User login

HPV vaccine doesn’t increase risk of VTE, team says

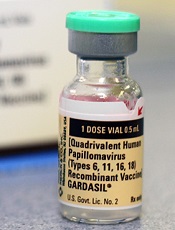

Credit: Jan Christian

Previous research has suggested a potential association between the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

But a new analysis of more than 500,000 women suggests the vaccine does not increase the risk of VTE.

Nikolai Madrid Scheller, of Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, Denmark, and his colleagues conducted the analysis and recounted the results in a letter to JAMA.

The team used data from Danish national registries to evaluate the potential link between quadrivalent HPV vaccination and VTE.

They collected information on vaccination, the use of oral contraceptives, the use of anticoagulants, and the outcome of a first hospital diagnosis of VTE not related to pregnancy, surgery, or cancer.

They included 1,613,798 Danish women ages 10 to 44. Thirty-one percent (n=500,345) of the women received the quadrivalent HPV vaccine.

In all, there were 4375 incident cases of VTE. Twenty percent (n=889) of these women were vaccinated during the study period.

The researchers compared the incidence rates of VTE during predefined risk periods after each vaccine dose with all other observed periods in each individual (control periods). The main risk period was 1 to 42 days from vaccination.

The team found no association between the vaccine and VTE during the 42-day risk period. The crude incidence rate was 0.126 events per person-year for the risk period and 0.159 events per person-year for the control period. The incidence ratio was 0.77.

Results were similar when the researchers performed subgroup analyses by age, including only anticoagulant recipients, only exposed cases, or when adjusting for oral contraceptive use.

“Our results, which were consistent after adjustment for oral contraceptive use and in girls and young women as well as mid-adult women, do not provide support for an increased risk of VTE following quadrivalent HPV vaccination,” the researchers concluded. ![]()

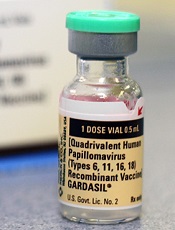

Credit: Jan Christian

Previous research has suggested a potential association between the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

But a new analysis of more than 500,000 women suggests the vaccine does not increase the risk of VTE.

Nikolai Madrid Scheller, of Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, Denmark, and his colleagues conducted the analysis and recounted the results in a letter to JAMA.

The team used data from Danish national registries to evaluate the potential link between quadrivalent HPV vaccination and VTE.

They collected information on vaccination, the use of oral contraceptives, the use of anticoagulants, and the outcome of a first hospital diagnosis of VTE not related to pregnancy, surgery, or cancer.

They included 1,613,798 Danish women ages 10 to 44. Thirty-one percent (n=500,345) of the women received the quadrivalent HPV vaccine.

In all, there were 4375 incident cases of VTE. Twenty percent (n=889) of these women were vaccinated during the study period.

The researchers compared the incidence rates of VTE during predefined risk periods after each vaccine dose with all other observed periods in each individual (control periods). The main risk period was 1 to 42 days from vaccination.

The team found no association between the vaccine and VTE during the 42-day risk period. The crude incidence rate was 0.126 events per person-year for the risk period and 0.159 events per person-year for the control period. The incidence ratio was 0.77.

Results were similar when the researchers performed subgroup analyses by age, including only anticoagulant recipients, only exposed cases, or when adjusting for oral contraceptive use.

“Our results, which were consistent after adjustment for oral contraceptive use and in girls and young women as well as mid-adult women, do not provide support for an increased risk of VTE following quadrivalent HPV vaccination,” the researchers concluded. ![]()

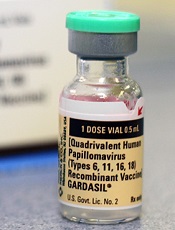

Credit: Jan Christian

Previous research has suggested a potential association between the quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and venous thromboembolism (VTE).

But a new analysis of more than 500,000 women suggests the vaccine does not increase the risk of VTE.

Nikolai Madrid Scheller, of Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, Denmark, and his colleagues conducted the analysis and recounted the results in a letter to JAMA.

The team used data from Danish national registries to evaluate the potential link between quadrivalent HPV vaccination and VTE.

They collected information on vaccination, the use of oral contraceptives, the use of anticoagulants, and the outcome of a first hospital diagnosis of VTE not related to pregnancy, surgery, or cancer.

They included 1,613,798 Danish women ages 10 to 44. Thirty-one percent (n=500,345) of the women received the quadrivalent HPV vaccine.

In all, there were 4375 incident cases of VTE. Twenty percent (n=889) of these women were vaccinated during the study period.

The researchers compared the incidence rates of VTE during predefined risk periods after each vaccine dose with all other observed periods in each individual (control periods). The main risk period was 1 to 42 days from vaccination.

The team found no association between the vaccine and VTE during the 42-day risk period. The crude incidence rate was 0.126 events per person-year for the risk period and 0.159 events per person-year for the control period. The incidence ratio was 0.77.

Results were similar when the researchers performed subgroup analyses by age, including only anticoagulant recipients, only exposed cases, or when adjusting for oral contraceptive use.

“Our results, which were consistent after adjustment for oral contraceptive use and in girls and young women as well as mid-adult women, do not provide support for an increased risk of VTE following quadrivalent HPV vaccination,” the researchers concluded. ![]()

Increasing AYA enrollment in cancer trials

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Age limits on clinical trials must be more flexible to allow more adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients the opportunity to access new treatments, according to a report published in The Lancet Oncology.

The report’s authors discovered that expanding age eligibility criteria for cancer trials increased the enrollment of AYA patients and patients belonging to other age groups. But there is still room for improvement, according to the authors.

“[R]ight now, too many of our young patients are needlessly falling through the gap between pediatric and adult cancer trials,” said Lorna Fern, PhD, of University College London Hospitals in the UK.

“By encouraging doctors to take into account the full age range of patients affected by individual types of cancer, we’ve shown that it’s possible to design trials that include teenage cancer patients and, importantly, that better match the underlying biology of the disease and the people affected.”

To assess AYA enrollment in cancer trials, Dr Fern and her colleagues looked at 68,275 cancer patients aged 0 to 59 years. They were diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, or solid tumor malignancies between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2010.

During this 6-year period, trial participation increased among all age groups. There was a 13% increase in participation among 15- to 19-year-olds (from 24% to 37%), a 5% increase among 20- to 24-year-olds (from 13% to 18%), and a 6% increase among 0- to 14-year-olds (from 52% to 58%).

Dr Fern and her colleagues said the rise in enrollment, particularly among AYAs, was due to increased availability and access to trials; increased awareness from healthcare professionals, patients, and the public about research; and the opening of trials with broader age limits that allow AYAs to enter trials.

In light of this study, Cancer Research UK has started asking researchers to justify age restrictions on new studies, in an effort to recruit more AYA cancer patients onto its trials.

“[I]t’s vital that effective treatments are being developed to tackle cancer across all age brackets,” said Kate Law, Cancer Research UK’s director of clinical trials.

“We now only accept age limits on our clinical trials if they are backed up by hard evidence, which will hopefully mean more young cancer patients get the chance to contribute to research and have the latest experimental treatments.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Age limits on clinical trials must be more flexible to allow more adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients the opportunity to access new treatments, according to a report published in The Lancet Oncology.

The report’s authors discovered that expanding age eligibility criteria for cancer trials increased the enrollment of AYA patients and patients belonging to other age groups. But there is still room for improvement, according to the authors.

