User login

The Discount Dilemma

Health care reform has triggered considerable discussion both in print and online about the administrative problems it has created for private practitioners, including decreased cash flow, increased paperwork and business expenses, and an increasing number of high-deductible insurance exchanges with the infamous 90-day “grace periods.” Extending discounts to patients who pay at the time of service or out of pocket may mitigate damage caused by all 3 of these issues; however, caution is necessary, as discounts often can run afoul of federal and state laws, including anti-kickback statutes,1 the anti-inducement provision of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act,2 the Medicare exclusion provision,3 and state insurance antidiscrimination provisions.4

Avoid Kickback Penalties From Patient Discounts

From a legal standpoint, any discount is technically a kickback of sorts because you are returning part of your fee to the patient, and many laws designed to thwart true kickbacks can apply to patient discounts. Take the relatively straightforward case of time-of-service discounts for cosmetic procedures and other services not normally covered by insurance. You would think that these transactions are strictly between you and your patients, but if these discounts appear to be marketing incentives to attract patients, you may face a penalty.5

Patient discounts also may impact third-party payers. Many provider agreements contain “most favored nation” clauses, which require you to automatically give that payer the lowest price you offer to anyone else, regardless of what would be paid otherwise. In other words, the payer could demand the same discount you offer any individual patient. A time-of-service discount is, of course, exactly that: it is offered only when payment is made immediately. Third parties never pay at the time of service and would not be entitled to it, but they may try to invoke their agreement.

If you want to extend discounts for covered services, you must be sure that the discounted fee you charge the patient also is reflected on the claim submitted to the insurer. Billing the insurer more than you charged the patient invites a charge of fraud.6 It is important to avoid discounting so regularly that the discounted fee becomes your usual and customary rate in the eyes of the insurer.

Waiving Costs and Kickbacks

Waiving coinsurance and deductibles can be trouble too, particularly with Medicare and Medicaid. You might intend it as a good deed, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will see it as an inducement or kickback, especially if you do it routinely, and similar to private carriers, they will consider the discounted fee your new customary fee. The CMS has no problem with an occasional waiver, especially “after determining in good faith that the individual is in financial need,” according to the Office of Inspector General,7 but thorough documentation is necessary in such cases.

Waiving co-pays for privately insured patients can be equally problematic. Nearly all insurers impose a contractual duty on providers to make a reasonable effort to collect applicable co-pays and/or deductibles. They view the routine waiver of patient payments as a breach of contract, and litigation may occur against providers who flout this requirement.8 As with the CMS, accommodating patients with individually documented financial limitations is acceptable, but if there is a pattern of routine waivers and a paucity of documentation, you will have difficulty defending it.

Antidiscrimination Laws

In addition to kickback laws, some states also have antidiscrimination laws that forbid lower charges to any subset of insurance payers or to direct payers.4 Some states make specific exceptions for legitimate discounts, such as individual cases of financial hardship, or if you pass along your lower billing and collection expenditures to patients who pay immediately, but other states do not.

Determining Discount Amounts

The discount amount depends on the physician’s situation and deserves careful consideration. If the amount or percentage that you choose to offer as a discount is completely out of proportion with the administrative costs of submitting paperwork as well as the hassles associated with waiting for third-party payments, you could be accused of running a discount policy that is in effect a de facto increase to insurance carriers, which also could result in charges of fraud.2

In cases of legitimate financial hardship, the most effective and least problematic strategy may be to offer a sliding scale. Many large clinics and community agencies as well as all hospitals have written policies for this system, often based on federal poverty guidelines. To avoid any potential issues, contact your local social service agencies and welfare clinics, learn the community standard in your area, and formulate a written policy with guidelines for determining a patient’s indigence.

Final Thoughts

Consistency of administration, objectivity in policies, and documentation of individual eligibility will ensure that the discounts you offer patients are in line with legal and payer regulations. Before you establish a discount policy, be sure to check your state’s applicable laws, and as always, run everything by your attorney.

1. Guidance on the federal anti-kickback law. Health Resources and Services Administration Web site. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/policiesregulations/policies/pal199510.html. Accessed October 22, 2014.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. A roadmap for new physicians: fraud & abuse laws. Office of Inspector General Web site.http://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/01laws.asp. Accessed October 21, 2014.

3. Exclusion of certain individuals and entities from participation in Medicare and State health care programs, 42 USC §1320a–7 (2011).

4. Non-discrimination in health care, 42 USC §300gg–5 (2014).

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Offering gifts and other inducements to beneficiaries. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/SABGiftsandInducements.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed October 21, 2014.

6. The challenge of health care fraud. National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association Web site. http://www.nhcaa.org/resources/health-care-anti-fraud-resources/the-challenge-of-health-care-fraud.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2014.

7. US Department of Health & Human Services. Hospital discounts offered to patients who cannot afford to pay their hospital bills. Office of Inspector General Web site. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2004/FA021904hospitaldiscounts.pdf. Published February 2, 2004. Accessed October 16, 2014.

8. Merritt M. Forgiving patient copays can lead to unforgiving consequences. Physicians Practice Web site. http://www.physicianspractice.com/blog/forgiving-patient-copays-can-lead-unforgiving-consequences. Published December 15, 2013. Accessed October 21, 2014.

Health care reform has triggered considerable discussion both in print and online about the administrative problems it has created for private practitioners, including decreased cash flow, increased paperwork and business expenses, and an increasing number of high-deductible insurance exchanges with the infamous 90-day “grace periods.” Extending discounts to patients who pay at the time of service or out of pocket may mitigate damage caused by all 3 of these issues; however, caution is necessary, as discounts often can run afoul of federal and state laws, including anti-kickback statutes,1 the anti-inducement provision of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act,2 the Medicare exclusion provision,3 and state insurance antidiscrimination provisions.4

Avoid Kickback Penalties From Patient Discounts

From a legal standpoint, any discount is technically a kickback of sorts because you are returning part of your fee to the patient, and many laws designed to thwart true kickbacks can apply to patient discounts. Take the relatively straightforward case of time-of-service discounts for cosmetic procedures and other services not normally covered by insurance. You would think that these transactions are strictly between you and your patients, but if these discounts appear to be marketing incentives to attract patients, you may face a penalty.5

Patient discounts also may impact third-party payers. Many provider agreements contain “most favored nation” clauses, which require you to automatically give that payer the lowest price you offer to anyone else, regardless of what would be paid otherwise. In other words, the payer could demand the same discount you offer any individual patient. A time-of-service discount is, of course, exactly that: it is offered only when payment is made immediately. Third parties never pay at the time of service and would not be entitled to it, but they may try to invoke their agreement.

If you want to extend discounts for covered services, you must be sure that the discounted fee you charge the patient also is reflected on the claim submitted to the insurer. Billing the insurer more than you charged the patient invites a charge of fraud.6 It is important to avoid discounting so regularly that the discounted fee becomes your usual and customary rate in the eyes of the insurer.

