User login

Promising pipeline for chronic pruritus

VIENNA – Help is on the way for physicians stymied in their efforts to treat patients with severe chronic itch, Sonja Ständer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Now working their way through the developmental pipeline are two promising novel classes of drugs designed to target the physiologic mechanisms underlying this common and challenging problem: neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonists and selective opioid receptor agonists, explained Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

She led a landmark study that outlined the previously unappreciated dimensions of chronic pruritus as a clinical issue. This was a cross-sectional study of nearly 12,000 German employees in various industries that demonstrated the prevalence of chronic pruritus was 16.8%. One-quarter of affected individuals had chronic pruritus for longer than 5 years. The prevalence climbed with age, from 12% in workers up to age 30 years to 20% in 61- to 70-year-olds (Dermatology. 2010;221[3]:229-35).

One in three patients who present to dermatologists’ offices have chronic pruritus, she added.

Chronic pruritus can have a multitude of different causes: not only chronic skin diseases, but incurable renal and liver diseases, psychiatric conditions, neurologic disorders, drug side effects, and various forms of cancer, with hematologic malignancies figuring prominently. The quality of life impact is huge. And even though a plethora of topical and systemic therapies are available for itchy skin, they often are ineffective in patients with severe chronic pruritus. Thus, there is a significant unmet need for new and effective therapies, Dr. Ständer continued.

NK1 receptor antagonists: Substance P is a neuropeptide which plays a major role in the induction and maintenance of pruritus. The NK1 receptor, which is abundantly expressed in the skin and CNS, is substance P’s receptor – and therefore a logical target for novel anti-itch therapy. Bind that receptor and a key signaling pathway in pruritus is disrupted.

Aprepitant is an oral NK1 receptor antagonist approved as Emend more than a decade ago for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ständer was lead author of an early single-arm pilot study showing aprepitant is also dramatically effective for severe refractory chronic pruritus (PLoS One. 2010 Jun 4;5[6]:e10968).

Aprepitant is approved only for 3 days of use for its licensed indication. However, Dr. Ständer said she and other dermatologists have used it off-label for as long as 4 weeks in patients with chronic pruritus and found it to be safe, with mild nonlimiting side effects and relief that is often long lasting after treatment discontinuation.

Oral aprepitant is under study in several ongoing phase II clinical trials for treatment of severe pruritus resulting from targeted biologic therapies for various cancers. In addition, Leo Pharma is developing a topical gel formulation of aprepitant for chronic pruritus which is now in phase II studies.

Serlopitant is a once-daily oral NK1 receptor antagonist under development specifically for treatment of severe chronic pruritus. In a recent as-yet unpublished multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial involving 257 patients with severe refractory chronic pruritus of various etiologies, 6 weeks of serlopitant at 1 or 5 mg/day was markedly more effective than placebo in reducing itch intensity. Based upon these favorable results, Menlo Therapeutics has begun two new phase II randomized, placebo-controlled studies of the drug: ATOMIK, a roughly 450-patient, 40 U.S.-site study in patients with atopic dermatitis; and AUBURN, involving roughly 150 burn patients with chronic pruritus at 20 centers.

Selective opioid receptor agonists: These agents target kappa- and/or mu-opioid receptors on peripheral pain-sensing neurons in order to inhibit itch without activating other opioid receptors linked to classic opioid side effects such as respiratory depression, constipation, and addiction. These selective agents are essentially designed to be nonnarcotic opioids.

One such agent is nalfurafine, an oral kappa-opioid receptor agonist marketed in Japan for treatment of uremic pruritus in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis and for refractory pruritus in chronic liver disease. The drug is in phase II studies in the United States.

Nalbuphine, a dual kappa-opiod agonist and partial mu-opioid antagonist, is Food and Drug Administration–approved as an injectable agent, known as Nubain, for moderate to severe pain. An investigational extended-release tablet formulation has successfully completed a U.S. multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II/III clinical trial in hemodialysis patients with severe chronic uremic pruritus and a phase II study in patients with prurigo nodularis. Because the drug was effective in two conditions having very different sources of itch, it is likely to be of benefit in many forms of severe chronic pruritus, Dr. Ständer said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Help is on the way for physicians stymied in their efforts to treat patients with severe chronic itch, Sonja Ständer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Now working their way through the developmental pipeline are two promising novel classes of drugs designed to target the physiologic mechanisms underlying this common and challenging problem: neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonists and selective opioid receptor agonists, explained Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

She led a landmark study that outlined the previously unappreciated dimensions of chronic pruritus as a clinical issue. This was a cross-sectional study of nearly 12,000 German employees in various industries that demonstrated the prevalence of chronic pruritus was 16.8%. One-quarter of affected individuals had chronic pruritus for longer than 5 years. The prevalence climbed with age, from 12% in workers up to age 30 years to 20% in 61- to 70-year-olds (Dermatology. 2010;221[3]:229-35).

One in three patients who present to dermatologists’ offices have chronic pruritus, she added.

Chronic pruritus can have a multitude of different causes: not only chronic skin diseases, but incurable renal and liver diseases, psychiatric conditions, neurologic disorders, drug side effects, and various forms of cancer, with hematologic malignancies figuring prominently. The quality of life impact is huge. And even though a plethora of topical and systemic therapies are available for itchy skin, they often are ineffective in patients with severe chronic pruritus. Thus, there is a significant unmet need for new and effective therapies, Dr. Ständer continued.

NK1 receptor antagonists: Substance P is a neuropeptide which plays a major role in the induction and maintenance of pruritus. The NK1 receptor, which is abundantly expressed in the skin and CNS, is substance P’s receptor – and therefore a logical target for novel anti-itch therapy. Bind that receptor and a key signaling pathway in pruritus is disrupted.

Aprepitant is an oral NK1 receptor antagonist approved as Emend more than a decade ago for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ständer was lead author of an early single-arm pilot study showing aprepitant is also dramatically effective for severe refractory chronic pruritus (PLoS One. 2010 Jun 4;5[6]:e10968).

Aprepitant is approved only for 3 days of use for its licensed indication. However, Dr. Ständer said she and other dermatologists have used it off-label for as long as 4 weeks in patients with chronic pruritus and found it to be safe, with mild nonlimiting side effects and relief that is often long lasting after treatment discontinuation.

Oral aprepitant is under study in several ongoing phase II clinical trials for treatment of severe pruritus resulting from targeted biologic therapies for various cancers. In addition, Leo Pharma is developing a topical gel formulation of aprepitant for chronic pruritus which is now in phase II studies.

Serlopitant is a once-daily oral NK1 receptor antagonist under development specifically for treatment of severe chronic pruritus. In a recent as-yet unpublished multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial involving 257 patients with severe refractory chronic pruritus of various etiologies, 6 weeks of serlopitant at 1 or 5 mg/day was markedly more effective than placebo in reducing itch intensity. Based upon these favorable results, Menlo Therapeutics has begun two new phase II randomized, placebo-controlled studies of the drug: ATOMIK, a roughly 450-patient, 40 U.S.-site study in patients with atopic dermatitis; and AUBURN, involving roughly 150 burn patients with chronic pruritus at 20 centers.

