverage will exist. If claims-made insurance is the benefit you have received in your employment agreement, it is imperative that you understand that tail coverage is necessary when you leave.

However, if a physician leaves and a) is subsequently employed within the same state and b) stays insured by the same insurance carrier, then the insurance carrier will provide continuous coverage and no tail insurance policy is needed.

Who Pays the Premium?

If the physician will need tail coverage, the next critical question is, Who pays for such coverage? Even though tail coverage comes into effect when a physician leaves an employer, tail coverage should be addressed before the physician informs the employer of their departure; an even better approach would be while the employment agreement is negotiated. Payment of tail coverage should be defined in the physician’s employment agreement.

In terms of payment for the coverage, there are several options. First, the cost of tail coverage can be attributed 100% to either physician or employer. In specialties for which recruitment of new physicians is challenging (i.e. HM), employers are more likely to pay a substantial portion, if not all, of the cost as a benefit or inducement.

Second, the physician can connect the payment of tail coverage to the manner in which employment is terminated. For example, if the physician terminates the agreement for cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment without cause, the employer could be required to pay for the tail insurance. Alternatively, if the physician terminates the agreement without cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment with cause, the physician could be required to pay for the tail coverage. Frequently, physician employment agreements require physicians to pay for tail coverage if the physician violates a restrictive covenant (e.g. non-competition).

A third option is to split the cost of tail insurance between the former employer and the physician based on a percentage, or to include a vesting schedule, for example, such that the former employer pays one-third of the coverage if employment ends in the second year, two-thirds of the coverage if employment ends in the third year, and 100% of the coverage if employment ends in the fourth year or later.

Whatever arrangement the parties agree upon should be included in the physician’s employment agreement in order to prevent an expensive surprise.

Review Your Policy

Now that you have an understanding of claims-made coverage, occurrence-based coverage and tail insurance, it’s time to review your insurance policy. When reviewing your current policy, look for answers to the following important questions:

- Is your policy claims-made or occurrence-based?

- Does your insurance policy only cover professional negligence claims? Does your policy also cover claims of unprofessional conduct reported to state medical licensing boards? Does your policy also cover medical staff bylaw disputes and state licensing matters?

- How is loss defined? “Pure loss” is coverage for the amount awarded to the plaintiff; “ultimate net loss” covers what pure loss covers, plus attorneys’ fees and costs.

- What procedures do you need to follow in order to properly notify the insurance carrier of a claim? Are you precluded from full coverage if you fail to properly report?

- What does the “duty to defend” provision cover? Will you be reimbursed for lost wages for your time in court? What services will be provided as part of your defense?

- What does the “consent to settle” provision say? If a settlement is negotiated between the plaintiff (patient) and the insurance company and the physician does not consent to the settlement, is the physician responsible for the ongoing defense costs and the amount of any verdict in excess of the recommended settlement amount?

It is important to both understand your insurance policy and what your employment agreement says about the policy. If you will be responsible for purchasing a tail policy at the end of your current employment, you should be well aware—and financially prepared—for this post-employment responsibility. Make sure your tail is not left exposed.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Does your employer provide your medical malpractice insurance coverage? Are you looking for new employment? Are you in the market to purchase a professional malpractice insurance policy? Are you planning to retire soon?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, you likely will confront the concept of “tail” insurance at some point in your medical career.

Now is the time to dust off your employment agreement and professional liability insurance policy and review what happens in the event a lawsuit is filed against you after you leave your current employer. This means paying special attention to whether your professional liability insurance policy provides for claims-made or occurrence-based coverage, and, if it’s the former, who is responsible for purchasing tail coverage.

When Do I Need Tail Coverage?

Tail insurance issues frequently arise when a physician leaves his or her place of employment, whether due to switching jobs, retirement, or a buyout of a physician’s ownership interest. If the physician is leaving an employer that has claims-made professional liability insurance, the physician’s insurance coverage might not be seamless. Instead, tail or similar coverage is required.

