User login

What did you learn in med school that you disagree with now?

Medical education has changed drastically over the years. As theories and practices continue to change, what was once standard 10 or 20 years ago has been replaced with newer ideologies, processes, or technology. It seems likely, then, that you may disagree with some of the things that you learned as medical school has evolved.

Many of their answers include newer philosophies and practice methods.

Treat appropriately for pain

Jacqui O’Kane, DO, a 2013 med school graduate, was taught to avoid prescribing controlled medications whenever possible.

“Initially this attitude made sense to me,” says Dr. O’Kane, “but as I became an experienced physician – and patient – I saw the harm that such an attitude could cause. Patients on controlled medication long-term were often viewed as drug-seekers and treated as such, even if their regimen was largely regarded as appropriate. Likewise, those who could benefit from short-term controlled prescriptions were sometimes denied them because of their clinician’s fear.”

Today, Dr. O’Kane believes controlled medications should seldom be the first option for patients suffering pain, anxiety, or insomnia. But, she says, “they should remain on the table and without judgment for those who fail first-line treatment or for whom alternatives are contraindicated.”

Amy Baxter, MD, believes that the amount of time spent on pain education in school needs to change.

“Doctors in the U.S. get only 12 hours of pain education, and most of it is on pharmacology,” says Dr. Baxter, who graduated from med school in 1995. “In addition to incorrect information on home opioids and addiction, I was left with the impression that medication could treat chronic pain. I now have a completely different understanding of pain as a whole-brain warning system. The goal shouldn’t be pain-free, just more comfortable.”

Practice lifestyle and preventive medicine

Dolapo Babalola, MD, went to medical school eager to learn how to care for the human body and her family members’ illnesses, such as the debilitating effects of arthritic pain and other chronic diseases.

“I was taught the pathology behind arthritic pain, symptoms, signs, and treatment – that it has a genetic component and is inevitable to avoid – but nothing about how to prevent it,” says Dr. Babalola, a 2000 graduate.

Twenty years later, she discovered lifestyle medicine when she began to experience knee pain.

“I was introduced to the power of health restoration by discovering the root cause of diseases such as inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and insulin resistance due to poor lifestyle choices such as diet, inactivity, stress, inadequate sleep, and substance abuse,” she says.

Adebisi Alli, DO, who graduated in 2011, remembers being taught to treat type 2 diabetes by delaying progression rather than aiming for remission. But today, “lifestyle-led, team-based approaches are steadily becoming a first prescription across medical training with the goal to put diabetes in remission,” she says.

Patient care is at the core of medicine

Tracey O’Connell, MD, recalls her radiology residency in the early to mid-90s, when radiologists were integral to the health care team.

“We interacted with referrers and followed the course of patients’ diseases,” says Dr. O’Connell. “We knew patient histories, their stories. We were connected to other humans, doctors, nurses, teams, and the patients themselves.”

But with the advent of picture archiving and communication systems, high-speed CT and MRI, digital radiography, and voice recognition, the practice of radiology has changed dramatically.

“There’s no time to review or discuss cases anymore,” she says. “Reports went from eloquent and articulate documents with lists of differential diagnoses to short checklists and templates. The whole field of patient care has become dehumanizing, exactly the opposite of what humans need.”

Mache Seibel, MD, who graduated almost 50 years ago, agrees that patient care has lost its focus, to the detriment of patients.

“What I learned in medical school that is forgotten today is how to listen to patients, take a history, and do an examination using my hands and a stethoscope,” says Dr. Seibel. “Today with technology and time constraints, the focus is too much on the symptom without context, ordering a test, and getting the EMR boxes filled out.”

Physician, heal thyself

Priya Radhakrishnan, MD, remembers learning that a physician’s well-being was their responsibility. “We now know that well-being is the health system’s responsibility and that we need to diagnose ourselves and support each other, especially our trainees,” says Dr. Radhakrishna. She graduated in 1992. “Destigmatizing mental health is essential to well-being.”

Rachel Miller, MD, a 2009 med school graduate was taught that learning about health care systems and policy wasn’t necessary. Dr. Miller says they learned that policy knowledge would come in time. “I currently disagree. It is vital to understand aspects of health care systems and policy. Not knowing these things has partly contributed to the pervasiveness of burnout among physicians and other health care providers.”

Practice with gender at the forefront

Janice L. Werbinski, MD, an ob.gyn., and Elizabeth Anne Comen, MD, a breast cancer oncologist, remember when nearly all medical research was performed on the 140-lb White man. Doctors learned to treat patients through that male lens.

“The majority of the anatomy we saw in medical school was on a male figure,” says Dr. Comen, author of “All in Her Head,” a HarperCollins book slated to be released in February 2024. She graduated from med school in 2004. “The only time we saw anatomy for females was in the female reproductive system. That’s changing for the better.”

Dr. Werbinski chose a residency in obstetrics and gynecology in 1975 because she thought it was the only way she could serve female patients.

“I really thought that was the place for women’s health,” says Dr. Werbinski, cochair of the American Medical Women’s Association Sex & Gender Health Coalition.

“I am happy to say that significant awareness has grown since I graduated from medical school. I hope that when this question is asked of current medical students, they will be able to say that they know to practice with a sex- and gender-focused lens.”

Talk about racial disparities

John McHugh, MD, an ob.gyn., recalls learning little about the social determinants of health when he attended med school more than 30 years ago.

“We saw disparities in outcomes based on race and class but assumed that we would overcome them when we were in practice,” says Dr. McHugh, an AMWA Action Coalition for Equity member. “We didn’t understand the root causes of disparities and had never heard of concepts like epigenetics or weathering. I’m hopeful current research will help our understanding and today’s medical students will serve a safer, healthier, and more equitable world.”

Curtiland Deville, MD, an associate professor of radiation oncology, recalls having few conversations around race; racial disparities; and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“When I went to medical school, it often felt like you weren’t supposed to talk about the differences in race,” says Dr. Deville, who graduated in 2005. But today, in the post-2020 era between COVID, during which health disparities got highlighted, and calls for racial justice taking center stage, Dr. Deville says many of the things they didn’t talk about have come to the forefront in our medical institutions.

Information at your fingertips

For Paru David, MD, a 1996 graduate, the most significant change is the amount of health and medical information available today. “Before, the information that was taught in medical school was obtained through textbooks or within journal articles,” says Dr. David.

“Now, we have databases of information. The key to success is being able to navigate the information available to us, digest it with a keen eye, and then apply it to patient care in a timely manner.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical education has changed drastically over the years. As theories and practices continue to change, what was once standard 10 or 20 years ago has been replaced with newer ideologies, processes, or technology. It seems likely, then, that you may disagree with some of the things that you learned as medical school has evolved.

Many of their answers include newer philosophies and practice methods.

Treat appropriately for pain

Jacqui O’Kane, DO, a 2013 med school graduate, was taught to avoid prescribing controlled medications whenever possible.

“Initially this attitude made sense to me,” says Dr. O’Kane, “but as I became an experienced physician – and patient – I saw the harm that such an attitude could cause. Patients on controlled medication long-term were often viewed as drug-seekers and treated as such, even if their regimen was largely regarded as appropriate. Likewise, those who could benefit from short-term controlled prescriptions were sometimes denied them because of their clinician’s fear.”

Today, Dr. O’Kane believes controlled medications should seldom be the first option for patients suffering pain, anxiety, or insomnia. But, she says, “they should remain on the table and without judgment for those who fail first-line treatment or for whom alternatives are contraindicated.”

Amy Baxter, MD, believes that the amount of time spent on pain education in school needs to change.

