User login

Medicare 'Hospital Star Rating' May Correspond to Patient Outcomes

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been letting patients grade their hospital experiences, and those "patient experience scores" may give some insight into a hospital's health outcomes, a new study suggests.

Some people have been concerned that patient experience isn't the most important factor to measure, said coauthor Dr. Ashish K. Jha, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

"Medicare has been putting a lot of data out for a long time, but the broad consensus has been it's very hard for consumers to use this info," Jha told Reuters Health by phone. "CMS responded by giving out star ratings that consumers can understand easily."

The five-star rating system is based on patients' answers to 27 questions about a recent hospital stay. Questions cover communication with nurses and doctors, the responsiveness of hospital staff, the hospital's cleanliness and quietness, pain management, communication about medicines, discharge

information, and would they recommend the hospital.

The survey is administered to a random sample of adult patients between 48 hours and six weeks after hospital discharge. Consumers can compare their local hospitals online.

For the new study, the researchers compared the CMS patient-experience ratings at more than 3,000 hospitals in October 2015 to data from those hospitals on death or readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Patients in the study had been hospitalized for myocardial infarction, pneumonia or heart failure.

Of the 3,000 hospitals, 125 had five stars, more than 2,000 had three or four stars, 623 had two stars, and 76 had only one star.

Four and five-star hospitals tended to be small rural nonteaching hospitals in the Midwest.

Five-star hospitals had the lowest average patient death rate, 9.8 percent over the 30 days following discharge, while four three and two-star hospitals all had just over 10 percent mortality rates and one-star hospitals had an average 11.2 percent mortality rate, as reported in a research letter online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Five-star hospitals also readmitted less than 20 percent of patients over the next month, while other hospitals all readmitted at least that many.

The data only included Medicare patients, who are older andmay not have the same results as younger patients, and there was not much difference between two, three and four-star hospitals, the authors note.

"If you use the star rating you're more likely to end up at a high quality hospital," Jha said. "But I wouldn't use only the star rating to choose a hospital."

"I don't think these data are enough to by themselves to suggest that (patients) should use the star rating as a single guide to choose an institution," agreed Dr. Joshua J. Fenton of the University of California, Davis, who was not part of the new study.

No large hospitals had five stars, and more than half of the five-star facilities didn't have an intensive care unit, Fenton told Reuters Health by phone.

"I can say from practicing in a rural hospital for a few years and we did not have an ICU, when we hospitalized someone with pneumonia or congestive heart failure, we would certainly not have kept them there if we thought it was likely there would be a complication," he said.

Smaller rural hospitals "select" less acute patients, he said. The authors of the new study tried to account for that, but it may still have affected the results.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been letting patients grade their hospital experiences, and those "patient experience scores" may give some insight into a hospital's health outcomes, a new study suggests.

Some people have been concerned that patient experience isn't the most important factor to measure, said coauthor Dr. Ashish K. Jha, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

"Medicare has been putting a lot of data out for a long time, but the broad consensus has been it's very hard for consumers to use this info," Jha told Reuters Health by phone. "CMS responded by giving out star ratings that consumers can understand easily."

The five-star rating system is based on patients' answers to 27 questions about a recent hospital stay. Questions cover communication with nurses and doctors, the responsiveness of hospital staff, the hospital's cleanliness and quietness, pain management, communication about medicines, discharge

information, and would they recommend the hospital.

The survey is administered to a random sample of adult patients between 48 hours and six weeks after hospital discharge. Consumers can compare their local hospitals online.

For the new study, the researchers compared the CMS patient-experience ratings at more than 3,000 hospitals in October 2015 to data from those hospitals on death or readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Patients in the study had been hospitalized for myocardial infarction, pneumonia or heart failure.

Of the 3,000 hospitals, 125 had five stars, more than 2,000 had three or four stars, 623 had two stars, and 76 had only one star.

Four and five-star hospitals tended to be small rural nonteaching hospitals in the Midwest.

Five-star hospitals had the lowest average patient death rate, 9.8 percent over the 30 days following discharge, while four three and two-star hospitals all had just over 10 percent mortality rates and one-star hospitals had an average 11.2 percent mortality rate, as reported in a research letter online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Five-star hospitals also readmitted less than 20 percent of patients over the next month, while other hospitals all readmitted at least that many.

The data only included Medicare patients, who are older andmay not have the same results as younger patients, and there was not much difference between two, three and four-star hospitals, the authors note.

"If you use the star rating you're more likely to end up at a high quality hospital," Jha said. "But I wouldn't use only the star rating to choose a hospital."

"I don't think these data are enough to by themselves to suggest that (patients) should use the star rating as a single guide to choose an institution," agreed Dr. Joshua J. Fenton of the University of California, Davis, who was not part of the new study.

No large hospitals had five stars, and more than half of the five-star facilities didn't have an intensive care unit, Fenton told Reuters Health by phone.

"I can say from practicing in a rural hospital for a few years and we did not have an ICU, when we hospitalized someone with pneumonia or congestive heart failure, we would certainly not have kept them there if we thought it was likely there would be a complication," he said.

Smaller rural hospitals "select" less acute patients, he said. The authors of the new study tried to account for that, but it may still have affected the results.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been letting patients grade their hospital experiences, and those "patient experience scores" may give some insight into a hospital's health outcomes, a new study suggests.

Some people have been concerned that patient experience isn't the most important factor to measure, said coauthor Dr. Ashish K. Jha, of the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.

"Medicare has been putting a lot of data out for a long time, but the broad consensus has been it's very hard for consumers to use this info," Jha told Reuters Health by phone. "CMS responded by giving out star ratings that consumers can understand easily."

The five-star rating system is based on patients' answers to 27 questions about a recent hospital stay. Questions cover communication with nurses and doctors, the responsiveness of hospital staff, the hospital's cleanliness and quietness, pain management, communication about medicines, discharge

information, and would they recommend the hospital.

The survey is administered to a random sample of adult patients between 48 hours and six weeks after hospital discharge. Consumers can compare their local hospitals online.

For the new study, the researchers compared the CMS patient-experience ratings at more than 3,000 hospitals in October 2015 to data from those hospitals on death or readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Patients in the study had been hospitalized for myocardial infarction, pneumonia or heart failure.

Of the 3,000 hospitals, 125 had five stars, more than 2,000 had three or four stars, 623 had two stars, and 76 had only one star.

Four and five-star hospitals tended to be small rural nonteaching hospitals in the Midwest.

Five-star hospitals had the lowest average patient death rate, 9.8 percent over the 30 days following discharge, while four three and two-star hospitals all had just over 10 percent mortality rates and one-star hospitals had an average 11.2 percent mortality rate, as reported in a research letter online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Five-star hospitals also readmitted less than 20 percent of patients over the next month, while other hospitals all readmitted at least that many.

The data only included Medicare patients, who are older andmay not have the same results as younger patients, and there was not much difference between two, three and four-star hospitals, the authors note.

"If you use the star rating you're more likely to end up at a high quality hospital," Jha said. "But I wouldn't use only the star rating to choose a hospital."

"I don't think these data are enough to by themselves to suggest that (patients) should use the star rating as a single guide to choose an institution," agreed Dr. Joshua J. Fenton of the University of California, Davis, who was not part of the new study.

No large hospitals had five stars, and more than half of the five-star facilities didn't have an intensive care unit, Fenton told Reuters Health by phone.

"I can say from practicing in a rural hospital for a few years and we did not have an ICU, when we hospitalized someone with pneumonia or congestive heart failure, we would certainly not have kept them there if we thought it was likely there would be a complication," he said.

Smaller rural hospitals "select" less acute patients, he said. The authors of the new study tried to account for that, but it may still have affected the results.

All-oral combo extends PFS in rel/ref MM

Photo courtesy of ASH

In the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial, adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone significantly extended progression-free survival (PFS), with limited additional toxicity, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The median PFS was about 21 months for patients who received ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd) and about 15 months for those who received placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd).

Gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs), rash, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia were more common in the IRd arm than the Rd arm.

These results were published in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Results from this trial were previously presented at ASH 2015, but the data in NEJM differ slightly from that presentation.

“NEJM has published the results of the first phase 3 study supporting an all-oral triplet regimen containing a proteasome inhibitor in multiple myeloma,” said study author Philippe Moreau, MD, of University of Nantes in France.

“The TOURMALINE-MM1 results demonstrated that ixazomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone is an effective and tolerable oral regimen with a manageable safety profile for patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma.”

TOURMALINE-MM1 enrolled 722 patients with relapsed (77%), refractory (11%), relapsed and refractory (12%), or primary refractory (6%) MM.

The patients were randomized to receive IRd (n=360) or Rd (n=362). Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients were male.

About 60% of patients in both arms had received 1 prior therapy, roughly 30% had received 2, and about 10% had received 3. Seventy percent of patients in both arms had received prior treatment with a proteasome inhibitor, and about 55% had received an immunomodulatory drug.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS. And the researchers saw a significant improvement in PFS for the IRd arm compared to the Rd arm. The median PFS was 20.6 months and 14.7 months, respectively. The hazard ratio was 0.74 (P=0.01).

There was a benefit in PFS in the IRd arm across pre-specified patient subgroups, including patients with poor prognosis, such as elderly patients, those who had received 2 or 3 prior therapies, those with advanced stage disease, and those with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival had not been reached in either treatment arm.

The overall response rates were 78% in the IRd arm and 72% in the Rd arm. The complete response rates were 12% and 7%, respectively, and the stringent complete response rates were 2% and <1%, respectively.

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15.0 months, respectively.

Safety

AEs occurred in 98% of patients in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 or higher AEs occurred in 74% and 69% of patients, respectively, serious AEs occurred in 47% and 49%, respectively, and on-study deaths occurred in 4% and 6%, respectively.

Grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia was more frequent in the IRd arm (12% and 7%, respectively) than in the Rd arm (5% and 4%, respectively). Rash also occurred more frequently in the IRd arm than in the Rd arm (36% and 23%, respectively).

Gastrointestinal AEs were more frequent in the IRd arm than the Rd arm, including diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), and vomiting (23% vs 12%).

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy was 27% in the IRd arm and 22% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 events occurred in 2% of patients in each arm, and no grade 4 events were reported.

Roughly the same percentage of patients developed new primary malignant tumors—5% in the IRd arm and 4% in the Rd arm. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

In the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial, adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone significantly extended progression-free survival (PFS), with limited additional toxicity, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The median PFS was about 21 months for patients who received ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd) and about 15 months for those who received placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd).

Gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs), rash, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia were more common in the IRd arm than the Rd arm.

These results were published in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Results from this trial were previously presented at ASH 2015, but the data in NEJM differ slightly from that presentation.

“NEJM has published the results of the first phase 3 study supporting an all-oral triplet regimen containing a proteasome inhibitor in multiple myeloma,” said study author Philippe Moreau, MD, of University of Nantes in France.

“The TOURMALINE-MM1 results demonstrated that ixazomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone is an effective and tolerable oral regimen with a manageable safety profile for patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma.”

TOURMALINE-MM1 enrolled 722 patients with relapsed (77%), refractory (11%), relapsed and refractory (12%), or primary refractory (6%) MM.

The patients were randomized to receive IRd (n=360) or Rd (n=362). Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients were male.

About 60% of patients in both arms had received 1 prior therapy, roughly 30% had received 2, and about 10% had received 3. Seventy percent of patients in both arms had received prior treatment with a proteasome inhibitor, and about 55% had received an immunomodulatory drug.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS. And the researchers saw a significant improvement in PFS for the IRd arm compared to the Rd arm. The median PFS was 20.6 months and 14.7 months, respectively. The hazard ratio was 0.74 (P=0.01).

There was a benefit in PFS in the IRd arm across pre-specified patient subgroups, including patients with poor prognosis, such as elderly patients, those who had received 2 or 3 prior therapies, those with advanced stage disease, and those with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival had not been reached in either treatment arm.

The overall response rates were 78% in the IRd arm and 72% in the Rd arm. The complete response rates were 12% and 7%, respectively, and the stringent complete response rates were 2% and <1%, respectively.

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15.0 months, respectively.

Safety

AEs occurred in 98% of patients in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 or higher AEs occurred in 74% and 69% of patients, respectively, serious AEs occurred in 47% and 49%, respectively, and on-study deaths occurred in 4% and 6%, respectively.

Grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia was more frequent in the IRd arm (12% and 7%, respectively) than in the Rd arm (5% and 4%, respectively). Rash also occurred more frequently in the IRd arm than in the Rd arm (36% and 23%, respectively).

Gastrointestinal AEs were more frequent in the IRd arm than the Rd arm, including diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), and vomiting (23% vs 12%).

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy was 27% in the IRd arm and 22% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 events occurred in 2% of patients in each arm, and no grade 4 events were reported.

Roughly the same percentage of patients developed new primary malignant tumors—5% in the IRd arm and 4% in the Rd arm. ![]()

Photo courtesy of ASH

In the phase 3 TOURMALINE-MM1 trial, adding the oral proteasome inhibitor ixazomib to treatment with lenalidomide and dexamethasone significantly extended progression-free survival (PFS), with limited additional toxicity, in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The median PFS was about 21 months for patients who received ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (IRd) and about 15 months for those who received placebo, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (Rd).

Gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs), rash, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia were more common in the IRd arm than the Rd arm.

These results were published in NEJM. The study was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Results from this trial were previously presented at ASH 2015, but the data in NEJM differ slightly from that presentation.

“NEJM has published the results of the first phase 3 study supporting an all-oral triplet regimen containing a proteasome inhibitor in multiple myeloma,” said study author Philippe Moreau, MD, of University of Nantes in France.

“The TOURMALINE-MM1 results demonstrated that ixazomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone is an effective and tolerable oral regimen with a manageable safety profile for patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma.”

TOURMALINE-MM1 enrolled 722 patients with relapsed (77%), refractory (11%), relapsed and refractory (12%), or primary refractory (6%) MM.

The patients were randomized to receive IRd (n=360) or Rd (n=362). Baseline patient characteristics were similar between the treatment arms. The median age was 66 in both arms (overall range, 30-91), and nearly 60% of patients were male.

About 60% of patients in both arms had received 1 prior therapy, roughly 30% had received 2, and about 10% had received 3. Seventy percent of patients in both arms had received prior treatment with a proteasome inhibitor, and about 55% had received an immunomodulatory drug.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was PFS. And the researchers saw a significant improvement in PFS for the IRd arm compared to the Rd arm. The median PFS was 20.6 months and 14.7 months, respectively. The hazard ratio was 0.74 (P=0.01).

There was a benefit in PFS in the IRd arm across pre-specified patient subgroups, including patients with poor prognosis, such as elderly patients, those who had received 2 or 3 prior therapies, those with advanced stage disease, and those with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities.

At a median follow-up of about 23 months, the median overall survival had not been reached in either treatment arm.

The overall response rates were 78% in the IRd arm and 72% in the Rd arm. The complete response rates were 12% and 7%, respectively, and the stringent complete response rates were 2% and <1%, respectively.

The median time to response was 1.1 months in the IRd arm and 1.9 months in the Rd arm. The median duration of response was 20.5 months and 15.0 months, respectively.

Safety

AEs occurred in 98% of patients in the IRd arm and 99% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 or higher AEs occurred in 74% and 69% of patients, respectively, serious AEs occurred in 47% and 49%, respectively, and on-study deaths occurred in 4% and 6%, respectively.

Grade 3 and 4 thrombocytopenia was more frequent in the IRd arm (12% and 7%, respectively) than in the Rd arm (5% and 4%, respectively). Rash also occurred more frequently in the IRd arm than in the Rd arm (36% and 23%, respectively).

Gastrointestinal AEs were more frequent in the IRd arm than the Rd arm, including diarrhea (45% vs 39%), constipation (35% vs 26%), nausea (29% vs 22%), and vomiting (23% vs 12%).

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy was 27% in the IRd arm and 22% in the Rd arm. Grade 3 events occurred in 2% of patients in each arm, and no grade 4 events were reported.

Roughly the same percentage of patients developed new primary malignant tumors—5% in the IRd arm and 4% in the Rd arm. ![]()

Biomarker may predict sensitivity to PIs in MM

in a thermal cycler

Photo by Karl Mumm

Measuring expression of the gene TJP1 could help determine which multiple myeloma (MM) patients are most likely to benefit from treatment with proteasome inhibitors (PIs), according to a study published in Cancer Cell.

Investigators found that TJP1 enhanced PI sensitivity in vitro and in vivo.

When they analyzed patient data, the team found that high TJP1 expression in patients’ MM cells was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of responding to bortezomib and a longer response duration.

“Proteasome inhibitors form the cornerstone of our standard therapy for multiple myeloma,” said study author Robert Orlowski, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“However, no biomarkers have been clinically validated that can identify patients most likely to respond to this treatment. Our findings provide a rationale for use of TJP1 as the first biomarker to select patients who are most and least likely to benefit from proteasome inhibitors.”

At the start of this study, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues examined gene-expression profiles of ANBL-6 and KAS-6/1 wild-type and bortezomib-resistant MM cells and found that TJP1 was downregulated in the resistant cells.

To further study the role of TJP1 in PI resistance, the investigators conducted experiments with RPMI 8226 and U266 MM cell lines (models that expressed high TJP1 levels) and MOLP-8 (a model that expressed low levels).

They found that knocking down TJP1 in RPMI 8226 and U266 cells with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) preserved the cells’ viability after exposure to bortezomib or carfilzomib. On the other hand, TJP1 overexpression sensitized MOLP-8 cells to the PIs.

In mice, RPMI 8226/TJP1 shRNA tumors were less sensitive to bortezomib than RPMI 8226/control tumors. And mice with MOLP-8/TJP1 shRNA tumors had a greater reduction in tumor growth after bortezomib treatment than MOLP-8/control mice.

Further investigation revealed that TJP1 modulates signaling through a pathway involving EGFR, JAK1, and STAT3. This finding supports the hypothesis that plasma cells expressing low TJP1 levels have both high EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 activity and high proteasome content.

“Therefore, these plasma cells were resistant to proteasome inhibitors,” Dr Orlowski explained. “Moreover, they demonstrated a previously unknown role for EGFR signaling in myeloma and for STAT3 in controlling the level of proteasomes in cells and, therefore, the cell’s ability to break down proteins.”

“This study allows us to identify promising future directions to overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance in patients with high signaling through the EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 pathway by offering combination therapies such as bortezomib with either the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib or a JAK1 inhibitor such as ruxolitinib.”

Finally, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues found that patients whose MM cells expressed low TJP1 levels were significantly less likely to achieve a response or benefit from bortezomib.

Patients who achieved a response after bortezomib across multiple studies had significantly higher TJP1 expression than nonresponders. And patients with the highest TJP1 expression levels had the longest time to progression. ![]()

in a thermal cycler

Photo by Karl Mumm

Measuring expression of the gene TJP1 could help determine which multiple myeloma (MM) patients are most likely to benefit from treatment with proteasome inhibitors (PIs), according to a study published in Cancer Cell.

Investigators found that TJP1 enhanced PI sensitivity in vitro and in vivo.

When they analyzed patient data, the team found that high TJP1 expression in patients’ MM cells was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of responding to bortezomib and a longer response duration.