Selective opioid receptor agonists: These agents target kappa- and/or mu-opioid receptors on peripheral pain-sensing neurons in order to inhibit itch without activating other opioid receptors linked to classic opioid side effects such as respiratory depression, constipation, and addiction. These selective agents are essentially designed to be nonnarcotic opioids.

One such agent is nalfurafine, an oral kappa-opioid receptor agonist marketed in Japan for treatment of uremic pruritus in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis and for refractory pruritus in chronic liver disease. The drug is in phase II studies in the United States.

Nalbuphine, a dual kappa-opiod agonist and partial mu-opioid antagonist, is Food and Drug Administration–approved as an injectable agent, known as Nubain, for moderate to severe pain. An investigational extended-release tablet formulation has successfully completed a U.S. multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II/III clinical trial in hemodialysis patients with severe chronic uremic pruritus and a phase II study in patients with prurigo nodularis. Because the drug was effective in two conditions having very different sources of itch, it is likely to be of benefit in many forms of severe chronic pruritus, Dr. Ständer said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

VIENNA – Help is on the way for physicians stymied in their efforts to treat patients with severe chronic itch, Sonja Ständer, MD, declared at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

Now working their way through the developmental pipeline are two promising novel classes of drugs designed to target the physiologic mechanisms underlying this common and challenging problem: neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonists and selective opioid receptor agonists, explained Dr. Ständer, professor of dermatology and head of the Center for Chronic Pruritus at the University of Münster (Germany).

She led a landmark study that outlined the previously unappreciated dimensions of chronic pruritus as a clinical issue. This was a cross-sectional study of nearly 12,000 German employees in various industries that demonstrated the prevalence of chronic pruritus was 16.8%. One-quarter of affected individuals had chronic pruritus for longer than 5 years. The prevalence climbed with age, from 12% in workers up to age 30 years to 20% in 61- to 70-year-olds (Dermatology. 2010;221[3]:229-35).

One in three patients who present to dermatologists’ offices have chronic pruritus, she added.

Chronic pruritus can have a multitude of different causes: not only chronic skin diseases, but incurable renal and liver diseases, psychiatric conditions, neurologic disorders, drug side effects, and various forms of cancer, with hematologic malignancies figuring prominently. The quality of life impact is huge. And even though a plethora of topical and systemic therapies are available for itchy skin, they often are ineffective in patients with severe chronic pruritus. Thus, there is a significant unmet need for new and effective therapies, Dr. Ständer continued.

NK1 receptor antagonists: Substance P is a neuropeptide which plays a major role in the induction and maintenance of pruritus. The NK1 receptor, which is abundantly expressed in the skin and CNS, is substance P’s receptor – and therefore a logical target for novel anti-itch therapy. Bind that receptor and a key signaling pathway in pruritus is disrupted.

Aprepitant is an oral NK1 receptor antagonist approved as Emend more than a decade ago for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Dr. Ständer was lead author of an early single-arm pilot study showing aprepitant is also dramatically effective for severe refractory chronic pruritus (PLoS One. 2010 Jun 4;5[6]:e10968).

Aprepitant is approved only for 3 days of use for its licensed indication. However, Dr. Ständer said she and other dermatologists have used it off-label for as long as 4 weeks in patients with chronic pruritus and found it to be safe, with mild nonlimiting side effects and relief that is often long lasting after treatment discontinuation.

Oral aprepitant is under study in several ongoing phase II clinical trials for treatment of severe pruritus resulting from targeted biologic therapies for various cancers. In addition, Leo Pharma is developing a topical gel formulation of aprepitant for chronic pruritus which is now in phase II studies.

Serlopitant is a once-daily oral NK1 receptor antagonist under development specifically for treatment of severe chronic pruritus. In a recent as-yet unpublished multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial involving 257 patients with severe refractory chronic pruritus of various etiologies, 6 weeks of serlopitant at 1 or 5 mg/day was markedly more effective than placebo in reducing itch intensity. Based upon these favorable results, Menlo Therapeutics has begun two new phase II randomized, placebo-controlled studies of the drug: ATOMIK, a roughly 450-patient, 40 U.S.-site study in patients with atopic dermatitis; and AUBURN, involving roughly 150 burn patients with chronic pruritus at 20 centers.

Selective opioid receptor agonists: These agents target kappa- and/or mu-opioid receptors on peripheral pain-sensing neurons in order to inhibit itch without activating other opioid receptors linked to classic opioid side effects such as respiratory depression, constipation, and addiction. These selective agents are essentially designed to be nonnarcotic opioids.

One such agent is nalfurafine, an oral kappa-opioid receptor agonist marketed in Japan for treatment of uremic pruritus in patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing hemodialysis and for refractory pruritus in chronic liver disease. The drug is in phase II studies in the United States.

Nalbuphine, a dual kappa-opiod agonist and partial mu-opioid antagonist, is Food and Drug Administration–approved as an injectable agent, known as Nubain, for moderate to severe pain. An investigational extended-release tablet formulation has successfully completed a U.S. multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II/III clinical trial in hemodialysis patients with severe chronic uremic pruritus and a phase II study in patients with prurigo nodularis. Because the drug was effective in two conditions having very different sources of itch, it is likely to be of benefit in many forms of severe chronic pruritus, Dr. Ständer said.

She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EADV

Rhinovirus most often caused HA-VRIs in two hospitals

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Health care–associated viral respiratory infections (HA-VRIs) were common in two pediatric hospitals, with rhinovirus the most frequent cause of the infections in a 3-year analysis.

The incidence rate of laboratory-confirmed HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of the hospitals’ patient data. Forty-eight percent of all 323 HA-VRI cases were caused by rhinovirus, with an overall incidence rate of 0.72/1,000 patient-days. Additionally, rhinovirus was the most frequently identified virus in cases of HA-VRI in all units of both hospitals, followed by parainfluenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus. An exception was the medical/surgical ward of Steven and Alexandra Cohen Children’s Medical Center (CCMC) of New York; in this unit of the CCMC, the incidence rate of parainfluenza virus was higher than that of rhinovirus (0.21/1,000 patient-days vs. 0.15/1,000 patient-days) (J Ped Inf Dis. 2016. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw072).

The researchers used infection prevention and control surveillance databases from Montreal Children’s Hospital (MCH) in Quebec and the CCMC to identify HA-VRIs that occurred between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, In both hospitals, HAIs were attributed to the unit to which the patient was admitted at the time of transmission. Both hospitals used a multiplex nucleic acid amplification test for respiratory virus detection on nasopharyngeal swabs or aspirates.

“An HA-VRI with an onset of symptoms after hospital discharge would be detected and included only for patients who presented to the emergency department or were readmitted for VRI and tested,” according to Caroline Quach, MD, of the Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill University Health Centre, Quebec, and her colleagues.

