User login

TauRx still rooting for its methylene blue AD drug, despite controversial study results

SAN DIEGO – An anti-tau compound that has stirred scientific controversy for 8 years will continue along its developmental pathway at a much lower dose, despite yet another study that has Alzheimer’s researchers scratching their heads.

The drug, dubbed LMTM, is a derivative of the dye methylene blue. Its most recent phase III study, reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, found that 100 mg twice a day conferred no cognitive or functional benefit upon patients with mild AD, compared with a control dose of 4 mg.

Some significant differences, however, did emerge in two prespecified subanalyses of the 4-mg control group. Patients who took the low dose, intended to be a placebo comparator, did better than those on the high dose – but only if they were not taking any standard symptomatic AD medications.

Based on these findings, TauRx, which is developing LMTM, will abandon the 100-mg dose and refocus on the 4-mg dose, said Claude Wischik, MD, chairman and chief executive officer of the Singapore-based company.

“I think it looks effective and there’s no advantage to going to a higher dose,” Dr. Wischik said in an interview. “The 100-mg dose doesn’t offer anything above the 4-mg dose, and we saw more dropouts in the higher-dose group. We will go forward with a new trial using 4 mg.”

The new commitment to 4 mg turns LMTM’s prior development trajectory on its head, as nothing lower than 75 mg has been investigated in a phase III study. The 4-mg control dose was used as a placebo stand-in, since LMTM colors urine blue or green. The low dose was considered biologically inactive and used to maintain the study blind.

Dr. Wischik has been investigating LMTM as a tau anti-aggregant for 10 years, first publicly reporting clinical data in 2008. LMTM has never posted significant cognitive or functional benefits in any primary analysis. Instead, it has moved forward based on a series of subanalyses that showed significant or near-significant benefits in smaller, meticulously constructed subgroups – conclusions that critics have called questionable at best. The most recent of these examined the drug’s effect in patients with mild to moderate disease and was presented last July at the Alzheimer’s Association’s International Conference (AAIC).

That study also didn’t meet its primary endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients, but TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who were not taking memantine or cholinesterase inhibitors.

Among these patients, those taking 75 mg twice daily declined 6 points less on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) than those taking 4 mg. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 6 points less than the 4-mg group. On the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL), patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 7 points higher than did the placebo group.

At AAIC, researchers suggested that the monotherapy groups could have had a less aggressive disease course, or might not have had Alzheimer’s disease at all. Others complained about the unorthodox grouping of control patients in the subgroup analysis.

It was after digesting these data that TauRx investigators changed the statistical analysis of the current study, then in its final months, from a randomized trial to a cohort analysis. This was done before data lockdown, but it was still a dramatic shift from the original study design.

“The primary analysis was changed to essentially analyze this as a cohort study,” said Lon Schneider, MD, who presented the results at CTAD. “The comparisons of interest were patients taking 100 mg twice a day who were not on [symptomatic treatment], compared to the original control group of 4 mg. The other comparison was the 4-mg group not on cholinesterase inhibitors to the 4-mg group that was on them.”

The 18-month trial randomized 800 patients with mild AD to 100 mg LMTM twice daily or to 4 mg twice daily. Patients were drawn from two global regions: Canada and the United States, and eastern Europe and Australia.

The study group was a typical one, with a mean age of 70 years and a mean Mini Mental State Exam score of 22. The mean ADAS-cog score was 17. Most (80%) were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor, memantine, or both; 20% were naive to these medications.

Primary endpoints were the ADAS-cog11, ADCS-ADL, and left ventricular volume. Secondary outcomes included the Mini Mental State Exam and Neuropsychiatric Index.

In the primary analysis as the trial was created and conducted, LMTM 100 mg/twice daily did not confer any benefit, compared with the control 4-mg dose. The decline curves were virtually superimposable in the ADAS-cog score, ADCS-ADL score, and in loss of left ventricular volume.

This same nonsignificant pattern occurred in all the secondary endpoints, which Dr. Schneider did not show.

The cohort analyses stratified patients according to whether they were taking any cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, at baseline. That was where some differences did emerge.

The first compared the entire 4-mg cohort to the subset of patients taking 100 mg as monotherapy (absent any symptomatic medications). Both the 100-mg and 4-mg groups declined linearly on all measures, but compared to the 4 mg group the 100 mg group experienced about a 3-point benefit on both the ADAS-cog and ADS-ADL measures.* The 100-mg group also experienced significantly more dropouts (45% vs. 23%), with 16% of those being due to adverse events.

The second analysis compared the two 4-mg groups: those taking LMTM as monotherapy and those taking it in combination with standard AD medications. Again, both groups declined, but that decline was attenuated in the monotherapy group, with a 4-point advantage in the ADAS-cog and nearly a 5-point advantage in the ADS-ADL. The 3-cc ventricular volume advantage was seen as well.

Again, Dr. Schneider said, these results were recapitulated in the secondary endpoints, which he did not show.

The trial seems to upend TauRx’s earlier firm contention that the previously tested higher doses slow cognitive and functional decline – a view Dr. Wischik clung to after the July data were released. Dr. Schneider attempted to address this by suggesting that “the 4-mg dose may not have been as inactive as the developer thought.”

However, he noted, another possibility is that the patients who took the 4-mg dose but not the symptomatic drugs “may have had a more benign course of disease, compared to those taking cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.”

This new study has now aroused the same criticism levied last summer. Maria Carrillo, PhD, chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, was blunt in her assessment.

“The results of post hoc analyses, even when preplanned, are not valid and could be spurious,” she said. “They may mean nothing. As a field, we have been lured into rabbit holes in the past due to post hoc analyses and wasted too much time and way too much money. Of course, companies can do what they want as next steps in trials if they have the financial backing to do so.”

Dr. Wischik, however, said both the July data and the new data clearly justify taking the 4-mg dose forward in a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

“It’s really very exciting that we got exactly the same results now as we did in the post-hoc analysis [of the July data],” he said in an interview. “We predicted these results based on what we saw, we changed the statistical analysis, and we got the predicted results. This has nothing to do with data scouring.”

The question of whether the monotherapy patients are fundamentally different from those taking standard AD drugs is a valid one, he admitted. “We can’t avoid that criticism until we do another study where people who are not on any AD treatment are randomized.”

Dr. Wischik was then asked whether it would be difficult to recruit an entire cohort of patients with mild Alzheimer’s who are willing to forego approved symptomatic medications while in such a study. He did not think that would be problematic.

“Twenty percent of our cohort was already in that slot,” he said. “This practice pattern is determined somewhat by geography and somewhat by the type of clinician treating the patient. People also go on the drugs and then come off for various reasons. But even in the U.S., only 55% of Alzheimer’s patients are taking them.”

Dr. Wischik didn’t mention the problem of finding an appropriate placebo for such a study. If indeed the 4-mg dose is biologically active, such a placebo would have to be demonstrably inert, as well as provide the appropriate urine color to keep the blinding unbroken.

“That’s a challenge,” Dr. Schneider said.

Dr. Schneider was a coinvestigator on the LMTM phase III program. He has disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Correction, 12/12/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the results of this study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

There are several reasons why this kind of analysis defies scientific credibility.

