User login

Clomiphene better than letrozole to treat women with unexplained infertility

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

When the cause of infertility is unexplained, what is the best first-choice treatment option? Could letrozole, an oral nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, result in fewer multiple gestations than current standard therapy—gonadotropins or selective estrogen receptor modulators (clomiphene citrate)—without worsening the live birth rate?

Researchers from the Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS) trial investigated this question and presented data at the recent annual meeting of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Study details

This prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical trial involved 900 women aged 18 to 40 with at least one patent fallopian tube and regular menses. Patients underwent ovarian stimulation for up to four cycles with an injectable gonadotropin (Gn; n = 300), clomiphene citrate (n = 301), or letrozole (n = 299), followed by intrauterine insemination (IUI).

Birth rate. Conception occurred in 46.8%, 35.7%, and 28.4% of women receiving Gn, clomiphene, and letrozole, respectively, with a live birth occurring in 32.2%, 23.3%, and 18.7% of respective cases. Pregnancy rates with letrozole were significantly less than with Gn (P<.001) and less than with clomiphene (P<.015).

Multiple gestations. The rate of multiple gestations was highest among women treated with Gn (10.3%). But the multiple gestation rate for letrozole was higher than that for clomiphene (2.7% vs 1.3%, respectively). All multiples treated with letrozole and clomiphene were twins; in the Gn group, there were 24 twin and 10 triplet gestations.

No significant difference was found in the rates of infants with congenital anomalies or other fetal or neonatal complications.1

Clomiphene plus IUI remains first-line therapy for unexplained infertility

Although ovarian stimulation with letrozole was safe overall, the number of live births was reduced when treatment with letrozole was compared with clomiphene or Gn, and the multiple pregnancy rate for letrozole fell between clomiphene and Gn.

“CC [clomiphene citrate] /IUI remains first-line therapy for women with unexplained infertility,” concludes Michael P. Diamond, Chair and Professor of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, Georgia.

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

Reference

Diamond MP. Outcomes of the NICHD’s comparative effectiveness assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. The NICHD cooperative reproductive medicine network. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(3):e39. http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2814%2900767-5/fulltext. Accessed October 31, 2014.

Bob Wachter Says Cost Equation Is Shifting in Ever-Changing Healthcare Paradigm

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

HM pioneer says hospitalists who have flown under radar soon will be counted on to produce cost, waste reduction.

Hospitalists Flock to Annual Meeting's Bedside Procedures Pre-Courses

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

From early-career hospitalists looking to gain hands-on experience with intraosseous lines to family-medicine trained physicians brushing up on ultrasound usage, the procedures' pre-courses at SHM annual meetings receive rave reviews.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

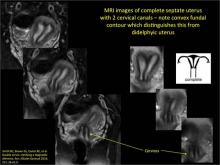

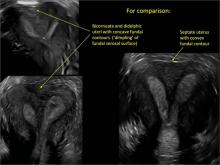

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification

A classification of the Müllerian anomalies was introduced in 1980 and, with few modifications, was adopted by the American Fertility Society (currently, ASRM). The Society identified seven basic groups according to Müllerian development and their relationship to fertility: agenesis and hypoplasias, unicornuate uteri (unilateral hypoplasia), didelphys uteri (complete nonfusion), bicornuate uteri (incomplete fusion), septate uteri (nonreabsorption of septum), arcuate uteri (almost complete reabsorption of septum), and anomalies related to fetal DES exposure.2

Anomalies also can be categorized in terms of progression along the developmental continuum, taking into account that many cases result from partial failure of fusion and reabsorption: agenesis (Types I and II), lack of fusion (Types III and IV), lack of reabsorption(Types V and VI), and lack of posterior development (Type VII) (FIGURE 1).3

| FIGURE 1. Classification of müllerian anomalies |

|---|

|

| Source: The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988. 49(6):944-955. |

