User login

Providers buck lipid recommendations in high-risk diabetes

SAN DIEGO – In the 3 months before their atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, 40% of high-risk patients with diabetes received no prescription for lipid-lowering therapy, researchers reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Underprescribing of high-intensity statins was also “particularly apparent for patients with diabetes mellitus alone, although rates improved somewhat over follow-up,” Sarah S. Cohen, PhD, of EpidStat Institute in Ann Arbor, Mich., said in a late-breaking poster. The findings highlight the need to educate providers and patients on the importance of addressing cardiovascular risk factors and disease in the diabetes setting, she wrote with her associates from the Mayo Clinic and Amgen.

Hypertension and dyslipidemia are classic companions of type 2 diabetes and “clear risk factors” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), according to 2017 care guidelines from the American Diabetes Association.

“Diabetes itself confers independent risk,” the guidelines add. To characterize real-world use of lipid-lowering therapies in patients with diabetes, ASCVD, or both conditions, Dr. Cohen and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from more than 7,400 adults in Minnesota with new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus or ASCVD, or incident ASCVD and existing diabetes between 2005 and 2012. During this period, about 4,500 patients were diagnosed with diabetes and another 570 patients with an existing diagnosis of diabetes were diagnosed with ASCVD based on incident myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, or revascularization. An additional 2,300 patients had ASCVD alone.

Patients with existing diabetes and incident ASCVD tended to be in their 70s, two-thirds had used tobacco, 31% were overweight, and 54% were obese, the investigators found. Nonetheless, 40% of patients received no lipid-lowering therapy in the 3 months before the ASCVD event and 90% received no high-intensity statins. Three months after the event, 75% of patients were on lipid-lowering therapy and 64% were on moderate- or high-intensity statins. Patients with incident diabetes alone tended to be in their late 50s, about 60% had used tobacco, and two-thirds were obese. Only 34%, however, were prescribed moderate or high-intensity statins within 3 months after their diabetes diagnosis, and this proportion rose to just 46% at 2 years.

Diabetes is known to boost the risk of cardiovascular disease, but incident diabetes seldom triggered a prescription for lipid-lowering therapy in this cohort, the researchers concluded. Incident ASCVD was much more likely to elicit a prescription, but comorbid diabetes did not further improve the chances of receiving guideline-recommended therapy.

The ADA recommends screening for and treating modifiable CVD risk factors even in the prediabetes setting. For patients with clinical diabetes, providers should evaluate history of dyslipidemia, obtain a fasting lipid profile, and recommend lifestyle changes to address glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals, ADA guidelines state. In addition, comorbid diabetes and ASCVD merit high-intensity statin therapy, and diabetic patients with additional risk factors for CVD merit consideration of moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy, according to the recommendations.

The researchers lacked data on prescription fill rates, so they might have overestimated the proportion of patients taking lipid-lowering therapies, they noted. They also had no data on reasons for not prescribing lipid-lowering therapies.

Amgen and the National Institute on Aging provided funding. Dr. Cohen disclosed research funding from Amgen, which makes evolocumab, a lipid-lowering drug. She had no other conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – In the 3 months before their atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, 40% of high-risk patients with diabetes received no prescription for lipid-lowering therapy, researchers reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Underprescribing of high-intensity statins was also “particularly apparent for patients with diabetes mellitus alone, although rates improved somewhat over follow-up,” Sarah S. Cohen, PhD, of EpidStat Institute in Ann Arbor, Mich., said in a late-breaking poster. The findings highlight the need to educate providers and patients on the importance of addressing cardiovascular risk factors and disease in the diabetes setting, she wrote with her associates from the Mayo Clinic and Amgen.

Hypertension and dyslipidemia are classic companions of type 2 diabetes and “clear risk factors” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), according to 2017 care guidelines from the American Diabetes Association.

“Diabetes itself confers independent risk,” the guidelines add. To characterize real-world use of lipid-lowering therapies in patients with diabetes, ASCVD, or both conditions, Dr. Cohen and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from more than 7,400 adults in Minnesota with new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus or ASCVD, or incident ASCVD and existing diabetes between 2005 and 2012. During this period, about 4,500 patients were diagnosed with diabetes and another 570 patients with an existing diagnosis of diabetes were diagnosed with ASCVD based on incident myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, or revascularization. An additional 2,300 patients had ASCVD alone.

Patients with existing diabetes and incident ASCVD tended to be in their 70s, two-thirds had used tobacco, 31% were overweight, and 54% were obese, the investigators found. Nonetheless, 40% of patients received no lipid-lowering therapy in the 3 months before the ASCVD event and 90% received no high-intensity statins. Three months after the event, 75% of patients were on lipid-lowering therapy and 64% were on moderate- or high-intensity statins. Patients with incident diabetes alone tended to be in their late 50s, about 60% had used tobacco, and two-thirds were obese. Only 34%, however, were prescribed moderate or high-intensity statins within 3 months after their diabetes diagnosis, and this proportion rose to just 46% at 2 years.

Diabetes is known to boost the risk of cardiovascular disease, but incident diabetes seldom triggered a prescription for lipid-lowering therapy in this cohort, the researchers concluded. Incident ASCVD was much more likely to elicit a prescription, but comorbid diabetes did not further improve the chances of receiving guideline-recommended therapy.

The ADA recommends screening for and treating modifiable CVD risk factors even in the prediabetes setting. For patients with clinical diabetes, providers should evaluate history of dyslipidemia, obtain a fasting lipid profile, and recommend lifestyle changes to address glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals, ADA guidelines state. In addition, comorbid diabetes and ASCVD merit high-intensity statin therapy, and diabetic patients with additional risk factors for CVD merit consideration of moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy, according to the recommendations.

The researchers lacked data on prescription fill rates, so they might have overestimated the proportion of patients taking lipid-lowering therapies, they noted. They also had no data on reasons for not prescribing lipid-lowering therapies.

Amgen and the National Institute on Aging provided funding. Dr. Cohen disclosed research funding from Amgen, which makes evolocumab, a lipid-lowering drug. She had no other conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – In the 3 months before their atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, 40% of high-risk patients with diabetes received no prescription for lipid-lowering therapy, researchers reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Underprescribing of high-intensity statins was also “particularly apparent for patients with diabetes mellitus alone, although rates improved somewhat over follow-up,” Sarah S. Cohen, PhD, of EpidStat Institute in Ann Arbor, Mich., said in a late-breaking poster. The findings highlight the need to educate providers and patients on the importance of addressing cardiovascular risk factors and disease in the diabetes setting, she wrote with her associates from the Mayo Clinic and Amgen.

Hypertension and dyslipidemia are classic companions of type 2 diabetes and “clear risk factors” for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), according to 2017 care guidelines from the American Diabetes Association.

“Diabetes itself confers independent risk,” the guidelines add. To characterize real-world use of lipid-lowering therapies in patients with diabetes, ASCVD, or both conditions, Dr. Cohen and her associates analyzed electronic medical records from more than 7,400 adults in Minnesota with new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus or ASCVD, or incident ASCVD and existing diabetes between 2005 and 2012. During this period, about 4,500 patients were diagnosed with diabetes and another 570 patients with an existing diagnosis of diabetes were diagnosed with ASCVD based on incident myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, or revascularization. An additional 2,300 patients had ASCVD alone.

Patients with existing diabetes and incident ASCVD tended to be in their 70s, two-thirds had used tobacco, 31% were overweight, and 54% were obese, the investigators found. Nonetheless, 40% of patients received no lipid-lowering therapy in the 3 months before the ASCVD event and 90% received no high-intensity statins. Three months after the event, 75% of patients were on lipid-lowering therapy and 64% were on moderate- or high-intensity statins. Patients with incident diabetes alone tended to be in their late 50s, about 60% had used tobacco, and two-thirds were obese. Only 34%, however, were prescribed moderate or high-intensity statins within 3 months after their diabetes diagnosis, and this proportion rose to just 46% at 2 years.

Diabetes is known to boost the risk of cardiovascular disease, but incident diabetes seldom triggered a prescription for lipid-lowering therapy in this cohort, the researchers concluded. Incident ASCVD was much more likely to elicit a prescription, but comorbid diabetes did not further improve the chances of receiving guideline-recommended therapy.

The ADA recommends screening for and treating modifiable CVD risk factors even in the prediabetes setting. For patients with clinical diabetes, providers should evaluate history of dyslipidemia, obtain a fasting lipid profile, and recommend lifestyle changes to address glycemic, blood pressure, and lipid goals, ADA guidelines state. In addition, comorbid diabetes and ASCVD merit high-intensity statin therapy, and diabetic patients with additional risk factors for CVD merit consideration of moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy, according to the recommendations.

The researchers lacked data on prescription fill rates, so they might have overestimated the proportion of patients taking lipid-lowering therapies, they noted. They also had no data on reasons for not prescribing lipid-lowering therapies.

Amgen and the National Institute on Aging provided funding. Dr. Cohen disclosed research funding from Amgen, which makes evolocumab, a lipid-lowering drug. She had no other conflicts of interest.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Underprescribing of lipid-lowering therapies persists despite guidelines on their importance in patients with diabetes.

Major finding: About 40% of high-risk patients with diabetes were not prescribed lipid-lowering therapy in the 3 months before an atherosclerotic cardiovascular event.

Data source: Analyses of electronic medical records from 7,414 patients diagnosed with diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, or both between 2005 and 2012.

Disclosures: Amgen and the National Institute on Aging provided funding. Dr. Cohen disclosed research funding from Amgen, which makes evolocumab, a lipid-lowering drug. She had no other conflicts of interest.

Shulkin Outlines Veterans Choice Program 2.0

In testimony before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, VA Secretary David J. Shulkin, MD, outlined a vision for a revamped Veterans Choice Program that would allow veterans to access an integrated network of private health care providers for services not currently available at the VA. “We believe redesigning community care will result in a strong VA that can meet the special needs of our veteran population,” Shulkin told the committee. “Where VA excels, we want to make sure that the tools exist to continue performing well in those areas…. We need to move from a system where eligibility for community care is based on wait times and geography to one focused on clinical need and quality of care.”

