User login

Blood Cultures in Nonpneumonia Illness

In 2002, based on consensus practice guidelines,[1] the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) announced a core measure mandating the collection of routine blood cultures in the emergency department (ED) for all patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) to benchmark the quality of hospital care. However, due to the limited utility and false‐positive results of routine blood cultures,[2, 3, 4, 5, 6] performance measures and practice guidelines were modified in 2005 and 2007, respectively, to recommend routine collection in only the sickest patients with CAP.[2, 7] Despite recommendations for a more narrow set of indications, the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with CAP continued to increase.[8]

Distinguishing CAP from other respiratory illnesses may be challenging. Among patients presenting to the ED with an acute respiratory illness, only a minority of patients (10%30%) are diagnosed with pneumonia.[9] Therefore, the harms and costs of inappropriate diagnostic tests for CAP may be further magnified if applied to a larger population of patients who present to the ED with similar clinical signs and symptoms as pneumonia. Using a national sample of ED visits, we examined whether there was a similar increase in the frequency of blood culture collection among patients who were hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia.

METHOD

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We performed a cross‐sectional analysis using data from the 2002 to 2010 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS), a probability sample of visits to EDs of noninstitutional general and short‐stay hospitals in the United States, excluding federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals.[10] The NHAMCS data are derived through multistage sampling and estimation procedures that produce unbiased national estimates.[11] Further details regarding the sampling and estimation procedures can be found on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.[10, 11] Years 2005 and 2006 are omitted because NHAMCS did not collect blood culture use during this period. We included all visits by patients aged 18 years or older who were subsequently hospitalized.

Measurements

Trained hospital staff collected data with oversight from US Census Bureau field representatives.[12] Blood culture collection during the visit was recorded as a checkbox on the NHAMCS data collection form if at least 1 culture was ordered or collected in the ED. Visits for conditions that may resemble pneumonia were defined as visits with a respiratory symptom listed for at least 1 of the 3 reason for visit fields, excluding those visits admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes 481.xx‐486.xx). The reason for visit field captures the patient's complaints, symptoms, or other reasons for the visit in the patient's own words. CAP was defined by having 1 of the 3 ED provider's diagnosis fields coded as pneumonia (ICD‐9‐CM 481486), excluding patients with suspected hospital‐acquired pneumonia (nursing home or institutionalized resident, seen in the ED in the past 72 hours, or discharged from any hospital within the past 7 days) or those with a follow‐up visit for the same problem.[8]

Data Analysis

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design, including weights, to reflect national estimates. To examine for potential spillover effects of the blood culture recommendations for CAP on other conditions that may present similarly, we used linear regression to examine the trend in collecting blood cultures in patients admitted to the hospital with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness.

The data were analyzed using Stata statistical software, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

RESULTS

This study included 4854 ED visits, representing approximately 17 million visits by adult patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness. The most common primary ED provider's diagnoses for these visits included heart failure (15.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12.6%), chest pain (11.9%), respiratory insufficiency or failure (8.8%), and asthma (5.5%). The characteristics of these visits are shown in Table 1.

| Years 20022004, Weighted % (Unweighted N=2,175)b | Years 20072008, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,346)b | Years 20092010, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,333)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Blood culture collected | 9.8 | 14.4 | 19.9 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age 65 years | 56.9 | 55.1 | 50.9 |

| Female | 54.0 | 57.5 | 51.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 71.5c | 69.5 | 67.2 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 17.1c | 20.8 | 22.2 |

| Other | 11.3c | 9.7 | 10.6 |

| Primary payer | |||

| Private insurance | 23.4 | 19.1 | 19.1 |

| Medicare | 55.2 | 58.0 | 54.2 |

| Medicaid | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.8 |

| Other/unknown | 11.4 | 12.4 | 13.0 |

| Visit characteristics | |||

| Disposition status | |||

| Non‐ICU | 86.8 | 85.5 | 83.3 |

| ICU | 13.2 | 14.5 | 16.7 |

| Fever (38.0C) | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.8 |

| Hypoxia (90%)d | 11.5 | 10.9 | |

| Emergent status by triage | 46.1 | 44.5 | 35.8 |

| Administered antibiotics | 19.6 | 24.6 | 24.8 |

| Tests/services ordered in ED | |||

| 05 | 29.9 | 29.1 | 22.3 |

| 610 | 43.5 | 58.3 | 56.1 |

| >10 | 26.6 | 12.6 | 21.6 |

| ED characteristics | |||

| Region | |||

| West | 16.6 | 18.2 | 15.8 |

| Midwest | 27.1 | 25.2 | 22.8 |

| South | 32.8 | 36.4 | 38.6 |

| Northeast | 23.5 | 20.2 | 22.7 |

| Hospital owner | |||

| Nonprofit | 80.6 | 84.6 | 80.7 |

| Government | 12.1 | 6.4 | 13.0 |

| Private | 7.4 | 9.0 | 6.3 |

The proportion of blood cultures collected in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness increased from 9.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.1%‐13.5%) in 2002 to 20.4% (95% CI: 16.1%‐25.6%) in 2010 (P0.001 for the trend). This observed increase paralleled the increase in the frequency of culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP (P=0.12 for the difference in temporal trends). The estimated absolute number of visits for respiratory symptoms due a nonpneumonia illness with a blood culture collected increased from 211,000 (95% CI: 126,000296,000) in 2002 to 526,000 (95% CI: 361,000692,000) in 2010, which was similar in magnitude to the estimated number of visits for CAP with a culture collected (Table 2).

| National Weighted Estimates (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Condition | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P Valueb |

| Respiratory symptomc | ||||||||

| % | 9.9 (7.113.5) | 9.2 (6.912.2) | 10.6 (7.914.1) | 13.5 (10.117.8) | 15.2 (12.118.8) | 19.4 (15.923.5) | 20.4 (16.125.6) | 0.001 |

| No., thousands | 211 (126296) | 229 (140319) | 212 (140285) | 287 (191382) | 418 (288548) | 486 (344627) | 526 (361692) | |

| CAP | ||||||||

| % | 29.4 (21.938.3) | 34.2 (25.943.6) | 38.4 (31.045.4) | 45.7 (35.456.4) | 44.1 (34.154.6) | 46.7 (37.456.1) | 51.1 (41.860.3) | 0.027 |

| No., thousands | 155 (100210) | 287 (177397) | 276 (192361) | 277 (173381) | 361 (255467) | 350 (237464) | 428 (283574) | |

DISCUSSION

In this national study of ED visits, we found that the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia continued to increase from 2002 to 2010 in a parallel fashion to the trend observed for patients hospitalized with CAP. Our findings suggest that the heightened attention of collecting blood cultures for suspected pneumonia had unintended consequences, which led to an increase in the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with conditions that mimic pneumonia in the ED.

There can be a great deal of diagnostic uncertainty when treating patients in the ED who present with acute respiratory symptoms. Unfortunately, the initial history and physical exam are often insufficient to effectively rule in CAP.[13] Furthermore, the challenge of diagnosing pneumonia is amplified in the subset of patients who present with evolving, atypical, or occult disease. Faced with this diagnostic uncertainty, ED providers may feel pressured to comply with performance measures for CAP, promoting the overuse of inappropriate diagnostic tests and treatments. For instance, efforts to comply with early antibiotic administration in patients with CAP have led to an increase in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients with a diagnosis other than CAP.[14] Due to concerns for these unintended consequences, the core measure for early antibiotic administration was effectively retired in 2012.

