User login

Necrotizing Fasciitis Caused by Cryptococcus gattii

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe, rapidly spreading soft-tissue infection with high morbidity and mortality. Bacteriology in NF may be varied, and the etiology is often polymicrobial. It is important to consider the potential for fungal involvement despite its rarity. Cryptococcal NF has been reported in immunocompromised patients, with Cryptococcus neoformans being the most common offending organism.1-4

C neoformans is a basidiomycotic yeast that was previously considered a homogenous species.5,6 From the antigenic properties of its polysaccharide capsule, 3 main variants were described: C neoformans var. grubii, C neoformans var. neoformans, and C neoformans var. gattii. Subsequently, C neoformans var. gattii was found to be genetically and biochemically different from C neoformans. This discovery led to the distinction of C neoformans var. gattii as a separate species and it being renamed C gattii.6

C gattii was first recognized on Vancouver Island in 2001.7 Although C gattii is predominantly restricted to tropical and subtropical climates, its true epidemiology has been limited by diagnostic methods. C gattii can be diagnosed with laboratory culture media such as birdseed agars and L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol (CGB) agar.6 However, most reports of Cryptococcus NF do not specify the culture media used to isolate Cryptococcus. In addition to culture media, molecular genotyping studies also allow for confirmation of the diagnosis of C gattii and have the added benefit of enabling identification of the molecular genotype. Nonetheless, in many clinical microbiology laboratories, Cryptococcus is not identified to the species level, much less to the molecular genotype.7 Given these diagnostic limitations and the fact that C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, it is possible that any pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans could in fact have been caused by C gattii.

In this article, we review the literature and report a case of NF of the hand that was caused by C gattii in a patient with diabetes. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of NF caused by C gattii. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man was admitted with a 1-week history of swelling and pain in the dorsum of the left hand. He had been sitting in an outdoor eatery in Singapore when an insect bit the hand over the dorsum. Two days later, he consulted his family physician, who began treatment with oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. After 4 days of treatment, there was clinical progression of increased swelling and pain in the hand. Six days after initial injury, the patient presented to the department of orthopedic surgery.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, brawny, nonfluctuant swelling over the entire dorsum of the left hand (Figure 1). There was a 1×1-cm ruptured blister with some nonpurulent discharge just distal to the wrist joint. Neurovascular status and the extensor mechanism of the fingers were intact. The wrist joint had full range of motion. There was no fever.

Laboratory testing revealed an elevated white blood cell count (16.6×109/L), a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 237 nmol/L, a random blood glucose level of 12.6 mmol/L, and a LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score of 7.8

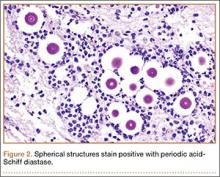

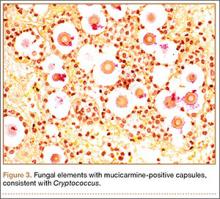

Given the severe swelling, intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was started. The patient received a total of 3 doses before operative débridement of the left hand. Operative findings were NF of the hand, grayish necrotic fascia, and foul-smelling “dishwater” fluid. A single specimen of fascia from the surgical site was sent for examination. Histopathologic examination of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue revealed necrotizing suppurative inflammation with fungal organisms present (Figures 2, 3).

Tissue cultures were obtained during surgery. The organism grew as scanty, small, wet-looking colonies on sheep blood agar after 48 hours of incubation. Microscopy revealed an oval yeast. The organism was identified and reported as C gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Biotyper 2.0.1 software; Bruker Daltonics), with a score of 1.914.9 All other intraoperative cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were negative. Molecular genotyping was performed with polymerase chain reaction assay to identify the molecular subtype.10C gattii genotype VGII was isolated. A cryptococcal serum antigen assay was positive at 1:256.

A series of tests was performed to screen for disseminated disease. Blood cultures were negative for fungus. Chest radiography and computed tomography of the brain did not show any pulmonary or cerebral involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid was not available for examination, as the patient declined lumbar puncture. Blood tests included a negative result for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient was found to have previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9%). T-cell counts and ratios were normal.

The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B 60 mg/d and flucytosine 500 mg every 6 hours for 3 weeks. Oral fluconazole 400 mg every morning was also given (intended duration, 6 mo). Given that diabetes was newly diagnosed, the patient was treated with metformin; his capillary blood glucose level remained stable during his inpatient stay.

Four débridements of the dorsal hand wound were performed—the first on day of admission and the other 3 on hospitalization days 3, 7, and 18 (Figure 4). Subsequent wound resurfacing with a split skin graft harvested from the forearm was performed on hospitalization day 22. After surgery, the hand was dressed with a bulky cotton dressing. Five days after the patient was discharged, during review in the outpatient clinic, the skin graft was noted to be taking well. The patient did not attend postoperative physical therapy. He was maintained on metformin and given a follow-up clinic appointment for his diabetes. Four months after surgery, the wound was completely healed, and normal functional use of the hand recovered.

Discussion

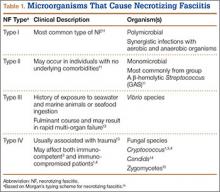

NF is a severe soft-tissue infection with potential for rapid progression. Surgical débridement should be performed urgently to reduce the chance of morbidity and mortality.11 The initial classification by Giuliano and colleagues12 was based on bacteriology and included type I (anaerobic species in combination with a facultative species) and type II (monomicrobial usually involving group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus). This classification was modified by Morgan13 to include gram-negative organisms as well as fungal organisms (Table 1).

Fungal NF is rare, with Candida, Apophysomyces, and Cryptococcus described in the literature.1,14,15 Fungal infections tend to occur in immunocompromised patients; risk factors are steroid immunosuppression, poorly controlled diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease.16 Some zygomycetes may also affect immunocompetent patients.15

C gattii is an encapsulated yeast organism that is genetically and biochemically distinct from C neoformans. It is endemic to tropical parts of Africa and Australia. Its main environmental sources are eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus tereticornis) and decaying hollows in living trees.17 In addition, there have been reports of isolation of C gattii from insect frass,18 which would make infection by an insect bite a possible transmission route. Worldwide distribution of this pathogen has increased recently, with outbreaks noted on Vancouver Island and in areas in Canada and the northwest United States.7

The true incidence of NF secondary to C gattii is difficult to determine. C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, and pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans may instead have been caused by C gattii. Misidentification has been compounded by the fact that the tests required for accurate diagnosis of C gattii infection may not be readily available in many clinical microbiology laboratories. Cryptococcus can be identified with various methods, including direct microscopy, culturing of tissue or fluid samples, and measurement of cryptococcal serum antigen. However, tests such as specific culture media, mass spectrometry, and molecular typing studies are required to determine cryptococcal species. L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar is a medium that is often used to differentiate C gattii from C neoformans because of the ability of C gattii to produce a blue appearance.6 Modern techniques, such as MALDI-TOF MS, have also been used to successfully distinguish between C gattii and C neoformans.9 MALDI-TOF MS identifies species on the basis of characteristic protein spectra extracted from whole cells. Using commercial and supplemental reference libraries, the system compares signal matches in the reference spectrum with Cryptococcus entries in the library—allowing rapid and accurate identification of cryptococcal species. However, this diagnostic method is limited by availability of adequate Cryptococcus entries in the reference library and by the high cost of acquiring the machine.

