User login

Plasma microRNA assay differentiates colorectal neoplasia

CHICAGO – A novel plasma microRNA assay and prediction model appears to successfully differentiate colorectal neoplasia from other neoplasms and from controls.

The assay includes seven microRNAs that were selected, based on P value, area under the curve (AUC), fold change, and biological plausibility, from among 380 microRNAs screened using microfluidic array technology from a “training” cohort of 60 patients. The training cohort included groups of patients, 10 each, with colorectal cancer, advanced adenoma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer – cancers chosen because they frequently develop at similar ages as colon cancer – and 10 controls.

A panel of seven “uniquely dysregulated” microRNAs specific for colorectal neoplasia was evaluated using single assays in a “test” cohort of 120 patients. A mathematical model was developed to predict sample identity in a 150-patient blinded “validation” cohort using repeat-subsampling validation of the testing dataset with 1,000 iterations each to assess model detection accuracy, Dr. Jane V. Carter of the University of Louisville (Ky.) explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The area under the curve for test cohort comparisons with the assay was 0.91, 0.79, and 0.98 for comparison No. 1 (comparing any neoplasia vs. controls), comparison No. 2 (comparing colorectal neoplasia with other cancers) and comparison No. 3 (comparing colorectal cancer with colorectal adenomas) respectively, Dr. Carter reported.

“Our prediction model identified blinded sample identity with 69%-77% accuracy in comparison No. 1, 66%-76% accuracy in comparison No. 2, and 86%-90% accuracy in comparison No. 3,” she said, noting that the sensitivity and specificity of the assay compare very well with current clinical standards.

Colorectal neoplasms frequently develop in individuals at ages when other common cancers also occur. Current screening methods, including endoscopic and imaging studies and fecal testing have poor patient compliance. Fecal and blood tests lack sensitivity and specificity for the detection of adenomas, limiting their use as screening methods, she said.

But this novel assay, which builds on the earlier work identifying miR-21 as a potential marker for colorectal cancer, provides a useful tool for identifying colorectal neoplasms, she said.

Efforts are underway to confirm the findings in a larger study population. If the findings are confirmed, the assay may have other potential uses such as monitoring therapy by comparing microRNA expression before and after treatment, and also for predicting response to treatment such as following preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiation, Dr. Carter suggested.

The current findings have significant implications for the development of a noninvasive, reliable, and reproducible screening test for detection of colorectal neoplasia.

“If we can improve early-stage detection, we can improve survival,” she said.

Dr. Carter reported having no relevant disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – A novel plasma microRNA assay and prediction model appears to successfully differentiate colorectal neoplasia from other neoplasms and from controls.

The assay includes seven microRNAs that were selected, based on P value, area under the curve (AUC), fold change, and biological plausibility, from among 380 microRNAs screened using microfluidic array technology from a “training” cohort of 60 patients. The training cohort included groups of patients, 10 each, with colorectal cancer, advanced adenoma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer – cancers chosen because they frequently develop at similar ages as colon cancer – and 10 controls.

A panel of seven “uniquely dysregulated” microRNAs specific for colorectal neoplasia was evaluated using single assays in a “test” cohort of 120 patients. A mathematical model was developed to predict sample identity in a 150-patient blinded “validation” cohort using repeat-subsampling validation of the testing dataset with 1,000 iterations each to assess model detection accuracy, Dr. Jane V. Carter of the University of Louisville (Ky.) explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The area under the curve for test cohort comparisons with the assay was 0.91, 0.79, and 0.98 for comparison No. 1 (comparing any neoplasia vs. controls), comparison No. 2 (comparing colorectal neoplasia with other cancers) and comparison No. 3 (comparing colorectal cancer with colorectal adenomas) respectively, Dr. Carter reported.

“Our prediction model identified blinded sample identity with 69%-77% accuracy in comparison No. 1, 66%-76% accuracy in comparison No. 2, and 86%-90% accuracy in comparison No. 3,” she said, noting that the sensitivity and specificity of the assay compare very well with current clinical standards.

Colorectal neoplasms frequently develop in individuals at ages when other common cancers also occur. Current screening methods, including endoscopic and imaging studies and fecal testing have poor patient compliance. Fecal and blood tests lack sensitivity and specificity for the detection of adenomas, limiting their use as screening methods, she said.

But this novel assay, which builds on the earlier work identifying miR-21 as a potential marker for colorectal cancer, provides a useful tool for identifying colorectal neoplasms, she said.

Efforts are underway to confirm the findings in a larger study population. If the findings are confirmed, the assay may have other potential uses such as monitoring therapy by comparing microRNA expression before and after treatment, and also for predicting response to treatment such as following preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiation, Dr. Carter suggested.

The current findings have significant implications for the development of a noninvasive, reliable, and reproducible screening test for detection of colorectal neoplasia.

“If we can improve early-stage detection, we can improve survival,” she said.

Dr. Carter reported having no relevant disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – A novel plasma microRNA assay and prediction model appears to successfully differentiate colorectal neoplasia from other neoplasms and from controls.

The assay includes seven microRNAs that were selected, based on P value, area under the curve (AUC), fold change, and biological plausibility, from among 380 microRNAs screened using microfluidic array technology from a “training” cohort of 60 patients. The training cohort included groups of patients, 10 each, with colorectal cancer, advanced adenoma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and lung cancer – cancers chosen because they frequently develop at similar ages as colon cancer – and 10 controls.