The HA-VRI rate was 1.91/1,000 patient-days at Montreal Children’s Hospital, compared with 0.80/1,000 patient-days at the CCMC (P less than .0001). At the CCMC, the HA-VRI incidence rate was lowest in the neonatal ICU, but at Montgomery Children’s Hospital, the hematology/oncology ward had the lowest rate of HA-VRI.

Having less than 50% single rooms in a given unit was associated with a statistically significantly higher rate of HA-VRI, after the investigators adjusted for unit type and took the correlation of HA-VRI rates within a hospital into consideration. The study authors’ model predicted that units with less than 50% single rooms have 1.33 times higher HA-VRI rates than units with at least 50% single rooms, regardless of unit type.

Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The incidence rate of HA-VRIs was 1.29/1,000 patient-days in an examination of two pediatric hospitals’ patient data between April 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013.

Data source: A retrospective comparison of two hospitals’ 3 years of infection prevention and control surveillance data.

Disclosures: Dr. Quach has received funding from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sage, and AbbVie for an unrelated research project, while the other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Vent bundles and ventilator-associated pneumonia outcomes

Clinical question: Are the components of the ventilator bundles (VBs) associated with better outcomes for patients?

Background: VBs have been shown to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). However, most of the studies have analyzed outcomes based on the whole bundle without considering each individual component.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Spontaneous breathing trials were associated with lower hazards for VAEs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.76; P less than .001) and infection-related ventilator-associated complications (IVACs) (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37-1.00; P = .05). Head-of-bed elevation (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.14-1.68; P = 0.001) and thromboembolism prophylaxis (HR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.80-3.66; P less than .001) were associated with less time to extubation.

Oral care with chlorhexidine was associated with lower hazards for IVACs (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.36-1.00; P = .05) and for VAPs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27-1.14; P = .11) but an increased risk for ventilator mortality (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.15-2.31; P = .006). Stress ulcer prophylaxis was associated with higher risk for VAP (HR, 7.69; 95% CI, 1.44-41.10; P = .02).

Bottom line: Standard VB components merit revision to increase emphasis on beneficial components and eliminate potentially harmful ones.

Citation: Klompas M, Li L, Kleinman K, Szumita PM, Massaro AF. Association between ventilator bundle components and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1277-1283.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Are the components of the ventilator bundles (VBs) associated with better outcomes for patients?

Background: VBs have been shown to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). However, most of the studies have analyzed outcomes based on the whole bundle without considering each individual component.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Spontaneous breathing trials were associated with lower hazards for VAEs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.76; P less than .001) and infection-related ventilator-associated complications (IVACs) (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37-1.00; P = .05). Head-of-bed elevation (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.14-1.68; P = 0.001) and thromboembolism prophylaxis (HR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.80-3.66; P less than .001) were associated with less time to extubation.

Oral care with chlorhexidine was associated with lower hazards for IVACs (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.36-1.00; P = .05) and for VAPs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27-1.14; P = .11) but an increased risk for ventilator mortality (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.15-2.31; P = .006). Stress ulcer prophylaxis was associated with higher risk for VAP (HR, 7.69; 95% CI, 1.44-41.10; P = .02).

Bottom line: Standard VB components merit revision to increase emphasis on beneficial components and eliminate potentially harmful ones.

Citation: Klompas M, Li L, Kleinman K, Szumita PM, Massaro AF. Association between ventilator bundle components and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1277-1283.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Are the components of the ventilator bundles (VBs) associated with better outcomes for patients?

Background: VBs have been shown to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). However, most of the studies have analyzed outcomes based on the whole bundle without considering each individual component.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

Spontaneous breathing trials were associated with lower hazards for VAEs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.76; P less than .001) and infection-related ventilator-associated complications (IVACs) (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.37-1.00; P = .05). Head-of-bed elevation (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.14-1.68; P = 0.001) and thromboembolism prophylaxis (HR, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.80-3.66; P less than .001) were associated with less time to extubation.

Oral care with chlorhexidine was associated with lower hazards for IVACs (HR, 0.60; 95% CI 0.36-1.00; P = .05) and for VAPs (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27-1.14; P = .11) but an increased risk for ventilator mortality (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.15-2.31; P = .006). Stress ulcer prophylaxis was associated with higher risk for VAP (HR, 7.69; 95% CI, 1.44-41.10; P = .02).

Bottom line: Standard VB components merit revision to increase emphasis on beneficial components and eliminate potentially harmful ones.

Citation: Klompas M, Li L, Kleinman K, Szumita PM, Massaro AF. Association between ventilator bundle components and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1277-1283.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Overnight extubations associated with worse outcomes

Clinical question: Are overnight extubations in intensive care units associated with higher mortality rate?

Background: Little is known about the frequency, safety, and effectiveness of overnight extubations in the ICU.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: One-hundred sixty-five ICUs in the United States.

Synopsis: Using the Project IMPACT database, 97,844 adults undergoing mechanical ventilation (MV) admitted to ICUs were studied. Overnight extubation was defined as occurring between 7 p.m. and 6:59 a.m. Primary outcome was reintubation; secondary outcomes were ICU and hospital mortality and ICU and hospital length of stay.

Only one-fifth of patients with MV underwent overnight extubations. For MV duration of at least 12 hours, rates of reintubation were higher for patients undergoing overnight extubation (14.6% vs. 12.4%; P less than .001). Mortality was significantly higher for patients undergoing overnight versus daytime extubation in the ICU (11.2% vs. 6.1%; P less than.001) and in the hospital (16.0% vs. 11.1%; P less than .001). Length of ICU and hospital stays did not differ.

Bottom line: Overnight extubations occur in one of five patients in U.S. ICUs and are associated with worse outcomes, compared with daytime extubations.

Citation: Gershengorn HB, Scales DC, Kramer A, Wunsch H. Association between overnight extubations and outcomes in the intensive care unit. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1651-1660.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Are overnight extubations in intensive care units associated with higher mortality rate?

Background: Little is known about the frequency, safety, and effectiveness of overnight extubations in the ICU.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: One-hundred sixty-five ICUs in the United States.

Synopsis: Using the Project IMPACT database, 97,844 adults undergoing mechanical ventilation (MV) admitted to ICUs were studied. Overnight extubation was defined as occurring between 7 p.m. and 6:59 a.m. Primary outcome was reintubation; secondary outcomes were ICU and hospital mortality and ICU and hospital length of stay.

Only one-fifth of patients with MV underwent overnight extubations. For MV duration of at least 12 hours, rates of reintubation were higher for patients undergoing overnight extubation (14.6% vs. 12.4%; P less than .001). Mortality was significantly higher for patients undergoing overnight versus daytime extubation in the ICU (11.2% vs. 6.1%; P less than.001) and in the hospital (16.0% vs. 11.1%; P less than .001). Length of ICU and hospital stays did not differ.

Bottom line: Overnight extubations occur in one of five patients in U.S. ICUs and are associated with worse outcomes, compared with daytime extubations.

Citation: Gershengorn HB, Scales DC, Kramer A, Wunsch H. Association between overnight extubations and outcomes in the intensive care unit. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1651-1660.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

Clinical question: Are overnight extubations in intensive care units associated with higher mortality rate?

