User login

Low transformation rate in nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

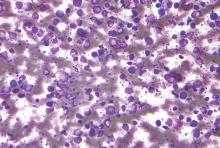

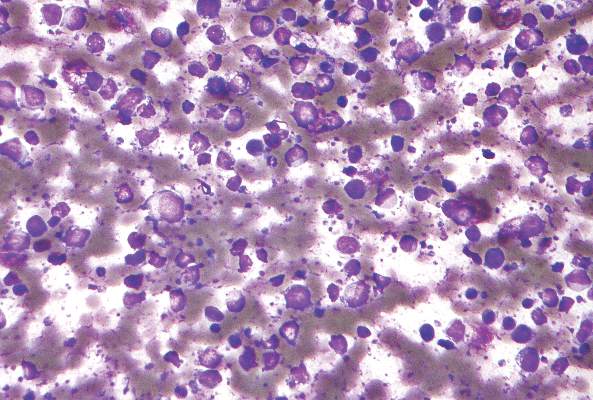

Fewer than 8% of cases of nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) transformed to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), based on a large prospective single-center study with long-term follow-up.

This rate was lower than the risk of transformation reported for transformed follicular lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, according to Dr. Saad Kenderian and his associates at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Transformation was significantly associated with splenic involvement at presentation and with prior chemotherapy exposure, but did not worsen overall survival, they added.

“To our knowledge, this cohort represents the largest analysis to date of consecutive patients with NLPHL,” they said.

The study comprised 222 patients with newly diagnosed NLPHL who were treated at Mayo Clinic between 1970 and 2011. Median age at diagnosis was 40 years, and two-thirds of patients were men. The median follow-up period was 16 years (Blood 2016;12:1960-6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665505).

During follow up, 17 cases (7.6%) transformed to DLBCL, for a transformation rate of 0.74 cases for every 100 patient-years, the investigators said. Median time to transformation was 35 months (range, 6-268 months). Predictors of transformation included any prior chemotherapy exposure (P = .04) and splenic involvement (P = .03). The rates of 40-year freedom from transformation were 87% when there was no splenic involvement and 21% when the spleen was involved, and were 87% if radiation therapy was used as a single modality compared with 77% in patients treated with prior chemotherapy or chemoradiation.

Five-year overall survival was 76% in patients with transformed disease, which was similar to overall survival among patients whose disease did not transform to DLBCL, the researchers noted.

Other studies of NLPHL have reported anywhere from a 2% to a 17% transformation rate, but those studies had smaller sample sizes, shorter follow-up periods, and less rigorous enrollment criteria and methods to confirm transformation, the investigators noted. “The finding of splenic involvement as a risk factor for transformation was reported by previous investigators. Interestingly, the association between exposure to prior chemotherapy and reduced freedom from transformation has not been reported in the past, but it has been observed in other low-grade lymphoma studies,” they added. “In contrast to follicular lymphoma, transformed NLPHL is not associated with an adverse impact on OS, suggesting a possibly different biology of transformation.”

The research was partially supported by Lymphoma SPORE and the Predolin Foundation. The investigators had no disclosures.

Kenderian et al. report a lower rate of transformation (7.6%) to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for patients with nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma compared with other series and found that transformation did not have a negative impact on overall survival. Reassuringly, even if transformation occurs, it is generally at a low rate. Also, these patients do well with additional treatment and do not have worse overall survival. At the MD Anderson Cancer Center, we have used a regimen based on R-CHOP and have not seen transformations. But only through large cooperative clinical trials can we determine whether R-CHOP or other more novel regimens are actually superior to ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) or rituximab (R)-ABVD for patients at high risk of transformation.

Dr. Michelle Fanale is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. She had no disclosures. These comments are from her editorial (Blood 2016;1927:1946-7 doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-699108).

Kenderian et al. report a lower rate of transformation (7.6%) to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for patients with nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma compared with other series and found that transformation did not have a negative impact on overall survival. Reassuringly, even if transformation occurs, it is generally at a low rate. Also, these patients do well with additional treatment and do not have worse overall survival. At the MD Anderson Cancer Center, we have used a regimen based on R-CHOP and have not seen transformations. But only through large cooperative clinical trials can we determine whether R-CHOP or other more novel regimens are actually superior to ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) or rituximab (R)-ABVD for patients at high risk of transformation.

Dr. Michelle Fanale is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. She had no disclosures. These comments are from her editorial (Blood 2016;1927:1946-7 doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-699108).

Kenderian et al. report a lower rate of transformation (7.6%) to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma for patients with nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma compared with other series and found that transformation did not have a negative impact on overall survival. Reassuringly, even if transformation occurs, it is generally at a low rate. Also, these patients do well with additional treatment and do not have worse overall survival. At the MD Anderson Cancer Center, we have used a regimen based on R-CHOP and have not seen transformations. But only through large cooperative clinical trials can we determine whether R-CHOP or other more novel regimens are actually superior to ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) or rituximab (R)-ABVD for patients at high risk of transformation.

Dr. Michelle Fanale is at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. She had no disclosures. These comments are from her editorial (Blood 2016;1927:1946-7 doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-699108).

Fewer than 8% of cases of nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) transformed to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), based on a large prospective single-center study with long-term follow-up.

This rate was lower than the risk of transformation reported for transformed follicular lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, according to Dr. Saad Kenderian and his associates at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Transformation was significantly associated with splenic involvement at presentation and with prior chemotherapy exposure, but did not worsen overall survival, they added.

“To our knowledge, this cohort represents the largest analysis to date of consecutive patients with NLPHL,” they said.

The study comprised 222 patients with newly diagnosed NLPHL who were treated at Mayo Clinic between 1970 and 2011. Median age at diagnosis was 40 years, and two-thirds of patients were men. The median follow-up period was 16 years (Blood 2016;12:1960-6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665505).

During follow up, 17 cases (7.6%) transformed to DLBCL, for a transformation rate of 0.74 cases for every 100 patient-years, the investigators said. Median time to transformation was 35 months (range, 6-268 months). Predictors of transformation included any prior chemotherapy exposure (P = .04) and splenic involvement (P = .03). The rates of 40-year freedom from transformation were 87% when there was no splenic involvement and 21% when the spleen was involved, and were 87% if radiation therapy was used as a single modality compared with 77% in patients treated with prior chemotherapy or chemoradiation.

Five-year overall survival was 76% in patients with transformed disease, which was similar to overall survival among patients whose disease did not transform to DLBCL, the researchers noted.

Other studies of NLPHL have reported anywhere from a 2% to a 17% transformation rate, but those studies had smaller sample sizes, shorter follow-up periods, and less rigorous enrollment criteria and methods to confirm transformation, the investigators noted. “The finding of splenic involvement as a risk factor for transformation was reported by previous investigators. Interestingly, the association between exposure to prior chemotherapy and reduced freedom from transformation has not been reported in the past, but it has been observed in other low-grade lymphoma studies,” they added. “In contrast to follicular lymphoma, transformed NLPHL is not associated with an adverse impact on OS, suggesting a possibly different biology of transformation.”

The research was partially supported by Lymphoma SPORE and the Predolin Foundation. The investigators had no disclosures.

Fewer than 8% of cases of nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) transformed to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), based on a large prospective single-center study with long-term follow-up.

This rate was lower than the risk of transformation reported for transformed follicular lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia, according to Dr. Saad Kenderian and his associates at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Transformation was significantly associated with splenic involvement at presentation and with prior chemotherapy exposure, but did not worsen overall survival, they added.

“To our knowledge, this cohort represents the largest analysis to date of consecutive patients with NLPHL,” they said.

The study comprised 222 patients with newly diagnosed NLPHL who were treated at Mayo Clinic between 1970 and 2011. Median age at diagnosis was 40 years, and two-thirds of patients were men. The median follow-up period was 16 years (Blood 2016;12:1960-6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665505).