A panel of seven “uniquely dysregulated” microRNAs specific for colorectal neoplasia was evaluated using single assays in a “test” cohort of 120 patients. A mathematical model was developed to predict sample identity in a 150-patient blinded “validation” cohort using repeat-subsampling validation of the testing dataset with 1,000 iterations each to assess model detection accuracy, Dr. Jane V. Carter of the University of Louisville (Ky.) explained at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

The area under the curve for test cohort comparisons with the assay was 0.91, 0.79, and 0.98 for comparison No. 1 (comparing any neoplasia vs. controls), comparison No. 2 (comparing colorectal neoplasia with other cancers) and comparison No. 3 (comparing colorectal cancer with colorectal adenomas) respectively, Dr. Carter reported.

“Our prediction model identified blinded sample identity with 69%-77% accuracy in comparison No. 1, 66%-76% accuracy in comparison No. 2, and 86%-90% accuracy in comparison No. 3,” she said, noting that the sensitivity and specificity of the assay compare very well with current clinical standards.

Colorectal neoplasms frequently develop in individuals at ages when other common cancers also occur. Current screening methods, including endoscopic and imaging studies and fecal testing have poor patient compliance. Fecal and blood tests lack sensitivity and specificity for the detection of adenomas, limiting their use as screening methods, she said.

But this novel assay, which builds on the earlier work identifying miR-21 as a potential marker for colorectal cancer, provides a useful tool for identifying colorectal neoplasms, she said.

Efforts are underway to confirm the findings in a larger study population. If the findings are confirmed, the assay may have other potential uses such as monitoring therapy by comparing microRNA expression before and after treatment, and also for predicting response to treatment such as following preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiation, Dr. Carter suggested.

The current findings have significant implications for the development of a noninvasive, reliable, and reproducible screening test for detection of colorectal neoplasia.

“If we can improve early-stage detection, we can improve survival,” she said.

Dr. Carter reported having no relevant disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: A novel plasma microRNA assay and prediction model appears to successfully differentiate colorectal neoplasia from other neoplasms and from controls.

Major finding: The prediction model identified sample identity with 69%-77% accuracy when comparing any neoplasia vs. controls, 66%-76% accuracy when comparing colorectal neoplasia with other cancers, and 86%-90% accuracy when comparing colorectal cancer with colorectal adenomas.

Data source: A prediction model used in a 60-person training cohort, a 120-person testing cohort, and a 150-person validation cohort.

Disclosures: Dr. Carter reported having no relevant disclosures.

Smoking gun: DNA methylation in prostate cancer

More reason, if any is needed, to encourage patients to kick the habit comes from a study showing an association between cigarette smoking and tumor DNA methylation changes.

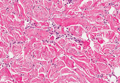

In a study of tumor tissue from men with prostate cancer (PCa) who underwent radical prostatectomy, smoking was associated with differential methylation across 40 genetic regions, and at least 10 of the regions significantly correlated with levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in corresponding genes.

Men whose tumors had the highest levels of smoking-associated methylation were more likely to have higher Gleason grade tumors or regional vs. local stage disease, reported Dr. Irene M. Shui of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and her colleagues.

“[O]ur results provide support for the hypothesis that smoking-induced changes in DNA methylation may underlie the association of smoking with PCa recurrence and mortality,” they wrote (Cancer 2016 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30045).

To see whether DNA methylation could at least partly explain the association of smoking with increased PCa progression and mortality, the investigators looked at tumor methylation and long-term follow-up data on 523 patients, 469 of whom (90%) had matched tumor gene expression data available. In all, 43% of the men were never smokers, 47% were former smokers, and 10% were current smokers.

The investigators examined tumor methylation profiles by smoking status, with the goals of determining whether smoking-associated changes in methylation are linked to mRNA expression, and whether they are related to disease prognosis.

They found that 40 DNA methylation regions were associated with smoking, and that 10 of the regions were strongly correlated with mRNA expression. They then used these 10 regions to create a smoking-related methylation score.

As noted before, the score was associated with adverse outcomes, with men in the highest third having an odds ratio (OR) for disease recurrence of 2.29 (P = .0007), and an OR of 4.21 for death from prostate cancer (P = .004)

The associations between smoking-related methylation scores and worse outcomes were slightly less strong but still significant after adjustment for Gleason score and pathologic stage.

“Importantly, there is evidence that smoking-related methylation changes in blood may be reversible; men who quit smoking for longer periods of time have methylation profiles similar to those of never-smokers,” the authors wrote.

More reason, if any is needed, to encourage patients to kick the habit comes from a study showing an association between cigarette smoking and tumor DNA methylation changes.

In a study of tumor tissue from men with prostate cancer (PCa) who underwent radical prostatectomy, smoking was associated with differential methylation across 40 genetic regions, and at least 10 of the regions significantly correlated with levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in corresponding genes.

Men whose tumors had the highest levels of smoking-associated methylation were more likely to have higher Gleason grade tumors or regional vs. local stage disease, reported Dr. Irene M. Shui of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and her colleagues.

“[O]ur results provide support for the hypothesis that smoking-induced changes in DNA methylation may underlie the association of smoking with PCa recurrence and mortality,” they wrote (Cancer 2016 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30045).

To see whether DNA methylation could at least partly explain the association of smoking with increased PCa progression and mortality, the investigators looked at tumor methylation and long-term follow-up data on 523 patients, 469 of whom (90%) had matched tumor gene expression data available. In all, 43% of the men were never smokers, 47% were former smokers, and 10% were current smokers.

The investigators examined tumor methylation profiles by smoking status, with the goals of determining whether smoking-associated changes in methylation are linked to mRNA expression, and whether they are related to disease prognosis.

They found that 40 DNA methylation regions were associated with smoking, and that 10 of the regions were strongly correlated with mRNA expression. They then used these 10 regions to create a smoking-related methylation score.

