User login

VIDEO: ‘Improve – but do not abandon – power morcellation’

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Without power morcellation, the number of hysterectomies performed using an open approach would dramatically increase – and the combined mortality from laparoscopic hysterectomy and potential dissemination of leiomyosarcoma would be less than that of open hysterectomy, according to testimony given July 11 at a Food and Drug Administration expert panel meeting.

Dr. Jubilee Brown, director of gynecologic oncology at the Woman's Hospital of Texas, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, testified at the meeting on behalf of the AAGL, an association that promotes minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. She presented results of a decision analysis suggesting that if all U.S. cases were converted to open hysterectomy from laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) with morcellation of fibroids, 17 more women each year would die from the open procedure than from the combination LH and morcellation.

"Improve – but do not abandon – power morcellation," Dr. Brown told the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Advisory Committee. She discussed her testimony during this video interview.

Dr. Brown said she had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Without power morcellation, the number of hysterectomies performed using an open approach would dramatically increase – and the combined mortality from laparoscopic hysterectomy and potential dissemination of leiomyosarcoma would be less than that of open hysterectomy, according to testimony given July 11 at a Food and Drug Administration expert panel meeting.

Dr. Jubilee Brown, director of gynecologic oncology at the Woman's Hospital of Texas, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, testified at the meeting on behalf of the AAGL, an association that promotes minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. She presented results of a decision analysis suggesting that if all U.S. cases were converted to open hysterectomy from laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) with morcellation of fibroids, 17 more women each year would die from the open procedure than from the combination LH and morcellation.

"Improve – but do not abandon – power morcellation," Dr. Brown told the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Advisory Committee. She discussed her testimony during this video interview.

Dr. Brown said she had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Without power morcellation, the number of hysterectomies performed using an open approach would dramatically increase – and the combined mortality from laparoscopic hysterectomy and potential dissemination of leiomyosarcoma would be less than that of open hysterectomy, according to testimony given July 11 at a Food and Drug Administration expert panel meeting.

Dr. Jubilee Brown, director of gynecologic oncology at the Woman's Hospital of Texas, University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, testified at the meeting on behalf of the AAGL, an association that promotes minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. She presented results of a decision analysis suggesting that if all U.S. cases were converted to open hysterectomy from laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH) with morcellation of fibroids, 17 more women each year would die from the open procedure than from the combination LH and morcellation.

"Improve – but do not abandon – power morcellation," Dr. Brown told the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Advisory Committee. She discussed her testimony during this video interview.

Dr. Brown said she had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

Rethinking antimicrobial prophylaxis for UTI

The RIVUR [Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux] trial investigators set out to reevaluate the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrences in children with vesicoureteral reflux. As recent randomized trials have produced conflicting results, the goal of the RIVUR investigators was to determine whether antimicrobial prophylaxis could prevent febrile or symptomatic urinary tract infection and whether prevention would reduce the likelihood of subsequent renal scarring. The results, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2014;370:2367-76), demonstrated that nearly 18% of children, 2 months to 6 years of age, have a febrile or symptomatic recurrence within the first year after the initial or presenting episode. The recurrence rate for febrile or symptomatic episodes was reduced by approximately 50% in the treatment group (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) to nearly 8%.

In addition, the proportion of children considered treatment failures (defined as a combination of febrile or symptomatic UTIs or development of new renal scarring) occurred twice as often in the placebo group as in the treatment group. However, despite the reduction in febrile or symptomatic episodes in the treatment group, approximately 8% of children in both treatment and placebo groups developed new renal scarring, as defined by a decreased uptake of tracer or cortical thinning.

The study confirmed that children with higher grades of reflux (III or IV at baseline) were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, that children with bladder and bowel dysfunction (based on a modified Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score) also were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, and that recurrences in children on prophylaxis were more likely to be resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole than were those in children on placebo.

Implications for prevention of UTI

The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the management of UTI in children were updated in 2011 (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610). The authors contacted the six researchers who had conducted the most recent randomized controlled trials and completed a formal meta-analysis that did not detect a statistically significant benefit of prophylaxis for stopping the recurrence of febrile UTI/pyelonephritis in infants without reflux or those with grades I, II, III, or IV. The 2011 recommendations reflected the findings of an AAP subcommittee that antimicrobial prophylaxis was not effective, as had been presumed in a 1999 report (Pediatrics 1999;103:843-52).

The AAP subcommittee on urinary tract infection of the Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management – authors of the 2011 revised guidelines – have recently reviewed the RIVUR study data (AAP News, July 1 2014) and concluded that antimicrobial prophylaxis did not alter the development of new renal scarring/damage, that the benefits of daily antimicrobial prophylaxis were modest, and that the increased likelihood of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at recurrences was significant. The subcommittee reaffirmed the 2011 guidance concerning a "less aggressive" approach: Renal and bladder ultrasound are adequate for assessment of risk for renal scarring at first episodes, and watchful waiting without performing voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) or initiating prophylaxis is appropriate. VCUG is indicated after a first episode if renal and bladder ultrasonography reveals hydronephrosis, scarring, or other findings that would suggest either high-grade vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or obstructive uropathy and in other atypical or complex clinical circumstances. As well, VCUG also should be performed if there is a recurrence of a febrile UTI (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610).

The current subcommittee opined that prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of a febrile UTI recurrence may be of greater importance, regardless of whether VUR is present or the child is receiving antimicrobial prophylaxis.

My take

For me, the RIVUR data provide further insights into both the risk of any recurrence (approximately 18% by 12 months, approximately 25% by 24 months) and the risk for multiple recurrences (approximately 10%). The data identify those at highest risk for recurrences (patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction or higher grades of reflux) and provide evidence that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis is highly effective in such groups. No serious side effects were observed during the RIVUR trial; however, Stevens-Johnson syndrome is documented to occur rarely after administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the potential for this life-threatening event should be part of the decision process. I believe the value of the new data is that they provide confidence that antimicrobial prophylaxis can be effective for the prevention of febrile/symptomatic UTI, and that in select children at great risk for recurrences and subsequent renal damage, antimicrobial prophylaxis can be part of our toolbox.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The RIVUR [Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux] trial investigators set out to reevaluate the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrences in children with vesicoureteral reflux. As recent randomized trials have produced conflicting results, the goal of the RIVUR investigators was to determine whether antimicrobial prophylaxis could prevent febrile or symptomatic urinary tract infection and whether prevention would reduce the likelihood of subsequent renal scarring. The results, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2014;370:2367-76), demonstrated that nearly 18% of children, 2 months to 6 years of age, have a febrile or symptomatic recurrence within the first year after the initial or presenting episode. The recurrence rate for febrile or symptomatic episodes was reduced by approximately 50% in the treatment group (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) to nearly 8%.

In addition, the proportion of children considered treatment failures (defined as a combination of febrile or symptomatic UTIs or development of new renal scarring) occurred twice as often in the placebo group as in the treatment group. However, despite the reduction in febrile or symptomatic episodes in the treatment group, approximately 8% of children in both treatment and placebo groups developed new renal scarring, as defined by a decreased uptake of tracer or cortical thinning.

The study confirmed that children with higher grades of reflux (III or IV at baseline) were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, that children with bladder and bowel dysfunction (based on a modified Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score) also were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, and that recurrences in children on prophylaxis were more likely to be resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole than were those in children on placebo.

