User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? Mycosis Fungoides

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

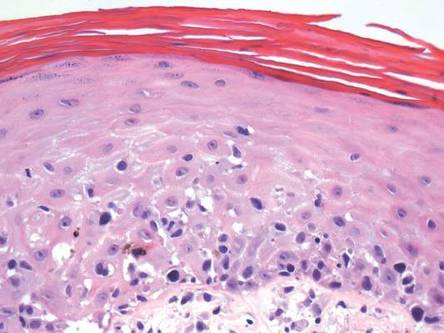

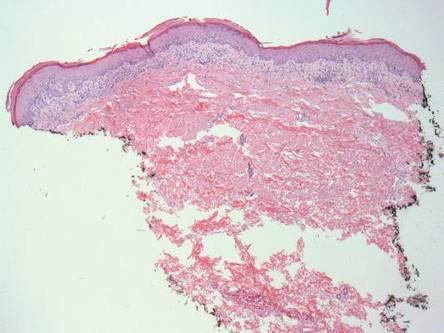

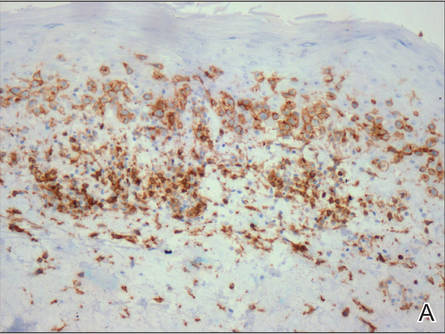

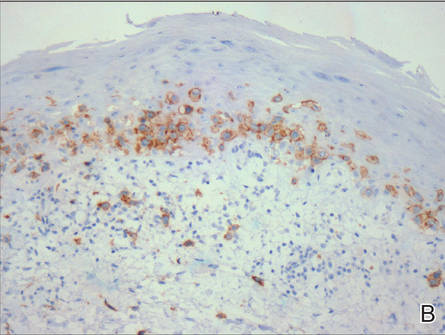

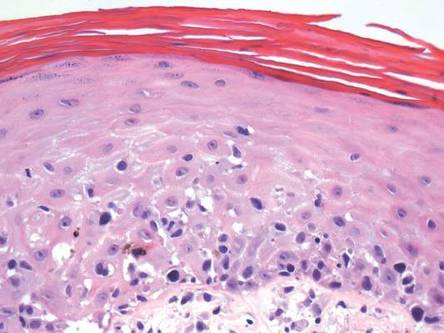

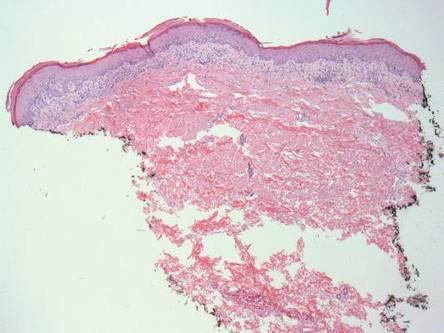

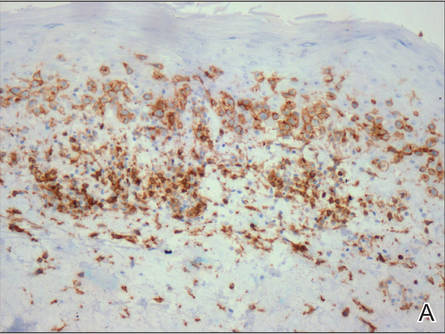

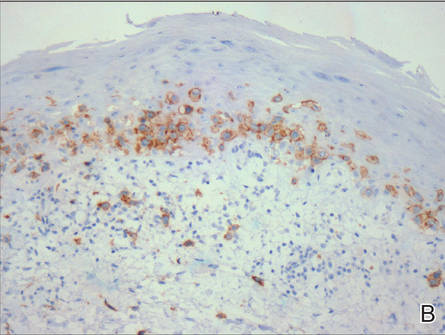

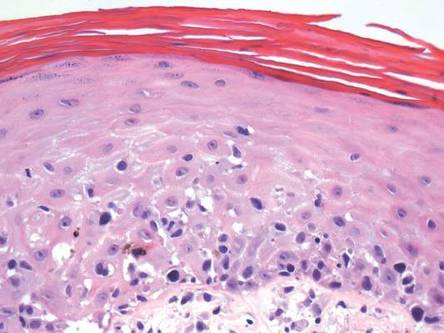

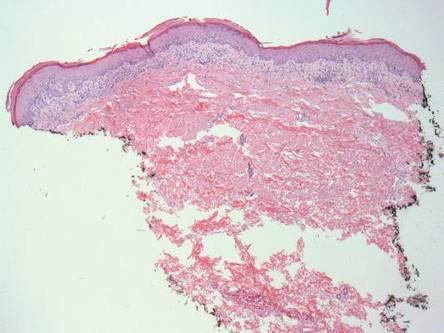

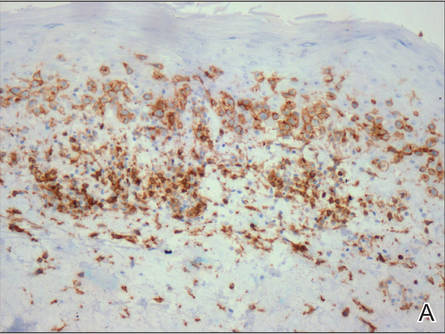

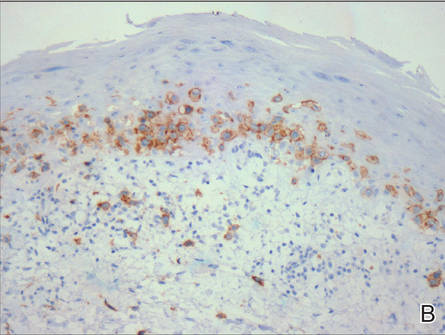

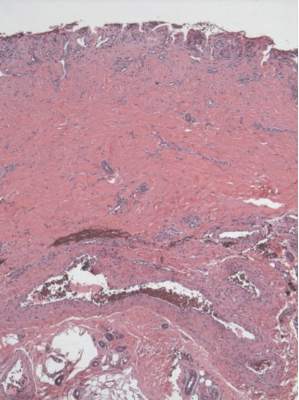

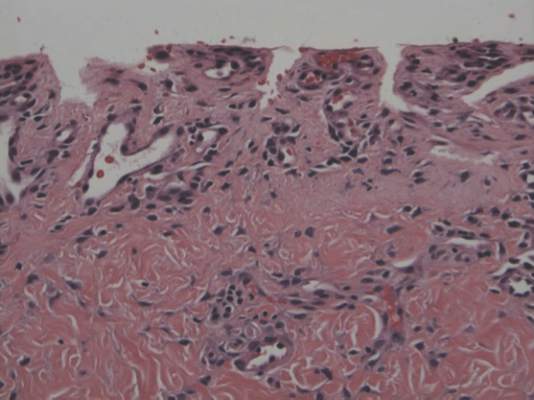

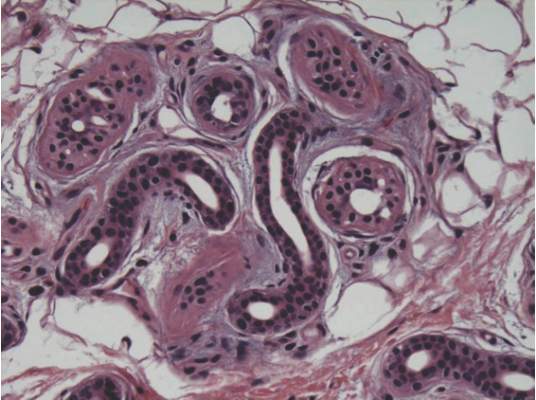

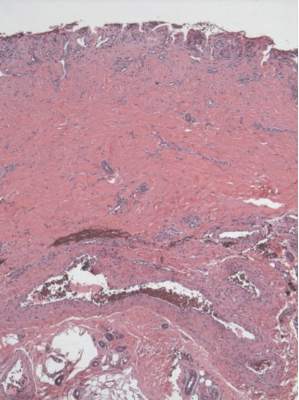

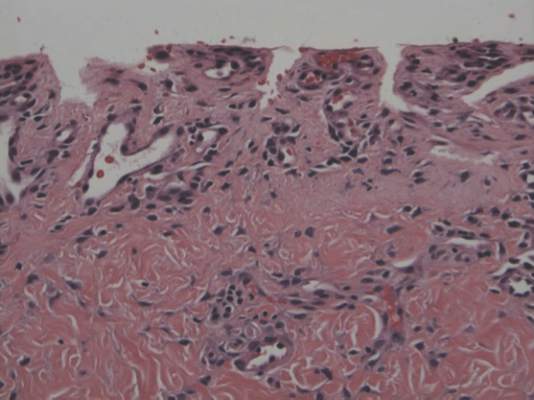

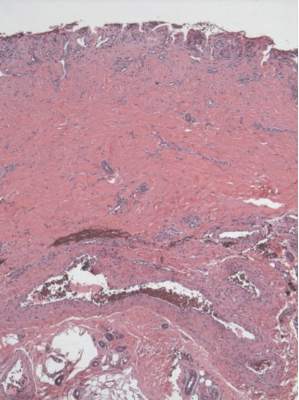

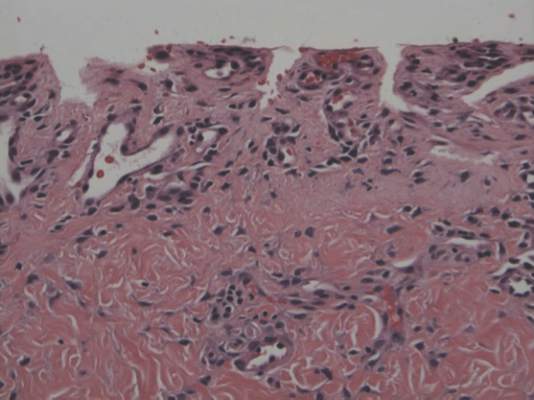

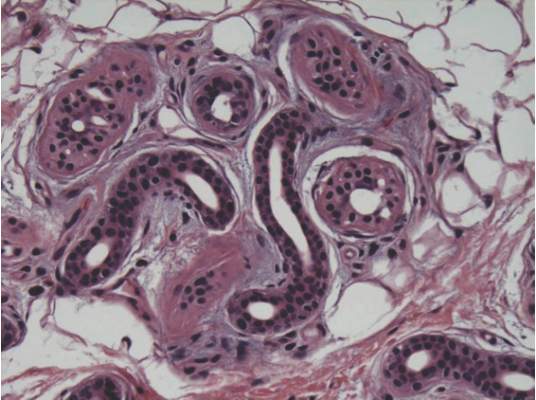

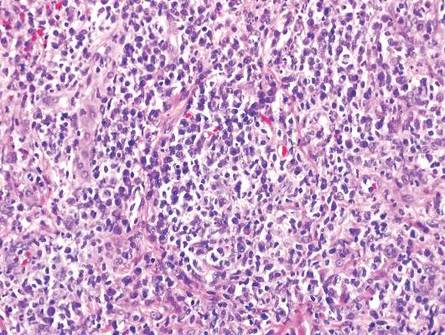

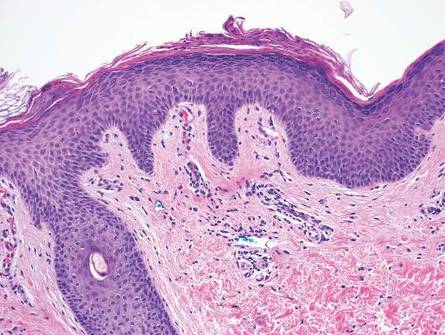

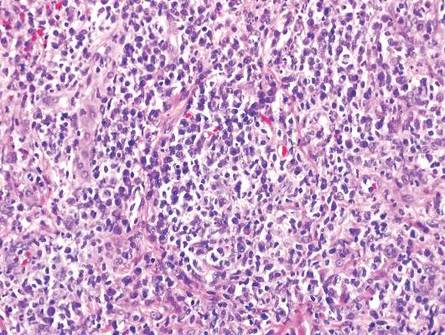

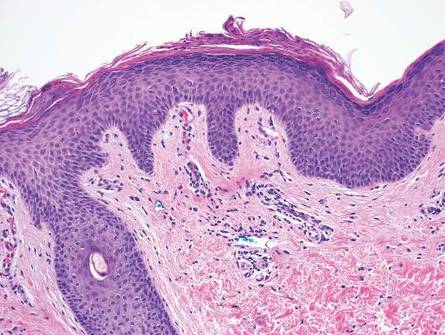

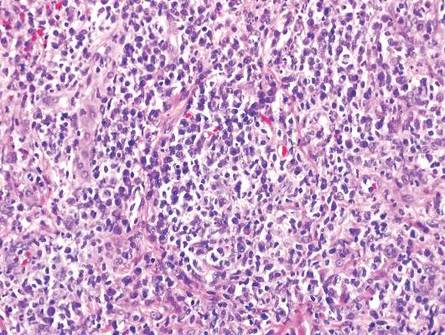

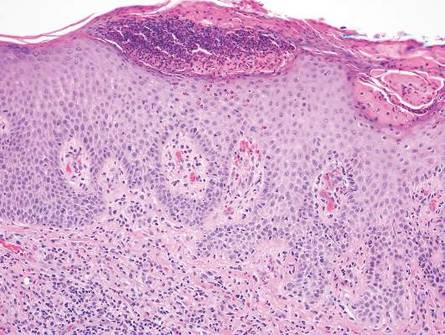

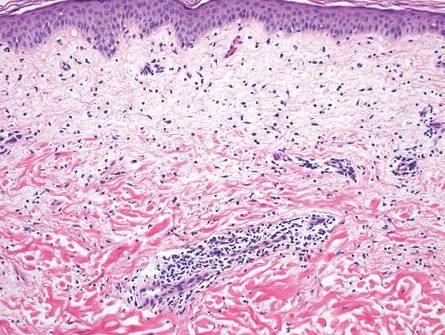

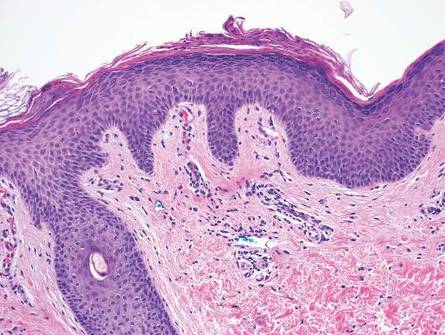

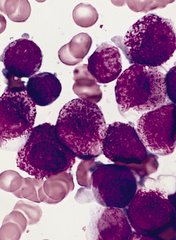

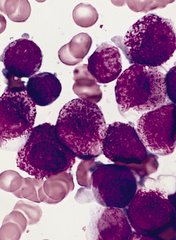

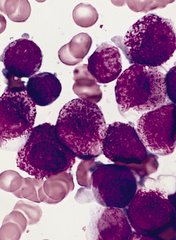

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

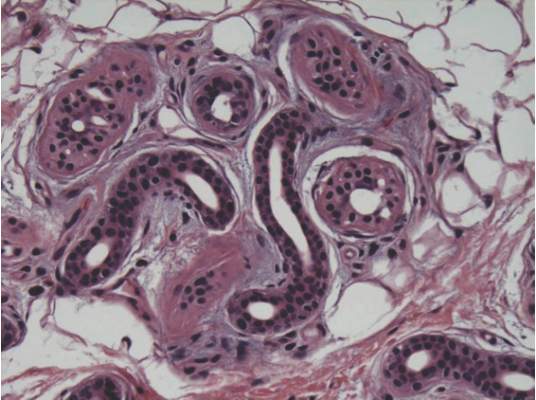

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

