User login

Friable Warty Plaque on the Heel

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

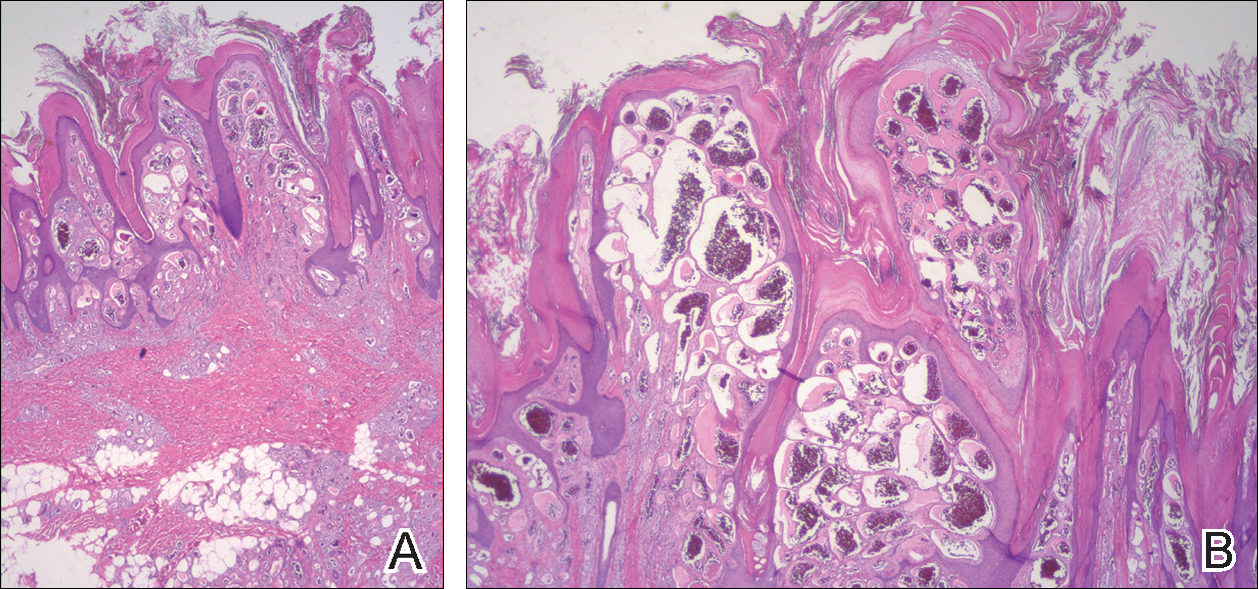

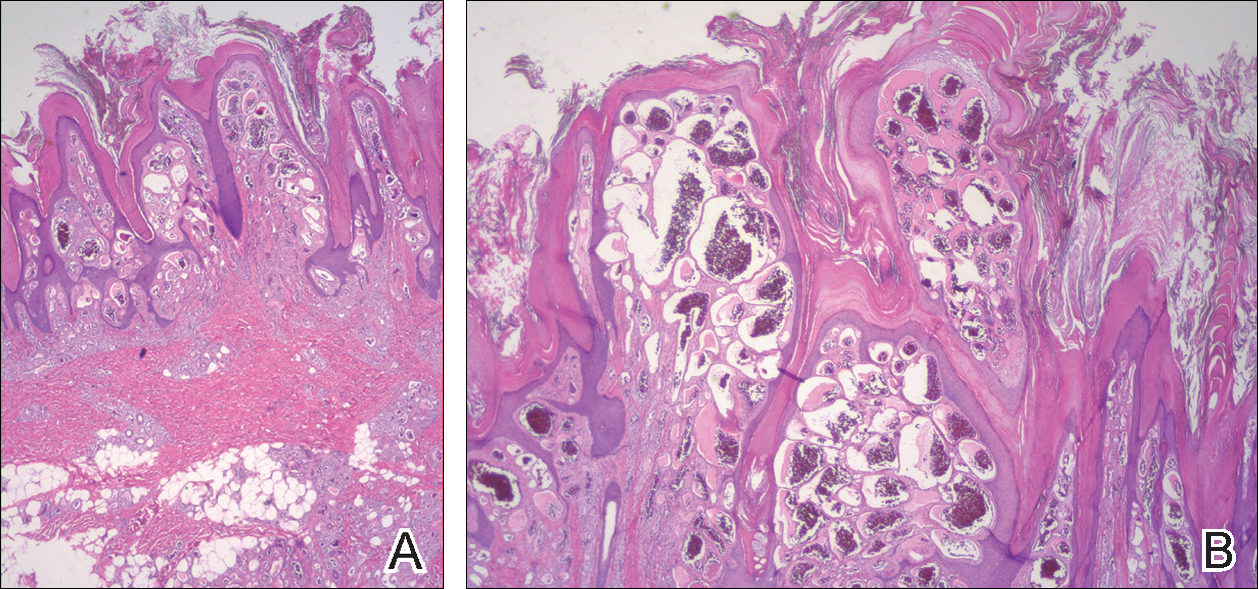

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

The Diagnosis: Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma (VH) is a rare vascular anomaly that has not been definitively delineated as a malformation or a tumor, as it has features of both. Verrucous hemangioma presents at birth as a compressible soft mass with a red violaceous hue favoring the legs.1,2 Over time VH will develop a warty, friable, and keratotic surface that can begin to evolve as early as 6 months or as late as 34 years of age.3 Verrucous hemangioma does not involute and tends to grow proportionally with the patient. Thus, VH classically has been considered a vascular malformation.

On histopathology VH shows collections of uniform, thin-walled vessels with a multilamellated basement membrane throughout the dermis, similar to an infantile hemangioma (IH). These lesions extend deep into the subcutaneous tissue and often involve the underlying fascia. The papillary dermis has large ectatic vessels, while the epidermis displays verrucous hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and irregular acanthosis without viral change (Figure).4,5 The superficial component can resemble an angiokeratoma; however, VH is differentiated by a deeper component that is often larger in size and has a more protracted clinical course.

Similar to IH, immunohistochemical studies have shown that VH expresses Wilms tumor 1 and glucose transporter 1 but is negative for D2-40.4 These findings suggest that VH is a vascular tumor rather than a vascular malformation, as was previously reported.6 Additional research has shown that the immunohistochemical staining profile of VH is nearly identical to IH, which has led to postulation that VH may be of placental mesodermal origin, as has been hypothesized for IH.5

Due to its deep infiltration and tendency for recurrence, VH is most effectively treated with wide local excision.3,6-8 Preoperative planning with magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated. Although laser monotherapy and other local destructive therapies have been largely unsuccessful, postsurgical laser therapy with CO2 lasers as well as dual pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser have shown promise in preventing recurrence.3

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

- Tennant LB, Mulliken JB, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Verrucous hemangioma revisited. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:208-215.

- Koc M, Kavala M, Kocatür E, et al. An unusual vascular tumor: verrucous hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:7.

- Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919; discussion 920.

- Trindade F, Torrelo A, Requena L, et al. An immunohistochemical study of verrucous hemangiomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:472-476.