Implications for prevention of UTI

The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the management of UTI in children were updated in 2011 (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610). The authors contacted the six researchers who had conducted the most recent randomized controlled trials and completed a formal meta-analysis that did not detect a statistically significant benefit of prophylaxis for stopping the recurrence of febrile UTI/pyelonephritis in infants without reflux or those with grades I, II, III, or IV. The 2011 recommendations reflected the findings of an AAP subcommittee that antimicrobial prophylaxis was not effective, as had been presumed in a 1999 report (Pediatrics 1999;103:843-52).

The AAP subcommittee on urinary tract infection of the Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management – authors of the 2011 revised guidelines – have recently reviewed the RIVUR study data (AAP News, July 1 2014) and concluded that antimicrobial prophylaxis did not alter the development of new renal scarring/damage, that the benefits of daily antimicrobial prophylaxis were modest, and that the increased likelihood of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at recurrences was significant. The subcommittee reaffirmed the 2011 guidance concerning a "less aggressive" approach: Renal and bladder ultrasound are adequate for assessment of risk for renal scarring at first episodes, and watchful waiting without performing voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) or initiating prophylaxis is appropriate. VCUG is indicated after a first episode if renal and bladder ultrasonography reveals hydronephrosis, scarring, or other findings that would suggest either high-grade vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or obstructive uropathy and in other atypical or complex clinical circumstances. As well, VCUG also should be performed if there is a recurrence of a febrile UTI (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610).

The current subcommittee opined that prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of a febrile UTI recurrence may be of greater importance, regardless of whether VUR is present or the child is receiving antimicrobial prophylaxis.

My take

For me, the RIVUR data provide further insights into both the risk of any recurrence (approximately 18% by 12 months, approximately 25% by 24 months) and the risk for multiple recurrences (approximately 10%). The data identify those at highest risk for recurrences (patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction or higher grades of reflux) and provide evidence that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis is highly effective in such groups. No serious side effects were observed during the RIVUR trial; however, Stevens-Johnson syndrome is documented to occur rarely after administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the potential for this life-threatening event should be part of the decision process. I believe the value of the new data is that they provide confidence that antimicrobial prophylaxis can be effective for the prevention of febrile/symptomatic UTI, and that in select children at great risk for recurrences and subsequent renal damage, antimicrobial prophylaxis can be part of our toolbox.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The RIVUR [Randomized Intervention for Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux] trial investigators set out to reevaluate the role of antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrences in children with vesicoureteral reflux. As recent randomized trials have produced conflicting results, the goal of the RIVUR investigators was to determine whether antimicrobial prophylaxis could prevent febrile or symptomatic urinary tract infection and whether prevention would reduce the likelihood of subsequent renal scarring. The results, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2014;370:2367-76), demonstrated that nearly 18% of children, 2 months to 6 years of age, have a febrile or symptomatic recurrence within the first year after the initial or presenting episode. The recurrence rate for febrile or symptomatic episodes was reduced by approximately 50% in the treatment group (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) to nearly 8%.

In addition, the proportion of children considered treatment failures (defined as a combination of febrile or symptomatic UTIs or development of new renal scarring) occurred twice as often in the placebo group as in the treatment group. However, despite the reduction in febrile or symptomatic episodes in the treatment group, approximately 8% of children in both treatment and placebo groups developed new renal scarring, as defined by a decreased uptake of tracer or cortical thinning.

The study confirmed that children with higher grades of reflux (III or IV at baseline) were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, that children with bladder and bowel dysfunction (based on a modified Dysfunctional Voiding Symptom Score) also were more likely to have febrile or symptomatic recurrences, and that recurrences in children on prophylaxis were more likely to be resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole than were those in children on placebo.

Implications for prevention of UTI

The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the management of UTI in children were updated in 2011 (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610). The authors contacted the six researchers who had conducted the most recent randomized controlled trials and completed a formal meta-analysis that did not detect a statistically significant benefit of prophylaxis for stopping the recurrence of febrile UTI/pyelonephritis in infants without reflux or those with grades I, II, III, or IV. The 2011 recommendations reflected the findings of an AAP subcommittee that antimicrobial prophylaxis was not effective, as had been presumed in a 1999 report (Pediatrics 1999;103:843-52).

The AAP subcommittee on urinary tract infection of the Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management – authors of the 2011 revised guidelines – have recently reviewed the RIVUR study data (AAP News, July 1 2014) and concluded that antimicrobial prophylaxis did not alter the development of new renal scarring/damage, that the benefits of daily antimicrobial prophylaxis were modest, and that the increased likelihood of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole at recurrences was significant. The subcommittee reaffirmed the 2011 guidance concerning a "less aggressive" approach: Renal and bladder ultrasound are adequate for assessment of risk for renal scarring at first episodes, and watchful waiting without performing voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) or initiating prophylaxis is appropriate. VCUG is indicated after a first episode if renal and bladder ultrasonography reveals hydronephrosis, scarring, or other findings that would suggest either high-grade vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or obstructive uropathy and in other atypical or complex clinical circumstances. As well, VCUG also should be performed if there is a recurrence of a febrile UTI (Pediatrics 2011;128:595-610).

The current subcommittee opined that prompt diagnosis and effective treatment of a febrile UTI recurrence may be of greater importance, regardless of whether VUR is present or the child is receiving antimicrobial prophylaxis.

My take

For me, the RIVUR data provide further insights into both the risk of any recurrence (approximately 18% by 12 months, approximately 25% by 24 months) and the risk for multiple recurrences (approximately 10%). The data identify those at highest risk for recurrences (patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction or higher grades of reflux) and provide evidence that trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis is highly effective in such groups. No serious side effects were observed during the RIVUR trial; however, Stevens-Johnson syndrome is documented to occur rarely after administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the potential for this life-threatening event should be part of the decision process. I believe the value of the new data is that they provide confidence that antimicrobial prophylaxis can be effective for the prevention of febrile/symptomatic UTI, and that in select children at great risk for recurrences and subsequent renal damage, antimicrobial prophylaxis can be part of our toolbox.

Dr. Pelton is chief of pediatric infectious disease and coordinator of the maternal-child HIV program at Boston Medical Center. He said that he had no relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Public testimony gets heated at FDA panel meeting on morcellation

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Power morcellation devices should be never used for gynecologic procedures, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm testified to a Food and Drug Administration expert panel on July ll.

He called out members of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee by name, seeking to shame them into action to disallow power morcellation for suspected uterine fibroids.

"Is this a safe and logical device?" said Dr. Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. "The only classification for this device is banned – unsafe, illogical, incorrect, and deadly."

Dr. Noorchashm’s wife, Dr. Amy Reed, had a hysterectomy with morcellation for suspected fibroids. Biopsy later confirmed sarcoma was present. Use of power morcellation caused tumor cells to spread, upstaging her sarcoma to stage IV.

On Twitter @denisefulton

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Power morcellation devices should be never used for gynecologic procedures, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm testified to a Food and Drug Administration expert panel on July ll.

He called out members of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee by name, seeking to shame them into action to disallow power morcellation for suspected uterine fibroids.

"Is this a safe and logical device?" said Dr. Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. "The only classification for this device is banned – unsafe, illogical, incorrect, and deadly."

Dr. Noorchashm’s wife, Dr. Amy Reed, had a hysterectomy with morcellation for suspected fibroids. Biopsy later confirmed sarcoma was present. Use of power morcellation caused tumor cells to spread, upstaging her sarcoma to stage IV.

