User login

PHM17 session summary: Kawasaki Disease updates

NASHVILLE, TENN. – A panel of experts discussed highlights from the 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines at Pediatric Hospital Medicine, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Session

Kawasaki Disease Reconsidered: New AHA Guidelines

Presenters

John Darby, MD, Marietta DeGuzman, MD, Kristen Sexson, MD, PhD, MPH, Stanford Shulman, MD, Nisha Tamaskar, MD

Session summary

For the second year in a row, the session highlighting American Heart Association updates on Kawasaki disease did not disappoint and again attracted a large crowd of community and academic pediatric hospitalists. The newly-revised 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines hot off the press by McCrindle et al. was reviewed in detail.

A secondary theory investigates the tropospheric wind patterns from central Asia and has indicated a possible link to outbreaks of KD in Chile. Despite previous investigation of carpet cleaning and risk for KD, no causal link has been identified.

Experts addressed pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Below are highlights from the new 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guideline Update in conjunction with points from the panel discussion.

Pathophysiology

• Cause is likely to be a common ubiquitous agent that in genetically inclined children will lead to a particular inflammatory response that manifests clinically as KD.

• A new theory about how the “ubiquitous agent” is spread by wind patterns.

Diagnosis

• Confirmed that infants younger than 1 year of age are more difficult to diagnose because they don’t present classically so it must be on the differential.

• The new algorithm makes it clearer that infants with fever for 7 days without symptoms should get lab screening tests for KD.

• Those who have classic symptoms and lab abnormalities consistent with KD but in whom fever is still at 3-4 days may be diagnosed with KD prior to the “5 days of fever rule” because these tend to be a sicker cohort of patients with higher rate of complications. Pretest probability and suspicion for KD must be high to treat before 5 days.

• Importance of the Z-score when evaluating an echocardiogram completed on a patient with suspected KD was stressed with a score greater than or equal to 2.5 reaching a level of significance for the patient’s body size.

Management

• It is still agreed that IVIG is first line therapy.

• For refractory KD (not responsive within 36 hours of first dose IVIG), management is more controversial. Experts on the panel agreed that they would likely provide a second dose of IVIG before thinking about steroids.

• Moderate dose aspirin is just as effective as high dose aspirin in the acute phase of KD.

• For more detailed information regarding the role of corticosteroids in KD, refer to Dr. Carl Galloway’s article in The Hospitalist July 2017 issue.

• A certain subset of patients may benefit from steroids if given early in the disease course, including those who present in shock syndrome. Steroids would still be in conjunction with IVIG treatment.

• Even though the new guidelines recommend a longer course of steroids for those refractory cases of KD in high-risk patients, panel experts are still unsure about evidence behind the claim.

The RAISE study was referenced and indicates there are significantly different outcomes for patients with severe disease placed on steroid therapy in combination with IVIG. In this group of patients, the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms was 23% in the IVIG-only group compared to 3% in the IVIG + steroid group (P less than .0001). This study and a recent Cochrane review that supported use of steroids in KD were completed in a homogeneous population of Japanese children and may not be generalizable to children in the United States.

Hyponatremia has been used as a diagnostic criterion for severe KD in Japanese children and was referenced as an indicator for addition of steroid therapy. Also, studies investigating the necessity of ASA at 80-100 mg/kg/d, a common practice for patients with KD treated in the United States, were compared to medium-dose ASA (30-50 mg/kg/d). There was no clinically significant difference in patient outcome or development of aneurysm formation between these two dosing regimens.

Key takeaways for Pediatric HM

• Diagnosis of classic KD remains unchanged and includes 5 or more days of fever and at least four clinical features (extremity changes, rash, conjunctivitis, oral changes, and cervical lymphadenopathy).

• Infants with fever of 7 days or more without other explanation should be evaluated for KD.

• Echocardiographic findings should be adjusted for body surface area and are significant if Z-score greater than or equal to 2.5.

• Moderate- to high-dose ASA is appropriate as an adjunct to IVIG until the patient is afebrile.

• Steroid therapy (for a total of 14 days) should be considered for high-risk patients.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program. Dr. Hopkins is assistant professor of pediatrics, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – A panel of experts discussed highlights from the 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines at Pediatric Hospital Medicine, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Session

Kawasaki Disease Reconsidered: New AHA Guidelines

Presenters

John Darby, MD, Marietta DeGuzman, MD, Kristen Sexson, MD, PhD, MPH, Stanford Shulman, MD, Nisha Tamaskar, MD

Session summary

For the second year in a row, the session highlighting American Heart Association updates on Kawasaki disease did not disappoint and again attracted a large crowd of community and academic pediatric hospitalists. The newly-revised 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines hot off the press by McCrindle et al. was reviewed in detail.

A secondary theory investigates the tropospheric wind patterns from central Asia and has indicated a possible link to outbreaks of KD in Chile. Despite previous investigation of carpet cleaning and risk for KD, no causal link has been identified.

Experts addressed pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Below are highlights from the new 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guideline Update in conjunction with points from the panel discussion.

Pathophysiology

• Cause is likely to be a common ubiquitous agent that in genetically inclined children will lead to a particular inflammatory response that manifests clinically as KD.

• A new theory about how the “ubiquitous agent” is spread by wind patterns.

Diagnosis

• Confirmed that infants younger than 1 year of age are more difficult to diagnose because they don’t present classically so it must be on the differential.

• The new algorithm makes it clearer that infants with fever for 7 days without symptoms should get lab screening tests for KD.

• Those who have classic symptoms and lab abnormalities consistent with KD but in whom fever is still at 3-4 days may be diagnosed with KD prior to the “5 days of fever rule” because these tend to be a sicker cohort of patients with higher rate of complications. Pretest probability and suspicion for KD must be high to treat before 5 days.

• Importance of the Z-score when evaluating an echocardiogram completed on a patient with suspected KD was stressed with a score greater than or equal to 2.5 reaching a level of significance for the patient’s body size.

Management

• It is still agreed that IVIG is first line therapy.

• For refractory KD (not responsive within 36 hours of first dose IVIG), management is more controversial. Experts on the panel agreed that they would likely provide a second dose of IVIG before thinking about steroids.

• Moderate dose aspirin is just as effective as high dose aspirin in the acute phase of KD.

• For more detailed information regarding the role of corticosteroids in KD, refer to Dr. Carl Galloway’s article in The Hospitalist July 2017 issue.

• A certain subset of patients may benefit from steroids if given early in the disease course, including those who present in shock syndrome. Steroids would still be in conjunction with IVIG treatment.

• Even though the new guidelines recommend a longer course of steroids for those refractory cases of KD in high-risk patients, panel experts are still unsure about evidence behind the claim.

The RAISE study was referenced and indicates there are significantly different outcomes for patients with severe disease placed on steroid therapy in combination with IVIG. In this group of patients, the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms was 23% in the IVIG-only group compared to 3% in the IVIG + steroid group (P less than .0001). This study and a recent Cochrane review that supported use of steroids in KD were completed in a homogeneous population of Japanese children and may not be generalizable to children in the United States.

Hyponatremia has been used as a diagnostic criterion for severe KD in Japanese children and was referenced as an indicator for addition of steroid therapy. Also, studies investigating the necessity of ASA at 80-100 mg/kg/d, a common practice for patients with KD treated in the United States, were compared to medium-dose ASA (30-50 mg/kg/d). There was no clinically significant difference in patient outcome or development of aneurysm formation between these two dosing regimens.

Key takeaways for Pediatric HM

• Diagnosis of classic KD remains unchanged and includes 5 or more days of fever and at least four clinical features (extremity changes, rash, conjunctivitis, oral changes, and cervical lymphadenopathy).

• Infants with fever of 7 days or more without other explanation should be evaluated for KD.

• Echocardiographic findings should be adjusted for body surface area and are significant if Z-score greater than or equal to 2.5.

• Moderate- to high-dose ASA is appropriate as an adjunct to IVIG until the patient is afebrile.

• Steroid therapy (for a total of 14 days) should be considered for high-risk patients.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program. Dr. Hopkins is assistant professor of pediatrics, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – A panel of experts discussed highlights from the 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines at Pediatric Hospital Medicine, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Session

Kawasaki Disease Reconsidered: New AHA Guidelines

Presenters

John Darby, MD, Marietta DeGuzman, MD, Kristen Sexson, MD, PhD, MPH, Stanford Shulman, MD, Nisha Tamaskar, MD

Session summary

For the second year in a row, the session highlighting American Heart Association updates on Kawasaki disease did not disappoint and again attracted a large crowd of community and academic pediatric hospitalists. The newly-revised 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guidelines hot off the press by McCrindle et al. was reviewed in detail.