During the hearing, Dr. Shulkin laid out the basic elements of the new Veterans Choice Program. The proposed changes include the following:

- Shifting from determining eligibility for community care based on wait times and geography to clinical need and quality of care;

- Streamlining process for veterans to access urgent care when they need it;

- Creating what VA is calling a "high performing integrated network,” which would include VA; other federal health care providers, such as military treatment facilities and IHS; academic affiliates; and community providers;

- Coordinating care across all providers; and

- Adopting recognized industry standards for quality, patient satisfaction, payment models, health care outcomes, and exchange of health information.

Over the past year, major veterans service organizations (VSOs), VA officials, the Commission on Care, and members of the House and Senate have worked together to develop the newly introduced Veterans Choice program. The major stakeholders came together at the hearing to “support the concept of developing an integrated network that combines the strength of the VA health care system with the best of community care to offer seamless access for enrolled veterans,” explained Adrian Atizado, the deputy national legislative director at Disabled American Veterans (DAV) in his prepared remarks.

The joint effort was in part a response to calls from some VA critics to provide veterans with unlimited choice to outside providers or to fully privatize veteran care.

In the hearing, Committee Chairman Johnny Isakson (R-GA) suggested that he would be willing to work with the VA on the changes to the Veterans Choice Program and was largely in support of the effort. “We need to see to it that the VA…is unleashed to provide the highest quality service that it can and make the decisions that it needs to make on the ground at the time we need to make them,” he reported in a release following the hearing. “We need to give them the funding, commitment and resources to be able to do that.”

At the hearing, VSOs praised the VA for its efforts to improve the Veterans Choice Program but still expressed frustration with problems that continue to dog the program. “The VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars] has also heard from veterans that the breakdown in communication between VA, contractors and Choice providers often delays their care because their Choice doctors do not receive authorization to provide needed treatments,” reported Carlos Fuentes, VFW director national legislative services. “What is concerning is that veterans are left to piece together the entire story or else they do not.”

“While many veterans initially clamored for ‘more Choice’ as a solution to scheduling problems within the VA healthcare system, once this program was implemented, most have not found it to be a solution,” noted Jeff Steele, assistant director national legislative division of The American Legion. “Instead, they have found it to create as many problems as it solves.…What we have found over the past decade, directly interacting with veterans, is that many of the problems veterans encountered with scheduling appointments in VA are mirrored in the civilian community outside VA.

In testimony before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, VA Secretary David J. Shulkin, MD, outlined a vision for a revamped Veterans Choice Program that would allow veterans to access an integrated network of private health care providers for services not currently available at the VA. “We believe redesigning community care will result in a strong VA that can meet the special needs of our veteran population,” Shulkin told the committee. “Where VA excels, we want to make sure that the tools exist to continue performing well in those areas…. We need to move from a system where eligibility for community care is based on wait times and geography to one focused on clinical need and quality of care.”

During the hearing, Dr. Shulkin laid out the basic elements of the new Veterans Choice Program. The proposed changes include the following:

- Shifting from determining eligibility for community care based on wait times and geography to clinical need and quality of care;

- Streamlining process for veterans to access urgent care when they need it;

- Creating what VA is calling a "high performing integrated network,” which would include VA; other federal health care providers, such as military treatment facilities and IHS; academic affiliates; and community providers;

- Coordinating care across all providers; and

- Adopting recognized industry standards for quality, patient satisfaction, payment models, health care outcomes, and exchange of health information.

Over the past year, major veterans service organizations (VSOs), VA officials, the Commission on Care, and members of the House and Senate have worked together to develop the newly introduced Veterans Choice program. The major stakeholders came together at the hearing to “support the concept of developing an integrated network that combines the strength of the VA health care system with the best of community care to offer seamless access for enrolled veterans,” explained Adrian Atizado, the deputy national legislative director at Disabled American Veterans (DAV) in his prepared remarks.

The joint effort was in part a response to calls from some VA critics to provide veterans with unlimited choice to outside providers or to fully privatize veteran care.

In the hearing, Committee Chairman Johnny Isakson (R-GA) suggested that he would be willing to work with the VA on the changes to the Veterans Choice Program and was largely in support of the effort. “We need to see to it that the VA…is unleashed to provide the highest quality service that it can and make the decisions that it needs to make on the ground at the time we need to make them,” he reported in a release following the hearing. “We need to give them the funding, commitment and resources to be able to do that.”

At the hearing, VSOs praised the VA for its efforts to improve the Veterans Choice Program but still expressed frustration with problems that continue to dog the program. “The VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars] has also heard from veterans that the breakdown in communication between VA, contractors and Choice providers often delays their care because their Choice doctors do not receive authorization to provide needed treatments,” reported Carlos Fuentes, VFW director national legislative services. “What is concerning is that veterans are left to piece together the entire story or else they do not.”

“While many veterans initially clamored for ‘more Choice’ as a solution to scheduling problems within the VA healthcare system, once this program was implemented, most have not found it to be a solution,” noted Jeff Steele, assistant director national legislative division of The American Legion. “Instead, they have found it to create as many problems as it solves.…What we have found over the past decade, directly interacting with veterans, is that many of the problems veterans encountered with scheduling appointments in VA are mirrored in the civilian community outside VA.

In testimony before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee, VA Secretary David J. Shulkin, MD, outlined a vision for a revamped Veterans Choice Program that would allow veterans to access an integrated network of private health care providers for services not currently available at the VA. “We believe redesigning community care will result in a strong VA that can meet the special needs of our veteran population,” Shulkin told the committee. “Where VA excels, we want to make sure that the tools exist to continue performing well in those areas…. We need to move from a system where eligibility for community care is based on wait times and geography to one focused on clinical need and quality of care.”

During the hearing, Dr. Shulkin laid out the basic elements of the new Veterans Choice Program. The proposed changes include the following:

- Shifting from determining eligibility for community care based on wait times and geography to clinical need and quality of care;

- Streamlining process for veterans to access urgent care when they need it;

- Creating what VA is calling a "high performing integrated network,” which would include VA; other federal health care providers, such as military treatment facilities and IHS; academic affiliates; and community providers;

- Coordinating care across all providers; and

- Adopting recognized industry standards for quality, patient satisfaction, payment models, health care outcomes, and exchange of health information.

Over the past year, major veterans service organizations (VSOs), VA officials, the Commission on Care, and members of the House and Senate have worked together to develop the newly introduced Veterans Choice program. The major stakeholders came together at the hearing to “support the concept of developing an integrated network that combines the strength of the VA health care system with the best of community care to offer seamless access for enrolled veterans,” explained Adrian Atizado, the deputy national legislative director at Disabled American Veterans (DAV) in his prepared remarks.

The joint effort was in part a response to calls from some VA critics to provide veterans with unlimited choice to outside providers or to fully privatize veteran care.

In the hearing, Committee Chairman Johnny Isakson (R-GA) suggested that he would be willing to work with the VA on the changes to the Veterans Choice Program and was largely in support of the effort. “We need to see to it that the VA…is unleashed to provide the highest quality service that it can and make the decisions that it needs to make on the ground at the time we need to make them,” he reported in a release following the hearing. “We need to give them the funding, commitment and resources to be able to do that.”

At the hearing, VSOs praised the VA for its efforts to improve the Veterans Choice Program but still expressed frustration with problems that continue to dog the program. “The VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars] has also heard from veterans that the breakdown in communication between VA, contractors and Choice providers often delays their care because their Choice doctors do not receive authorization to provide needed treatments,” reported Carlos Fuentes, VFW director national legislative services. “What is concerning is that veterans are left to piece together the entire story or else they do not.”

“While many veterans initially clamored for ‘more Choice’ as a solution to scheduling problems within the VA healthcare system, once this program was implemented, most have not found it to be a solution,” noted Jeff Steele, assistant director national legislative division of The American Legion. “Instead, they have found it to create as many problems as it solves.…What we have found over the past decade, directly interacting with veterans, is that many of the problems veterans encountered with scheduling appointments in VA are mirrored in the civilian community outside VA.

Relieving PTSD Symptoms May Cut Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke

Women with severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms have a nearly 70% increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a study by researchers from Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Columbia University in New York, and University of California in San Francisco.

The researchers analyzed data from 49,859 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Over 20 years, there were 552 confirmed cases of myocardial infarction or stroke.

Women with 6 to 7 symptoms of trauma and PTSD had the highest risk. Women with trauma but no PTSD symptoms had a 30% higher risk. When women who said illness was their worst trauma were excluded, the risk of CVD doubled among those with trauma and severe PTSD symptoms and increased by 88% in women with trauma and moderate PTSD symptoms.

Strikingly, the researchers also found that when the PTSD symptoms declined so did the CVD risk. The researchers note that CVD risk due to other well-known risk factors, such as smoking, increases with exposure duration declines once the risk factor is eliminated. In this study, for every 5 additional years PTSD symptoms lasted, the odds of CVD were 9% higher.

A “more nuanced understanding” of the role of health behaviors could add insight into how PTSD influences the risk of CVD, the researchers say. They point to studies that have found a link between PTSD and cardiotoxic behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and diet. Physiologic alterations that occur with PTSD symptoms also may play an important role, they suggest, such as changes in neuropeptide Y in response to stress, which might contribute to metabolic syndrome.

Citing “particularly intriguing” findings from a study that found symptoms eventually remitted in 44% of individuals with PTSD, the researchers say providing treatment shortly after PTSD symptoms begin could limit the risk of CVD and, potentially, other disease-related risk.

Source:

Gilsanz P, Winning A, Koenen KC, et al. Psychol Med. 2017;47(8):1370-1378.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003378.

Women with severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms have a nearly 70% increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a study by researchers from Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Columbia University in New York, and University of California in San Francisco.

The researchers analyzed data from 49,859 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Over 20 years, there were 552 confirmed cases of myocardial infarction or stroke.

Women with 6 to 7 symptoms of trauma and PTSD had the highest risk. Women with trauma but no PTSD symptoms had a 30% higher risk. When women who said illness was their worst trauma were excluded, the risk of CVD doubled among those with trauma and severe PTSD symptoms and increased by 88% in women with trauma and moderate PTSD symptoms.

Strikingly, the researchers also found that when the PTSD symptoms declined so did the CVD risk. The researchers note that CVD risk due to other well-known risk factors, such as smoking, increases with exposure duration declines once the risk factor is eliminated. In this study, for every 5 additional years PTSD symptoms lasted, the odds of CVD were 9% higher.

