User login

Distal Ulna Fracture With Delayed Ulnar Nerve Palsy in a Baseball Player

Ulnar nerve injury leads to clawing of the ulnar digits and loss of digital abduction and adduction because of paralysis of the ulnar innervated extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Isolated motor paralysis without sensory deficit can occur from compression within the Guyon canal.1 Cubital tunnel at the elbow is the most common site for ulnar nerve compression.2 Compression at both levels can be encountered in sports-related activities. Nerve compression in the Guyon canal can occur with bicycling and is known as cyclist’s palsy,3-6 but it can also develop from canoeing.7 Cubital tunnel syndrome is the most common neuropathy of the elbow among throwing athletes, especially in baseball pitchers and can result from nerve traction and compression within the fibro-osseous tunnel or subluxation out of the tunnel.2 Both compression syndromes can develop from repetitive stress and/or pressure to the nerve in the retrocondylar groove.

Ulnar nerve palsy may be associated with forearm fractures, which is usually caused by simultaneous ulna and radius fractures, especially in children.8-12 To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of an ulnar nerve palsy associated with an isolated ulnar shaft fracture in an adult. We report a case of delayed ulnar nerve palsy after an ulnar shaft fracture in a baseball player. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 19-year-old, right hand–dominant college baseball player was batting right-handed in an intrasquad scrimmage when a high and inside pitched ball from a right-handed pitcher struck the volar-ulnar aspect of his right forearm. Examination in the training room and emergency department revealed moderate swelling and ecchymosis over the distal third of the ulna. He had a normal neurovascular examination, including normal sensation to light touch and normal finger abduction/adduction and wrist flexion/extension. He was otherwise healthy. Radiographs of the right forearm showed a minimally displaced transverse fracture of the distal third of the ulna (Figures 1A, 1B).

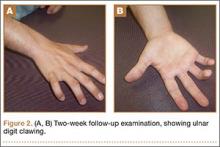

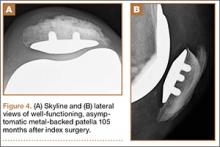

The patient was initially treated with a well-padded, removable, long-arm posterior splint for 2 weeks with serial examinations each day in the training room. At 2-week follow-up, he reported less pain and swelling but stated that his hand had “felt funny” the past several days. Examination revealed clawing of the ulnar digits with paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution (Figures 2A, 2B). His extrinsic muscle function was normal. Radiographs showed stable fracture alignment. Ulnar neuropathy was diagnosed, and treatment was observation with a plan for electromyography (EMG) at 6 weeks after injury if there were no signs of nerve recovery. Physical therapy was instituted and focused on improving intrinsic muscle and proprioceptive functions with the goal of an expeditious, but safe, return to playing baseball. Three weeks after his injury, the patient had decreased tenderness at his fracture site and was given a forearm pad and sleeve for light, noncontact baseball activity (Figure 3). A long velcro wrist splint was used during conditioning and when not playing baseball. Forearm supination and pronation were limited initially because of patient discomfort and to prevent torsional fracture displacement or delayed healing. Six weeks after his injury, the patient returned to hitting and was showing early signs of improved sensation and intrinsic hand strength. He had progressed to a light throwing program and reported difficult hand coordination, poor ball control, and overall difficulty in accurately throwing over the next 3 to 4 months. Because of his difficulty with ball control, the patient began a progressive return to full-game activity over 6 weeks, which initially included a return to batting only, then playing in the outfield, and, eventually, a return to his normal position in the infield. Serial radiographs continued to show good fracture alignment with appropriate new bone formation (Figures 4A, 4B). Normal motor strength was noted at 3 months after injury and normal sensation at 4 months after injury.

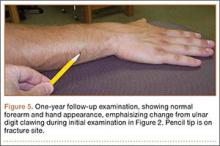

By the end of his summer league, 6 months after his injury, the patient was named Most Valuable Player and had a batting average over .400. He reported near-normal hand function. One year after injury, his examination revealed normal hand function (Figure 5), including normal sensation to light touch, 5/5 intrinsic hand function, and symmetric grip strength. Radiographs showed a healed fracture (Figures 6A, 6B). The patient has gone on to play more than 9 years of professional baseball.

Discussion

The ulnar nerve has a course that runs down the volar compartment of the distal forearm. The flexor carpi ulnaris provides coverage to the nerve in this area. Proximal to the wrist, the nerve emerges from under the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and passes deep to the flexor retinaculum, which is the distal extension of the antebrachial fascia and blends distally into the palmar carpal ligament.13 In our patient, the most likely cause of this presentation of ulnar neuropathy was the direct blow to the nerve from the high-intensity impact of a thrown baseball to this superficial and exposed area of the forearm. Since the patient presented with delayed paresthesias and ulnar clawing 2 weeks after injury, possible contributing causes could be evolving pressure or nerve damage from a perineural hematoma and/or intraneural hematoma or increased local pressure from intramuscular hemorrhage.14 There are both acute and chronic cases of ulnar nerve entrapment by bone or scar tissue that resolved by surgical decompression.8-12 Surgical exploration was not deemed necessary in our case because the fracture was minimally displaced, and the patient regained sensation and motor function over the course of 3 to 4 months.

Nerve injuries can be classified as neurapraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis. Neurapraxia is the mildest form of nerve injury and neurotmesis the most severe. Neurapraxia may be associated with a temporary block to conduction or nerve demyelination without axonal disruption. Spontaneous recovery takes 2 weeks to 2 months. Axonotmesis involves an actual loss of axonal continuity; however, connective tissue supporting structures remain intact and allow axonal regeneration. Finally, neurotmesis is transection of the peripheral nerve, and spontaneous regeneration is not possible. The mechanism of injury in our patient suggests that the pathology was neurapraxia.1,15

Management of these injuries should proceed according to basic extremity injury–care practices. Initial care should include thorough neurovascular and radiographic evaluations. If nerve deficits are present with a closed injury and minimal fracture displacement, treatment can include observation and serial examinations with a baseline EMG, or waiting until 4 to 6 weeks after injury to obtain an EMG if there are no signs of nerve recovery. Early EMG testing and surgical exploration may be warranted if there is a concern for nerve disruption or entrapment, such as marked fracture displacement or an open injury. Additional early-care measures should include swelling control modalities and immobilization based on the type of fracture. Ultrasound was not readily available at the time of our patient’s injury, but it may be a helpful adjunct in guiding decision-making regarding whether to perform early surgical exploration for hematoma evacuation or nerve injury.16-18 Our case report was intended to provide an awareness of the unusual association between an isolated ulnar shaft fracture and a delayed ulnar nerve palsy in an athlete. Nerve injuries may be unrecognized in some patients in a trauma situation, since the focus is usually on the fracture and the typical patient does not have to return to high-demand, coordinated athletic activity, such as throwing a ball. Because of the possible delayed presentation of these nerve injuries, close observation of nerve function after ulna fractures from blunt trauma is warranted.

1. Dhillon MS, Chu ML, Posner MA. Demyelinating focal motor neuropathy of the ulnar nerve masquerading as compression in Guyon’s canal: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(1):48-51.

2. Hariri S, McAdams TR. Nerve injuries about the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):655-675.

3. Akuthota V, Plastaras C, Lindberg K, Tobey J, Press J, Garvan C. The effect of long-distance bicycling on ulnar and median nerves: an electrophysiologic evaluation of cyclist palsy. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(8):1224-1230.

4. Capitani D, Beer S. Handlebar palsy--a compression syndrome of the deep terminal (motor) branch of the ulnar nerve in biking. J Neurol. 2002;249(10):1441-1445.

5. Patterson JM, Jaggars MM, Boyer MI. Ulnar and median nerve palsy in long-distance cyclists. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):585-589.

6. Slane J, Timmerman M, Ploeg HL, Thelen DG. The influence of glove and hand position on pressure over the ulnar nerve during cycling. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;26(6):642-648.