3D ultrasonography offers accurate, cost-efficient diagnosis

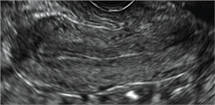

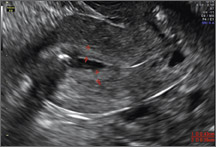

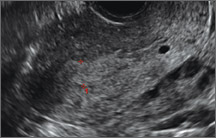

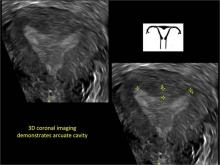

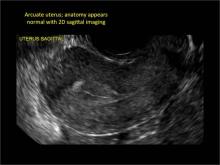

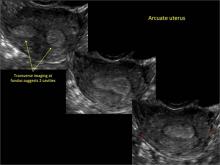

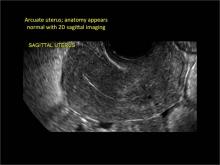

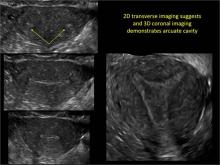

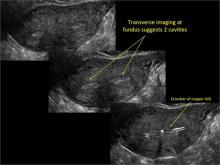

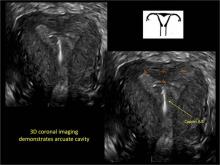

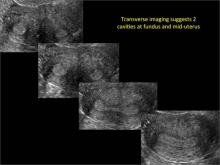

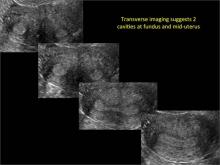

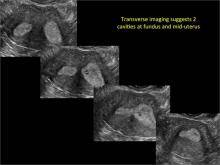

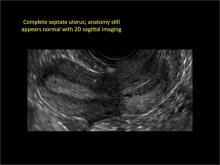

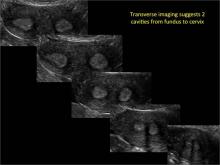

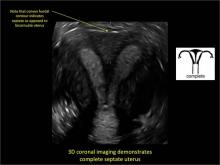

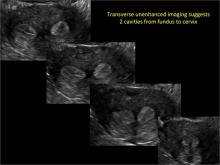

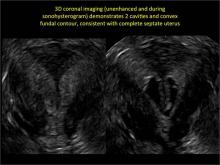

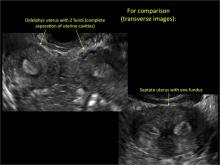

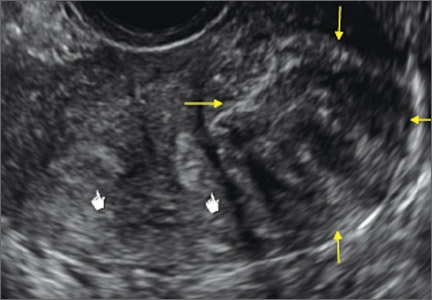

Using only 2D imaging, neither an unenhanced sonogram nor a sonohysterogram can provide definitive information regarding the possibility of a uterine anomaly. The fundal contour cannot be evaluated with 2D imaging; likewise, details regarding the configuration of the uterine cavity (or cavities) may not be appreciated with the use of 2D imaging (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2: Normal appearance, but abnormal uteri

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. 2D sagittal views of a normal uterus (top), a didelphic uterus (middle), and a sonohysterogram of a septate uterus (bottom). |

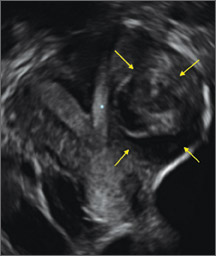

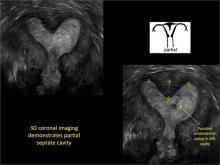

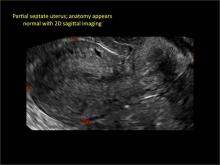

To fully evaluate the uterine fundal contour and determine the type of uterine anomaly, it previously was necessary to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or perform laparoscopy. Today, however, 3D coronal ultrasonography (US) can allow for accurate evaluation of fundal contour and diagnosis of uterine anomalies with lower cost and greater patient convenience. Several studies have confirmed the high accuracy of 3D US compared with MRI and surgical findings in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies (with 3D US showing 98% to 100% sensitivity and specificity).4-6

Case: Partial septate uterus

|

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):593–601.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(6):944–955.

- Acien P, Acien M. Updated classification of malformations. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(suppl 1):i81–i82.

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, Stadtmauer L, Abuhamad AZ. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of Müllerian anomalies [abstract P-465]. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(suppl):S308.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital Müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(9):487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification

A classification of the Müllerian anomalies was introduced in 1980 and, with few modifications, was adopted by the American Fertility Society (currently, ASRM). The Society identified seven basic groups according to Müllerian development and their relationship to fertility: agenesis and hypoplasias, unicornuate uteri (unilateral hypoplasia), didelphys uteri (complete nonfusion), bicornuate uteri (incomplete fusion), septate uteri (nonreabsorption of septum), arcuate uteri (almost complete reabsorption of septum), and anomalies related to fetal DES exposure.2

Anomalies also can be categorized in terms of progression along the developmental continuum, taking into account that many cases result from partial failure of fusion and reabsorption: agenesis (Types I and II), lack of fusion (Types III and IV), lack of reabsorption(Types V and VI), and lack of posterior development (Type VII) (FIGURE 1).3

| FIGURE 1. Classification of müllerian anomalies |

|---|

|

| Source: The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988. 49(6):944-955. |

3D ultrasonography offers accurate, cost-efficient diagnosis

Using only 2D imaging, neither an unenhanced sonogram nor a sonohysterogram can provide definitive information regarding the possibility of a uterine anomaly. The fundal contour cannot be evaluated with 2D imaging; likewise, details regarding the configuration of the uterine cavity (or cavities) may not be appreciated with the use of 2D imaging (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2: Normal appearance, but abnormal uteri

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. 2D sagittal views of a normal uterus (top), a didelphic uterus (middle), and a sonohysterogram of a septate uterus (bottom). |

To fully evaluate the uterine fundal contour and determine the type of uterine anomaly, it previously was necessary to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or perform laparoscopy. Today, however, 3D coronal ultrasonography (US) can allow for accurate evaluation of fundal contour and diagnosis of uterine anomalies with lower cost and greater patient convenience. Several studies have confirmed the high accuracy of 3D US compared with MRI and surgical findings in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies (with 3D US showing 98% to 100% sensitivity and specificity).4-6

Case: Partial septate uterus

|

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification

A classification of the Müllerian anomalies was introduced in 1980 and, with few modifications, was adopted by the American Fertility Society (currently, ASRM). The Society identified seven basic groups according to Müllerian development and their relationship to fertility: agenesis and hypoplasias, unicornuate uteri (unilateral hypoplasia), didelphys uteri (complete nonfusion), bicornuate uteri (incomplete fusion), septate uteri (nonreabsorption of septum), arcuate uteri (almost complete reabsorption of septum), and anomalies related to fetal DES exposure.2

Anomalies also can be categorized in terms of progression along the developmental continuum, taking into account that many cases result from partial failure of fusion and reabsorption: agenesis (Types I and II), lack of fusion (Types III and IV), lack of reabsorption(Types V and VI), and lack of posterior development (Type VII) (FIGURE 1).3

| FIGURE 1. Classification of müllerian anomalies |

|---|

|

| Source: The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988. 49(6):944-955. |