A “more nuanced understanding” of the role of health behaviors could add insight into how PTSD influences the risk of CVD, the researchers say. They point to studies that have found a link between PTSD and cardiotoxic behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and diet. Physiologic alterations that occur with PTSD symptoms also may play an important role, they suggest, such as changes in neuropeptide Y in response to stress, which might contribute to metabolic syndrome.

Citing “particularly intriguing” findings from a study that found symptoms eventually remitted in 44% of individuals with PTSD, the researchers say providing treatment shortly after PTSD symptoms begin could limit the risk of CVD and, potentially, other disease-related risk.

Source:

Gilsanz P, Winning A, Koenen KC, et al. Psychol Med. 2017;47(8):1370-1378.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003378.

Women with severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms have a nearly 70% increase in the incidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a study by researchers from Harvard and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Columbia University in New York, and University of California in San Francisco.

The researchers analyzed data from 49,859 women in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Over 20 years, there were 552 confirmed cases of myocardial infarction or stroke.

Women with 6 to 7 symptoms of trauma and PTSD had the highest risk. Women with trauma but no PTSD symptoms had a 30% higher risk. When women who said illness was their worst trauma were excluded, the risk of CVD doubled among those with trauma and severe PTSD symptoms and increased by 88% in women with trauma and moderate PTSD symptoms.

Strikingly, the researchers also found that when the PTSD symptoms declined so did the CVD risk. The researchers note that CVD risk due to other well-known risk factors, such as smoking, increases with exposure duration declines once the risk factor is eliminated. In this study, for every 5 additional years PTSD symptoms lasted, the odds of CVD were 9% higher.

A “more nuanced understanding” of the role of health behaviors could add insight into how PTSD influences the risk of CVD, the researchers say. They point to studies that have found a link between PTSD and cardiotoxic behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and diet. Physiologic alterations that occur with PTSD symptoms also may play an important role, they suggest, such as changes in neuropeptide Y in response to stress, which might contribute to metabolic syndrome.

Citing “particularly intriguing” findings from a study that found symptoms eventually remitted in 44% of individuals with PTSD, the researchers say providing treatment shortly after PTSD symptoms begin could limit the risk of CVD and, potentially, other disease-related risk.

Source:

Gilsanz P, Winning A, Koenen KC, et al. Psychol Med. 2017;47(8):1370-1378.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003378.

Unique Military and VA Nurse Collaboration to Teach and Learn

When military and VA nurses work side by side—learning from and teaching each other—they benefit and so do their patients. A “unique partnership” between the DoD and VA is proving that at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center outside Chicago, Illinois.

The first of its kind facility serves nearly 67,000 active-duty military, military retirees, family members, and veterans. In an article for Health.mil News, U.S. Navy Lt. Nathan Aranas, an active-duty registered nurse (RN) and assistant nurse manager in the emergency department (ED), says, “We learn from local trauma, mental health, and pediatrics and birthing centers, exposing me more to how medicine outside of the military is practiced. It gives me a bigger perspective of how the rest of the country operates as a health care institution.”

Christine Barassi-Jackson, a VA civilian RN, nurse manager in the ED, says “having a combined organization is a great balance that pulls out the best parts of both the Navy and VA.” She leans on Aranas, the article says, to serve as an interpreter with some of the patients. “Knowing more of the Navy culture helps break down walls with the patients and other providers.” Aranas also believes that former active-duty patients may be more at ease with a uniformed nurse “because they understand the lingo.”

Overall, Aranas says, “It’s a great experience for young, active-duty clinicians to have."

When military and VA nurses work side by side—learning from and teaching each other—they benefit and so do their patients. A “unique partnership” between the DoD and VA is proving that at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center outside Chicago, Illinois.

The first of its kind facility serves nearly 67,000 active-duty military, military retirees, family members, and veterans. In an article for Health.mil News, U.S. Navy Lt. Nathan Aranas, an active-duty registered nurse (RN) and assistant nurse manager in the emergency department (ED), says, “We learn from local trauma, mental health, and pediatrics and birthing centers, exposing me more to how medicine outside of the military is practiced. It gives me a bigger perspective of how the rest of the country operates as a health care institution.”

Christine Barassi-Jackson, a VA civilian RN, nurse manager in the ED, says “having a combined organization is a great balance that pulls out the best parts of both the Navy and VA.” She leans on Aranas, the article says, to serve as an interpreter with some of the patients. “Knowing more of the Navy culture helps break down walls with the patients and other providers.” Aranas also believes that former active-duty patients may be more at ease with a uniformed nurse “because they understand the lingo.”

Overall, Aranas says, “It’s a great experience for young, active-duty clinicians to have."

When military and VA nurses work side by side—learning from and teaching each other—they benefit and so do their patients. A “unique partnership” between the DoD and VA is proving that at Captain James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center outside Chicago, Illinois.

The first of its kind facility serves nearly 67,000 active-duty military, military retirees, family members, and veterans. In an article for Health.mil News, U.S. Navy Lt. Nathan Aranas, an active-duty registered nurse (RN) and assistant nurse manager in the emergency department (ED), says, “We learn from local trauma, mental health, and pediatrics and birthing centers, exposing me more to how medicine outside of the military is practiced. It gives me a bigger perspective of how the rest of the country operates as a health care institution.”

Christine Barassi-Jackson, a VA civilian RN, nurse manager in the ED, says “having a combined organization is a great balance that pulls out the best parts of both the Navy and VA.” She leans on Aranas, the article says, to serve as an interpreter with some of the patients. “Knowing more of the Navy culture helps break down walls with the patients and other providers.” Aranas also believes that former active-duty patients may be more at ease with a uniformed nurse “because they understand the lingo.”

Overall, Aranas says, “It’s a great experience for young, active-duty clinicians to have."

Combo with daratumumab could be alternative to ASCT in MM

CHICAGO—Results of an open-label phase 1b study of daratumumab combined with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have shown the combination to be highly effective, with an overall response rate of 100%.

Ninety-one percent of patients achieved a very good partial response (VGPR) or better, and 43% achieved a complete response (CR) or better.

Investigators had hypothesized that rather than using autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) to improve results of treatment with KRd, the combination could alternatively be improved by incorporating daratumumab into a KRd regimen.

Andrzej Jakubowiak, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center in Illinois, presented the findings of the MMY1001 study at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 8000*).

“I think what was one of the more important developments in myeloma last year,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “was data from randomized studies showing that adding daratumumab to either lenalidomide and dexamethasone in the POLLUX study or bortezomib and dexamethasone, a proteasome inhibitor, in the CASTOR study, improves responses, depth of response, and . . . dramatically improved progression-free survival.”

“[W]e have now the rationale to potentially combine daratumumab with both an IMiD and proteasome inhibitor,” he explained, “which led to the development of this phase 1b study in which we combined daratumumab with KRd and evaluated tolerability and efficacy.”

Study design

Twenty-two transplant-eligible or -ineligible newly diagnosed MM patients were enrolled on the study.

Treatment duration was planned to be 13 cycles or less and patients had the option to move to transplant after 4 cycles.

They could have no clinically significant cardiac disease and echocardiogram was required prior to transplant.

The dosing schedule was the established dosing schema for daratumumab and KRd with 2 notable differences in the 28-day cycles.

First, the daratumumab dose was a split dose. So patients received 8 mg/kg on days 1-2 of cycle 1, 16 mg/kg a week on cycle 2, 16 mg/kg every 2 weeks on cycles 3 – 6, and every 4th week thereafter.

The second difference was carfilzomib dosing was a weekly regimen with escalation from 20 mg/m2 on day 1, cycle 1 to 70 mg/m2 on day 8 of cycle 1.

Lenalidomide (25 mg on days 1-21 of each cycle) and dexamethasone (40 mg/week) were the standard regimens for these drugs.

The primary endpoint was safety and tolerability. The secondary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), duration of response, time to response, and infusion-related reactions (IRR).

The study also had an exploratory endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS).

Baseline characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59.5 years (range 34 – 74). About two thirds were younger than 65 and one third were between 65 and 75.

A little over half were male and most (86%) were white.

A little more than half (55%) had an ECOG score of 0, 41% were ECOG 1, and 5% were ECOG 2.

Patient disposition

As of the cutoff date of March 24, 8 of the 22 patients enrolled (36%) discontinued treatment: 1 due to an adverse event (AE), 1 due to progressive disease, and 6 patients (27%) proceeded to ASCT.

Dr Jakubowiak pointed out that response was censored at this point for patients who proceeded to transplant.

The median follow-up was 10.8 months (range, 4.0 – 12.5) and the median number of treatment cycles was 11.5 (range, 1.0 – 13.0).

“What is of interest to many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “is that patients were escalated to the planned dose of 70 mg/m2 by cycle 2 except for 3 patients.”

Of the 3, 1 discontinued before day 1 of the second cycle due to toxicity, 1 had a dose reduction to 56 mg/m2 at day of the second cycle, and 1 escalated to 70 mg/m2 at day 8 of cycle 3.

Ultimately, all patients who remained on study were able to escalate to 70 mg/m2.

Safety

The hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) generally followed what has been observed in similar studies before, Dr Jakubowiak noted.

Hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% or more of patients were lymphopenia (68%), thrombocytopenia (55%), anemia (46%), leukopenia (41%), and neutropenia (32%).

The most common non-hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% of patients or more were diarrhea (73%), upper respiratory infection (59%) cough, constipation, and fatigue (50% each), dyspnea and insomnia (46%), nausea, rash, and back pain (41%), muscle spasm (36%), and vomiting, pain in extremity, hyperglycemia, and increased ALT (32%).

The most common grade 3/4 TEAEs were infrequent and many events had none of grade 3/4 severity.

The safety profile is consistent with what was previously reported for daratumumab or KRd, Dr Jakubowiak affirmed.

Serious TEAEs

Serious TEAEs occurred in 10 patients (46%), with many occurring in just 1 patient. Pulmonary embolism (PE) was the most frequent, occurring in 3 patients.

All patients were required to be on aspirin prophylaxis and 1 of the patients who had a PE discontinued therapy.