During follow up, 17 cases (7.6%) transformed to DLBCL, for a transformation rate of 0.74 cases for every 100 patient-years, the investigators said. Median time to transformation was 35 months (range, 6-268 months). Predictors of transformation included any prior chemotherapy exposure (P = .04) and splenic involvement (P = .03). The rates of 40-year freedom from transformation were 87% when there was no splenic involvement and 21% when the spleen was involved, and were 87% if radiation therapy was used as a single modality compared with 77% in patients treated with prior chemotherapy or chemoradiation.

Five-year overall survival was 76% in patients with transformed disease, which was similar to overall survival among patients whose disease did not transform to DLBCL, the researchers noted.

Other studies of NLPHL have reported anywhere from a 2% to a 17% transformation rate, but those studies had smaller sample sizes, shorter follow-up periods, and less rigorous enrollment criteria and methods to confirm transformation, the investigators noted. “The finding of splenic involvement as a risk factor for transformation was reported by previous investigators. Interestingly, the association between exposure to prior chemotherapy and reduced freedom from transformation has not been reported in the past, but it has been observed in other low-grade lymphoma studies,” they added. “In contrast to follicular lymphoma, transformed NLPHL is not associated with an adverse impact on OS, suggesting a possibly different biology of transformation.”

The research was partially supported by Lymphoma SPORE and the Predolin Foundation. The investigators had no disclosures.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: The risk of transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is low in patients with nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma.

Major finding: Only 7.6% of cases transformed over a median of 16 years of follow-up, and transformation did not worsen overall survival.

Data source: A prospective single-center study of 222 consecutive adults with NLPHL.

Disclosures: The research was partially supported by Lymphoma SPORE and the Predolin Foundation. The investigators had no disclosures.

DAAs, HCV-positive livers could reduce transplant waiting list

BARCELONA – Using direct-acting antiviral therapy and livers from HCV-positive donors are separate approaches that could help reduce waiting lists and ensure that patients with HCV in most need get a liver transplant, according to data from two studies presented at the International Liver Congress.

In a retrospective European cohort study, 33% of HCV-positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis who were awaiting a transplant were no longer considered to be in urgent need and almost 20% could be removed from the list altogether 60 weeks after starting treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs).

Dr. Luca Belli of Niguarda Hospital, Milan, who presented the findings at the meeting, cautioned that while the results were encouraging, it is not clear how long the clinical improvement will last. “It will be critical to assess the long-term risks of death, further redeterioration, and developments of hepatocellular carcinoma more specifically, as all these factors still need to be verified,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

Meanwhile, data from a large analysis of all solid transplant recipients in the United States showed that using livers from HCV-positive donors in HCV-positive recipients was associated with long-term patient outcomes similar to outcomes of using livers from non–HCV-negative donors in HCV-positive recipients, with no difference in mortality or graft survival.

“Over the past 2 decades, the use of HCV-positive organs for liver transplantation has tripled in the United States,” said Maria Stepanova, Ph.D., a senior biostatistician for Inova Health System in Falls Church, Va., who presented her findings at the meeting.

“Despite this, the medium- to long-term outcomes of HCV-positive liver transplant recipients transplanted from HCV-positive donors were not affected by HCV-positivity of a donor,” added Dr. Stepanova, who also works at the Center for Outcomes Research in Liver Disease in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Zobair Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, and coauthor of the study, said during a press briefing that this does not mean that livers from HCV-positive donor could be used in HCV-negative recipients. The reason for that is that it would be causing an acute infection regardless of whether or not antiviral treatment is available and “at this point the evidence is not there,” he said.

Dr. Laurent Castera of Hôpital Beaujon in Paris, and Dr. Tom Hemming Karlsen of Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet in Norway commented on the significance of these data in press releases issued by the EASL. Both experts, who were not involved in the studies, noted the findings could help take the strain off the liver transplant list in the future.

“Treating patients with direct-acting antiviral therapy could result in those with a more pressing need for a liver transplant receiving the donation they need, potentially reducing the number of deaths that occur on the waiting list,” Dr. Castera said.

“With the number of people waiting for a liver transplant expected to rise, the study results should give hope over the coming years for those on the waiting list,” Dr. Karlsen said. Referring to the U.S. study, he said the results “clearly demonstrate a greater opportunity for use of HCV-positive livers over the coming years due to their comparable outcomes with healthy livers.”

The European study presented by Dr. Belli involved 134 patients with HCV and decompensated cirrhosis but without hepatocellular carcinoma listed for liver transplant between February 2014 and February 2015 at 11 centers in Austria, Italy, and France. Of these patients, 103 had been treated with DAAs while on the transplant list; approximately half had been treated with a single DAA (sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 24-48 weeks) and half with two DAAs (sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or ledipasvir for 12-24 weeks).

The primary endpoint was the probability of being “inactivated” and then “delisted.” Inactivated meant that there was clinical improvement resulting in patients being put “on hold,” and “delisted” was defined as patients being taken off the transplant list after a variable period of inactivation.

The median age of patients in the study was 54 years and 68% were male. Just under 50% of patients had a low (less than 16) MELD score, around 37% had a MELD score of 16-20, and 13% had a MELD score of more than 20. Around 45% had Child-Pugh B and 55% had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. Two-thirds had medically controlled and 26% had medically uncontrolled ascites, and 46% had medically controlled and 1% had medically uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy.

Good virologic efficacy was seen with both single- and dual-agent DAA therapy, with rapid virologic responses of 61% and 67% and early virologic responses of 98% and 98%. Of the 52 patients given single-agent DAA treatment, 22 had a transplant and one patient had a posttransplant relapse. Of the remaining 30 patients on the transplant list, four relapsed. Nineteen of 51 patients given dual-DAA therapy were transplanted and there was one relapse, with no relapses in the 32 patients who remained on the transplant list.

After about 60 weeks of follow-up, one in three patients were “inactivated” and not considered in urgent need of a transplant, but inactivation occurred as early as 12 weeks after DAA therapy, Dr. Belli observed.

Inactivation was associated with a 3.3 decrease in MELD score, a 2-point reduction in Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, and a 0.5-g/dL increase in serum albumin after 24 weeks. There was also regression or improvement in ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in most patients. The median time of delisting was 48 weeks.

These results suggest that there could be a wider role for DAA therapy even in the sickest of HCV-positive patients who are urgently awaiting a liver transplant. Another approach to increase the number of people receiving a transplant is to use HCV-positive livers. The practice has been increasing over the years, but it is not known if the approach is safe and if the risks outweigh the benefits.

To investigate, Dr. Stepanova and associates obtained data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) on all liver transplants performed in the United States between 1995 and 2003 involving HCV-positive patients. A total of 37,317 records were found, of which 33,668 had data on the donors’ HCV status and on the recipients’ mortality status. Of these, 1,930 (5.7%) had received a liver from an HCV-positive donor. Dr. Stepanova noted that there had been an increase in the percentage of patients who had received an HCV-positive liver, from less than 3% in 1995 to more than 9% in 2013.

Compared with HCV-negative donors, HCV-positive donors were older, were more likely to have a history of drug abuse, and more likely to be non–heart beating at the time of procurement.

The HCV-positive liver recipients also tended to be older, to be of African-American ethnicity, and to have liver cancer but lower MELD scores than those who received an HCV-negative liver. “So these are patients that cannot wait for a long time so maybe elect to use an HCV-positive donor,” Dr. Younossi said.

Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) showed no statistically significant difference in posttransplant survival or posttransplant graft loss between HCV-positive and HCV-negative livers; aHR were a respective 1.03 and 0.905, with tight 95% confidence intervals. However, a more recent year of transplant did appear to suggest a possible advantage of using an HCV-positive donor liver in an HCV-positive patient, with lower mortality (aHR = 0.978 per year, P less than .0001) and graft failure (aHR = 0.960 per year, P less than .0001) rates.

While the use of HCV-positive livers in HCV-positive recipients was felt to be “reasonably safe,” these findings “cannot be used in support of indiscriminate use of HCV-positive donors,” Dr. Stepanova observed. Further studies are needed to establish criteria on which to select donors that would provide patients with the best possible risk-to-benefit ratio, she said.