“[R]ight now, too many of our young patients are needlessly falling through the gap between pediatric and adult cancer trials,” said Lorna Fern, PhD, of University College London Hospitals in the UK.

“By encouraging doctors to take into account the full age range of patients affected by individual types of cancer, we’ve shown that it’s possible to design trials that include teenage cancer patients and, importantly, that better match the underlying biology of the disease and the people affected.”

To assess AYA enrollment in cancer trials, Dr Fern and her colleagues looked at 68,275 cancer patients aged 0 to 59 years. They were diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, or solid tumor malignancies between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2010.

During this 6-year period, trial participation increased among all age groups. There was a 13% increase in participation among 15- to 19-year-olds (from 24% to 37%), a 5% increase among 20- to 24-year-olds (from 13% to 18%), and a 6% increase among 0- to 14-year-olds (from 52% to 58%).

Dr Fern and her colleagues said the rise in enrollment, particularly among AYAs, was due to increased availability and access to trials; increased awareness from healthcare professionals, patients, and the public about research; and the opening of trials with broader age limits that allow AYAs to enter trials.

In light of this study, Cancer Research UK has started asking researchers to justify age restrictions on new studies, in an effort to recruit more AYA cancer patients onto its trials.

“[I]t’s vital that effective treatments are being developed to tackle cancer across all age brackets,” said Kate Law, Cancer Research UK’s director of clinical trials.

“We now only accept age limits on our clinical trials if they are backed up by hard evidence, which will hopefully mean more young cancer patients get the chance to contribute to research and have the latest experimental treatments.” ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Age limits on clinical trials must be more flexible to allow more adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients the opportunity to access new treatments, according to a report published in The Lancet Oncology.

The report’s authors discovered that expanding age eligibility criteria for cancer trials increased the enrollment of AYA patients and patients belonging to other age groups. But there is still room for improvement, according to the authors.

“[R]ight now, too many of our young patients are needlessly falling through the gap between pediatric and adult cancer trials,” said Lorna Fern, PhD, of University College London Hospitals in the UK.

“By encouraging doctors to take into account the full age range of patients affected by individual types of cancer, we’ve shown that it’s possible to design trials that include teenage cancer patients and, importantly, that better match the underlying biology of the disease and the people affected.”

To assess AYA enrollment in cancer trials, Dr Fern and her colleagues looked at 68,275 cancer patients aged 0 to 59 years. They were diagnosed with leukemias, lymphomas, or solid tumor malignancies between April 1, 2005, and March 31, 2010.

During this 6-year period, trial participation increased among all age groups. There was a 13% increase in participation among 15- to 19-year-olds (from 24% to 37%), a 5% increase among 20- to 24-year-olds (from 13% to 18%), and a 6% increase among 0- to 14-year-olds (from 52% to 58%).

Dr Fern and her colleagues said the rise in enrollment, particularly among AYAs, was due to increased availability and access to trials; increased awareness from healthcare professionals, patients, and the public about research; and the opening of trials with broader age limits that allow AYAs to enter trials.

In light of this study, Cancer Research UK has started asking researchers to justify age restrictions on new studies, in an effort to recruit more AYA cancer patients onto its trials.

“[I]t’s vital that effective treatments are being developed to tackle cancer across all age brackets,” said Kate Law, Cancer Research UK’s director of clinical trials.

“We now only accept age limits on our clinical trials if they are backed up by hard evidence, which will hopefully mean more young cancer patients get the chance to contribute to research and have the latest experimental treatments.” ![]()

CAR T-cell therapy gets breakthrough designation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the T-cell therapy CTL019 to treat adults and children with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The therapy consists of a patient’s own T cells genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) directed against CD19.

CTL019 is the first personalized cellular therapy for cancer to receive breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new medicines that treat serious or life-threatening conditions, if the therapy has demonstrated substantial improvement over available therapies.

The breakthrough designation for CTL019 is based on early trial results in adults and children with ALL.

At ASH 2013, researchers presented results of the first 27 ALL patients (22 children and 5 adults) treated with CTL019. Eighty-nine percent of the patients achieved a complete response to the treatment. Six patients relapsed during follow-up, which ranged from 2 months to 18 months.

There was also a high rate of toxicity, particularly cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved via treatment with the IL-6 agonist tocilizumab.

The first pediatric ALL patient to receive CTL019 celebrated the second anniversary of her cancer remission in May. And the first adult patient remains in remission 1 year after receiving the therapy.

“Our early findings reveal tremendous promise for a desperate group of patients, many of whom have been able to return to their normal lives at school and work after receiving this new, personalized immunotherapy,” said Carl June, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Receiving the FDA’s breakthrough designation is an essential step in our work with Novartis to expand this therapy to patients across the world who desperately need new options to help them fight this disease.”

In August 2012, the University of Pennsylvania announced an exclusive global research and licensing agreement with Novartis to further study, develop, and commercialize personalized CAR T-cell therapies for the treatment of cancers.

Trials of CTL019 began in the summer of 2010 in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and they are now underway for patients with ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma.

CTL019 cells are a patients’ own T cells genetically engineered to express an anti-CD19 scFv coupled to CD3ζ signaling and 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains. The cells are activated and expanded ex vivo with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads, then infused into patients. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the T-cell therapy CTL019 to treat adults and children with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The therapy consists of a patient’s own T cells genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) directed against CD19.

CTL019 is the first personalized cellular therapy for cancer to receive breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new medicines that treat serious or life-threatening conditions, if the therapy has demonstrated substantial improvement over available therapies.

The breakthrough designation for CTL019 is based on early trial results in adults and children with ALL.

At ASH 2013, researchers presented results of the first 27 ALL patients (22 children and 5 adults) treated with CTL019. Eighty-nine percent of the patients achieved a complete response to the treatment. Six patients relapsed during follow-up, which ranged from 2 months to 18 months.

There was also a high rate of toxicity, particularly cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved via treatment with the IL-6 agonist tocilizumab.

The first pediatric ALL patient to receive CTL019 celebrated the second anniversary of her cancer remission in May. And the first adult patient remains in remission 1 year after receiving the therapy.

“Our early findings reveal tremendous promise for a desperate group of patients, many of whom have been able to return to their normal lives at school and work after receiving this new, personalized immunotherapy,” said Carl June, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Receiving the FDA’s breakthrough designation is an essential step in our work with Novartis to expand this therapy to patients across the world who desperately need new options to help them fight this disease.”

In August 2012, the University of Pennsylvania announced an exclusive global research and licensing agreement with Novartis to further study, develop, and commercialize personalized CAR T-cell therapies for the treatment of cancers.

Trials of CTL019 began in the summer of 2010 in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and they are now underway for patients with ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma.

CTL019 cells are a patients’ own T cells genetically engineered to express an anti-CD19 scFv coupled to CD3ζ signaling and 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains. The cells are activated and expanded ex vivo with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads, then infused into patients. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the T-cell therapy CTL019 to treat adults and children with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The therapy consists of a patient’s own T cells genetically engineered to produce chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) directed against CD19.

CTL019 is the first personalized cellular therapy for cancer to receive breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new medicines that treat serious or life-threatening conditions, if the therapy has demonstrated substantial improvement over available therapies.

The breakthrough designation for CTL019 is based on early trial results in adults and children with ALL.

At ASH 2013, researchers presented results of the first 27 ALL patients (22 children and 5 adults) treated with CTL019. Eighty-nine percent of the patients achieved a complete response to the treatment. Six patients relapsed during follow-up, which ranged from 2 months to 18 months.