As noted before, the score was associated with adverse outcomes, with men in the highest third having an odds ratio (OR) for disease recurrence of 2.29 (P = .0007), and an OR of 4.21 for death from prostate cancer (P = .004)

The associations between smoking-related methylation scores and worse outcomes were slightly less strong but still significant after adjustment for Gleason score and pathologic stage.

“Importantly, there is evidence that smoking-related methylation changes in blood may be reversible; men who quit smoking for longer periods of time have methylation profiles similar to those of never-smokers,” the authors wrote.

More reason, if any is needed, to encourage patients to kick the habit comes from a study showing an association between cigarette smoking and tumor DNA methylation changes.

In a study of tumor tissue from men with prostate cancer (PCa) who underwent radical prostatectomy, smoking was associated with differential methylation across 40 genetic regions, and at least 10 of the regions significantly correlated with levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in corresponding genes.

Men whose tumors had the highest levels of smoking-associated methylation were more likely to have higher Gleason grade tumors or regional vs. local stage disease, reported Dr. Irene M. Shui of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle and her colleagues.

“[O]ur results provide support for the hypothesis that smoking-induced changes in DNA methylation may underlie the association of smoking with PCa recurrence and mortality,” they wrote (Cancer 2016 May 3. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30045).

To see whether DNA methylation could at least partly explain the association of smoking with increased PCa progression and mortality, the investigators looked at tumor methylation and long-term follow-up data on 523 patients, 469 of whom (90%) had matched tumor gene expression data available. In all, 43% of the men were never smokers, 47% were former smokers, and 10% were current smokers.

The investigators examined tumor methylation profiles by smoking status, with the goals of determining whether smoking-associated changes in methylation are linked to mRNA expression, and whether they are related to disease prognosis.

They found that 40 DNA methylation regions were associated with smoking, and that 10 of the regions were strongly correlated with mRNA expression. They then used these 10 regions to create a smoking-related methylation score.

As noted before, the score was associated with adverse outcomes, with men in the highest third having an odds ratio (OR) for disease recurrence of 2.29 (P = .0007), and an OR of 4.21 for death from prostate cancer (P = .004)

The associations between smoking-related methylation scores and worse outcomes were slightly less strong but still significant after adjustment for Gleason score and pathologic stage.

“Importantly, there is evidence that smoking-related methylation changes in blood may be reversible; men who quit smoking for longer periods of time have methylation profiles similar to those of never-smokers,” the authors wrote.

FROM CANCER

Key clinical point: This study demonstrates an association between smoking, DNA methylation, and potentially pathogenic genetic changes.

Major finding: Men with the highest smoking-related methylation scores were at increased risk for worse prostate cancer outcomes.

Data source: A retrospective study of tumor methylation and the association with outcomes in 523 men who underwent radical prostatectomy for adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and Prostate Cancer Foundation. The authors made no conflict of interest disclosures.

Total Hip Arthroplasty After Proximal Femoral Osteotomy: A Technique That Can Be Used to Address Presence of a Retained Intracortical Plate

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective treatment for advanced hip arthritis from a variety of causes, including osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, posttraumatic arthritis, and sequelae of developmental disorders. It is not uncommon to perform THA in the presence of a previous proximal femoral osteotomy that may have been performed for slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip, among other conditions. These osteotomies are commonly combined with internal fixation, a plate-and-screw device. These patients are at risk for developing degenerative arthritis at an earlier age than patients with other types of arthritis and subsequently may undergo THA at a younger age.1-3 Presence of a plate can pose a technical challenge during THA surgery. THA performed after intertrochanteric osteotomy has higher rates of perioperative and postoperative complications.4 Ferguson and colleagues4 noted difficulty during hardware removal in 24% of cases. Among the complications encountered were broken hardware, stripped screws, greater trochanteric fracture, stress risers from previous screw holes, canal narrowing from endosteal hypertrophy around hardware, and lateral cortical deficiency after removal of the side plate. As intertrochanteric osteotomies are often performed in patients who have yet to reach skeletal maturity, cortical hypertrophy can lead to complete coverage of the side plate and an “intracortical” position.

This article reports on 2 THA cases in which a technique was used to avoid intracortical plate removal and the resulting problems of lateral cortical deficiency. During each THA, the plate was left in place to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

An adolescent with bilateral SCFE was treated first with internal fixation of the right hip and subsequently with left proximal femoral osteotomy with internal fixation. He did well until age 31 years, when he developed progressively worsening pain about the left hip. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the left hip. Radiographs showed a sliding hip screw in place, with proximal femoral deformity consisting of femoral neck shortening and posterior angulation (Figures 1A, 1B). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 54.5.

Case 2

A 51-year-old woman presented with a history of right hip problems dating back to age 13 years, when she sustained a fracture of the right hip and was treated with internal fixation. At age 15 years, she underwent proximal femoral osteotomy to correct residual deformity. She did well until age 45 years, when she developed worsening hip symptoms. Clinical findings and imaging studies were consistent with advanced degenerative arthritis of the right hip. Radiographs showed a fixed-angle blade plate in the proximal femur, with significant proximal femoral deformity (Figures 1C, 1D). Preoperative Harris Hip Score was 53.6.

Surgical Technique

In both cases, a standard series of radiographs was obtained—an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis and AP and cross-table lateral radiographs of the operative hip (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) with a metal-artifact-reducing technique may be useful in determining amount of cortical bone remaining under the plate. CT showed limited lateral cortex beneath the side plate and bony overgrowth covering the side plate. Preoperative templating was performed using previously described techniques.5

During THA, before removing any portion of any retained hardware, the surgeon should perform 3 important actions: Dislocate the hip, perform all appropriate capsular releases, and reduce the hip. Dislocating the hip before hardware removal significantly decreases the risk for fracture caused by stress risers, as the force required for dislocation is much more controlled because of the capsular releases. After hardware removal, the hip can be easily redislocated, and the femoral neck osteotomy can be performed.