“Proteasome inhibitors form the cornerstone of our standard therapy for multiple myeloma,” said study author Robert Orlowski, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“However, no biomarkers have been clinically validated that can identify patients most likely to respond to this treatment. Our findings provide a rationale for use of TJP1 as the first biomarker to select patients who are most and least likely to benefit from proteasome inhibitors.”

At the start of this study, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues examined gene-expression profiles of ANBL-6 and KAS-6/1 wild-type and bortezomib-resistant MM cells and found that TJP1 was downregulated in the resistant cells.

To further study the role of TJP1 in PI resistance, the investigators conducted experiments with RPMI 8226 and U266 MM cell lines (models that expressed high TJP1 levels) and MOLP-8 (a model that expressed low levels).

They found that knocking down TJP1 in RPMI 8226 and U266 cells with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) preserved the cells’ viability after exposure to bortezomib or carfilzomib. On the other hand, TJP1 overexpression sensitized MOLP-8 cells to the PIs.

In mice, RPMI 8226/TJP1 shRNA tumors were less sensitive to bortezomib than RPMI 8226/control tumors. And mice with MOLP-8/TJP1 shRNA tumors had a greater reduction in tumor growth after bortezomib treatment than MOLP-8/control mice.

Further investigation revealed that TJP1 modulates signaling through a pathway involving EGFR, JAK1, and STAT3. This finding supports the hypothesis that plasma cells expressing low TJP1 levels have both high EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 activity and high proteasome content.

“Therefore, these plasma cells were resistant to proteasome inhibitors,” Dr Orlowski explained. “Moreover, they demonstrated a previously unknown role for EGFR signaling in myeloma and for STAT3 in controlling the level of proteasomes in cells and, therefore, the cell’s ability to break down proteins.”

“This study allows us to identify promising future directions to overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance in patients with high signaling through the EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 pathway by offering combination therapies such as bortezomib with either the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib or a JAK1 inhibitor such as ruxolitinib.”

Finally, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues found that patients whose MM cells expressed low TJP1 levels were significantly less likely to achieve a response or benefit from bortezomib.

Patients who achieved a response after bortezomib across multiple studies had significantly higher TJP1 expression than nonresponders. And patients with the highest TJP1 expression levels had the longest time to progression. ![]()

in a thermal cycler

Photo by Karl Mumm

Measuring expression of the gene TJP1 could help determine which multiple myeloma (MM) patients are most likely to benefit from treatment with proteasome inhibitors (PIs), according to a study published in Cancer Cell.

Investigators found that TJP1 enhanced PI sensitivity in vitro and in vivo.

When they analyzed patient data, the team found that high TJP1 expression in patients’ MM cells was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of responding to bortezomib and a longer response duration.

“Proteasome inhibitors form the cornerstone of our standard therapy for multiple myeloma,” said study author Robert Orlowski, MD, PhD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“However, no biomarkers have been clinically validated that can identify patients most likely to respond to this treatment. Our findings provide a rationale for use of TJP1 as the first biomarker to select patients who are most and least likely to benefit from proteasome inhibitors.”

At the start of this study, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues examined gene-expression profiles of ANBL-6 and KAS-6/1 wild-type and bortezomib-resistant MM cells and found that TJP1 was downregulated in the resistant cells.

To further study the role of TJP1 in PI resistance, the investigators conducted experiments with RPMI 8226 and U266 MM cell lines (models that expressed high TJP1 levels) and MOLP-8 (a model that expressed low levels).

They found that knocking down TJP1 in RPMI 8226 and U266 cells with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) preserved the cells’ viability after exposure to bortezomib or carfilzomib. On the other hand, TJP1 overexpression sensitized MOLP-8 cells to the PIs.

In mice, RPMI 8226/TJP1 shRNA tumors were less sensitive to bortezomib than RPMI 8226/control tumors. And mice with MOLP-8/TJP1 shRNA tumors had a greater reduction in tumor growth after bortezomib treatment than MOLP-8/control mice.

Further investigation revealed that TJP1 modulates signaling through a pathway involving EGFR, JAK1, and STAT3. This finding supports the hypothesis that plasma cells expressing low TJP1 levels have both high EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 activity and high proteasome content.

“Therefore, these plasma cells were resistant to proteasome inhibitors,” Dr Orlowski explained. “Moreover, they demonstrated a previously unknown role for EGFR signaling in myeloma and for STAT3 in controlling the level of proteasomes in cells and, therefore, the cell’s ability to break down proteins.”

“This study allows us to identify promising future directions to overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance in patients with high signaling through the EGFR/JAK1/STAT3 pathway by offering combination therapies such as bortezomib with either the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib or a JAK1 inhibitor such as ruxolitinib.”

Finally, Dr Orlowski and his colleagues found that patients whose MM cells expressed low TJP1 levels were significantly less likely to achieve a response or benefit from bortezomib.

Patients who achieved a response after bortezomib across multiple studies had significantly higher TJP1 expression than nonresponders. And patients with the highest TJP1 expression levels had the longest time to progression. ![]()

Cancer diagnosis linked to mental health disorders

A recent cancer diagnosis is associated with an increased risk for mental health disorders and increased use of psychiatric medications, according to a large, nationwide study conducted in Sweden.

Overall, there was an increased risk of mental health disorders from 10 months before a cancer diagnosis that peaked during the first week after diagnosis and decreased after that, although the risk remained elevated at 10 years after diagnosis.

In addition, there was an increased use of psychiatric medications from 1 month before cancer diagnosis that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis and remained elevated 2 years after diagnosis.

Donghao Lu, MD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden and colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in JAMA Oncology.

The study included 304,118 patients with cancer and 3,041,174 cancer-free individuals randomly selected from the Swedish population for comparison.

The researchers investigated changes in risk for several common and potentially stress-related mental disorders—including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, somatoform/conversion disorder, and stress reaction/adjustment disorder—from the cancer diagnostic workup through to post-diagnosis.

They found the relative rate for all of the mental disorders studied started to increase from 10 months before cancer diagnosis, with a hazard ratio [HR] of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate peaked during the first week after diagnosis, with an HR of 6.7 (95%CI, 6.1-7.4). It decreased rapidly thereafter but was still elevated 10 years after diagnosis, with an HR of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate elevation was clear for all of the main cancers, including hematologic malignancies, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Among the cancer patients, the mental disorder with the highest cumulative incidence was depression. This was followed by anxiety and stress reaction/adjustment disorder.

When compared to controls, the cancer patients had a higher cumulative incidence of most of the mental disorders. The exception was somatoform/conversion disorder.

The researchers also examined the use of psychiatric medications for patients with cancer to assess milder mental health conditions and symptoms.

The team found an increased use of psychiatric medications in cancer patients compared to controls, from 1 month before diagnosis—12.2% vs 11.7% (P=0.04)—that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis—18.1% vs 11.9% (P<0.001)—and was still elevated 2 years after diagnosis—15.4% vs 12.7% (P<0.001).

The researchers said the results of this study support the existing guidelines of integrating psychological management into cancer care and call for extended vigilance for multiple mental disorders starting from the time of the cancer diagnostic workup. ![]()

A recent cancer diagnosis is associated with an increased risk for mental health disorders and increased use of psychiatric medications, according to a large, nationwide study conducted in Sweden.

Overall, there was an increased risk of mental health disorders from 10 months before a cancer diagnosis that peaked during the first week after diagnosis and decreased after that, although the risk remained elevated at 10 years after diagnosis.

In addition, there was an increased use of psychiatric medications from 1 month before cancer diagnosis that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis and remained elevated 2 years after diagnosis.

Donghao Lu, MD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden and colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in JAMA Oncology.

The study included 304,118 patients with cancer and 3,041,174 cancer-free individuals randomly selected from the Swedish population for comparison.

The researchers investigated changes in risk for several common and potentially stress-related mental disorders—including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, somatoform/conversion disorder, and stress reaction/adjustment disorder—from the cancer diagnostic workup through to post-diagnosis.

They found the relative rate for all of the mental disorders studied started to increase from 10 months before cancer diagnosis, with a hazard ratio [HR] of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate peaked during the first week after diagnosis, with an HR of 6.7 (95%CI, 6.1-7.4). It decreased rapidly thereafter but was still elevated 10 years after diagnosis, with an HR of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate elevation was clear for all of the main cancers, including hematologic malignancies, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Among the cancer patients, the mental disorder with the highest cumulative incidence was depression. This was followed by anxiety and stress reaction/adjustment disorder.

When compared to controls, the cancer patients had a higher cumulative incidence of most of the mental disorders. The exception was somatoform/conversion disorder.

The researchers also examined the use of psychiatric medications for patients with cancer to assess milder mental health conditions and symptoms.

The team found an increased use of psychiatric medications in cancer patients compared to controls, from 1 month before diagnosis—12.2% vs 11.7% (P=0.04)—that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis—18.1% vs 11.9% (P<0.001)—and was still elevated 2 years after diagnosis—15.4% vs 12.7% (P<0.001).

The researchers said the results of this study support the existing guidelines of integrating psychological management into cancer care and call for extended vigilance for multiple mental disorders starting from the time of the cancer diagnostic workup. ![]()

A recent cancer diagnosis is associated with an increased risk for mental health disorders and increased use of psychiatric medications, according to a large, nationwide study conducted in Sweden.

Overall, there was an increased risk of mental health disorders from 10 months before a cancer diagnosis that peaked during the first week after diagnosis and decreased after that, although the risk remained elevated at 10 years after diagnosis.

In addition, there was an increased use of psychiatric medications from 1 month before cancer diagnosis that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis and remained elevated 2 years after diagnosis.

Donghao Lu, MD, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden and colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in JAMA Oncology.

The study included 304,118 patients with cancer and 3,041,174 cancer-free individuals randomly selected from the Swedish population for comparison.

