User login

Inhalers used incorrectly at least one-third of time

Clinical question: What are the most common errors in inhaler use over the past 40 years?

Background: One of the reasons for poor asthma and COPD control is incorrect inhaler use. Problems with technique have been recognized since the launch of the metered-dose inhaler (MDI) in the 1960s. Multiple initiatives have been implemented, including the design of the dry powder inhaler (DPI); however, problems persist despite all corrective measures.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Synopsis: The most frequent MDI errors were lack of initial full expiration (48%), inadequate coordination (45%), and no postinhalation breath hold (46%). DPI errors were lower, compared with MDI errors: incorrect preparation (29%), no initial full expiration before inhalation (46%), and no postinhalation breath hold (37%).

The overall prevalence of correct technique was the same as poor technique (31%). There was no difference in the rates of incorrect inhaler use between the first and second 20-year periods of investigation.

Bottom line: Incorrect inhaler use in patients with asthma and COPD persists over time despite multiple implemented strategies.

Citation: Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team. Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: has the patient technique improved over time? Chest. 2016;150(2):394-406.

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: What are the most common errors in inhaler use over the past 40 years?

Background: One of the reasons for poor asthma and COPD control is incorrect inhaler use. Problems with technique have been recognized since the launch of the metered-dose inhaler (MDI) in the 1960s. Multiple initiatives have been implemented, including the design of the dry powder inhaler (DPI); however, problems persist despite all corrective measures.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Synopsis: The most frequent MDI errors were lack of initial full expiration (48%), inadequate coordination (45%), and no postinhalation breath hold (46%). DPI errors were lower, compared with MDI errors: incorrect preparation (29%), no initial full expiration before inhalation (46%), and no postinhalation breath hold (37%).

The overall prevalence of correct technique was the same as poor technique (31%). There was no difference in the rates of incorrect inhaler use between the first and second 20-year periods of investigation.

Bottom line: Incorrect inhaler use in patients with asthma and COPD persists over time despite multiple implemented strategies.

Citation: Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team. Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: has the patient technique improved over time? Chest. 2016;150(2):394-406.

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: What are the most common errors in inhaler use over the past 40 years?

Background: One of the reasons for poor asthma and COPD control is incorrect inhaler use. Problems with technique have been recognized since the launch of the metered-dose inhaler (MDI) in the 1960s. Multiple initiatives have been implemented, including the design of the dry powder inhaler (DPI); however, problems persist despite all corrective measures.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Synopsis: The most frequent MDI errors were lack of initial full expiration (48%), inadequate coordination (45%), and no postinhalation breath hold (46%). DPI errors were lower, compared with MDI errors: incorrect preparation (29%), no initial full expiration before inhalation (46%), and no postinhalation breath hold (37%).

The overall prevalence of correct technique was the same as poor technique (31%). There was no difference in the rates of incorrect inhaler use between the first and second 20-year periods of investigation.

Bottom line: Incorrect inhaler use in patients with asthma and COPD persists over time despite multiple implemented strategies.

Citation: Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S, Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team. Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: has the patient technique improved over time? Chest. 2016;150(2):394-406.

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Blood thinning with bioprosthetic valves

Clinical question: Does anticoagulation prevent thromboembolic events in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation?

Background: The main advantage of bioprosthetic valves, compared with mechanical valves, is the avoidance of long-term anticoagulation. Current guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) during the first 3 months after surgery, which remains controversial. Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed no benefit of using VKA in the first 3 months; however, other studies have reported conflicting results.

Study design: Meta-analysis and systematic review.

Setting: Multicenter.

Synopsis: This meta-analysis included two RCTs and 12 observational studies that compared the outcomes in group I (VKA) versus group II (antiplatelet therapy/no treatment). There was no difference in thromboembolic events between group I (1%) and group II (1.5%), but there were more bleeding events in group I (2.6%) versus group II (1.1%). In addition, no differences in all-cause of mortality rate and need for redo surgery were found between the two groups.

Bottom line: The use of VKA in the first 3 months after a bioprosthetic valve implantation does not decrease the rate of thromboembolic events or mortality, but it is associated with increased risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Masri A, Gillinov M, Johnston DM, et al. Anticoagulation versus antiplatelet or no therapy in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print Aug. 3, 2016]. Heart. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309630

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Does anticoagulation prevent thromboembolic events in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation?

Background: The main advantage of bioprosthetic valves, compared with mechanical valves, is the avoidance of long-term anticoagulation. Current guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) during the first 3 months after surgery, which remains controversial. Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed no benefit of using VKA in the first 3 months; however, other studies have reported conflicting results.

Study design: Meta-analysis and systematic review.

Setting: Multicenter.

Synopsis: This meta-analysis included two RCTs and 12 observational studies that compared the outcomes in group I (VKA) versus group II (antiplatelet therapy/no treatment). There was no difference in thromboembolic events between group I (1%) and group II (1.5%), but there were more bleeding events in group I (2.6%) versus group II (1.1%). In addition, no differences in all-cause of mortality rate and need for redo surgery were found between the two groups.

Bottom line: The use of VKA in the first 3 months after a bioprosthetic valve implantation does not decrease the rate of thromboembolic events or mortality, but it is associated with increased risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Masri A, Gillinov M, Johnston DM, et al. Anticoagulation versus antiplatelet or no therapy in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print Aug. 3, 2016]. Heart. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309630

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Does anticoagulation prevent thromboembolic events in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation?

Background: The main advantage of bioprosthetic valves, compared with mechanical valves, is the avoidance of long-term anticoagulation. Current guidelines recommend the use of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) during the first 3 months after surgery, which remains controversial. Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed no benefit of using VKA in the first 3 months; however, other studies have reported conflicting results.

Study design: Meta-analysis and systematic review.

Setting: Multicenter.

Synopsis: This meta-analysis included two RCTs and 12 observational studies that compared the outcomes in group I (VKA) versus group II (antiplatelet therapy/no treatment). There was no difference in thromboembolic events between group I (1%) and group II (1.5%), but there were more bleeding events in group I (2.6%) versus group II (1.1%). In addition, no differences in all-cause of mortality rate and need for redo surgery were found between the two groups.

Bottom line: The use of VKA in the first 3 months after a bioprosthetic valve implantation does not decrease the rate of thromboembolic events or mortality, but it is associated with increased risk of major bleeding.