Serotyping is based on the antigenic property of the capsule and was once used to differentiate C neoformans into its 3 main varieties: var. neoformans, var. grubii, var. gattii. However, when it was realized that the antigenic property of the strain can be unstable and that there are hybrids containing more than 1 serotype, serotyping was abandoned as a species-differentiation test.6 The current gold standard for species differentiation is molecular genotyping. Molecular genotyping studies can confirm the diagnosis of C gattii infection and allow differentiation of C gattii into its 4 main molecular types: VGI, VGII, VGIII, VGIV. Using methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, molecular typing allows for specific epidemiology charting of C gattii genotypes.7

Although the transmission route for cryptococcal infection is mainly respiratory, direct inoculation has been reported as well.19 Cutaneous lesions, which occur in 5% to 20% of cryptococcal infections, often present in the head and neck.2,20,21 Primary cutaneous infections from cryptococcosis are rare, and cutaneous manifestations are often a sign of disseminated disease. Disseminated disease is defined as the involvement of 2 or more noncontiguous sites or evidence of high fungal burden based on cryptococcal antigen titer of more than 1:512.12 It is important to exclude disseminated disease in all cases of cryptococcosis, as it may be fatal.20 The neural and pulmonary systems should be screened.22 Cellulitis from cryptococcosis is almost always limited to immunocompromised patients, though there are reports of crytococcal cutaneous disease in immunocompetent patients.3,15 Interestingly, though C neoformans often affects immunocompromised patients, the emerging pathogen of C gattii affects immunocompetent patients.7,17,23 Our patient’s undiagnosed diabetes may have been a risk factor for cryptococcal infection. His cryptococcal antigen titer was 1:256, with no evidence of other sites of involvement. We therefore believe this to be a rare case of direct inoculation secondary to an insect bite.

The literature includes 12 reported cases of NF secondary to Cryptococcus (Table 2), all C neoformans. Of these cases, 9 involved immunosuppression, and most of these patients were on long-term steroid treatment after organ transplantation. The most common infection site was the lower extremity. These cases of cryptococcal NF show that immunosuppression, and long-term steroid use in particular, is an important risk factor. The mortality rate for these reviewed cases was 41.6% (5/12). According to the literature, the mortality rates for patients with cryptococcal soft-tissue infections24 and posttransplant patients with cryptococcal NF21 were 37.5% and 60%, respectively. We believe the mortality rate in our reviewed cases likely was confounded by the fact that most of the patients were posttransplant patients on long-term immunosuppression.

Of the 12 patients, 5 had primary cutaneous disease. There seems to be no relationship between outcome and dissemination of disease. In addition, there is a paucity of literature on the effect of disseminated disease and cryptococcal soft-tissue infections. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of disseminated disease on severity of cryptococcal soft-tissue infection.

Treatment of cryptococcal NF involves a combination of surgical débridement and long-term antifungal therapy. Surgical débridement of NF includes delineating the extent of infection with complete surgical excision of the affected tissue.25 The aims of surgery should be to remove all unhealthy tissue, identify the offending organism, and plan for resurfacing or reconstruction of the afflicted extremity. Intraoperative-tissue histology should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of NF. Histology can be used to demonstrate cryptococcal infection. The diagnosis of cryptococcal infection can be aided with fungal cultures, and therefore we recommend that tissue cultures be sent not only for routine aerobic/anaerobic bacteria but also for mycobacteria and fungal organisms. Laboratory tests that aid in diagnosis include serum cryptococcal antigen titer.

The current treatment recommendation for cryptococcal disease in patients who are not HIV-positive or transplant hosts is amphotericin B deoxycholate 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/d plus flucytosine 100 mg/kg/d for at least 4 weeks.22 The regimen period may be shortened to 14 days for patients at low risk of treatment failure. Fluconazole should be given as maintenance therapy (200 mg/d) for 6 to 12 months. There is no compelling evidence for immunoglobulin therapy for cryptococcal disease.22

Conclusion

NF caused by Cryptococcus is rare. A high level of suspicion, and intraoperative specimens for histology and fungal microscopy and culture, can help in establishing the diagnosis. Molecular genotyping remains the diagnostic method of choice for NF secondary to Cryptococcus. Effective treatment consists of aggressive surgical débridement and antifungal therapy.

1. Marcus JR, Hussong JW, Gonzalez C, Dumanian GA. Risk factors in necrotizing fasciitis: a case involving Cryptococcus neoformans. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40(1):80-83.

2. Huang KC, Tu YK, Lee KF, Huang TJ, Wen-Wei Hsu R. Disseminated cryptococcosis presented as necrotizing fasciitis of a limb. J Trauma. 2007;63(2):E44-E46.

3. Capoor MR, Khanna G, Malhotra R. Disseminated cryptococcosis with necrotizing fasciitis in an apparently immunocompetent host: a case report. Med Mycol. 2008;46:269-273.

4. Adachi M, Tsurata D, Imanishi H, Ishii M, Kobayashi H. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans in a patient with pemphigus vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e751-e753.

5. Enache-Angoulvant A, Chandenier J, Symoens F, et al. Molecular identification of Cryptococcus neoformans serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(4):1261-1265.

6. Kwon-Chung KJ, Varma A. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6(4):657-687.

7. Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, et al; Cryptococcus gattii Working Group of the Pacific Northwest. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(8):1185-1191.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. McTaggart LR, Lei E, Richardson SE, Hoang L, Fothergill A, Zhang SX. Rapid identification of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(8):3050-3053.

10. Meyer W, Castañeda A, Jackson S, Huynh M, Castañeda E; IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):189-195.

11. Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1454-1460.

12. Giuliano A, Lewis F Jr, Hadley K, Blaisdell FW. Bacteriology of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134(1):52-57.

13. Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotising fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(4):249-257.

14. Buchanan PJ, Mast BA, Lottenberg L, Kim T, Efron PA, Ang DN. Candida albicans necrotizing soft tissue infection: a case report and literature review of fungal necrotizing soft tissue infections. Ann Plastic Surg. 2013;70(6):739-741.

15. Jain D, Kumar Y, Vasishta RK, Rajesh L, Pattari SK, Chakrabarti A. Zygomycotic necrotizing fasciitis in immunocompetent patients: a series of 18 cases. Modern Pathol. 2006;19(9):1221-1226.

16. Fontes RA Jr, Ogilvie CM, Miclau T. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(3):151-158.

17. Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39(2):155-168.

18. Kidd SE, Sorrell TC, Meyer W. Isolation of two molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from insect frass. Med Mycol. 2003;41(2):171-176.

19. Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):337-347.

20. Basaran O, Emiroglu R, Arikan U, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis with multiple sites of involvement in the lower extremities. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(11):1158-1160.

21. Baer S, Baddley JW, Gnann JW, Pappas PG. Cryptococcal disease presenting as necrotizing cellulitis in transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11(4):353-358.

22. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291-322.

23. Chan M, Lye D, Win MK, Chow A, Barkham T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of cryptococcosis in Singapore: predominance of Cryptococcus neoformans compared with Cryptococcus gattii. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:110-115.