Claims-made coverage protects a physician for professional negligence, as long as a two-part test is met: First, the physician must have the claims-made coverage in place when the negligent act occurs (with employer No. 1); second, the physician must be covered by the same carrier when he or she is notified of the claim while employed by employer No. 2. If either test is not satisfied, the current claims-made insurance policy will not provide coverage to the physician in the event a lawsuit is filed for an act of negligence that took place while employed by employer No. 1. Alternatively, some employers offer “nose” coverage from its insurance carrier, which will cover negligent acts that might have occurred during your current job. The vast majority of professional liability insurance policies written for medical practice groups are for claims-made coverage.

If, however, an employer has occurrence-based professional liability insurance, the departing physician’s insurance coverage is seamless and no tail insurance is required.

Example A

Here is a common example of what happens when a physician leaves an employer with claims-made professional liability coverage:

An employer maintains claims-made professional liability insurance coverage for its physicians with ABC Insurance Co. A physician decides to leave his or her current employer and accepts employment by a new employer, which maintains claims-made coverage with XYZ Insurance Co.

Within a few months of the physician’s new employment, a medical malpractice lawsuit is filed by a patient for medical treatment the patient received when the physician was employed by the former employer. By leaving the former employer, the departing physician automatically fails the two-part test for claims-made coverage, as the second prong is not satisfied. Therefore, even though the physician has liability coverage through the new employer, this insurance policy will not cover the lawsuit described above.

Unless the physician has tail insurance (or nose coverage) to cover lawsuits related to the former employment, a gap in liability coverage will exist. If claims-made insurance is the benefit you have received in your employment agreement, it is imperative that you understand that tail coverage is necessary when you leave.

However, if a physician leaves and a) is subsequently employed within the same state and b) stays insured by the same insurance carrier, then the insurance carrier will provide continuous coverage and no tail insurance policy is needed.

Who Pays the Premium?

If the physician will need tail coverage, the next critical question is, Who pays for such coverage? Even though tail coverage comes into effect when a physician leaves an employer, tail coverage should be addressed before the physician informs the employer of their departure; an even better approach would be while the employment agreement is negotiated. Payment of tail coverage should be defined in the physician’s employment agreement.

In terms of payment for the coverage, there are several options. First, the cost of tail coverage can be attributed 100% to either physician or employer. In specialties for which recruitment of new physicians is challenging (i.e. HM), employers are more likely to pay a substantial portion, if not all, of the cost as a benefit or inducement.

Second, the physician can connect the payment of tail coverage to the manner in which employment is terminated. For example, if the physician terminates the agreement for cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment without cause, the employer could be required to pay for the tail insurance. Alternatively, if the physician terminates the agreement without cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment with cause, the physician could be required to pay for the tail coverage. Frequently, physician employment agreements require physicians to pay for tail coverage if the physician violates a restrictive covenant (e.g. non-competition).

A third option is to split the cost of tail insurance between the former employer and the physician based on a percentage, or to include a vesting schedule, for example, such that the former employer pays one-third of the coverage if employment ends in the second year, two-thirds of the coverage if employment ends in the third year, and 100% of the coverage if employment ends in the fourth year or later.

Whatever arrangement the parties agree upon should be included in the physician’s employment agreement in order to prevent an expensive surprise.

Review Your Policy

Now that you have an understanding of claims-made coverage, occurrence-based coverage and tail insurance, it’s time to review your insurance policy. When reviewing your current policy, look for answers to the following important questions:

- Is your policy claims-made or occurrence-based?

- Does your insurance policy only cover professional negligence claims? Does your policy also cover claims of unprofessional conduct reported to state medical licensing boards? Does your policy also cover medical staff bylaw disputes and state licensing matters?

- How is loss defined? “Pure loss” is coverage for the amount awarded to the plaintiff; “ultimate net loss” covers what pure loss covers, plus attorneys’ fees and costs.

- What procedures do you need to follow in order to properly notify the insurance carrier of a claim? Are you precluded from full coverage if you fail to properly report?

- What does the “duty to defend” provision cover? Will you be reimbursed for lost wages for your time in court? What services will be provided as part of your defense?

- What does the “consent to settle” provision say? If a settlement is negotiated between the plaintiff (patient) and the insurance company and the physician does not consent to the settlement, is the physician responsible for the ongoing defense costs and the amount of any verdict in excess of the recommended settlement amount?

