User login

Total Knee Arthroplasty in Hemophilic Arthropathy

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

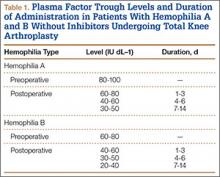

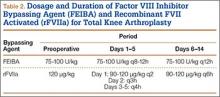

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Prosthetic survival rates with implant removal for any reason regarded as final endpoint was 92%. Causes of failure were prosthetic infection (6 cases, 6.8%) and loosening (2 cases, 2.2%). Of the 6 prosthetic infections, 5 were regarded as late and 1 as early. Late infections were successfully sorted by performing 2-stage revision TKA with the Constrained Condylar Knee (Zimmer). Acute infections were managed by open joint débridement and polyethylene exchange. Both cases of aseptic loosening of the TKA were successfully managed with 1-stage revision TKA using the same implant model (Figures 2A–2D).

Mean KSS Knee score improved from 79 before surgery to 36 after surgery, and mean KSS Function score improved from 63 to 33. KSS Pain score, which is included in the Knee score, 0 (no pain) to 50 (most severe pain), improved from 47 to 8. Patients receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-positive did not have poorer outcomes relative to those of patients not receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-negative. Patients with liver cirrhosis had a lower prosthetic survival rate and lower Knee scores.

Discussion

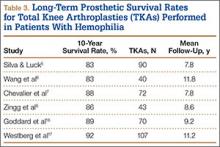

The prosthetic survival rate found in this study compares well with other reported rates for patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. However, evidence regarding long-term prosthesis survival in TKAs performed for patients with hemophilia is limited. Table 3 summarizes the main reported series of patients with hemophilia with 10-year prosthetic survival rates, number of TKAs performed, and mean follow-up period; in all these series, implant removal for any reason was regarded as the final endpoint.5-8,16,17 Mean follow-up in our study was 8 years. Clinical outcomes of TKA in patients with severe hemophilia and related disorders are expected to be inferior to those achieved in patients without a bleeding condition. The overall 10-year prosthetic survival rate for cemented TKA implants, as reported by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, was on the order of 93%.18 Mean age of our patients at time of surgery was only 38.2 years. TKAs performed in younger patients without a bleeding disorder have been associated with shorter implant survival times relative to those of elderly patients.19 Thus, Diduch and colleagues20 reported a prosthetic survival rate of 87% at 18 years in 108 TKAs performed on patients under age 55 years. Lonner and colleagues21 reported a better implant survival rate (90% at 8 years) in a series of patients under age 40 years (32 TKAs). In a study by Duffy and colleagues,22 the implant survival rate was 85% at 15 years in patients under age 55 years (74 TKAs). The results from our retrospective case assessment are quite similar to the overall prosthetic survival rates reported for TKAs performed on patients without hemophilia.

Rates of periprosthetic infection after primary TKA in patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions are much higher (up to 11%), with a mean infection rate of 6.2% (range, 1% to 11%), consistent with the rate found in our series of patients (6.8%)7,16,17,23,24 (Table 4). This rate is much higher than that reported after primary TKA in patients without hemophilia but is similar to some rates reported for patients with hemophilia. In our experience, most periprosthetic infections (5/6) were sorted as late.

Late infection is a major concern after TKA in patients with hemophilia, and various factors have been hypothesized as contributing to the high prevalence. An important factor is the high rate of HIV-positive patients among patients with hemophilia—which acts as a strong predisposing factor because of the often low CD4 counts and associated immune deficiency,25 but different reports have provided conflicting results in this respect.5,6,12 We found no relationship between HIV status and risk for periprosthetic infection, but conclusions are limited by the low number of HIV-positive patients in our series (14/74, 18.9%). Our patients’ late periprosthetic infections were diagnosed several years after TKA, suggesting hematogenous spread of infection. Most of these patients either were on regular prophylactic factor infusions or were being treated on demand, which might entail a risk for contamination of infusions by skin bacteria from the puncture site. Therefore, having an aseptic technique for administering coagulation factor concentrates is of paramount importance for patients with hemophilia and a knee implant.

Another important complication of TKA surgery is aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Aseptic loosening occurred in 2.2% of our patients, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere.11,26 Rates of this complication increase over follow-up, and some authors have linked this complication to TKA polyethylene wear.27 Development of a reactive and destructive bone–cement interface and microhemorrhages into such interface might be implicated in the higher rate of loosening observed among patients with hemophilia.28

In the present study, preoperative and postoperative functional outcomes differed significantly. A modest postoperative total ROM of 69º to 79º has been reported by several authors.5,6 Postoperative ROM may vary—may be slightly increased, remain unchanged, or may even be reduced.4,23,26 Even though little improvement in total ROM is achieved after TKA, many authors have reported reduced flexion contracture and hence an easier gait. However, along with functional improvement, dramatic pain relief after TKA is perhaps the most remarkable aspect, and it has a strong effect on patient satisfaction after surgery.5,7,8,18,23

Our study had 2 main limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series evaluation with the usual issues of potential inaccuracy of medical records and information bias. Second, the study did not include a control group.

Conclusion

The primary TKAs performed in our patients with hemophilia have had a good prosthetic survival rate. Even though such a result is slightly inferior to results in patients without hemophilia, our prosthetic survival rate is not significantly different from the rates reported in other, younger patient subsets. Late periprosthetic infections are a major concern, and taking precautions to avoid hematogenous spread of infections during factor concentrate infusions is strongly encouraged.

1. Arnold WD, Hilgartner MW. Hemophilic arthropathy. Current concepts of pathogenesis and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(3):287-305.

2. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Common orthopaedic problems in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 1999;5(suppl 1):53-60.

3. Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Glomstein A, et al. On-demand vs. prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia in Norway and Sweden: differences in treatment characteristics and outcome. Haemophilia. 2003;9(5):555-566.

4. Teigland JC, Tjønnfjord GE, Evensen SA, Charania B. Knee arthroplasty in hemophilia. 5-12 year follow-up of 15 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(2):153-156.

5. Silva M, Luck JV Jr. Long-term results of primary total knee replacement in patients with hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):85-91.

6. Wang K, Street A, Dowrick A, Liew S. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction following total joint replacement in haemophilia—23-year experience in knees, hips and elbows. Haemophilia. 2012;18(1):86-93.

7. Chevalier Y, Dargaud Y, Lienhart A, Chamouard V, Negrier C. Seventy-two total knee arthroplasties performed in patients with haemophilia using continuous infusion. Vox Sang. 2013;104(2):135-143.

8. Zingg PO, Fucentese SF, Lutz W, Brand B, Mamisch N, Koch PP. Haemophilic knee arthropathy: long-term outcome after total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(12):2465-2470.

9. Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Christiansen SE, Ingerslev J, Sneppen O. Total knee arthroplasty in classic hemophilia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(256):137-146.

10. Cohen I, Heim M, Martinowitz U, Chechick A. Orthopaedic outcome of total knee replacement in haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2000;6(2):104-109.