Further avenues for research would also be to see if HCV-positive livers could be given to HCV-negative patients and if genotype matters. It would also need to be seen if posttransplantation antiviral treatment would be necessary.

Dr. Belli has received research support from Gilead, AbbVie and BMS and acted as a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Stepanova did not have conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Younossi has acted as a consultant to BMS, AbbVie, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, and Intercept. Dr. Castera and Dr. Karlsen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

BARCELONA – Using direct-acting antiviral therapy and livers from HCV-positive donors are separate approaches that could help reduce waiting lists and ensure that patients with HCV in most need get a liver transplant, according to data from two studies presented at the International Liver Congress.

In a retrospective European cohort study, 33% of HCV-positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis who were awaiting a transplant were no longer considered to be in urgent need and almost 20% could be removed from the list altogether 60 weeks after starting treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs).

Dr. Luca Belli of Niguarda Hospital, Milan, who presented the findings at the meeting, cautioned that while the results were encouraging, it is not clear how long the clinical improvement will last. “It will be critical to assess the long-term risks of death, further redeterioration, and developments of hepatocellular carcinoma more specifically, as all these factors still need to be verified,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

Meanwhile, data from a large analysis of all solid transplant recipients in the United States showed that using livers from HCV-positive donors in HCV-positive recipients was associated with long-term patient outcomes similar to outcomes of using livers from non–HCV-negative donors in HCV-positive recipients, with no difference in mortality or graft survival.

“Over the past 2 decades, the use of HCV-positive organs for liver transplantation has tripled in the United States,” said Maria Stepanova, Ph.D., a senior biostatistician for Inova Health System in Falls Church, Va., who presented her findings at the meeting.

“Despite this, the medium- to long-term outcomes of HCV-positive liver transplant recipients transplanted from HCV-positive donors were not affected by HCV-positivity of a donor,” added Dr. Stepanova, who also works at the Center for Outcomes Research in Liver Disease in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Zobair Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, and coauthor of the study, said during a press briefing that this does not mean that livers from HCV-positive donor could be used in HCV-negative recipients. The reason for that is that it would be causing an acute infection regardless of whether or not antiviral treatment is available and “at this point the evidence is not there,” he said.

Dr. Laurent Castera of Hôpital Beaujon in Paris, and Dr. Tom Hemming Karlsen of Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet in Norway commented on the significance of these data in press releases issued by the EASL. Both experts, who were not involved in the studies, noted the findings could help take the strain off the liver transplant list in the future.

“Treating patients with direct-acting antiviral therapy could result in those with a more pressing need for a liver transplant receiving the donation they need, potentially reducing the number of deaths that occur on the waiting list,” Dr. Castera said.

“With the number of people waiting for a liver transplant expected to rise, the study results should give hope over the coming years for those on the waiting list,” Dr. Karlsen said. Referring to the U.S. study, he said the results “clearly demonstrate a greater opportunity for use of HCV-positive livers over the coming years due to their comparable outcomes with healthy livers.”

The European study presented by Dr. Belli involved 134 patients with HCV and decompensated cirrhosis but without hepatocellular carcinoma listed for liver transplant between February 2014 and February 2015 at 11 centers in Austria, Italy, and France. Of these patients, 103 had been treated with DAAs while on the transplant list; approximately half had been treated with a single DAA (sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 24-48 weeks) and half with two DAAs (sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or ledipasvir for 12-24 weeks).

The primary endpoint was the probability of being “inactivated” and then “delisted.” Inactivated meant that there was clinical improvement resulting in patients being put “on hold,” and “delisted” was defined as patients being taken off the transplant list after a variable period of inactivation.

The median age of patients in the study was 54 years and 68% were male. Just under 50% of patients had a low (less than 16) MELD score, around 37% had a MELD score of 16-20, and 13% had a MELD score of more than 20. Around 45% had Child-Pugh B and 55% had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. Two-thirds had medically controlled and 26% had medically uncontrolled ascites, and 46% had medically controlled and 1% had medically uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy.

Good virologic efficacy was seen with both single- and dual-agent DAA therapy, with rapid virologic responses of 61% and 67% and early virologic responses of 98% and 98%. Of the 52 patients given single-agent DAA treatment, 22 had a transplant and one patient had a posttransplant relapse. Of the remaining 30 patients on the transplant list, four relapsed. Nineteen of 51 patients given dual-DAA therapy were transplanted and there was one relapse, with no relapses in the 32 patients who remained on the transplant list.

After about 60 weeks of follow-up, one in three patients were “inactivated” and not considered in urgent need of a transplant, but inactivation occurred as early as 12 weeks after DAA therapy, Dr. Belli observed.

Inactivation was associated with a 3.3 decrease in MELD score, a 2-point reduction in Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, and a 0.5-g/dL increase in serum albumin after 24 weeks. There was also regression or improvement in ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in most patients. The median time of delisting was 48 weeks.

These results suggest that there could be a wider role for DAA therapy even in the sickest of HCV-positive patients who are urgently awaiting a liver transplant. Another approach to increase the number of people receiving a transplant is to use HCV-positive livers. The practice has been increasing over the years, but it is not known if the approach is safe and if the risks outweigh the benefits.

To investigate, Dr. Stepanova and associates obtained data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) on all liver transplants performed in the United States between 1995 and 2003 involving HCV-positive patients. A total of 37,317 records were found, of which 33,668 had data on the donors’ HCV status and on the recipients’ mortality status. Of these, 1,930 (5.7%) had received a liver from an HCV-positive donor. Dr. Stepanova noted that there had been an increase in the percentage of patients who had received an HCV-positive liver, from less than 3% in 1995 to more than 9% in 2013.

Compared with HCV-negative donors, HCV-positive donors were older, were more likely to have a history of drug abuse, and more likely to be non–heart beating at the time of procurement.

The HCV-positive liver recipients also tended to be older, to be of African-American ethnicity, and to have liver cancer but lower MELD scores than those who received an HCV-negative liver. “So these are patients that cannot wait for a long time so maybe elect to use an HCV-positive donor,” Dr. Younossi said.

Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) showed no statistically significant difference in posttransplant survival or posttransplant graft loss between HCV-positive and HCV-negative livers; aHR were a respective 1.03 and 0.905, with tight 95% confidence intervals. However, a more recent year of transplant did appear to suggest a possible advantage of using an HCV-positive donor liver in an HCV-positive patient, with lower mortality (aHR = 0.978 per year, P less than .0001) and graft failure (aHR = 0.960 per year, P less than .0001) rates.

While the use of HCV-positive livers in HCV-positive recipients was felt to be “reasonably safe,” these findings “cannot be used in support of indiscriminate use of HCV-positive donors,” Dr. Stepanova observed. Further studies are needed to establish criteria on which to select donors that would provide patients with the best possible risk-to-benefit ratio, she said.

Further avenues for research would also be to see if HCV-positive livers could be given to HCV-negative patients and if genotype matters. It would also need to be seen if posttransplantation antiviral treatment would be necessary.

Dr. Belli has received research support from Gilead, AbbVie and BMS and acted as a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Stepanova did not have conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Younossi has acted as a consultant to BMS, AbbVie, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, and Intercept. Dr. Castera and Dr. Karlsen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

BARCELONA – Using direct-acting antiviral therapy and livers from HCV-positive donors are separate approaches that could help reduce waiting lists and ensure that patients with HCV in most need get a liver transplant, according to data from two studies presented at the International Liver Congress.

In a retrospective European cohort study, 33% of HCV-positive patients with decompensated cirrhosis who were awaiting a transplant were no longer considered to be in urgent need and almost 20% could be removed from the list altogether 60 weeks after starting treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs).