When plate and screws are in an intracortical position, the screws can be removed only after removing the small shell of cortical bone covering them. The amount of bone to be removed is minimal. After the screws are removed, the plate remains in place. A motorized device with a metal-cutting attachment is used to transect the construct at the junction of the plate and barrel (case 1) or at the bend of a fixed-angle device (case 2). Laparotomy sponges are placed around the proximal femur to minimize the amount of soft tissue that could be exposed to metal shavings. Copious irrigation is used throughout this part of the procedure. Osteotomes are used to elevate the proximal portion of the plate and the barrel, preserving the distal portion of the plate on the lateral cortex of the femoral shaft.

After the head is removed, the rest of the THA can be performed using standard press-fit insertion technique (Figures 2A-2D). Care must be taken to ensure that the distal aspect of the femoral stem bypasses the most distal screw hole by at least 2 cortical diameters in order to reduce the risk for periprosthetic fracture.

By 2-year follow-up, both patients had regained excellent range of motion, ambulation, and overall function. Postoperative Harris Hip Scores were 86.6 and 83.8, respectively. There were no radiographic signs of complications.

Discussion

THA can be challenging in the setting of previously placed internal fixation devices, particularly devices inserted during a patient’s adolescence, as significant bony overgrowth can occur. The standard approach has been to remove the internal fixation device and then perform the THA. In most cases, and particularly when the internal fixation device is in an intracortical position, the result is significant compromise of bone. This article describes a technique in which a portion of the hardware is retained to avoid compromise of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby allowing insertion of a noncemented femoral component.

THA is the most effective procedure for reducing hip pain and disability in the setting of degenerative changes.6 Patients with SCFE, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or developmental dysplasia of the hip generally are younger at the time they may be sufficiently symptomatic to consider THA.7,8 Many have had previous surgery using internal fixation devices. THAs after previous osteotomies with internal fixation devices are more technically demanding, require more operative time, are subject to more blood loss, and have a higher rate of complications, including femoral fracture. Ferguson and colleagues4 and Boos and colleagues9 found these surgeries were more difficult 33.8% and 36.8% of the time, respectively. For these reasons, some authors have recommended removing the internal fixation device as soon as the osteotomy is healed.4 However, this has not become the standard of care, and surgeons continue to perform THAs in the presence of a previous osteotomy with an internal fixation device in place.

The technique described in this article was used successfully in 2 cases. In each case, leaving the intracortical plate in place avoided compromise of the lateral femoral cortex and allowed insertion of a noncemented femoral component without complication. Of course, with the screw holes representing stress risers, careful insertion of the femoral component was required. Retaining the intracortical plate allowed it to function as part of the lateral femoral cortex, thereby maintaining the structural integrity of the femoral canal. As has been described for the 2 cases, a blade plate and plate and barrel were converted to a limited intracortical plate by removing the proximal portion of the plates—a modification that could be applied to other types of internal fixation devices that extend into the femoral neck as long as appropriate cutting tools are available.

Conclusion

THA in the setting of a retained internal fixation device is relatively common. This article describes a technique that can be used when a plate applied to the lateral femoral cortex has become intracortical as a result of extensive bony overgrowth. In using this technique to avoid plate removal, the surgeon eliminates the need for more extensive procedures aimed at compensating for deficiency of the femoral cortex in the area of plate removal. Although only 2 cases are presented here, this technique potentially can be used more broadly in these specific clinical situations.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

1. Engesæter LB, Engesæter IØ, Fenstad AM, et al. Low revision rate after total hip arthroplasty in patients with pediatric hip diseases. Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):436-441.

2. Froberg L, Christensen F, Pedersen NW, Overgaard S. The need for total hip arthroplasty in Perthes disease: a long-term study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):1134-1140.

3. Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesæter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586.

4. Ferguson GM, Cabanela ME, Ilstrup DM. Total hip arthroplasty after failed intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76(2):252-257.

5. Scheerlinck T. Primary hip arthroplasty templating on standard radiographs. A stepwise approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(4):432-442.

6. Wroblewski BM, Siney PD. Charnley low-friction arthroplasty of the hip. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(292):191-201.

7. Chandler HP, Reineck FT, Wixson RL, McCarthy JC. Total hip replacement in patients younger than thirty years old. A five-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63(9):1426-1434.

8. Dorr LD, Luckett M, Conaty JP. Total hip arthroplasties in patients younger than 45 years. A nine- to ten-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(260):215-219.

9. Boos N, Krushell R, Ganz R, Müller ME. Total hip arthroplasty after previous proximal femoral osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):247-253.

A Retrospective Analysis of Hemostatic Techniques in Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty: Traditional Electrocautery, Bipolar Sealer, and Argon Beam Coagulation

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.

