User login

When snoring is more than an annoyance

We have all seen cartoons of an unhappy wife awake in bed next to her loudly snoring husband. Casual conversations with friends, particularly female ones, indicate that this is an accurate representation of a common scenario. As I have started to probe more diligently for evidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in my patients, not just in those who complain of “fatigue” (more patients use this term with me than “sleepiness”), I see a lot of shaking of heads from the wives of men who deny that they snore or have disrupted sleep. I am not implying that this is solely a male disease. Far from it. But as in other medical scenarios, the Y chromosome seems somehow linked to denial or lack of awareness of symptoms. In any event, I was not a bit surprised to read in the review by Dr. Mehra in this issue of the Journal that 17% of adults may have OSA.

As awareness of OSA has grown and testing for it has become easier, multiple reports have documented associated comorbidities: hypertension, restless leg syndrome, gout, and neurocognitive deficits. Home devices to treat OSA have significantly improved. Technological advances have led to the development of small, quiet, smart pumps that provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via nasal or relatively comfortable full-face masks. Compliance and patient acceptance of CPAP have improved, although patient education and a bit of cajoling in the office are still necessary—less so if the bedroom partner is also present for this discussion.

Perhaps surprising is a growing pool of data showing that CPAP’s benefits extend to more than just reducing sleepiness. It can reduce nocturia, restless leg syndrome, arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, gastric reflux, and fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. Snoring and thus probably sleep-partner satisfaction are also improved.

Several physiologic mechanisms may explain the benefits of CPAP, including reducing hypoxic episodes (explaining its effect on atrial fibrillation), altered atrial natriuretic factor levels (thus reducing nocturia), and changing intrathoracic pressure (thus reducing gastric reflux). It will be interesting to see if there are long-term effects of successfully applied CPAP on neurocognition and progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

While high-decibel snoring and snorting are not present in all patients with OSA, it is quite clear now that they represent far more than an annoyance. We should be vigilant about looking for OSA and strongly encourage a trial of CPAP in appropriately diagnosed patients.

We have all seen cartoons of an unhappy wife awake in bed next to her loudly snoring husband. Casual conversations with friends, particularly female ones, indicate that this is an accurate representation of a common scenario. As I have started to probe more diligently for evidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in my patients, not just in those who complain of “fatigue” (more patients use this term with me than “sleepiness”), I see a lot of shaking of heads from the wives of men who deny that they snore or have disrupted sleep. I am not implying that this is solely a male disease. Far from it. But as in other medical scenarios, the Y chromosome seems somehow linked to denial or lack of awareness of symptoms. In any event, I was not a bit surprised to read in the review by Dr. Mehra in this issue of the Journal that 17% of adults may have OSA.

As awareness of OSA has grown and testing for it has become easier, multiple reports have documented associated comorbidities: hypertension, restless leg syndrome, gout, and neurocognitive deficits. Home devices to treat OSA have significantly improved. Technological advances have led to the development of small, quiet, smart pumps that provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via nasal or relatively comfortable full-face masks. Compliance and patient acceptance of CPAP have improved, although patient education and a bit of cajoling in the office are still necessary—less so if the bedroom partner is also present for this discussion.

Perhaps surprising is a growing pool of data showing that CPAP’s benefits extend to more than just reducing sleepiness. It can reduce nocturia, restless leg syndrome, arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, gastric reflux, and fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. Snoring and thus probably sleep-partner satisfaction are also improved.

Several physiologic mechanisms may explain the benefits of CPAP, including reducing hypoxic episodes (explaining its effect on atrial fibrillation), altered atrial natriuretic factor levels (thus reducing nocturia), and changing intrathoracic pressure (thus reducing gastric reflux). It will be interesting to see if there are long-term effects of successfully applied CPAP on neurocognition and progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

While high-decibel snoring and snorting are not present in all patients with OSA, it is quite clear now that they represent far more than an annoyance. We should be vigilant about looking for OSA and strongly encourage a trial of CPAP in appropriately diagnosed patients.

We have all seen cartoons of an unhappy wife awake in bed next to her loudly snoring husband. Casual conversations with friends, particularly female ones, indicate that this is an accurate representation of a common scenario. As I have started to probe more diligently for evidence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in my patients, not just in those who complain of “fatigue” (more patients use this term with me than “sleepiness”), I see a lot of shaking of heads from the wives of men who deny that they snore or have disrupted sleep. I am not implying that this is solely a male disease. Far from it. But as in other medical scenarios, the Y chromosome seems somehow linked to denial or lack of awareness of symptoms. In any event, I was not a bit surprised to read in the review by Dr. Mehra in this issue of the Journal that 17% of adults may have OSA.

As awareness of OSA has grown and testing for it has become easier, multiple reports have documented associated comorbidities: hypertension, restless leg syndrome, gout, and neurocognitive deficits. Home devices to treat OSA have significantly improved. Technological advances have led to the development of small, quiet, smart pumps that provide continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via nasal or relatively comfortable full-face masks. Compliance and patient acceptance of CPAP have improved, although patient education and a bit of cajoling in the office are still necessary—less so if the bedroom partner is also present for this discussion.

Perhaps surprising is a growing pool of data showing that CPAP’s benefits extend to more than just reducing sleepiness. It can reduce nocturia, restless leg syndrome, arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, gastric reflux, and fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events. Snoring and thus probably sleep-partner satisfaction are also improved.

Several physiologic mechanisms may explain the benefits of CPAP, including reducing hypoxic episodes (explaining its effect on atrial fibrillation), altered atrial natriuretic factor levels (thus reducing nocturia), and changing intrathoracic pressure (thus reducing gastric reflux). It will be interesting to see if there are long-term effects of successfully applied CPAP on neurocognition and progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

While high-decibel snoring and snorting are not present in all patients with OSA, it is quite clear now that they represent far more than an annoyance. We should be vigilant about looking for OSA and strongly encourage a trial of CPAP in appropriately diagnosed patients.

Sleep apnea ABCs: Airway, breathing, circulation

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is common and poorly recognized and, if untreated, leads to serious health consequences. This article discusses the epidemiology of OSA, describes common presenting signs and symptoms, and reviews diagnostic testing and treatment options. Adverse health effects related to untreated sleep apnea are also discussed.

COMMON, POORLY RECOGNIZED, AND COSTLY IF UNTREATED

OSA is very common in the general population and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. An estimated 17% of the general adult population has OSA, and the numbers are increasing with the obesity epidemic. Nearly 1 in 15 adults has at least moderate sleep apnea,1,2 and approximately 85% of cases are estimated to be undiagnosed.3 A 1999 study estimated that untreated OSA resulted in approximately $3.4 billion in additional medical costs per year in the United States,4 a figure that is likely to be higher now, given the rising prevalence of OSA. The prevalence of OSA in primary care and subspecialty clinics is even higher than in the community, as more than half of patients who have diabetes or hypertension and 30% to 40% of patients with coronary artery disease are estimated to have OSA.5–7

REPETITIVE UPPER-AIRWAY COLLAPSE

During sleep, parasympathetic activity is enhanced and the muscle tone of the upper airway is decreased, particularly in the pharyngeal dilator muscles. Still, even in the supine position, a healthy person maintains patency of the airway and adequate airflow during sleep.

OSA is characterized by repetitive complete or partial collapse of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in an apneic or hypopneic event, respectively, and often causing snoring from upper-airway tissue vibration.

People who are susceptible to OSA typically have a smaller, more collapsible airway that is often less distensible and has a higher critical closing pressure. Radiographic and physiologic data have shown that the airway dimensions of patients with OSA are smaller than in those without OSA. The shape of the airway of a patient with OSA is often elliptical, given the extrinsic compression of the lateral aspects of the airway by increased size of the parapharyngeal fat pads. OSA episodes are characterized by closure of the upper airway and by progressively increasing respiratory efforts driven by chemoreceptor and mechanoreceptor stimuli, culminating in an arousal from sleep and a reopening of the airway.