There was also a high rate of toxicity, particularly cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved via treatment with the IL-6 agonist tocilizumab.

The first pediatric ALL patient to receive CTL019 celebrated the second anniversary of her cancer remission in May. And the first adult patient remains in remission 1 year after receiving the therapy.

“Our early findings reveal tremendous promise for a desperate group of patients, many of whom have been able to return to their normal lives at school and work after receiving this new, personalized immunotherapy,” said Carl June, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania.

“Receiving the FDA’s breakthrough designation is an essential step in our work with Novartis to expand this therapy to patients across the world who desperately need new options to help them fight this disease.”

In August 2012, the University of Pennsylvania announced an exclusive global research and licensing agreement with Novartis to further study, develop, and commercialize personalized CAR T-cell therapies for the treatment of cancers.

Trials of CTL019 began in the summer of 2010 in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and they are now underway for patients with ALL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma.

CTL019 cells are a patients’ own T cells genetically engineered to express an anti-CD19 scFv coupled to CD3ζ signaling and 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains. The cells are activated and expanded ex vivo with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads, then infused into patients. ![]()

Physician-assisted suicide and changing state laws

Under British common law, suicide was a felony if committed by a person "in the years of discretion," in other words, by an adult, who was "of sound mind." An adult who killed himself while insane was not considered a criminal. While the offender obviously could not be punished, he also could not be buried in hallowed ground, and all of his property was seized by the crown. Surviving family members were not allowed to inherit.

While no state defines suicide itself as a crime by statute, there are still common law and statutory prohibitions against aiding or abetting, or encouraging, a suicide. Laws surrounding assisted suicide might seem remote or irrelevant now, but clinicians should be aware that this is changing on an almost monthly basis, and impetus is building through the support of various advocacy groups, such as Compassion & Choices, Final Exit Network,and the Euthanasia Research and Guidance Organization (ERGO).

My own interest in this topic was spurred when a recent Maryland gubernatorial candidate ran on a platform that included a plan to introduce legislation to allow physician-assisted suicide. Presently, our state defines assisted suicide as a felony offense punishable by 1 year of incarceration and a $10,000 fine, and there have been two criminal prosecutions for assisted suicide in recent years.

Nationally, 39 states have prohibitions against assisted suicide defined either by specific statute or contained within the definition of manslaughter. Some states ban assisted suicide by case law, some through the adoption of common law. Presently, five states allow physician-assisted suicide. Oregon, Washington, and Montana were among the first states to allow this. New Mexico and Vermont adopted legislation this year in January and May, respectively.

Most states have modeled their laws after the original physician-assisted suicide law, Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act. For psychiatrists involved in legislative affairs, familiarity with this law is essential.

Under the Death With Dignity Act, a person might be eligible to request physician aid in dying if he is an adult resident of the state, is able to make and communicate medical decisions, and has a 6-month prognosis as medically confirmed by two physicians. The patient must make an initial oral and written request, then repeat the oral request no sooner than 15 days later. The written request must be submitted on a state-mandated form witnessed by two people who can neither be blood relatives nor estate benefactors.

There is a requirement for informed consent, specifically that the person must know his medical diagnosis as well as the risk of taking the life-ending medication and the expected result of this act. There must be documented consideration of alternatives to suicide.

While there is a statutory mandate to refer patients for counseling if depression is suspected, there is no requirement that the patient seeking suicide be screened for this disorder or even have a capacity assessment performed by a psychiatrist.

Out of curiosity, I copied the text of the physician-assisted suicide request form through two text analyzing applications to determine the readability of the document. My two tests revealed that the form required between a 12th grade to college-level reading comprehension level. For comparison purposes, my average prison clinic patient has a 9th-grade education with a 6th-grade reading level.

The most easily understood sentence in the entire document was the instruction at the bottom of the form: "PLEASE MAKE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO KEEP IN YOUR HOME."

This makes sense when you consider the demographics of those who seek physician-assisted suicide in Oregon. Most were white, college educated, over age 65 years, and suffered from cancer or chronic respiratory disease. Since the law was passed, 752 out of 1,173 people, or 64% of those given prescriptions, ended their lives. Only 2 of the 71 people who died in 2013 were referred for psychiatric or psychological evaluation. Most died of suicide within the year; however, some died the following year.

Without discussing the merits and controversy of physician-assisted suicide per se, we can at least identify some obvious weaknesses in copy-and-paste legislation between states. A law that appears tailored for an educated majority culture, which accepts capacity at face value despite clearly concerning circumstances, would at least require substantial revision for a region with high rates of illiteracy or mental illness.

Other questions also are looming on the horizon: Should qualifying conditions be limited to medical conditions only? Could an advance directive include an option to request assisted suicide proactively, prior to a 6-month prognosis, or could it be requested through a designated proxy? If a patient has both a psychiatric disorder and a terminal medical condition, should laws for involuntary psychiatric care still apply?

Dr. Lawrence Egbert, retired anesthesiologist and former medical director of Final Exit Network, foretold these questions in a Washington Post interview in which he stated he "is also willing, in extreme cases, he says, to serve as an ‘exit guide’ for patients who have suffered from depression for extended periods of time."

Only time will tell how these issues play out, but with some background on the topic our profession can at least begin the discussion.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

Under British common law, suicide was a felony if committed by a person "in the years of discretion," in other words, by an adult, who was "of sound mind." An adult who killed himself while insane was not considered a criminal. While the offender obviously could not be punished, he also could not be buried in hallowed ground, and all of his property was seized by the crown. Surviving family members were not allowed to inherit.

While no state defines suicide itself as a crime by statute, there are still common law and statutory prohibitions against aiding or abetting, or encouraging, a suicide. Laws surrounding assisted suicide might seem remote or irrelevant now, but clinicians should be aware that this is changing on an almost monthly basis, and impetus is building through the support of various advocacy groups, such as Compassion & Choices, Final Exit Network,and the Euthanasia Research and Guidance Organization (ERGO).

My own interest in this topic was spurred when a recent Maryland gubernatorial candidate ran on a platform that included a plan to introduce legislation to allow physician-assisted suicide. Presently, our state defines assisted suicide as a felony offense punishable by 1 year of incarceration and a $10,000 fine, and there have been two criminal prosecutions for assisted suicide in recent years.

Nationally, 39 states have prohibitions against assisted suicide defined either by specific statute or contained within the definition of manslaughter. Some states ban assisted suicide by case law, some through the adoption of common law. Presently, five states allow physician-assisted suicide. Oregon, Washington, and Montana were among the first states to allow this. New Mexico and Vermont adopted legislation this year in January and May, respectively.

Most states have modeled their laws after the original physician-assisted suicide law, Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act. For psychiatrists involved in legislative affairs, familiarity with this law is essential.

Under the Death With Dignity Act, a person might be eligible to request physician aid in dying if he is an adult resident of the state, is able to make and communicate medical decisions, and has a 6-month prognosis as medically confirmed by two physicians. The patient must make an initial oral and written request, then repeat the oral request no sooner than 15 days later. The written request must be submitted on a state-mandated form witnessed by two people who can neither be blood relatives nor estate benefactors.

There is a requirement for informed consent, specifically that the person must know his medical diagnosis as well as the risk of taking the life-ending medication and the expected result of this act. There must be documented consideration of alternatives to suicide.