3D ultrasonography offers accurate, cost-efficient diagnosis

Using only 2D imaging, neither an unenhanced sonogram nor a sonohysterogram can provide definitive information regarding the possibility of a uterine anomaly. The fundal contour cannot be evaluated with 2D imaging; likewise, details regarding the configuration of the uterine cavity (or cavities) may not be appreciated with the use of 2D imaging (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2: Normal appearance, but abnormal uteri

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. 2D sagittal views of a normal uterus (top), a didelphic uterus (middle), and a sonohysterogram of a septate uterus (bottom). |

To fully evaluate the uterine fundal contour and determine the type of uterine anomaly, it previously was necessary to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or perform laparoscopy. Today, however, 3D coronal ultrasonography (US) can allow for accurate evaluation of fundal contour and diagnosis of uterine anomalies with lower cost and greater patient convenience. Several studies have confirmed the high accuracy of 3D US compared with MRI and surgical findings in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies (with 3D US showing 98% to 100% sensitivity and specificity).4-6

Case: Partial septate uterus

|

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):593–601.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(6):944–955.

- Acien P, Acien M. Updated classification of malformations. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(suppl 1):i81–i82.

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, Stadtmauer L, Abuhamad AZ. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of Müllerian anomalies [abstract P-465]. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(suppl):S308.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital Müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(9):487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):593–601.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(6):944–955.

- Acien P, Acien M. Updated classification of malformations. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(suppl 1):i81–i82.

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, Stadtmauer L, Abuhamad AZ. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of Müllerian anomalies [abstract P-465]. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(suppl):S308.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital Müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(9):487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

Hair Loss in a 12-Year-Old

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

A mother brings her 12-year-old son to dermatology following a referral from the boy’s pediatrician. Several months ago, she noticed her son’s hair loss. The change had been preceded by a stressful period in which she and her husband divorced and one of the boy’s grandparents died unexpectedly.

Both the mother and other relatives and friends had observed the boy reaching for his scalp frequently and twirling his hair “absentmindedly.” When asked if the area in question bothers him, the boy always answers in the negative. Although he knows he should leave his scalp and hair alone, he says he finds it difficult to do so—even though he acknowledges the social liability of his hair loss. According to the mother, the more his family discourages his behavior, the more it persists.

EXAMINATION

Distinct but incomplete hair loss is noted in an 8 x 10–cm area of his scalp crown. There is neither redness nor any disturbance to the skin there. On palpation, there is no tenderness or increased warmth. No nodes are felt in the adjacent head or neck. Hair pull test is negative.

Closer examination shows hairs of varying lengths in the affected area: many quite short, others of normal length, and many of intermediate length.

Blood work done by the referring pediatrician—including complete blood count, chemistry panel, antinuclear antibody test, and thyroid testing—yielded no abnormal results.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Hair loss, collectively termed alopecia, is a disturbing development, especially in a child. In this case, we had localized hair loss most likely caused by behavior that was not only witnessed by the boy’s parents but also admitted to by the patient. (We’re not always so fortunate.) Thus, it was fairly straightforward to diagnosis trichotillomania, also known as trichotillosis or hair-pulling disorder. This condition can mimic alopecia areata and tinea capitis.

In this case, the lack of epidermal change (scaling, redness, edema) and palpable adenopathy spoke loudly against fungal infection. The hair loss in alopecia areata (AA) is usually sharply defined and complete, which our patient’s hair loss was not. And the blood work that was done effectively ruled out systemic disease (an unlikely cause of localized hair loss in any case).

The jury is still out as to how exactly to classify trichotillomania (TTM). The new DSM-V lists it as an anxiety disorder, in part because it often appears in that context. What we do know is that girls are twice as likely as boys to be affected. And children ages 4 to 13 are seven times more likely than adults to develop TTM.

TTM can involve hair anywhere on the body, though children almost always confine their behavior to their scalp. Actual hair-pulling is not necessarily seen. Manipulation, such as the twirling in this case, is enough to weaken hair follicles, causing hair to fall out. In cases involving hair-pulling, a small percentage of patients actually ingest the hairs they’ve plucked out (trichophagia). Being indigestible, the hairs can accumulate in hairballs (trichobezoars).

Even though TTM is most likely a psychiatric disorder lying somewhere in the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, it is seen more often in primary care and dermatology offices. Scalp biopsy would certainly settle the matter, but a better alternative is simply shaving a dime-sized area of scalp and watching it for normal hair growth.

Most cases eventually resolve with time and persistent but gentle reminders, but a few will require psychiatric intervention. This typically includes habit reversal therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, plus or minus combinations of psychoactive medications. (The latter decision depends on whether there psychiatric comorbidities.) Despite all these efforts, severe cases of TTM can persist for years or even a lifetime.

It remains to be seen how this particular patient responds to his parents’ efforts. It was an immense relief for them to know the cause of their son’s hair loss and that the condition is likely self-limiting.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Trichotillomania (TTM) is an unusual form of localized hair loss, usually involving children’s scalps.

• TTM affects children ages 4 to 13 and at least twice as many girls as boys.

• TTM does not always involve actual plucking of hairs. Repetitive manipulation, such as twirling, can weaken the hairs enough to cause hair loss.

• Unlike alopecia areata (the main item in the alopecia differential for children), TTM is more likely to cause incomplete, poorly defined hair loss in an area where hairs of varying length can be seen.