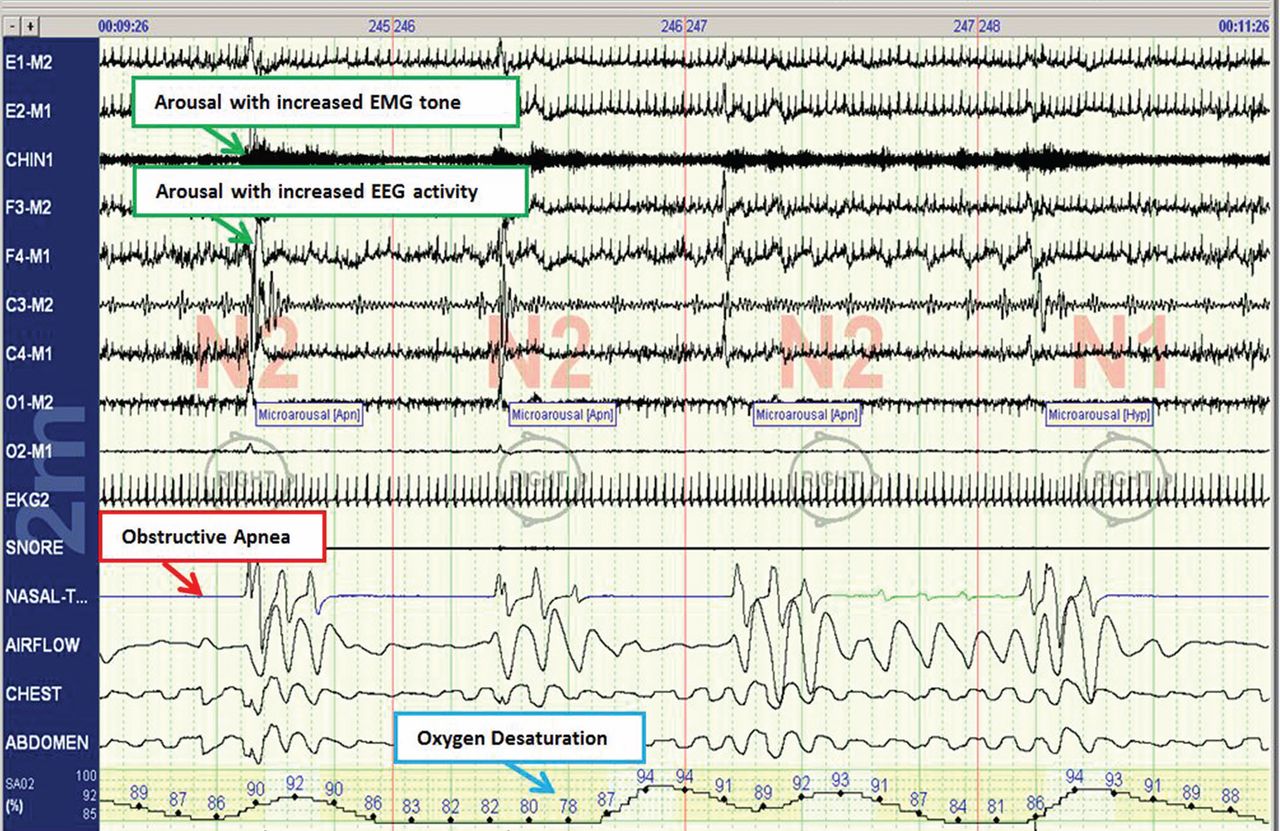

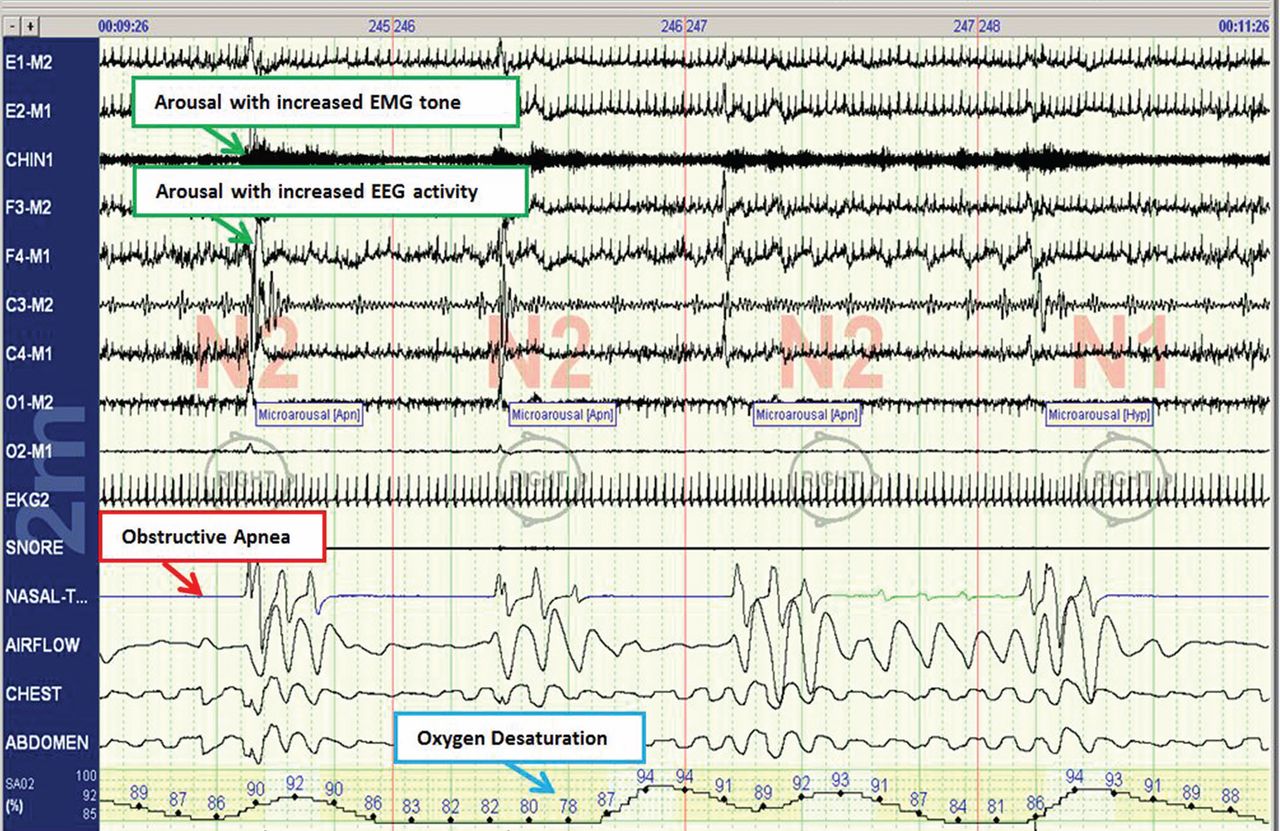

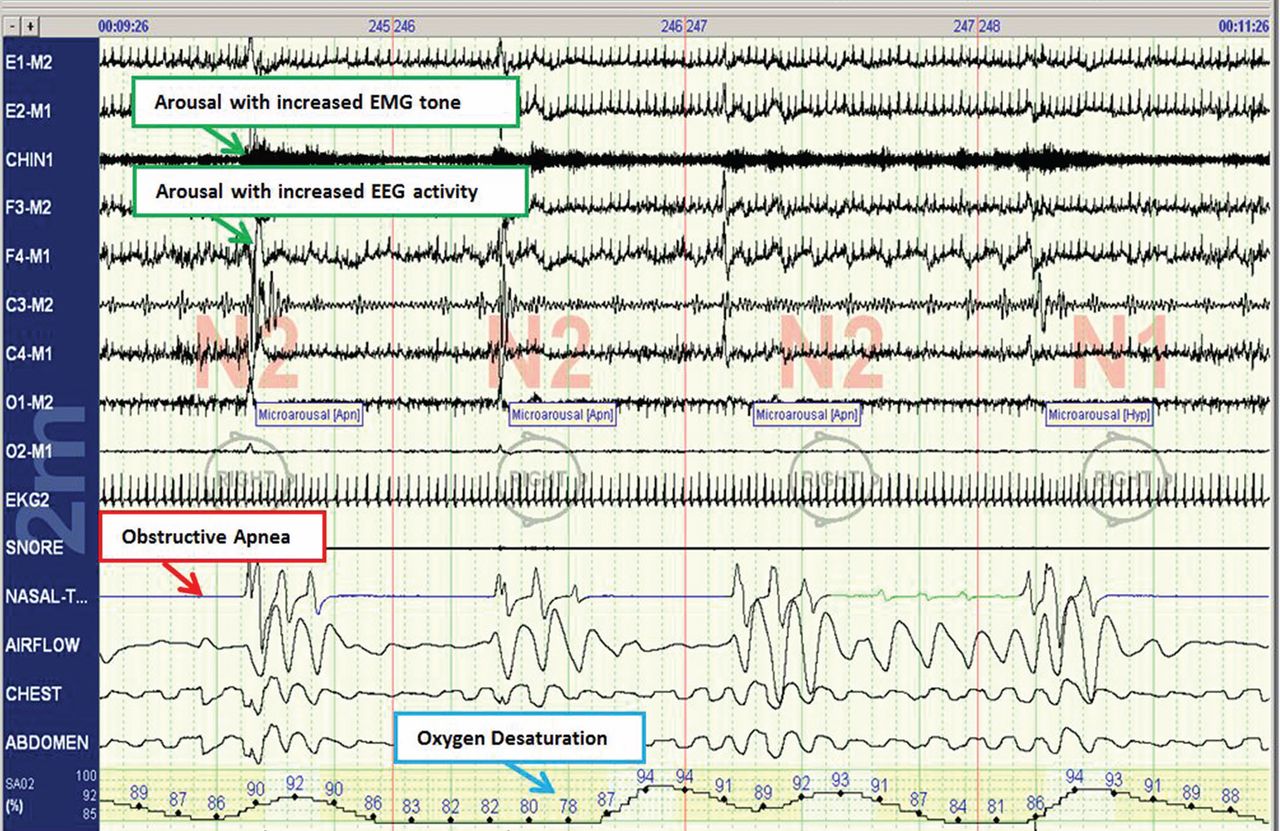

The disease-defining metric used for assessing OSA severity is the apnea-hypopnea index, ie, the number of apneas and hypopneas that occur per hour of sleep.8 An apneic or hypopneic event is identified during polysomnography by the complete cessation of airflow or by a reduction in airflow for 10 seconds or longer (Figure 1).