24. Gave AA, Torres R, Kaplan L. Cryptococcal myositis and vasculitis: an unusual necrotizing soft tissue infection. Surg Infect. 2004;5(3):309-313.

25. Wong CH, Yam AK, Tan AB, Song C. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196(3):e19-e24.

26. Bégon E, Bachmeyer C, Thibault M, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a diabetic patient with chronic renal insufficiency. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):935-936.

27. Doorenbos-Bot AC, Hooymans JM, Blanksma LJ. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a healthy young man. Doc Ophthalmol. 1990;75(3-4):315-320.

28. Yoneda T, Itami Y, Hirayama A, Saka T, Yoshida K, Fujimoto K. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis in a patient after renal transplantation—a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(2):620-622.

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe, rapidly spreading soft-tissue infection with high morbidity and mortality. Bacteriology in NF may be varied, and the etiology is often polymicrobial. It is important to consider the potential for fungal involvement despite its rarity. Cryptococcal NF has been reported in immunocompromised patients, with Cryptococcus neoformans being the most common offending organism.1-4

C neoformans is a basidiomycotic yeast that was previously considered a homogenous species.5,6 From the antigenic properties of its polysaccharide capsule, 3 main variants were described: C neoformans var. grubii, C neoformans var. neoformans, and C neoformans var. gattii. Subsequently, C neoformans var. gattii was found to be genetically and biochemically different from C neoformans. This discovery led to the distinction of C neoformans var. gattii as a separate species and it being renamed C gattii.6

C gattii was first recognized on Vancouver Island in 2001.7 Although C gattii is predominantly restricted to tropical and subtropical climates, its true epidemiology has been limited by diagnostic methods. C gattii can be diagnosed with laboratory culture media such as birdseed agars and L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol (CGB) agar.6 However, most reports of Cryptococcus NF do not specify the culture media used to isolate Cryptococcus. In addition to culture media, molecular genotyping studies also allow for confirmation of the diagnosis of C gattii and have the added benefit of enabling identification of the molecular genotype. Nonetheless, in many clinical microbiology laboratories, Cryptococcus is not identified to the species level, much less to the molecular genotype.7 Given these diagnostic limitations and the fact that C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, it is possible that any pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans could in fact have been caused by C gattii.

In this article, we review the literature and report a case of NF of the hand that was caused by C gattii in a patient with diabetes. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of NF caused by C gattii. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man was admitted with a 1-week history of swelling and pain in the dorsum of the left hand. He had been sitting in an outdoor eatery in Singapore when an insect bit the hand over the dorsum. Two days later, he consulted his family physician, who began treatment with oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. After 4 days of treatment, there was clinical progression of increased swelling and pain in the hand. Six days after initial injury, the patient presented to the department of orthopedic surgery.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, brawny, nonfluctuant swelling over the entire dorsum of the left hand (Figure 1). There was a 1×1-cm ruptured blister with some nonpurulent discharge just distal to the wrist joint. Neurovascular status and the extensor mechanism of the fingers were intact. The wrist joint had full range of motion. There was no fever.

Laboratory testing revealed an elevated white blood cell count (16.6×109/L), a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 237 nmol/L, a random blood glucose level of 12.6 mmol/L, and a LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score of 7.8

Given the severe swelling, intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was started. The patient received a total of 3 doses before operative débridement of the left hand. Operative findings were NF of the hand, grayish necrotic fascia, and foul-smelling “dishwater” fluid. A single specimen of fascia from the surgical site was sent for examination. Histopathologic examination of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue revealed necrotizing suppurative inflammation with fungal organisms present (Figures 2, 3).

Tissue cultures were obtained during surgery. The organism grew as scanty, small, wet-looking colonies on sheep blood agar after 48 hours of incubation. Microscopy revealed an oval yeast. The organism was identified and reported as C gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Biotyper 2.0.1 software; Bruker Daltonics), with a score of 1.914.9 All other intraoperative cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were negative. Molecular genotyping was performed with polymerase chain reaction assay to identify the molecular subtype.10C gattii genotype VGII was isolated. A cryptococcal serum antigen assay was positive at 1:256.

A series of tests was performed to screen for disseminated disease. Blood cultures were negative for fungus. Chest radiography and computed tomography of the brain did not show any pulmonary or cerebral involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid was not available for examination, as the patient declined lumbar puncture. Blood tests included a negative result for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient was found to have previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9%). T-cell counts and ratios were normal.

The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B 60 mg/d and flucytosine 500 mg every 6 hours for 3 weeks. Oral fluconazole 400 mg every morning was also given (intended duration, 6 mo). Given that diabetes was newly diagnosed, the patient was treated with metformin; his capillary blood glucose level remained stable during his inpatient stay.

Four débridements of the dorsal hand wound were performed—the first on day of admission and the other 3 on hospitalization days 3, 7, and 18 (Figure 4). Subsequent wound resurfacing with a split skin graft harvested from the forearm was performed on hospitalization day 22. After surgery, the hand was dressed with a bulky cotton dressing. Five days after the patient was discharged, during review in the outpatient clinic, the skin graft was noted to be taking well. The patient did not attend postoperative physical therapy. He was maintained on metformin and given a follow-up clinic appointment for his diabetes. Four months after surgery, the wound was completely healed, and normal functional use of the hand recovered.

Discussion

NF is a severe soft-tissue infection with potential for rapid progression. Surgical débridement should be performed urgently to reduce the chance of morbidity and mortality.11 The initial classification by Giuliano and colleagues12 was based on bacteriology and included type I (anaerobic species in combination with a facultative species) and type II (monomicrobial usually involving group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus). This classification was modified by Morgan13 to include gram-negative organisms as well as fungal organisms (Table 1).

Fungal NF is rare, with Candida, Apophysomyces, and Cryptococcus described in the literature.1,14,15 Fungal infections tend to occur in immunocompromised patients; risk factors are steroid immunosuppression, poorly controlled diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease.16 Some zygomycetes may also affect immunocompetent patients.15

C gattii is an encapsulated yeast organism that is genetically and biochemically distinct from C neoformans. It is endemic to tropical parts of Africa and Australia. Its main environmental sources are eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus tereticornis) and decaying hollows in living trees.17 In addition, there have been reports of isolation of C gattii from insect frass,18 which would make infection by an insect bite a possible transmission route. Worldwide distribution of this pathogen has increased recently, with outbreaks noted on Vancouver Island and in areas in Canada and the northwest United States.7

The true incidence of NF secondary to C gattii is difficult to determine. C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, and pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans may instead have been caused by C gattii. Misidentification has been compounded by the fact that the tests required for accurate diagnosis of C gattii infection may not be readily available in many clinical microbiology laboratories. Cryptococcus can be identified with various methods, including direct microscopy, culturing of tissue or fluid samples, and measurement of cryptococcal serum antigen. However, tests such as specific culture media, mass spectrometry, and molecular typing studies are required to determine cryptococcal species. L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar is a medium that is often used to differentiate C gattii from C neoformans because of the ability of C gattii to produce a blue appearance.6 Modern techniques, such as MALDI-TOF MS, have also been used to successfully distinguish between C gattii and C neoformans.9 MALDI-TOF MS identifies species on the basis of characteristic protein spectra extracted from whole cells. Using commercial and supplemental reference libraries, the system compares signal matches in the reference spectrum with Cryptococcus entries in the library—allowing rapid and accurate identification of cryptococcal species. However, this diagnostic method is limited by availability of adequate Cryptococcus entries in the reference library and by the high cost of acquiring the machine.