Waiving Costs and Kickbacks

Waiving coinsurance and deductibles can be trouble too, particularly with Medicare and Medicaid. You might intend it as a good deed, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will see it as an inducement or kickback, especially if you do it routinely, and similar to private carriers, they will consider the discounted fee your new customary fee. The CMS has no problem with an occasional waiver, especially “after determining in good faith that the individual is in financial need,” according to the Office of Inspector General,7 but thorough documentation is necessary in such cases.

Waiving co-pays for privately insured patients can be equally problematic. Nearly all insurers impose a contractual duty on providers to make a reasonable effort to collect applicable co-pays and/or deductibles. They view the routine waiver of patient payments as a breach of contract, and litigation may occur against providers who flout this requirement.8 As with the CMS, accommodating patients with individually documented financial limitations is acceptable, but if there is a pattern of routine waivers and a paucity of documentation, you will have difficulty defending it.

Antidiscrimination Laws

In addition to kickback laws, some states also have antidiscrimination laws that forbid lower charges to any subset of insurance payers or to direct payers.4 Some states make specific exceptions for legitimate discounts, such as individual cases of financial hardship, or if you pass along your lower billing and collection expenditures to patients who pay immediately, but other states do not.

Determining Discount Amounts

The discount amount depends on the physician’s situation and deserves careful consideration. If the amount or percentage that you choose to offer as a discount is completely out of proportion with the administrative costs of submitting paperwork as well as the hassles associated with waiting for third-party payments, you could be accused of running a discount policy that is in effect a de facto increase to insurance carriers, which also could result in charges of fraud.2

In cases of legitimate financial hardship, the most effective and least problematic strategy may be to offer a sliding scale. Many large clinics and community agencies as well as all hospitals have written policies for this system, often based on federal poverty guidelines. To avoid any potential issues, contact your local social service agencies and welfare clinics, learn the community standard in your area, and formulate a written policy with guidelines for determining a patient’s indigence.

Final Thoughts

Consistency of administration, objectivity in policies, and documentation of individual eligibility will ensure that the discounts you offer patients are in line with legal and payer regulations. Before you establish a discount policy, be sure to check your state’s applicable laws, and as always, run everything by your attorney.

Health care reform has triggered considerable discussion both in print and online about the administrative problems it has created for private practitioners, including decreased cash flow, increased paperwork and business expenses, and an increasing number of high-deductible insurance exchanges with the infamous 90-day “grace periods.” Extending discounts to patients who pay at the time of service or out of pocket may mitigate damage caused by all 3 of these issues; however, caution is necessary, as discounts often can run afoul of federal and state laws, including anti-kickback statutes,1 the anti-inducement provision of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act,2 the Medicare exclusion provision,3 and state insurance antidiscrimination provisions.4

Avoid Kickback Penalties From Patient Discounts

From a legal standpoint, any discount is technically a kickback of sorts because you are returning part of your fee to the patient, and many laws designed to thwart true kickbacks can apply to patient discounts. Take the relatively straightforward case of time-of-service discounts for cosmetic procedures and other services not normally covered by insurance. You would think that these transactions are strictly between you and your patients, but if these discounts appear to be marketing incentives to attract patients, you may face a penalty.5

Patient discounts also may impact third-party payers. Many provider agreements contain “most favored nation” clauses, which require you to automatically give that payer the lowest price you offer to anyone else, regardless of what would be paid otherwise. In other words, the payer could demand the same discount you offer any individual patient. A time-of-service discount is, of course, exactly that: it is offered only when payment is made immediately. Third parties never pay at the time of service and would not be entitled to it, but they may try to invoke their agreement.

If you want to extend discounts for covered services, you must be sure that the discounted fee you charge the patient also is reflected on the claim submitted to the insurer. Billing the insurer more than you charged the patient invites a charge of fraud.6 It is important to avoid discounting so regularly that the discounted fee becomes your usual and customary rate in the eyes of the insurer.

Waiving Costs and Kickbacks

Waiving coinsurance and deductibles can be trouble too, particularly with Medicare and Medicaid. You might intend it as a good deed, but the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will see it as an inducement or kickback, especially if you do it routinely, and similar to private carriers, they will consider the discounted fee your new customary fee. The CMS has no problem with an occasional waiver, especially “after determining in good faith that the individual is in financial need,” according to the Office of Inspector General,7 but thorough documentation is necessary in such cases.

Waiving co-pays for privately insured patients can be equally problematic. Nearly all insurers impose a contractual duty on providers to make a reasonable effort to collect applicable co-pays and/or deductibles. They view the routine waiver of patient payments as a breach of contract, and litigation may occur against providers who flout this requirement.8 As with the CMS, accommodating patients with individually documented financial limitations is acceptable, but if there is a pattern of routine waivers and a paucity of documentation, you will have difficulty defending it.

Antidiscrimination Laws

In addition to kickback laws, some states also have antidiscrimination laws that forbid lower charges to any subset of insurance payers or to direct payers.4 Some states make specific exceptions for legitimate discounts, such as individual cases of financial hardship, or if you pass along your lower billing and collection expenditures to patients who pay immediately, but other states do not.

Determining Discount Amounts

The discount amount depends on the physician’s situation and deserves careful consideration. If the amount or percentage that you choose to offer as a discount is completely out of proportion with the administrative costs of submitting paperwork as well as the hassles associated with waiting for third-party payments, you could be accused of running a discount policy that is in effect a de facto increase to insurance carriers, which also could result in charges of fraud.2

In cases of legitimate financial hardship, the most effective and least problematic strategy may be to offer a sliding scale. Many large clinics and community agencies as well as all hospitals have written policies for this system, often based on federal poverty guidelines. To avoid any potential issues, contact your local social service agencies and welfare clinics, learn the community standard in your area, and formulate a written policy with guidelines for determining a patient’s indigence.

Final Thoughts

Consistency of administration, objectivity in policies, and documentation of individual eligibility will ensure that the discounts you offer patients are in line with legal and payer regulations. Before you establish a discount policy, be sure to check your state’s applicable laws, and as always, run everything by your attorney.

1. Guidance on the federal anti-kickback law. Health Resources and Services Administration Web site. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/policiesregulations/policies/pal199510.html. Accessed October 22, 2014.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. A roadmap for new physicians: fraud & abuse laws. Office of Inspector General Web site.http://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/01laws.asp. Accessed October 21, 2014.

3. Exclusion of certain individuals and entities from participation in Medicare and State health care programs, 42 USC §1320a–7 (2011).

4. Non-discrimination in health care, 42 USC §300gg–5 (2014).

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Offering gifts and other inducements to beneficiaries. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/SABGiftsandInducements.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed October 21, 2014.

6. The challenge of health care fraud. National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association Web site. http://www.nhcaa.org/resources/health-care-anti-fraud-resources/the-challenge-of-health-care-fraud.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2014.