“Doctors in the U.S. get only 12 hours of pain education, and most of it is on pharmacology,” says Dr. Baxter, who graduated from med school in 1995. “In addition to incorrect information on home opioids and addiction, I was left with the impression that medication could treat chronic pain. I now have a completely different understanding of pain as a whole-brain warning system. The goal shouldn’t be pain-free, just more comfortable.”

Practice lifestyle and preventive medicine

Dolapo Babalola, MD, went to medical school eager to learn how to care for the human body and her family members’ illnesses, such as the debilitating effects of arthritic pain and other chronic diseases.

“I was taught the pathology behind arthritic pain, symptoms, signs, and treatment – that it has a genetic component and is inevitable to avoid – but nothing about how to prevent it,” says Dr. Babalola, a 2000 graduate.

Twenty years later, she discovered lifestyle medicine when she began to experience knee pain.

“I was introduced to the power of health restoration by discovering the root cause of diseases such as inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and insulin resistance due to poor lifestyle choices such as diet, inactivity, stress, inadequate sleep, and substance abuse,” she says.

Adebisi Alli, DO, who graduated in 2011, remembers being taught to treat type 2 diabetes by delaying progression rather than aiming for remission. But today, “lifestyle-led, team-based approaches are steadily becoming a first prescription across medical training with the goal to put diabetes in remission,” she says.

Patient care is at the core of medicine

Tracey O’Connell, MD, recalls her radiology residency in the early to mid-90s, when radiologists were integral to the health care team.

“We interacted with referrers and followed the course of patients’ diseases,” says Dr. O’Connell. “We knew patient histories, their stories. We were connected to other humans, doctors, nurses, teams, and the patients themselves.”

But with the advent of picture archiving and communication systems, high-speed CT and MRI, digital radiography, and voice recognition, the practice of radiology has changed dramatically.

“There’s no time to review or discuss cases anymore,” she says. “Reports went from eloquent and articulate documents with lists of differential diagnoses to short checklists and templates. The whole field of patient care has become dehumanizing, exactly the opposite of what humans need.”

Mache Seibel, MD, who graduated almost 50 years ago, agrees that patient care has lost its focus, to the detriment of patients.

“What I learned in medical school that is forgotten today is how to listen to patients, take a history, and do an examination using my hands and a stethoscope,” says Dr. Seibel. “Today with technology and time constraints, the focus is too much on the symptom without context, ordering a test, and getting the EMR boxes filled out.”

Physician, heal thyself

Priya Radhakrishnan, MD, remembers learning that a physician’s well-being was their responsibility. “We now know that well-being is the health system’s responsibility and that we need to diagnose ourselves and support each other, especially our trainees,” says Dr. Radhakrishna. She graduated in 1992. “Destigmatizing mental health is essential to well-being.”

Rachel Miller, MD, a 2009 med school graduate was taught that learning about health care systems and policy wasn’t necessary. Dr. Miller says they learned that policy knowledge would come in time. “I currently disagree. It is vital to understand aspects of health care systems and policy. Not knowing these things has partly contributed to the pervasiveness of burnout among physicians and other health care providers.”

Practice with gender at the forefront

Janice L. Werbinski, MD, an ob.gyn., and Elizabeth Anne Comen, MD, a breast cancer oncologist, remember when nearly all medical research was performed on the 140-lb White man. Doctors learned to treat patients through that male lens.

“The majority of the anatomy we saw in medical school was on a male figure,” says Dr. Comen, author of “All in Her Head,” a HarperCollins book slated to be released in February 2024. She graduated from med school in 2004. “The only time we saw anatomy for females was in the female reproductive system. That’s changing for the better.”

Dr. Werbinski chose a residency in obstetrics and gynecology in 1975 because she thought it was the only way she could serve female patients.

“I really thought that was the place for women’s health,” says Dr. Werbinski, cochair of the American Medical Women’s Association Sex & Gender Health Coalition.

“I am happy to say that significant awareness has grown since I graduated from medical school. I hope that when this question is asked of current medical students, they will be able to say that they know to practice with a sex- and gender-focused lens.”

Talk about racial disparities

John McHugh, MD, an ob.gyn., recalls learning little about the social determinants of health when he attended med school more than 30 years ago.

“We saw disparities in outcomes based on race and class but assumed that we would overcome them when we were in practice,” says Dr. McHugh, an AMWA Action Coalition for Equity member. “We didn’t understand the root causes of disparities and had never heard of concepts like epigenetics or weathering. I’m hopeful current research will help our understanding and today’s medical students will serve a safer, healthier, and more equitable world.”

Curtiland Deville, MD, an associate professor of radiation oncology, recalls having few conversations around race; racial disparities; and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“When I went to medical school, it often felt like you weren’t supposed to talk about the differences in race,” says Dr. Deville, who graduated in 2005. But today, in the post-2020 era between COVID, during which health disparities got highlighted, and calls for racial justice taking center stage, Dr. Deville says many of the things they didn’t talk about have come to the forefront in our medical institutions.

Information at your fingertips

For Paru David, MD, a 1996 graduate, the most significant change is the amount of health and medical information available today. “Before, the information that was taught in medical school was obtained through textbooks or within journal articles,” says Dr. David.

“Now, we have databases of information. The key to success is being able to navigate the information available to us, digest it with a keen eye, and then apply it to patient care in a timely manner.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical education has changed drastically over the years. As theories and practices continue to change, what was once standard 10 or 20 years ago has been replaced with newer ideologies, processes, or technology. It seems likely, then, that you may disagree with some of the things that you learned as medical school has evolved.

Many of their answers include newer philosophies and practice methods.

Treat appropriately for pain

Jacqui O’Kane, DO, a 2013 med school graduate, was taught to avoid prescribing controlled medications whenever possible.

“Initially this attitude made sense to me,” says Dr. O’Kane, “but as I became an experienced physician – and patient – I saw the harm that such an attitude could cause. Patients on controlled medication long-term were often viewed as drug-seekers and treated as such, even if their regimen was largely regarded as appropriate. Likewise, those who could benefit from short-term controlled prescriptions were sometimes denied them because of their clinician’s fear.”

Today, Dr. O’Kane believes controlled medications should seldom be the first option for patients suffering pain, anxiety, or insomnia. But, she says, “they should remain on the table and without judgment for those who fail first-line treatment or for whom alternatives are contraindicated.”

Amy Baxter, MD, believes that the amount of time spent on pain education in school needs to change.

“Doctors in the U.S. get only 12 hours of pain education, and most of it is on pharmacology,” says Dr. Baxter, who graduated from med school in 1995. “In addition to incorrect information on home opioids and addiction, I was left with the impression that medication could treat chronic pain. I now have a completely different understanding of pain as a whole-brain warning system. The goal shouldn’t be pain-free, just more comfortable.”

Practice lifestyle and preventive medicine

Dolapo Babalola, MD, went to medical school eager to learn how to care for the human body and her family members’ illnesses, such as the debilitating effects of arthritic pain and other chronic diseases.

“I was taught the pathology behind arthritic pain, symptoms, signs, and treatment – that it has a genetic component and is inevitable to avoid – but nothing about how to prevent it,” says Dr. Babalola, a 2000 graduate.

Twenty years later, she discovered lifestyle medicine when she began to experience knee pain.

“I was introduced to the power of health restoration by discovering the root cause of diseases such as inflammation, hormonal imbalance, and insulin resistance due to poor lifestyle choices such as diet, inactivity, stress, inadequate sleep, and substance abuse,” she says.