The number of patients with a serious TEAE reasonably related to an individual study drug were 3 (14%) for daratumumab, 5 (23%) for carfilzomib, 5 (23%) for lenalidomide, and 2 (9%) for dexamethasone.

The TEAEs of interest—tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and hypertension—occurred in a single patient each.

Overall, serious TEAEs were consistent with previous reports from KRd studies.

Echocardiogram assessment

Investigators conducted 30 systemic evaluations on the impact of this regimen on heart function. The investigators observed no change from baseline through the duration of treatment in patients’ left ventricular ejection fractions.

One patient developed congestive heart failure, possibly related to daratumumab or carfilzomib. This patient resumed treatment with a reduced carfilzomib dose, elected ASCT on study day 113, and ended treatment with a VGPR.

“In all,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “we feel that there is no apparent signal of adverse impact of the addition of daratumumab on cardiac function.”

Infusion times and reactions

Overall, IRRs occurred in 27% of the patients, “which appears lower than with previous daratumumab studies,” Dr Jakubowiak noted. And IRRs occurred more frequently during the first infusion than subsequent infusions.

The split-dose infusion time was very similar to that of second and subsequent cycles.

There were limited events related to infusions. All were grade 1 or 2 and most occurred in only a single patient.

Response rate

The median number of treatment cycles administered was 11.5 (range, 2.0 – 13.0). The best response was 100% PR or better, 91% achieved VGPR or better, 42% CR or better, and 29% a stringent CR.

The depth of response improved with duration of treatment. For example, the sCR rate increased from 5% after 4 cycles to 29% at the end of treatment.

PFS was an exploratory endpoint. One patient progressed at 10.8 months and the 12-month PFS rate was 94% with all patients alive.

Stem cell harvest and ASCT

“For many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak commented, “it’s also of interest how this regimen will impact stem cell harvest.”

Nineteen of 22 patients were deemed to be transplant eligible, and the median number of CD34+ cells collected from them was 10.4 x 106 cells/kg.

Patients had a median of 5 treatment cycles prior to stem cell harvest, and 14 (74%) had a VGPR or better prior to harvest.

The investigators believe stem cell yield was consistent with previous KRd studies.

Dr Jakubowiak commented that the deepening of response over time “is a phenomenon we think is important. . . . In all, the data from this small phase 1b study provide support for further evaluation of this regimen in newly diagnosed myeloma."

The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development, LLC. ![]()

*Data presented during the meeting differ from the abstract.

CHICAGO—Results of an open-label phase 1b study of daratumumab combined with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have shown the combination to be highly effective, with an overall response rate of 100%.

Ninety-one percent of patients achieved a very good partial response (VGPR) or better, and 43% achieved a complete response (CR) or better.

Investigators had hypothesized that rather than using autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) to improve results of treatment with KRd, the combination could alternatively be improved by incorporating daratumumab into a KRd regimen.

Andrzej Jakubowiak, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center in Illinois, presented the findings of the MMY1001 study at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 8000*).

“I think what was one of the more important developments in myeloma last year,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “was data from randomized studies showing that adding daratumumab to either lenalidomide and dexamethasone in the POLLUX study or bortezomib and dexamethasone, a proteasome inhibitor, in the CASTOR study, improves responses, depth of response, and . . . dramatically improved progression-free survival.”

“[W]e have now the rationale to potentially combine daratumumab with both an IMiD and proteasome inhibitor,” he explained, “which led to the development of this phase 1b study in which we combined daratumumab with KRd and evaluated tolerability and efficacy.”

Study design

Twenty-two transplant-eligible or -ineligible newly diagnosed MM patients were enrolled on the study.

Treatment duration was planned to be 13 cycles or less and patients had the option to move to transplant after 4 cycles.

They could have no clinically significant cardiac disease and echocardiogram was required prior to transplant.

The dosing schedule was the established dosing schema for daratumumab and KRd with 2 notable differences in the 28-day cycles.

First, the daratumumab dose was a split dose. So patients received 8 mg/kg on days 1-2 of cycle 1, 16 mg/kg a week on cycle 2, 16 mg/kg every 2 weeks on cycles 3 – 6, and every 4th week thereafter.

The second difference was carfilzomib dosing was a weekly regimen with escalation from 20 mg/m2 on day 1, cycle 1 to 70 mg/m2 on day 8 of cycle 1.

Lenalidomide (25 mg on days 1-21 of each cycle) and dexamethasone (40 mg/week) were the standard regimens for these drugs.

The primary endpoint was safety and tolerability. The secondary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), duration of response, time to response, and infusion-related reactions (IRR).

The study also had an exploratory endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS).

Baseline characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59.5 years (range 34 – 74). About two thirds were younger than 65 and one third were between 65 and 75.

A little over half were male and most (86%) were white.

A little more than half (55%) had an ECOG score of 0, 41% were ECOG 1, and 5% were ECOG 2.

Patient disposition

As of the cutoff date of March 24, 8 of the 22 patients enrolled (36%) discontinued treatment: 1 due to an adverse event (AE), 1 due to progressive disease, and 6 patients (27%) proceeded to ASCT.

Dr Jakubowiak pointed out that response was censored at this point for patients who proceeded to transplant.

The median follow-up was 10.8 months (range, 4.0 – 12.5) and the median number of treatment cycles was 11.5 (range, 1.0 – 13.0).

“What is of interest to many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “is that patients were escalated to the planned dose of 70 mg/m2 by cycle 2 except for 3 patients.”

Of the 3, 1 discontinued before day 1 of the second cycle due to toxicity, 1 had a dose reduction to 56 mg/m2 at day of the second cycle, and 1 escalated to 70 mg/m2 at day 8 of cycle 3.

Ultimately, all patients who remained on study were able to escalate to 70 mg/m2.

Safety

The hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) generally followed what has been observed in similar studies before, Dr Jakubowiak noted.

Hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% or more of patients were lymphopenia (68%), thrombocytopenia (55%), anemia (46%), leukopenia (41%), and neutropenia (32%).

The most common non-hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% of patients or more were diarrhea (73%), upper respiratory infection (59%) cough, constipation, and fatigue (50% each), dyspnea and insomnia (46%), nausea, rash, and back pain (41%), muscle spasm (36%), and vomiting, pain in extremity, hyperglycemia, and increased ALT (32%).

The most common grade 3/4 TEAEs were infrequent and many events had none of grade 3/4 severity.

The safety profile is consistent with what was previously reported for daratumumab or KRd, Dr Jakubowiak affirmed.

Serious TEAEs

Serious TEAEs occurred in 10 patients (46%), with many occurring in just 1 patient. Pulmonary embolism (PE) was the most frequent, occurring in 3 patients.

All patients were required to be on aspirin prophylaxis and 1 of the patients who had a PE discontinued therapy.

The number of patients with a serious TEAE reasonably related to an individual study drug were 3 (14%) for daratumumab, 5 (23%) for carfilzomib, 5 (23%) for lenalidomide, and 2 (9%) for dexamethasone.

The TEAEs of interest—tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and hypertension—occurred in a single patient each.

Overall, serious TEAEs were consistent with previous reports from KRd studies.

Echocardiogram assessment

Investigators conducted 30 systemic evaluations on the impact of this regimen on heart function. The investigators observed no change from baseline through the duration of treatment in patients’ left ventricular ejection fractions.

One patient developed congestive heart failure, possibly related to daratumumab or carfilzomib. This patient resumed treatment with a reduced carfilzomib dose, elected ASCT on study day 113, and ended treatment with a VGPR.

“In all,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “we feel that there is no apparent signal of adverse impact of the addition of daratumumab on cardiac function.”

Infusion times and reactions

Overall, IRRs occurred in 27% of the patients, “which appears lower than with previous daratumumab studies,” Dr Jakubowiak noted. And IRRs occurred more frequently during the first infusion than subsequent infusions.

The split-dose infusion time was very similar to that of second and subsequent cycles.

There were limited events related to infusions. All were grade 1 or 2 and most occurred in only a single patient.

Response rate

The median number of treatment cycles administered was 11.5 (range, 2.0 – 13.0). The best response was 100% PR or better, 91% achieved VGPR or better, 42% CR or better, and 29% a stringent CR.

The depth of response improved with duration of treatment. For example, the sCR rate increased from 5% after 4 cycles to 29% at the end of treatment.

PFS was an exploratory endpoint. One patient progressed at 10.8 months and the 12-month PFS rate was 94% with all patients alive.

Stem cell harvest and ASCT

“For many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak commented, “it’s also of interest how this regimen will impact stem cell harvest.”

Nineteen of 22 patients were deemed to be transplant eligible, and the median number of CD34+ cells collected from them was 10.4 x 106 cells/kg.

Patients had a median of 5 treatment cycles prior to stem cell harvest, and 14 (74%) had a VGPR or better prior to harvest.

The investigators believe stem cell yield was consistent with previous KRd studies.

Dr Jakubowiak commented that the deepening of response over time “is a phenomenon we think is important. . . . In all, the data from this small phase 1b study provide support for further evaluation of this regimen in newly diagnosed myeloma."

The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development, LLC. ![]()

*Data presented during the meeting differ from the abstract.

CHICAGO—Results of an open-label phase 1b study of daratumumab combined with carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (KRd) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients have shown the combination to be highly effective, with an overall response rate of 100%.

Ninety-one percent of patients achieved a very good partial response (VGPR) or better, and 43% achieved a complete response (CR) or better.

Investigators had hypothesized that rather than using autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) to improve results of treatment with KRd, the combination could alternatively be improved by incorporating daratumumab into a KRd regimen.

Andrzej Jakubowiak, MD, of the University of Chicago Medical Center in Illinois, presented the findings of the MMY1001 study at the 2017 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 8000*).

“I think what was one of the more important developments in myeloma last year,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “was data from randomized studies showing that adding daratumumab to either lenalidomide and dexamethasone in the POLLUX study or bortezomib and dexamethasone, a proteasome inhibitor, in the CASTOR study, improves responses, depth of response, and . . . dramatically improved progression-free survival.”

“[W]e have now the rationale to potentially combine daratumumab with both an IMiD and proteasome inhibitor,” he explained, “which led to the development of this phase 1b study in which we combined daratumumab with KRd and evaluated tolerability and efficacy.”