The Diagnosis: Mycosis Fungoides

Physical examination revealed erythematous polycyclic and arcuate plaques with fine overlying scale on the right arm and shoulder (Figure 1). Mild wrinkling and telangiectasias were noted on the skin surrounding the lesions. Laboratory tests showed normal values for antinuclear antibodies, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A, and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B.

A skin biopsy of a plaque on the right upper arm showed enlarged pleomorphic lymphocytes arranged along the basal layer and in focal collections within the epidermis (Figure 2). Within the dermis were wiry bundles of collagen, a sparse superficial and patchy infiltrate of lymphocytes, and scattered large mononuclear cells (Figure 3). Immunoperoxidase staining revealed large intraepidermal lymphocytes positive for CD4 (Figure 4A) and CD5. Notably, these lymphocytes also stained positive for CD30 (Figure 4B). Staining for CD8, CD1a, CD56, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase was negative, with aberrant loss of CD3. The morphology and pattern of immunoreactivity supported the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides (MF).

Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.1 Its progression is classified in 3 stages: (1) early (patch) stage, (2) plaque stage, and (3) tumor stage. Conclusive diagnosis of early stage MF often is difficult due to its clinical features that are similar to more common benign dermatoses (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus), leading to shortcomings in determining prognosis and selecting an appropriate treatment regimen. With this diagnositic difficulty in mind, guidelines have been created to aid in the diagnosis of early stage MF.2

Clinical features consistent with early stage MF include multiple erythematous, well-demarcated lesions with varying shapes that typically are greater than 5 cm in diameter.2 Lesions usually are flat or thinly elevated and may exhibit slight scaling. As was noted in our patient, poikiloderma of the surrounding skin is fairly specific for early stage MF, as it is not a feature associated with common clinical mimics of MF (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, lichen planus). The distribution of skin lesions in non–sun-exposed areas is common. The eruption is persistent, though it may wax and wane in severity.2

|

| |

|

|

Histopathologic examination is necessary to confirm a diagnosis of MF. Typically, early stage MF is marked by enlarged T lymphocytes within the epidermis as well as the papillary and superficial reticular dermis. Cerebriform nuclei are a key finding in the diagnosis of MF. Lymphocytes frequently are arranged linearly along the basal layer of the epidermis. Within the epidermis, clusters of atypical lymphocytes (Pautrier microabscesses) without spongiosis are uncommon but are a characteristic finding of MF if present.1 Papillary dermal fibrosis also may be evident.2

|

| |

Figure 4. Large intraepidermal lymphocytes were highlighted on CD4 (A) and CD30 immunostaining (B)(original magnification ×200 and ×200). | ||