Background: Little is known about the frequency, safety, and effectiveness of overnight extubations in the ICU.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: One-hundred sixty-five ICUs in the United States.

Synopsis: Using the Project IMPACT database, 97,844 adults undergoing mechanical ventilation (MV) admitted to ICUs were studied. Overnight extubation was defined as occurring between 7 p.m. and 6:59 a.m. Primary outcome was reintubation; secondary outcomes were ICU and hospital mortality and ICU and hospital length of stay.

Only one-fifth of patients with MV underwent overnight extubations. For MV duration of at least 12 hours, rates of reintubation were higher for patients undergoing overnight extubation (14.6% vs. 12.4%; P less than .001). Mortality was significantly higher for patients undergoing overnight versus daytime extubation in the ICU (11.2% vs. 6.1%; P less than.001) and in the hospital (16.0% vs. 11.1%; P less than .001). Length of ICU and hospital stays did not differ.

Bottom line: Overnight extubations occur in one of five patients in U.S. ICUs and are associated with worse outcomes, compared with daytime extubations.

Citation: Gershengorn HB, Scales DC, Kramer A, Wunsch H. Association between overnight extubations and outcomes in the intensive care unit. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1651-1660.

Dr. Mosetti is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and a hospitalist at University of Miami Hospital and Jackson Memorial Hospital.

High consumption of red meat increases diverticulitis risk in men

Men who consume higher quantities of red meat are at an increased risk of developing diverticulitis, especially if they’re eating unprocessed red meat, according to a new study published in Gut.

“In our prior analysis from a large prospective cohort study, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), we found that red meat intake, independent of fiber, may be associated with a composite outcome of symptomatic diverticular disease, which included 385 incident cases over 4 years of follow-up,” wrote the authors, led by Andrew T. Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Dr. Chan added that “in the present study, we updated this analysis, which allowed us to prospectively examine the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry, and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis in 764 cases over 26 years of follow-up.”

Dr. Chan and his coinvestigators conducted a prospective cohort study using subjects from the ongoing HPFS. Men who already had a diagnosis of diverticulitis, associated complications, inflammatory bowel disease, or a GI-related cancer at baseline were excluded from this analysis, leaving 46,461 eligible subjects. Of those, 764 developed diverticulitis.

The entirety of the follow-up period constituted 651,970 person-years. Average servings of total red meat per week were 1.2 in quintile 1, compared to 5.3 in quintile 3 and 13.5 in quintile 5. Those in the highest quintile had a multivariable risk ratio of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.19-2.11; P = .01), indicating a significantly higher risk for developing diverticulitis. In terms of unprocessed red meat, the average number of servings per week were 0.8 for the lower quintile, 3.2 for quintile 3, and 8.6 for quintile 5, yielding a risk ratio of 1.51 (95% CI, 1.12-2.03, P = .03) when comparing the highest and lowest cohorts. The increase in risk, however, leveled off after about 6 servings of red meat per week, and was found to be nonlinear (P = .002). Those who ate more servings of poultry or fish did not have a higher risk of diverticulitis.

“We also observed that unprocessed red meat, but not processed red meat, was the primary driver for the association between total red meat and risk of diverticulitis,” the authors explained. “Compared with processed meat, unprocessed meat (e.g., steak) is usually consumed in larger portions, which could lead to a larger undigested piece in the large bowel and induce different changes in colonic microbiota [and] higher cooking temperatures used in the preparation of unprocessed meat may influence bacterial composition or proinflammatory mediators in the colon.”

Although medical information and self-reports were validated, there are inherent possible limitations to self-reported data, such as misremembering the amount of meat consumed or reporting incorrect amounts. Residual confounding may have occurred despite adjustment of the data to account for it.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Men who consume higher quantities of red meat are at an increased risk of developing diverticulitis, especially if they’re eating unprocessed red meat, according to a new study published in Gut.

“In our prior analysis from a large prospective cohort study, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), we found that red meat intake, independent of fiber, may be associated with a composite outcome of symptomatic diverticular disease, which included 385 incident cases over 4 years of follow-up,” wrote the authors, led by Andrew T. Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Dr. Chan added that “in the present study, we updated this analysis, which allowed us to prospectively examine the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry, and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis in 764 cases over 26 years of follow-up.”

Dr. Chan and his coinvestigators conducted a prospective cohort study using subjects from the ongoing HPFS. Men who already had a diagnosis of diverticulitis, associated complications, inflammatory bowel disease, or a GI-related cancer at baseline were excluded from this analysis, leaving 46,461 eligible subjects. Of those, 764 developed diverticulitis.

The entirety of the follow-up period constituted 651,970 person-years. Average servings of total red meat per week were 1.2 in quintile 1, compared to 5.3 in quintile 3 and 13.5 in quintile 5. Those in the highest quintile had a multivariable risk ratio of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.19-2.11; P = .01), indicating a significantly higher risk for developing diverticulitis. In terms of unprocessed red meat, the average number of servings per week were 0.8 for the lower quintile, 3.2 for quintile 3, and 8.6 for quintile 5, yielding a risk ratio of 1.51 (95% CI, 1.12-2.03, P = .03) when comparing the highest and lowest cohorts. The increase in risk, however, leveled off after about 6 servings of red meat per week, and was found to be nonlinear (P = .002). Those who ate more servings of poultry or fish did not have a higher risk of diverticulitis.

“We also observed that unprocessed red meat, but not processed red meat, was the primary driver for the association between total red meat and risk of diverticulitis,” the authors explained. “Compared with processed meat, unprocessed meat (e.g., steak) is usually consumed in larger portions, which could lead to a larger undigested piece in the large bowel and induce different changes in colonic microbiota [and] higher cooking temperatures used in the preparation of unprocessed meat may influence bacterial composition or proinflammatory mediators in the colon.”

Although medical information and self-reports were validated, there are inherent possible limitations to self-reported data, such as misremembering the amount of meat consumed or reporting incorrect amounts. Residual confounding may have occurred despite adjustment of the data to account for it.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Men who consume higher quantities of red meat are at an increased risk of developing diverticulitis, especially if they’re eating unprocessed red meat, according to a new study published in Gut.

“In our prior analysis from a large prospective cohort study, the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS), we found that red meat intake, independent of fiber, may be associated with a composite outcome of symptomatic diverticular disease, which included 385 incident cases over 4 years of follow-up,” wrote the authors, led by Andrew T. Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. Dr. Chan added that “in the present study, we updated this analysis, which allowed us to prospectively examine the association between consumption of meat (total red meat, red unprocessed meat, red processed meat, poultry, and fish) with risk of incident diverticulitis in 764 cases over 26 years of follow-up.”

Dr. Chan and his coinvestigators conducted a prospective cohort study using subjects from the ongoing HPFS. Men who already had a diagnosis of diverticulitis, associated complications, inflammatory bowel disease, or a GI-related cancer at baseline were excluded from this analysis, leaving 46,461 eligible subjects. Of those, 764 developed diverticulitis.