11. Fehily M, Fleming P, O’Shea E, Smith O, Smyth H. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with severe haemophilia. Int Orthop. 2002;26(2):89-91.

12. Legroux-Gérot I, Strouk G, Parquet A, Goodemand J, Gougeon F, Duquesnoy B. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(1):22-32.

13. Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):56-60.

14. Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):13-14.

15. Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(10):1434-1445.

16. Goddard NJ, Mann HA, Lee CA. Total knee replacement in patients with end-stage haemophilic arthropathy. 25-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(8):1085-1089.

17. Westberg M, Paus AC, Holme PA, Tjønnfjord GE. Haemophilic arthropathy: long-term outcomes in 107 primary total knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2014;21(1):147-150.

18. Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Failure of total knee arthroplasty with or without patella resurfacing. A study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register with 0-15 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):282-292.

19. Post M, Telfer MC. Surgery in hemophilic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(8):1136-1145.

20. Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients. Long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(4):575-582.

21. Lonner JH, Hershman S, Mont M, Lotke PA. Total knee arthroplasty in patients 40 years of age and younger with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(380):85-90.

22. Duffy GP, Crowder AR, Trousdale RR, Berry DJ. Cemented total knee arthroplasty using a modern prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):67-70.

23. Chiang CC, Chen PQ, Shen MC, Tsai W. Total knee arthroplasty for severe haemophilic arthropathy: long-term experience in Taiwan. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):828-834.

24. Solimeno LP, Mancuso ME, Pasta G, Santagostino E, Perfetto S, Mannucci PM. Factors influencing the long-term outcome of primary total knee replacement in haemophiliacs: a review of 116 procedures at a single institution. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(2):227-234.

25. Jämsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):87-92.

26. Ragni MV, Crossett LS, Herndon JH. Postoperative infection following orthopaedic surgery in human immunodeficiency virus–infected hemophiliacs with CD4 counts < or = 200/mm3. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):716-721.

27. Hicks JL, Ribbans WJ, Buzzard B, et al. Infected joint replacements in HIV-positive patients with haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1050-1054.

28. Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Heiple KG, Sobel M. Total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):98-107.

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Prosthetic survival rates with implant removal for any reason regarded as final endpoint was 92%. Causes of failure were prosthetic infection (6 cases, 6.8%) and loosening (2 cases, 2.2%). Of the 6 prosthetic infections, 5 were regarded as late and 1 as early. Late infections were successfully sorted by performing 2-stage revision TKA with the Constrained Condylar Knee (Zimmer). Acute infections were managed by open joint débridement and polyethylene exchange. Both cases of aseptic loosening of the TKA were successfully managed with 1-stage revision TKA using the same implant model (Figures 2A–2D).

Mean KSS Knee score improved from 79 before surgery to 36 after surgery, and mean KSS Function score improved from 63 to 33. KSS Pain score, which is included in the Knee score, 0 (no pain) to 50 (most severe pain), improved from 47 to 8. Patients receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-positive did not have poorer outcomes relative to those of patients not receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-negative. Patients with liver cirrhosis had a lower prosthetic survival rate and lower Knee scores.

Discussion

The prosthetic survival rate found in this study compares well with other reported rates for patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. However, evidence regarding long-term prosthesis survival in TKAs performed for patients with hemophilia is limited. Table 3 summarizes the main reported series of patients with hemophilia with 10-year prosthetic survival rates, number of TKAs performed, and mean follow-up period; in all these series, implant removal for any reason was regarded as the final endpoint.5-8,16,17 Mean follow-up in our study was 8 years. Clinical outcomes of TKA in patients with severe hemophilia and related disorders are expected to be inferior to those achieved in patients without a bleeding condition. The overall 10-year prosthetic survival rate for cemented TKA implants, as reported by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, was on the order of 93%.18 Mean age of our patients at time of surgery was only 38.2 years. TKAs performed in younger patients without a bleeding disorder have been associated with shorter implant survival times relative to those of elderly patients.19 Thus, Diduch and colleagues20 reported a prosthetic survival rate of 87% at 18 years in 108 TKAs performed on patients under age 55 years. Lonner and colleagues21 reported a better implant survival rate (90% at 8 years) in a series of patients under age 40 years (32 TKAs). In a study by Duffy and colleagues,22 the implant survival rate was 85% at 15 years in patients under age 55 years (74 TKAs). The results from our retrospective case assessment are quite similar to the overall prosthetic survival rates reported for TKAs performed on patients without hemophilia.

Rates of periprosthetic infection after primary TKA in patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions are much higher (up to 11%), with a mean infection rate of 6.2% (range, 1% to 11%), consistent with the rate found in our series of patients (6.8%)7,16,17,23,24 (Table 4). This rate is much higher than that reported after primary TKA in patients without hemophilia but is similar to some rates reported for patients with hemophilia. In our experience, most periprosthetic infections (5/6) were sorted as late.

Late infection is a major concern after TKA in patients with hemophilia, and various factors have been hypothesized as contributing to the high prevalence. An important factor is the high rate of HIV-positive patients among patients with hemophilia—which acts as a strong predisposing factor because of the often low CD4 counts and associated immune deficiency,25 but different reports have provided conflicting results in this respect.5,6,12 We found no relationship between HIV status and risk for periprosthetic infection, but conclusions are limited by the low number of HIV-positive patients in our series (14/74, 18.9%). Our patients’ late periprosthetic infections were diagnosed several years after TKA, suggesting hematogenous spread of infection. Most of these patients either were on regular prophylactic factor infusions or were being treated on demand, which might entail a risk for contamination of infusions by skin bacteria from the puncture site. Therefore, having an aseptic technique for administering coagulation factor concentrates is of paramount importance for patients with hemophilia and a knee implant.

Another important complication of TKA surgery is aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Aseptic loosening occurred in 2.2% of our patients, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere.11,26 Rates of this complication increase over follow-up, and some authors have linked this complication to TKA polyethylene wear.27 Development of a reactive and destructive bone–cement interface and microhemorrhages into such interface might be implicated in the higher rate of loosening observed among patients with hemophilia.28

In the present study, preoperative and postoperative functional outcomes differed significantly. A modest postoperative total ROM of 69º to 79º has been reported by several authors.5,6 Postoperative ROM may vary—may be slightly increased, remain unchanged, or may even be reduced.4,23,26 Even though little improvement in total ROM is achieved after TKA, many authors have reported reduced flexion contracture and hence an easier gait. However, along with functional improvement, dramatic pain relief after TKA is perhaps the most remarkable aspect, and it has a strong effect on patient satisfaction after surgery.5,7,8,18,23

Our study had 2 main limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series evaluation with the usual issues of potential inaccuracy of medical records and information bias. Second, the study did not include a control group.

Conclusion

The primary TKAs performed in our patients with hemophilia have had a good prosthetic survival rate. Even though such a result is slightly inferior to results in patients without hemophilia, our prosthetic survival rate is not significantly different from the rates reported in other, younger patient subsets. Late periprosthetic infections are a major concern, and taking precautions to avoid hematogenous spread of infections during factor concentrate infusions is strongly encouraged.