7. Paul F, Diesta FJ, Ratzlaff T, Vogel HP, Zipp F. Combined ulnar nerve palsy in Guyon’s canal and distal median nerve irritation following excessive canoeing. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118(4):e81-e82.

8. Hirasawa H, Sakai A, Toba N, Kamiuttanai M, Nakamura T, Tanaka K. Bony entrapment of ulnar nerve after closed forearm fracture: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2004;12(1):122-125.

9. Dahlin LB, Düppe H. Injuries to the nerves associated with fractured forearms in children. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2007;41(4):207-210.

10. Neiman R, Maiocco B, Deeney VF. Ulnar nerve injury after closed forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18(5):683-685.

11. Pai VS. Injury of the ulnar nerve associated with fracture of the ulna: A case report. J Orthop Surgery. 1999;7(2):73.

12. Suganuma S, Tada K, Hayashi H, Segawa T, Tsuchiya H. Ulnar nerve palsy associated with closed midshaft forearm fractures. Orthopedics. 2012;35(11):e1680-e1683.

13. Ombaba J, Kuo M, Rayan G. Anatomy of the ulnar tunnel and the influence of wrist motion on its morphology. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35A:760-768.

14. Vijayakumar R, Nesathurai S, Abbott KM, Eustace S. Ulnar neuropathy resulting from diffuse intramuscular hemorrhage: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(8):1127-1130.

15. Browner, Bruce. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction [eBook]. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2009:1487.

16. Koenig RW, Pedro MT, Heinen CP, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in evaluating peripheral nerve entrapment and trauma. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26(2):E13.

17. Zhu J, Liu F, Li D, Shao J, Hu B. Preliminary study of the types of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries by ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(5):1097-1101.

18. Lee FC, Singh H, Nazarian LN, Ratliff JK. High-resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intra-operative management of peripheral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):206-221.

Ulnar nerve injury leads to clawing of the ulnar digits and loss of digital abduction and adduction because of paralysis of the ulnar innervated extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Isolated motor paralysis without sensory deficit can occur from compression within the Guyon canal.1 Cubital tunnel at the elbow is the most common site for ulnar nerve compression.2 Compression at both levels can be encountered in sports-related activities. Nerve compression in the Guyon canal can occur with bicycling and is known as cyclist’s palsy,3-6 but it can also develop from canoeing.7 Cubital tunnel syndrome is the most common neuropathy of the elbow among throwing athletes, especially in baseball pitchers and can result from nerve traction and compression within the fibro-osseous tunnel or subluxation out of the tunnel.2 Both compression syndromes can develop from repetitive stress and/or pressure to the nerve in the retrocondylar groove.

Ulnar nerve palsy may be associated with forearm fractures, which is usually caused by simultaneous ulna and radius fractures, especially in children.8-12 To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of an ulnar nerve palsy associated with an isolated ulnar shaft fracture in an adult. We report a case of delayed ulnar nerve palsy after an ulnar shaft fracture in a baseball player. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 19-year-old, right hand–dominant college baseball player was batting right-handed in an intrasquad scrimmage when a high and inside pitched ball from a right-handed pitcher struck the volar-ulnar aspect of his right forearm. Examination in the training room and emergency department revealed moderate swelling and ecchymosis over the distal third of the ulna. He had a normal neurovascular examination, including normal sensation to light touch and normal finger abduction/adduction and wrist flexion/extension. He was otherwise healthy. Radiographs of the right forearm showed a minimally displaced transverse fracture of the distal third of the ulna (Figures 1A, 1B).

The patient was initially treated with a well-padded, removable, long-arm posterior splint for 2 weeks with serial examinations each day in the training room. At 2-week follow-up, he reported less pain and swelling but stated that his hand had “felt funny” the past several days. Examination revealed clawing of the ulnar digits with paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution (Figures 2A, 2B). His extrinsic muscle function was normal. Radiographs showed stable fracture alignment. Ulnar neuropathy was diagnosed, and treatment was observation with a plan for electromyography (EMG) at 6 weeks after injury if there were no signs of nerve recovery. Physical therapy was instituted and focused on improving intrinsic muscle and proprioceptive functions with the goal of an expeditious, but safe, return to playing baseball. Three weeks after his injury, the patient had decreased tenderness at his fracture site and was given a forearm pad and sleeve for light, noncontact baseball activity (Figure 3). A long velcro wrist splint was used during conditioning and when not playing baseball. Forearm supination and pronation were limited initially because of patient discomfort and to prevent torsional fracture displacement or delayed healing. Six weeks after his injury, the patient returned to hitting and was showing early signs of improved sensation and intrinsic hand strength. He had progressed to a light throwing program and reported difficult hand coordination, poor ball control, and overall difficulty in accurately throwing over the next 3 to 4 months. Because of his difficulty with ball control, the patient began a progressive return to full-game activity over 6 weeks, which initially included a return to batting only, then playing in the outfield, and, eventually, a return to his normal position in the infield. Serial radiographs continued to show good fracture alignment with appropriate new bone formation (Figures 4A, 4B). Normal motor strength was noted at 3 months after injury and normal sensation at 4 months after injury.

By the end of his summer league, 6 months after his injury, the patient was named Most Valuable Player and had a batting average over .400. He reported near-normal hand function. One year after injury, his examination revealed normal hand function (Figure 5), including normal sensation to light touch, 5/5 intrinsic hand function, and symmetric grip strength. Radiographs showed a healed fracture (Figures 6A, 6B). The patient has gone on to play more than 9 years of professional baseball.

Discussion

The ulnar nerve has a course that runs down the volar compartment of the distal forearm. The flexor carpi ulnaris provides coverage to the nerve in this area. Proximal to the wrist, the nerve emerges from under the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and passes deep to the flexor retinaculum, which is the distal extension of the antebrachial fascia and blends distally into the palmar carpal ligament.13 In our patient, the most likely cause of this presentation of ulnar neuropathy was the direct blow to the nerve from the high-intensity impact of a thrown baseball to this superficial and exposed area of the forearm. Since the patient presented with delayed paresthesias and ulnar clawing 2 weeks after injury, possible contributing causes could be evolving pressure or nerve damage from a perineural hematoma and/or intraneural hematoma or increased local pressure from intramuscular hemorrhage.14 There are both acute and chronic cases of ulnar nerve entrapment by bone or scar tissue that resolved by surgical decompression.8-12 Surgical exploration was not deemed necessary in our case because the fracture was minimally displaced, and the patient regained sensation and motor function over the course of 3 to 4 months.

Nerve injuries can be classified as neurapraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis. Neurapraxia is the mildest form of nerve injury and neurotmesis the most severe. Neurapraxia may be associated with a temporary block to conduction or nerve demyelination without axonal disruption. Spontaneous recovery takes 2 weeks to 2 months. Axonotmesis involves an actual loss of axonal continuity; however, connective tissue supporting structures remain intact and allow axonal regeneration. Finally, neurotmesis is transection of the peripheral nerve, and spontaneous regeneration is not possible. The mechanism of injury in our patient suggests that the pathology was neurapraxia.1,15

Management of these injuries should proceed according to basic extremity injury–care practices. Initial care should include thorough neurovascular and radiographic evaluations. If nerve deficits are present with a closed injury and minimal fracture displacement, treatment can include observation and serial examinations with a baseline EMG, or waiting until 4 to 6 weeks after injury to obtain an EMG if there are no signs of nerve recovery. Early EMG testing and surgical exploration may be warranted if there is a concern for nerve disruption or entrapment, such as marked fracture displacement or an open injury. Additional early-care measures should include swelling control modalities and immobilization based on the type of fracture. Ultrasound was not readily available at the time of our patient’s injury, but it may be a helpful adjunct in guiding decision-making regarding whether to perform early surgical exploration for hematoma evacuation or nerve injury.16-18 Our case report was intended to provide an awareness of the unusual association between an isolated ulnar shaft fracture and a delayed ulnar nerve palsy in an athlete. Nerve injuries may be unrecognized in some patients in a trauma situation, since the focus is usually on the fracture and the typical patient does not have to return to high-demand, coordinated athletic activity, such as throwing a ball. Because of the possible delayed presentation of these nerve injuries, close observation of nerve function after ulna fractures from blunt trauma is warranted.