Immunostaining typically reveals positivity for CD3 and CD4, as well as for lymphocyte antigens CD2 and CD5.1 CD30 positivity in early stage MF rarely has been reported in the literature.3,4 Such cases appear histologically similarly to CD30‒negative cases in other respects. One study showed that the presence of CD30-positive lymphocytes does not alter the clinical course of MF.3 Another study found that, while epidermal CD30-postive lymphocytes had no prognostic relevance, an increased percentage of dermal CD30-positive cells was linked to a higher stage at diagnosis and worse overall prognosis.5 Pathogenesis underlying CD30 positivity in early MF is unknown. It is important to note that CD30-positive cells commonly are seen in lymphomatoid papulosis and anaplastic large cell lymphoma, as well as a variety of nonneoplastic conditions.3,6,7

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

- Smoller BR. Mycosis fungoides: what do/do not we know? J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 2):35-39.

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063.

- Wu H, Telang GH, Lessin SR, et al. Mycosis fungoides with CD30-positive cells in the epidermis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:212-216.

- Ohtani T, Kikuchi K, Koizumi H, et al. A case of CD30+ large-cell transformation in a patient with unilesional patch-stage mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:623-626.

- Edinger JT, Clark BZ, Pucevich BE, et al. CD30 expression and proliferative fraction in nontransformed mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1860-1868.

- Resnik KS, Kutzner H. Of lymphocytes and cutaneous epithelium: keratoacanthomatous hyperplasia in CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders and CD30+ cells associated with keratoacanthoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:314-315.

- Kempf W. CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders: histopathology, differential diagnosis, new variants, and simulators. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33(suppl 1):58-70.

An otherwise healthy 62-year-old man presented for evaluation of multiple scaly erythematous plaques on the right upper arm and shoulder of 10 years’ duration. The patient reported a burning sensation but no exacerbation of the lesions upon sun exposure. He previously had been treated for a presumed clinical diagnosis of erythema annulare centrifugum but experienced only modest improvement with topical corticosteroids and tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Previous trials of systemic antifungals also yielded minimal benefit.

Capital misadventures

A few years ago I wrote a column about what promised to be an exciting development in blood testing technology. Using the money her parents had set aside for her education, a young woman dropped out of Stanford University at age 19 and started a company that she claimed would be able to offer hundreds of lab tests on just a few drops of blood. Results would be available in just minutes instead of hours or days. At the time I wrote the column, the company had just landed a contract with a large drug store chain with an arrangement that would eventually allow nearly every resident of the United States to be within a few miles of a site that would offer rapid response blood tests with nothing more than a finger prick.

It seemed a little hard to believe, but the prospect of pediatricians being able to make a diagnosis without running the risk of exsanguinating our smallest patients sounded appealing. On the other hand, I worried that a quick and easy technology might encourage some physicians to use a shotgun approach to diagnosing illness rather than a more rational and cost-effective process based on the traditional skills of history taking and physical examination. Some patients who foolishly wanted to know “everything” about themselves might be tempted to ask their physicians to order the whole smorgasbord of tests. “Hey, it’s only a few drops of blood.”

Turns out there were enough people with more money than reservations and the company quickly attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital. The company, now calling itself Theranos, has been valued at nine billion dollars. But, recently this startup star has encountered some serious bumps in the road to a full-scale launch (“Hot Startup Theranos Has Struggled With Its Blood-Test Technology” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015). The Wall Street Journal reported that despite promises, only a few of the 240 tests offered by the company are currently performed using their proprietary microtechnique. In the days following the Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration warned Theranos that their “nanotainer” is considered a new medical device that must first clear the agency’s time consuming and costly vetting process (“Hot Startup Theranos Dials Back Lab Tests at FDA’s Behest” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015).

The venture capitalists who had climbed on the Theranos bandwagon tempted by the just-a-few-drops promise may end up seeing their bank accounts hemorrhage. But I don’t think we should be too critical of their investment decision. It was and may still be good idea that has simply run afoul of the details. However, I recently learned about another new business that I don’t consider to have even started with a good idea, but still has managed to attract enough capital to get itself off the ground (“Should Breast Milk Be Nutritionally Analyzed?” by Laura Johannes, The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 28, 2015).

I’m sure you have seen some new mothers who were concerned that their breast milk was not enough for their babies. But how many of them would pay $150 for a start-up kit and then more than $300 to find out the nutritional content of their breast milk? What if it meant pumping and freezing three samples 2 or 3 days apart and then shipping them in a cooler to a lab? What if you told them that neither you nor anyone else could reliably interpret the results because there aren’t any published guidelines for the optimal composition of human breast milk? Even if your practice is packed to the rafters with anxiety-driven, irrational parents, I don’t think you would find many takers. But that doesn’t seem to have bothered the folks who have invested in Happy Vitals, a company in Washington that is offering a service similar to the one I have just described.

You and I might not have invested in a company whose business plan was to offer such a service. But I fear there may be enough health care “providers” practicing without the benefit of an evidence-based education that what I consider a capital misadventure may actually be able to pay back its investors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

A few years ago I wrote a column about what promised to be an exciting development in blood testing technology. Using the money her parents had set aside for her education, a young woman dropped out of Stanford University at age 19 and started a company that she claimed would be able to offer hundreds of lab tests on just a few drops of blood. Results would be available in just minutes instead of hours or days. At the time I wrote the column, the company had just landed a contract with a large drug store chain with an arrangement that would eventually allow nearly every resident of the United States to be within a few miles of a site that would offer rapid response blood tests with nothing more than a finger prick.