- Laing EL, Brasch HD, Steel R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma expresses primitive markers. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:391-396.

- Mankani MH, Dufresne CR. Verrucous malformations: their presentation and management. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:31-36.

- Clairwood MQ, Bruckner AL, Dadras SS. Verrucous hemangioma: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:740-746.

- Segura Palacios JM, Boixeda P, Rocha J, et al. Laser treatment for verrucous hemangioma. Laser Med Sci. 2012;27:681-684.

A 31-year-old man presented with a large friable and warty plaque on the left heel. He recalled that the lesion had been present since birth as a flat red birthmark that grew proportionally with him. Throughout his adolescence its surface became increasingly rough and bumpy. The patient described receiving laser treatment twice in his early 20s without notable improvement. He wanted the lesion removed because it was easily traumatized, resulting in bleeding, pain, and infection. The patient reported being otherwise healthy.

Willingness to Take Weight Loss Medication Among Obese Primary Care Patients

From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Abstracts

- Objective: To identify patient factors associated with willingness to take daily weight loss medication and weight loss expectations using these medications.

- Methods: A random sample of 331 primary care patients aged 18–65 years with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were recruited from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, MA. We conducted telephone interviews and chart reviews to assess patients’ willingness to take a weight loss medication and their expectations for weight loss. We used sequential logistic regression models to identify demographic, clinical, and quality of life (QOL) factors associated with this willingness.

- Results: Of 331 subjects, 69% were women, 35% were white, 35% were black, and 25% were Hispanic; 249 (75%) of patients were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if recommended by their doctor but required a median weight loss of 15% to 24%; only 17% of patients were willing to take a medication for ≤ 10% weight loss. Men were significantly more willing than women (1.2 [95% CI 1.0–1.4]). Diabetes was the only comorbidity associated with willingness to consider pharmacotherapy (1.2 [1.0–1.3]) but only modestly improved model performance (C-statistic increased from 0.59 to 0.60). In contrast, lower QOL, especially low self-esteem and sex life, were stronger correlates (C-statistic 0.72).

- Conclusion: A majority of obese primary care patients were willing to take a daily weight loss pill; however, most required more than 10% weight loss to consider pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Poor QOL, especially low self-esteem and poor sex life, were stronger correlates than having diabetes.

Key words: obesity; primary care; weight loss medication.

In the United States, obesity continues to be unrelentingly prevalent, affecting more than one-third of adults (34.9%) [1]. This statistic has ominous implications when considering that obesity is a risk factor for numerous chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and some types of cancers [2]. Moreover, it is associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Promisingly, an initial 5% to 10% weight loss over 6 months has been associated with improvement in LDL, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, hemoglobin A1C, diabetes risk, blood pressure, and medication use [2]. Therefore, although patients may not be able to achieve their ideal body weight or normal BMI, modest weight loss can still have beneficial health effects.

Weight loss medications are effective adjunctive therapies in helping patients lose up to 10% of their body weight on average when combined with diet and exercise [3–5]. There are currently 5 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use for weight loss: orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine-topiramate, bupropion-naltrexone, and liraglutide. Despite their proven efficacy, there are barriers to initiating a long-term weight loss medication. Insurance reimbursement is limited for these medications, thus resulting in high out-of-pocket cost for patients that they may be unable or unwilling to pay [6]. There may also be safety concerns given that several weight loss medications, including fenfluramine, sibutramine, and rimonabant, have been withdrawn from the market because of adverse effects [7]. Thus, in deciding whether to initiate a pharmacologic weight loss regimen, patients must believe that the weight loss benefits will exceed the potential risks.

Little is known, however, about patients’ willingness to take weight loss medications or the minimum weight loss they expect to lose to make pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Only a few studies have investigated patient willingness to adopt pharmacotherapy as part of a weight loss regimen, and only one investigated obese patients in the United States [8]. In this context, we surveyed a sociodemographically diverse group of primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity to examine patient characteristics associated with willingness to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy. We also aimed to evaluate how much weight patients expected to lose in order to make taking a daily medication worth the effort. Characterizing patients seen in primary care who are willing to adopt pharmacotherapy to lose weight may guide weight loss counseling in the primary care setting. Furthermore, determining whether patients have realistic weight loss expectations can help clinicians better counsel their patients on weight loss goals.

Methods

Study Sample

We recruited 337 subjects from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, Massachusetts: a large hospital-based academic practice, a community practice in a working-class suburb, a community practice in an affluent suburb, and a health center serving a predominantly socially disadvantaged population. The primary goal of the parent study was to understand the preferences of patients for weight loss treatment, especially bariatric surgery. Therefore, to be included, patients needed to have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 at the time of recruitment, been seen in clinic within the past year, be aged 18–65 years, and be English or Spanish speaking. By design, African-American and Hispanic patients were oversampled from an electronic list of potentially eligible patient groups so that we could examine for racial differences in treatment preferences. Study details have been previously described [9].

Data Collection and Measures

Trained interviewers conducted a 45- to 60-minute telephone interview with each participant in either English or Spanish. To assess willingness to use a daily weight loss medication, subjects were asked, “If your doctor recommended it, would you be willing to take a pill or medication every day in order to lose weight?” Those who answered affirmatively were then asked the minimum amount of weight they would have to lose to make taking a pill everyday worthwhile.

Subjects were also asked about demographic information (age, race, education, marital status) and comorbid health conditions commonly associated with obesity (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, GERD, depression, anxiety, back pain, and cardiovascular problems). We assessed quality of life (QOL) using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite), a 31-item instrument designed specifically to assess the impact of obesity on QOL capturing 5 domains (physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, and work). Subjects were asked to rate a series of statements beginning with “Because of my weight…” as “always true,” “usually true,” “sometimes true,” “rarely true,” or “never true.” Global and domain scores ranged from 0 to 100; higher scores reflected better QOL [10].

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the proportion of subjects willing to use a daily weight loss medication and the weight loss required for patients to be willing to consider pharmacotherapy. We used a stepwise logistic model to examine demographic, QOL, and clinical factors associated with the willingness to take a weight loss medication as the outcome, with an entry criteria of P value of 0.1 and an exit criteria of 0.05. Log-Poisson distribution using the sandwich estimator was used to obtain relative risks for each significant variable. Adjusted models included age, BMI, sex, and race and any significant comorbidities. We added overall QOL score and individual QOL scores in subsequent models to examine the relative influence of overall vs. domain-specific QOL. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We considered the change in model C-statistic when specific variables were added to the model to determine the importance of these factors in contributing to patients’ willingness to consider pharmacotherapy; larger changes in model C-statistic signifies a greater contribution.

Results

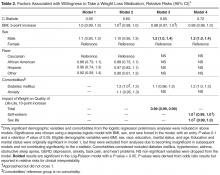

Table 2 displays sequentially adjusted models examining various demographic, clinical, and QOL factors associated with willingness to take a weight loss medication.