Ulnar nerve injury leads to clawing of the ulnar digits and loss of digital abduction and adduction because of paralysis of the ulnar innervated extrinsic and intrinsic muscles. Isolated motor paralysis without sensory deficit can occur from compression within the Guyon canal.1 Cubital tunnel at the elbow is the most common site for ulnar nerve compression.2 Compression at both levels can be encountered in sports-related activities. Nerve compression in the Guyon canal can occur with bicycling and is known as cyclist’s palsy,3-6 but it can also develop from canoeing.7 Cubital tunnel syndrome is the most common neuropathy of the elbow among throwing athletes, especially in baseball pitchers and can result from nerve traction and compression within the fibro-osseous tunnel or subluxation out of the tunnel.2 Both compression syndromes can develop from repetitive stress and/or pressure to the nerve in the retrocondylar groove.

Ulnar nerve palsy may be associated with forearm fractures, which is usually caused by simultaneous ulna and radius fractures, especially in children.8-12 To our knowledge, there are no reports in the literature of an ulnar nerve palsy associated with an isolated ulnar shaft fracture in an adult. We report a case of delayed ulnar nerve palsy after an ulnar shaft fracture in a baseball player. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 19-year-old, right hand–dominant college baseball player was batting right-handed in an intrasquad scrimmage when a high and inside pitched ball from a right-handed pitcher struck the volar-ulnar aspect of his right forearm. Examination in the training room and emergency department revealed moderate swelling and ecchymosis over the distal third of the ulna. He had a normal neurovascular examination, including normal sensation to light touch and normal finger abduction/adduction and wrist flexion/extension. He was otherwise healthy. Radiographs of the right forearm showed a minimally displaced transverse fracture of the distal third of the ulna (Figures 1A, 1B).

The patient was initially treated with a well-padded, removable, long-arm posterior splint for 2 weeks with serial examinations each day in the training room. At 2-week follow-up, he reported less pain and swelling but stated that his hand had “felt funny” the past several days. Examination revealed clawing of the ulnar digits with paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution (Figures 2A, 2B). His extrinsic muscle function was normal. Radiographs showed stable fracture alignment. Ulnar neuropathy was diagnosed, and treatment was observation with a plan for electromyography (EMG) at 6 weeks after injury if there were no signs of nerve recovery. Physical therapy was instituted and focused on improving intrinsic muscle and proprioceptive functions with the goal of an expeditious, but safe, return to playing baseball. Three weeks after his injury, the patient had decreased tenderness at his fracture site and was given a forearm pad and sleeve for light, noncontact baseball activity (Figure 3). A long velcro wrist splint was used during conditioning and when not playing baseball. Forearm supination and pronation were limited initially because of patient discomfort and to prevent torsional fracture displacement or delayed healing. Six weeks after his injury, the patient returned to hitting and was showing early signs of improved sensation and intrinsic hand strength. He had progressed to a light throwing program and reported difficult hand coordination, poor ball control, and overall difficulty in accurately throwing over the next 3 to 4 months. Because of his difficulty with ball control, the patient began a progressive return to full-game activity over 6 weeks, which initially included a return to batting only, then playing in the outfield, and, eventually, a return to his normal position in the infield. Serial radiographs continued to show good fracture alignment with appropriate new bone formation (Figures 4A, 4B). Normal motor strength was noted at 3 months after injury and normal sensation at 4 months after injury.

By the end of his summer league, 6 months after his injury, the patient was named Most Valuable Player and had a batting average over .400. He reported near-normal hand function. One year after injury, his examination revealed normal hand function (Figure 5), including normal sensation to light touch, 5/5 intrinsic hand function, and symmetric grip strength. Radiographs showed a healed fracture (Figures 6A, 6B). The patient has gone on to play more than 9 years of professional baseball.

Discussion

The ulnar nerve has a course that runs down the volar compartment of the distal forearm. The flexor carpi ulnaris provides coverage to the nerve in this area. Proximal to the wrist, the nerve emerges from under the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and passes deep to the flexor retinaculum, which is the distal extension of the antebrachial fascia and blends distally into the palmar carpal ligament.13 In our patient, the most likely cause of this presentation of ulnar neuropathy was the direct blow to the nerve from the high-intensity impact of a thrown baseball to this superficial and exposed area of the forearm. Since the patient presented with delayed paresthesias and ulnar clawing 2 weeks after injury, possible contributing causes could be evolving pressure or nerve damage from a perineural hematoma and/or intraneural hematoma or increased local pressure from intramuscular hemorrhage.14 There are both acute and chronic cases of ulnar nerve entrapment by bone or scar tissue that resolved by surgical decompression.8-12 Surgical exploration was not deemed necessary in our case because the fracture was minimally displaced, and the patient regained sensation and motor function over the course of 3 to 4 months.

Nerve injuries can be classified as neurapraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis. Neurapraxia is the mildest form of nerve injury and neurotmesis the most severe. Neurapraxia may be associated with a temporary block to conduction or nerve demyelination without axonal disruption. Spontaneous recovery takes 2 weeks to 2 months. Axonotmesis involves an actual loss of axonal continuity; however, connective tissue supporting structures remain intact and allow axonal regeneration. Finally, neurotmesis is transection of the peripheral nerve, and spontaneous regeneration is not possible. The mechanism of injury in our patient suggests that the pathology was neurapraxia.1,15

Management of these injuries should proceed according to basic extremity injury–care practices. Initial care should include thorough neurovascular and radiographic evaluations. If nerve deficits are present with a closed injury and minimal fracture displacement, treatment can include observation and serial examinations with a baseline EMG, or waiting until 4 to 6 weeks after injury to obtain an EMG if there are no signs of nerve recovery. Early EMG testing and surgical exploration may be warranted if there is a concern for nerve disruption or entrapment, such as marked fracture displacement or an open injury. Additional early-care measures should include swelling control modalities and immobilization based on the type of fracture. Ultrasound was not readily available at the time of our patient’s injury, but it may be a helpful adjunct in guiding decision-making regarding whether to perform early surgical exploration for hematoma evacuation or nerve injury.16-18 Our case report was intended to provide an awareness of the unusual association between an isolated ulnar shaft fracture and a delayed ulnar nerve palsy in an athlete. Nerve injuries may be unrecognized in some patients in a trauma situation, since the focus is usually on the fracture and the typical patient does not have to return to high-demand, coordinated athletic activity, such as throwing a ball. Because of the possible delayed presentation of these nerve injuries, close observation of nerve function after ulna fractures from blunt trauma is warranted.

1. Dhillon MS, Chu ML, Posner MA. Demyelinating focal motor neuropathy of the ulnar nerve masquerading as compression in Guyon’s canal: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(1):48-51.

2. Hariri S, McAdams TR. Nerve injuries about the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):655-675.

3. Akuthota V, Plastaras C, Lindberg K, Tobey J, Press J, Garvan C. The effect of long-distance bicycling on ulnar and median nerves: an electrophysiologic evaluation of cyclist palsy. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(8):1224-1230.

4. Capitani D, Beer S. Handlebar palsy--a compression syndrome of the deep terminal (motor) branch of the ulnar nerve in biking. J Neurol. 2002;249(10):1441-1445.

5. Patterson JM, Jaggars MM, Boyer MI. Ulnar and median nerve palsy in long-distance cyclists. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):585-589.

6. Slane J, Timmerman M, Ploeg HL, Thelen DG. The influence of glove and hand position on pressure over the ulnar nerve during cycling. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;26(6):642-648.

7. Paul F, Diesta FJ, Ratzlaff T, Vogel HP, Zipp F. Combined ulnar nerve palsy in Guyon’s canal and distal median nerve irritation following excessive canoeing. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118(4):e81-e82.