It seemed a little hard to believe, but the prospect of pediatricians being able to make a diagnosis without running the risk of exsanguinating our smallest patients sounded appealing. On the other hand, I worried that a quick and easy technology might encourage some physicians to use a shotgun approach to diagnosing illness rather than a more rational and cost-effective process based on the traditional skills of history taking and physical examination. Some patients who foolishly wanted to know “everything” about themselves might be tempted to ask their physicians to order the whole smorgasbord of tests. “Hey, it’s only a few drops of blood.”

Turns out there were enough people with more money than reservations and the company quickly attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital. The company, now calling itself Theranos, has been valued at nine billion dollars. But, recently this startup star has encountered some serious bumps in the road to a full-scale launch (“Hot Startup Theranos Has Struggled With Its Blood-Test Technology” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015). The Wall Street Journal reported that despite promises, only a few of the 240 tests offered by the company are currently performed using their proprietary microtechnique. In the days following the Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration warned Theranos that their “nanotainer” is considered a new medical device that must first clear the agency’s time consuming and costly vetting process (“Hot Startup Theranos Dials Back Lab Tests at FDA’s Behest” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015).

The venture capitalists who had climbed on the Theranos bandwagon tempted by the just-a-few-drops promise may end up seeing their bank accounts hemorrhage. But I don’t think we should be too critical of their investment decision. It was and may still be good idea that has simply run afoul of the details. However, I recently learned about another new business that I don’t consider to have even started with a good idea, but still has managed to attract enough capital to get itself off the ground (“Should Breast Milk Be Nutritionally Analyzed?” by Laura Johannes, The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 28, 2015).

I’m sure you have seen some new mothers who were concerned that their breast milk was not enough for their babies. But how many of them would pay $150 for a start-up kit and then more than $300 to find out the nutritional content of their breast milk? What if it meant pumping and freezing three samples 2 or 3 days apart and then shipping them in a cooler to a lab? What if you told them that neither you nor anyone else could reliably interpret the results because there aren’t any published guidelines for the optimal composition of human breast milk? Even if your practice is packed to the rafters with anxiety-driven, irrational parents, I don’t think you would find many takers. But that doesn’t seem to have bothered the folks who have invested in Happy Vitals, a company in Washington that is offering a service similar to the one I have just described.

You and I might not have invested in a company whose business plan was to offer such a service. But I fear there may be enough health care “providers” practicing without the benefit of an evidence-based education that what I consider a capital misadventure may actually be able to pay back its investors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

A few years ago I wrote a column about what promised to be an exciting development in blood testing technology. Using the money her parents had set aside for her education, a young woman dropped out of Stanford University at age 19 and started a company that she claimed would be able to offer hundreds of lab tests on just a few drops of blood. Results would be available in just minutes instead of hours or days. At the time I wrote the column, the company had just landed a contract with a large drug store chain with an arrangement that would eventually allow nearly every resident of the United States to be within a few miles of a site that would offer rapid response blood tests with nothing more than a finger prick.

It seemed a little hard to believe, but the prospect of pediatricians being able to make a diagnosis without running the risk of exsanguinating our smallest patients sounded appealing. On the other hand, I worried that a quick and easy technology might encourage some physicians to use a shotgun approach to diagnosing illness rather than a more rational and cost-effective process based on the traditional skills of history taking and physical examination. Some patients who foolishly wanted to know “everything” about themselves might be tempted to ask their physicians to order the whole smorgasbord of tests. “Hey, it’s only a few drops of blood.”

Turns out there were enough people with more money than reservations and the company quickly attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital. The company, now calling itself Theranos, has been valued at nine billion dollars. But, recently this startup star has encountered some serious bumps in the road to a full-scale launch (“Hot Startup Theranos Has Struggled With Its Blood-Test Technology” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015). The Wall Street Journal reported that despite promises, only a few of the 240 tests offered by the company are currently performed using their proprietary microtechnique. In the days following the Journal article, the Food and Drug Administration warned Theranos that their “nanotainer” is considered a new medical device that must first clear the agency’s time consuming and costly vetting process (“Hot Startup Theranos Dials Back Lab Tests at FDA’s Behest” by John Carreyrou, The Wall Street Journal, updated Oct. 16, 2015).

The venture capitalists who had climbed on the Theranos bandwagon tempted by the just-a-few-drops promise may end up seeing their bank accounts hemorrhage. But I don’t think we should be too critical of their investment decision. It was and may still be good idea that has simply run afoul of the details. However, I recently learned about another new business that I don’t consider to have even started with a good idea, but still has managed to attract enough capital to get itself off the ground (“Should Breast Milk Be Nutritionally Analyzed?” by Laura Johannes, The Wall Street Journal, Dec. 28, 2015).

I’m sure you have seen some new mothers who were concerned that their breast milk was not enough for their babies. But how many of them would pay $150 for a start-up kit and then more than $300 to find out the nutritional content of their breast milk? What if it meant pumping and freezing three samples 2 or 3 days apart and then shipping them in a cooler to a lab? What if you told them that neither you nor anyone else could reliably interpret the results because there aren’t any published guidelines for the optimal composition of human breast milk? Even if your practice is packed to the rafters with anxiety-driven, irrational parents, I don’t think you would find many takers. But that doesn’t seem to have bothered the folks who have invested in Happy Vitals, a company in Washington that is offering a service similar to the one I have just described.

You and I might not have invested in a company whose business plan was to offer such a service. But I fear there may be enough health care “providers” practicing without the benefit of an evidence-based education that what I consider a capital misadventure may actually be able to pay back its investors.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.”

Subcorneal Hematomas in Excessive Video Game Play

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

Case Report

A 19-year-old man was admitted to our hospital to begin treatment for acute myeloid leukemia that had been diagnosed 2 days prior. Three days after completing a 10-day regimen of induction chemotherapy, he developed bilateral, well-demarcated erythematous patches on the palmar surfaces of the proximal phalanges of the third, fourth, and fifth fingers (Figure 1) and 2 patches on the right palm. The patient was referred to dermatology for evaluation. He recalled no trauma to these sites although he reported pushing his intravenous pole with the right hand when walking. Of note, he had become neutropenic and thrombocytopenic following chemotherapy

On physical examination, the patches measured 1- to 1.5-cm in diameter and were mildly tender to palpation. The 2 patches on the right palm were much smaller than those on the fingers but were otherwise similar in appearance.