Citation: Masri A, Gillinov M, Johnston DM, et al. Anticoagulation versus antiplatelet or no therapy in patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print Aug. 3, 2016]. Heart. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309630

Dr. Florindez is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

The Barbershop Study: Hypertension causes nocturia

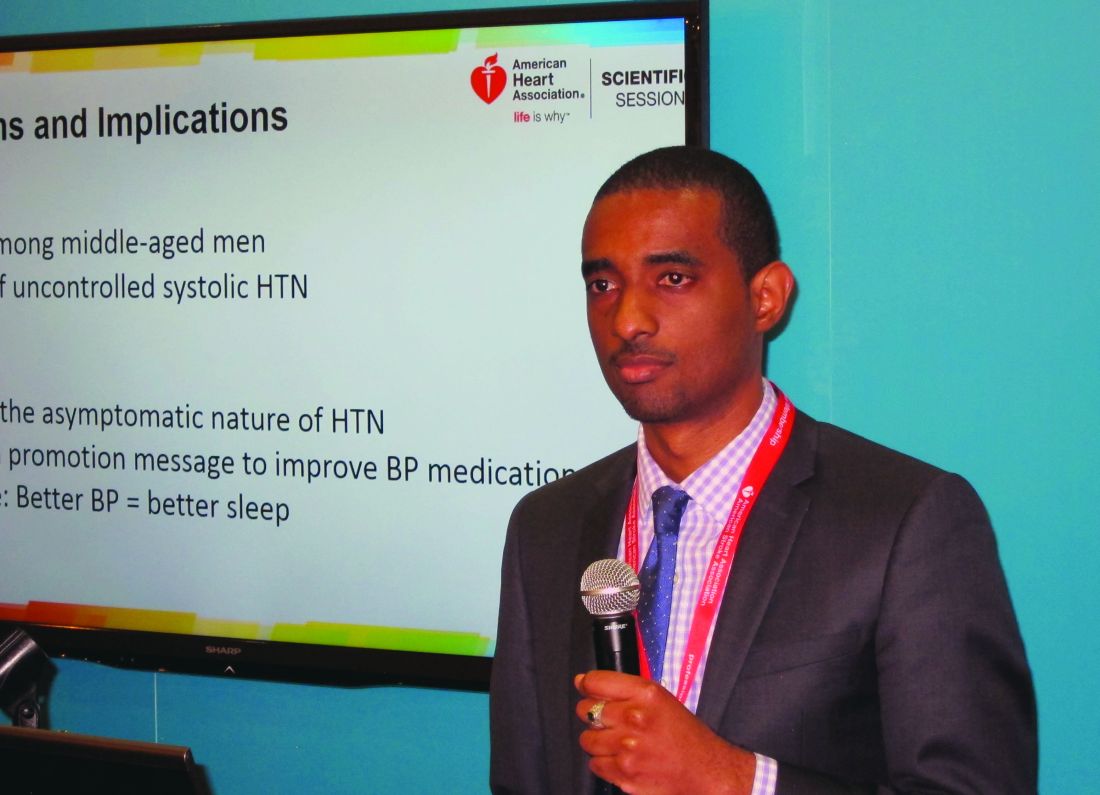

NEW ORLEANS – Uncontrolled systolic hypertension is a strong independent determinant of nocturia in middle-aged African American men, O’Neil Mason, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from the ongoing National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Barbershop Study challenges the traditional notion of hypertension as an asymptomatic disease. It also provides a novel health promotion message aimed at improving compliance with blood pressure medication.

The Barbershop Study is a hypertension intervention trial that’s being conducted in Los Angeles barbershops frequented by black men. In the initial screening phase for study eligibility, 2,577 African American men aged 35-79 years underwent highly accurate blood pressure measurements using an average of three readings taken via an oscillometric monitor.

The mean age of the men was 53 years. It was an obese group, with a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Fifty percent of the men had hypertension, and among that cohort fully one-third weren’t on antihypertensive medication and another 28% were treated but uncontrolled, with on-treatment blood pressures of 140/90 mm Hg or more. Thus, only 39% of these middle-aged African American men with high blood pressure were treated and controlled at baseline.

Seventy-seven percent of the screened men reported awakening once or more per night to urinate. A progressive increase in nocturia severity was seen with increasing systolic blood pressure. The prevalence of nocturia ranged from 68% among normotensive men to 91% among those with treated but uncontrolled hypertension, Dr. Mason reported.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for the standard risk factors for nocturia – including advancing age, an enlarged prostate, and diabetes, which was present in 16% of the men – stage 1 systolic hypertension in the range of 140-159 mm Hg was independently associated with a 1.57-fold increased likelihood of nocturia, compared with normotensive subjects. Stage 2 hypertension, with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more, was associated with a 2.32-fold increased risk; that’s in the same ballpark as having an enlarged prostate, which carried a 2.1-fold increased risk. Prehypertension – that is, a systolic pressure of 120-139 mm Hg – was associated with a nonsignificant 1.18-fold risk.

Diastolic blood pressure wasn’t an independent determinant of nocturia.

In a similar multivariate analysis focused on severe nocturia, defined as three or more episodes per night, stage 1 systolic hypertension was independently associated with a 2.29-fold increased risk, compared with normotension, and stage 2 systolic hypertension carried a 2.77-fold increased risk.

Audience members were clearly intrigued by this novel finding. They were quick to speculate as to potential underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, including atrial stretch, increased renal blood flow, or perhaps a side effect of diuretic therapy. However, Dr. Mason and his coinvestigators favor another possibility: “African Americans have more salt-sensitive hypertension and they have less nocturnal blood pressure dipping,” he noted. “So if nighttime blood pressure is high it could lead through increased pressure natriuresis to increased urine production. More activity in getting up to go to the bathroom increases the blood pressure and creates a cycle that begets more urine.”

Asked if uncontrolled systolic hypertension is also a determinant of nocturia in African American women, Dr. Mason replied that he would assume so. But that question hasn’t ever been studied. The Barbershop Study is restricted to African American men with hypertension because studies have shown they have a particularly low rate of controlled hypertension. In contrast, the controlled hypertension rate among hypertensive African American women is comparable with their white counterparts.

In the next phase of the Barbershop Study, participants’ use of various classes of antihypertensive medication will be prospectively tracked. Among other things, this will enable investigators to determine whether diuretics contribute to nocturia.

Dr. Mason reported having no conflicts of interest regarding the study.

NEW ORLEANS – Uncontrolled systolic hypertension is a strong independent determinant of nocturia in middle-aged African American men, O’Neil Mason, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from the ongoing National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Barbershop Study challenges the traditional notion of hypertension as an asymptomatic disease. It also provides a novel health promotion message aimed at improving compliance with blood pressure medication.

The Barbershop Study is a hypertension intervention trial that’s being conducted in Los Angeles barbershops frequented by black men. In the initial screening phase for study eligibility, 2,577 African American men aged 35-79 years underwent highly accurate blood pressure measurements using an average of three readings taken via an oscillometric monitor.

The mean age of the men was 53 years. It was an obese group, with a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Fifty percent of the men had hypertension, and among that cohort fully one-third weren’t on antihypertensive medication and another 28% were treated but uncontrolled, with on-treatment blood pressures of 140/90 mm Hg or more. Thus, only 39% of these middle-aged African American men with high blood pressure were treated and controlled at baseline.

Seventy-seven percent of the screened men reported awakening once or more per night to urinate. A progressive increase in nocturia severity was seen with increasing systolic blood pressure. The prevalence of nocturia ranged from 68% among normotensive men to 91% among those with treated but uncontrolled hypertension, Dr. Mason reported.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for the standard risk factors for nocturia – including advancing age, an enlarged prostate, and diabetes, which was present in 16% of the men – stage 1 systolic hypertension in the range of 140-159 mm Hg was independently associated with a 1.57-fold increased likelihood of nocturia, compared with normotensive subjects. Stage 2 hypertension, with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more, was associated with a 2.32-fold increased risk; that’s in the same ballpark as having an enlarged prostate, which carried a 2.1-fold increased risk. Prehypertension – that is, a systolic pressure of 120-139 mm Hg – was associated with a nonsignificant 1.18-fold risk.

Diastolic blood pressure wasn’t an independent determinant of nocturia.

In a similar multivariate analysis focused on severe nocturia, defined as three or more episodes per night, stage 1 systolic hypertension was independently associated with a 2.29-fold increased risk, compared with normotension, and stage 2 systolic hypertension carried a 2.77-fold increased risk.