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES IF UNTREATED

Untreated sleep apnea causes numerous pathophysiologic perturbations, including chronic intermittent hypoxia, ventilatory overshoot hyperoxia, increased sympathetic nervous system activity, intrathoracic pressure swings, hypercapnea, sleep fragmentation, increased arousals, reduced sleep duration, and fragmentation of rapid-eye-movement sleep.

Intermittent hypoxia activates the sympathetic nervous system and causes pulmonary vasoconstriction, with increases in pulmonary arterial pressures and myocardial workload. Sympathetic activation, ascertained by peroneal microneurography, has been shown to be increased not only during sleep but also persisting during wakefulness in patients with untreated OSA vs those without OSA.9 Autonomic nervous system fluctuations accompany apneic episodes, resulting in enhanced parasympathetic tone and sympathetic activation associated with a rise in blood pressure and heart rate that occur after the respiratory event.

Intermediate pathways that link the negative pathophysiologic effects of OSA with adverse health outcomes include increased systemic inflammation, increased oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance, hypercoagulability, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic dysfunction.

As a result, a variety of adverse clinical outcomes are associated with untreated OSA, including systemic hypertension, ischemic heart disease and atherosclerosis, diastolic dysfunction, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, increased risk of death, and sudden death, as well as noncardiovascular outcomes such as gout, neurocognitive deficits, and mood disorders.10

Inflammatory and atherogenic effects

Increased levels of markers of systemic inflammation, prothrombosis, and oxidative stress have been observed in OSA and may be key pathophysiologic links between OSA and cardiovascular sequelae. OSA has been associated with up-regulation of a number of inflammatory mediators: interleukin (IL) 6, soluble IL-6 receptor, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and C-reactive protein. Soluble IL-6 levels in particular are higher in people who have sleep-disordered breathing, as reflected by the apnea-hypopnea index independent of obesity, with relationships stronger in the morning than in the evening. This likely reflects the overnight OSA-related physiologic stress.11

Thrombotic potential is also enhanced, with higher levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, fibrinogen, P-selectin, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Some of these factors normally have a diurnal cycle, with higher levels in the morning, but in OSA, increasing OSA severity is associated with increased prothrombotic potential in the morning hours. Of interest, levels of these substances showed a plateau effect, rising in people who had only mildly elevated apnea-hypopnea indices and then leveling off.12 Intermittent hypoxia followed by ventilatory overshoot hyperoxia, characteristic of sleep apnea, provides the ideal environment for augmentation of oxidative stress, with evidence of increased oxidation of serum proteins and lipids. Hypoxia and oxygen-derived free radicals may result in cardiac myocyte injury. Experimental data demonstrate that intermittent hypoxia combined with a high-fat diet results in synergistic acceleration of evidence of atherogenic lesions.

Patients with OSA also have evidence of endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, all pathways that can facilitate the progression of atherosclerosis in OSA.13–15

Cardiac arrhythmias

In the Sleep Heart Health Study, a multicenter epidemiologic study designed to examine the relationships of OSA and cardiovascular outcomes, those who had moderate to severe OSA had a risk of ventricular and atrial arrhythmias two to four times higher than those without OSA, even after correction for the confounding influences of obesity and underlying cardiovascular risk.14 These findings were corroborated in subsequent work highlighting monotonic dose-response relationships with increasing OSA severity and increased odds of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in a cohort of about 3,000 older men.11 Additional compelling evidence of a causal relationship is that the risk of discrete arrhythmic events is markedly increased after a respiratory disturbance in sleep.16

In patients who successfully underwent cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, those who had sleep apnea but were not treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) had a much higher rate of recurrence of atrial fibrillation during the subsequent year than those with CPAP-treated sleep apnea and than controls never diagnosed with sleep apnea. In the untreated patients with sleep apnea, the mean nocturnal fall in oxygen saturation was significantly greater in those who had recurrence of atrial fibrillation than in those who did not, suggesting hypoxia as an important mechanism contributing to atrial fibrillation.17

Since then, several other retrospective studies have shown similar findings after pulmonary vein antrum isolation and ablation in terms of reduction of atrial fibrillation recurrence with CPAP treatment in OSA.18

Walia et al19 described a patient with moderate sleep apnea who underwent a split-night study. During the baseline part of the study, the patient had about 18 ectopic beats per minute. During the second portion of the study while CPAP was applied, progressively fewer ectopic beats occurred as airway pressure was increased until a normal rhythm without ectopic beats was achieved at the goal treatment CPAP pressure setting.

Cardiovascular disease, stroke, and death

Marin et al20 followed about 1,500 men for 10 years, including some who had severe OSA, some with sleep apnea who were treated with CPAP, and controls. The risk of nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease events was nearly three times higher in those with severe disease than in healthy participants. Those treated with CPAP had a risk approximately the same as in the control group.

The Sleep Heart Study followed approximately 6,000 people with untreated sleep apnea for a median of nearly 9 years. It found a significant association between the apnea-hypopnea index and ischemic stroke, especially in men.21 Survival in patients with heart failure is also associated with the degree of OSA; patients with more severe disease (an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15) have a nearly three times greater risk of death than those with no disease or only mild disease (apnea-hypopnea index < 15).22

From the standpoint of health care utilization, findings that central sleep apnea predicts an increased risk of hospital readmission in heart failure are of particular interest.23

People with OSA are at increased risk of nocturnal sudden cardiac death.24 Sleep apnea is also associated with an increased overall death rate, and the higher the apnea-hypopnea index, the higher the death rate,25 even after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and underlying cardiovascular risk, with findings most pronounced in men under age 70.

Motor vehicle accidents

The need for caution during driving should be discussed with every patient, as motor vehicle accidents are an immediate danger to the patient and others. The association with motor vehicle accidents is independent of sleepiness, and drivers with sleep apnea often do not perceive performance impairment. Young et al26 found that men who snored were 3.4 times as likely to have an accident over a 5-year period, and that men and women with an apnea-hypopnea index greater than 15 were more than 7 times as likely to have multiple accidents over a 5-year period, highlighting the importance of discussing, documenting, and expeditiously diagnosing and treating OSA, particularly in those who report drowsiness while driving.

CLINICAL RISK FACTORS

Risk factors can be divided into nonmodifiable and modifiable ones.

Nonmodifiable factors

Age. Bimodal distributions in OSA prevalence have been observed; ie, that the pediatric population and people who are middle-aged have the highest prevalence of OSA. A linear relationship between sleep apnea prevalence and age until about age 65 was identified in data from the Sleep Heart Health Study.27 After that, the prevalence rates plateau; it is unclear if this is secondary to natural remission of the disease after a certain age or because patients with more severe disease have died by that age (ie, survivorship bias), blunting an increase in prevalence.

Sex. Men develop sleep apnea at a rate three to five times that of women. Several explanations have been proposed to account for this.28,29 Sex hormones are one factor; women with sleep apnea on hormone replacement therapy have a significantly less-severe sleep apnea burden than other postmenopausal women,30 suggesting a positive effect from estrogen. Sex-based differences in fat distribution, length and collapsibility of the upper airway, genioglossal activity, neurochemical control mechanisms, and arousal response may also contribute to prevalence differences between men and women.

As with coronary artery disease, the presentation of sleep apnea may be atypical in women, particularly around menopause. Sleep apnea should be considered in women who have snoring and daytime sleepiness.

Race. Whites, African Americans, and Asians have a similar prevalence of sleep apnea, but groups differ in obesity rates and craniofacial anatomy.31–34 Asians tend to have craniofacial skeletal restriction. African Americans are more likely to have upper-airway soft-tissue risk and to develop more severe OSA. Whites tend to have both craniofacial and soft-tissue risk. For those with craniofacial anatomy predisposing to OSA, even mild obesity can make it manifest.

Syndromes that predispose to OSA can include craniofacial structural abnormalities, connective tissue problems, or alterations in ventilatory control (eg, Marfan, Down, and Pierre Robin syndromes).

Modifiable risk factors

Obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) is a firmly established risk factor, but not all obese patients develop obstructive sleep apnea, and not all people with sleep apnea are obese.