On Twitter @denisefulton

SILVER SPRING, MD. – Power morcellation devices should be never used for gynecologic procedures, Dr. Hooman Noorchashm testified to a Food and Drug Administration expert panel on July ll.

He called out members of the FDA Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel Advisory Committee by name, seeking to shame them into action to disallow power morcellation for suspected uterine fibroids.

"Is this a safe and logical device?" said Dr. Noorchashm, a cardiothoracic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. "The only classification for this device is banned – unsafe, illogical, incorrect, and deadly."

Dr. Noorchashm’s wife, Dr. Amy Reed, had a hysterectomy with morcellation for suspected fibroids. Biopsy later confirmed sarcoma was present. Use of power morcellation caused tumor cells to spread, upstaging her sarcoma to stage IV.

On Twitter @denisefulton

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

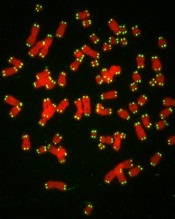

Gene editing doesn’t increase mutations in iPSCs

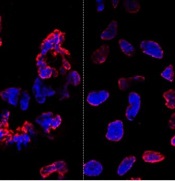

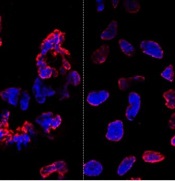

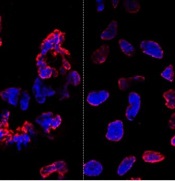

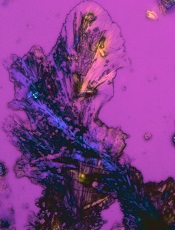

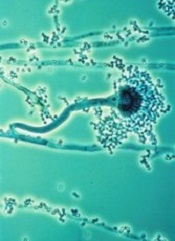

misshapen nuclear envelopes

(red) from iPSCs (DNA in blue).

The right panel shows

gene-edited iPSCs.

Credit: Salk Institute

Results of new research may ease previous concerns that gene-editing techniques could add unwanted mutations to stem cells.

Researchers compared gene editing techniques in lines of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD).

And they found that neither viral nor nuclease-based gene-editing methods increased the frequency of mutations in the iPSCs.

The team reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“The ability to precisely modify the DNA of stem cells has greatly accelerated research on human diseases and cell therapy,” said senior study author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, PhD, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“To successfully translate this technology into the clinic, we first need to scrutinize the safety of these modified stem cells, such as their genome stability and mutational load.”

Previously, Dr Belmonte’s lab pioneered the use of modified viruses, called helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HDAdVs), to correct the genetic mutation that causes SCD.

He and his colleagues used HDAdVs to replace the mutated gene in a line of iPSCs with a mutant-free version, creating stem cells that could, theoretically, be infused into patients’ bone marrow and help create healthy blood cells.

Before such technologies are applied to humans, though, Dr Belmonte and his colleagues wanted to know whether there were risks related to editing the genes in iPSCs.

“As cells are being reprogrammed into stem cells, they tend to accumulate many mutations,” said Mo Li, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“So people naturally worry that any process you perform with these cells in vitro—including gene editing—might generate even more mutations.”

To find out whether this was the case, the researchers conducted tests in a line of SCD-derived iPSCs.

They edited the genes of some cells using 1 of 2 HDAdV designs. And they edited others using 1 of 2 transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) proteins.

They kept the rest of the SCD iPSCs in culture without editing them. Then, the team sequenced the entire genome of each cell from the 4 edits and control experiment.

While all of the cells gained a low level of random gene mutations during the experiments, the cells that had undergone gene-editing—whether through HDAdV- or TALEN-based approaches—had no more mutations than the cells kept in culture.

“We were pleasantly surprised by the results,” said Keiichiro Suzuki, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“People have found thousands of mutations introduced during iPSC reprogramming. We found less than a hundred single nucleotide variants in all cases.”

The researchers noted that this finding doesn’t necessarily mean there are no inherent risks to using stem cells with edited genes. However, it does suggest the editing process doesn’t make iPSCs any less safe.

“We concluded that the risk of mutation isn’t inherently connected to gene editing,” Dr Li said. “These cells present the same risks as using any other cells manipulated for cell or gene therapy.”

The Belmonte group is now planning more studies to address whether gene-repair in other cell types, using other approaches, or targeting other genes could be more or less likely to cause unwanted mutations.

For now, they hope their findings encourage those in the field to keep pursuing gene-editing techniques as a potential way to treat genetic diseases in the future. ![]()

misshapen nuclear envelopes

(red) from iPSCs (DNA in blue).

The right panel shows

gene-edited iPSCs.

Credit: Salk Institute

Results of new research may ease previous concerns that gene-editing techniques could add unwanted mutations to stem cells.

Researchers compared gene editing techniques in lines of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD).

And they found that neither viral nor nuclease-based gene-editing methods increased the frequency of mutations in the iPSCs.

The team reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“The ability to precisely modify the DNA of stem cells has greatly accelerated research on human diseases and cell therapy,” said senior study author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, PhD, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“To successfully translate this technology into the clinic, we first need to scrutinize the safety of these modified stem cells, such as their genome stability and mutational load.”

Previously, Dr Belmonte’s lab pioneered the use of modified viruses, called helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HDAdVs), to correct the genetic mutation that causes SCD.

He and his colleagues used HDAdVs to replace the mutated gene in a line of iPSCs with a mutant-free version, creating stem cells that could, theoretically, be infused into patients’ bone marrow and help create healthy blood cells.

Before such technologies are applied to humans, though, Dr Belmonte and his colleagues wanted to know whether there were risks related to editing the genes in iPSCs.

“As cells are being reprogrammed into stem cells, they tend to accumulate many mutations,” said Mo Li, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“So people naturally worry that any process you perform with these cells in vitro—including gene editing—might generate even more mutations.”

To find out whether this was the case, the researchers conducted tests in a line of SCD-derived iPSCs.

They edited the genes of some cells using 1 of 2 HDAdV designs. And they edited others using 1 of 2 transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) proteins.

They kept the rest of the SCD iPSCs in culture without editing them. Then, the team sequenced the entire genome of each cell from the 4 edits and control experiment.

While all of the cells gained a low level of random gene mutations during the experiments, the cells that had undergone gene-editing—whether through HDAdV- or TALEN-based approaches—had no more mutations than the cells kept in culture.

“We were pleasantly surprised by the results,” said Keiichiro Suzuki, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“People have found thousands of mutations introduced during iPSC reprogramming. We found less than a hundred single nucleotide variants in all cases.”

The researchers noted that this finding doesn’t necessarily mean there are no inherent risks to using stem cells with edited genes. However, it does suggest the editing process doesn’t make iPSCs any less safe.

“We concluded that the risk of mutation isn’t inherently connected to gene editing,” Dr Li said. “These cells present the same risks as using any other cells manipulated for cell or gene therapy.”

The Belmonte group is now planning more studies to address whether gene-repair in other cell types, using other approaches, or targeting other genes could be more or less likely to cause unwanted mutations.

For now, they hope their findings encourage those in the field to keep pursuing gene-editing techniques as a potential way to treat genetic diseases in the future. ![]()

misshapen nuclear envelopes

(red) from iPSCs (DNA in blue).

The right panel shows

gene-edited iPSCs.

Credit: Salk Institute

Results of new research may ease previous concerns that gene-editing techniques could add unwanted mutations to stem cells.