• Usually self-limiting, TTM can require psychiatric attention, for which a variety of habit training techniques can be used.

FDA lifts clinical hold on imetelstat

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed the full clinical hold placed on the investigational new drug application for the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat.

The hold, which was placed in March, suspended a phase 2 study of imetelstat in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) or polycythemia vera (PV), as well as a phase 2 study of the drug in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The hold also delayed a planned phase 2 trial in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

And it temporarily suspended an investigator-sponsored trial of imetelstat in MF. The FDA lifted the hold on the investigator-sponsored trial in June.

The FDA halted these trials due to reports of persistent, low-grade liver function test (LFT) abnormalities observed in the phase 2 study of ET/PV patients and the potential risk of chronic liver injury following long-term exposure to imetelstat. The FDA expressed concern about whether these LFT abnormalities are reversible.

Now, data provided by the Geron Corporation, the company developing imetelstat, has convinced the FDA to lift the hold on all trials.

The FDA said the proposed clinical development plan for imetelstat, which is focused on high-risk myeloid disorders such as MF, is acceptable. Geron Corporation has said it does not intend to conduct further studies with, or develop imetelstat for, patients with ET or PV.

To address the clinical hold, the FDA required Geron to provide follow-up information from imetelstat-treated patients who experienced LFT abnormalities until such abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline.

Geron obtained follow-up information from patients in the previously ongoing company-sponsored phase 2 trials in ET/PV and MM. These data were submitted to the FDA as part of the company’s complete response.

The company’s analysis of these data showed that, in the ET/PV trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in 14 of 18 follow-up patients. For the remaining 4 patients, at the time of the data cut-off, 3 patients showed improvement in LFT abnormalities, and 1 patient had unresolved LFT abnormalities. Two of the remaining 4 patients continue in follow-up.

In the MM trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in all 9 follow-up patients. In addition, no emergent hepatic adverse events were reported during follow-up for either study.

The FDA also requested information regarding the reversibility of liver toxicity after chronic imetelstat administration in animals. Geron submitted data from its non-clinical toxicology studies, which included a 6-month study in mice and a 9-month study in cynomolgus monkeys.

In these studies, no clinical pathology changes indicative of hepatocellular injury were observed, and no clear signal of LFT abnormalities were identified.

With the clinical hold lifted, a multicenter phase 2 trial in MF is projected to begin in the first half of 2015. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed the full clinical hold placed on the investigational new drug application for the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat.

The hold, which was placed in March, suspended a phase 2 study of imetelstat in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) or polycythemia vera (PV), as well as a phase 2 study of the drug in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The hold also delayed a planned phase 2 trial in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

And it temporarily suspended an investigator-sponsored trial of imetelstat in MF. The FDA lifted the hold on the investigator-sponsored trial in June.

The FDA halted these trials due to reports of persistent, low-grade liver function test (LFT) abnormalities observed in the phase 2 study of ET/PV patients and the potential risk of chronic liver injury following long-term exposure to imetelstat. The FDA expressed concern about whether these LFT abnormalities are reversible.

Now, data provided by the Geron Corporation, the company developing imetelstat, has convinced the FDA to lift the hold on all trials.

The FDA said the proposed clinical development plan for imetelstat, which is focused on high-risk myeloid disorders such as MF, is acceptable. Geron Corporation has said it does not intend to conduct further studies with, or develop imetelstat for, patients with ET or PV.

To address the clinical hold, the FDA required Geron to provide follow-up information from imetelstat-treated patients who experienced LFT abnormalities until such abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline.

Geron obtained follow-up information from patients in the previously ongoing company-sponsored phase 2 trials in ET/PV and MM. These data were submitted to the FDA as part of the company’s complete response.

The company’s analysis of these data showed that, in the ET/PV trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in 14 of 18 follow-up patients. For the remaining 4 patients, at the time of the data cut-off, 3 patients showed improvement in LFT abnormalities, and 1 patient had unresolved LFT abnormalities. Two of the remaining 4 patients continue in follow-up.

In the MM trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in all 9 follow-up patients. In addition, no emergent hepatic adverse events were reported during follow-up for either study.

The FDA also requested information regarding the reversibility of liver toxicity after chronic imetelstat administration in animals. Geron submitted data from its non-clinical toxicology studies, which included a 6-month study in mice and a 9-month study in cynomolgus monkeys.

In these studies, no clinical pathology changes indicative of hepatocellular injury were observed, and no clear signal of LFT abnormalities were identified.

With the clinical hold lifted, a multicenter phase 2 trial in MF is projected to begin in the first half of 2015. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has removed the full clinical hold placed on the investigational new drug application for the telomerase inhibitor imetelstat.

The hold, which was placed in March, suspended a phase 2 study of imetelstat in patients with essential thrombocythemia (ET) or polycythemia vera (PV), as well as a phase 2 study of the drug in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The hold also delayed a planned phase 2 trial in patients with myelofibrosis (MF).

And it temporarily suspended an investigator-sponsored trial of imetelstat in MF. The FDA lifted the hold on the investigator-sponsored trial in June.

The FDA halted these trials due to reports of persistent, low-grade liver function test (LFT) abnormalities observed in the phase 2 study of ET/PV patients and the potential risk of chronic liver injury following long-term exposure to imetelstat. The FDA expressed concern about whether these LFT abnormalities are reversible.

Now, data provided by the Geron Corporation, the company developing imetelstat, has convinced the FDA to lift the hold on all trials.