Audience members were clearly intrigued by this novel finding. They were quick to speculate as to potential underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, including atrial stretch, increased renal blood flow, or perhaps a side effect of diuretic therapy. However, Dr. Mason and his coinvestigators favor another possibility: “African Americans have more salt-sensitive hypertension and they have less nocturnal blood pressure dipping,” he noted. “So if nighttime blood pressure is high it could lead through increased pressure natriuresis to increased urine production. More activity in getting up to go to the bathroom increases the blood pressure and creates a cycle that begets more urine.”

Asked if uncontrolled systolic hypertension is also a determinant of nocturia in African American women, Dr. Mason replied that he would assume so. But that question hasn’t ever been studied. The Barbershop Study is restricted to African American men with hypertension because studies have shown they have a particularly low rate of controlled hypertension. In contrast, the controlled hypertension rate among hypertensive African American women is comparable with their white counterparts.

In the next phase of the Barbershop Study, participants’ use of various classes of antihypertensive medication will be prospectively tracked. Among other things, this will enable investigators to determine whether diuretics contribute to nocturia.

Dr. Mason reported having no conflicts of interest regarding the study.

NEW ORLEANS – Uncontrolled systolic hypertension is a strong independent determinant of nocturia in middle-aged African American men, O’Neil Mason, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This finding from the ongoing National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Barbershop Study challenges the traditional notion of hypertension as an asymptomatic disease. It also provides a novel health promotion message aimed at improving compliance with blood pressure medication.

The Barbershop Study is a hypertension intervention trial that’s being conducted in Los Angeles barbershops frequented by black men. In the initial screening phase for study eligibility, 2,577 African American men aged 35-79 years underwent highly accurate blood pressure measurements using an average of three readings taken via an oscillometric monitor.

The mean age of the men was 53 years. It was an obese group, with a mean body mass index of 30 kg/m2. Fifty percent of the men had hypertension, and among that cohort fully one-third weren’t on antihypertensive medication and another 28% were treated but uncontrolled, with on-treatment blood pressures of 140/90 mm Hg or more. Thus, only 39% of these middle-aged African American men with high blood pressure were treated and controlled at baseline.

Seventy-seven percent of the screened men reported awakening once or more per night to urinate. A progressive increase in nocturia severity was seen with increasing systolic blood pressure. The prevalence of nocturia ranged from 68% among normotensive men to 91% among those with treated but uncontrolled hypertension, Dr. Mason reported.

In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for the standard risk factors for nocturia – including advancing age, an enlarged prostate, and diabetes, which was present in 16% of the men – stage 1 systolic hypertension in the range of 140-159 mm Hg was independently associated with a 1.57-fold increased likelihood of nocturia, compared with normotensive subjects. Stage 2 hypertension, with a systolic blood pressure of 160 mm Hg or more, was associated with a 2.32-fold increased risk; that’s in the same ballpark as having an enlarged prostate, which carried a 2.1-fold increased risk. Prehypertension – that is, a systolic pressure of 120-139 mm Hg – was associated with a nonsignificant 1.18-fold risk.

Diastolic blood pressure wasn’t an independent determinant of nocturia.

In a similar multivariate analysis focused on severe nocturia, defined as three or more episodes per night, stage 1 systolic hypertension was independently associated with a 2.29-fold increased risk, compared with normotension, and stage 2 systolic hypertension carried a 2.77-fold increased risk.

Audience members were clearly intrigued by this novel finding. They were quick to speculate as to potential underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, including atrial stretch, increased renal blood flow, or perhaps a side effect of diuretic therapy. However, Dr. Mason and his coinvestigators favor another possibility: “African Americans have more salt-sensitive hypertension and they have less nocturnal blood pressure dipping,” he noted. “So if nighttime blood pressure is high it could lead through increased pressure natriuresis to increased urine production. More activity in getting up to go to the bathroom increases the blood pressure and creates a cycle that begets more urine.”

Asked if uncontrolled systolic hypertension is also a determinant of nocturia in African American women, Dr. Mason replied that he would assume so. But that question hasn’t ever been studied. The Barbershop Study is restricted to African American men with hypertension because studies have shown they have a particularly low rate of controlled hypertension. In contrast, the controlled hypertension rate among hypertensive African American women is comparable with their white counterparts.

In the next phase of the Barbershop Study, participants’ use of various classes of antihypertensive medication will be prospectively tracked. Among other things, this will enable investigators to determine whether diuretics contribute to nocturia.

Dr. Mason reported having no conflicts of interest regarding the study.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A systolic blood pressure of 140-159 mm Hg was independently associated with a 2.29-fold increased risk of severe nocturia, compared with normotension in middle-aged African American men, while a pressure of 160 mm Hg or more conferred a 2.77-fold increased risk.

Data source: A report on the initial cross-sectional screening phase of the Barbershop Study, in which 2,577 middle-aged African American men underwent blood pressure measurements in Los Angeles barbershops.

Disclosures: The Barbershop Study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

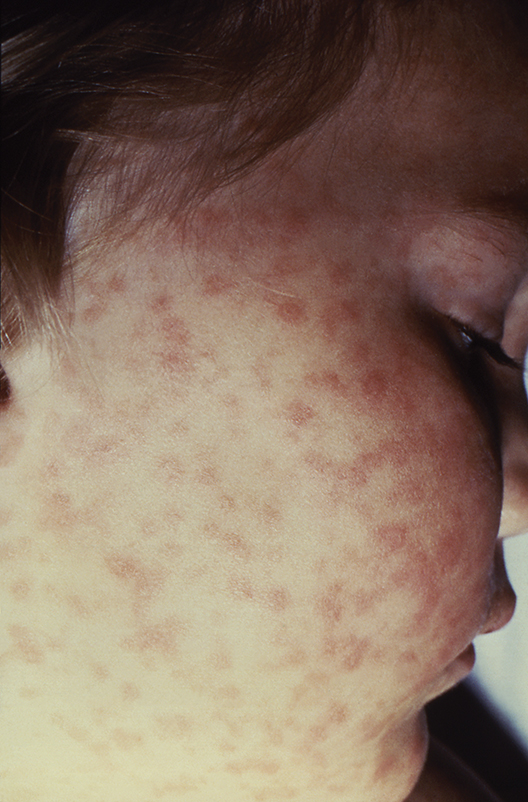

Lab values poor surrogate for detecting pediatric Rocky Mountain spotted fever in children

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

The three fatalities observed in a retrospective analysis of six cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) in children were associated with either a delayed diagnosis pending laboratory findings or delayed antirickettsia treatment.

“The fact that all fatal cases died before the convalescent period emphasizes that diagnosis should be based on clinical findings instead of RMSF serologic and histologic testing,” wrote the authors of a study published online in Pediatric Dermatology (2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1111/pde.13053).

Two of the fatal cases involved delayed antirickettsial therapy after the patients were misdiagnosed with group A streptococcus. None of the six children were initially evaluated for R. rickettsii; they averaged three encounters with their clinician before being admitted for acute inpatient care where they received intravenous doxycycline after nearly a week of symptoms.

“All fatal cases were complicated by neurologic manifestations, including seizures, obtundation, and uncal herniation,” a finding that is consistent with the literature, the authors said.