A punch biopsy of the erythematous lesion on the left third digit was performed. Histologic examination revealed extensive epidermal denudation associated with vascular proliferation and congestion as well as hemorrhage and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate (Figures 2–4). There was no evidence of a leukemic infiltrate, and stains for fungal elements and bacteria were negative. Eccrine ducts appeared normal with no evidence of necrosis or metaplasia. These findings were suggestive of a frictional etiology.

Due to the distribution of the skin lesions on the hands, it was suspected that the source of friction was a video game controller. Although the patient denied playing video games since his admission to the hospital, he reported heavy video game use during the weeks prior to admission. We postulated that the thrombocytopenia the patient developed following chemotherapy along with prior friction injury sustained from heavy video game play led to traumatic subcorneal hemorrhage on the hands at the points of contact with the video game controller (Figure 5). The subcorneal hematomas resolved completely over the next 2 months during which the patient abstained from video game play.

This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a detailed patient history, as our patient’s history of video game play prior to hospitalization proved to be of major diagnostic importance. Although the location, distribution, and well-demarcated nature of the patient’s lesions suggested an external source of trauma and biopsy definitively ruled out leukemia cutis, Sweet syndrome, and eccrine hidradenitis,1 the final diagnosis of traumatic subcorneal hematomas was only possible with specific knowledge of the patient’s video game controller use.

Comment

History of video game play has been key to the diagnosis of a variety of cutaneous lesions documented in the medical literature. Robertson et al2 attributed a similar case of traumatic subcorneal hematomas of the hands in an otherwise healthy 16-year-old boy to excessive use of a video game controller. Similarly, Kasraee et al3 attributed a case of idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis in an otherwise healthy 12-year-old girl to excessive video game use. In both of these reported cases, bilateral skin lesions on the palms of the hands appeared acutely in a pattern consistent with the points of contact of a video game controller. Excessive video game play has also been associated with unilateral dermatologic lesions on the hands, such as knuckle pads,4 onycholysis,5 friction blisters,6 pressure ulcers,7 and hemorrhagic lesions.5,6,8

Video game–related pathologies are not limited to the skin and have been implicated in a variety of clinical presentations. In 1987, Osterman et al9 published an early account of repetitive strain injury (RSI) related to video game use in which the investigators reported 2 cases of video game–related volar flexor tenosynovitis (or trigger finger), which they termed “joystick digit.” Since that time, video game play has greatly evolved along with the types and nature of RSI cases reported in the medical literature. In 1990, Brasington10 described acute tendinopathy of the extensor pollicis longus tendon caused by excessive video game play, which was termed “Nintendinitis.” This term has since been used in reference to any video game–related RSI and reports have increased over time, likely due to the proliferation of an increasing array of video game systems.5,11-16 In recent years, a number of traumatic injuries including fractures, joint dislocations, head injuries, hemothorax, and lacerations have been attributed to interactive gaming systems.6,11,17-20 In rare cases, video game play also has been associated with enuresis,21 encopresis,22 and epilepsy.23

According to a 2011 report from the Entertainment Software Association, women over the age of 18 years now represent a greater proportion of the video game–playing population than boys aged 17 years and younger.24 This same report also noted that the average video game player is 35 years old; 44% of all players are female; and 27% of Americans over the age of 50 years play video games. This shifting demographic data, including the fact that 80% of American households reportedly play video games, reveals the expanding depth and breadth of the market.24 However, the pediatric population is still a high-volume player demographic. Average time per session peaks between 10 to 12 years of age and then falls through the teenage and adults years.24 Hence, the pediatric population is at high risk for clinical pathology because of the increased repetitive movements associated with video game play. Overall, cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

1. Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier Health Sciences UK; 2007.

2. Robertson SJ, Leonard J, Chamberlain AJ. PlayStation purpura. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:220-222.

3. Kasraee B, Masouyé I, Piguet V. PlayStation palmar hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:892-894.

4. Rushing ME, Sheehan DJ, Davis LS. Video game induced knuckle pad. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:455-457.

5. Bakos RM, Bakos L. Use of dermoscopy to visualize punctate hemorrhages and onycholysis in “playstation thumb.” Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1664-1665.

6. Wood DJ. The “How!” sign—a central palmar blister induced by overplaying on a Nintendo console. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:288.

7. Koh TH. Ulcerative “nintendinitis”: a new kind of repetitive strain injury. Med J Aust. 2000;173:671.

8. Bernabeu-Wittel J, Domínguez-Cruz J, Zulueta T, et al. Hemorrhagic parallel-ridge pattern on dermoscopy in “Playstation fingertip.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:238-239.

9. Osterman AL, Weinberg P, Miller G. Joystick digit. JAMA. 1987;257:782.

10. Brasington R. Nintendinitis. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473-1474.

11. Sparks DA, Coughlin LM, Chase DM. Did too much Wii cause your patient’s injury? J Fam Pract. 2011;60:404-409.

12. Bright DA, Bringhurst DC. Nintendo elbow. West J Med. 1992;156:667-668.

13. Vaidya HJ. Playstation thumb. Lancet. 2004;363:1080.

14. Bonis J. Acute Wiiitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2431-2432.

15. Boehm KM, Pugh A. A new variant of Wiiitis [published online ahead of print June 13, 2008]. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:80.

16. Beddy P, Dunne R, de Blacam C. Achilles wiiitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:W79.

17. Eley KA. A Wii fracture. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:473-474.

18. Wells JJ. An 8-year-old girl presented to the ER after accidentally being hit by a Wii remote control swung by her brother. J Trauma. 2008;65:1203.

19. Fysh T, Thompson JF. A Wii problem. J R Soc Med. 2009;102:502.

20. George AJ. Musculo-ske Wii tal medicine. Injury. 2012;43:390-391.

21. Schink JC. Nintendo enuresis. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:1094.

22. Corkery JC. Nintendo power. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144:959.

23. Hart EJ. Nintendo epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1473.

24. Entertainment Software Association. 2015 sales, demographic, and usage data. essential facts about the computer and video game industry. Entertainment Software Association Web site. http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf. Accessed October 16, 2015.