While there is a statutory mandate to refer patients for counseling if depression is suspected, there is no requirement that the patient seeking suicide be screened for this disorder or even have a capacity assessment performed by a psychiatrist.

Out of curiosity, I copied the text of the physician-assisted suicide request form through two text analyzing applications to determine the readability of the document. My two tests revealed that the form required between a 12th grade to college-level reading comprehension level. For comparison purposes, my average prison clinic patient has a 9th-grade education with a 6th-grade reading level.

The most easily understood sentence in the entire document was the instruction at the bottom of the form: "PLEASE MAKE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO KEEP IN YOUR HOME."

This makes sense when you consider the demographics of those who seek physician-assisted suicide in Oregon. Most were white, college educated, over age 65 years, and suffered from cancer or chronic respiratory disease. Since the law was passed, 752 out of 1,173 people, or 64% of those given prescriptions, ended their lives. Only 2 of the 71 people who died in 2013 were referred for psychiatric or psychological evaluation. Most died of suicide within the year; however, some died the following year.

Without discussing the merits and controversy of physician-assisted suicide per se, we can at least identify some obvious weaknesses in copy-and-paste legislation between states. A law that appears tailored for an educated majority culture, which accepts capacity at face value despite clearly concerning circumstances, would at least require substantial revision for a region with high rates of illiteracy or mental illness.

Other questions also are looming on the horizon: Should qualifying conditions be limited to medical conditions only? Could an advance directive include an option to request assisted suicide proactively, prior to a 6-month prognosis, or could it be requested through a designated proxy? If a patient has both a psychiatric disorder and a terminal medical condition, should laws for involuntary psychiatric care still apply?

Dr. Lawrence Egbert, retired anesthesiologist and former medical director of Final Exit Network, foretold these questions in a Washington Post interview in which he stated he "is also willing, in extreme cases, he says, to serve as an ‘exit guide’ for patients who have suffered from depression for extended periods of time."

Only time will tell how these issues play out, but with some background on the topic our profession can at least begin the discussion.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

Under British common law, suicide was a felony if committed by a person "in the years of discretion," in other words, by an adult, who was "of sound mind." An adult who killed himself while insane was not considered a criminal. While the offender obviously could not be punished, he also could not be buried in hallowed ground, and all of his property was seized by the crown. Surviving family members were not allowed to inherit.

While no state defines suicide itself as a crime by statute, there are still common law and statutory prohibitions against aiding or abetting, or encouraging, a suicide. Laws surrounding assisted suicide might seem remote or irrelevant now, but clinicians should be aware that this is changing on an almost monthly basis, and impetus is building through the support of various advocacy groups, such as Compassion & Choices, Final Exit Network,and the Euthanasia Research and Guidance Organization (ERGO).

My own interest in this topic was spurred when a recent Maryland gubernatorial candidate ran on a platform that included a plan to introduce legislation to allow physician-assisted suicide. Presently, our state defines assisted suicide as a felony offense punishable by 1 year of incarceration and a $10,000 fine, and there have been two criminal prosecutions for assisted suicide in recent years.

Nationally, 39 states have prohibitions against assisted suicide defined either by specific statute or contained within the definition of manslaughter. Some states ban assisted suicide by case law, some through the adoption of common law. Presently, five states allow physician-assisted suicide. Oregon, Washington, and Montana were among the first states to allow this. New Mexico and Vermont adopted legislation this year in January and May, respectively.

Most states have modeled their laws after the original physician-assisted suicide law, Oregon’s Death With Dignity Act. For psychiatrists involved in legislative affairs, familiarity with this law is essential.

Under the Death With Dignity Act, a person might be eligible to request physician aid in dying if he is an adult resident of the state, is able to make and communicate medical decisions, and has a 6-month prognosis as medically confirmed by two physicians. The patient must make an initial oral and written request, then repeat the oral request no sooner than 15 days later. The written request must be submitted on a state-mandated form witnessed by two people who can neither be blood relatives nor estate benefactors.

There is a requirement for informed consent, specifically that the person must know his medical diagnosis as well as the risk of taking the life-ending medication and the expected result of this act. There must be documented consideration of alternatives to suicide.

While there is a statutory mandate to refer patients for counseling if depression is suspected, there is no requirement that the patient seeking suicide be screened for this disorder or even have a capacity assessment performed by a psychiatrist.

Out of curiosity, I copied the text of the physician-assisted suicide request form through two text analyzing applications to determine the readability of the document. My two tests revealed that the form required between a 12th grade to college-level reading comprehension level. For comparison purposes, my average prison clinic patient has a 9th-grade education with a 6th-grade reading level.

The most easily understood sentence in the entire document was the instruction at the bottom of the form: "PLEASE MAKE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO KEEP IN YOUR HOME."

This makes sense when you consider the demographics of those who seek physician-assisted suicide in Oregon. Most were white, college educated, over age 65 years, and suffered from cancer or chronic respiratory disease. Since the law was passed, 752 out of 1,173 people, or 64% of those given prescriptions, ended their lives. Only 2 of the 71 people who died in 2013 were referred for psychiatric or psychological evaluation. Most died of suicide within the year; however, some died the following year.

Without discussing the merits and controversy of physician-assisted suicide per se, we can at least identify some obvious weaknesses in copy-and-paste legislation between states. A law that appears tailored for an educated majority culture, which accepts capacity at face value despite clearly concerning circumstances, would at least require substantial revision for a region with high rates of illiteracy or mental illness.

Other questions also are looming on the horizon: Should qualifying conditions be limited to medical conditions only? Could an advance directive include an option to request assisted suicide proactively, prior to a 6-month prognosis, or could it be requested through a designated proxy? If a patient has both a psychiatric disorder and a terminal medical condition, should laws for involuntary psychiatric care still apply?

Dr. Lawrence Egbert, retired anesthesiologist and former medical director of Final Exit Network, foretold these questions in a Washington Post interview in which he stated he "is also willing, in extreme cases, he says, to serve as an ‘exit guide’ for patients who have suffered from depression for extended periods of time."

Only time will tell how these issues play out, but with some background on the topic our profession can at least begin the discussion.

Dr. Hanson is a forensic psychiatrist and coauthor of "Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work" (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). The opinions expressed are those of the author only, and do not represent those of any of Dr. Hanson’s employers or consultees, including the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene or the Maryland Division of Correction.

FDA approves belinostat for peripheral T-cell lymphoma

Belinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, has been approved for treating peripheral T-cell lymphoma, based on the results of the BELIEF study that found an overall response rate of nearly 26% among treated patients.

This is the third drug approved for this rare, aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) since 2009, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approval on July 3.

The other two drugs are pralatrexate injection (Folotyn), a folate analogue metabolic inhibitor approved in 2009 for treating relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL); and romidepsin (Istodax), a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved in 2011 for treating PTCL in patients who have received at least one previous treatment.

This is an accelerated approval, which is based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints considered by the FDA as "reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs." Confirmatory trials that verify the clinical benefit are required for full approval; otherwise, the approval can be withdrawn by the FDA. Belinostat will be marketed as Beleodaq by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, which also markets Folotyn.

HDAC inhibitors "catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from the lysine residues of histones and some nonhistone proteins," and in vitro, belinostat "caused the accumulation of acetylated histones and other proteins, inducing cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis of some transformed cells," according to a statement on the approval, issued by Spectrum on July 7. "Belinostat shows preferential cytotoxicity towards tumor cells compared to normal cells," and it "inhibited the enzymatic activity of histone deacetylases at nanomolar concentrations," the statement said.