The researchers investigated changes in risk for several common and potentially stress-related mental disorders—including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, somatoform/conversion disorder, and stress reaction/adjustment disorder—from the cancer diagnostic workup through to post-diagnosis.

They found the relative rate for all of the mental disorders studied started to increase from 10 months before cancer diagnosis, with a hazard ratio [HR] of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate peaked during the first week after diagnosis, with an HR of 6.7 (95%CI, 6.1-7.4). It decreased rapidly thereafter but was still elevated 10 years after diagnosis, with an HR of 1.1 (95%CI, 1.1-1.2).

The rate elevation was clear for all of the main cancers, including hematologic malignancies, except for nonmelanoma skin cancer.

Among the cancer patients, the mental disorder with the highest cumulative incidence was depression. This was followed by anxiety and stress reaction/adjustment disorder.

When compared to controls, the cancer patients had a higher cumulative incidence of most of the mental disorders. The exception was somatoform/conversion disorder.

The researchers also examined the use of psychiatric medications for patients with cancer to assess milder mental health conditions and symptoms.

The team found an increased use of psychiatric medications in cancer patients compared to controls, from 1 month before diagnosis—12.2% vs 11.7% (P=0.04)—that peaked at about 3 months after diagnosis—18.1% vs 11.9% (P<0.001)—and was still elevated 2 years after diagnosis—15.4% vs 12.7% (P<0.001).

The researchers said the results of this study support the existing guidelines of integrating psychological management into cancer care and call for extended vigilance for multiple mental disorders starting from the time of the cancer diagnostic workup. ![]()

Costs for orally administered cancer drugs on the rise

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New orally administered cancer drugs are much more expensive in their first year on the market than such drugs launched about 15 years ago, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The research showed that a month of treatment with orally administered cancer drugs introduced in 2014 was, on average, 6 times more expensive at launch than monthly treatment costs for such drugs introduced in 2000, after adjusting for inflation.

In addition, most existing therapies had substantial price increases from the time they were launched to 2014.

“The major trend here is that these products are just getting more expensive over time,” said study author Stacie Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

For this study, Dr Dusetzina evaluated what commercial health insurance companies and patients paid for prescription fills—before rebates and discounts—for 32 orally administered cancer drugs from 2000 to 2014. The information came from the TruvenHealth MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database.

The data showed that orally administered drugs approved in 2000 cost an average of $1869 (95% CI, $1648-$2121) per month, compared to $11,325 (95% CI, $10 989-$11 671) for those approved in 2014.

When Dr Dusetzina compared changes in spending by year from a product’s launch to 2014, she observed increases in most of the drugs studied.

The drugs with the largest increases in monthly spending were thalidomide, which increased from $1869 to $7564 ($5695) and imatinib, which increased from $3346 to $8479 ($5133).

However, 2 drugs showed decreases in mean monthly spending between their launch and 2014. Monthly spending for lenalidomide decreased from $10,109 to $9640 ($469), and monthly spending for vorinostat decreased from $9755 to $7592 ($2163).

Dr Dusetzina pointed out that the amount patients pay for these drugs depends on their healthcare benefits. However, the high prices are being passed along to patients more and more, potentially affecting the patients’ access to these drugs.

“Patients are increasingly taking on the burden of paying for these high-cost specialty drugs as plans move toward use of higher deductibles and co-insurance—where a patient will pay a percentage of the drug cost rather than a flat copay,” Dr Dusetzina said.

She noted that while this study did account for payments by commercial health plans, it did not account for spending by Medicaid and Medicare, which may differ. In addition, only the products that were dispensed and reimbursed by commercial health plans were included, which may have excluded rarely used or recently approved products. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New orally administered cancer drugs are much more expensive in their first year on the market than such drugs launched about 15 years ago, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The research showed that a month of treatment with orally administered cancer drugs introduced in 2014 was, on average, 6 times more expensive at launch than monthly treatment costs for such drugs introduced in 2000, after adjusting for inflation.

In addition, most existing therapies had substantial price increases from the time they were launched to 2014.

“The major trend here is that these products are just getting more expensive over time,” said study author Stacie Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

For this study, Dr Dusetzina evaluated what commercial health insurance companies and patients paid for prescription fills—before rebates and discounts—for 32 orally administered cancer drugs from 2000 to 2014. The information came from the TruvenHealth MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database.

The data showed that orally administered drugs approved in 2000 cost an average of $1869 (95% CI, $1648-$2121) per month, compared to $11,325 (95% CI, $10 989-$11 671) for those approved in 2014.

When Dr Dusetzina compared changes in spending by year from a product’s launch to 2014, she observed increases in most of the drugs studied.

The drugs with the largest increases in monthly spending were thalidomide, which increased from $1869 to $7564 ($5695) and imatinib, which increased from $3346 to $8479 ($5133).

However, 2 drugs showed decreases in mean monthly spending between their launch and 2014. Monthly spending for lenalidomide decreased from $10,109 to $9640 ($469), and monthly spending for vorinostat decreased from $9755 to $7592 ($2163).

Dr Dusetzina pointed out that the amount patients pay for these drugs depends on their healthcare benefits. However, the high prices are being passed along to patients more and more, potentially affecting the patients’ access to these drugs.

“Patients are increasingly taking on the burden of paying for these high-cost specialty drugs as plans move toward use of higher deductibles and co-insurance—where a patient will pay a percentage of the drug cost rather than a flat copay,” Dr Dusetzina said.

She noted that while this study did account for payments by commercial health plans, it did not account for spending by Medicaid and Medicare, which may differ. In addition, only the products that were dispensed and reimbursed by commercial health plans were included, which may have excluded rarely used or recently approved products. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

New orally administered cancer drugs are much more expensive in their first year on the market than such drugs launched about 15 years ago, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

The research showed that a month of treatment with orally administered cancer drugs introduced in 2014 was, on average, 6 times more expensive at launch than monthly treatment costs for such drugs introduced in 2000, after adjusting for inflation.

In addition, most existing therapies had substantial price increases from the time they were launched to 2014.

“The major trend here is that these products are just getting more expensive over time,” said study author Stacie Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

For this study, Dr Dusetzina evaluated what commercial health insurance companies and patients paid for prescription fills—before rebates and discounts—for 32 orally administered cancer drugs from 2000 to 2014. The information came from the TruvenHealth MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database.

The data showed that orally administered drugs approved in 2000 cost an average of $1869 (95% CI, $1648-$2121) per month, compared to $11,325 (95% CI, $10 989-$11 671) for those approved in 2014.

When Dr Dusetzina compared changes in spending by year from a product’s launch to 2014, she observed increases in most of the drugs studied.

The drugs with the largest increases in monthly spending were thalidomide, which increased from $1869 to $7564 ($5695) and imatinib, which increased from $3346 to $8479 ($5133).

However, 2 drugs showed decreases in mean monthly spending between their launch and 2014. Monthly spending for lenalidomide decreased from $10,109 to $9640 ($469), and monthly spending for vorinostat decreased from $9755 to $7592 ($2163).

Dr Dusetzina pointed out that the amount patients pay for these drugs depends on their healthcare benefits. However, the high prices are being passed along to patients more and more, potentially affecting the patients’ access to these drugs.

“Patients are increasingly taking on the burden of paying for these high-cost specialty drugs as plans move toward use of higher deductibles and co-insurance—where a patient will pay a percentage of the drug cost rather than a flat copay,” Dr Dusetzina said.

She noted that while this study did account for payments by commercial health plans, it did not account for spending by Medicaid and Medicare, which may differ. In addition, only the products that were dispensed and reimbursed by commercial health plans were included, which may have excluded rarely used or recently approved products. ![]()

Agreement on Dyspnea Severity

Breathlessness, or dyspnea, is defined as a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that is comprised of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.[1] Dyspnea is a leading reason for patients presenting for emergency care,[2] and it is an important predictor for hospitalization and mortality in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.[3, 4, 5]

Several professional societies' guidelines recommend that patients should be asked to quantify the intensity of their breathlessness using a standardized scale, and that these ratings should be documented in medical records to guide dyspnea awareness and management.[1, 6, 7] During the evaluation and treatment of patients with acute cardiopulmonary conditions, the clinician estimates the severity of the illness and response to therapy based on multiple objective measures as well as the patient's perception of dyspnea. A patient‐centered care approach depends upon the physicians having a shared understanding of what the patient is experiencing. Without this appreciation, the healthcare provider cannot make appropriate treatment decisions to ensure alleviation of presenting symptoms. Understanding the severity of patients' dyspnea is critical to avoid under‐ or overtreatment of patients with acute cardiopulmonary conditions, but only a few studies have compared patient and provider perceptions of dyspnea intensity.[8, 9] Discordance between physician's impression of severity of dyspnea and patient's perception may result in suboptimal management and patient dissatisfaction with care. Furthermore, several studies have shown that, when physicians and patients agree with the assessment of well‐being, treatment adherence and outcomes improve.[10, 11]

Therefore, we evaluated the extent and directionality of agreement between patients' perception and healthcare providers' impression of dyspnea and explored which factors contribute to discordance. Additionally, we examined how healthcare providers document dyspnea severity.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

The study was conducted between June 2012 and August 2012 at Baystate Medical Center (BMC), a 740‐bed tertiary care hospital in western Massachusetts. In 2012, the BMC hospitalist group had 48 attending physicians, of whom 47% were female, 48% had 0 to 3 years of attending experience, and 16% had 10 years of experience.

We enrolled consecutive admissions of English‐speaking adult patients, with a working diagnosis of heart failure (HF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, pneumonia, or a generic diagnosis of shortness of breath. Because we surveyed only hospitalists, we did not include patients admitted to an intensive care unit.

All participants gave informed consent to be part of the study. The research protocol was approved by the Baystate Health Institutional Review Board, Springfield, Massachusetts.