Although the high fatality rate might be the result of the small study size, Ms. Tull and her coinvestigators concluded that the disease should be considered in all differential diagnoses for children who present with a fever and rash during the summer months in endemic areas, particularly since pediatric cases of the disease are associated with poorer outcomes than in adult cases.

Given that RMSF often remains subclinical in its early stages, and typically presents with nonspecific symptoms of fever, rash, headache, and abdominal pain when it does emerge, physicians might be tempted to defer treatment until after serologic and histologic results are in, as is the standard method. Concerns over doxycycline’s tendency to stain teeth and cause enamel hypoplasia are also common. However, empirical administration could mean the difference between life and death, since treatment within the first 5 days following infection is associated with better outcomes – an algorithm complicated by the fact that symptoms caused by R. rickettsii have been known to take as long as 21 days to appear.

In the study, Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that the average time between exposure to the tick and the onset of symptoms was 6.6 days (range, 1-21 days).

Currently, there are no diagnostic tests “that reliably diagnose RMSF during the first 7 days of illness,” and most patients “do not develop detectable antibodies until the second week of illness,” the investigators reported. Even then, sensitivity of indirect fluorescent antibody serum testing after the second week of illness is only between 86% and 94%, they noted. Further, the sensitivity of immunohistochemical (IHC) tissue staining has been reported at 70%, and false-negative IHC results are common in acute disease when antibody response is harder to detect.

Ms. Tull and her colleagues found that five of the six patients in their study had negative IHC testing; two of the six had positive serum antibody titers. For this reason, they concluded that Rocky Mountain spotted fever diagnosis should be based on “clinical history, examination, and laboratory abnormalities” rather than laboratory testing, and urged that “prompt treatment should be instituted empirically.”

The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Half of pediatric patients diagnosed with Rocky Mountain spotted fever died after treatment was delayed.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of 6 pediatric RMSF cases among 3,912 inpatient dermatology consultations over a period of 10 years at a tertiary care center.

Disclosures: The authors did not have any relevant financial disclosures. .

Medicare payments set for infliximab biosimilar Inflectra

Payment for the infliximab biosimilar drug Inflectra will now be covered by Medicare, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, said in an announcement.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb) in its January 2017 Average Sales Price pricing file, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2017. Pfizer said that Inflectra is priced at a 15% discount to the current wholesale acquisition cost for the infliximab originator Remicade, but this price does not include discounts to payers, providers, distributors, and other purchasing organizations.

For the first quarter of 2017, the payment limit set by the CMS for Inflectra is $100.306 per 10-mg unit and $82.218 for Remicade.

Various national and regional wholesalers across the country began receiving shipments of Inflectra in November 2016, according to Pfizer.

In conjunction with the availability of Inflectra, Pfizer announced its enCompass program, “a comprehensive reimbursement service and patient support program offering coding and reimbursement support for providers, copay assistance to eligible patients who have commercial insurance that covers Inflectra, and financial assistance for eligible uninsured and underinsured patients.”

The FDA approved Inflectra in April 2016 for all of the same indications as Remicade: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, plaque psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis.

Payment for the infliximab biosimilar drug Inflectra will now be covered by Medicare, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, said in an announcement.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb) in its January 2017 Average Sales Price pricing file, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2017. Pfizer said that Inflectra is priced at a 15% discount to the current wholesale acquisition cost for the infliximab originator Remicade, but this price does not include discounts to payers, providers, distributors, and other purchasing organizations.

For the first quarter of 2017, the payment limit set by the CMS for Inflectra is $100.306 per 10-mg unit and $82.218 for Remicade.

Various national and regional wholesalers across the country began receiving shipments of Inflectra in November 2016, according to Pfizer.

In conjunction with the availability of Inflectra, Pfizer announced its enCompass program, “a comprehensive reimbursement service and patient support program offering coding and reimbursement support for providers, copay assistance to eligible patients who have commercial insurance that covers Inflectra, and financial assistance for eligible uninsured and underinsured patients.”

The FDA approved Inflectra in April 2016 for all of the same indications as Remicade: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, plaque psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis.

Payment for the infliximab biosimilar drug Inflectra will now be covered by Medicare, the drug’s manufacturer, Pfizer, said in an announcement.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) included Inflectra (infliximab-dyyb) in its January 2017 Average Sales Price pricing file, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2017. Pfizer said that Inflectra is priced at a 15% discount to the current wholesale acquisition cost for the infliximab originator Remicade, but this price does not include discounts to payers, providers, distributors, and other purchasing organizations.

For the first quarter of 2017, the payment limit set by the CMS for Inflectra is $100.306 per 10-mg unit and $82.218 for Remicade.

Various national and regional wholesalers across the country began receiving shipments of Inflectra in November 2016, according to Pfizer.

In conjunction with the availability of Inflectra, Pfizer announced its enCompass program, “a comprehensive reimbursement service and patient support program offering coding and reimbursement support for providers, copay assistance to eligible patients who have commercial insurance that covers Inflectra, and financial assistance for eligible uninsured and underinsured patients.”

The FDA approved Inflectra in April 2016 for all of the same indications as Remicade: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, plaque psoriasis, and ulcerative colitis.