It is important to both understand your insurance policy and what your employment agreement says about the policy. If you will be responsible for purchasing a tail policy at the end of your current employment, you should be well aware—and financially prepared—for this post-employment responsibility. Make sure your tail is not left exposed.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Does your employer provide your medical malpractice insurance coverage? Are you looking for new employment? Are you in the market to purchase a professional malpractice insurance policy? Are you planning to retire soon?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, you likely will confront the concept of “tail” insurance at some point in your medical career.

Now is the time to dust off your employment agreement and professional liability insurance policy and review what happens in the event a lawsuit is filed against you after you leave your current employer. This means paying special attention to whether your professional liability insurance policy provides for claims-made or occurrence-based coverage, and, if it’s the former, who is responsible for purchasing tail coverage.

When Do I Need Tail Coverage?

Tail insurance issues frequently arise when a physician leaves his or her place of employment, whether due to switching jobs, retirement, or a buyout of a physician’s ownership interest. If the physician is leaving an employer that has claims-made professional liability insurance, the physician’s insurance coverage might not be seamless. Instead, tail or similar coverage is required.

Claims-made coverage protects a physician for professional negligence, as long as a two-part test is met: First, the physician must have the claims-made coverage in place when the negligent act occurs (with employer No. 1); second, the physician must be covered by the same carrier when he or she is notified of the claim while employed by employer No. 2. If either test is not satisfied, the current claims-made insurance policy will not provide coverage to the physician in the event a lawsuit is filed for an act of negligence that took place while employed by employer No. 1. Alternatively, some employers offer “nose” coverage from its insurance carrier, which will cover negligent acts that might have occurred during your current job. The vast majority of professional liability insurance policies written for medical practice groups are for claims-made coverage.

If, however, an employer has occurrence-based professional liability insurance, the departing physician’s insurance coverage is seamless and no tail insurance is required.

Example A

Here is a common example of what happens when a physician leaves an employer with claims-made professional liability coverage:

An employer maintains claims-made professional liability insurance coverage for its physicians with ABC Insurance Co. A physician decides to leave his or her current employer and accepts employment by a new employer, which maintains claims-made coverage with XYZ Insurance Co.

Within a few months of the physician’s new employment, a medical malpractice lawsuit is filed by a patient for medical treatment the patient received when the physician was employed by the former employer. By leaving the former employer, the departing physician automatically fails the two-part test for claims-made coverage, as the second prong is not satisfied. Therefore, even though the physician has liability coverage through the new employer, this insurance policy will not cover the lawsuit described above.

Unless the physician has tail insurance (or nose coverage) to cover lawsuits related to the former employment, a gap in liability coverage will exist. If claims-made insurance is the benefit you have received in your employment agreement, it is imperative that you understand that tail coverage is necessary when you leave.

However, if a physician leaves and a) is subsequently employed within the same state and b) stays insured by the same insurance carrier, then the insurance carrier will provide continuous coverage and no tail insurance policy is needed.

Who Pays the Premium?

If the physician will need tail coverage, the next critical question is, Who pays for such coverage? Even though tail coverage comes into effect when a physician leaves an employer, tail coverage should be addressed before the physician informs the employer of their departure; an even better approach would be while the employment agreement is negotiated. Payment of tail coverage should be defined in the physician’s employment agreement.

In terms of payment for the coverage, there are several options. First, the cost of tail coverage can be attributed 100% to either physician or employer. In specialties for which recruitment of new physicians is challenging (i.e. HM), employers are more likely to pay a substantial portion, if not all, of the cost as a benefit or inducement.

Second, the physician can connect the payment of tail coverage to the manner in which employment is terminated. For example, if the physician terminates the agreement for cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment without cause, the employer could be required to pay for the tail insurance. Alternatively, if the physician terminates the agreement without cause or if the employer terminates the physician’s employment with cause, the physician could be required to pay for the tail coverage. Frequently, physician employment agreements require physicians to pay for tail coverage if the physician violates a restrictive covenant (e.g. non-competition).