Serotyping is based on the antigenic property of the capsule and was once used to differentiate C neoformans into its 3 main varieties: var. neoformans, var. grubii, var. gattii. However, when it was realized that the antigenic property of the strain can be unstable and that there are hybrids containing more than 1 serotype, serotyping was abandoned as a species-differentiation test.6 The current gold standard for species differentiation is molecular genotyping. Molecular genotyping studies can confirm the diagnosis of C gattii infection and allow differentiation of C gattii into its 4 main molecular types: VGI, VGII, VGIII, VGIV. Using methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, molecular typing allows for specific epidemiology charting of C gattii genotypes.7

Although the transmission route for cryptococcal infection is mainly respiratory, direct inoculation has been reported as well.19 Cutaneous lesions, which occur in 5% to 20% of cryptococcal infections, often present in the head and neck.2,20,21 Primary cutaneous infections from cryptococcosis are rare, and cutaneous manifestations are often a sign of disseminated disease. Disseminated disease is defined as the involvement of 2 or more noncontiguous sites or evidence of high fungal burden based on cryptococcal antigen titer of more than 1:512.12 It is important to exclude disseminated disease in all cases of cryptococcosis, as it may be fatal.20 The neural and pulmonary systems should be screened.22 Cellulitis from cryptococcosis is almost always limited to immunocompromised patients, though there are reports of crytococcal cutaneous disease in immunocompetent patients.3,15 Interestingly, though C neoformans often affects immunocompromised patients, the emerging pathogen of C gattii affects immunocompetent patients.7,17,23 Our patient’s undiagnosed diabetes may have been a risk factor for cryptococcal infection. His cryptococcal antigen titer was 1:256, with no evidence of other sites of involvement. We therefore believe this to be a rare case of direct inoculation secondary to an insect bite.

The literature includes 12 reported cases of NF secondary to Cryptococcus (Table 2), all C neoformans. Of these cases, 9 involved immunosuppression, and most of these patients were on long-term steroid treatment after organ transplantation. The most common infection site was the lower extremity. These cases of cryptococcal NF show that immunosuppression, and long-term steroid use in particular, is an important risk factor. The mortality rate for these reviewed cases was 41.6% (5/12). According to the literature, the mortality rates for patients with cryptococcal soft-tissue infections24 and posttransplant patients with cryptococcal NF21 were 37.5% and 60%, respectively. We believe the mortality rate in our reviewed cases likely was confounded by the fact that most of the patients were posttransplant patients on long-term immunosuppression.

Of the 12 patients, 5 had primary cutaneous disease. There seems to be no relationship between outcome and dissemination of disease. In addition, there is a paucity of literature on the effect of disseminated disease and cryptococcal soft-tissue infections. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of disseminated disease on severity of cryptococcal soft-tissue infection.

Treatment of cryptococcal NF involves a combination of surgical débridement and long-term antifungal therapy. Surgical débridement of NF includes delineating the extent of infection with complete surgical excision of the affected tissue.25 The aims of surgery should be to remove all unhealthy tissue, identify the offending organism, and plan for resurfacing or reconstruction of the afflicted extremity. Intraoperative-tissue histology should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of NF. Histology can be used to demonstrate cryptococcal infection. The diagnosis of cryptococcal infection can be aided with fungal cultures, and therefore we recommend that tissue cultures be sent not only for routine aerobic/anaerobic bacteria but also for mycobacteria and fungal organisms. Laboratory tests that aid in diagnosis include serum cryptococcal antigen titer.

The current treatment recommendation for cryptococcal disease in patients who are not HIV-positive or transplant hosts is amphotericin B deoxycholate 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/d plus flucytosine 100 mg/kg/d for at least 4 weeks.22 The regimen period may be shortened to 14 days for patients at low risk of treatment failure. Fluconazole should be given as maintenance therapy (200 mg/d) for 6 to 12 months. There is no compelling evidence for immunoglobulin therapy for cryptococcal disease.22

Conclusion

NF caused by Cryptococcus is rare. A high level of suspicion, and intraoperative specimens for histology and fungal microscopy and culture, can help in establishing the diagnosis. Molecular genotyping remains the diagnostic method of choice for NF secondary to Cryptococcus. Effective treatment consists of aggressive surgical débridement and antifungal therapy.

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a severe, rapidly spreading soft-tissue infection with high morbidity and mortality. Bacteriology in NF may be varied, and the etiology is often polymicrobial. It is important to consider the potential for fungal involvement despite its rarity. Cryptococcal NF has been reported in immunocompromised patients, with Cryptococcus neoformans being the most common offending organism.1-4

C neoformans is a basidiomycotic yeast that was previously considered a homogenous species.5,6 From the antigenic properties of its polysaccharide capsule, 3 main variants were described: C neoformans var. grubii, C neoformans var. neoformans, and C neoformans var. gattii. Subsequently, C neoformans var. gattii was found to be genetically and biochemically different from C neoformans. This discovery led to the distinction of C neoformans var. gattii as a separate species and it being renamed C gattii.6

C gattii was first recognized on Vancouver Island in 2001.7 Although C gattii is predominantly restricted to tropical and subtropical climates, its true epidemiology has been limited by diagnostic methods. C gattii can be diagnosed with laboratory culture media such as birdseed agars and L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol (CGB) agar.6 However, most reports of Cryptococcus NF do not specify the culture media used to isolate Cryptococcus. In addition to culture media, molecular genotyping studies also allow for confirmation of the diagnosis of C gattii and have the added benefit of enabling identification of the molecular genotype. Nonetheless, in many clinical microbiology laboratories, Cryptococcus is not identified to the species level, much less to the molecular genotype.7 Given these diagnostic limitations and the fact that C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, it is possible that any pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans could in fact have been caused by C gattii.

In this article, we review the literature and report a case of NF of the hand that was caused by C gattii in a patient with diabetes. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of NF caused by C gattii. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 73-year-old man was admitted with a 1-week history of swelling and pain in the dorsum of the left hand. He had been sitting in an outdoor eatery in Singapore when an insect bit the hand over the dorsum. Two days later, he consulted his family physician, who began treatment with oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. After 4 days of treatment, there was clinical progression of increased swelling and pain in the hand. Six days after initial injury, the patient presented to the department of orthopedic surgery.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, brawny, nonfluctuant swelling over the entire dorsum of the left hand (Figure 1). There was a 1×1-cm ruptured blister with some nonpurulent discharge just distal to the wrist joint. Neurovascular status and the extensor mechanism of the fingers were intact. The wrist joint had full range of motion. There was no fever.

Laboratory testing revealed an elevated white blood cell count (16.6×109/L), a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 237 nmol/L, a random blood glucose level of 12.6 mmol/L, and a LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score of 7.8

Given the severe swelling, intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was started. The patient received a total of 3 doses before operative débridement of the left hand. Operative findings were NF of the hand, grayish necrotic fascia, and foul-smelling “dishwater” fluid. A single specimen of fascia from the surgical site was sent for examination. Histopathologic examination of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue revealed necrotizing suppurative inflammation with fungal organisms present (Figures 2, 3).