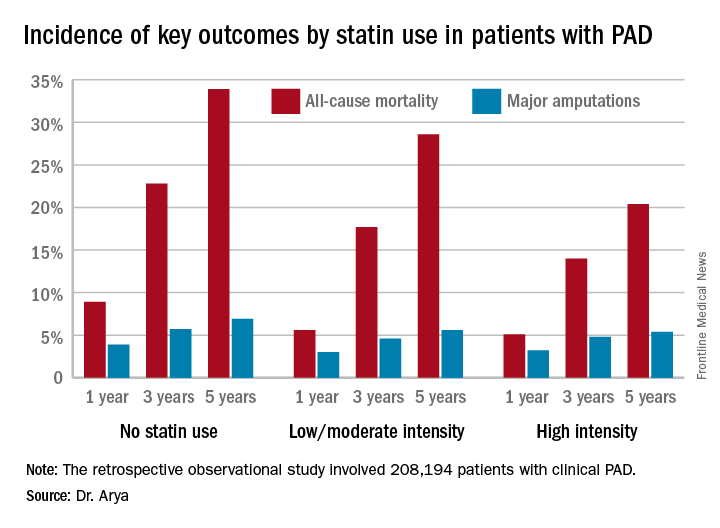

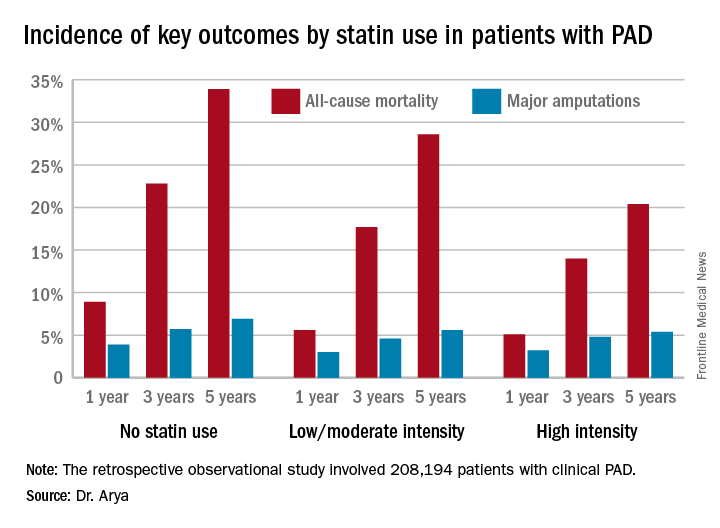

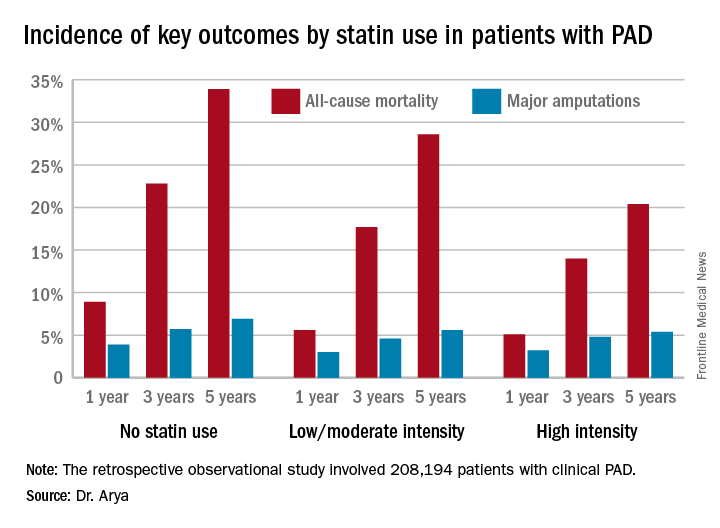

High-intensity statins cut amputations and mortality in PAD

NEW ORLEANS – High-intensity statin therapy in patients with peripheral artery disease was associated with significant reductions in amputations as well as mortality during up to 5 years of follow-up in the first large study to examine the relationship, Shipra Arya, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy also improved survival compared to no statin, albeit to a significantly lesser magnitude than high-intensity therapy. But high- and low/intermediate-intensity statins were similarly effective in reducing amputation risk, according to Dr. Arya, a vascular surgeon at Emory University in Atlanta.

The 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology treatment guidelines recommend high-intensity statins for all patients with clinical atherosclerotic disease, including those with PAD (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S1-45). (Updated PAD guidelines unveiled at the AHA meeting strongly recommend statin medication for all patients with PAD [Circulation. 2016 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000470]).However, the bulk of patients in Dr. Arya’s study were captured in the database prior to release of the 2013 guidelines. That may account for the sparse use of high-intensity statin therapy in the study cohort. Indeed, only 11.3% of the PAD patients were on a high-intensity statin. Another 36.2% were on moderate-intensity statin therapy, 3.5% were on low-intensity therapy, and 27.6% weren’t on a statin at all.

The relationship between statin therapy and mortality was strongly dose-dependent.

This study was funded by the AHA and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Arya reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – High-intensity statin therapy in patients with peripheral artery disease was associated with significant reductions in amputations as well as mortality during up to 5 years of follow-up in the first large study to examine the relationship, Shipra Arya, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy also improved survival compared to no statin, albeit to a significantly lesser magnitude than high-intensity therapy. But high- and low/intermediate-intensity statins were similarly effective in reducing amputation risk, according to Dr. Arya, a vascular surgeon at Emory University in Atlanta.

The 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology treatment guidelines recommend high-intensity statins for all patients with clinical atherosclerotic disease, including those with PAD (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S1-45). (Updated PAD guidelines unveiled at the AHA meeting strongly recommend statin medication for all patients with PAD [Circulation. 2016 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000470]).However, the bulk of patients in Dr. Arya’s study were captured in the database prior to release of the 2013 guidelines. That may account for the sparse use of high-intensity statin therapy in the study cohort. Indeed, only 11.3% of the PAD patients were on a high-intensity statin. Another 36.2% were on moderate-intensity statin therapy, 3.5% were on low-intensity therapy, and 27.6% weren’t on a statin at all.

The relationship between statin therapy and mortality was strongly dose-dependent.

This study was funded by the AHA and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Arya reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

NEW ORLEANS – High-intensity statin therapy in patients with peripheral artery disease was associated with significant reductions in amputations as well as mortality during up to 5 years of follow-up in the first large study to examine the relationship, Shipra Arya, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Low- or moderate-intensity statin therapy also improved survival compared to no statin, albeit to a significantly lesser magnitude than high-intensity therapy. But high- and low/intermediate-intensity statins were similarly effective in reducing amputation risk, according to Dr. Arya, a vascular surgeon at Emory University in Atlanta.

The 2013 AHA/American College of Cardiology treatment guidelines recommend high-intensity statins for all patients with clinical atherosclerotic disease, including those with PAD (Circulation. 2014 Jun 24;129[25 Suppl 2]:S1-45). (Updated PAD guidelines unveiled at the AHA meeting strongly recommend statin medication for all patients with PAD [Circulation. 2016 Nov 13. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000470]).However, the bulk of patients in Dr. Arya’s study were captured in the database prior to release of the 2013 guidelines. That may account for the sparse use of high-intensity statin therapy in the study cohort. Indeed, only 11.3% of the PAD patients were on a high-intensity statin. Another 36.2% were on moderate-intensity statin therapy, 3.5% were on low-intensity therapy, and 27.6% weren’t on a statin at all.

The relationship between statin therapy and mortality was strongly dose-dependent.

This study was funded by the AHA and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Dr. Arya reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The 5-year all-cause mortality rate after diagnosis of peripheral artery disease was 20.4% in patients on high-intensity statin therapy, 28.6% in those on a low- or moderate-intensity statin, and 33.9% in patients not on a statin.

Data source: A retrospective observational study of 208,194 patients with clinical peripheral artery disease in the national Veterans Affairs database for 2003-2014.

Disclosures: The AHA and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center funded the study. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

USPSTF reaffirms need for folic acid supplements in pregnancy

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The USPSTF recommendation that all women of childbearing age take folic acid supplements is a prudent one. Ideally, it will educate all women who are planning or capable of pregnancy to follow this recommendation and thereby reduce the risk of these severe birth defects in their infants.

Should the USPSTF recommendation be rejected because fortified food is already providing sufficient folic acid to prevent neural tube defects? No. Too little is known about how folic acid prevents neural tube defects. For example, it is not known whether the tissue stores of folate in the developing embryo or the availability of folate in the serum during the all-important few days of neural tube closure is most important. Habitual use of folic acid supplements is a more reliable method of ensuring adequate levels than is diet. In theory, a woman might not consume sufficient enriched cereal grains during the critical period of approximately 1 week when the neural tube is closing. Exactly when folate must be available also is not known. In addition, some popular diets, such as low carbohydrate or gluten free, may reduce exposure to grains, limiting folic acid intake.

James L. Mills, MD, is in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development in Bethesda, Md. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF report (JAMA. 2017;317 [2]:144-5).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force continues to recommend that all women planning or capable of pregnancy should take a daily supplement of 0.4-0.8 mg of folic acid to prevent neural tube defects in their offspring.

The task force “concludes with high certainty” that the benefits of such supplementation are substantial and the harms are minimal, according to the recommendation statement published online Jan. 10 in JAMA (2017;317[2]:183-9). The group based its updated recommendation on a systematic review of 24 studies performed since 2009 and involving 58,860 women. Although some newer studies have suggested that supplementation is no longer needed in this era of folic acid fortification of foods, “the USPSTF found no new substantial evidence ... that would lead to a change in its recommendation from 2009,” the researchers wrote.

The most recent data estimate that folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in approximately 1,300 births each year.