Study design

Twenty-two transplant-eligible or -ineligible newly diagnosed MM patients were enrolled on the study.

Treatment duration was planned to be 13 cycles or less and patients had the option to move to transplant after 4 cycles.

They could have no clinically significant cardiac disease and echocardiogram was required prior to transplant.

The dosing schedule was the established dosing schema for daratumumab and KRd with 2 notable differences in the 28-day cycles.

First, the daratumumab dose was a split dose. So patients received 8 mg/kg on days 1-2 of cycle 1, 16 mg/kg a week on cycle 2, 16 mg/kg every 2 weeks on cycles 3 – 6, and every 4th week thereafter.

The second difference was carfilzomib dosing was a weekly regimen with escalation from 20 mg/m2 on day 1, cycle 1 to 70 mg/m2 on day 8 of cycle 1.

Lenalidomide (25 mg on days 1-21 of each cycle) and dexamethasone (40 mg/week) were the standard regimens for these drugs.

The primary endpoint was safety and tolerability. The secondary endpoint was overall response rate (ORR), duration of response, time to response, and infusion-related reactions (IRR).

The study also had an exploratory endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS).

Baseline characteristics

Patients were a median age of 59.5 years (range 34 – 74). About two thirds were younger than 65 and one third were between 65 and 75.

A little over half were male and most (86%) were white.

A little more than half (55%) had an ECOG score of 0, 41% were ECOG 1, and 5% were ECOG 2.

Patient disposition

As of the cutoff date of March 24, 8 of the 22 patients enrolled (36%) discontinued treatment: 1 due to an adverse event (AE), 1 due to progressive disease, and 6 patients (27%) proceeded to ASCT.

Dr Jakubowiak pointed out that response was censored at this point for patients who proceeded to transplant.

The median follow-up was 10.8 months (range, 4.0 – 12.5) and the median number of treatment cycles was 11.5 (range, 1.0 – 13.0).

“What is of interest to many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “is that patients were escalated to the planned dose of 70 mg/m2 by cycle 2 except for 3 patients.”

Of the 3, 1 discontinued before day 1 of the second cycle due to toxicity, 1 had a dose reduction to 56 mg/m2 at day of the second cycle, and 1 escalated to 70 mg/m2 at day 8 of cycle 3.

Ultimately, all patients who remained on study were able to escalate to 70 mg/m2.

Safety

The hematologic treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAE) generally followed what has been observed in similar studies before, Dr Jakubowiak noted.

Hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% or more of patients were lymphopenia (68%), thrombocytopenia (55%), anemia (46%), leukopenia (41%), and neutropenia (32%).

The most common non-hematologic TEAEs of all grades occurring in 30% of patients or more were diarrhea (73%), upper respiratory infection (59%) cough, constipation, and fatigue (50% each), dyspnea and insomnia (46%), nausea, rash, and back pain (41%), muscle spasm (36%), and vomiting, pain in extremity, hyperglycemia, and increased ALT (32%).

The most common grade 3/4 TEAEs were infrequent and many events had none of grade 3/4 severity.

The safety profile is consistent with what was previously reported for daratumumab or KRd, Dr Jakubowiak affirmed.

Serious TEAEs

Serious TEAEs occurred in 10 patients (46%), with many occurring in just 1 patient. Pulmonary embolism (PE) was the most frequent, occurring in 3 patients.

All patients were required to be on aspirin prophylaxis and 1 of the patients who had a PE discontinued therapy.

The number of patients with a serious TEAE reasonably related to an individual study drug were 3 (14%) for daratumumab, 5 (23%) for carfilzomib, 5 (23%) for lenalidomide, and 2 (9%) for dexamethasone.

The TEAEs of interest—tachycardia, congestive heart failure, and hypertension—occurred in a single patient each.

Overall, serious TEAEs were consistent with previous reports from KRd studies.

Echocardiogram assessment

Investigators conducted 30 systemic evaluations on the impact of this regimen on heart function. The investigators observed no change from baseline through the duration of treatment in patients’ left ventricular ejection fractions.

One patient developed congestive heart failure, possibly related to daratumumab or carfilzomib. This patient resumed treatment with a reduced carfilzomib dose, elected ASCT on study day 113, and ended treatment with a VGPR.

“In all,” Dr Jakubowiak said, “we feel that there is no apparent signal of adverse impact of the addition of daratumumab on cardiac function.”

Infusion times and reactions

Overall, IRRs occurred in 27% of the patients, “which appears lower than with previous daratumumab studies,” Dr Jakubowiak noted. And IRRs occurred more frequently during the first infusion than subsequent infusions.

The split-dose infusion time was very similar to that of second and subsequent cycles.

There were limited events related to infusions. All were grade 1 or 2 and most occurred in only a single patient.

Response rate

The median number of treatment cycles administered was 11.5 (range, 2.0 – 13.0). The best response was 100% PR or better, 91% achieved VGPR or better, 42% CR or better, and 29% a stringent CR.

The depth of response improved with duration of treatment. For example, the sCR rate increased from 5% after 4 cycles to 29% at the end of treatment.

PFS was an exploratory endpoint. One patient progressed at 10.8 months and the 12-month PFS rate was 94% with all patients alive.

Stem cell harvest and ASCT

“For many of us,” Dr Jakubowiak commented, “it’s also of interest how this regimen will impact stem cell harvest.”

Nineteen of 22 patients were deemed to be transplant eligible, and the median number of CD34+ cells collected from them was 10.4 x 106 cells/kg.

Patients had a median of 5 treatment cycles prior to stem cell harvest, and 14 (74%) had a VGPR or better prior to harvest.

The investigators believe stem cell yield was consistent with previous KRd studies.

Dr Jakubowiak commented that the deepening of response over time “is a phenomenon we think is important. . . . In all, the data from this small phase 1b study provide support for further evaluation of this regimen in newly diagnosed myeloma."

The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development, LLC. ![]()

*Data presented during the meeting differ from the abstract.

Assessing the risks associated with MRI patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator

Clinical Question: What are the risks of nonthoracic MRI in patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) who are not preapproved by the Food and Drug Administration for MRI scanning?

Background: Implantable cardiovascular devices could suffer heating in MRI magnetic fields leading to cardiac thermal injury and changes in pacing properties. The FDA approves “MRI-conditional devices” deemed safe for MRI, but up to six million patients worldwide (and two million in the United States) have non–MRI conditional devices.

Setting: U.S. Centers participating in the MagnaSafe registry.

Synopsis: Adults with non–MRI conditional pacemakers (1000 cases) or ICDs (500 cases) implanted in the thorax after 2001 were scanned with nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla. Patients with abandoned or inactive leads, other implantable devices, and low batteries and pacing-dependent patients with ICDs were excluded.

Devices were interrogated before each MRI and set to either no pacing or asynchronous pacing with all tachycardia and bradycardia therapies deactivated. Primary endpoints included immediate death, generator or lead failure, loss of capture in paced patients, new arrhythmia, and generator reset.

No patients suffered death or device or lead failure. Six patients developed self-terminating atrial arrhythmias, while an additional six had partial pacemaker electrical reset. Several devices had detectable changes in battery voltage, lead impedance, pacing threshold, and P- or R-wave amplitude without evident clinical significance. Multiple MRIs caused no increase in adverse outcomes. This study suggests that patients with non–MRI conditional devices may be at low risk from nonthoracic imaging if appropriately screened with temporary pacemaker function modification before MRI.

Bottom Line: Appropriately screened and prepared patients with non–MRI conditional thoracic pacemakers or ICDs may be at low risk for complications from nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla.

Reference: Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:755-64.

Dr. Frederick is assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital Medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: What are the risks of nonthoracic MRI in patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) who are not preapproved by the Food and Drug Administration for MRI scanning?

Background: Implantable cardiovascular devices could suffer heating in MRI magnetic fields leading to cardiac thermal injury and changes in pacing properties. The FDA approves “MRI-conditional devices” deemed safe for MRI, but up to six million patients worldwide (and two million in the United States) have non–MRI conditional devices.

Setting: U.S. Centers participating in the MagnaSafe registry.

Synopsis: Adults with non–MRI conditional pacemakers (1000 cases) or ICDs (500 cases) implanted in the thorax after 2001 were scanned with nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla. Patients with abandoned or inactive leads, other implantable devices, and low batteries and pacing-dependent patients with ICDs were excluded.

Devices were interrogated before each MRI and set to either no pacing or asynchronous pacing with all tachycardia and bradycardia therapies deactivated. Primary endpoints included immediate death, generator or lead failure, loss of capture in paced patients, new arrhythmia, and generator reset.

No patients suffered death or device or lead failure. Six patients developed self-terminating atrial arrhythmias, while an additional six had partial pacemaker electrical reset. Several devices had detectable changes in battery voltage, lead impedance, pacing threshold, and P- or R-wave amplitude without evident clinical significance. Multiple MRIs caused no increase in adverse outcomes. This study suggests that patients with non–MRI conditional devices may be at low risk from nonthoracic imaging if appropriately screened with temporary pacemaker function modification before MRI.

Bottom Line: Appropriately screened and prepared patients with non–MRI conditional thoracic pacemakers or ICDs may be at low risk for complications from nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla.

Reference: Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:755-64.

Dr. Frederick is assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital Medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: What are the risks of nonthoracic MRI in patients with pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICD) who are not preapproved by the Food and Drug Administration for MRI scanning?

Background: Implantable cardiovascular devices could suffer heating in MRI magnetic fields leading to cardiac thermal injury and changes in pacing properties. The FDA approves “MRI-conditional devices” deemed safe for MRI, but up to six million patients worldwide (and two million in the United States) have non–MRI conditional devices.

Setting: U.S. Centers participating in the MagnaSafe registry.

Synopsis: Adults with non–MRI conditional pacemakers (1000 cases) or ICDs (500 cases) implanted in the thorax after 2001 were scanned with nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla. Patients with abandoned or inactive leads, other implantable devices, and low batteries and pacing-dependent patients with ICDs were excluded.

Devices were interrogated before each MRI and set to either no pacing or asynchronous pacing with all tachycardia and bradycardia therapies deactivated. Primary endpoints included immediate death, generator or lead failure, loss of capture in paced patients, new arrhythmia, and generator reset.

No patients suffered death or device or lead failure. Six patients developed self-terminating atrial arrhythmias, while an additional six had partial pacemaker electrical reset. Several devices had detectable changes in battery voltage, lead impedance, pacing threshold, and P- or R-wave amplitude without evident clinical significance. Multiple MRIs caused no increase in adverse outcomes. This study suggests that patients with non–MRI conditional devices may be at low risk from nonthoracic imaging if appropriately screened with temporary pacemaker function modification before MRI.

Bottom Line: Appropriately screened and prepared patients with non–MRI conditional thoracic pacemakers or ICDs may be at low risk for complications from nonthoracic MRI at 1.5 Tesla.

Reference: Russo RJ, Costa HS, Silva PD, et al. Assessing the risks associated with MRI in patients with a pacemaker or defibrillator. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:755-64.

Dr. Frederick is assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital Medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

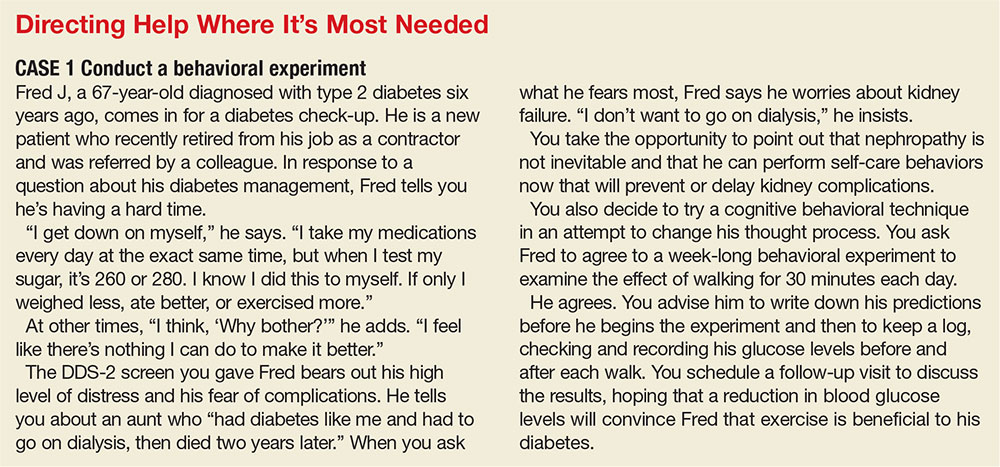

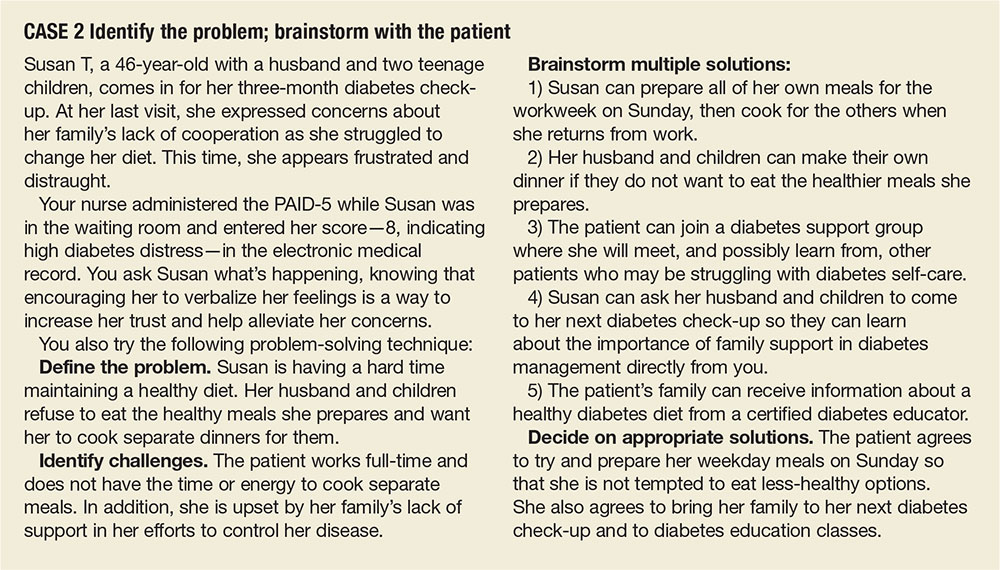

Is Diabetes Distress on Your Radar Screen?

Managing diabetes is a complex undertaking, with an extensive regimen of self-care—including regular exercise, meal planning, blood glucose monitoring, medication scheduling, and multiple visits—that is critically linked to glycemic control and the prevention of complications. Incorporating all of these elements into daily life can be daunting.1-3

In fact, nearly half of US adults with diabetes fail to meet the recommended targets.4 This leads to frustration, which often manifests in psychosocial problems that further hamper efforts to manage the disease.5-10 The most notable is a psychosocial disorder known as diabetes distress, which affects close to 45% of persons with diabetes.11,12

It is important to note that diabetes distress is not a psychiatric disorder; rather, it is a broad affective reaction to the stress of living with this chronic and complex disease.13-15 By negatively affecting adherence to a self-care regimen, diabetes distress contributes to worsening glycemic control and increasing morbidity.16-18

Recognizing that about 80% of those with diabetes are treated in primary care settings, this review is intended to call your attention to diabetes distress, alert you to brief screening tools that can easily be incorporated into clinic visits, and offer guidance in matching proposed interventions to the aspects of diabetes self-management that cause patients the greatest distress.19

DIABETES DISTRESS: WHAT IT IS, WHAT IT'S NOT

For patients with type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress centers around four main issues

- Frustration with the demands of self-care

- Apprehension about the future and the possibility of developing serious complications

- Concern about both the quality and the cost of required medical care

- Perceived lack of support from family and/or friends.11,12,20

As mentioned earlier, diabetes distress is not a psychiatric condition and should not be confused with major depressive disorder (MDD). Here’s help in telling the difference.

For starters, a diagnosis of depression is symptom-based.13 MDD requires the presence of at least five of the nine symptoms defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. (DSM-5)—eg, persistent feelings of worthlessness or guilt, sleep disturbances, lack of interest in normal activities—for at least two weeks.21 What’s more, the diagnostic criteria for MDD do not specify a cause or disease process. Nor do they distinguish between a pathological response and an expected reaction to a stressful life event.22 Further, depression measures reflect symptoms (eg, hyperglycemia), as well as stressful experiences resulting from diabetes self-care, which may contribute to the high rate of false positives or incorrect diagnoses of MDD and missed diagnoses of diabetes distress.23

Unlike MDD, diabetes distress has a specific cause—diabetes—and can best be understood as an emotional response to a demanding health condition.13 And, because the source of the problem is identified, diabetes distress can be treated with specific interventions targeting the areas causing the highest levels of stress.

When a psychiatric condition and diabetes distress overlap

MDD, anxiety disorders, and diabetes distress are all common in patients with diabetes, and the co-occurrence of a psychiatric disorder and diabetes distress is high.24,25Thus, it is important not only to identify cases of diabetes distress but also to consider comorbid depression and/or anxiety in patients with diabetes distress.

More often, though, it is the other way around, according to the Distress and Depression in Diabetes (3D) study. The researchers recently found that 84% of patients with moderate or high diabetes distress did not fulfill the criteria for MDD, but that 67% of diabetes patients with MDD also had moderate or high diabetes distress.13,15,17,25

The data highlight the importance of screening patients with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and MDD for diabetes distress. Keep in mind that persons diagnosed with diabetes distress and a comorbid psychiatric condition may require more complex and intensive treatment than those with either diabetes distress or MDD alone.25