Discussion

In our study, we found that a large proportion (75%) of primary care patients with at least moderate obesity were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if their doctor recommended it. After full adjustment, men, those with lower quality of life (QOL), and patients with diabetes were more likely to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy than their counterparts. Moreover, QOL appeared more important than comorbid diagnoses in contributing to whether patients would consider taking a weight loss medication. Most patients expected to lose more than 10% of their weight to make taking a daily medication worthwhile.

Few studies have examined patients’ willingness to take a medication to lose weight. Tan et al [11] found that only about half of their surveyed outpatients were likely to take a medication to lose weight; however, approximately a quarter of the patients in that study were of normal BMI. In contrast, our study interviewed patients with at least a BMI of 35 kg/m2 and the majority of these patients reported a willingness to take a weight loss medication. Nevertheless, patients appear to have unrealistic expectations of the weight loss potential of pharmacotherapy. Only a minority of patients in our study would be willing to take a weight loss medication if the weight loss was no more than 10%, a level that is more consistent with the outcomes achievable in most clinical trials of weight loss medications [12]. Prior studies have also shown that patients often have unrealistic weight loss expectations and are unable to achieve their ideal body weight using diet, exercise, or pharmacotherapy [13,14]. Doyle et al found that percentage of weight loss was the most important treatment attribute when considering weight loss pharmacotherapy when compared to cost, health improvements, side effects, diet and exercise requirements, and method of medication administration [8]. Thus it is important to educate patients on realistic goal setting and the benefits of modest weight loss when considering pharmacotherapy. The weight loss preferences expressed in our study may also influence the weight loss outcomes targets pursued in pharmaceutical development. Interestingly, after full adjustment, BMI did not correlate with willingness to take a weight loss medication. Given that all patients in our study had a BMI of ≥ 35 kg/m2, this may imply that variations beyond this BMI threshold did not significantly affect a patient’s willingness to use pharmacotherapy. In contrast, weight-related QOL was an important correlate.

Men were slightly more likely than women to be willing to take a weight loss medication, which is interesting since men have been shown to be less likely to participate in behavioral weight loss programs and diets [15]. One reason may be that many weight loss programs are delivered in group settings which may deter men from participating. Whether this hypothetical willingness to undergo pharmacotherapy would translate to actual use is unclear, especially since there are barriers to pharmacotherapy including out-of-pocket costs. In a prior study in the United Kingdom, women were more likely to have reported prior weight loss medication use than men [16].

Our study did not find differences in willingness to pursue weight loss medication by race or educational attainment. This is consistent with our prior work demonstrating that racial and ethnic minorities were no less likely to consider bariatric surgery if the treatment were recommended by their doctor [9]. However, our other work did suggest that clinicians may be less likely to recommend bariatric surgery to their medically eligible minority patients as compared to their Caucasian patients. Whether this may be the case for pharmacotherapy is unclear since this was not explicitly queried in our current study [9].

Our study also found that patients with diabetes but not other comorbidities were more likely to consider weight loss medication after adjusting for QOL. This may reflect a stronger link between diabetes and obesity perceived by patients. Our result is consistent with our earlier data showing that diabetes but not other comorbid conditions was associated with a higher likelihood of considering weight loss surgery [9]. Nevertheless, having diabetes contributed only modestly to the variation in patient preferences regarding pharmacotherapy as reflected by the trivial change in model C-statistic when diabetes status was added to the model.

In contrast, lower QOL scores, especially in the domains of self-esteem and sex life, were associated with increased willingness to take a weight loss medication and appeared to be a stronger predictor than individual comorbidities. This is consistent with other studies showing that patients seeking treatment for obesity tend to have lower health-related QOL [9,17]. Our findings are also consistent with our previous research demonstrating that impairments in specific QOL domains are often more important to patients and stronger drivers of diminished well-being than measures of overall QOL [18]. Hence, given their importance to patients, clinicians need to consider QOL benefits when counseling patients about the risks and benefits of various obesity treatments.

This study is the first to our knowledge to systematically characterize demographic factors associated with the likelihood of primary care patients with obesity considering weight loss pharmacotherapy. This information may aid outpatient weight loss counseling by increasing awareness of gender and patient specific preferences. The fact that many patients with obesity appear to be interested in pursuing weight loss medication may also support public health initiatives in providing equitable access to weight loss pharmacotherapy. As our study characterizes patients who are willing to pursue weight loss medications, future studies may include retrospective analyses on actual use of weight loss medications among various demographic groups. Further investigation on specific reasons why patients choose whether or not to use weight loss medication may also be helpful.

This study has important limitations. The sample size was modest and potentially underpowered to detect small differences across different subgroups. Our sample was also limited to practices in Boston, which limits generalizability; although, by design, we oversampled racial and ethnic subjects to ensure diverse representation. Finally, our study examined patients’ hypothetical willingness to take weight loss medications rather than their actual adherence to treatment if offered.

Conclusion

In this sample of obese primary care patients, we found that the majority of patients were willing to take a daily medication to lose weight; however, patients had expectations for weight loss that far exceeded the level achievable by patients in pharmaceutical trials of these agents. Men and patients with diabetes were more likely to be willing to pursue weight loss medication; however, lower weight-related QOL, especially low self-esteem and impaired sexual function, appeared to be a stronger correlate of willingness to consider pharmacotherapy than comorbid diagnoses.

Corresponding author: Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215, [email protected].

Funding/support: This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK073302, PI Wee). Dr. Wee is also supported by an NIH midcareer mentorship award (K24DK087932). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial disclosures: None reported.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013;(131):1–8.

2. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023.

3. Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, et al. Orlistat in the long-term treatment of obesity in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:160–7.

4. Kakkar AK, Dahiya N. Drug treatment of obesity: current status and future prospects. Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:89–94.

5. Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, et al. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:330–42.

6. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA. Obesity. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2:357–77.

7. Cheung BM, Cheung TT, Samaranayake NR. Safety of antiobesity drugs. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2013;4:171–81.

8. Doyle S, Lloyd A, Birt J, et al. Willingness to pay for obesity pharmacotherapy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:2019–26.

9. Wee CC HK, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Colten ME, et al. Sex, race, and consideration of bariatric surgery among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:68–75.

10. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:102–11.

11. Tan DZN, Dennis SM, Vagholkar S. Weight management in general practice: what do patients want? Med J Aust 2006;185:73–5.

12. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:74–86.

13. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997;65:79–85.

14. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, et al. The role of patients’ expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1739–45.

15. Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, et al. Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess 2014;18:1–424.

16. Thompson RL, Thomas DE. A cross-sectional survey of the opinions on weight loss treatments of adult obese patients attending a dietetic clinic. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:164–70.

17. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res 2002;10:748–56.

18. Wee C, Davis R, Chiodi S, et al. Sex, race, and the adverse effects of social stigma vs. other quality of life factors among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:229–35.

From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Abstracts

- Objective: To identify patient factors associated with willingness to take daily weight loss medication and weight loss expectations using these medications.

- Methods: A random sample of 331 primary care patients aged 18–65 years with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were recruited from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, MA. We conducted telephone interviews and chart reviews to assess patients’ willingness to take a weight loss medication and their expectations for weight loss. We used sequential logistic regression models to identify demographic, clinical, and quality of life (QOL) factors associated with this willingness.

- Results: Of 331 subjects, 69% were women, 35% were white, 35% were black, and 25% were Hispanic; 249 (75%) of patients were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if recommended by their doctor but required a median weight loss of 15% to 24%; only 17% of patients were willing to take a medication for ≤ 10% weight loss. Men were significantly more willing than women (1.2 [95% CI 1.0–1.4]). Diabetes was the only comorbidity associated with willingness to consider pharmacotherapy (1.2 [1.0–1.3]) but only modestly improved model performance (C-statistic increased from 0.59 to 0.60). In contrast, lower QOL, especially low self-esteem and sex life, were stronger correlates (C-statistic 0.72).

- Conclusion: A majority of obese primary care patients were willing to take a daily weight loss pill; however, most required more than 10% weight loss to consider pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Poor QOL, especially low self-esteem and poor sex life, were stronger correlates than having diabetes.

Key words: obesity; primary care; weight loss medication.

In the United States, obesity continues to be unrelentingly prevalent, affecting more than one-third of adults (34.9%) [1]. This statistic has ominous implications when considering that obesity is a risk factor for numerous chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and some types of cancers [2]. Moreover, it is associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Promisingly, an initial 5% to 10% weight loss over 6 months has been associated with improvement in LDL, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, hemoglobin A1C, diabetes risk, blood pressure, and medication use [2]. Therefore, although patients may not be able to achieve their ideal body weight or normal BMI, modest weight loss can still have beneficial health effects.

Weight loss medications are effective adjunctive therapies in helping patients lose up to 10% of their body weight on average when combined with diet and exercise [3–5]. There are currently 5 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use for weight loss: orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine-topiramate, bupropion-naltrexone, and liraglutide. Despite their proven efficacy, there are barriers to initiating a long-term weight loss medication. Insurance reimbursement is limited for these medications, thus resulting in high out-of-pocket cost for patients that they may be unable or unwilling to pay [6]. There may also be safety concerns given that several weight loss medications, including fenfluramine, sibutramine, and rimonabant, have been withdrawn from the market because of adverse effects [7]. Thus, in deciding whether to initiate a pharmacologic weight loss regimen, patients must believe that the weight loss benefits will exceed the potential risks.

Little is known, however, about patients’ willingness to take weight loss medications or the minimum weight loss they expect to lose to make pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Only a few studies have investigated patient willingness to adopt pharmacotherapy as part of a weight loss regimen, and only one investigated obese patients in the United States [8]. In this context, we surveyed a sociodemographically diverse group of primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity to examine patient characteristics associated with willingness to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy. We also aimed to evaluate how much weight patients expected to lose in order to make taking a daily medication worth the effort. Characterizing patients seen in primary care who are willing to adopt pharmacotherapy to lose weight may guide weight loss counseling in the primary care setting. Furthermore, determining whether patients have realistic weight loss expectations can help clinicians better counsel their patients on weight loss goals.

Methods

Study Sample

We recruited 337 subjects from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, Massachusetts: a large hospital-based academic practice, a community practice in a working-class suburb, a community practice in an affluent suburb, and a health center serving a predominantly socially disadvantaged population. The primary goal of the parent study was to understand the preferences of patients for weight loss treatment, especially bariatric surgery. Therefore, to be included, patients needed to have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 at the time of recruitment, been seen in clinic within the past year, be aged 18–65 years, and be English or Spanish speaking. By design, African-American and Hispanic patients were oversampled from an electronic list of potentially eligible patient groups so that we could examine for racial differences in treatment preferences. Study details have been previously described [9].

Data Collection and Measures

Trained interviewers conducted a 45- to 60-minute telephone interview with each participant in either English or Spanish. To assess willingness to use a daily weight loss medication, subjects were asked, “If your doctor recommended it, would you be willing to take a pill or medication every day in order to lose weight?” Those who answered affirmatively were then asked the minimum amount of weight they would have to lose to make taking a pill everyday worthwhile.

Subjects were also asked about demographic information (age, race, education, marital status) and comorbid health conditions commonly associated with obesity (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, GERD, depression, anxiety, back pain, and cardiovascular problems). We assessed quality of life (QOL) using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite), a 31-item instrument designed specifically to assess the impact of obesity on QOL capturing 5 domains (physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, and work). Subjects were asked to rate a series of statements beginning with “Because of my weight…” as “always true,” “usually true,” “sometimes true,” “rarely true,” or “never true.” Global and domain scores ranged from 0 to 100; higher scores reflected better QOL [10].

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the proportion of subjects willing to use a daily weight loss medication and the weight loss required for patients to be willing to consider pharmacotherapy. We used a stepwise logistic model to examine demographic, QOL, and clinical factors associated with the willingness to take a weight loss medication as the outcome, with an entry criteria of P value of 0.1 and an exit criteria of 0.05. Log-Poisson distribution using the sandwich estimator was used to obtain relative risks for each significant variable. Adjusted models included age, BMI, sex, and race and any significant comorbidities. We added overall QOL score and individual QOL scores in subsequent models to examine the relative influence of overall vs. domain-specific QOL. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We considered the change in model C-statistic when specific variables were added to the model to determine the importance of these factors in contributing to patients’ willingness to consider pharmacotherapy; larger changes in model C-statistic signifies a greater contribution.

Results

Table 2 displays sequentially adjusted models examining various demographic, clinical, and QOL factors associated with willingness to take a weight loss medication.

Discussion

In our study, we found that a large proportion (75%) of primary care patients with at least moderate obesity were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if their doctor recommended it. After full adjustment, men, those with lower quality of life (QOL), and patients with diabetes were more likely to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy than their counterparts. Moreover, QOL appeared more important than comorbid diagnoses in contributing to whether patients would consider taking a weight loss medication. Most patients expected to lose more than 10% of their weight to make taking a daily medication worthwhile.

Few studies have examined patients’ willingness to take a medication to lose weight. Tan et al [11] found that only about half of their surveyed outpatients were likely to take a medication to lose weight; however, approximately a quarter of the patients in that study were of normal BMI. In contrast, our study interviewed patients with at least a BMI of 35 kg/m2 and the majority of these patients reported a willingness to take a weight loss medication. Nevertheless, patients appear to have unrealistic expectations of the weight loss potential of pharmacotherapy. Only a minority of patients in our study would be willing to take a weight loss medication if the weight loss was no more than 10%, a level that is more consistent with the outcomes achievable in most clinical trials of weight loss medications [12]. Prior studies have also shown that patients often have unrealistic weight loss expectations and are unable to achieve their ideal body weight using diet, exercise, or pharmacotherapy [13,14]. Doyle et al found that percentage of weight loss was the most important treatment attribute when considering weight loss pharmacotherapy when compared to cost, health improvements, side effects, diet and exercise requirements, and method of medication administration [8]. Thus it is important to educate patients on realistic goal setting and the benefits of modest weight loss when considering pharmacotherapy. The weight loss preferences expressed in our study may also influence the weight loss outcomes targets pursued in pharmaceutical development. Interestingly, after full adjustment, BMI did not correlate with willingness to take a weight loss medication. Given that all patients in our study had a BMI of ≥ 35 kg/m2, this may imply that variations beyond this BMI threshold did not significantly affect a patient’s willingness to use pharmacotherapy. In contrast, weight-related QOL was an important correlate.

Men were slightly more likely than women to be willing to take a weight loss medication, which is interesting since men have been shown to be less likely to participate in behavioral weight loss programs and diets [15]. One reason may be that many weight loss programs are delivered in group settings which may deter men from participating. Whether this hypothetical willingness to undergo pharmacotherapy would translate to actual use is unclear, especially since there are barriers to pharmacotherapy including out-of-pocket costs. In a prior study in the United Kingdom, women were more likely to have reported prior weight loss medication use than men [16].

Our study did not find differences in willingness to pursue weight loss medication by race or educational attainment. This is consistent with our prior work demonstrating that racial and ethnic minorities were no less likely to consider bariatric surgery if the treatment were recommended by their doctor [9]. However, our other work did suggest that clinicians may be less likely to recommend bariatric surgery to their medically eligible minority patients as compared to their Caucasian patients. Whether this may be the case for pharmacotherapy is unclear since this was not explicitly queried in our current study [9].

Our study also found that patients with diabetes but not other comorbidities were more likely to consider weight loss medication after adjusting for QOL. This may reflect a stronger link between diabetes and obesity perceived by patients. Our result is consistent with our earlier data showing that diabetes but not other comorbid conditions was associated with a higher likelihood of considering weight loss surgery [9]. Nevertheless, having diabetes contributed only modestly to the variation in patient preferences regarding pharmacotherapy as reflected by the trivial change in model C-statistic when diabetes status was added to the model.

In contrast, lower QOL scores, especially in the domains of self-esteem and sex life, were associated with increased willingness to take a weight loss medication and appeared to be a stronger predictor than individual comorbidities. This is consistent with other studies showing that patients seeking treatment for obesity tend to have lower health-related QOL [9,17]. Our findings are also consistent with our previous research demonstrating that impairments in specific QOL domains are often more important to patients and stronger drivers of diminished well-being than measures of overall QOL [18]. Hence, given their importance to patients, clinicians need to consider QOL benefits when counseling patients about the risks and benefits of various obesity treatments.

This study is the first to our knowledge to systematically characterize demographic factors associated with the likelihood of primary care patients with obesity considering weight loss pharmacotherapy. This information may aid outpatient weight loss counseling by increasing awareness of gender and patient specific preferences. The fact that many patients with obesity appear to be interested in pursuing weight loss medication may also support public health initiatives in providing equitable access to weight loss pharmacotherapy. As our study characterizes patients who are willing to pursue weight loss medications, future studies may include retrospective analyses on actual use of weight loss medications among various demographic groups. Further investigation on specific reasons why patients choose whether or not to use weight loss medication may also be helpful.

This study has important limitations. The sample size was modest and potentially underpowered to detect small differences across different subgroups. Our sample was also limited to practices in Boston, which limits generalizability; although, by design, we oversampled racial and ethnic subjects to ensure diverse representation. Finally, our study examined patients’ hypothetical willingness to take weight loss medications rather than their actual adherence to treatment if offered.

Conclusion

In this sample of obese primary care patients, we found that the majority of patients were willing to take a daily medication to lose weight; however, patients had expectations for weight loss that far exceeded the level achievable by patients in pharmaceutical trials of these agents. Men and patients with diabetes were more likely to be willing to pursue weight loss medication; however, lower weight-related QOL, especially low self-esteem and impaired sexual function, appeared to be a stronger correlate of willingness to consider pharmacotherapy than comorbid diagnoses.

Corresponding author: Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215, [email protected].

Funding/support: This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK073302, PI Wee). Dr. Wee is also supported by an NIH midcareer mentorship award (K24DK087932). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial disclosures: None reported.

From Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Abstracts

- Objective: To identify patient factors associated with willingness to take daily weight loss medication and weight loss expectations using these medications.

- Methods: A random sample of 331 primary care patients aged 18–65 years with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were recruited from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, MA. We conducted telephone interviews and chart reviews to assess patients’ willingness to take a weight loss medication and their expectations for weight loss. We used sequential logistic regression models to identify demographic, clinical, and quality of life (QOL) factors associated with this willingness.

- Results: Of 331 subjects, 69% were women, 35% were white, 35% were black, and 25% were Hispanic; 249 (75%) of patients were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if recommended by their doctor but required a median weight loss of 15% to 24%; only 17% of patients were willing to take a medication for ≤ 10% weight loss. Men were significantly more willing than women (1.2 [95% CI 1.0–1.4]). Diabetes was the only comorbidity associated with willingness to consider pharmacotherapy (1.2 [1.0–1.3]) but only modestly improved model performance (C-statistic increased from 0.59 to 0.60). In contrast, lower QOL, especially low self-esteem and sex life, were stronger correlates (C-statistic 0.72).

- Conclusion: A majority of obese primary care patients were willing to take a daily weight loss pill; however, most required more than 10% weight loss to consider pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Poor QOL, especially low self-esteem and poor sex life, were stronger correlates than having diabetes.

Key words: obesity; primary care; weight loss medication.

In the United States, obesity continues to be unrelentingly prevalent, affecting more than one-third of adults (34.9%) [1]. This statistic has ominous implications when considering that obesity is a risk factor for numerous chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, osteoarthritis, and some types of cancers [2]. Moreover, it is associated with increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. Promisingly, an initial 5% to 10% weight loss over 6 months has been associated with improvement in LDL, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, hemoglobin A1C, diabetes risk, blood pressure, and medication use [2]. Therefore, although patients may not be able to achieve their ideal body weight or normal BMI, modest weight loss can still have beneficial health effects.

Weight loss medications are effective adjunctive therapies in helping patients lose up to 10% of their body weight on average when combined with diet and exercise [3–5]. There are currently 5 medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use for weight loss: orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine-topiramate, bupropion-naltrexone, and liraglutide. Despite their proven efficacy, there are barriers to initiating a long-term weight loss medication. Insurance reimbursement is limited for these medications, thus resulting in high out-of-pocket cost for patients that they may be unable or unwilling to pay [6]. There may also be safety concerns given that several weight loss medications, including fenfluramine, sibutramine, and rimonabant, have been withdrawn from the market because of adverse effects [7]. Thus, in deciding whether to initiate a pharmacologic weight loss regimen, patients must believe that the weight loss benefits will exceed the potential risks.

Little is known, however, about patients’ willingness to take weight loss medications or the minimum weight loss they expect to lose to make pharmacotherapy worthwhile. Only a few studies have investigated patient willingness to adopt pharmacotherapy as part of a weight loss regimen, and only one investigated obese patients in the United States [8]. In this context, we surveyed a sociodemographically diverse group of primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity to examine patient characteristics associated with willingness to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy. We also aimed to evaluate how much weight patients expected to lose in order to make taking a daily medication worth the effort. Characterizing patients seen in primary care who are willing to adopt pharmacotherapy to lose weight may guide weight loss counseling in the primary care setting. Furthermore, determining whether patients have realistic weight loss expectations can help clinicians better counsel their patients on weight loss goals.

Methods

Study Sample

We recruited 337 subjects from 4 diverse primary care practices in Boston, Massachusetts: a large hospital-based academic practice, a community practice in a working-class suburb, a community practice in an affluent suburb, and a health center serving a predominantly socially disadvantaged population. The primary goal of the parent study was to understand the preferences of patients for weight loss treatment, especially bariatric surgery. Therefore, to be included, patients needed to have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 at the time of recruitment, been seen in clinic within the past year, be aged 18–65 years, and be English or Spanish speaking. By design, African-American and Hispanic patients were oversampled from an electronic list of potentially eligible patient groups so that we could examine for racial differences in treatment preferences. Study details have been previously described [9].

Data Collection and Measures

Trained interviewers conducted a 45- to 60-minute telephone interview with each participant in either English or Spanish. To assess willingness to use a daily weight loss medication, subjects were asked, “If your doctor recommended it, would you be willing to take a pill or medication every day in order to lose weight?” Those who answered affirmatively were then asked the minimum amount of weight they would have to lose to make taking a pill everyday worthwhile.

Subjects were also asked about demographic information (age, race, education, marital status) and comorbid health conditions commonly associated with obesity (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, GERD, depression, anxiety, back pain, and cardiovascular problems). We assessed quality of life (QOL) using the Impact of Weight on Quality of Life-Lite (IWQOL-Lite), a 31-item instrument designed specifically to assess the impact of obesity on QOL capturing 5 domains (physical function, self-esteem, sexual life, public distress, and work). Subjects were asked to rate a series of statements beginning with “Because of my weight…” as “always true,” “usually true,” “sometimes true,” “rarely true,” or “never true.” Global and domain scores ranged from 0 to 100; higher scores reflected better QOL [10].

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the proportion of subjects willing to use a daily weight loss medication and the weight loss required for patients to be willing to consider pharmacotherapy. We used a stepwise logistic model to examine demographic, QOL, and clinical factors associated with the willingness to take a weight loss medication as the outcome, with an entry criteria of P value of 0.1 and an exit criteria of 0.05. Log-Poisson distribution using the sandwich estimator was used to obtain relative risks for each significant variable. Adjusted models included age, BMI, sex, and race and any significant comorbidities. We added overall QOL score and individual QOL scores in subsequent models to examine the relative influence of overall vs. domain-specific QOL. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We considered the change in model C-statistic when specific variables were added to the model to determine the importance of these factors in contributing to patients’ willingness to consider pharmacotherapy; larger changes in model C-statistic signifies a greater contribution.

Results

Table 2 displays sequentially adjusted models examining various demographic, clinical, and QOL factors associated with willingness to take a weight loss medication.

Discussion

In our study, we found that a large proportion (75%) of primary care patients with at least moderate obesity were willing to take a daily weight loss medication if their doctor recommended it. After full adjustment, men, those with lower quality of life (QOL), and patients with diabetes were more likely to pursue weight loss pharmacotherapy than their counterparts. Moreover, QOL appeared more important than comorbid diagnoses in contributing to whether patients would consider taking a weight loss medication. Most patients expected to lose more than 10% of their weight to make taking a daily medication worthwhile.

Few studies have examined patients’ willingness to take a medication to lose weight. Tan et al [11] found that only about half of their surveyed outpatients were likely to take a medication to lose weight; however, approximately a quarter of the patients in that study were of normal BMI. In contrast, our study interviewed patients with at least a BMI of 35 kg/m2 and the majority of these patients reported a willingness to take a weight loss medication. Nevertheless, patients appear to have unrealistic expectations of the weight loss potential of pharmacotherapy. Only a minority of patients in our study would be willing to take a weight loss medication if the weight loss was no more than 10%, a level that is more consistent with the outcomes achievable in most clinical trials of weight loss medications [12]. Prior studies have also shown that patients often have unrealistic weight loss expectations and are unable to achieve their ideal body weight using diet, exercise, or pharmacotherapy [13,14]. Doyle et al found that percentage of weight loss was the most important treatment attribute when considering weight loss pharmacotherapy when compared to cost, health improvements, side effects, diet and exercise requirements, and method of medication administration [8]. Thus it is important to educate patients on realistic goal setting and the benefits of modest weight loss when considering pharmacotherapy. The weight loss preferences expressed in our study may also influence the weight loss outcomes targets pursued in pharmaceutical development. Interestingly, after full adjustment, BMI did not correlate with willingness to take a weight loss medication. Given that all patients in our study had a BMI of ≥ 35 kg/m2, this may imply that variations beyond this BMI threshold did not significantly affect a patient’s willingness to use pharmacotherapy. In contrast, weight-related QOL was an important correlate.

Men were slightly more likely than women to be willing to take a weight loss medication, which is interesting since men have been shown to be less likely to participate in behavioral weight loss programs and diets [15]. One reason may be that many weight loss programs are delivered in group settings which may deter men from participating. Whether this hypothetical willingness to undergo pharmacotherapy would translate to actual use is unclear, especially since there are barriers to pharmacotherapy including out-of-pocket costs. In a prior study in the United Kingdom, women were more likely to have reported prior weight loss medication use than men [16].

Our study did not find differences in willingness to pursue weight loss medication by race or educational attainment. This is consistent with our prior work demonstrating that racial and ethnic minorities were no less likely to consider bariatric surgery if the treatment were recommended by their doctor [9]. However, our other work did suggest that clinicians may be less likely to recommend bariatric surgery to their medically eligible minority patients as compared to their Caucasian patients. Whether this may be the case for pharmacotherapy is unclear since this was not explicitly queried in our current study [9].

Our study also found that patients with diabetes but not other comorbidities were more likely to consider weight loss medication after adjusting for QOL. This may reflect a stronger link between diabetes and obesity perceived by patients. Our result is consistent with our earlier data showing that diabetes but not other comorbid conditions was associated with a higher likelihood of considering weight loss surgery [9]. Nevertheless, having diabetes contributed only modestly to the variation in patient preferences regarding pharmacotherapy as reflected by the trivial change in model C-statistic when diabetes status was added to the model.

In contrast, lower QOL scores, especially in the domains of self-esteem and sex life, were associated with increased willingness to take a weight loss medication and appeared to be a stronger predictor than individual comorbidities. This is consistent with other studies showing that patients seeking treatment for obesity tend to have lower health-related QOL [9,17]. Our findings are also consistent with our previous research demonstrating that impairments in specific QOL domains are often more important to patients and stronger drivers of diminished well-being than measures of overall QOL [18]. Hence, given their importance to patients, clinicians need to consider QOL benefits when counseling patients about the risks and benefits of various obesity treatments.

This study is the first to our knowledge to systematically characterize demographic factors associated with the likelihood of primary care patients with obesity considering weight loss pharmacotherapy. This information may aid outpatient weight loss counseling by increasing awareness of gender and patient specific preferences. The fact that many patients with obesity appear to be interested in pursuing weight loss medication may also support public health initiatives in providing equitable access to weight loss pharmacotherapy. As our study characterizes patients who are willing to pursue weight loss medications, future studies may include retrospective analyses on actual use of weight loss medications among various demographic groups. Further investigation on specific reasons why patients choose whether or not to use weight loss medication may also be helpful.

This study has important limitations. The sample size was modest and potentially underpowered to detect small differences across different subgroups. Our sample was also limited to practices in Boston, which limits generalizability; although, by design, we oversampled racial and ethnic subjects to ensure diverse representation. Finally, our study examined patients’ hypothetical willingness to take weight loss medications rather than their actual adherence to treatment if offered.

Conclusion

In this sample of obese primary care patients, we found that the majority of patients were willing to take a daily medication to lose weight; however, patients had expectations for weight loss that far exceeded the level achievable by patients in pharmaceutical trials of these agents. Men and patients with diabetes were more likely to be willing to pursue weight loss medication; however, lower weight-related QOL, especially low self-esteem and impaired sexual function, appeared to be a stronger correlate of willingness to consider pharmacotherapy than comorbid diagnoses.

Corresponding author: Christina C. Wee, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave., Boston, MA 02215, [email protected].

Funding/support: This study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK073302, PI Wee). Dr. Wee is also supported by an NIH midcareer mentorship award (K24DK087932). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Financial disclosures: None reported.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013;(131):1–8.

2. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023.

3. Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, et al. Orlistat in the long-term treatment of obesity in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:160–7.

4. Kakkar AK, Dahiya N. Drug treatment of obesity: current status and future prospects. Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:89–94.

5. Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, et al. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:330–42.

6. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA. Obesity. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2:357–77.

7. Cheung BM, Cheung TT, Samaranayake NR. Safety of antiobesity drugs. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2013;4:171–81.

8. Doyle S, Lloyd A, Birt J, et al. Willingness to pay for obesity pharmacotherapy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:2019–26.

9. Wee CC HK, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Colten ME, et al. Sex, race, and consideration of bariatric surgery among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:68–75.

10. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:102–11.

11. Tan DZN, Dennis SM, Vagholkar S. Weight management in general practice: what do patients want? Med J Aust 2006;185:73–5.

12. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:74–86.

13. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997;65:79–85.

14. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, et al. The role of patients’ expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1739–45.

15. Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, et al. Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess 2014;18:1–424.

16. Thompson RL, Thomas DE. A cross-sectional survey of the opinions on weight loss treatments of adult obese patients attending a dietetic clinic. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:164–70.

17. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res 2002;10:748–56.

18. Wee C, Davis R, Chiodi S, et al. Sex, race, and the adverse effects of social stigma vs. other quality of life factors among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:229–35.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013;(131):1–8.

2. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(25 Pt B):2985–3023.

3. Hauptman J, Lucas C, Boldrin MN, et al. Orlistat in the long-term treatment of obesity in primary care settings. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:160–7.

4. Kakkar AK, Dahiya N. Drug treatment of obesity: current status and future prospects. Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:89–94.

5. Allison DB, Gadde KM, Garvey WT, et al. Controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in severely obese adults: a randomized controlled trial (EQUIP). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20:330–42.

6. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA. Obesity. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2006;2:357–77.

7. Cheung BM, Cheung TT, Samaranayake NR. Safety of antiobesity drugs. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2013;4:171–81.

8. Doyle S, Lloyd A, Birt J, et al. Willingness to pay for obesity pharmacotherapy. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:2019–26.

9. Wee CC HK, Bolcic-Jankovic D, Colten ME, et al. Sex, race, and consideration of bariatric surgery among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:68–75.

10. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:102–11.

11. Tan DZN, Dennis SM, Vagholkar S. Weight management in general practice: what do patients want? Med J Aust 2006;185:73–5.

12. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:74–86.

13. Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients’ expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997;65:79–85.

14. Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, et al. The role of patients’ expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1739–45.

15. Robertson C, Archibald D, Avenell A, et al. Systematic reviews of and integrated report on the quantitative, qualitative and economic evidence base for the management of obesity in men. Health Technol Assess 2014;18:1–424.

16. Thompson RL, Thomas DE. A cross-sectional survey of the opinions on weight loss treatments of adult obese patients attending a dietetic clinic. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000;24:164–70.

17. Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res 2002;10:748–56.

18. Wee C, Davis R, Chiodi S, et al. Sex, race, and the adverse effects of social stigma vs. other quality of life factors among primary care patients with moderate to severe obesity. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:229–35.

How to Treat Pediatric MS

VANCOUVER—Pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS) presents unique concerns, making appropriate treatment especially important, according to an overview presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society. Currently, disease-modifying therapies with FDA approval in adult MS have not been approved for the treatment of pediatric MS. In addition, brain growth and cognition are adversely affected in pediatric MS. Furthermore, children with MS tend to become disabled at a younger age, compared with adults.

Diagnosis and Initiation of Therapy

Neurologists should be prepared to engage with children and their families to ensure the most efficacious treatment. “Whenever you are having that conversation or you are considering starting the disease-modifying therapy, you need to balance the need to treat the disease with the idea that you are going to be starting a therapy for a lifetime,” said Dr. Lotze.

Disease-modifying therapies target the inflammatory aspects of pediatric-onset MS and should be initiated in children with a confirmed diagnosis, said Dr. Lotze. Children with clinically isolated syndrome who appear to be at high risk for MS and children with positive oligoclonal bands or elevated IgG index may also need to begin a disease-modifying therapy. Distinguishing between MS, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), and neuromyelitis optica (NMO) poses challenges, especially in children under age 10. Certain interferons can exacerbate NMO and may be harmful in children with ADEM or multiphasic ADEM.

Setting Goals

Neurologists are encouraged to counsel patients about the purpose and side effects of treatment, as well as to establish reasonable expectations for treatment. Additionally, children and families should be aware that another attack may occur during treatment and should be informed about what to do if it does.

No therapy is 100% efficacious in pediatric or adult MS, said Dr. Lotze. Research suggests that 50% of adults have no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) at two years of the disease. After seven years, however, 7% of these adults meet NEDA criteria. As a result, minimal disease progression (defined as less than one attack per year, fewer than three new lesions on a yearly MRI, and no progression in disability) may be a more attainable goal. “We would like to see a drug in a single individual or patient that is effective in achieving NEDA. If that is not possible … you might find that ultimately what you can go for is minimal disease progression,” said Dr. Lotze. He added that there appears to be no clear difference in terms of long-term outcome between children with MS who achieve NEDA and those who achieve minimal disease progression.

First-Line Therapies and Follow-Up Appointments

First-line agents for pediatric MS are the injectable drugs known as platform therapies. The International Pediatric MS Society Group (IPMSSG) recommends that all patients start first-line therapy (ie, interferon β or glatiramer acetate) soon after diagnosis.

Positive results from phase IV observational studies suggest that interferon β and glatiramer acetate are safe and efficacious treatments in pediatric MS. When studied in populations ranging in age from 12 to 17, these therapies decreased relapse rate, stabilized disability, and reduced accrual of new lesions. However, injectable treatments are associated with flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions. Neurologists should start pediatric patients on interferon β with 25% to 50% of full dosing and titrate to a full adult dosing over four to six weeks. When initiating glatiramer acetate, neurologists should start children with a full adult dosing, 20 mg subcutaneous daily or 40 mg subcutaneous three times per week.

Follow-up appointments should occur every three to six months to assess adherence and determine efficacy of treatment. Neurologists are advised to ask patients whether they are comfortable with taking shots. Patients with needle anxiety, a common problem in pediatric MS, may need assistance from a child psychologist or child life specialist. Asking patients how often the patient or family forgets to take the disease-modifying therapy is also necessary, said Dr. Lotze. In addition, the transition from pediatric to adult care should be addressed in follow-up discussions. Teens must understand that certain disease-modifying therapies are contraindicated for pregnant patients. They also should be aware of how alcohol and other drugs interact with treatment.

Treatment Failure

Research indicates that approximately 30% of patients with pediatric-onset MS will not respond to the first-line therapies, and numerous variables may explain why. Age and disease duration can influence treatment efficacy, as can the number of relapses and the level of disease activity before treatment initiation. Patients who are nonadherent because of side effects and who continue to struggle with needle anxiety may experience treatment failure. The IPMSSG defines treatment failure as adherence to treatment for at least six months with no reduction in relapse rate or in new MRI T2 or contrast-enhancing lesions, or with two or more relapses within a 12-month period.

Second-Line Therapies

Trials of several oral agents are currently under way. The IPMSSG, however, urges neurologists to use extreme caution when considering nonplatform therapies for pediatric patients.

Fingolimod is a second-line drug for pediatric MS that blocks the egress of lymphocytes from the lymph nodes. A small percentage of patients taking this oral agent may develop bradycardia. Monitoring is required for the first six hours of treatment to ensure that the patient has no side effects. Some adverse effects associated with the drug include: first dose bradycardia, macular edema, and herpetic infections.

Dimethyl fumarate is an Nrf2 antioxidant pathway modulator that is associated with adverse effects such as flushing and gastrointestinal upset, said Dr. Lotze. Low-dose aspirin may help with flushing, and a proton pump inhibitor can help to manage the gastrointestinal upset. This treatment requires patients to undergo monitoring for blood count and liver function, as does fingolimod.

Teriflunomide, a pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor, is a Pregnancy Category X drug because it increases the risk of birth defects. Rituximab, an anti-CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody, is gaining popularity for treating MS. Studies suggest that ocrelizumab may be well tolerated in pediatric MS. Natlizumamb, cladribine, and alemtuzumab are typically used to treat more aggressive forms of MS.

Neurologists rarely prescribe cyclophosphamide or mitoxantrone in pediatric MS. Cyclophosphamide has no formal FDA approval for adult MS or pediatric-onset MS and is associated with increased risks of bladder cancer, secondary leukemia, and infertility. Mitoxantrone is FDA-approved for adults with aggressive relapsing-remitting MS and secondary progressive MS. It is associated with increased cancer risk, however, and is highly cardiotoxic.

“After you have initiated a second-line agent, you need to continue to monitor aspects of disease control, including relapse rate, disability, MRI changes, and other adverse events. If you continue to see breakthrough disease, then you may need to consider … changing to another agent or moving to a more aggressive therapy such as rituximab or natalizumab,” said Dr. Lotze.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Chitnis T, Ghezzi A, Bajer-Korneck B, et al. Pediatric multiple sclerosis: Escalation and emerging treatments. Neurology. 2016;87(9 Suppl 2):S10 3-S109.

Jancic J, Nikolic B, Ivancevic N, et al. Multiple sclerosis in pediatrics: Current concepts and treatment options. Neurol Ther. 2016:5(2):131-1

VANCOUVER—Pediatric multiple sclerosis (MS) presents unique concerns, making appropriate treatment especially important, according to an overview presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society. Currently, disease-modifying therapies with FDA approval in adult MS have not been approved for the treatment of pediatric MS. In addition, brain growth and cognition are adversely affected in pediatric MS. Furthermore, children with MS tend to become disabled at a younger age, compared with adults.

Diagnosis and Initiation of Therapy

Neurologists should be prepared to engage with children and their families to ensure the most efficacious treatment. “Whenever you are having that conversation or you are considering starting the disease-modifying therapy, you need to balance the need to treat the disease with the idea that you are going to be starting a therapy for a lifetime,” said Dr. Lotze.

Disease-modifying therapies target the inflammatory aspects of pediatric-onset MS and should be initiated in children with a confirmed diagnosis, said Dr. Lotze. Children with clinically isolated syndrome who appear to be at high risk for MS and children with positive oligoclonal bands or elevated IgG index may also need to begin a disease-modifying therapy. Distinguishing between MS, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), and neuromyelitis optica (NMO) poses challenges, especially in children under age 10. Certain interferons can exacerbate NMO and may be harmful in children with ADEM or multiphasic ADEM.

Setting Goals

Neurologists are encouraged to counsel patients about the purpose and side effects of treatment, as well as to establish reasonable expectations for treatment. Additionally, children and families should be aware that another attack may occur during treatment and should be informed about what to do if it does.

No therapy is 100% efficacious in pediatric or adult MS, said Dr. Lotze. Research suggests that 50% of adults have no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) at two years of the disease. After seven years, however, 7% of these adults meet NEDA criteria. As a result, minimal disease progression (defined as less than one attack per year, fewer than three new lesions on a yearly MRI, and no progression in disability) may be a more attainable goal. “We would like to see a drug in a single individual or patient that is effective in achieving NEDA. If that is not possible … you might find that ultimately what you can go for is minimal disease progression,” said Dr. Lotze. He added that there appears to be no clear difference in terms of long-term outcome between children with MS who achieve NEDA and those who achieve minimal disease progression.

First-Line Therapies and Follow-Up Appointments

First-line agents for pediatric MS are the injectable drugs known as platform therapies. The International Pediatric MS Society Group (IPMSSG) recommends that all patients start first-line therapy (ie, interferon β or glatiramer acetate) soon after diagnosis.

Positive results from phase IV observational studies suggest that interferon β and glatiramer acetate are safe and efficacious treatments in pediatric MS. When studied in populations ranging in age from 12 to 17, these therapies decreased relapse rate, stabilized disability, and reduced accrual of new lesions. However, injectable treatments are associated with flu-like symptoms and injection-site reactions. Neurologists should start pediatric patients on interferon β with 25% to 50% of full dosing and titrate to a full adult dosing over four to six weeks. When initiating glatiramer acetate, neurologists should start children with a full adult dosing, 20 mg subcutaneous daily or 40 mg subcutaneous three times per week.