Obesity increases risk by altering the geometry and function of the upper airway, increasing collapsibility. The changes are particularly pronounced in the lateral aspects of the pharynx.35

Obesity also affects respiratory drive, likely in part from leptin resistance. Load compensation is another contributing factor: the increased mass in the thorax and abdomen increases the work of breathing and reduces functional residual capacity, increasing oxygen demands and leading to atelectasis and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

Although obesity is an important risk factor, it is important to recognize that obesity is not the only one to consider: most people with an apnea-hypopnea index of 5 or greater are not obese. The relationship between body mass index and sleep apnea is weaker in children and in the elderly, probably because other risk factors are more pronounced.36

Craniofacial structural abnormalities such as retrognathia (abnormal posterior position of the mandible) and micrognathia (undersized mandible) can increase the risk of OSA because of a resulting posteriorly displaced genioglossus muscle. Other conditions can alter chemosensitivity, affecting the pH and carbon dioxide level of the blood and therefore affecting ventilatory control mechanisms, making the person more prone to developing sleep apnea. Children and young adults may have tonsillar tissue that obstructs the airway.

The site of obstruction can be behind the palate (retropalatal), behind the tongue (retroglossal), or below the pharynx (hypopharyngeal). This helps explain why positive air way pressure—unlike surgery, which addresses a specific area—is often successful, as it serves to splint or treat all aspects of the airway.

FATIGUE, SLEEPINESS, SNORING, RESTLESS SLEEP

Sleep apnea can result in presentation of multiple signs and symptoms (Table 1).

Daytime sleepiness and fatigue are the most common symptoms. Although nonspecific, they are often quite pronounced. Two short questionnaires—the Epworth Sleepiness Scale37 and the Fatigue Severity Scale—can help distinguish between these two symptoms and assess their impact on a patient’s daily life. In the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, the patient rates his or her chance of dozing on a 4-point scale (0 = would never doze, to 3 = high chance of dozing) in eight situations:

- Sitting and reading

- Watching television

- Sitting inactive in a public place

- As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

- Lying down to rest in the afternoon

- Sitting and talking to someone

- Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol

- In a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic.

A score of 10 or more is consistent with significant subjective sleepiness.

The Fatigue Severity Scale assesses the impact of fatigue on daily living.

Snoring is a common and specific symptom of sleep apnea; however, not all patients who snore have OSA.

Restlessness during sleep is very common—patients may disturb their bed partner by moving around a lot during sleep or report that the sheets are “all over the place” by morning.

Nocturia can also be a sign of sleep apnea and can contribute to sleep fragmentation. A proposed mechanism of this symptom includes alterations of intrathoracic pressure resulting in atrial stretch, which release atrial natriuretic peptide, leading to nocturia. Treating with CPAP has been found to reduce levels of atrial natriuretic peptide, contributing to better sleep.38

Morning headache may occur and is likely related to increased CO2 levels, which appear to culminate in the morning hours. End-tidal or transcutaneous CO2 monitoring during polysomnography can help elucidate the presence of sleep-related hypoventilation.

Libido is often diminished and can actually be improved with CPAP. This is therefore an important point to discuss with patients, as improved libido can often serve as an incentive for adherence to OSA treatment.

Insomnia exists in about 15% of patients, primarily as a result of sleep apnea-related with treatment.

Sweating, particularly forehead sweating associated with sleep apnea, more commonly occurs in children.

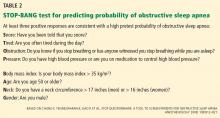

The STOP-BANG questionnaire (Table 2)39 was primarily validated in preoperative anesthesia testing. However, because of its ease of use and favorable performance characteristics, it is increasingly used to predict the likelihood of finding OSA before polysomnography. A score of 3 or more has a sensitivity of 93%.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION PROVIDES CLUES

Although the physical examination may be normal, certain findings indicate risk (Table 3). Obesity alone is not an accepted indication for polysomnography unless there are concomitant worrisome signs or symptoms. Of note, those who are morbidly obese (BMI > 40 kg/m2) have a prevalence of sleep apnea greater than 70%.

The classification by Friedman et al40 provides an indicator of risk. The patient is examined with the mouth opened wide and the tongue in a neutral natural position. Grades:

- I—Entire uvula and tonsils are visible

- II—Entire uvula is visible, but tonsils are not

- III—Soft palate is visible, but uvula is not

- IV—Only the hard palate is visible.

Especially in children and young adults, enlarged tonsils (or “kissing tonsils”) and a boggy edematous uvula set the stage for obstructive sleep apnea.

DIAGNOSIS REQUIRES SLEEP TESTING

A sleep study is the primary means of diagnosing OSA. Polysomnography includes electrooculography to determine when rapid-eye-movement sleep occurs; electromyography to measure muscle activity in the chin to help determine onset of sleep, with peripheral leads in the leg to measure leg movements; electroencephalography (EEG) to measure neural activity; electrocardiography; pulse oximetry to measure oxygen saturation; measurement of oronasal flow; and measurements of chest wall effort and body position using thoracic and abdominal belts that expand and contract with breathing; and audio recording to detect snoring.

Attended polysomnography requires the constant presence of a trained sleep technologist to monitor for technical issues and patient adherence.

End-tidal CO2 monitoring is a reasonable method to detect sleep-related hypoventilation but is not routinely performed in the United States. Transcutaneous CO2 monitoring is a different way to monitor CO2 used in the setting of positive airway pressure.

Polysomnography in a normal patient shows a regular pattern of increasing and decreasing airflow with inspiration and expiration while stable oxygen saturation is maintained.

In contrast, polysomnography of a patient with sleep apnea shows repetitive periods of no airflow, oxygen desaturation, and often evidence of thoracoabdominal paradox, punctuated by arousals on EEG associated with sympathetic activation (Figure 1). When the patient falls asleep, upper-airway muscle tone is reduced, causing an apneic event with hypoxia and pleural pressure swings. These prompt arousals with sympathetic activation that reestablish upper-airway muscle tone, allowing ventilation and reoxygenation to resume with a return to sleep.

Apnea-hypopnea index indicates severity

Sleep apnea severity is graded using the apnea-hypopnea index, ie, the number of apneic and hypopneic events per hour of sleep (Table 4).41 Events must last at least 10 seconds to be considered, ie, two consecutive missed breaths based on an average normal respiratory rate of about 12 breaths per minute for the typical adult.

The apnea-hypopnea index usually correlates with the severity of oxygen desaturation and with electrocardiographic abnormalities, including tachybradycardia and arrhythmias.

Although history, physical examination, and prediction tools are helpful in determining the likelihood that a patient has OSA, only polysomnography testing can establish the diagnosis. To diagnose OSA, 15 or more obstructive events per hour must be observed by polysomnography, or at least 5 events per hour with one of the following:

- Daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, or insomnia

- Waking with breath-holding, gasping, or choking

- Observer-reported loud snoring or breathing interruptions.41

Split-night study determines diagnosis and optimum treatment

The split-night study has two parts: the first is diagnostic polysomnography, followed by identification of the positive airway pressure that optimally treats the sleep apnea. The apnea-hypopnea index guides the need for the split-night study, with 40 being the established threshold according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

A home sleep study is appropriate for some patients

Home sleep testing is typically more limited than standard polysomnography; it monitors airflow, effort, and oxygenation. The test is intended for adults with a high pretest probability of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (STOP-BANG score ≥ 3). It is not intended for screening of asymptomatic patients or for those with coexisting sleep disorders (eg, central sleep apnea, sleep hypoventilation, periodic limb movements, insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders, parasomnias, narcolepsy) or medical disorders (eg, moderate to severe heart failure or other cardiac disease, symptomatic neurologic disease, moderate to severe pulmonary disease).42 Since March 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has covered CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea based on diagnosis by home sleep study testing.43

TREATMENT OF SLEEP APNEA

Basic steps for reducing OSA are:

Weight loss. Even small weight changes can significantly affect the severity of sleep apnea, perhaps even leading to a reassessment of the degree of OSA and CPAP requirements. Longitudinal epidemiologic data demonstrate that a 10% weight loss correlates with a 26% reduction in the apnea-hypopnea index, and conversely, a 10% weight gain is associated with a 32% increase.44

Some studies have found that bariatric surgery cures OSA in 75% to 88% of cases, independent of approach.45,46 However, a trial in 60 obese patients with OSA who were randomized to either a low-calorie diet or bariatric surgery found no statistical difference in the apnea-hypopnea index between the two groups despite greater weight loss in the surgery group.47

Avoiding certain medications. Benzodiazepines, narcotics, and alcohol reduce upper airway muscle tone and should be avoided. No medications are associated with improvement of OSA, although acetazolamide may be used to treat central sleep apnea.

Positional therapy. Sleeping on the back exacerbates the problem. Supine-related OSA occurs as a result of several factors, including gravity, airway anatomy, airway critical closing pressures, and effects on upper-airway dilator muscle function.

Sleep hygiene. General recommendations to engage in behaviors to promote sleep are recommended, including keeping consistent sleep-wake times, not watching television in bed, and avoidance of caffeine intake, particularly within 4 to 6 hours of bedtime.