Practice Points

- Video game play has been reported as an etiologic factor in multiple musculoskeletal and dermatologic conditions.

- More than two-thirds of US children aged 2 to 18 years live in a home with a video game system.

- Cognizance of the popularity of video games and related pathologies can be an asset for dermatologists who evaluate pediatric patients.

Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

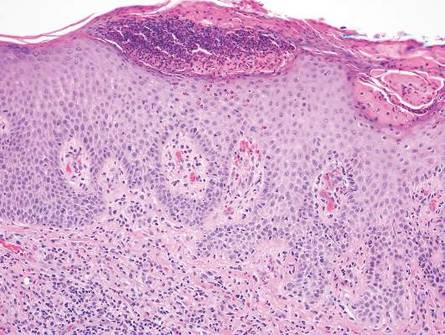

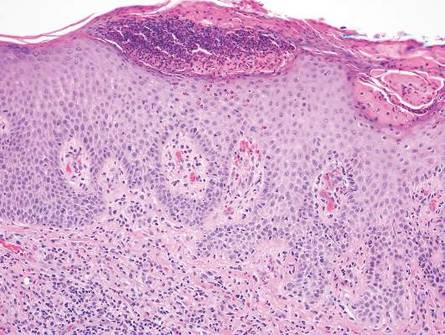

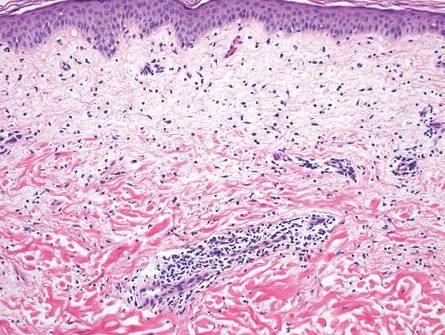

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

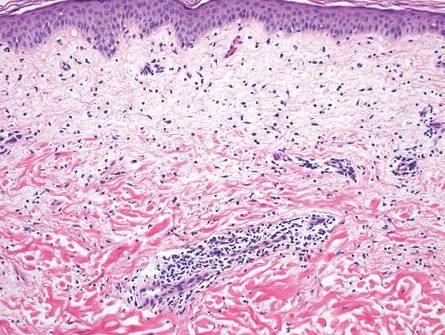

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;3:595-599.

- Miteva M, Elsner P, Ziemer M. A histopathologic study of arthropod bite reactions in 20 patients highlights relevant adnexal involvement. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:26-33.

- Winkelmann RK, Reizner GT. Diffuse dermal neutrophilia in urticarial. Human Pathol. 1988;19:389-393.

- Sepehr A, Wenson S, Tahan SR. Histopathologic manifestations of systemic diseases: the example of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37 (suppl 1):112-124.

- Flowers H, Brodell R, Brents M, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: presentation, diagnosis, and management. South Med J. 2014;107:724-727.

- Fernandes NF, Rozdeba PJ, Schwartz RA, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta: a disease spectrum. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:257-261.

Positive music produces more negative emotions in bipolar

Patients with bipolar disorder might experience more complex negative emotions in response to positive music than typical adults, even when in a euthymic state, Dr. Sabine Choppin of the University of Rennes 1 (France) and colleagues reported.

Researchers recruited 21 patients with bipolar disorder in a euthymic phase and 21 matched healthy controls for the study. First, participants rated their emotional reactivity on two self-report scales: the Emotion Reactivity Scale (ERS) and the Multidimensional Assessment of Thymic States Scale (MAThyS). Next, they used headphones to listen to a series of 12 instrumental music excerpts lasting 45 seconds each with their eyes closed. After each musical selection, they were asked to rate how strongly they had experienced each of the nine emotional categories on the Geneva Emotional Music Scale: joy, sadness, tension, wonder, peacefulness, power, tenderness, nostalgia, and transcendence.

Statistical analyses showed that patients in the bipolar disorder group had a mean score of 41.2 on the ERS, compared with a mean score of 22.9 among healthy controls. In addition, bipolar disorder patients reported experiencing more tension and sadness than did healthy controls when listening to positive musical excerpts that had been classified as inducing joy and wonder.

“This finding tallies with the negative emotional bias displayed by depressed patients, who tend to experience more negative emotions than healthy controls,” the authors wrote. “Bipolar patients struggle so much to regulate their own positive emotions that it creates a chronic source of distress, which could be experienced as a negative emotion.”

Read the article in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2016 Feb;191:15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.063).

Patients with bipolar disorder might experience more complex negative emotions in response to positive music than typical adults, even when in a euthymic state, Dr. Sabine Choppin of the University of Rennes 1 (France) and colleagues reported.

Researchers recruited 21 patients with bipolar disorder in a euthymic phase and 21 matched healthy controls for the study. First, participants rated their emotional reactivity on two self-report scales: the Emotion Reactivity Scale (ERS) and the Multidimensional Assessment of Thymic States Scale (MAThyS). Next, they used headphones to listen to a series of 12 instrumental music excerpts lasting 45 seconds each with their eyes closed. After each musical selection, they were asked to rate how strongly they had experienced each of the nine emotional categories on the Geneva Emotional Music Scale: joy, sadness, tension, wonder, peacefulness, power, tenderness, nostalgia, and transcendence.

Statistical analyses showed that patients in the bipolar disorder group had a mean score of 41.2 on the ERS, compared with a mean score of 22.9 among healthy controls. In addition, bipolar disorder patients reported experiencing more tension and sadness than did healthy controls when listening to positive musical excerpts that had been classified as inducing joy and wonder.

“This finding tallies with the negative emotional bias displayed by depressed patients, who tend to experience more negative emotions than healthy controls,” the authors wrote. “Bipolar patients struggle so much to regulate their own positive emotions that it creates a chronic source of distress, which could be experienced as a negative emotion.”

Read the article in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2016 Feb;191:15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.063).

Patients with bipolar disorder might experience more complex negative emotions in response to positive music than typical adults, even when in a euthymic state, Dr. Sabine Choppin of the University of Rennes 1 (France) and colleagues reported.