The FDA said the proposed clinical development plan for imetelstat, which is focused on high-risk myeloid disorders such as MF, is acceptable. Geron Corporation has said it does not intend to conduct further studies with, or develop imetelstat for, patients with ET or PV.

To address the clinical hold, the FDA required Geron to provide follow-up information from imetelstat-treated patients who experienced LFT abnormalities until such abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline.

Geron obtained follow-up information from patients in the previously ongoing company-sponsored phase 2 trials in ET/PV and MM. These data were submitted to the FDA as part of the company’s complete response.

The company’s analysis of these data showed that, in the ET/PV trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in 14 of 18 follow-up patients. For the remaining 4 patients, at the time of the data cut-off, 3 patients showed improvement in LFT abnormalities, and 1 patient had unresolved LFT abnormalities. Two of the remaining 4 patients continue in follow-up.

In the MM trial, LFT abnormalities resolved to normal or baseline in all 9 follow-up patients. In addition, no emergent hepatic adverse events were reported during follow-up for either study.

The FDA also requested information regarding the reversibility of liver toxicity after chronic imetelstat administration in animals. Geron submitted data from its non-clinical toxicology studies, which included a 6-month study in mice and a 9-month study in cynomolgus monkeys.

In these studies, no clinical pathology changes indicative of hepatocellular injury were observed, and no clear signal of LFT abnormalities were identified.

With the clinical hold lifted, a multicenter phase 2 trial in MF is projected to begin in the first half of 2015. ![]()

Brentuximab tops chemo in HL, doc says

NEW YORK—Brentuximab vendotin—not conventional chemotherapy—is the second-line regimen of choice for recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients prior to stem cell transplant, according to a speaker at the Lymphoma & Myeloma 2014 congress.

Catherine Diefenbach, MD, of New York University’s Langone Medical Center in New York, argued that conventional chemotherapy, the existing paradigm for first salvage therapy, does not maximize a cure or minimize toxicity, is inconvenient, and is not cost-effective.

She noted that a quarter of HL patients relapse or have a primary refractory diagnosis.

“These are young patients,” Dr Diefenbach said. “Autologous stem cell transplant [ASCT] cures only half of them. There is no other established curative salvage therapy.”

She noted that the median time to progression with relapse after transplant is 3.8 months in patients treated with subsequent therapy, with a median survival of 26 months.

After ASCT, the median progression-free survival with relapse is 1.3 years. And about three-quarters of relapses occur within the first year.

“Achieving a complete response [CR] before ASCT is the most important factor in determining long-term disease-free survival and to maximizing transplant-related benefit,” Dr Diefenbach said. “High overall response rates [ORRs] do not equal high CR. Only one-third of patients achieve a CR [with chemotherapy].”

She said studies have shown that chemotherapy with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) leads to a 3-year event-free survival rate of 22%. Post-ASCT, event-free survival increases to more than 52%.

The overall survival post-ASCT is 44%. The median survival of patients who do not get therapy is 3.7 months. Myelosuppression and deaths are common.

“Conventional chemotherapy fails,” Dr Diefenbach continued. “There is inadequate disease control, unacceptable toxicity, it’s not cost-effective, requires patients to be hospitalized, and there is no clear standard of care.”

On the other hand, brentuximab as first salvage is highly active with minimal adverse events in relapsed HL.

“Rash is the only grade 3-4 toxicity,” Dr Diefenbach said. “There are no significant cytopenias [and] no febrile neutropenia. Growth factor support is not required, and it’s administered outpatient.”

Using brentuximab as second-line therapy results in an ORR of 85.7% and a CR of 50%, she added. And ASCT after brentuximab shows similar successes and toxicities.

Brentuximab followed by ICE leads to high rates of PET normalization, allows successful transplantation of virtually all evaluable patients, and poses no issues with stem cell collection.

Furthermore, studies show a 92% disease-free survival, with minimal toxicity at 10 months of follow-up.

In conclusion, Dr Diefenbach said, “Maximizing disease control prior to ASCT will maximize cure from ASCT. Brentuximab vedotin is a novel agent that leads to a high ORR and high CR rate with low toxicity and outpatient administration. In contrast, conventional chemotherapy fails to provide a high CR rate, has unacceptable toxicity, and there is no single standard of care.”

For an opposing opinion on salvage in HL, see “Speaker adovcates chemo-based salvage in HL.” ![]()

NEW YORK—Brentuximab vendotin—not conventional chemotherapy—is the second-line regimen of choice for recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients prior to stem cell transplant, according to a speaker at the Lymphoma & Myeloma 2014 congress.

Catherine Diefenbach, MD, of New York University’s Langone Medical Center in New York, argued that conventional chemotherapy, the existing paradigm for first salvage therapy, does not maximize a cure or minimize toxicity, is inconvenient, and is not cost-effective.

She noted that a quarter of HL patients relapse or have a primary refractory diagnosis.

“These are young patients,” Dr Diefenbach said. “Autologous stem cell transplant [ASCT] cures only half of them. There is no other established curative salvage therapy.”

She noted that the median time to progression with relapse after transplant is 3.8 months in patients treated with subsequent therapy, with a median survival of 26 months.

After ASCT, the median progression-free survival with relapse is 1.3 years. And about three-quarters of relapses occur within the first year.

“Achieving a complete response [CR] before ASCT is the most important factor in determining long-term disease-free survival and to maximizing transplant-related benefit,” Dr Diefenbach said. “High overall response rates [ORRs] do not equal high CR. Only one-third of patients achieve a CR [with chemotherapy].”

She said studies have shown that chemotherapy with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) leads to a 3-year event-free survival rate of 22%. Post-ASCT, event-free survival increases to more than 52%.