8. Hirasawa H, Sakai A, Toba N, Kamiuttanai M, Nakamura T, Tanaka K. Bony entrapment of ulnar nerve after closed forearm fracture: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2004;12(1):122-125.

9. Dahlin LB, Düppe H. Injuries to the nerves associated with fractured forearms in children. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2007;41(4):207-210.

10. Neiman R, Maiocco B, Deeney VF. Ulnar nerve injury after closed forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18(5):683-685.

11. Pai VS. Injury of the ulnar nerve associated with fracture of the ulna: A case report. J Orthop Surgery. 1999;7(2):73.

12. Suganuma S, Tada K, Hayashi H, Segawa T, Tsuchiya H. Ulnar nerve palsy associated with closed midshaft forearm fractures. Orthopedics. 2012;35(11):e1680-e1683.

13. Ombaba J, Kuo M, Rayan G. Anatomy of the ulnar tunnel and the influence of wrist motion on its morphology. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35A:760-768.

14. Vijayakumar R, Nesathurai S, Abbott KM, Eustace S. Ulnar neuropathy resulting from diffuse intramuscular hemorrhage: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(8):1127-1130.

15. Browner, Bruce. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction [eBook]. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2009:1487.

16. Koenig RW, Pedro MT, Heinen CP, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in evaluating peripheral nerve entrapment and trauma. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26(2):E13.

17. Zhu J, Liu F, Li D, Shao J, Hu B. Preliminary study of the types of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries by ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(5):1097-1101.

18. Lee FC, Singh H, Nazarian LN, Ratliff JK. High-resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intra-operative management of peripheral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):206-221.

1. Dhillon MS, Chu ML, Posner MA. Demyelinating focal motor neuropathy of the ulnar nerve masquerading as compression in Guyon’s canal: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(1):48-51.

2. Hariri S, McAdams TR. Nerve injuries about the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29(4):655-675.

3. Akuthota V, Plastaras C, Lindberg K, Tobey J, Press J, Garvan C. The effect of long-distance bicycling on ulnar and median nerves: an electrophysiologic evaluation of cyclist palsy. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(8):1224-1230.

4. Capitani D, Beer S. Handlebar palsy--a compression syndrome of the deep terminal (motor) branch of the ulnar nerve in biking. J Neurol. 2002;249(10):1441-1445.

5. Patterson JM, Jaggars MM, Boyer MI. Ulnar and median nerve palsy in long-distance cyclists. A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):585-589.

6. Slane J, Timmerman M, Ploeg HL, Thelen DG. The influence of glove and hand position on pressure over the ulnar nerve during cycling. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;26(6):642-648.

7. Paul F, Diesta FJ, Ratzlaff T, Vogel HP, Zipp F. Combined ulnar nerve palsy in Guyon’s canal and distal median nerve irritation following excessive canoeing. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;118(4):e81-e82.

8. Hirasawa H, Sakai A, Toba N, Kamiuttanai M, Nakamura T, Tanaka K. Bony entrapment of ulnar nerve after closed forearm fracture: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2004;12(1):122-125.

9. Dahlin LB, Düppe H. Injuries to the nerves associated with fractured forearms in children. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2007;41(4):207-210.

10. Neiman R, Maiocco B, Deeney VF. Ulnar nerve injury after closed forearm fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18(5):683-685.

11. Pai VS. Injury of the ulnar nerve associated with fracture of the ulna: A case report. J Orthop Surgery. 1999;7(2):73.

12. Suganuma S, Tada K, Hayashi H, Segawa T, Tsuchiya H. Ulnar nerve palsy associated with closed midshaft forearm fractures. Orthopedics. 2012;35(11):e1680-e1683.

13. Ombaba J, Kuo M, Rayan G. Anatomy of the ulnar tunnel and the influence of wrist motion on its morphology. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35A:760-768.

14. Vijayakumar R, Nesathurai S, Abbott KM, Eustace S. Ulnar neuropathy resulting from diffuse intramuscular hemorrhage: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(8):1127-1130.

15. Browner, Bruce. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction [eBook]. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2009:1487.

16. Koenig RW, Pedro MT, Heinen CP, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in evaluating peripheral nerve entrapment and trauma. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;26(2):E13.

17. Zhu J, Liu F, Li D, Shao J, Hu B. Preliminary study of the types of traumatic peripheral nerve injuries by ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(5):1097-1101.

18. Lee FC, Singh H, Nazarian LN, Ratliff JK. High-resolution ultrasonography in the diagnosis and intra-operative management of peripheral nerve lesions. J Neurosurg. 2011;114(1):206-221.

HM16 Takes a Look at Health IT, Post-Acute Care

Take a look at the HM16 program, and you get a snapshot of the most pressing topics in hospital medicine. Specifically, four new educational tracks are being rolled out at this year’s annual meeting, including a new track on the patient-doctor relationship, which is so crucial with today’s growing emphasis on patient satisfaction, and a track focused on perioperative medicine, an important area with a fast-moving frontier. Another new track covers post-acute care, a setting in which more and more hospitalists find themselves practicing. Then there’s the big daddy: health information technology (IT) for hospitalists.

Course Director Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, also points to a new twist in the way the conference will attempt to tackle the tough topic of work-life balance.

Read the full interview with Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM.

Here’s a look at what’s new for HM16 attendees.

Health IT for Hospitalists

“There’s not a hospitalist in the country who’s not affected by IT and updates to their [electronic medical records (EMR)], new adoption of EMR technology, different vendors,” Dr. Mattison says. “We’re always searching for something to make our lives better and make the care that we provide more high quality.”

There will be sessions of a general nature, such as “There’s an App for That,” a review of mobile apps helpful to hospitalists. And there will be those for the more passionate technophiles, such as a session on clinical informatics and “Using IT to Help Drive the Shift from Volume to Value.”

“We’ve spent a lot of time trying to make sure there’s something for everyone,” says Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM, chair of SHM’s IT Committee. “And even within each individual talk, we’ve tried to make sure that there is material that can be applicable from the frontline hospitalist to the CMIO of a hospital.”

Dr. Rogers says the committee has “really been pushing” to have its own track at the annual meeting.

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Rogers.

“Health IT continues to be an area of great frustration and great promise,” he says. “I think most of the frustration that hospitalists have is because they realize the potential of health IT, and they see how far it is from the reality of what they’re working with every day.

“Hospitalists are well-suited for actively being involved in clinical informatics, but many of us would be far more effective in our roles with more formal education and training.”

Post-Acute Care

It’s estimated that as many as 35% of hospitalists work in the post-acute setting. The number very much surprised Dr. Mattison. When she heard of the figure, “[the committee] lobbied very hard to get a track for post-acute care.”

One session, “Building and Managing a PAC Practice,” will review setting up a staff, relevant regulations, billing, and collecting, and it should be of interest to both managers and physicians, says Sean Muldoon, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer of the hospitalist division at Louisville, Ken.–based Kindred Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Task Force.

Another session, “Lost in Transitions,” will review information gaps and propose solutions “to the well-known voltage drop of information that can happen in transfer from the hospital to post-acute care.”

At Kindred, Dr. Muldoon says he has seen the benefits of hospitalist involvement in post-acute care.

“In many markets, we seek out and often are able to become a practice site for a large hospitalist medical group,” he says. “That’s really good for us, the patients, and, we think, the hospitalists because it allows the hospitalists to be exposed to the practice and benefits of post-acute care without having to make a full commitment to be a skilled-nursing physician or a long-term acute-care physician.”

It also makes transitions of care smoother and less disruptive, he says, “because a patient is simply transferred from one hospitalist in a group to another or often maintaining that same hospitalist in the post-acute-care setting.”

Dr. Muldoon says the new track is of value to any hospitalist, whether they actually work in post-acute care or not.

“A hospitalist would be hard-pressed to provide knowledgeable input into where a patient should receive post-acute care without a working knowledge of which patients should be directed to which post-acute-care setting,” he says.