This updated USPSTF recommendation is in accord with recommendations from the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies (formerly the Institute of Medicine), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Folic acid supplementation prevents neural tube defects in an estimated 1,300 births each year in the United States.

Data source: A systematic review of 24 studies (involving 58,860 women) that were performed since 2009 regarding the benefits and harms of folic acid supplementation.

Disclosures: This work was supported solely by the USPSTF, an independent voluntary group mandated by Congress to assess preventive care services and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

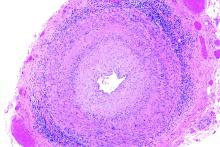

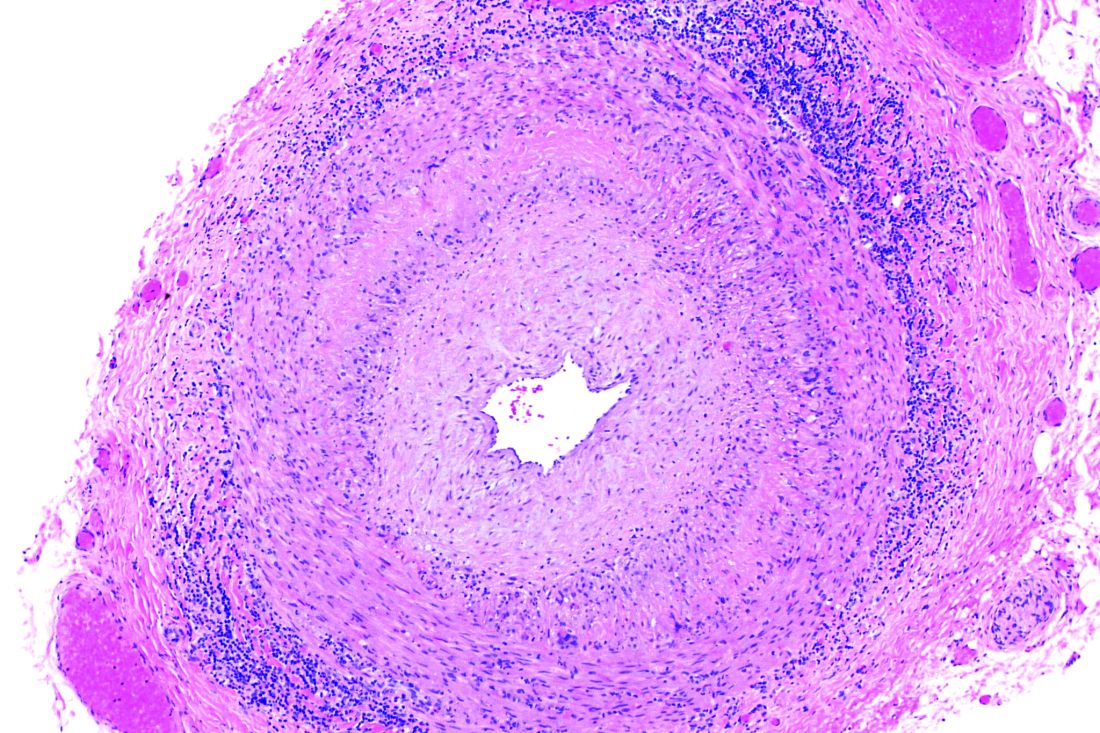

Giant cell arteritis independently raises risk for venous thromboembolism

The risk of venous thromboembolism increases markedly shortly before the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis regardless of glucocorticoid exposure, peaks at the time of diagnosis, and then progressively declines, according to a matched cohort review involving more than 6,000 arteritis patients.

It’s not been clear until now if the recently recognized risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in giant cell arteritis (GCA) was due to the disease itself, or the glucocorticoids used to treat it. “Because inflammation in GCA spares the venous circulation, our finding that patients are at greatest risk of VTE in the period surrounding GCA diagnosis (when inflammation is at its highest level), and the demonstration that this risk is not associated with the use of glucocorticoids, suggest that immunothrombosis could play a pathogenic role,” said investigators led by Sebastian Unizony, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:176-84).

The report was short on advice about what to do to prevent VTE in GCA, but the investigators did recommend “adequate monitoring ... for early recognition of this potentially serious complication.”

The team used a British medical record database covering 1990-2013 to compare 6,441 patients with new-onset GCA to 63,985 controls without GCA matched for age, sex, and date of study entry. VTE was defined as pulmonary embolism and/or deep vein thrombosis.

The incidence of VTE shortly before diagnosis was 4.2 cases per 1,000 person-years in the GCA group, but 2.3 cases per 1,000 person-years among controls. It was about the same when the analysis was limited to GCA patients not exposed to oral glucocorticoids before diagnosis: 4.0 cases versus 2.2 cases in the control group per 1,000 person-years. The finding was key to the conclusion that GCA is an independent VTE risk factor.

During the 12, 9, 6, and 3 months leading up to GCA diagnosis, the relative risks for VTE among patients not treated with glucocorticoids – versus controls – were 1.8, 2.2, 2.4, and 3.6. In the first 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 months after GCA diagnosis, when virtually all patients were on glucocorticoids at least for the first 6 months, the relative risks for VTE were 9.9, 7.7, 5.9, 4.4, 3.3, 2.4; the last risk score of 2.4 indicated that GCA patients were still slightly more likely than controls to have a VTE even 8 years after diagnosis.

The mean age of patients in the study was 73 years, and 70% of the subjects were women. GCA patients were more likely than were controls to be smokers and to have cardiovascular disease. Also, a greater proportion of GCA patients used aspirin and had recent surgery and hospitalizations. There was no difference in body mass index (mean in both groups 27 kg/m2) or the prevalence of fracture, trauma, or cancer between the groups.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. There was no disclosure information in the report.

Whether these findings have implications for treatment is unclear. Should a patient with GCA who sustains a VTE early in the course of disease receive anticoagulation short term, with the thought that the VTE was provoked by a risk factor that has been neutralized? Or should treatment be long term, out of concern that the risk factor is still present? Does this finding bear on the controversial question of whether a patient with GCA should receive aspirin?

[A] robust finding of the analysis is that the risk of a first VTE declines steadily over at least the first 2 years after diagnosis of GCA. However, the problem of distinguishing the effects of disease from the effects of treatment has returned. All patients with GCA are now receiving corticosteroids, at least during the period of very high risk in the first 6 months after diagnosis, and one can expect that the average severity of inflammation and average dose of prednisone/prednisolone will decline in parallel. The steadily declining risk of VTE for at least 1 year after diagnosis suggests that both GCA and corticosteroids increase the risk of VTE. It remains impossible to prove or disprove that hypothesis or to estimate the independent risks conferred by the disease and its treatment.

Having GCA probably increases the risk of VTE at least for the first 24 months after diagnosis and the beginning of treatment, but after 24 months, it is unclear. The clinician will still need to make a guess regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Paul Monach, MD, PhD, is a vasculitis specialist at Boston University. He made his comments in an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:3-5).

Whether these findings have implications for treatment is unclear. Should a patient with GCA who sustains a VTE early in the course of disease receive anticoagulation short term, with the thought that the VTE was provoked by a risk factor that has been neutralized? Or should treatment be long term, out of concern that the risk factor is still present? Does this finding bear on the controversial question of whether a patient with GCA should receive aspirin?

