User login

OxyContin marketing push still exacting a deadly toll, study says

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The uptick in rates of infectious diseases, namely, hepatitis and infective endocarditis, occurred after 2010, when OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma reformulated OxyContin to make it harder to crush and snort. This led many people who were already addicted to the powerful pain pills to move on to injecting heroin or fentanyl, which fueled the spread of infectious disease.

“Our results suggest that the mortality and morbidity consequences of OxyContin marketing continue to be salient more than 25 years later,” write Julia Dennett, PhD, and Gregg Gonsalves, PhD, with Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, Conn.

Their study was published online in Health Affairs.

Long-term effects revealed

Until now, the long-term effects of widespread OxyContin marketing with regard to complications of injection drug use were unknown.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves evaluated the effects of OxyContin marketing on the long-term trajectories of various injection drug use–related outcomes. Using a difference-in-difference analysis, they compared states with high vs. low exposure to OxyContin marketing before and after the 2010 reformulation of the drug.

Before 2010, rates of infections associated with injection drug use and overdose deaths were similar in high- and low-marketing states, they found.

Those rates diverged after the 2010 reformulation, with more infections related to injection drug use in states exposed to more marketing.

Specifically, from 2010 until 2020, high-exposure states saw, on average, an additional 0.85 acute hepatitis B cases, 0.83 hepatitis C cases, and 0.62 cases of death from infective endocarditis per 100,000 residents.

High-exposure states also had 5.3 more deaths per 100,000 residents from synthetic opioid overdose.

“Prior to 2010, among these states, there were generally no statistically significant differences in these outcomes. After 2010, you saw them diverge dramatically,” Dr. Dennett said in a news release.

Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves say their findings support the view that the opioid epidemic is creating a converging public health crisis, as it is fueling a surge in infectious diseases, particularly hepatitis, infective endocarditis, and HIV.

“This study highlights a critical need for actions to address the spread of viral and bacterial infections and overdose associated with injection drug use, both in the states that were subject to Purdue’s promotional campaign and across the U.S. more broadly,” they add.

Purdue Pharma did not provide a comment on the study.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Disclosures for Dr. Dennett and Dr. Gonsalves were not available.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Cigna accused of using AI, not doctors, to deny claims: Lawsuit

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

and forcing providers to bill patients in full.

In a complaint filed recently in California’s eastern district court, plaintiffs and Cigna health plan members Suzanne Kisting-Leung and Ayesha Smiley and their attorneys say that Cigna violates state insurance regulations by failing to conduct a “thorough, fair, and objective” review of their and other members’ claims.

The lawsuit says that, instead, Cigna relies on an algorithm, PxDx, to review and frequently deny medically necessary claims. According to court records, the system allows Cigna’s doctors to “instantly reject claims on medical grounds without ever opening patient files.” With use of the system, the average claims processing time is 1.2 seconds.

Cigna says it uses technology to verify coding on standard, low-cost procedures and to expedite physician reimbursement. In a statement to CBS News, the company called the lawsuit “highly questionable.”

The case highlights growing concerns about AI and its ability to replace humans for tasks and interactions in health care, business, and beyond. Public advocacy law firm Clarkson, which is representing the plaintiffs, has previously sued tech giants Google and ChatGPT creator OpenAI for harvesting Internet users’ personal and professional data to train their AI systems.

According to the complaint, Cigna denied the plaintiffs medically necessary tests, including blood work to screen for vitamin D deficiency and ultrasounds for patients suspected of having ovarian cancer. The plaintiffs’ attempts to appeal were unfruitful, and they were forced to pay out of pocket.

The plaintiff’s attorneys argue that the claims do not undergo more detailed reviews by physicians and employees, as mandated by California insurance laws, and that Cigna benefits by saving on labor costs.

Clarkson is demanding a jury trial and has asked the court to certify the Cigna case as a federal class action, potentially allowing the insurer’s other 2 million health plan members in California to join the lawsuit.