Adebisi Alli, DO, who graduated in 2011, remembers being taught to treat type 2 diabetes by delaying progression rather than aiming for remission. But today, “lifestyle-led, team-based approaches are steadily becoming a first prescription across medical training with the goal to put diabetes in remission,” she says.

Patient care is at the core of medicine

Tracey O’Connell, MD, recalls her radiology residency in the early to mid-90s, when radiologists were integral to the health care team.

“We interacted with referrers and followed the course of patients’ diseases,” says Dr. O’Connell. “We knew patient histories, their stories. We were connected to other humans, doctors, nurses, teams, and the patients themselves.”

But with the advent of picture archiving and communication systems, high-speed CT and MRI, digital radiography, and voice recognition, the practice of radiology has changed dramatically.

“There’s no time to review or discuss cases anymore,” she says. “Reports went from eloquent and articulate documents with lists of differential diagnoses to short checklists and templates. The whole field of patient care has become dehumanizing, exactly the opposite of what humans need.”

Mache Seibel, MD, who graduated almost 50 years ago, agrees that patient care has lost its focus, to the detriment of patients.

“What I learned in medical school that is forgotten today is how to listen to patients, take a history, and do an examination using my hands and a stethoscope,” says Dr. Seibel. “Today with technology and time constraints, the focus is too much on the symptom without context, ordering a test, and getting the EMR boxes filled out.”

Physician, heal thyself

Priya Radhakrishnan, MD, remembers learning that a physician’s well-being was their responsibility. “We now know that well-being is the health system’s responsibility and that we need to diagnose ourselves and support each other, especially our trainees,” says Dr. Radhakrishna. She graduated in 1992. “Destigmatizing mental health is essential to well-being.”

Rachel Miller, MD, a 2009 med school graduate was taught that learning about health care systems and policy wasn’t necessary. Dr. Miller says they learned that policy knowledge would come in time. “I currently disagree. It is vital to understand aspects of health care systems and policy. Not knowing these things has partly contributed to the pervasiveness of burnout among physicians and other health care providers.”

Practice with gender at the forefront

Janice L. Werbinski, MD, an ob.gyn., and Elizabeth Anne Comen, MD, a breast cancer oncologist, remember when nearly all medical research was performed on the 140-lb White man. Doctors learned to treat patients through that male lens.

“The majority of the anatomy we saw in medical school was on a male figure,” says Dr. Comen, author of “All in Her Head,” a HarperCollins book slated to be released in February 2024. She graduated from med school in 2004. “The only time we saw anatomy for females was in the female reproductive system. That’s changing for the better.”

Dr. Werbinski chose a residency in obstetrics and gynecology in 1975 because she thought it was the only way she could serve female patients.

“I really thought that was the place for women’s health,” says Dr. Werbinski, cochair of the American Medical Women’s Association Sex & Gender Health Coalition.

“I am happy to say that significant awareness has grown since I graduated from medical school. I hope that when this question is asked of current medical students, they will be able to say that they know to practice with a sex- and gender-focused lens.”

Talk about racial disparities

John McHugh, MD, an ob.gyn., recalls learning little about the social determinants of health when he attended med school more than 30 years ago.

“We saw disparities in outcomes based on race and class but assumed that we would overcome them when we were in practice,” says Dr. McHugh, an AMWA Action Coalition for Equity member. “We didn’t understand the root causes of disparities and had never heard of concepts like epigenetics or weathering. I’m hopeful current research will help our understanding and today’s medical students will serve a safer, healthier, and more equitable world.”

Curtiland Deville, MD, an associate professor of radiation oncology, recalls having few conversations around race; racial disparities; and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“When I went to medical school, it often felt like you weren’t supposed to talk about the differences in race,” says Dr. Deville, who graduated in 2005. But today, in the post-2020 era between COVID, during which health disparities got highlighted, and calls for racial justice taking center stage, Dr. Deville says many of the things they didn’t talk about have come to the forefront in our medical institutions.

Information at your fingertips

For Paru David, MD, a 1996 graduate, the most significant change is the amount of health and medical information available today. “Before, the information that was taught in medical school was obtained through textbooks or within journal articles,” says Dr. David.

“Now, we have databases of information. The key to success is being able to navigate the information available to us, digest it with a keen eye, and then apply it to patient care in a timely manner.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Noteworthy advances in treatment and management of IBD

Although it had been thought that incidence rates of IBD were plateauing in high-incidence areas, a Danish study found a steady increase in incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).1 The highest increase in rates occurred in children and young adults, which will have repercussions as people get older and contribute to higher compounding prevalence. We need to get better at dealing with other health conditions as patients get older. A very large prospective Spanish study found that 42% of IBD patients scanned consecutively had MAFLD (metabolic-associated fatty liver disease) – even if they didn’t have high BMI and type 2 diabetes, suggesting that systemic inflammation in IBD contributes to the development of metabolic liver disease.2

The AGA has recently published guidelines for using biomarkers in the management of UC. Patients with very low fecal calprotectin (FCP) are unlikely to have active disease whereas FCP over 150 with significant symptoms may warrant empiric changes in treatment.3

Intestinal ultrasound is gaining wider acceptance as a noninvasive way to monitor IBD.4 In a UC study, improvement in bowel wall thickness following tofacitinib treatment correlated well with endoscopic activity.5

The majority of the presentation focused on the explosion of Food and Drug Administration–-approved medications for IBD in recent years. S1P receptor agonists, such as ozanimod and etrasimod, may work by trapping specific T-cell subsets in peripheral lymph nodes, preventing migration to intestinal tissues. Ozanimod is approved for UC. Etrasimod showed efficacy in UC with clinical remission rates of about 27% at week 12 and 32% at week 52.6,7

There has been a lot of excitement about JAK inhibitors for IBD. Upadacitinib has recently been approved for both UC and Crohn’s disease. Response rates of 73% and remission rates of 26% were seen in UC patients who had been largely biologic exposed.8 Similar results were seen in a biologic-exposed Crohn’s disease population treated with upadacitinib including in endoscopy.9 Upadacitinib was effective in maintaining remission at both 15-mg and 30-mg doses; but the higher dose had a greater effect on endoscopic endpoints.10

For Crohn’s disease, we now have risankizumab, an anti-p19/IL-23 inhibitor. Risankizumab was efficacious at inducing and maintain remission in the pivotal phase 3 studies, even with 75% of patients being biologic exposed. These studies used combined endpoints of clinical remission as well as endoscopic response.11 Guselkumab (anti-p19/IL-23) is also being studied for Crohn’s disease and early trials has appears to be efficacious.12

A head-to-head study of naive CD patients treated with ustekinumab or adalimumab (SEAVUE) showed comparable rates of clinical remission. At 52 weeks, the rates of clinical remission were quite high: >60% and endoscopic remission >30% with either therapy.13

We now have phase 3 data showing that a biologic is efficacious in patients with chronic pouchitis. The EARNEST trial demonstrated that vedolizumab has efficacy in treating pouchitis with improved clinical symptoms and endoscopy.14 Future treatment strategies may involve combinations of biologic therapies. The VEGA study showed that combining an anti-TNF, golimumab, with an anti-IL23, guselkumab, was superior than either alone with respect to clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in UC.15 We will see more studies combining therapies with diverse mechanisms of action.

In summary, there have been many noteworthy advances in treatment and management of IBD in the past year.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Dr. Abreu is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and professor of medicine, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Miami. She is president-elect of AGA. Dr. Allegretti is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and director of the fecal microbiota transplant program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Loftus is the Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Professor of Gastroenterology, codirector of the advanced IBD fellowship in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Ungaro is associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Agrawal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1547-54.e5.