Doctor-Patient Relationship

This topic was a pre-course last year, and organizers decided to make this a full track on the final day of the meeting schedule.

“It’s really about communication style,” Dr. Mattison says. “There’s one session called ‘The Language of Empathy and Engagement: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care.’ There’s one on unconscious biases and our underlying assumptions and how it affects how we care for patients. [Another is focused] on improving the patient experience in the hospital.”

Co-Management/ Perioperative Medicine

“There are a lot of challenges around anticoagulation management, optimizing patients’ physical heath prior to the surgery, what things should we be doing, what medications should we be giving, what ones shouldn’t we be giving,” Dr. Mattison says. “It’s an evolving field that has, every year, new information.”

Hidden Gems

Dr. Mattison draws special attention to “Work-Life Balance: Is It Possible?” (Tuesday, March 8, 4:20–5:40 p.m.). This year, this problem—all too familiar to hospitalists—will be addressed in a panel discussion, which is a change from previous years.

“There’s been, year after year after year, a lot of discussion around, how can I make my job manageable if my boss isn’t listening to me or is not attuned to work-life balance? How can I navigate this process?” she says. “I’m hopeful that the panel discussion will provide people with some real examples and strategies for success.”

She also draws attention to the session “Perioperative Pitfalls: Overcoming Common Challenges in Managing Medical Problems in Surgical Patients” (Monday, March 7, 3:05–4:20 p.m.).

“There are some true leaders in perioperative management, and they’re going to come together and have a panel discussion,” she says. “It’ll be an opportunity to see some of the great minds think, if you will.” TH

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Take a look at the HM16 program, and you get a snapshot of the most pressing topics in hospital medicine. Specifically, four new educational tracks are being rolled out at this year’s annual meeting, including a new track on the patient-doctor relationship, which is so crucial with today’s growing emphasis on patient satisfaction, and a track focused on perioperative medicine, an important area with a fast-moving frontier. Another new track covers post-acute care, a setting in which more and more hospitalists find themselves practicing. Then there’s the big daddy: health information technology (IT) for hospitalists.

Course Director Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, also points to a new twist in the way the conference will attempt to tackle the tough topic of work-life balance.

Read the full interview with Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM.

Here’s a look at what’s new for HM16 attendees.

Health IT for Hospitalists

“There’s not a hospitalist in the country who’s not affected by IT and updates to their [electronic medical records (EMR)], new adoption of EMR technology, different vendors,” Dr. Mattison says. “We’re always searching for something to make our lives better and make the care that we provide more high quality.”

There will be sessions of a general nature, such as “There’s an App for That,” a review of mobile apps helpful to hospitalists. And there will be those for the more passionate technophiles, such as a session on clinical informatics and “Using IT to Help Drive the Shift from Volume to Value.”

“We’ve spent a lot of time trying to make sure there’s something for everyone,” says Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM, chair of SHM’s IT Committee. “And even within each individual talk, we’ve tried to make sure that there is material that can be applicable from the frontline hospitalist to the CMIO of a hospital.”

Dr. Rogers says the committee has “really been pushing” to have its own track at the annual meeting.

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Rogers.

“Health IT continues to be an area of great frustration and great promise,” he says. “I think most of the frustration that hospitalists have is because they realize the potential of health IT, and they see how far it is from the reality of what they’re working with every day.

“Hospitalists are well-suited for actively being involved in clinical informatics, but many of us would be far more effective in our roles with more formal education and training.”

Post-Acute Care

It’s estimated that as many as 35% of hospitalists work in the post-acute setting. The number very much surprised Dr. Mattison. When she heard of the figure, “[the committee] lobbied very hard to get a track for post-acute care.”

One session, “Building and Managing a PAC Practice,” will review setting up a staff, relevant regulations, billing, and collecting, and it should be of interest to both managers and physicians, says Sean Muldoon, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer of the hospitalist division at Louisville, Ken.–based Kindred Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Task Force.

Another session, “Lost in Transitions,” will review information gaps and propose solutions “to the well-known voltage drop of information that can happen in transfer from the hospital to post-acute care.”

At Kindred, Dr. Muldoon says he has seen the benefits of hospitalist involvement in post-acute care.

“In many markets, we seek out and often are able to become a practice site for a large hospitalist medical group,” he says. “That’s really good for us, the patients, and, we think, the hospitalists because it allows the hospitalists to be exposed to the practice and benefits of post-acute care without having to make a full commitment to be a skilled-nursing physician or a long-term acute-care physician.”

It also makes transitions of care smoother and less disruptive, he says, “because a patient is simply transferred from one hospitalist in a group to another or often maintaining that same hospitalist in the post-acute-care setting.”

Dr. Muldoon says the new track is of value to any hospitalist, whether they actually work in post-acute care or not.

“A hospitalist would be hard-pressed to provide knowledgeable input into where a patient should receive post-acute care without a working knowledge of which patients should be directed to which post-acute-care setting,” he says.

Doctor-Patient Relationship

This topic was a pre-course last year, and organizers decided to make this a full track on the final day of the meeting schedule.

“It’s really about communication style,” Dr. Mattison says. “There’s one session called ‘The Language of Empathy and Engagement: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care.’ There’s one on unconscious biases and our underlying assumptions and how it affects how we care for patients. [Another is focused] on improving the patient experience in the hospital.”

Co-Management/ Perioperative Medicine

“There are a lot of challenges around anticoagulation management, optimizing patients’ physical heath prior to the surgery, what things should we be doing, what medications should we be giving, what ones shouldn’t we be giving,” Dr. Mattison says. “It’s an evolving field that has, every year, new information.”

Hidden Gems

Dr. Mattison draws special attention to “Work-Life Balance: Is It Possible?” (Tuesday, March 8, 4:20–5:40 p.m.). This year, this problem—all too familiar to hospitalists—will be addressed in a panel discussion, which is a change from previous years.

“There’s been, year after year after year, a lot of discussion around, how can I make my job manageable if my boss isn’t listening to me or is not attuned to work-life balance? How can I navigate this process?” she says. “I’m hopeful that the panel discussion will provide people with some real examples and strategies for success.”

She also draws attention to the session “Perioperative Pitfalls: Overcoming Common Challenges in Managing Medical Problems in Surgical Patients” (Monday, March 7, 3:05–4:20 p.m.).

“There are some true leaders in perioperative management, and they’re going to come together and have a panel discussion,” she says. “It’ll be an opportunity to see some of the great minds think, if you will.” TH

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Take a look at the HM16 program, and you get a snapshot of the most pressing topics in hospital medicine. Specifically, four new educational tracks are being rolled out at this year’s annual meeting, including a new track on the patient-doctor relationship, which is so crucial with today’s growing emphasis on patient satisfaction, and a track focused on perioperative medicine, an important area with a fast-moving frontier. Another new track covers post-acute care, a setting in which more and more hospitalists find themselves practicing. Then there’s the big daddy: health information technology (IT) for hospitalists.

Course Director Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM, also points to a new twist in the way the conference will attempt to tackle the tough topic of work-life balance.

Read the full interview with Melissa Mattison, MD, SFHM.

Here’s a look at what’s new for HM16 attendees.

Health IT for Hospitalists

“There’s not a hospitalist in the country who’s not affected by IT and updates to their [electronic medical records (EMR)], new adoption of EMR technology, different vendors,” Dr. Mattison says. “We’re always searching for something to make our lives better and make the care that we provide more high quality.”

There will be sessions of a general nature, such as “There’s an App for That,” a review of mobile apps helpful to hospitalists. And there will be those for the more passionate technophiles, such as a session on clinical informatics and “Using IT to Help Drive the Shift from Volume to Value.”

“We’ve spent a lot of time trying to make sure there’s something for everyone,” says Kendall Rogers, MD, SFHM, chair of SHM’s IT Committee. “And even within each individual talk, we’ve tried to make sure that there is material that can be applicable from the frontline hospitalist to the CMIO of a hospital.”