I. Glenn Cohen, JD, deputy dean and professor at Harvard Law School, Cambridge, Mass., said in an interview that this is the first lawsuit he’s aware of in which AI was involved in denying health insurance claims and that it is probably an uphill battle for the plaintiffs.

“In the last 25 years, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions have made getting a class action approved more difficult. If allowed to go forward as a class action, which Cigna is likely to vigorously oppose, then the pressure on Cigna to settle the case becomes enormous,” he said.

The allegations come after a recent deep dive by the nonprofit ProPublica uncovered similar claim denial issues. One physician who worked for Cigna told the nonprofit that he and other company doctors essentially rubber-stamped the denials in batches, which took “all of 10 seconds to do 50 at a time.”

In 2022, the American Medical Association and two state physician groups joined another class action against Cigna stemming from allegations that the insurer’s intermediary, Multiplan, intentionally underpaid medical claims. And in March, Cigna’s pharmacy benefit manager, Express Scripts, was accused of conspiring with other PBMs to drive up prescription drug prices for Ohio consumers, violating state antitrust laws.

Mr. Cohen said he expects Cigna to push back in court about the California class size, which the plaintiff’s attorneys hope will encompass all Cigna health plan members in the state.

“The injury is primarily to those whose claims were denied by AI, presumably a much smaller set of individuals and harder to identify,” said Mr. Cohen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Black women weigh emerging risks of ‘creamy crack’ hair straighteners