Dr. Luca Belli of Niguarda Hospital, Milan, who presented the findings at the meeting, cautioned that while the results were encouraging, it is not clear how long the clinical improvement will last. “It will be critical to assess the long-term risks of death, further redeterioration, and developments of hepatocellular carcinoma more specifically, as all these factors still need to be verified,” he said at the meeting, sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL).

Meanwhile, data from a large analysis of all solid transplant recipients in the United States showed that using livers from HCV-positive donors in HCV-positive recipients was associated with long-term patient outcomes similar to outcomes of using livers from non–HCV-negative donors in HCV-positive recipients, with no difference in mortality or graft survival.

“Over the past 2 decades, the use of HCV-positive organs for liver transplantation has tripled in the United States,” said Maria Stepanova, Ph.D., a senior biostatistician for Inova Health System in Falls Church, Va., who presented her findings at the meeting.

“Despite this, the medium- to long-term outcomes of HCV-positive liver transplant recipients transplanted from HCV-positive donors were not affected by HCV-positivity of a donor,” added Dr. Stepanova, who also works at the Center for Outcomes Research in Liver Disease in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Zobair Younossi, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Hospital, and coauthor of the study, said during a press briefing that this does not mean that livers from HCV-positive donor could be used in HCV-negative recipients. The reason for that is that it would be causing an acute infection regardless of whether or not antiviral treatment is available and “at this point the evidence is not there,” he said.

Dr. Laurent Castera of Hôpital Beaujon in Paris, and Dr. Tom Hemming Karlsen of Oslo University Hospital Rikshospitalet in Norway commented on the significance of these data in press releases issued by the EASL. Both experts, who were not involved in the studies, noted the findings could help take the strain off the liver transplant list in the future.

“Treating patients with direct-acting antiviral therapy could result in those with a more pressing need for a liver transplant receiving the donation they need, potentially reducing the number of deaths that occur on the waiting list,” Dr. Castera said.

“With the number of people waiting for a liver transplant expected to rise, the study results should give hope over the coming years for those on the waiting list,” Dr. Karlsen said. Referring to the U.S. study, he said the results “clearly demonstrate a greater opportunity for use of HCV-positive livers over the coming years due to their comparable outcomes with healthy livers.”

The European study presented by Dr. Belli involved 134 patients with HCV and decompensated cirrhosis but without hepatocellular carcinoma listed for liver transplant between February 2014 and February 2015 at 11 centers in Austria, Italy, and France. Of these patients, 103 had been treated with DAAs while on the transplant list; approximately half had been treated with a single DAA (sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for 24-48 weeks) and half with two DAAs (sofosbuvir with either daclatasvir or ledipasvir for 12-24 weeks).

The primary endpoint was the probability of being “inactivated” and then “delisted.” Inactivated meant that there was clinical improvement resulting in patients being put “on hold,” and “delisted” was defined as patients being taken off the transplant list after a variable period of inactivation.

The median age of patients in the study was 54 years and 68% were male. Just under 50% of patients had a low (less than 16) MELD score, around 37% had a MELD score of 16-20, and 13% had a MELD score of more than 20. Around 45% had Child-Pugh B and 55% had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. Two-thirds had medically controlled and 26% had medically uncontrolled ascites, and 46% had medically controlled and 1% had medically uncontrolled hepatic encephalopathy.

Good virologic efficacy was seen with both single- and dual-agent DAA therapy, with rapid virologic responses of 61% and 67% and early virologic responses of 98% and 98%. Of the 52 patients given single-agent DAA treatment, 22 had a transplant and one patient had a posttransplant relapse. Of the remaining 30 patients on the transplant list, four relapsed. Nineteen of 51 patients given dual-DAA therapy were transplanted and there was one relapse, with no relapses in the 32 patients who remained on the transplant list.

After about 60 weeks of follow-up, one in three patients were “inactivated” and not considered in urgent need of a transplant, but inactivation occurred as early as 12 weeks after DAA therapy, Dr. Belli observed.

Inactivation was associated with a 3.3 decrease in MELD score, a 2-point reduction in Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, and a 0.5-g/dL increase in serum albumin after 24 weeks. There was also regression or improvement in ascites and hepatic encephalopathy in most patients. The median time of delisting was 48 weeks.

These results suggest that there could be a wider role for DAA therapy even in the sickest of HCV-positive patients who are urgently awaiting a liver transplant. Another approach to increase the number of people receiving a transplant is to use HCV-positive livers. The practice has been increasing over the years, but it is not known if the approach is safe and if the risks outweigh the benefits.

To investigate, Dr. Stepanova and associates obtained data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) on all liver transplants performed in the United States between 1995 and 2003 involving HCV-positive patients. A total of 37,317 records were found, of which 33,668 had data on the donors’ HCV status and on the recipients’ mortality status. Of these, 1,930 (5.7%) had received a liver from an HCV-positive donor. Dr. Stepanova noted that there had been an increase in the percentage of patients who had received an HCV-positive liver, from less than 3% in 1995 to more than 9% in 2013.

Compared with HCV-negative donors, HCV-positive donors were older, were more likely to have a history of drug abuse, and more likely to be non–heart beating at the time of procurement.

The HCV-positive liver recipients also tended to be older, to be of African-American ethnicity, and to have liver cancer but lower MELD scores than those who received an HCV-negative liver. “So these are patients that cannot wait for a long time so maybe elect to use an HCV-positive donor,” Dr. Younossi said.

Adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) showed no statistically significant difference in posttransplant survival or posttransplant graft loss between HCV-positive and HCV-negative livers; aHR were a respective 1.03 and 0.905, with tight 95% confidence intervals. However, a more recent year of transplant did appear to suggest a possible advantage of using an HCV-positive donor liver in an HCV-positive patient, with lower mortality (aHR = 0.978 per year, P less than .0001) and graft failure (aHR = 0.960 per year, P less than .0001) rates.

While the use of HCV-positive livers in HCV-positive recipients was felt to be “reasonably safe,” these findings “cannot be used in support of indiscriminate use of HCV-positive donors,” Dr. Stepanova observed. Further studies are needed to establish criteria on which to select donors that would provide patients with the best possible risk-to-benefit ratio, she said.

Further avenues for research would also be to see if HCV-positive livers could be given to HCV-negative patients and if genotype matters. It would also need to be seen if posttransplantation antiviral treatment would be necessary.

Dr. Belli has received research support from Gilead, AbbVie and BMS and acted as a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Stepanova did not have conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Younossi has acted as a consultant to BMS, AbbVie, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, and Intercept. Dr. Castera and Dr. Karlsen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

AT THE INTERNATIONAL LIVER CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Using direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy and HCV-positive livers could help reduce the strain on liver transplant lists.

Major finding: One in three HCV-positive patients treated with DAAs were considered nonurgent cases and one in five could be delisted. HCV-positive livers were associated with similar graft and host survival.

Data source: A retrospective European cohort study of 103 patients with decompensated cirrhosis who were treated with DAAs while awaiting liver transplant and an analysis of more than 33,000 HCV patients awaiting a liver transplant in the United States.

Disclosures: Dr. Belli has received research support from Gilead, AbbVie, and BMS and acted as a consultant to Gilead. Dr. Stepanova did not have conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Younossi has acted as a consultant to BMS, AbbVie, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, and Intercept. Dr. Castera and Dr. Karlsen had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Doppler ultrasound headset performs well at spotting sports-related concussion

VANCOUVER – A new transcranial Doppler platform that analyzes subtle changes in the cerebral blood flow waveform performed well in detecting sports-related concussion in a cohort study of 238 Los Angeles high school athletes.

The investigational headset device was able to differentiate between those with and without a recent concussion 83% of the time, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. In contrast, traditional transcranial Doppler analysis detected a recent concussion only 50%-60% of the time.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing evidence that cerebral hemodynamics are altered following sports-related concussion,” senior author Robert Hamilton, Ph.D., cofounder and chief science officer of Neural Analytics in Los Angeles, commented in a session and interview.

Most studies in this area have used MRI or traditional transcranial Doppler analysis, he said. However, the former is costly, time consuming, and not portable, and the latter has not proven very accurate.