[A] robust finding of the analysis is that the risk of a first VTE declines steadily over at least the first 2 years after diagnosis of GCA. However, the problem of distinguishing the effects of disease from the effects of treatment has returned. All patients with GCA are now receiving corticosteroids, at least during the period of very high risk in the first 6 months after diagnosis, and one can expect that the average severity of inflammation and average dose of prednisone/prednisolone will decline in parallel. The steadily declining risk of VTE for at least 1 year after diagnosis suggests that both GCA and corticosteroids increase the risk of VTE. It remains impossible to prove or disprove that hypothesis or to estimate the independent risks conferred by the disease and its treatment.

Having GCA probably increases the risk of VTE at least for the first 24 months after diagnosis and the beginning of treatment, but after 24 months, it is unclear. The clinician will still need to make a guess regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Paul Monach, MD, PhD, is a vasculitis specialist at Boston University. He made his comments in an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:3-5).

Whether these findings have implications for treatment is unclear. Should a patient with GCA who sustains a VTE early in the course of disease receive anticoagulation short term, with the thought that the VTE was provoked by a risk factor that has been neutralized? Or should treatment be long term, out of concern that the risk factor is still present? Does this finding bear on the controversial question of whether a patient with GCA should receive aspirin?

[A] robust finding of the analysis is that the risk of a first VTE declines steadily over at least the first 2 years after diagnosis of GCA. However, the problem of distinguishing the effects of disease from the effects of treatment has returned. All patients with GCA are now receiving corticosteroids, at least during the period of very high risk in the first 6 months after diagnosis, and one can expect that the average severity of inflammation and average dose of prednisone/prednisolone will decline in parallel. The steadily declining risk of VTE for at least 1 year after diagnosis suggests that both GCA and corticosteroids increase the risk of VTE. It remains impossible to prove or disprove that hypothesis or to estimate the independent risks conferred by the disease and its treatment.

Having GCA probably increases the risk of VTE at least for the first 24 months after diagnosis and the beginning of treatment, but after 24 months, it is unclear. The clinician will still need to make a guess regarding duration of anticoagulation.

Paul Monach, MD, PhD, is a vasculitis specialist at Boston University. He made his comments in an accompanying editorial (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:3-5).

The risk of venous thromboembolism increases markedly shortly before the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis regardless of glucocorticoid exposure, peaks at the time of diagnosis, and then progressively declines, according to a matched cohort review involving more than 6,000 arteritis patients.

It’s not been clear until now if the recently recognized risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in giant cell arteritis (GCA) was due to the disease itself, or the glucocorticoids used to treat it. “Because inflammation in GCA spares the venous circulation, our finding that patients are at greatest risk of VTE in the period surrounding GCA diagnosis (when inflammation is at its highest level), and the demonstration that this risk is not associated with the use of glucocorticoids, suggest that immunothrombosis could play a pathogenic role,” said investigators led by Sebastian Unizony, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:176-84).

The report was short on advice about what to do to prevent VTE in GCA, but the investigators did recommend “adequate monitoring ... for early recognition of this potentially serious complication.”

The team used a British medical record database covering 1990-2013 to compare 6,441 patients with new-onset GCA to 63,985 controls without GCA matched for age, sex, and date of study entry. VTE was defined as pulmonary embolism and/or deep vein thrombosis.

The incidence of VTE shortly before diagnosis was 4.2 cases per 1,000 person-years in the GCA group, but 2.3 cases per 1,000 person-years among controls. It was about the same when the analysis was limited to GCA patients not exposed to oral glucocorticoids before diagnosis: 4.0 cases versus 2.2 cases in the control group per 1,000 person-years. The finding was key to the conclusion that GCA is an independent VTE risk factor.

During the 12, 9, 6, and 3 months leading up to GCA diagnosis, the relative risks for VTE among patients not treated with glucocorticoids – versus controls – were 1.8, 2.2, 2.4, and 3.6. In the first 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 months after GCA diagnosis, when virtually all patients were on glucocorticoids at least for the first 6 months, the relative risks for VTE were 9.9, 7.7, 5.9, 4.4, 3.3, 2.4; the last risk score of 2.4 indicated that GCA patients were still slightly more likely than controls to have a VTE even 8 years after diagnosis.

The mean age of patients in the study was 73 years, and 70% of the subjects were women. GCA patients were more likely than were controls to be smokers and to have cardiovascular disease. Also, a greater proportion of GCA patients used aspirin and had recent surgery and hospitalizations. There was no difference in body mass index (mean in both groups 27 kg/m2) or the prevalence of fracture, trauma, or cancer between the groups.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. There was no disclosure information in the report.

The risk of venous thromboembolism increases markedly shortly before the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis regardless of glucocorticoid exposure, peaks at the time of diagnosis, and then progressively declines, according to a matched cohort review involving more than 6,000 arteritis patients.

It’s not been clear until now if the recently recognized risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in giant cell arteritis (GCA) was due to the disease itself, or the glucocorticoids used to treat it. “Because inflammation in GCA spares the venous circulation, our finding that patients are at greatest risk of VTE in the period surrounding GCA diagnosis (when inflammation is at its highest level), and the demonstration that this risk is not associated with the use of glucocorticoids, suggest that immunothrombosis could play a pathogenic role,” said investigators led by Sebastian Unizony, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 Jan;69[1]:176-84).

The report was short on advice about what to do to prevent VTE in GCA, but the investigators did recommend “adequate monitoring ... for early recognition of this potentially serious complication.”

The team used a British medical record database covering 1990-2013 to compare 6,441 patients with new-onset GCA to 63,985 controls without GCA matched for age, sex, and date of study entry. VTE was defined as pulmonary embolism and/or deep vein thrombosis.

The incidence of VTE shortly before diagnosis was 4.2 cases per 1,000 person-years in the GCA group, but 2.3 cases per 1,000 person-years among controls. It was about the same when the analysis was limited to GCA patients not exposed to oral glucocorticoids before diagnosis: 4.0 cases versus 2.2 cases in the control group per 1,000 person-years. The finding was key to the conclusion that GCA is an independent VTE risk factor.

During the 12, 9, 6, and 3 months leading up to GCA diagnosis, the relative risks for VTE among patients not treated with glucocorticoids – versus controls – were 1.8, 2.2, 2.4, and 3.6. In the first 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 96 months after GCA diagnosis, when virtually all patients were on glucocorticoids at least for the first 6 months, the relative risks for VTE were 9.9, 7.7, 5.9, 4.4, 3.3, 2.4; the last risk score of 2.4 indicated that GCA patients were still slightly more likely than controls to have a VTE even 8 years after diagnosis.

The mean age of patients in the study was 73 years, and 70% of the subjects were women. GCA patients were more likely than were controls to be smokers and to have cardiovascular disease. Also, a greater proportion of GCA patients used aspirin and had recent surgery and hospitalizations. There was no difference in body mass index (mean in both groups 27 kg/m2) or the prevalence of fracture, trauma, or cancer between the groups.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. There was no disclosure information in the report.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In the 12, 9, 6, and 3 months before GCA diagnosis, the relative risks for VTE among patients not treated with glucocorticoids – versus controls without GCA – were 1.8, 2.2, 2.4, and 3.6.

Data source: Matched cohort review involving more than 6,000 arteritis patients.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the work. There was no disclosure information in the report.

Medicare failed to recover up to $125 million in overpayments, records show

Six years ago, federal health officials were confident they could save taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars annually by auditing private Medicare Advantage insurance plans that allegedly overcharged the government for medical services.