2. Rodriguez-Duque JC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(2):406-14.e7.

3. Singh S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(3):344-72.

4. de Voogd F et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1569-81.

5. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1723-36.

6. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280-91.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. Lancet. 2023 Mar 25;401(10381):1000]. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1159-71.

8. Danese S et al. Lancet. 2022 Sep 24;400(10357):996]. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2113-28.

9. Loftus EV Jr et al. N Engl J Med. 2023 May 25;388(21):1966-80.

10. Panes J et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117(S10). Abstract S37.

11. D’Haens G, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-30

12. Sandborn WJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1650-64.e8.

13. Sands BE, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10342):2200-11.

14. Travis S et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(13):1191-1200.

15. Feagan BG et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):307-20.

Although it had been thought that incidence rates of IBD were plateauing in high-incidence areas, a Danish study found a steady increase in incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).1 The highest increase in rates occurred in children and young adults, which will have repercussions as people get older and contribute to higher compounding prevalence. We need to get better at dealing with other health conditions as patients get older. A very large prospective Spanish study found that 42% of IBD patients scanned consecutively had MAFLD (metabolic-associated fatty liver disease) – even if they didn’t have high BMI and type 2 diabetes, suggesting that systemic inflammation in IBD contributes to the development of metabolic liver disease.2

The AGA has recently published guidelines for using biomarkers in the management of UC. Patients with very low fecal calprotectin (FCP) are unlikely to have active disease whereas FCP over 150 with significant symptoms may warrant empiric changes in treatment.3

Intestinal ultrasound is gaining wider acceptance as a noninvasive way to monitor IBD.4 In a UC study, improvement in bowel wall thickness following tofacitinib treatment correlated well with endoscopic activity.5

The majority of the presentation focused on the explosion of Food and Drug Administration–-approved medications for IBD in recent years. S1P receptor agonists, such as ozanimod and etrasimod, may work by trapping specific T-cell subsets in peripheral lymph nodes, preventing migration to intestinal tissues. Ozanimod is approved for UC. Etrasimod showed efficacy in UC with clinical remission rates of about 27% at week 12 and 32% at week 52.6,7

There has been a lot of excitement about JAK inhibitors for IBD. Upadacitinib has recently been approved for both UC and Crohn’s disease. Response rates of 73% and remission rates of 26% were seen in UC patients who had been largely biologic exposed.8 Similar results were seen in a biologic-exposed Crohn’s disease population treated with upadacitinib including in endoscopy.9 Upadacitinib was effective in maintaining remission at both 15-mg and 30-mg doses; but the higher dose had a greater effect on endoscopic endpoints.10

For Crohn’s disease, we now have risankizumab, an anti-p19/IL-23 inhibitor. Risankizumab was efficacious at inducing and maintain remission in the pivotal phase 3 studies, even with 75% of patients being biologic exposed. These studies used combined endpoints of clinical remission as well as endoscopic response.11 Guselkumab (anti-p19/IL-23) is also being studied for Crohn’s disease and early trials has appears to be efficacious.12

A head-to-head study of naive CD patients treated with ustekinumab or adalimumab (SEAVUE) showed comparable rates of clinical remission. At 52 weeks, the rates of clinical remission were quite high: >60% and endoscopic remission >30% with either therapy.13

We now have phase 3 data showing that a biologic is efficacious in patients with chronic pouchitis. The EARNEST trial demonstrated that vedolizumab has efficacy in treating pouchitis with improved clinical symptoms and endoscopy.14 Future treatment strategies may involve combinations of biologic therapies. The VEGA study showed that combining an anti-TNF, golimumab, with an anti-IL23, guselkumab, was superior than either alone with respect to clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in UC.15 We will see more studies combining therapies with diverse mechanisms of action.

In summary, there have been many noteworthy advances in treatment and management of IBD in the past year.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Dr. Abreu is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and professor of medicine, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Miami. She is president-elect of AGA. Dr. Allegretti is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and director of the fecal microbiota transplant program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Loftus is the Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Professor of Gastroenterology, codirector of the advanced IBD fellowship in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Ungaro is associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Agrawal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1547-54.e5.

2. Rodriguez-Duque JC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(2):406-14.e7.

3. Singh S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(3):344-72.

4. de Voogd F et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1569-81.

5. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1723-36.

6. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280-91.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. Lancet. 2023 Mar 25;401(10381):1000]. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1159-71.

8. Danese S et al. Lancet. 2022 Sep 24;400(10357):996]. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2113-28.

9. Loftus EV Jr et al. N Engl J Med. 2023 May 25;388(21):1966-80.

10. Panes J et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117(S10). Abstract S37.

11. D’Haens G, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-30

12. Sandborn WJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1650-64.e8.

13. Sands BE, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10342):2200-11.

14. Travis S et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(13):1191-1200.

15. Feagan BG et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):307-20.

Although it had been thought that incidence rates of IBD were plateauing in high-incidence areas, a Danish study found a steady increase in incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (UC).1 The highest increase in rates occurred in children and young adults, which will have repercussions as people get older and contribute to higher compounding prevalence. We need to get better at dealing with other health conditions as patients get older. A very large prospective Spanish study found that 42% of IBD patients scanned consecutively had MAFLD (metabolic-associated fatty liver disease) – even if they didn’t have high BMI and type 2 diabetes, suggesting that systemic inflammation in IBD contributes to the development of metabolic liver disease.2

The AGA has recently published guidelines for using biomarkers in the management of UC. Patients with very low fecal calprotectin (FCP) are unlikely to have active disease whereas FCP over 150 with significant symptoms may warrant empiric changes in treatment.3

Intestinal ultrasound is gaining wider acceptance as a noninvasive way to monitor IBD.4 In a UC study, improvement in bowel wall thickness following tofacitinib treatment correlated well with endoscopic activity.5

The majority of the presentation focused on the explosion of Food and Drug Administration–-approved medications for IBD in recent years. S1P receptor agonists, such as ozanimod and etrasimod, may work by trapping specific T-cell subsets in peripheral lymph nodes, preventing migration to intestinal tissues. Ozanimod is approved for UC. Etrasimod showed efficacy in UC with clinical remission rates of about 27% at week 12 and 32% at week 52.6,7

There has been a lot of excitement about JAK inhibitors for IBD. Upadacitinib has recently been approved for both UC and Crohn’s disease. Response rates of 73% and remission rates of 26% were seen in UC patients who had been largely biologic exposed.8 Similar results were seen in a biologic-exposed Crohn’s disease population treated with upadacitinib including in endoscopy.9 Upadacitinib was effective in maintaining remission at both 15-mg and 30-mg doses; but the higher dose had a greater effect on endoscopic endpoints.10

For Crohn’s disease, we now have risankizumab, an anti-p19/IL-23 inhibitor. Risankizumab was efficacious at inducing and maintain remission in the pivotal phase 3 studies, even with 75% of patients being biologic exposed. These studies used combined endpoints of clinical remission as well as endoscopic response.11 Guselkumab (anti-p19/IL-23) is also being studied for Crohn’s disease and early trials has appears to be efficacious.12

A head-to-head study of naive CD patients treated with ustekinumab or adalimumab (SEAVUE) showed comparable rates of clinical remission. At 52 weeks, the rates of clinical remission were quite high: >60% and endoscopic remission >30% with either therapy.13

We now have phase 3 data showing that a biologic is efficacious in patients with chronic pouchitis. The EARNEST trial demonstrated that vedolizumab has efficacy in treating pouchitis with improved clinical symptoms and endoscopy.14 Future treatment strategies may involve combinations of biologic therapies. The VEGA study showed that combining an anti-TNF, golimumab, with an anti-IL23, guselkumab, was superior than either alone with respect to clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in UC.15 We will see more studies combining therapies with diverse mechanisms of action.