The term “monotherapy” is really a euphemism for substandard care before the study. These patients on monotherapy were not selected to be so. These were people with mild to moderate AD dementia who should have been on memantine or a cholinesterase inhibitor and were not, for unknown reasons. They represent a health care bias, and on that fact alone this comparison should not have even been mentioned. Calling it monotherapy is an attempt to distract from the fact that this was an indication bias that defines this group.

The claim that this analysis was done before the database lock is true in principal. But because the investigators had already seen this result in their previous study, which was identically designed, they cannot really claim this was truly an ad hoc analysis. They already knew what they were going to see.

In July, the investigators claimed that the 100-mg dose was effective in monotherapy. They have been convinced over the entire course of development that the 4-mg dose was ineffective. Now they are retracting that. To me, this apparent wild goose chase for any kind of effect trivializes the entire process of a clinical trial.

What I believe we are observing here is a profound placebo effect that can occur when people who have been getting substandard care are put in a clinical trial and exposed to good care.

David Knopman, MD, is a clinical neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and a member of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

There are several reasons why this kind of analysis defies scientific credibility.

The term “monotherapy” is really a euphemism for substandard care before the study. These patients on monotherapy were not selected to be so. These were people with mild to moderate AD dementia who should have been on memantine or a cholinesterase inhibitor and were not, for unknown reasons. They represent a health care bias, and on that fact alone this comparison should not have even been mentioned. Calling it monotherapy is an attempt to distract from the fact that this was an indication bias that defines this group.

The claim that this analysis was done before the database lock is true in principal. But because the investigators had already seen this result in their previous study, which was identically designed, they cannot really claim this was truly an ad hoc analysis. They already knew what they were going to see.

In July, the investigators claimed that the 100-mg dose was effective in monotherapy. They have been convinced over the entire course of development that the 4-mg dose was ineffective. Now they are retracting that. To me, this apparent wild goose chase for any kind of effect trivializes the entire process of a clinical trial.

What I believe we are observing here is a profound placebo effect that can occur when people who have been getting substandard care are put in a clinical trial and exposed to good care.

David Knopman, MD, is a clinical neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and a member of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

There are several reasons why this kind of analysis defies scientific credibility.

The term “monotherapy” is really a euphemism for substandard care before the study. These patients on monotherapy were not selected to be so. These were people with mild to moderate AD dementia who should have been on memantine or a cholinesterase inhibitor and were not, for unknown reasons. They represent a health care bias, and on that fact alone this comparison should not have even been mentioned. Calling it monotherapy is an attempt to distract from the fact that this was an indication bias that defines this group.

The claim that this analysis was done before the database lock is true in principal. But because the investigators had already seen this result in their previous study, which was identically designed, they cannot really claim this was truly an ad hoc analysis. They already knew what they were going to see.

In July, the investigators claimed that the 100-mg dose was effective in monotherapy. They have been convinced over the entire course of development that the 4-mg dose was ineffective. Now they are retracting that. To me, this apparent wild goose chase for any kind of effect trivializes the entire process of a clinical trial.

What I believe we are observing here is a profound placebo effect that can occur when people who have been getting substandard care are put in a clinical trial and exposed to good care.

David Knopman, MD, is a clinical neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and a member of the Alzheimer’s Association Medical and Scientific Advisory Council.

SAN DIEGO – An anti-tau compound that has stirred scientific controversy for 8 years will continue along its developmental pathway at a much lower dose, despite yet another study that has Alzheimer’s researchers scratching their heads.

The drug, dubbed LMTM, is a derivative of the dye methylene blue. Its most recent phase III study, reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, found that 100 mg twice a day conferred no cognitive or functional benefit upon patients with mild AD, compared with a control dose of 4 mg.

Some significant differences, however, did emerge in two prespecified subanalyses of the 4-mg control group. Patients who took the low dose, intended to be a placebo comparator, did better than those on the high dose – but only if they were not taking any standard symptomatic AD medications.

Based on these findings, TauRx, which is developing LMTM, will abandon the 100-mg dose and refocus on the 4-mg dose, said Claude Wischik, MD, chairman and chief executive officer of the Singapore-based company.

“I think it looks effective and there’s no advantage to going to a higher dose,” Dr. Wischik said in an interview. “The 100-mg dose doesn’t offer anything above the 4-mg dose, and we saw more dropouts in the higher-dose group. We will go forward with a new trial using 4 mg.”

The new commitment to 4 mg turns LMTM’s prior development trajectory on its head, as nothing lower than 75 mg has been investigated in a phase III study. The 4-mg control dose was used as a placebo stand-in, since LMTM colors urine blue or green. The low dose was considered biologically inactive and used to maintain the study blind.

Dr. Wischik has been investigating LMTM as a tau anti-aggregant for 10 years, first publicly reporting clinical data in 2008. LMTM has never posted significant cognitive or functional benefits in any primary analysis. Instead, it has moved forward based on a series of subanalyses that showed significant or near-significant benefits in smaller, meticulously constructed subgroups – conclusions that critics have called questionable at best. The most recent of these examined the drug’s effect in patients with mild to moderate disease and was presented last July at the Alzheimer’s Association’s International Conference (AAIC).

That study also didn’t meet its primary endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients, but TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who were not taking memantine or cholinesterase inhibitors.

Among these patients, those taking 75 mg twice daily declined 6 points less on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) than those taking 4 mg. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 6 points less than the 4-mg group. On the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL), patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 7 points higher than did the placebo group.

At AAIC, researchers suggested that the monotherapy groups could have had a less aggressive disease course, or might not have had Alzheimer’s disease at all. Others complained about the unorthodox grouping of control patients in the subgroup analysis.

It was after digesting these data that TauRx investigators changed the statistical analysis of the current study, then in its final months, from a randomized trial to a cohort analysis. This was done before data lockdown, but it was still a dramatic shift from the original study design.

“The primary analysis was changed to essentially analyze this as a cohort study,” said Lon Schneider, MD, who presented the results at CTAD. “The comparisons of interest were patients taking 100 mg twice a day who were not on [symptomatic treatment], compared to the original control group of 4 mg. The other comparison was the 4-mg group not on cholinesterase inhibitors to the 4-mg group that was on them.”

The 18-month trial randomized 800 patients with mild AD to 100 mg LMTM twice daily or to 4 mg twice daily. Patients were drawn from two global regions: Canada and the United States, and eastern Europe and Australia.

The study group was a typical one, with a mean age of 70 years and a mean Mini Mental State Exam score of 22. The mean ADAS-cog score was 17. Most (80%) were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor, memantine, or both; 20% were naive to these medications.

Primary endpoints were the ADAS-cog11, ADCS-ADL, and left ventricular volume. Secondary outcomes included the Mini Mental State Exam and Neuropsychiatric Index.

In the primary analysis as the trial was created and conducted, LMTM 100 mg/twice daily did not confer any benefit, compared with the control 4-mg dose. The decline curves were virtually superimposable in the ADAS-cog score, ADCS-ADL score, and in loss of left ventricular volume.

This same nonsignificant pattern occurred in all the secondary endpoints, which Dr. Schneider did not show.

The cohort analyses stratified patients according to whether they were taking any cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, at baseline. That was where some differences did emerge.

The first compared the entire 4-mg cohort to the subset of patients taking 100 mg as monotherapy (absent any symptomatic medications). Both the 100-mg and 4-mg groups declined linearly on all measures, but compared to the 4 mg group the 100 mg group experienced about a 3-point benefit on both the ADAS-cog and ADS-ADL measures.* The 100-mg group also experienced significantly more dropouts (45% vs. 23%), with 16% of those being due to adverse events.