In traditional (Bovie) electrocautery, a unipolar device delivers an electrical current to tissues through a pencil-like instrument. Intraoperative tissue temperatures can exceed 400°C.12 In BS, radiofrequency energy is delivered through a saline medium, which increases the contact area, acts as an electrode, and maintains a cooler environment during electrocautery. Proposed advantages are reduced tissue destruction and absence of smoke.12 There is evidence both for10,12-16 and against17-20 use of BS in total joint arthroplasty. ABC, a novel hemostasis method, has been studied in the context of orthopedics21,22 but not TKA specifically. ABC establishes a monopolar electric circuit between a handheld device and the target tissues by channeling electrons through ionized argon gas. Hemostasis is achieved through thermal coagulation. Tissue penetration can be adjusted by changing power, probe-to-target distance, and duration of use.23 We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of all 3 electrocautery methods during TKA. We hypothesized the 3 methods would be clinically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss (EBL), 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive primary TKAs performed by Dr. Levine between October 2010 and November 2011. Patients were identified by querying an internal database. Exclusion criteria were prior ipsilateral open knee procedure, prior fracture, nonuse of our standard hemostatic protocol, and either tourniquet time under 40 minutes or intraoperative documentation of tourniquet failure. As only 9 patients were initially identified for the TE cohort, the same database was used to add 32 patients treated between April 2009 and October 2009 (before our institution began using BS and ABC).

Clinical charts were reviewed, and baseline demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative Hb level) were abstracted, as were outcome metrics (EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, postoperative transfusions, adverse events (AEs) before discharge, and change in Hb level from before surgery to after surgery, in recovery room and on discharge). Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute). Given the hypothesis that the 3 hemostasis methods would be clinically equivalent, 2 one-sided tests (TOSTs) of equivalence were performed with an α of 0.05. With TOST, the traditional null and alternative hypotheses are reversed; thus, P < .05 identifies statistical equivalence. The advantage of this study design is that equivalence can be identified, whereas traditional study designs can identify only a lack of statistical difference.24 We used our consensus opinions to set clinical insignificance thresholds for EBL (150 mL), wound drainage (150 mL), decrease from postoperative Hb level (1 g/dL), and operative time (10 minutes). Patients who received a blood transfusion were subsequently excluded from analysis in order to avoid skewing Hb-level depreciation calculations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were used to compare preoperative variables, transfusion requirements, hospital length of stay, and AE rates by hemostasis type.

Cautery Technique

In all cases, TE was used for surgical dissection, which followed a standard midvastus approach. Then, for meniscal excision, the capsule and meniscal attachment sites were treated with TE, BS, or ABC. During cement hardening, an available supplemental cautery option was used to achieve hemostasis of the suprapatellar fat pad and visible meniscal attachment sites. All other aspects of the procedure and the postoperative protocols—including the anticoagulation and rapid rehabilitation (early ambulation and therapy) protocols—were similar for all patients. The standard anticoagulation protocol was to use low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated. Tranexamic acid was not used at our institution during the study period.

Results

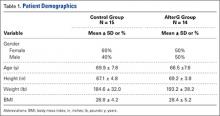

For the study period, 280 cases (41 TE, 203 BS, 36 ABC) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 280 TKAs, 261 (93.21%) were performed for degenerative arthritis. There was no statistically significant difference among cohorts in indication (χ2 = 1.841, P = .398) or sex (χ2 = 1.176, P= .555).

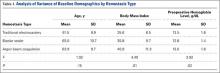

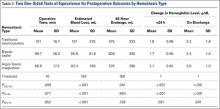

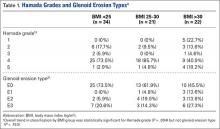

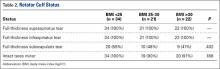

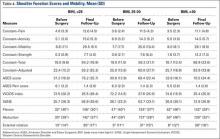

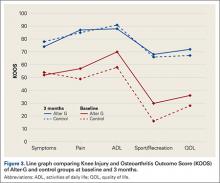

Table 1 lists the cohorts’ baseline demographics (mean age, BMI, preoperative Hb level) and comparative ANOVA results. TOSTs of equivalence were performed to compare operative time, EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, and postoperative Hb-level depreciation among hemostasis types. Changes in Hb level were calculated for the immediate postoperative period and time of discharge (Table 2). ANOVA of hospital length of stay demonstrated no significant difference in means among groups (P = .09).

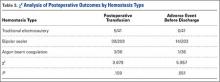

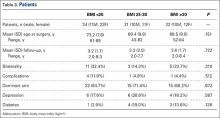

The cohorts were compared with respect to use of postoperative transfusions and incidence of postoperative AEs (Table 3). The TE cohort did not have any AEs. Of the 203 BS patients, 14 (7%) had 1 or more AEs, which included acute kidney injury (3 cases), electrolyte disturbance (3), urinary tract infection (2), oxygen desaturation (2), altered mental status (1), pneumonia (1), arrhythmia (1), congestive heart failure exacerbation (1), dehiscence (1), pulmonary embolism (2), and hypotension (1). Of the 36 ABC patients, 1 (3%) had arrhythmia, pneumonia, sepsis, and altered mental status.

Discussion

With the population aging, the demand for TKA is greater than ever.1 As surgical volume increases, the ability to minimize the rates of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative anemia, and transfusion is becoming increasingly important to patients and the healthcare system. There is no consensus as to which cautery method is ideal. Other investigators have identified differences in clinical outcomes between cautery systems, but reported results are largely conflicting.10,12-20 In addition, no one has studied the utility of ABC in TKA. In the present retrospective cohort analysis, we hypothesized that TE, BS, and ABC would be clinically equivalent in primary TKA with respect to EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative Hb level.