A secondary theory investigates the tropospheric wind patterns from central Asia and has indicated a possible link to outbreaks of KD in Chile. Despite previous investigation of carpet cleaning and risk for KD, no causal link has been identified.

Experts addressed pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Below are highlights from the new 2017 AHA Kawasaki Guideline Update in conjunction with points from the panel discussion.

Pathophysiology

• Cause is likely to be a common ubiquitous agent that in genetically inclined children will lead to a particular inflammatory response that manifests clinically as KD.

• A new theory about how the “ubiquitous agent” is spread by wind patterns.

Diagnosis

• Confirmed that infants younger than 1 year of age are more difficult to diagnose because they don’t present classically so it must be on the differential.

• The new algorithm makes it clearer that infants with fever for 7 days without symptoms should get lab screening tests for KD.

• Those who have classic symptoms and lab abnormalities consistent with KD but in whom fever is still at 3-4 days may be diagnosed with KD prior to the “5 days of fever rule” because these tend to be a sicker cohort of patients with higher rate of complications. Pretest probability and suspicion for KD must be high to treat before 5 days.

• Importance of the Z-score when evaluating an echocardiogram completed on a patient with suspected KD was stressed with a score greater than or equal to 2.5 reaching a level of significance for the patient’s body size.

Management

• It is still agreed that IVIG is first line therapy.

• For refractory KD (not responsive within 36 hours of first dose IVIG), management is more controversial. Experts on the panel agreed that they would likely provide a second dose of IVIG before thinking about steroids.

• Moderate dose aspirin is just as effective as high dose aspirin in the acute phase of KD.

• For more detailed information regarding the role of corticosteroids in KD, refer to Dr. Carl Galloway’s article in The Hospitalist July 2017 issue.

• A certain subset of patients may benefit from steroids if given early in the disease course, including those who present in shock syndrome. Steroids would still be in conjunction with IVIG treatment.

• Even though the new guidelines recommend a longer course of steroids for those refractory cases of KD in high-risk patients, panel experts are still unsure about evidence behind the claim.

The RAISE study was referenced and indicates there are significantly different outcomes for patients with severe disease placed on steroid therapy in combination with IVIG. In this group of patients, the incidence of coronary artery aneurysms was 23% in the IVIG-only group compared to 3% in the IVIG + steroid group (P less than .0001). This study and a recent Cochrane review that supported use of steroids in KD were completed in a homogeneous population of Japanese children and may not be generalizable to children in the United States.

Hyponatremia has been used as a diagnostic criterion for severe KD in Japanese children and was referenced as an indicator for addition of steroid therapy. Also, studies investigating the necessity of ASA at 80-100 mg/kg/d, a common practice for patients with KD treated in the United States, were compared to medium-dose ASA (30-50 mg/kg/d). There was no clinically significant difference in patient outcome or development of aneurysm formation between these two dosing regimens.

Key takeaways for Pediatric HM

• Diagnosis of classic KD remains unchanged and includes 5 or more days of fever and at least four clinical features (extremity changes, rash, conjunctivitis, oral changes, and cervical lymphadenopathy).

• Infants with fever of 7 days or more without other explanation should be evaluated for KD.

• Echocardiographic findings should be adjusted for body surface area and are significant if Z-score greater than or equal to 2.5.

• Moderate- to high-dose ASA is appropriate as an adjunct to IVIG until the patient is afebrile.

• Steroid therapy (for a total of 14 days) should be considered for high-risk patients.

Dr. King is associate program director, University of Minnesota Pediatric Residency Program. Dr. Hopkins is assistant professor of pediatrics, Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital.

At PHM 2017

Necrotic Ulcer on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Cryptococcosis

Histopathologic examination of a 3-mm punch biopsy showed a diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate with necrosis and subcutaneous tissue with round yeast surrounded by a prominent halo staining bright red with mucicarmine, representing a thick mucinous capsule (Figure). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff stains also demonstrated fungal spores morphologically. Cerebrospinal fluid culture grew Cryptococcus neoformans, and cryptococcal antigen titers were positive in both serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples (>1:4096). The patient had autolytic debridement of the ulcer after completing a 4-week induction course of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral flucytosine. He was transitioned to oral fluconazole for the consolidation phase of treatment.

Cryptococcus is an opportunistic basidiomycetous yeast with worldwide distribution and 2 primary pathogenic species in humans: C neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. It is associated with bird feces, composted food, and decayed wood.1,2 A predilection toward an immunosuppressed host is recognized in 70% to 90% of the infections caused by C neoformans; however, C gattii commonly affects individuals with apparently intact immune systems.1,3 Risk factors for infection include advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection, solid organ transplantation, chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease, hematological malignancy, and underlying genetic susceptibility.1,2

Initial exposure is through the respiratory tract with formation of latent reservoirs in the pulmonary lymph nodes with subsequent reactivation that can result in hematogenous dissemination.1,2 Cutaneous involvement was described in 108 patients (5%) in a large review of 1974 cases in France.4 Among those with cutaneous involvement, disseminated disease was diagnosed in 80 cases (74%), and 28 cases (26%) were considered primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis typically presents as a single lesion, predominantly on the hand, with whitlow and more rarely with extensive cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.4 In disseminated cutaneous disease, there is no pathognomonic single lesion; however, it is commonly associated with multiple cutaneous lesions predominantly involving the head and neck. Plaques, abscesses, nodules, and pustular or umbilicated papules have been reported.1,5 There are few case reports that describe a single isolated necrotic ulcer with disseminated disease similar to our presented case, and more typically the necrotic ulcer is seen in transplanted patients.6 The differential diagnosis of a necrotic thigh ulcer includes pseudomonal ecthyma gangrenosum, cutaneous anthrax and aspergillosis, fusariosis, and a bite from the brown recluse spider.7 Our patient had an increased susceptibility to infection from his ongoing chemotherapy, a risk previously described in oncology patients with cell-mediated immunosuppression.8

Management for disseminated cryptococcosis is a 3-phase therapy including induction with intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine for a minimum of 2 weeks, with consolidation and maintenance phases both with oral fluconazole for a length depending on underlying immunosuppression.9

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

- Chen SC, Meyer W, Sorrell TC. Cryptococcus gattii infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:980-1024.

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis, and therapy [published online November 25, 2016]. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13-24.

- Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34.

- Neuville S, Dromer F, Morin O, et al; French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis: a distinct clinical entity [published online January 17, 2003]. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:337-347.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous cryptococcus infection and AIDS: report of 12 cases and review of the literature. JAMA Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Sun HY, Alexander BD, Lortholary O, et al. Cutaneous cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Med Mycol. 2010;48:785-791.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, et al. Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 2012.

- Korfel A, Menssen HD, Schwartz S, et al. Cryptococcosis in Hodgkin's disease: description of two cases and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 1998;76:283-286.

- Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291-322.

A 29-year-old man with a history of acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted for acute encephalopathy and a necrotic ulcer on the right thigh of 2 weeks' duration. He had received chemotherapy with pegaspargase and vincristine 6 weeks prior to admission. He reported headache with nausea and vomiting of 2 weeks' duration and had sustained a fall in the bathtub a week prior that initially resulted in a right thigh abrasion. He denied recent travel, unusual food consumption, animal exposure, exposure to sick persons, and alcohol or other drug use. On examination the patient was alert but was not oriented to person, place, or time. A 10.2 ×10-cm necrotic ulcer with surrounding mild erythema and tenderness was noted on the right inner thigh.

Reducing the Burden of Cirrhosis and Hepatic Encephalopathy

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

Topics include:

- Overview of HE

- Early Identification and Management

- An Option for HE Management

Dr. William Ford, MD, SFHM

Regional Medical Director

Clinical Associate Professor

of Medicine

Abington, Jefferson Health

Philadelphia, PA

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

XIF.0129.USA.17

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

Topics include:

- Overview of HE

- Early Identification and Management

- An Option for HE Management

Dr. William Ford, MD, SFHM

Regional Medical Director

Clinical Associate Professor

of Medicine

Abington, Jefferson Health

Philadelphia, PA

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

XIF.0129.USA.17

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

Topics include:

- Overview of HE

- Early Identification and Management

- An Option for HE Management

Dr. William Ford, MD, SFHM

Regional Medical Director

Clinical Associate Professor

of Medicine

Abington, Jefferson Health

Philadelphia, PA

Click Here to Read the Supplement.