The entirety of the follow-up period constituted 651,970 person-years. Average servings of total red meat per week were 1.2 in quintile 1, compared to 5.3 in quintile 3 and 13.5 in quintile 5. Those in the highest quintile had a multivariable risk ratio of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.19-2.11; P = .01), indicating a significantly higher risk for developing diverticulitis. In terms of unprocessed red meat, the average number of servings per week were 0.8 for the lower quintile, 3.2 for quintile 3, and 8.6 for quintile 5, yielding a risk ratio of 1.51 (95% CI, 1.12-2.03, P = .03) when comparing the highest and lowest cohorts. The increase in risk, however, leveled off after about 6 servings of red meat per week, and was found to be nonlinear (P = .002). Those who ate more servings of poultry or fish did not have a higher risk of diverticulitis.

“We also observed that unprocessed red meat, but not processed red meat, was the primary driver for the association between total red meat and risk of diverticulitis,” the authors explained. “Compared with processed meat, unprocessed meat (e.g., steak) is usually consumed in larger portions, which could lead to a larger undigested piece in the large bowel and induce different changes in colonic microbiota [and] higher cooking temperatures used in the preparation of unprocessed meat may influence bacterial composition or proinflammatory mediators in the colon.”

Although medical information and self-reports were validated, there are inherent possible limitations to self-reported data, such as misremembering the amount of meat consumed or reporting incorrect amounts. Residual confounding may have occurred despite adjustment of the data to account for it.

The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Men with the highest consumption of red meat per week had a risk ratio of 1.58 (95% CI, 1.19-2.11, P = .01) compared to those with the lowest consumption, with an RR of 1.51 (95% CI, 1.12-2.03, P = .03) when comparing unprocessed red meat consumption.

Data source: Prospective cohort study of 51,529 men aged 40-75 years, in the United States.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Macitentan boosts quality of life in PAH patients

Macitentan, a recent addition to the drugs that treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), improves and stabilizes quality of life for patients with the condition, according to an industry-funded study.

Macitentan (Opsumit) remains tremendously expensive, costing as much as $100,000 per year in the United States, and the study provides little in the way of direct comparison to other drugs in its class. Still, the drug’s effects on quality of life are dramatic, said study lead author Sanjay Mehta, MD, FRCPC, FCCP, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and director of the Southwest Ontario Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic at the London Health Sciences Center in London, Ont.

Researchers found that those who took the 10-mg dose, versus placebo, reported significant improvement in seven of eight quality-of-life domains, and in physical and mental components scores, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). In addition, the study linked 10-mg doses, versus placebo, to a lower risk of a decline of three points or more in the physical component score (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P less than .0001] and the mental component scores (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95; P = .0173) until end of treatment.

“The drug has shown stability in patients’ quality of life over 6 months and 12 months,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview. “I can’t cure anybody, and they’ll get worse at some point, but I can improve them. They physically feel better, they’re less short of breath with less body pain, and they feel better psychologically.”

Macitentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2013 following a study that year (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:809-18) that linked 10-mg doses to a significantly lower risk of death and various complications, compared with placebo and the 3-mg dose. The new study (Chest. 2017 Jan;151[1]:106-18), is an analysis of data from the 2013 study.

The PAH patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: macitentan 10 mg once daily (234), macitentan 3 mg (237), and placebo (239). The study examined responses from 710 patients (76.9% were female, 55.2% were white, mean age was 45.5) to the SF-36 at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and end of treatment.

Dr. Mehta noted that macitentan has not been clinically compared to the other drugs. The study, however, notes that it is the first PAH treatment to show improvement in seven of eight domains in the quality-of-life survey.

The new study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals, maker of macitentan. Dr. Mehta has received consulting and speaking fees and institutional support for clinical trials from Actelion, among other drug companies. The other authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Actelion.

Macitentan, a recent addition to the drugs that treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), improves and stabilizes quality of life for patients with the condition, according to an industry-funded study.

Macitentan (Opsumit) remains tremendously expensive, costing as much as $100,000 per year in the United States, and the study provides little in the way of direct comparison to other drugs in its class. Still, the drug’s effects on quality of life are dramatic, said study lead author Sanjay Mehta, MD, FRCPC, FCCP, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and director of the Southwest Ontario Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic at the London Health Sciences Center in London, Ont.

Researchers found that those who took the 10-mg dose, versus placebo, reported significant improvement in seven of eight quality-of-life domains, and in physical and mental components scores, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). In addition, the study linked 10-mg doses, versus placebo, to a lower risk of a decline of three points or more in the physical component score (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P less than .0001] and the mental component scores (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95; P = .0173) until end of treatment.

“The drug has shown stability in patients’ quality of life over 6 months and 12 months,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview. “I can’t cure anybody, and they’ll get worse at some point, but I can improve them. They physically feel better, they’re less short of breath with less body pain, and they feel better psychologically.”

Macitentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2013 following a study that year (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:809-18) that linked 10-mg doses to a significantly lower risk of death and various complications, compared with placebo and the 3-mg dose. The new study (Chest. 2017 Jan;151[1]:106-18), is an analysis of data from the 2013 study.

The PAH patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: macitentan 10 mg once daily (234), macitentan 3 mg (237), and placebo (239). The study examined responses from 710 patients (76.9% were female, 55.2% were white, mean age was 45.5) to the SF-36 at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and end of treatment.

Dr. Mehta noted that macitentan has not been clinically compared to the other drugs. The study, however, notes that it is the first PAH treatment to show improvement in seven of eight domains in the quality-of-life survey.

The new study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals, maker of macitentan. Dr. Mehta has received consulting and speaking fees and institutional support for clinical trials from Actelion, among other drug companies. The other authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Actelion.

Macitentan, a recent addition to the drugs that treat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), improves and stabilizes quality of life for patients with the condition, according to an industry-funded study.

Macitentan (Opsumit) remains tremendously expensive, costing as much as $100,000 per year in the United States, and the study provides little in the way of direct comparison to other drugs in its class. Still, the drug’s effects on quality of life are dramatic, said study lead author Sanjay Mehta, MD, FRCPC, FCCP, professor of medicine at the University of Western Ontario and director of the Southwest Ontario Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic at the London Health Sciences Center in London, Ont.

Researchers found that those who took the 10-mg dose, versus placebo, reported significant improvement in seven of eight quality-of-life domains, and in physical and mental components scores, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). In addition, the study linked 10-mg doses, versus placebo, to a lower risk of a decline of three points or more in the physical component score (hazard ratio [HR], 0.60; 95% CI, 0.47-0.76; P less than .0001] and the mental component scores (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61-0.95; P = .0173) until end of treatment.

“The drug has shown stability in patients’ quality of life over 6 months and 12 months,” Dr. Mehta said in an interview. “I can’t cure anybody, and they’ll get worse at some point, but I can improve them. They physically feel better, they’re less short of breath with less body pain, and they feel better psychologically.”

Macitentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, received Food and Drug Administration approval in 2013 following a study that year (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 29;369[9]:809-18) that linked 10-mg doses to a significantly lower risk of death and various complications, compared with placebo and the 3-mg dose. The new study (Chest. 2017 Jan;151[1]:106-18), is an analysis of data from the 2013 study.

The PAH patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: macitentan 10 mg once daily (234), macitentan 3 mg (237), and placebo (239). The study examined responses from 710 patients (76.9% were female, 55.2% were white, mean age was 45.5) to the SF-36 at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and end of treatment.

Dr. Mehta noted that macitentan has not been clinically compared to the other drugs. The study, however, notes that it is the first PAH treatment to show improvement in seven of eight domains in the quality-of-life survey.

The new study was funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals, maker of macitentan. Dr. Mehta has received consulting and speaking fees and institutional support for clinical trials from Actelion, among other drug companies. The other authors report various disclosures, including relationships with Actelion.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Macitentan improves and stabilizes quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Major finding: Patients who took 10 mg daily macitentan improved in seven of eight quality-of-life domains and in combined physical and mental health measures.

Data source: Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III study of 710 patients (76.9% female, 55.2% white, mean age 45.5) assigned to placebo, macitentan 3 mg, or macitentan 10 mg once daily.

Disclosures: Actelion Pharmaceuticals, maker of macitentan, funded the study. The authors disclosed ties with Actelion.

Using a Modified Ball-Tip Guide Rod to Equalize Leg Length and Restore Femoral Offset

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during surgery.

- Intraoperative fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip arthroplasty components.

- Numerous measuring devices have been designed to help restore leg length, but in many cases the purchase cost and required maintenance outweigh their utility.

- A radiopaque line generated by the guide rod serves as a reference point that permits immediate objective comparison of femoral leg length and offset intraoperatively.

- The modified ball-tip guide rod is relatively inexpensive and has several practical purposes in total joint surgery.

Patient satisfaction scores after total hip arthroplasty (THA) approach 100%.1 Goals of this surgery include pain alleviation, motion restoration, and normalization of leg-length inequality. Asymmetric leg lengths are associated with nerve traction injuries, lower extremity joint pain, sacroiliac discomfort, low back pain, and patient dissatisfaction.1-3 For these reasons, postoperative leg-length discrepancy has become the most common reason for THA-related litigation.1,4

With preoperative education, patients and surgeons can discuss realistic THA goals and expectations. Besides ensuring that the correct tools and implants are available for the procedure, radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during cases. For instance, an extremity may need to be lengthened during the surgery in order to generate the amount of soft-tissue tension needed to convey adequate stability to the hip joint.

In asymptomatic populations, lower extremity leg lengths inherently vary by an average of 5 mm.5 Studies have found normal populations are unable to accurately perceive a leg-length inequality of <1 cm.3,6,7 Lengthening an extremity >2.5 cm causes sciatic nerve symptoms.2 Patients may notice a leg-length discrepancy during the first few months after hip replacement, but this perception often subsides as gait normalizes and soft tissues acclimatize.

Our hospital uses a special arthroplasty table and intraoperative fluoroscopy for direct anterior (DA) THA cases. The table permits the operative extremity to undergo traction and the necessary mobility for proximal femur exposure. Fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip components.8We have developed an innovative use for a ball-tip guide rod (3.0 mm × 1000 mm; Smith & Nephew) to help accurately restore leg length and femoral offset after DA-THA. The ball-tip guide rod was modified to a length of 500 mm and rough edges were smoothed.

Technique

After the patient is prepared and draped in standard fashion on the operating table, a 10-cm skin incision is made directly over the proximal aspect of the tensor fascia lata muscle. Soft tissues are dissected down to the hip capsule, which is then incised and tagged for closure at the end of the case.

The fluoroscopic C-arm is sterilely draped and positioned from the nonoperative side. The image intensifier is centered over the pubic symphysis and lowered within 1 inch of the perineal post and surgical drapes. The C-arm unit is then aimed 10° to 15° cephalad until the size and orientation of the obturator foramens on fluoroscopic imaging coincide with the preoperative template.

Next, the modified guide rod, ball tip first, is carefully advanced toward the nonoperative side and over the surgical drapes between the pelvis and the C-arm image intensifier. Care is taken to avoid violating the sterile field by inadvertently puncturing the surgical drapes with the guide rod. The lower extremities are externally rotated 20° to bring the lesser tuberosities into profile view. With use of several fluoroscopic views, the guide rod is aligned with the inferior borders of the ischial tuberosities or the obturator foramens, whichever are more readily identified on the intraoperative images. A skin marker is then used to illustrate the position of the guide rod on the operative drapes for future reference.

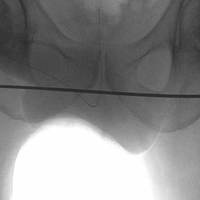

At this point, the relationship between the radiopaque guide rod and the lesser trochanters is noted to gain a sense of native femoral leg length and offset, and the image (Figure 1) is saved in the C-arm computer for later recall and comparison views.

Next, the femoral neck osteotomy is performed according to the preoperative template. Acetabular preparation and component insertion are completed under fluoroscopic guidance.

After appropriate soft-tissue releases, the operating table is used to position the operative leg in extension, external rotation, and adduction. The femur is then sequentially broached until the template size is reached or until there is an audible change in pitch. At this point, a trial neck with head ball is fixed to the broach, and the hip is reduced.

The fluoroscopic C-arm is then repositioned over the pelvis, as previously described, with the guide rod over the pelvis and tangential to the ischial tuberosities. A new image (Figure 2) is obtained with the trial components in place.

The radiopaque line generated by the guide rod represents a reference point that permits objective comparison of femoral leg length and offset based on distance to the lesser trochanters. Different modular components can be trialed until the correct combination of variables accurately restores the desired parameters.

Once parameters are restored, trial femoral components are removed, and a corresponding monolithic femoral stem is gently impacted into the proximal femur and fitted with the appropriate head ball. A final image is obtained with the guide rod and implants in place and is saved as proof of restoration of leg length.

Discussion

Various techniques of assessing intraoperative leg length have been described, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. Relying on abductor tension or comparing leg lengths on the operating table is not always accurate and is strongly dependent on patient position.2,6

Referencing the tip of the greater trochanter to a Steinmann pin inserted into the ilium provides a precise reference point, but this invasive technique has the potential for fracture propagation through the drill hole.2,7Superimposing a trial femoral component over the proximal femur to determine the appropriate femoral neck osteotomy has been described, but this process can be difficult through a tight DA approach.9Numerous measuring devices have been designed to help restore leg length, but in many cases the purchase cost and required maintenance outweigh their utility.2 Gililland and colleagues10 developed a reusable fluoroscopic transparent grid system that significantly improves component positioning during DA-THA.

The modified ball-tip guide rod is relatively inexpensive (<$100) and has several practical purposes in total joint surgery. The guide rod historically has been used to sound the center of the femoral canal before broaching. In revision cases and in cases of poor bone stock, the tool can be used to verify that cortical perforation has not occurred during canal preparation. In this article, we describe another realistic use for the guide rod: to create, during DA-THA, a radiographic reference line that can be used to help restore leg length and femoral offset.