In the BELIEF study, an open-label, single-arm, nonrandomized study, 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL were treated with belinostat, administered via an IV infusion, once a day on days 1-5 of a 21-day cycle, repeated every 3 weeks until the disease progressed or adverse effects became unacceptable. The overall response rate (complete and partial responses), the primary efficacy endpoint, was 25.8%. Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pyrexia, and anemia were the most common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

The company said that the drug is expected to be available in less than 3 weeks of approval (before July 24). The confirmatory trial is a phase III study that will evaluate belinostat plus CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone), compared with CHOP alone.

PTCL accounts for about 10%-15% of NHL cases in North America, according to the FDA, which cites National Cancer Institute estimates that 70,800 Americans will be diagnosed with NHL and 18,990 will die of NHL in 2014.

The prescribing information for belinostat is available here.

Belinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, has been approved for treating peripheral T-cell lymphoma, based on the results of the BELIEF study that found an overall response rate of nearly 26% among treated patients.

This is the third drug approved for this rare, aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) since 2009, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approval on July 3.

The other two drugs are pralatrexate injection (Folotyn), a folate analogue metabolic inhibitor approved in 2009 for treating relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL); and romidepsin (Istodax), a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved in 2011 for treating PTCL in patients who have received at least one previous treatment.

This is an accelerated approval, which is based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints considered by the FDA as "reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs." Confirmatory trials that verify the clinical benefit are required for full approval; otherwise, the approval can be withdrawn by the FDA. Belinostat will be marketed as Beleodaq by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, which also markets Folotyn.

HDAC inhibitors "catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from the lysine residues of histones and some nonhistone proteins," and in vitro, belinostat "caused the accumulation of acetylated histones and other proteins, inducing cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis of some transformed cells," according to a statement on the approval, issued by Spectrum on July 7. "Belinostat shows preferential cytotoxicity towards tumor cells compared to normal cells," and it "inhibited the enzymatic activity of histone deacetylases at nanomolar concentrations," the statement said.

In the BELIEF study, an open-label, single-arm, nonrandomized study, 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL were treated with belinostat, administered via an IV infusion, once a day on days 1-5 of a 21-day cycle, repeated every 3 weeks until the disease progressed or adverse effects became unacceptable. The overall response rate (complete and partial responses), the primary efficacy endpoint, was 25.8%. Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pyrexia, and anemia were the most common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

The company said that the drug is expected to be available in less than 3 weeks of approval (before July 24). The confirmatory trial is a phase III study that will evaluate belinostat plus CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone), compared with CHOP alone.

PTCL accounts for about 10%-15% of NHL cases in North America, according to the FDA, which cites National Cancer Institute estimates that 70,800 Americans will be diagnosed with NHL and 18,990 will die of NHL in 2014.

The prescribing information for belinostat is available here.

Belinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, has been approved for treating peripheral T-cell lymphoma, based on the results of the BELIEF study that found an overall response rate of nearly 26% among treated patients.

This is the third drug approved for this rare, aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) since 2009, according to the Food and Drug Administration statement announcing the approval on July 3.

The other two drugs are pralatrexate injection (Folotyn), a folate analogue metabolic inhibitor approved in 2009 for treating relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL); and romidepsin (Istodax), a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor approved in 2011 for treating PTCL in patients who have received at least one previous treatment.

This is an accelerated approval, which is based on surrogate or intermediate endpoints considered by the FDA as "reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit for patients with serious conditions with unmet medical needs." Confirmatory trials that verify the clinical benefit are required for full approval; otherwise, the approval can be withdrawn by the FDA. Belinostat will be marketed as Beleodaq by Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, which also markets Folotyn.

HDAC inhibitors "catalyze the removal of acetyl groups from the lysine residues of histones and some nonhistone proteins," and in vitro, belinostat "caused the accumulation of acetylated histones and other proteins, inducing cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis of some transformed cells," according to a statement on the approval, issued by Spectrum on July 7. "Belinostat shows preferential cytotoxicity towards tumor cells compared to normal cells," and it "inhibited the enzymatic activity of histone deacetylases at nanomolar concentrations," the statement said.

In the BELIEF study, an open-label, single-arm, nonrandomized study, 129 patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL were treated with belinostat, administered via an IV infusion, once a day on days 1-5 of a 21-day cycle, repeated every 3 weeks until the disease progressed or adverse effects became unacceptable. The overall response rate (complete and partial responses), the primary efficacy endpoint, was 25.8%. Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, pyrexia, and anemia were the most common adverse events associated with treatment, according to the FDA.

The company said that the drug is expected to be available in less than 3 weeks of approval (before July 24). The confirmatory trial is a phase III study that will evaluate belinostat plus CHOP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone), compared with CHOP alone.

PTCL accounts for about 10%-15% of NHL cases in North America, according to the FDA, which cites National Cancer Institute estimates that 70,800 Americans will be diagnosed with NHL and 18,990 will die of NHL in 2014.

The prescribing information for belinostat is available here.

Hailey-Hailey Disease

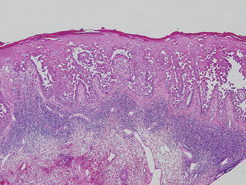

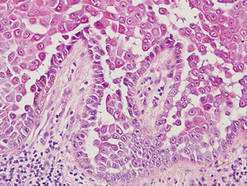

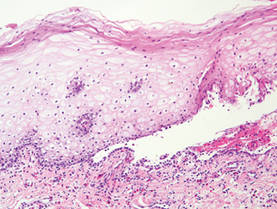

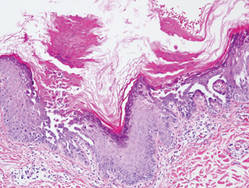

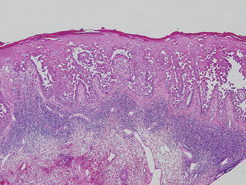

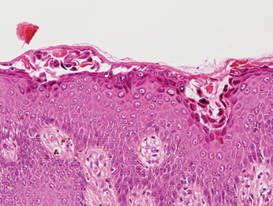

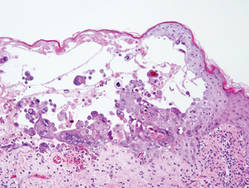

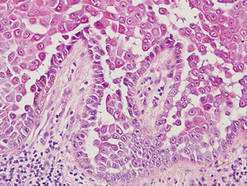

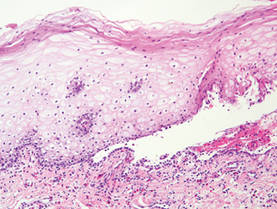

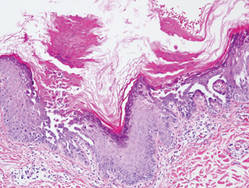

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

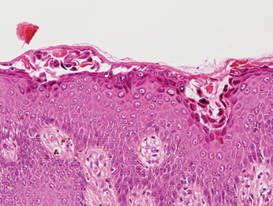

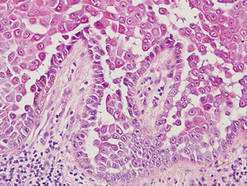

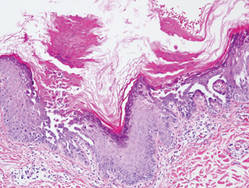

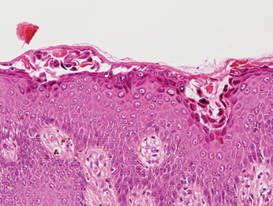

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.