Tissue cultures were obtained during surgery. The organism grew as scanty, small, wet-looking colonies on sheep blood agar after 48 hours of incubation. Microscopy revealed an oval yeast. The organism was identified and reported as C gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Biotyper 2.0.1 software; Bruker Daltonics), with a score of 1.914.9 All other intraoperative cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were negative. Molecular genotyping was performed with polymerase chain reaction assay to identify the molecular subtype.10C gattii genotype VGII was isolated. A cryptococcal serum antigen assay was positive at 1:256.

A series of tests was performed to screen for disseminated disease. Blood cultures were negative for fungus. Chest radiography and computed tomography of the brain did not show any pulmonary or cerebral involvement. Cerebrospinal fluid was not available for examination, as the patient declined lumbar puncture. Blood tests included a negative result for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The patient was found to have previously undiagnosed diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c, 7.9%). T-cell counts and ratios were normal.

The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B 60 mg/d and flucytosine 500 mg every 6 hours for 3 weeks. Oral fluconazole 400 mg every morning was also given (intended duration, 6 mo). Given that diabetes was newly diagnosed, the patient was treated with metformin; his capillary blood glucose level remained stable during his inpatient stay.

Four débridements of the dorsal hand wound were performed—the first on day of admission and the other 3 on hospitalization days 3, 7, and 18 (Figure 4). Subsequent wound resurfacing with a split skin graft harvested from the forearm was performed on hospitalization day 22. After surgery, the hand was dressed with a bulky cotton dressing. Five days after the patient was discharged, during review in the outpatient clinic, the skin graft was noted to be taking well. The patient did not attend postoperative physical therapy. He was maintained on metformin and given a follow-up clinic appointment for his diabetes. Four months after surgery, the wound was completely healed, and normal functional use of the hand recovered.

Discussion

NF is a severe soft-tissue infection with potential for rapid progression. Surgical débridement should be performed urgently to reduce the chance of morbidity and mortality.11 The initial classification by Giuliano and colleagues12 was based on bacteriology and included type I (anaerobic species in combination with a facultative species) and type II (monomicrobial usually involving group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus). This classification was modified by Morgan13 to include gram-negative organisms as well as fungal organisms (Table 1).

Fungal NF is rare, with Candida, Apophysomyces, and Cryptococcus described in the literature.1,14,15 Fungal infections tend to occur in immunocompromised patients; risk factors are steroid immunosuppression, poorly controlled diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease.16 Some zygomycetes may also affect immunocompetent patients.15

C gattii is an encapsulated yeast organism that is genetically and biochemically distinct from C neoformans. It is endemic to tropical parts of Africa and Australia. Its main environmental sources are eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Eucalyptus tereticornis) and decaying hollows in living trees.17 In addition, there have been reports of isolation of C gattii from insect frass,18 which would make infection by an insect bite a possible transmission route. Worldwide distribution of this pathogen has increased recently, with outbreaks noted on Vancouver Island and in areas in Canada and the northwest United States.7

The true incidence of NF secondary to C gattii is difficult to determine. C gattii was only recently identified as a separate species, and pre-2006 cases of NF attributed to C neoformans may instead have been caused by C gattii. Misidentification has been compounded by the fact that the tests required for accurate diagnosis of C gattii infection may not be readily available in many clinical microbiology laboratories. Cryptococcus can be identified with various methods, including direct microscopy, culturing of tissue or fluid samples, and measurement of cryptococcal serum antigen. However, tests such as specific culture media, mass spectrometry, and molecular typing studies are required to determine cryptococcal species. L-canavanine-glycine-bromothymol blue (CGB) agar is a medium that is often used to differentiate C gattii from C neoformans because of the ability of C gattii to produce a blue appearance.6 Modern techniques, such as MALDI-TOF MS, have also been used to successfully distinguish between C gattii and C neoformans.9 MALDI-TOF MS identifies species on the basis of characteristic protein spectra extracted from whole cells. Using commercial and supplemental reference libraries, the system compares signal matches in the reference spectrum with Cryptococcus entries in the library—allowing rapid and accurate identification of cryptococcal species. However, this diagnostic method is limited by availability of adequate Cryptococcus entries in the reference library and by the high cost of acquiring the machine.

Serotyping is based on the antigenic property of the capsule and was once used to differentiate C neoformans into its 3 main varieties: var. neoformans, var. grubii, var. gattii. However, when it was realized that the antigenic property of the strain can be unstable and that there are hybrids containing more than 1 serotype, serotyping was abandoned as a species-differentiation test.6 The current gold standard for species differentiation is molecular genotyping. Molecular genotyping studies can confirm the diagnosis of C gattii infection and allow differentiation of C gattii into its 4 main molecular types: VGI, VGII, VGIII, VGIV. Using methods such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, molecular typing allows for specific epidemiology charting of C gattii genotypes.7

Although the transmission route for cryptococcal infection is mainly respiratory, direct inoculation has been reported as well.19 Cutaneous lesions, which occur in 5% to 20% of cryptococcal infections, often present in the head and neck.2,20,21 Primary cutaneous infections from cryptococcosis are rare, and cutaneous manifestations are often a sign of disseminated disease. Disseminated disease is defined as the involvement of 2 or more noncontiguous sites or evidence of high fungal burden based on cryptococcal antigen titer of more than 1:512.12 It is important to exclude disseminated disease in all cases of cryptococcosis, as it may be fatal.20 The neural and pulmonary systems should be screened.22 Cellulitis from cryptococcosis is almost always limited to immunocompromised patients, though there are reports of crytococcal cutaneous disease in immunocompetent patients.3,15 Interestingly, though C neoformans often affects immunocompromised patients, the emerging pathogen of C gattii affects immunocompetent patients.7,17,23 Our patient’s undiagnosed diabetes may have been a risk factor for cryptococcal infection. His cryptococcal antigen titer was 1:256, with no evidence of other sites of involvement. We therefore believe this to be a rare case of direct inoculation secondary to an insect bite.

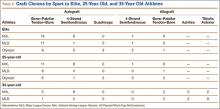

The literature includes 12 reported cases of NF secondary to Cryptococcus (Table 2), all C neoformans. Of these cases, 9 involved immunosuppression, and most of these patients were on long-term steroid treatment after organ transplantation. The most common infection site was the lower extremity. These cases of cryptococcal NF show that immunosuppression, and long-term steroid use in particular, is an important risk factor. The mortality rate for these reviewed cases was 41.6% (5/12). According to the literature, the mortality rates for patients with cryptococcal soft-tissue infections24 and posttransplant patients with cryptococcal NF21 were 37.5% and 60%, respectively. We believe the mortality rate in our reviewed cases likely was confounded by the fact that most of the patients were posttransplant patients on long-term immunosuppression.

Of the 12 patients, 5 had primary cutaneous disease. There seems to be no relationship between outcome and dissemination of disease. In addition, there is a paucity of literature on the effect of disseminated disease and cryptococcal soft-tissue infections. Therefore, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the effects of disseminated disease on severity of cryptococcal soft-tissue infection.