In summary, there have been many noteworthy advances in treatment and management of IBD in the past year.

DDW is sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Dr. Abreu is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and professor of medicine, microbiology, and immunology at the University of Miami. She is president-elect of AGA. Dr. Allegretti is director of the Crohn’s and Colitis Center and director of the fecal microbiota transplant program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. She is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Loftus is the Maxine and Jack Zarrow Family Professor of Gastroenterology, codirector of the advanced IBD fellowship in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Ungaro is associate professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

References

1. Agrawal M et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1547-54.e5.

2. Rodriguez-Duque JC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(2):406-14.e7.

3. Singh S, et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164(3):344-72.

4. de Voogd F et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1569-81.

5. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(18):1723-36.

6. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(14):1280-91.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. Lancet. 2023 Mar 25;401(10381):1000]. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1159-71.

8. Danese S et al. Lancet. 2022 Sep 24;400(10357):996]. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2113-28.

9. Loftus EV Jr et al. N Engl J Med. 2023 May 25;388(21):1966-80.

10. Panes J et al. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117(S10). Abstract S37.

11. D’Haens G, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015-30

12. Sandborn WJ et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(6):1650-64.e8.

13. Sands BE, et al. Lancet. 2022;399(10342):2200-11.

14. Travis S et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(13):1191-1200.

15. Feagan BG et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):307-20.

AT DDW 2023

Managing intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

CASE Pregnant woman with intense itching

A 28-year-old woman (G1P0) is seen for a routine prenatal visit at 32 3/7 weeks’ gestation. She reports having generalized intense itching, including on her palms and soles, that is most intense at night and has been present for approximately 1 week. Her pregnancy is otherwise uncomplicated to date. Physical exam is within normal limits, with no evidence of a skin rash. Cholestasis of pregnancy is suspected, and laboratory tests are ordered, including bile acids and liver transaminases. Test results show that her aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels are mildly elevated at 55 IU/L and 41 IU/L, respectively, and several days later her bile acid level result is 21 µmol/L.

How should this patient be managed?

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) affects 0.5% to 0.7% of pregnant individuals and results in maternal pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels.1-3 Pruritus in ICP typically is generalized, including occurrence on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and it often is reported to be worse at night.4 Up to 25% of pregnant women will develop pruritus during pregnancy but the majority will not have ICP.2,5 Patients with ICP have no associated rash, but clinicians may note excoriations on exam. ICP typically presents in the third trimester of pregnancy but has been reported to occur earlier in gestation.6

Making a diagnosis of ICP

The presence of maternal pruritus in the absence of a skin condition along with elevated levels of serum bile acids are required for the diagnosis of ICP.7 Thus, a thorough history and physical exam is recommended to rule out another skin condition that could potentially explain the patient’s pruritus.

Some controversy exists regarding the bile acid level cutoff that should be used to make a diagnosis of ICP.8 It has been noted that nonfasting serum bile acid levels in pregnancy are considerably higher than those in in the nonpregnant state, and an upper limit of 18 µmol/L has been proposed as a cutoff in pregnancy.9 However, nonfasting total serum bile acids also have been shown to vary considerably by race, with levels 25.8% higher in Black women compared with those in White women and 24.3% higher in Black women compared with those in south Asian women.9 This raises the question of whether we should be using race-specific bile acid values to make a diagnosis of ICP.

Bile acid levels also vary based on whether a patient is in a fasting or postprandial state.10 Despite this variation, most guidelines do not recommend testing fasting bile acid levels as the postprandial state effect overall is small.7,9,11 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) recommends that if a pregnancy-specific bile acid range is available from the laboratory, then the upper limit of normal for pregnancy should be used when making a diagnosis of ICP.7 The SMFM guidelines also acknowledge, however, that pregnancy-specific values rarely are available, and in this case, levels above the upper limit of normal—often 10 µmol/L should be considered diagnostic for ICP until further evidence regarding optimal bile acid cutoff levels in pregnancy becomes available.7

For patients with suspected ICP, liver transaminase levels should be measured in addition to nonfasting serum bile acid levels.7 A thorough history should include assessment for additional symptoms of liver disease, such as changes in weight, appetite, jaundice, excessive fatigue, malaise, and abdominal pain.7 Elevated transaminases levels may be associated with ICP, but they are not necessary for diagnosis. In the absence of additional clinical symptoms that suggest underlying liver disease or severe early onset ICP, additional evaluation beyond nonfasting serum bile acids and liver transaminase levels, such as liver ultrasonography or evaluation for viral or autoimmune hepatitis, is not recommended.7 Obstetric care clinicians should be aware that there is an increased incidence of preeclampsia among patients with ICP, although no specific guidance regarding further recommendations for screening is provided.7

Continue to: Risks associated with ICP...

Risks associated with ICP

For both patients and clinicians, the greatest concern among patients with ICP is the increased risk of stillbirth. Stillbirth risk in ICP appears to be related to serum bile acid levels and has been reported to be highest in patients with bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ICP studies demonstrated no increased risk of stillbirth among patients with bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L.12 These results, however, must be interpreted with extreme caution as the majority of studies included patients with ICP who were actively managed with attempts to mitigate the risk of stillbirth.7

In the absence of additional pregnancy risk factors, the risk of stillbirth among patients with ICP and serum bile acid levels between 19 and 39 µmol/L does not appear to be elevated above their baseline risk.11 The same is true for pregnant individuals with ICP and no additional pregnancy risk factors with serum bile acid levels between 40 and 99 µmol/L until approximately 38 weeks’ gestation, when the risk of stillbirth is elevated.11 The risk of stillbirth is elevated in ICP with peak bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L, with an absolute risk of 3.44%.11

Management of patients with ICP

Laboratory evaluation

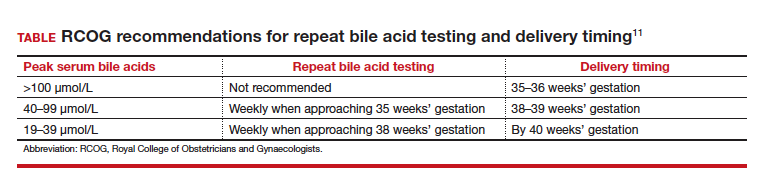

There is no consensus on the need for repeat testing of bile acid levels in patients with ICP. SMFM advises that follow-up testing of bile acid levels may help to guide delivery timing, especially in cases of severe ICP, but the society recommends against serial testing.7 By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) provides a detailed algorithm regarding time intervals between serum bile acid level testing to guide delivery timing.11 The TABLE lists the strategy for reassessment of serum bile acid levels in ICP as recommended by the RCOG.11

In the United States, bile acid testing traditionally takes several days as the testing is commonly performed at reference laboratories. We therefore suggest that clinicians consider repeating bile acid level testing in situations in which the timing of delivery may be altered if further elevations of bile acid levels were noted. This is particularly relevant for patients diagnosed with ICP early in the third trimester when repeat bile acid levels would still allow for an adjustment in delivery timing.

Antepartum fetal surveillance

Unfortunately, antepartum fetal testing for pregnant patients with ICP does not appear to reliably predict or prevent stillbirth as several studies have reported stillbirths within days of normal fetal testing.13-16 It is therefore important to counsel pregnant patients regarding monitoring of fetal movements and advise them to present for evaluation if concerns arise.