A third option is to split the cost of tail insurance between the former employer and the physician based on a percentage, or to include a vesting schedule, for example, such that the former employer pays one-third of the coverage if employment ends in the second year, two-thirds of the coverage if employment ends in the third year, and 100% of the coverage if employment ends in the fourth year or later.

Whatever arrangement the parties agree upon should be included in the physician’s employment agreement in order to prevent an expensive surprise.

Review Your Policy

Now that you have an understanding of claims-made coverage, occurrence-based coverage and tail insurance, it’s time to review your insurance policy. When reviewing your current policy, look for answers to the following important questions:

- Is your policy claims-made or occurrence-based?

- Does your insurance policy only cover professional negligence claims? Does your policy also cover claims of unprofessional conduct reported to state medical licensing boards? Does your policy also cover medical staff bylaw disputes and state licensing matters?

- How is loss defined? “Pure loss” is coverage for the amount awarded to the plaintiff; “ultimate net loss” covers what pure loss covers, plus attorneys’ fees and costs.

- What procedures do you need to follow in order to properly notify the insurance carrier of a claim? Are you precluded from full coverage if you fail to properly report?

- What does the “duty to defend” provision cover? Will you be reimbursed for lost wages for your time in court? What services will be provided as part of your defense?

- What does the “consent to settle” provision say? If a settlement is negotiated between the plaintiff (patient) and the insurance company and the physician does not consent to the settlement, is the physician responsible for the ongoing defense costs and the amount of any verdict in excess of the recommended settlement amount?

It is important to both understand your insurance policy and what your employment agreement says about the policy. If you will be responsible for purchasing a tail policy at the end of your current employment, you should be well aware—and financially prepared—for this post-employment responsibility. Make sure your tail is not left exposed.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney and a member of the law firm McDonald Hopkins LLC in Chicago. Write to him at [email protected].

Nigerian-Born Hospitalist Steers Career Down Path of Administrative Challenges

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

In some ways, Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, CPE, SFHM, seemed destined to become a physician. He grew up in a medical family—his mother is an orthodontist; his father is an obstetrician/gynecologist. As a child, he often spent holidays visiting patients at the hospital where his dad worked. He grew to appreciate medicine as a noble profession, and when he reached his teens, he never seriously considered another career path.

“There were times when I was in medical school, dreading having to study for the numerous tests and exams, when I wished I had someone I could have blamed my decision to go to medical school on,” says Dr. Adewunmi, a native of Nigeria who has practiced as a hospitalist in the U.S. since 2003. “But no one pushed me to do it. It was something I always looked forward to doing, and I’m very glad I stuck with it.”

Dr. Adewunmi has only become more passionate about his work since then. His experience as a front-line hospitalist laid the foundation for a series of leadership roles, first directing the HM program at Johnston Memorial Hospital in Smithfield, N.C., and now as regional chief medical officer for Sound Physicians, which provides inpatient services to more than 70 hospitals nationally.

“I really want to be a good physician executive,” he says. “It’s definitely a case of ‘The more you learn, the more you realize how little you know.’ I still have a lot to learn, but I’m looking forward to the challenge.”

When did you decide to go into HM?

During residency, I realized I loved taking care of patients in the hospital, both along the wards and in the ICU. I enjoyed my outpatient clinics but found myself looking for any reason I could to stay in the hospital caring for patients. I was interested in patient safety and I was doing a little bit of utilization review, so I also felt it would give me a great overall perspective of the healthcare system.

What about leading the hospitalist program at Johnston Memorial appealed to you?

I enjoyed clinical medicine, and I still do, but I was looking to do more. I wanted to make an impact at a systems level, and I knew, to do that, I eventually had to gain some leadership experience.

What is the most valuable lesson you learned in that role?

Understanding that change doesn’t happen instantaneously. For instance, as a clinician, you sometimes admit patients with congestive heart failure. You diagnose correctly, treat appropriately, and in a few days, the patients do better and go home. You get pretty swift gratification. Administration is much different. You put processes in place and it could take weeks or several quarters before you start to see the effects of the changes you implement.

What appealed to you about moving from a single-site leadership position at Johnston to a regional position with Sound?