Dyspnea Assessment

Dyspnea intensity was assessed on an 11‐point (010) numerical rating scale (NRS).[12, 13] A trained research assistant interviewed patients on day 1 and 2 after admission, and on the day of discharge between 8 am and 12 pm on weekdays. The patient was asked: On a scale from 0 to 10, how bad is your shortness of breath at rest now, with 0 being no shortness of breath and 10 the worst shortness of breath you could ever imagine? The hospitalist or the senior resident and day‐shift nurse taking care of the patients were asked by the research assistant to rate the patient's dyspnea using the same scoring instrument shortly after they saw the patient. The physicians and nurses based their determination of dyspnea on their usual interview/examination of the patient. The patient, physician and the nurse were not aware of each other's rating. The research assistant scheduled the interviews to minimize the time intervals between the patient assessment and provider's rating. For this reason, the number of assessments per patient varied. Nurses were more readily available than physicians, which resulted in a larger number of patient‐nurse response pairs than patient‐physician pairs. All assessments were done in the morning, between 9 am and 12 pm, with a range of 3 hours between provider's assessment of the patient and the interview.

Dyspnea Agreement

Agreement was defined as a score within 1 between patient and healthcare provider; differences of 2 points were considered over‐ or underestimations. The decision to use this cutoff was based on prior studies, which found that a difference in the range of 1.6 to 2.2 cm was meaningful for the patient when assessment was done on the visual analog scale.[8, 14, 15] We also evaluated the direction of discordance. If the patient's rating of dyspnea severity was higher than the provider's rating, we defined this as underestimation by the provider; in the instance where a provider's score of dyspnea severity was higher than the patient's score, we defined this as overestimation. In a sensitivity analysis, agreement was defined as a score within 2 between patient and healthcare provider, and any difference 3 was considered disagreement.

Other Variables

We obtained information from the medical records about patient demographics, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, and vital signs. We calculated the oxygen saturation index as the ratio between the oxygen saturation and the fractional inspired oxygen (SpO2/FIO2). Comorbidities were assessed based on the International Classification od Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes from the hospital financial decision support system. We calculated an overall combined comorbidity score based on the method described by Gagne, which is based on elements from the Charlson Comorbidity Index and from the Elixhauser comorbidities.[16]

Charts of the patients included in the study were retrospectively reviewed for physicians' and nurses' documentation of dyspnea at admission and at discharge. We recorded if dyspnea was mentioned and how it was assessed: whether it was described as present/absent; graded as mild, moderate, or severe; used a quantitative scale (010); used descriptors (eg, dyspnea when climbing stairs); and whether it was defined as improved or worsened without other qualifiers.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of dyspnea scores, patient characteristics, comorbidities and vital signs were calculated and presented as medians with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and counts with percentages for categorical factors. Every patient‐provider concurrent scoring was included in the analysis as 1 dyad, which resulted in patients being included multiple times in the analysis. Patient‐physician and patient‐nurse dyads of dyspnea assessment were examined separately. Analyses included all dyads that were within same assessment period (same day and same time window).

The relationship between patient self‐perceived dyspnea severity and provider rating of was assessed in several ways. First, a weighted kappa coefficient was used as a measure of agreement between patient and nurse or physician scores. A weighted kappa analysis was chosen because it penalizes disagreements that are further apart from each other.

Second, we defined an indicator of discordance and constructed multivariable generalized estimating equation models that account for clustering of multiple dyads per patient, to assess the relationship of patient characteristics with discordance. Finally, we developed additional models to predict underestimation when compared to agreement or overestimation of dyspnea by the healthcare provider relative to the patient. Using the same definitions for agreement, we also compared the dyspnea assessment estimation between physicians and nurses.