Currently, SMFM recommends that patients with ICP should begin antenatal fetal surveillance at a gestational age when abnormal fetal testing would result in delivery.7 Patients should be counseled, however, regarding the unpredictability of stillbirth with ICP in the setting of a low absolute risk of such.

Medications

While SMFM recommends a starting dose of ursodeoxycholic acid 10 to 15 mg/kg per day divided into 2 or 3 daily doses as first-line therapy for the treatment of maternal symptoms of ICP, it is important to acknowledge that the goal of treatment is to alleviate maternal symptoms as there is no evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid improves either maternal serum bile acid levels or perinatal outcomes.7,17,18 Since publication of the guidelines, ursodeoxycholic acid’s lack of benefit has been further confirmed in a meta-analysis, and thus discontinuation is not unreasonable in the absence of any improvement in maternal symptoms.18

Timing of delivery

The optimal management of ICP remains unknown. SMFM recommends delivery based on peak serum bile acid levels. Delivery is recommended at 36 weeks’ gestation with ICP and total bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L as these patients have the greatest risk of stillbirth.7 For patients with ICP and bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L, delivery is recommended between 36 0/7 and 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation.7 This is a wide gestational age window for clinicians to consider timing of delivery, and certainly the risks of stillbirth should be carefully balanced with the morbidity associated with a preterm or early term delivery.

For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels greater than 40 µmol/L, it is reasonable to consider delivery earlier in the gestational age window, given an evidence of increased risk of stillbirth after 38 weeks.7,12 For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels less than 40 µmol/L, delivery closer to 39 weeks’ gestation is recommended, as the risk of stillbirth does not appear to be increased above the baseline risk.7,12 Clinicians should be aware that the presence of concomitant morbidities, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and should be considered for delivery planning.19

Postpartum follow-up

Routine laboratory evaluation following delivery is not recommended.7 However, in the presence of persistent pruritus or other signs and symptoms of hepatobiliary disease, liver function tests should be repeated with referral to hepatology if results are persistently abnormal 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.7

CASE Patient follow-up and outcomes

- Abedin P, Weaver JB, Egginton E. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: prevalence and ethnic distribution. Ethn Health. 1999;4:35-37.

- Kenyon AP, Tribe RM, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Pruritus in pregnancy: a study of anatomical distribution and prevalence in relation to the development of obstetric cholestasis. Obstet Med. 2010;3:25-29.

- Wikstrom Shemer E, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: a 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:717-723.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM, Glatz M, Trauner M, et al. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a case series from central Europe. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:757-762.

- Szczech J, Wiatrowski A, Hirnle L, et al. Prevalence and relevance of pruritus in pregnancy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4238139.

- Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2049-2066.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Lee RH, Greenberg M, Metz TD, et al. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #53: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: replaces Consult #13, April 2011. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:B2-B9.

- Horgan R, Bitas C, Abuhamad A. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a comparison of Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:100838.

- Mitchell AL, Ovadia C, Syngelaki A, et al. Re-evaluating diagnostic thresholds for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: case-control and cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1635-1644.

- Adams A, Jacobs K, Vogel RI, et al. Bile acid determination after standardized glucose load in pregnant women. AJP Rep. 2015;5:e168-e171.

- Girling J, Knight CL, Chappell L; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Green-top guideline no. 43, June 2022. BJOG. 2022;129:e95-e114.

- Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393:899-909.

- Alsulyman OM, Ouzounian JG, Ames-Castro M, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: perinatal outcome associated with expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:957-960.

- Herrera CA, Manuck TA, Stoddard GJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1913-1920.

- Lee RH, Incerpi MH, Miller DA, et al. Sudden fetal death in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:528-531.

- Sentilhes L, Verspyck E, Pia P, et al. Fetal death in a patient with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:458-460.

- Chappell LC, Bell JL, Smith A, et al; PITCHES Study Group. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:849-860.

- Ovadia C, Sajous J, Seed PT, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:547-558.

- Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482-1491.

CASE Pregnant woman with intense itching

A 28-year-old woman (G1P0) is seen for a routine prenatal visit at 32 3/7 weeks’ gestation. She reports having generalized intense itching, including on her palms and soles, that is most intense at night and has been present for approximately 1 week. Her pregnancy is otherwise uncomplicated to date. Physical exam is within normal limits, with no evidence of a skin rash. Cholestasis of pregnancy is suspected, and laboratory tests are ordered, including bile acids and liver transaminases. Test results show that her aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels are mildly elevated at 55 IU/L and 41 IU/L, respectively, and several days later her bile acid level result is 21 µmol/L.

How should this patient be managed?

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) affects 0.5% to 0.7% of pregnant individuals and results in maternal pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels.1-3 Pruritus in ICP typically is generalized, including occurrence on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and it often is reported to be worse at night.4 Up to 25% of pregnant women will develop pruritus during pregnancy but the majority will not have ICP.2,5 Patients with ICP have no associated rash, but clinicians may note excoriations on exam. ICP typically presents in the third trimester of pregnancy but has been reported to occur earlier in gestation.6

Making a diagnosis of ICP

The presence of maternal pruritus in the absence of a skin condition along with elevated levels of serum bile acids are required for the diagnosis of ICP.7 Thus, a thorough history and physical exam is recommended to rule out another skin condition that could potentially explain the patient’s pruritus.

Some controversy exists regarding the bile acid level cutoff that should be used to make a diagnosis of ICP.8 It has been noted that nonfasting serum bile acid levels in pregnancy are considerably higher than those in in the nonpregnant state, and an upper limit of 18 µmol/L has been proposed as a cutoff in pregnancy.9 However, nonfasting total serum bile acids also have been shown to vary considerably by race, with levels 25.8% higher in Black women compared with those in White women and 24.3% higher in Black women compared with those in south Asian women.9 This raises the question of whether we should be using race-specific bile acid values to make a diagnosis of ICP.

Bile acid levels also vary based on whether a patient is in a fasting or postprandial state.10 Despite this variation, most guidelines do not recommend testing fasting bile acid levels as the postprandial state effect overall is small.7,9,11 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) recommends that if a pregnancy-specific bile acid range is available from the laboratory, then the upper limit of normal for pregnancy should be used when making a diagnosis of ICP.7 The SMFM guidelines also acknowledge, however, that pregnancy-specific values rarely are available, and in this case, levels above the upper limit of normal—often 10 µmol/L should be considered diagnostic for ICP until further evidence regarding optimal bile acid cutoff levels in pregnancy becomes available.7

For patients with suspected ICP, liver transaminase levels should be measured in addition to nonfasting serum bile acid levels.7 A thorough history should include assessment for additional symptoms of liver disease, such as changes in weight, appetite, jaundice, excessive fatigue, malaise, and abdominal pain.7 Elevated transaminases levels may be associated with ICP, but they are not necessary for diagnosis. In the absence of additional clinical symptoms that suggest underlying liver disease or severe early onset ICP, additional evaluation beyond nonfasting serum bile acids and liver transaminase levels, such as liver ultrasonography or evaluation for viral or autoimmune hepatitis, is not recommended.7 Obstetric care clinicians should be aware that there is an increased incidence of preeclampsia among patients with ICP, although no specific guidance regarding further recommendations for screening is provided.7

Continue to: Risks associated with ICP...