SCREENING FOR DIABETES DISTRESS

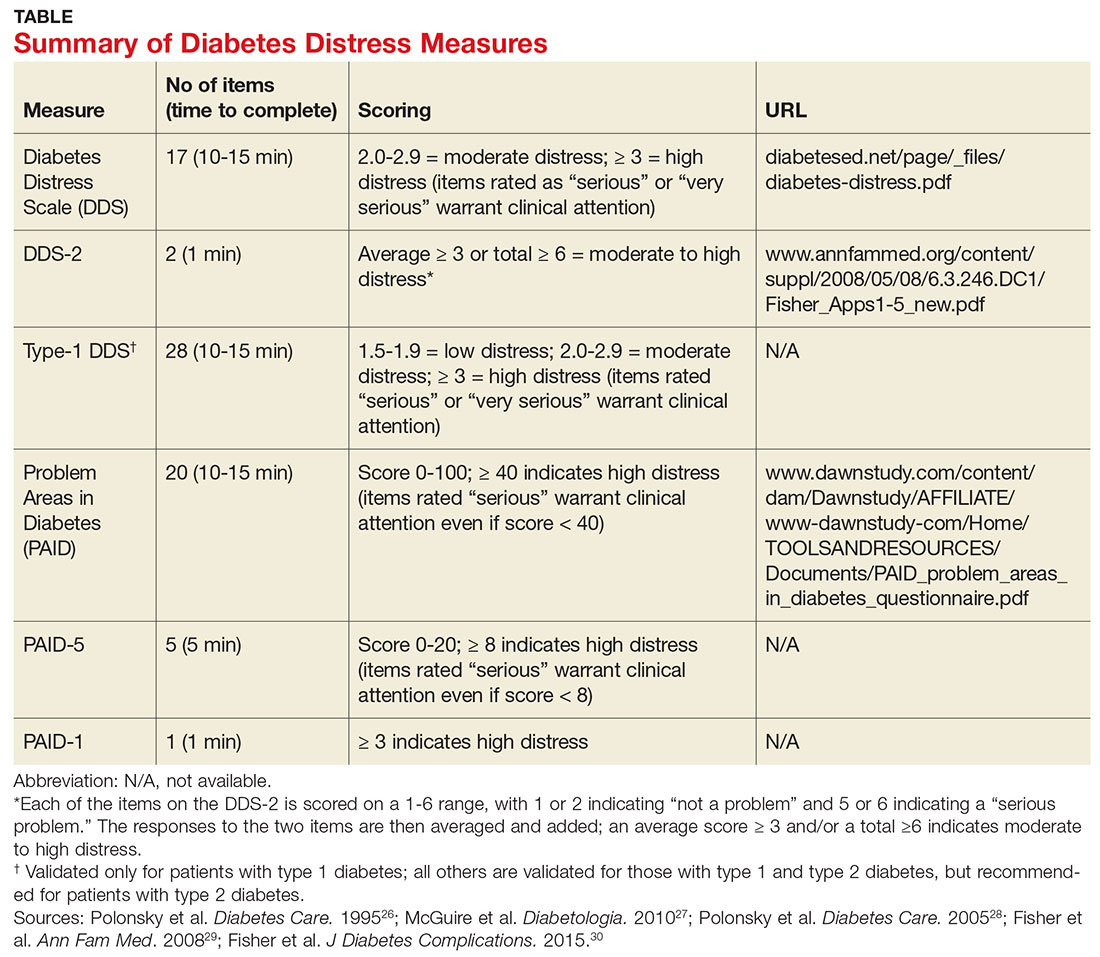

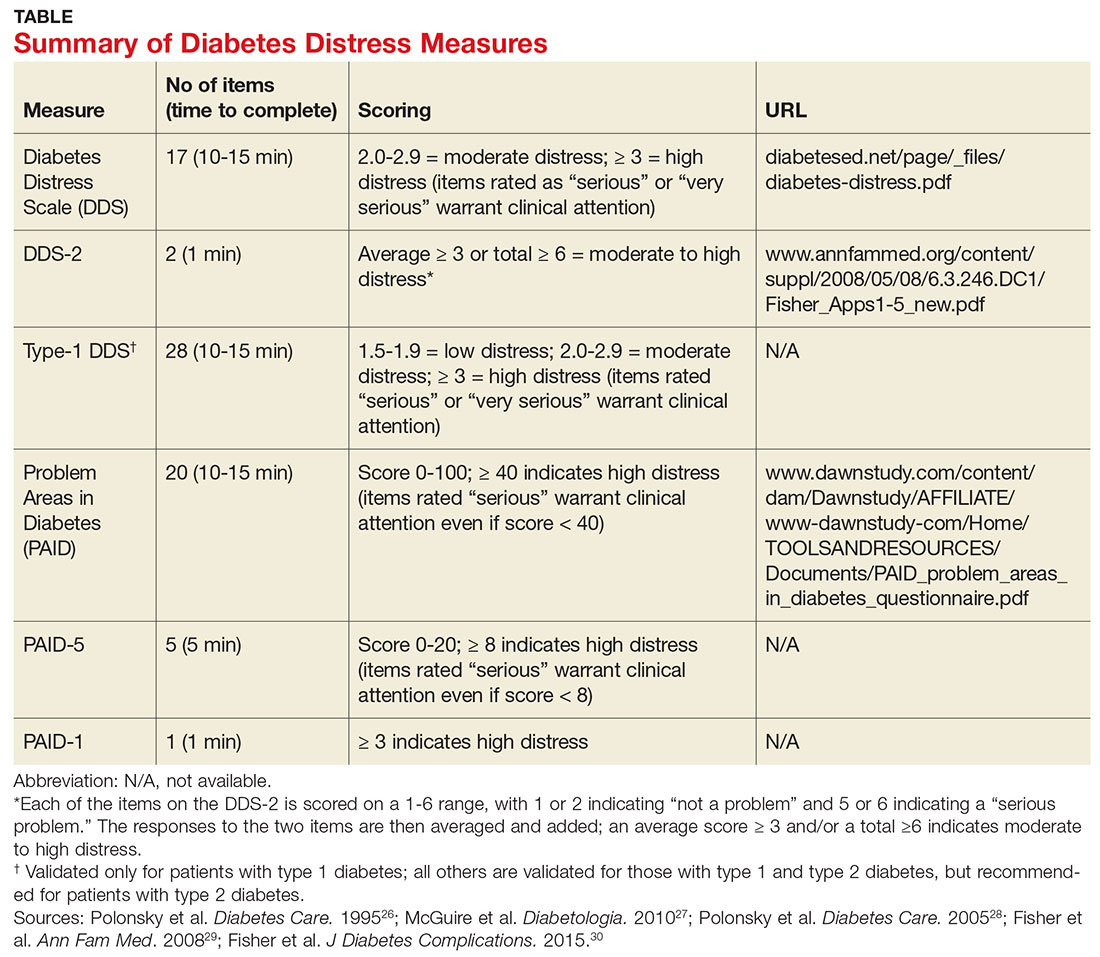

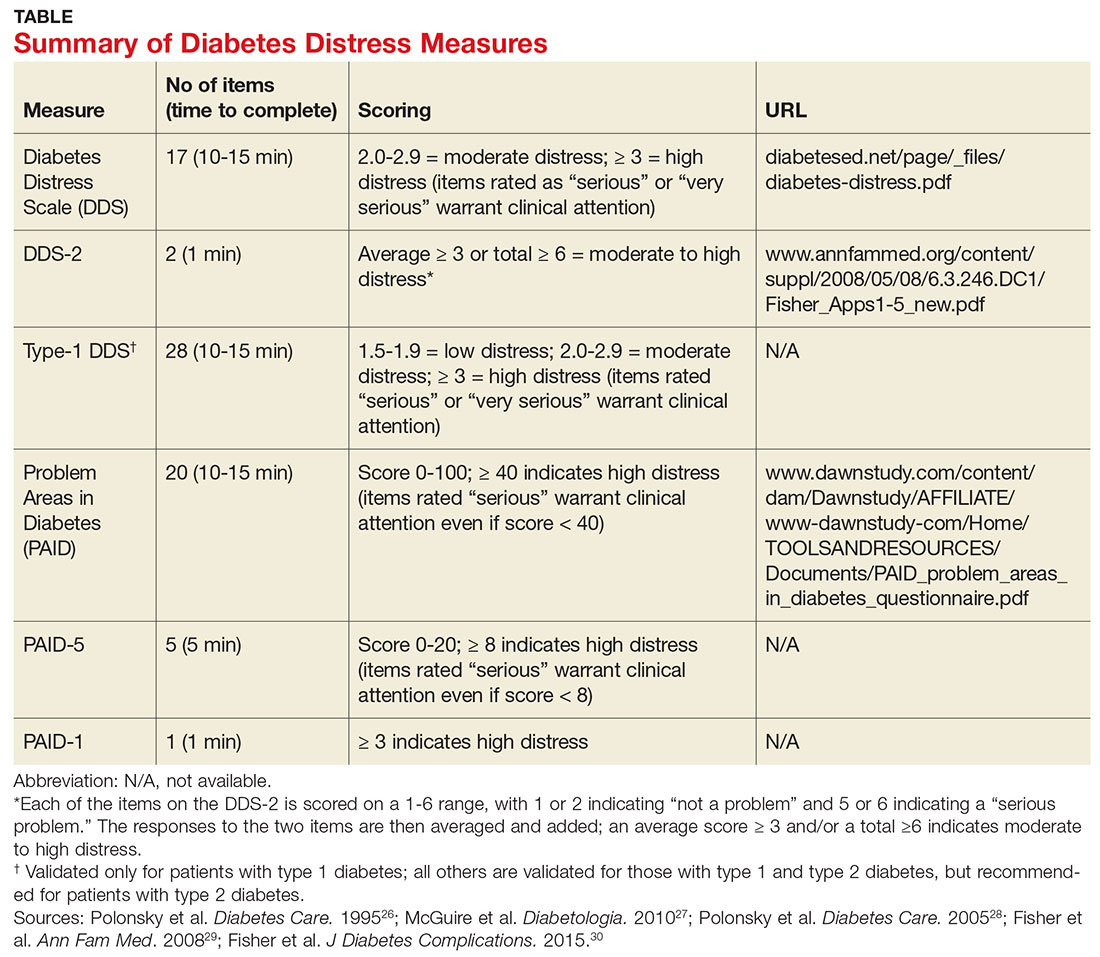

Diabetes distress can be easily assessed using one of several patient-reported outcome measures. Six validated measures, ranging in length from one to 28 questions, are designed for use in primary care (see Table).26-30 Some of the measures are easily accessible online; others require a subscription to MEDLINE.

Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID). There are three versions of PAID—a 20-item screen assessing a broad range of feelings related to living with diabetes and its treatment, a five-item version (PAID-5) with high rates of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (89%), and a single-item test (PAID-1) that is highly correlated with the longer version.26,27

Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS). This tool is available in a 17-item measure assessing diabetes distress as it relates to the emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress, and interpersonal distress.28 DDS is also available in a short form (DDS-2) with two items and a 28-item scale specifically for patients with type 1 diabetes.29,30 T1-DDS, the only diabetes distress measure focused on this particular patient population, assesses the seven sources of distress found to be common among adults with type 1 diabetes: powerlessness, negative social perceptions, physician distress, friend/family distress, hypoglycemia distress, management distress, and eating distress.

Studies have shown that not only do those with type 1 diabetes experience different stressors compared with their type 2 counterparts, but also that they tend to experience distress differently. For patients with type 1 diabetes, for example, powerlessness ranked as the highest source of distress, followed by eating distress and hypoglycemia distress. These sources of distress differ from the regimen distress, emotional burden, interpersonal distress, and physician distress identified by those with type 2 diabetes.30

HOW TO RESPOND TO DIABETES DISTRESS

Diabetes distress is easier to identify than to successfully treat. Few validated treatments for diabetes distress exist and, to our knowledge, only two studies have assessed interventions aimed at reduction of such distress.31,32

The REDEEM trial recruited adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetes distress to participate in a 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT).31 The trial had three arms, comparing the effectiveness of a computer-assisted self-management (CASM) program alone, a CASM program plus in-person diabetes distress–specific problem-solving therapy, and a computer-assisted minimally supportive intervention. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (using the DDS scale and subscales), self-management behaviors, and A1C.

Participants in all three arms showed significant reductions in total diabetes distress and improvements in self-management behaviors, with no significant differences among the groups. No differences in A1C were found. However, those in the CASM program plus distress-specific therapy arm showed a larger reduction in regimen distress compared with the other two groups.31

The DIAMOS trial recruited adults who had type 1 or type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress, and subclinical depressive symptoms for a two-arm RCT.32 One group underwent cognitive behavioral interventions, while the controls had standard group-based diabetes education. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (measured via the PAID scale), depressive symptoms, well-being, diabetes self-care, diabetes acceptance, satisfaction with diabetes treatment, A1C, and subclinical inflammation.

The intervention group showed greater improvement in diabetes distress and depressive symptoms compared with the control group, but no differences in well-being, self-care, treatment satisfaction, A1C, or subclinical inflammation were observed.32

Both studies support the use of problem-solving therapy and cognitive behavioral interventions for patients with diabetes distress. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in the primary care setting.

What else to offer when challenges mount?

Diabetes is a progressive disease, and most patients experience multiple challenges over time. These typically include complications and comorbidities, physical limitations, polypharmacy, hypoglycemia, and cognitive impairment, as well as changes in everything from medication and lifestyle to insurance coverage and social support.33,34 All increase the risk for diabetes distress, as well as related psychiatric conditions.

Aging and diabetes are independent risk factors for cognitive impairment, for example, and the presence of both increases this risk.35 What’s more, diabetes alone is associated with poorer executive function, the higher-level cognitive processes that allow individuals to engage in independent, purposeful, and flexible goal-related behaviors.36-38 Both poor cognitive function and impaired executive function interfere with the ability to perform self-care behaviors such as adjusting insulin doses, drawing insulin into a syringe, or dialing an insulin dose with an insulin pen.39 This in turn can lead to frustration and increase the likelihood of moderate to high diabetes distress.

Assessing diabetes distress in patients with cognitive impairment, poor executive functioning, or other psychological limitations is particularly difficult, however, as no diabetes distress measures take such deficits into account. Thus, primary care providers without expertise in neuropsychology should consider referring patients with such problems to specialists for assessment.

The progressive nature of diabetes also highlights the need for primary care providers to periodically screen for diabetes distress and engage in ongoing discussions about what type of care is best for individual patients, and why. When developing or updating treatment plans and making recommendations, it is crucial to consider the impact the treatment would likely have on the patient’s physical and mental health and to explicitly inquire about and acknowledge his or her values and preferences for care.40-44

It is also important to remain aware of socioeconomic changes—in employment, insurance coverage, and living situations, for example—which are not addressed in the screening tools.

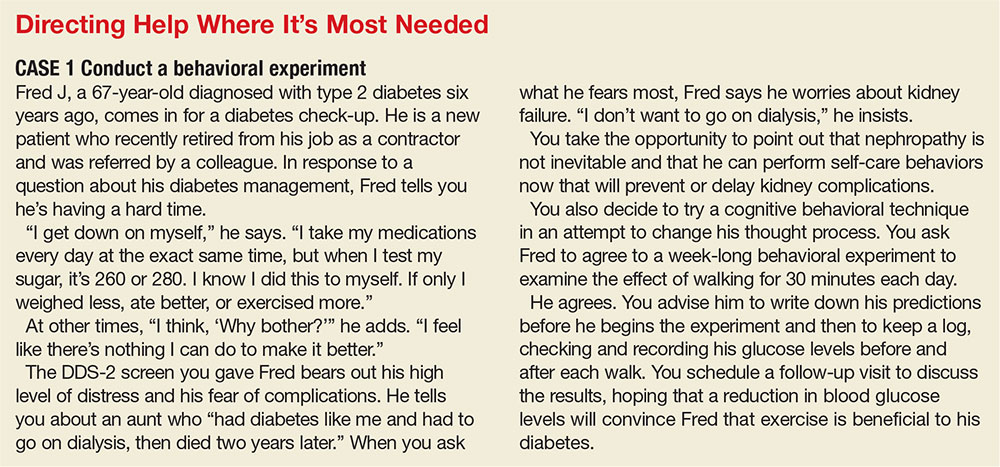

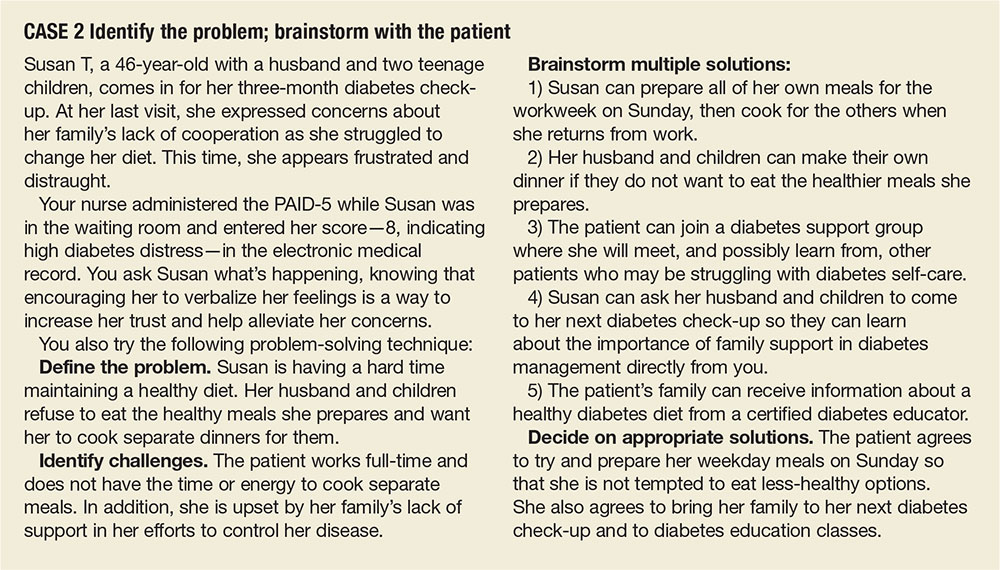

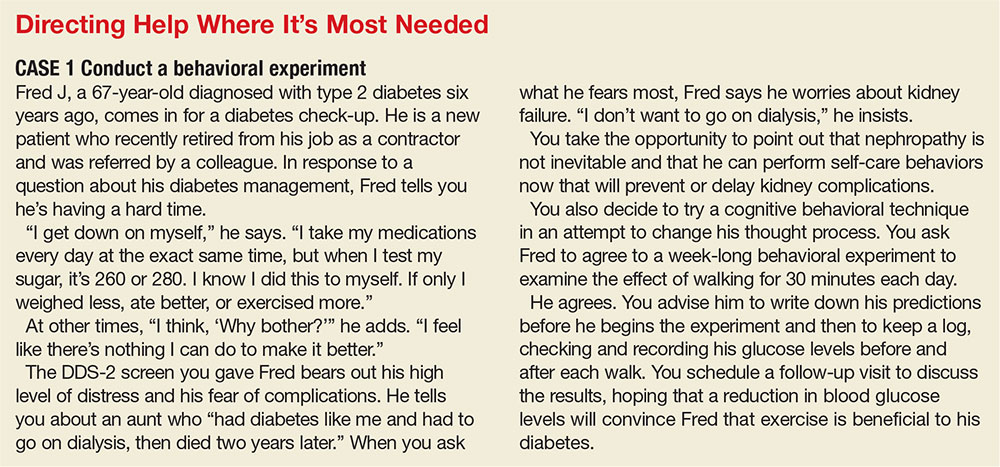

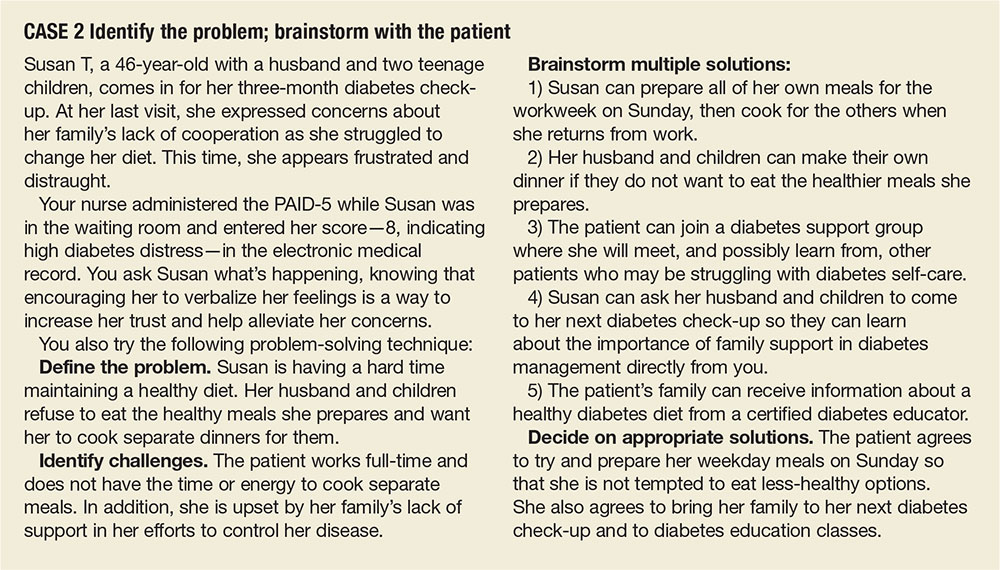

Moderate to high diabetes distress scores, as well as individual items patients identify as “very serious” problems, represent clinical red flags that should be the focus of careful discussion during a medical visit. Patients with moderate to high distress should be referred to a therapist trained in cognitive behavioral therapy or problem-solving therapy. Clinicians who lack access to such resources can incorporate cognitive behavioral and problem-solving techniques into patient discussions. (See “Directing Help Where It’s Most Needed.”) All patients should be referred to a certified diabetes educator—a key component of diabetes care.45,46

1. Gafarian CT, Heiby EM, Blair P, et al. The diabetes time management questionnaire. Diabetes Educ. 1999;25:585-592.

2. Wdowik MJ, Kendall PA, Harris MA. College students with diabetes: using focus groups and interviews to determine psychosocial issues and barriers to control. Diabetes Educ. 1997;23:558-562.

3. Rubin RR. Psychological issues and treatment for people with diabetes. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57:457-478.

4. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999-2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:287-288.

5. Lloyd CE, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: Review of the links. Diabetes Spectr. 2005;18:121-127.

6. Weinger K. Psychosocial issues and self-care. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(6 suppl):S34-S38.

7. Weinger K, Jacobson AM. Psychosocial and quality of life correlates of glycemic control during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;42:123-131.

8. Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: an RRNeST study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354-360.

9. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2222-2227.

10. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25:1102-1107.