Although a smaller percentage of ED visits for respiratory symptoms had a blood culture collected compared to CAP visits, there was a similar absolute number of visits with a blood culture collected during the study period. While a fraction of these patients may present with an infectious etiology aside from pneumonia, the majority of these cases likely represent situations where blood cultures add little diagnostic value at the expense of potentially longer hospital stays and broad spectrum antimicrobial use due to false‐positive results,[5, 15] as well as higher costs incurred by the test itself.[15, 16]

Although recommendations for routine culture collection for all patients hospitalized with CAP have been revised, the JCAHO/CMS core measure (PN‐3b) announced in 2002 mandates that if a culture is collected in the ED, it should be collected prior to antibiotic administration. Due to inherent uncertainty and challenges in making a timely diagnosis of pneumonia, this measure may encourage providers to reflexively order cultures in all patients presenting with respiratory symptoms in whom antibiotic administration is anticipated. The observed increasing trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness should prompt JCAHO and CMS to reevaluate the risks and benefits of this core measure, with consideration of eliminating it altogether to discourage overuse in this population.

Our study had certain limitations. First, the omission of 2005 and 2006 data prohibited an evaluation of whether culture rates slowed down among patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness after revisions in recommendations for obtaining cultures in patients with CAP. Second, there may have been misclassification of culture collection due to errors in chart abstraction. However, abstraction errors in the NHAMCS typically result in undercoding.[17] Therefore, our findings likely underestimate the magnitude and frequency of culture collection in this population.

In conclusion, collecting blood cultures in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness has increased in a parallel fashion compared to the trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP from 2002 to 2010. This suggests an important potential unintended consequence of blood culture recommendations for CAP on patients who present with conditions that resemble pneumonia. More attention to the judicious use of blood cultures in these patients to reduce harm and costs is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Disclosures: Dr. Makam's work on this project was completed while he was a Primary Care Research Fellow at the University of California San Francisco, funded by an NRSA training grant (T32HP19025‐07‐00). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , , . Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):347–382.

- , , , et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27–S72.

- , , , , . The contribution of blood cultures to the clinical management of adult patients admitted to the hospital with community‐acquired pneumonia: a prospective observational study. Chest. 2003;123(4):1142–1150.

- , , , , , . Do emergency department blood cultures change practice in patients with pneumonia? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):393–400.

- , , , . Predicting bacteremia in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):342–347.

- , . The influence of the severity of community‐acquired pneumonia on the usefulness of blood cultures. Respir Med. 2001;95(1):78–82.

- , . The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services community‐acquired pneumonia initiative: what went wrong? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):409–411.

- , , . Blood culture use in the emergency department in patients hospitalized for community‐acquired pneumonia [published online ahead of print March 10, 2014]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13808.

- , , , et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(9):664–670.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS scope and sample design. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm#nhamcs_scope. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS estimation procedures. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_estimation_procedures.htm#nhamcs_procedures. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- , , , et al. NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):549–551.

- , , . Does this patient have community‐acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1440–1445.

- , , , . Misdiagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics: side effects of the 4‐h antibiotic administration rule. Chest. 2007;131(6):1865–1869.

- , , . Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results. JAMA. 1991;265(3):365–369.

- , . Analysis of strategies to improve cost effectiveness of blood cultures. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(5):272–276.

- . NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):722–725.

In 2002, based on consensus practice guidelines,[1] the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) announced a core measure mandating the collection of routine blood cultures in the emergency department (ED) for all patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) to benchmark the quality of hospital care. However, due to the limited utility and false‐positive results of routine blood cultures,[2, 3, 4, 5, 6] performance measures and practice guidelines were modified in 2005 and 2007, respectively, to recommend routine collection in only the sickest patients with CAP.[2, 7] Despite recommendations for a more narrow set of indications, the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with CAP continued to increase.[8]

Distinguishing CAP from other respiratory illnesses may be challenging. Among patients presenting to the ED with an acute respiratory illness, only a minority of patients (10%30%) are diagnosed with pneumonia.[9] Therefore, the harms and costs of inappropriate diagnostic tests for CAP may be further magnified if applied to a larger population of patients who present to the ED with similar clinical signs and symptoms as pneumonia. Using a national sample of ED visits, we examined whether there was a similar increase in the frequency of blood culture collection among patients who were hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia.

METHOD

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We performed a cross‐sectional analysis using data from the 2002 to 2010 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS), a probability sample of visits to EDs of noninstitutional general and short‐stay hospitals in the United States, excluding federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals.[10] The NHAMCS data are derived through multistage sampling and estimation procedures that produce unbiased national estimates.[11] Further details regarding the sampling and estimation procedures can be found on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.[10, 11] Years 2005 and 2006 are omitted because NHAMCS did not collect blood culture use during this period. We included all visits by patients aged 18 years or older who were subsequently hospitalized.

Measurements

Trained hospital staff collected data with oversight from US Census Bureau field representatives.[12] Blood culture collection during the visit was recorded as a checkbox on the NHAMCS data collection form if at least 1 culture was ordered or collected in the ED. Visits for conditions that may resemble pneumonia were defined as visits with a respiratory symptom listed for at least 1 of the 3 reason for visit fields, excluding those visits admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes 481.xx‐486.xx). The reason for visit field captures the patient's complaints, symptoms, or other reasons for the visit in the patient's own words. CAP was defined by having 1 of the 3 ED provider's diagnosis fields coded as pneumonia (ICD‐9‐CM 481486), excluding patients with suspected hospital‐acquired pneumonia (nursing home or institutionalized resident, seen in the ED in the past 72 hours, or discharged from any hospital within the past 7 days) or those with a follow‐up visit for the same problem.[8]

Data Analysis

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design, including weights, to reflect national estimates. To examine for potential spillover effects of the blood culture recommendations for CAP on other conditions that may present similarly, we used linear regression to examine the trend in collecting blood cultures in patients admitted to the hospital with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness.

The data were analyzed using Stata statistical software, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

RESULTS

This study included 4854 ED visits, representing approximately 17 million visits by adult patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness. The most common primary ED provider's diagnoses for these visits included heart failure (15.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12.6%), chest pain (11.9%), respiratory insufficiency or failure (8.8%), and asthma (5.5%). The characteristics of these visits are shown in Table 1.

| Years 20022004, Weighted % (Unweighted N=2,175)b | Years 20072008, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,346)b | Years 20092010, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,333)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Blood culture collected | 9.8 | 14.4 | 19.9 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age 65 years | 56.9 | 55.1 | 50.9 |

| Female | 54.0 | 57.5 | 51.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 71.5c | 69.5 | 67.2 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 17.1c | 20.8 | 22.2 |

| Other | 11.3c | 9.7 | 10.6 |

| Primary payer | |||

| Private insurance | 23.4 | 19.1 | 19.1 |

| Medicare | 55.2 | 58.0 | 54.2 |

| Medicaid | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.8 |

| Other/unknown | 11.4 | 12.4 | 13.0 |

| Visit characteristics | |||

| Disposition status | |||

| Non‐ICU | 86.8 | 85.5 | 83.3 |

| ICU | 13.2 | 14.5 | 16.7 |

| Fever (38.0C) | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.8 |

| Hypoxia (90%)d | 11.5 | 10.9 | |

| Emergent status by triage | 46.1 | 44.5 | 35.8 |

| Administered antibiotics | 19.6 | 24.6 | 24.8 |

| Tests/services ordered in ED | |||

| 05 | 29.9 | 29.1 | 22.3 |

| 610 | 43.5 | 58.3 | 56.1 |

| >10 | 26.6 | 12.6 | 21.6 |

| ED characteristics | |||

| Region | |||

| West | 16.6 | 18.2 | 15.8 |

| Midwest | 27.1 | 25.2 | 22.8 |

| South | 32.8 | 36.4 | 38.6 |

| Northeast | 23.5 | 20.2 | 22.7 |

| Hospital owner | |||

| Nonprofit | 80.6 | 84.6 | 80.7 |

| Government | 12.1 | 6.4 | 13.0 |

| Private | 7.4 | 9.0 | 6.3 |

The proportion of blood cultures collected in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness increased from 9.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.1%‐13.5%) in 2002 to 20.4% (95% CI: 16.1%‐25.6%) in 2010 (P0.001 for the trend). This observed increase paralleled the increase in the frequency of culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP (P=0.12 for the difference in temporal trends). The estimated absolute number of visits for respiratory symptoms due a nonpneumonia illness with a blood culture collected increased from 211,000 (95% CI: 126,000296,000) in 2002 to 526,000 (95% CI: 361,000692,000) in 2010, which was similar in magnitude to the estimated number of visits for CAP with a culture collected (Table 2).

