User login

Androgen receptor screening not ready for triple-negative breast cancer

LAS VEGAS – Despite the early promise of antiandrogen therapy, it’s not time yet to routinely screen women with triple-negative breast cancer for androgen receptors, according to Tiffany A. Traina, MD, the head of research into the disease at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

There’s no standardized test for androgen receptors in breast cancer, so people “are doing different kinds of testing.” In the literature, “the range of AR positivity is anywhere from 12% to 79%, which reflects how we are all over the map in methodology; you might just as well throw a dart at the board. I would encourage screening in the context of the ongoing trials,” Dr. Traina said.

More than a decade ago, Memorial Sloan Kettering found a subset of TNBC that had ARs, which was peculiar because the tumors weren’t otherwise responsive to hormones. Androgen exposure increased growth, but the AR antagonist flutamide (Eulexin)blocked it. “It was thought provoking. There are a lot of drugs in the prostate cancer world” such as flutamide that shut down androgens, she said (Oncogene. 2006 Jun 29;25[28]:3994-4008).

Several have been tried, and investigations are ongoing. The work matters because TNBC is a particularly bad diagnosis. Blocking androgens seems to give some women a few more months of life.

Dr. Traina was the senior author in an early proof-of-concept study for AR blockade that involved 26 women with metastatic TNBC who had been through up to eight prior chemotherapy regimens. The women received 150 mg daily of the prostate cancer AR antagonist bicalutamide (Casodex). Disease remained stable in five (19%) for more than 6 months. Median progression-free survival was 12 weeks, which was “not that far off from what you get with [standard] chemotherapies. This was encouraging, and it led to multiple other trials looking at targeted therapies,” she said (Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Oct 1; 19[19]: 5505-12).

Dr. Traina led a phase II investigation of the prostate cancer AR antagonist enzalutamide (Xtandi) in 118 women with advanced AR-positive TNBC. Her team created an androgen-driven gene signature as a potential biomarker of response. Median progression-free survival was 32 weeks in the 56 women (47%) who were positive for the gene signature, but 9 weeks in those who were not. There were two complete responses and five partial responses with enzalutamide. Currently, “we are looking at using enzalutamide for patients with AR-positive TNBC in the early stage after failure of standard therapies,” she said.

French investigators recently reported a 6-month clinical benefit – including one complete response – in 7 (21%) of 34 women with locally advanced or metastatic TNBC who were treated with 1,000 mg daily of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor approved for prostate cancer (Ann Oncol. 2016 May;27[5]:812-8).

“We still have a ways to go” before AR treatment reaches the clinic for routine breast cancer treatment, “but there’s reason for hope,” Dr. Traina said.

Dr. Traina reported funding, honoraria, and steering committing payments from a number of companies working on or marketing TNBC AR drugs, including Pfizer, Astellas, Innocrin, AstraZeneca, Eisai, and Merck.

LAS VEGAS – Despite the early promise of antiandrogen therapy, it’s not time yet to routinely screen women with triple-negative breast cancer for androgen receptors, according to Tiffany A. Traina, MD, the head of research into the disease at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

There’s no standardized test for androgen receptors in breast cancer, so people “are doing different kinds of testing.” In the literature, “the range of AR positivity is anywhere from 12% to 79%, which reflects how we are all over the map in methodology; you might just as well throw a dart at the board. I would encourage screening in the context of the ongoing trials,” Dr. Traina said.

More than a decade ago, Memorial Sloan Kettering found a subset of TNBC that had ARs, which was peculiar because the tumors weren’t otherwise responsive to hormones. Androgen exposure increased growth, but the AR antagonist flutamide (Eulexin)blocked it. “It was thought provoking. There are a lot of drugs in the prostate cancer world” such as flutamide that shut down androgens, she said (Oncogene. 2006 Jun 29;25[28]:3994-4008).

Several have been tried, and investigations are ongoing. The work matters because TNBC is a particularly bad diagnosis. Blocking androgens seems to give some women a few more months of life.

Dr. Traina was the senior author in an early proof-of-concept study for AR blockade that involved 26 women with metastatic TNBC who had been through up to eight prior chemotherapy regimens. The women received 150 mg daily of the prostate cancer AR antagonist bicalutamide (Casodex). Disease remained stable in five (19%) for more than 6 months. Median progression-free survival was 12 weeks, which was “not that far off from what you get with [standard] chemotherapies. This was encouraging, and it led to multiple other trials looking at targeted therapies,” she said (Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Oct 1; 19[19]: 5505-12).

Dr. Traina led a phase II investigation of the prostate cancer AR antagonist enzalutamide (Xtandi) in 118 women with advanced AR-positive TNBC. Her team created an androgen-driven gene signature as a potential biomarker of response. Median progression-free survival was 32 weeks in the 56 women (47%) who were positive for the gene signature, but 9 weeks in those who were not. There were two complete responses and five partial responses with enzalutamide. Currently, “we are looking at using enzalutamide for patients with AR-positive TNBC in the early stage after failure of standard therapies,” she said.

French investigators recently reported a 6-month clinical benefit – including one complete response – in 7 (21%) of 34 women with locally advanced or metastatic TNBC who were treated with 1,000 mg daily of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor approved for prostate cancer (Ann Oncol. 2016 May;27[5]:812-8).

“We still have a ways to go” before AR treatment reaches the clinic for routine breast cancer treatment, “but there’s reason for hope,” Dr. Traina said.

Dr. Traina reported funding, honoraria, and steering committing payments from a number of companies working on or marketing TNBC AR drugs, including Pfizer, Astellas, Innocrin, AstraZeneca, Eisai, and Merck.

LAS VEGAS – Despite the early promise of antiandrogen therapy, it’s not time yet to routinely screen women with triple-negative breast cancer for androgen receptors, according to Tiffany A. Traina, MD, the head of research into the disease at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

There’s no standardized test for androgen receptors in breast cancer, so people “are doing different kinds of testing.” In the literature, “the range of AR positivity is anywhere from 12% to 79%, which reflects how we are all over the map in methodology; you might just as well throw a dart at the board. I would encourage screening in the context of the ongoing trials,” Dr. Traina said.

More than a decade ago, Memorial Sloan Kettering found a subset of TNBC that had ARs, which was peculiar because the tumors weren’t otherwise responsive to hormones. Androgen exposure increased growth, but the AR antagonist flutamide (Eulexin)blocked it. “It was thought provoking. There are a lot of drugs in the prostate cancer world” such as flutamide that shut down androgens, she said (Oncogene. 2006 Jun 29;25[28]:3994-4008).

Several have been tried, and investigations are ongoing. The work matters because TNBC is a particularly bad diagnosis. Blocking androgens seems to give some women a few more months of life.

Dr. Traina was the senior author in an early proof-of-concept study for AR blockade that involved 26 women with metastatic TNBC who had been through up to eight prior chemotherapy regimens. The women received 150 mg daily of the prostate cancer AR antagonist bicalutamide (Casodex). Disease remained stable in five (19%) for more than 6 months. Median progression-free survival was 12 weeks, which was “not that far off from what you get with [standard] chemotherapies. This was encouraging, and it led to multiple other trials looking at targeted therapies,” she said (Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Oct 1; 19[19]: 5505-12).

Dr. Traina led a phase II investigation of the prostate cancer AR antagonist enzalutamide (Xtandi) in 118 women with advanced AR-positive TNBC. Her team created an androgen-driven gene signature as a potential biomarker of response. Median progression-free survival was 32 weeks in the 56 women (47%) who were positive for the gene signature, but 9 weeks in those who were not. There were two complete responses and five partial responses with enzalutamide. Currently, “we are looking at using enzalutamide for patients with AR-positive TNBC in the early stage after failure of standard therapies,” she said.

French investigators recently reported a 6-month clinical benefit – including one complete response – in 7 (21%) of 34 women with locally advanced or metastatic TNBC who were treated with 1,000 mg daily of abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), an androgen biosynthesis inhibitor approved for prostate cancer (Ann Oncol. 2016 May;27[5]:812-8).

“We still have a ways to go” before AR treatment reaches the clinic for routine breast cancer treatment, “but there’s reason for hope,” Dr. Traina said.

Dr. Traina reported funding, honoraria, and steering committing payments from a number of companies working on or marketing TNBC AR drugs, including Pfizer, Astellas, Innocrin, AstraZeneca, Eisai, and Merck.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASBS 2017

MRD better measure of ALL remission than morphology

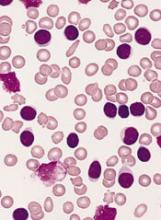

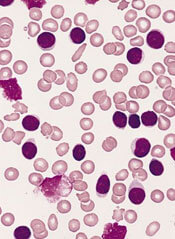

MONTREAL – In children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, minimal residual disease findings appear to be better at defining remission than morphology, Children’s Oncology Group investigators reported.

A study of outcomes of more than 9,000 children and young adults with B-lineage or T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) showed that patients who would be defined as being in remission by morphology but have minimal residual disease (MRD) of 5% or greater have survival outcomes similar to those of patients who do get a morphologic remission. Additionally, patients with discordant morphologic and MRD findings have significantly worse outcomes than do patients who were in morphologic remission and had concordant MRD findings, said Sumit Gupta, MD, PhD, from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“Given that, however, although MRD is used to measure the depth of remission either using flow cytometry or PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-based methods, remission itself continues to be defined by basic morphological assessment, whether that’s in clinical practice or clinical trials,” he added.

To see whether the practice of declaring remissions by morphology still makes sense, Dr. Gupta and his colleagues in the Children’s Oncology Group looked at outcomes for children and young adults with discordant ALL remissions as assessed by morphology, compared with MRD.

They looked at data on 9,350 patients from the ages of 1 to 31 years who were enrolled in one of three Children’s Oncology Group trials for patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Two of the trials (AALL0331 and AALL0232) were for patients with B-lineage ALL, and one (AALL0434) was for patients with T-lineage ALL.

They looked at morphologic responses as assessed by local centers, with M1 responses defined as less than 5% leukemic blasts (remission), M2 defined as 5% to less than 25% blasts, and M3 as 25% or more blasts. MRD was measured by flow cytometry at one of two central labs.

They found that discordant results (M1 morphology but MRD of 5% or greater) occurred in only 0.9% of patients with B-ALL, but in 6.9% of patients with T-ALL (P less than .0001).

In multivariate analysis, significant predictors of discordance in patients with B-ALL were patients age 10 years or older (P = .03), white blood cell counts of 50,000/mcL or greater (P = .005), and neutral or unfavorable cytogenetics vs. favorable (P less than .0001 for each).

Among patients with T-ALL, the only significant predictor of discordant results was the early T-precursor phenotype, with an odds ratio of 4.7 (P less than .0001).

Comparing event-free survival (EFS) between patients with concordant remission findings (M1/MRD less than 5%), they investigators saw that for patients with B-ALL, the 5-year EFS was 87%, compared with 59% for patients with discordant findings (M1/MRD 5% or greater, P less than .0001 vs. concordant remissions), and 39% for patients with concordant results showing a lack of remission (P = .009 vs. discordant findings).

Similarly, respective EFS rates for patients with T-ALL were 88%, 80% (P = .011) and 63% (not significant).

In a subanalysis of EFS by risk category, they found no differences according to concordance/discordance among patients with standard-risk B-ALL but a significant difference among patients with high-risk disease.

Attempting to determine what was driving the intermediate outcomes of patients with discordant findings, “we hypothesized that maybe it’s a difference in their actual MRD levels.” Specifically, they found that while both discordant and concordant not-in-remission patients had MRD levels of 5% or higher, the MRD levels were higher among those patients who were conclusively not in remission, Dr. Gupta said.

Finally, they found that for those patients with known overall survival data, concordant in remission patients with B-ALL had a 94% rate out to 12 years, compared with 73% for those with discordant results (P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in OS among patients with T-ALL, however.

“Should MRD assessment actually replace morphology in defining remission in subjects with ALL? I think these data strongly support that,” Dr. Gupta said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gupta reported having no conflicts of interest.

MONTREAL – In children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, minimal residual disease findings appear to be better at defining remission than morphology, Children’s Oncology Group investigators reported.

A study of outcomes of more than 9,000 children and young adults with B-lineage or T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) showed that patients who would be defined as being in remission by morphology but have minimal residual disease (MRD) of 5% or greater have survival outcomes similar to those of patients who do get a morphologic remission. Additionally, patients with discordant morphologic and MRD findings have significantly worse outcomes than do patients who were in morphologic remission and had concordant MRD findings, said Sumit Gupta, MD, PhD, from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“Given that, however, although MRD is used to measure the depth of remission either using flow cytometry or PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-based methods, remission itself continues to be defined by basic morphological assessment, whether that’s in clinical practice or clinical trials,” he added.

To see whether the practice of declaring remissions by morphology still makes sense, Dr. Gupta and his colleagues in the Children’s Oncology Group looked at outcomes for children and young adults with discordant ALL remissions as assessed by morphology, compared with MRD.

They looked at data on 9,350 patients from the ages of 1 to 31 years who were enrolled in one of three Children’s Oncology Group trials for patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Two of the trials (AALL0331 and AALL0232) were for patients with B-lineage ALL, and one (AALL0434) was for patients with T-lineage ALL.

They looked at morphologic responses as assessed by local centers, with M1 responses defined as less than 5% leukemic blasts (remission), M2 defined as 5% to less than 25% blasts, and M3 as 25% or more blasts. MRD was measured by flow cytometry at one of two central labs.

They found that discordant results (M1 morphology but MRD of 5% or greater) occurred in only 0.9% of patients with B-ALL, but in 6.9% of patients with T-ALL (P less than .0001).

In multivariate analysis, significant predictors of discordance in patients with B-ALL were patients age 10 years or older (P = .03), white blood cell counts of 50,000/mcL or greater (P = .005), and neutral or unfavorable cytogenetics vs. favorable (P less than .0001 for each).

Among patients with T-ALL, the only significant predictor of discordant results was the early T-precursor phenotype, with an odds ratio of 4.7 (P less than .0001).

Comparing event-free survival (EFS) between patients with concordant remission findings (M1/MRD less than 5%), they investigators saw that for patients with B-ALL, the 5-year EFS was 87%, compared with 59% for patients with discordant findings (M1/MRD 5% or greater, P less than .0001 vs. concordant remissions), and 39% for patients with concordant results showing a lack of remission (P = .009 vs. discordant findings).

Similarly, respective EFS rates for patients with T-ALL were 88%, 80% (P = .011) and 63% (not significant).

In a subanalysis of EFS by risk category, they found no differences according to concordance/discordance among patients with standard-risk B-ALL but a significant difference among patients with high-risk disease.

Attempting to determine what was driving the intermediate outcomes of patients with discordant findings, “we hypothesized that maybe it’s a difference in their actual MRD levels.” Specifically, they found that while both discordant and concordant not-in-remission patients had MRD levels of 5% or higher, the MRD levels were higher among those patients who were conclusively not in remission, Dr. Gupta said.

Finally, they found that for those patients with known overall survival data, concordant in remission patients with B-ALL had a 94% rate out to 12 years, compared with 73% for those with discordant results (P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in OS among patients with T-ALL, however.

“Should MRD assessment actually replace morphology in defining remission in subjects with ALL? I think these data strongly support that,” Dr. Gupta said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gupta reported having no conflicts of interest.

MONTREAL – In children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, minimal residual disease findings appear to be better at defining remission than morphology, Children’s Oncology Group investigators reported.

A study of outcomes of more than 9,000 children and young adults with B-lineage or T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) showed that patients who would be defined as being in remission by morphology but have minimal residual disease (MRD) of 5% or greater have survival outcomes similar to those of patients who do get a morphologic remission. Additionally, patients with discordant morphologic and MRD findings have significantly worse outcomes than do patients who were in morphologic remission and had concordant MRD findings, said Sumit Gupta, MD, PhD, from the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.

“Given that, however, although MRD is used to measure the depth of remission either using flow cytometry or PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-based methods, remission itself continues to be defined by basic morphological assessment, whether that’s in clinical practice or clinical trials,” he added.

To see whether the practice of declaring remissions by morphology still makes sense, Dr. Gupta and his colleagues in the Children’s Oncology Group looked at outcomes for children and young adults with discordant ALL remissions as assessed by morphology, compared with MRD.

They looked at data on 9,350 patients from the ages of 1 to 31 years who were enrolled in one of three Children’s Oncology Group trials for patients with newly diagnosed ALL. Two of the trials (AALL0331 and AALL0232) were for patients with B-lineage ALL, and one (AALL0434) was for patients with T-lineage ALL.

They looked at morphologic responses as assessed by local centers, with M1 responses defined as less than 5% leukemic blasts (remission), M2 defined as 5% to less than 25% blasts, and M3 as 25% or more blasts. MRD was measured by flow cytometry at one of two central labs.

They found that discordant results (M1 morphology but MRD of 5% or greater) occurred in only 0.9% of patients with B-ALL, but in 6.9% of patients with T-ALL (P less than .0001).

In multivariate analysis, significant predictors of discordance in patients with B-ALL were patients age 10 years or older (P = .03), white blood cell counts of 50,000/mcL or greater (P = .005), and neutral or unfavorable cytogenetics vs. favorable (P less than .0001 for each).

Among patients with T-ALL, the only significant predictor of discordant results was the early T-precursor phenotype, with an odds ratio of 4.7 (P less than .0001).

Comparing event-free survival (EFS) between patients with concordant remission findings (M1/MRD less than 5%), they investigators saw that for patients with B-ALL, the 5-year EFS was 87%, compared with 59% for patients with discordant findings (M1/MRD 5% or greater, P less than .0001 vs. concordant remissions), and 39% for patients with concordant results showing a lack of remission (P = .009 vs. discordant findings).

Similarly, respective EFS rates for patients with T-ALL were 88%, 80% (P = .011) and 63% (not significant).

In a subanalysis of EFS by risk category, they found no differences according to concordance/discordance among patients with standard-risk B-ALL but a significant difference among patients with high-risk disease.

Attempting to determine what was driving the intermediate outcomes of patients with discordant findings, “we hypothesized that maybe it’s a difference in their actual MRD levels.” Specifically, they found that while both discordant and concordant not-in-remission patients had MRD levels of 5% or higher, the MRD levels were higher among those patients who were conclusively not in remission, Dr. Gupta said.

Finally, they found that for those patients with known overall survival data, concordant in remission patients with B-ALL had a 94% rate out to 12 years, compared with 73% for those with discordant results (P less than .0001). There was no significant difference in OS among patients with T-ALL, however.

“Should MRD assessment actually replace morphology in defining remission in subjects with ALL? I think these data strongly support that,” Dr. Gupta said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gupta reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM ASPHO 2017

Key clinical point: Patients with ALL determined to be in remission by both morphology and minimal residual disease had better outcomes than did those with discordant results.

Major finding: Event-free survival of B-ALL was 87% for patients with concordant remission findings vs. 59% for patients with discordant findings and 39% for concordant not-in-remission findings.

Data source: Retrospective review of data on 9,350 children and young adults with ALL.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Gupta reported having no conflicts of interest.

Two new biomarkers show breast cancer validity

BRUSSELS – A pair of breast cancer biomarkers look promising for making better prognosis assessments of selected patients, but acceptance of both into practice will need further documentation of their clinical utility, declared a senior breast cancer oncologist who served as discussant for the studies.

One of the markers is high intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor density, a flag of poor prognosis when heterogeneity is high. The second marker is the phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT) 3, which appeared to link with good prognosis in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer.

The data on intratumor estrogen-receptor heterogeneity came from specimens collected from the low-risk breast cancer patients enrolled in the Stockholm Adjuvant Tamoxifen trial during 1976-1990 (Acta Oncol. 2007 July 8;46[2]:133-45). Enrolled patients had lymph node–negative disease and primary tumors smaller than 30 mm. During the trial, researchers preserved formalin-fixed tumor specimens in paraffin from 778 patients, which formed the basis for the current study, explained Linda S. Lindström, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Slides from the specimens were restained for their estrogen receptor content in 2014 and assessed by two independent breast cancer pathologists. They scored the heterogeneity of estrogen receptor distribution as high, medium, or low, and Dr. Lindström and her associates calculated a hazard ratio for 25-year patient survival when they compared 593 specimens with high or low receptor heterogeneity. They adjusted the hazard ratios for several baseline variables including age, year of breast cancer diagnosis, HER2 status, Ki67 status, tumor grade, tumor size, randomization to tamoxifen or placebo treatment, and other factors.

“Routine clinical assessment of intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor may identify patients at high long-term risk for fatal breast cancer that may potentially change clinical management, especially for patients with luminal A subtype tumors,” Dr. Lindström said.“I’d like to see the C statistic; will the prognostic model improve significantly with this added?” Dr. Linn wondered. “We need at least two more independent validations.”

The second biomarker study used two separate analyses of pSTAT3 expression. The first involved specimens collected from 3,074 patients with luminal breast cancer. Analysis of pSTAT3 gene signature expression showed that, the higher the expression levels were, associated with better relapse-free survival during follow-up out to as long as 8 years, reported Amir Sonnenblick, MD, an oncologist at the Sharret Institute of Oncology of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

Univariate analysis showed that binary pSTAT3 expression (positive or negative) significantly correlated with 10-year overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 0.66 (P = .04) for patients with positive expression, compared with those with no pSTAT3 expression, Dr. Sonnenblick said.

“pSTAT3 is associated with improved outcome in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. Future trials should take pSTAT3 status into account,” he concluded.

Dr. Linn cautioned that pSTAT3 expression should not be used to identify patients who can forgo chemotherapy, as the gene signature expression analysis showed that, even among patients with high pSTAT3 expression, long-term survival was still less than 90%.

Dr. Lindström and Dr. Sonnenblick had no disclosures. Dr. Linn has been an adviser to AstraZeneca, Cergentis, IBM Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Phillips Health, Roche, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – A pair of breast cancer biomarkers look promising for making better prognosis assessments of selected patients, but acceptance of both into practice will need further documentation of their clinical utility, declared a senior breast cancer oncologist who served as discussant for the studies.

One of the markers is high intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor density, a flag of poor prognosis when heterogeneity is high. The second marker is the phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT) 3, which appeared to link with good prognosis in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer.

The data on intratumor estrogen-receptor heterogeneity came from specimens collected from the low-risk breast cancer patients enrolled in the Stockholm Adjuvant Tamoxifen trial during 1976-1990 (Acta Oncol. 2007 July 8;46[2]:133-45). Enrolled patients had lymph node–negative disease and primary tumors smaller than 30 mm. During the trial, researchers preserved formalin-fixed tumor specimens in paraffin from 778 patients, which formed the basis for the current study, explained Linda S. Lindström, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Slides from the specimens were restained for their estrogen receptor content in 2014 and assessed by two independent breast cancer pathologists. They scored the heterogeneity of estrogen receptor distribution as high, medium, or low, and Dr. Lindström and her associates calculated a hazard ratio for 25-year patient survival when they compared 593 specimens with high or low receptor heterogeneity. They adjusted the hazard ratios for several baseline variables including age, year of breast cancer diagnosis, HER2 status, Ki67 status, tumor grade, tumor size, randomization to tamoxifen or placebo treatment, and other factors.

“Routine clinical assessment of intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor may identify patients at high long-term risk for fatal breast cancer that may potentially change clinical management, especially for patients with luminal A subtype tumors,” Dr. Lindström said.“I’d like to see the C statistic; will the prognostic model improve significantly with this added?” Dr. Linn wondered. “We need at least two more independent validations.”

The second biomarker study used two separate analyses of pSTAT3 expression. The first involved specimens collected from 3,074 patients with luminal breast cancer. Analysis of pSTAT3 gene signature expression showed that, the higher the expression levels were, associated with better relapse-free survival during follow-up out to as long as 8 years, reported Amir Sonnenblick, MD, an oncologist at the Sharret Institute of Oncology of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

Univariate analysis showed that binary pSTAT3 expression (positive or negative) significantly correlated with 10-year overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 0.66 (P = .04) for patients with positive expression, compared with those with no pSTAT3 expression, Dr. Sonnenblick said.

“pSTAT3 is associated with improved outcome in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. Future trials should take pSTAT3 status into account,” he concluded.

Dr. Linn cautioned that pSTAT3 expression should not be used to identify patients who can forgo chemotherapy, as the gene signature expression analysis showed that, even among patients with high pSTAT3 expression, long-term survival was still less than 90%.

Dr. Lindström and Dr. Sonnenblick had no disclosures. Dr. Linn has been an adviser to AstraZeneca, Cergentis, IBM Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Phillips Health, Roche, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BRUSSELS – A pair of breast cancer biomarkers look promising for making better prognosis assessments of selected patients, but acceptance of both into practice will need further documentation of their clinical utility, declared a senior breast cancer oncologist who served as discussant for the studies.

One of the markers is high intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor density, a flag of poor prognosis when heterogeneity is high. The second marker is the phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription (pSTAT) 3, which appeared to link with good prognosis in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer.

The data on intratumor estrogen-receptor heterogeneity came from specimens collected from the low-risk breast cancer patients enrolled in the Stockholm Adjuvant Tamoxifen trial during 1976-1990 (Acta Oncol. 2007 July 8;46[2]:133-45). Enrolled patients had lymph node–negative disease and primary tumors smaller than 30 mm. During the trial, researchers preserved formalin-fixed tumor specimens in paraffin from 778 patients, which formed the basis for the current study, explained Linda S. Lindström, PhD, a cancer epidemiologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. Slides from the specimens were restained for their estrogen receptor content in 2014 and assessed by two independent breast cancer pathologists. They scored the heterogeneity of estrogen receptor distribution as high, medium, or low, and Dr. Lindström and her associates calculated a hazard ratio for 25-year patient survival when they compared 593 specimens with high or low receptor heterogeneity. They adjusted the hazard ratios for several baseline variables including age, year of breast cancer diagnosis, HER2 status, Ki67 status, tumor grade, tumor size, randomization to tamoxifen or placebo treatment, and other factors.

“Routine clinical assessment of intratumor heterogeneity of estrogen receptor may identify patients at high long-term risk for fatal breast cancer that may potentially change clinical management, especially for patients with luminal A subtype tumors,” Dr. Lindström said.“I’d like to see the C statistic; will the prognostic model improve significantly with this added?” Dr. Linn wondered. “We need at least two more independent validations.”

The second biomarker study used two separate analyses of pSTAT3 expression. The first involved specimens collected from 3,074 patients with luminal breast cancer. Analysis of pSTAT3 gene signature expression showed that, the higher the expression levels were, associated with better relapse-free survival during follow-up out to as long as 8 years, reported Amir Sonnenblick, MD, an oncologist at the Sharret Institute of Oncology of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center in Jerusalem.

Univariate analysis showed that binary pSTAT3 expression (positive or negative) significantly correlated with 10-year overall survival, with a hazard ratio of 0.66 (P = .04) for patients with positive expression, compared with those with no pSTAT3 expression, Dr. Sonnenblick said.

“pSTAT3 is associated with improved outcome in estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer. Future trials should take pSTAT3 status into account,” he concluded.

Dr. Linn cautioned that pSTAT3 expression should not be used to identify patients who can forgo chemotherapy, as the gene signature expression analysis showed that, even among patients with high pSTAT3 expression, long-term survival was still less than 90%.

Dr. Lindström and Dr. Sonnenblick had no disclosures. Dr. Linn has been an adviser to AstraZeneca, Cergentis, IBM Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Phillips Health, Roche, and Sanofi.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT IMPAKT 2017 BREAST CANCER CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: High estrogen-receptor heterogeneity linked with worse outcomes; pSTAT3 expression linked with better outcomes.

Data source: A total of 593 patients enrolled in the Stockholm Adjuvant Tamoxifen trial, and 610 patients enrolled in the Breast International Group 2-98 trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Lindström and Dr. Sonnenblick had no disclosures. Dr. Linn has been an advisor to AstraZeneca, Cergentis, IBM Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Phillips Health, Roche, and Sanofi.

Endoscopic weight loss surgery cuts costs, side effects

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

FROM DDW

Key clinical point: Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a viable option for patients seeking weight loss but wishing to avoid major surgery.

Major finding: After 1 year, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 9% of laparoscopic band placement patients.

Data source: A randomized trial of 278 obese adults who underwent one of three weight loss procedures.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

2017 Update on cervical disease

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

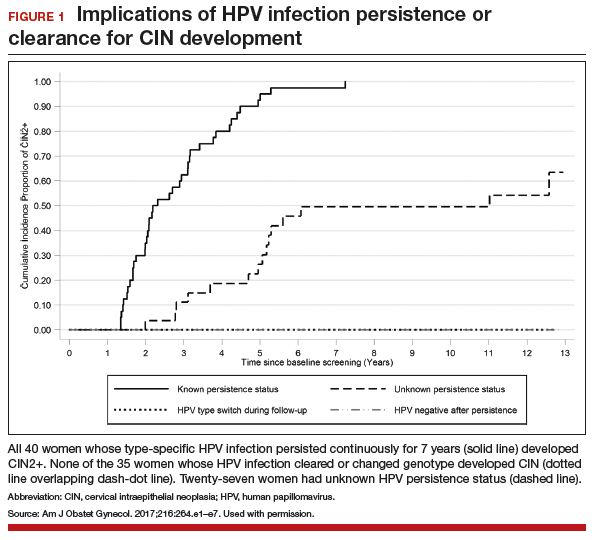

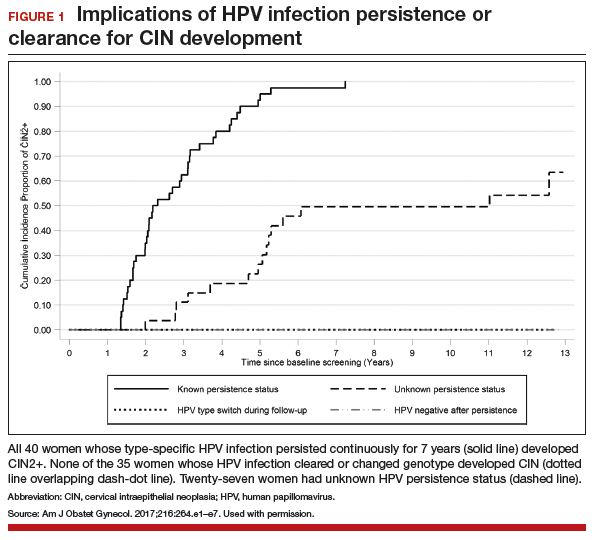

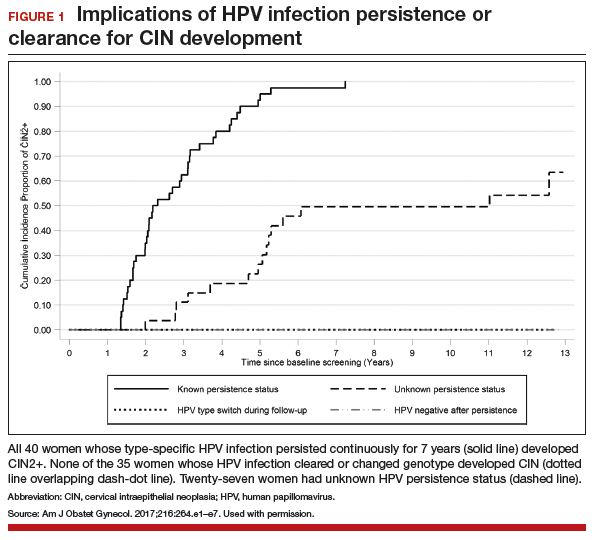

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

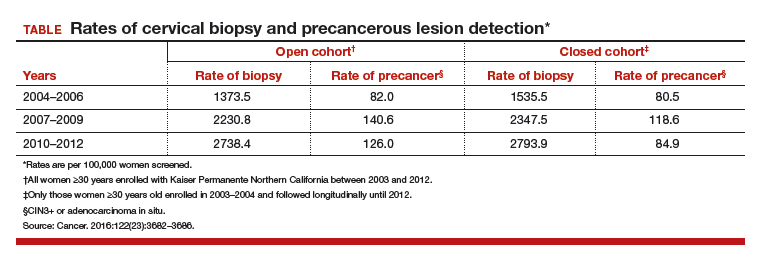

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

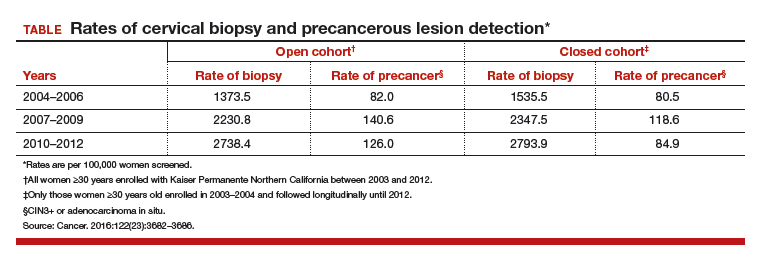

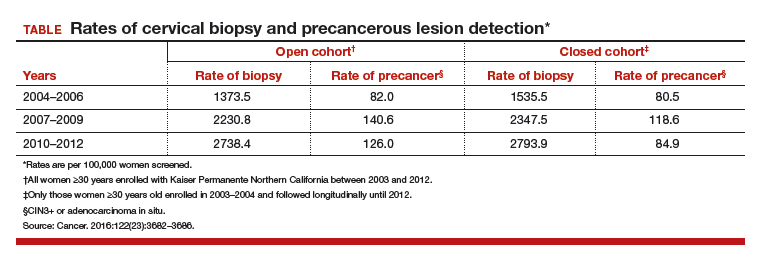

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

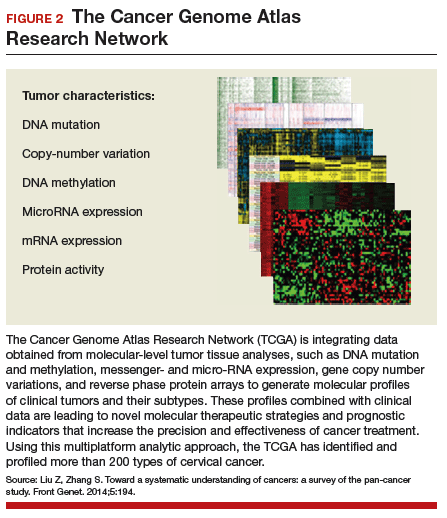

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.

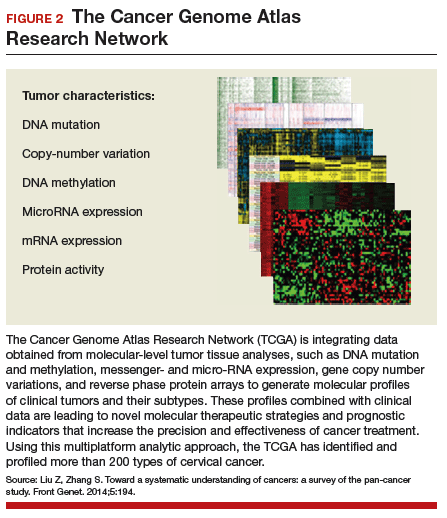

The integration of data from multiple layers of analysis (FIGURE 2) is helping investigators identify variations in cancers. DNA methylation, for instance, is a means by which cells control gene expression. An analysis of this process in cervical tumor tissue has revealed additional cancer subgroups in which messenger RNA increases the transition of epithelial cells to invasive mesenchymal cells. Targeting that process in these subgroups would likely enhance the effectiveness of novel small-molecule inhibitors and some standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542.

- Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, DeFrancesco M, Thomas Cox J, Huh W. Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):311–315.

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.

The integration of data from multiple layers of analysis (FIGURE 2) is helping investigators identify variations in cancers. DNA methylation, for instance, is a means by which cells control gene expression. An analysis of this process in cervical tumor tissue has revealed additional cancer subgroups in which messenger RNA increases the transition of epithelial cells to invasive mesenchymal cells. Targeting that process in these subgroups would likely enhance the effectiveness of novel small-molecule inhibitors and some standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.