Researchers compared gene editing techniques in lines of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from a patient with sickle cell disease (SCD).

And they found that neither viral nor nuclease-based gene-editing methods increased the frequency of mutations in the iPSCs.

The team reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“The ability to precisely modify the DNA of stem cells has greatly accelerated research on human diseases and cell therapy,” said senior study author Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte, PhD, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“To successfully translate this technology into the clinic, we first need to scrutinize the safety of these modified stem cells, such as their genome stability and mutational load.”

Previously, Dr Belmonte’s lab pioneered the use of modified viruses, called helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HDAdVs), to correct the genetic mutation that causes SCD.

He and his colleagues used HDAdVs to replace the mutated gene in a line of iPSCs with a mutant-free version, creating stem cells that could, theoretically, be infused into patients’ bone marrow and help create healthy blood cells.

Before such technologies are applied to humans, though, Dr Belmonte and his colleagues wanted to know whether there were risks related to editing the genes in iPSCs.

“As cells are being reprogrammed into stem cells, they tend to accumulate many mutations,” said Mo Li, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“So people naturally worry that any process you perform with these cells in vitro—including gene editing—might generate even more mutations.”

To find out whether this was the case, the researchers conducted tests in a line of SCD-derived iPSCs.

They edited the genes of some cells using 1 of 2 HDAdV designs. And they edited others using 1 of 2 transcription activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN) proteins.

They kept the rest of the SCD iPSCs in culture without editing them. Then, the team sequenced the entire genome of each cell from the 4 edits and control experiment.

While all of the cells gained a low level of random gene mutations during the experiments, the cells that had undergone gene-editing—whether through HDAdV- or TALEN-based approaches—had no more mutations than the cells kept in culture.

“We were pleasantly surprised by the results,” said Keiichiro Suzuki, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Dr Belmonte’s lab.

“People have found thousands of mutations introduced during iPSC reprogramming. We found less than a hundred single nucleotide variants in all cases.”

The researchers noted that this finding doesn’t necessarily mean there are no inherent risks to using stem cells with edited genes. However, it does suggest the editing process doesn’t make iPSCs any less safe.

“We concluded that the risk of mutation isn’t inherently connected to gene editing,” Dr Li said. “These cells present the same risks as using any other cells manipulated for cell or gene therapy.”

The Belmonte group is now planning more studies to address whether gene-repair in other cell types, using other approaches, or targeting other genes could be more or less likely to cause unwanted mutations.

For now, they hope their findings encourage those in the field to keep pursuing gene-editing techniques as a potential way to treat genetic diseases in the future. ![]()

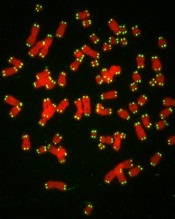

Telomeres can help predict prognosis in CLL

with telomeres in green

Credit: Claus Azzalin

Measuring the length and function of telomeres can help us predict prognosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Investigators found that CLL patients with short, dysfunctional telomeres had a considerably poorer clinical outcome than those with long, functional telomeres.

“For the first time, confident predictions of clinical outcome can be made for individual CLL patients at diagnosis based on accurate analysis of the length of telomeres in cancer cells,” said Chris Pepper, PhD, who led the research at Cardiff University’s School of Medicine in the UK.

“This should prove enormously valuable to doctors, patients, and their families, and there is no reason why there should not be widespread implementation of this powerful prognostic tool in the near future.”

CLL progression is known to be sped up by the loss of telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes and protect them from damage when a cell divides. Every time a cell divides, telomeres get shorter.

When they become too short in a healthy cell, signals are sent to instruct the cell to stop dividing and die. But this “safety check” does not occur in CLL cells. Telomeres become so short that chromosomes are left exposed and are prone to fusing together during cell division, causing even larger DNA faults and even greater instability.

So Dr Pepper and his colleagues set out to identify the telomere length at which fusions start to occur in CLL patients.

The team measured telomeres in patient samples using single telomere length analysis (STELA) along with an experimentally derived definition of telomere dysfunction. They defined the upper telomere length threshold at which telomere fusions occur and used the mean of the telomere “fusogenic” range as a prognostic tool.

The researchers first analyzed samples from 200 CLL patients and found that patients with telomeres below the fusogenic mean had significantly shorter overall survival than patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean (hazard ratio [HR]=13.2, P<0.0001). This was also true for patients with early stage disease (HR=19.3, P<0.0001).

The investigators confirmed this association by analyzing samples from an additional 121 CLL patients. The prognostic impact of telomere dysfunction was evident in the entire cohort (HR=7.4, P<0.0001) and among patients classified as Binet stage A (HR=8.9, P<0.0001).

The researchers also found they could use telomere dysfunction to accurately classify Binet stage A patients into an indolent disease group and a poor prognostic group. At 10 years, the survival rate was 91% in the favorable prognostic group and 13% in the poor prognostic group.

Of note, patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean had superior prognosis regardless of their IGHV mutation status or cytogenetic risk group. And in a multivariate analysis, the telomere fusogenic mean was associated with the highest hazard of progression and death, independent of all other biomarkers.

“The accuracy of this test in predicting how a person’s disease will develop is unprecedented and, if confirmed in clinical trials, would help doctors decide on the best treatment courses for individual CLL patients,” said Matt Kaiser, PhD, Head of Research at Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research, which funded this study.

“Telomeres are known to play a part in the progress of other forms of cancer, so this type of testing could have far-reaching benefits.” ![]()

with telomeres in green

Credit: Claus Azzalin

Measuring the length and function of telomeres can help us predict prognosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Investigators found that CLL patients with short, dysfunctional telomeres had a considerably poorer clinical outcome than those with long, functional telomeres.

“For the first time, confident predictions of clinical outcome can be made for individual CLL patients at diagnosis based on accurate analysis of the length of telomeres in cancer cells,” said Chris Pepper, PhD, who led the research at Cardiff University’s School of Medicine in the UK.

“This should prove enormously valuable to doctors, patients, and their families, and there is no reason why there should not be widespread implementation of this powerful prognostic tool in the near future.”

CLL progression is known to be sped up by the loss of telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes and protect them from damage when a cell divides. Every time a cell divides, telomeres get shorter.

When they become too short in a healthy cell, signals are sent to instruct the cell to stop dividing and die. But this “safety check” does not occur in CLL cells. Telomeres become so short that chromosomes are left exposed and are prone to fusing together during cell division, causing even larger DNA faults and even greater instability.

So Dr Pepper and his colleagues set out to identify the telomere length at which fusions start to occur in CLL patients.

The team measured telomeres in patient samples using single telomere length analysis (STELA) along with an experimentally derived definition of telomere dysfunction. They defined the upper telomere length threshold at which telomere fusions occur and used the mean of the telomere “fusogenic” range as a prognostic tool.

The researchers first analyzed samples from 200 CLL patients and found that patients with telomeres below the fusogenic mean had significantly shorter overall survival than patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean (hazard ratio [HR]=13.2, P<0.0001). This was also true for patients with early stage disease (HR=19.3, P<0.0001).

The investigators confirmed this association by analyzing samples from an additional 121 CLL patients. The prognostic impact of telomere dysfunction was evident in the entire cohort (HR=7.4, P<0.0001) and among patients classified as Binet stage A (HR=8.9, P<0.0001).