| National Weighted Estimates (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Condition | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P Valueb |

| Respiratory symptomc | ||||||||

| % | 9.9 (7.113.5) | 9.2 (6.912.2) | 10.6 (7.914.1) | 13.5 (10.117.8) | 15.2 (12.118.8) | 19.4 (15.923.5) | 20.4 (16.125.6) | 0.001 |

| No., thousands | 211 (126296) | 229 (140319) | 212 (140285) | 287 (191382) | 418 (288548) | 486 (344627) | 526 (361692) | |

| CAP | ||||||||

| % | 29.4 (21.938.3) | 34.2 (25.943.6) | 38.4 (31.045.4) | 45.7 (35.456.4) | 44.1 (34.154.6) | 46.7 (37.456.1) | 51.1 (41.860.3) | 0.027 |

| No., thousands | 155 (100210) | 287 (177397) | 276 (192361) | 277 (173381) | 361 (255467) | 350 (237464) | 428 (283574) | |

DISCUSSION

In this national study of ED visits, we found that the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia continued to increase from 2002 to 2010 in a parallel fashion to the trend observed for patients hospitalized with CAP. Our findings suggest that the heightened attention of collecting blood cultures for suspected pneumonia had unintended consequences, which led to an increase in the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with conditions that mimic pneumonia in the ED.

There can be a great deal of diagnostic uncertainty when treating patients in the ED who present with acute respiratory symptoms. Unfortunately, the initial history and physical exam are often insufficient to effectively rule in CAP.[13] Furthermore, the challenge of diagnosing pneumonia is amplified in the subset of patients who present with evolving, atypical, or occult disease. Faced with this diagnostic uncertainty, ED providers may feel pressured to comply with performance measures for CAP, promoting the overuse of inappropriate diagnostic tests and treatments. For instance, efforts to comply with early antibiotic administration in patients with CAP have led to an increase in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients with a diagnosis other than CAP.[14] Due to concerns for these unintended consequences, the core measure for early antibiotic administration was effectively retired in 2012.

Although a smaller percentage of ED visits for respiratory symptoms had a blood culture collected compared to CAP visits, there was a similar absolute number of visits with a blood culture collected during the study period. While a fraction of these patients may present with an infectious etiology aside from pneumonia, the majority of these cases likely represent situations where blood cultures add little diagnostic value at the expense of potentially longer hospital stays and broad spectrum antimicrobial use due to false‐positive results,[5, 15] as well as higher costs incurred by the test itself.[15, 16]

Although recommendations for routine culture collection for all patients hospitalized with CAP have been revised, the JCAHO/CMS core measure (PN‐3b) announced in 2002 mandates that if a culture is collected in the ED, it should be collected prior to antibiotic administration. Due to inherent uncertainty and challenges in making a timely diagnosis of pneumonia, this measure may encourage providers to reflexively order cultures in all patients presenting with respiratory symptoms in whom antibiotic administration is anticipated. The observed increasing trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness should prompt JCAHO and CMS to reevaluate the risks and benefits of this core measure, with consideration of eliminating it altogether to discourage overuse in this population.

Our study had certain limitations. First, the omission of 2005 and 2006 data prohibited an evaluation of whether culture rates slowed down among patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness after revisions in recommendations for obtaining cultures in patients with CAP. Second, there may have been misclassification of culture collection due to errors in chart abstraction. However, abstraction errors in the NHAMCS typically result in undercoding.[17] Therefore, our findings likely underestimate the magnitude and frequency of culture collection in this population.

In conclusion, collecting blood cultures in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness has increased in a parallel fashion compared to the trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP from 2002 to 2010. This suggests an important potential unintended consequence of blood culture recommendations for CAP on patients who present with conditions that resemble pneumonia. More attention to the judicious use of blood cultures in these patients to reduce harm and costs is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Disclosures: Dr. Makam's work on this project was completed while he was a Primary Care Research Fellow at the University of California San Francisco, funded by an NRSA training grant (T32HP19025‐07‐00). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

In 2002, based on consensus practice guidelines,[1] the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) announced a core measure mandating the collection of routine blood cultures in the emergency department (ED) for all patients hospitalized with community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) to benchmark the quality of hospital care. However, due to the limited utility and false‐positive results of routine blood cultures,[2, 3, 4, 5, 6] performance measures and practice guidelines were modified in 2005 and 2007, respectively, to recommend routine collection in only the sickest patients with CAP.[2, 7] Despite recommendations for a more narrow set of indications, the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with CAP continued to increase.[8]

Distinguishing CAP from other respiratory illnesses may be challenging. Among patients presenting to the ED with an acute respiratory illness, only a minority of patients (10%30%) are diagnosed with pneumonia.[9] Therefore, the harms and costs of inappropriate diagnostic tests for CAP may be further magnified if applied to a larger population of patients who present to the ED with similar clinical signs and symptoms as pneumonia. Using a national sample of ED visits, we examined whether there was a similar increase in the frequency of blood culture collection among patients who were hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia.

METHOD

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We performed a cross‐sectional analysis using data from the 2002 to 2010 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NHAMCS), a probability sample of visits to EDs of noninstitutional general and short‐stay hospitals in the United States, excluding federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals.[10] The NHAMCS data are derived through multistage sampling and estimation procedures that produce unbiased national estimates.[11] Further details regarding the sampling and estimation procedures can be found on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.[10, 11] Years 2005 and 2006 are omitted because NHAMCS did not collect blood culture use during this period. We included all visits by patients aged 18 years or older who were subsequently hospitalized.

Measurements

Trained hospital staff collected data with oversight from US Census Bureau field representatives.[12] Blood culture collection during the visit was recorded as a checkbox on the NHAMCS data collection form if at least 1 culture was ordered or collected in the ED. Visits for conditions that may resemble pneumonia were defined as visits with a respiratory symptom listed for at least 1 of the 3 reason for visit fields, excluding those visits admitted with a diagnosis of pneumonia (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes 481.xx‐486.xx). The reason for visit field captures the patient's complaints, symptoms, or other reasons for the visit in the patient's own words. CAP was defined by having 1 of the 3 ED provider's diagnosis fields coded as pneumonia (ICD‐9‐CM 481486), excluding patients with suspected hospital‐acquired pneumonia (nursing home or institutionalized resident, seen in the ED in the past 72 hours, or discharged from any hospital within the past 7 days) or those with a follow‐up visit for the same problem.[8]

Data Analysis

All analyses accounted for the complex survey design, including weights, to reflect national estimates. To examine for potential spillover effects of the blood culture recommendations for CAP on other conditions that may present similarly, we used linear regression to examine the trend in collecting blood cultures in patients admitted to the hospital with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness.