Risks associated with ICP

For both patients and clinicians, the greatest concern among patients with ICP is the increased risk of stillbirth. Stillbirth risk in ICP appears to be related to serum bile acid levels and has been reported to be highest in patients with bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ICP studies demonstrated no increased risk of stillbirth among patients with bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L.12 These results, however, must be interpreted with extreme caution as the majority of studies included patients with ICP who were actively managed with attempts to mitigate the risk of stillbirth.7

In the absence of additional pregnancy risk factors, the risk of stillbirth among patients with ICP and serum bile acid levels between 19 and 39 µmol/L does not appear to be elevated above their baseline risk.11 The same is true for pregnant individuals with ICP and no additional pregnancy risk factors with serum bile acid levels between 40 and 99 µmol/L until approximately 38 weeks’ gestation, when the risk of stillbirth is elevated.11 The risk of stillbirth is elevated in ICP with peak bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L, with an absolute risk of 3.44%.11

Management of patients with ICP

Laboratory evaluation

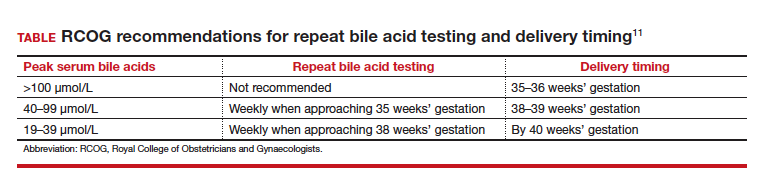

There is no consensus on the need for repeat testing of bile acid levels in patients with ICP. SMFM advises that follow-up testing of bile acid levels may help to guide delivery timing, especially in cases of severe ICP, but the society recommends against serial testing.7 By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) provides a detailed algorithm regarding time intervals between serum bile acid level testing to guide delivery timing.11 The TABLE lists the strategy for reassessment of serum bile acid levels in ICP as recommended by the RCOG.11

In the United States, bile acid testing traditionally takes several days as the testing is commonly performed at reference laboratories. We therefore suggest that clinicians consider repeating bile acid level testing in situations in which the timing of delivery may be altered if further elevations of bile acid levels were noted. This is particularly relevant for patients diagnosed with ICP early in the third trimester when repeat bile acid levels would still allow for an adjustment in delivery timing.

Antepartum fetal surveillance

Unfortunately, antepartum fetal testing for pregnant patients with ICP does not appear to reliably predict or prevent stillbirth as several studies have reported stillbirths within days of normal fetal testing.13-16 It is therefore important to counsel pregnant patients regarding monitoring of fetal movements and advise them to present for evaluation if concerns arise.

Currently, SMFM recommends that patients with ICP should begin antenatal fetal surveillance at a gestational age when abnormal fetal testing would result in delivery.7 Patients should be counseled, however, regarding the unpredictability of stillbirth with ICP in the setting of a low absolute risk of such.

Medications

While SMFM recommends a starting dose of ursodeoxycholic acid 10 to 15 mg/kg per day divided into 2 or 3 daily doses as first-line therapy for the treatment of maternal symptoms of ICP, it is important to acknowledge that the goal of treatment is to alleviate maternal symptoms as there is no evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid improves either maternal serum bile acid levels or perinatal outcomes.7,17,18 Since publication of the guidelines, ursodeoxycholic acid’s lack of benefit has been further confirmed in a meta-analysis, and thus discontinuation is not unreasonable in the absence of any improvement in maternal symptoms.18

Timing of delivery

The optimal management of ICP remains unknown. SMFM recommends delivery based on peak serum bile acid levels. Delivery is recommended at 36 weeks’ gestation with ICP and total bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L as these patients have the greatest risk of stillbirth.7 For patients with ICP and bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L, delivery is recommended between 36 0/7 and 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation.7 This is a wide gestational age window for clinicians to consider timing of delivery, and certainly the risks of stillbirth should be carefully balanced with the morbidity associated with a preterm or early term delivery.

For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels greater than 40 µmol/L, it is reasonable to consider delivery earlier in the gestational age window, given an evidence of increased risk of stillbirth after 38 weeks.7,12 For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels less than 40 µmol/L, delivery closer to 39 weeks’ gestation is recommended, as the risk of stillbirth does not appear to be increased above the baseline risk.7,12 Clinicians should be aware that the presence of concomitant morbidities, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and should be considered for delivery planning.19

Postpartum follow-up

Routine laboratory evaluation following delivery is not recommended.7 However, in the presence of persistent pruritus or other signs and symptoms of hepatobiliary disease, liver function tests should be repeated with referral to hepatology if results are persistently abnormal 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.7

CASE Patient follow-up and outcomes

CASE Pregnant woman with intense itching

A 28-year-old woman (G1P0) is seen for a routine prenatal visit at 32 3/7 weeks’ gestation. She reports having generalized intense itching, including on her palms and soles, that is most intense at night and has been present for approximately 1 week. Her pregnancy is otherwise uncomplicated to date. Physical exam is within normal limits, with no evidence of a skin rash. Cholestasis of pregnancy is suspected, and laboratory tests are ordered, including bile acids and liver transaminases. Test results show that her aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels are mildly elevated at 55 IU/L and 41 IU/L, respectively, and several days later her bile acid level result is 21 µmol/L.

How should this patient be managed?

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) affects 0.5% to 0.7% of pregnant individuals and results in maternal pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels.1-3 Pruritus in ICP typically is generalized, including occurrence on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, and it often is reported to be worse at night.4 Up to 25% of pregnant women will develop pruritus during pregnancy but the majority will not have ICP.2,5 Patients with ICP have no associated rash, but clinicians may note excoriations on exam. ICP typically presents in the third trimester of pregnancy but has been reported to occur earlier in gestation.6

Making a diagnosis of ICP

The presence of maternal pruritus in the absence of a skin condition along with elevated levels of serum bile acids are required for the diagnosis of ICP.7 Thus, a thorough history and physical exam is recommended to rule out another skin condition that could potentially explain the patient’s pruritus.

Some controversy exists regarding the bile acid level cutoff that should be used to make a diagnosis of ICP.8 It has been noted that nonfasting serum bile acid levels in pregnancy are considerably higher than those in in the nonpregnant state, and an upper limit of 18 µmol/L has been proposed as a cutoff in pregnancy.9 However, nonfasting total serum bile acids also have been shown to vary considerably by race, with levels 25.8% higher in Black women compared with those in White women and 24.3% higher in Black women compared with those in south Asian women.9 This raises the question of whether we should be using race-specific bile acid values to make a diagnosis of ICP.

Bile acid levels also vary based on whether a patient is in a fasting or postprandial state.10 Despite this variation, most guidelines do not recommend testing fasting bile acid levels as the postprandial state effect overall is small.7,9,11 The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) recommends that if a pregnancy-specific bile acid range is available from the laboratory, then the upper limit of normal for pregnancy should be used when making a diagnosis of ICP.7 The SMFM guidelines also acknowledge, however, that pregnancy-specific values rarely are available, and in this case, levels above the upper limit of normal—often 10 µmol/L should be considered diagnostic for ICP until further evidence regarding optimal bile acid cutoff levels in pregnancy becomes available.7

For patients with suspected ICP, liver transaminase levels should be measured in addition to nonfasting serum bile acid levels.7 A thorough history should include assessment for additional symptoms of liver disease, such as changes in weight, appetite, jaundice, excessive fatigue, malaise, and abdominal pain.7 Elevated transaminases levels may be associated with ICP, but they are not necessary for diagnosis. In the absence of additional clinical symptoms that suggest underlying liver disease or severe early onset ICP, additional evaluation beyond nonfasting serum bile acids and liver transaminase levels, such as liver ultrasonography or evaluation for viral or autoimmune hepatitis, is not recommended.7 Obstetric care clinicians should be aware that there is an increased incidence of preeclampsia among patients with ICP, although no specific guidance regarding further recommendations for screening is provided.7

Continue to: Risks associated with ICP...