The second analysis compared the two 4-mg groups: those taking LMTM as monotherapy and those taking it in combination with standard AD medications. Again, both groups declined, but that decline was attenuated in the monotherapy group, with a 4-point advantage in the ADAS-cog and nearly a 5-point advantage in the ADS-ADL. The 3-cc ventricular volume advantage was seen as well.

Again, Dr. Schneider said, these results were recapitulated in the secondary endpoints, which he did not show.

The trial seems to upend TauRx’s earlier firm contention that the previously tested higher doses slow cognitive and functional decline – a view Dr. Wischik clung to after the July data were released. Dr. Schneider attempted to address this by suggesting that “the 4-mg dose may not have been as inactive as the developer thought.”

However, he noted, another possibility is that the patients who took the 4-mg dose but not the symptomatic drugs “may have had a more benign course of disease, compared to those taking cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.”

This new study has now aroused the same criticism levied last summer. Maria Carrillo, PhD, chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, was blunt in her assessment.

“The results of post hoc analyses, even when preplanned, are not valid and could be spurious,” she said. “They may mean nothing. As a field, we have been lured into rabbit holes in the past due to post hoc analyses and wasted too much time and way too much money. Of course, companies can do what they want as next steps in trials if they have the financial backing to do so.”

Dr. Wischik, however, said both the July data and the new data clearly justify taking the 4-mg dose forward in a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

“It’s really very exciting that we got exactly the same results now as we did in the post-hoc analysis [of the July data],” he said in an interview. “We predicted these results based on what we saw, we changed the statistical analysis, and we got the predicted results. This has nothing to do with data scouring.”

The question of whether the monotherapy patients are fundamentally different from those taking standard AD drugs is a valid one, he admitted. “We can’t avoid that criticism until we do another study where people who are not on any AD treatment are randomized.”

Dr. Wischik was then asked whether it would be difficult to recruit an entire cohort of patients with mild Alzheimer’s who are willing to forego approved symptomatic medications while in such a study. He did not think that would be problematic.

“Twenty percent of our cohort was already in that slot,” he said. “This practice pattern is determined somewhat by geography and somewhat by the type of clinician treating the patient. People also go on the drugs and then come off for various reasons. But even in the U.S., only 55% of Alzheimer’s patients are taking them.”

Dr. Wischik didn’t mention the problem of finding an appropriate placebo for such a study. If indeed the 4-mg dose is biologically active, such a placebo would have to be demonstrably inert, as well as provide the appropriate urine color to keep the blinding unbroken.

“That’s a challenge,” Dr. Schneider said.

Dr. Schneider was a coinvestigator on the LMTM phase III program. He has disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Correction, 12/12/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the results of this study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

SAN DIEGO – An anti-tau compound that has stirred scientific controversy for 8 years will continue along its developmental pathway at a much lower dose, despite yet another study that has Alzheimer’s researchers scratching their heads.

The drug, dubbed LMTM, is a derivative of the dye methylene blue. Its most recent phase III study, reported at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, found that 100 mg twice a day conferred no cognitive or functional benefit upon patients with mild AD, compared with a control dose of 4 mg.

Some significant differences, however, did emerge in two prespecified subanalyses of the 4-mg control group. Patients who took the low dose, intended to be a placebo comparator, did better than those on the high dose – but only if they were not taking any standard symptomatic AD medications.

Based on these findings, TauRx, which is developing LMTM, will abandon the 100-mg dose and refocus on the 4-mg dose, said Claude Wischik, MD, chairman and chief executive officer of the Singapore-based company.

“I think it looks effective and there’s no advantage to going to a higher dose,” Dr. Wischik said in an interview. “The 100-mg dose doesn’t offer anything above the 4-mg dose, and we saw more dropouts in the higher-dose group. We will go forward with a new trial using 4 mg.”

The new commitment to 4 mg turns LMTM’s prior development trajectory on its head, as nothing lower than 75 mg has been investigated in a phase III study. The 4-mg control dose was used as a placebo stand-in, since LMTM colors urine blue or green. The low dose was considered biologically inactive and used to maintain the study blind.

Dr. Wischik has been investigating LMTM as a tau anti-aggregant for 10 years, first publicly reporting clinical data in 2008. LMTM has never posted significant cognitive or functional benefits in any primary analysis. Instead, it has moved forward based on a series of subanalyses that showed significant or near-significant benefits in smaller, meticulously constructed subgroups – conclusions that critics have called questionable at best. The most recent of these examined the drug’s effect in patients with mild to moderate disease and was presented last July at the Alzheimer’s Association’s International Conference (AAIC).

That study also didn’t meet its primary endpoints in the overall cohort of 891 patients, but TauRx promoted it as “promising,” based on a subgroup analysis of the 15% of patients who were not taking memantine or cholinesterase inhibitors.

Among these patients, those taking 75 mg twice daily declined 6 points less on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) than those taking 4 mg. Those taking 125 mg twice daily declined 6 points less than the 4-mg group. On the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL), patients taking 75 mg twice daily scored 6.5 points higher than did the placebo group, indicating better function, and those taking 125 mg twice daily scored 7 points higher than did the placebo group.

At AAIC, researchers suggested that the monotherapy groups could have had a less aggressive disease course, or might not have had Alzheimer’s disease at all. Others complained about the unorthodox grouping of control patients in the subgroup analysis.

It was after digesting these data that TauRx investigators changed the statistical analysis of the current study, then in its final months, from a randomized trial to a cohort analysis. This was done before data lockdown, but it was still a dramatic shift from the original study design.

“The primary analysis was changed to essentially analyze this as a cohort study,” said Lon Schneider, MD, who presented the results at CTAD. “The comparisons of interest were patients taking 100 mg twice a day who were not on [symptomatic treatment], compared to the original control group of 4 mg. The other comparison was the 4-mg group not on cholinesterase inhibitors to the 4-mg group that was on them.”

The 18-month trial randomized 800 patients with mild AD to 100 mg LMTM twice daily or to 4 mg twice daily. Patients were drawn from two global regions: Canada and the United States, and eastern Europe and Australia.

The study group was a typical one, with a mean age of 70 years and a mean Mini Mental State Exam score of 22. The mean ADAS-cog score was 17. Most (80%) were taking a cholinesterase inhibitor, memantine, or both; 20% were naive to these medications.

Primary endpoints were the ADAS-cog11, ADCS-ADL, and left ventricular volume. Secondary outcomes included the Mini Mental State Exam and Neuropsychiatric Index.

In the primary analysis as the trial was created and conducted, LMTM 100 mg/twice daily did not confer any benefit, compared with the control 4-mg dose. The decline curves were virtually superimposable in the ADAS-cog score, ADCS-ADL score, and in loss of left ventricular volume.

This same nonsignificant pattern occurred in all the secondary endpoints, which Dr. Schneider did not show.

The cohort analyses stratified patients according to whether they were taking any cholinesterase inhibitor or memantine, or both, at baseline. That was where some differences did emerge.