XIF.0129.USA.17

Wearable Health Device Dermatitis: A Case of Acrylate-Related Contact Allergy

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

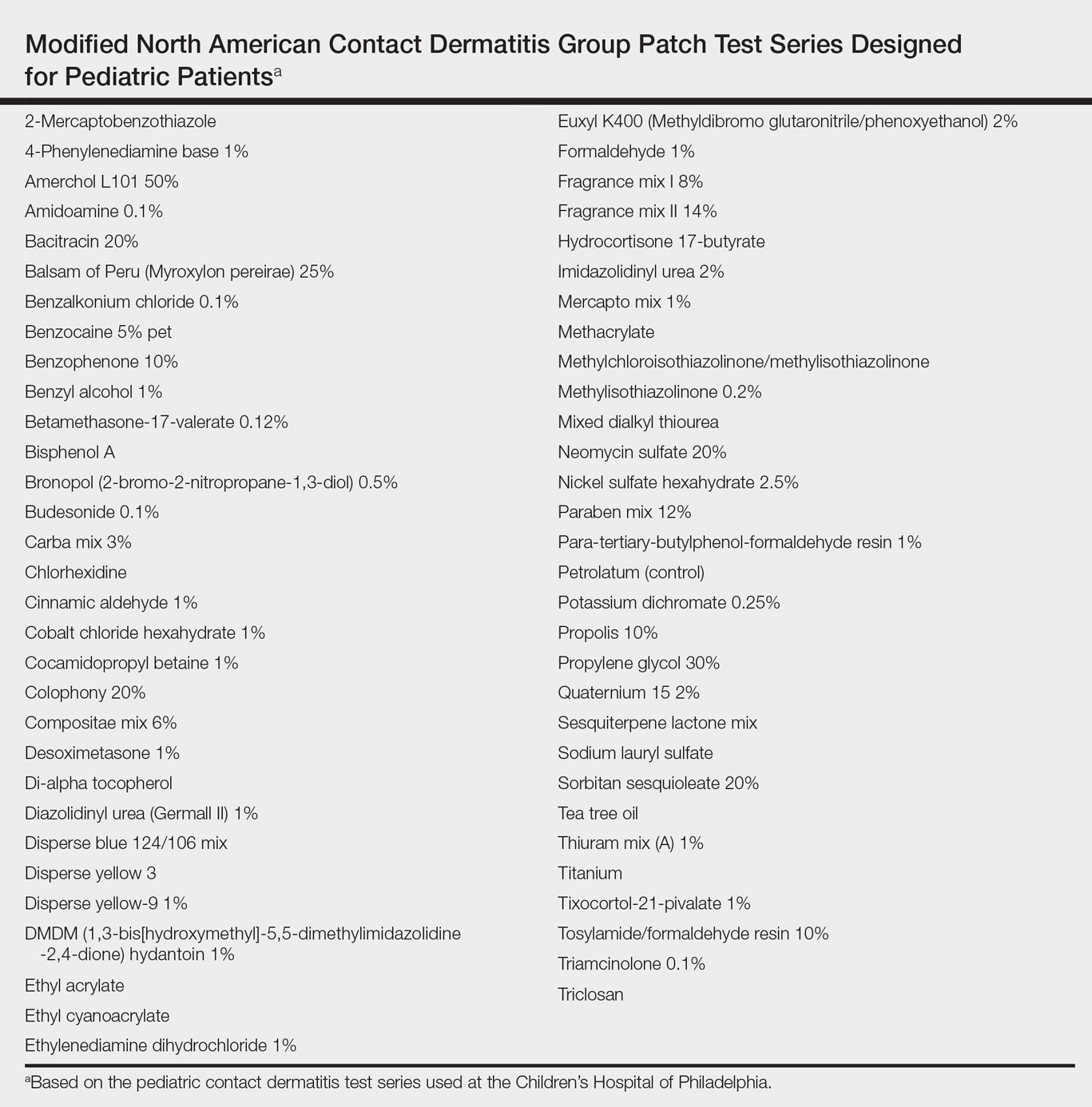

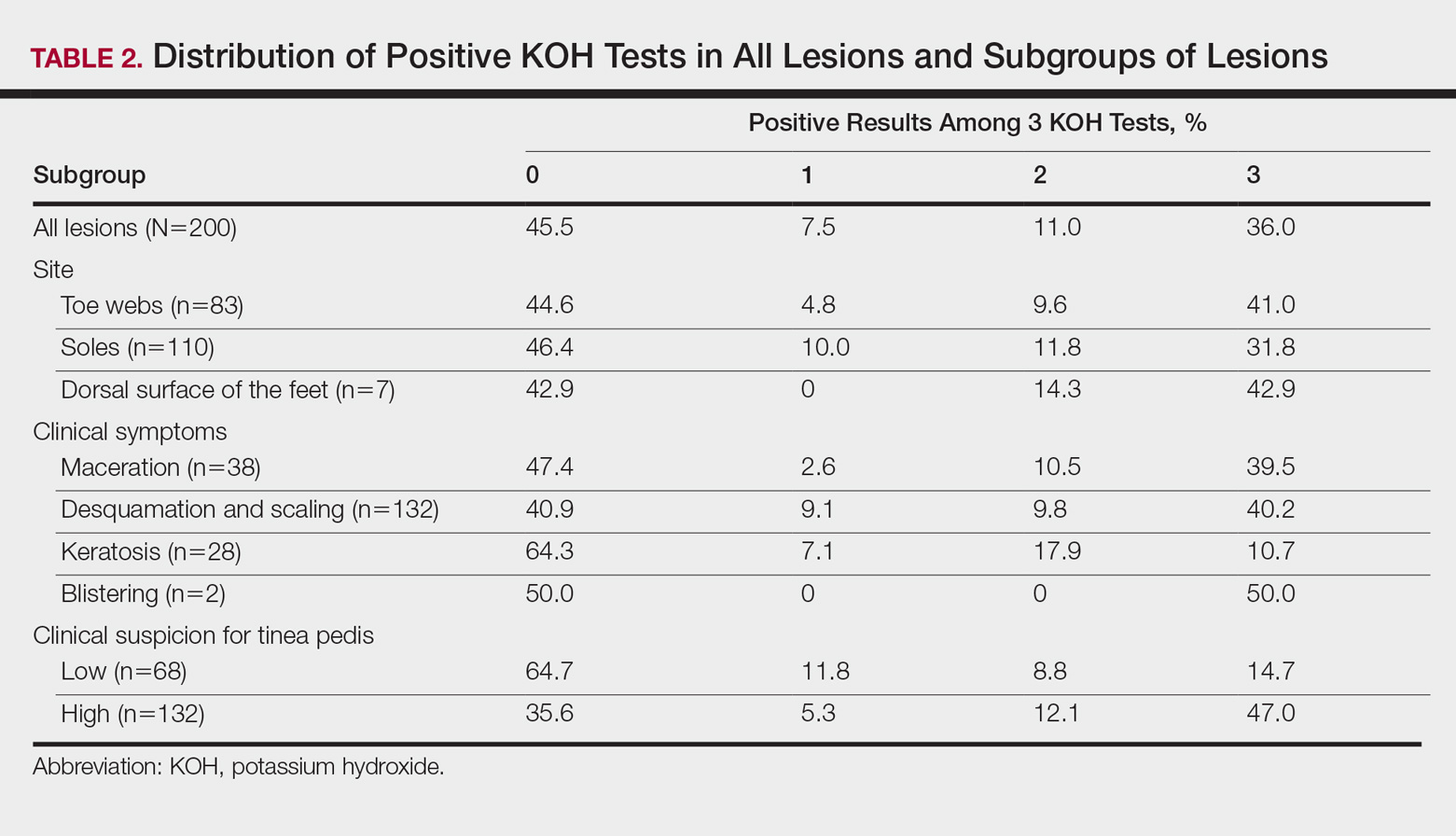

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

Mobile health devices enable patients and clinicians to monitor the type, quantity, and quality of everyday activities and hold the promise of improving patient health and health care practices.1 In 2013, 75% of surveyed consumers in the United States owned a fitness technology product, either a dedicated fitness device, application, or portable blood pressure monitor.2 Ownership of dedicated wearable fitness devices among consumers in the United States increased from 3% in 2012 to 9% in 2013. The immense popularity of wearable fitness devices is evident in the trajectory of their reported sales, which increased from $43 million in 2009 to $854 million in 2013.2 Recognizing that “widespread adoption and use of mobile technologies is opening new and innovative ways to improve health,”3 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ruled that “[technologies] that can pose a greater risk to patients will require FDA review.” One popular class of mobile technologies—activity and sleep sensors—falls outside the FDA’s regulatory guidance. To enable continuous monitoring, these sensors often are embedded into wearable devices.

Reports in the media have documented skin rashes arising in conjunction with use of one type of device,4 which may be related to nickel contact allergy, and the manufacturer has reported that the metal housing consists of surgical stainless steel that is known to contain nickel. We report a complication related to continuous use of an unregulated, commercially available, watchlike wearable sensor that was linked not to nickel but to an acrylate-containing component.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 52-year-old woman with no history of contact allergy presented with an intensely itchy eruption involving the left wrist arising 4 days after continuous use of a new watchlike wearable fitness sensor. By day 11, the eruption evolved into a well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaque at the location where the device’s rechargeable battery metal housing came into contact with skin (Figure 1).