Risks associated with ICP

For both patients and clinicians, the greatest concern among patients with ICP is the increased risk of stillbirth. Stillbirth risk in ICP appears to be related to serum bile acid levels and has been reported to be highest in patients with bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of ICP studies demonstrated no increased risk of stillbirth among patients with bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L.12 These results, however, must be interpreted with extreme caution as the majority of studies included patients with ICP who were actively managed with attempts to mitigate the risk of stillbirth.7

In the absence of additional pregnancy risk factors, the risk of stillbirth among patients with ICP and serum bile acid levels between 19 and 39 µmol/L does not appear to be elevated above their baseline risk.11 The same is true for pregnant individuals with ICP and no additional pregnancy risk factors with serum bile acid levels between 40 and 99 µmol/L until approximately 38 weeks’ gestation, when the risk of stillbirth is elevated.11 The risk of stillbirth is elevated in ICP with peak bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L, with an absolute risk of 3.44%.11

Management of patients with ICP

Laboratory evaluation

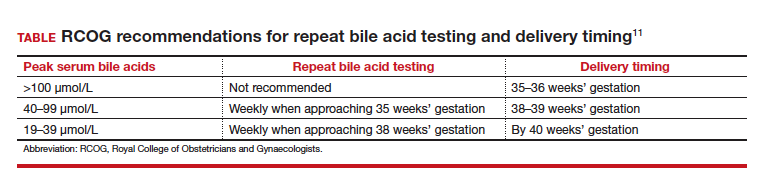

There is no consensus on the need for repeat testing of bile acid levels in patients with ICP. SMFM advises that follow-up testing of bile acid levels may help to guide delivery timing, especially in cases of severe ICP, but the society recommends against serial testing.7 By contrast, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) provides a detailed algorithm regarding time intervals between serum bile acid level testing to guide delivery timing.11 The TABLE lists the strategy for reassessment of serum bile acid levels in ICP as recommended by the RCOG.11

In the United States, bile acid testing traditionally takes several days as the testing is commonly performed at reference laboratories. We therefore suggest that clinicians consider repeating bile acid level testing in situations in which the timing of delivery may be altered if further elevations of bile acid levels were noted. This is particularly relevant for patients diagnosed with ICP early in the third trimester when repeat bile acid levels would still allow for an adjustment in delivery timing.

Antepartum fetal surveillance

Unfortunately, antepartum fetal testing for pregnant patients with ICP does not appear to reliably predict or prevent stillbirth as several studies have reported stillbirths within days of normal fetal testing.13-16 It is therefore important to counsel pregnant patients regarding monitoring of fetal movements and advise them to present for evaluation if concerns arise.

Currently, SMFM recommends that patients with ICP should begin antenatal fetal surveillance at a gestational age when abnormal fetal testing would result in delivery.7 Patients should be counseled, however, regarding the unpredictability of stillbirth with ICP in the setting of a low absolute risk of such.

Medications

While SMFM recommends a starting dose of ursodeoxycholic acid 10 to 15 mg/kg per day divided into 2 or 3 daily doses as first-line therapy for the treatment of maternal symptoms of ICP, it is important to acknowledge that the goal of treatment is to alleviate maternal symptoms as there is no evidence that ursodeoxycholic acid improves either maternal serum bile acid levels or perinatal outcomes.7,17,18 Since publication of the guidelines, ursodeoxycholic acid’s lack of benefit has been further confirmed in a meta-analysis, and thus discontinuation is not unreasonable in the absence of any improvement in maternal symptoms.18

Timing of delivery

The optimal management of ICP remains unknown. SMFM recommends delivery based on peak serum bile acid levels. Delivery is recommended at 36 weeks’ gestation with ICP and total bile acid levels greater than 100 µmol/L as these patients have the greatest risk of stillbirth.7 For patients with ICP and bile acid levels less than 100 µmol/L, delivery is recommended between 36 0/7 and 39 0/7 weeks’ gestation.7 This is a wide gestational age window for clinicians to consider timing of delivery, and certainly the risks of stillbirth should be carefully balanced with the morbidity associated with a preterm or early term delivery.

For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels greater than 40 µmol/L, it is reasonable to consider delivery earlier in the gestational age window, given an evidence of increased risk of stillbirth after 38 weeks.7,12 For patients with ICP who have bile acid levels less than 40 µmol/L, delivery closer to 39 weeks’ gestation is recommended, as the risk of stillbirth does not appear to be increased above the baseline risk.7,12 Clinicians should be aware that the presence of concomitant morbidities, such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes, are associated with an increased risk of stillbirth and should be considered for delivery planning.19

Postpartum follow-up

Routine laboratory evaluation following delivery is not recommended.7 However, in the presence of persistent pruritus or other signs and symptoms of hepatobiliary disease, liver function tests should be repeated with referral to hepatology if results are persistently abnormal 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.7

CASE Patient follow-up and outcomes

- Abedin P, Weaver JB, Egginton E. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: prevalence and ethnic distribution. Ethn Health. 1999;4:35-37.

- Kenyon AP, Tribe RM, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Pruritus in pregnancy: a study of anatomical distribution and prevalence in relation to the development of obstetric cholestasis. Obstet Med. 2010;3:25-29.

- Wikstrom Shemer E, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: a 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:717-723.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM, Glatz M, Trauner M, et al. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a case series from central Europe. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:757-762.

- Szczech J, Wiatrowski A, Hirnle L, et al. Prevalence and relevance of pruritus in pregnancy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4238139.

- Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2049-2066.

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; Lee RH, Greenberg M, Metz TD, et al. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #53: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: replaces Consult #13, April 2011. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:B2-B9.

- Horgan R, Bitas C, Abuhamad A. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a comparison of Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:100838.

- Mitchell AL, Ovadia C, Syngelaki A, et al. Re-evaluating diagnostic thresholds for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: case-control and cohort study. BJOG. 2021;128:1635-1644.

- Adams A, Jacobs K, Vogel RI, et al. Bile acid determination after standardized glucose load in pregnant women. AJP Rep. 2015;5:e168-e171.

- Girling J, Knight CL, Chappell L; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Green-top guideline no. 43, June 2022. BJOG. 2022;129:e95-e114.

- Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393:899-909.

- Alsulyman OM, Ouzounian JG, Ames-Castro M, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: perinatal outcome associated with expectant management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:957-960.

- Herrera CA, Manuck TA, Stoddard GJ, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1913-1920.

- Lee RH, Incerpi MH, Miller DA, et al. Sudden fetal death in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:528-531.

- Sentilhes L, Verspyck E, Pia P, et al. Fetal death in a patient with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:458-460.

- Chappell LC, Bell JL, Smith A, et al; PITCHES Study Group. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:849-860.

- Ovadia C, Sajous J, Seed PT, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:547-558.

- Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482-1491.

- Abedin P, Weaver JB, Egginton E. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: prevalence and ethnic distribution. Ethn Health. 1999;4:35-37.

- Kenyon AP, Tribe RM, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Pruritus in pregnancy: a study of anatomical distribution and prevalence in relation to the development of obstetric cholestasis. Obstet Med. 2010;3:25-29.

- Wikstrom Shemer E, Marschall HU, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and associated adverse pregnancy and fetal outcomes: a 12-year population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:717-723.

- Ambros-Rudolph CM, Glatz M, Trauner M, et al. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a case series from central Europe. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:757-762.

- Szczech J, Wiatrowski A, Hirnle L, et al. Prevalence and relevance of pruritus in pregnancy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4238139.

- Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2049-2066.