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

FDA approves first pill for postpartum depression

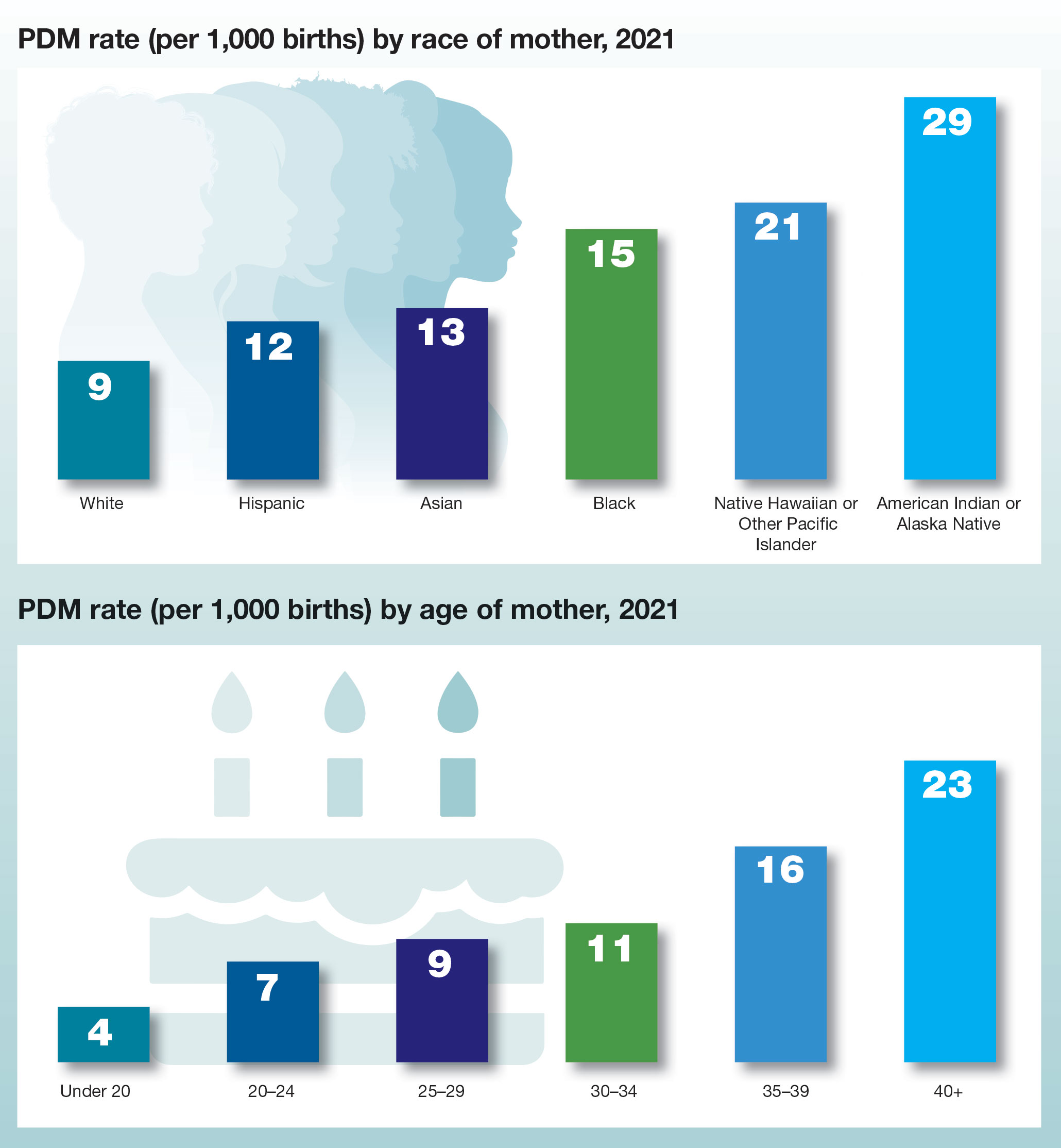

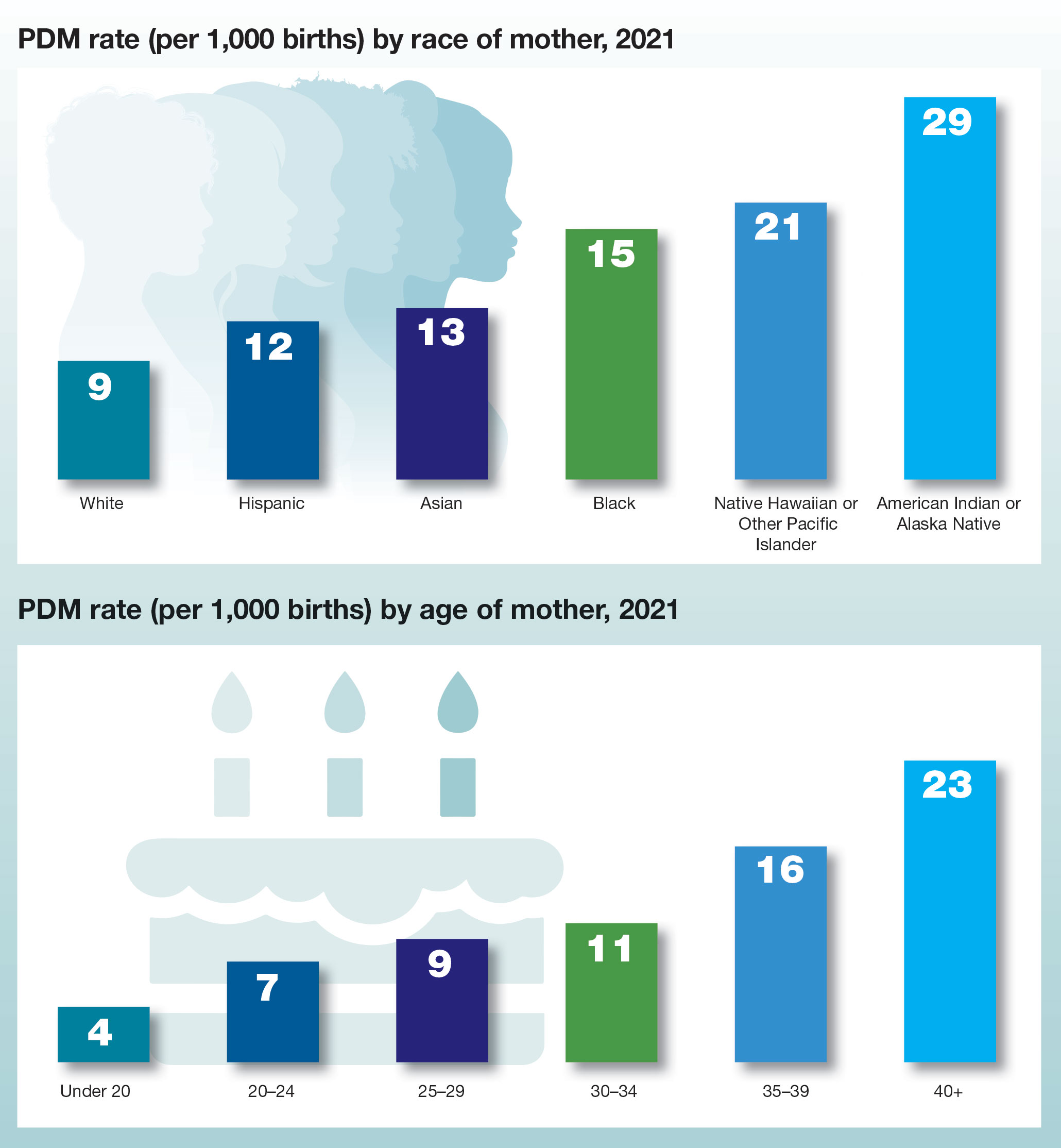

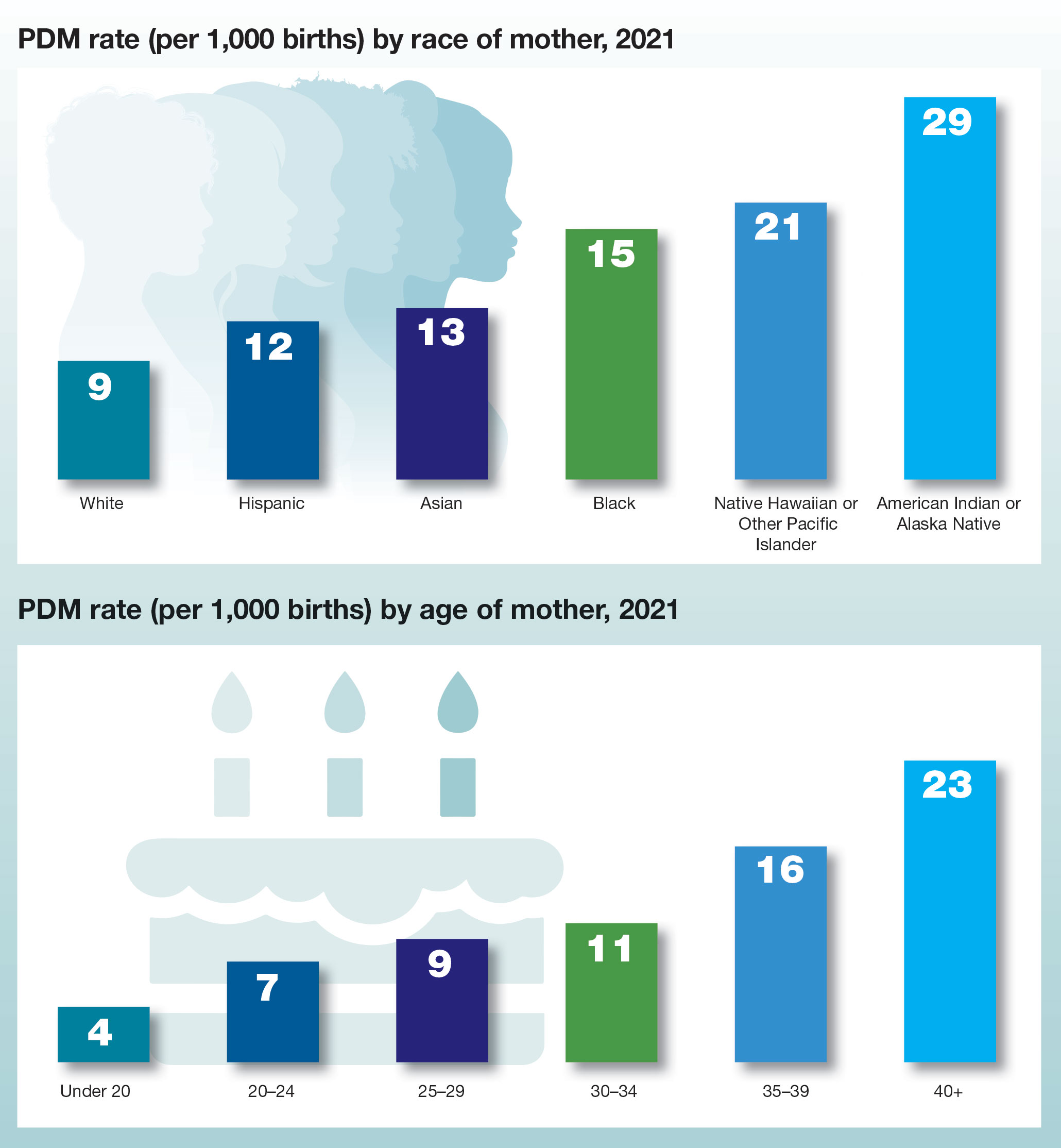

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rising viral load on dolutegravir? Investigators try fix before switch

Brisbane, Australia – , according to new data from the ADVANCE trial.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” said Andrew Hill, MD, from the department of pharmacology and therapeutics at the University of Liverpool, England.

The new data was presented here at the International AIDS Society conference on HIV Science. The ADVANCE trial is a three-arm randomized study involving 1,053 treatment-naive individuals comparing two triple-therapy combinations — dolutegravir, emtricitabine, and one of two tenofovir prodrugs – with a standard care regimen of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz.

Although the usual approach for someone in a clinical trial who experiences elevations in HIV RNA levels while on a dolutegravir-based treatment is to switch them to another therapy, the ADVANCE investigators opted for a different strategy.