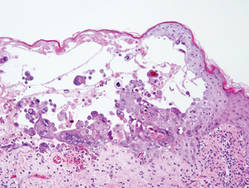

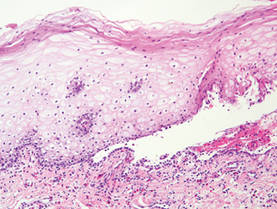

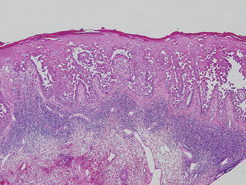

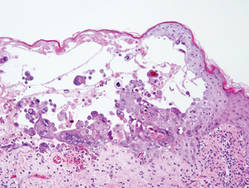

Pemphigus foliaceus is another autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that is characterized by acantholysis in the granular or upper spinous layers (Figure 4).3 The epidermis is not thickened. Sometimes acantholytic cells show dyskeratotic change (Figure 4). Some biopsy specimens do not contain the roof of the bullae; therefore, only erosion is seen and the diagnosis may be missed. Moreover, when only the adnexal epithelium shows acantholysis without epidermal involvement, diagnosis can be difficult.4 Acantholysis is accompanied with a superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate may vary. Bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome reveal a similar histopathologic pattern. Direct immunofluorescence usually discloses IgG and/or C3 deposition on cell surfaces of keratinocytes in the entire or upper epidermis.

Herpesvirus infection shows ballooning (intracellular edema) of keratinocytes. Eventually acantholysis occurs and intraepidermal bullae are formed. In the bullae, virus-associated acantholytic keratinocytes, some that are multinucleated, can be easily found (Figure 5).5 These cells are larger than normal keratinocytes and have steel gray nuclei with peripheral accentuation. Some of these cells are necrotic, and the remains of necrotic multinucleated acantholytic cells are easily recognized. Adnexal epithelial cells occasionally are affected by herpesvirus infection; nuclear change is similar to the epidermis. A perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils is seen. Neutrophils accumulate within the old bullae, clinically manifesting as a pustule.

Darier disease is characterized by suprabasal clefts and acantholysis above the basal layer (Figure 6).6 Similar to HHD, villi protrude within the clefts (Figure 6). Conspicuous columns of parakeratosis above the acantholytic epidermis often are observed. Dyskeratotic cells exist among acantholytic ke-ratinocytes in the granular layer and parakeratotic column, which are known as corps ronds and crops grains, respectively. A scant to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate is found in the upper dermis.

- Hernandez-Perez E. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Cutis. 1987;39:75-77.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:373-380, vii.

- Dasher D, Rubenstein D, Diaz LA. Pemphigus foliaceus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2008;10:182-194.

- Ohata C, Akamatsu K, Imai N, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus exclusively involving the follicular infundibulum: a novel peau d’orange appearance. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:392-395.

- King DF, King LA. Giant cells in lesions of varicella and herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:456-458.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.

Pemphigus foliaceus is another autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that is characterized by acantholysis in the granular or upper spinous layers (Figure 4).3 The epidermis is not thickened. Sometimes acantholytic cells show dyskeratotic change (Figure 4). Some biopsy specimens do not contain the roof of the bullae; therefore, only erosion is seen and the diagnosis may be missed. Moreover, when only the adnexal epithelium shows acantholysis without epidermal involvement, diagnosis can be difficult.4 Acantholysis is accompanied with a superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate may vary. Bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome reveal a similar histopathologic pattern. Direct immunofluorescence usually discloses IgG and/or C3 deposition on cell surfaces of keratinocytes in the entire or upper epidermis.

Herpesvirus infection shows ballooning (intracellular edema) of keratinocytes. Eventually acantholysis occurs and intraepidermal bullae are formed. In the bullae, virus-associated acantholytic keratinocytes, some that are multinucleated, can be easily found (Figure 5).5 These cells are larger than normal keratinocytes and have steel gray nuclei with peripheral accentuation. Some of these cells are necrotic, and the remains of necrotic multinucleated acantholytic cells are easily recognized. Adnexal epithelial cells occasionally are affected by herpesvirus infection; nuclear change is similar to the epidermis. A perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils is seen. Neutrophils accumulate within the old bullae, clinically manifesting as a pustule.

Darier disease is characterized by suprabasal clefts and acantholysis above the basal layer (Figure 6).6 Similar to HHD, villi protrude within the clefts (Figure 6). Conspicuous columns of parakeratosis above the acantholytic epidermis often are observed. Dyskeratotic cells exist among acantholytic ke-ratinocytes in the granular layer and parakeratotic column, which are known as corps ronds and crops grains, respectively. A scant to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate is found in the upper dermis.

Hailey-Hailey disease (HHD), or benign familial chronic pemphigus, typically presents as suprabasal blisters with a perivascular and interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1).1 Villi, or elongated dermal papillae lined with a single layer of basal cells, protrude into the bullae (Figure 2). In HHD lesions, the epidermis is thickened with scale-crust, and at least the lower half of the epidermis shows acantholysis. Despite the acantholytic changes, a few intact intercellular bridges remain, giving the appearance of a dilapidated brick wall (Figure 2). There may be dyskeratotic cells among the acantholytic cells, though they are scant in many cases. These acantholytic dyskeratotic cells have eosinophilic polygonal-shaped cytoplasm. Hailey-Hailey disease typically does not show adnexal extension of the acantholysis. Direct immunofluorescence is negative in HHD.

Pemphigus vulgaris is an autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that presents with suprabasal acantholysis (Figure 3).2 The epidermis is not thickened and acantholysis is limited to the suprabasal layer. Acantholytic cells with eosinophils and/or neutrophils are found within the bullae. Perivascular and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils are seen; however, the inflammatory cell infiltrate can vary from extensive to scant. Direct immunofluorescence usually reveals IgG and/or C3 deposition on the surface of the keratinocytes throughout the epidermis.

Pemphigus foliaceus is another autoimmune intraepidermal bullous disease that is characterized by acantholysis in the granular or upper spinous layers (Figure 4).3 The epidermis is not thickened. Sometimes acantholytic cells show dyskeratotic change (Figure 4). Some biopsy specimens do not contain the roof of the bullae; therefore, only erosion is seen and the diagnosis may be missed. Moreover, when only the adnexal epithelium shows acantholysis without epidermal involvement, diagnosis can be difficult.4 Acantholysis is accompanied with a superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, and occasionally neutrophils. The amount of inflammatory cell infiltrate may vary. Bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome reveal a similar histopathologic pattern. Direct immunofluorescence usually discloses IgG and/or C3 deposition on cell surfaces of keratinocytes in the entire or upper epidermis.

Herpesvirus infection shows ballooning (intracellular edema) of keratinocytes. Eventually acantholysis occurs and intraepidermal bullae are formed. In the bullae, virus-associated acantholytic keratinocytes, some that are multinucleated, can be easily found (Figure 5).5 These cells are larger than normal keratinocytes and have steel gray nuclei with peripheral accentuation. Some of these cells are necrotic, and the remains of necrotic multinucleated acantholytic cells are easily recognized. Adnexal epithelial cells occasionally are affected by herpesvirus infection; nuclear change is similar to the epidermis. A perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and neutrophils is seen. Neutrophils accumulate within the old bullae, clinically manifesting as a pustule.