7. US Department of Health & Human Services. Hospital discounts offered to patients who cannot afford to pay their hospital bills. Office of Inspector General Web site. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2004/FA021904hospitaldiscounts.pdf. Published February 2, 2004. Accessed October 16, 2014.

8. Merritt M. Forgiving patient copays can lead to unforgiving consequences. Physicians Practice Web site. http://www.physicianspractice.com/blog/forgiving-patient-copays-can-lead-unforgiving-consequences. Published December 15, 2013. Accessed October 21, 2014.

1. Guidance on the federal anti-kickback law. Health Resources and Services Administration Web site. http://bphc.hrsa.gov/policiesregulations/policies/pal199510.html. Accessed October 22, 2014.

2. US Department of Health & Human Services. A roadmap for new physicians: fraud & abuse laws. Office of Inspector General Web site.http://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/01laws.asp. Accessed October 21, 2014.

3. Exclusion of certain individuals and entities from participation in Medicare and State health care programs, 42 USC §1320a–7 (2011).

4. Non-discrimination in health care, 42 USC §300gg–5 (2014).

5. US Department of Health and Human Services. Offering gifts and other inducements to beneficiaries. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/SABGiftsandInducements.pdf. Published August 2002. Accessed October 21, 2014.

6. The challenge of health care fraud. National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association Web site. http://www.nhcaa.org/resources/health-care-anti-fraud-resources/the-challenge-of-health-care-fraud.aspx. Accessed October 21, 2014.

7. US Department of Health & Human Services. Hospital discounts offered to patients who cannot afford to pay their hospital bills. Office of Inspector General Web site. http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/2004/FA021904hospitaldiscounts.pdf. Published February 2, 2004. Accessed October 16, 2014.

8. Merritt M. Forgiving patient copays can lead to unforgiving consequences. Physicians Practice Web site. http://www.physicianspractice.com/blog/forgiving-patient-copays-can-lead-unforgiving-consequences. Published December 15, 2013. Accessed October 21, 2014.

Practice Points

- Discounts to direct and immediate payers (patients) may run afoul of local and national statutes.

- Routine waiving of co-pays and deductibles can be problematic.

- Consistency of administration, objectivity in policies, and documentation of individual eligibility are essential in private practices.

CME, Procedures, and Advocacy Highlight Hospital Medicine 2013 Kickoff

Hospital Medicine 2013 starts off with a day of learning and advocacy on Capitol Hill.

Hospital Medicine 2013 starts off with a day of learning and advocacy on Capitol Hill.

Hospital Medicine 2013 starts off with a day of learning and advocacy on Capitol Hill.

Clear Cell Fibrous Papule

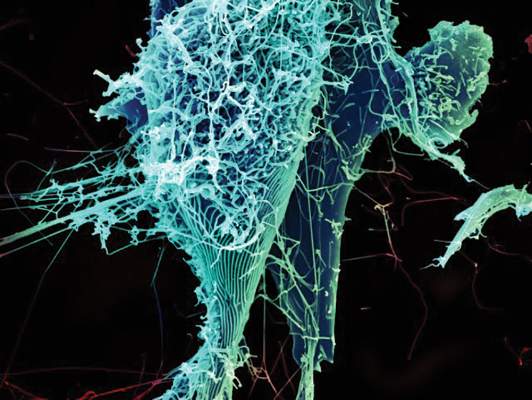

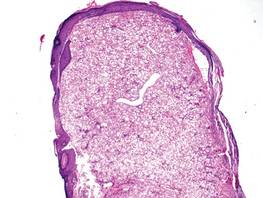

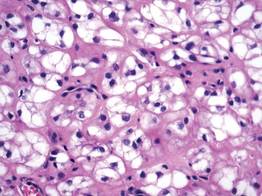

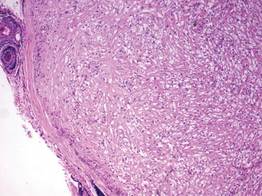

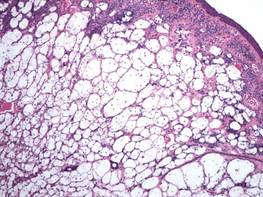

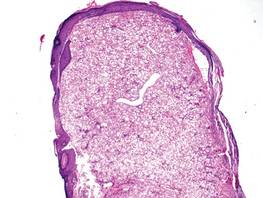

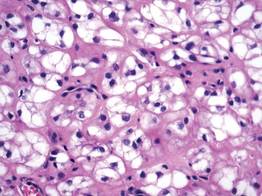

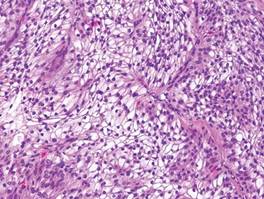

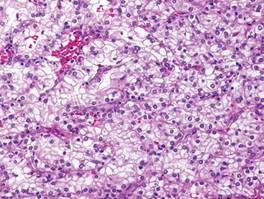

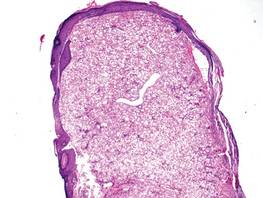

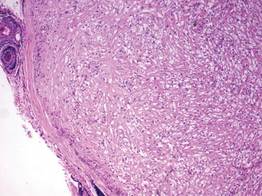

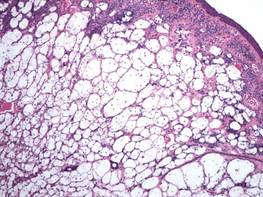

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

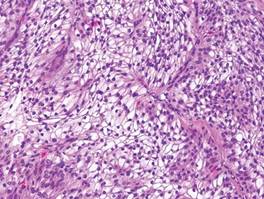

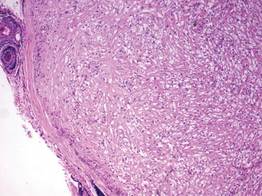

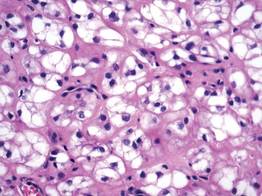

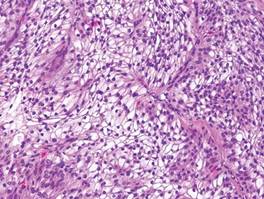

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

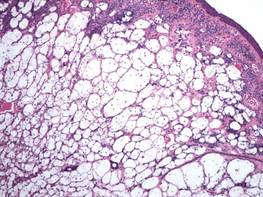

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

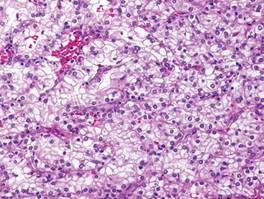

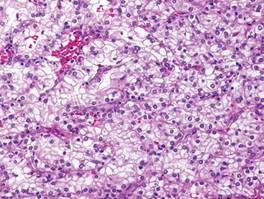

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

Probiotics for Radiation-Caused Diarrhea

Probiotics may help reduce the severity of one of the most common acute adverse effects of radiation—diarrhea. They just might not show results right away. According to a study by researchers from the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec in Canada, the effects of probiotics were positive and most effective in the weeks after radiation treatment.