Several authors have mentioned surgeons’ drawing the reference line on paper printouts of intraoperative images.11 Not only is this practice fraught with potential contamination of the operative field, but valuable time is lost waiting for paper copies and putting on a new gown and gloves before reentering the sterile field.

We used to train a radiologic technician or operating room nurse to draw a computerized reference line connecting the lesser trochanters on the fluoroscopic image. Problems arose in working with revolving nursing staff and in distinguishing the thin black line on computer monitors. In contrast, the radiopaque line from the guide rod is easily differentiated on fluoroscopic images, the technique poses less of a risk to the sterile field, and proper orientation of the guide rod to obtain the appropriate reference line is entirely surgeon-dependent.

A drawback of this technique is the additional radiation exposure that occurs when extra images are obtained to ensure satisfactory alignment of the guide rod. Another issue is fluoroscopic parallax. Some machines in the operating department generate a magnetic field that can interfere with the fluoroscopy beam and thereby slightly distort the intraoperative images.8 Therefore, it is imperative that the guide rod remain perfectly straight to avoid confounding measurements.

Our modified guide rod technique is a reliable, quick, and inexpensive intraoperative tool that helps in accurately restoring leg length and femoral offset during DA-THA.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E10-E12. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

1. Whitehouse MR, Stefanovich-Lawbuary NS, Brunton LR, Blom AW. The impact of leg length discrepancy on patient satisfaction and functional outcome following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1408-1414.

2. Clark CR, Huddleston HD, Schoch EP 3rd, Thomas BJ. Leg-length discrepancy after total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(1):38-45.

3. O’Brien S, Kernohan G, Fitzpatrick C, Hill J, Beverland D. Perception of imposed leg length inequality in normal subjects. Hip Int. 2010;20(4):505-511.

4. Hofmann AA, Skrzynski MC. Leg-length inequality and nerve palsy in total hip arthroplasty: a lawyer awaits! Orthopedics. 2000;23(9):943-944.

5. Knutson GA. Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: a review and recommendation for clinical decision-making. Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropr Osteopat. 2005;13:11.

6. Iagulli ND, Mallory TH, Berend KR, et al. A simple and accurate method for determining leg length in primary total hip arthroplasty. Am J Orthop. 2006;35(10):455-457.

7. Ranawat CS, Rao RR, Rodriguez JA, Bhende HS. Correction of limb-length inequality during total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(6):715-720.

8. Weber M, Woerner M, Springorum R, et al. Fluoroscopy and imageless navigation enable an equivalent reconstruction of leg length and global and femoral offset in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(10):3150-3158.

9. Alazzawi S, Douglas SL, Haddad FS. A novel intra-operative technique to achieve accurate leg length and femoral offset during total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(4):281-282.

10. Gililland JM, Anderson LA, Boffeli SL, Pelt CE, Peters CL, Kubiak EN. A fluoroscopic grid in supine total hip arthroplasty: improving cup position, limb length, and hip offset. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):111-116.

11. Matta JM, Shahrdar C, Ferguson T. Single-incision anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty on an orthopaedic table. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(441):115-124.

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during surgery.

- Intraoperative fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip arthroplasty components.

- Numerous measuring devices have been designed to help restore leg length, but in many cases the purchase cost and required maintenance outweigh their utility.

- A radiopaque line generated by the guide rod serves as a reference point that permits immediate objective comparison of femoral leg length and offset intraoperatively.

- The modified ball-tip guide rod is relatively inexpensive and has several practical purposes in total joint surgery.

Patient satisfaction scores after total hip arthroplasty (THA) approach 100%.1 Goals of this surgery include pain alleviation, motion restoration, and normalization of leg-length inequality. Asymmetric leg lengths are associated with nerve traction injuries, lower extremity joint pain, sacroiliac discomfort, low back pain, and patient dissatisfaction.1-3 For these reasons, postoperative leg-length discrepancy has become the most common reason for THA-related litigation.1,4

With preoperative education, patients and surgeons can discuss realistic THA goals and expectations. Besides ensuring that the correct tools and implants are available for the procedure, radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during cases. For instance, an extremity may need to be lengthened during the surgery in order to generate the amount of soft-tissue tension needed to convey adequate stability to the hip joint.

In asymptomatic populations, lower extremity leg lengths inherently vary by an average of 5 mm.5 Studies have found normal populations are unable to accurately perceive a leg-length inequality of <1 cm.3,6,7 Lengthening an extremity >2.5 cm causes sciatic nerve symptoms.2 Patients may notice a leg-length discrepancy during the first few months after hip replacement, but this perception often subsides as gait normalizes and soft tissues acclimatize.

Our hospital uses a special arthroplasty table and intraoperative fluoroscopy for direct anterior (DA) THA cases. The table permits the operative extremity to undergo traction and the necessary mobility for proximal femur exposure. Fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip components.8We have developed an innovative use for a ball-tip guide rod (3.0 mm × 1000 mm; Smith & Nephew) to help accurately restore leg length and femoral offset after DA-THA. The ball-tip guide rod was modified to a length of 500 mm and rough edges were smoothed.

Technique

After the patient is prepared and draped in standard fashion on the operating table, a 10-cm skin incision is made directly over the proximal aspect of the tensor fascia lata muscle. Soft tissues are dissected down to the hip capsule, which is then incised and tagged for closure at the end of the case.

The fluoroscopic C-arm is sterilely draped and positioned from the nonoperative side. The image intensifier is centered over the pubic symphysis and lowered within 1 inch of the perineal post and surgical drapes. The C-arm unit is then aimed 10° to 15° cephalad until the size and orientation of the obturator foramens on fluoroscopic imaging coincide with the preoperative template.

Next, the modified guide rod, ball tip first, is carefully advanced toward the nonoperative side and over the surgical drapes between the pelvis and the C-arm image intensifier. Care is taken to avoid violating the sterile field by inadvertently puncturing the surgical drapes with the guide rod. The lower extremities are externally rotated 20° to bring the lesser tuberosities into profile view. With use of several fluoroscopic views, the guide rod is aligned with the inferior borders of the ischial tuberosities or the obturator foramens, whichever are more readily identified on the intraoperative images. A skin marker is then used to illustrate the position of the guide rod on the operative drapes for future reference.

At this point, the relationship between the radiopaque guide rod and the lesser trochanters is noted to gain a sense of native femoral leg length and offset, and the image (Figure 1) is saved in the C-arm computer for later recall and comparison views.

Next, the femoral neck osteotomy is performed according to the preoperative template. Acetabular preparation and component insertion are completed under fluoroscopic guidance.

After appropriate soft-tissue releases, the operating table is used to position the operative leg in extension, external rotation, and adduction. The femur is then sequentially broached until the template size is reached or until there is an audible change in pitch. At this point, a trial neck with head ball is fixed to the broach, and the hip is reduced.