The data were analyzed using Stata statistical software, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). This study was exempt from review by the institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

RESULTS

This study included 4854 ED visits, representing approximately 17 million visits by adult patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness. The most common primary ED provider's diagnoses for these visits included heart failure (15.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (12.6%), chest pain (11.9%), respiratory insufficiency or failure (8.8%), and asthma (5.5%). The characteristics of these visits are shown in Table 1.

| Years 20022004, Weighted % (Unweighted N=2,175)b | Years 20072008, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,346)b | Years 20092010, Weighted % (Unweighted N=1,333)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Blood culture collected | 9.8 | 14.4 | 19.9 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age 65 years | 56.9 | 55.1 | 50.9 |

| Female | 54.0 | 57.5 | 51.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 71.5c | 69.5 | 67.2 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 17.1c | 20.8 | 22.2 |

| Other | 11.3c | 9.7 | 10.6 |

| Primary payer | |||

| Private insurance | 23.4 | 19.1 | 19.1 |

| Medicare | 55.2 | 58.0 | 54.2 |

| Medicaid | 10.0 | 10.5 | 13.8 |

| Other/unknown | 11.4 | 12.4 | 13.0 |

| Visit characteristics | |||

| Disposition status | |||

| Non‐ICU | 86.8 | 85.5 | 83.3 |

| ICU | 13.2 | 14.5 | 16.7 |

| Fever (38.0C) | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.8 |

| Hypoxia (90%)d | 11.5 | 10.9 | |

| Emergent status by triage | 46.1 | 44.5 | 35.8 |

| Administered antibiotics | 19.6 | 24.6 | 24.8 |

| Tests/services ordered in ED | |||

| 05 | 29.9 | 29.1 | 22.3 |

| 610 | 43.5 | 58.3 | 56.1 |

| >10 | 26.6 | 12.6 | 21.6 |

| ED characteristics | |||

| Region | |||

| West | 16.6 | 18.2 | 15.8 |

| Midwest | 27.1 | 25.2 | 22.8 |

| South | 32.8 | 36.4 | 38.6 |

| Northeast | 23.5 | 20.2 | 22.7 |

| Hospital owner | |||

| Nonprofit | 80.6 | 84.6 | 80.7 |

| Government | 12.1 | 6.4 | 13.0 |

| Private | 7.4 | 9.0 | 6.3 |

The proportion of blood cultures collected in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness increased from 9.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.1%‐13.5%) in 2002 to 20.4% (95% CI: 16.1%‐25.6%) in 2010 (P0.001 for the trend). This observed increase paralleled the increase in the frequency of culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP (P=0.12 for the difference in temporal trends). The estimated absolute number of visits for respiratory symptoms due a nonpneumonia illness with a blood culture collected increased from 211,000 (95% CI: 126,000296,000) in 2002 to 526,000 (95% CI: 361,000692,000) in 2010, which was similar in magnitude to the estimated number of visits for CAP with a culture collected (Table 2).

| National Weighted Estimates (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Condition | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | P Valueb |

| Respiratory symptomc | ||||||||

| % | 9.9 (7.113.5) | 9.2 (6.912.2) | 10.6 (7.914.1) | 13.5 (10.117.8) | 15.2 (12.118.8) | 19.4 (15.923.5) | 20.4 (16.125.6) | 0.001 |

| No., thousands | 211 (126296) | 229 (140319) | 212 (140285) | 287 (191382) | 418 (288548) | 486 (344627) | 526 (361692) | |

| CAP | ||||||||

| % | 29.4 (21.938.3) | 34.2 (25.943.6) | 38.4 (31.045.4) | 45.7 (35.456.4) | 44.1 (34.154.6) | 46.7 (37.456.1) | 51.1 (41.860.3) | 0.027 |

| No., thousands | 155 (100210) | 287 (177397) | 276 (192361) | 277 (173381) | 361 (255467) | 350 (237464) | 428 (283574) | |

DISCUSSION

In this national study of ED visits, we found that the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to an illness other than pneumonia continued to increase from 2002 to 2010 in a parallel fashion to the trend observed for patients hospitalized with CAP. Our findings suggest that the heightened attention of collecting blood cultures for suspected pneumonia had unintended consequences, which led to an increase in the collection of blood cultures in patients hospitalized with conditions that mimic pneumonia in the ED.

There can be a great deal of diagnostic uncertainty when treating patients in the ED who present with acute respiratory symptoms. Unfortunately, the initial history and physical exam are often insufficient to effectively rule in CAP.[13] Furthermore, the challenge of diagnosing pneumonia is amplified in the subset of patients who present with evolving, atypical, or occult disease. Faced with this diagnostic uncertainty, ED providers may feel pressured to comply with performance measures for CAP, promoting the overuse of inappropriate diagnostic tests and treatments. For instance, efforts to comply with early antibiotic administration in patients with CAP have led to an increase in unnecessary antibiotic use among patients with a diagnosis other than CAP.[14] Due to concerns for these unintended consequences, the core measure for early antibiotic administration was effectively retired in 2012.

Although a smaller percentage of ED visits for respiratory symptoms had a blood culture collected compared to CAP visits, there was a similar absolute number of visits with a blood culture collected during the study period. While a fraction of these patients may present with an infectious etiology aside from pneumonia, the majority of these cases likely represent situations where blood cultures add little diagnostic value at the expense of potentially longer hospital stays and broad spectrum antimicrobial use due to false‐positive results,[5, 15] as well as higher costs incurred by the test itself.[15, 16]

Although recommendations for routine culture collection for all patients hospitalized with CAP have been revised, the JCAHO/CMS core measure (PN‐3b) announced in 2002 mandates that if a culture is collected in the ED, it should be collected prior to antibiotic administration. Due to inherent uncertainty and challenges in making a timely diagnosis of pneumonia, this measure may encourage providers to reflexively order cultures in all patients presenting with respiratory symptoms in whom antibiotic administration is anticipated. The observed increasing trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness should prompt JCAHO and CMS to reevaluate the risks and benefits of this core measure, with consideration of eliminating it altogether to discourage overuse in this population.

Our study had certain limitations. First, the omission of 2005 and 2006 data prohibited an evaluation of whether culture rates slowed down among patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness after revisions in recommendations for obtaining cultures in patients with CAP. Second, there may have been misclassification of culture collection due to errors in chart abstraction. However, abstraction errors in the NHAMCS typically result in undercoding.[17] Therefore, our findings likely underestimate the magnitude and frequency of culture collection in this population.

In conclusion, collecting blood cultures in the ED for patients hospitalized with respiratory symptoms due to a nonpneumonia illness has increased in a parallel fashion compared to the trend in culture collection in patients hospitalized with CAP from 2002 to 2010. This suggests an important potential unintended consequence of blood culture recommendations for CAP on patients who present with conditions that resemble pneumonia. More attention to the judicious use of blood cultures in these patients to reduce harm and costs is needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Disclosures: Dr. Makam's work on this project was completed while he was a Primary Care Research Fellow at the University of California San Francisco, funded by an NRSA training grant (T32HP19025‐07‐00). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , , . Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):347–382.

- , , , et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27–S72.

- , , , , . The contribution of blood cultures to the clinical management of adult patients admitted to the hospital with community‐acquired pneumonia: a prospective observational study. Chest. 2003;123(4):1142–1150.

- , , , , , . Do emergency department blood cultures change practice in patients with pneumonia? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):393–400.