“We actually continued treatment despite high viral load, and we didn’t have standard discontinuation preferences,” Dr. Hill said at the meeting. They instead provided counseling about adherence, which gave an opportunity to examine viral resuppression rates in participants in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz arms.

This revealed that 95% of patients in the two dolutegravir arms of the study were able to achieve resuppression of their viral load – defined as below 50 viral RNA copies per mL – without any emergence of resistance.

The guidelines

Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that anyone whose viral load goes above 1,000 copies per mL who is on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor such as efavirenz should be switched to an appropriate regimen.

Those who experience viremia on an integrase inhibitor such as dolutegravir should receive adherence counseling, have a repeat viral load test done in 3 months, and – if their viral load is still elevated – be switched to another regimen.

Dr. Hill and his team were examining how this might play out in a clinical trial setting and they found that there were a similar number of episodes of initial virologic failure in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz groups.

But after adherence counseling, testing for resistance and – if no resistance was evident – continuation with treatment, they saw differences emerge between the two groups.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” he said.

Time to viral resuppression

At 24 weeks after restarting treatment, 88% of people in the dolutegravir group had resuppressed their viral RNA, compared with 46% of people in the efavirenz group. At 48 weeks, those figures were 95% and 66%, respectively.

Dr. Hill pointed out that a significant number of people were lost to follow-up after virologic failure, and genotyping was not performed at baseline.

We addressed the question of how much adherence counseling should be undertaken in people who experienced viremia while on dolutegravir therapy, Dr. Hill said, particularly as there were often very good reasons for lack of adherence, such as homelessness.