The researchers also found they could use telomere dysfunction to accurately classify Binet stage A patients into an indolent disease group and a poor prognostic group. At 10 years, the survival rate was 91% in the favorable prognostic group and 13% in the poor prognostic group.

Of note, patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean had superior prognosis regardless of their IGHV mutation status or cytogenetic risk group. And in a multivariate analysis, the telomere fusogenic mean was associated with the highest hazard of progression and death, independent of all other biomarkers.

“The accuracy of this test in predicting how a person’s disease will develop is unprecedented and, if confirmed in clinical trials, would help doctors decide on the best treatment courses for individual CLL patients,” said Matt Kaiser, PhD, Head of Research at Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research, which funded this study.

“Telomeres are known to play a part in the progress of other forms of cancer, so this type of testing could have far-reaching benefits.” ![]()

with telomeres in green

Credit: Claus Azzalin

Measuring the length and function of telomeres can help us predict prognosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to research published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Investigators found that CLL patients with short, dysfunctional telomeres had a considerably poorer clinical outcome than those with long, functional telomeres.

“For the first time, confident predictions of clinical outcome can be made for individual CLL patients at diagnosis based on accurate analysis of the length of telomeres in cancer cells,” said Chris Pepper, PhD, who led the research at Cardiff University’s School of Medicine in the UK.

“This should prove enormously valuable to doctors, patients, and their families, and there is no reason why there should not be widespread implementation of this powerful prognostic tool in the near future.”

CLL progression is known to be sped up by the loss of telomeres, which cap the ends of chromosomes and protect them from damage when a cell divides. Every time a cell divides, telomeres get shorter.

When they become too short in a healthy cell, signals are sent to instruct the cell to stop dividing and die. But this “safety check” does not occur in CLL cells. Telomeres become so short that chromosomes are left exposed and are prone to fusing together during cell division, causing even larger DNA faults and even greater instability.

So Dr Pepper and his colleagues set out to identify the telomere length at which fusions start to occur in CLL patients.

The team measured telomeres in patient samples using single telomere length analysis (STELA) along with an experimentally derived definition of telomere dysfunction. They defined the upper telomere length threshold at which telomere fusions occur and used the mean of the telomere “fusogenic” range as a prognostic tool.

The researchers first analyzed samples from 200 CLL patients and found that patients with telomeres below the fusogenic mean had significantly shorter overall survival than patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean (hazard ratio [HR]=13.2, P<0.0001). This was also true for patients with early stage disease (HR=19.3, P<0.0001).

The investigators confirmed this association by analyzing samples from an additional 121 CLL patients. The prognostic impact of telomere dysfunction was evident in the entire cohort (HR=7.4, P<0.0001) and among patients classified as Binet stage A (HR=8.9, P<0.0001).

The researchers also found they could use telomere dysfunction to accurately classify Binet stage A patients into an indolent disease group and a poor prognostic group. At 10 years, the survival rate was 91% in the favorable prognostic group and 13% in the poor prognostic group.

Of note, patients with telomeres above the fusogenic mean had superior prognosis regardless of their IGHV mutation status or cytogenetic risk group. And in a multivariate analysis, the telomere fusogenic mean was associated with the highest hazard of progression and death, independent of all other biomarkers.

“The accuracy of this test in predicting how a person’s disease will develop is unprecedented and, if confirmed in clinical trials, would help doctors decide on the best treatment courses for individual CLL patients,” said Matt Kaiser, PhD, Head of Research at Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research, which funded this study.

“Telomeres are known to play a part in the progress of other forms of cancer, so this type of testing could have far-reaching benefits.” ![]()

Immune function after trauma and transfusion

Credit: Graham Colm

An immune marker may help predict which child trauma patients are likely to develop a hospital-acquired infection, and it may also provide new insight into immune response following transfusion.

In a small study, blood samples from critically ill children showed decreased production of TNF-alpha, a cytokine that’s part of the first line of defense in the innate immune system, when compared to samples from healthy control children.

In addition, TNF-alpha production was lower among children who received transfusions with older blood, compared to children who received fresher blood.

Mark W. Hall, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Shock.

The researchers had collected blood samples from 21 healthy children and 76 critically injured children aged 18 years or younger. The team then exposed each sample to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a known stimulant of the immune response. When healthy cells are exposed to LPS, it prompts the production of TNF-alpha.

When they analyzed the immune response, the researchers found that blood samples from the healthy children responded normally to LPS, producing high levels of TNF-alpha.

Samples from the patients with critical injuries all showed at least a moderate decrease in the production of TNF-alpha. But the children who went on to develop an infection showed a much more severe and persistent drop in TNF-alpha following injury.

While the findings strongly suggest that infection risk is associated with immune system function after critical injury, they don’t explain what’s causing the malfunction. Dr Hall’s team is investigating that question now.

Transfusion implications

The research also highlighted another issue that may affect the immune response in critical illness. The team found that patients who received a transfusion of blood stored for more than 2 weeks had a lower level of TNF-alpha production than kids whose transfused blood was less than 2 weeks old, regardless of the severity of their original injury.

This supports a study published by Dr Hall and his colleagues in 2012 in Transfusion. The study showed the same immunosuppressive effect in a human cell culture model.

Dr Hall plans to look into this further through his work with a multi-institutional effort called The Pediatric Critical Care Blood Research Network (BloodNet). The group is studying, among other things, what impact blood transfusions have on immune function.

“There’s a whole line of research in which we’re involved that is dedicated to understanding the effects of transfusion in critical illness,” he said. “It’s not clear yet if blood transfusions are immunosuppressive, but our work so far suggests that blood becomes more immunosuppressive the longer it sits on the shelf.”

Reversing immunosuppression

Yet another element to the study involves reversing the immunosuppression that follows critical injury or illness. The researchers took 3 blood samples in which TNF-alpha production was decreased and cultured them with GM-CSF.

Once treated, the cells began to produce normal levels of TNF-alpha—an indication that the immunosuppression had been reversed.

Dr Hall is now leading a phase 4 clinical trial of GM-CSF to reverse immunosuppression in critically injured patients aged 1 to 21 years old.

Although findings from that project won’t be ready for another year or so, the results in the Shock article seem to offer yet another weapon in physicians’ arsenal when caring for critically ill and injured children, Dr Hall said.

“We have certainly made headway in reducing preventable infections through programs such as our own Zero Hero initiative,” he noted.

“But what this paper suggests is that it’s also important to consider the patient’s immune system and how well they are able to fight off infection. We believe that critical illness- and injury-related immune suppression may be reversible with beneficial effects on clinical outcomes.” ![]()

Credit: Graham Colm

An immune marker may help predict which child trauma patients are likely to develop a hospital-acquired infection, and it may also provide new insight into immune response following transfusion.

In a small study, blood samples from critically ill children showed decreased production of TNF-alpha, a cytokine that’s part of the first line of defense in the innate immune system, when compared to samples from healthy control children.

In addition, TNF-alpha production was lower among children who received transfusions with older blood, compared to children who received fresher blood.

Mark W. Hall, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Shock.

The researchers had collected blood samples from 21 healthy children and 76 critically injured children aged 18 years or younger. The team then exposed each sample to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a known stimulant of the immune response. When healthy cells are exposed to LPS, it prompts the production of TNF-alpha.

When they analyzed the immune response, the researchers found that blood samples from the healthy children responded normally to LPS, producing high levels of TNF-alpha.