- , , , . Predicting bacteremia in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):342–347.

- , . The influence of the severity of community‐acquired pneumonia on the usefulness of blood cultures. Respir Med. 2001;95(1):78–82.

- , . The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services community‐acquired pneumonia initiative: what went wrong? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):409–411.

- , , . Blood culture use in the emergency department in patients hospitalized for community‐acquired pneumonia [published online ahead of print March 10, 2014]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13808.

- , , , et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(9):664–670.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS scope and sample design. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm#nhamcs_scope. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS estimation procedures. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_estimation_procedures.htm#nhamcs_procedures. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- , , , et al. NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):549–551.

- , , . Does this patient have community‐acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1440–1445.

- , , , . Misdiagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics: side effects of the 4‐h antibiotic administration rule. Chest. 2007;131(6):1865–1869.

- , , . Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results. JAMA. 1991;265(3):365–369.

- , . Analysis of strategies to improve cost effectiveness of blood cultures. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(5):272–276.

- . NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):722–725.

- , , , , , . Practice guidelines for the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(2):347–382.

- , , , et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community‐acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 2):S27–S72.

- , , , , . The contribution of blood cultures to the clinical management of adult patients admitted to the hospital with community‐acquired pneumonia: a prospective observational study. Chest. 2003;123(4):1142–1150.

- , , , , , . Do emergency department blood cultures change practice in patients with pneumonia? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):393–400.

- , , , . Predicting bacteremia in patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):342–347.

- , . The influence of the severity of community‐acquired pneumonia on the usefulness of blood cultures. Respir Med. 2001;95(1):78–82.

- , . The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services community‐acquired pneumonia initiative: what went wrong? Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(5):409–411.

- , , . Blood culture use in the emergency department in patients hospitalized for community‐acquired pneumonia [published online ahead of print March 10, 2014]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13808.

- , , , et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(9):664–670.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS scope and sample design. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm#nhamcs_scope. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHAMCS estimation procedures. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_estimation_procedures.htm#nhamcs_procedures. Updated January 15, 2010. Accessed May 27, 2013.

- , , , et al. NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):549–551.

- , , . Does this patient have community‐acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination. JAMA. 1997;278(17):1440–1445.

- , , , . Misdiagnosis of community‐acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics: side effects of the 4‐h antibiotic administration rule. Chest. 2007;131(6):1865–1869.

- , , . Contaminant blood cultures and resource utilization. The true consequences of false‐positive results. JAMA. 1991;265(3):365–369.

- , . Analysis of strategies to improve cost effectiveness of blood cultures. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(5):272–276.

- . NHAMCS: does it hold up to scrutiny? Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):722–725.

The Skinny Podcast: Vitiligo research update, Dr. Rockoff on puzzling prescription rules, and the latest dermatology headlines

In this episode of our monthly dermatology podcast, we bring you an expert update on vitiligo research, a dose of humor from our columnist, Dr. Alan Rockoff, and the top news on edermatologynews.com.

In this episode of our monthly dermatology podcast, we bring you an expert update on vitiligo research, a dose of humor from our columnist, Dr. Alan Rockoff, and the top news on edermatologynews.com.

In this episode of our monthly dermatology podcast, we bring you an expert update on vitiligo research, a dose of humor from our columnist, Dr. Alan Rockoff, and the top news on edermatologynews.com.

CO2 laser works best for hypertrophic scars

PHOENIX – A fractional carbon dioxide laser at 10,600 nm was the only one of three laser treatments for hypertrophic scars that produced significant overall improvements in a comparison of data on 141 scars in 66 patients.

Less successful were treatments using a vascular KTP laser at 532 nm or a 1,550-nm nonablative fractional erbium glass laser.

"The only one that showed significant improvement compared with the control scar, adjusted for the baseline scar, was the fractional CO2 laser," Dr. Sigrid Blome-Eberwein said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The data came from three prospective controlled studies at one institution. The patients were burn survivors who had at least two scars of similar appearance and physiologic function in the same body area that were at least 6 months from wound healing. Patients underwent a series of at least three treatments at 4-week intervals on one or more scars, with a similar scar left untreated as the control scar.

Subjective assessments of the scars showed statistically significant improvements in scores on the Vancouver Scar Scale with all three treatments compared with control scars, but fewer changes were seen in objective measurements of scar qualities. "Measurements of these improvements are really difficult to tackle. We tried to add some objective measurement instruments to our evaluations," reported Dr. Blome-Eberwein of Lehigh Valley Regional Burn Center, Allentown, Pa.

None of the treatments produced significant changes in elasticity as measured by the Cutometer device. "It’s really a complete mix of results in this value," she said.

The fractional erbium laser produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars, in thickness as measured by high-resolution ultrasound used to assess scar thickness (so that patients could avoid biopsies). The KTP laser also produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars: improved sensation as assessed by Semmes Weinstein monofilaments.

The CO2 laser, however, produced greater improvements in scar thickness and sensation, as well as significant improvements in erythema and pigment (both measured by spectrometry), compared with control scars. Measurements of pain and pruritus did not differ significantly between treated and control scars in any of the studies; pain levels tended to improve in both the treated and control areas and pruritus tended to remain steady.

The KTP laser caused blisters in some patients. The fractional CO2 and fractional erbium lasers produced minimal damage. Increased power was more likely to produce collateral damage and blisters, Dr. Blome-Eberwein said.

Any results were persistent and additive. Because penetration of these lasers is limited, multiple treatments are needed for thick scars, she noted.

Based on these findings and her experience at the burn center, Dr. Blome-Eberwein recommended treating scars that seem to turn hypertrophic early (within 4 weeks of wound healing) and frequently (every 3 weeks) with a nonablative fractional erbium glass laser or pulsed dye laser. The erbium glass laser does seem to prevent "some degree of hypertrophy early on," she said. Either of these early treatments may decrease hypertrophic activity and prevent hypertrophy with no dermal damage.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein said she treats hypertrophic scars 3-12 months after healing with fractional CO2 laser. Treating scar pigment remains a challenge, she added.

"In the future, there will be handheld devices" to treat scars at home "because a lot of people are affected by this problem," she said.

Most of the scars in the studies were from burns, with a few from trauma.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – A fractional carbon dioxide laser at 10,600 nm was the only one of three laser treatments for hypertrophic scars that produced significant overall improvements in a comparison of data on 141 scars in 66 patients.

Less successful were treatments using a vascular KTP laser at 532 nm or a 1,550-nm nonablative fractional erbium glass laser.

"The only one that showed significant improvement compared with the control scar, adjusted for the baseline scar, was the fractional CO2 laser," Dr. Sigrid Blome-Eberwein said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The data came from three prospective controlled studies at one institution. The patients were burn survivors who had at least two scars of similar appearance and physiologic function in the same body area that were at least 6 months from wound healing. Patients underwent a series of at least three treatments at 4-week intervals on one or more scars, with a similar scar left untreated as the control scar.

Subjective assessments of the scars showed statistically significant improvements in scores on the Vancouver Scar Scale with all three treatments compared with control scars, but fewer changes were seen in objective measurements of scar qualities. "Measurements of these improvements are really difficult to tackle. We tried to add some objective measurement instruments to our evaluations," reported Dr. Blome-Eberwein of Lehigh Valley Regional Burn Center, Allentown, Pa.

None of the treatments produced significant changes in elasticity as measured by the Cutometer device. "It’s really a complete mix of results in this value," she said.

The fractional erbium laser produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars, in thickness as measured by high-resolution ultrasound used to assess scar thickness (so that patients could avoid biopsies). The KTP laser also produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars: improved sensation as assessed by Semmes Weinstein monofilaments.