Chronic hemophilic arthropathy, a well-known complication of hemophilia, develops as a long-term consequence of recurrent joint bleeds resulting in synovial hypertrophy (chronic proliferative synovitis) and joint cartilage destruction. Hemophilic arthropathy mostly affects the knees, ankles, and elbows and causes chronic joint pain and functional impairment in relatively young patients who have not received adequate primary prophylactic replacement therapy with factor concentrates from early childhood.1-3

In the late stages of hemophilic arthropathy of the knee, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) provides dramatic joint pain relief, improves knee functional status, and reduces rebleeding into the joint.4-8 TKA performed on a patient with hemophilia was first reported in the mid-1970s.9,10 In these cases, the surgical procedure itself is often complicated by severe fibrosis developing in the joint soft tissues, flexion joint contracture, and poor quality of the joint bone structures. Even though TKA significantly reduces joint pain in patients with chronic hemophilic arthropathy, some authors have achieved only modest functional outcomes and experienced a high rate of complications (infection, prosthetic loosening).11-13 Data on TKA outcomes are still scarce, and most studies have enrolled a limited number of patients.

We retrospectively evaluated the outcomes of 88 primary TKAs performed on patients with severe hemophilia at a single institution. Clinical outcomes and complications were assessed with a special focus on prosthetic survival and infection.

Patients and Methods

Ninety-one primary TKAs were performed in 77 patients with severe hemophilia A and B (factor VIII [FVIII] and factor IX plasma concentration, <1% each) between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2011, and the medical records of all these patients were thoroughly reviewed in 2013. The cases of 3 patients who died shortly after surgery were excluded from analysis. Thus, 88 TKAs and 74 patients (74 males) were finally available for evaluation. Fourteen patients underwent bilateral TKAs but none concurrently. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of their outcomes.

We recorded demographic data, type and severity of hemophilia, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and Knee Society Scale (KSS) scores.14 KSS scores include Knee score (pain, range of motion [ROM], stability) and Function score (walking, stairs), both of which range from 0 (normal knee) to 100 (most affected knee). Prosthetic infection was classified (Segawa and colleagues15) as early or late, depending on timing of symptom onset (4 weeks after replacement surgery was the threshold used).

Patients received an intravenous bolus infusion of the deficient factor concentrate followed by continuous infusion to reach a plasma factor level of 100% just before surgery and during the first 7 postoperative days and 50% over the next 7 days (Table 1). Patients with a circulating inhibitor (3 overall) received bypassing agents FEIBA (FVIII inhibitor bypassing agent) or rFVIIa (recombinant factor VII activated) (Table 2). Patients were not given any antifibrinolytic treatment or thromboprophylaxis.

Surgery was performed in a standard surgical room. Patients were placed on the operating table in decubitus supinus position. A parapatellar medial incision was made on a bloodless surgical field (achieved with tourniquet ischemia). The prosthesis model used was always the cemented (gentamicin bone cement) NexGen (Zimmer). Patellar resurfacing was done in all cases (Figures 1A–1D). All TKAs were performed by Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán. Intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis was administered at anesthetic induction and during the first 48 hours after surgery (3 further doses). Active exercises were started on postoperative day 1. Joint load aided with 2 crutches was allowed starting on postoperative day 2.

Mean patient age was 38.2 years (range, 24-73 years). Of the 74 patients, 55 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia A, and 19 had a diagnosis of severe hemophilia B. During the follow-up period, 23 patients died (mean time, 6.4 years; range, 4-9 years). Causes of death were acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), liver cirrhosis, and intracranial bleeding. Mean follow-up for the full series of patients was 8 years (range, 1-13 years).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed with SPSS Windows Version 18.0. Prosthetic failure was regarded as implant removal for any reason. Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and either χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. P < .05 (2-sided) was considered significant.

Results

Prosthetic survival rates with implant removal for any reason regarded as final endpoint was 92%. Causes of failure were prosthetic infection (6 cases, 6.8%) and loosening (2 cases, 2.2%). Of the 6 prosthetic infections, 5 were regarded as late and 1 as early. Late infections were successfully sorted by performing 2-stage revision TKA with the Constrained Condylar Knee (Zimmer). Acute infections were managed by open joint débridement and polyethylene exchange. Both cases of aseptic loosening of the TKA were successfully managed with 1-stage revision TKA using the same implant model (Figures 2A–2D).

Mean KSS Knee score improved from 79 before surgery to 36 after surgery, and mean KSS Function score improved from 63 to 33. KSS Pain score, which is included in the Knee score, 0 (no pain) to 50 (most severe pain), improved from 47 to 8. Patients receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-positive did not have poorer outcomes relative to those of patients not receiving inhibitors and patients who were HIV- or HCV-negative. Patients with liver cirrhosis had a lower prosthetic survival rate and lower Knee scores.

Discussion

The prosthetic survival rate found in this study compares well with other reported rates for patients with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. However, evidence regarding long-term prosthesis survival in TKAs performed for patients with hemophilia is limited. Table 3 summarizes the main reported series of patients with hemophilia with 10-year prosthetic survival rates, number of TKAs performed, and mean follow-up period; in all these series, implant removal for any reason was regarded as the final endpoint.5-8,16,17 Mean follow-up in our study was 8 years. Clinical outcomes of TKA in patients with severe hemophilia and related disorders are expected to be inferior to those achieved in patients without a bleeding condition. The overall 10-year prosthetic survival rate for cemented TKA implants, as reported by the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, was on the order of 93%.18 Mean age of our patients at time of surgery was only 38.2 years. TKAs performed in younger patients without a bleeding disorder have been associated with shorter implant survival times relative to those of elderly patients.19 Thus, Diduch and colleagues20 reported a prosthetic survival rate of 87% at 18 years in 108 TKAs performed on patients under age 55 years. Lonner and colleagues21 reported a better implant survival rate (90% at 8 years) in a series of patients under age 40 years (32 TKAs). In a study by Duffy and colleagues,22 the implant survival rate was 85% at 15 years in patients under age 55 years (74 TKAs). The results from our retrospective case assessment are quite similar to the overall prosthetic survival rates reported for TKAs performed on patients without hemophilia.

Rates of periprosthetic infection after primary TKA in patients with hemophilia and other bleeding conditions are much higher (up to 11%), with a mean infection rate of 6.2% (range, 1% to 11%), consistent with the rate found in our series of patients (6.8%)7,16,17,23,24 (Table 4). This rate is much higher than that reported after primary TKA in patients without hemophilia but is similar to some rates reported for patients with hemophilia. In our experience, most periprosthetic infections (5/6) were sorted as late.

Late infection is a major concern after TKA in patients with hemophilia, and various factors have been hypothesized as contributing to the high prevalence. An important factor is the high rate of HIV-positive patients among patients with hemophilia—which acts as a strong predisposing factor because of the often low CD4 counts and associated immune deficiency,25 but different reports have provided conflicting results in this respect.5,6,12 We found no relationship between HIV status and risk for periprosthetic infection, but conclusions are limited by the low number of HIV-positive patients in our series (14/74, 18.9%). Our patients’ late periprosthetic infections were diagnosed several years after TKA, suggesting hematogenous spread of infection. Most of these patients either were on regular prophylactic factor infusions or were being treated on demand, which might entail a risk for contamination of infusions by skin bacteria from the puncture site. Therefore, having an aseptic technique for administering coagulation factor concentrates is of paramount importance for patients with hemophilia and a knee implant.