No prophylactic agents are approved for preventing pelvic radiation enteritis, the researchers note, and evidence is weak for nutritional interventions that have been tried. But recently, more research is pointing to a powerful role for probiotics in a variety of gastrointestinal uses.

This study compared the efficacy of the probiotic Bifilact (Lactobacillus acidophilus LAC-361 and Bifidobacterium longum BB-536) with placebo. The main goal was to find whether probiotics would prevent or delay the incidence of moderate-to-severe radiation-induced diarrhea during a radiotherapy treatment. Secondary goals were to assess whether Bifilact reduced or delayed the need of antidiarrheal medication, reduced intestinal pain, reduced the need for hospitalization, minimized interruptions to radiotherapy treatments, and improved patient well-being.

In the study, 229 patients received either placebo or 1 of 2 Bifilact regimens: a standard dose twice a day or a high dose 3 times a day. Patients recorded their digestive symptoms every day and met with a registered dietitian and radiation oncologist every week during treatment.

Although the differences were not statistically significant, probiotics eventually halved the proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe diarrhea. The mean number of bowel movements per 24 hours was 2.3 in the placebo group, 2.3 in the standard-dose, and 2.1 in the high-dose patients (P = .84). During the treatment, those numbers changed to 2.9, 2.7, and 2.8 bowel movements per day (P = .80), respectively. For patients who underwent surgical procedures before radiation, probiotic intake tended to reduce all levels of diarrhea, especially the most severe grade 4 diarrhea. Median abdominal pain was initially 0 for all groups and < 1 during treatment for all groups (P = .23).

To their knowledge, the researchers say, only 6 human clinical studies have been published regarding using probiotics to prevent acute radiation-induced diarrhea, and only 1 for treating diarrhea after radiotherapy. The 6 studies showed positive results on diarrhea toxicity and/or frequency of bowel movement and/or stool consistency. Two of 3 systematic reviews also found a probable beneficial effect on prevention.

Their own study produced some interesting findings, the researchers say. For one, less diarrhea at 60 days meant the benefit began at the end of the treatment or after it. Patients with a standard dose of probiotic experienced less of the moderate-to-severe diarrhea at the end of treatment or during the 2 weeks following treatment. And after 60 days, 35% of patients in the standard-dose group did not have moderate-to-severe diarrhea, compared with 17% in the placebo group (P = .23). The researchers say the probiotic effect may be delayed because of the time required by bacteria to exert their influence on the inflammatory process.

Source

Demers M, Dagnault A, Desjardins J. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):761-767.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.015.

Probiotics may help reduce the severity of one of the most common acute adverse effects of radiation—diarrhea. They just might not show results right away. According to a study by researchers from the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec in Canada, the effects of probiotics were positive and most effective in the weeks after radiation treatment.

No prophylactic agents are approved for preventing pelvic radiation enteritis, the researchers note, and evidence is weak for nutritional interventions that have been tried. But recently, more research is pointing to a powerful role for probiotics in a variety of gastrointestinal uses.

This study compared the efficacy of the probiotic Bifilact (Lactobacillus acidophilus LAC-361 and Bifidobacterium longum BB-536) with placebo. The main goal was to find whether probiotics would prevent or delay the incidence of moderate-to-severe radiation-induced diarrhea during a radiotherapy treatment. Secondary goals were to assess whether Bifilact reduced or delayed the need of antidiarrheal medication, reduced intestinal pain, reduced the need for hospitalization, minimized interruptions to radiotherapy treatments, and improved patient well-being.

In the study, 229 patients received either placebo or 1 of 2 Bifilact regimens: a standard dose twice a day or a high dose 3 times a day. Patients recorded their digestive symptoms every day and met with a registered dietitian and radiation oncologist every week during treatment.

Although the differences were not statistically significant, probiotics eventually halved the proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe diarrhea. The mean number of bowel movements per 24 hours was 2.3 in the placebo group, 2.3 in the standard-dose, and 2.1 in the high-dose patients (P = .84). During the treatment, those numbers changed to 2.9, 2.7, and 2.8 bowel movements per day (P = .80), respectively. For patients who underwent surgical procedures before radiation, probiotic intake tended to reduce all levels of diarrhea, especially the most severe grade 4 diarrhea. Median abdominal pain was initially 0 for all groups and < 1 during treatment for all groups (P = .23).

To their knowledge, the researchers say, only 6 human clinical studies have been published regarding using probiotics to prevent acute radiation-induced diarrhea, and only 1 for treating diarrhea after radiotherapy. The 6 studies showed positive results on diarrhea toxicity and/or frequency of bowel movement and/or stool consistency. Two of 3 systematic reviews also found a probable beneficial effect on prevention.

Their own study produced some interesting findings, the researchers say. For one, less diarrhea at 60 days meant the benefit began at the end of the treatment or after it. Patients with a standard dose of probiotic experienced less of the moderate-to-severe diarrhea at the end of treatment or during the 2 weeks following treatment. And after 60 days, 35% of patients in the standard-dose group did not have moderate-to-severe diarrhea, compared with 17% in the placebo group (P = .23). The researchers say the probiotic effect may be delayed because of the time required by bacteria to exert their influence on the inflammatory process.

Source

Demers M, Dagnault A, Desjardins J. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):761-767.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.015.

Probiotics may help reduce the severity of one of the most common acute adverse effects of radiation—diarrhea. They just might not show results right away. According to a study by researchers from the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec in Canada, the effects of probiotics were positive and most effective in the weeks after radiation treatment.

No prophylactic agents are approved for preventing pelvic radiation enteritis, the researchers note, and evidence is weak for nutritional interventions that have been tried. But recently, more research is pointing to a powerful role for probiotics in a variety of gastrointestinal uses.

This study compared the efficacy of the probiotic Bifilact (Lactobacillus acidophilus LAC-361 and Bifidobacterium longum BB-536) with placebo. The main goal was to find whether probiotics would prevent or delay the incidence of moderate-to-severe radiation-induced diarrhea during a radiotherapy treatment. Secondary goals were to assess whether Bifilact reduced or delayed the need of antidiarrheal medication, reduced intestinal pain, reduced the need for hospitalization, minimized interruptions to radiotherapy treatments, and improved patient well-being.

In the study, 229 patients received either placebo or 1 of 2 Bifilact regimens: a standard dose twice a day or a high dose 3 times a day. Patients recorded their digestive symptoms every day and met with a registered dietitian and radiation oncologist every week during treatment.