The overall survival post-ASCT is 44%. The median survival of patients who do not get therapy is 3.7 months. Myelosuppression and deaths are common.

“Conventional chemotherapy fails,” Dr Diefenbach continued. “There is inadequate disease control, unacceptable toxicity, it’s not cost-effective, requires patients to be hospitalized, and there is no clear standard of care.”

On the other hand, brentuximab as first salvage is highly active with minimal adverse events in relapsed HL.

“Rash is the only grade 3-4 toxicity,” Dr Diefenbach said. “There are no significant cytopenias [and] no febrile neutropenia. Growth factor support is not required, and it’s administered outpatient.”

Using brentuximab as second-line therapy results in an ORR of 85.7% and a CR of 50%, she added. And ASCT after brentuximab shows similar successes and toxicities.

Brentuximab followed by ICE leads to high rates of PET normalization, allows successful transplantation of virtually all evaluable patients, and poses no issues with stem cell collection.

Furthermore, studies show a 92% disease-free survival, with minimal toxicity at 10 months of follow-up.

In conclusion, Dr Diefenbach said, “Maximizing disease control prior to ASCT will maximize cure from ASCT. Brentuximab vedotin is a novel agent that leads to a high ORR and high CR rate with low toxicity and outpatient administration. In contrast, conventional chemotherapy fails to provide a high CR rate, has unacceptable toxicity, and there is no single standard of care.”

For an opposing opinion on salvage in HL, see “Speaker adovcates chemo-based salvage in HL.” ![]()

NEW YORK—Brentuximab vendotin—not conventional chemotherapy—is the second-line regimen of choice for recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients prior to stem cell transplant, according to a speaker at the Lymphoma & Myeloma 2014 congress.

Catherine Diefenbach, MD, of New York University’s Langone Medical Center in New York, argued that conventional chemotherapy, the existing paradigm for first salvage therapy, does not maximize a cure or minimize toxicity, is inconvenient, and is not cost-effective.

She noted that a quarter of HL patients relapse or have a primary refractory diagnosis.

“These are young patients,” Dr Diefenbach said. “Autologous stem cell transplant [ASCT] cures only half of them. There is no other established curative salvage therapy.”

She noted that the median time to progression with relapse after transplant is 3.8 months in patients treated with subsequent therapy, with a median survival of 26 months.

After ASCT, the median progression-free survival with relapse is 1.3 years. And about three-quarters of relapses occur within the first year.

“Achieving a complete response [CR] before ASCT is the most important factor in determining long-term disease-free survival and to maximizing transplant-related benefit,” Dr Diefenbach said. “High overall response rates [ORRs] do not equal high CR. Only one-third of patients achieve a CR [with chemotherapy].”

She said studies have shown that chemotherapy with ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) leads to a 3-year event-free survival rate of 22%. Post-ASCT, event-free survival increases to more than 52%.

The overall survival post-ASCT is 44%. The median survival of patients who do not get therapy is 3.7 months. Myelosuppression and deaths are common.

“Conventional chemotherapy fails,” Dr Diefenbach continued. “There is inadequate disease control, unacceptable toxicity, it’s not cost-effective, requires patients to be hospitalized, and there is no clear standard of care.”

On the other hand, brentuximab as first salvage is highly active with minimal adverse events in relapsed HL.

“Rash is the only grade 3-4 toxicity,” Dr Diefenbach said. “There are no significant cytopenias [and] no febrile neutropenia. Growth factor support is not required, and it’s administered outpatient.”

Using brentuximab as second-line therapy results in an ORR of 85.7% and a CR of 50%, she added. And ASCT after brentuximab shows similar successes and toxicities.

Brentuximab followed by ICE leads to high rates of PET normalization, allows successful transplantation of virtually all evaluable patients, and poses no issues with stem cell collection.

Furthermore, studies show a 92% disease-free survival, with minimal toxicity at 10 months of follow-up.

In conclusion, Dr Diefenbach said, “Maximizing disease control prior to ASCT will maximize cure from ASCT. Brentuximab vedotin is a novel agent that leads to a high ORR and high CR rate with low toxicity and outpatient administration. In contrast, conventional chemotherapy fails to provide a high CR rate, has unacceptable toxicity, and there is no single standard of care.”

For an opposing opinion on salvage in HL, see “Speaker adovcates chemo-based salvage in HL.” ![]()

Transfusions benefit adults with sickle cell disease

PHILADELPHIA—Blood transfusions can provide pain relief in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea, a pilot study suggests.

Patients had fewer visits to the emergency department (ED) and fewer hospital admissions for pain control after they received chronic transfusions for pain prophylaxis than they did prior to receiving transfusions.

Matthew S. Karafin, MD, of the Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, presented these results at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract S42-030G).

“Pain in adults with sickle cell disease is probably one of the most important things that we deal with in our clinics,” he began. “It is the leading cause of morbidity in this population.”

Dr Karafin also noted that adults with SCD seem to experience pain differently from children, reporting more of a constant pain, as opposed to the episodic pain observed in kids. And although previous studies have suggested that transfusions do provide pain relief in SCD, most of those studies have focused on children.

So Dr Karafin and his colleagues set out to determine the impact of prophylactic transfusions on the rate of serious pain episodes in adults with SCD. The team retrospectively analyzed a cohort of patients who received chronic transfusions at 3- to 8-week intervals from January 2009 to October 2013.

The researchers defined chronic transfusions as receiving blood—either simple transfusions or red cell exchanges—in an outpatient setting 3 days a week with the goal of controlling hemoglobin (Hb) S percentage, maintaining it at less than 30%.