Another important complication of TKA surgery is aseptic loosening of the prosthesis. Aseptic loosening occurred in 2.2% of our patients, but higher rates have been reported elsewhere.11,26 Rates of this complication increase over follow-up, and some authors have linked this complication to TKA polyethylene wear.27 Development of a reactive and destructive bone–cement interface and microhemorrhages into such interface might be implicated in the higher rate of loosening observed among patients with hemophilia.28

In the present study, preoperative and postoperative functional outcomes differed significantly. A modest postoperative total ROM of 69º to 79º has been reported by several authors.5,6 Postoperative ROM may vary—may be slightly increased, remain unchanged, or may even be reduced.4,23,26 Even though little improvement in total ROM is achieved after TKA, many authors have reported reduced flexion contracture and hence an easier gait. However, along with functional improvement, dramatic pain relief after TKA is perhaps the most remarkable aspect, and it has a strong effect on patient satisfaction after surgery.5,7,8,18,23

Our study had 2 main limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series evaluation with the usual issues of potential inaccuracy of medical records and information bias. Second, the study did not include a control group.

Conclusion

The primary TKAs performed in our patients with hemophilia have had a good prosthetic survival rate. Even though such a result is slightly inferior to results in patients without hemophilia, our prosthetic survival rate is not significantly different from the rates reported in other, younger patient subsets. Late periprosthetic infections are a major concern, and taking precautions to avoid hematogenous spread of infections during factor concentrate infusions is strongly encouraged.

1. Arnold WD, Hilgartner MW. Hemophilic arthropathy. Current concepts of pathogenesis and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(3):287-305.

2. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Common orthopaedic problems in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 1999;5(suppl 1):53-60.

3. Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Glomstein A, et al. On-demand vs. prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia in Norway and Sweden: differences in treatment characteristics and outcome. Haemophilia. 2003;9(5):555-566.

4. Teigland JC, Tjønnfjord GE, Evensen SA, Charania B. Knee arthroplasty in hemophilia. 5-12 year follow-up of 15 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(2):153-156.

5. Silva M, Luck JV Jr. Long-term results of primary total knee replacement in patients with hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):85-91.

6. Wang K, Street A, Dowrick A, Liew S. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction following total joint replacement in haemophilia—23-year experience in knees, hips and elbows. Haemophilia. 2012;18(1):86-93.

7. Chevalier Y, Dargaud Y, Lienhart A, Chamouard V, Negrier C. Seventy-two total knee arthroplasties performed in patients with haemophilia using continuous infusion. Vox Sang. 2013;104(2):135-143.

8. Zingg PO, Fucentese SF, Lutz W, Brand B, Mamisch N, Koch PP. Haemophilic knee arthropathy: long-term outcome after total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(12):2465-2470.

9. Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Christiansen SE, Ingerslev J, Sneppen O. Total knee arthroplasty in classic hemophilia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(256):137-146.

10. Cohen I, Heim M, Martinowitz U, Chechick A. Orthopaedic outcome of total knee replacement in haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2000;6(2):104-109.

11. Fehily M, Fleming P, O’Shea E, Smith O, Smyth H. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with severe haemophilia. Int Orthop. 2002;26(2):89-91.

12. Legroux-Gérot I, Strouk G, Parquet A, Goodemand J, Gougeon F, Duquesnoy B. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(1):22-32.

13. Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):56-60.

14. Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):13-14.

15. Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(10):1434-1445.

16. Goddard NJ, Mann HA, Lee CA. Total knee replacement in patients with end-stage haemophilic arthropathy. 25-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(8):1085-1089.

17. Westberg M, Paus AC, Holme PA, Tjønnfjord GE. Haemophilic arthropathy: long-term outcomes in 107 primary total knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2014;21(1):147-150.

18. Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Failure of total knee arthroplasty with or without patella resurfacing. A study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register with 0-15 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):282-292.

19. Post M, Telfer MC. Surgery in hemophilic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(8):1136-1145.

20. Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients. Long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(4):575-582.

21. Lonner JH, Hershman S, Mont M, Lotke PA. Total knee arthroplasty in patients 40 years of age and younger with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(380):85-90.

22. Duffy GP, Crowder AR, Trousdale RR, Berry DJ. Cemented total knee arthroplasty using a modern prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):67-70.

23. Chiang CC, Chen PQ, Shen MC, Tsai W. Total knee arthroplasty for severe haemophilic arthropathy: long-term experience in Taiwan. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):828-834.

24. Solimeno LP, Mancuso ME, Pasta G, Santagostino E, Perfetto S, Mannucci PM. Factors influencing the long-term outcome of primary total knee replacement in haemophiliacs: a review of 116 procedures at a single institution. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(2):227-234.

25. Jämsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):87-92.

26. Ragni MV, Crossett LS, Herndon JH. Postoperative infection following orthopaedic surgery in human immunodeficiency virus–infected hemophiliacs with CD4 counts < or = 200/mm3. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):716-721.

27. Hicks JL, Ribbans WJ, Buzzard B, et al. Infected joint replacements in HIV-positive patients with haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1050-1054.

28. Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Heiple KG, Sobel M. Total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):98-107.

1. Arnold WD, Hilgartner MW. Hemophilic arthropathy. Current concepts of pathogenesis and management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59(3):287-305.

2. Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Common orthopaedic problems in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 1999;5(suppl 1):53-60.

3. Steen Carlsson K, Höjgård S, Glomstein A, et al. On-demand vs. prophylactic treatment for severe haemophilia in Norway and Sweden: differences in treatment characteristics and outcome. Haemophilia. 2003;9(5):555-566.

4. Teigland JC, Tjønnfjord GE, Evensen SA, Charania B. Knee arthroplasty in hemophilia. 5-12 year follow-up of 15 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(2):153-156.

5. Silva M, Luck JV Jr. Long-term results of primary total knee replacement in patients with hemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):85-91.

6. Wang K, Street A, Dowrick A, Liew S. Clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction following total joint replacement in haemophilia—23-year experience in knees, hips and elbows. Haemophilia. 2012;18(1):86-93.

7. Chevalier Y, Dargaud Y, Lienhart A, Chamouard V, Negrier C. Seventy-two total knee arthroplasties performed in patients with haemophilia using continuous infusion. Vox Sang. 2013;104(2):135-143.

8. Zingg PO, Fucentese SF, Lutz W, Brand B, Mamisch N, Koch PP. Haemophilic knee arthropathy: long-term outcome after total knee replacement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(12):2465-2470.

9. Kjaersgaard-Andersen P, Christiansen SE, Ingerslev J, Sneppen O. Total knee arthroplasty in classic hemophilia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(256):137-146.