Although the differences were not statistically significant, probiotics eventually halved the proportion of patients with moderate-to-severe diarrhea. The mean number of bowel movements per 24 hours was 2.3 in the placebo group, 2.3 in the standard-dose, and 2.1 in the high-dose patients (P = .84). During the treatment, those numbers changed to 2.9, 2.7, and 2.8 bowel movements per day (P = .80), respectively. For patients who underwent surgical procedures before radiation, probiotic intake tended to reduce all levels of diarrhea, especially the most severe grade 4 diarrhea. Median abdominal pain was initially 0 for all groups and < 1 during treatment for all groups (P = .23).

To their knowledge, the researchers say, only 6 human clinical studies have been published regarding using probiotics to prevent acute radiation-induced diarrhea, and only 1 for treating diarrhea after radiotherapy. The 6 studies showed positive results on diarrhea toxicity and/or frequency of bowel movement and/or stool consistency. Two of 3 systematic reviews also found a probable beneficial effect on prevention.

Their own study produced some interesting findings, the researchers say. For one, less diarrhea at 60 days meant the benefit began at the end of the treatment or after it. Patients with a standard dose of probiotic experienced less of the moderate-to-severe diarrhea at the end of treatment or during the 2 weeks following treatment. And after 60 days, 35% of patients in the standard-dose group did not have moderate-to-severe diarrhea, compared with 17% in the placebo group (P = .23). The researchers say the probiotic effect may be delayed because of the time required by bacteria to exert their influence on the inflammatory process.

Source

Demers M, Dagnault A, Desjardins J. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(5):761-767.

doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.10.015.

Sugar beets can be used to create hemoglobin

holding a sugar beet

Credit: Lund University

Biochemists have found evidence to suggest that sugar beets can be used to create a substitute for human hemoglobin.

While studying the genome of the sugar beet, the researchers identified 4 hemoglobin genes—3 non-symbiotic genes (BvHb1.1, BvHb1.2, and BvHb2) and 1 truncated gene (BvHb3).

The team then discovered they could extract hemoglobin from sugar beets using a process that’s about as simple as the one used to extract sugar.

The researchers cloned the hemoglobin genes and inserted them into bacteria, which facilitates their expression and purification.

The group described the gene discovery in Plant and Cell Physiology. Study author Nélida Leiva-Eriksson, a doctoral student at Lund University in Sweden, disclosed additional details in her dissertation. And a short video on the research is available on YouTube.

The researchers discovered that the hemoglobin extracted from sugar beets is almost identical to human hemoglobin, especially the form of hemoglobin in the brain.

“There is a difference in a small detail on the surface of the protein, but this simply appears to extend the lifespan of the hemoglobin from sugar beet, which is good news,” Leiva-Eriksson said.

On the other hand, sugar beet hemoglobin has a completely different function from human hemoglobin.

“We have found that the hemoglobin in the plant binds nitric oxide,” Leiva-Eriksson said. “It is probably needed to keep certain processes in check, for example, so that the nitric oxide doesn’t become toxic, and to ward off bacteria.”

The researchers are planning to start testing the sugar beet hemoglobin in animal experiments in just over a year.

The team said there is good reason to think hemoglobin derived from sugar beets and other crops could become a realistic alternative to human hemoglobin.

“From 1 hectare, we could produce 1 to 2 tons of hemoglobin,” said Leif Bülow, PhD, of Lund University, “which could save thousands of lives.” ![]()

holding a sugar beet

Credit: Lund University

Biochemists have found evidence to suggest that sugar beets can be used to create a substitute for human hemoglobin.

While studying the genome of the sugar beet, the researchers identified 4 hemoglobin genes—3 non-symbiotic genes (BvHb1.1, BvHb1.2, and BvHb2) and 1 truncated gene (BvHb3).

The team then discovered they could extract hemoglobin from sugar beets using a process that’s about as simple as the one used to extract sugar.

The researchers cloned the hemoglobin genes and inserted them into bacteria, which facilitates their expression and purification.

The group described the gene discovery in Plant and Cell Physiology. Study author Nélida Leiva-Eriksson, a doctoral student at Lund University in Sweden, disclosed additional details in her dissertation. And a short video on the research is available on YouTube.

The researchers discovered that the hemoglobin extracted from sugar beets is almost identical to human hemoglobin, especially the form of hemoglobin in the brain.

“There is a difference in a small detail on the surface of the protein, but this simply appears to extend the lifespan of the hemoglobin from sugar beet, which is good news,” Leiva-Eriksson said.

On the other hand, sugar beet hemoglobin has a completely different function from human hemoglobin.

“We have found that the hemoglobin in the plant binds nitric oxide,” Leiva-Eriksson said. “It is probably needed to keep certain processes in check, for example, so that the nitric oxide doesn’t become toxic, and to ward off bacteria.”

The researchers are planning to start testing the sugar beet hemoglobin in animal experiments in just over a year.

The team said there is good reason to think hemoglobin derived from sugar beets and other crops could become a realistic alternative to human hemoglobin.

“From 1 hectare, we could produce 1 to 2 tons of hemoglobin,” said Leif Bülow, PhD, of Lund University, “which could save thousands of lives.” ![]()

holding a sugar beet

Credit: Lund University

Biochemists have found evidence to suggest that sugar beets can be used to create a substitute for human hemoglobin.

While studying the genome of the sugar beet, the researchers identified 4 hemoglobin genes—3 non-symbiotic genes (BvHb1.1, BvHb1.2, and BvHb2) and 1 truncated gene (BvHb3).

The team then discovered they could extract hemoglobin from sugar beets using a process that’s about as simple as the one used to extract sugar.

The researchers cloned the hemoglobin genes and inserted them into bacteria, which facilitates their expression and purification.

The group described the gene discovery in Plant and Cell Physiology. Study author Nélida Leiva-Eriksson, a doctoral student at Lund University in Sweden, disclosed additional details in her dissertation. And a short video on the research is available on YouTube.

The researchers discovered that the hemoglobin extracted from sugar beets is almost identical to human hemoglobin, especially the form of hemoglobin in the brain.

“There is a difference in a small detail on the surface of the protein, but this simply appears to extend the lifespan of the hemoglobin from sugar beet, which is good news,” Leiva-Eriksson said.

On the other hand, sugar beet hemoglobin has a completely different function from human hemoglobin.

“We have found that the hemoglobin in the plant binds nitric oxide,” Leiva-Eriksson said. “It is probably needed to keep certain processes in check, for example, so that the nitric oxide doesn’t become toxic, and to ward off bacteria.”

The researchers are planning to start testing the sugar beet hemoglobin in animal experiments in just over a year.

The team said there is good reason to think hemoglobin derived from sugar beets and other crops could become a realistic alternative to human hemoglobin.