The first compared the entire 4-mg cohort to the subset of patients taking 100 mg as monotherapy (absent any symptomatic medications). Both the 100-mg and 4-mg groups declined linearly on all measures, but compared to the 4 mg group the 100 mg group experienced about a 3-point benefit on both the ADAS-cog and ADS-ADL measures.* The 100-mg group also experienced significantly more dropouts (45% vs. 23%), with 16% of those being due to adverse events.

The second analysis compared the two 4-mg groups: those taking LMTM as monotherapy and those taking it in combination with standard AD medications. Again, both groups declined, but that decline was attenuated in the monotherapy group, with a 4-point advantage in the ADAS-cog and nearly a 5-point advantage in the ADS-ADL. The 3-cc ventricular volume advantage was seen as well.

Again, Dr. Schneider said, these results were recapitulated in the secondary endpoints, which he did not show.

The trial seems to upend TauRx’s earlier firm contention that the previously tested higher doses slow cognitive and functional decline – a view Dr. Wischik clung to after the July data were released. Dr. Schneider attempted to address this by suggesting that “the 4-mg dose may not have been as inactive as the developer thought.”

However, he noted, another possibility is that the patients who took the 4-mg dose but not the symptomatic drugs “may have had a more benign course of disease, compared to those taking cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine.”

This new study has now aroused the same criticism levied last summer. Maria Carrillo, PhD, chief scientific officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, was blunt in her assessment.

“The results of post hoc analyses, even when preplanned, are not valid and could be spurious,” she said. “They may mean nothing. As a field, we have been lured into rabbit holes in the past due to post hoc analyses and wasted too much time and way too much money. Of course, companies can do what they want as next steps in trials if they have the financial backing to do so.”

Dr. Wischik, however, said both the July data and the new data clearly justify taking the 4-mg dose forward in a randomized, placebo-controlled study.

“It’s really very exciting that we got exactly the same results now as we did in the post-hoc analysis [of the July data],” he said in an interview. “We predicted these results based on what we saw, we changed the statistical analysis, and we got the predicted results. This has nothing to do with data scouring.”

The question of whether the monotherapy patients are fundamentally different from those taking standard AD drugs is a valid one, he admitted. “We can’t avoid that criticism until we do another study where people who are not on any AD treatment are randomized.”

Dr. Wischik was then asked whether it would be difficult to recruit an entire cohort of patients with mild Alzheimer’s who are willing to forego approved symptomatic medications while in such a study. He did not think that would be problematic.

“Twenty percent of our cohort was already in that slot,” he said. “This practice pattern is determined somewhat by geography and somewhat by the type of clinician treating the patient. People also go on the drugs and then come off for various reasons. But even in the U.S., only 55% of Alzheimer’s patients are taking them.”

Dr. Wischik didn’t mention the problem of finding an appropriate placebo for such a study. If indeed the 4-mg dose is biologically active, such a placebo would have to be demonstrably inert, as well as provide the appropriate urine color to keep the blinding unbroken.

“That’s a challenge,” Dr. Schneider said.

Dr. Schneider was a coinvestigator on the LMTM phase III program. He has disclosed financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Correction, 12/12/16: An earlier version of this article misstated the results of this study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT CTAD

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After saying that the placebo dose of drug effected cognitive and clinical benefit in a cohort analysis comparing it to 100 mg twice daily, the company will further develop LMTM in a 4-mg dose.

Data source: The cohort analysis involved 891 patients with mild Alzheimer’s.

Disclosures: Dr. Wischik is the founder and president of Singapore-based TauRx. Dr. Schneider is an investigator in the drug’s phase III trial and has reported financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