Treatment of cryptococcal NF involves a combination of surgical débridement and long-term antifungal therapy. Surgical débridement of NF includes delineating the extent of infection with complete surgical excision of the affected tissue.25 The aims of surgery should be to remove all unhealthy tissue, identify the offending organism, and plan for resurfacing or reconstruction of the afflicted extremity. Intraoperative-tissue histology should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of NF. Histology can be used to demonstrate cryptococcal infection. The diagnosis of cryptococcal infection can be aided with fungal cultures, and therefore we recommend that tissue cultures be sent not only for routine aerobic/anaerobic bacteria but also for mycobacteria and fungal organisms. Laboratory tests that aid in diagnosis include serum cryptococcal antigen titer.

The current treatment recommendation for cryptococcal disease in patients who are not HIV-positive or transplant hosts is amphotericin B deoxycholate 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/d plus flucytosine 100 mg/kg/d for at least 4 weeks.22 The regimen period may be shortened to 14 days for patients at low risk of treatment failure. Fluconazole should be given as maintenance therapy (200 mg/d) for 6 to 12 months. There is no compelling evidence for immunoglobulin therapy for cryptococcal disease.22

Conclusion

NF caused by Cryptococcus is rare. A high level of suspicion, and intraoperative specimens for histology and fungal microscopy and culture, can help in establishing the diagnosis. Molecular genotyping remains the diagnostic method of choice for NF secondary to Cryptococcus. Effective treatment consists of aggressive surgical débridement and antifungal therapy.

1. Marcus JR, Hussong JW, Gonzalez C, Dumanian GA. Risk factors in necrotizing fasciitis: a case involving Cryptococcus neoformans. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40(1):80-83.

2. Huang KC, Tu YK, Lee KF, Huang TJ, Wen-Wei Hsu R. Disseminated cryptococcosis presented as necrotizing fasciitis of a limb. J Trauma. 2007;63(2):E44-E46.

3. Capoor MR, Khanna G, Malhotra R. Disseminated cryptococcosis with necrotizing fasciitis in an apparently immunocompetent host: a case report. Med Mycol. 2008;46:269-273.

4. Adachi M, Tsurata D, Imanishi H, Ishii M, Kobayashi H. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans in a patient with pemphigus vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e751-e753.

5. Enache-Angoulvant A, Chandenier J, Symoens F, et al. Molecular identification of Cryptococcus neoformans serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(4):1261-1265.

6. Kwon-Chung KJ, Varma A. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6(4):657-687.

7. Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, et al; Cryptococcus gattii Working Group of the Pacific Northwest. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(8):1185-1191.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. McTaggart LR, Lei E, Richardson SE, Hoang L, Fothergill A, Zhang SX. Rapid identification of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(8):3050-3053.

10. Meyer W, Castañeda A, Jackson S, Huynh M, Castañeda E; IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):189-195.

11. Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1454-1460.

12. Giuliano A, Lewis F Jr, Hadley K, Blaisdell FW. Bacteriology of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134(1):52-57.

13. Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotising fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(4):249-257.

14. Buchanan PJ, Mast BA, Lottenberg L, Kim T, Efron PA, Ang DN. Candida albicans necrotizing soft tissue infection: a case report and literature review of fungal necrotizing soft tissue infections. Ann Plastic Surg. 2013;70(6):739-741.

15. Jain D, Kumar Y, Vasishta RK, Rajesh L, Pattari SK, Chakrabarti A. Zygomycotic necrotizing fasciitis in immunocompetent patients: a series of 18 cases. Modern Pathol. 2006;19(9):1221-1226.

16. Fontes RA Jr, Ogilvie CM, Miclau T. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(3):151-158.

17. Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39(2):155-168.

18. Kidd SE, Sorrell TC, Meyer W. Isolation of two molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from insect frass. Med Mycol. 2003;41(2):171-176.

19. Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):337-347.

20. Basaran O, Emiroglu R, Arikan U, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis with multiple sites of involvement in the lower extremities. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(11):1158-1160.

21. Baer S, Baddley JW, Gnann JW, Pappas PG. Cryptococcal disease presenting as necrotizing cellulitis in transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11(4):353-358.

22. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291-322.

23. Chan M, Lye D, Win MK, Chow A, Barkham T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of cryptococcosis in Singapore: predominance of Cryptococcus neoformans compared with Cryptococcus gattii. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:110-115.

24. Gave AA, Torres R, Kaplan L. Cryptococcal myositis and vasculitis: an unusual necrotizing soft tissue infection. Surg Infect. 2004;5(3):309-313.

25. Wong CH, Yam AK, Tan AB, Song C. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196(3):e19-e24.

26. Bégon E, Bachmeyer C, Thibault M, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a diabetic patient with chronic renal insufficiency. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):935-936.

27. Doorenbos-Bot AC, Hooymans JM, Blanksma LJ. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a healthy young man. Doc Ophthalmol. 1990;75(3-4):315-320.

28. Yoneda T, Itami Y, Hirayama A, Saka T, Yoshida K, Fujimoto K. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis in a patient after renal transplantation—a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(2):620-622.

1. Marcus JR, Hussong JW, Gonzalez C, Dumanian GA. Risk factors in necrotizing fasciitis: a case involving Cryptococcus neoformans. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40(1):80-83.

2. Huang KC, Tu YK, Lee KF, Huang TJ, Wen-Wei Hsu R. Disseminated cryptococcosis presented as necrotizing fasciitis of a limb. J Trauma. 2007;63(2):E44-E46.

3. Capoor MR, Khanna G, Malhotra R. Disseminated cryptococcosis with necrotizing fasciitis in an apparently immunocompetent host: a case report. Med Mycol. 2008;46:269-273.

4. Adachi M, Tsurata D, Imanishi H, Ishii M, Kobayashi H. Necrotizing fasciitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans in a patient with pemphigus vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):e751-e753.

5. Enache-Angoulvant A, Chandenier J, Symoens F, et al. Molecular identification of Cryptococcus neoformans serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(4):1261-1265.

6. Kwon-Chung KJ, Varma A. Do major species concepts support one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6(4):657-687.

7. Datta K, Bartlett KH, Baer R, et al; Cryptococcus gattii Working Group of the Pacific Northwest. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii into Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(8):1185-1191.

8. Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1535-1541.

9. McTaggart LR, Lei E, Richardson SE, Hoang L, Fothergill A, Zhang SX. Rapid identification of Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(8):3050-3053.

10. Meyer W, Castañeda A, Jackson S, Huynh M, Castañeda E; IberoAmerican Cryptococcal Study Group. Molecular typing of IberoAmerican Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(2):189-195.

11. Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(8):1454-1460.

12. Giuliano A, Lewis F Jr, Hadley K, Blaisdell FW. Bacteriology of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134(1):52-57.

13. Morgan MS. Diagnosis and management of necrotising fasciitis: a multiparametric approach. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(4):249-257.

14. Buchanan PJ, Mast BA, Lottenberg L, Kim T, Efron PA, Ang DN. Candida albicans necrotizing soft tissue infection: a case report and literature review of fungal necrotizing soft tissue infections. Ann Plastic Surg. 2013;70(6):739-741.

15. Jain D, Kumar Y, Vasishta RK, Rajesh L, Pattari SK, Chakrabarti A. Zygomycotic necrotizing fasciitis in immunocompetent patients: a series of 18 cases. Modern Pathol. 2006;19(9):1221-1226.