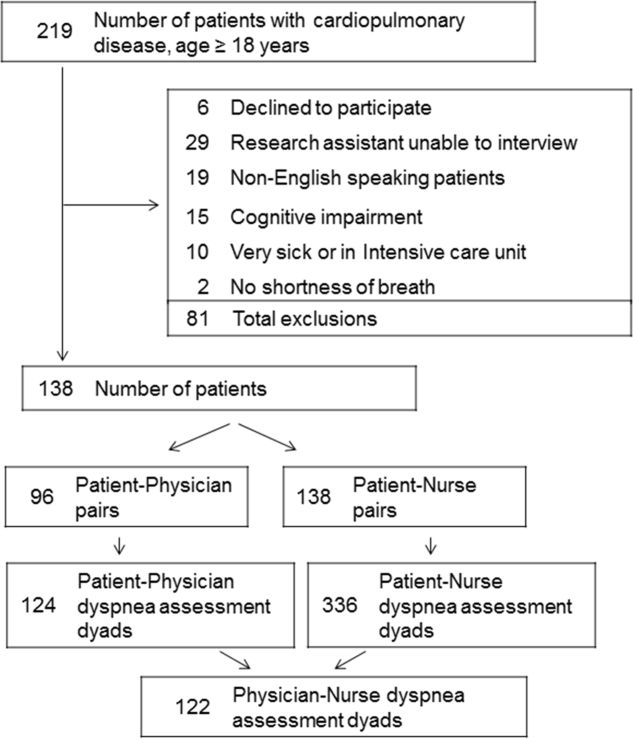

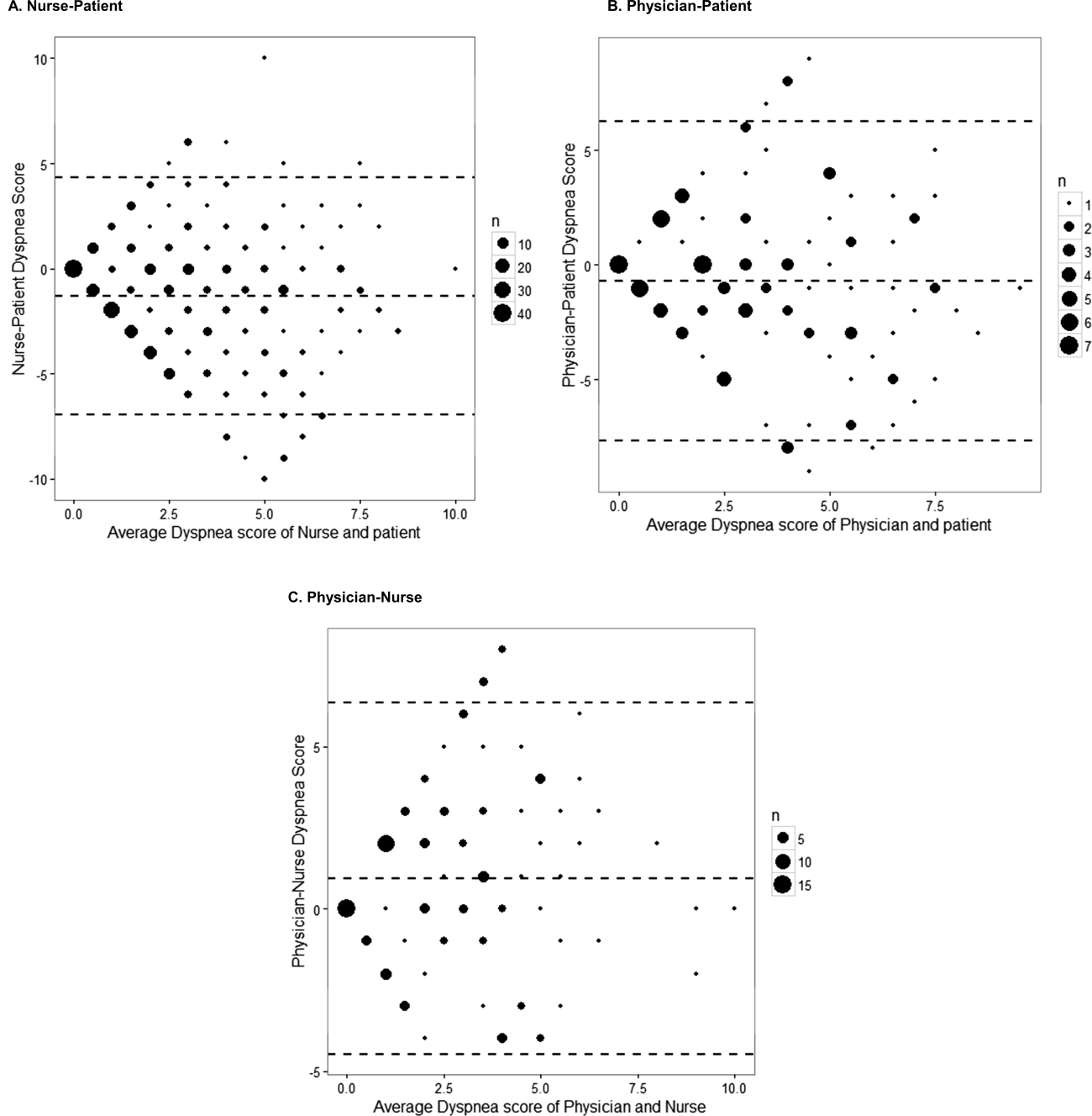

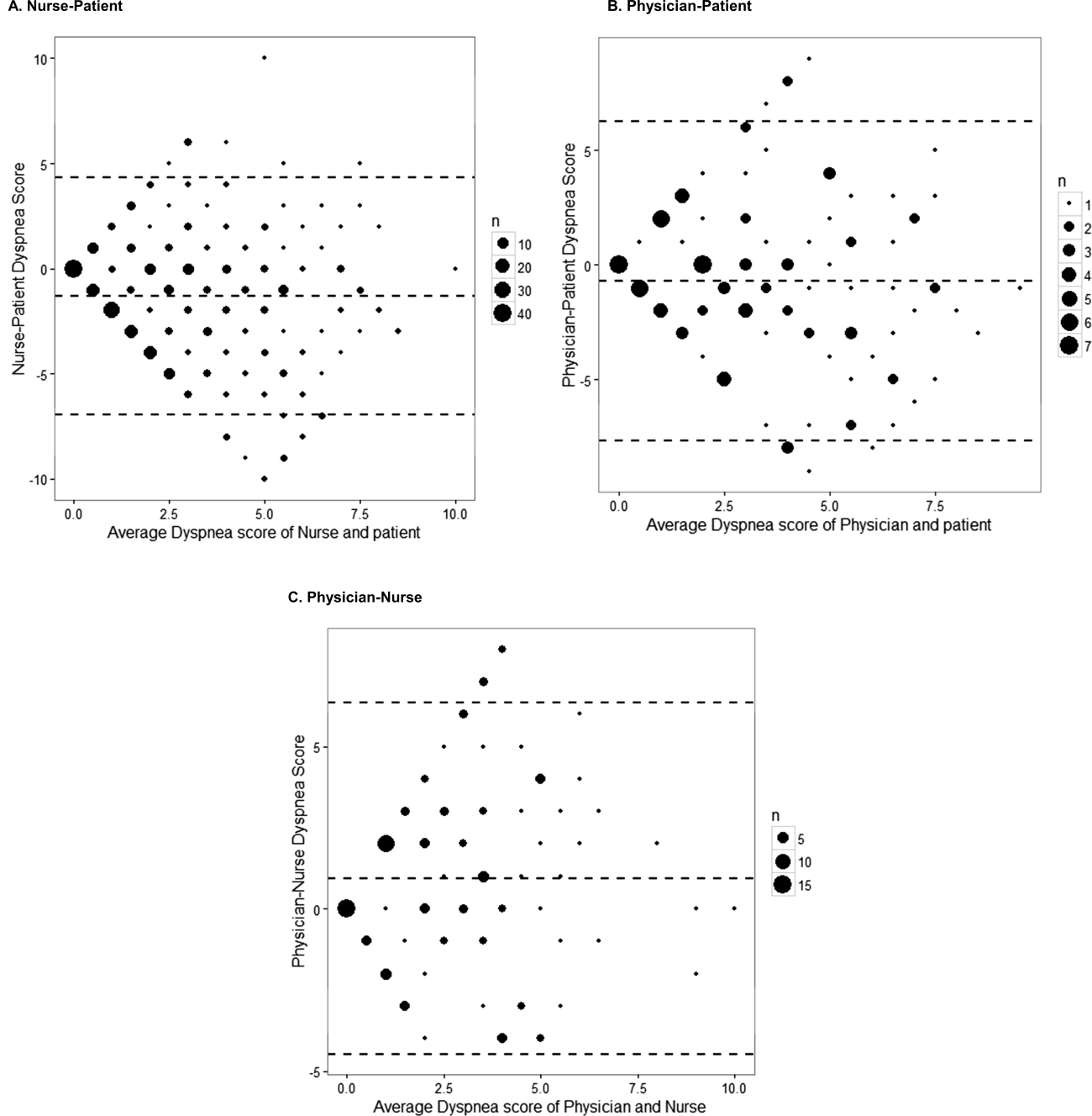

We present the differences in dyspnea assessment between patient and healthcare provider and between nurses and physicians by Bland‐Altman plots.

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS institute, Inc., Cary, NC), Stata (Stata statistical software release 13; StataCorp, College Station, TX), and RStudio version 0.99.892 (Bland‐Altman plots, R package version 0.3.1; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).[8, 9, 17]