Thinking Outside the DRG Box

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

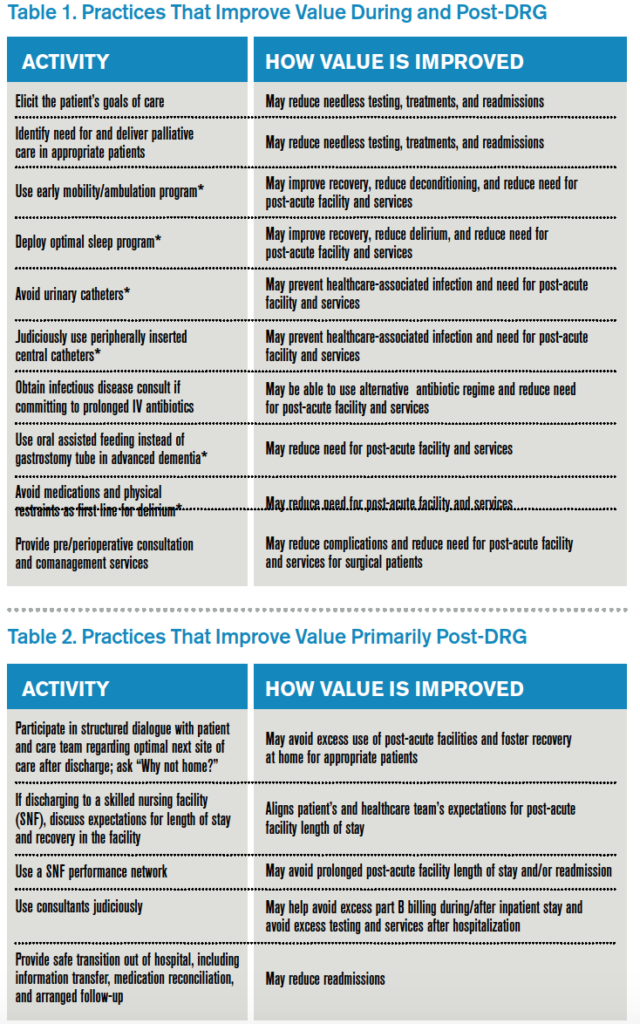

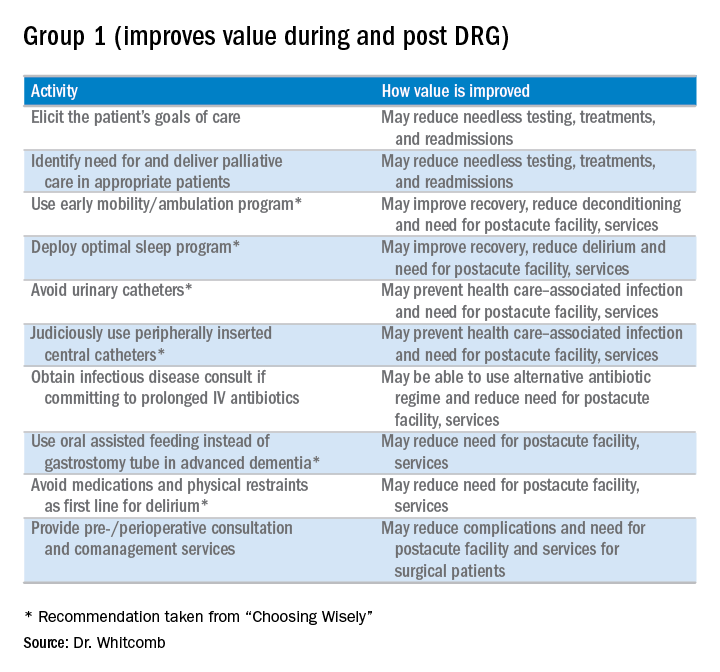

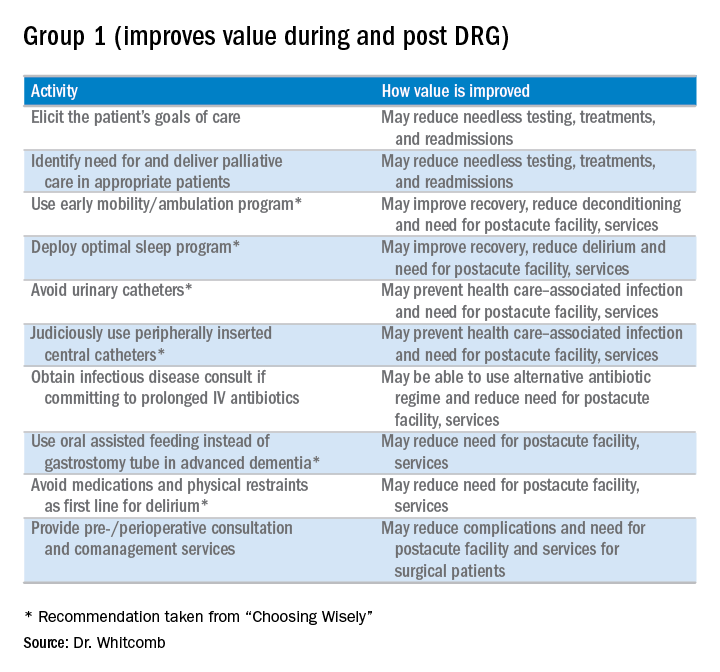

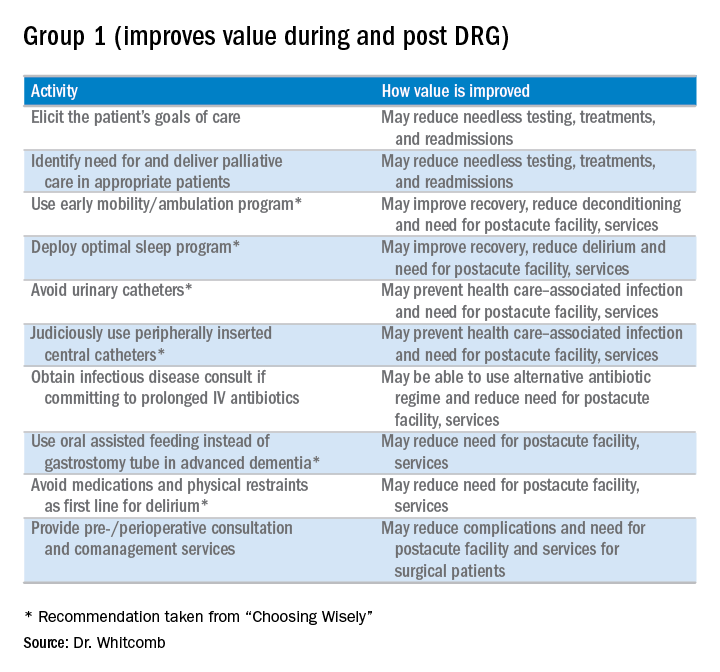

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

Agent exhibits activity in relapsed/refractory AML

acute myeloid leukemia

SAN DIEGO—A next-generation DNA hypomethylating agent has demonstrated clinical activity and an acceptable safety profile in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The agent, guadecitabine, produced a composite complete response (CRc) rate of 23% in a phase 2 study.

CRc was observed in all patient subgroups and was associated with longer survival, regardless of whether patients went on to receive a transplant.

Based on these results, researchers are initiating a phase 3 trial of the drug in relapsed/refractory AML.

Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, presented the phase 2 results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 904). The study was sponsored by Astex Pharmaceuticals.

Guadecitabine (formerly SGI-110) is a hypomethylating dinucleotide of decitabine and deoxyguanosine that is resistant to cytidine deaminase degradation. It is administered as a small volume subcutaneous injection, which results in extended decitabine exposure.

“Rapid metabolization, elimination shortens the in vivo exposure and may limit the efficacy of decitabine,” Dr Daver noted. “Guadecitabine was engineered to improve the in vivo levels . . . and the efficacy of decitabine by blocking the rapid elimination.”

In the phase 2 trial, Dr Daver and his colleagues investigated guadecitabine in 103 patients with relapsed/refractory AML. The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 22-82), and 60% were male. Eighty-six percent of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0-1, and 41% had poor-risk cytogenetics.

The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-7). All patients had received prior chemotherapy, 85% had received prior induction with 7+3 (a continuous infusion of cytarabine for 7 days plus daunorubicin for 3 days), and 18% had a prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Fifty-three percent of patients had a CR to first induction, and 47% were primary refractory.

Treatment

The researchers tested 2 different doses and schedules of guadecitabine. In the first cohort (5-day regimen), 50 patients were randomized (1:1) to either 60 mg/m2/day (n=24) or 90 mg/m2/day (n=26) on days 1-5.

In the second cohort (10-day regimen), 53 patients were assigned to treatment with 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 and days 8-12 for up to 4 cycles, followed by 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 in subsequent cycles.

Cycles were scheduled every 28 days for both regimens. Dose reductions and delays were allowed based on response and tolerability. And patients remained on treatment as long as they continued to benefit without unacceptable toxicity.

Response

The study’s primary endpoint was the CRc rate, which consisted of CR plus CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp) plus CR with incomplete neutrophil recovery (CRi).

The CRc rate was 16% in the 5-day cohort and 30% in the 10-day cohort. The CR rate was 6% and 19%, respectively. The CRp rate was 2% and 7%, respectively. And the CRi rate was 8% and 4%, respectively.

There was a trend toward a higher CR/CRc rate with the 10-day regimen (P=0.074 and 0.106, respectively).

There was no significant difference in CRc according to patient age (65 and older vs younger than 65), cytogenetics, prior HSCT, response to induction, or time from last therapy (less than 6 months vs 6 months or more).

However, the CRc rate was significantly lower for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 than for those with a status of 0-1 (P<0.001).

Survival

For the entire study cohort, the median overall survival (OS) was 6.6 months, the 1-year OS was 28%, and the 2-year OS was 19%.

The median OS was 7.1 months with the 10-day regimen and 5.7 months with the 5-day regimen. This difference was not significant (P=0.51).

The median OS was not reached for patients who achieved a CR or for those who achieved a CRp plus a CRi. For patients who did not achieve a CRc, the median OS was 5.6 months (P<0.01).

The median OS was not reached for patients who had a CRc, whether or not they received a subsequent HSCT. There was no significant difference between patients who received an HSCT post-guadecitabine and those who did not (P=0.87).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS according to patient age, prior HSCT, or response to induction.

However, OS was significantly worse for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 (P<0.001), those with poor-risk cytogenetics (P<0.001), and those for whom 6 months or more had elapsed since their last therapy (P=0.015).

Safety

Common grade 3 or higher adverse events (regardless of the relationship to therapy) were febrile neutropenia (60%), pneumonia (36%), thrombocytopenia (36%), anemia (31%), neutropenia (19%), and sepsis (16%).

The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%, and the 60-day mortality rate was 11.7%. ![]()

acute myeloid leukemia

SAN DIEGO—A next-generation DNA hypomethylating agent has demonstrated clinical activity and an acceptable safety profile in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The agent, guadecitabine, produced a composite complete response (CRc) rate of 23% in a phase 2 study.

CRc was observed in all patient subgroups and was associated with longer survival, regardless of whether patients went on to receive a transplant.