“From 1 hectare, we could produce 1 to 2 tons of hemoglobin,” said Leif Bülow, PhD, of Lund University, “which could save thousands of lives.” ![]()

Team pinpoints new target for MM therapy

Researchers say they’ve identified a promising therapeutic target for multiple myeloma (MM).

The group first discovered that MM patients have higher expression of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2), a member of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family, compared to healthy individuals.

Then, preclinical experiments revealed that PYK2 plays a role in tumor progression, and inhibiting this kinase can impede MM cell growth.

Yu Zhang, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Comparing samples from MM patients and healthy controls, the researchers found that PYK2 is highly expressed in MM. The team even detected higher levels of PYK2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance and smoldering myeloma.

Additional experiments helped the group elucidate PYK2’s role in MM, showing that the kinase promotes tumor progression by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

When the researchers inhibited PYK2, they observed a reduction in MM tumor growth in vivo as well as decreased cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and adhesion ability in vitro.

In contrast, overexpression of PYK2 promoted the malignant phenotype, as evidenced by enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival in mouse models.

Finally, the researchers showed that a FAK/PYK2 inhibitor, VS-4718, inhibited MM cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.

“In addition to this work recently published by our collaborators at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we have been conducting further research and collaborating with scientific leaders to understand the potential of cancer stem cell inhibitors in hematological malignancies,” said Jonathan Pachter, PhD, head of research at Verastem, Inc., the company developing VS-4781.

“We believe that inhibitors of FAK and PYK2, such as VS-4718, may be useful in the treatment of many types of cancer, particularly where there is minimal residual disease with enrichment of cancer stem cells following chemotherapy. We and our collaborators will be presenting additional research at the upcoming American Society of Hematology in December.”

VS-4718 is being evaluated in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial in patients with advanced solid tumors. Another phase 1 trial in hematological malignancies is set to begin in the first quarter of 2015. ![]()

Researchers say they’ve identified a promising therapeutic target for multiple myeloma (MM).

The group first discovered that MM patients have higher expression of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2), a member of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family, compared to healthy individuals.

Then, preclinical experiments revealed that PYK2 plays a role in tumor progression, and inhibiting this kinase can impede MM cell growth.

Yu Zhang, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Comparing samples from MM patients and healthy controls, the researchers found that PYK2 is highly expressed in MM. The team even detected higher levels of PYK2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance and smoldering myeloma.

Additional experiments helped the group elucidate PYK2’s role in MM, showing that the kinase promotes tumor progression by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

When the researchers inhibited PYK2, they observed a reduction in MM tumor growth in vivo as well as decreased cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and adhesion ability in vitro.

In contrast, overexpression of PYK2 promoted the malignant phenotype, as evidenced by enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival in mouse models.

Finally, the researchers showed that a FAK/PYK2 inhibitor, VS-4718, inhibited MM cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.

“In addition to this work recently published by our collaborators at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we have been conducting further research and collaborating with scientific leaders to understand the potential of cancer stem cell inhibitors in hematological malignancies,” said Jonathan Pachter, PhD, head of research at Verastem, Inc., the company developing VS-4781.

“We believe that inhibitors of FAK and PYK2, such as VS-4718, may be useful in the treatment of many types of cancer, particularly where there is minimal residual disease with enrichment of cancer stem cells following chemotherapy. We and our collaborators will be presenting additional research at the upcoming American Society of Hematology in December.”

VS-4718 is being evaluated in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial in patients with advanced solid tumors. Another phase 1 trial in hematological malignancies is set to begin in the first quarter of 2015. ![]()

Researchers say they’ve identified a promising therapeutic target for multiple myeloma (MM).

The group first discovered that MM patients have higher expression of proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2), a member of the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) family, compared to healthy individuals.

Then, preclinical experiments revealed that PYK2 plays a role in tumor progression, and inhibiting this kinase can impede MM cell growth.

Yu Zhang, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and colleagues reported these findings in Blood.

Comparing samples from MM patients and healthy controls, the researchers found that PYK2 is highly expressed in MM. The team even detected higher levels of PYK2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance and smoldering myeloma.

Additional experiments helped the group elucidate PYK2’s role in MM, showing that the kinase promotes tumor progression by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

When the researchers inhibited PYK2, they observed a reduction in MM tumor growth in vivo as well as decreased cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, and adhesion ability in vitro.

In contrast, overexpression of PYK2 promoted the malignant phenotype, as evidenced by enhanced tumor growth and reduced survival in mouse models.

Finally, the researchers showed that a FAK/PYK2 inhibitor, VS-4718, inhibited MM cell growth both in vitro and in vivo.

“In addition to this work recently published by our collaborators at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we have been conducting further research and collaborating with scientific leaders to understand the potential of cancer stem cell inhibitors in hematological malignancies,” said Jonathan Pachter, PhD, head of research at Verastem, Inc., the company developing VS-4781.

“We believe that inhibitors of FAK and PYK2, such as VS-4718, may be useful in the treatment of many types of cancer, particularly where there is minimal residual disease with enrichment of cancer stem cells following chemotherapy. We and our collaborators will be presenting additional research at the upcoming American Society of Hematology in December.”

VS-4718 is being evaluated in a phase 1 dose-escalation trial in patients with advanced solid tumors. Another phase 1 trial in hematological malignancies is set to begin in the first quarter of 2015. ![]()

Hematology drugs on the fast track

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to two hematology drugs: the monoclonal antibody MOR208 to treat relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and the antifibrotic agent PRM-151 to treat myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA’s fast track program aims to expedite the development and review of drugs that have the potential to fill an unmet medical need in serious or life-threatening conditions.

MOR208

MOR208 is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD19. It is under development by MorphoSys AG to treat B-cell malignancies. The program is in phase 2 clinical development in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Preclinical research with MOR208 revealed that it can trigger natural killer cell-mediated lysis of ALL cells. The drug had lytic activity against ALL cells from both adult and pediatric patients.

In a phase 1 study, MOR208 exhibited preliminary efficacy in patients with high-risk, heavily pretreated CLL, prompting responses in 67% of patients. Researchers said toxicity was acceptable, but infusion reactions were common.

“First results of our ongoing phase 2 trial, which we will present at this year’s ASH conference in December, have helped to identify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as a valuable development opportunity for MOR208,” said Arndt Schottelius, chief development officer of MorphoSys AG.

“We are therefore delighted to have received the fast track designation for further development of MOR208 in DLBCL. The more frequent interactions with the FDA that this enables will help us to expedite the development of MOR208 in this particular subset of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients.”

PRM-151

PRM-151 is a recombinant form of an endogenous human protein, pentraxin-2, that is specifically active at the site of tissue damage. PRM-151 is an agonist that acts as a monocyte/macrophage differentiation factor to prevent and potentially reverse fibrosis.

The drug has shown broad anti-fibrotic activity in preclinical models of fibrotic disease, including pulmonary fibrosis, acute and chronic nephropathy, liver fibrosis, and age-related macular degeneration.