The CO2 laser, however, produced greater improvements in scar thickness and sensation, as well as significant improvements in erythema and pigment (both measured by spectrometry), compared with control scars. Measurements of pain and pruritus did not differ significantly between treated and control scars in any of the studies; pain levels tended to improve in both the treated and control areas and pruritus tended to remain steady.

The KTP laser caused blisters in some patients. The fractional CO2 and fractional erbium lasers produced minimal damage. Increased power was more likely to produce collateral damage and blisters, Dr. Blome-Eberwein said.

Any results were persistent and additive. Because penetration of these lasers is limited, multiple treatments are needed for thick scars, she noted.

Based on these findings and her experience at the burn center, Dr. Blome-Eberwein recommended treating scars that seem to turn hypertrophic early (within 4 weeks of wound healing) and frequently (every 3 weeks) with a nonablative fractional erbium glass laser or pulsed dye laser. The erbium glass laser does seem to prevent "some degree of hypertrophy early on," she said. Either of these early treatments may decrease hypertrophic activity and prevent hypertrophy with no dermal damage.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein said she treats hypertrophic scars 3-12 months after healing with fractional CO2 laser. Treating scar pigment remains a challenge, she added.

"In the future, there will be handheld devices" to treat scars at home "because a lot of people are affected by this problem," she said.

Most of the scars in the studies were from burns, with a few from trauma.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

PHOENIX – A fractional carbon dioxide laser at 10,600 nm was the only one of three laser treatments for hypertrophic scars that produced significant overall improvements in a comparison of data on 141 scars in 66 patients.

Less successful were treatments using a vascular KTP laser at 532 nm or a 1,550-nm nonablative fractional erbium glass laser.

"The only one that showed significant improvement compared with the control scar, adjusted for the baseline scar, was the fractional CO2 laser," Dr. Sigrid Blome-Eberwein said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

The data came from three prospective controlled studies at one institution. The patients were burn survivors who had at least two scars of similar appearance and physiologic function in the same body area that were at least 6 months from wound healing. Patients underwent a series of at least three treatments at 4-week intervals on one or more scars, with a similar scar left untreated as the control scar.

Subjective assessments of the scars showed statistically significant improvements in scores on the Vancouver Scar Scale with all three treatments compared with control scars, but fewer changes were seen in objective measurements of scar qualities. "Measurements of these improvements are really difficult to tackle. We tried to add some objective measurement instruments to our evaluations," reported Dr. Blome-Eberwein of Lehigh Valley Regional Burn Center, Allentown, Pa.

None of the treatments produced significant changes in elasticity as measured by the Cutometer device. "It’s really a complete mix of results in this value," she said.

The fractional erbium laser produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars, in thickness as measured by high-resolution ultrasound used to assess scar thickness (so that patients could avoid biopsies). The KTP laser also produced one statistically significant improvement, compared with control scars: improved sensation as assessed by Semmes Weinstein monofilaments.

The CO2 laser, however, produced greater improvements in scar thickness and sensation, as well as significant improvements in erythema and pigment (both measured by spectrometry), compared with control scars. Measurements of pain and pruritus did not differ significantly between treated and control scars in any of the studies; pain levels tended to improve in both the treated and control areas and pruritus tended to remain steady.

The KTP laser caused blisters in some patients. The fractional CO2 and fractional erbium lasers produced minimal damage. Increased power was more likely to produce collateral damage and blisters, Dr. Blome-Eberwein said.

Any results were persistent and additive. Because penetration of these lasers is limited, multiple treatments are needed for thick scars, she noted.

Based on these findings and her experience at the burn center, Dr. Blome-Eberwein recommended treating scars that seem to turn hypertrophic early (within 4 weeks of wound healing) and frequently (every 3 weeks) with a nonablative fractional erbium glass laser or pulsed dye laser. The erbium glass laser does seem to prevent "some degree of hypertrophy early on," she said. Either of these early treatments may decrease hypertrophic activity and prevent hypertrophy with no dermal damage.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein said she treats hypertrophic scars 3-12 months after healing with fractional CO2 laser. Treating scar pigment remains a challenge, she added.

"In the future, there will be handheld devices" to treat scars at home "because a lot of people are affected by this problem," she said.

Most of the scars in the studies were from burns, with a few from trauma.

Dr. Blome-Eberwein reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT LASER 2014

Major finding: The fractional CO2 laser significantly improved scar thickness, sensation, erythema, and pigment, compared with untreated scars. The KTP laser improved sensation and the erbium glass laser improved thickness in treated scars, compared with control scars.

Data source: An analysis of data from three prospective controlled studies of laser treatments in 66 patients with 141 scars.

Disclosures: Dr. Blome-Eberwein reported having no financial disclosures.

Explaining the link between Down syndrome and B-ALL

Credit: Aaron Logan

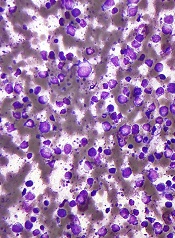

Investigators believe they’ve uncovered information that explains the connection between Down syndrome and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In a letter to Nature Genetics, the team described how they tracked the chain of events that links a chromosomal abnormality in Down syndrome to the cellular havoc that occurs in B-cell ALL.

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that the gene HMGN1 turns off the function of PRC2, which prompts B-cell proliferation.

“For 80 years, it hasn’t been clear why children with Down syndrome face a sharply elevated risk of ALL,” said the study’s lead author, Andrew Lane, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“Advances in technology—which make it possible to study blood cells and leukemias that model Down syndrome in the laboratory—have enabled us to make that link.”

To trace the link between Down syndrome and B-ALL, the investigators acquired a strain of mice that carry an extra copy of 31 genes found on chromosome 21. B cells from these mice were abnormal and grew uncontrollably, just as they do in B-ALL patients.

The team set out to characterize the pattern of gene activity that distinguishes these abnormal B cells from normal B cells. They found the chief difference was that, in the abnormal cells, PRC2 proteins did not function. Somehow, the loss of PRC2 was spurring the B cells to divide and proliferate before they were fully mature.

To confirm that a shutdown of PRC2 is critical to the formation of B-ALL in Down syndrome patients, the investigators focused on the genes controlled by PRC2. Using 2 sets of B-ALL cell samples—1 from patients with Down syndrome and 1 from patients without it—they measured the activity of thousands of different genes, looking for differences between the 2 sets.

About 100 genes were much more active in the Down syndrome group, and all of them were under the control of PRC2. When PRC2 is silenced, those 100 genes respond with a burst of activity, driving cell growth and division.

The investigators then wondered what gene or group of genes was stifling PRC2 in Down syndrome patients’ B cells. Using cells from the mouse models, the team systematically switched off each of the 31 genes to determine its effect on the cells. When they turned off HMGN1, the cells stopped growing and died.

“We concluded that the extra copy of HMGN1 is important for turning off PRC2, and that, in turn, increases the cell proliferation,” Dr Lane said. “This provides the long-sought-after molecular link between Down syndrome and the development of B-cell ALL.”

Although there are currently no drugs that target HMGN1, the investigators suggest HDAC inhibitors that switch on PRC2 could have an antileukemic effect in patients with Down syndrome. Work is under way to improve these drugs so they can be tested in preclinical experiments.