Dimethylglyoxime testing of the metal housing and clips was negative, but testing of contacts within the housing was positive for nickel (Figure 2). Epicutaneous patch testing of the patient using a modified North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test series (Table) demonstrated no reaction to nickel, instead showing a strong positive (2+) reaction at 48 and 72 hours to methyl methacrylate 2% and a positive (1+) reaction at 96 hours to ethyl acrylate 0.1% (Figure 3).

Comment

Acrylates are used as adhesives to bond metal to plastic and as part of lithium ion polymer batteries, presumably similar to the one used in this device.5 Our patient had a history of using acrylic nail polish, which may have been a source of prior sensitization. Exposure to sweat or other moisture could theoretically dissolve such a water-soluble polymer,6 allowing for skin contact. Other acrylate polymers have been reported to break down slowly in contact with water, leading to contact sensitization to the monomer.7 The manufacturer of the device was contacted for additional information but declined to provide specific details regarding the device’s composition (personal communication, January 2014).

Although not considered toxic,8 acrylate was named Allergen of the Year in 2012 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.9-11 Nickel might be a source of allergy for some other patients who wear mobile health devices, but we concluded that this particular patient developed allergic contact dermatitis from prolonged exposure to low levels of methyl methacrylate or another acrylate due to gradual breakdown of the acrylate polymer used in the rechargeable battery housing for this wearable health device.

Given the FDA’s tailored risk approach to regulation, many wearable sensors that may contain potential contact allergens such as nickel and acrylates do not fall under the FDA regulatory framework. This case should alert physicians to the lack of regulatory oversight for many mobile technologies. They should consider a screening history for contact allergens before recommending wearable sensors and broader testing for contact allergens should exposed patients develop reactions. Future wearable sensor materials and designs should minimize exposure to allergens given prolonged contact with continuous use. In the absence of regulation, manufacturers of these devices should consider due care testing prior to commercialization.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Alexander S. Rattner, PhD (State College, Pennsylvania), who provided his engineering expertise and insight during conversations with the authors.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

- Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:788-798.

- Consumer interest in purchasing wearable fitness devices in 2014 quadruples, according to CEA Study [press release]. Arlington, VA: Consumer Electronics Association; December 11, 2013.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mobile medical applications. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/digitalhealth/mobilemedicalapplications/default.htm. Updated September 22, 2015. Accessed July 26, 2017.

- Northrup L. Fitbit Force is an amazing device, except for my contact dermatitis. Consumerist website. http://consumerist.com/2014/01/13/fitbit-force-is-an-amazing-device-except-for-my-contact-dermatitis/. Published January 13, 2014. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Stern B. Inside Fitbit Force. Adafruit website. http://learn.adafruit.com/fitbit-force-teardown/inside-fitbit-force. Published December 11, 2013. Updated May 4, 2015. Accessed January 12, 2017.

- Pemberton MA, Lohmann BS. Risk assessment of residual monomer migrating from acrylic polymers and causing allergic contact dermatitis during normal handling and use. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;69:467-475.

- Guin JD, Baas K, Nelson-Adesokan P. Contact sensitization to cyanoacrylate adhesive as a cause of severe onychodystrophy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:31-36.

- Zondlo Fiume M. Final report on the safety assessment of Acrylates Copolymer and 33 related cosmetic ingredients. Int J Toxicol. 2002;21(suppl 3):1-50.

- Sasseville D. Acrylates. Dermatitis. 2012;23:3-5.

- Bowen C, Bidinger J, Hivnor C, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Cutis. 2014;94:183-186.

- Spencer A, Gazzani P, Thompson DA. Acrylate and methacrylate contact allergy and allergic contact disease: a 13-year review [published online July 11, 2016]. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:157-164.

Practice Points

- Mobile wearable health devices are likely to become an important potential source of contact sensitization as their use increases given their often prolonged contact time with the skin.

- Mobile wearable health devices may pose a risk for allergic contact dermatitis as a result of a variety of components that come into contact with the skin, including but not limited to metals, rubber components, adhesives, and dyes.

What’s Eating You? Minute Brown Scavenger Beetle

Delusional infestation is the fixed false belief of skin infestation with a pathogen. Patients will often bring “proof” of their infestation to their visit to a physician. The presentation of a specimen was previously referred to by several names that reflected the receptacle that the patient utilized to bring the specimen (eg, a baggie or matchbox), but now the more encompassing term specimen sign is employed.1 Establishing rapport with the patient is critically important in the treatment of delusional infestation. Examining the specimen samples brought by the patient is a simple manner of communicating to a patient that the clinician is empathetic to and respectful of his/her concerns.2,3 The specimens often consist of dirt, dust, debris, fibers, and skin flakes and fragments, but they also have been reported to contain flies and insect parts.4,5 In our case, the patient captured a minute brown scavenger beetle with adhesive tape.

Case Report

A woman in her mid-30s with a history of generalized anxiety disorder presented to the dermatology clinic with a concern of bugs infesting her skin. The symptoms occurred just after she moved into a new home with her family approximately 4 months prior to presentation. She felt the home was not cleaned properly, but they could not afford to move. She reported a crawling sensation that she identified as bugs biting her all over her body. Prior to presentation in the dermatology clinic, she and her family were treated by primary care for scabies 3 times with permethrin cream, and she was prescribed 1 course of oral ivermectin. She reported seeing bugs all over her house, which led her to clean her home and clothing many times. She was more concerned now because she thought her 2 children also were starting to be affected.

Physical examination revealed pressured speech, and the patient became tearful several times. The skin demonstrated several excoriations in various stages of healing on the breasts, legs, and upper back, as well as small scars in the same distribution. She brought several specimens stuck to clear tape to the visit. Examination of the specimens revealed fabric fibers; various debris; and a small, brown, 6-legged beetle with punctate indentations in rows along the wing covers (Figure). The head was narrower than the thorax, which was narrower than the abdomen.

We diagnosed the patient with a delusional infestation and discussed the beetle that we saw when examining the specimen the patient brought to the clinic. We provided reassurance that the minute brown scavenger beetle is not pathogenic and was present incidentally. Thus far, the patient has been resistant to initiating specific therapy for the delusional infestation, such as risperidone, olanzapine, or pimozide. We co

Comment

Minute brown scavenger beetles are arthropod members of the family Latridiidae. They also are commonly referred to as plaster or mold beetles. They are small (0.8–3.0 mm) and can be found in moist environments such as dead and rotting foliage, bird’s nests, debris, moist wallpaper/plaster, and stored products. They feed exclusively on fungus, such as mold and mildew, and pose no threat to humans.6 It is important for clinicians to recognize the appearance of the minute brown scavenger beetle so as not to mistake it for a pathogenic arthropod in patients presenting with delusional parasitosis.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Delusional infestation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:690-732.

- Heller MM, Wong JW, Lee ES, et al. Delusional infestations: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:775-783.

- Patel V, Koo JY. Delusions of parasitosis; suggested dialogue between dermatologist and patient. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:456-460.

- Zomer SF, De Wit RF, Van Bronswijk JE, et al. Delusions of parasitosis. a psychiatric disorder to be treated by dermatologists? an analysis of 33 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:1030-1032.

- Freudenmann RW, Kölle M, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the matchbox sign revisited: the international perspective. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:517-519.

- Bousquet Y. Beetles Associated With Stored Products in Canada: An identification Guide. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Governement Publishing Centre; 1990.

Delusional infestation is the fixed false belief of skin infestation with a pathogen. Patients will often bring “proof” of their infestation to their visit to a physician. The presentation of a specimen was previously referred to by several names that reflected the receptacle that the patient utilized to bring the specimen (eg, a baggie or matchbox), but now the more encompassing term specimen sign is employed.1 Establishing rapport with the patient is critically important in the treatment of delusional infestation. Examining the specimen samples brought by the patient is a simple manner of communicating to a patient that the clinician is empathetic to and respectful of his/her concerns.2,3 The specimens often consist of dirt, dust, debris, fibers, and skin flakes and fragments, but they also have been reported to contain flies and insect parts.4,5 In our case, the patient captured a minute brown scavenger beetle with adhesive tape.