Darier disease is characterized by suprabasal clefts and acantholysis above the basal layer (Figure 6).6 Similar to HHD, villi protrude within the clefts (Figure 6). Conspicuous columns of parakeratosis above the acantholytic epidermis often are observed. Dyskeratotic cells exist among acantholytic ke-ratinocytes in the granular layer and parakeratotic column, which are known as corps ronds and crops grains, respectively. A scant to moderate lymphocytic infiltrate is found in the upper dermis.

- Hernandez-Perez E. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Cutis. 1987;39:75-77.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:373-380, vii.

- Dasher D, Rubenstein D, Diaz LA. Pemphigus foliaceus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2008;10:182-194.

- Ohata C, Akamatsu K, Imai N, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus exclusively involving the follicular infundibulum: a novel peau d’orange appearance. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:392-395.

- King DF, King LA. Giant cells in lesions of varicella and herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:456-458.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

- Hernandez-Perez E. Familial benign chronic pemphigus. Cutis. 1987;39:75-77.

- Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Diagnosis and clinical features of pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:373-380, vii.

- Dasher D, Rubenstein D, Diaz LA. Pemphigus foliaceus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2008;10:182-194.

- Ohata C, Akamatsu K, Imai N, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus exclusively involving the follicular infundibulum: a novel peau d’orange appearance. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:392-395.

- King DF, King LA. Giant cells in lesions of varicella and herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:456-458.

- Burge S. Management of Darier’s disease. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:53-56.

Efficacy, safety seen with transcatheter pulmonary valve

WASHINGTON - A transcatheter pulmonary valve system that provides a new right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit to congenital heart disease patients without the need for open heart surgery performed a little better in a real-world registry at 10 U.S. centers than it had in the pivotal trial that led to the system's 2010 FDA approval.

The new results "confirm the strong performance of the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve achieved by real-world providers with results comparable to the U.S. investigational device exemption [IDE] trial," Dr. Aimee K. Armstrong said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The "high level" of 97% freedom from transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV) dysfunction at 1 year "was better than in the IDE trial," where the level reached 94%, noted Dr. Armstrong of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The registry study, which the FDA mandated when it approved the Melody valve in 2010, ran during July 2010 to July 2012 at 10 U.S. centers that had not participated in the pivotal trial. The 99 patients who received an implant that stayed in place for at least 1 day ranged from 5 to 45 years old, with an average age of 20 years. Although patient follow-up averaged 22 months, the study's primary endpoint was acceptable hemodynamic function within the conduit at 6 months, with a prespecified performance goal of 75% of patients achieving this outcome. The outcome actually occurred in 97% of the 90 evaluable patients at 6 months, and in 88% of all 99 patients who received a conduit. The difference between each of these rates and the performance goal was statistically significant, Dr. Armstrong said.

The transcatheter valve showed excellent performance by other criteria as well. Acceptable hemodynamic function continued through 1 year in 94% of the 87 implanted patients with evaluable data at 12 months, which translated to 83% of the entire 99 patients in the implanted group. Severe or moderate pulmonary valve regurgitation existed in 85% of the patients before treatment; after treatment no patient had severe or moderate regurgitation, and after 1 year 63% had no regurgitation, 24% had trace, and 12% had mild regurgitation (figures total 99% because of rounding). The 1-year rate of 97% of patients free from dysfunction of their implanted valve appeared to surpass the 94% rate seen in the pivotal trial (Circulation 2010;122:507-16).

The results also showed that high right ventricular pressure prior to valve placement was the only variable independently associated with subsequent valve dysfunction. "Patients who go into the procedure with a very stenotic conduit are probably at higher risk for transcatheter pulmonary valve dysfunction down the road," she said.

The study was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve. Dr. Armstrong said she has received research funding from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences.

|

| Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

This study is an important post-approval demonstration that the excellent early results obtained in the original IDE trial in the United States can be reproduced or even exceeded with a broader rollout of the Melody valve to many more centers. The next set of data, which is eagerly anticipated, is the mid-term and longer results for the Melody valve, which will begin to answer questions about the durability of valve competence. Additional information about the performance of the valve in alternative anatomic settings, such as in failing stented bioprostheses - so-called "valve-in-valve" usage - is also beginning to accumulate.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is professor of surgery and pediatrics and chief of pediatric heart surgery at Duke University School of Medicine and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

|

| Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

This study is an important post-approval demonstration that the excellent early results obtained in the original IDE trial in the United States can be reproduced or even exceeded with a broader rollout of the Melody valve to many more centers. The next set of data, which is eagerly anticipated, is the mid-term and longer results for the Melody valve, which will begin to answer questions about the durability of valve competence. Additional information about the performance of the valve in alternative anatomic settings, such as in failing stented bioprostheses - so-called "valve-in-valve" usage - is also beginning to accumulate.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is professor of surgery and pediatrics and chief of pediatric heart surgery at Duke University School of Medicine and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

|

| Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

This study is an important post-approval demonstration that the excellent early results obtained in the original IDE trial in the United States can be reproduced or even exceeded with a broader rollout of the Melody valve to many more centers. The next set of data, which is eagerly anticipated, is the mid-term and longer results for the Melody valve, which will begin to answer questions about the durability of valve competence. Additional information about the performance of the valve in alternative anatomic settings, such as in failing stented bioprostheses - so-called "valve-in-valve" usage - is also beginning to accumulate.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is professor of surgery and pediatrics and chief of pediatric heart surgery at Duke University School of Medicine and an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

WASHINGTON - A transcatheter pulmonary valve system that provides a new right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit to congenital heart disease patients without the need for open heart surgery performed a little better in a real-world registry at 10 U.S. centers than it had in the pivotal trial that led to the system's 2010 FDA approval.

The new results "confirm the strong performance of the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve achieved by real-world providers with results comparable to the U.S. investigational device exemption [IDE] trial," Dr. Aimee K. Armstrong said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The "high level" of 97% freedom from transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV) dysfunction at 1 year "was better than in the IDE trial," where the level reached 94%, noted Dr. Armstrong of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The registry study, which the FDA mandated when it approved the Melody valve in 2010, ran during July 2010 to July 2012 at 10 U.S. centers that had not participated in the pivotal trial. The 99 patients who received an implant that stayed in place for at least 1 day ranged from 5 to 45 years old, with an average age of 20 years. Although patient follow-up averaged 22 months, the study's primary endpoint was acceptable hemodynamic function within the conduit at 6 months, with a prespecified performance goal of 75% of patients achieving this outcome. The outcome actually occurred in 97% of the 90 evaluable patients at 6 months, and in 88% of all 99 patients who received a conduit. The difference between each of these rates and the performance goal was statistically significant, Dr. Armstrong said.

The transcatheter valve showed excellent performance by other criteria as well. Acceptable hemodynamic function continued through 1 year in 94% of the 87 implanted patients with evaluable data at 12 months, which translated to 83% of the entire 99 patients in the implanted group. Severe or moderate pulmonary valve regurgitation existed in 85% of the patients before treatment; after treatment no patient had severe or moderate regurgitation, and after 1 year 63% had no regurgitation, 24% had trace, and 12% had mild regurgitation (figures total 99% because of rounding). The 1-year rate of 97% of patients free from dysfunction of their implanted valve appeared to surpass the 94% rate seen in the pivotal trial (Circulation 2010;122:507-16).