As traditional Doppler analysis disregards the majority of waveform data, Dr. Hamilton and his colleagues developed an advanced platform that uses machine learning to analyze the entire shape of the cerebral blood flow velocity waveform through quantitative cerebral hemodynamics.

They compared the advanced analysis with traditional analysis among 69 high school athletes in contact sports who had sustained a concussion an average of 6 days earlier and a control group of 169 unaffected age-matched high school athletes from contact and noncontact sports.

Both groups had bilateral monitoring of blood flow in the middle cerebral artery with transcranial Doppler while they followed a standard cerebrovascular reactivity protocol that included rest and breath holding.

Results showed that for differentiating between athletes who did and did not have concussion, the advanced analysis had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 83%. (Sensitivity was 72%, specificity was 82%, and overall accuracy was 80%.)

In comparison, the area under the curve was substantially lower for the traditional analysis measures: It was 55% for mean velocity (100% sensitivity, 0% specificity, 76% accuracy), 52% for the pulsatility index (86% sensitivity, 23% specificity, 61% accuracy), and 60% for the cerebrovascular reactivity index (51% sensitivity, 68% specificity, 64% accuracy).

“Unfortunately, concussion diagnostics and management today are basically subjective,” Dr. Hamilton commented. The advanced analysis may therefore improve the situation by providing objective evidence of blood flow dysfunction after injury.

The new analysis platform “is easy to use and portable, and [testing] can be done very quickly, within 5 minutes,” he noted. “The nice thing is it can be done on the sideline, in the emergency room, or in a doctor’s office.”

The investigators will next use the advanced analysis to track recovery of blood flow regulation after sports-related concussion and will compare its performance with that of additional modalities, such as MRI, according to Dr. Hamilton. Furthermore, they are testing it in various other populations: adolescents, college athletes, and members of the military.

“Ultimately, blood flow dysfunction is also important in a wide variety of conditions, such as stroke and dementia,” he pointed out. “So those are conditions that we are looking at to study this year and moving forward in the future.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

VANCOUVER – A new transcranial Doppler platform that analyzes subtle changes in the cerebral blood flow waveform performed well in detecting sports-related concussion in a cohort study of 238 Los Angeles high school athletes.

The investigational headset device was able to differentiate between those with and without a recent concussion 83% of the time, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. In contrast, traditional transcranial Doppler analysis detected a recent concussion only 50%-60% of the time.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing evidence that cerebral hemodynamics are altered following sports-related concussion,” senior author Robert Hamilton, Ph.D., cofounder and chief science officer of Neural Analytics in Los Angeles, commented in a session and interview.

Most studies in this area have used MRI or traditional transcranial Doppler analysis, he said. However, the former is costly, time consuming, and not portable, and the latter has not proven very accurate.

As traditional Doppler analysis disregards the majority of waveform data, Dr. Hamilton and his colleagues developed an advanced platform that uses machine learning to analyze the entire shape of the cerebral blood flow velocity waveform through quantitative cerebral hemodynamics.

They compared the advanced analysis with traditional analysis among 69 high school athletes in contact sports who had sustained a concussion an average of 6 days earlier and a control group of 169 unaffected age-matched high school athletes from contact and noncontact sports.

Both groups had bilateral monitoring of blood flow in the middle cerebral artery with transcranial Doppler while they followed a standard cerebrovascular reactivity protocol that included rest and breath holding.

Results showed that for differentiating between athletes who did and did not have concussion, the advanced analysis had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 83%. (Sensitivity was 72%, specificity was 82%, and overall accuracy was 80%.)

In comparison, the area under the curve was substantially lower for the traditional analysis measures: It was 55% for mean velocity (100% sensitivity, 0% specificity, 76% accuracy), 52% for the pulsatility index (86% sensitivity, 23% specificity, 61% accuracy), and 60% for the cerebrovascular reactivity index (51% sensitivity, 68% specificity, 64% accuracy).

“Unfortunately, concussion diagnostics and management today are basically subjective,” Dr. Hamilton commented. The advanced analysis may therefore improve the situation by providing objective evidence of blood flow dysfunction after injury.

The new analysis platform “is easy to use and portable, and [testing] can be done very quickly, within 5 minutes,” he noted. “The nice thing is it can be done on the sideline, in the emergency room, or in a doctor’s office.”

The investigators will next use the advanced analysis to track recovery of blood flow regulation after sports-related concussion and will compare its performance with that of additional modalities, such as MRI, according to Dr. Hamilton. Furthermore, they are testing it in various other populations: adolescents, college athletes, and members of the military.

“Ultimately, blood flow dysfunction is also important in a wide variety of conditions, such as stroke and dementia,” he pointed out. “So those are conditions that we are looking at to study this year and moving forward in the future.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

VANCOUVER – A new transcranial Doppler platform that analyzes subtle changes in the cerebral blood flow waveform performed well in detecting sports-related concussion in a cohort study of 238 Los Angeles high school athletes.

The investigational headset device was able to differentiate between those with and without a recent concussion 83% of the time, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. In contrast, traditional transcranial Doppler analysis detected a recent concussion only 50%-60% of the time.

“Over the last few years, there has been growing evidence that cerebral hemodynamics are altered following sports-related concussion,” senior author Robert Hamilton, Ph.D., cofounder and chief science officer of Neural Analytics in Los Angeles, commented in a session and interview.

Most studies in this area have used MRI or traditional transcranial Doppler analysis, he said. However, the former is costly, time consuming, and not portable, and the latter has not proven very accurate.

As traditional Doppler analysis disregards the majority of waveform data, Dr. Hamilton and his colleagues developed an advanced platform that uses machine learning to analyze the entire shape of the cerebral blood flow velocity waveform through quantitative cerebral hemodynamics.

They compared the advanced analysis with traditional analysis among 69 high school athletes in contact sports who had sustained a concussion an average of 6 days earlier and a control group of 169 unaffected age-matched high school athletes from contact and noncontact sports.

Both groups had bilateral monitoring of blood flow in the middle cerebral artery with transcranial Doppler while they followed a standard cerebrovascular reactivity protocol that included rest and breath holding.

Results showed that for differentiating between athletes who did and did not have concussion, the advanced analysis had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 83%. (Sensitivity was 72%, specificity was 82%, and overall accuracy was 80%.)

In comparison, the area under the curve was substantially lower for the traditional analysis measures: It was 55% for mean velocity (100% sensitivity, 0% specificity, 76% accuracy), 52% for the pulsatility index (86% sensitivity, 23% specificity, 61% accuracy), and 60% for the cerebrovascular reactivity index (51% sensitivity, 68% specificity, 64% accuracy).

“Unfortunately, concussion diagnostics and management today are basically subjective,” Dr. Hamilton commented. The advanced analysis may therefore improve the situation by providing objective evidence of blood flow dysfunction after injury.

The new analysis platform “is easy to use and portable, and [testing] can be done very quickly, within 5 minutes,” he noted. “The nice thing is it can be done on the sideline, in the emergency room, or in a doctor’s office.”

The investigators will next use the advanced analysis to track recovery of blood flow regulation after sports-related concussion and will compare its performance with that of additional modalities, such as MRI, according to Dr. Hamilton. Furthermore, they are testing it in various other populations: adolescents, college athletes, and members of the military.

“Ultimately, blood flow dysfunction is also important in a wide variety of conditions, such as stroke and dementia,” he pointed out. “So those are conditions that we are looking at to study this year and moving forward in the future.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

AT THE AAN 2016 ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Advanced transcranial Doppler analysis may improve identification of athletes with concussion at the point of care.

Major finding: For differentiating between athletes who did and did not have concussion, the advanced analysis had an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 83%.

Data source: A cohort study of 69 concussed and 169 nonconcussed high school athletes.