“If you can get through those difficult phases, people can go back on their meds,” he said in an interview. “It’s almost a sociological problem rather than a clinical issue.”

And with efavirenz and the lower rates of resuppression observed in the study, Dr. Hill said it was a more fragile drug, so viremia therefore provided the opportunity for resistance to emerge, “and then once the resistant virus is there, you can’t get virus undetectable.”

Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at the Mortimer Market Centre in London, who was not involved in the study, said the results support recommendations to give people on drugs such as dolutegravir, which have a high genetic barrier to resistance, more time to improve their adherence before switching to another therapy.

“Although it provides that reassuring proof of concept, it doesn’t negate the importance of having to continue to monitor, because nothing is infallible,” she told this news organization. “We’ve talked about high-barrier drugs in the past, and you do start seeing resistance emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Brisbane, Australia – , according to new data from the ADVANCE trial.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” said Andrew Hill, MD, from the department of pharmacology and therapeutics at the University of Liverpool, England.

The new data was presented here at the International AIDS Society conference on HIV Science. The ADVANCE trial is a three-arm randomized study involving 1,053 treatment-naive individuals comparing two triple-therapy combinations — dolutegravir, emtricitabine, and one of two tenofovir prodrugs – with a standard care regimen of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz.

Although the usual approach for someone in a clinical trial who experiences elevations in HIV RNA levels while on a dolutegravir-based treatment is to switch them to another therapy, the ADVANCE investigators opted for a different strategy.

“We actually continued treatment despite high viral load, and we didn’t have standard discontinuation preferences,” Dr. Hill said at the meeting. They instead provided counseling about adherence, which gave an opportunity to examine viral resuppression rates in participants in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz arms.

This revealed that 95% of patients in the two dolutegravir arms of the study were able to achieve resuppression of their viral load – defined as below 50 viral RNA copies per mL – without any emergence of resistance.

The guidelines

Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that anyone whose viral load goes above 1,000 copies per mL who is on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor such as efavirenz should be switched to an appropriate regimen.

Those who experience viremia on an integrase inhibitor such as dolutegravir should receive adherence counseling, have a repeat viral load test done in 3 months, and – if their viral load is still elevated – be switched to another regimen.

Dr. Hill and his team were examining how this might play out in a clinical trial setting and they found that there were a similar number of episodes of initial virologic failure in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz groups.

But after adherence counseling, testing for resistance and – if no resistance was evident – continuation with treatment, they saw differences emerge between the two groups.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” he said.

Time to viral resuppression

At 24 weeks after restarting treatment, 88% of people in the dolutegravir group had resuppressed their viral RNA, compared with 46% of people in the efavirenz group. At 48 weeks, those figures were 95% and 66%, respectively.

Dr. Hill pointed out that a significant number of people were lost to follow-up after virologic failure, and genotyping was not performed at baseline.

We addressed the question of how much adherence counseling should be undertaken in people who experienced viremia while on dolutegravir therapy, Dr. Hill said, particularly as there were often very good reasons for lack of adherence, such as homelessness.

“If you can get through those difficult phases, people can go back on their meds,” he said in an interview. “It’s almost a sociological problem rather than a clinical issue.”

And with efavirenz and the lower rates of resuppression observed in the study, Dr. Hill said it was a more fragile drug, so viremia therefore provided the opportunity for resistance to emerge, “and then once the resistant virus is there, you can’t get virus undetectable.”

Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at the Mortimer Market Centre in London, who was not involved in the study, said the results support recommendations to give people on drugs such as dolutegravir, which have a high genetic barrier to resistance, more time to improve their adherence before switching to another therapy.

“Although it provides that reassuring proof of concept, it doesn’t negate the importance of having to continue to monitor, because nothing is infallible,” she told this news organization. “We’ve talked about high-barrier drugs in the past, and you do start seeing resistance emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Brisbane, Australia – , according to new data from the ADVANCE trial.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” said Andrew Hill, MD, from the department of pharmacology and therapeutics at the University of Liverpool, England.