Patients had to have at least 1 ED or hospital visit for severe pain per month prior to starting transfusions, they were required to have failed hydroxyurea therapy, and they had to have at least 3 months both on and off chronic transfusions. The patients could have no other reason for receiving chronic transfusions (ie, no previous stroke).

So the study included 17 patients, 12 of whom were female. Fifteen (88.1%) had Hb SS disease, and 2 had Hb SC disease. Their median age was 26 (range, 20-54).

“We were able to record 541 total ED admissions over the study period and 404 total hospital admissions,” Dr Karafin said. “The median study evaluation period pre-transfusion was about 3.5 years, and we were able to study [patients for] a median of more than a year for the post-transfusion protocol period.”

Dr Karafin also noted that most of the patients were not transfusion-naïve, but they received significantly more units after being placed on the transfusion protocol.

The median number of red cell units received per 100 days was 1.2 (range, 0-7.2) pre-transfusion and 10.2 (range, 6.7-24.3) post-transfusion (P=0.0003). Nine of the patients received simple transfusions, and 8 received red cell exchanges.

There was a significant difference in the median Hb S pre- and post-transfusion—79% (range, 26.5%-89.6%) and 30.2% (range, 10.9%-57.4%), respectively (P=0.0003).

But there was no significant difference in median ferritin levels—1128.2 ng/mL (range, 65.4-11,130) and 2632.8 ng/mL (range, 16.7-8023.6), respectively (P=0.18). Dr Karafin said this could be explained by the fact that patients were not transfusion-naïve prior to starting the protocol.

Similarly, the median new alloantibody rate per 100 units was 0 both pre- and post-transfusion. This may be due to the fact that all patients received C-, E-, and KEL-matched blood, as well as the freshest available units, Dr Karafin said.

He and his colleagues also found that the median ED admission rate was significantly lower post-transfusion compared to pre-transfusion—0.79 (range, 0-6.6) and 2 (range, 0.4-11) visits every 100 days, respectively (P=0.04).

Thirteen patients (76.5%) had a reduced ED visit rate after chronic transfusion, and there was a 60.5% reduction in the ED visit rate overall.

Likewise, the median hospital admission rate decreased from 1.7 per 100 days (range, 0.05-5.8) pre-transfusion to 1.3 per 100 days (range, 0.2-3.2) post-transfusion (P=0.004).

Fifteen patients (88.2%) had reduced hospital admissions after chronic transfusion, and there was a 20.3% reduction in hospital admissions overall.

Dr Karafin noted that this study had a number of limitations, including a small number of patients, its retrospective nature, and the fact that it was conducted at a comprehensive SCD clinic.

“However, limitations aside, we found significant evidence to support that the findings observed in children seem to be similar in the adult population,” he said.

Namely, chronic transfusions can prevent serious pain episodes in adults with SCD who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea. ![]()

PHILADELPHIA—Blood transfusions can provide pain relief in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea, a pilot study suggests.

Patients had fewer visits to the emergency department (ED) and fewer hospital admissions for pain control after they received chronic transfusions for pain prophylaxis than they did prior to receiving transfusions.

Matthew S. Karafin, MD, of the Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, presented these results at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract S42-030G).

“Pain in adults with sickle cell disease is probably one of the most important things that we deal with in our clinics,” he began. “It is the leading cause of morbidity in this population.”

Dr Karafin also noted that adults with SCD seem to experience pain differently from children, reporting more of a constant pain, as opposed to the episodic pain observed in kids. And although previous studies have suggested that transfusions do provide pain relief in SCD, most of those studies have focused on children.

So Dr Karafin and his colleagues set out to determine the impact of prophylactic transfusions on the rate of serious pain episodes in adults with SCD. The team retrospectively analyzed a cohort of patients who received chronic transfusions at 3- to 8-week intervals from January 2009 to October 2013.

The researchers defined chronic transfusions as receiving blood—either simple transfusions or red cell exchanges—in an outpatient setting 3 days a week with the goal of controlling hemoglobin (Hb) S percentage, maintaining it at less than 30%.

Patients had to have at least 1 ED or hospital visit for severe pain per month prior to starting transfusions, they were required to have failed hydroxyurea therapy, and they had to have at least 3 months both on and off chronic transfusions. The patients could have no other reason for receiving chronic transfusions (ie, no previous stroke).

So the study included 17 patients, 12 of whom were female. Fifteen (88.1%) had Hb SS disease, and 2 had Hb SC disease. Their median age was 26 (range, 20-54).

“We were able to record 541 total ED admissions over the study period and 404 total hospital admissions,” Dr Karafin said. “The median study evaluation period pre-transfusion was about 3.5 years, and we were able to study [patients for] a median of more than a year for the post-transfusion protocol period.”

Dr Karafin also noted that most of the patients were not transfusion-naïve, but they received significantly more units after being placed on the transfusion protocol.

The median number of red cell units received per 100 days was 1.2 (range, 0-7.2) pre-transfusion and 10.2 (range, 6.7-24.3) post-transfusion (P=0.0003). Nine of the patients received simple transfusions, and 8 received red cell exchanges.

There was a significant difference in the median Hb S pre- and post-transfusion—79% (range, 26.5%-89.6%) and 30.2% (range, 10.9%-57.4%), respectively (P=0.0003).

But there was no significant difference in median ferritin levels—1128.2 ng/mL (range, 65.4-11,130) and 2632.8 ng/mL (range, 16.7-8023.6), respectively (P=0.18). Dr Karafin said this could be explained by the fact that patients were not transfusion-naïve prior to starting the protocol.