Dr. Rogers says the committee has “really been pushing” to have its own track at the annual meeting.

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Rogers.

“Health IT continues to be an area of great frustration and great promise,” he says. “I think most of the frustration that hospitalists have is because they realize the potential of health IT, and they see how far it is from the reality of what they’re working with every day.

“Hospitalists are well-suited for actively being involved in clinical informatics, but many of us would be far more effective in our roles with more formal education and training.”

Post-Acute Care

It’s estimated that as many as 35% of hospitalists work in the post-acute setting. The number very much surprised Dr. Mattison. When she heard of the figure, “[the committee] lobbied very hard to get a track for post-acute care.”

One session, “Building and Managing a PAC Practice,” will review setting up a staff, relevant regulations, billing, and collecting, and it should be of interest to both managers and physicians, says Sean Muldoon, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer of the hospitalist division at Louisville, Ken.–based Kindred Healthcare and chair of SHM’s Post-Acute Care Task Force.

Another session, “Lost in Transitions,” will review information gaps and propose solutions “to the well-known voltage drop of information that can happen in transfer from the hospital to post-acute care.”

At Kindred, Dr. Muldoon says he has seen the benefits of hospitalist involvement in post-acute care.

“In many markets, we seek out and often are able to become a practice site for a large hospitalist medical group,” he says. “That’s really good for us, the patients, and, we think, the hospitalists because it allows the hospitalists to be exposed to the practice and benefits of post-acute care without having to make a full commitment to be a skilled-nursing physician or a long-term acute-care physician.”

It also makes transitions of care smoother and less disruptive, he says, “because a patient is simply transferred from one hospitalist in a group to another or often maintaining that same hospitalist in the post-acute-care setting.”

Dr. Muldoon says the new track is of value to any hospitalist, whether they actually work in post-acute care or not.

“A hospitalist would be hard-pressed to provide knowledgeable input into where a patient should receive post-acute care without a working knowledge of which patients should be directed to which post-acute-care setting,” he says.

Doctor-Patient Relationship

This topic was a pre-course last year, and organizers decided to make this a full track on the final day of the meeting schedule.

“It’s really about communication style,” Dr. Mattison says. “There’s one session called ‘The Language of Empathy and Engagement: Communication Essentials for Patient-Centered Care.’ There’s one on unconscious biases and our underlying assumptions and how it affects how we care for patients. [Another is focused] on improving the patient experience in the hospital.”

Co-Management/ Perioperative Medicine

“There are a lot of challenges around anticoagulation management, optimizing patients’ physical heath prior to the surgery, what things should we be doing, what medications should we be giving, what ones shouldn’t we be giving,” Dr. Mattison says. “It’s an evolving field that has, every year, new information.”

Hidden Gems

Dr. Mattison draws special attention to “Work-Life Balance: Is It Possible?” (Tuesday, March 8, 4:20–5:40 p.m.). This year, this problem—all too familiar to hospitalists—will be addressed in a panel discussion, which is a change from previous years.

“There’s been, year after year after year, a lot of discussion around, how can I make my job manageable if my boss isn’t listening to me or is not attuned to work-life balance? How can I navigate this process?” she says. “I’m hopeful that the panel discussion will provide people with some real examples and strategies for success.”

She also draws attention to the session “Perioperative Pitfalls: Overcoming Common Challenges in Managing Medical Problems in Surgical Patients” (Monday, March 7, 3:05–4:20 p.m.).

“There are some true leaders in perioperative management, and they’re going to come together and have a panel discussion,” she says. “It’ll be an opportunity to see some of the great minds think, if you will.” TH

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

FDA approves maintenance therapy for CLL

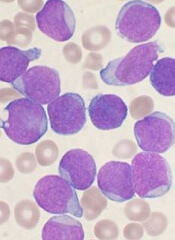

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of ofatumumab (Arzerra) as maintenance therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be given for an extended period to patients who are in complete or partial response after receiving at least 2 lines of therapy for recurrent or progressive CLL.

Ofatumumab is also FDA-approved as a single agent to treat CLL that is refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

And the drug is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

The FDA granted the new approval for ofatumumab based on an interim analysis of the PROLONG study. The results suggested that ofatumumab maintenance can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in CLL patients when compared to observation.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis. For more details on ofatumumab, see the full prescribing information.

PROLONG trial

The PROLONG trial was designed to compare ofatumumab maintenance to no further treatment in patients with a complete or partial response after second- or third-line treatment for CLL. Interim results of the study were presented at ASH 2014.

These results—in 474 patients—suggested that ofatumumab can significantly improve PFS. The median PFS was about 29 months in patients who received ofatumumab and about 15 months for patients who did not receive maintenance therapy (P<0.0001).

There was no significant difference in the median overall survival, which was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers said there were no unexpected safety findings. The most common adverse events (≥10%) were infusion reactions, neutropenia, and upper respiratory tract infection. ![]()

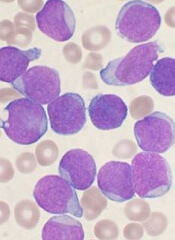

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of ofatumumab (Arzerra) as maintenance therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be given for an extended period to patients who are in complete or partial response after receiving at least 2 lines of therapy for recurrent or progressive CLL.

Ofatumumab is also FDA-approved as a single agent to treat CLL that is refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

And the drug is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

The FDA granted the new approval for ofatumumab based on an interim analysis of the PROLONG study. The results suggested that ofatumumab maintenance can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in CLL patients when compared to observation.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis. For more details on ofatumumab, see the full prescribing information.

PROLONG trial

The PROLONG trial was designed to compare ofatumumab maintenance to no further treatment in patients with a complete or partial response after second- or third-line treatment for CLL. Interim results of the study were presented at ASH 2014.

These results—in 474 patients—suggested that ofatumumab can significantly improve PFS. The median PFS was about 29 months in patients who received ofatumumab and about 15 months for patients who did not receive maintenance therapy (P<0.0001).

There was no significant difference in the median overall survival, which was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers said there were no unexpected safety findings. The most common adverse events (≥10%) were infusion reactions, neutropenia, and upper respiratory tract infection. ![]()

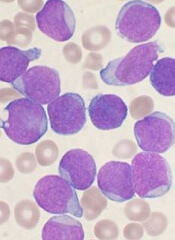

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of ofatumumab (Arzerra) as maintenance therapy for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug can now be given for an extended period to patients who are in complete or partial response after receiving at least 2 lines of therapy for recurrent or progressive CLL.

Ofatumumab is also FDA-approved as a single agent to treat CLL that is refractory to fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

And the drug is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

The FDA granted the new approval for ofatumumab based on an interim analysis of the PROLONG study. The results suggested that ofatumumab maintenance can improve progression-free survival (PFS) in CLL patients when compared to observation.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis. For more details on ofatumumab, see the full prescribing information.

PROLONG trial

The PROLONG trial was designed to compare ofatumumab maintenance to no further treatment in patients with a complete or partial response after second- or third-line treatment for CLL. Interim results of the study were presented at ASH 2014.

These results—in 474 patients—suggested that ofatumumab can significantly improve PFS. The median PFS was about 29 months in patients who received ofatumumab and about 15 months for patients who did not receive maintenance therapy (P<0.0001).

There was no significant difference in the median overall survival, which was not reached in either treatment arm.

The researchers said there were no unexpected safety findings. The most common adverse events (≥10%) were infusion reactions, neutropenia, and upper respiratory tract infection. ![]()

FDA approves generic drug for hemophilia

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a generic version of tranexamic acid for short-term control of bleeding in patients with hemophilia.

The drug, tranexamic acid injection (100 mg/mL) 1000 mg/10 mL single-dose vial, is a product of Aurobindo Pharma Limited.

The drug has been deemed bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Cyklokapron® injection, 100 mg/mL, a product of Pharmacia and Upjohn Company.

Aurobindo Pharma Limited said the generic drug should be launched in the US by the end of March. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a generic version of tranexamic acid for short-term control of bleeding in patients with hemophilia.