PRM-151 has orphan designation in the US for MF and in both the US and European Union for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The FDA’s fast track designation for PRM-151 covers primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

“This designation validates our perspective that there is a clear and compelling need for a novel mechanism for the treatment of myelofibrosis that specifically targets the underlying fibrotic processes of the disease,” said Beth Tréhu, MD, FACP, chief medical officer of Promedior Inc., the company developing PRM-151.

“We will continue to work expeditiously to advance this program through the clinic and look forward to presenting the full data set from the first stage of our phase 2 study later this year.”

Preliminary data from the phase 2 study of PRM-151 demonstrated benefits across all clinically relevant measures of MF, including decreases in bone marrow fibrosis, symptom responses, improvements in hemoglobin and platelets, and reductions in spleen size.

The drug also appeared to be well-tolerated and did not prompt myelosuppression. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to two hematology drugs: the monoclonal antibody MOR208 to treat relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and the antifibrotic agent PRM-151 to treat myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA’s fast track program aims to expedite the development and review of drugs that have the potential to fill an unmet medical need in serious or life-threatening conditions.

MOR208

MOR208 is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD19. It is under development by MorphoSys AG to treat B-cell malignancies. The program is in phase 2 clinical development in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Preclinical research with MOR208 revealed that it can trigger natural killer cell-mediated lysis of ALL cells. The drug had lytic activity against ALL cells from both adult and pediatric patients.

In a phase 1 study, MOR208 exhibited preliminary efficacy in patients with high-risk, heavily pretreated CLL, prompting responses in 67% of patients. Researchers said toxicity was acceptable, but infusion reactions were common.

“First results of our ongoing phase 2 trial, which we will present at this year’s ASH conference in December, have helped to identify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as a valuable development opportunity for MOR208,” said Arndt Schottelius, chief development officer of MorphoSys AG.

“We are therefore delighted to have received the fast track designation for further development of MOR208 in DLBCL. The more frequent interactions with the FDA that this enables will help us to expedite the development of MOR208 in this particular subset of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients.”

PRM-151

PRM-151 is a recombinant form of an endogenous human protein, pentraxin-2, that is specifically active at the site of tissue damage. PRM-151 is an agonist that acts as a monocyte/macrophage differentiation factor to prevent and potentially reverse fibrosis.

The drug has shown broad anti-fibrotic activity in preclinical models of fibrotic disease, including pulmonary fibrosis, acute and chronic nephropathy, liver fibrosis, and age-related macular degeneration.

PRM-151 has orphan designation in the US for MF and in both the US and European Union for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The FDA’s fast track designation for PRM-151 covers primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

“This designation validates our perspective that there is a clear and compelling need for a novel mechanism for the treatment of myelofibrosis that specifically targets the underlying fibrotic processes of the disease,” said Beth Tréhu, MD, FACP, chief medical officer of Promedior Inc., the company developing PRM-151.

“We will continue to work expeditiously to advance this program through the clinic and look forward to presenting the full data set from the first stage of our phase 2 study later this year.”

Preliminary data from the phase 2 study of PRM-151 demonstrated benefits across all clinically relevant measures of MF, including decreases in bone marrow fibrosis, symptom responses, improvements in hemoglobin and platelets, and reductions in spleen size.

The drug also appeared to be well-tolerated and did not prompt myelosuppression. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to two hematology drugs: the monoclonal antibody MOR208 to treat relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and the antifibrotic agent PRM-151 to treat myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA’s fast track program aims to expedite the development and review of drugs that have the potential to fill an unmet medical need in serious or life-threatening conditions.

MOR208

MOR208 is a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD19. It is under development by MorphoSys AG to treat B-cell malignancies. The program is in phase 2 clinical development in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Preclinical research with MOR208 revealed that it can trigger natural killer cell-mediated lysis of ALL cells. The drug had lytic activity against ALL cells from both adult and pediatric patients.

In a phase 1 study, MOR208 exhibited preliminary efficacy in patients with high-risk, heavily pretreated CLL, prompting responses in 67% of patients. Researchers said toxicity was acceptable, but infusion reactions were common.

“First results of our ongoing phase 2 trial, which we will present at this year’s ASH conference in December, have helped to identify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma as a valuable development opportunity for MOR208,” said Arndt Schottelius, chief development officer of MorphoSys AG.

“We are therefore delighted to have received the fast track designation for further development of MOR208 in DLBCL. The more frequent interactions with the FDA that this enables will help us to expedite the development of MOR208 in this particular subset of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients.”

PRM-151

PRM-151 is a recombinant form of an endogenous human protein, pentraxin-2, that is specifically active at the site of tissue damage. PRM-151 is an agonist that acts as a monocyte/macrophage differentiation factor to prevent and potentially reverse fibrosis.

The drug has shown broad anti-fibrotic activity in preclinical models of fibrotic disease, including pulmonary fibrosis, acute and chronic nephropathy, liver fibrosis, and age-related macular degeneration.

PRM-151 has orphan designation in the US for MF and in both the US and European Union for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

The FDA’s fast track designation for PRM-151 covers primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF.

“This designation validates our perspective that there is a clear and compelling need for a novel mechanism for the treatment of myelofibrosis that specifically targets the underlying fibrotic processes of the disease,” said Beth Tréhu, MD, FACP, chief medical officer of Promedior Inc., the company developing PRM-151.

“We will continue to work expeditiously to advance this program through the clinic and look forward to presenting the full data set from the first stage of our phase 2 study later this year.”

Preliminary data from the phase 2 study of PRM-151 demonstrated benefits across all clinically relevant measures of MF, including decreases in bone marrow fibrosis, symptom responses, improvements in hemoglobin and platelets, and reductions in spleen size.

The drug also appeared to be well-tolerated and did not prompt myelosuppression. ![]()

Artificial platelets halt bleeding faster

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Artificial platelet mimics can halt bleeding in mouse models 65% faster than nature can on its own, a new study has shown.

These platelet-like nanoparticles (PLNs) mimic the shape, size, flexibility, and surface chemistry of real blood platelets.

Researchers believe these design factors together are important for inducing clots to form faster at vascular injury sites while preventing harmful clots from forming indiscriminately elsewhere in the body.

The new technology is reported in ACS Nano.

Study investigator Anirban Sen Gupta, PhD, of Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, Ohio, previously designed peptide-based surface chemistries that mimic the clot-relevant activities of real platelets.

Building on this work, Dr Sen Gupta has now focused on incorporating morphological and mechanical cues that are naturally present in platelets to further refine the design.

“Morphological and mechanical factors influence the margination of natural platelets to the blood vessel wall, and only when they are near the wall can the critical clot-promoting chemical interactions take place,” he said.

These natural cues motivated Dr Sen Gupta to team up with Samir Mitragotri, PhD, of the University of California Santa Barbara, whose lab recently developed albumin-based technologies to make particles that mimic the geometry and mechanical properties of red blood cells and platelets.