I wanted to continue evolving. I wanted more of a challenge and was seeking opportunities where I would have operational responsibility—overseeing performance improvement in quality, satisfaction, and financial performance for several programs. In addition, I wanted to be accountable for physician development, recruiting, negotiations, and the whole gamut of business development. It was the next logical step in my career.

Why did you pursue an MBA?

I’d made that decision just before I got into medical school. I recall first thinking about it after a conversation I had with my father as a teenager. When I told him that I had made up my mind to study medicine, he said, “You should consider getting an MBA as well. Your generation is going to need to have business experience and expertise, and be better in that area than our generation was.” It’s been invaluable for me in terms of preparing me for handling the business side of medicine, including ways to make operations more efficient and to reduce costs without compromising the quality of care provided.

You have worked in both hospital-employed and privately contracted HM programs. Do you prefer one model?

In general, the larger organizations tend to have an advantage in that they have established protocols and processes that work and have been refined over time. Couple that with the economies of scale they enjoy, as we move into an era of value-based purchasing, it’s becoming harder for the smaller community-based hospital to do that as well. That said, I have seen local hospital-run programs that function really well and have administrative support, so there is definitely enough room for both models.

You were in the inaugural FHM class. What did that recognition mean to you?

I saw it as validation of how we were starting to mature as a specialty and as recognition of a commitment to being a hospitalist, not just an internist. I never practiced outpatient medicine. I went straight from residency to hospitalist medicine. That’s how I identify myself, and I was happy to see that physicians specializing in hospital medicine were starting to get recognized.

What is your biggest professional reward?

The satisfaction from knowing you’re making a difference—not just by the care you provide one-on-one to your patients, but also knowing you’re contributing at a systems level or a population level because you’re making decisions and trying to redefine processes that actually could impact a much larger cohort.

What is your biggest professional challenge?

Trying to find enough hours in the day to do all that needs to be done.

What is next for you professionally?

I enjoy having varied opportunities and being involved in many different aspects of operations. That’s what attracted me to a larger company such as Sound Physicians, and I see myself staying in that type of role. Down the road, I’d love to be able to take some of my knowledge to Nigeria and find a way to help develop and shape the healthcare sector back home.

Why would that mean so much to you?

It would be a chance to give back. We still have people dying from largely preventable diseases, and our healthcare system is not what it should be. We don’t have enough physicians for the population, and most of the physicians are in urban areas.

Close to half of the members of my graduating medical school class are either in the U.S., Europe, Asia, or South Africa.

That type of brain drain has a tremendous effect over several decades. That’s a lot of talent outside the country, and we need that back home.

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Time-based billing allows hospitalists to avoid

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

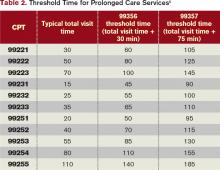

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Providers typically rely on the “key components” (history, exam, medical decision-making) when documenting in the medical record. However, there are instances when the majority of the encounter constitutes counseling/coordination of care (C/CC). Physicians might only document a brief history and exam, or nothing at all. Utilizing time-based billing principles allows a physician to disregard the “key component” requirements and select a visit level reflective of this effort.

For example, a 64-year-old female is hospitalized with newly diagnosed diabetes and requires extensive counseling regarding disease management, lifestyle modification, and medication regime, as well as coordination of care for outpatient programs and services. The hospitalist reviews some of the pertinent information with the patient and leaves the room to coordinate the patient’s ongoing care (25 minutes). The hospitalist then asks a resident to assist with the remaining counseling efforts (20 minutes). Code 99232 (inpatient visit, 25 minutes total visit time) would be appropriate to report.

Counseling, Coordination of Care

Time may be used as the determining factor for the visit level, if more than 50% of the total visit time involves C/CC.1 Time is not used for visit-level selection if C/CC is minimal or absent from the patient encounter. Total visit time is acknowledged as the physician’s face-to-face (i.e. bedside) time combined with time spent on the unit/floor reviewing data, obtaining relevant patient information, and discussing the individual case with other involved healthcare providers.

Time associated with activities performed outside of the patient’s unit/floor is not considered when calculating total visit time. Time associated with teaching students/interns also is excluded; only the attending physician’s time counts.