10. Cohen I, Heim M, Martinowitz U, Chechick A. Orthopaedic outcome of total knee replacement in haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2000;6(2):104-109.

11. Fehily M, Fleming P, O’Shea E, Smith O, Smyth H. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with severe haemophilia. Int Orthop. 2002;26(2):89-91.

12. Legroux-Gérot I, Strouk G, Parquet A, Goodemand J, Gougeon F, Duquesnoy B. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70(1):22-32.

13. Sheth DS, Oldfield D, Ambrose C, Clyburn T. Total knee arthroplasty in hemophilic arthropathy. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(1):56-60.

14. Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):13-14.

15. Segawa H, Tsukayama DT, Kyle RF, Becker DA, Gustilo RB. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. A retrospective study of the treatment of eighty-one infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(10):1434-1445.

16. Goddard NJ, Mann HA, Lee CA. Total knee replacement in patients with end-stage haemophilic arthropathy. 25-year results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(8):1085-1089.

17. Westberg M, Paus AC, Holme PA, Tjønnfjord GE. Haemophilic arthropathy: long-term outcomes in 107 primary total knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2014;21(1):147-150.

18. Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Failure of total knee arthroplasty with or without patella resurfacing. A study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register with 0-15 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):282-292.

19. Post M, Telfer MC. Surgery in hemophilic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57(8):1136-1145.

20. Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients. Long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(4):575-582.

21. Lonner JH, Hershman S, Mont M, Lotke PA. Total knee arthroplasty in patients 40 years of age and younger with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(380):85-90.

22. Duffy GP, Crowder AR, Trousdale RR, Berry DJ. Cemented total knee arthroplasty using a modern prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6 suppl 2):67-70.

23. Chiang CC, Chen PQ, Shen MC, Tsai W. Total knee arthroplasty for severe haemophilic arthropathy: long-term experience in Taiwan. Haemophilia. 2008;14(4):828-834.

24. Solimeno LP, Mancuso ME, Pasta G, Santagostino E, Perfetto S, Mannucci PM. Factors influencing the long-term outcome of primary total knee replacement in haemophiliacs: a review of 116 procedures at a single institution. Br J Haematol. 2009;145(2):227-234.

25. Jämsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):87-92.

26. Ragni MV, Crossett LS, Herndon JH. Postoperative infection following orthopaedic surgery in human immunodeficiency virus–infected hemophiliacs with CD4 counts < or = 200/mm3. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(6):716-721.

27. Hicks JL, Ribbans WJ, Buzzard B, et al. Infected joint replacements in HIV-positive patients with haemophilia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(7):1050-1054.

28. Figgie MP, Goldberg VM, Figgie HE 3rd, Heiple KG, Sobel M. Total knee arthroplasty for the treatment of chronic hemophilic arthropathy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(248):98-107.

Intra-Articular Injections of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Knee Osteoarthritis

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), a common disabling disease with a high impact on quality of life, has a large societal cost. Yet no procedure halts progressive degeneration of the osteoarthritic knee joint.1,2

According to Barry,3 mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiate into many different connective tissue cells, including cartilage. MSCs can be isolated from bone marrow, skeletal muscle, fat, and synovium. MSCs are multipotent cells with the capacity for self-renewal. Therefore, adult MSCs may regenerate tissues damaged by disease. In OA, the proliferative capacity and ability to differentiate are reduced in MSCs. Intra-articular injections of MSCs (MSC therapy) could repair progressively degenerated knee cartilage.

This review article summarizes the knowledge on the role of intra-articular injections of MSCs in the treatment of KOA, based on studies published in PubMed and the Cochrane Library. The article also reviews the methodology and results of the animal and clinical studies published so far on the topic.

Materials and Methods

PubMed (Medline) and the Cochrane Library were searched for literature on the role of MSC therapy in treating KOA. The key words used were stem cells and knee osteoarthritis. The period searched was from when these search engines began until January 31, 2014. One hundred thirty-five articles (including negative studies) were found, but only the 25 deeply focused on the topic were reviewed. The Figure shows the flow diagram of this study.

Results

Several experimental models of KOA have shown that MSC therapy can delay progressive degeneration of the knee joint (Appendix 1).4-15 Using a rabbit massive meniscal defect model, Hatsushika and colleagues13 found that a single intra-articular injection of synovial MSCs into the knee adhered around the meniscal defect and promoted meniscal regeneration. Park and colleagues14 conducted an experimental study in dogs—the first demonstrating regional and systemic safety and systemic immunomodulatory effects of repeated local delivery of allogeneic MSCs in vivo. Regarding the observed systemic immunomodulatory effects, clinical and pathologic examinations revealed no severe consequences of repeated MSC transplantations. Results of mixed leukocyte reactions demonstrated suppression of T-cell proliferation after MSC transplantations.

Of the human studies published so far, only 3 were prospective randomized trials (level II evidence) included in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 2).16-18 Varma and colleagues16 found that intra-articular injections of MSCs considerably improved overall KOA outcome scores. Fifty patients with mild to moderate KOA were divided into 2 groups. Group A underwent arthroscopic débridement, and group B had buffy coat (MSC concentrate) injection and arthroscopic débridement. Patients were assessed on the basis of their visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and osteoarthritis outcome scores.

Wong and colleagues17 analyzed 56 knees in 56 patients (mean age, 51 years) with unicompartmental KOA and genu varum. Patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups, MSC and control. All patients underwent high tibial osteotomy (HTO) and microfracture. Patients in the MSC group received intra-articular injection of cultured MSCs with hyaluronic acid (HA) 3 weeks after surgery. Patients in the control group received only HA. The primary outcome measure was International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery. Secondary outcome measures were Tegner and Lysholm clinical scores and 1-year postoperative Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue (MOCART) scores. Both treatment arms achieved improvements in Tegner, Lysholm, and IKDC scores. After adjustment for age, baseline scores, and time of evaluation, the MSC group had significantly better scores. One year after surgery, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed significantly better MOCART scores for the MSC group. Intra-articular injection of MSCs appeared to be effective in improving short-term clinical and MOCART outcomes in patients who underwent HTO and microfracture for varus knees with cartilage defects.

Saw and colleagues18 compared histologic and MRI evaluation of articular cartilage regeneration in patients with chondral lesions treated by arthroscopic subchondral drilling followed by postoperative intra-articular injections of HA with and without peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs). Fifty patients (ages, 18-50 years) with International Cartilage Repair Society grades 3 and 4 lesions of the knee joint underwent arthroscopic subchondral drilling; 25 patients were randomized to the intervention group (HA + PBSC) and 25 to the control group (HA). Both groups received 5 weekly injections starting 1 week after surgery. Three additional injections of either HA + PBSC or HA only were given at weekly intervals 6 months after surgery. After arthroscopic subchondral drilling into grades 3 and 4 chondral lesions, postoperative intra-articular injections of autologous PBSC combined with HA resulted in improved quality of articular cartilage repair over the same treatment without PBSC.