Based on these results, researchers are initiating a phase 3 trial of the drug in relapsed/refractory AML.

Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, presented the phase 2 results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 904). The study was sponsored by Astex Pharmaceuticals.

Guadecitabine (formerly SGI-110) is a hypomethylating dinucleotide of decitabine and deoxyguanosine that is resistant to cytidine deaminase degradation. It is administered as a small volume subcutaneous injection, which results in extended decitabine exposure.

“Rapid metabolization, elimination shortens the in vivo exposure and may limit the efficacy of decitabine,” Dr Daver noted. “Guadecitabine was engineered to improve the in vivo levels . . . and the efficacy of decitabine by blocking the rapid elimination.”

In the phase 2 trial, Dr Daver and his colleagues investigated guadecitabine in 103 patients with relapsed/refractory AML. The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 22-82), and 60% were male. Eighty-six percent of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0-1, and 41% had poor-risk cytogenetics.

The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-7). All patients had received prior chemotherapy, 85% had received prior induction with 7+3 (a continuous infusion of cytarabine for 7 days plus daunorubicin for 3 days), and 18% had a prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Fifty-three percent of patients had a CR to first induction, and 47% were primary refractory.

Treatment

The researchers tested 2 different doses and schedules of guadecitabine. In the first cohort (5-day regimen), 50 patients were randomized (1:1) to either 60 mg/m2/day (n=24) or 90 mg/m2/day (n=26) on days 1-5.

In the second cohort (10-day regimen), 53 patients were assigned to treatment with 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 and days 8-12 for up to 4 cycles, followed by 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 in subsequent cycles.

Cycles were scheduled every 28 days for both regimens. Dose reductions and delays were allowed based on response and tolerability. And patients remained on treatment as long as they continued to benefit without unacceptable toxicity.

Response

The study’s primary endpoint was the CRc rate, which consisted of CR plus CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp) plus CR with incomplete neutrophil recovery (CRi).

The CRc rate was 16% in the 5-day cohort and 30% in the 10-day cohort. The CR rate was 6% and 19%, respectively. The CRp rate was 2% and 7%, respectively. And the CRi rate was 8% and 4%, respectively.

There was a trend toward a higher CR/CRc rate with the 10-day regimen (P=0.074 and 0.106, respectively).

There was no significant difference in CRc according to patient age (65 and older vs younger than 65), cytogenetics, prior HSCT, response to induction, or time from last therapy (less than 6 months vs 6 months or more).

However, the CRc rate was significantly lower for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 than for those with a status of 0-1 (P<0.001).

Survival

For the entire study cohort, the median overall survival (OS) was 6.6 months, the 1-year OS was 28%, and the 2-year OS was 19%.

The median OS was 7.1 months with the 10-day regimen and 5.7 months with the 5-day regimen. This difference was not significant (P=0.51).

The median OS was not reached for patients who achieved a CR or for those who achieved a CRp plus a CRi. For patients who did not achieve a CRc, the median OS was 5.6 months (P<0.01).

The median OS was not reached for patients who had a CRc, whether or not they received a subsequent HSCT. There was no significant difference between patients who received an HSCT post-guadecitabine and those who did not (P=0.87).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS according to patient age, prior HSCT, or response to induction.

However, OS was significantly worse for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 (P<0.001), those with poor-risk cytogenetics (P<0.001), and those for whom 6 months or more had elapsed since their last therapy (P=0.015).

Safety

Common grade 3 or higher adverse events (regardless of the relationship to therapy) were febrile neutropenia (60%), pneumonia (36%), thrombocytopenia (36%), anemia (31%), neutropenia (19%), and sepsis (16%).

The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%, and the 60-day mortality rate was 11.7%. ![]()

acute myeloid leukemia

SAN DIEGO—A next-generation DNA hypomethylating agent has demonstrated clinical activity and an acceptable safety profile in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The agent, guadecitabine, produced a composite complete response (CRc) rate of 23% in a phase 2 study.

CRc was observed in all patient subgroups and was associated with longer survival, regardless of whether patients went on to receive a transplant.

Based on these results, researchers are initiating a phase 3 trial of the drug in relapsed/refractory AML.

Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, presented the phase 2 results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 904). The study was sponsored by Astex Pharmaceuticals.

Guadecitabine (formerly SGI-110) is a hypomethylating dinucleotide of decitabine and deoxyguanosine that is resistant to cytidine deaminase degradation. It is administered as a small volume subcutaneous injection, which results in extended decitabine exposure.

“Rapid metabolization, elimination shortens the in vivo exposure and may limit the efficacy of decitabine,” Dr Daver noted. “Guadecitabine was engineered to improve the in vivo levels . . . and the efficacy of decitabine by blocking the rapid elimination.”

In the phase 2 trial, Dr Daver and his colleagues investigated guadecitabine in 103 patients with relapsed/refractory AML. The patients’ median age was 60 (range, 22-82), and 60% were male. Eighty-six percent of patients had an ECOG performance status of 0-1, and 41% had poor-risk cytogenetics.

The median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1-7). All patients had received prior chemotherapy, 85% had received prior induction with 7+3 (a continuous infusion of cytarabine for 7 days plus daunorubicin for 3 days), and 18% had a prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Fifty-three percent of patients had a CR to first induction, and 47% were primary refractory.

Treatment

The researchers tested 2 different doses and schedules of guadecitabine. In the first cohort (5-day regimen), 50 patients were randomized (1:1) to either 60 mg/m2/day (n=24) or 90 mg/m2/day (n=26) on days 1-5.

In the second cohort (10-day regimen), 53 patients were assigned to treatment with 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 and days 8-12 for up to 4 cycles, followed by 60 mg/m2/day on days 1-5 in subsequent cycles.

Cycles were scheduled every 28 days for both regimens. Dose reductions and delays were allowed based on response and tolerability. And patients remained on treatment as long as they continued to benefit without unacceptable toxicity.

Response

The study’s primary endpoint was the CRc rate, which consisted of CR plus CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp) plus CR with incomplete neutrophil recovery (CRi).

The CRc rate was 16% in the 5-day cohort and 30% in the 10-day cohort. The CR rate was 6% and 19%, respectively. The CRp rate was 2% and 7%, respectively. And the CRi rate was 8% and 4%, respectively.

There was a trend toward a higher CR/CRc rate with the 10-day regimen (P=0.074 and 0.106, respectively).

There was no significant difference in CRc according to patient age (65 and older vs younger than 65), cytogenetics, prior HSCT, response to induction, or time from last therapy (less than 6 months vs 6 months or more).

However, the CRc rate was significantly lower for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 than for those with a status of 0-1 (P<0.001).

Survival

For the entire study cohort, the median overall survival (OS) was 6.6 months, the 1-year OS was 28%, and the 2-year OS was 19%.

The median OS was 7.1 months with the 10-day regimen and 5.7 months with the 5-day regimen. This difference was not significant (P=0.51).

The median OS was not reached for patients who achieved a CR or for those who achieved a CRp plus a CRi. For patients who did not achieve a CRc, the median OS was 5.6 months (P<0.01).

The median OS was not reached for patients who had a CRc, whether or not they received a subsequent HSCT. There was no significant difference between patients who received an HSCT post-guadecitabine and those who did not (P=0.87).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in OS according to patient age, prior HSCT, or response to induction.