An initial round of audits found that Medicare had potentially overpaid five of the health plans $128 million in 2007 alone, according to confidential government documents released recently in response to a public records request and lawsuit.

But officials never recovered most of that money. Under intense pressure from the health insurance industry, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services quietly backed off their repayment demands and settled the audits in 2012 for just under $3.4 million – shortchanging taxpayers by up to $125 million in possible overcharges just for 2007.

Medicare Advantage is a popular alternative to traditional Medicare. The privately run health plans have enrolled more than 17 million elderly and disabled people – about a third of those eligible for Medicare – at a cost to taxpayers of more than $150 billion a year. And while the plans generally enjoy strong support in Congress, there are critics.

“It’s unclear why the Obama Administration allowed CMS to overpromise and under-deliver so badly on collecting these overpayments,” Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, told Kaiser Health News in an email response to the findings.

He said CMS “should account for why this process seems to be so broken and why it can’t seem to fix it, despite recommendations to do so. The taxpayers depend on getting this process right.”

The failure to collect also alarmed Steve Ellis, vice president of the budget watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense in Washington.

“They need to put up a bigger and stronger fight to make sure these programs are operated on the straight and narrow,” Mr. Ellis said.

Yet outside of public view, federal officials have been losing a high-stakes battle to curb widespread billing errors by Medicare Advantage plans, according to the records obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit filed by the Center for Public Integrity.

The Center for Public Integrity first disclosed in 2014 that billions of tax dollars are wasted annually partly because some health plans appear to exaggerate how sick their patients are, a practice known in health care circles as “upcoding.”

Last August, the investigative journalism group reported that 35 of 37 health plans CMS has audited overcharged Medicare, often by overstating the severity of medical conditions such as diabetes and depression.

The newly released CMS records identify the companies chosen for the initial 2007 audits as a Florida Humana plan, a Washington state subsidiary of United Healthcare called PacifiCare, an Aetna plan in New Jersey, and an Independence Blue Cross plan in the Philadelphia area.

The fifth one focused on a Lovelace Medicare plan in New Mexico, which has since been acquired by Blue Cross.

Each of the five audits, which took more than 2 years to complete, unearthed significant – and costly – billing mistakes, though the plans disputed them.

For example, auditors couldn’t confirm that one-third of the diseases the health plans had been paid to treat actually existed, mostly because patient records lacked “sufficient documentation of a diagnosis.”

Overall, Medicare paid the wrong amount for nearly two-thirds of patients whose records were examined; all five plans were far more likely to charge too much than too little. For one in five patients, the overcharges were $5,000 or more for the year, according to the audits. None of the plans would discuss the findings.

As preliminary results of the audits started to roll in, CMS officials outlined steps to recover more than $128 million from the five plans at a confidential agency briefing in August 2010, according to a policy memo prepared for the meeting. The records don’t indicate who attended.

That day, CMS set Humana’s payment error at $33.5 million, PacifiCare at $20.2 million, Aetna at $27.6 million, Independence Blue Cross at nearly $34 million and Lovelace at just under $13 million. Those estimates were based on extrapolation of a sample of cases examined at each plan.

CMS “has developed a process for moving forward with payment recovery,” according to a briefing paper from the 2010 meeting.

But that process fizzled after 2 years of haggling with the plans and insurance industry representatives, who argued the audits were flawed and the results unreliable. In August 2012, CMS gave in and notified the plans it would settle for a few cents on the dollar.

“Given this was a new process, the decision was made at the time to tie repayments to the actual claims reviewed as part of the 2007 pilot audit,” said CMS spokesman Aaron Albright. “For subsequent audits, we said we intended to determine repayments by extrapolating the error rate of the sample of claims reviewed to all claims under the contract.” Mr. Albright said more of the audits are underway. Allowing the insurers to dodge liability dealt a serious blow to the government’s efforts to crack down on billing abuses – a setback one taxpayer advocate called alarming.

“That’s a very bad way to operate the system.” said Patrick Burns, acting executive director and president of Taxpayers Against Fraud in Washington, on hearing of the outcome. “Nobody is held accountable.”

Indeed, CMS kept the settlement terms under wraps until 2015, after an inquiry by Sen. Grassley. The senator had requested details about Medicare Advantage fraud controls in response to articles published by the Center for Public Integrity.

In a July 31, 2015 letter to Sen. Grassley, CMS Acting Administrator Andy Slavitt attached a table that showed the five plans repaid just under $3.4 million. The letter didn’t mention the earlier estimate that the government was due $128 million. Sen. Grassley said it should not have taken the FOIA lawsuit to make that information available to the public.

“Perhaps adding insult to injury, these numbers might never have seen the light of day without a lengthy lawsuit,” Sen. Grassley said this week.

Paying based on risk scores

When Congress created the current Medicare Advantage program in 2003, it devised a new way to pay the health plans.

The method, phased in starting in 2004, seemed simple enough: Pay higher rates for sicker patients and less for people in good health using a formula called a risk score.

But CMS officials soon realized that risk scores rose much faster at some plans than others, a possible sign of upcoding, or other billing irregularities, records show. These overcharges topped $4 billion in 2005, one CMS study found.

The special audits, called Risk Adjustment Data Validation, or RADV, were designed to identify, and hold accountable, health plans that couldn’t justify their fees with supporting medical evidence.

Until these audits, CMS “pretty much went on the honor system with the plans,” an unnamed agency official wrote in an undated presentation.

In the five 2007 pilot audits, two sets of auditors inspected medical records for a random sample of 201 patients at each plan. If the medical chart didn’t properly document that a patient had the illnesses the plan had reported, Medicare wanted a refund. Auditors gave the plans the benefit of the doubt when auditors couldn’t agree, according to the CMS briefing paper.

Finally, CMS applied a standard technique used in fraud investigations in which the payment error rate is extrapolated across the entire health plan, which greatly multiplies the amount due. CMS said it was conservative in assessing the penalties and allowed the plans to appeal.

Appeals or no, the health plans recoiled at the prospect they could be on the hook for millions of dollars they hadn’t budgeted for and didn’t believe they owed. The actual 2007 overage for the 201 Humana patients, for example, was $477,235. Once extrapolated, it soared to $33.5 million.

Michael S. Adelberg, a former CMS official who is now an industry consultant in Washington, said that in retrospect the audit process was “probably rushed.”

Mr. Adelberg said the audits “raised strong industry concerns” on a variety of fronts, from whether CMS had the legal authority to conduct them to the soundness of their methods. CMS stands by its audit techniques and has defended RADV as the only way it can assure plans bill honestly.

Yet agency records released through the FOIA case suggest CMS lacked the will to press ahead with extrapolated audits for Medicare Advantage plans given the fierce industry backlash – even though they do so in overpayment cases targeting other types of medical providers.

One confidential CMS presentation dated March 30, 2011, notes that officials had received more than 500 comments expressing “significant resistance” to the RADV audits.

The presentation goes on to say the audit program’s success depended on its “ability to address the challenges raised.”

CMS didn’t overcome those challenges. Instead, it agreed to settle the five initial audits for $3.4 million, just what it found in the patient files it reviewed – without the extrapolations. And the center did the same for 32 additional 2007 audits, which officials had predicted would refund up to $800 million to the federal treasury. In the end, CMS wound up with $10.3 million from the 32 plans.