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY

Nasal CPAP is the treatment of choice and is successful in 95% of patients when used consistently. It is not as costly as surgery, and results in improved long-term survival compared with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Another advantage is that the pressure can be retitrated as the patient’s condition changes, for example after a weight change or during pregnancy.

More than 15 randomized controlled trials have examined the effect of sleep apnea treatment with CPAP compared with either sham CPAP or another control. In a meta-analysis, CPAP was found to lead to an average systolic blood pressure reduction of about 2.5 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure reduction of 1.8 mm Hg. Although these reductions may seem negligible, benefits may be significant for cardiovascular outcomes.48,49

Challenges to treatment adherence

Adherence is the most commonly discussed problem with CPAP, but long-term adherence rates are comparable to medication compliance—about 60% to 70%. To optimize adherence, communication is important to ensure that problems are identified and addressed as they arise. Showing patients examples of apneic events and oxygen desaturation from their sleep study can enhance their understanding of OSA and its importance. Patients need to understand the serious nature of the disease and that CPAP therapy can significantly improve their quality of life and overall health, particularly from a cardiovascular perspective.

CPAP masks can be uncomfortable, posing a major barrier to compliance. But a number of mask designs are available, such as the nasal mask, the nasal pillow mask, and the oronasal mask. For patients with claustrophobia, the nasal pillow mask is an option, as it does not cover the face.

Some patients note symptoms of nasal congestion, although in many patients CPAP improves it. If congestion is a problem, the use of heated humidification with the machine, intranasal saline or gel, or nasal corticosteroids can help relieve it.

Pressure intolerance is a common problem. For those who feel that the pressure is too high, settings can be adjusted so that the pressure is gradually reduced between inspiration and expiration, ie, the use of expiratory pressure relief or consideration of the use of bilevel positive airway pressure.

Aerophagia (swallowing air) is a less common problem. It can also potentially be relieved with use of bilevel positive airway pressure.

Many patients develop skin irritation, which can be helped with moleskin, available at any pharmacy.

Social stigma can be a problem. Education regarding the importance of the treatment to health is essential.

Machine noise is less of a problem with the new machine models, but if it is a problem, a white-noise device or earplugs may help.

Other measures to improve compliance are keeping the regimen simple and ensuring that family support is adequate.

Medicare requires evidence of use and benefit

Medicare requires that clinical benefit be documented between the 31st and 91st day after initiating CPAP therapy. This requires face-to-face clinical reevaluation by the treating physician to document improved symptoms and objective evidence of adherence to use of the device. The devices can store usage patterns, and Medicare requires at least 4 hours per night on 70% of nights during a consecutive 30-day period in the first 3 months of use.

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Alternative therapies may be options for some patients, in particular those who cannot use CPAP or who get no benefit from it. These include oral appliances for those with mild to moderate OSA50–53 and various surgical procedures, eg, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty,54,55 maxillomanibular advancement,56 tracheostomy (standard treatment before CPAP was identified as an effective treatment),57,58 and adenotonsillectomy (in children).59

Supplemental oxygen is not a first-line treatment for OSA and in general has not been found to be very effective, particularly in terms of intermediate cardiovascular outcomes,60–62 although a subset of patients with high loop gain may benefit from it.63 Loop gain is a measure of the tendency of the ventilatory control system to amplify respiration in response to a change, conferring less stable control of breathing.

Several novel alternative therapies are starting to be used. Although all of them have been shown to improve measures of OSA, none is as effective as CPAP in improving OSA severity. New therapies include the nasal expiratory positive airway pressure device,64 oral pressure therapy,65 and hypoglossal nerve stimulation.66

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:1230–1235.

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177:1006–1014.

- Kapur VK, Redline S, Nieto FJ, Young TB, Newman AB, Henderson JA; Sleep Heart Health Research Group. The relationship between chronically disrupted sleep and healthcare use. Sleep 2002; 25:289–296.

- Kapur V, Blough DK, Sandblom RE, et al. The medical cost of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Sleep 1999; 22:749–755.

- Mooe T, Rabben T, Wiklund U, Franklin KA, Eriksson P. Sleep-disordered breathing in men with coronary artery disease. Chest 1996; 109:659–663.

- Schafer H, Koehler U, Ewig S, Hasper E, Tasci S, Luderitz B. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk marker in coronary artery disease. Cardiology 1999; 92:79–84.

- Leung RS, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164:2147–2165.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Second Edition: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL; American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005.

- Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest 1995; 96:1897–1904.

- Mehra R. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: exploring pathophysiology and existing data. Curr Resp Med Rev 2007; 3:258–269.

- Mehra R, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, et al. Soluble interleukin 6 receptor: a novel marker of moderate to severe sleep-related breathing disorder. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1725–1731.

- Mehra R, Xu F, Babineau DC, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and prothrombotic biomarkers: cross-sectional results of the Cleveland Family Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182:826–833.

- Mehra R, Storfer-Isser A, Tracy R, Jenny N, Redline S. Association of sleep disordered breathing and oxidized LDL [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181:A2474.

- Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al; Sleep Heart Health Study. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173:910–916.

- Mehra R, Xu F, Babineau DC, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and prothrombotic biomarkers: cross-sectional results of the Cleveland Family Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182:826–833.

- Monahan K, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, et al. Triggering of nocturnal arrhythmias by sleep-disordered breathing events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:1797–1804.

- Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2003; 107:2589–2594.

- Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulmonary vein antral isolation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: the impact of continuous positive airway pressure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3:445–451.

- Walia H, Strohl KP, Mehra R. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on an atrial arrhythmia in a patient with mild obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2011; 7:397–398.

- Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet 2005; 365:1046–1053.

- Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182:269–277.

- Wang H, Parker JD, Newton GE, et al. Influence of obstructive sleep apnea on mortality in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1625–1631.

- Khayat R, Abraham W, Patt B, et al. Central sleep apnea is a predictor of cardiac readmission in hospitalized patients with systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 2012; 18:534–540.

- Gami AS, Howard DE, Olson EJ, Somers VK. Day-night pattern of sudden death in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1206–1214.

- Punjabi NM, Caffo BS, Goodwin JL, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2009; 6( 8):e1000132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000132.

- Young T, Blustein J, Finn L, Palta M. Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a population-based sample of employed adults. Sleep 1997; 20:608–613.

- Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165:1217–1239.

- Lin CM, Davidson TM, Ancoli-Israel S. Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea and treatment implications. Sleep Med Rev 2008; 12:481–496.

- Shaher E, Redline S, Young T, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:1186–1192.

- Young T, Finn L, Austin D, Peterson A. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:1181–1185.

- Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, Estline E, Chinn A, Fell R. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152:1946–1949.

- Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al; Sleep Heart Health Study Research Group. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:893–900.

- Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, Tosteson TD, Strohl KP, Spry K. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and Caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155:186–192. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 155:1820.

- Sutherland K, Lee RWW, Cistulli PA. Obesity and craniofacial structure as risk factors for obstructive sleep apnoea: impact of ethnicity. Respirology 2012; 17:213–222.

- Schwab RJ, Gupta KB, Gefter WB, Metzger LJ, Hoffman EA, Pack AI. Upper airway and soft tissue anatomy in normal subjects and patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Significance of the lateral pharyngeal walls. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152:1673–1689.

- Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA 2000; 283:1829–1836.

- Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991; 14:540–545.

- Krieger J, Imbs J-L, Schmidt M, Kurtz D. Renal function in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:1337–1340.

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2008; 108:812–821.

- Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Bass L. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngal Head Neck Surg 2002; 127:13–21.

- Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep 1999; 22:667–689.

- Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, et al; Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable Monitoring Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2007; 3:737–747.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). MLN Matters 2008. www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM6048.pdf. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA 2000; 284:3015–3021.

- Guardiano SA, Scott JA, Ware JC, Schechner SA. The long-term results of gastric bypass on indexes of sleep apnea. Chest 2003; 124:1615–1619.

- Crooks PF. Surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Annu Rev Med 2006; 57:243–264.

- Dixon JB, Schachter LM, O’Brien PE, et al. Surgical vs conventional therapy for weight loss treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 308:1142–1149.

- Bazzano LA, Khan Z, Reynolds K, He J. Effect of nocturnal nasal continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in obstructive sleep apnea. Hypertension 2007; 50:417–423.

- Logan AG, Perlikowski SM, Mente A, et al. High prevalence of unrecognized sleep apnoea in drug-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens 2001; 19:2271–2277.

- Kushida CA, Morgenthaler TI, Littner MR, et al; American Academy of Sleep. Practice parameters for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances: an update for 2005. Sleep 2006; 29:240–243.

- Otsuka R, Ribeiro de Almeida F, Lowe AA, Linden W, Ryan F. The effect of oral appliance therapy on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2006; 10:29–36.