Together, the researchers developed PLNs that combine morphological, mechanical, and surface chemical properties of natural platelets.

The team believes this refined design will be able to simulate natural platelet’s ability to collide effectively with larger and softer red blood cells in systemic blood flow. The collisions cause margination—pushing the platelets out of the main flow and closer to the blood vessel wall—increasing the probability of interacting with an injury site.

The surface coatings enable the PLNs to anchor to injury-site-specific proteins, von Willebrand factor and collagen, while inducing the natural and artificial platelets to aggregate faster at the injury site.

When the researchers injected the PLNs in mice, the artificial platelets formed clots at the site of injury 3 times faster than natural platelets alone in control mice.

The ability to interact selectively with injury site proteins, as well as the ability to remain mechanically flexible like natural platelets, enables these PLNs to safely ride through the smallest of blood vessels without causing unwanted clots. PLNs that don’t aggregate in a clot and continue to circulate are metabolized in 1 to 2 days.

The researchers believe their new artificial platelet design may be even more effective in larger-volume blood flows, where margination to the blood vessel wall is more prominent. They expect to soon begin testing those capabilities.

If the PLNs prove effective in humans, they could be used to stem bleeding in patients with clotting disorders, those suffering from traumatic injury, and patients undergoing surgeries.

The technology might also be used to deliver drugs to target sites in patients suffering from atherosclerosis, thrombosis, or other platelet-involved pathologic conditions. Dr Sen Gupta believes the PLNs could even be used to deliver cancer drugs to metastatic tumors that have high platelet interactions. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Artificial platelet mimics can halt bleeding in mouse models 65% faster than nature can on its own, a new study has shown.

These platelet-like nanoparticles (PLNs) mimic the shape, size, flexibility, and surface chemistry of real blood platelets.

Researchers believe these design factors together are important for inducing clots to form faster at vascular injury sites while preventing harmful clots from forming indiscriminately elsewhere in the body.

The new technology is reported in ACS Nano.

Study investigator Anirban Sen Gupta, PhD, of Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, Ohio, previously designed peptide-based surface chemistries that mimic the clot-relevant activities of real platelets.

Building on this work, Dr Sen Gupta has now focused on incorporating morphological and mechanical cues that are naturally present in platelets to further refine the design.

“Morphological and mechanical factors influence the margination of natural platelets to the blood vessel wall, and only when they are near the wall can the critical clot-promoting chemical interactions take place,” he said.

These natural cues motivated Dr Sen Gupta to team up with Samir Mitragotri, PhD, of the University of California Santa Barbara, whose lab recently developed albumin-based technologies to make particles that mimic the geometry and mechanical properties of red blood cells and platelets.

Together, the researchers developed PLNs that combine morphological, mechanical, and surface chemical properties of natural platelets.

The team believes this refined design will be able to simulate natural platelet’s ability to collide effectively with larger and softer red blood cells in systemic blood flow. The collisions cause margination—pushing the platelets out of the main flow and closer to the blood vessel wall—increasing the probability of interacting with an injury site.

The surface coatings enable the PLNs to anchor to injury-site-specific proteins, von Willebrand factor and collagen, while inducing the natural and artificial platelets to aggregate faster at the injury site.

When the researchers injected the PLNs in mice, the artificial platelets formed clots at the site of injury 3 times faster than natural platelets alone in control mice.

The ability to interact selectively with injury site proteins, as well as the ability to remain mechanically flexible like natural platelets, enables these PLNs to safely ride through the smallest of blood vessels without causing unwanted clots. PLNs that don’t aggregate in a clot and continue to circulate are metabolized in 1 to 2 days.

The researchers believe their new artificial platelet design may be even more effective in larger-volume blood flows, where margination to the blood vessel wall is more prominent. They expect to soon begin testing those capabilities.

If the PLNs prove effective in humans, they could be used to stem bleeding in patients with clotting disorders, those suffering from traumatic injury, and patients undergoing surgeries.

The technology might also be used to deliver drugs to target sites in patients suffering from atherosclerosis, thrombosis, or other platelet-involved pathologic conditions. Dr Sen Gupta believes the PLNs could even be used to deliver cancer drugs to metastatic tumors that have high platelet interactions. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

Artificial platelet mimics can halt bleeding in mouse models 65% faster than nature can on its own, a new study has shown.

These platelet-like nanoparticles (PLNs) mimic the shape, size, flexibility, and surface chemistry of real blood platelets.

Researchers believe these design factors together are important for inducing clots to form faster at vascular injury sites while preventing harmful clots from forming indiscriminately elsewhere in the body.

The new technology is reported in ACS Nano.

Study investigator Anirban Sen Gupta, PhD, of Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, Ohio, previously designed peptide-based surface chemistries that mimic the clot-relevant activities of real platelets.

Building on this work, Dr Sen Gupta has now focused on incorporating morphological and mechanical cues that are naturally present in platelets to further refine the design.

“Morphological and mechanical factors influence the margination of natural platelets to the blood vessel wall, and only when they are near the wall can the critical clot-promoting chemical interactions take place,” he said.

These natural cues motivated Dr Sen Gupta to team up with Samir Mitragotri, PhD, of the University of California Santa Barbara, whose lab recently developed albumin-based technologies to make particles that mimic the geometry and mechanical properties of red blood cells and platelets.

Together, the researchers developed PLNs that combine morphological, mechanical, and surface chemical properties of natural platelets.

The team believes this refined design will be able to simulate natural platelet’s ability to collide effectively with larger and softer red blood cells in systemic blood flow. The collisions cause margination—pushing the platelets out of the main flow and closer to the blood vessel wall—increasing the probability of interacting with an injury site.

The surface coatings enable the PLNs to anchor to injury-site-specific proteins, von Willebrand factor and collagen, while inducing the natural and artificial platelets to aggregate faster at the injury site.

When the researchers injected the PLNs in mice, the artificial platelets formed clots at the site of injury 3 times faster than natural platelets alone in control mice.

The ability to interact selectively with injury site proteins, as well as the ability to remain mechanically flexible like natural platelets, enables these PLNs to safely ride through the smallest of blood vessels without causing unwanted clots. PLNs that don’t aggregate in a clot and continue to circulate are metabolized in 1 to 2 days.

The researchers believe their new artificial platelet design may be even more effective in larger-volume blood flows, where margination to the blood vessel wall is more prominent. They expect to soon begin testing those capabilities.

If the PLNs prove effective in humans, they could be used to stem bleeding in patients with clotting disorders, those suffering from traumatic injury, and patients undergoing surgeries.

The technology might also be used to deliver drugs to target sites in patients suffering from atherosclerosis, thrombosis, or other platelet-involved pathologic conditions. Dr Sen Gupta believes the PLNs could even be used to deliver cancer drugs to metastatic tumors that have high platelet interactions. ![]()

Endometrial cancer