The drug, tranexamic acid injection (100 mg/mL) 1000 mg/10 mL single-dose vial, is a product of Aurobindo Pharma Limited.

The drug has been deemed bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Cyklokapron® injection, 100 mg/mL, a product of Pharmacia and Upjohn Company.

Aurobindo Pharma Limited said the generic drug should be launched in the US by the end of March. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a generic version of tranexamic acid for short-term control of bleeding in patients with hemophilia.

The drug, tranexamic acid injection (100 mg/mL) 1000 mg/10 mL single-dose vial, is a product of Aurobindo Pharma Limited.

The drug has been deemed bioequivalent and therapeutically equivalent to Cyklokapron® injection, 100 mg/mL, a product of Pharmacia and Upjohn Company.

Aurobindo Pharma Limited said the generic drug should be launched in the US by the end of March. ![]()

Research helps explain how RBCs move

Scientists say they have determined how red blood cells (RBCs) move, showing that RBCs can be moved by external forces and actively “wriggle” on their own.

Linking physical principles and biological reality, the team found that fast molecules in the vicinity of RBCs make the cell membranes wriggle, but the cells themselves also become active when they have enough reaction time.

The group recounted these findings in Nature Physics.

Previously, scientists had only shown that RBCs’ constant wriggling was caused by external forces. But biological considerations suggested that internal forces might also be responsible for the RBCs’ membranes changing shape.

“So we started with the following question, ‘As blood cells are living cells, why shouldn’t internal forces inside the cell also have an impact on the membrane?’” said study author Timo Betz, PhD, of Münster University in Münster, Germany.

“For biologists, this is all clear, but these forces were just never a part of any physical equation.”

Dr Betz and his colleagues wanted to find out more about the mechanics of blood cells and gain a detailed understanding of the forces that move and shape cells.

The team said it is important to learn about RBCs’ properties and their internal forces because they are unusually soft and elastic and must change their shape to pass through blood vessels. It is precisely because RBCs are normally so soft that, in previous studies, physicists measured large thermal fluctuations at the outer membrane of the cells.

These natural movements of molecules are defined by the ambient temperature. In other words, the cell membrane moves because molecules in the vicinity jog it. Under the microscope, this makes the RBCs appear to be wriggling.

Although this explains why RBCs move, it does not address the question of possible internal forces being a contributing factor.

So Dr Betz and his colleagues used optical tweezers to take a close look at the fluctuations of RBCs. The team stretched RBCs in a petri dish and analyzed the behavior of the cells.

The result was that, if the RBCs had enough reaction time, they became active themselves and were able to counteract the force of the optical tweezers. If they did not have this time, they were at the mercy of their environment, and only temperature-related forces were measured.

“By comparing both sets of measurements, we can exactly define how fast the cells become active themselves and what force they generate in order to change shape,” Dr Betz explained.

He and his colleagues have a theory as to which forces inside RBCs cause the cell membrane to change shape.

“Transport proteins could generate such forces in the membrane by moving ions from one side of the membrane to the other,” said study author Gerhard Gompper, PhD, of the Jülich Institute of Complex Systems in Jülich, Germany.

“Now, it’s up to the biologists, because we physicists only have a rough idea about which proteins might be the drivers for this movement,” Dr Betz added. “On the other hand, we can predict exactly how fast and how strong they are.” ![]()

Scientists say they have determined how red blood cells (RBCs) move, showing that RBCs can be moved by external forces and actively “wriggle” on their own.

Linking physical principles and biological reality, the team found that fast molecules in the vicinity of RBCs make the cell membranes wriggle, but the cells themselves also become active when they have enough reaction time.

The group recounted these findings in Nature Physics.

Previously, scientists had only shown that RBCs’ constant wriggling was caused by external forces. But biological considerations suggested that internal forces might also be responsible for the RBCs’ membranes changing shape.

“So we started with the following question, ‘As blood cells are living cells, why shouldn’t internal forces inside the cell also have an impact on the membrane?’” said study author Timo Betz, PhD, of Münster University in Münster, Germany.

“For biologists, this is all clear, but these forces were just never a part of any physical equation.”

Dr Betz and his colleagues wanted to find out more about the mechanics of blood cells and gain a detailed understanding of the forces that move and shape cells.

The team said it is important to learn about RBCs’ properties and their internal forces because they are unusually soft and elastic and must change their shape to pass through blood vessels. It is precisely because RBCs are normally so soft that, in previous studies, physicists measured large thermal fluctuations at the outer membrane of the cells.

These natural movements of molecules are defined by the ambient temperature. In other words, the cell membrane moves because molecules in the vicinity jog it. Under the microscope, this makes the RBCs appear to be wriggling.

Although this explains why RBCs move, it does not address the question of possible internal forces being a contributing factor.

So Dr Betz and his colleagues used optical tweezers to take a close look at the fluctuations of RBCs. The team stretched RBCs in a petri dish and analyzed the behavior of the cells.

The result was that, if the RBCs had enough reaction time, they became active themselves and were able to counteract the force of the optical tweezers. If they did not have this time, they were at the mercy of their environment, and only temperature-related forces were measured.

“By comparing both sets of measurements, we can exactly define how fast the cells become active themselves and what force they generate in order to change shape,” Dr Betz explained.

He and his colleagues have a theory as to which forces inside RBCs cause the cell membrane to change shape.

“Transport proteins could generate such forces in the membrane by moving ions from one side of the membrane to the other,” said study author Gerhard Gompper, PhD, of the Jülich Institute of Complex Systems in Jülich, Germany.

“Now, it’s up to the biologists, because we physicists only have a rough idea about which proteins might be the drivers for this movement,” Dr Betz added. “On the other hand, we can predict exactly how fast and how strong they are.” ![]()

Scientists say they have determined how red blood cells (RBCs) move, showing that RBCs can be moved by external forces and actively “wriggle” on their own.

Linking physical principles and biological reality, the team found that fast molecules in the vicinity of RBCs make the cell membranes wriggle, but the cells themselves also become active when they have enough reaction time.

The group recounted these findings in Nature Physics.

Previously, scientists had only shown that RBCs’ constant wriggling was caused by external forces. But biological considerations suggested that internal forces might also be responsible for the RBCs’ membranes changing shape.

“So we started with the following question, ‘As blood cells are living cells, why shouldn’t internal forces inside the cell also have an impact on the membrane?’” said study author Timo Betz, PhD, of Münster University in Münster, Germany.

“For biologists, this is all clear, but these forces were just never a part of any physical equation.”

Dr Betz and his colleagues wanted to find out more about the mechanics of blood cells and gain a detailed understanding of the forces that move and shape cells.

The team said it is important to learn about RBCs’ properties and their internal forces because they are unusually soft and elastic and must change their shape to pass through blood vessels. It is precisely because RBCs are normally so soft that, in previous studies, physicists measured large thermal fluctuations at the outer membrane of the cells.

These natural movements of molecules are defined by the ambient temperature. In other words, the cell membrane moves because molecules in the vicinity jog it. Under the microscope, this makes the RBCs appear to be wriggling.

Although this explains why RBCs move, it does not address the question of possible internal forces being a contributing factor.

So Dr Betz and his colleagues used optical tweezers to take a close look at the fluctuations of RBCs. The team stretched RBCs in a petri dish and analyzed the behavior of the cells.

The result was that, if the RBCs had enough reaction time, they became active themselves and were able to counteract the force of the optical tweezers. If they did not have this time, they were at the mercy of their environment, and only temperature-related forces were measured.

“By comparing both sets of measurements, we can exactly define how fast the cells become active themselves and what force they generate in order to change shape,” Dr Betz explained.

He and his colleagues have a theory as to which forces inside RBCs cause the cell membrane to change shape.

“Transport proteins could generate such forces in the membrane by moving ions from one side of the membrane to the other,” said study author Gerhard Gompper, PhD, of the Jülich Institute of Complex Systems in Jülich, Germany.