Case Report

A woman in her mid-30s with a history of generalized anxiety disorder presented to the dermatology clinic with a concern of bugs infesting her skin. The symptoms occurred just after she moved into a new home with her family approximately 4 months prior to presentation. She felt the home was not cleaned properly, but they could not afford to move. She reported a crawling sensation that she identified as bugs biting her all over her body. Prior to presentation in the dermatology clinic, she and her family were treated by primary care for scabies 3 times with permethrin cream, and she was prescribed 1 course of oral ivermectin. She reported seeing bugs all over her house, which led her to clean her home and clothing many times. She was more concerned now because she thought her 2 children also were starting to be affected.

Physical examination revealed pressured speech, and the patient became tearful several times. The skin demonstrated several excoriations in various stages of healing on the breasts, legs, and upper back, as well as small scars in the same distribution. She brought several specimens stuck to clear tape to the visit. Examination of the specimens revealed fabric fibers; various debris; and a small, brown, 6-legged beetle with punctate indentations in rows along the wing covers (Figure). The head was narrower than the thorax, which was narrower than the abdomen.

We diagnosed the patient with a delusional infestation and discussed the beetle that we saw when examining the specimen the patient brought to the clinic. We provided reassurance that the minute brown scavenger beetle is not pathogenic and was present incidentally. Thus far, the patient has been resistant to initiating specific therapy for the delusional infestation, such as risperidone, olanzapine, or pimozide. We co

Comment

Minute brown scavenger beetles are arthropod members of the family Latridiidae. They also are commonly referred to as plaster or mold beetles. They are small (0.8–3.0 mm) and can be found in moist environments such as dead and rotting foliage, bird’s nests, debris, moist wallpaper/plaster, and stored products. They feed exclusively on fungus, such as mold and mildew, and pose no threat to humans.6 It is important for clinicians to recognize the appearance of the minute brown scavenger beetle so as not to mistake it for a pathogenic arthropod in patients presenting with delusional parasitosis.

Delusional infestation is the fixed false belief of skin infestation with a pathogen. Patients will often bring “proof” of their infestation to their visit to a physician. The presentation of a specimen was previously referred to by several names that reflected the receptacle that the patient utilized to bring the specimen (eg, a baggie or matchbox), but now the more encompassing term specimen sign is employed.1 Establishing rapport with the patient is critically important in the treatment of delusional infestation. Examining the specimen samples brought by the patient is a simple manner of communicating to a patient that the clinician is empathetic to and respectful of his/her concerns.2,3 The specimens often consist of dirt, dust, debris, fibers, and skin flakes and fragments, but they also have been reported to contain flies and insect parts.4,5 In our case, the patient captured a minute brown scavenger beetle with adhesive tape.

Case Report

A woman in her mid-30s with a history of generalized anxiety disorder presented to the dermatology clinic with a concern of bugs infesting her skin. The symptoms occurred just after she moved into a new home with her family approximately 4 months prior to presentation. She felt the home was not cleaned properly, but they could not afford to move. She reported a crawling sensation that she identified as bugs biting her all over her body. Prior to presentation in the dermatology clinic, she and her family were treated by primary care for scabies 3 times with permethrin cream, and she was prescribed 1 course of oral ivermectin. She reported seeing bugs all over her house, which led her to clean her home and clothing many times. She was more concerned now because she thought her 2 children also were starting to be affected.

Physical examination revealed pressured speech, and the patient became tearful several times. The skin demonstrated several excoriations in various stages of healing on the breasts, legs, and upper back, as well as small scars in the same distribution. She brought several specimens stuck to clear tape to the visit. Examination of the specimens revealed fabric fibers; various debris; and a small, brown, 6-legged beetle with punctate indentations in rows along the wing covers (Figure). The head was narrower than the thorax, which was narrower than the abdomen.

We diagnosed the patient with a delusional infestation and discussed the beetle that we saw when examining the specimen the patient brought to the clinic. We provided reassurance that the minute brown scavenger beetle is not pathogenic and was present incidentally. Thus far, the patient has been resistant to initiating specific therapy for the delusional infestation, such as risperidone, olanzapine, or pimozide. We co

Comment

Minute brown scavenger beetles are arthropod members of the family Latridiidae. They also are commonly referred to as plaster or mold beetles. They are small (0.8–3.0 mm) and can be found in moist environments such as dead and rotting foliage, bird’s nests, debris, moist wallpaper/plaster, and stored products. They feed exclusively on fungus, such as mold and mildew, and pose no threat to humans.6 It is important for clinicians to recognize the appearance of the minute brown scavenger beetle so as not to mistake it for a pathogenic arthropod in patients presenting with delusional parasitosis.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Delusional infestation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:690-732.

- Heller MM, Wong JW, Lee ES, et al. Delusional infestations: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:775-783.

- Patel V, Koo JY. Delusions of parasitosis; suggested dialogue between dermatologist and patient. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:456-460.

- Zomer SF, De Wit RF, Van Bronswijk JE, et al. Delusions of parasitosis. a psychiatric disorder to be treated by dermatologists? an analysis of 33 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:1030-1032.

- Freudenmann RW, Kölle M, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the matchbox sign revisited: the international perspective. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:517-519.

- Bousquet Y. Beetles Associated With Stored Products in Canada: An identification Guide. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Governement Publishing Centre; 1990.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Delusional infestation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:690-732.

- Heller MM, Wong JW, Lee ES, et al. Delusional infestations: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:775-783.

- Patel V, Koo JY. Delusions of parasitosis; suggested dialogue between dermatologist and patient. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:456-460.

- Zomer SF, De Wit RF, Van Bronswijk JE, et al. Delusions of parasitosis. a psychiatric disorder to be treated by dermatologists? an analysis of 33 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:1030-1032.

- Freudenmann RW, Kölle M, Schönfeldt-Lecuona C, et al. Delusional parasitosis and the matchbox sign revisited: the international perspective. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:517-519.

- Bousquet Y. Beetles Associated With Stored Products in Canada: An identification Guide. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Governement Publishing Centre; 1990.

Practice Points

- Examining the specimens brought by a patient with delusional infestation is important for the therapeutic relationship.

- Clinicians must be able to recognize nonpathogenic insects that may incidentally be present in the specimen such as the minute brown scavenger beetle.

Effect Of Inpatient Rehab Vs. Home-Based Program For TKA

Title: Inpatient rehabilitation does not improve mobility after total knee arthroplasty versus a monitored home-based program.

Clinical Question: Does initial treatment in an inpatient rehabilitation facility offer greater improvements in mobility when added to a monitored home-based program after undergoing total knee arthroplasty?

Background: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is common and postsurgical care varies. No randomized controlled trials have compared inpatient rehabilitation to monitored home-based programs.

Study Design: Multicenter, two intervention groups in parallel, randomized controlled trial with a third observational group.

Synopsis: 165 patients who underwent unilateral TKA were randomized to inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program vs. a home-based program only. A separate observation group (patients who chose home-based program) was included in the analysis of primary outcome. Primary outcome was functional mobility at 26 weeks as measured by walking distance via the 6-minute walk test. All 165 patients were included in an intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was no different among the two randomized groups (adjusted mean difference with imputation, –1.01; 95% CI, –25.56 to 23.55). The per protocol analysis of the primary outcome yielded similar results; nonadherent patients were excluded from the per protocol analysis so the sample size was smaller. There were no between-group differences in the primary outcome when the home-based program was compared to the observation group. Secondary outcomes included patient reported and observer assessed outcomes in function and quality of life. The most significant limitation was that these results are generalizable only to patients considered appropriate for discharge home.

Bottom Line: In total knee arthroplasty patients appropriate for discharge home, inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program did not improve mobility as compared with a monitored home-based program alone.

Citation: Buhagiar MA, Naylor JM, Harris IA, et al. Effect of inpatient rehabilitation vs. a monitored home-based program on mobility in patients with total knee arthroplasty, the HIHO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1037-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1224.

Dr. Burns is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico.

Title: Inpatient rehabilitation does not improve mobility after total knee arthroplasty versus a monitored home-based program.

Clinical Question: Does initial treatment in an inpatient rehabilitation facility offer greater improvements in mobility when added to a monitored home-based program after undergoing total knee arthroplasty?

Background: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is common and postsurgical care varies. No randomized controlled trials have compared inpatient rehabilitation to monitored home-based programs.

Study Design: Multicenter, two intervention groups in parallel, randomized controlled trial with a third observational group.

Synopsis: 165 patients who underwent unilateral TKA were randomized to inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program vs. a home-based program only. A separate observation group (patients who chose home-based program) was included in the analysis of primary outcome. Primary outcome was functional mobility at 26 weeks as measured by walking distance via the 6-minute walk test. All 165 patients were included in an intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was no different among the two randomized groups (adjusted mean difference with imputation, –1.01; 95% CI, –25.56 to 23.55). The per protocol analysis of the primary outcome yielded similar results; nonadherent patients were excluded from the per protocol analysis so the sample size was smaller. There were no between-group differences in the primary outcome when the home-based program was compared to the observation group. Secondary outcomes included patient reported and observer assessed outcomes in function and quality of life. The most significant limitation was that these results are generalizable only to patients considered appropriate for discharge home.