The data on hemostatic technology in primary TKA are inconclusive. In an age- and sex-matched study comparing TE and BS in primary TKA, BS used with shed blood autotransfusion reduced homologous blood transfusions by a factor of 5.16 In addition, BS patients lost significantly less total visible blood (intraoperative EBL, postoperative drain output), and their magnitude of postoperative Hb-level depreciations at time of discharge was significantly lower. In a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing TE with BS, adjusted blood loss and need for autologous blood transfusions were lower in BS patients,10 though there was no significant difference in Knee Society Scale scores between the 2 treatment arms. However, analysis was potentially biased in that multiple authors had financial ties to Salient Surgical Technologies, the manufacturer of the BS device used in the study. Other prospective randomized trials of patients who had primary TKA with either TE or BS did not find any significant difference in postoperative Hb level, postoperative drainage, or transfusion requirements.19 ABC has been studied in the context of orthopedics but not joint arthroplasty specifically. This technology was anecdotally identified as a means of attaining hemostasis in foot and ankle surgery after failure of TE and other conventional means.22 ABC has also been identified as a successful adjuvant to curettage in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts.21 However, ABC has not been compared with TE or BS in the orthopedic literature.

In the present study, analysis of preoperative variables revealed a statistically but not clinically significant difference in BMI among cohorts. Mean (SD) BMI was 35.6 (6.5) for TE patients, 35.8 (9.7) for BS patients, and 40.9 (11.3) for ABC patients. (Previously, BMI did not correlate with intraoperative blood loss in TKA.25) Analysis also revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant and inconsequential difference in Hb level among cohorts. Mean (SD) preoperative Hb level was 13.5 (1.6) g/dL for TE patients, 12.8 (1.4) g/dL for BS patients, and 13.0 (1.6) g/dL for ABC patients. As decreases from preoperative baseline Hb levels were the intended focus of analysis—not absolute Hb levels—this finding does not refute postoperative analyses.

Our results suggest that, though TE may have relatively longer operative times in primary TKA, it is clinically equivalent to BS and ABC with respect to EBL and postoperative change in Hb levels. In addition, postoperative drainage was lower in TE than in BS and ABC, which were equivalent. No significant differences were found among hemostasis types with respect to postoperative transfusion requirements.

The prevalence distribution of predischarge AEs trended toward significance (χ2 = 5.957, P = .051), despite not meeting the predetermined α level. Rates of predischarge AEs were 0% (0/41) for TE patients, 7% (14/203) for BS patients, and 3% (1/36) for ABC patients. AEs included acute kidney injuries, electrolyte disturbances, urinary tract infections, oxygen desaturation, altered mental status, sepsis/infections, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure exacerbation, dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, and hypotension. Clearly, many of these AEs are not attributable to the hemostasis system used.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, documentation inadequate to account for drainage amount reinfused, and limited data on which clinical insignificance thresholds were based. In addition, reliance on historical data may have introduced bias into the analysis. The historical data used to increase the size of the TE cohort may reflect a period of relative inexperience and may have contributed to the longer operative times relative to those of the ABC cohort (Dr. Levine used ABC later in his career).

Traditional electrocautery remains a viable option in primary TKA. With its low cost and hemostasis equivalent to that of BS and ABC, TE deserves consideration equal to that given to these more modern hemostasis technologies. Cost per case is about $10 for TE versus $500 for BS and $110 for ABC.17 Soaring healthcare expenditures may warrant returning to TE or combining cautery techniques and other agents in primary TKA in order to reduce the number of transfusions and associated surgical costs.

1. Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227-1236.

2. Leijtens B, Kremers van de Hei K, Jansen J, Koëter S. High complication rate after total knee and hip replacement due to perioperative bridging of anticoagulant therapy based on the 2012 ACCP guideline. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(9):1335-1341.

3. Park CH, Lee SH, Kang DG, Cho KY, Lee SH, Kim KI. Compartment syndrome following total knee arthroplasty: clinical results of late fasciotomy. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(3):177-181.

4. Pedersen AB, Mehnert F, Sorensen HT, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S, Johnsen SP. The risk of venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, stroke, major bleeding and death in patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement: a 15-year retrospective cohort study of routine clinical practice. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):479-485.

5. Carson JL, Poses RM, Spence RK, Bonavita G. Severity of anaemia and operative mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1988;1(8588):727-729.

6. Carson JL, Duff A, Poses RM, et al. Effect of anaemia and cardiovascular disease on surgical mortality and morbidity. Lancet. 1996;348(9034):1055-1060.

7. Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion transmitted infections. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(6):671-676.

8. Kang DG, Khurana S, Baek JH, Park YS, Lee SH, Kim KI. Efficacy and safety using autotransfusion system with postoperative shed blood following total knee arthroplasty in haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2014;20(1):129-132.

9. Aguilera X, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Bosch A, et al. Efficacy and safety of fibrin glue and tranexamic acid to prevent postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2001-2007.

10. Marulanda GA, Krebs VE, Bierbaum BE, et al. Hemostasis using a bipolar sealer in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(12):E179-E183.

11. Katkhouda N, Friedlander M, Darehzereshki A, et al. Argon beam coagulation versus fibrin sealant for hemostasis following liver resection: a randomized study in a porcine model. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60(125):1110-1116.

12. Marulanda GA, Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Delanois RE, Mont MA. Reductions in blood loss with a bipolar sealer in total hip arthroplasty. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2008;5(2):125-131.

13. Morris MJ, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Hemostasis in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty: pilot study comparing standard electrocautery and a bipolar sealer. Surg Technol Int. 2010;20:352-356.

14. Clement RC, Kamath AF, Derman PB, Garino JP, Lee GC. Bipolar sealing in revision total hip arthroplasty for infection: efficacy and cost analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1376-1381.

15. Rosenberg AG. Reducing blood loss in total joint surgery with a saline-coupled bipolar sealing technology. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):82-85.

16. Pfeiffer M, Bräutigam H, Draws D, Sigg A. A new bipolar blood sealing system embedded in perioperative strategies vs. a conventional regimen for total knee arthroplasty: results of a matched-pair study. Ger Med Sci. 2005;3:Doc10.