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

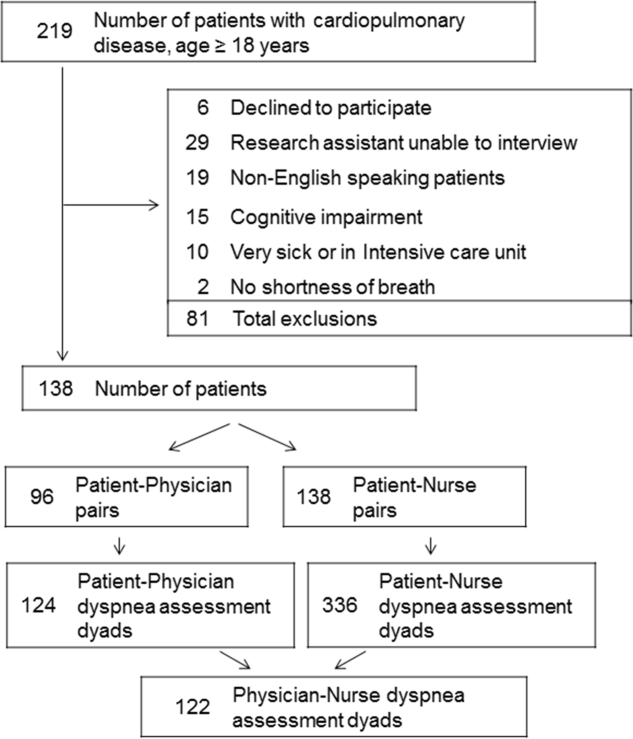

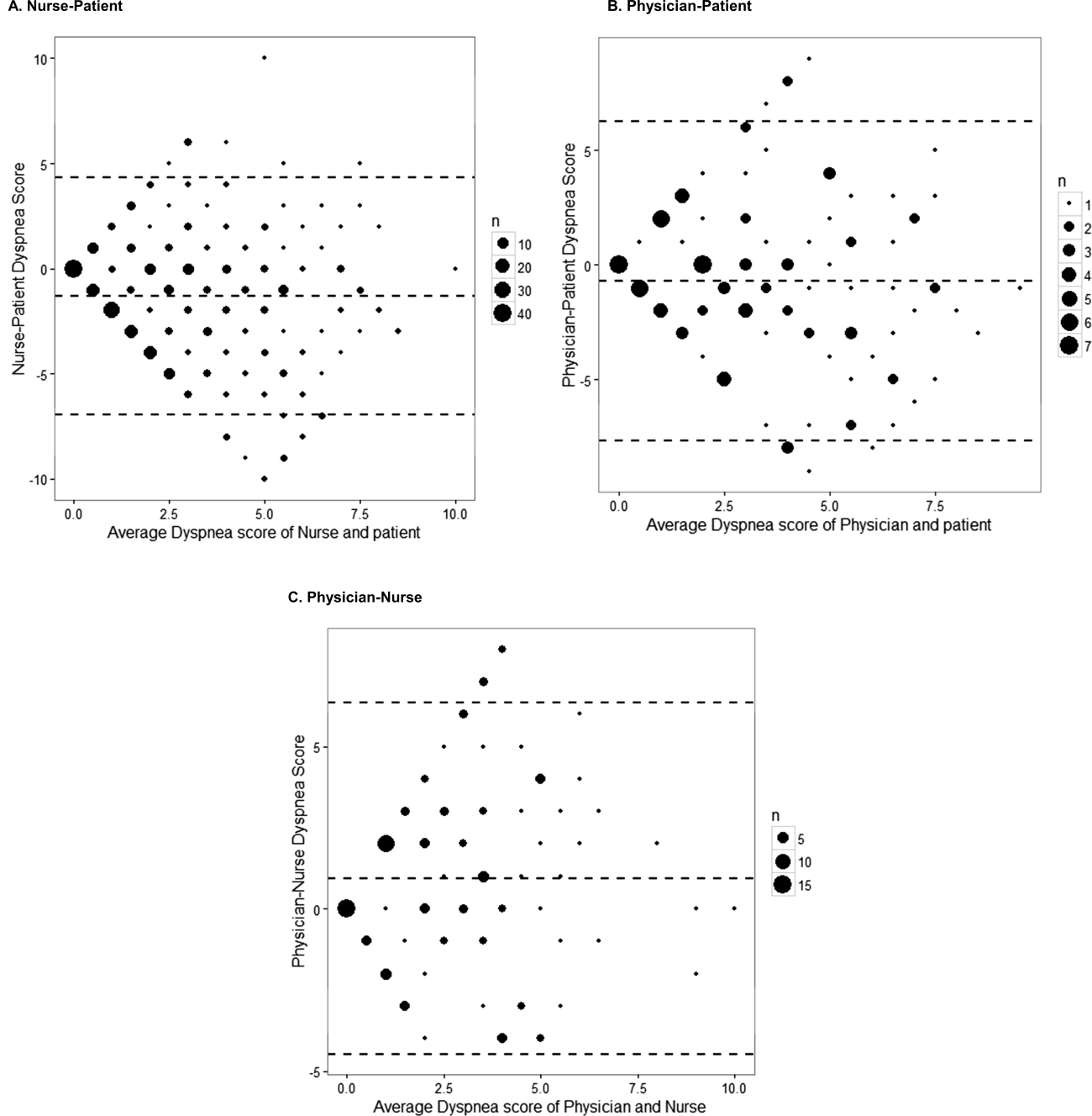

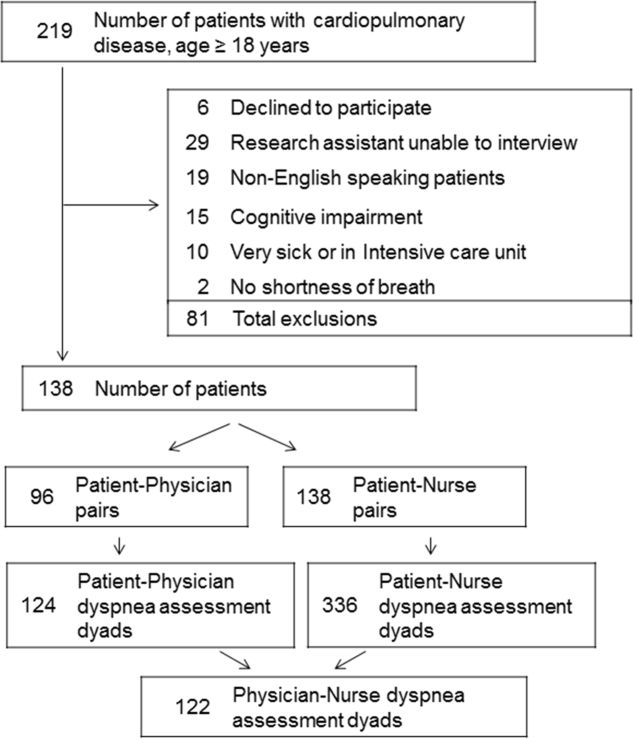

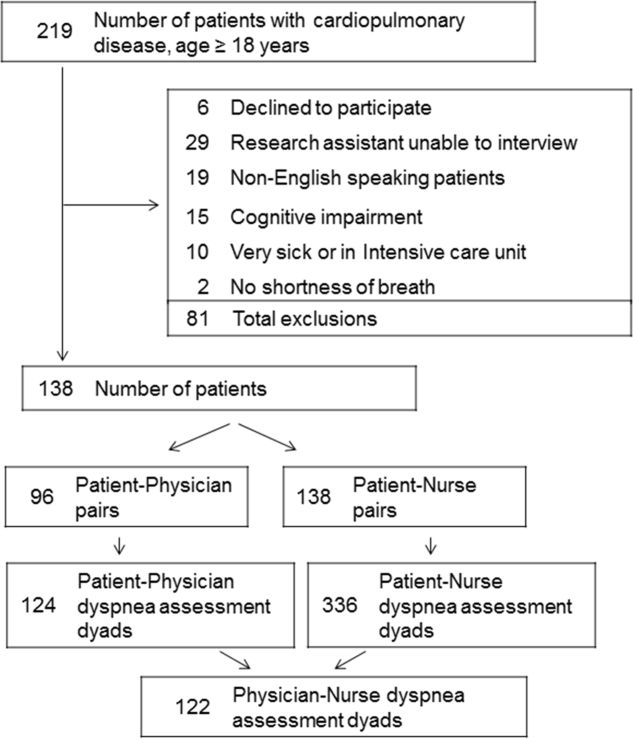

Among the 219 patients who met the screening criteria, 81 were not enrolled (Figure 1). Data from 138 patients, with both patient information and provider data on dyspnea assessment, were included. The median age of the patients was 72 years (IQR, 5880 years), 56.5% were women, 75.4% were white, and 28.3% were current smokers. Approximately 30% had a diagnosis of HF, 30% of COPD, and 13.0% of pneumonia. The median comorbidity score was 4 (IQR, 26), and 37.0% of the patients had a BMI 30. At admission, the median oxygen saturation index was 346 (IQR, 287.5460) indicating mild to moderate levels of hypoxia. (Table 1).

| Value | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 72 (5880) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 78 (56.5) |

| Male | 60 (43.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 104 (75.4) |

| Black | 16 (11.6) |

| Hispanic | 17 (12.3) |

| Other | 1 (0.7) |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 28 (23.334.6) |

| Obese (BMI 30) | 51 (37.0) |

| Smoker, current | 39 (28.3) |

| Admitting diagnosis | |

| Heart failure | 46 (33.3) |

| COPD/asthma | 41 (29.7) |

| Pneumonia | 18 (13.0) |

| Other | 33 (23.9) |

| Depression | 32 (23.2) |

| Comorbidity score, median (IQR) | 4 (26) |

| Respiratory rate at admission, median (IQR) | 20 (1924) |

| Oxygen saturation index at admission, median (IQR) | 346.4 (287.5460) |

| Patient NRS, median (IQR) | |

| At admission | 9 (710) |

| At discharge | 2 (14) |

| Discharged on home oxygen | 45 (32.6) |

| Respiratory rate at discharge, median (IQR) | 20 (1820) |

| Oxygen saturation index at discharge, median (IQR) | 475 (350485) |

Agreement Between Patients' Self‐Assessment and Providers' Assessment of Dyspnea Severity

Not all patients had complete data points, and more nurses were interviewed than physicians. Overall, 96 patient‐physician and 138 patient‐nurse pairs participated in the study. A total of 336 patient‐nurse rating dyad assessments of dyspnea and 124 patient‐physician rating dyads assessments were collected (Figure 1). The mean difference between patient and physicians and patient and nurses assessments of dyspnea was 1.23 (IQR, 3 to 0) and 0.21 (IQR, 2 to 2) respectively (a negative score means underestimation by the provider, a positive score means overestimation).

The unadjusted agreement on the severity of dyspnea was 36.3% for the patient‐physician dyads and 44.1% for the patient‐nurse dyads. Physicians underestimated their patients' dyspnea 37.9% of the time and overestimated it 25.8% of the time; nurses underestimated it 43.5% of the time and overestimated it in 12.4% of the study patients (Table 2). In 28.2% of the time, physicians were discordant more than 4 points of the patient assessment. Bland‐Altman plots show that there is greater variation in differences of dyspnea assessments with increase in shortness of breath scores (Figure 2). Nurses underestimated more when the dyspnea score was on the lower end. Physicians also tended to estimate either lower or higher when compared to patients when the dyspnea scores were 2 (Figure 2A,B).

| Underestimation | Concordance | Overestimation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2 | %* | 0 | 1 | % | 2 | 3 | % | |

| |||||||||

| Patient‐nurse dyads | 110 | 48 | 43.5 | 82 | 78 | 44.1 | 17 | 28 | 12.4 |

| Patient‐physician dyads | 33 | 14 | 37.9 | 21 | 24 | 36.3 | 12 | 20 | 25.8 |

The weighted kappa coefficient for agreement was 0.11 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01 to 0.21) for patient‐physician assessment, 0.18 (95% CI: 0.12 to 0.24) for patient‐nurse, and 0.09 (0.02 to 0.20) for physician‐nurse indicating poor agreement. In a sensitivity analysis in which we used a higher threshold for defining discordance (difference of more than 2 points), the kappa coefficient increased to 0.21 (95% CI: 0.06 to 0.36) for patient‐physician assessments, to 0.24 (95% CI: 0.15 to 0.33) for patient‐nurse, and to 0.24 (95% CI: 0.09 to 0.39) for nurse‐physician assessments.

Predictors of Discordance and Underestimation of Dyspnea Severity Assessment

Principal diagnosis was the only factor associated with the physicians' discordant assessment of patients' dyspnea. Patients with admission diagnoses other than HF, COPD, or pneumonia (eg, pulmonary embolism) were more likely to have an accurate assessment of their dyspnea by providers (Table 3). Similar results were obtained in the sensitivity analysis by using a higher cutoff for defining discordance and when assessing predictors for underestimation (results not shown).

| Modeling Probability of Discordance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Physician‐Patient Dyads, OR (95% CI), N = 124 | Nurse‐Patient Dyads, OR (95% CI), N = 363 | |

| ||

| Univariate Analysis | ||

| Body mass index | 1.00 (0.991.01) | 1.00 (0.991.00) |

| Comorbidity score | 1.01 (0.981.05) | 0.99 (0.961.01) |

| Respiratory rate at admission | 1.00 (0.991.02) | 0.99 (0.981.00) |

| Oxygen saturation at admission | 1.00 (1.001.00) | 1.00 (1.001.00) |

| Age (binary) | ||

| 65 years | Referent | Referent |

| >65 years | 1.21 (0.572.55) | 0.96 (0.571.64) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | Referent | Referent |

| Male | 1.10 (0.522.32) | 0.81 (0.481.37) |

| Race | ||

| White | Referent | Referent |

| Nonwhite | 1.02 (0.442.37) | 1.06 (0.581.95) |

| Obese (BMI >30) | 1.43 (0.663.11) | 0.76 (0.441.30) |

| Smoker | 1.36 (0.613.05) | 1.04 (0.591.85) |

| Admitting diagnosis | ||

| Heart failure | Referent | Referent |

| COPD/asthma | 0.68 (0.251.83) | 1.91 (0.983.73)* |

| Pneumonia | 0.38 (0.101.40) | 1.07 (0.462.45) |

| Other | 0.30 (0.110.82)* | 1.54 (0.763.11) |

| Depression | 1.21 (0.572.55) | 1.01 (0.541.86) |

| Multivariable analysis | ||

| Admitting diagnosis | ||

| Congestive heart failure | Referent | Referent |

| COPD | 0.68 (0.251.83) | 1.91 (0.983.73)* |

| Pneumonia | 0.38 (0.101.40) | 1.07 (0.462.45) |

| Other | 0.30 (0.110.82)* | 1.54 (0.763.11) |

In the multivariable analysis that assessed patient‐nurse dyads, the diagnosis of COPD was associated with a marginally significant likelihood of discordance (OR: 1.91; 95% CI: 0.98 to 3.73) (Table 3). Similarly, multivariable analysis identified principal diagnosis to be the only predictor of underestimation, and COPD diagnosis was associated with increased odds of dyspnea underestimation by nurses. When we used a higher cutoff to define discordance, the principal diagnosis of COPD (OR: 3.43, 95% CI: 1.76 to 6.69) was associated with an increased risk of discordance, and smoking (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.99) was associated with a decreased risk of discordance. Overall, 45 patients (32.6%) were discharged on oxygen. The odds of discrepancy (under‐ or overestimation) in dyspnea scores between patient and nurse were 1.7 times higher compared to patients who were not discharged on oxygen, but this association did not reach statistical significance; the odds of discrepancy between patient and physician were 3.88 (95% CI: 1.07 to 14.13).