However, OS was significantly worse for patients with an ECOG performance status of 2 (P<0.001), those with poor-risk cytogenetics (P<0.001), and those for whom 6 months or more had elapsed since their last therapy (P=0.015).

Safety

Common grade 3 or higher adverse events (regardless of the relationship to therapy) were febrile neutropenia (60%), pneumonia (36%), thrombocytopenia (36%), anemia (31%), neutropenia (19%), and sepsis (16%).

The 30-day mortality rate was 3.9%, and the 60-day mortality rate was 11.7%. ![]()

After full data release, experts say failed Alzheimer’s trial EXPEDITION 3 offers hopeful signals

SAN DIEGO – Solanezumab may have not have slowed the relentless march of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but it was a valuable proving ground of the amyloid hypothesis, experts said during a wide-ranging discussion of Lilly’s failed EXPEDITION 3 trial.

Lilly representatives and EXPEDITION investigators released the study’s full results at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer ’s disease meeting. – findings that should be read as tremendously encouraging rather than a defeat, according to Paul Aisen, MD, director of the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“We have here a negative study that confirms a beneficial treatment,” said Dr. Aisen, who was also an EXPEDITION 3 investigator. “We have a treatment that engages its target, binds to soluble amyloid, and, by virtue of that mechanism, is slowing cognitive and functional decline,” not only in EXPEDITION 3, but in its predecessors EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION 2.

“This is not a refutation of the amyloid hypothesis but a confirmation of it.”

Nevertheless, the trial must be read as a failed one, he admitted. There was no statistically significant separation between solanezumab and placebo on the ADAS-Cog14, a combined assessment of cognition and function that was the study’s primary endpoint. The active group experienced 11% less cognitive decline than did the placebo group, but the p-value remained tantalizingly below the level of significance, at 0.095.

“But what if solanezumab had hit at 0.05 instead of 0.095?” Dr. Aisen asked. “In fact, it would still be a small effect size,” which would have thrown into question the drug’s clinical utility. “Going into this, we thought we might see a 30% slowing of decline on the ADAS-Cog, and it was disappointing to only get 11%. But that is also what we saw on the key secondaries. Overall the effect size looks to be about 12%-13%, and that’s just too small.”

EXPEDITION 3 was the last of a triad of solanezumab studies, all of which posted intriguing signals of cognitive and functional benefit in patients with mild-moderate AD. It was based on subgroup analyses of EXPEDITION 1 and 2, both of which failed to meet their primary endpoints. But when researchers pooled the mild patients from both studies, they found that solanezumab was associated with a 34% slowing of cognitive decline on the ADAS-Cog14. This translated to a clinical change of less than 2 points on the scale, however.

Lilly very carefully drafted EXPEDITION 3 to come as close to recreating those findings as possible but still stumbled over results that were numerically positive for the antibody but not statistically significant or clinically meaningful.

Lawrence S. Honig, MD, professor of neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y., and principal investigator of the EXPEDITION 3 study, presented the study’s full results to a packed audience on Dec. 8.

The study comprised about 2,000 patients with imaging-confirmed amyloid brain plaques and mild-moderate AD. They were randomized to placebo or monthly injections of 400 mg solanezumab for 80 weeks. The global study was conducted in 11 countries and 210 study sites.

Dr. Honig detailed the key secondary endpoints of cognition and function, and also revealed biomarker data.

While the ADAS-Cog failed to meet statistical significance, changes in the Mini Mental State Exam score did, with a 13% slowing of decline compared to placebo (P = .014). There was also a significant 5% difference in the Clinical Dementia Rating scale-sum of boxes test (P = .004).

Outcomes were mixed in measures of function. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) and its related measure, the ADCS-ADL inventory instrumental items, posted significant results with 15% and 14% differences, respectively, relative to placebo (P = .009 and .019, respectively).

But results on the Functional Activities Questionnaire, an informant measure of more complex activities, were not significant, with only a 7% separation from placebo and a P value of .140.

Biomarkers trended the right way, Dr. Honig noted. Solanezumab did what it was supposed to: bind soluble amyloid beta. This resulted in a 500- to 800-fold increase in the protein in plasma relative to placebo. There were no changes in amyloid brain plaques as measured by PET imaging, but this was no surprise, Dr. Aisen said, since the antibody doesn’t recognize fibrillar amyloid.

“What we expect to see with biomarkers differs based on the epitope targeted. Solanezumab ignores plaques. It targets the middle of the peptide, binding to soluble AB. Now how that helps AD is something of a debate, but it is important tor recognize that it does not attack plaques. Instead, by tying up monomeric AB, it may change the dynamic exchange of various species of amyloid around plaques; the toxicity of amyloid is thought to reside as much in oligomeric species as in the fibrillar deposits. I see this [plasma AB increase] as confirming that it’s tying up monomeric amyloid species and that the result is a slowing of disease progression. I believe it is supportive of the amyloid hypothesis.”

Solanezumab had no significant effect on tau, either in cerebrospinal fluid or imaging, nor did it change the progression of ventricular enlargement, a marker of whole brain atrophy.

The antibody was quite safe, with 17% of patient reporting an adverse event, compared to 19% of placebo patients. There were 9 deaths in the solanezumab arm and 16 in the placebo arm; about 4% of each group discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

Although the data discussion was framed in the most hopeful light possible, no one on the panel attempted to massage it into a more clinically positive form. On a webcast in late November, Eric Siemers, MD, senior medical director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Global Development Team at Eli Lilly, said the company was disappointed but would not bring solanezumab forward for approval for mild or moderate AD patients. He echoed that sentiment during the panel discussion.

“We didn’t expect this to be a cure for this disease, but we did hope it would be the first drug to slow its progress. So yes, we are very disappointed.”

He and Dr. Aisen confirmed, however, that two other trials using solanezumab in a different population will go forward uninterrupted. The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study (A4 study) is investigating its effect in cognitively health elders with Alzheimer’s risk factors, and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN) study of patients with autosomal dominant mutations in Alzheimer’s genes.

There was also brief discussion of dosing. Some audience members suggested that a higher dose than EXPEDITION’s 400 mg might have bumped up efficacy, and asked if Lilly would reconsider the dosing schedule in the A4 and DIAN studies.

“There has been a lot of discussion around that,” said Dr. Siemers. “But it’s not as easy and straightforward as you think.”

Nevertheless, Dr. Aisen is excited about solanezumab’s potential in these trials that target the disease at its earliest phase, even before cognitive symptoms develop. “I expect all antiamyloid treatments would work better when neurodegeneration is not extensive. Any of the antiamyloid antibodies would theoretically be more effective at a preclinical stage of AD than even in the mild dementia stage.”

Maria Carrillo, PhD, chief science officer of the Alzheimer’s Association, said that EXPEDITION 3 is far from a path to nowhere. Instead, she urged the research community, patients, and families to double down on their commitment to tackling the disease.

“These results stress the urgency for pushing forward harder. This is not a time to slow down. It’s a time to ramp up our efforts. This is not the time to sit back and say, ‘The amyloid hypothesis has been the wrong pathway and we need to drop it.’ But we also need to pursue other pathways, to broaden our approach and to broaden the armamentarium our clinicians will need to combat this disease.”

“This is not a win, true. But it gets us a little closer to one.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for mild Alzheimer’s disease patients, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post-hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post-hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of mild AD patients in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary endpoints reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, is the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. He has no financial disclosures.