Bottom Line: In total knee arthroplasty patients appropriate for discharge home, inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program did not improve mobility as compared with a monitored home-based program alone.

Citation: Buhagiar MA, Naylor JM, Harris IA, et al. Effect of inpatient rehabilitation vs. a monitored home-based program on mobility in patients with total knee arthroplasty, the HIHO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1037-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1224.

Dr. Burns is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico.

Title: Inpatient rehabilitation does not improve mobility after total knee arthroplasty versus a monitored home-based program.

Clinical Question: Does initial treatment in an inpatient rehabilitation facility offer greater improvements in mobility when added to a monitored home-based program after undergoing total knee arthroplasty?

Background: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is common and postsurgical care varies. No randomized controlled trials have compared inpatient rehabilitation to monitored home-based programs.

Study Design: Multicenter, two intervention groups in parallel, randomized controlled trial with a third observational group.

Synopsis: 165 patients who underwent unilateral TKA were randomized to inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program vs. a home-based program only. A separate observation group (patients who chose home-based program) was included in the analysis of primary outcome. Primary outcome was functional mobility at 26 weeks as measured by walking distance via the 6-minute walk test. All 165 patients were included in an intention-to-treat analysis. The primary outcome was no different among the two randomized groups (adjusted mean difference with imputation, –1.01; 95% CI, –25.56 to 23.55). The per protocol analysis of the primary outcome yielded similar results; nonadherent patients were excluded from the per protocol analysis so the sample size was smaller. There were no between-group differences in the primary outcome when the home-based program was compared to the observation group. Secondary outcomes included patient reported and observer assessed outcomes in function and quality of life. The most significant limitation was that these results are generalizable only to patients considered appropriate for discharge home.

Bottom Line: In total knee arthroplasty patients appropriate for discharge home, inpatient rehabilitation followed by a home-based program did not improve mobility as compared with a monitored home-based program alone.

Citation: Buhagiar MA, Naylor JM, Harris IA, et al. Effect of inpatient rehabilitation vs. a monitored home-based program on mobility in patients with total knee arthroplasty, the HIHO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1037-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1224.

Dr. Burns is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine at the University of New Mexico.

Successive Potassium Hydroxide Testing for Improved Diagnosis of Tinea Pedis

The gold standard for diagnosing dermatophytosis is the use of direct microscopic examination together with fungal culture.1 However, in the last 2 decades, molecular techniques that currently are available worldwide have improved the diagnosis procedure.2,3 In the practice of dermatology, potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing is a commonly used method for the diagnosis of superficial fungal infections.4 The sensitivity and specificity of KOH testing in patients with tinea pedis have been reported as 73.3% and 42.5%, respectively.5 Repetition of this test after an initial negative test result is recommended if the clinical picture strongly suggests a fungal infection.6,7 Alternatively, several repetitions of direct microscopic examinations also have been proposed for detecting other microorganisms. For example, 3 negative sputum smears traditionally are recommended to exclude a diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis.8 However, after numerous investigations in various regions of the world, the World Health Organization reduced the recommended number of these specimens from 3 to 2 in 2007.9

The literature suggests that successive mycological tests, both with direct microscopy and fungal cultures, improve the diagnosis of onychomycosis.1,10,11 Therefore, if such investigations are increased in number, recommendations for successive mycological tests may be more reliable. In the current study, we aimed to investigate the value of successive KOH testing in the management of patients with clinically suspected tinea pedis.

Methods

Patients and Clinical Evaluation

One hundred thirty-five consecutive patients (63 male; 72 female) with clinical symptoms suggestive of intertriginous, vesiculobullous, and/or moccasin-type tinea pedis were enrolled in this prospective study. The mean age (SD) of patients was 45.9 (14.7) years (range, 11–77 years). Almost exclusively, the clinical symptoms suggestive of tinea pedis were desquamation or maceration in the toe webs, blistering lesions on the soles, and diffuse or patchy scaling or keratosis on the soles. A single dermatologist (B.F.K.) clinically evaluated the patients and found only 1 region showing different patterns suggestive of tinea pedis in 72 patients, 2 regions in 61 patients, and 3 regions in 2 patients. Therefore, 200 lesions from the 135 patients were chosen for the KOH test. The dermatologist recorded her level of suspicion for a fungal infection as low or high for each lesion, depending on the absence or presence of signs (eg, unilateral involvement, a well-defined border). None of the patients had used topical or systemic antifungal therapy for at least 1 month prior to the study.12

Clinical Sampling and Direct Microscopic Examination

The dermatologist took 3 samples of skin scrapings from each of the 200 lesions. All 3 samples from a given lesion were obtained from sites with the same clinical symptoms in a single session. Special attention was paid to samples from the active advancing borders of the lesions and the roofs of blisters if they were present.13 Upon completion of every 15 samples from every 5 lesions, the dermatologist randomized the order of the samples (https://www.random.org/). She then gave the samples, without the identities of the patients or any clinical information, to an experienced laboratory technician for direct microscopic examination. The technician prepared and examined the samples as described elsewhere5,7,14 and recorded the results as positive if hyphal elements were present or negative if they were not. The study was reviewed and approved by the Çukurova University Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (Adana, Turkey). Informed consent was obtained from each patient or from his/her guardian(s) prior to initiating the study.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the χ2 test in the SPSS software version 20.0. McNemar test was used for analysis of the paired data.

Results

Among the 135 patients, lesions were suggestive of the intertriginous type of tinea pedis in 24 patients, moccasin type in 50 patients, and both intertriginous and moccasin type in 58 patients. Among the remaining 3 patients, 1 had lesions suggestive of the vesiculobullous type, and another patient had both the vesiculobullous and intertriginous types; the last patient demonstrated lesions that were inconsistent with any of these 3 subtypes of tinea pedis, and a well-defined eczematous plaque was observed on the dorsal surface of the patient’s left foot.

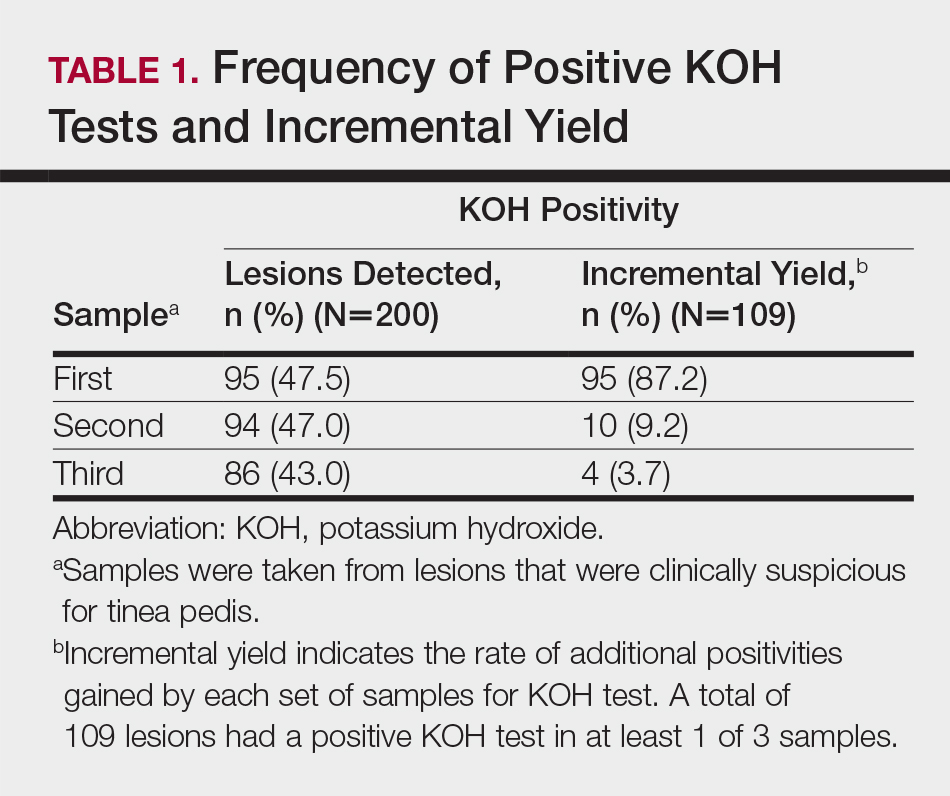

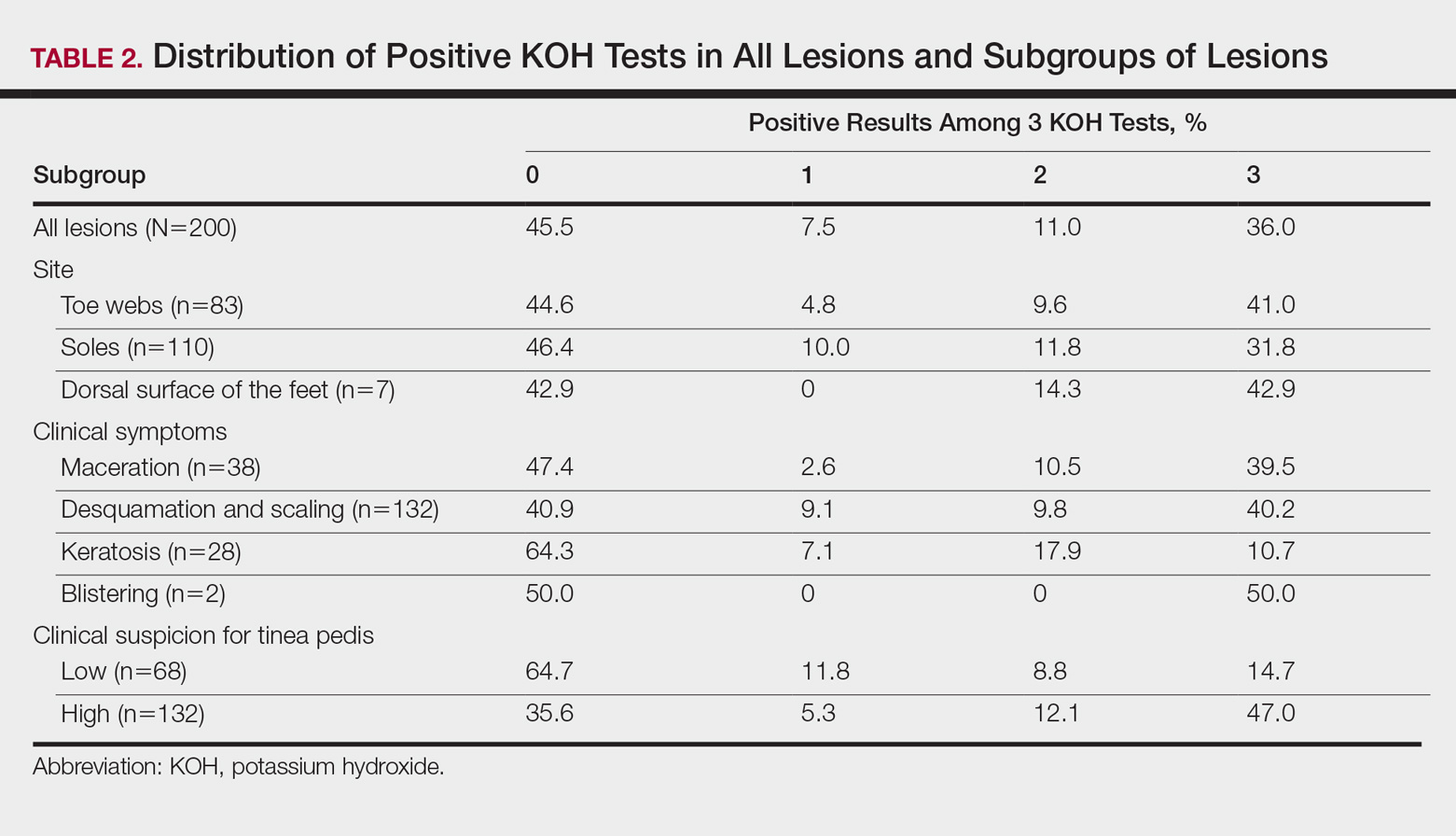

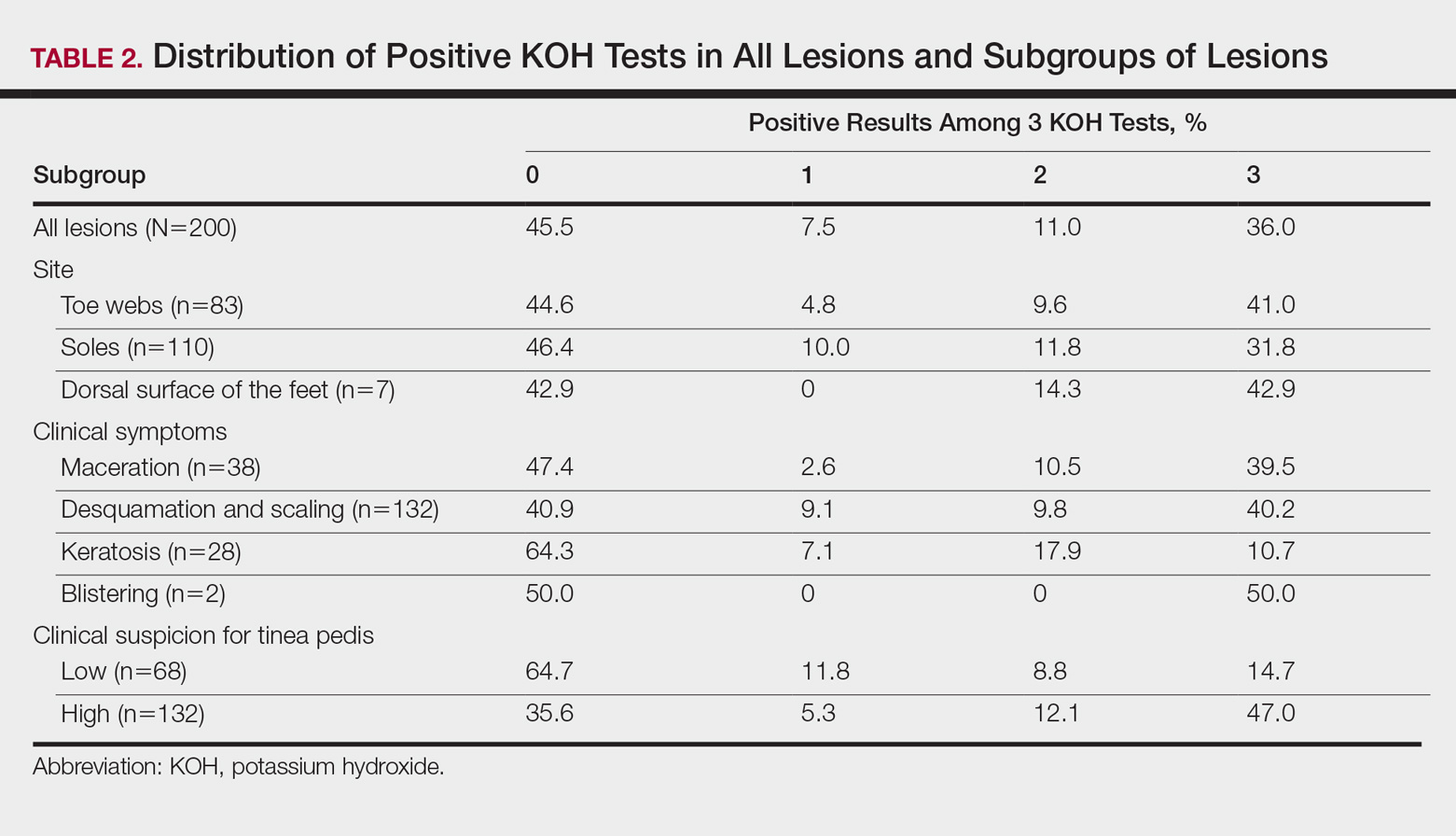

Among the 200 lesions from which skin scrapings were taken for KOH testing, 83 were in the toe webs, 110 were on the soles, and 7 were on the dorsal surfaces of the feet. Of these 7 dorsal lesions, 6 were extensions from lesions on the toe webs or soles and 1 was inconsistent with the 3 subtypes of tinea pedis. Among the 200 lesions, the main clinical symptom was maceration in 38 lesions, desquamation or scaling in 132 lesions, keratosis in 28 lesions, and blistering in 2 lesions. The dermatologist recorded the level of suspicion for tinea pedis as low in 68 lesions and high in 132.