- Yoshida K. Effect on blood pressure of oral appliance therapy for sleep apnea syndrome. Int J Prosthodont 2006; 19:61–66.

- Inazawa T, Ayuse T, Kurata S, et al. Effect of mandibular position on upper airway collapsibility and resistance. J Dent Res 2005; 84:554–558.

- Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1981; 89:923–934.

- Schwab RJ. Imaging for the snoring and sleep apnea patient. Dent Clin North Am 2001; 45:759–796.

- Prinsell JR. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 2002; 133:1489–1497.

- Thatcher GW, Maisel RH. The long-term evaluation of tracheostomy in the management of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope 2003; 113:201–204.

- Conway WA, Victor LD, Magilligan DJ, Fujita S, Zorick FJ, Roth T. Adverse effects of tracheostomy for sleep apnea. JAMA 1981; 246:347–350.

- Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al; Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT). A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:2366–2376.

- Gottlieb DJ, Craig SE, Lorenzi-Filho G, et al. Sleep apnea cardiovascular clinical trials-current status and steps forward: The International Collaboration of Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Trialists. Sleep 2013; 36:975–980.

- Loredo JS, Ancoli-Israel S, Kim EJ, Lim WJ, Dimsdale JE. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure versus supplemental oxygen on sleep quality in obstructive sleep apnea: a placebo-CPAP-controlled study. Sleep 2006; 29:564–571.

- Phillips BA, McConnell JW, Smith MD. The effects of hypoxemia on cardiac output. A dose-response curve. Chest 1988; 93:471–475.

- Wellman A, Malhotra A, Jordan AS, Stevenson KE, Gautam S, White DP. Effect of oxygen in obstructive sleep apnea: role of loop gain. Respire Physiol Neurobiol 2008; 162:144–151.

- Berry RB, Kryger MH, Massie CA. A novel nasal expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) device for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2011; 34:479–485.

- Colrain IM, Black J, Siegel LC, et al. A multicenter evaluation of oral pressure therapy for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2013; 14:830–837.

- Strollo PJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, et al; STAR Trial Group. Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:139–149.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is common and poorly recognized and, if untreated, leads to serious health consequences. This article discusses the epidemiology of OSA, describes common presenting signs and symptoms, and reviews diagnostic testing and treatment options. Adverse health effects related to untreated sleep apnea are also discussed.

COMMON, POORLY RECOGNIZED, AND COSTLY IF UNTREATED

OSA is very common in the general population and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. An estimated 17% of the general adult population has OSA, and the numbers are increasing with the obesity epidemic. Nearly 1 in 15 adults has at least moderate sleep apnea,1,2 and approximately 85% of cases are estimated to be undiagnosed.3 A 1999 study estimated that untreated OSA resulted in approximately $3.4 billion in additional medical costs per year in the United States,4 a figure that is likely to be higher now, given the rising prevalence of OSA. The prevalence of OSA in primary care and subspecialty clinics is even higher than in the community, as more than half of patients who have diabetes or hypertension and 30% to 40% of patients with coronary artery disease are estimated to have OSA.5–7

REPETITIVE UPPER-AIRWAY COLLAPSE

During sleep, parasympathetic activity is enhanced and the muscle tone of the upper airway is decreased, particularly in the pharyngeal dilator muscles. Still, even in the supine position, a healthy person maintains patency of the airway and adequate airflow during sleep.

OSA is characterized by repetitive complete or partial collapse of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in an apneic or hypopneic event, respectively, and often causing snoring from upper-airway tissue vibration.

People who are susceptible to OSA typically have a smaller, more collapsible airway that is often less distensible and has a higher critical closing pressure. Radiographic and physiologic data have shown that the airway dimensions of patients with OSA are smaller than in those without OSA. The shape of the airway of a patient with OSA is often elliptical, given the extrinsic compression of the lateral aspects of the airway by increased size of the parapharyngeal fat pads. OSA episodes are characterized by closure of the upper airway and by progressively increasing respiratory efforts driven by chemoreceptor and mechanoreceptor stimuli, culminating in an arousal from sleep and a reopening of the airway.

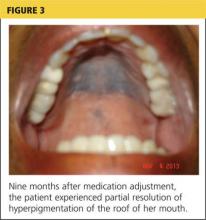

The disease-defining metric used for assessing OSA severity is the apnea-hypopnea index, ie, the number of apneas and hypopneas that occur per hour of sleep.8 An apneic or hypopneic event is identified during polysomnography by the complete cessation of airflow or by a reduction in airflow for 10 seconds or longer (Figure 1).

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES IF UNTREATED

Untreated sleep apnea causes numerous pathophysiologic perturbations, including chronic intermittent hypoxia, ventilatory overshoot hyperoxia, increased sympathetic nervous system activity, intrathoracic pressure swings, hypercapnea, sleep fragmentation, increased arousals, reduced sleep duration, and fragmentation of rapid-eye-movement sleep.

Intermittent hypoxia activates the sympathetic nervous system and causes pulmonary vasoconstriction, with increases in pulmonary arterial pressures and myocardial workload. Sympathetic activation, ascertained by peroneal microneurography, has been shown to be increased not only during sleep but also persisting during wakefulness in patients with untreated OSA vs those without OSA.9 Autonomic nervous system fluctuations accompany apneic episodes, resulting in enhanced parasympathetic tone and sympathetic activation associated with a rise in blood pressure and heart rate that occur after the respiratory event.

Intermediate pathways that link the negative pathophysiologic effects of OSA with adverse health outcomes include increased systemic inflammation, increased oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance, hypercoagulability, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic dysfunction.

As a result, a variety of adverse clinical outcomes are associated with untreated OSA, including systemic hypertension, ischemic heart disease and atherosclerosis, diastolic dysfunction, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, increased risk of death, and sudden death, as well as noncardiovascular outcomes such as gout, neurocognitive deficits, and mood disorders.10

Inflammatory and atherogenic effects

Increased levels of markers of systemic inflammation, prothrombosis, and oxidative stress have been observed in OSA and may be key pathophysiologic links between OSA and cardiovascular sequelae. OSA has been associated with up-regulation of a number of inflammatory mediators: interleukin (IL) 6, soluble IL-6 receptor, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and C-reactive protein. Soluble IL-6 levels in particular are higher in people who have sleep-disordered breathing, as reflected by the apnea-hypopnea index independent of obesity, with relationships stronger in the morning than in the evening. This likely reflects the overnight OSA-related physiologic stress.11

Thrombotic potential is also enhanced, with higher levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, fibrinogen, P-selectin, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Some of these factors normally have a diurnal cycle, with higher levels in the morning, but in OSA, increasing OSA severity is associated with increased prothrombotic potential in the morning hours. Of interest, levels of these substances showed a plateau effect, rising in people who had only mildly elevated apnea-hypopnea indices and then leveling off.12 Intermittent hypoxia followed by ventilatory overshoot hyperoxia, characteristic of sleep apnea, provides the ideal environment for augmentation of oxidative stress, with evidence of increased oxidation of serum proteins and lipids. Hypoxia and oxygen-derived free radicals may result in cardiac myocyte injury. Experimental data demonstrate that intermittent hypoxia combined with a high-fat diet results in synergistic acceleration of evidence of atherogenic lesions.

Patients with OSA also have evidence of endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia, all pathways that can facilitate the progression of atherosclerosis in OSA.13–15

Cardiac arrhythmias

In the Sleep Heart Health Study, a multicenter epidemiologic study designed to examine the relationships of OSA and cardiovascular outcomes, those who had moderate to severe OSA had a risk of ventricular and atrial arrhythmias two to four times higher than those without OSA, even after correction for the confounding influences of obesity and underlying cardiovascular risk.14 These findings were corroborated in subsequent work highlighting monotonic dose-response relationships with increasing OSA severity and increased odds of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in a cohort of about 3,000 older men.11 Additional compelling evidence of a causal relationship is that the risk of discrete arrhythmic events is markedly increased after a respiratory disturbance in sleep.16

In patients who successfully underwent cardioversion for atrial fibrillation, those who had sleep apnea but were not treated with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) had a much higher rate of recurrence of atrial fibrillation during the subsequent year than those with CPAP-treated sleep apnea and than controls never diagnosed with sleep apnea. In the untreated patients with sleep apnea, the mean nocturnal fall in oxygen saturation was significantly greater in those who had recurrence of atrial fibrillation than in those who did not, suggesting hypoxia as an important mechanism contributing to atrial fibrillation.17

Since then, several other retrospective studies have shown similar findings after pulmonary vein antrum isolation and ablation in terms of reduction of atrial fibrillation recurrence with CPAP treatment in OSA.18

Walia et al19 described a patient with moderate sleep apnea who underwent a split-night study. During the baseline part of the study, the patient had about 18 ectopic beats per minute. During the second portion of the study while CPAP was applied, progressively fewer ectopic beats occurred as airway pressure was increased until a normal rhythm without ectopic beats was achieved at the goal treatment CPAP pressure setting.