17. Morris MJ, Barrett M, Lombardi AV Jr, Tucker TL, Berend KR. Randomized blinded study comparing a bipolar sealer and standard electrocautery in reducing transfusion requirements in anterior supine intermuscular total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1614-1617.

18. Barsoum WK, Klika AK, Murray TG, Higuera C, Lee HH, Krebs VE. Prospective randomized evaluation of the need for blood transfusion during primary total hip arthroplasty with use of a bipolar sealer. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(6):513-518.

19. Plymale MF, Capogna BM, Lovy AJ, Adler ML, Hirsh DM, Kim SJ. Unipolar vs bipolar hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1133-1137.e1.

20. Zeh A, Messer J, Davis J, Vasarhelyi A, Wohlrab D. The Aquamantys system—an alternative to reduce blood loss in primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(7):1072-1077.

21. Cummings JE, Smith RA, Heck RK Jr. Argon beam coagulation as adjuvant treatment after curettage of aneurysmal bone cysts: a preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):231-237.

22. Adams ML, Steinberg JS. Argon beam coagulation in foot and ankle surgery. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(6):780-782.

23. Neumayer L, Vargo D. Principles of preoperative and operative surgery. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:211-239.

24. Walker E, Nowacki AS. Understanding equivalence and noninferiority testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(2):192-196.

25. Hrnack SA, Skeen N, Xu T, Rosenstein AD. Correlation of body mass index and blood loss during total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2012;41(10):467-471.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.

In traditional (Bovie) electrocautery, a unipolar device delivers an electrical current to tissues through a pencil-like instrument. Intraoperative tissue temperatures can exceed 400°C.12 In BS, radiofrequency energy is delivered through a saline medium, which increases the contact area, acts as an electrode, and maintains a cooler environment during electrocautery. Proposed advantages are reduced tissue destruction and absence of smoke.12 There is evidence both for10,12-16 and against17-20 use of BS in total joint arthroplasty. ABC, a novel hemostasis method, has been studied in the context of orthopedics21,22 but not TKA specifically. ABC establishes a monopolar electric circuit between a handheld device and the target tissues by channeling electrons through ionized argon gas. Hemostasis is achieved through thermal coagulation. Tissue penetration can be adjusted by changing power, probe-to-target distance, and duration of use.23 We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of all 3 electrocautery methods during TKA. We hypothesized the 3 methods would be clinically equivalent with respect to estimated blood loss (EBL), 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative hemoglobin (Hb) level.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive primary TKAs performed by Dr. Levine between October 2010 and November 2011. Patients were identified by querying an internal database. Exclusion criteria were prior ipsilateral open knee procedure, prior fracture, nonuse of our standard hemostatic protocol, and either tourniquet time under 40 minutes or intraoperative documentation of tourniquet failure. As only 9 patients were initially identified for the TE cohort, the same database was used to add 32 patients treated between April 2009 and October 2009 (before our institution began using BS and ABC).

Clinical charts were reviewed, and baseline demographics (age, body mass index [BMI], preoperative Hb level) were abstracted, as were outcome metrics (EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, postoperative transfusions, adverse events (AEs) before discharge, and change in Hb level from before surgery to after surgery, in recovery room and on discharge). Statistical analyses were performed with JMP Version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute). Given the hypothesis that the 3 hemostasis methods would be clinically equivalent, 2 one-sided tests (TOSTs) of equivalence were performed with an α of 0.05. With TOST, the traditional null and alternative hypotheses are reversed; thus, P < .05 identifies statistical equivalence. The advantage of this study design is that equivalence can be identified, whereas traditional study designs can identify only a lack of statistical difference.24 We used our consensus opinions to set clinical insignificance thresholds for EBL (150 mL), wound drainage (150 mL), decrease from postoperative Hb level (1 g/dL), and operative time (10 minutes). Patients who received a blood transfusion were subsequently excluded from analysis in order to avoid skewing Hb-level depreciation calculations. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and χ2 tests were used to compare preoperative variables, transfusion requirements, hospital length of stay, and AE rates by hemostasis type.

Cautery Technique

In all cases, TE was used for surgical dissection, which followed a standard midvastus approach. Then, for meniscal excision, the capsule and meniscal attachment sites were treated with TE, BS, or ABC. During cement hardening, an available supplemental cautery option was used to achieve hemostasis of the suprapatellar fat pad and visible meniscal attachment sites. All other aspects of the procedure and the postoperative protocols—including the anticoagulation and rapid rehabilitation (early ambulation and therapy) protocols—were similar for all patients. The standard anticoagulation protocol was to use low-molecular-weight heparin, unless contraindicated. Tranexamic acid was not used at our institution during the study period.

Results

For the study period, 280 cases (41 TE, 203 BS, 36 ABC) met the inclusion criteria. Of the 280 TKAs, 261 (93.21%) were performed for degenerative arthritis. There was no statistically significant difference among cohorts in indication (χ2 = 1.841, P = .398) or sex (χ2 = 1.176, P= .555).

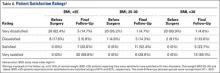

Table 1 lists the cohorts’ baseline demographics (mean age, BMI, preoperative Hb level) and comparative ANOVA results. TOSTs of equivalence were performed to compare operative time, EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, and postoperative Hb-level depreciation among hemostasis types. Changes in Hb level were calculated for the immediate postoperative period and time of discharge (Table 2). ANOVA of hospital length of stay demonstrated no significant difference in means among groups (P = .09).