The other human studies analyzed had a low level of evidence (grade IV, case series) but found that intra-articular injections of MSCs reduced pain and improved function in patients with KOA over the short term, 1 year (Appendix 3).19-25

Discussion

This review aimed to define the role of MSC therapy in the treatment of KOA. MSC therapy has yielded encouraging outcomes in experimental models of KOA.4-15 These experimental studies have suggested that MSCs can halt cartilage degeneration in KOA. So far, however, only 3 human studies with grade II evidence (randomized prospective trials) have been reported on the role of MSCs in KOA, but results of these studies have suggested that MSCs can reduce pain and improve function.16-18

Previous reviews of the literature1,2 have analyzed the role of MSC therapy in KOA. Barry and Murphy1 reported that several early-stage clinical trials, initiated or under way in 2013, were testing MSC delivery as an intra-articular injection into the knee, but optimal dose and vehicle were yet to be established. Filardo and colleagues2 reported that, despite growing interest in this biological approach to cartilage regeneration, knowledge on the topic is still preliminary, as shown by the prevalence of preclinical studies and the presence of low-quality clinical studies.

Study design weakness prevents effective comparison of the efficacy of MSC therapy with that of other treatments for relief of pain and other outcomes in KOA. The consistency of evidence of the clinical studies is low because of many uncontrolled variables.1-3

Conclusion

The results of MSC therapy in KOA are encouraging. However, optimal dose and vehicle are yet to be established.1 Knowledge on this topic is still preliminary. Many aspects have to be optimized, and further randomized controlled trials are needed to support the potential of this biological treatment for cartilage repair and to evaluate advantages and disadvantages with respect to the available treatments. The relative short duration of these studies is also a limitation for the technique at present.

1. Barry F, Murphy M. Mesenchymal stem cells in joint disease and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(10):584-594.

2. Filardo G, Madry H, Jelic M, Roffi A, Cucchiarini M, Kon E. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of cartilage lesions: from preclinical findings to clinical application in orthopaedics. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(8):1717-1729.

3. Barry FP. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in joint disease. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;249:86-96.

4. Murphy JM, Fink DJ, Hunziker EB, Barry FP. Stem cell therapy in a caprine model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(12):3464-3474.

5. Al Faqeh H, Norhamdan MY, Chua KH, Chen HC, Aminuddin BS, Ruszymah BH. Cell based therapy for osteoarthritis in a sheep model: gross and histological assessment. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63(suppl A):37-38.

6. Grigolo B, Lisignoli G, Desando G, et al. Osteoarthritis treated with mesenchymal stem cells on hyaluronan-based scaffold in rabbit. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;15(4):647-658.

7. Toghraie FS, Chenari N, Gholipour MA, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with infrapatellar fat pad derived mesenchymal stem cells in rabbit. Knee. 2011;18(2):71-75.

8. Sato M, Uchida K, Nakajima H, et al. Direct transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells into the knee joints of Hartley strain guinea pigs with spontaneous osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):R31.

9. Suhaeb AM, Naveen S, Mansor A, Kamarul T. Hyaluronic acid with or without bone marrow derived-mesenchymal stem cells improves osteoarthritic knee changes in rat model: a preliminary report. Indian J Exp Biol. 2012;50(6):383-390.

10. Al Faqeh H, Nor Hamdan BM, Chen HC, Aminuddin BS, Ruszymah BH. The potential of intra-articular injection of chondrogenic-induced bone marrow stem cells to retard the progression of osteoarthritis in a sheep model. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(6):458-464.

11. Toghraie F, Razmkhah M, Gholipour MA, et al. Scaffold-free adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) improve experimentally induced osteoarthritis in rabbits. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(8):495-499.

12. ter Huurne M, Schelbergen R, Blattes R, et al. Antiinflammatory and chondroprotective effects of intraarticular injection of adipose-derived stem cells in experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(11):3604-3613.

13. Hatsushika D, Muneta T, Horie M, Koga H, Tsuji K, Sekiya I. Intraarticular injection of synovial stem cells promotes meniscal regeneration in a rabbit massive meniscal defect model. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(9):1354-1359.

14. Park SA, Reilly CM, Wood JA, et al. Safety and immunomodulatory effects of allogeneic canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells transplanted into the region of the lacrimal gland, the gland of the third eyelid and the knee joint. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(12):1498-1510.

15. Nam H, Karunanithi P, Loo WC, et al. The effects of staged intra-articular injection of cultured autologous mesenchymal stromal cells on the repair of damaged cartilage: a pilot study in caprine model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R129.

16. Varma HS, Dadarya B, Vidyarthi A. The new avenues in the management of osteo-arthritis of knee—stem cells. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108(9):583-585.

17. Wong KL, Lee KB, Tai BC, Law P, Lee EH, Hui JH. Injectable cultured bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):2020-2028.

18. Saw KY, Anz A, Siew-Yoke Jee C, et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood stem cells versus hyaluronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):684-694.

19. Davatchi F, Abdollahi BS, Mohyeddin M, Shahram F, Nikbin B. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Preliminary report of four patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14(2):211-215.

20. Koh YG, Choi YJ. Infrapatellar fat pad–derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Knee. 2012;19(4):902-907.

21. Orozco L, Munar A, Soler R, et al. Treatment of knee osteoarthritis with autologous mesenchymal stem cells: a pilot study. Transplantation. 2013;95(12):1535-1541.

22. Koh YG, Jo SB, Kwon OR, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell injections improve symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):748-755.

23. Koh YG, Choi YJ, Kwon SK, Kim YS, Yeo JE. Clinical results and second-look arthroscopic findings after treatment with adipose-derived stem cells for knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013 Dec 11. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Jo CH, Lee YG, Shin WH, et al. Intra-articular injection of mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a proof-of-concept clinical trial. Stem Cells. 2014;32(5):1254-1266.

25. Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Sankineani SR. One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(3):648-657.

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), a common disabling disease with a high impact on quality of life, has a large societal cost. Yet no procedure halts progressive degeneration of the osteoarthritic knee joint.1,2

According to Barry,3 mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiate into many different connective tissue cells, including cartilage. MSCs can be isolated from bone marrow, skeletal muscle, fat, and synovium. MSCs are multipotent cells with the capacity for self-renewal. Therefore, adult MSCs may regenerate tissues damaged by disease. In OA, the proliferative capacity and ability to differentiate are reduced in MSCs. Intra-articular injections of MSCs (MSC therapy) could repair progressively degenerated knee cartilage.

This review article summarizes the knowledge on the role of intra-articular injections of MSCs in the treatment of KOA, based on studies published in PubMed and the Cochrane Library. The article also reviews the methodology and results of the animal and clinical studies published so far on the topic.

Materials and Methods

PubMed (Medline) and the Cochrane Library were searched for literature on the role of MSC therapy in treating KOA. The key words used were stem cells and knee osteoarthritis. The period searched was from when these search engines began until January 31, 2014. One hundred thirty-five articles (including negative studies) were found, but only the 25 deeply focused on the topic were reviewed. The Figure shows the flow diagram of this study.