When the requirements have been met, the physician selects the visit level that corresponds with the documented total visit time (see Table 1). In the scenario above, the visit level is chosen based on the attending physician’s documented time (25 minutes). The resident’s time cannot be included.

Documentation Requirements

Physicians must document the interaction during the patient encounter: history and exam, if updated or performed; discussion points; and patient response, if applicable. The medical record entry must contain both the C/CC time and the total visit time.2 “Total visit time=35 minutes; >50% spent counseling/coordinating care” or “20 of 35 minutes spent counseling/coordinating care.”

A payor may prefer one documentation style over another. It is always best to ask about the payor’s policy and review local documentation standards to ensure compliance.

Family Discussions

Physicians are always involved in family discussions. It is appropriate to count this as C/CC time. In the event that the family discussion takes place without the patient present, only count this as C/CC time if:

- The patient is unable or clinically incompetent to participate in discussions;

- The time is spent on the unit/floor with the family members or surrogate decision-makers obtaining a medical history, reviewing the patient’s condition or prognosis, or discussing treatment or limitation(s) of treatment; and

- The conversation bears directly on the management of the patient.4

The medical record should reflect these criteria. Do not consider the time if the discussion takes place in an area outside of the patient’s unit/floor, or if the time is spent counseling family members through their grieving process.

It is not uncommon for the family discussion to take place later in the day, after the physician has made earlier rounds. If the earlier encounter involved C/CC, the physician would report the cumulative time spent for that service date. If the earlier encounter was a typical patient evaluation (i.e. history update and physical) and management service (i.e. care plan review/revision), this second encounter might be regarded as a prolonged care service.

Prolonged Care

Prolonged care codes exist for both outpatient and inpatient services. A hospitalists’ focus involves the inpatient code series:

99356: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, first hour; and

99357: Prolonged service in the inpatient or observation setting, requiring unit/floor time beyond the usual service, each additional 30 minutes.

Code 99356 is reported during the first hour of prolonged services, after the initial 30 minutes is reached; code 99357 is reported for each additional 30 minutes of prolonged care beyond the first hour, after the first 15 minutes of each additional segment. Both are “add on” codes and cannot be reported alone on a claim form; a “primary” code must be reported. Similarly, 99357 cannot be reported without 99356, and 99356 must be reported with one of the following inpatient service (primary) codes: 99218-99220, 99221-99223, 99231-99233, 99251-99255, 99304-99310. Only one unit of 99356 may be reported per patient per physician group per day, whereas multiple units of 99357 may be reported in a single day.

The CPT definition of prolonged care varies from that of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Since 2009, CPT recognizes the total duration spent by a physician on a given date, even if the time spent by the physician on that date is not continuous; the time involves both face-to-face time and unit/floor time.5 CMS only attributes direct face-to-face time between the physician and the patient toward prolonged care billing. Time spent reviewing charts or discussion of a patient with house medical staff, waiting for test results, waiting for changes in the patient’s condition, waiting for end of a therapy session, or waiting for use of facilities cannot be billed as prolonged services.5 This is in direct opposition to its policy for C/CC services, and makes prolonged care services inefficient.

Medicare also identifies “threshold” time (see Table 2). The total physician visit time must exceed the time requirements associated with the “primary” codes by a 30-minute threshold (e.g. 99221+99356=30 minutes+30 minutes=60 minutes threshold time). The physician must document the total face-to-face time spent in separate notes throughout the day or, more realistically, in one cumulative note.

When two providers from the same group and same specialty perform services on the same date (e.g. physician A saw the patient during morning rounds, and physician B spoke with the patient/family in the afternoon), only one physician can report the cumulative service.6 As always, query payors for coverage, because some non-Medicare insurers do not recognize these codes.

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is also on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1B. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare National Coverage Determinations Manual: Chapter 1, Section 70.1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/ncd103c1_Part1.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.15.1C. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

- Abraham M, Ahlman J, Anderson C, Boudreau A, Connelly J. Current Procedural Terminology 2012 Professional Edition. Chicago: American Medical Association Press; 2011:7-21.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Jan. 8, 2012.