The cohorts were compared with respect to use of postoperative transfusions and incidence of postoperative AEs (Table 3). The TE cohort did not have any AEs. Of the 203 BS patients, 14 (7%) had 1 or more AEs, which included acute kidney injury (3 cases), electrolyte disturbance (3), urinary tract infection (2), oxygen desaturation (2), altered mental status (1), pneumonia (1), arrhythmia (1), congestive heart failure exacerbation (1), dehiscence (1), pulmonary embolism (2), and hypotension (1). Of the 36 ABC patients, 1 (3%) had arrhythmia, pneumonia, sepsis, and altered mental status.

Discussion

With the population aging, the demand for TKA is greater than ever.1 As surgical volume increases, the ability to minimize the rates of intraoperative bleeding, postoperative anemia, and transfusion is becoming increasingly important to patients and the healthcare system. There is no consensus as to which cautery method is ideal. Other investigators have identified differences in clinical outcomes between cautery systems, but reported results are largely conflicting.10,12-20 In addition, no one has studied the utility of ABC in TKA. In the present retrospective cohort analysis, we hypothesized that TE, BS, and ABC would be clinically equivalent in primary TKA with respect to EBL, 48-hour wound drainage, operative time, and change from preoperative Hb level.

The data on hemostatic technology in primary TKA are inconclusive. In an age- and sex-matched study comparing TE and BS in primary TKA, BS used with shed blood autotransfusion reduced homologous blood transfusions by a factor of 5.16 In addition, BS patients lost significantly less total visible blood (intraoperative EBL, postoperative drain output), and their magnitude of postoperative Hb-level depreciations at time of discharge was significantly lower. In a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing TE with BS, adjusted blood loss and need for autologous blood transfusions were lower in BS patients,10 though there was no significant difference in Knee Society Scale scores between the 2 treatment arms. However, analysis was potentially biased in that multiple authors had financial ties to Salient Surgical Technologies, the manufacturer of the BS device used in the study. Other prospective randomized trials of patients who had primary TKA with either TE or BS did not find any significant difference in postoperative Hb level, postoperative drainage, or transfusion requirements.19 ABC has been studied in the context of orthopedics but not joint arthroplasty specifically. This technology was anecdotally identified as a means of attaining hemostasis in foot and ankle surgery after failure of TE and other conventional means.22 ABC has also been identified as a successful adjuvant to curettage in the treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts.21 However, ABC has not been compared with TE or BS in the orthopedic literature.

In the present study, analysis of preoperative variables revealed a statistically but not clinically significant difference in BMI among cohorts. Mean (SD) BMI was 35.6 (6.5) for TE patients, 35.8 (9.7) for BS patients, and 40.9 (11.3) for ABC patients. (Previously, BMI did not correlate with intraoperative blood loss in TKA.25) Analysis also revealed a statistically significant but clinically insignificant and inconsequential difference in Hb level among cohorts. Mean (SD) preoperative Hb level was 13.5 (1.6) g/dL for TE patients, 12.8 (1.4) g/dL for BS patients, and 13.0 (1.6) g/dL for ABC patients. As decreases from preoperative baseline Hb levels were the intended focus of analysis—not absolute Hb levels—this finding does not refute postoperative analyses.

Our results suggest that, though TE may have relatively longer operative times in primary TKA, it is clinically equivalent to BS and ABC with respect to EBL and postoperative change in Hb levels. In addition, postoperative drainage was lower in TE than in BS and ABC, which were equivalent. No significant differences were found among hemostasis types with respect to postoperative transfusion requirements.

The prevalence distribution of predischarge AEs trended toward significance (χ2 = 5.957, P = .051), despite not meeting the predetermined α level. Rates of predischarge AEs were 0% (0/41) for TE patients, 7% (14/203) for BS patients, and 3% (1/36) for ABC patients. AEs included acute kidney injuries, electrolyte disturbances, urinary tract infections, oxygen desaturation, altered mental status, sepsis/infections, arrhythmias, congestive heart failure exacerbation, dehiscence, pulmonary embolism, and hypotension. Clearly, many of these AEs are not attributable to the hemostasis system used.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design, documentation inadequate to account for drainage amount reinfused, and limited data on which clinical insignificance thresholds were based. In addition, reliance on historical data may have introduced bias into the analysis. The historical data used to increase the size of the TE cohort may reflect a period of relative inexperience and may have contributed to the longer operative times relative to those of the ABC cohort (Dr. Levine used ABC later in his career).

Traditional electrocautery remains a viable option in primary TKA. With its low cost and hemostasis equivalent to that of BS and ABC, TE deserves consideration equal to that given to these more modern hemostasis technologies. Cost per case is about $10 for TE versus $500 for BS and $110 for ABC.17 Soaring healthcare expenditures may warrant returning to TE or combining cautery techniques and other agents in primary TKA in order to reduce the number of transfusions and associated surgical costs.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable and successful treatment for end-stage degenerative joint disease of the knee. Given the reproducibility of its generally excellent outcomes, TKA is increasingly being performed.1 However, the potential complications of this procedure can be devastating.2-4 The arthroplasty literature has shed light on the detrimental effects of postoperative blood loss and anemia.5,6 In addition, the increase in transfusion burden among patients is not without risk.7 Given these concerns, surgeons have been tasked with determining the ideal methods for minimizing blood transfusions and postoperative hematomas and anemia. Several strategies have been described.8-11 Hemostasis can be achieved with use of intravenous medications, intra-articular agents, or electrocautery devices. Electrocautery technologies include traditional electrocautery (TE), saline-coupled bipolar sealer (BS), and argon beam coagulation (ABC). There is controversy as to whether outcomes are better with one hemostasis method over another and whether these methods are worth the additional cost.