16. Fontes RA Jr, Ogilvie CM, Miclau T. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(3):151-158.

17. Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii. Med Mycol. 2001;39(2):155-168.

18. Kidd SE, Sorrell TC, Meyer W. Isolation of two molecular types of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii from insect frass. Med Mycol. 2003;41(2):171-176.

19. Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, Dupont B, Ronin O, Lortholary O; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(3):337-347.

20. Basaran O, Emiroglu R, Arikan U, Karakayali H, Haberal M. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis with multiple sites of involvement in the lower extremities. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(11):1158-1160.

21. Baer S, Baddley JW, Gnann JW, Pappas PG. Cryptococcal disease presenting as necrotizing cellulitis in transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2009;11(4):353-358.

22. Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(3):291-322.

23. Chan M, Lye D, Win MK, Chow A, Barkham T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of cryptococcosis in Singapore: predominance of Cryptococcus neoformans compared with Cryptococcus gattii. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;26:110-115.

24. Gave AA, Torres R, Kaplan L. Cryptococcal myositis and vasculitis: an unusual necrotizing soft tissue infection. Surg Infect. 2004;5(3):309-313.

25. Wong CH, Yam AK, Tan AB, Song C. Approach to debridement in necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 2008;196(3):e19-e24.

26. Bégon E, Bachmeyer C, Thibault M, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a diabetic patient with chronic renal insufficiency. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(8):935-936.

27. Doorenbos-Bot AC, Hooymans JM, Blanksma LJ. Periorbital necrotising fasciitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans in a healthy young man. Doc Ophthalmol. 1990;75(3-4):315-320.

28. Yoneda T, Itami Y, Hirayama A, Saka T, Yoshida K, Fujimoto K. Cryptococcal necrotizing fasciitis in a patient after renal transplantation—a case report. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(2):620-622.

Functional Knee Outcomes in Infrapatellar and Suprapatellar Tibial Nailing: Does Approach Matter?

With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

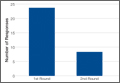

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results

We identified 176 patients who had the CPT code for intramedullary fixation of a tibial shaft fracture between January 2009 and February 2013. After analysis of radiographs and medical records, 82 patients met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-six (45%) of the original 82 patients were lost to follow-up after attempts to contact them by telephone. One patient refused to participate in the study. Twenty-four patients underwent traditional infrapatellar nailing, and 21 patients had a suprapatellar nail placed with approach-specific instrumentation. Nine patients had an open fracture. There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of sex, age, BMI, mechanism of injury, or operative time (Table 1). There was also no difference (P = .210) in fracture location between groups (0 proximal-third, 14 midshaft, 10 distal-third vs 3 proximal-third, 10 midshaft, 8 distal-third). Mean age was 37.6 years (range, 20-65 years) for the infrapatellar group and 38.5 years (range, 18-68 years) for the suprapatellar group (P = .839). Mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) shorter for the suprapatellar group (12 mo; range, 3-33 mo) than for the infrapatellar group (25 mo; range, 4-43 mo).

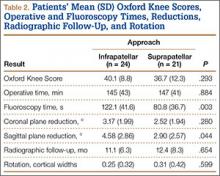

Mean OKS (maximum, 48 points) was 40.1 (range, 11-48) for the infrapatellar group and 36.7 (range, 2-48) for the suprapatellar group (P = .293). Table 2 summarizes the data. Radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane was improved (P = .044) in the suprapatellar group (2.90°) compared with the infrapatellar group (4.58°). There was no difference in rotational malreduction (0.31 vs 0.25 cortical width; P = .599) or in reduction in the coronal plane (2.52° vs 3.17°; P = .280). All patients in both groups maintained radiographic reduction within 5° in any plane throughout follow-up. There was no difference (P = .654) in radiographic follow-up between the infrapatellar group (11 mo) and the suprapatellar group (12 mo). The 1 nonunion in the suprapatellar group required return to the operating room for exchange intramedullary nailing. The suprapatellar approach required less (P = .003) operative fluoroscopy time (80.8 s; range, 46-180 s) than the standard infrapatellar approach (122.1 s; range, 71-240 s). Two patients in the suprapatellar group and 8 in the infrapatellar group did not have their fluoroscopy time recorded in the operative report.

Discussion

We have described the first retrospective cohort-comparison study of functional knee scores associated with traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing. Although much has been written about the incidence of anterior knee pain with use of a patellar splitting or parapatellar approach, the clinical effects of knee pain after use of suprapatellar nails are yet to be addressed. In a cadaveric study, Gelbke and colleagues14 found higher mean patellofemoral pressures and higher peak contact pressures with a suprapatellar approach. These numbers, however, were still far below the threshold for chondrocyte damage, and that study is yet to be clinically validated. Our data showed no difference in OKS between the 2 groups. Despite being intra-articular, approach-specific instrumentation may protect the trochlea and patellar cartilage.

Although the OKS questionnaire was originally developed and widely validated to describe clinical outcomes of total knee arthroplasty,15,16 it has also been evaluated for other interventions, including viscosupplementation injections17 and high tibial osteotomy.18 We used the OKS questionnaire in our study because it is simple to administer by telephone and is not as cumbersome as the Knee Society Score or the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. It is also more specific to the knee than generalized outcome measures used in trauma, such as the Short Form 36 (SF-36). Sanders and colleagues19 reported excellent tibial alignment, radiographic union, and knee range of motion using semi-extended tibial nailing with a suprapatellar approach. For outcome measures, they used the Lysholm Knee Score and the SF-36. Our clinical and radiographic results confirmed their finding—that the semi-extended suprapatellar approach is an option for tibial nailing.

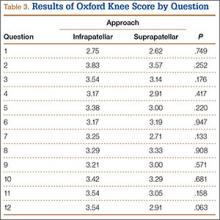

OKS results by question (Table 3) showed that the infrapatellar group had less pain walking down stairs. This result approached statistical significance (P = .063). As surgeons at our institution began using the suprapatellar approach only during the final 2 years of the study period, mean follow-up was significantly (P < .001) less than for the infrapatellar group (12 vs 25 mo). Although there was no statistically significant difference in reduction quality on anteroposterior radiographs, the suprapatellar approach had improved (P = .044) reduction on lateral radiographs (2.90° vs 4.58°).

Although operative time did not differ between our 2 groups, significantly (P = .003) less fluoroscopy time was required for suprapatellar nails (80.8 s) than for infrapatellar nails (122.1 s). Positioning the knee in the semi-extended position offers easier access for fluoroscopy and less radiation exposure for the patient. Placing the nail in extension also helps eliminate the deforming forces that cause malreduction of proximal tibial shaft or segmental fractures. However, our study was limited in that only 2 surgeons at our institution used the suprapatellar approach, and both were fellowship-trained in orthopedic traumatology. This situation could have introduced bias into the interpretation of fluoroscopy data, as these surgeons may have been more comfortable with the procedure and less likely to use fluoroscopy. Both surgeons also performed infrapatellar nailing during the study period, and there was no statistical difference in fracture patterns between the groups, thus minimizing bias.