Researchers recruited 21 patients with bipolar disorder in a euthymic phase and 21 matched healthy controls for the study. First, participants rated their emotional reactivity on two self-report scales: the Emotion Reactivity Scale (ERS) and the Multidimensional Assessment of Thymic States Scale (MAThyS). Next, they used headphones to listen to a series of 12 instrumental music excerpts lasting 45 seconds each with their eyes closed. After each musical selection, they were asked to rate how strongly they had experienced each of the nine emotional categories on the Geneva Emotional Music Scale: joy, sadness, tension, wonder, peacefulness, power, tenderness, nostalgia, and transcendence.

Statistical analyses showed that patients in the bipolar disorder group had a mean score of 41.2 on the ERS, compared with a mean score of 22.9 among healthy controls. In addition, bipolar disorder patients reported experiencing more tension and sadness than did healthy controls when listening to positive musical excerpts that had been classified as inducing joy and wonder.

“This finding tallies with the negative emotional bias displayed by depressed patients, who tend to experience more negative emotions than healthy controls,” the authors wrote. “Bipolar patients struggle so much to regulate their own positive emotions that it creates a chronic source of distress, which could be experienced as a negative emotion.”

Read the article in the Journal of Affective Disorders (2016 Feb;191:15-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.063).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Dr. Hospitalist: HM Groups Must Adapt to New Career Landscape

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Over the past several years, we have had a problem with physician retention, especially with nocturnists, in our medium-sized hospitalist group. Do you have any suggestions (beyond the obvious “more money”) to help us retain our hospitalists?

Missing My Friends in the Midwest

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Since its inception, hospital medicine has been a very attractive field for practicing medicine, and although growth was phenomenal for many years (especially 2000–2010), it has leveled off over the past five years. With this exceptional growth have come increased salaries, geographically diverse job locations, and more opportunities for career development.

One of the most significant changes over the past 10 years is that hospital medicine is no longer seen as a bridge from residency to fellowship or as a stopover while waiting on the ideal job. Physicians now see hospital medicine as a career choice and are more likely to search for the “ideal” hospitalist job.

Although competitive salaries are important and a necessary starting point, to attract and keep career hospitalists, HM groups (HMGs) will need to offer opportunities for professional growth and leadership as well as flexible schedules.

Many larger HMGs offer several different schedule models, from the ubiquitous seven-on/seven-off schedule (54%, according to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report) to the more traditional five-day workweek with vacation time. Many also choose to work part- or full-time as a nocturnist and, in doing so, earn substantially more money (15%–20% differential). The flexible schedule and the ability to work part- or full-time have been very attractive to those clinicians just starting families or attaining another degree (MBAs are becoming very popular).

While there have always been the “check-in, check-out” docs who did their seven and didn’t want to be bothered during their time off, there were typically enough gunners around to pick up the slack. With the Millennial generation’s pervasive aim for work-life balance, it might become more difficult to find even a few who are willing to go the extra mile in hopes of career advancement. Mix in a very robust job market with a proclivity to travel, and you have a recipe for high attrition.

Like any new profession or specialty, HM will have to evolve and adjust to keep these new docs anchored. We will need to consider offering vacation time, especially for those who are willing to work a traditional Monday–Friday schedule. For those in academia with an interest in promotion, there should be real opportunities for advancement instead of the traditional “time in rank” and other nebulous requirements. There should be robust mentoring for all docs and especially for those just out of residency. The clinicians who express an interest in having an office in the C-Suite should be given a clear path and guidance.

I think with some innovation and recognition, most HMGs will have little problem retaining high-quality physicians. We must also recognize a changing value system and accept that some people will change jobs just because! TH

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Over the past several years, we have had a problem with physician retention, especially with nocturnists, in our medium-sized hospitalist group. Do you have any suggestions (beyond the obvious “more money”) to help us retain our hospitalists?

Missing My Friends in the Midwest

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Since its inception, hospital medicine has been a very attractive field for practicing medicine, and although growth was phenomenal for many years (especially 2000–2010), it has leveled off over the past five years. With this exceptional growth have come increased salaries, geographically diverse job locations, and more opportunities for career development.

One of the most significant changes over the past 10 years is that hospital medicine is no longer seen as a bridge from residency to fellowship or as a stopover while waiting on the ideal job. Physicians now see hospital medicine as a career choice and are more likely to search for the “ideal” hospitalist job.

Although competitive salaries are important and a necessary starting point, to attract and keep career hospitalists, HM groups (HMGs) will need to offer opportunities for professional growth and leadership as well as flexible schedules.

Many larger HMGs offer several different schedule models, from the ubiquitous seven-on/seven-off schedule (54%, according to the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine report) to the more traditional five-day workweek with vacation time. Many also choose to work part- or full-time as a nocturnist and, in doing so, earn substantially more money (15%–20% differential). The flexible schedule and the ability to work part- or full-time have been very attractive to those clinicians just starting families or attaining another degree (MBAs are becoming very popular).

While there have always been the “check-in, check-out” docs who did their seven and didn’t want to be bothered during their time off, there were typically enough gunners around to pick up the slack. With the Millennial generation’s pervasive aim for work-life balance, it might become more difficult to find even a few who are willing to go the extra mile in hopes of career advancement. Mix in a very robust job market with a proclivity to travel, and you have a recipe for high attrition.

Like any new profession or specialty, HM will have to evolve and adjust to keep these new docs anchored. We will need to consider offering vacation time, especially for those who are willing to work a traditional Monday–Friday schedule. For those in academia with an interest in promotion, there should be real opportunities for advancement instead of the traditional “time in rank” and other nebulous requirements. There should be robust mentoring for all docs and especially for those just out of residency. The clinicians who express an interest in having an office in the C-Suite should be given a clear path and guidance.

I think with some innovation and recognition, most HMGs will have little problem retaining high-quality physicians. We must also recognize a changing value system and accept that some people will change jobs just because! TH

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Over the past several years, we have had a problem with physician retention, especially with nocturnists, in our medium-sized hospitalist group. Do you have any suggestions (beyond the obvious “more money”) to help us retain our hospitalists?

Missing My Friends in the Midwest

Dr. Hospitalist responds: