User login

More Baby Boomers Need HCV Testing

About 3.5 million U.S. adults are chronically infected with hepatitis C (HCV), and 80% of those are baby boomers. As many as 3 out of 4 infected people are not aware of it, according to the CDC, putting them at risk for liver disease, cancer, and death. And most baby boomers aren’t getting tested for the HCV virus.

Between 2013 (when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a recommendation that all people born between 1945 and 1965 be tested) and 2015, the rate of testing among baby boomers rose only from 12.3% to 13.8%. About 10.5 million of the 76.2 million baby boomers have been tested for HCV, say American Cancer Society researchers who analyzed data from the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey.

Half of Americans identified as ever having had HCV received follow-up testing showing they were still infected, suggesting that even among those who receive an initial antibody test, half may not know for sure whether they still carry the virus.

“Hepatitis C has few noticeable symptoms,” says John Ward, MD, director of the CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Program, and left undiagnosed it threatens the health not only of the person with the virus, but those the disease might be transmitted to. Identifying those who are infected is important, he adds, because new treatments can cure the infection and eliminate the risk of transmission.

About 3.5 million U.S. adults are chronically infected with hepatitis C (HCV), and 80% of those are baby boomers. As many as 3 out of 4 infected people are not aware of it, according to the CDC, putting them at risk for liver disease, cancer, and death. And most baby boomers aren’t getting tested for the HCV virus.

Between 2013 (when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a recommendation that all people born between 1945 and 1965 be tested) and 2015, the rate of testing among baby boomers rose only from 12.3% to 13.8%. About 10.5 million of the 76.2 million baby boomers have been tested for HCV, say American Cancer Society researchers who analyzed data from the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey.

Half of Americans identified as ever having had HCV received follow-up testing showing they were still infected, suggesting that even among those who receive an initial antibody test, half may not know for sure whether they still carry the virus.

“Hepatitis C has few noticeable symptoms,” says John Ward, MD, director of the CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Program, and left undiagnosed it threatens the health not only of the person with the virus, but those the disease might be transmitted to. Identifying those who are infected is important, he adds, because new treatments can cure the infection and eliminate the risk of transmission.

About 3.5 million U.S. adults are chronically infected with hepatitis C (HCV), and 80% of those are baby boomers. As many as 3 out of 4 infected people are not aware of it, according to the CDC, putting them at risk for liver disease, cancer, and death. And most baby boomers aren’t getting tested for the HCV virus.

Between 2013 (when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force issued a recommendation that all people born between 1945 and 1965 be tested) and 2015, the rate of testing among baby boomers rose only from 12.3% to 13.8%. About 10.5 million of the 76.2 million baby boomers have been tested for HCV, say American Cancer Society researchers who analyzed data from the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey.

Half of Americans identified as ever having had HCV received follow-up testing showing they were still infected, suggesting that even among those who receive an initial antibody test, half may not know for sure whether they still carry the virus.

“Hepatitis C has few noticeable symptoms,” says John Ward, MD, director of the CDC’s Viral Hepatitis Program, and left undiagnosed it threatens the health not only of the person with the virus, but those the disease might be transmitted to. Identifying those who are infected is important, he adds, because new treatments can cure the infection and eliminate the risk of transmission.

Study supports use of tPA in stroke patients with SCD

A new study suggests that having sickle cell disease (SCD) should not prevent patients from receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to treat ischemic stroke if they otherwise qualify for the treatment.

Researchers compared outcomes of tPA treatment in stroke patients with and without SCD and found no significant differences between the groups with regard to serious complications, length of hospital stay, or in-hospital mortality.

“Having sickle cell disease did not adversely affect any of the indicators we measured,” said Robert J. Adams, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The SCD patients did have a higher rate of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) than patients without SCD, although the rate was not significantly higher. Still, the researchers said further study is needed to look more closely at this outcome.

Dr Adams and his colleagues reported their findings in the journal Stroke.

The team noted that use of tPA has never been contraindicated in SCD, but guidelines recommend acute exchange transfusion for stroke in SCD, rather than tPA.

To gain more insight into the effects of tPA in patients with SCD, the researchers analyzed in-hospital data compiled by the quality improvement program Get With The Guidelines – Stroke.

The data included 2,016,652 stroke patients seen at 1952 participating US hospitals between January 2008 and March 2015. From these patients, the researchers identified 832 with SCD and 3328 age-, sex-, and race-matched controls.

There was no significant difference between the 2 cohorts in the rate of tPA use—8.2% for SCD patients and 9.4% for controls (P=0.3024).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in the timeliness of tPA administration. The median door-to-needle time was 73 minutes for SCD patients and 79 minutes for controls (P=0.3891).

Among patients who received tPA, there was no significant difference in the overall rate of serious complications, which occurred in 6.6% of the SCD patients and 6.0% of controls (P=0.7732).

Serious complications included symptomatic ICH, which occurred in 4.9% of the SCD patients and 3.2% of controls who received tPA (P= 0.4502).

Although this difference was not significant, the researchers said additional studies are needed to track the ICH rate in SCD patients receiving tPA.

The researchers also calculated the odds ratios (ORs) for various outcomes in tPA-treated SCD patients compared to controls.

In an analysis adjusted for multiple covariates, the OR for in-hospital mortality was 1.21 for SCD patients (P=0.4150), the OR for being discharged home was 0.90 (P=0.2686), and the OR for having a hospital stay lasting beyond 4 days was 1.15 (P=0.1151).

“People with sickle cell disease and an acute stroke who would otherwise qualify for tPA did not have worse outcomes than stroke patients who did not have sickle cell disease,” Dr Adams noted.

He and his colleagues said these findings suggest tPA is safe for patients with SCD and could potentially be used as a complementary therapy to red blood cell exchange, the current guideline-recommended frontline therapy for ischemic stroke in patients with SCD.

“These findings suggest that a future randomized trial that compares using red blood cell exchange alone versus combination therapy with tPA and red blood cell exchange should be undertaken to evaluate the outcomes of [ischemic stroke] in patients with sickle cell disease,” said study author Julie Kanter, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. ![]()

A new study suggests that having sickle cell disease (SCD) should not prevent patients from receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to treat ischemic stroke if they otherwise qualify for the treatment.

Researchers compared outcomes of tPA treatment in stroke patients with and without SCD and found no significant differences between the groups with regard to serious complications, length of hospital stay, or in-hospital mortality.

“Having sickle cell disease did not adversely affect any of the indicators we measured,” said Robert J. Adams, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The SCD patients did have a higher rate of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) than patients without SCD, although the rate was not significantly higher. Still, the researchers said further study is needed to look more closely at this outcome.

Dr Adams and his colleagues reported their findings in the journal Stroke.

The team noted that use of tPA has never been contraindicated in SCD, but guidelines recommend acute exchange transfusion for stroke in SCD, rather than tPA.

To gain more insight into the effects of tPA in patients with SCD, the researchers analyzed in-hospital data compiled by the quality improvement program Get With The Guidelines – Stroke.

The data included 2,016,652 stroke patients seen at 1952 participating US hospitals between January 2008 and March 2015. From these patients, the researchers identified 832 with SCD and 3328 age-, sex-, and race-matched controls.

There was no significant difference between the 2 cohorts in the rate of tPA use—8.2% for SCD patients and 9.4% for controls (P=0.3024).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in the timeliness of tPA administration. The median door-to-needle time was 73 minutes for SCD patients and 79 minutes for controls (P=0.3891).

Among patients who received tPA, there was no significant difference in the overall rate of serious complications, which occurred in 6.6% of the SCD patients and 6.0% of controls (P=0.7732).

Serious complications included symptomatic ICH, which occurred in 4.9% of the SCD patients and 3.2% of controls who received tPA (P= 0.4502).

Although this difference was not significant, the researchers said additional studies are needed to track the ICH rate in SCD patients receiving tPA.

The researchers also calculated the odds ratios (ORs) for various outcomes in tPA-treated SCD patients compared to controls.

In an analysis adjusted for multiple covariates, the OR for in-hospital mortality was 1.21 for SCD patients (P=0.4150), the OR for being discharged home was 0.90 (P=0.2686), and the OR for having a hospital stay lasting beyond 4 days was 1.15 (P=0.1151).

“People with sickle cell disease and an acute stroke who would otherwise qualify for tPA did not have worse outcomes than stroke patients who did not have sickle cell disease,” Dr Adams noted.

He and his colleagues said these findings suggest tPA is safe for patients with SCD and could potentially be used as a complementary therapy to red blood cell exchange, the current guideline-recommended frontline therapy for ischemic stroke in patients with SCD.

“These findings suggest that a future randomized trial that compares using red blood cell exchange alone versus combination therapy with tPA and red blood cell exchange should be undertaken to evaluate the outcomes of [ischemic stroke] in patients with sickle cell disease,” said study author Julie Kanter, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. ![]()

A new study suggests that having sickle cell disease (SCD) should not prevent patients from receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) to treat ischemic stroke if they otherwise qualify for the treatment.

Researchers compared outcomes of tPA treatment in stroke patients with and without SCD and found no significant differences between the groups with regard to serious complications, length of hospital stay, or in-hospital mortality.

“Having sickle cell disease did not adversely affect any of the indicators we measured,” said Robert J. Adams, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston.

The SCD patients did have a higher rate of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) than patients without SCD, although the rate was not significantly higher. Still, the researchers said further study is needed to look more closely at this outcome.

Dr Adams and his colleagues reported their findings in the journal Stroke.

The team noted that use of tPA has never been contraindicated in SCD, but guidelines recommend acute exchange transfusion for stroke in SCD, rather than tPA.

To gain more insight into the effects of tPA in patients with SCD, the researchers analyzed in-hospital data compiled by the quality improvement program Get With The Guidelines – Stroke.

The data included 2,016,652 stroke patients seen at 1952 participating US hospitals between January 2008 and March 2015. From these patients, the researchers identified 832 with SCD and 3328 age-, sex-, and race-matched controls.

There was no significant difference between the 2 cohorts in the rate of tPA use—8.2% for SCD patients and 9.4% for controls (P=0.3024).

Likewise, there was no significant difference in the timeliness of tPA administration. The median door-to-needle time was 73 minutes for SCD patients and 79 minutes for controls (P=0.3891).

Among patients who received tPA, there was no significant difference in the overall rate of serious complications, which occurred in 6.6% of the SCD patients and 6.0% of controls (P=0.7732).

Serious complications included symptomatic ICH, which occurred in 4.9% of the SCD patients and 3.2% of controls who received tPA (P= 0.4502).

Although this difference was not significant, the researchers said additional studies are needed to track the ICH rate in SCD patients receiving tPA.

The researchers also calculated the odds ratios (ORs) for various outcomes in tPA-treated SCD patients compared to controls.

In an analysis adjusted for multiple covariates, the OR for in-hospital mortality was 1.21 for SCD patients (P=0.4150), the OR for being discharged home was 0.90 (P=0.2686), and the OR for having a hospital stay lasting beyond 4 days was 1.15 (P=0.1151).

“People with sickle cell disease and an acute stroke who would otherwise qualify for tPA did not have worse outcomes than stroke patients who did not have sickle cell disease,” Dr Adams noted.

He and his colleagues said these findings suggest tPA is safe for patients with SCD and could potentially be used as a complementary therapy to red blood cell exchange, the current guideline-recommended frontline therapy for ischemic stroke in patients with SCD.

“These findings suggest that a future randomized trial that compares using red blood cell exchange alone versus combination therapy with tPA and red blood cell exchange should be undertaken to evaluate the outcomes of [ischemic stroke] in patients with sickle cell disease,” said study author Julie Kanter, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. ![]()

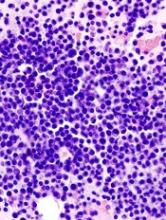

Drug granted orphan designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation for tasquinimod as a treatment for multiple myeloma (MM).

Tasquinimod is an immunomodulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic compound being developed by Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod works by inhibiting the function of S100A9, a pro-inflammatory protein that is elevated in MM and other malignancies.

S100A9 is believed to aid cancer development by recruiting and activating immune cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

Active Biotech AB says that, by targeting the S100A9 pathway, tasquinimod interferes with the accumulation and activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment, which decreases immune suppression and angiogenesis.

Tasquinimod also inhibits the hypoxic response in the tumor by binding to HDAC4, according to Active Biotech AB.

The company says tasquinimod has produced “robust results” in animal models of MM, and research presented at the AACR Annual Meeting 2015 supports this statement.

Investigators found that tasquinimod reduced tumor growth and improved survival in mouse models of MM. And these effects were associated with reduced angiogenesis in the bone marrow.

Tasquinimod was previously under development as a treatment for prostate cancer, but research suggested the drug did not have a favorable risk-benefit ratio in this patient population.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs and biologics intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent rare diseases/disorders affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides companies with certain incentives to develop products for rare diseases. This includes a 50% tax break on research and development, a fee waiver, access to federal grants, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved. ![]()

Topical HDAC inhibitor shows activity in MF

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest a topical, skin-directed histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor can elicit responses in patients with early stage mycosis fungoides (MF).

The drug, remetinostat, was designed to be active in the skin but rapidly broken down and inactivated in blood in order to limit the adverse effects associated with systemic exposure to HDAC inhibitors.

The trial included 60 MF patients who were randomized to receive 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily, 1% remetinostat gel once daily, or 1% remetinostat gel twice daily for between 6 and 12 months.

Results from this trial were recently released by Medivir AB, the company developing remetinostat.

The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with either a complete or partial confirmed response to therapy, assessed using the Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity.

Based on an intent-to-treat analysis, patients receiving the 1% remetinostat gel twice daily arm had the highest proportion of confirmed responses. Eight of 20 patients (40%) responded, which included 1 complete response.

Five of 20 patients (25%) receiving 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily responded, as did 4 of 20 (20%) patients receiving 1% remetinostat gel once daily. None of these responses were complete responses.

Remetinostat was well-tolerated across all the dose groups, according to Medivir. There were no signs of systemic adverse effects, including those associated with systemic HDAC inhibitors.

Based on these data, Medivir expects to initiate discussions with regulatory authorities with the aim of initiating a phase 3 study later this year, and to present full phase 2 trial data at scientific meetings in the second half of 2017.

“Remetinostat was designed to effectively inhibit HDACs within cutaneous lesions but to be rapidly broken down in the bloodstream, preventing the side effects associated with systemically administered HDAC inhibitors,” said Richard Bethell, Medivir’s chief scientific officer.

“Based on the efficacy and safety data from this phase 2 study, we believe that remetinostat is capable of meeting a very important unmet need in patients with this chronic and poorly treated orphan disease.” ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest a topical, skin-directed histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor can elicit responses in patients with early stage mycosis fungoides (MF).

The drug, remetinostat, was designed to be active in the skin but rapidly broken down and inactivated in blood in order to limit the adverse effects associated with systemic exposure to HDAC inhibitors.

The trial included 60 MF patients who were randomized to receive 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily, 1% remetinostat gel once daily, or 1% remetinostat gel twice daily for between 6 and 12 months.

Results from this trial were recently released by Medivir AB, the company developing remetinostat.

The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with either a complete or partial confirmed response to therapy, assessed using the Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity.

Based on an intent-to-treat analysis, patients receiving the 1% remetinostat gel twice daily arm had the highest proportion of confirmed responses. Eight of 20 patients (40%) responded, which included 1 complete response.

Five of 20 patients (25%) receiving 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily responded, as did 4 of 20 (20%) patients receiving 1% remetinostat gel once daily. None of these responses were complete responses.

Remetinostat was well-tolerated across all the dose groups, according to Medivir. There were no signs of systemic adverse effects, including those associated with systemic HDAC inhibitors.

Based on these data, Medivir expects to initiate discussions with regulatory authorities with the aim of initiating a phase 3 study later this year, and to present full phase 2 trial data at scientific meetings in the second half of 2017.

“Remetinostat was designed to effectively inhibit HDACs within cutaneous lesions but to be rapidly broken down in the bloodstream, preventing the side effects associated with systemically administered HDAC inhibitors,” said Richard Bethell, Medivir’s chief scientific officer.

“Based on the efficacy and safety data from this phase 2 study, we believe that remetinostat is capable of meeting a very important unmet need in patients with this chronic and poorly treated orphan disease.” ![]()

Results of a phase 2 trial suggest a topical, skin-directed histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor can elicit responses in patients with early stage mycosis fungoides (MF).

The drug, remetinostat, was designed to be active in the skin but rapidly broken down and inactivated in blood in order to limit the adverse effects associated with systemic exposure to HDAC inhibitors.

The trial included 60 MF patients who were randomized to receive 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily, 1% remetinostat gel once daily, or 1% remetinostat gel twice daily for between 6 and 12 months.

Results from this trial were recently released by Medivir AB, the company developing remetinostat.

The primary endpoint of the study was the proportion of patients with either a complete or partial confirmed response to therapy, assessed using the Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity.

Based on an intent-to-treat analysis, patients receiving the 1% remetinostat gel twice daily arm had the highest proportion of confirmed responses. Eight of 20 patients (40%) responded, which included 1 complete response.

Five of 20 patients (25%) receiving 0.5% remetinostat gel twice daily responded, as did 4 of 20 (20%) patients receiving 1% remetinostat gel once daily. None of these responses were complete responses.

Remetinostat was well-tolerated across all the dose groups, according to Medivir. There were no signs of systemic adverse effects, including those associated with systemic HDAC inhibitors.

Based on these data, Medivir expects to initiate discussions with regulatory authorities with the aim of initiating a phase 3 study later this year, and to present full phase 2 trial data at scientific meetings in the second half of 2017.

“Remetinostat was designed to effectively inhibit HDACs within cutaneous lesions but to be rapidly broken down in the bloodstream, preventing the side effects associated with systemically administered HDAC inhibitors,” said Richard Bethell, Medivir’s chief scientific officer.

“Based on the efficacy and safety data from this phase 2 study, we believe that remetinostat is capable of meeting a very important unmet need in patients with this chronic and poorly treated orphan disease.” ![]()

Portal allows hemophilia patients to share data with providers

Novo Nordisk has launched a web-based portal that allows hemophilia patients to share real-time data on their treatment and bleeding events with their healthcare providers.

The portal, HemaGo™ XChange, is an extension of Novo Nordisk’s HemaGo™ mobile application and website, which were launched in 2012.

Data a patient enters into the HemaGo™ diary can be shared through the HemaGo™ XChange with the patient’s hemophilia treatment network.

Patients may also choose to have these data entered into the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network’s (ATHN) national database of bleeding disorder treatment information.

“We developed HemaGo™ XChange to help drive progress in hemophilia management by turning static data into usable information for people with hemophilia, their care teams, and even researchers,” said John Spera, vice-president of biopharmaceuticals marketing at Novo Nordisk Inc.

“With timely information about the daily experiences of patients, including bleeds, healthcare providers can adjust their care to better fit patient lives.”

Patients using HemaGo™ can:

- Provide information to their healthcare team, including access to treatment and bleed data, in real time through the HemaGo™ XChange web portal

- Choose to email data directly from the app or website at any time

- Opt-in through their hemophilia treatment center to have their data integrated into ATHN’s national database of bleeding disorder treatment information. ATHN will use and share these data with hemophilia treatment centers to foster its mission of advancing knowledge and transforming care for the bleeding and clotting disorders community.

Providers invited by patients to connect via the HemaGo™ XChange portal can:

- View details about treatments, bleeds, and more for multiple patients

- Track when and how much factor is used; the type of infusion, vial, and dosing amounts; and information about any other medications

- View data on the type, location, duration, frequency, and status of bleeds

- View patient and caregiver life experiences, such as pain and health scores or how a bleeding disorder has affected work, school, or other activities

- Download in-depth reports for all recorded information.

Novo Nordisk does not have access to patient-specific information. The company’s access is restricted to de-identified data in which the individual sources of the data cannot be identified, in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy and Security Rules.

To download the HemaGo™ app or join the HemaGo™ XChange, visit www.HemaGo.com and www.HGXchange.com. The HemaGo™ app is available for iPhone and Android phones. ![]()

Novo Nordisk has launched a web-based portal that allows hemophilia patients to share real-time data on their treatment and bleeding events with their healthcare providers.

The portal, HemaGo™ XChange, is an extension of Novo Nordisk’s HemaGo™ mobile application and website, which were launched in 2012.

Data a patient enters into the HemaGo™ diary can be shared through the HemaGo™ XChange with the patient’s hemophilia treatment network.

Patients may also choose to have these data entered into the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network’s (ATHN) national database of bleeding disorder treatment information.

“We developed HemaGo™ XChange to help drive progress in hemophilia management by turning static data into usable information for people with hemophilia, their care teams, and even researchers,” said John Spera, vice-president of biopharmaceuticals marketing at Novo Nordisk Inc.

“With timely information about the daily experiences of patients, including bleeds, healthcare providers can adjust their care to better fit patient lives.”

Patients using HemaGo™ can:

- Provide information to their healthcare team, including access to treatment and bleed data, in real time through the HemaGo™ XChange web portal

- Choose to email data directly from the app or website at any time

- Opt-in through their hemophilia treatment center to have their data integrated into ATHN’s national database of bleeding disorder treatment information. ATHN will use and share these data with hemophilia treatment centers to foster its mission of advancing knowledge and transforming care for the bleeding and clotting disorders community.

Providers invited by patients to connect via the HemaGo™ XChange portal can:

- View details about treatments, bleeds, and more for multiple patients

- Track when and how much factor is used; the type of infusion, vial, and dosing amounts; and information about any other medications

- View data on the type, location, duration, frequency, and status of bleeds

- View patient and caregiver life experiences, such as pain and health scores or how a bleeding disorder has affected work, school, or other activities

- Download in-depth reports for all recorded information.

Novo Nordisk does not have access to patient-specific information. The company’s access is restricted to de-identified data in which the individual sources of the data cannot be identified, in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy and Security Rules.

To download the HemaGo™ app or join the HemaGo™ XChange, visit www.HemaGo.com and www.HGXchange.com. The HemaGo™ app is available for iPhone and Android phones. ![]()

Novo Nordisk has launched a web-based portal that allows hemophilia patients to share real-time data on their treatment and bleeding events with their healthcare providers.

The portal, HemaGo™ XChange, is an extension of Novo Nordisk’s HemaGo™ mobile application and website, which were launched in 2012.

Data a patient enters into the HemaGo™ diary can be shared through the HemaGo™ XChange with the patient’s hemophilia treatment network.

Patients may also choose to have these data entered into the American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network’s (ATHN) national database of bleeding disorder treatment information.

“We developed HemaGo™ XChange to help drive progress in hemophilia management by turning static data into usable information for people with hemophilia, their care teams, and even researchers,” said John Spera, vice-president of biopharmaceuticals marketing at Novo Nordisk Inc.

“With timely information about the daily experiences of patients, including bleeds, healthcare providers can adjust their care to better fit patient lives.”

Patients using HemaGo™ can:

- Provide information to their healthcare team, including access to treatment and bleed data, in real time through the HemaGo™ XChange web portal

- Choose to email data directly from the app or website at any time

- Opt-in through their hemophilia treatment center to have their data integrated into ATHN’s national database of bleeding disorder treatment information. ATHN will use and share these data with hemophilia treatment centers to foster its mission of advancing knowledge and transforming care for the bleeding and clotting disorders community.

Providers invited by patients to connect via the HemaGo™ XChange portal can:

- View details about treatments, bleeds, and more for multiple patients

- Track when and how much factor is used; the type of infusion, vial, and dosing amounts; and information about any other medications

- View data on the type, location, duration, frequency, and status of bleeds

- View patient and caregiver life experiences, such as pain and health scores or how a bleeding disorder has affected work, school, or other activities

- Download in-depth reports for all recorded information.

Novo Nordisk does not have access to patient-specific information. The company’s access is restricted to de-identified data in which the individual sources of the data cannot be identified, in accordance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy and Security Rules.

To download the HemaGo™ app or join the HemaGo™ XChange, visit www.HemaGo.com and www.HGXchange.com. The HemaGo™ app is available for iPhone and Android phones. ![]()

Dry, thickened skin on hand

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP asked the patient to show him how he moved about and immediately noticed that the involved area corresponded directly to the part of the hand that pressed upon his cane. He then diagnosed the patient with unilateral hand eczema related to friction.

The FP asked the patient if he would be willing to get a soft glove to wear on his hand while walking. The patient was amenable to this suggestion, but also asked if something could be done for the dry, thickened area that had already built up on his palm.

The FP prescribed ammonium lactate 12% to be applied twice daily, as it is a good moisturizing keratolytic that helps to break down keratin and soften the skin. He also gave the patient a prescription for 0.1% triamcinolone ointment to rub into the affected area at night before going to sleep. The FP recommended not using this during the daytime as it might make the patient’s hand slippery, leading to a fall if he lost his grip on the cane. At a follow-up visit 2 months later, the patient had improved and was very happy with the result.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Hand eczema. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:597-602.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

When You Can’t Make a Rash Diagnosis

ANSWER

The false statement—and therefore the correct choice—is that MF is almost always fatal (choice “a”). MF can often be controlled, if not completely cured.

DISCUSSION

In its early stages, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) can manifest with an innocuous-appearing rash, notable for its chronicity and resistance to treatment. One example is poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA), which is identified by nonblanchable atrophic patches with fine surface vascularity that often manifest around the waistline or groin. Left undiagnosed and untreated, PVA can slowly progress to a more advanced stage, as was the case with this patient.

Several cancers can present with rash, including extramammary Paget disease, superficial squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease), and various types of metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

The confirmation of CTCL/MF may require serial biopsies over time, as the diagnostic signs can take years to become detectable. These specimens must be accompanied by pertinent clinical information to suggest a differential that includes this lymphoma.

Early-stage CTCL can be controlled with topical steroids, but as the condition advances, specialized treatment is needed. The tumor stage observed in

ANSWER

The false statement—and therefore the correct choice—is that MF is almost always fatal (choice “a”). MF can often be controlled, if not completely cured.

DISCUSSION

In its early stages, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) can manifest with an innocuous-appearing rash, notable for its chronicity and resistance to treatment. One example is poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA), which is identified by nonblanchable atrophic patches with fine surface vascularity that often manifest around the waistline or groin. Left undiagnosed and untreated, PVA can slowly progress to a more advanced stage, as was the case with this patient.

Several cancers can present with rash, including extramammary Paget disease, superficial squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease), and various types of metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

The confirmation of CTCL/MF may require serial biopsies over time, as the diagnostic signs can take years to become detectable. These specimens must be accompanied by pertinent clinical information to suggest a differential that includes this lymphoma.

Early-stage CTCL can be controlled with topical steroids, but as the condition advances, specialized treatment is needed. The tumor stage observed in

ANSWER

The false statement—and therefore the correct choice—is that MF is almost always fatal (choice “a”). MF can often be controlled, if not completely cured.

DISCUSSION

In its early stages, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) can manifest with an innocuous-appearing rash, notable for its chronicity and resistance to treatment. One example is poikiloderma vasculare atrophicans (PVA), which is identified by nonblanchable atrophic patches with fine surface vascularity that often manifest around the waistline or groin. Left undiagnosed and untreated, PVA can slowly progress to a more advanced stage, as was the case with this patient.

Several cancers can present with rash, including extramammary Paget disease, superficial squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen disease), and various types of metastatic cancer (eg, breast, colon, lung).

The confirmation of CTCL/MF may require serial biopsies over time, as the diagnostic signs can take years to become detectable. These specimens must be accompanied by pertinent clinical information to suggest a differential that includes this lymphoma.

Early-stage CTCL can be controlled with topical steroids, but as the condition advances, specialized treatment is needed. The tumor stage observed in

For years, this 64-year-old man has complained of itching and a rash around his head and neck. He has consulted several primary care providers—and even a dermatologist. A punch biopsy performed by that provider yielded no clear diagnosis. The patient was advised to return for follow-up but never did so.

Treatment was attempted with a succession of medications; none resulted in any improvement. The list includes antifungal creams (econazole, clotrimazole, and miconazole), an oral antifungal medication (a one-month course of terbinafine 250 mg/d), and a corticosteroid (a one-month course of prednisone 20 mg/d).

In addition to the rash and pruritus, the patient feels “lumps” in the affected areas. He also reports feeling more tired than usual. Prior to the onset of these symptoms, his only complaint was lifelong eczema.

Large infiltrative plaques are seen on both sides of his neck, extending into his ears and onto his scalp. A few exceed 8 cm in diameter, and all have smooth surfaces with no epidermal disturbance. Several discrete, 2- to 4-cm, fixed nodules are also seen and felt on his neck below these plaques.

A 5-mm punch biopsy is performed on one of the plaques on his occipital scalp; the pathology report shows only chronic changes consistent with eczema. The decision is made to perform another biopsy. A deeper, wider, 5-cm wedge from the left preauricular plaque is taken and submitted. The report shows changes consistent with tumor-stage mycosis fungoides (MF).

Both diabetes types increase markedly among youths

The annual incidence of both types 1 and 2 diabetes markedly increased among youths between 2002 and 2012, especially among those in minority racial and ethnic groups, according to a report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers analyzed trends in diabetes incidence in the observational Search for Diabetes in Youth study, which conducts annual population-based case ascertainment of the disease in people aged 0-20 years. SEARCH is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

In this analysis of SEARCH data, there were 11,245 youths with type 1 diabetes in 54,239,600 person-years of surveillance and 2,846 with type 2 diabetes in 28,029,000 person-years of surveillance.

“We estimated that approximately 15,900 cases of type 1 diabetes were diagnosed annually in the U.S. in the 2002-2003 period, and this number increased to 17,900 annually in the 2011-2012 period. Overall, the adjusted annual relative increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes was 1.8%,” noted Elizabeth J. Mayer-Davis, PhD, of the departments of nutrition and medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 101056/NEJMoa1610187).

Similarly, they estimated that approximately 3,800 cases of type 2 diabetes were diagnosed in the first year of the study, increasing to 5,300 in the final year. The annual relative increase in type 2 diabetes was 4.8%.

The rate of increase varied across the five major ethnic groups studied: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, Asians or Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. Type 1 diabetes incidence rose rapidly among Hispanic youths, and type 2 diabetes rose rapidly in all racial and ethnic groups other than whites, with the greatest rate of increase among Native Americans.

These increases suggest “a growing disease burden that will not be shared equally” because of differences among ethnic groups in barriers to care, methods of treatment, and clinical outcomes. “These findings highlight the critical need to identify approaches to reduce disparities among racial and ethnic groups,” Dr. Mayer-Davis and her associates noted.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Mayer-Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. One of her associates reported serving as a consultant to Denka-Seiken and MedTest DX.

This study by Mayer-Davis et al. provides the most current data available on the incidence of diabetes in this age group.

The consequence of this increase in diabetes among youths is that the overall disease burden on public health is actually increasing, despite improvements in mortality and CVD rates among older diabetes patients.

According to the 2015 Global Burden of Disease report, the number of years lived with disability has increased by 32.5% and the number of years of life lost has increased by 25.4%.

What do the marked increase in the incidence of diabetes and more people at risk imply about therapy? Data from two large studies over the past several decades support that intensive glycemic control improved outcomes in persons with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. But what is missing, despite a growing understanding about the pathogenesis of each condition, is knowledge about how best to lower the number of new cases and how best to treat problems once they arise in persons with diabetes.

It is clear that we are far from controlling the negative effects of diabetes on health worldwide. As the prevalence increases, we clearly need new approaches to reduce the burden of this disease on public health.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, M.D., and John A. Jarcho, M.D., are deputy editors of The New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Ingelfinger and Dr. Jarcho made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Mayer-Davis’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1616575).

This study by Mayer-Davis et al. provides the most current data available on the incidence of diabetes in this age group.

The consequence of this increase in diabetes among youths is that the overall disease burden on public health is actually increasing, despite improvements in mortality and CVD rates among older diabetes patients.

According to the 2015 Global Burden of Disease report, the number of years lived with disability has increased by 32.5% and the number of years of life lost has increased by 25.4%.

What do the marked increase in the incidence of diabetes and more people at risk imply about therapy? Data from two large studies over the past several decades support that intensive glycemic control improved outcomes in persons with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. But what is missing, despite a growing understanding about the pathogenesis of each condition, is knowledge about how best to lower the number of new cases and how best to treat problems once they arise in persons with diabetes.

It is clear that we are far from controlling the negative effects of diabetes on health worldwide. As the prevalence increases, we clearly need new approaches to reduce the burden of this disease on public health.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, M.D., and John A. Jarcho, M.D., are deputy editors of The New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Ingelfinger and Dr. Jarcho made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Mayer-Davis’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1616575).

This study by Mayer-Davis et al. provides the most current data available on the incidence of diabetes in this age group.

The consequence of this increase in diabetes among youths is that the overall disease burden on public health is actually increasing, despite improvements in mortality and CVD rates among older diabetes patients.

According to the 2015 Global Burden of Disease report, the number of years lived with disability has increased by 32.5% and the number of years of life lost has increased by 25.4%.

What do the marked increase in the incidence of diabetes and more people at risk imply about therapy? Data from two large studies over the past several decades support that intensive glycemic control improved outcomes in persons with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. But what is missing, despite a growing understanding about the pathogenesis of each condition, is knowledge about how best to lower the number of new cases and how best to treat problems once they arise in persons with diabetes.

It is clear that we are far from controlling the negative effects of diabetes on health worldwide. As the prevalence increases, we clearly need new approaches to reduce the burden of this disease on public health.

Julie R. Ingelfinger, M.D., and John A. Jarcho, M.D., are deputy editors of The New England Journal of Medicine. They reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Ingelfinger and Dr. Jarcho made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Mayer-Davis’s report (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1616575).

The annual incidence of both types 1 and 2 diabetes markedly increased among youths between 2002 and 2012, especially among those in minority racial and ethnic groups, according to a report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers analyzed trends in diabetes incidence in the observational Search for Diabetes in Youth study, which conducts annual population-based case ascertainment of the disease in people aged 0-20 years. SEARCH is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

In this analysis of SEARCH data, there were 11,245 youths with type 1 diabetes in 54,239,600 person-years of surveillance and 2,846 with type 2 diabetes in 28,029,000 person-years of surveillance.

“We estimated that approximately 15,900 cases of type 1 diabetes were diagnosed annually in the U.S. in the 2002-2003 period, and this number increased to 17,900 annually in the 2011-2012 period. Overall, the adjusted annual relative increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes was 1.8%,” noted Elizabeth J. Mayer-Davis, PhD, of the departments of nutrition and medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 101056/NEJMoa1610187).

Similarly, they estimated that approximately 3,800 cases of type 2 diabetes were diagnosed in the first year of the study, increasing to 5,300 in the final year. The annual relative increase in type 2 diabetes was 4.8%.

The rate of increase varied across the five major ethnic groups studied: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, Asians or Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. Type 1 diabetes incidence rose rapidly among Hispanic youths, and type 2 diabetes rose rapidly in all racial and ethnic groups other than whites, with the greatest rate of increase among Native Americans.

These increases suggest “a growing disease burden that will not be shared equally” because of differences among ethnic groups in barriers to care, methods of treatment, and clinical outcomes. “These findings highlight the critical need to identify approaches to reduce disparities among racial and ethnic groups,” Dr. Mayer-Davis and her associates noted.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Mayer-Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. One of her associates reported serving as a consultant to Denka-Seiken and MedTest DX.

The annual incidence of both types 1 and 2 diabetes markedly increased among youths between 2002 and 2012, especially among those in minority racial and ethnic groups, according to a report published online April 13 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Researchers analyzed trends in diabetes incidence in the observational Search for Diabetes in Youth study, which conducts annual population-based case ascertainment of the disease in people aged 0-20 years. SEARCH is funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

In this analysis of SEARCH data, there were 11,245 youths with type 1 diabetes in 54,239,600 person-years of surveillance and 2,846 with type 2 diabetes in 28,029,000 person-years of surveillance.

“We estimated that approximately 15,900 cases of type 1 diabetes were diagnosed annually in the U.S. in the 2002-2003 period, and this number increased to 17,900 annually in the 2011-2012 period. Overall, the adjusted annual relative increase in the incidence of type 1 diabetes was 1.8%,” noted Elizabeth J. Mayer-Davis, PhD, of the departments of nutrition and medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and her associates (N Engl J Med. 2017 April 13. doi: 101056/NEJMoa1610187).

Similarly, they estimated that approximately 3,800 cases of type 2 diabetes were diagnosed in the first year of the study, increasing to 5,300 in the final year. The annual relative increase in type 2 diabetes was 4.8%.

The rate of increase varied across the five major ethnic groups studied: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, Asians or Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. Type 1 diabetes incidence rose rapidly among Hispanic youths, and type 2 diabetes rose rapidly in all racial and ethnic groups other than whites, with the greatest rate of increase among Native Americans.

These increases suggest “a growing disease burden that will not be shared equally” because of differences among ethnic groups in barriers to care, methods of treatment, and clinical outcomes. “These findings highlight the critical need to identify approaches to reduce disparities among racial and ethnic groups,” Dr. Mayer-Davis and her associates noted.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Mayer-Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. One of her associates reported serving as a consultant to Denka-Seiken and MedTest DX.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Both types 1 and 2 diabetes increased markedly among youths between 2002 and 2012, especially among those in minority racial and ethnic groups.

Major finding: The incidence of type 1 diabetes increased an estimated 1.8% per year and that of type 2 diabetes increased 4.8% per year between 2002 and 2012.

Data source: An observational study assessing a nationally representative sample of youths aged 0-20 years in five states, including 11,245 with type 1 and 2,846 with type 2 diabetes.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funded the study. Dr. Mayer-Davis reported having no relevant disclosures. One of her associates reported serving as a consultant to Denka-Seiken and MedTest DX.

Coverage denials plague U.S. PCSK9-inhibitor prescriptions

WASHINGTON – During the first year that the lipid-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors were on the U.S. market, 2015-2016, fewer than half the patients prescribed the drug had it covered through their health insurance, based on an analysis of prescriptions written for more than 45,000 patients.

On top of that, about a third of patients with health insurance that eventually agreed to cover the notoriously expensive PCSK (proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type) 9 inhibitors failed to actually collect their medication, possibly because of a sizable copay, which meant that, in total, fewer than a third of U.S. patients prescribed these drugs actually began using them, Ann Marie Navar, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The recent PCSK9-inhibitor experience highlighting the frequent preauthorization roadblocks and denied coverage that providers and patients must navigate is “one of the dirty little secrets of American medicine,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a discussant for the study and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Navar countered that these problems may be a secret for many Americans “but it’s not a secret for providers. We know the problems patients have getting drugs covered through the prior authorization process.”

Symphony Health’s records included 45,029 U.S. patients who received a first-time PCSK9-inhibitor prescription during the 12 months studied. Just over half were prescriptions exclusively covered by government-funded insurance (with 90% of these covered through Medicaid), 40% exclusively by a commercial insurer, and the balance subject to dual coverage. Nearly half the prescriptions were written by cardiologists, 37% by primary care physicians, and most of the remaining 15% came from endocrinologists.

Among these prescriptions, 79% received an initial rejection. Following appeals, 53% were rejected and 47% covered. Among the more than 21,000 prescriptions approved for coverage, 13,892 (31% of the 45,029) were actually received by patients, Dr. Navar reported.

During the first several months following availability of the PCSK9 inhibitors, the number of new prescriptions steadily rose until a plateau occurred by about April 2016 of about 6,000 new prescriptions written per month. During each of the 12 months examined, the proportion of prescriptions denied coverage remained roughly constant, suggesting that clinicians developed no insights over time into how to better the prospect for ultimate insurance coverage.

In a multivariate analysis certain aspects of the prescribing and coverage process linked with significantly better rates of patients actually receiving the PCSK9 inhibitor. Prescriptions filled at mail-order pharmacies were over fourfold more likely to be received by patients than those filled at retail pharmacies. Prescriptions written by cardiologists were 80% more likely to be received than those written by primary care physicians; those written by endocrinologists were 30% more likely to be filled. Patients who relied exclusively on a government insurance plan had a threefold greater filling rate than those who exclusively had commercial insurance, and patients with both government and commercial insurance had a fourfold greater rate of receiving their prescription, compared with commercial-only patients. Patients who used a manufacturer’s coupon to help reduce the cost of their prescription had a 17-fold higher rate of receiving the drug, compared with patients who did not use a coupon.

A final set of findings underscored the great variability in the approval process that patients encountered. Among the 13,892 prescriptions that were actually dispensed, 45% were dispensed within 1 day of when the prescription was written, but the median time for dispensing wasn’t reached until the tenth day, and for a quarter of the dispenses the lag from writing the prescription to getting it into patients’ hands was greater than 1 month. Rates of coverage denials also varied widely depending on the specific commercial insurers involved and the specific pharmacy benefit manager. Among the top 10 commercial insurers included in the data set, the rate of coverage denial ranged from 33% to 78%.

This variability suggested that many denials were not simply because of clinical factors. Some commercial insurers “introduce vigorous and sometimes burdensome prior authorization procedures,” Dr. Navar said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

WASHINGTON – During the first year that the lipid-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors were on the U.S. market, 2015-2016, fewer than half the patients prescribed the drug had it covered through their health insurance, based on an analysis of prescriptions written for more than 45,000 patients.

On top of that, about a third of patients with health insurance that eventually agreed to cover the notoriously expensive PCSK (proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type) 9 inhibitors failed to actually collect their medication, possibly because of a sizable copay, which meant that, in total, fewer than a third of U.S. patients prescribed these drugs actually began using them, Ann Marie Navar, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The recent PCSK9-inhibitor experience highlighting the frequent preauthorization roadblocks and denied coverage that providers and patients must navigate is “one of the dirty little secrets of American medicine,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a discussant for the study and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Navar countered that these problems may be a secret for many Americans “but it’s not a secret for providers. We know the problems patients have getting drugs covered through the prior authorization process.”

Symphony Health’s records included 45,029 U.S. patients who received a first-time PCSK9-inhibitor prescription during the 12 months studied. Just over half were prescriptions exclusively covered by government-funded insurance (with 90% of these covered through Medicaid), 40% exclusively by a commercial insurer, and the balance subject to dual coverage. Nearly half the prescriptions were written by cardiologists, 37% by primary care physicians, and most of the remaining 15% came from endocrinologists.

Among these prescriptions, 79% received an initial rejection. Following appeals, 53% were rejected and 47% covered. Among the more than 21,000 prescriptions approved for coverage, 13,892 (31% of the 45,029) were actually received by patients, Dr. Navar reported.

During the first several months following availability of the PCSK9 inhibitors, the number of new prescriptions steadily rose until a plateau occurred by about April 2016 of about 6,000 new prescriptions written per month. During each of the 12 months examined, the proportion of prescriptions denied coverage remained roughly constant, suggesting that clinicians developed no insights over time into how to better the prospect for ultimate insurance coverage.

In a multivariate analysis certain aspects of the prescribing and coverage process linked with significantly better rates of patients actually receiving the PCSK9 inhibitor. Prescriptions filled at mail-order pharmacies were over fourfold more likely to be received by patients than those filled at retail pharmacies. Prescriptions written by cardiologists were 80% more likely to be received than those written by primary care physicians; those written by endocrinologists were 30% more likely to be filled. Patients who relied exclusively on a government insurance plan had a threefold greater filling rate than those who exclusively had commercial insurance, and patients with both government and commercial insurance had a fourfold greater rate of receiving their prescription, compared with commercial-only patients. Patients who used a manufacturer’s coupon to help reduce the cost of their prescription had a 17-fold higher rate of receiving the drug, compared with patients who did not use a coupon.

A final set of findings underscored the great variability in the approval process that patients encountered. Among the 13,892 prescriptions that were actually dispensed, 45% were dispensed within 1 day of when the prescription was written, but the median time for dispensing wasn’t reached until the tenth day, and for a quarter of the dispenses the lag from writing the prescription to getting it into patients’ hands was greater than 1 month. Rates of coverage denials also varied widely depending on the specific commercial insurers involved and the specific pharmacy benefit manager. Among the top 10 commercial insurers included in the data set, the rate of coverage denial ranged from 33% to 78%.

This variability suggested that many denials were not simply because of clinical factors. Some commercial insurers “introduce vigorous and sometimes burdensome prior authorization procedures,” Dr. Navar said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

WASHINGTON – During the first year that the lipid-lowering PCSK9 inhibitors were on the U.S. market, 2015-2016, fewer than half the patients prescribed the drug had it covered through their health insurance, based on an analysis of prescriptions written for more than 45,000 patients.

On top of that, about a third of patients with health insurance that eventually agreed to cover the notoriously expensive PCSK (proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type) 9 inhibitors failed to actually collect their medication, possibly because of a sizable copay, which meant that, in total, fewer than a third of U.S. patients prescribed these drugs actually began using them, Ann Marie Navar, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The recent PCSK9-inhibitor experience highlighting the frequent preauthorization roadblocks and denied coverage that providers and patients must navigate is “one of the dirty little secrets of American medicine,” commented Mariell Jessup, MD, a discussant for the study and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Dr. Navar countered that these problems may be a secret for many Americans “but it’s not a secret for providers. We know the problems patients have getting drugs covered through the prior authorization process.”

Symphony Health’s records included 45,029 U.S. patients who received a first-time PCSK9-inhibitor prescription during the 12 months studied. Just over half were prescriptions exclusively covered by government-funded insurance (with 90% of these covered through Medicaid), 40% exclusively by a commercial insurer, and the balance subject to dual coverage. Nearly half the prescriptions were written by cardiologists, 37% by primary care physicians, and most of the remaining 15% came from endocrinologists.

Among these prescriptions, 79% received an initial rejection. Following appeals, 53% were rejected and 47% covered. Among the more than 21,000 prescriptions approved for coverage, 13,892 (31% of the 45,029) were actually received by patients, Dr. Navar reported.

During the first several months following availability of the PCSK9 inhibitors, the number of new prescriptions steadily rose until a plateau occurred by about April 2016 of about 6,000 new prescriptions written per month. During each of the 12 months examined, the proportion of prescriptions denied coverage remained roughly constant, suggesting that clinicians developed no insights over time into how to better the prospect for ultimate insurance coverage.

In a multivariate analysis certain aspects of the prescribing and coverage process linked with significantly better rates of patients actually receiving the PCSK9 inhibitor. Prescriptions filled at mail-order pharmacies were over fourfold more likely to be received by patients than those filled at retail pharmacies. Prescriptions written by cardiologists were 80% more likely to be received than those written by primary care physicians; those written by endocrinologists were 30% more likely to be filled. Patients who relied exclusively on a government insurance plan had a threefold greater filling rate than those who exclusively had commercial insurance, and patients with both government and commercial insurance had a fourfold greater rate of receiving their prescription, compared with commercial-only patients. Patients who used a manufacturer’s coupon to help reduce the cost of their prescription had a 17-fold higher rate of receiving the drug, compared with patients who did not use a coupon.

A final set of findings underscored the great variability in the approval process that patients encountered. Among the 13,892 prescriptions that were actually dispensed, 45% were dispensed within 1 day of when the prescription was written, but the median time for dispensing wasn’t reached until the tenth day, and for a quarter of the dispenses the lag from writing the prescription to getting it into patients’ hands was greater than 1 month. Rates of coverage denials also varied widely depending on the specific commercial insurers involved and the specific pharmacy benefit manager. Among the top 10 commercial insurers included in the data set, the rate of coverage denial ranged from 33% to 78%.

This variability suggested that many denials were not simply because of clinical factors. Some commercial insurers “introduce vigorous and sometimes burdensome prior authorization procedures,” Dr. Navar said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT ACC 17

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Coverage denials occurred for 53% of U.S. patients who received a new prescription for a PCSK9 inhibitor during 2015-2016.

Data source: Review of 45,029 U.S. patients who received a new prescription for a PCSK9 inhibitor in a Symphony Health database.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Amgen, the company that markets evolocumab (Repatha). Dr. Navar has received research support from Amgen, Sanofi, and Regeneron and has been a consultant to Sanofi.

APA Presidential Symposium will focus on trials in geriatric psychiatry

Designing clinical trials within a psychiatric practice is a challenging endeavor, regardless of the population. But, setting up trials for older adults can involve unique ethical and economic considerations.

On Saturday, May 20, a panel of four experts will explore these issues in an Invited Presidential Symposium at this year’s annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego. The symposium, which will be held that morning from 8 to 11 a.m., will feature Mary Sano, PhD, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; Joan A. Mackell, PhD, of JM Neuroscience, New York; Olga Brawman-Mintzer, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; and Maria I. Lapid, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Sano will chair the symposium, and Dr. Brawman-Mintzer will be the cochair.

The discussion will examine some of the basics of clinical trial design for geriatric psychiatry for several disorders, including dementia and depression, and for numerous conditions, including agitation and behavioral disturbances. It will also explore other key issues, such as the regulatory knowledge needed to conduct clinical trials, the role of the institutional review board in protecting human subjects, and whether the protocol works and will pay the bills.

It will take place on the upper level of the San Diego Convention Center (session ID: 8012). To look up other sessions, check out the APA’s search function.

Designing clinical trials within a psychiatric practice is a challenging endeavor, regardless of the population. But, setting up trials for older adults can involve unique ethical and economic considerations.

On Saturday, May 20, a panel of four experts will explore these issues in an Invited Presidential Symposium at this year’s annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego. The symposium, which will be held that morning from 8 to 11 a.m., will feature Mary Sano, PhD, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; Joan A. Mackell, PhD, of JM Neuroscience, New York; Olga Brawman-Mintzer, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; and Maria I. Lapid, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Sano will chair the symposium, and Dr. Brawman-Mintzer will be the cochair.

The discussion will examine some of the basics of clinical trial design for geriatric psychiatry for several disorders, including dementia and depression, and for numerous conditions, including agitation and behavioral disturbances. It will also explore other key issues, such as the regulatory knowledge needed to conduct clinical trials, the role of the institutional review board in protecting human subjects, and whether the protocol works and will pay the bills.

It will take place on the upper level of the San Diego Convention Center (session ID: 8012). To look up other sessions, check out the APA’s search function.

Designing clinical trials within a psychiatric practice is a challenging endeavor, regardless of the population. But, setting up trials for older adults can involve unique ethical and economic considerations.

On Saturday, May 20, a panel of four experts will explore these issues in an Invited Presidential Symposium at this year’s annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in San Diego. The symposium, which will be held that morning from 8 to 11 a.m., will feature Mary Sano, PhD, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York; Joan A. Mackell, PhD, of JM Neuroscience, New York; Olga Brawman-Mintzer, MD, of the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; and Maria I. Lapid, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Dr. Sano will chair the symposium, and Dr. Brawman-Mintzer will be the cochair.

The discussion will examine some of the basics of clinical trial design for geriatric psychiatry for several disorders, including dementia and depression, and for numerous conditions, including agitation and behavioral disturbances. It will also explore other key issues, such as the regulatory knowledge needed to conduct clinical trials, the role of the institutional review board in protecting human subjects, and whether the protocol works and will pay the bills.

It will take place on the upper level of the San Diego Convention Center (session ID: 8012). To look up other sessions, check out the APA’s search function.