The results also showed that high right ventricular pressure prior to valve placement was the only variable independently associated with subsequent valve dysfunction. "Patients who go into the procedure with a very stenotic conduit are probably at higher risk for transcatheter pulmonary valve dysfunction down the road," she said.

The study was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve. Dr. Armstrong said she has received research funding from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences.

WASHINGTON - A transcatheter pulmonary valve system that provides a new right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit to congenital heart disease patients without the need for open heart surgery performed a little better in a real-world registry at 10 U.S. centers than it had in the pivotal trial that led to the system's 2010 FDA approval.

The new results "confirm the strong performance of the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve achieved by real-world providers with results comparable to the U.S. investigational device exemption [IDE] trial," Dr. Aimee K. Armstrong said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology. The "high level" of 97% freedom from transcatheter pulmonary valve (TPV) dysfunction at 1 year "was better than in the IDE trial," where the level reached 94%, noted Dr. Armstrong of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The registry study, which the FDA mandated when it approved the Melody valve in 2010, ran during July 2010 to July 2012 at 10 U.S. centers that had not participated in the pivotal trial. The 99 patients who received an implant that stayed in place for at least 1 day ranged from 5 to 45 years old, with an average age of 20 years. Although patient follow-up averaged 22 months, the study's primary endpoint was acceptable hemodynamic function within the conduit at 6 months, with a prespecified performance goal of 75% of patients achieving this outcome. The outcome actually occurred in 97% of the 90 evaluable patients at 6 months, and in 88% of all 99 patients who received a conduit. The difference between each of these rates and the performance goal was statistically significant, Dr. Armstrong said.

The transcatheter valve showed excellent performance by other criteria as well. Acceptable hemodynamic function continued through 1 year in 94% of the 87 implanted patients with evaluable data at 12 months, which translated to 83% of the entire 99 patients in the implanted group. Severe or moderate pulmonary valve regurgitation existed in 85% of the patients before treatment; after treatment no patient had severe or moderate regurgitation, and after 1 year 63% had no regurgitation, 24% had trace, and 12% had mild regurgitation (figures total 99% because of rounding). The 1-year rate of 97% of patients free from dysfunction of their implanted valve appeared to surpass the 94% rate seen in the pivotal trial (Circulation 2010;122:507-16).

The results also showed that high right ventricular pressure prior to valve placement was the only variable independently associated with subsequent valve dysfunction. "Patients who go into the procedure with a very stenotic conduit are probably at higher risk for transcatheter pulmonary valve dysfunction down the road," she said.

The study was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve. Dr. Armstrong said she has received research funding from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences.

Key clinical point: The Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve system worked as well in a real world registry as it did in its pivotal trial as a conduit between the right ventricle and pulmonary artery.

Major finding: Acceptable hemodynamic function at 6 months occurred in 88% of implanted patients, significantly surpassing the 75% performance goal.

Data source: A series of 99 patients who received a transcatheter pulmonary valve at any of 10 participating U.S. centers.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Medtronic, which markets the Melody transcatheter pulmonary valve. Dr. Armstrong said that she has received consultant fees and honoraria from Siemens Healthcare and St. Jude Medical, and has received research funding from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences.

Subclinical seizures a risk during cardiac surgery

TORONTO – Routine EEG monitoring after surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in neonates revealed a seizure incidence of 8% in a recent study. In most cases (85%), seizure activity was detectable only on EEG and would not have been identified or treated without EEG monitoring, reported Dr. Maryam Y. Naim, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, during the AATS Annual Meeting.

Of concern, status epilepticus was noted in 62% of neonates with seizures, and mortality was higher in babies with seizures versus those without (38% vs. 3%; P less than .01). "Postoperative seizures are associated with worse neurological outcomes," said Dr. Naim. In addition to being a biomarker of underlying brain injury, there is some evidence that the seizures themselves may cause secondary brain injury.

A total of 161 neonates had 48-hours of EEG monitoring begun within 6 hours of cardiac surgery with CPB. The median gestational age of the cohort was 39 weeks, 16% were premature, and 13% had identified genetic defects. The median age at surgery was 5 days. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used in 48% of surgeries (median time, 48 minutes), 16% had open chest with delayed sternal closure, and 9% had a cardiac arrest.

Seizures were detected in 13 (8%), with a median onset of 20 hours after return to the cardiac ICU (CICU) from surgery. Seizures were subclinical, or EEG only, in 11 patients (85%), electroclinical in the other 2 (15%), and status epilepticus was seen in 8 (62%). When seizures occurred, the patient was treated with antiseizure medications. Abnormal vital signs or movements suggestive of seizure activity were noted at the bedside; although such events were recorded in 32 patients (22%), none had EEG correlates consistent with seizure activity.

"Neonates with all types of heart disease had seizures ... " said Dr. Naim. " ... with a highest percentage occurring in those with single ventricles and arch obstruction."

Neuroimaging studies were reviewed by a neurologist to determine any association between injury and seizure location. Although neonates with and without seizures had similar CICU lengths of stay, mortality was higher in those with seizures (38% vs. 3%; P less than .01). No predictors of seizures were identified on multivariable analysis.

"Based on these data, we are continuing routine postoperative EEG monitoring in all neonates following surgery with CPB," she said.

While not discredited in any way, Dr. Naim’s data were met with a fair amount of pushback from the gathered group of pediatric cardiothoracic surgical experts. An informal poll of the audience showed that 80%-90% do not routinely monitor neonates for seizures post-CPB despite ACNS recommendations, and several of the comments questioned the technical and financial feasibility of routine EEG monitoring.

Said the invited discussant, Dr. Frank Pigula, a cardiac surgeon from Boston Children’s Hospital, "In all the groups that have studied this, in all patients who have had a seizure, there were documented brain abnormalities. So, the ways I picture these data are that a seizure is a sign of an underlying brain injury, much like a fever is a sign of an underlying infection.

"And you’ve made a good case for the routine postoperative surveillance for seizures; I’m sure everyone would agree that treating seizures is a good thing, but is there any evidence showing us that the early identification and treatment of seizures improves outcomes, either developmental delays or mortality?

In response, Dr. Naim noted that all the CHOP seizure sufferers were treated, whether they had EEG only or clinical seizures, and, at the 4-year mark, they are showing fewer neurodevelopmental issues than previous cohorts of untreated neonates.

"I think one thing that is very concerning is emerging evidence that the seizures themselves cause secondary brain injury," she said.

Dr. Naim and Dr. Pigula reported having no financial disclosures.

TORONTO – Routine EEG monitoring after surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass in neonates revealed a seizure incidence of 8% in a recent study. In most cases (85%), seizure activity was detectable only on EEG and would not have been identified or treated without EEG monitoring, reported Dr. Maryam Y. Naim, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, during the AATS Annual Meeting.

Of concern, status epilepticus was noted in 62% of neonates with seizures, and mortality was higher in babies with seizures versus those without (38% vs. 3%; P less than .01). "Postoperative seizures are associated with worse neurological outcomes," said Dr. Naim. In addition to being a biomarker of underlying brain injury, there is some evidence that the seizures themselves may cause secondary brain injury.

A total of 161 neonates had 48-hours of EEG monitoring begun within 6 hours of cardiac surgery with CPB. The median gestational age of the cohort was 39 weeks, 16% were premature, and 13% had identified genetic defects. The median age at surgery was 5 days. Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was used in 48% of surgeries (median time, 48 minutes), 16% had open chest with delayed sternal closure, and 9% had a cardiac arrest.