Documentation of Dyspnea

We found that dyspnea was mentioned in the admission notes in 96% of the charts reviewed; physicians used a qualitative rating (mild, moderate, or severe) to indicate the severity of dyspnea in only 16% of cases, and in 53% a descriptor was added (eg, dyspnea with climbing stairs, gradually increased in the prior week). Nurses were more likely than physicians to use qualitative ratings of dyspnea (26% of cases), and they used a more uniform description of the patient's dyspnea (eg, at rest, at rest and on exertion, or on exertion) than physicians. At discharge, 83% of physicians noted in their discharge summary that dyspnea improved compared with admission but did not refer to the patient's baseline level of dyspnea.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of 138 patients hospitalized with cardiopulmonary disease, we found that the agreement between patient's experience of dyspnea and providers' assessment was poor, and the discordance was higher for physicians than for nurses. In more than half of the cases, differences between patient and healthcare providers' assessment of dyspnea were present. One‐third of the time, both physicians and nurses underestimated patients' reported levels of dyspnea. Admitting diagnosis was the only patient factor predicting lack of agreement, and patients with COPD were more likely to have their dyspnea underestimated by nurses. Healthcare providers predominantly documented the presence or absence of dyspnea and rarely used a more nuanced scale.

Discrepancies between patient and provider assessments for pain, depression, and overall health have been reported.[8, 18, 19, 20, 21] One explanation is that patients and healthcare providers measure different factors despite using the same terminology. Furthermore, patient's assessment may be confounded by other symptoms such as anxiety, fatigue, or pain. Physicians and nurses may underevaluate and underestimate the level of breathlessness; however, from the physician perspective, dyspnea is only 1 data point, and providers rely on other measures, such as oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate, evidence of increasing breathing effort, and arterial blood gas to drive decision making. In a recent study that evaluated the attitudes and beliefs of hospitalists regarding the assessment and management of dyspnea, we found that most hospitalists indicated that awareness of dyspnea severity influences their decision for treatment, diagnostic testing, and timing of the discharge. Moreover, whereas less than half of the respondents reported experience with standardized assessment of dyspnea severity, most stated that such data would be very useful in their practice.[22]

What is the clinical significance of having discordance between patients self‐assessment and providers impression of the patient's severity of dyspnea? First, inaccurate assessment of dyspnea by providers can lead to inadequate treatment and workup. For example, a physician who underestimates the severity of dyspnea may fail to recognize when a complication of the underlying disease develops or may underutilize symptomatic methods for relief of dyspnea. In contrast, a physician who overestimates dyspnea may continue with aggressive treatment when this is not necessary. Second, lack of awareness of dyspnea severity experienced by the patient may result in premature discharge and patient's frustration with the provider, as was shown in several studies evaluating physician‐patient agreement for pain perception.[21, 23] We found that discrepancy between patients and healthcare providers was more pronounced for patients with COPD. In another study using the same patient cohort, we reported that compared to patients with congestive heart failure, those with COPD had more residual dyspnea at discharge; 1 in 4 patients was discharged with a dyspnea score of 5 of greater, and almost half reported symptoms above their baseline.[24] The results from the current study may explain in part why patients with COPD are discharged with higher levels of dyspnea and should alert healthcare providers on the importance of patient‐reported breathlessness. Third, the high level of discordance between healthcare providers and patients may explain the undertreatment of dyspnea in patients with advanced disease. This is supported by our findings that the discordance between patients and physicians was higher if the patient was discharged on oxygen.

One key role of the provider during a clinical encounter is to elicit the patient's symptoms and achieve a shared understanding of what the patient is experiencing. From the patient's perspective, their self‐assessment of dyspnea is more important that the physician's assessment. Fortunately, there is a growing recognition and emphasis on using outcomes that matter to patients, such as dyspnea, to inform judgment about patient care and for clinical research. Numerical measures for assessment of dyspnea exist, are easy to use, and are sensitive to change in patients' dyspnea.[6, 25, 26, 27] Still, it is not standard practice for healthcare providers to ask patients to provide a rating of their dyspnea. When we examined the documentation of dyspnea in the medical record, we found that the description was vague, and providers did not use a standardized validated assessment. Although the dyspnea score decreased during hospitalization, the respiratory rate did not significantly change, indicating that this objective measure may not be reliable in patient assessment. The providers' knowledge of the intensity of the symptom expressed by patients will enable them to track improvement in symptoms over time or in response to therapy. In addition, in this era of multiple handoffs within a hospitalization or from primary care to the hospital, a more uniform assessment could allow providers to follow the severity and time course of dyspnea. The low level of agreement we found between patients and the providers lends support to recommendations regarding a structured dyspnea assessment into routine hospital practice.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. This is 1 of the very few studies to report on the level of agreement between patients' and providers' assessments of dyspnea. We used a validated, simple dyspnea scale that provides consistency in rating.[28, 29] We enrolled patients with a broad set of diagnoses and complaints, which increases the generalizability of our results, and we surveyed both physicians and nurses. Last, our findings were robust across different cutoff points utilized to characterize discordance and across 3 frequent diagnoses.

The study has several limitations. First, we included only English‐speaking patients, and the results cannot be generalized to patients from other cultures who do not speak English. Second, this is a single‐center study, and practices may be different in other centers; for example, some hospitals may have already implemented a dyspnea assessment tool. Third, we did not collect information on the physician and nurse characteristics such as years in practice. However, a recent study that describes the agreement of breathlessness assessment between nurses, physicians, and mechanically ventilated patients found that underestimation of breathlessness by providers was not associated with professional competencies, previous patient care, or years of working in an intensive care unit.[9] In addition, a systematic review found that length of professional experience is often unrelated to performance measures and outcomes.[30] Finally, although we asked for physicians and nurses assessment close to their visit to the patient, assessment was done from memory, not at the bedside observing the patient.

CONCLUSION

We found that the extent of agreement between a structured patient self‐assessment of dyspnea and healthcare providers' assessment was low. Future studies should prospectively test whether routine assessment of dyspnea results in better acute and long‐term patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Ms. Anu Joshi for her help with formatting the manuscript and assisting with table preparations. The authors also acknowledge Ms. Katherine Dempsey, Jahnavi Sagi, Sashi Ariyaratne, and Mr. Pradeep Kumbaham for their help with collecting the data.

Disclosures: M.S.S. is the guarantor for this article and had full access to all of the data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. M.S.S., P.K.L., E.N., and M.B.R. conceived of the study. M.S.S. and B.M. acquired the data. M.S.S., A.P., P.S.P., R.J.G., and P.K.L. analyzed and interpreted the data. M.S.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. M.S.S. is supported by grant 1K01HL114631‐01A1 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health and by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant UL1RR025752. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(4):435–452.

- , , . National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;(26):1–31.

- , , , et al. The body‐mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(10):1005–1012.

- , , , . Dyspnea is a better predictor of 5‐year survival than airway obstruction in patients with COPD. Chest. 2002;121(5):1434–1440.

- , , . A multidimensional grading system (BODE index) as predictor of hospitalization for COPD. Chest. 2005;128(6):3810–3816.

- , , , et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 2010;137(3):674–691.

- , , , et al. Managing dyspnea in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Canadian Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Can Respir J. 2011;18(2):69–78.

- , , . Physician vs patient assessment of dyspnea during acute decompensated heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(2):60–64.

- , , , , , . Underestimation of Patient Breathlessness by Nurses and Physicians during a Spontaneous Breathing Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(12):1440–1448.

- , , , , , . The influence of patient‐practitioner agreement on outcome of care. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(2):127–131.

- , , , , , . Listening to parents: The role of symptom perception in pediatric palliative home care. Palliat Support Care. 2016;14(1):13–19.

- , . Validity of the numeric rating scale as a measure of dyspnea. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7(3):200–204.

- , , , , , . Dyspnea scales in the assessment of illiterate patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med Sci. 2000;320(4):240–243.

- , , , , . Measuring the dyspnea of decompensated heart failure with a visual analog scale: how much improvement is meaningful? Congest Heart Fail. 2004;10(4):188–191.

- , , , , , . Clinically meaningful changes in quantitative measures of asthma severity. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(4):327–334.

- , , , , . A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749–759.

- . BlandAltmanLeh: plots (slightly extended) Bland‐Altman plots. Available at: https://cran.r‐project.org/web/packages/BlandAltmanLeh/index.html. Published December 23, 2015. Accessed March 10, 2016.

- , , , , . Correlation of patient and caregiver ratings of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6(2):53–57.

- , , , et al. Depression symptomatology and diagnosis: discordance between patients and physicians in primary care settings. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:1.

- , , , , , . Patient‐physician discordance in assessments of global disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(6):857–864.

- , , , et al. The influence of discordance in pain assessment on the functional status of patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332(1):18–23.

- , , , et al. Hospitalist attitudes toward the assessment and management of dyspnea in patients with acute cardiopulmonary diseases. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):724–730.

- , , , , . Brief report: patient‐physician agreement as a predictor of outcomes in patients with back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):935–937.

- , , , , , . The trajectory of dyspnea in hospitalized patients [published online November 24, 2015]. J Pain Symptom Manage. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.005.

- , , , , . Measurement of breathlessness in advanced disease: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2007;101(3):399–410.

- . Review of dyspnoea quantification in the emergency department: is a rating scale for breathlessness suitable for use as an admission prediction tool? Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19(5):394–404.

- , , , . Validation of a verbal dyspnoea rating scale in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20(6):475–481.

- , , . Measurement of dyspnea: word labeled visual analog scale vs. verbal ordinal scale. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;134(2):77–83.

- , , , , , . Verbal numerical scales are as reliable and sensitive as visual analog scales for rating dyspnea in young and older subjects. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;157(2–3):360–365.

- , , . Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260–273.

Breathlessness, or dyspnea, is defined as a subjective experience of breathing discomfort that is comprised of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.[1] Dyspnea is a leading reason for patients presenting for emergency care,[2] and it is an important predictor for hospitalization and mortality in patients with cardiopulmonary disease.[3, 4, 5]