Samples from the patients with critical injuries all showed at least a moderate decrease in the production of TNF-alpha. But the children who went on to develop an infection showed a much more severe and persistent drop in TNF-alpha following injury.

While the findings strongly suggest that infection risk is associated with immune system function after critical injury, they don’t explain what’s causing the malfunction. Dr Hall’s team is investigating that question now.

Transfusion implications

The research also highlighted another issue that may affect the immune response in critical illness. The team found that patients who received a transfusion of blood stored for more than 2 weeks had a lower level of TNF-alpha production than kids whose transfused blood was less than 2 weeks old, regardless of the severity of their original injury.

This supports a study published by Dr Hall and his colleagues in 2012 in Transfusion. The study showed the same immunosuppressive effect in a human cell culture model.

Dr Hall plans to look into this further through his work with a multi-institutional effort called The Pediatric Critical Care Blood Research Network (BloodNet). The group is studying, among other things, what impact blood transfusions have on immune function.

“There’s a whole line of research in which we’re involved that is dedicated to understanding the effects of transfusion in critical illness,” he said. “It’s not clear yet if blood transfusions are immunosuppressive, but our work so far suggests that blood becomes more immunosuppressive the longer it sits on the shelf.”

Reversing immunosuppression

Yet another element to the study involves reversing the immunosuppression that follows critical injury or illness. The researchers took 3 blood samples in which TNF-alpha production was decreased and cultured them with GM-CSF.

Once treated, the cells began to produce normal levels of TNF-alpha—an indication that the immunosuppression had been reversed.

Dr Hall is now leading a phase 4 clinical trial of GM-CSF to reverse immunosuppression in critically injured patients aged 1 to 21 years old.

Although findings from that project won’t be ready for another year or so, the results in the Shock article seem to offer yet another weapon in physicians’ arsenal when caring for critically ill and injured children, Dr Hall said.

“We have certainly made headway in reducing preventable infections through programs such as our own Zero Hero initiative,” he noted.

“But what this paper suggests is that it’s also important to consider the patient’s immune system and how well they are able to fight off infection. We believe that critical illness- and injury-related immune suppression may be reversible with beneficial effects on clinical outcomes.” ![]()

Credit: Graham Colm

An immune marker may help predict which child trauma patients are likely to develop a hospital-acquired infection, and it may also provide new insight into immune response following transfusion.

In a small study, blood samples from critically ill children showed decreased production of TNF-alpha, a cytokine that’s part of the first line of defense in the innate immune system, when compared to samples from healthy control children.

In addition, TNF-alpha production was lower among children who received transfusions with older blood, compared to children who received fresher blood.

Mark W. Hall, MD, of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Shock.

The researchers had collected blood samples from 21 healthy children and 76 critically injured children aged 18 years or younger. The team then exposed each sample to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a known stimulant of the immune response. When healthy cells are exposed to LPS, it prompts the production of TNF-alpha.

When they analyzed the immune response, the researchers found that blood samples from the healthy children responded normally to LPS, producing high levels of TNF-alpha.

Samples from the patients with critical injuries all showed at least a moderate decrease in the production of TNF-alpha. But the children who went on to develop an infection showed a much more severe and persistent drop in TNF-alpha following injury.

While the findings strongly suggest that infection risk is associated with immune system function after critical injury, they don’t explain what’s causing the malfunction. Dr Hall’s team is investigating that question now.

Transfusion implications

The research also highlighted another issue that may affect the immune response in critical illness. The team found that patients who received a transfusion of blood stored for more than 2 weeks had a lower level of TNF-alpha production than kids whose transfused blood was less than 2 weeks old, regardless of the severity of their original injury.

This supports a study published by Dr Hall and his colleagues in 2012 in Transfusion. The study showed the same immunosuppressive effect in a human cell culture model.

Dr Hall plans to look into this further through his work with a multi-institutional effort called The Pediatric Critical Care Blood Research Network (BloodNet). The group is studying, among other things, what impact blood transfusions have on immune function.

“There’s a whole line of research in which we’re involved that is dedicated to understanding the effects of transfusion in critical illness,” he said. “It’s not clear yet if blood transfusions are immunosuppressive, but our work so far suggests that blood becomes more immunosuppressive the longer it sits on the shelf.”

Reversing immunosuppression

Yet another element to the study involves reversing the immunosuppression that follows critical injury or illness. The researchers took 3 blood samples in which TNF-alpha production was decreased and cultured them with GM-CSF.

Once treated, the cells began to produce normal levels of TNF-alpha—an indication that the immunosuppression had been reversed.

Dr Hall is now leading a phase 4 clinical trial of GM-CSF to reverse immunosuppression in critically injured patients aged 1 to 21 years old.

Although findings from that project won’t be ready for another year or so, the results in the Shock article seem to offer yet another weapon in physicians’ arsenal when caring for critically ill and injured children, Dr Hall said.

“We have certainly made headway in reducing preventable infections through programs such as our own Zero Hero initiative,” he noted.

“But what this paper suggests is that it’s also important to consider the patient’s immune system and how well they are able to fight off infection. We believe that critical illness- and injury-related immune suppression may be reversible with beneficial effects on clinical outcomes.” ![]()

New formulation improves chemo drug

Credit: Larry Ostby

A new formulation of the chemotherapy drug cisplatin can significantly increase the drug’s ability to target and destroy cancer cells, a new study suggests.

Scientists constructed a modified version of cisplatin called Platin-M, which is designed to overcome treatment resistance by attacking mitochondria within cancer cells.

“You can think of mitochondria as a kind of powerhouse for the cell, generating the energy it needs to grow and reproduce,” said Shanta Dhar, PhD, of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia.

“This prodrug delivers cisplatin directly to the mitochondria in cancerous cells. Without that essential powerhouse, the cell cannot survive.”

Dr Dhar and her colleagues described the creation of this prodrug in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sean Marrache, a graduate student in Dr Dhar’s lab, entrapped Platin-M in a specially designed nanoparticle that seeks out the mitochondria and releases the drug. Once inside, Platin-M interferes with the mitochondria’s DNA, triggering cell death.

The researchers tested Platin-M on neuroblastoma cells. In experiments using a cisplatin-resistant cell culture, Platin-M nanoparticles were roughly 17 times more active than cisplatin alone.

“This technique could become a treatment for a number of cancers, but it may prove most useful for more aggressive forms of cancer that are resistant to current therapies,” said Rakesh Pathak, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr Dhar’s lab.

However, the researchers cautioned that these results are preliminary, and more work is necessary before Platin-M enters clinical trials. Still, their early results in mouse models are encouraging, and they are currently developing safety trials in larger animals.

“Cisplatin is a well-studied chemotherapy, so we hope our unique formulation will enhance its efficacy,” Dr Dhar said. “We are excited about these early results, which look very promising.” ![]()

Credit: Larry Ostby

A new formulation of the chemotherapy drug cisplatin can significantly increase the drug’s ability to target and destroy cancer cells, a new study suggests.

Scientists constructed a modified version of cisplatin called Platin-M, which is designed to overcome treatment resistance by attacking mitochondria within cancer cells.

“You can think of mitochondria as a kind of powerhouse for the cell, generating the energy it needs to grow and reproduce,” said Shanta Dhar, PhD, of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia.

“This prodrug delivers cisplatin directly to the mitochondria in cancerous cells. Without that essential powerhouse, the cell cannot survive.”