Disclosures: Dr. Hamilton disclosed that he is a cofounder and chief science officer of Neural Analytics. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Product News: 05 2016

Aczone Gel 7.5%

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aczone (dapsone) Gel 7.5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 12 years and older. The new formula contains a higher concentration of dapsone (versus the 5% concentration) with the same tolerability and enhanced efficacy to treat both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne. Once-daily application and the pump delivery system aid in improving adherence to treatment. For more information, visit www.aczonehcp.com.

Cutanea Life Sciences

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc (CLS), an emerging US prescription product development company, unveils its new website, www.cutanea.com, to the dermatology community. The new digital presence demonstrates the company’s intent to change the way customers think about a valued dermatology partner. The CLS management team is well versed in the development and commercialization of dermatologic therapies. With product candidates in various stages of development that cover an array of skin conditions such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, and warts caused by human papillomavirus, CLS is committed to focusing on underserved patient needs, which will help health care professionals optimize their practice time through CLS’s dermatologic products and services.

Sernivo Spray 0.05%

Promius Pharma, LLC, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Sernivo (betamethasone dipropionate) Spray 0.05%, a corticosteroid for the treatment of mild to moderate plaque psoriasis in patients 18 years and older. Sernivo Spray should be used twice daily for 4 weeks and not beyond. In clinical trials more participants showed treatment success with Sernivo Spray versus vehicle at day 15 and day 29. For more information, visit www.promiuspharma.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces that the US Food and Drug Administration has accepted for filing a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children 2 months and older with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Aczone Gel 7.5%

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aczone (dapsone) Gel 7.5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 12 years and older. The new formula contains a higher concentration of dapsone (versus the 5% concentration) with the same tolerability and enhanced efficacy to treat both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne. Once-daily application and the pump delivery system aid in improving adherence to treatment. For more information, visit www.aczonehcp.com.

Cutanea Life Sciences

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc (CLS), an emerging US prescription product development company, unveils its new website, www.cutanea.com, to the dermatology community. The new digital presence demonstrates the company’s intent to change the way customers think about a valued dermatology partner. The CLS management team is well versed in the development and commercialization of dermatologic therapies. With product candidates in various stages of development that cover an array of skin conditions such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, and warts caused by human papillomavirus, CLS is committed to focusing on underserved patient needs, which will help health care professionals optimize their practice time through CLS’s dermatologic products and services.

Sernivo Spray 0.05%

Promius Pharma, LLC, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Sernivo (betamethasone dipropionate) Spray 0.05%, a corticosteroid for the treatment of mild to moderate plaque psoriasis in patients 18 years and older. Sernivo Spray should be used twice daily for 4 weeks and not beyond. In clinical trials more participants showed treatment success with Sernivo Spray versus vehicle at day 15 and day 29. For more information, visit www.promiuspharma.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces that the US Food and Drug Administration has accepted for filing a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children 2 months and older with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Aczone Gel 7.5%

Allergan announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Aczone (dapsone) Gel 7.5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 12 years and older. The new formula contains a higher concentration of dapsone (versus the 5% concentration) with the same tolerability and enhanced efficacy to treat both inflammatory and noninflammatory acne. Once-daily application and the pump delivery system aid in improving adherence to treatment. For more information, visit www.aczonehcp.com.

Cutanea Life Sciences

Cutanea Life Sciences, Inc (CLS), an emerging US prescription product development company, unveils its new website, www.cutanea.com, to the dermatology community. The new digital presence demonstrates the company’s intent to change the way customers think about a valued dermatology partner. The CLS management team is well versed in the development and commercialization of dermatologic therapies. With product candidates in various stages of development that cover an array of skin conditions such as acne, rosacea, psoriasis, and warts caused by human papillomavirus, CLS is committed to focusing on underserved patient needs, which will help health care professionals optimize their practice time through CLS’s dermatologic products and services.

Sernivo Spray 0.05%

Promius Pharma, LLC, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Sernivo (betamethasone dipropionate) Spray 0.05%, a corticosteroid for the treatment of mild to moderate plaque psoriasis in patients 18 years and older. Sernivo Spray should be used twice daily for 4 weeks and not beyond. In clinical trials more participants showed treatment success with Sernivo Spray versus vehicle at day 15 and day 29. For more information, visit www.promiuspharma.com.

Teflaro

Allergan announces that the US Food and Drug Administration has accepted for filing a supplemental new drug application for Teflaro (ceftaroline fosamil) to expand the label to include the treatment of children 2 months and older with acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) caused by Staphylococcus pneumoniae and other designated susceptible bacteria. Teflaro is a bactericidal cephalosporin with activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Teflaro is already approved for ABSSSI and CABP in adult patients. For more information, visit www.teflaro.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Sexual Orientation and Cancer Risk

Young people in sexual minorities are at higher risk of cancer because they engage in risky behavior more often, say researchers from City University of New York, Harvard, Boston’s Children’s Hospital, and San Diego State University.

The researchers analyzed data from 9,958 participants in the national Growing Up Today Study (1999-2010). The study participants were the children of the women in the Nurses’ Health Study II; those women were invited in 1996 to enroll their 9- to 14-year-old children. Of the participants, 84.5% reported being “completely” heterosexual, 12.1% were “mostly” heterosexual, 1.8% were lesbian or gay, and 1.6% were bisexual.

Related: Native Americans Address LGBT Health Issues

The researchers measured responses about tobacco and alcohol, diet and physical activity, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and sexually transmitted infections.

Compared with completely heterosexual women, lesbian, bisexual, and mostly heterosexual women more frequently engaged in multiple cancer-related risk behaviors. For instance, they were more likely to have smoked, to be overweight, and to have been physically inactive in the previous year. Bisexual and mostly heterosexual women were more likely to have had a sexually transmitted infection. Interestingly, heterosexual women were more likely to have used a tanning booth ≥ 10 times in the previous year.

Compared with heterosexual men, sexual-minority women were also more often engaged in risky behaviors. The differences between gay/bisexual men and heterosexual men were less marked, although gay men more often vomited to control their weight, compared with heterosexual men, and had a higher prevalence of STIs.

The literature, the researchers note, tends to focus on “ever or never” behavior. They were mindful, they say, that exposure to a potential carcinogen usually must occur over time, and that the likelihood of cancer increases with exposure, which is why they focused on assessing frequent engagement in each cancer-related risk behavior, long term. Their findings indicated that sexual minorities, relative to heterosexuals, are at risk for cancer through multiple risk behaviors—“concerning,” they add, because the “additive or synergistic effect of another cancer-related risk behavior may provoke or exacerbate a determinant of cancer: chronic inflammation.”

Source:

Rosario M, Li F, Wypij D, et al. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):698-706.

doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302977.

Young people in sexual minorities are at higher risk of cancer because they engage in risky behavior more often, say researchers from City University of New York, Harvard, Boston’s Children’s Hospital, and San Diego State University.

The researchers analyzed data from 9,958 participants in the national Growing Up Today Study (1999-2010). The study participants were the children of the women in the Nurses’ Health Study II; those women were invited in 1996 to enroll their 9- to 14-year-old children. Of the participants, 84.5% reported being “completely” heterosexual, 12.1% were “mostly” heterosexual, 1.8% were lesbian or gay, and 1.6% were bisexual.

Related: Native Americans Address LGBT Health Issues

The researchers measured responses about tobacco and alcohol, diet and physical activity, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and sexually transmitted infections.

Compared with completely heterosexual women, lesbian, bisexual, and mostly heterosexual women more frequently engaged in multiple cancer-related risk behaviors. For instance, they were more likely to have smoked, to be overweight, and to have been physically inactive in the previous year. Bisexual and mostly heterosexual women were more likely to have had a sexually transmitted infection. Interestingly, heterosexual women were more likely to have used a tanning booth ≥ 10 times in the previous year.

Compared with heterosexual men, sexual-minority women were also more often engaged in risky behaviors. The differences between gay/bisexual men and heterosexual men were less marked, although gay men more often vomited to control their weight, compared with heterosexual men, and had a higher prevalence of STIs.