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for mild Alzheimer’s disease patients, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post-hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post-hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of mild AD patients in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary endpoints reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, is the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. He has no financial disclosures.

This new phase III trial of solanezumab reveals that the drug is not effective for mild Alzheimer’s disease patients, despite the hint that it was possibly effective based on post-hoc analyses of earlier studies with this drug.

The findings expose the hazards of such post-hoc analyses, typically done when the desired results are not observed, in the hope of squeezing lemonade from lemons. Although the subanalysis of mild AD patients in the earlier studies suggested a 34% slowing of cognitive decline as assessed by ADAS-Cog, an incremental slowing of 11% was seen in the new study that was not even statistically significant. While some secondary endpoints reached statistical significance, the slowing was so modest as to make no practical difference clinically.

The combination of all these clinical trial failures with the result of imaging studies that have shown amyloid deposition some 20 years before the expected onset of symptoms clearly tells us that antiamyloid agents should only be considered as potential prophylactics. By the time symptoms appear, disease progression is largely independent of amyloid and may be primarily tau-driven, spreading from neuron to neuron even when amyloid is effectively targeted by therapeutics. Even the A4 and DIAN studies are likely initiating treatment too late to make anything more than a modest effect with little practical value clinically. I am not suggesting that we drop amyloid as a target, only that we stop making these incremental changes in clinical trial design in the hope of getting a different result.

Michael S. Wolfe, PhD, is the Mathias P. Mertes Professor of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Kansas, Lawrence. He has no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Solanezumab may have not have slowed the relentless march of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but it was a valuable proving ground of the amyloid hypothesis, experts said during a wide-ranging discussion of Lilly’s failed EXPEDITION 3 trial.

Lilly representatives and EXPEDITION investigators released the study’s full results at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer ’s disease meeting. – findings that should be read as tremendously encouraging rather than a defeat, according to Paul Aisen, MD, director of the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“We have here a negative study that confirms a beneficial treatment,” said Dr. Aisen, who was also an EXPEDITION 3 investigator. “We have a treatment that engages its target, binds to soluble amyloid, and, by virtue of that mechanism, is slowing cognitive and functional decline,” not only in EXPEDITION 3, but in its predecessors EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION 2.

“This is not a refutation of the amyloid hypothesis but a confirmation of it.”

Nevertheless, the trial must be read as a failed one, he admitted. There was no statistically significant separation between solanezumab and placebo on the ADAS-Cog14, a combined assessment of cognition and function that was the study’s primary endpoint. The active group experienced 11% less cognitive decline than did the placebo group, but the p-value remained tantalizingly below the level of significance, at 0.095.

“But what if solanezumab had hit at 0.05 instead of 0.095?” Dr. Aisen asked. “In fact, it would still be a small effect size,” which would have thrown into question the drug’s clinical utility. “Going into this, we thought we might see a 30% slowing of decline on the ADAS-Cog, and it was disappointing to only get 11%. But that is also what we saw on the key secondaries. Overall the effect size looks to be about 12%-13%, and that’s just too small.”

EXPEDITION 3 was the last of a triad of solanezumab studies, all of which posted intriguing signals of cognitive and functional benefit in patients with mild-moderate AD. It was based on subgroup analyses of EXPEDITION 1 and 2, both of which failed to meet their primary endpoints. But when researchers pooled the mild patients from both studies, they found that solanezumab was associated with a 34% slowing of cognitive decline on the ADAS-Cog14. This translated to a clinical change of less than 2 points on the scale, however.

Lilly very carefully drafted EXPEDITION 3 to come as close to recreating those findings as possible but still stumbled over results that were numerically positive for the antibody but not statistically significant or clinically meaningful.

Lawrence S. Honig, MD, professor of neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, N.Y., and principal investigator of the EXPEDITION 3 study, presented the study’s full results to a packed audience on Dec. 8.

The study comprised about 2,000 patients with imaging-confirmed amyloid brain plaques and mild-moderate AD. They were randomized to placebo or monthly injections of 400 mg solanezumab for 80 weeks. The global study was conducted in 11 countries and 210 study sites.

Dr. Honig detailed the key secondary endpoints of cognition and function, and also revealed biomarker data.

While the ADAS-Cog failed to meet statistical significance, changes in the Mini Mental State Exam score did, with a 13% slowing of decline compared to placebo (P = .014). There was also a significant 5% difference in the Clinical Dementia Rating scale-sum of boxes test (P = .004).

Outcomes were mixed in measures of function. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study activities of daily living (ADCS-ADL) and its related measure, the ADCS-ADL inventory instrumental items, posted significant results with 15% and 14% differences, respectively, relative to placebo (P = .009 and .019, respectively).

But results on the Functional Activities Questionnaire, an informant measure of more complex activities, were not significant, with only a 7% separation from placebo and a P value of .140.

Biomarkers trended the right way, Dr. Honig noted. Solanezumab did what it was supposed to: bind soluble amyloid beta. This resulted in a 500- to 800-fold increase in the protein in plasma relative to placebo. There were no changes in amyloid brain plaques as measured by PET imaging, but this was no surprise, Dr. Aisen said, since the antibody doesn’t recognize fibrillar amyloid.

“What we expect to see with biomarkers differs based on the epitope targeted. Solanezumab ignores plaques. It targets the middle of the peptide, binding to soluble AB. Now how that helps AD is something of a debate, but it is important tor recognize that it does not attack plaques. Instead, by tying up monomeric AB, it may change the dynamic exchange of various species of amyloid around plaques; the toxicity of amyloid is thought to reside as much in oligomeric species as in the fibrillar deposits. I see this [plasma AB increase] as confirming that it’s tying up monomeric amyloid species and that the result is a slowing of disease progression. I believe it is supportive of the amyloid hypothesis.”

Solanezumab had no significant effect on tau, either in cerebrospinal fluid or imaging, nor did it change the progression of ventricular enlargement, a marker of whole brain atrophy.

The antibody was quite safe, with 17% of patient reporting an adverse event, compared to 19% of placebo patients. There were 9 deaths in the solanezumab arm and 16 in the placebo arm; about 4% of each group discontinued treatment because of an adverse event.

Although the data discussion was framed in the most hopeful light possible, no one on the panel attempted to massage it into a more clinically positive form. On a webcast in late November, Eric Siemers, MD, senior medical director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Global Development Team at Eli Lilly, said the company was disappointed but would not bring solanezumab forward for approval for mild or moderate AD patients. He echoed that sentiment during the panel discussion.

“We didn’t expect this to be a cure for this disease, but we did hope it would be the first drug to slow its progress. So yes, we are very disappointed.”

He and Dr. Aisen confirmed, however, that two other trials using solanezumab in a different population will go forward uninterrupted. The Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s study (A4 study) is investigating its effect in cognitively health elders with Alzheimer’s risk factors, and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network (DIAN) study of patients with autosomal dominant mutations in Alzheimer’s genes.

There was also brief discussion of dosing. Some audience members suggested that a higher dose than EXPEDITION’s 400 mg might have bumped up efficacy, and asked if Lilly would reconsider the dosing schedule in the A4 and DIAN studies.

“There has been a lot of discussion around that,” said Dr. Siemers. “But it’s not as easy and straightforward as you think.”