Dr Dhar and her colleagues described the creation of this prodrug in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sean Marrache, a graduate student in Dr Dhar’s lab, entrapped Platin-M in a specially designed nanoparticle that seeks out the mitochondria and releases the drug. Once inside, Platin-M interferes with the mitochondria’s DNA, triggering cell death.

The researchers tested Platin-M on neuroblastoma cells. In experiments using a cisplatin-resistant cell culture, Platin-M nanoparticles were roughly 17 times more active than cisplatin alone.

“This technique could become a treatment for a number of cancers, but it may prove most useful for more aggressive forms of cancer that are resistant to current therapies,” said Rakesh Pathak, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr Dhar’s lab.

However, the researchers cautioned that these results are preliminary, and more work is necessary before Platin-M enters clinical trials. Still, their early results in mouse models are encouraging, and they are currently developing safety trials in larger animals.

“Cisplatin is a well-studied chemotherapy, so we hope our unique formulation will enhance its efficacy,” Dr Dhar said. “We are excited about these early results, which look very promising.” ![]()

Credit: Larry Ostby

A new formulation of the chemotherapy drug cisplatin can significantly increase the drug’s ability to target and destroy cancer cells, a new study suggests.

Scientists constructed a modified version of cisplatin called Platin-M, which is designed to overcome treatment resistance by attacking mitochondria within cancer cells.

“You can think of mitochondria as a kind of powerhouse for the cell, generating the energy it needs to grow and reproduce,” said Shanta Dhar, PhD, of the University of Georgia in Athens, Georgia.

“This prodrug delivers cisplatin directly to the mitochondria in cancerous cells. Without that essential powerhouse, the cell cannot survive.”

Dr Dhar and her colleagues described the creation of this prodrug in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sean Marrache, a graduate student in Dr Dhar’s lab, entrapped Platin-M in a specially designed nanoparticle that seeks out the mitochondria and releases the drug. Once inside, Platin-M interferes with the mitochondria’s DNA, triggering cell death.

The researchers tested Platin-M on neuroblastoma cells. In experiments using a cisplatin-resistant cell culture, Platin-M nanoparticles were roughly 17 times more active than cisplatin alone.

“This technique could become a treatment for a number of cancers, but it may prove most useful for more aggressive forms of cancer that are resistant to current therapies,” said Rakesh Pathak, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr Dhar’s lab.

However, the researchers cautioned that these results are preliminary, and more work is necessary before Platin-M enters clinical trials. Still, their early results in mouse models are encouraging, and they are currently developing safety trials in larger animals.

“Cisplatin is a well-studied chemotherapy, so we hope our unique formulation will enhance its efficacy,” Dr Dhar said. “We are excited about these early results, which look very promising.” ![]()

Extending Therapy for Breast Cancer

For more presentations from the 9th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), click here: AVAHO Meeting Presentations

For more presentations from the 9th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), click here: AVAHO Meeting Presentations

For more presentations from the 9th Annual Meeting of the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO), click here: AVAHO Meeting Presentations

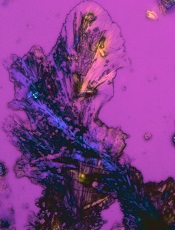

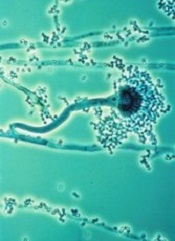

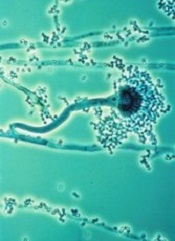

CAR T cells may fight fungal infections

T cells modified using the Sleeping Beauty gene transfer system may help fight infections caused by invasive Aspergillus fungus.

Sleeping Beauty is already being used to create chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to treat leukemias and lymphomas.

And now, researchers have found the system may also be effective for combatting fungal infections that can be deadly for immunosuppressed patients, such as those receiving transplants to treat hematologic cancers.

“We demonstrated a new approach for Aspergillus immunotherapy based on redirecting T-cell specificity through a CAR that recognizes carbohydrate antigen on the fungal cell wall,” said study author Laurence Cooper, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

He and his colleagues described this approach in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dr Cooper originally learned about Sleeping Beauty gene transfer from a study published by Perry Hackett, PhD, a professor at the University of Minnesota who created the process.

The system is named Sleeping Beauty because Dr Hackett was able to “awaken” an extinct transposon—DNA that can replicate itself and insert the copy back into the genome—and package it with a gene he wants to transfer into a plasmid. An associated transposase enzyme binds to the plasmid, cuts the transposon and gene out of the plasmid, and pastes it into the target DNA sequence.

Dr Cooper and his colleagues have found they can use this process to engineer T cells that target sugar molecules in the Aspergillus cell walls, thereby killing the fungus.

Specifically, the team adapted the pattern-recognition receptor Dectin-1 to activate T cells via chimeric CD28 and CD3-ζ (D-CAR) upon binding with carbohydrate in the cell wall of Aspergillus germlings. They used Sleeping Beauty to modify the T cells to express D-CAR.

These D-CAR+ T cells exhibited specificity for β-glucan, and this inhibited Aspergillus growth both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, the researchers found that treating D-CAR+ T cells with steroids did not significantly compromise antifungal activity.

“The [D-CAR+ T cells] can be manipulated in a manner suitable for human application,” Dr Cooper said, “enabling this immunology to be translated into immunotherapy.”![]()

T cells modified using the Sleeping Beauty gene transfer system may help fight infections caused by invasive Aspergillus fungus.

Sleeping Beauty is already being used to create chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to treat leukemias and lymphomas.

And now, researchers have found the system may also be effective for combatting fungal infections that can be deadly for immunosuppressed patients, such as those receiving transplants to treat hematologic cancers.

“We demonstrated a new approach for Aspergillus immunotherapy based on redirecting T-cell specificity through a CAR that recognizes carbohydrate antigen on the fungal cell wall,” said study author Laurence Cooper, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

He and his colleagues described this approach in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dr Cooper originally learned about Sleeping Beauty gene transfer from a study published by Perry Hackett, PhD, a professor at the University of Minnesota who created the process.

The system is named Sleeping Beauty because Dr Hackett was able to “awaken” an extinct transposon—DNA that can replicate itself and insert the copy back into the genome—and package it with a gene he wants to transfer into a plasmid. An associated transposase enzyme binds to the plasmid, cuts the transposon and gene out of the plasmid, and pastes it into the target DNA sequence.

Dr Cooper and his colleagues have found they can use this process to engineer T cells that target sugar molecules in the Aspergillus cell walls, thereby killing the fungus.

Specifically, the team adapted the pattern-recognition receptor Dectin-1 to activate T cells via chimeric CD28 and CD3-ζ (D-CAR) upon binding with carbohydrate in the cell wall of Aspergillus germlings. They used Sleeping Beauty to modify the T cells to express D-CAR.

These D-CAR+ T cells exhibited specificity for β-glucan, and this inhibited Aspergillus growth both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, the researchers found that treating D-CAR+ T cells with steroids did not significantly compromise antifungal activity.

“The [D-CAR+ T cells] can be manipulated in a manner suitable for human application,” Dr Cooper said, “enabling this immunology to be translated into immunotherapy.”![]()

T cells modified using the Sleeping Beauty gene transfer system may help fight infections caused by invasive Aspergillus fungus.