The fluoroscopic C-arm is then repositioned over the pelvis, as previously described, with the guide rod over the pelvis and tangential to the ischial tuberosities. A new image (Figure 2) is obtained with the trial components in place.

The radiopaque line generated by the guide rod represents a reference point that permits objective comparison of femoral leg length and offset based on distance to the lesser trochanters. Different modular components can be trialed until the correct combination of variables accurately restores the desired parameters.

Once parameters are restored, trial femoral components are removed, and a corresponding monolithic femoral stem is gently impacted into the proximal femur and fitted with the appropriate head ball. A final image is obtained with the guide rod and implants in place and is saved as proof of restoration of leg length.

Discussion

Various techniques of assessing intraoperative leg length have been described, and each has its advantages and disadvantages. Relying on abductor tension or comparing leg lengths on the operating table is not always accurate and is strongly dependent on patient position.2,6

Referencing the tip of the greater trochanter to a Steinmann pin inserted into the ilium provides a precise reference point, but this invasive technique has the potential for fracture propagation through the drill hole.2,7Superimposing a trial femoral component over the proximal femur to determine the appropriate femoral neck osteotomy has been described, but this process can be difficult through a tight DA approach.9Numerous measuring devices have been designed to help restore leg length, but in many cases the purchase cost and required maintenance outweigh their utility.2 Gililland and colleagues10 developed a reusable fluoroscopic transparent grid system that significantly improves component positioning during DA-THA.

The modified ball-tip guide rod is relatively inexpensive (<$100) and has several practical purposes in total joint surgery. The guide rod historically has been used to sound the center of the femoral canal before broaching. In revision cases and in cases of poor bone stock, the tool can be used to verify that cortical perforation has not occurred during canal preparation. In this article, we describe another realistic use for the guide rod: to create, during DA-THA, a radiographic reference line that can be used to help restore leg length and femoral offset.

Several authors have mentioned surgeons’ drawing the reference line on paper printouts of intraoperative images.11 Not only is this practice fraught with potential contamination of the operative field, but valuable time is lost waiting for paper copies and putting on a new gown and gloves before reentering the sterile field.

We used to train a radiologic technician or operating room nurse to draw a computerized reference line connecting the lesser trochanters on the fluoroscopic image. Problems arose in working with revolving nursing staff and in distinguishing the thin black line on computer monitors. In contrast, the radiopaque line from the guide rod is easily differentiated on fluoroscopic images, the technique poses less of a risk to the sterile field, and proper orientation of the guide rod to obtain the appropriate reference line is entirely surgeon-dependent.

A drawback of this technique is the additional radiation exposure that occurs when extra images are obtained to ensure satisfactory alignment of the guide rod. Another issue is fluoroscopic parallax. Some machines in the operating department generate a magnetic field that can interfere with the fluoroscopy beam and thereby slightly distort the intraoperative images.8 Therefore, it is imperative that the guide rod remain perfectly straight to avoid confounding measurements.

Our modified guide rod technique is a reliable, quick, and inexpensive intraoperative tool that helps in accurately restoring leg length and femoral offset during DA-THA.

Am J Orthop. 2017;46(1):E10-E12. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2017. All rights reserved.

Take-Home Points

- Preoperative radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during surgery.

- Intraoperative fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip arthroplasty components.

- Numerous measuring devices have been designed to help restore leg length, but in many cases the purchase cost and required maintenance outweigh their utility.

- A radiopaque line generated by the guide rod serves as a reference point that permits immediate objective comparison of femoral leg length and offset intraoperatively.

- The modified ball-tip guide rod is relatively inexpensive and has several practical purposes in total joint surgery.

Patient satisfaction scores after total hip arthroplasty (THA) approach 100%.1 Goals of this surgery include pain alleviation, motion restoration, and normalization of leg-length inequality. Asymmetric leg lengths are associated with nerve traction injuries, lower extremity joint pain, sacroiliac discomfort, low back pain, and patient dissatisfaction.1-3 For these reasons, postoperative leg-length discrepancy has become the most common reason for THA-related litigation.1,4

With preoperative education, patients and surgeons can discuss realistic THA goals and expectations. Besides ensuring that the correct tools and implants are available for the procedure, radiographic templating alerts surgeons to certain intraoperative issues that may arise during cases. For instance, an extremity may need to be lengthened during the surgery in order to generate the amount of soft-tissue tension needed to convey adequate stability to the hip joint.

In asymptomatic populations, lower extremity leg lengths inherently vary by an average of 5 mm.5 Studies have found normal populations are unable to accurately perceive a leg-length inequality of <1 cm.3,6,7 Lengthening an extremity >2.5 cm causes sciatic nerve symptoms.2 Patients may notice a leg-length discrepancy during the first few months after hip replacement, but this perception often subsides as gait normalizes and soft tissues acclimatize.

Our hospital uses a special arthroplasty table and intraoperative fluoroscopy for direct anterior (DA) THA cases. The table permits the operative extremity to undergo traction and the necessary mobility for proximal femur exposure. Fluoroscopy has been shown to significantly improve the position and orientation of the implanted hip components.8We have developed an innovative use for a ball-tip guide rod (3.0 mm × 1000 mm; Smith & Nephew) to help accurately restore leg length and femoral offset after DA-THA. The ball-tip guide rod was modified to a length of 500 mm and rough edges were smoothed.

Technique

After the patient is prepared and draped in standard fashion on the operating table, a 10-cm skin incision is made directly over the proximal aspect of the tensor fascia lata muscle. Soft tissues are dissected down to the hip capsule, which is then incised and tagged for closure at the end of the case.

The fluoroscopic C-arm is sterilely draped and positioned from the nonoperative side. The image intensifier is centered over the pubic symphysis and lowered within 1 inch of the perineal post and surgical drapes. The C-arm unit is then aimed 10° to 15° cephalad until the size and orientation of the obturator foramens on fluoroscopic imaging coincide with the preoperative template.

Next, the modified guide rod, ball tip first, is carefully advanced toward the nonoperative side and over the surgical drapes between the pelvis and the C-arm image intensifier. Care is taken to avoid violating the sterile field by inadvertently puncturing the surgical drapes with the guide rod. The lower extremities are externally rotated 20° to bring the lesser tuberosities into profile view. With use of several fluoroscopic views, the guide rod is aligned with the inferior borders of the ischial tuberosities or the obturator foramens, whichever are more readily identified on the intraoperative images. A skin marker is then used to illustrate the position of the guide rod on the operative drapes for future reference.

At this point, the relationship between the radiopaque guide rod and the lesser trochanters is noted to gain a sense of native femoral leg length and offset, and the image (Figure 1) is saved in the C-arm computer for later recall and comparison views.

Next, the femoral neck osteotomy is performed according to the preoperative template. Acetabular preparation and component insertion are completed under fluoroscopic guidance.

After appropriate soft-tissue releases, the operating table is used to position the operative leg in extension, external rotation, and adduction. The femur is then sequentially broached until the template size is reached or until there is an audible change in pitch. At this point, a trial neck with head ball is fixed to the broach, and the hip is reduced.