The literature, the researchers note, tends to focus on “ever or never” behavior. They were mindful, they say, that exposure to a potential carcinogen usually must occur over time, and that the likelihood of cancer increases with exposure, which is why they focused on assessing frequent engagement in each cancer-related risk behavior, long term. Their findings indicated that sexual minorities, relative to heterosexuals, are at risk for cancer through multiple risk behaviors—“concerning,” they add, because the “additive or synergistic effect of another cancer-related risk behavior may provoke or exacerbate a determinant of cancer: chronic inflammation.”

Source:

Rosario M, Li F, Wypij D, et al. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):698-706.

doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302977.

Young people in sexual minorities are at higher risk of cancer because they engage in risky behavior more often, say researchers from City University of New York, Harvard, Boston’s Children’s Hospital, and San Diego State University.

The researchers analyzed data from 9,958 participants in the national Growing Up Today Study (1999-2010). The study participants were the children of the women in the Nurses’ Health Study II; those women were invited in 1996 to enroll their 9- to 14-year-old children. Of the participants, 84.5% reported being “completely” heterosexual, 12.1% were “mostly” heterosexual, 1.8% were lesbian or gay, and 1.6% were bisexual.

Related: Native Americans Address LGBT Health Issues

The researchers measured responses about tobacco and alcohol, diet and physical activity, exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and sexually transmitted infections.

Compared with completely heterosexual women, lesbian, bisexual, and mostly heterosexual women more frequently engaged in multiple cancer-related risk behaviors. For instance, they were more likely to have smoked, to be overweight, and to have been physically inactive in the previous year. Bisexual and mostly heterosexual women were more likely to have had a sexually transmitted infection. Interestingly, heterosexual women were more likely to have used a tanning booth ≥ 10 times in the previous year.

Compared with heterosexual men, sexual-minority women were also more often engaged in risky behaviors. The differences between gay/bisexual men and heterosexual men were less marked, although gay men more often vomited to control their weight, compared with heterosexual men, and had a higher prevalence of STIs.

The literature, the researchers note, tends to focus on “ever or never” behavior. They were mindful, they say, that exposure to a potential carcinogen usually must occur over time, and that the likelihood of cancer increases with exposure, which is why they focused on assessing frequent engagement in each cancer-related risk behavior, long term. Their findings indicated that sexual minorities, relative to heterosexuals, are at risk for cancer through multiple risk behaviors—“concerning,” they add, because the “additive or synergistic effect of another cancer-related risk behavior may provoke or exacerbate a determinant of cancer: chronic inflammation.”

Source:

Rosario M, Li F, Wypij D, et al. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):698-706.

doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302977.

Opioid reform legislation passes House committee

The House Energy & Commerce Committee has passed a comprehensive package of bills designed to curb the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Eleven opioid-related bills passed the full committee by voice vote on April 27 and April 28. Key provisions of the legislation would:

• Create an interagency task force to review best practices for pain management and prescribing.

• Require annual updates of federal opioid-prescribing guidelines.

• Authorize grants to test coprescribing opioids with buprenorphine or naloxone.

• Limit the number of pills prescribed.

• Increase the number of patients that a qualified addiction treatment specialist could see annually.

• Require an FDA advisory committee to review any new opioid proposed without abuse-deterrent properties.

• Require a detailed assessment of currently available inpatient and outpatient treatment beds.

• Prohibit the sale dextromethorphan-containing products to minors.

The full Senate also has a package of opioid-related bills to consider. On March 17, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions moved similar legislation to the Senate floor, including bills that would increase addiction patient panels, require coprescribing, and mandate insurance coverage of addiction treatment as required by current mental health parity laws.

Earlier this year, in a near unanimous vote, the Senate passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which calls for the creation of a federal pain management best practices interagency task force. No funding was attached to the legislation, however, and companion legislation remains in committee in the House.

Although the opioid bills had bipartisan support in the Energy & Commerce Committee, rancor may yet surface. During mark-up, three amendments were defeated mostly along party lines. The amendments would have increased the number of patients each qualified provider can treat with buprenorphine to a variety of levels – one amendment called for a maximum of 250 patients while others called for as many as 300 or 500. Supporters of the amendments said higher numbers would ensure treatment for many more patients while opponents expressed concern about sacrificing quality of care for quantity.

Another defeated amendment called for a $1 billion appropriation for increased opioid treatment, echoing President Obama’s call earlier this year. Opponents painted the proposal as “fiscally irresponsible.”

At press time, the House had not scheduled consideration on the opioid bills.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The House Energy & Commerce Committee has passed a comprehensive package of bills designed to curb the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Eleven opioid-related bills passed the full committee by voice vote on April 27 and April 28. Key provisions of the legislation would:

• Create an interagency task force to review best practices for pain management and prescribing.

• Require annual updates of federal opioid-prescribing guidelines.

• Authorize grants to test coprescribing opioids with buprenorphine or naloxone.

• Limit the number of pills prescribed.

• Increase the number of patients that a qualified addiction treatment specialist could see annually.

• Require an FDA advisory committee to review any new opioid proposed without abuse-deterrent properties.

• Require a detailed assessment of currently available inpatient and outpatient treatment beds.

• Prohibit the sale dextromethorphan-containing products to minors.

The full Senate also has a package of opioid-related bills to consider. On March 17, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions moved similar legislation to the Senate floor, including bills that would increase addiction patient panels, require coprescribing, and mandate insurance coverage of addiction treatment as required by current mental health parity laws.

Earlier this year, in a near unanimous vote, the Senate passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which calls for the creation of a federal pain management best practices interagency task force. No funding was attached to the legislation, however, and companion legislation remains in committee in the House.

Although the opioid bills had bipartisan support in the Energy & Commerce Committee, rancor may yet surface. During mark-up, three amendments were defeated mostly along party lines. The amendments would have increased the number of patients each qualified provider can treat with buprenorphine to a variety of levels – one amendment called for a maximum of 250 patients while others called for as many as 300 or 500. Supporters of the amendments said higher numbers would ensure treatment for many more patients while opponents expressed concern about sacrificing quality of care for quantity.

Another defeated amendment called for a $1 billion appropriation for increased opioid treatment, echoing President Obama’s call earlier this year. Opponents painted the proposal as “fiscally irresponsible.”

At press time, the House had not scheduled consideration on the opioid bills.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The House Energy & Commerce Committee has passed a comprehensive package of bills designed to curb the nation’s opioid epidemic.

Eleven opioid-related bills passed the full committee by voice vote on April 27 and April 28. Key provisions of the legislation would:

• Create an interagency task force to review best practices for pain management and prescribing.

• Require annual updates of federal opioid-prescribing guidelines.

• Authorize grants to test coprescribing opioids with buprenorphine or naloxone.

• Limit the number of pills prescribed.

• Increase the number of patients that a qualified addiction treatment specialist could see annually.

• Require an FDA advisory committee to review any new opioid proposed without abuse-deterrent properties.

• Require a detailed assessment of currently available inpatient and outpatient treatment beds.

• Prohibit the sale dextromethorphan-containing products to minors.

The full Senate also has a package of opioid-related bills to consider. On March 17, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions moved similar legislation to the Senate floor, including bills that would increase addiction patient panels, require coprescribing, and mandate insurance coverage of addiction treatment as required by current mental health parity laws.

Earlier this year, in a near unanimous vote, the Senate passed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which calls for the creation of a federal pain management best practices interagency task force. No funding was attached to the legislation, however, and companion legislation remains in committee in the House.

Although the opioid bills had bipartisan support in the Energy & Commerce Committee, rancor may yet surface. During mark-up, three amendments were defeated mostly along party lines. The amendments would have increased the number of patients each qualified provider can treat with buprenorphine to a variety of levels – one amendment called for a maximum of 250 patients while others called for as many as 300 or 500. Supporters of the amendments said higher numbers would ensure treatment for many more patients while opponents expressed concern about sacrificing quality of care for quantity.