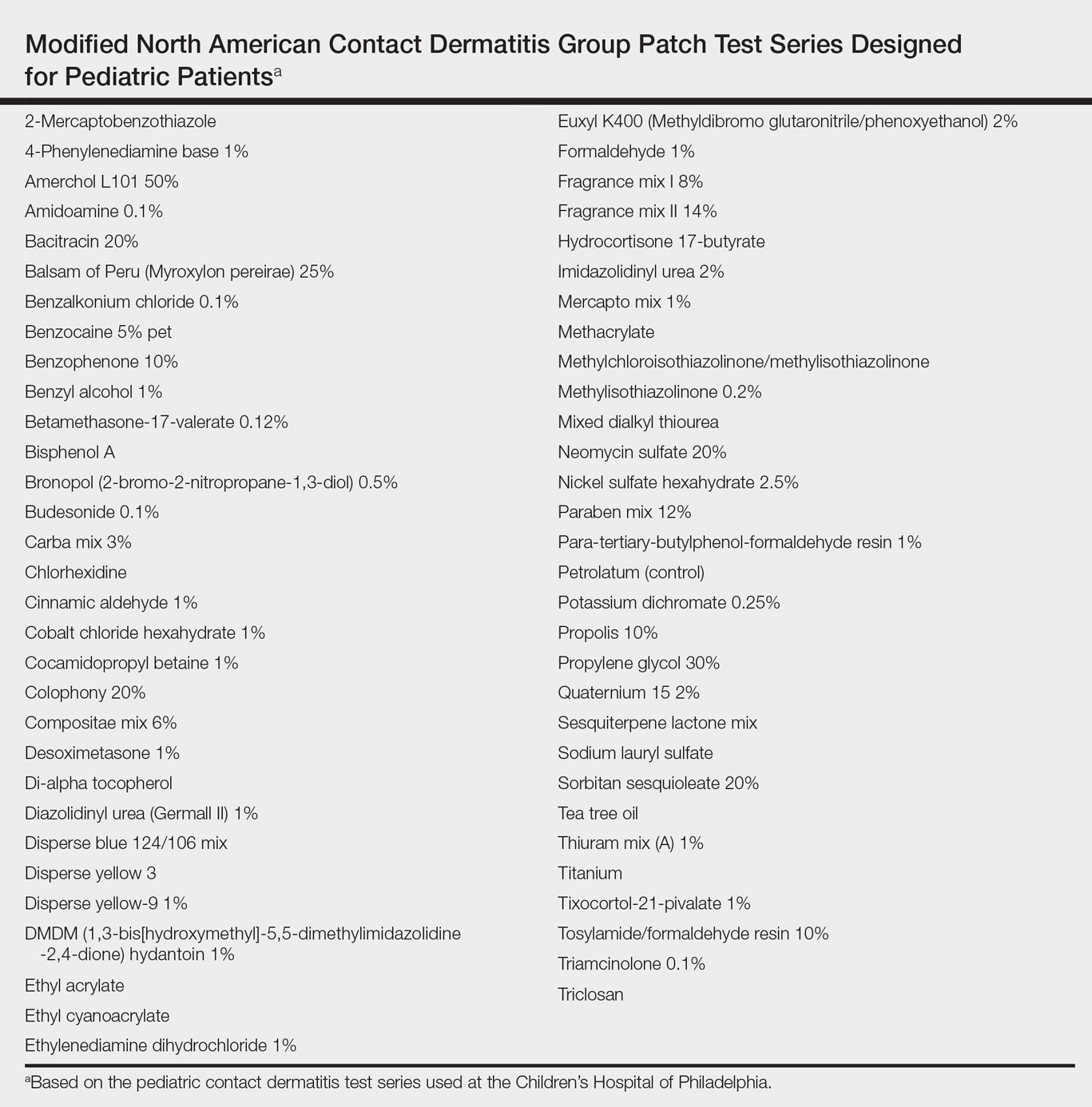

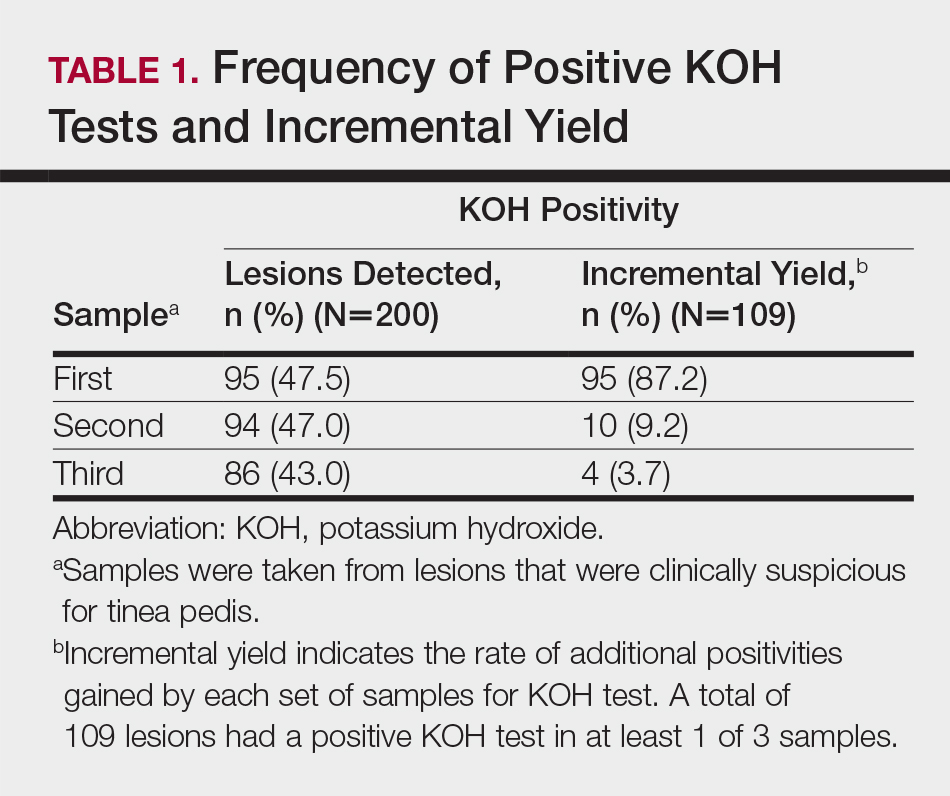

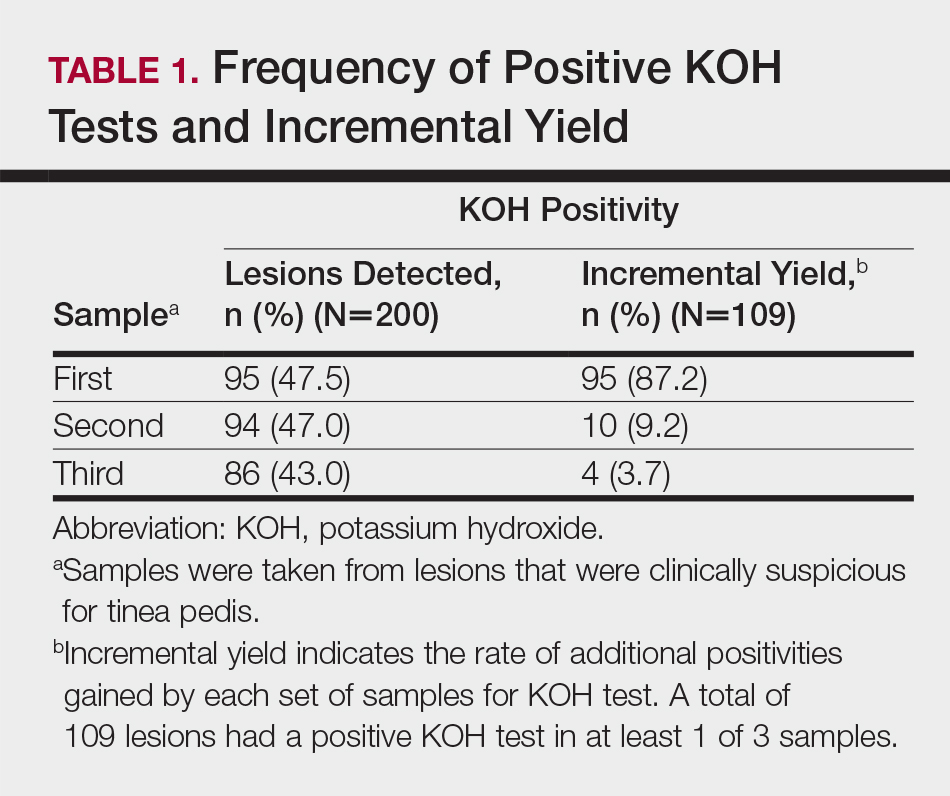

According to the order in which the dermatologist took the 3 samples from each lesion, the KOH test was positive in 95 of the first set of 200 samples, 94 of the second set, and 86 of the third set; however, from the second set, the incremental yield (ie, the number of lesions in which the first KOH test was negative and the second was positive) was 10. The number of lesions in which the first and the second tests were negative and the third was positive was only 4. Therefore, the number of lesions with a positive KOH test was significantly increased from 95 to 105 by performing the second KOH test (P=.002). This number again increased from 105 to 109 when a third test was performed; however, this increase was not statistically significant (P=.125)(Table 1).