Similarly, the median new alloantibody rate per 100 units was 0 both pre- and post-transfusion. This may be due to the fact that all patients received C-, E-, and KEL-matched blood, as well as the freshest available units, Dr Karafin said.

He and his colleagues also found that the median ED admission rate was significantly lower post-transfusion compared to pre-transfusion—0.79 (range, 0-6.6) and 2 (range, 0.4-11) visits every 100 days, respectively (P=0.04).

Thirteen patients (76.5%) had a reduced ED visit rate after chronic transfusion, and there was a 60.5% reduction in the ED visit rate overall.

Likewise, the median hospital admission rate decreased from 1.7 per 100 days (range, 0.05-5.8) pre-transfusion to 1.3 per 100 days (range, 0.2-3.2) post-transfusion (P=0.004).

Fifteen patients (88.2%) had reduced hospital admissions after chronic transfusion, and there was a 20.3% reduction in hospital admissions overall.

Dr Karafin noted that this study had a number of limitations, including a small number of patients, its retrospective nature, and the fact that it was conducted at a comprehensive SCD clinic.

“However, limitations aside, we found significant evidence to support that the findings observed in children seem to be similar in the adult population,” he said.

Namely, chronic transfusions can prevent serious pain episodes in adults with SCD who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea. ![]()

PHILADELPHIA—Blood transfusions can provide pain relief in adults with sickle cell disease (SCD) who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea, a pilot study suggests.

Patients had fewer visits to the emergency department (ED) and fewer hospital admissions for pain control after they received chronic transfusions for pain prophylaxis than they did prior to receiving transfusions.

Matthew S. Karafin, MD, of the Blood Center of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, presented these results at the AABB Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract S42-030G).

“Pain in adults with sickle cell disease is probably one of the most important things that we deal with in our clinics,” he began. “It is the leading cause of morbidity in this population.”

Dr Karafin also noted that adults with SCD seem to experience pain differently from children, reporting more of a constant pain, as opposed to the episodic pain observed in kids. And although previous studies have suggested that transfusions do provide pain relief in SCD, most of those studies have focused on children.

So Dr Karafin and his colleagues set out to determine the impact of prophylactic transfusions on the rate of serious pain episodes in adults with SCD. The team retrospectively analyzed a cohort of patients who received chronic transfusions at 3- to 8-week intervals from January 2009 to October 2013.

The researchers defined chronic transfusions as receiving blood—either simple transfusions or red cell exchanges—in an outpatient setting 3 days a week with the goal of controlling hemoglobin (Hb) S percentage, maintaining it at less than 30%.

Patients had to have at least 1 ED or hospital visit for severe pain per month prior to starting transfusions, they were required to have failed hydroxyurea therapy, and they had to have at least 3 months both on and off chronic transfusions. The patients could have no other reason for receiving chronic transfusions (ie, no previous stroke).

So the study included 17 patients, 12 of whom were female. Fifteen (88.1%) had Hb SS disease, and 2 had Hb SC disease. Their median age was 26 (range, 20-54).

“We were able to record 541 total ED admissions over the study period and 404 total hospital admissions,” Dr Karafin said. “The median study evaluation period pre-transfusion was about 3.5 years, and we were able to study [patients for] a median of more than a year for the post-transfusion protocol period.”

Dr Karafin also noted that most of the patients were not transfusion-naïve, but they received significantly more units after being placed on the transfusion protocol.

The median number of red cell units received per 100 days was 1.2 (range, 0-7.2) pre-transfusion and 10.2 (range, 6.7-24.3) post-transfusion (P=0.0003). Nine of the patients received simple transfusions, and 8 received red cell exchanges.

There was a significant difference in the median Hb S pre- and post-transfusion—79% (range, 26.5%-89.6%) and 30.2% (range, 10.9%-57.4%), respectively (P=0.0003).

But there was no significant difference in median ferritin levels—1128.2 ng/mL (range, 65.4-11,130) and 2632.8 ng/mL (range, 16.7-8023.6), respectively (P=0.18). Dr Karafin said this could be explained by the fact that patients were not transfusion-naïve prior to starting the protocol.

Similarly, the median new alloantibody rate per 100 units was 0 both pre- and post-transfusion. This may be due to the fact that all patients received C-, E-, and KEL-matched blood, as well as the freshest available units, Dr Karafin said.

He and his colleagues also found that the median ED admission rate was significantly lower post-transfusion compared to pre-transfusion—0.79 (range, 0-6.6) and 2 (range, 0.4-11) visits every 100 days, respectively (P=0.04).

Thirteen patients (76.5%) had a reduced ED visit rate after chronic transfusion, and there was a 60.5% reduction in the ED visit rate overall.

Likewise, the median hospital admission rate decreased from 1.7 per 100 days (range, 0.05-5.8) pre-transfusion to 1.3 per 100 days (range, 0.2-3.2) post-transfusion (P=0.004).

Fifteen patients (88.2%) had reduced hospital admissions after chronic transfusion, and there was a 20.3% reduction in hospital admissions overall.

Dr Karafin noted that this study had a number of limitations, including a small number of patients, its retrospective nature, and the fact that it was conducted at a comprehensive SCD clinic.

“However, limitations aside, we found significant evidence to support that the findings observed in children seem to be similar in the adult population,” he said.

Namely, chronic transfusions can prevent serious pain episodes in adults with SCD who have failed treatment with hydroxyurea. ![]()

Speaker advocates chemo-based salvage in HL

Credit: Rhoda Baer