Another defeated amendment called for a $1 billion appropriation for increased opioid treatment, echoing President Obama’s call earlier this year. Opponents painted the proposal as “fiscally irresponsible.”

At press time, the House had not scheduled consideration on the opioid bills.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM A HOUSE ENERGY & COMMERCE COMMITTEE HEARING

Training impacted performance of surgical quality measures

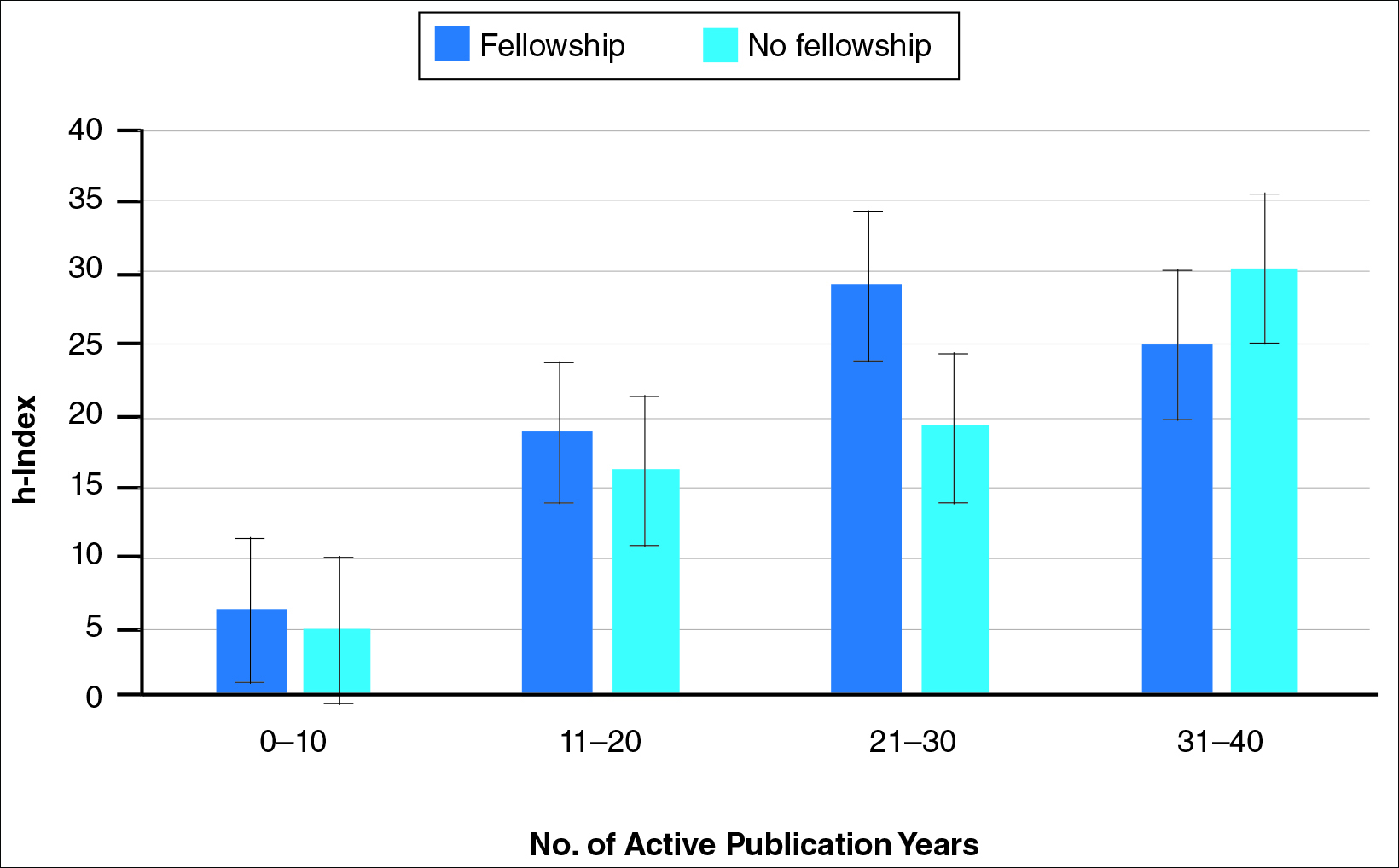

INDIAN WELLS, CALIF. – Surgeons with fellowship training in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery were significantly more likely to perform proposed quality measures at the time of hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse, compared with those who lack such training, a single-center study showed.

“The Physician Quality Reporting System was instituted as part of recent health care reform, with the aim of improving the reporting of quality measures, with the overall goal of improving the quality of care provided to patients throughout all areas of medicine,” Dr. Emily Adams-Piper said at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. “While there are many types of quality measures, including outcome measures and patient satisfaction measures, process measures may be the most directly applicable for the practicing clinician, because they provide recommended actions during specific patient encounters that can guide practice.”

Dr. Adams-Piper, a resident physician in the division of urogynecology at the University of California, Irvine, and her associates set out to investigate the use of proposed quality measures at the time of hysterectomy for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) among women receiving care from Southern California Permanente Medical Group, a large HMO.

They wanted to know if training background affected the rate of performance of four different quality measures related to hysterectomy for POP: offering conservative treatment prior to the surgical treatment of POP, quantitative assessment of POP with either a Baden-Walker or a POP-Q exam, apical support procedure performed at the time of hysterectomy for prolapse, and performance of intraoperative cystoscopy.

Patients who underwent hysterectomy for POP in 2008 were eligible for the study. The researchers reviewed electronic medical records for clinical and demographic data and categorized surgeons by their level of training.

“They were considered fellowship trained if they had pursued additional formal subspecialty training in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery,” Dr. Adams-Piper explained. “Surgeons were considered grandfathered if they subsequently took the FPMRS [Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery] boards when they became available in 2013. Surgeons were considered generalist if they fit into neither of these two categories and completed a residency in ob.gyn.”

Chi-squared tests were used to compare demographics and performance of the proposed quality measures. Of the 662 hysterectomies performed in 2008, 328 were included in the final analysis. The mean patient age was 60 years, the mean parity was 2.9, and the mean body mass index was 27.9 kg/m2.

Overall performance of the four proposed quality measures was high, ranging from 82%-87%. More than half of quality assessments (58%) were performed with the POP-Q exam, while the majority of apical support procedures were uterosacral ligament vault suspensions (67%), followed by sacrocolpopexy (18%), McCall culdoplasty (12%), and sacrospinous ligament fixation (3%).

When categorized by training, fellowship-trained surgeons performed 133 hysterectomies, “grandfathered” surgeons performed 55, and generalist gynecologic surgeons performed 140. Fellowship-trained surgeons performed each of the four proposed quality measures more often than did grandfathered surgeons, who performed them more often than generalist gynecologic surgeons did.

Specifically, conservative treatment was offered by 94% of fellowship-trained surgeons, 87% of grandfathered surgeons, and 76% of generalist gynecologic surgeons (P = .0002). Qualitative preoperative assessment of POP was performed by 99% of fellowship-trained surgeons, 93% of grandfathered surgeons, and 73% of generalist gynecologic surgeons (three-way comparison reached statistical significance, with a P less than .0001).

Apical repair was performed by 96% of fellowship-trained surgeons, 82% of grandfathered surgeons, and 69% of generalist gynecologic surgeons (P less than .0001). Finally, cystoscopy was performed by 98% of fellowship-trained surgeons, 91% of grandfathered surgeons, and 72% of generalist gynecologic surgeons (P less than .0001).

When the researchers evaluated the cumulative performance of all measures in the same patient, fellowship-trained surgeons had the highest rates (89%, compared with 62% of grandfathered surgeons, and 39% of generalist gynecologic surgeons; P less than .0001).

“When we looked at the patient characteristics and their distribution across the surgeon training backgrounds, we found no significant differences in the age, BMI, gravidity, or parity of the subjects that underwent surgeries with the three groups,” Dr. Adams-Piper said.