The new data was presented here at the International AIDS Society conference on HIV Science. The ADVANCE trial is a three-arm randomized study involving 1,053 treatment-naive individuals comparing two triple-therapy combinations — dolutegravir, emtricitabine, and one of two tenofovir prodrugs – with a standard care regimen of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz.

Although the usual approach for someone in a clinical trial who experiences elevations in HIV RNA levels while on a dolutegravir-based treatment is to switch them to another therapy, the ADVANCE investigators opted for a different strategy.

“We actually continued treatment despite high viral load, and we didn’t have standard discontinuation preferences,” Dr. Hill said at the meeting. They instead provided counseling about adherence, which gave an opportunity to examine viral resuppression rates in participants in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz arms.

This revealed that 95% of patients in the two dolutegravir arms of the study were able to achieve resuppression of their viral load – defined as below 50 viral RNA copies per mL – without any emergence of resistance.

The guidelines

Current World Health Organization guidelines recommend that anyone whose viral load goes above 1,000 copies per mL who is on a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor such as efavirenz should be switched to an appropriate regimen.

Those who experience viremia on an integrase inhibitor such as dolutegravir should receive adherence counseling, have a repeat viral load test done in 3 months, and – if their viral load is still elevated – be switched to another regimen.

Dr. Hill and his team were examining how this might play out in a clinical trial setting and they found that there were a similar number of episodes of initial virologic failure in both the dolutegravir and efavirenz groups.

But after adherence counseling, testing for resistance and – if no resistance was evident – continuation with treatment, they saw differences emerge between the two groups.

“What we saw was a faster time to resuppression in the people followed-up long term on dolutegravir and also a higher percentage of people becoming suppressed when they remained on dolutegravir,” he said.

Time to viral resuppression

At 24 weeks after restarting treatment, 88% of people in the dolutegravir group had resuppressed their viral RNA, compared with 46% of people in the efavirenz group. At 48 weeks, those figures were 95% and 66%, respectively.

Dr. Hill pointed out that a significant number of people were lost to follow-up after virologic failure, and genotyping was not performed at baseline.

We addressed the question of how much adherence counseling should be undertaken in people who experienced viremia while on dolutegravir therapy, Dr. Hill said, particularly as there were often very good reasons for lack of adherence, such as homelessness.

“If you can get through those difficult phases, people can go back on their meds,” he said in an interview. “It’s almost a sociological problem rather than a clinical issue.”

And with efavirenz and the lower rates of resuppression observed in the study, Dr. Hill said it was a more fragile drug, so viremia therefore provided the opportunity for resistance to emerge, “and then once the resistant virus is there, you can’t get virus undetectable.”

Laura Waters, MD, a genitourinary and HIV medicine consultant at the Mortimer Market Centre in London, who was not involved in the study, said the results support recommendations to give people on drugs such as dolutegravir, which have a high genetic barrier to resistance, more time to improve their adherence before switching to another therapy.

“Although it provides that reassuring proof of concept, it doesn’t negate the importance of having to continue to monitor, because nothing is infallible,” she told this news organization. “We’ve talked about high-barrier drugs in the past, and you do start seeing resistance emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT IAS 2023

Many users of skin-lightening product unaware of risks

, a recent cross-sectional survey suggests.

Skin lightening – which uses chemicals to lighten dark areas of skin or to generally lighten skin tone – poses a health risk from potentially unsafe formulations, the authors write in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

Skin lightening is “influenced by colorism, the system of inequality that affords opportunities and privileges to lighter-skinned individuals across racial/ethnic groups,” they add. “Women, in particular, are vulnerable as media and popular culture propagate beauty standards that lighter skin can elevate physical appearance and social acceptance.”

“It is important to recognize that the primary motivator for skin lightening is most often dermatological disease but that, less frequently, it can be colorism,” senior study author Roopal V. Kundu, MD, professor of dermatology and founding director of the Northwestern Center for Ethnic Skin and Hair at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in an email interview.