Cardiovascular disease, stroke, and death

Marin et al20 followed about 1,500 men for 10 years, including some who had severe OSA, some with sleep apnea who were treated with CPAP, and controls. The risk of nonfatal and fatal cardiovascular disease events was nearly three times higher in those with severe disease than in healthy participants. Those treated with CPAP had a risk approximately the same as in the control group.

The Sleep Heart Study followed approximately 6,000 people with untreated sleep apnea for a median of nearly 9 years. It found a significant association between the apnea-hypopnea index and ischemic stroke, especially in men.21 Survival in patients with heart failure is also associated with the degree of OSA; patients with more severe disease (an apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15) have a nearly three times greater risk of death than those with no disease or only mild disease (apnea-hypopnea index < 15).22

From the standpoint of health care utilization, findings that central sleep apnea predicts an increased risk of hospital readmission in heart failure are of particular interest.23

People with OSA are at increased risk of nocturnal sudden cardiac death.24 Sleep apnea is also associated with an increased overall death rate, and the higher the apnea-hypopnea index, the higher the death rate,25 even after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and underlying cardiovascular risk, with findings most pronounced in men under age 70.

Motor vehicle accidents

The need for caution during driving should be discussed with every patient, as motor vehicle accidents are an immediate danger to the patient and others. The association with motor vehicle accidents is independent of sleepiness, and drivers with sleep apnea often do not perceive performance impairment. Young et al26 found that men who snored were 3.4 times as likely to have an accident over a 5-year period, and that men and women with an apnea-hypopnea index greater than 15 were more than 7 times as likely to have multiple accidents over a 5-year period, highlighting the importance of discussing, documenting, and expeditiously diagnosing and treating OSA, particularly in those who report drowsiness while driving.

CLINICAL RISK FACTORS

Risk factors can be divided into nonmodifiable and modifiable ones.

Nonmodifiable factors

Age. Bimodal distributions in OSA prevalence have been observed; ie, that the pediatric population and people who are middle-aged have the highest prevalence of OSA. A linear relationship between sleep apnea prevalence and age until about age 65 was identified in data from the Sleep Heart Health Study.27 After that, the prevalence rates plateau; it is unclear if this is secondary to natural remission of the disease after a certain age or because patients with more severe disease have died by that age (ie, survivorship bias), blunting an increase in prevalence.

Sex. Men develop sleep apnea at a rate three to five times that of women. Several explanations have been proposed to account for this.28,29 Sex hormones are one factor; women with sleep apnea on hormone replacement therapy have a significantly less-severe sleep apnea burden than other postmenopausal women,30 suggesting a positive effect from estrogen. Sex-based differences in fat distribution, length and collapsibility of the upper airway, genioglossal activity, neurochemical control mechanisms, and arousal response may also contribute to prevalence differences between men and women.

As with coronary artery disease, the presentation of sleep apnea may be atypical in women, particularly around menopause. Sleep apnea should be considered in women who have snoring and daytime sleepiness.

Race. Whites, African Americans, and Asians have a similar prevalence of sleep apnea, but groups differ in obesity rates and craniofacial anatomy.31–34 Asians tend to have craniofacial skeletal restriction. African Americans are more likely to have upper-airway soft-tissue risk and to develop more severe OSA. Whites tend to have both craniofacial and soft-tissue risk. For those with craniofacial anatomy predisposing to OSA, even mild obesity can make it manifest.

Syndromes that predispose to OSA can include craniofacial structural abnormalities, connective tissue problems, or alterations in ventilatory control (eg, Marfan, Down, and Pierre Robin syndromes).

Modifiable risk factors

Obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) is a firmly established risk factor, but not all obese patients develop obstructive sleep apnea, and not all people with sleep apnea are obese.

Obesity increases risk by altering the geometry and function of the upper airway, increasing collapsibility. The changes are particularly pronounced in the lateral aspects of the pharynx.35

Obesity also affects respiratory drive, likely in part from leptin resistance. Load compensation is another contributing factor: the increased mass in the thorax and abdomen increases the work of breathing and reduces functional residual capacity, increasing oxygen demands and leading to atelectasis and ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

Although obesity is an important risk factor, it is important to recognize that obesity is not the only one to consider: most people with an apnea-hypopnea index of 5 or greater are not obese. The relationship between body mass index and sleep apnea is weaker in children and in the elderly, probably because other risk factors are more pronounced.36

Craniofacial structural abnormalities such as retrognathia (abnormal posterior position of the mandible) and micrognathia (undersized mandible) can increase the risk of OSA because of a resulting posteriorly displaced genioglossus muscle. Other conditions can alter chemosensitivity, affecting the pH and carbon dioxide level of the blood and therefore affecting ventilatory control mechanisms, making the person more prone to developing sleep apnea. Children and young adults may have tonsillar tissue that obstructs the airway.

The site of obstruction can be behind the palate (retropalatal), behind the tongue (retroglossal), or below the pharynx (hypopharyngeal). This helps explain why positive air way pressure—unlike surgery, which addresses a specific area—is often successful, as it serves to splint or treat all aspects of the airway.

FATIGUE, SLEEPINESS, SNORING, RESTLESS SLEEP

Sleep apnea can result in presentation of multiple signs and symptoms (Table 1).

Daytime sleepiness and fatigue are the most common symptoms. Although nonspecific, they are often quite pronounced. Two short questionnaires—the Epworth Sleepiness Scale37 and the Fatigue Severity Scale—can help distinguish between these two symptoms and assess their impact on a patient’s daily life. In the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, the patient rates his or her chance of dozing on a 4-point scale (0 = would never doze, to 3 = high chance of dozing) in eight situations:

- Sitting and reading

- Watching television

- Sitting inactive in a public place

- As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break

- Lying down to rest in the afternoon

- Sitting and talking to someone

- Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol

- In a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic.

A score of 10 or more is consistent with significant subjective sleepiness.

The Fatigue Severity Scale assesses the impact of fatigue on daily living.

Snoring is a common and specific symptom of sleep apnea; however, not all patients who snore have OSA.

Restlessness during sleep is very common—patients may disturb their bed partner by moving around a lot during sleep or report that the sheets are “all over the place” by morning.

Nocturia can also be a sign of sleep apnea and can contribute to sleep fragmentation. A proposed mechanism of this symptom includes alterations of intrathoracic pressure resulting in atrial stretch, which release atrial natriuretic peptide, leading to nocturia. Treating with CPAP has been found to reduce levels of atrial natriuretic peptide, contributing to better sleep.38

Morning headache may occur and is likely related to increased CO2 levels, which appear to culminate in the morning hours. End-tidal or transcutaneous CO2 monitoring during polysomnography can help elucidate the presence of sleep-related hypoventilation.

Libido is often diminished and can actually be improved with CPAP. This is therefore an important point to discuss with patients, as improved libido can often serve as an incentive for adherence to OSA treatment.

Insomnia exists in about 15% of patients, primarily as a result of sleep apnea-related with treatment.

Sweating, particularly forehead sweating associated with sleep apnea, more commonly occurs in children.

The STOP-BANG questionnaire (Table 2)39 was primarily validated in preoperative anesthesia testing. However, because of its ease of use and favorable performance characteristics, it is increasingly used to predict the likelihood of finding OSA before polysomnography. A score of 3 or more has a sensitivity of 93%.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION PROVIDES CLUES

Although the physical examination may be normal, certain findings indicate risk (Table 3). Obesity alone is not an accepted indication for polysomnography unless there are concomitant worrisome signs or symptoms. Of note, those who are morbidly obese (BMI > 40 kg/m2) have a prevalence of sleep apnea greater than 70%.

The classification by Friedman et al40 provides an indicator of risk. The patient is examined with the mouth opened wide and the tongue in a neutral natural position. Grades:

- I—Entire uvula and tonsils are visible

- II—Entire uvula is visible, but tonsils are not

- III—Soft palate is visible, but uvula is not

- IV—Only the hard palate is visible.

Especially in children and young adults, enlarged tonsils (or “kissing tonsils”) and a boggy edematous uvula set the stage for obstructive sleep apnea.

DIAGNOSIS REQUIRES SLEEP TESTING

A sleep study is the primary means of diagnosing OSA. Polysomnography includes electrooculography to determine when rapid-eye-movement sleep occurs; electromyography to measure muscle activity in the chin to help determine onset of sleep, with peripheral leads in the leg to measure leg movements; electroencephalography (EEG) to measure neural activity; electrocardiography; pulse oximetry to measure oxygen saturation; measurement of oronasal flow; and measurements of chest wall effort and body position using thoracic and abdominal belts that expand and contract with breathing; and audio recording to detect snoring.

Attended polysomnography requires the constant presence of a trained sleep technologist to monitor for technical issues and patient adherence.

End-tidal CO2 monitoring is a reasonable method to detect sleep-related hypoventilation but is not routinely performed in the United States. Transcutaneous CO2 monitoring is a different way to monitor CO2 used in the setting of positive airway pressure.