Sleeping Beauty is already being used to create chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells to treat leukemias and lymphomas.

And now, researchers have found the system may also be effective for combatting fungal infections that can be deadly for immunosuppressed patients, such as those receiving transplants to treat hematologic cancers.

“We demonstrated a new approach for Aspergillus immunotherapy based on redirecting T-cell specificity through a CAR that recognizes carbohydrate antigen on the fungal cell wall,” said study author Laurence Cooper, MD, PhD, of MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.

He and his colleagues described this approach in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Dr Cooper originally learned about Sleeping Beauty gene transfer from a study published by Perry Hackett, PhD, a professor at the University of Minnesota who created the process.

The system is named Sleeping Beauty because Dr Hackett was able to “awaken” an extinct transposon—DNA that can replicate itself and insert the copy back into the genome—and package it with a gene he wants to transfer into a plasmid. An associated transposase enzyme binds to the plasmid, cuts the transposon and gene out of the plasmid, and pastes it into the target DNA sequence.

Dr Cooper and his colleagues have found they can use this process to engineer T cells that target sugar molecules in the Aspergillus cell walls, thereby killing the fungus.

Specifically, the team adapted the pattern-recognition receptor Dectin-1 to activate T cells via chimeric CD28 and CD3-ζ (D-CAR) upon binding with carbohydrate in the cell wall of Aspergillus germlings. They used Sleeping Beauty to modify the T cells to express D-CAR.

These D-CAR+ T cells exhibited specificity for β-glucan, and this inhibited Aspergillus growth both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, the researchers found that treating D-CAR+ T cells with steroids did not significantly compromise antifungal activity.

“The [D-CAR+ T cells] can be manipulated in a manner suitable for human application,” Dr Cooper said, “enabling this immunology to be translated into immunotherapy.”![]()

Nanoparticles may treat and prevent MM

Investigators say they’ve developed nanoparticles that can target multiple myeloma (MM) cells in the bone, as well as increase bone strength and volume to prevent MM progression.

“We engineered and tested a bone-targeted nanoparticle system to selectively target the bone microenvironment and release a therapeutic drug in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, leading to bone microenvironment remodeling and prevention of disease progression,” said study author Archana Swami, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

She and her colleagues described this system in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team developed stealth nanoparticles made of biodegradable polymers and alendronate, a therapeutic agent that belongs to the bisphosphonate class of drugs. Bisphosphonates bind to calcium and accumulate in high concentration in bones.

By coating the surface of the nanoparticles with alendronate, the investigators enabled the nanoparticles to home to bone tissue to deliver drugs encapsulated within the nanoparticles. In this way, the particles could kill tumor cells and stimulate healthy bone tissue growth.

The investigators tested their drug-toting nanoparticles in mice with MM. The mice were pretreated with nanoparticles containing the drug bortezomib, then injected with MM cells.

The treatment resulted in slower MM growth and prolonged survival. Moreover, bortezomib as a pretreatment regimen changed the make-up of bone, enhancing its strength and volume.

“These findings suggest that bone-targeted nanoparticle anticancer therapies offer a novel way to deliver a concentrated amount of drug in a controlled and target-specific manner to prevent tumor progression in multiple myeloma,” said study author Omid Farokhzad, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“This approach may prove useful in treatment of incidents of bone metastasis, common in 60% to 80% of cancer patients and for treatment of early stages of multiple myeloma.”

“This study provides the proof-of-concept that targeting the bone marrow niche can prevent or delay bone metastasis,” added Irene Ghobrial, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“This work will pave the way for the development of innovative clinical trials in patients with myeloma to prevent progression from early precursor stages or in patients with breast, prostate, or lung cancer who are at high-risk to develop bone metastasis.” ![]()

Investigators say they’ve developed nanoparticles that can target multiple myeloma (MM) cells in the bone, as well as increase bone strength and volume to prevent MM progression.

“We engineered and tested a bone-targeted nanoparticle system to selectively target the bone microenvironment and release a therapeutic drug in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, leading to bone microenvironment remodeling and prevention of disease progression,” said study author Archana Swami, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

She and her colleagues described this system in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team developed stealth nanoparticles made of biodegradable polymers and alendronate, a therapeutic agent that belongs to the bisphosphonate class of drugs. Bisphosphonates bind to calcium and accumulate in high concentration in bones.

By coating the surface of the nanoparticles with alendronate, the investigators enabled the nanoparticles to home to bone tissue to deliver drugs encapsulated within the nanoparticles. In this way, the particles could kill tumor cells and stimulate healthy bone tissue growth.

The investigators tested their drug-toting nanoparticles in mice with MM. The mice were pretreated with nanoparticles containing the drug bortezomib, then injected with MM cells.

The treatment resulted in slower MM growth and prolonged survival. Moreover, bortezomib as a pretreatment regimen changed the make-up of bone, enhancing its strength and volume.

“These findings suggest that bone-targeted nanoparticle anticancer therapies offer a novel way to deliver a concentrated amount of drug in a controlled and target-specific manner to prevent tumor progression in multiple myeloma,” said study author Omid Farokhzad, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“This approach may prove useful in treatment of incidents of bone metastasis, common in 60% to 80% of cancer patients and for treatment of early stages of multiple myeloma.”

“This study provides the proof-of-concept that targeting the bone marrow niche can prevent or delay bone metastasis,” added Irene Ghobrial, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“This work will pave the way for the development of innovative clinical trials in patients with myeloma to prevent progression from early precursor stages or in patients with breast, prostate, or lung cancer who are at high-risk to develop bone metastasis.” ![]()

Investigators say they’ve developed nanoparticles that can target multiple myeloma (MM) cells in the bone, as well as increase bone strength and volume to prevent MM progression.

“We engineered and tested a bone-targeted nanoparticle system to selectively target the bone microenvironment and release a therapeutic drug in a spatiotemporally controlled manner, leading to bone microenvironment remodeling and prevention of disease progression,” said study author Archana Swami, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

She and her colleagues described this system in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team developed stealth nanoparticles made of biodegradable polymers and alendronate, a therapeutic agent that belongs to the bisphosphonate class of drugs. Bisphosphonates bind to calcium and accumulate in high concentration in bones.

By coating the surface of the nanoparticles with alendronate, the investigators enabled the nanoparticles to home to bone tissue to deliver drugs encapsulated within the nanoparticles. In this way, the particles could kill tumor cells and stimulate healthy bone tissue growth.

The investigators tested their drug-toting nanoparticles in mice with MM. The mice were pretreated with nanoparticles containing the drug bortezomib, then injected with MM cells.

The treatment resulted in slower MM growth and prolonged survival. Moreover, bortezomib as a pretreatment regimen changed the make-up of bone, enhancing its strength and volume.

“These findings suggest that bone-targeted nanoparticle anticancer therapies offer a novel way to deliver a concentrated amount of drug in a controlled and target-specific manner to prevent tumor progression in multiple myeloma,” said study author Omid Farokhzad, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“This approach may prove useful in treatment of incidents of bone metastasis, common in 60% to 80% of cancer patients and for treatment of early stages of multiple myeloma.”

“This study provides the proof-of-concept that targeting the bone marrow niche can prevent or delay bone metastasis,” added Irene Ghobrial, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“This work will pave the way for the development of innovative clinical trials in patients with myeloma to prevent progression from early precursor stages or in patients with breast, prostate, or lung cancer who are at high-risk to develop bone metastasis.” ![]()