Skin lightening is a growing, multibillion-dollar, largely unregulated, global industry. Rates have been estimated at 27% in South Africa, 40% in China and South Korea, 77% in Nigeria, but U.S. rates are unknown.

To investigate skin-lightening habits and the role colorism plays in skin-lightening practices in the United States, Dr. Kundu and her colleagues sent an online survey to 578 adults with darker skin who participated in ResearchMatch, a national health registry supported by the National Institutes of Health that connects volunteers with research studies they choose to take part in.

Of the 455 people who completed the 19-item anonymous questionnaire, 238 (52.3%) identified as Black or African American, 83 (18.2%) as Asian, 84 (18.5%) as multiracial, 31 (6.8%) as Hispanic, 14 (3.1%) as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 5 (1.1%) as other. Overall, 364 (80.0%) were women.

The survey asked about demographics, colorism attitudes, skin tone satisfaction, and skin-lightening product use. To assess colorism attitudes, the researchers asked respondents to rate six colorism statements on a Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The statements included “Lighter skin tone increases one’s self-esteem,” and “Lighter skin tone increases one’s chance of having a romantic relationship or getting married.” The researchers also asked them to rate their skin satisfaction levels on a Likert scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied).

Used mostly to treat skin conditions

Despite a lack of medical input, about three-quarters of people who used skin-lightening products reported using them for medical conditions, and around one-quarter used them for general lightening, the researchers report.

Of all respondents, 97 (21.3%) reported using skin-lightening agents. Of them, 71 (73.2%) used them to treat a skin condition such as acne, melasma, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and 26 (26.8% of skin-lightening product users; 5.7% of all respondents) used them for generalized skin lightening.

The 97 users mostly obtained skin-lightening products from chain pharmacy and grocery stores, and also from community beauty stores, abroad, online, and medical providers, while two made them at home.

Skin-lightening product use did not differ with age, gender, race or ethnicity, education level, or immigration status.

Only 22 (22.7%) of the product users consulted a medical provider before using the products, and only 14 (14.4%) received skin-lightening products from medical providers.

In addition, 44 respondents (45.4%) could not identify the active ingredient in their skin-lightening products, but 34 (35.1%) reported using hydroquinone-based products. Other reported active ingredients included ascorbic acid, glycolic acid, salicylic acid, niacinamide, steroids, and mercury.

The face (86 people or 88.7%) and neck (37 or 38.1%) were the most common application sites.

Skin-lightening users were more likely to report that lighter skin was more beautiful and that it increased self-esteem and romantic prospects (P < .001 for all).

Elma Baron, MD, professor of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, advised doctors to remind patients to consult a dermatologist before they use skin-lightening agents. “A dermatologist can evaluate whether there is a true indication for skin-lightening agents and explain the benefits, risks, and limitations of common skin-lightening formulations.

“When dealing with hyperpigmentation, clinicians should remember that ultraviolet light is a potent stimulus for melanogenesis,” added Dr. Baron by email. She was not involved in the study. “Wearing hats and other sun-protective clothing, using sunscreen, and avoiding sunlight during peak hours must always be emphasized.”

Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., often sees patients who try products based on persuasive advertising, not scientific benefit, she said by email.

“The findings are important, because many primary care providers and dermatologists do not realize that patients will use skin-lightening agents simply to provide a glow and in an attempt to attain complexion blending,” added Dr. McMichael, also not involved in the study.

She encouraged doctors to understand what motivates their patients to use skin-lightening agents, so they can effectively communicate what works and what does not work for their condition, as well as inform them about potential risks.

Strengths of the study, Dr. McMichael said, are the number of people surveyed and the inclusion of colorism data not typically gathered in studies of skin-lightening product use. Limitations include whether the reported conditions were what people actually had, and that, with over 50% of respondents being Black, the results may not be generalizable to other groups.