Hospitalists Provide Leadership as Unit Medical Directors

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

A project to formalize “local leadership models”—partnering leadership teams comprising a hospitalist and a nurse manager on each participating unit—at the University of Michigan Health System helped to redefine the role of unit medical director and led to allocating sufficient time (15% to 20% of an FTE) for hospitalists to fill that role. The process also led to a joint role description for the physician and nurse leaders.

“In our organization, we had the medical director concept in place previously, but things were missing, with no direct accountability, no dedicated effort, and lack of clarity on reporting,” explains hospitalist Christopher Kim, MD, MBA, lead author of an article about the project published in the American Journal of Medical Quality.1 “We learned from other organizations, and one of the first things we learned was to make sure we hired the right person as medical director. We need an energetic, enthusiastic physician who can reach out to nurses and bridge gaps in communication and coordination of care.”

The clinical partnership model was piloted on five units—four adult and one pediatric—and has since been adopted by eight others. The physician/nurse leaders work on such issues as improving care transitions, reducing pressure ulcers and catheter-related urinary tract infections, developing multi-disciplinary rounding on the units, and sharing quality data with staff.

“Take UTIs or pressure ulcers; we’re all familiar with recommended practice, but how it gets played out on the units varies. If team leaders understand this, they can champion the processes and

create an educational push for them,” Dr. Kim says. “Those organizations that have done this well cite higher staff satisfaction as a result.”

Study results show that the initial five units were “among the highest-performing units in our facility on satisfaction,” he adds. “It’s an exciting opportunity to bring change processes necessary to build a local clinical care environment that will improve the overall experience of the patient.”

Reference

First Set of CMS Advisors Includes Hospitalists

In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 73 professionals as the initial set of advisors for its Innovation Center (http://innovations.cms.gov/). The advisors include 37 physicians, as well as some nurses and health administrators. Each advisor will receive six months of intensive training in quality-improvement (QI) methods and health systems research in order to deepen skills that could help drive improvements in patient care across the system.

Each of the 920 applicants named a project they wanted to pursue at their home institution; many already are involved in quality activities, says Fran Griffin, the program coordinator. CMS hopes that advisors will become “change agents” and mentors to others within their organizations and communities, she adds. “But we are clear that we are not funding research. We want people to come and be educated, and we want to know if they are learning these skills and applying what they learn in real time,” Griffin says.

Advisors will participate in four in-person meetings, the first of which was held in January, as well as four conference calls or webinars each month. The Innovation Center aims to eventually bring 200 advisors on board, with a second cycle of applications and selections expected later this spring.Funded by the Affordable Care Act, the program provides a stipend of up to $20,000 to the advisor’s institution to free up 10 hours a week for training and to complete their projects. Of the initial set of advisors, at least two are hospitalists: Stephen Liu, MD, MPH, FACPM, of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Hanover, N.H., and Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, director of the clinical research program at Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta. Topics pursued by the advisors include unnecessary hospital readmissions, improving care transitions, chronic disease management, and the development of medical homes outside the hospital.

Dr. Liu’s proposed project is to re-engineer and improve geriatric inpatient stays to help preserve patients’ functional status. “Overall, I had a great experience at the first meeting of the advisors,” Dr. Liu says. “It was great to discuss the challenges and opportunities for improvement at each of the different settings represented, and to learn that many of the challenges are similar to those we face in the inpatient setting, such as communication with primary-care providers, transitions of care, and avoiding complications from hospitalizations.”

For more information or to receive email updates, visit www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives.

In January, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 73 professionals as the initial set of advisors for its Innovation Center (http://innovations.cms.gov/). The advisors include 37 physicians, as well as some nurses and health administrators. Each advisor will receive six months of intensive training in quality-improvement (QI) methods and health systems research in order to deepen skills that could help drive improvements in patient care across the system.

Each of the 920 applicants named a project they wanted to pursue at their home institution; many already are involved in quality activities, says Fran Griffin, the program coordinator. CMS hopes that advisors will become “change agents” and mentors to others within their organizations and communities, she adds. “But we are clear that we are not funding research. We want people to come and be educated, and we want to know if they are learning these skills and applying what they learn in real time,” Griffin says.