As other forms of B-ALL also have the same 100-gene signature as the one discovered for B-ALL associated with Down syndrome, agents that target PRC2 might be effective in those cancers as well, Dr Lane noted. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

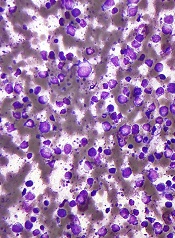

Investigators believe they’ve uncovered information that explains the connection between Down syndrome and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In a letter to Nature Genetics, the team described how they tracked the chain of events that links a chromosomal abnormality in Down syndrome to the cellular havoc that occurs in B-cell ALL.

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that the gene HMGN1 turns off the function of PRC2, which prompts B-cell proliferation.

“For 80 years, it hasn’t been clear why children with Down syndrome face a sharply elevated risk of ALL,” said the study’s lead author, Andrew Lane, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“Advances in technology—which make it possible to study blood cells and leukemias that model Down syndrome in the laboratory—have enabled us to make that link.”

To trace the link between Down syndrome and B-ALL, the investigators acquired a strain of mice that carry an extra copy of 31 genes found on chromosome 21. B cells from these mice were abnormal and grew uncontrollably, just as they do in B-ALL patients.

The team set out to characterize the pattern of gene activity that distinguishes these abnormal B cells from normal B cells. They found the chief difference was that, in the abnormal cells, PRC2 proteins did not function. Somehow, the loss of PRC2 was spurring the B cells to divide and proliferate before they were fully mature.

To confirm that a shutdown of PRC2 is critical to the formation of B-ALL in Down syndrome patients, the investigators focused on the genes controlled by PRC2. Using 2 sets of B-ALL cell samples—1 from patients with Down syndrome and 1 from patients without it—they measured the activity of thousands of different genes, looking for differences between the 2 sets.

About 100 genes were much more active in the Down syndrome group, and all of them were under the control of PRC2. When PRC2 is silenced, those 100 genes respond with a burst of activity, driving cell growth and division.

The investigators then wondered what gene or group of genes was stifling PRC2 in Down syndrome patients’ B cells. Using cells from the mouse models, the team systematically switched off each of the 31 genes to determine its effect on the cells. When they turned off HMGN1, the cells stopped growing and died.

“We concluded that the extra copy of HMGN1 is important for turning off PRC2, and that, in turn, increases the cell proliferation,” Dr Lane said. “This provides the long-sought-after molecular link between Down syndrome and the development of B-cell ALL.”

Although there are currently no drugs that target HMGN1, the investigators suggest HDAC inhibitors that switch on PRC2 could have an antileukemic effect in patients with Down syndrome. Work is under way to improve these drugs so they can be tested in preclinical experiments.

As other forms of B-ALL also have the same 100-gene signature as the one discovered for B-ALL associated with Down syndrome, agents that target PRC2 might be effective in those cancers as well, Dr Lane noted. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

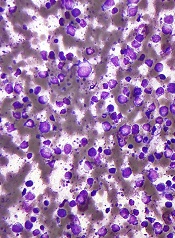

Investigators believe they’ve uncovered information that explains the connection between Down syndrome and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

In a letter to Nature Genetics, the team described how they tracked the chain of events that links a chromosomal abnormality in Down syndrome to the cellular havoc that occurs in B-cell ALL.

Experiments in mice and patient samples revealed that the gene HMGN1 turns off the function of PRC2, which prompts B-cell proliferation.

“For 80 years, it hasn’t been clear why children with Down syndrome face a sharply elevated risk of ALL,” said the study’s lead author, Andrew Lane, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“Advances in technology—which make it possible to study blood cells and leukemias that model Down syndrome in the laboratory—have enabled us to make that link.”

To trace the link between Down syndrome and B-ALL, the investigators acquired a strain of mice that carry an extra copy of 31 genes found on chromosome 21. B cells from these mice were abnormal and grew uncontrollably, just as they do in B-ALL patients.

The team set out to characterize the pattern of gene activity that distinguishes these abnormal B cells from normal B cells. They found the chief difference was that, in the abnormal cells, PRC2 proteins did not function. Somehow, the loss of PRC2 was spurring the B cells to divide and proliferate before they were fully mature.

To confirm that a shutdown of PRC2 is critical to the formation of B-ALL in Down syndrome patients, the investigators focused on the genes controlled by PRC2. Using 2 sets of B-ALL cell samples—1 from patients with Down syndrome and 1 from patients without it—they measured the activity of thousands of different genes, looking for differences between the 2 sets.

About 100 genes were much more active in the Down syndrome group, and all of them were under the control of PRC2. When PRC2 is silenced, those 100 genes respond with a burst of activity, driving cell growth and division.

The investigators then wondered what gene or group of genes was stifling PRC2 in Down syndrome patients’ B cells. Using cells from the mouse models, the team systematically switched off each of the 31 genes to determine its effect on the cells. When they turned off HMGN1, the cells stopped growing and died.

“We concluded that the extra copy of HMGN1 is important for turning off PRC2, and that, in turn, increases the cell proliferation,” Dr Lane said. “This provides the long-sought-after molecular link between Down syndrome and the development of B-cell ALL.”

Although there are currently no drugs that target HMGN1, the investigators suggest HDAC inhibitors that switch on PRC2 could have an antileukemic effect in patients with Down syndrome. Work is under way to improve these drugs so they can be tested in preclinical experiments.

As other forms of B-ALL also have the same 100-gene signature as the one discovered for B-ALL associated with Down syndrome, agents that target PRC2 might be effective in those cancers as well, Dr Lane noted. ![]()

Method speeds up analysis of RNA-seq data

Credit: Darren Baker

Researchers say they’ve developed a computational method that dramatically speeds up estimates of gene activity from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data.

With the new method, called Sailfish, estimates of gene expression that previously took hours can be completed in a few minutes.

And the researchers say the accuracy of Sailfish equals or exceeds that of previous methods.

The team described the Sailfish method in Nature Biotechnology.

They noted that gigantic repositories of RNA-seq data now exist, making it possible to re-analyze experiments in light of new discoveries.

“But 15 hours a pop really starts to add up, particularly if you want to look at 100 experiments,” said study author Carl Kingsford, PhD, of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

“With Sailfish, we can give researchers everything they got from previous methods, but faster.”

With previous methods, the RNA molecules from which read sequences originated could be identified and measured only by mapping the reads to their original positions in the larger molecules—a time-consuming process.

Dr Kingsford and his colleagues found this step can actually be eliminated. The team discovered they could allocate parts of the reads to different types of RNA molecules, much as if each read acted as several “votes” for one molecule or another.

Without the mapping step, Sailfish can complete its RNA analysis 20 to 30 times faster than previous methods.

Dr Kingsford also said the Sailfish method is more robust than previous methods. It’s better able to tolerate errors in the reads or differences between individuals’ genomes.

These errors can prevent some reads from being mapped, he explained. But the Sailfish method can make use of all the RNA read “votes,” which improves the method’s accuracy.

For more information and to download the Sailfish code, visit: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~ckingsf/software/sailfish/. ![]()

Credit: Darren Baker

Researchers say they’ve developed a computational method that dramatically speeds up estimates of gene activity from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data.

With the new method, called Sailfish, estimates of gene expression that previously took hours can be completed in a few minutes.

And the researchers say the accuracy of Sailfish equals or exceeds that of previous methods.

The team described the Sailfish method in Nature Biotechnology.

They noted that gigantic repositories of RNA-seq data now exist, making it possible to re-analyze experiments in light of new discoveries.

“But 15 hours a pop really starts to add up, particularly if you want to look at 100 experiments,” said study author Carl Kingsford, PhD, of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

“With Sailfish, we can give researchers everything they got from previous methods, but faster.”

With previous methods, the RNA molecules from which read sequences originated could be identified and measured only by mapping the reads to their original positions in the larger molecules—a time-consuming process.