Polysomnography in a normal patient shows a regular pattern of increasing and decreasing airflow with inspiration and expiration while stable oxygen saturation is maintained.

In contrast, polysomnography of a patient with sleep apnea shows repetitive periods of no airflow, oxygen desaturation, and often evidence of thoracoabdominal paradox, punctuated by arousals on EEG associated with sympathetic activation (Figure 1). When the patient falls asleep, upper-airway muscle tone is reduced, causing an apneic event with hypoxia and pleural pressure swings. These prompt arousals with sympathetic activation that reestablish upper-airway muscle tone, allowing ventilation and reoxygenation to resume with a return to sleep.

Apnea-hypopnea index indicates severity

Sleep apnea severity is graded using the apnea-hypopnea index, ie, the number of apneic and hypopneic events per hour of sleep (Table 4).41 Events must last at least 10 seconds to be considered, ie, two consecutive missed breaths based on an average normal respiratory rate of about 12 breaths per minute for the typical adult.

The apnea-hypopnea index usually correlates with the severity of oxygen desaturation and with electrocardiographic abnormalities, including tachybradycardia and arrhythmias.

Although history, physical examination, and prediction tools are helpful in determining the likelihood that a patient has OSA, only polysomnography testing can establish the diagnosis. To diagnose OSA, 15 or more obstructive events per hour must be observed by polysomnography, or at least 5 events per hour with one of the following:

- Daytime sleepiness, sleep attacks, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, or insomnia

- Waking with breath-holding, gasping, or choking

- Observer-reported loud snoring or breathing interruptions.41

Split-night study determines diagnosis and optimum treatment

The split-night study has two parts: the first is diagnostic polysomnography, followed by identification of the positive airway pressure that optimally treats the sleep apnea. The apnea-hypopnea index guides the need for the split-night study, with 40 being the established threshold according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

A home sleep study is appropriate for some patients

Home sleep testing is typically more limited than standard polysomnography; it monitors airflow, effort, and oxygenation. The test is intended for adults with a high pretest probability of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (STOP-BANG score ≥ 3). It is not intended for screening of asymptomatic patients or for those with coexisting sleep disorders (eg, central sleep apnea, sleep hypoventilation, periodic limb movements, insomnia, circadian rhythm disorders, parasomnias, narcolepsy) or medical disorders (eg, moderate to severe heart failure or other cardiac disease, symptomatic neurologic disease, moderate to severe pulmonary disease).42 Since March 2008, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has covered CPAP for obstructive sleep apnea based on diagnosis by home sleep study testing.43

TREATMENT OF SLEEP APNEA

Basic steps for reducing OSA are:

Weight loss. Even small weight changes can significantly affect the severity of sleep apnea, perhaps even leading to a reassessment of the degree of OSA and CPAP requirements. Longitudinal epidemiologic data demonstrate that a 10% weight loss correlates with a 26% reduction in the apnea-hypopnea index, and conversely, a 10% weight gain is associated with a 32% increase.44

Some studies have found that bariatric surgery cures OSA in 75% to 88% of cases, independent of approach.45,46 However, a trial in 60 obese patients with OSA who were randomized to either a low-calorie diet or bariatric surgery found no statistical difference in the apnea-hypopnea index between the two groups despite greater weight loss in the surgery group.47

Avoiding certain medications. Benzodiazepines, narcotics, and alcohol reduce upper airway muscle tone and should be avoided. No medications are associated with improvement of OSA, although acetazolamide may be used to treat central sleep apnea.

Positional therapy. Sleeping on the back exacerbates the problem. Supine-related OSA occurs as a result of several factors, including gravity, airway anatomy, airway critical closing pressures, and effects on upper-airway dilator muscle function.

Sleep hygiene. General recommendations to engage in behaviors to promote sleep are recommended, including keeping consistent sleep-wake times, not watching television in bed, and avoidance of caffeine intake, particularly within 4 to 6 hours of bedtime.

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY

Nasal CPAP is the treatment of choice and is successful in 95% of patients when used consistently. It is not as costly as surgery, and results in improved long-term survival compared with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Another advantage is that the pressure can be retitrated as the patient’s condition changes, for example after a weight change or during pregnancy.

More than 15 randomized controlled trials have examined the effect of sleep apnea treatment with CPAP compared with either sham CPAP or another control. In a meta-analysis, CPAP was found to lead to an average systolic blood pressure reduction of about 2.5 mm Hg and a diastolic blood pressure reduction of 1.8 mm Hg. Although these reductions may seem negligible, benefits may be significant for cardiovascular outcomes.48,49

Challenges to treatment adherence

Adherence is the most commonly discussed problem with CPAP, but long-term adherence rates are comparable to medication compliance—about 60% to 70%. To optimize adherence, communication is important to ensure that problems are identified and addressed as they arise. Showing patients examples of apneic events and oxygen desaturation from their sleep study can enhance their understanding of OSA and its importance. Patients need to understand the serious nature of the disease and that CPAP therapy can significantly improve their quality of life and overall health, particularly from a cardiovascular perspective.

CPAP masks can be uncomfortable, posing a major barrier to compliance. But a number of mask designs are available, such as the nasal mask, the nasal pillow mask, and the oronasal mask. For patients with claustrophobia, the nasal pillow mask is an option, as it does not cover the face.

Some patients note symptoms of nasal congestion, although in many patients CPAP improves it. If congestion is a problem, the use of heated humidification with the machine, intranasal saline or gel, or nasal corticosteroids can help relieve it.

Pressure intolerance is a common problem. For those who feel that the pressure is too high, settings can be adjusted so that the pressure is gradually reduced between inspiration and expiration, ie, the use of expiratory pressure relief or consideration of the use of bilevel positive airway pressure.

Aerophagia (swallowing air) is a less common problem. It can also potentially be relieved with use of bilevel positive airway pressure.

Many patients develop skin irritation, which can be helped with moleskin, available at any pharmacy.

Social stigma can be a problem. Education regarding the importance of the treatment to health is essential.

Machine noise is less of a problem with the new machine models, but if it is a problem, a white-noise device or earplugs may help.

Other measures to improve compliance are keeping the regimen simple and ensuring that family support is adequate.

Medicare requires evidence of use and benefit

Medicare requires that clinical benefit be documented between the 31st and 91st day after initiating CPAP therapy. This requires face-to-face clinical reevaluation by the treating physician to document improved symptoms and objective evidence of adherence to use of the device. The devices can store usage patterns, and Medicare requires at least 4 hours per night on 70% of nights during a consecutive 30-day period in the first 3 months of use.

ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Alternative therapies may be options for some patients, in particular those who cannot use CPAP or who get no benefit from it. These include oral appliances for those with mild to moderate OSA50–53 and various surgical procedures, eg, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty,54,55 maxillomanibular advancement,56 tracheostomy (standard treatment before CPAP was identified as an effective treatment),57,58 and adenotonsillectomy (in children).59

Supplemental oxygen is not a first-line treatment for OSA and in general has not been found to be very effective, particularly in terms of intermediate cardiovascular outcomes,60–62 although a subset of patients with high loop gain may benefit from it.63 Loop gain is a measure of the tendency of the ventilatory control system to amplify respiration in response to a change, conferring less stable control of breathing.

Several novel alternative therapies are starting to be used. Although all of them have been shown to improve measures of OSA, none is as effective as CPAP in improving OSA severity. New therapies include the nasal expiratory positive airway pressure device,64 oral pressure therapy,65 and hypoglossal nerve stimulation.66

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is common and poorly recognized and, if untreated, leads to serious health consequences. This article discusses the epidemiology of OSA, describes common presenting signs and symptoms, and reviews diagnostic testing and treatment options. Adverse health effects related to untreated sleep apnea are also discussed.

COMMON, POORLY RECOGNIZED, AND COSTLY IF UNTREATED

OSA is very common in the general population and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. An estimated 17% of the general adult population has OSA, and the numbers are increasing with the obesity epidemic. Nearly 1 in 15 adults has at least moderate sleep apnea,1,2 and approximately 85% of cases are estimated to be undiagnosed.3 A 1999 study estimated that untreated OSA resulted in approximately $3.4 billion in additional medical costs per year in the United States,4 a figure that is likely to be higher now, given the rising prevalence of OSA. The prevalence of OSA in primary care and subspecialty clinics is even higher than in the community, as more than half of patients who have diabetes or hypertension and 30% to 40% of patients with coronary artery disease are estimated to have OSA.5–7

REPETITIVE UPPER-AIRWAY COLLAPSE

During sleep, parasympathetic activity is enhanced and the muscle tone of the upper airway is decreased, particularly in the pharyngeal dilator muscles. Still, even in the supine position, a healthy person maintains patency of the airway and adequate airflow during sleep.

OSA is characterized by repetitive complete or partial collapse of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in an apneic or hypopneic event, respectively, and often causing snoring from upper-airway tissue vibration.