This study was retrospective but had several strengths. Sample size met the prestudy power analysis to determine a minimally clinically important difference in OKS results. The investigator who administered the telephone survey was blinded to surgical approach. This study was also the first clinical study to compare outcomes of infrapatellar and suprapatellar nailing. However, the study’s follow-up rate was a weakness. The patient population at our academic, urban, level I trauma center is transient. We lost 36 patients (45%) to follow-up; their telephone numbers in the hospital records likely changed since surgery, and we could not contact these patients.

Conclusion

Our retrospective cohort study found no difference in OKS between traditional infrapatellar nailing and suprapatellar nailing for diaphyseal tibia fractures. Suprapatellar nails require less fluoroscopy time and may show improved radiographic reduction in the sagittal plane. Although further study is needed, the suprapatellar entry portal appears to be a safe alternative for tibial nailing with use of appropriate instrumentation.

1. Praemer A, Furner S, Rice DP. Musculoskeletal Conditions in the United States. Park Ridge, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1992.

2. Bone LB, Sucato D, Stegemann PM, Rohrbacher BJ. Displaced isolated fractures of the tibial shaft treated with either a cast or intramedullary nailing. An outcome analysis of matched pairs of patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(9):1336-1341.

3. Hooper GJ, Keddell RG, Penny ID. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(1):83-85.

4. Alho A, Benterud JG, Høgevold HE, Ekeland A, Strømsøe K. Comparison of functional bracing and locked intramedullary nailing in the treatment of displaced tibial shaft fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(277):243-250.

5. Ricci WM, O’Boyle M, Borrelli J, Bellabarba C, Sanders R. Fractures of the proximal third of the tibial shaft treated with intramedullary nails and blocking screws. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15(4):264-270.

6. Tornetta P 3rd, Collins E. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(328):185-189.

7. Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(2):103-105.

8. Toivanen JA, Väistö O, Kannus P, Latvala K, Honkonen SE, Järvinen MJ. Anterior knee pain after intramedullary nailing of fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study comparing two different nail-insertion techniques. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(4):580-585.

9. Morandi M, Banka T, Gairarsa GP, et al. Intramedullary nailing of tibial fractures: review of surgical techniques and description of a percutaneous lateral suprapatellar approach. Orthopaedics. 2010;33(3):172-179.

10. Bohm ER, Loucks L, Tan QE, et al. Determining minimum clinically important difference and targeted clinical improvement values for the Oxford 12. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2012; San Francisco, CA.

11. Dupont WD, Plummer WD Jr. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11(2):116-128.

12. Streit MR, Walker T, Bruckner T, et al. Mobile-bearing lateral unicompartmental knee replacement with the Oxford domed tibial component: an independent series. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(10):1356-1361.

13. Jenny JY, Diesinger Y. The Oxford Knee Score: compared performance before and after knee replacement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98(4):409-412.

14. Gelbke MK, Coombs D, Powell S, et al. Suprapatellar versus infra-patellar intramedullary nail insertion of the tibia: a cadaveric model for comparison of patellofemoral contact pressures and forces. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(11):665-671.

15. Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Murray D, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(1):63-69.

16. Dunbar MJ, Robertsson O, Ryd L, Lidgren L. Translation and validation of the Oxford-12 item knee score for use in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):268-274.

17. Clarke S, Lock V, Duddy J, Sharif M, Newman JH, Kirwan JR. Intra-articular hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc) in the management of patellofemoral osteoarthritis of the knee (POAK). Knee. 2005;12(1):57-62.

18. Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(382):154-167.

19. Sanders RW, DiPasquale TG, Jordan CJ, Arrington JA, Sagi HC. Semiextended intramedullary nailing of the tibia using a suprapatellar approach: radiographic results and clinical outcomes at a minimum of 12 months follow-up. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(suppl 8):S29-S39.

With an incidence of 75,000 per year in the United States alone, fractures of the tibial shaft are among the most common long-bone fractures.1 Diaphyseal tibial fractures present a unique treatment challenge because of complications, including nonunion, malunion, and the potential for an open injury. Intramedullary fixation of these fractures has long been the standard of care, allowing for early mobilization, shorter time to weight-bearing, and high union rates.2-4

The classic infrapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing involves placing the knee in hyperflexion over a bump or radiolucent triangle and inserting the nail through a longitudinal incision in line with the fibers of the patellar tendon. Deforming muscle forces often cause proximal-third tibial fractures and segmental fractures to fall into valgus and procurvatum. To counter these deforming forces, orthopedic surgeons have used some novel surgical approaches, including use of blocking screws5 and a parapatellar approach that could be used with the knee in semi-extended position.6 Anterior knee pain has been reported as a common complication of tibial nailing (reported incidence, 56%).7 In a prospective randomized controlled study, Toivanen and colleagues8 found no difference in incidence of knee pain between patellar tendon splitting and parapatellar approaches.

Techniques have been developed to insert the nail through a semi-extended suprapatellar approach to facilitate intraoperative imaging, allow easier access to starting-site position, and counter deforming forces. Although outcomes of traditional infrapatellar nailing have been well documented, there is a paucity of literature on outcomes of using a suprapatellar approach. Splitting the quadriceps tendon causes scar tissue to form superior to the patella versus the anterior knee, which may reduce flexion-related pain or kneeling pain.9 The infrapatellar nerve is also well protected with this approach.

We conducted a study to determine differences in functional knee pain in patients who underwent either traditional infrapatellar nailing or suprapatellar nailing. We hypothesized that there would be no difference in functional knee scores between these approaches and that, when compared with the infrapatellar approach, the suprapatellar approach would result in improved postoperative reduction and reduced intraoperative fluoroscopy time.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by our institutional review board. We searched our level I trauma center’s database for Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 27759 to identify all patients who had a tibial shaft fracture fixed with an intramedullary implant between January 2009 and February 2013. Radiographs, operative reports, and inpatient records were reviewed. Patients older than 18 years at time of injury and patients with an isolated tibial shaft fracture (Orthopaedic Trauma Association type 42 A-C) surgically fixed with an intramedullary nail through either a traditional infrapatellar approach or a suprapatellar approach were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were required fasciotomy, Gustilo type 3B or 3C open fracture, prior knee surgery, additional orthopedic injury, and preexisting radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease.

In addition to surgical approach, demographic data, including body mass index (BMI), age, sex, and mechanism of injury, were documented from the medical record. Each patient was contacted by telephone by an investigator blinded to surgical exposure, and the 12-item Oxford Knee Score (OKS) questionnaire was administered (Figure). Operative time, quality of reduction on postoperative radiographs, and intraoperative fluoroscopy time were compared between the 2 approaches. We determined quality of reduction by measuring the angle between the line perpendicular to the tibial plateau and plafond on both the anteroposterior and lateral postoperative radiographs. Rotation was determined by measuring displacement of the fracture by cortical widths. The infrapatellar and suprapatellar groups were statistically analyzed with an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test. Categorical variables between groups were analyzed with the χ2 test or, when expected values in a cell were less than 5, the Fisher exact test.

We then conducted an a priori power analysis to determine the appropriate sample size. To detect the reported minimally clinically important difference in the OKS of 5.2,10 estimating an approximate 20% larger patient population in the infrapatellar group, we would need to enroll 24 infrapatellar patients and 20 suprapatellar patients to achieve a power of 0.80 with a type I error rate of 0.05.11 This analysis is also based on an estimated OKS standard deviation of 6, which has been reported in several studies.12,13

Results