Dr Kingsford and his colleagues found this step can actually be eliminated. The team discovered they could allocate parts of the reads to different types of RNA molecules, much as if each read acted as several “votes” for one molecule or another.

Without the mapping step, Sailfish can complete its RNA analysis 20 to 30 times faster than previous methods.

Dr Kingsford also said the Sailfish method is more robust than previous methods. It’s better able to tolerate errors in the reads or differences between individuals’ genomes.

These errors can prevent some reads from being mapped, he explained. But the Sailfish method can make use of all the RNA read “votes,” which improves the method’s accuracy.

For more information and to download the Sailfish code, visit: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~ckingsf/software/sailfish/. ![]()

Credit: Darren Baker

Researchers say they’ve developed a computational method that dramatically speeds up estimates of gene activity from RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data.

With the new method, called Sailfish, estimates of gene expression that previously took hours can be completed in a few minutes.

And the researchers say the accuracy of Sailfish equals or exceeds that of previous methods.

The team described the Sailfish method in Nature Biotechnology.

They noted that gigantic repositories of RNA-seq data now exist, making it possible to re-analyze experiments in light of new discoveries.

“But 15 hours a pop really starts to add up, particularly if you want to look at 100 experiments,” said study author Carl Kingsford, PhD, of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

“With Sailfish, we can give researchers everything they got from previous methods, but faster.”

With previous methods, the RNA molecules from which read sequences originated could be identified and measured only by mapping the reads to their original positions in the larger molecules—a time-consuming process.

Dr Kingsford and his colleagues found this step can actually be eliminated. The team discovered they could allocate parts of the reads to different types of RNA molecules, much as if each read acted as several “votes” for one molecule or another.

Without the mapping step, Sailfish can complete its RNA analysis 20 to 30 times faster than previous methods.

Dr Kingsford also said the Sailfish method is more robust than previous methods. It’s better able to tolerate errors in the reads or differences between individuals’ genomes.

These errors can prevent some reads from being mapped, he explained. But the Sailfish method can make use of all the RNA read “votes,” which improves the method’s accuracy.

For more information and to download the Sailfish code, visit: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~ckingsf/software/sailfish/. ![]()

Molecule shows preclinical activity in leukemias, lymphomas

SAN DIEGO—A small molecule that has previously proven effective against solid tumors exhibits activity against leukemias and lymphomas, preclinical research suggests.

The molecule, LOR-253, showed antiproliferative activity in a range of leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, induced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in vitro, and demonstrated synergy with chemotherapeutic agents.

Ronnie Lum, PhD, and colleagues at Lorus Therapeutics, Inc., the Toronto, Canada-based company developing LOR-253, presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 4544).

LOR-253 acts through induction of the innate tumor suppressor KLF4. Recent research has suggested that upregulation of the transcription factor CDX2 drives the development or progression of leukemic disease. And CDX2 has been shown to silence KLF4, which is reported to be a critical oncogenic event in AML.

Wih this in mind, the researchers decided to test LOR-253’s activity against AML and other hematologic malignancies in vitro.

Experiments revealed that LOR-253 exerts antiproliferative activity against a range of leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, including Ramos, Raji, K-562, Jurkat, MOLT-4, CCRF-CEM, HEL92.1.7, MOLM-13, THP-1, MV411, NB4, HL-60, KG-1, NOMO-1, SKM-1, OCI-AML-2, EOL-1, and Kasumi-1.

IC50 values were substantially lower in these cell lines than in melanoma cell lines, as well as lines of lung, bladder, colon, prostate, and breast cancers.

The researchers also found that LOR-253 induces KLF4 mRNA expression in the AML cell lines HL60 and THP1. This prompts increased expression of p21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that is transcriptionally regulated by KLF4.

Consistent with these results, LOR-253 induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in the AML cell lines, which suggests the molecule acted through its intended mechanism of action.

LOR-253 also showed “strong anticancer synergy” in HL60 cells when delivered in combination with daunorubicin, azacitidine, decitabine, or cytarabine.

When LOR-253 was delivered concurrently with chemotherapy, cell viability decreased the most with cytarabine, followed by decitabine, azacitidine, and daunorubicin. With sequential treatment, cell viability decreased the most when LOR-253 was delivered with decitabine, followed by azacitidine, cytarabine, and daunorubicin.

The researchers said these results suggest LOR-253 could provide a new approach to treat AML and, possibly, other hematologic malignancies.

They are now conducting studies to further characterize the pathway that mediates KLF4 induction by LOR-253, to characterize the effects of LOR-253 in combination with approved chemotherapies for AML, and to assess the efficacy of LOR-253 in animal models of AML.

Lorus Therapeutics is also planning a dose-escalating, phase 1b trial of LOR-253 as monotherapy in AML, myelodysplastic syndromes, and other hematologic malignancies. The company expects to begin the trial this summer. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—A small molecule that has previously proven effective against solid tumors exhibits activity against leukemias and lymphomas, preclinical research suggests.

The molecule, LOR-253, showed antiproliferative activity in a range of leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, induced apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in vitro, and demonstrated synergy with chemotherapeutic agents.

Ronnie Lum, PhD, and colleagues at Lorus Therapeutics, Inc., the Toronto, Canada-based company developing LOR-253, presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 4544).

LOR-253 acts through induction of the innate tumor suppressor KLF4. Recent research has suggested that upregulation of the transcription factor CDX2 drives the development or progression of leukemic disease. And CDX2 has been shown to silence KLF4, which is reported to be a critical oncogenic event in AML.

Wih this in mind, the researchers decided to test LOR-253’s activity against AML and other hematologic malignancies in vitro.

Experiments revealed that LOR-253 exerts antiproliferative activity against a range of leukemia and lymphoma cell lines, including Ramos, Raji, K-562, Jurkat, MOLT-4, CCRF-CEM, HEL92.1.7, MOLM-13, THP-1, MV411, NB4, HL-60, KG-1, NOMO-1, SKM-1, OCI-AML-2, EOL-1, and Kasumi-1.

IC50 values were substantially lower in these cell lines than in melanoma cell lines, as well as lines of lung, bladder, colon, prostate, and breast cancers.

The researchers also found that LOR-253 induces KLF4 mRNA expression in the AML cell lines HL60 and THP1. This prompts increased expression of p21, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor that is transcriptionally regulated by KLF4.

Consistent with these results, LOR-253 induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in the AML cell lines, which suggests the molecule acted through its intended mechanism of action.

LOR-253 also showed “strong anticancer synergy” in HL60 cells when delivered in combination with daunorubicin, azacitidine, decitabine, or cytarabine.

When LOR-253 was delivered concurrently with chemotherapy, cell viability decreased the most with cytarabine, followed by decitabine, azacitidine, and daunorubicin. With sequential treatment, cell viability decreased the most when LOR-253 was delivered with decitabine, followed by azacitidine, cytarabine, and daunorubicin.

The researchers said these results suggest LOR-253 could provide a new approach to treat AML and, possibly, other hematologic malignancies.

They are now conducting studies to further characterize the pathway that mediates KLF4 induction by LOR-253, to characterize the effects of LOR-253 in combination with approved chemotherapies for AML, and to assess the efficacy of LOR-253 in animal models of AML.

Lorus Therapeutics is also planning a dose-escalating, phase 1b trial of LOR-253 as monotherapy in AML, myelodysplastic syndromes, and other hematologic malignancies. The company expects to begin the trial this summer. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—A small molecule that has previously proven effective against solid tumors exhibits activity against leukemias and lymphomas, preclinical research suggests.