“Now, it’s up to the biologists, because we physicists only have a rough idea about which proteins might be the drivers for this movement,” Dr Betz added. “On the other hand, we can predict exactly how fast and how strong they are.” ![]()

Drug approved to treat ALL in EU

The European Commission has granted marketing authorization for pegaspargase (Oncaspar) to be used as part of combination antineoplastic therapy for pediatric and adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The approval means the drug can be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

Pegaspargase was already approved for use in Argentina, Belarus, Germany, Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and the US.

“Oncaspar has been used as an integral component of the treatment regimen for pediatric and adult patients with ALL for many years, in Europe and worldwide,” said Martin Schrappe, of Schleswig-Holstein University Hospital in Kiel, Germany.

“Today’s marketing authorization will ensure that more patients across the EU will benefit from access to Oncaspar as part of a standard of care regimen.”

The drug is being developed by Baxalta Incorporated.

First-line ALL

Researchers have evaluated the safety and effectiveness of pegaspargase in a study of 118 pediatric patients (ages 1 to 9) with newly diagnosed ALL. The patients were randomized 1:1 to pegaspargase or native E coli L-asparaginase, both as part of combination therapy.

Asparagine depletion (magnitude and duration) was similar between the 2 treatment arms. Event-free survival rates were also similar (about 80% in both arms), but the study was not designed to evaluate differences in event-free survival.

Grade 3/4 adverse events occurring in the pegaspargase and native E coli L-asparaginase arms, respectively, were abnormal liver tests (5% and 8%), elevated transaminases (3% and 7%), hyperbilirubinemia (2% and 2%), hyperglycemia (5% and 3%), central nervous system thrombosis (3% and 3%), coagulopathy (2% and 5%), pancreatitis (2% and 2%), and clinical allergic reactions to asparaginase (2% and 0%).

Previously treated ALL

Researchers have evaluated the effectiveness of pegaspargase in 4 open-label studies of patients with a history of prior clinical allergic reaction to asparaginase. The studies enrolled a total of 42 patients with multiply relapsed acute leukemia (39 with ALL).

Patients received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of multi-agent chemotherapy. The re-induction response rate was 50%—36% complete responses and 14% partial responses. Three responses occurred in patients who received single-agent pegaspargase.

Adverse event information on pegaspargase in relapsed ALL has been compiled from 5 clinical trials. The studies enrolled a total of 174 patients with relapsed ALL who received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of combination therapy.

Sixty-two of the patients had prior hypersensitivity reactions to asparaginase, and 112 did not. Allergic reactions to pegaspargase occurred in 32% of previously hypersensitive patients and 10% of non-hypersensitive patients.

The most common adverse events observed in patients who received pegaspargase were clinical allergic reactions, elevated transaminases, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathies.

The most common serious adverse events due to pegaspargase were thrombosis (4%), hyperglycemia requiring insulin therapy (3%), and pancreatitis (1%).

For more details on these trials and pegaspargase in general, see the product information. ![]()

The European Commission has granted marketing authorization for pegaspargase (Oncaspar) to be used as part of combination antineoplastic therapy for pediatric and adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The approval means the drug can be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

Pegaspargase was already approved for use in Argentina, Belarus, Germany, Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and the US.

“Oncaspar has been used as an integral component of the treatment regimen for pediatric and adult patients with ALL for many years, in Europe and worldwide,” said Martin Schrappe, of Schleswig-Holstein University Hospital in Kiel, Germany.

“Today’s marketing authorization will ensure that more patients across the EU will benefit from access to Oncaspar as part of a standard of care regimen.”

The drug is being developed by Baxalta Incorporated.

First-line ALL

Researchers have evaluated the safety and effectiveness of pegaspargase in a study of 118 pediatric patients (ages 1 to 9) with newly diagnosed ALL. The patients were randomized 1:1 to pegaspargase or native E coli L-asparaginase, both as part of combination therapy.

Asparagine depletion (magnitude and duration) was similar between the 2 treatment arms. Event-free survival rates were also similar (about 80% in both arms), but the study was not designed to evaluate differences in event-free survival.

Grade 3/4 adverse events occurring in the pegaspargase and native E coli L-asparaginase arms, respectively, were abnormal liver tests (5% and 8%), elevated transaminases (3% and 7%), hyperbilirubinemia (2% and 2%), hyperglycemia (5% and 3%), central nervous system thrombosis (3% and 3%), coagulopathy (2% and 5%), pancreatitis (2% and 2%), and clinical allergic reactions to asparaginase (2% and 0%).

Previously treated ALL

Researchers have evaluated the effectiveness of pegaspargase in 4 open-label studies of patients with a history of prior clinical allergic reaction to asparaginase. The studies enrolled a total of 42 patients with multiply relapsed acute leukemia (39 with ALL).

Patients received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of multi-agent chemotherapy. The re-induction response rate was 50%—36% complete responses and 14% partial responses. Three responses occurred in patients who received single-agent pegaspargase.

Adverse event information on pegaspargase in relapsed ALL has been compiled from 5 clinical trials. The studies enrolled a total of 174 patients with relapsed ALL who received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of combination therapy.

Sixty-two of the patients had prior hypersensitivity reactions to asparaginase, and 112 did not. Allergic reactions to pegaspargase occurred in 32% of previously hypersensitive patients and 10% of non-hypersensitive patients.

The most common adverse events observed in patients who received pegaspargase were clinical allergic reactions, elevated transaminases, hyperbilirubinemia, and coagulopathies.

The most common serious adverse events due to pegaspargase were thrombosis (4%), hyperglycemia requiring insulin therapy (3%), and pancreatitis (1%).

For more details on these trials and pegaspargase in general, see the product information. ![]()

The European Commission has granted marketing authorization for pegaspargase (Oncaspar) to be used as part of combination antineoplastic therapy for pediatric and adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

The approval means the drug can be marketed for this indication in the 28 member countries of the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.

Pegaspargase was already approved for use in Argentina, Belarus, Germany, Kazakhstan, Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and the US.

“Oncaspar has been used as an integral component of the treatment regimen for pediatric and adult patients with ALL for many years, in Europe and worldwide,” said Martin Schrappe, of Schleswig-Holstein University Hospital in Kiel, Germany.

“Today’s marketing authorization will ensure that more patients across the EU will benefit from access to Oncaspar as part of a standard of care regimen.”

The drug is being developed by Baxalta Incorporated.

First-line ALL

Researchers have evaluated the safety and effectiveness of pegaspargase in a study of 118 pediatric patients (ages 1 to 9) with newly diagnosed ALL. The patients were randomized 1:1 to pegaspargase or native E coli L-asparaginase, both as part of combination therapy.

Asparagine depletion (magnitude and duration) was similar between the 2 treatment arms. Event-free survival rates were also similar (about 80% in both arms), but the study was not designed to evaluate differences in event-free survival.

Grade 3/4 adverse events occurring in the pegaspargase and native E coli L-asparaginase arms, respectively, were abnormal liver tests (5% and 8%), elevated transaminases (3% and 7%), hyperbilirubinemia (2% and 2%), hyperglycemia (5% and 3%), central nervous system thrombosis (3% and 3%), coagulopathy (2% and 5%), pancreatitis (2% and 2%), and clinical allergic reactions to asparaginase (2% and 0%).

Previously treated ALL

Researchers have evaluated the effectiveness of pegaspargase in 4 open-label studies of patients with a history of prior clinical allergic reaction to asparaginase. The studies enrolled a total of 42 patients with multiply relapsed acute leukemia (39 with ALL).

Patients received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of multi-agent chemotherapy. The re-induction response rate was 50%—36% complete responses and 14% partial responses. Three responses occurred in patients who received single-agent pegaspargase.

Adverse event information on pegaspargase in relapsed ALL has been compiled from 5 clinical trials. The studies enrolled a total of 174 patients with relapsed ALL who received pegaspargase as a single agent or as part of combination therapy.