Results

Several experimental models of KOA have shown that MSC therapy can delay progressive degeneration of the knee joint (Appendix 1).4-15 Using a rabbit massive meniscal defect model, Hatsushika and colleagues13 found that a single intra-articular injection of synovial MSCs into the knee adhered around the meniscal defect and promoted meniscal regeneration. Park and colleagues14 conducted an experimental study in dogs—the first demonstrating regional and systemic safety and systemic immunomodulatory effects of repeated local delivery of allogeneic MSCs in vivo. Regarding the observed systemic immunomodulatory effects, clinical and pathologic examinations revealed no severe consequences of repeated MSC transplantations. Results of mixed leukocyte reactions demonstrated suppression of T-cell proliferation after MSC transplantations.

Of the human studies published so far, only 3 were prospective randomized trials (level II evidence) included in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 2).16-18 Varma and colleagues16 found that intra-articular injections of MSCs considerably improved overall KOA outcome scores. Fifty patients with mild to moderate KOA were divided into 2 groups. Group A underwent arthroscopic débridement, and group B had buffy coat (MSC concentrate) injection and arthroscopic débridement. Patients were assessed on the basis of their visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and osteoarthritis outcome scores.

Wong and colleagues17 analyzed 56 knees in 56 patients (mean age, 51 years) with unicompartmental KOA and genu varum. Patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups, MSC and control. All patients underwent high tibial osteotomy (HTO) and microfracture. Patients in the MSC group received intra-articular injection of cultured MSCs with hyaluronic acid (HA) 3 weeks after surgery. Patients in the control group received only HA. The primary outcome measure was International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery. Secondary outcome measures were Tegner and Lysholm clinical scores and 1-year postoperative Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue (MOCART) scores. Both treatment arms achieved improvements in Tegner, Lysholm, and IKDC scores. After adjustment for age, baseline scores, and time of evaluation, the MSC group had significantly better scores. One year after surgery, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed significantly better MOCART scores for the MSC group. Intra-articular injection of MSCs appeared to be effective in improving short-term clinical and MOCART outcomes in patients who underwent HTO and microfracture for varus knees with cartilage defects.

Saw and colleagues18 compared histologic and MRI evaluation of articular cartilage regeneration in patients with chondral lesions treated by arthroscopic subchondral drilling followed by postoperative intra-articular injections of HA with and without peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs). Fifty patients (ages, 18-50 years) with International Cartilage Repair Society grades 3 and 4 lesions of the knee joint underwent arthroscopic subchondral drilling; 25 patients were randomized to the intervention group (HA + PBSC) and 25 to the control group (HA). Both groups received 5 weekly injections starting 1 week after surgery. Three additional injections of either HA + PBSC or HA only were given at weekly intervals 6 months after surgery. After arthroscopic subchondral drilling into grades 3 and 4 chondral lesions, postoperative intra-articular injections of autologous PBSC combined with HA resulted in improved quality of articular cartilage repair over the same treatment without PBSC.

The other human studies analyzed had a low level of evidence (grade IV, case series) but found that intra-articular injections of MSCs reduced pain and improved function in patients with KOA over the short term, 1 year (Appendix 3).19-25

Discussion

This review aimed to define the role of MSC therapy in the treatment of KOA. MSC therapy has yielded encouraging outcomes in experimental models of KOA.4-15 These experimental studies have suggested that MSCs can halt cartilage degeneration in KOA. So far, however, only 3 human studies with grade II evidence (randomized prospective trials) have been reported on the role of MSCs in KOA, but results of these studies have suggested that MSCs can reduce pain and improve function.16-18

Previous reviews of the literature1,2 have analyzed the role of MSC therapy in KOA. Barry and Murphy1 reported that several early-stage clinical trials, initiated or under way in 2013, were testing MSC delivery as an intra-articular injection into the knee, but optimal dose and vehicle were yet to be established. Filardo and colleagues2 reported that, despite growing interest in this biological approach to cartilage regeneration, knowledge on the topic is still preliminary, as shown by the prevalence of preclinical studies and the presence of low-quality clinical studies.

Study design weakness prevents effective comparison of the efficacy of MSC therapy with that of other treatments for relief of pain and other outcomes in KOA. The consistency of evidence of the clinical studies is low because of many uncontrolled variables.1-3

Conclusion

The results of MSC therapy in KOA are encouraging. However, optimal dose and vehicle are yet to be established.1 Knowledge on this topic is still preliminary. Many aspects have to be optimized, and further randomized controlled trials are needed to support the potential of this biological treatment for cartilage repair and to evaluate advantages and disadvantages with respect to the available treatments. The relative short duration of these studies is also a limitation for the technique at present.

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA), a common disabling disease with a high impact on quality of life, has a large societal cost. Yet no procedure halts progressive degeneration of the osteoarthritic knee joint.1,2

According to Barry,3 mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiate into many different connective tissue cells, including cartilage. MSCs can be isolated from bone marrow, skeletal muscle, fat, and synovium. MSCs are multipotent cells with the capacity for self-renewal. Therefore, adult MSCs may regenerate tissues damaged by disease. In OA, the proliferative capacity and ability to differentiate are reduced in MSCs. Intra-articular injections of MSCs (MSC therapy) could repair progressively degenerated knee cartilage.

This review article summarizes the knowledge on the role of intra-articular injections of MSCs in the treatment of KOA, based on studies published in PubMed and the Cochrane Library. The article also reviews the methodology and results of the animal and clinical studies published so far on the topic.

Materials and Methods

PubMed (Medline) and the Cochrane Library were searched for literature on the role of MSC therapy in treating KOA. The key words used were stem cells and knee osteoarthritis. The period searched was from when these search engines began until January 31, 2014. One hundred thirty-five articles (including negative studies) were found, but only the 25 deeply focused on the topic were reviewed. The Figure shows the flow diagram of this study.

Results

Several experimental models of KOA have shown that MSC therapy can delay progressive degeneration of the knee joint (Appendix 1).4-15 Using a rabbit massive meniscal defect model, Hatsushika and colleagues13 found that a single intra-articular injection of synovial MSCs into the knee adhered around the meniscal defect and promoted meniscal regeneration. Park and colleagues14 conducted an experimental study in dogs—the first demonstrating regional and systemic safety and systemic immunomodulatory effects of repeated local delivery of allogeneic MSCs in vivo. Regarding the observed systemic immunomodulatory effects, clinical and pathologic examinations revealed no severe consequences of repeated MSC transplantations. Results of mixed leukocyte reactions demonstrated suppression of T-cell proliferation after MSC transplantations.

Of the human studies published so far, only 3 were prospective randomized trials (level II evidence) included in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 2).16-18 Varma and colleagues16 found that intra-articular injections of MSCs considerably improved overall KOA outcome scores. Fifty patients with mild to moderate KOA were divided into 2 groups. Group A underwent arthroscopic débridement, and group B had buffy coat (MSC concentrate) injection and arthroscopic débridement. Patients were assessed on the basis of their visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores and osteoarthritis outcome scores.

Wong and colleagues17 analyzed 56 knees in 56 patients (mean age, 51 years) with unicompartmental KOA and genu varum. Patients were randomly assigned to 2 groups, MSC and control. All patients underwent high tibial osteotomy (HTO) and microfracture. Patients in the MSC group received intra-articular injection of cultured MSCs with hyaluronic acid (HA) 3 weeks after surgery. Patients in the control group received only HA. The primary outcome measure was International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery. Secondary outcome measures were Tegner and Lysholm clinical scores and 1-year postoperative Magnetic Resonance Observation of Cartilage Repair Tissue (MOCART) scores. Both treatment arms achieved improvements in Tegner, Lysholm, and IKDC scores. After adjustment for age, baseline scores, and time of evaluation, the MSC group had significantly better scores. One year after surgery, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed significantly better MOCART scores for the MSC group. Intra-articular injection of MSCs appeared to be effective in improving short-term clinical and MOCART outcomes in patients who underwent HTO and microfracture for varus knees with cartilage defects.

Saw and colleagues18 compared histologic and MRI evaluation of articular cartilage regeneration in patients with chondral lesions treated by arthroscopic subchondral drilling followed by postoperative intra-articular injections of HA with and without peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs). Fifty patients (ages, 18-50 years) with International Cartilage Repair Society grades 3 and 4 lesions of the knee joint underwent arthroscopic subchondral drilling; 25 patients were randomized to the intervention group (HA + PBSC) and 25 to the control group (HA). Both groups received 5 weekly injections starting 1 week after surgery. Three additional injections of either HA + PBSC or HA only were given at weekly intervals 6 months after surgery. After arthroscopic subchondral drilling into grades 3 and 4 chondral lesions, postoperative intra-articular injections of autologous PBSC combined with HA resulted in improved quality of articular cartilage repair over the same treatment without PBSC.

The other human studies analyzed had a low level of evidence (grade IV, case series) but found that intra-articular injections of MSCs reduced pain and improved function in patients with KOA over the short term, 1 year (Appendix 3).19-25

Discussion

This review aimed to define the role of MSC therapy in the treatment of KOA. MSC therapy has yielded encouraging outcomes in experimental models of KOA.4-15 These experimental studies have suggested that MSCs can halt cartilage degeneration in KOA. So far, however, only 3 human studies with grade II evidence (randomized prospective trials) have been reported on the role of MSCs in KOA, but results of these studies have suggested that MSCs can reduce pain and improve function.16-18

Previous reviews of the literature1,2 have analyzed the role of MSC therapy in KOA. Barry and Murphy1 reported that several early-stage clinical trials, initiated or under way in 2013, were testing MSC delivery as an intra-articular injection into the knee, but optimal dose and vehicle were yet to be established. Filardo and colleagues2 reported that, despite growing interest in this biological approach to cartilage regeneration, knowledge on the topic is still preliminary, as shown by the prevalence of preclinical studies and the presence of low-quality clinical studies.

Study design weakness prevents effective comparison of the efficacy of MSC therapy with that of other treatments for relief of pain and other outcomes in KOA. The consistency of evidence of the clinical studies is low because of many uncontrolled variables.1-3

Conclusion

The results of MSC therapy in KOA are encouraging. However, optimal dose and vehicle are yet to be established.1 Knowledge on this topic is still preliminary. Many aspects have to be optimized, and further randomized controlled trials are needed to support the potential of this biological treatment for cartilage repair and to evaluate advantages and disadvantages with respect to the available treatments. The relative short duration of these studies is also a limitation for the technique at present.

1. Barry F, Murphy M. Mesenchymal stem cells in joint disease and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(10):584-594.

2. Filardo G, Madry H, Jelic M, Roffi A, Cucchiarini M, Kon E. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of cartilage lesions: from preclinical findings to clinical application in orthopaedics. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(8):1717-1729.

3. Barry FP. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in joint disease. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;249:86-96.

4. Murphy JM, Fink DJ, Hunziker EB, Barry FP. Stem cell therapy in a caprine model of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(12):3464-3474.

5. Al Faqeh H, Norhamdan MY, Chua KH, Chen HC, Aminuddin BS, Ruszymah BH. Cell based therapy for osteoarthritis in a sheep model: gross and histological assessment. Med J Malaysia. 2008;63(suppl A):37-38.

6. Grigolo B, Lisignoli G, Desando G, et al. Osteoarthritis treated with mesenchymal stem cells on hyaluronan-based scaffold in rabbit. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;15(4):647-658.

7. Toghraie FS, Chenari N, Gholipour MA, et al. Treatment of osteoarthritis with infrapatellar fat pad derived mesenchymal stem cells in rabbit. Knee. 2011;18(2):71-75.

8. Sato M, Uchida K, Nakajima H, et al. Direct transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells into the knee joints of Hartley strain guinea pigs with spontaneous osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(1):R31.

9. Suhaeb AM, Naveen S, Mansor A, Kamarul T. Hyaluronic acid with or without bone marrow derived-mesenchymal stem cells improves osteoarthritic knee changes in rat model: a preliminary report. Indian J Exp Biol. 2012;50(6):383-390.

10. Al Faqeh H, Nor Hamdan BM, Chen HC, Aminuddin BS, Ruszymah BH. The potential of intra-articular injection of chondrogenic-induced bone marrow stem cells to retard the progression of osteoarthritis in a sheep model. Exp Gerontol. 2012;47(6):458-464.

11. Toghraie F, Razmkhah M, Gholipour MA, et al. Scaffold-free adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) improve experimentally induced osteoarthritis in rabbits. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(8):495-499.

12. ter Huurne M, Schelbergen R, Blattes R, et al. Antiinflammatory and chondroprotective effects of intraarticular injection of adipose-derived stem cells in experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(11):3604-3613.

13. Hatsushika D, Muneta T, Horie M, Koga H, Tsuji K, Sekiya I. Intraarticular injection of synovial stem cells promotes meniscal regeneration in a rabbit massive meniscal defect model. J Orthop Res. 2013;31(9):1354-1359.

14. Park SA, Reilly CM, Wood JA, et al. Safety and immunomodulatory effects of allogeneic canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells transplanted into the region of the lacrimal gland, the gland of the third eyelid and the knee joint. Cytotherapy. 2013;15(12):1498-1510.

15. Nam H, Karunanithi P, Loo WC, et al. The effects of staged intra-articular injection of cultured autologous mesenchymal stromal cells on the repair of damaged cartilage: a pilot study in caprine model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R129.

16. Varma HS, Dadarya B, Vidyarthi A. The new avenues in the management of osteo-arthritis of knee—stem cells. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108(9):583-585.

17. Wong KL, Lee KB, Tai BC, Law P, Lee EH, Hui JH. Injectable cultured bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):2020-2028.

18. Saw KY, Anz A, Siew-Yoke Jee C, et al. Articular cartilage regeneration with autologous peripheral blood stem cells versus hyaluronic acid: a randomized controlled trial. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):684-694.

19. Davatchi F, Abdollahi BS, Mohyeddin M, Shahram F, Nikbin B. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Preliminary report of four patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14(2):211-215.